?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Background

Art therapy is one rehabilitation treatment which enables youth in secure care to express unresolved conflicts, increase self-esteem, and gain insight to personal experiences in a creative and supportive therapeutic space.

Aims

This study investigated hope and resilience outcomes following art therapy for youth residing in a secure care centre located in Canada.

Methods

In this pre–post experimental design study, thirteen (N = 13) youth, ages 12–19, received 12 weekly individual art therapy sessions. Hope, resilience, and goals were measured using the Children’s Hope Scale (CHS), the Resilience Scale (RS-25), and the Bridge Drawing with Path (BDP) art-based assessment.

Results

Results indicated that the 12 weekly individual art therapy sessions enhanced hope and resilience in youth residing in secure care by 29% and 16%, respectively.

Conclusions

Secure care environments may benefit from incorporating art therapy as a rehabilitation treatment to improve youths’ levels of hope, resilience, self-determination, and future pathways.

Implication for Future Research

Future studies should utilise a group design with a control group to evaluate the effects of art therapy on youth residing in secure care environments.

Plain-language summary

Art therapy is one rehabilitation treatment which enables youth in secure care to express unsettled conflicts, increase self-esteem, and gain understanding of personal experiences in a creative and supportive therapeutic space. This study investigated the effectiveness of art therapy on the levels of hope and resilience in youth residing in a secure care centre located in Canada. In this pre–post experimental design, thirteen youth, ages 12–19, received 12 weekly individual art therapy sessions. Hope, resilience, and goals were measured using the Children’s Hope Scale (CHS), the Resilience Scale (RS-25), and the Bridge Drawing with Path (BDP) art-based assessment. Results showed that the 12 weekly art therapy sessions enhanced hope and resilience in youth residing in secure care by 29% and 16%, respectively. Secure care environments may benefit from including art therapy as a rehabilitation treatment to improve youths’ levels of hope, resilience, self-determination, and future pathways. Future studies should use a group design with a control group to measure the effects of art therapy on youth residing in secure care environments.

Introduction

A number of secure care environments exist in Canada for vulnerable youth whose life situations are unsafe. In 2020–2021, approximately 10,095 Canadian youth were involved in supervised secure care (Statistics Canada, Citation2022). Although Indigenous youth between the ages of 12–17 comprise only 7% of all adolescents in the general Canadian population, about 35% of youth admitted to secure care centres are Indigenous. Other overrepresented populations in secure care include Black youth from marginalised communities and invisible minorities (Lake, Citation2019).

Secure care environments are known to implement rehabilitation treatment for youth with underling mental health concerns, unhealed traumas, and a history of criminal offending, or at risk of offending in order to support their mental health and well-being (Benson, Citation2003, july; Hanon, Citation2016). The lack of rehabilitation treatment in secure care may contribute to mental health issues extending into the youths’ adult lives and may lead to recidivism (i.e. reoffending) (Lamberti, Citation2016).

Art therapy is one rehabilitation treatment which enables youth in secure care to express unresolved conflicts, improve self-awareness and self-esteem, and gain insight to personal experiences in a creative and supportive therapeutic space (Baillie, Citation1994; Donovan, Citation2022; Gussak & Virshup, Citation1997; Liebmann, Citation1994; Meekums & Daniel, Citation2011; Smeijsters et al., Citation2011). Art therapy is especially suitable for youth who find it challenging to express their internal conflicts and deep emotions through verbal means (Kramer, Citation2016; Moon, Citation1998; Rubin, Citation2016), and can psychologically prepare youth for their transition back into society (Darewych, Citation2013).

Clinical case examples in the field of art therapy have demonstrated positive outcomes in addressing mental health needs and modifying adverse behaviour in youth within secure care environments (Bennink et al., Citation2003; Gussak, Citation2020). Despite this, empirical research examining outcomes of art therapy for youth in secure care remains scarce within the art therapy literature. Larose’s (1988) study found art therapy promotes a positive self-image in juvenile boys exhibiting low socialisation skills. Persons’ (Citation2009) study findings concluded that both individual and group art therapy helps male youth relieve stress, reduce boredom, and gain new coping skills. Hartz and Thick’s (Citation2005) study reported that both art as therapy and art psychotherapy approaches can increase self-esteem in female juvenile offenders. Smeijsters et al.’s (Citation2011) naturalistic study found art therapy enables youth in secure care environments to reclaim their healthy self-aspects.

