ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to describe the occurrence of vitality affects and basic affects and to shed light on their importance in terms of patients’ inner change through art therapy. In an earlier study, where 17 women were interviewed about inner change through art therapy, a secondary deductive content analysis of images and statements was performed exploring the presence of vitality affects and basic affects. Nine of the 17 interviews contained clear descriptions of vitality affects and basic affects in the intersubjective communication between the patient and the therapist; these affects were also mirrored in the patients’ painted images. Three cases are used to illustrate the result and how affects are related to inner change. These three cases differ from each other in that they describe vitality affects either; arising from the art therapist’s empathetic verbal or non-verbal response, from a particular experience in nature, or from the interpreted symbolic language of the image. The common denominator identified as uniting the three cases was the intersubjective communication with the therapist. This study indicates that image making in art therapy gives rise to vitality affects and basic affects that contribute to inner change. It also indicates the importance of having trust in both the method and the art therapist.

Background

Cultural and creative activities have gained renewed interest in psychotherapeutic treatment (Stern, Citation2010). According to Stern, creative activities such as art, music, and dance can begin an inner movement that leads to vitalisation in a way that promotes processes of inner change and in turn improves health. The therapist’s actions when practising non-verbal therapeutic methods correspond to the affective attunement of a mother to her infant child. The significance of an intersubjective relational field in terms of change and development has affected the development of dynamically-orientated psychotherapy for adult patients (Stern, Citation2004), and has also had a significant effect on art therapists’ understanding of intersubjectivity (Case & Dalley, Citation2014). An empathetic art therapist is thought to be able to use his or her own imagination to stimulate intersubjective communication with the client as part of the reflective dialogue about the image (Edwards, Citation2004).

It is clear that the relationship between client and therapist is of fundamental importance to all art therapy (The British Association of Art Therapists [BAAT], Citation2017), and the art therapy literature stresses the importance of building a ‘therapeutic alliance’ (Gilroy & McNeilly, Citation2000). A therapeutic process that results in development and inner change requires the client to attach to both the therapist and the method, and this attachment can be secure or insecure (Bowlby, Citation1988). During a course of art therapy, a person’s pattern of attachment may become visible in relation to the artistic material being used (Snir, Regev, & Shaashue, Citation2017). Clients with secure attachment generally respond positively to various types of material and to fellow clients when art therapy sessions are conducted as a group therapy. Clients show interest in experimenting, exploring, reflecting, and communicating, however clients with insecure attachment, may show an avoidant behaviour and resistance to intimacy, both with the material and with the therapist.

That different artistic materials give rise to different affects and feelings in the client is a basic tenet of art therapy (Hinz, Citation2009). Letting the client choose between different types of materials can help reduce resistance and facilitate attachment. Control over the process of image making can increase when using pencils or hard wax crayons (Kramer, Citation1971). In contrast, one’s affective state cannot be controlled in the same way when working with finger paints and soft oil crayons (Snir et al., Citation2017).

Intersubjectivity is a psychoanalytic concept that has been described in the art therapy context as a dynamic field that arises between client and therapist (Schaverien, Citation1999). Intersubjectivity refers to a deeper relationship involving, for instance, communication between the inner subjects of a mother and her child or the inner subjects of a client and his or her therapist (Stern, Citation1985, Citation2004). Such communication requires the ability to distinguish oneself as a separate individual relative to the other, and the so-called ‘sense of self’ is a key component of psychodynamic development theory (Stern, Citation1985). According to Stern, intersubjectivity in psychotherapy is a subjective experience that is shared between two people that can lead to inner change and development. It is primarily implicit and non-verbal in nature, but it can also be verbal, and it involves both the client’s and the therapist’s subjective selves. The concept of vitality affects was first formulated by Stern (Citation1985) and is suggested to be part of subjectivity and intersubjectivity. ‘It is the movement, dynamics, and temporal progression that imprint meaning onto the experience of a feeling, a succession of memories, or any mental process’ (Køppe, Harder, & Væver, Citation2008).