So far, based on our knowledge, no research investigating hope and resilience outcomes following art therapy for youth within a secure care environment in Canada has been conducted. Researchers and clinicians in the field of art therapy have commenced exploring the intersectionality between art therapy and positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihályi, Citation2000), and how the two approaches, in combination, can creatively support individuals’ character strengths, self-determination, life goals, and well-being (Darewych & Riedel Bowers, Citation2018), and promote hope and resilience (Wilkinson & Chilton, Citation2018).

In terms of hope, it is defined as a ‘cognitive set that is based on a reciprocally derived sense of successful (a) agency (goal directed determination) and (b) pathways (planning of ways to meet goals)’ (Snyder et al., Citation1991, p. 571). Thus, for an individual to strive for a better life and cognitively move forward towards life goals, agency and pathways thoughts are necessary. Studies have shown that high hope individuals have greater optimism, problem-solving skills, self-esteem, and positive goal expectancies, and lower symptoms of anxiety and depression compared to low hope individuals (Snyder, Citation1994; Snyder et al., Citation1998). Further, hope has been found to act as a protective factor against suicidal thoughts in high risk groups within secure care environments (Pratt & Foster, Citation2020).

Resilience is a more complex construct compared to hope. Resilience can be viewed as a trait which moderates negative effects of stress (Wagnild & Young, Citation1993) or as a process that involves an individual’s ability to consciously ‘move forward in an insightful integrated positive manner as a result of lessons learned from an adverse experience’ (Southwick et al., Citation2014, p. 4). Resilience can also be viewed as a process that harnesses individual’s resources (i.e. strengths, community) that enhance their coping abilities and sustain their overall well-being (Southwick et al., Citation2014). In the secure care literature, researchers have considered resilience to act as a protective factor against recidivism in youth (Fougere et al., Citation2015). Focusing on developing a sense of hope in this adolescent population can translate to an increase in their motivation for things to be better in their future. Providing an opportunity to increase resilience allows the youth to be more skilful in the face of adversity, threats, trauma, or significant sources of stress which is their ongoing lived experience.

Aim of study

To fill the gap in the art therapy literature, the researchers elected to investigate the hope and resilience outcomes following art therapy for art therapy on hope and resilience in youth residing within a secure care centre in Canada. Consequently, the primary research question for this pre–post experimental design study was: Can art therapy increase youths’ level of hope and resilience who are residing in a secure care centre? The framework for this study was based on the Centre’s strategic plan and core value statement that emphasised instilling hope for the youth in order for them to make better choices, envision new possibilities beyond their life in secure care, and undergo positive growth and change.

Methods

Sample

Thirteen (N = 13) youth (five males, seven females, one agender) aged 12–19 years, residing in a secure care centre located in Canada participated in the study. Participants self-identified their ethnic and racial background as White (n = 8), Indigenous (n = 3), and Black (n = 2). Common features in the personal histories of the participants obtained from the Centre’s digital case files included high risk behaviour, multigenerational trauma, and chronic and complex mental health concerns. At the time of the study, the youth were receiving other treatments (e.g. recreational therapy, mindfulness therapy groups, trauma-informed dialectical behavioural therapy groups) at the Centre.

The Centre where the study was conducted provides court-ordered assessments and two intensive treatment programmes: secure treatment and youth justice. The secure treatment programme is a provincial resource and is mandated by the Child, Youth and Family Services Act (see https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17c14/v13). Youth in this programme present with mental illness and are at significant risk of harm to self or others and no less intrusive programme is appropriate. The average stay is six to 12 months. In contrast, the youth justice programme is a secure custody and detention programme for youth who have an identified mental health issue, who are in conflict with the law, and aged 12–17 at the time of their offence. At the time of the study, two participants were in the secure treatment programme, while 11 participants were in the youth justice programme. All participants were new clients to the art therapy programme although their referral dates differed.

Experimental design

Due to the varied short timeframe of the youth residing in the Centre and no access to a control group, the researchers selected to conduct an outcome study utilising a pre–post experimental design (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018) with an art-based component in order to determine the effects of 12 weekly individual art therapy sessions on hope and resilience in the youth. Participants completed the following three measures at the beginning of the first and at the end of the 12th session providing pre- and post- test art therapy treatment data: Children’s Hope Scale (CHS; Snyder et al., Citation1997), the Resilience Scale (RS-25; Wagnild & Young, Citation1993), and the Bridge Drawing with Path art-based assessment (BDP; Darewych, Citation2013).

Measures

Hope

The Children’s Hope Scale (CHS; Snyder et al., Citation1997) which was developed for children and youth ages eight to 19 years, was used to examine participants’ hope and goal-directed thinking. The CHS scale consists of two subscales that assess the pathways and agency thinking components of hope. Each subscale consists of three items, for a total of six items for the total scale. An example of an agency subscale item is ‘I’m doing just as well as other kids my age.’ An example of a pathways subscale item is ‘When I have a problem, I can come up with lots of ways to solve it.’ Items are rated using an 8-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (definitely false) to 8 (definitely true). The CHS total score ranges from 6 to 36, whereas the agency and pathway subscale scores range from 3 to 18. Higher scores indicate higher levels of hope. Psychometric analyses indicate that the scale demonstrates acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach alphas range from .72 to .86), test-retest reliability (r > .70), as well as construct, criterion, discriminant, and convergent validity (Snyder et al., Citation1997; Valle et al., Citation2004).

Resilience

The Resilience Scale (RS-25; Wagnild & Young, Citation1993), developed for youth 13 years and older, was used to assess participants’ resilience. The RS-25 scale conceptualises resilience as a trait and consists of two subscales: Personal Competence (17 items, e.g. ‘I can get through difficult times because I’ve experienced difficulty before’) and Acceptance of Self and Life (8 items, e.g. ‘I am friends with myself’). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The RS-25 total score ranges from 25 to 175, Personal Competence ranges from 17 to 119, and Acceptance of Self and Life ranges from 7 to 56, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. Previous research indicates that the scale has acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach alphas range from .76 to .90) and is positively correlated with physical health, morale, and life satisfaction and negatively correlated with depression and perceived stress (Wagnild & Young, Citation1993). The RS-25 scale has been used in studies with adolescents (Wagnild, Citation2009), and the shortened version of the RS (i.e. RS-14) has be used with youth offenders (Fougere et al., Citation2015).

Goals

The Bridge Drawing with Path (BDP; Darewych, Citation2013) art-based assessment was used to creatively explore participants’ goals. When administering the BDP, participants are given a No. 2 lead pencil and a sheet of 8.5 inch x 11 inch white paper and directed to ‘Draw a bridge from someplace to someplace. The bridge connects to a path. Draw the path and write where the path leads you to’ (Darewych, Citation2013, p. 87). Upon completion, participants are asked to place a dot to depict where they are in the drawing. The BDP rating scale includes six image categories (i.e. axis of paper, image directionality, placement of self in picture, solidity of bridge attachments, type of bridge depicted, matter down under the bridge) and one written association category. The BDP places greater emphasis on the written association or narrative attached to the path end-point rather than the image category. The BDP has been administered to institutionalised youth orphans (Darewych, Citation2013) and with adults as a complementary measure with other hope and life goals (Darewych & Brown Campbell, Citation2016; Wilkinson & Chilton, Citation2018).

Client satisfaction

A Client Satisfaction Survey was designed to capture participants overall experience of the 12 weekly individual art therapy sessions. The survey included eight structured questions: 1. I thought art therapy was a good fit for me, 2. I looked forward to each art therapy session, 3. The length of time of the art therapy sessions was long enough, 4. The environment in the sessions was positive, 5. Art therapy provided a safe environment to express my emotions, 6. I was involved in planning and developing my goals for the programme, 7. The art therapist provided me with support throughout the duration of the art therapy programme, 8. Overall, I am satisfied with art therapy, and two open-ended questions: ‘What is the most helpful or useful aspect of art therapy?’ and ‘What could be improved?’ The survey was administered to participants by the art therapist at the end of the 12th session.

Procedure

Following approval of the study by the Centre’s research ethics board, participants were recruited by means of a study information flyer. Participants who volunteered for the study completed the study Information and Consent Form with the support of a legal guardian which highlighted the purpose of the research, anticipated study benefits, art therapy duration, and participants’ ability to terminate the study participation at any time. Participants attended 12 weekly one hour, face-to-face, individual art therapy sessions which were facilitated by the Centre’s full-time art therapist (first author) and occurred in the Centre’s art therapy room. To enhance safety protocol, the art therapist limited the type of art materials, monitored the art materials during each session to reduce the possibility of harmful occurrences, and established firm rules based on programming policies such as the creation of art work depicting gang symbols, weapons, violence and/or sexual content was strictly prohibited.

The objectives of the first six art therapy sessions were to establish a safe and supportive therapeutic space wherein participants could establish rapport with the therapist, explore a variety of safe art media (i.e. chalk and oil pastel, clay, papier-maché, fabric, paint and markers, collage), and engage in self-expression both verbally and through the creative process. The objectives of the subsequent six art therapy were to invite participants to complete art-based interventions which focused on enhancing participants’ levels of communication, hope, and emotional regulation in order to increase resiliency by making-meaning of their lived experience. Once therapeutic rapport was established, participants were encouraged during session’s six to 12 to begin unpacking their intense emotions and traumatic experiences, and gain awareness of their hopes, strengths, healthy coping strategies, and future orientations. A summary of the arts-based interventions introduced to the youth related to the art therapy treatment objectives are listed in .