Vitality affects and basic affects

Vitality affects refer to a specific intrasubjective sense of energy, power, and meaning, a sense of aliveness. Vitality affects are a separate kind of experience that emerge in an encounter with dynamic and stimulating movements, which are either conscious or unconscious. Vitality affects contribute to processes of change and development, not just during infancy but throughout one’s entire life (Stern, Citation1985, Citation2010). In a course of psychotherapy, the therapist’s non-verbal communication of compassion and empathy can, together with the dialogue, give rise to a sense of vitality in the client. Vitality affects differ from the basic affects formulated by Tomkins (Citation1984) of joy, interest, surprise, disgust, distress, anger, sadness, fear, and shame. The difference is that, according to Tomkins, the basic affects are primarily a biological response, whereas the vitality affects are of an inner psychological nature (Stern, Citation2010). Tomkins (Citation1984) describes affects as a form of emotional excitement that can be of varying intensity and duration. Usually a basic affective episode is of short duration and will produce a bodily reaction, most commonly in the face or voice. It may trigger bodily reactions like laughter or crying, which can make the affect communicable. The basic affect activates a response perceived by the individual as a feeling, and this feeling then becomes a conscious perception of the basic affect (Tomkins, Citation1984). Basic affects underlie thoughts, decisions, and actions, and they are described as the primary motivational system. Emotions, on the other hand, are feeling-based memories associated with past events in one’s life, as opposed to feelings that are happening right now, i.e. they are a result of a basic affect (Tomkins, Citation1984).

According to the Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC), the contact with the artistic material produces kinaesthetic and sensory experiences (Kagin & Lusebrink, Citation1978). Kinaesthetic experiences are bodily phenomena consisting of activity, movement, rhythm, and the release of energy, while according to Hinz (Citation2009), sensory experiences can be tactile, visual, or auditory, and they can sometimes give a sensation of smell and taste. Kinaesthetic and sensory experiences can give rise to various types of affects. These sensory experiences have a pre-verbal background and can be traced back to early childhood development at the non-verbal level (Hinz, Citation2009). The perceptual affective level on the ETC can help the clients identify and communicate feelings and emotions, while the cognitive symbolic level includes executive functions and contributes to insight, acceptance, and self-esteem. All levels on the ETC are part of a creative and dynamic art therapy process, and the patient may go through all of these levels during a single session in no particular order (Kagin & Lusebrink, Citation1978).

Vitality affects in art therapy remain a relatively unexplored area. Until now, vitality has only been studied in the context of art therapy and autistic children (Evans & Rutten-Saris, Citation1998), but Smeijsters, Kil, Kurstjens, Welten, and Willemars (Citation2011) have shown that various non-verbal methods, such as art, dance, and drama therapy, can promote a feeling of vitality in young offenders. There is a renewed interest in non-verbal therapy methods of psychotherapeutic treatment including art therapy (Stern, Citation2010). Springham and Brooker (Citation2013) stressed the need for research into what factors in art therapy contribute to individual and inner change in the individual. The lack of research aroused our interest in providing a more thorough description of the occurrence of vitality affects and their significance to internal change. In order to clarify the difference between vitality affects and basic affects, it was important to simultaneously explore the occurrence of basic affective expressions in the patients’ painted images and statements.

Aim

The aim of this study was to describe the occurrence of vitality affects and basic affects during art therapy and to shed light on their importance in terms of clients’ inner change.

Method

This study took a qualitative approach and a secondary analysis was performed using a deductive content analysis (Mayring, Citation2000, Citation2014). Interviews with 17 women about inner change through art therapy from an earlier study were used (Holmqvist, Jormfeldt, Larsson, & Lundqvist Persson, Citation2016). The aim of this earlier study was to describe whether patients experienced inner change through art therapy and, if so, to explore what aspect of art therapy was important for their inner change. The first author (GH) is an art therapist (PhD) and the last author (CLP) is in addition to being an associate professor, a licensed psychologist and licensed psychodynamic psychotherapist. The patients were recruited by art therapists who in turn were recruited from the Swedish Association of Art Therapists (SRBt) (Citation2017). Four experienced clinical art therapists took part in the recruitment process; one art therapist worked in a psychosomatic clinic, one worked in an adult psychiatric clinic and two art therapists were private practitioners. Exclusion criteria were: persons younger than 18 years, non-Swedish speaking and seriously ill patients. For the patients interested in the study, group information was held by the first author. A total of 25 women were interested, expressed a desire to participate and attended the information meeting held by the first author. Finally, 17 women were interviewed individually by the first author. The patients were not previously known by the authors. The art therapists who had worked with the interviewed patients had no input in the analysis of the study, but participated in recruiting participants.

In the secondary analysis three interviews were selected as cases to illustrate and present the results (Edwards, Citation1999; Kapitan, Citation2010). According to Edwards, case histories can provide knowledge about art therapy based on clinical experience, which in turn can facilitate theory formation and continued research.