Table 1. Art-based interventions over 12 weeks.

Participants completed the CHS (Snyder et al., Citation1997), RS-25 (Wagnild & Young, Citation1993) and BDP (Darewych, Citation2013) at the beginning of the first and at the end of the 12th session providing pre- and post- art therapy treatment data. At the end of the 12th session, participants completed the Client Satisfaction Survey as well. In order to maintain confidentiality and participant’s identities, all paper-and-pencil measures were administered and collected by the Centre’s art therapist. The study was completed over a six-month period from January to July 2017.

Data analysis

The data were analysed by the Centre’s Research and Evaluation team using the R Programming Language (R Core Team, Citation2020). Paired t-tests were conducted on the data across pre- and post- test to examine potential differences in measurement ratings. Paired standardised mean differences with a Hedge’s correction and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the effsize package in the R programming language (Torchiano, Citation2020). Both pre- and post- treatment measurement data were graphed in order to monitor and evaluate the impact of the 12 individual art therapy sessions.

Participants BDP image category data were independently coded by three blinded raters. Raters one and two were art therapists trained in art-based assessments, while rater three was an in-house psychologist at the Centre who received BDP coding training from rater one (second author). Coded data were inputted into an Excel rating sheet. Discrepancies in the BDP ratings were discussed among the three raters to arrive at a collective score for each image category for each participant. Interrater agreement analysis using Cohen’s Kappa was used to determine consistency amongst all three raters for all six BDP image categories. Cohen’s Kappa is a statistical measure of interrater agreement which ranges from 0 to 1.0 and takes change agreement into account (Landis & Koch, Citation1977). For this study, a Kappa value of 0.6 or greater was accepted as good level of agreement. Kappa was computed for each variable at pre- and post- time point. Upon completion of the BDP image category rating process, statistical inferential analysis was performed to determine if there was a change within each image category between the two time points. Cochran’s Q test was conducted to compare the BDP nominal data in the repeated-measures design. Lastly, thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was used to analyse participants’ written responses associated with the BDPs.

Percentage of participants reporting positive, neutral, and negative satisfaction on the Client Satisfaction Survey were calculated. Participants’ written responses on the survey were coded and synthesised into common themes.

Results

Hope and resilience

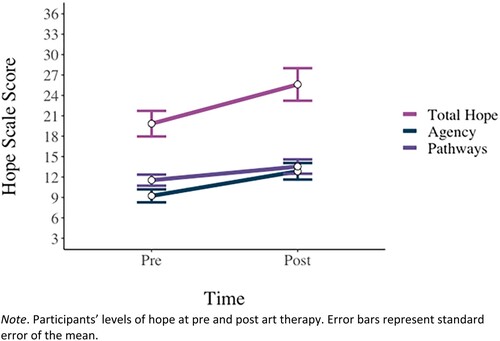

Descriptive statistics of hope and resilience, including their subscale scores at pre- and post- test, are presented in . Results of a paired t-test showed that mean levels of hope significantly increased from pre- to post- test, t(12) = 3.93, p = .002, and the effect was moderate in size, d = 0.66, 95% CI [0.28, 1.04]. Put another way, after participating in the 12 weekly individual art therapy sessions, participants’ average level of hope increased by 29.07% (see ). Results of the subscale differences suggested that agency thinking, t(12) = 4.42, p < .001, d = 0.82, 95% CI [0.39, 1.26] increased more strongly than thinking about pathways, t(12) = 2.63, p = .022, d = 0.53, 95% CI [0.09, 0.98] from pre- to post- test. Therefore, art therapy may be most efficacious in increasing an individual’s motivation of engaging in goal directed behaviours, rather than a planning of concrete ways to meet one’s goals.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics at pre and post art therapy (N = 13).