All 17 interview transcripts were read carefully. A deductive content analysis was performed, which means that one starts with preliminary concepts and/or theories. We started from the definition of vitality affects (Stern, Citation2010) and basic affects (Tomkins, Citation1984) and the theories of attachment (Bowlby, Citation1988). In the tape recorded and transcribed interviews and in the artwork we looked for the presence of signs and expressions of vitality affects, basic affects and attachment signs and/or expressions. Expressions of vitality affects and basic affects in the images and stories were highlighted and grouped as well as expressions of attachment and inner change (Mayring, Citation2000, Citation2014).

Ethics

The original study was approved by the regional ethics review board in Gothenburg, Sweden (reference number 726-11). Informed consent was obtained from all 17 participants. Before the secondary analysis of the three interview transcripts and images and in agreement with the regional ethics review board in Gothenburg, Sweden, another informed consent was obtained from the three women whose interview forms the basis for description of the case. Pseudonyms have been used to ensure the confidentiality of these participants.

Results

Nine of the interviews were found to contain clear descriptions of vitality affects and basic affects. These were related to the corresponding images and to intersubjective communication between client and therapist. All of the basic affects identified by Tomkins (Citation1984) were represented. In all nine of the interviews, the women described one or more events of importance to their inner change. The women described the broad spectrum of feelings and emotions they were experiencing in the moment, and these included difficult feelings like grief, fragility, despair, discontent, anxiety, and anguish. They also described bodily reactions such as heart palpitations or crying. Positive feelings such as relief, freedom, power, warmth, hope, calm, joy, and gratitude were also mentioned. The range of emotions had to do with the fact that the images helped the women recollect things they had experienced in connection with a described event. Emotions ranged from deceit, humiliation, abandonment, and being alone to feeling ostracised and bullied. While basic affects could relate to either positive or negative experiences, the vitality affects were all described as being of a positive nature.

Internal changes were related to a kind of identity change in which there was a clear before and after. The change was a composite experience of security, identifiable affects, emotions, feelings, and vitality affects. For instance, the identity change was described as a feeling of being in love with one’s own image and a sense of freedom, acceptance, hope, or relief. It assumed forms like waking up, getting one’s thought process started, or being able to confront one’s inner self. In other cases, change had to do with the ability to cope with problems in a different way or to realise one’s limitations, or an understanding of the need to take care of oneself.

The eight women who showed unclear or non-existent vitality affects or basic affects also showed insecure attachment and no clear signs of inner changes. Some of these women described acting out basic affects rather than gaining insight and emotional awareness. On the other hand, the women did describe great value from their art therapy as a support in daily life or as a way to free themselves of difficult feelings, as a catharsis.

The following three cases are used to illustrate vitality affects and basic affects in the context of art therapy and how they are related to inner change. These three cases differ from each other in that the described vitality affects either arise from the art therapist’s compassionate and empathetic verbal or non-verbal response, from a particular experience in nature, or from the interpreted symbolic language of the image painted during the therapy sessions. The common denominator uniting the three cases is that there was intersubjective communication with the therapist that stemmed from a secure attachment to both the art therapy method and to the therapist as well as from the therapist’s ability to adjust and attune their own affects to those of the patient.

Laura

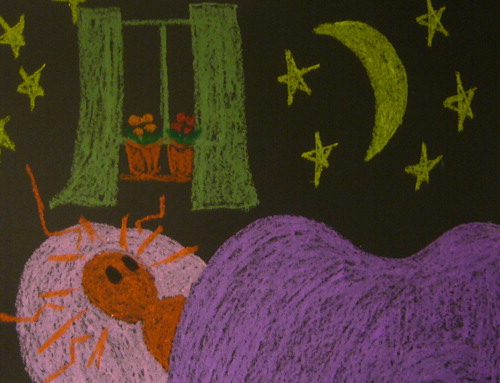

Laura has completed a two-year course of group art therapy. She is 52 years old and has been diagnosed with fibromyalgia. Laura stopped taking antidepressants during the therapy. Laura related that she had been seeking help for several years without feeling she had received the help she needed, but “I knew right away that this was something for me and that’s why I thought I might let it all out”. She quickly became comfortable with the working method of art therapy and with participating in therapy sessions in a group. Laura brought two important images along to the interview that she wanted to present and talk about. The first image () was painted after only three months in therapy and had led to a crucial insight.

Yes this is a special image … we had spoken about what hurt so badly … I had a hard time … I did not know exactly how I felt either, but the image just came out. … I thought I was able to get out exactly the way I felt.

Once Laura had painted , she was both surprised and sad. Emotions from the past that she thought were gone reappeared. Seeing the image, Laura realised that she ‘still felt bad about what happened’. The art therapist’s empathetic treatment of Laura was crucial in terms of allowing emotions and relived feelings to come forward so that they could be worked through in a different way from before and could thus lead to important insights.

My therapist said something about how another person had put the responsibility on me, and I had never seen it in that way before … and at that point it was as if a huge burden had been lifted off my shoulders. Then afterwards … when the therapist took a closer look at the picture, she said: ‘But you’ve got no mouth’ … and it’s true … I didn’t know that while I was painting, but when she said it, I saw it … there was nothing I could say in that situation … so in that sense she put words to my feelings.

Further, Laura said that while she was painting , she felt free, both physically and emotionally: “There are plenty of colours here, it’s flowing wet with plenty of colours, and things smeared and ran down onto the floor’. Laura’s choice of liquid colours and the way she created the image clearly reflected the change she had undergone. was smaller than , and it was drawn in crayon. Laura sums up her story by pointing out that the subject of the image came to her the moment she began painting. Laura stresses that at that moment she was completely unaware that she was still carrying a painful memory. Although Laura had spoken about the incident before, this did not lead to the same emotional experience of freedom at that time: “I don’t know if I was able to properly describe my experience in words”. Laura had always had a hard time expressing her feelings, and she emphasised that it was the feelings in the image that were important, not the subject of the image per se.

Everything in Laura’s story points to her needing to express something difficult that happened to her, and she was working on the cognitive level in the first image. The paper chosen for was relatively small and limited, and that Laura chose to draw with crayons indicated that she sought to create an image with a relatively high degree of structure and emotional control. turned out to be the very opposite of the first. The paper was large, Laura used liquid paints, and she painted with her hands. The level of emotional control was thereby minimal. Laura said that she slapped the paint right onto the paper and let the colours run down onto the floor. In this process of image making, Laura expressed a sense of newfound freedom. On the whole, the two pictures show the importance of offering patients the opportunity to choose their materials based on their emotional state and their need for control.

Sophie

Sophie attended art therapy on and off for several years; however, she completed a two-year treatment in group art therapy a few years ago. Sophie is 58 years old and has been diagnosed with depression. During Sophie’s time in therapy, she understood that she did not have the ability to work anymore, and she was granted permanent sickness benefits. Sophie also continued to take antidepressants. She had not looked at her images after completing the therapy and when she was looking at them during the interview she noticed that they still gave rise to the same feelings now as they did then. Her husband, whom she had been caring for at home, passed away during the two years of group therapy sessions, and her daughters who now were adults left home at almost the same time. The family dog also died of old age during this time. Sophie was used to working hard and taking care of everyone; now she felt abandoned, insignificant, and insecure. Sophie’s situation brought back old feelings, and her sorrow and the crisis she was in were intensified by her life story.

My husband disappeared … my dog disappeared … things were so chaotic. I have been very alone ever since I was little … I was an unwanted child, so I have been very, very, very alone.

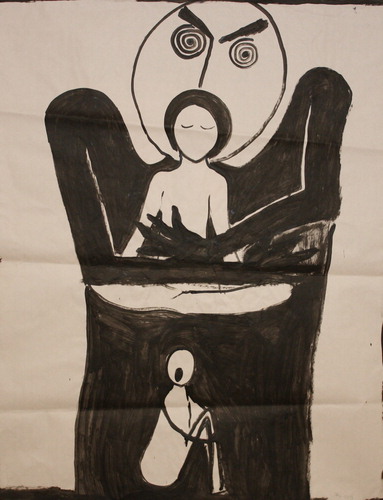

Throughout the group art therapy sessions, Sophie drew images that demonstrated ambivalence about whether she wanted to keep on living. is an example of these images. This image expresses a choice, should Sophie pursue the path of life or that of death?

Sophie’s is about a powerful experience she had during a walk.

A ray of light came down from the sky, probably the sun filtering through the clouds. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen, or had seen for many years. It was like I was there. I can’t forget that light, it was almost as if something was telling me: ‘Wake up!”