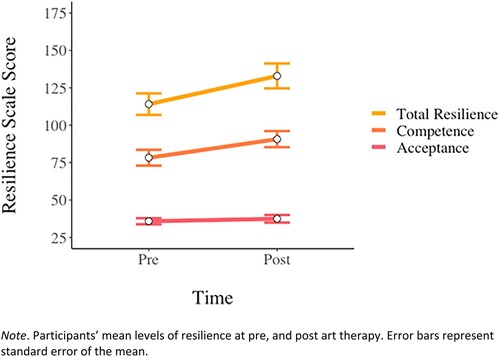

displays the participants’ resilience scores at pre- and post-test. Results of a paired t-test showed that mean levels of resilience significantly increased from pre- to post- test, t(12) = 3.34, p = .006, and the effect was moderate in magnitude, d = 0.62, 95% CI [0.20, 1.04]. Put another way, after participating in the 12 weekly art therapy sessions, participants’ average level of resilience increased by 16.52%. Pre–post differences in the subscale scores indicated that personal competence, t(12) = 3.32, p = .006, d = 0.60, 95% CI [0.20, 1.01], % = 16.17%, but not acceptance of life and self, t(12) = 0.96, p = .357, d = 0.18, 95% CI [−0.21, 0.57],

% = 4.62%, increased meaningfully after participating in art therapy. Therefore, art therapy may be best suited to increase a youth’s sense of self-reliance, independence, determination, perceived invincibility, mastery, resourcefulness, and perseverance, rather than a sense of adaptability, balance, flexibility, and a balanced perspective of life (see Wagnild & Young, Citation1993).

Goals

The Kappa results of the interrater analysis for the BDP are displayed in . Average Kappa agreement ranged from fair agreement (0.26) almost perfect agreement (0.91). Interrater agreement was high (substantial, almost perfect or perfect agreement) for placement of self in the picture, bridge connection, bridge type, and matter drawn under bridge. Weaker interrater agreement was associated with coding of the axis of the paper and directionality of the picture.

Table 3. Interrater agreement on coding of BDP categories.

Percentage of participants in each coding category at BDP pre- and post- test are presented in . Based on Cochran’s test analysis, there was no statistically significant difference between the pre- and post- test BDP image categories.

Table 4. Percentage of participants under each BDP rating category.

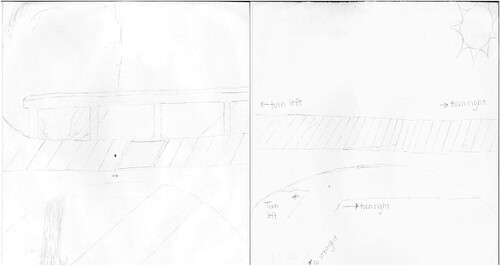

The four most common written comments in the pre- BDPs were path leading to home (31%), better life (15%), family (15%), and somewhere/nowhere (15%). The four most common written comments in the post- BDPs were path leading to home (23%), future (15%), better life (15%), and family (15%). One of the participant’s post- BDP presented suicidal thoughts. illustrates one of the participants’ pre- BDP drawing leading to somewhere and their post- BDP drawing embracing the future.

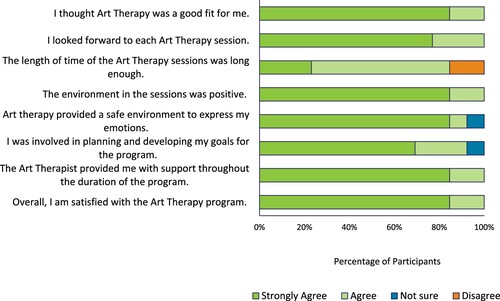

Satisfaction with art therapy

presents participants’ satisfaction with different aspects of the art therapy sessions. Overall, participants reported high satisfaction with the art therapy sessions. All participants strongly agreed or agreed that (1) the art therapy session was a good fit for them, (2) they looked forward to the session, (3) the environment of the art therapy programme was positive, (4) they had received support from the art therapist throughout the art therapy programme, and (5) they were overall satisfied with the art therapy programme. Most participants (92.3%) believed that the art therapy sessions provided a safe environment to express their emotions and that they were involved in planning and developing their goals for each session. Relatively, while most clients were satisfied with the length of the art therapy sessions; approximately 15% reported that sessions were not long enough.

Out of 13 participants, 12 provided written feedback on the question ‘What is the most helpful or useful aspect of art therapy?’ and eight provided feedback on the question ‘What could be improved?’ summarises participants’ written responses for the two questions. In general, participants provided positive feedback about the art therapy sessions. The majority of clients (84.6%) thought that art therapy helped them understand themselves, and manage and express their emotions and feelings. These findings are consistent with the goals of the art therapy sessions. In addition, one participant perceived their positive relationship with the therapist as the most helpful aspect of the art therapy programme. Relatively fewer participants wrote suggestions for improvements. Many participants left the question blank or wrote ‘nothing’, which might further indicate their overall satisfaction with art therapy. Two participants suggested to have longer therapy sessions, which echoed participants’ slightly lower satisfaction ratings on the length of sessions as shown in . There were also suggestions to have music and fewer restrictions in sessions.