Sophie said the light only lasted a brief moment, but that she felt warm all over, and that she sat down on a rock to cry. Nature had given rise to a vitality affect in her, a feeling of being alive: ‘All of a sudden there was something bright, something that wanted to push me forward’, Sophie cried as she painted the image. She went on to say that this was a turning point in her life. After this experience of light and a feeling of being alive, she was able to approach her deep and difficult feelings of sorrow, loneliness, and abandonment, feelings that she had had since childhood. She understood that she now had to draw strength from her positive memories in life. After that insight, Sophie painted several images through which she relived her relationship with her husband. She was able to experience the feeling of his closeness and warmth in the images. was painted after Sophie had paid a visit to a special beach that had meant a lot to her and her husband. For the first time since he had passed away, she had found the courage to return to this beach. Nature and the sea inspired a sense of calmness. In this image, Sophie described the feeling of being stranded, which meant to her that she had realised that she was now alone, but had come to a degree of acceptance of this new life situation. “I’m sitting here and watching, and suddenly my world is a bit happier”. Sophie did not feel happy per se, but she said that the memory of her husband’s love gave her strength with each new day.

Sophie had gone through a bout of severe depression with suicidal thoughts. In her first image, she wrestles with thoughts of not wanting to live any longer. She felt completely abandoned and alone. Being an unwanted child had given rise to insecure attachment, which in turn made her highly dependent on her husband and children. Sophie’s insecure attachment was a contributing factor in her difficulty in accepting help. She stressed the importance of feeling trust, both in the therapist and in her fellow group participants. She focused on the content of the images, but her story also showed the importance of the therapist as a factor in helping to establish a sense of security. After some time, once Sophie had realised that the art therapy was about herself, she painted images in which she struggled with her thoughts of suicide. The light in came as an unexpected revelation, a vitality affect that conveyed a sense of being alive. After that, Sophie was able to approach her underlying feelings of sorrow and abandonment. She had developed an acceptance of her life situation.

Julie

Julie had three years earlier completed a nine-year programme of individual art therapy. Julie was 34 years old and had been diagnosed with panic attacks and depression. She was no longer on medication at the time of the interview. Julie had pursued her studies and started a family, and said she now felt healthy.

Julie said that she had started cognitive therapy, but: ‘I was unable to talk about myself … so I just answered all the questions with “I don’t know”. The purpose of art therapy was for her to get in touch with her feelings and to be able to put them into words. In image making, Julie found a language with which she could express her problems. Many images were important to her, but in the end Julie chose three images from various stages of the therapeutic process. She described the first image as an encounter with herself; in the second image she described how different parts of her personality were beginning to fuse into a whole; and in the third and last image in Julie’s therapy she described herself as a whole, coherent person.

reflected reality as Julie experienced it after six months in therapy. Everything in her life was very destructive and messy, and she was confronted with the darkness that was always lurking in the background and which she felt was ready to attack her. Julie’s confrontation with herself became an encounter with destructiveness, chaos, and a variety of feelings, especially in the form of anguish. Julie had long experienced her world as divided into three parts. The black part on top was ‘the big, bad role’ she played. Julie said that the role performed its day-to-day tasks and functioned very well even though it was empty. The role always showed a happy face. In the middle of , there is an intermediate world that she referred to as her ego, and at the bottom there was ‘this inner world … that anguish … down at the bottom that no one could see’.

For Julie, the process of painting moved forward from what she and the therapist discovered as something interesting in the image, such as the black or the blue door in . Julie then continued painting and exploring what was behind these doors in the next image. The communication between Julie and the therapist was characterised by non-verbal intersubjective communication. When they scanned the image for something that touched them both deeply, this gave rise to a vitality affect that in turn led to a creative impulse. Julie said that the creative impulse guided her to fight against all of the blackness and that her ego ‘was locked up somewhere … deep inside’.

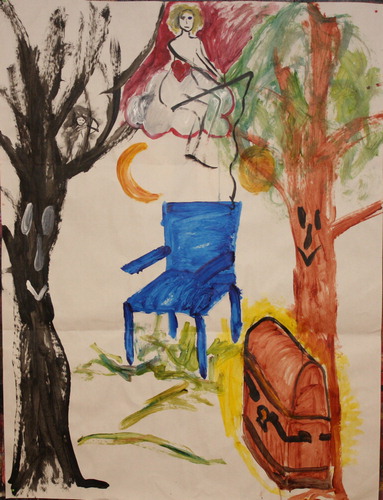

Julie painted a large number of images that she described as a struggle with the darkness. Julie mostly used a symbolic language in her images, and abstract objects and figures frequently symbolised feelings. Julie used different colours in order to lend the objects additional meaning or to differentiate them. In , the different colours of the doors show different life choices. Behind the green door, the ego and the role were joined into one unit, the red door is a door to the future, and the black door opens down into her anguish. The symbol of the ego and the role came up at a relatively early stage of her therapy, and Julie said that she early on understood that she needed to integrate these different parts into a coherent personality. At the same time, this was impossible for her. When in Julie joined her ego and the role together, integrating these different parts happened in an unexpected and surprising way.