Table 5. Participants’ written responses on the Client Satisfaction Survey.

Discussion

The current study was the first in Canada to examine hope and resilience outcomes following art therapy for youth residing within a secure care centre. The CHS outcomes found that, after participating in the programme, self-reported hope increased by more than one-half of a standard deviation, a moderate effect. Although the confidence interval of the effect was wide, capturing both a small and very large effect, we maintain that even small increases of hope are important for a secure treatment population. This is because hope has been found to predict lower levels of psychological distress, such as sadness, fear, and hostility (Ciarrochi et al., Citation2015) and lower violent behaviour (Stoddard et al., Citation2011) and is thus a protective factor for this vulnerable population. Results also indicated that the agency component of hope, the perceived capacity ‘to reach desired goals’ (Snyder, Citation2002, p. 251), rather than the pathways component of hope, or the ‘production of one plausible route’ to one’s goals (Snyder, Citation2002, p. 251), increased more substantially after participating in the art therapy sessions. In this way, art therapy may prepare youth for their transition back into society (Darewych, Citation2013) by fulfilling their ‘basic psychological needs’ (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008) for autonomy or agency. According to self-determination theory, autonomy is an innate psychological nutrient that is essential for ‘ongoing psychological growth, integrity, and well-being’ (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000, p. 229) and that when people are autonomously motivated, ‘they experience volition, or a self-endorsement of their actions’ (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008, p. 183). In this way, the current research provides preliminary evidence that art therapy may be beneficial in fulfilling one’s need for autonomy, thereby fostering a sense of self-determination for youth in secure care.

Results also suggested that, after participating in the art therapy sessions, self-reported resilience increased by more than one-half of a standard deviation. This finding is important because resilience has been found to be a protective factor against distress, whereby it moderates or weakens the association between adverse childhood events and psychological distress (Clements-Nolle & Waddington, Citation2019), and it predicts lower loneliness, hopelessness, and life-threatening behaviours (Rew et al., Citation2001). Results also demonstrated that the personal competence component of resilience, rather than an acceptance of life and self, increased more strongly after participating in the programme. Similar to a sense of autonomy or agency, fulfilling one’s need for competence is essential for self-determination and, once fulfilled, leads one to experience their behaviour as being intrinsically motivated rather than being regulated by other sources external to the self (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). More specifically, satisfaction of the need for competence involves ‘feeling effective in one’s interactions with the social environment and experiencing opportunities to exercise and express one’s capacities’ (Ryan & La Guardia, Citation2000, p. 150), which is necessary for one to experience an ongoing sense of integrity and well-being. Therefore, from a self-determination perspective, the current research provides preliminary evidence that art therapy may be beneficial by also fulfilling one’s need for competence.

Regarding the BDP outcomes, there was no statistically significant difference between the pre- and post- test BDP image categories. This finding emphasises the need for further studies in the field of art therapy investigating the potential of using the BDP art-based assessment as a pre- and post- treatment measure for evaluating individual’s goals, self-determination, and future orientations. The two most common written comments for the pre- and post- BDPs were path leading to home and family. These two themes emphasise the importance of youth remaining connected with their family members and other significant individuals within their social circle while residing in a secure care environment. In the BDP written associations, the post- BDP pathways presented more pathways leading to ‘future’ and a ‘better life’ and less pathways leading to ‘somewhere’ or ‘nowhere’ in comparison to pre- BDP pathways. Hence, participants showed greater future visions at the end of the 12 individual art therapy sessions. One of the participant’s post- BDP presented suicidal thoughts. This particular drawing provided the art therapist with the opportunity to collaborate with the Centre’s Wellness Department in order to complete a risk assessment and safety plan including ways to cope with these overwhelming thoughts and feelings. This finding is consistent with Darewych’s (Citation2013) study which showed that the BDP has the potential to assess for suicidal thoughts. Consequently, suicide prevention efforts in forensic mental health centres and other secure care environments may benefit from incorporating the BDP art-based assessment.

As for the direct Client Satisfaction Survey outcomes, participants overall reported high satisfaction with art therapy and their written responses support Gussak’s (Citation2020) and Smeijsters et al.’s (Citation2011) notion that art therapy enables youth in secure care to express their emotions creatively and verbally, and improve their sense of identity and self-worth. The suggestions around incorporating music in the sessions support Kõiv and Kaudne’s (Citation2015) recommendation of implementing integrated expressive arts therapies programme for youth in secure care.

Limitations and future research

Due to a lack of a control group, it is unclear whether improvements in hope and resilience were the result of the art therapy sessions or other services the participants were receiving at the Centre. It is recommended that future studies utilise a group design with a control group to evaluate the effects of art therapy on youth residing in a secure care environment.

Secondly, the sample size was small and the demographic characteristics between the participants varied quite substantially. Thus, future research should extend the data collection period to strengthen the sample size and the generalizability of the results.

Lastly, the art therapist in the current study administered all measurements and facilitated the twelve art therapy sessions. In order to mitigate potential bias, future research should replicate the results and include a research assistant who is blind to the purpose of the research.

Conclusion

This study permitted the researchers to monitor the youth’s progress throughout the 12 weekly individual art therapy sessions. The art therapy treatment enabled the youth to perceive and communicate their present and future life goals while reflecting on the people, places, and things that give them life meaning and a sense of hope. Overall, the youth in the study showed higher hope, resilience, and goal-directed thinking at the end of the 12 art therapy sessions than when they started. The Clients’ Satisfaction Survey feedback indicated that the youth enjoyed the art therapy sessions and perceived positive outcomes in terms of management and expression of emotions. Secure care environments may benefit from incorporating art therapy as a rehabilitation treatment to improve youths’ levels of hope, resilience, self-esteem, self-determination, goals, and future pathways.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the youth who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2023.2180923)

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Barbara Collins

Barbara Collins, MA, RP, RCAT, holds a Master’s degree in Spiritual Care and Psychotherapy from Wilfrid Laurier University and a diploma in art therapy from the Toronto Art Therapy Institute. She is currently working at a large mental health organisation in Canada.

Olena Helen Darewych

Olena Darewych, PhD, RP, RCAT, is a Registered Psychotherapist in Ontario, a Registered Canadian Art Therapist, and Adjunct Faculty at Martin Luther University College-Wilfrid Laurier University. She is also a Past President of the Canadian Art Therapy Association. Her research and clinical work explores the intersection between art therapy and positive psychology.

Daniel J. Chiacchia

Daniel J. Chiacchia, MA, holds a Master’s degree in Social and Personality Psychology from York University and he is currently a Research Advisor at a large mental health organisation in Canada.

References

- Baillie, C. (1994). Art as therapy in a young offender institution. In M. Liebmann (Ed.), Art therapy with offenders (pp. 57–76). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Bennink, J., Gussak, D. E., & Skowran, M. (2003). The role of the art therapist in a juvenile justice setting. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 30(3), 163–173. doi:10.1016/S0197-4556(03)00051-0

- Benson, E. S. (2003, July). Rehabilitate or punish? Monitor on Psychology, 34(7), 46. https://www.apa.org/monitor/julaug03/rehab.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., Kashdan, T. B., Heaven, P. C., & Barkus, E. (2015). Hope and emotional well-being: A six-year study to distinguish antecedents, correlates, and consequences. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(6), 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1015154

- Clements-Nolle, K., & Waddington, R. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and psychological distress in juvenile offenders: The protective influence of resilience and youth assets. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.09.025

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

- Darewych, O. H. (2013). Building bridges with institutionalized orphans in Ukraine: An art therapy pilot study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(1), 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2012.10.1001

- Darewych, O. H. (2020). Positive psychology arts activities: Creative tools for therapeutic practice and supervision. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Darewych, O. H., & Brown Campbell, K. (2016). Measuring future orientations and goals with the bridge drawing: A review of the research [Le dessin du pont comme mesure des orientations futures et des buts : une revue de la recherche]. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 29(1), 30–37. doi:10.1080/08322473.2016.1166010

- Darewych, O. H., & Riedel Bowers, N. (2018). Positive arts interventions: Creative clinical tools promoting psychological well-being. International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape, 23(2), 62–69. doi:10.1080/17454832.2017.1378241

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. doi:10.1037/a0012801

- Denborough, D. (2008). Collective narrative practice: Responding to individuals, groups, and communities who have experienced trauma. Dulwich Centre Publications.

- Donovan, R. (2022). Art therapy with juvenile offenders-building on community, strengths and self-esteem: A literature review. Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 585. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/585

- Fougere, A., Daffern, M., & Thomas, S. (2015). Does resilience predict recidivism in young offenders? Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 22(2), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2014.936333

- Gussak, D. E. (2020). Art and art therapy with the imprisoned re-creating identity. Routledge.

- Gussak, D. E., & Virshup, E. (1997). Drawing time: Art therapy in prisons and other correctional settings. Magnolia Street Publications.