This is those three worlds. The reality is up there (the role) … then the intermediate world (the ego) … and then finally this lower world (the anguish). This is probably the first image in which the ego and the role are becoming one … in this blue armchair. Suddenly I put them together […] I felt something big had happened … I had grown in some way.

Above the blue armchair sits the ego and the role as a single entity. The blue armchair stands for security, and it was always there in Julie’s thoughts as an image. The real blue armchair is at Julie’s summer cottage and is where she used to sit. The coffin had appeared in previous images, and it holds different tools for survival, i.e. cognitive strategies. There are two trees. The black one on the left is the darkness Julie carried with her in her life story. The bright tree on the right had appeared as a helper in previous images as well. The purpose of the fishing rod is to keep Julie’s feet on the ground. There is a small black figure in the black tree:

It’s that black figure … I don’t know if it’s that one in particular … but it’s what remains of the black figures … somehow … and it got so small that I can hold it in my hand … as a memory.

Julie had a strong experience of change and was able to become authentic with herself through the art therapy. “I mean, it’s hard to explain things in words … it’s almost impossible. That is what the images do, somehow”. In view of Julie’s fragmented emotional life and severe problems, the therapist’s actions had a crucial bearing on Julie’s transformation. The art therapist’s empathetic approach and capacity for intersubjective communication made it possible to deal with the emotional content in Julie’s images. It was primarily the non-verbal intersubjective communication that made it possible for the therapist to share Julie’s experiences of anguish and disintegration. This evoked a dynamic movement, a vitality affect in Julie that in turn helped her interpret and understand symbols and identify feelings and to put them into words, and by reflecting together with the therapist Julie was able to find a sense of personal coherence. Expressing herself figuratively through symbols means, according to ETC theory, moving on a symbolic/cognitive, intellectual level (Hinz, Citation2009). Being at this level can help satisfy the need for control over difficult and indefinable feelings. If Julie had been encouraged by her therapist to paint more emotional images on the kinaesthetic or sensory level, this might have led to increased anguish. Julie stressed the importance of the fact that the images defused the things that were difficult to endure and enabled a slow approach with a minimal risk of being overwhelmed by painful feelings. Julie’s story of change in relation to the images from different phases of her therapy showed that there was a continuous and ongoing process that facilitated her development and her inner change.

Discussion

In nine out of the 17 interviews, there were clear descriptions of vitality affects and basic affects and of how these contributed to inner change as illustrated by the three cases. The common factor shared by these nine stories was that there was a secure and positive attachment to the method and to the therapist. The existence of a close relationship between the art therapist and the method has been described by Malchiodi (Citation2016), and she gives attention to the fact that the art therapist’s knowledge and empathetic ability are prerequisites for successful art therapy. She pointed out that it is not only the image making that is the effective component in art therapy, but also the art therapist’s knowledge and sensitive relational skills. The results of the present study confirm the importance of the connection between the image and the art therapist alike.

It is known that secure attachment is fundamental to intersubjective communication per se (Case & Dalley, Citation2014), but to see its significance emerge so strongly in the analysis presented here came as a surprise. The purpose of this study was not primarily to explore the significance of attachment in terms of inner change, but this factor grew so prominent in the analysis that it deserves to be mentioned.

The nine women who experienced an inner change described increased emotional awareness, and they talked about both positive and negative feelings that they were able, with the help of the therapist, to identify, define, and sometimes reformulate. Memories of difficult events that were conveyed in their images gave rise to emotions and basic affects that led to the events being relived in the present. Emotionally, reliving a difficult event in a secure environment made it possible for the women to tell their stories, to be understood, and to share their pain with an empathetic and compassionate therapist. Expressing and sharing their pain made it possible to reinterpret difficult experiences or to come to a better understanding of them. A painted image contains both past (emotions), present (feelings), and future (hope), and as the women presented here confirmed, can be used to defuse otherwise overwhelming feelings. A therapist with the ability to show how a developmental path can be discerned in the image in parallel with the client’s painful feelings is able to inspire hope. This hope makes it possible for the client to imagine life changing for the better.