- Hanon, L. (2016, February 7). Youth secure care: The politics of forced treatment. McGill Journal of Law and Heath. Blog. https://mjlh.mcgill.ca/2016/02/07/youth-secure-care-the-politics-of-forced-treatment/.

- Hartz, L., & Thick, L. (2005). Art therapy strategies to raise self-esteem in female juvenile offenders: A comparison of art psychotherapy and art as therapy approaches. Art Therapy, 22(2), 70–80. doi:10.1080/07421656.2005.10129440

- Kõiv, K., & Kaudne, L. (2015). Impact of integrated arts therapy: An intervention program for young female offenders in correctional institution. Psychology (savannah, Ga ), 6(1), 1–9. doi:10.4236/psych.2015.61001

- Kramer, E. (2016). Sublimation and art therapy. In J. A. Rubin (Ed.), Approaches to art therapy (pp. 87–100). Brunner/Mazel.

- Lake, A. (2019). Criminalization of minority youth in the youth justice system in Canada. Canadian Journal of Undergraduate Research, 4(1), 15–18.

- Lamberti, J. S. (2016). Preventing criminal recidivism through mental health and criminal justice collaboration. Psychiatric services, 67(11), 1206–1212. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500384

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. doi:10.2307/2529310

- Larose, M. E. (1988). The use of art therapy with juvenile delinquents to enhance self-image. The Psychotherapy Patient, 4(2), 161–167. doi:10.1300/J358v04n02_15

- Liebmann, M. (1986). Art therapy for groups. Brookline Books.

- Liebmann, M. (Ed.). (1994). Art therapy with offenders. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Meekums, B., & Daniel, J. (2011). Arts with offenders: A literature synthesis. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38(4), 229–238. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2011.06.003

- Moon, B. L. (1998). The dynamics of art as therapy with adolescents. Charles C Thomas Publisher.

- Persons, R. W. (2009). Art therapy with serious juvenile offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 53(4), 433–453. doi:10.1177/0306624x08320208

- Pratt, D., & Foster, E. (2020). Feeling hopeful: Can hope and social support protect prisoners from suicide ideation? The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 31(2), 311–330. doi:10.1080/14789949.2020.1732445

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Rew, L., Taylor-Seehafer, M., Thomas, N. Y., & Yockey, R. D. (2001). Correlates of resilience in homeless adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(1), 33–40. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00033.x

- Rubin, J. A. (Ed.). (2016). Approaches to art therapy: Theory & technique (3rd ed.). Brunner-Routledge Publishers.

- Ryan, R. M., & La Guardia, J. G. (2000). What is being optimized? Self determination theory and basic psychological needs. In S. H. Qualls & N. Abeles (Eds.), Psychology and the aging revolution: How we adapt to longer life (pp. 145–172). American Psychological Association.

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihályi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

- Smeijsters, H., Kil, J., Kurstjens, H., Welten, J., & Willemars, G. (2011). Arts therapies for young offenders in secure care—a practice-based research. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38(1), 41–51. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2010.10.005

- Snyder, C. R. (1994). The psychology of hope: You can get there from here. Free Press.

- Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01

- Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

- Snyder, C. R., Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Rapoff, M., Ware, L., Danovsky, M., Highberger, L., Rubinstein, H., & Stahl, K. (1997). The development and validation of the children's Hope Scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(3), 399–421. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/22.3.399

- Snyder, C. R., LaPointe, A. B., Crowson, J. J., & Early, S. (1998). Preferences of high- and low-hope people for self-referential input. Journal of Cognition and Emotion, 12(6), 807–823. doi:10.1080/026999398379448

- Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25338. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

- Statistics Canada. (2022). Table 35-10-0005-01 Youth admissions to correctional services. https://doi.org/10.25318/3510000501-eng

- Stoddard, S. A., Zimmerman, M. A., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2011). Thinking about the future as a way to succeed in the present: A longitudinal study of future orientation and violent behaviors among African American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3), 238–246. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9383-0

- Torchiano, M. (2020). Package ‘effsize’: Efficient effect size computation. R package version 0.8.1. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/effsize/index.html

- Valle, M. F., Huebner, E. S., & Suldo, S. M. (2004). Further evaluation of the Children's Hope Scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 22(4), 320–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/073428290402200403

- Wagnild, W. M. (2009). The Resilience Scale user’s guide for the US English version of the Resilience Scale and the 14-item Resilience Scale (RS-14). The Resilience Center.

- Wagnild, W. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1, 165–178.

- Wilkinson, R. A., & Chilton, G. (2018). Positive art therapy theory and practice: Integrating positive psychology with art therapy. Routledge.