Feeling hope for the future is a necessary element in all forms of psychotherapy, including art therapy. Hope puts the client into a state where development and change are possible, and it is here that vitality affects have an important impact. They can convey a sense of being alive, irrespective of whether this is evoked by the therapist’s empathetic response, an experience in nature, or something particular to a painted picture. The vitality affect experienced by Laura occurred from the therapist’s non-verbal and verbal responses to Laura's silent signal of pain. The art therapist understood and shared Laura's pain without words, which in turn helped unburden her of feelings of guilt and shame. The change was described by Laura as a newfound sense of freedom and power. The newfound sense of freedom from guilt and shame might be understood in the light of the ancient Greek concept of catharsis, which means ‘purification’, and is used in the context of art therapy to describe a patient having liberated himself or herself from difficult feelings from the past to be constantly present in the moment (Case & Dalley, Citation2014). Sophie had an experience in nature involving light that gave rise to a vitality affect that in turn gave her the feeling of coming back to life after many years of severe depression. The feeling of being alive gave Sophie a renewed sense of having the strength to face her sorrow and pain without this leading to unbearable anguish about being abandoned and dead. Julie also described the vitality affect as an awakening and her story is based on the sense that she had until now lacked a genuine strong internal core lending stability to her existence – or a strong sense of ‘self’ (Stern, Citation1985). The vitality affect therefore resulted in an awakening self, which inspired a sense of hope in becoming a complete and coherent human being.

The analysis of the nine interviews, three of which were chosen to illustrate the results, revealed the significance of the vitality affects and the basic affects in terms of these women’s inner change over the course of their art therapy. Vitality affects proved to be of great individual importance in terms of the therapies’ potential to progress toward decisive inner change. It can be assumed that numerous vitality affects occur over the course of an art therapy process that is based on positive, secure attachment. It can also be assumed that several of these affects pass unnoticed on a more unconscious and intersubjective level that never quite reaches the conscious mind, whether that of the patient or of the therapist. Nevertheless, these vitality affects have a major bearing on, and are of great importance to, the process of individual inner change that art therapy generally aims to bring about.

The intention of this study was to shed light on the significance of vitality affects and basic affects in terms of individual inner change and the ways in which they can appear in treatment involving art therapy. The aspect of art therapy that promotes vitality affects and basic affects is largely the patient’s own image making, i.e. the creative and playful exploration of one’s emotional life using the artistic materials and the symbolic language of the image. The opportunity to engage in this type of playful exploration is essentially what distinguishes art therapy from other therapeutic methods. This study indicates that image making in the art therapy process gives rise to vitality affects and basic affects that contribute to inner change, and it also indicates the importance of attachment and having trust in both the method and the therapist.

Limitations

Vitality affects in art therapy remain a relatively unexplored area. For this reason, there was no substantial body of previous research for this study to draw on. The concept of vitality affects, which is also relatively new in psychodynamic psychology, has only appeared a few times in the professional literature on art therapy. The widely used concept of non-verbal communication contains a great number of different qualities that should continue to attract increased differentiation and understanding of how inner change takes place during art therapy.

Given the fact that vitality affects in art therapy can be seen as a relatively new field of research, it would have been of value to be able to present additional cases in order to shed light on additional expressions of vitality affects and basic affects.

Finally, the study is limited by the fact that all the participants were women; a mixed study using men and women may have provided different outcomes, and further research is required in this area.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all the 17 women who contributed to this study by showing and talking about their images. Special thanks are due to the three women who allowed us to illustrate their results in this study. Many thanks also to the four art therapists who helped with recruitment and with the consent form process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Gärd Holmqvist, The author is authorised Art Therapist according to Swedish National Association of Art Therapists (SRBt), Occupational Therapist, Fil.mag in Art Therapy, PhD in Health and Lifestyle at Halmstad University in Sweden. Her thesis: Art therapy – a pathway to inner change and improved health (Bildterapi – en väg till inre förändring och förbättrad hälsa) was defended in January 2018. She has published three articles on this subject. She has experience of working with art therapy in psychiatric care since 1977.

Ingrid Larsson, RN, PhD in Health and Caring Sciences. She holds a position as Senior Lecturer at School of Health and Welfare, Halmstad University, Box 823, S- 301 18 Halmstad, Sweden. The research focuses on person-centred care, patient participation, rheumatic diseases, health and sustainable youth, qualitative research, intervention and implementation research.

Åsa Roxberg, RN, RNT, Mc, PhD in caring science. She holds a position as professor at School of Health and Welfare, Halmstad University, Box 823, S- 301 18 Halmstad, Sweden and VID, Specialized University, Ulriksdal 10, 5009 Bergen, Norway. The research focuses on existential health, suffering and relief of suffering, consolation and theoretically drawing from Ricoeur, Gadamer, Merleau Ponty.

Cristina Lundqvist-Persson, Associate Professor, Lic. Psychologist, Lic. Psychotherapist, Clinical Specialist. She holds a position as research leader at Skaraborg Institute for Research and Development in Skövde, Stationsgatan 12, S-54130 Skövde, Sweden. She is an experienced clinician, as well as a teacher at university, supervisor and examiner of psychotherapists. She is engaged in a broad range of research projects from preterm infantś development to preventing HIV and AIDS among a group of Maasai schoolchildren in Kenya and psychotherapy for children and adults.

ORCID

Gärd Holmqvist http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9497-2617

Åsa Roxberg http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0017-5188

Ingrid Larsson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4341-660X

Cristina Lundqvist Persson http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8191-0679

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory (collected papers). London: Tavistock.

- Case, C., & Dalley, T. (2014). The handbook of art therapy. Howe, East Sussex: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Edwards, D. (1999). The role of the case study in art therapy research. Inscape, 4(1), 2–9. doi: 10.1080/17454839908413068

- Edwards, D. (2004). Art therapy. London: SAGE.

- Evans, K., & Rutten-Saris, M. (1998). Shaping vitality affects, enriching communication: Art therapy for children with autism. In D. Sandle (Ed.), Development and diversity: New applications in art therapy (pp. 57–77). New York: Free Association Books Limited.

- Gilroy, A., & McNeilly, G. (2000). The changing shape of art therapy: New developments in theory and practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Hinz, L. (2009). Expressive therapies continuum: A framework for using art in therapy. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Holmqvist, G., Jormfeldt, H., Larsson, I., & Lundqvist Persson, C. (2016). Women's experiences of change through art therapy. Arts & Health. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2016.1225780

- Kagin, S., & Lusebrink, V. (1978). The expressive therapies continuum. Art Psychotherapy, 5, 173–180. doi: 10.1016/0090-9092(78)90031-5

- Kapitan, L. (2010). Introduction to art therapy research. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Køppe, S., Harder, S., & Væver, M. (2008). Vitality affects. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 17(3), 169–179. doi: 10.1080/08037060701650453

- Kramer, E. (1971). Art as therapy with children. New York, NY: Schocken Books.

- Malchiodi, C. (2016). Expressive arts therapy and self-regulation. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/arts-and-health/201603/expressive-arts-therapy-and-self-regulation

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2). doi: 10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. Retrieved from http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/39517/ssoar-2014-mayring-Qualitative_content_analysis_theoretical_foundation.pdf?sequence=1

- Schaverien, J. (1999). The revealing image : Analytical art psychotherapy in theory and practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Smeijsters, H., Kil, J., Kurstjens, H., Welten, J., & Willemars, G. (2011). Arts therapies for young offenders in secure care—A practice-based research. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38(1), 41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2010.10.005

- Snir, S., Regev, D., & Shaashue, Y. H. (2017). Relationships between attachment avoidance and anxiety and responses to art materials. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 34(1), 20–28. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2016.1270139

- Springham, N., & Brooker, J. (2013). Reflect interview using audio-image recording: Development and feasibility study. International Journal of Art Therapy, 18(2), 54–66. doi: 10.10880/17454832.2013.791997 doi: 10.1080/17454832.2013.791997

- Stern, D. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. A view from psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Stern, D. (2004). The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

- Stern, D. (2010). Forms of vitality: Exploring dynamic experience in psychology, the arts, psychotherapy, and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The British Association of Art Therapists [BAAT]. (2017). The British association of art therapists. Retrieved from http://www.baat.org/

- The Swedish National Association of Art Therapists [SRBt]. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.bildterapi.se

- Tomkins, S. S. (1984). Affect theory. In K. Scherer & P. Ekman (Eds.), Approaches to emotion (pp. 163–197). London: Lawerence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers.