ABSTRACT

Background

Art therapy with an autistic person with learning disabilities: communication and emotional regulation.

Context

This study focuses on a six-week art therapy programme with an autistic adult, who also has a learning disability, anxiety, and sensory processing disorder. Can art therapy be an effective therapeutic modality to help them develop their communication and emotional regulation abilities?

Approach

A single-case study approach was used and contextualised using the ‘Interactive Square approach’ introduced by Bragge and Fenner ([2009]. The emergence of the ‘interactive square’ as an approach to art therapy with children on the autistic spectrum. International Journal of Art Therapy, 14(1), 17–28.). An open-ended interview was conducted and utilised an arts-based narrative inquiry to code the data from the interview. Using Lieblich et al. ([1998]. Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Sage Publications, Inc.) model of narrative analysis.

Outcomes

The study found that art therapy could contribute to the development of communication skills for the client and assist with emotional regulation strategies. While humour and the spontaneous element of the art materials also had a beneficial impact.

Conclusions

Art Therapy can thus reduce the need for avoidant coping strategies and cognitive suppression, which lead to increased anxiety and externalising behaviour.

Implications for Research

These findings highlight important conclusions, and more art therapy research with autistic people with learning disabilities is warranted.

Plain-language summary

This article examines the initial impact of art therapy with an adult diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The study investigated whether art therapy could be an effective way of helping that person with communication and managing their emotions.

The first part of the research was to gather data from the art therapy sessions. Based on the interactive square analysis method introduced by Bragge and Fenner ([2009]. The emergence of the ‘interactive square’ as an approach to art therapy with children on the autistic spectrum. International Journal of Art Therapy, 14(1), 17–28.). The second part of the research was to hold an audio interview with the client and analyse the recording using Liebmann’s ([2008]. Art therapy and anger. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.) model of narrative analysis.

The findings found that art therapy contributed to the development of communication skills. The sensory qualities of the art materials encouraged communication. Art therapy could help a person to understand and manage their emotions.

This study highlights important conclusions that can help autistic people with learning disabilities.

© 2023 British Association of Art Therapists

Introduction

This article describes a qualitative research project undertaken for an MRes from the University of London, examining the impact of a short-term art therapy intervention on an autistic adult with a learning disability.

This study responds to the pressing need in the UK to develop effective strategies to support autistic people with learning disabilities (Autism Act, UK Government legislation, Citation2009), as many have co-morbid conditions such as mental health difficulties.

Reports in the mainstream media have highlighted an urgent need for more effective psychological treatments for autism, learning disabilities, and complex needs. After a BBC Panorama investigation into one assessment and treatment unit (ATU) (BBC news article, 23rd of May Citation2019).

On the 21st of May 2019, the Care Quality Commission published an interim report which found many hospital environments and community placements to not be suitable, with staff lacking the training to work with patients with complex needs (CQC Interim Report, Citation2019).

So investigating treatment modalities that cater to these complex needs is urgent, with a lack of research on autistic adults with learning disabilities that suffer from emotional problems (Sarris, Citation2017). Autistic young people have increased risks of psychiatric hospitalisation because of aggressive and self-injurious behaviour (Gupta et al., Citation2018). There is also the risk that when community placements break down, this can give rise to even greater stresses, with the risk of PTSD.

According to the UK National Autistic Society, autistic people make up 58 percent of people in in-patient hospitals (National Autistic Society, UK, 17th of February Citation2022), and they call for investment in services that meet the needs of autistic children and adults. In the US, autistic children are six times more likely to be admitted to psychiatric hospitals than children without ASD (McGuire et al., Citation2015). They discuss that standard verbal therapies provided in some units are less effective for autistic children with ASD and intellectual disabilities.

Traditionally research on autistic people has focused on identifying ‘deficits’ such as difficulties in socialisation, empathy, and restrictive behaviours (Mazefsky et al., Citation2012; Wing & Gould, Citation1979). This research can pathologise autistic populations and ignore their subjective lived experience (Milton & Bracher, Citation2013). Researchers have argued for studies on maladaptive emotional responses such as heightened anxiety and anger (Mazefsky et al., Citation2012; Samson et al., Citation2014). So switching the focus to investigating subjective experiences can lead to developing more practical therapeutic strategies to improve psychological well-being (McLeod, Citation2011).

Therefore, this study aims to examine the real-life experiences of the participant and the practitioner and link them to theoretical perspectives. With the core action research aim of developing ‘more efficient and effective practice’ (Noffke & Somekh, Citation2005, p. 90). The role of the practitioner-researcher in this study links theory to practice (Costello, Citation2003, pp. 19–20), testing approaches in the working environment, away from the standard artificial experimental setup. Focusing on the concepts of communication skills and emotional regulation has developed from understanding more about the individual’s presenting challenges and experiences.

Research question

In this study, I have examined the impact of art psychotherapy with an autistic adult diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). What aspects of this treatment modality can aid communication difficulties and emotional regulation? Does art therapy help to address some of the co-morbidities associated with ASD, such as learning disabilities, anxiety, and sensory difficulties?

The study focused on the processes during the art therapy sessions, engagement with the art materials, and analysis of the interactive components and whether they facilitate the development of communication abilities and emotional regulation strategies.

Literature review

Understanding autism spectrum disorder

Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neuro-developmental condition characterised by persistent problems in social communication, social-emotional reciprocity, and maintenance of relationships, as well as restricted patterns of behaviour and interests, with a high degree of rigidity to fixed routines and rituals (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

This definition acknowledges sensory sensitivity and emotional issues related to communication and resistance to change but does not acknowledge that autistic people present problems with anxiety, depression, emotional regulation, and anger. (Cai et al., Citation2018; Fenning et al., Citation2018; Mazefsky et al., Citation2012; Samson et al., Citation2014)

Often challenges with communicating and understanding the feelings of others (Baron-Cohen et al., Citation1985) can lead to less interaction and social issues (Mundy, Citation1995; Spence, Citation2003), social camouflaging (Hull et al., Citation2017), with increased manifestations of mental health difficulties for autistic people with learning disabilities (Davis et al., Citation2011; Vasa et al., Citation2018). Anxiety can trigger task avoidance, obsessions, fixations, and emotional outbursts. (Nadeau et al. Citation2013; Sarris, Citation2018).

What is emotional regulation?

Emotional regulation is the process of evaluating and regulating our emotional reactions according to the social needs of the environment or context (Goldsmith & Kelley, Citation2018; Laurent & Rubin, Citation2004; Weiss et al., Citation2014), with strategies including cognitive re-appraisal and suppressive measures (Gross, Citation1998). Autistic people use less adaptive re-appraisal and more maladaptive ER strategies such as suppression and withdrawal (Weiss, 2people015).

Sensory processing difficulties

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) refers to problems processing sensory stimuli from the body or the outside environment (Owen et al., Citation2013). Dysfunctional sensory responses are more common for autistic children (Kientz & Dunn, Citation1997) and include hyper (oversensitive), hypo (under-sensitive), and sensory seeking (Posar & Visconti, Citation2018; Thye et al., Citation2018).

Sensory difficulties can exacerbate ASD symptoms and impair emotional regulation with the internalisation of stress (Rieffe et al., Citation2008). A review of treatments found that sensory integration treatments for children had positive effects and sensory interventions for adults had mixed results (Case-Smith et al., Citation2015), highlighting a need to find new strategies for adults to complement existing techniques.

Broadening approaches to people with ASD

Treatments that cater to people with ASD and co-morbid mental health challenges include Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and recommended by NICE guidelines. Although, researchers have suggested that there is a need for additional treatment for heightened arousal and aggressive outbursts (Samson et al., Citation2014; Mazefsky et al., Citation2013; Weiss et al., Citation2018). CBT may not always be suitable for people with ASD and learning disabilities due to difficulties identifying and describing feelings and grasping abstract concepts (Irvine & Beail, Citation2016). So it is imperative to investigate how non-verbal therapeutic strategies can help to address their communication and sensory needs to facilitate effective emotional regulation.

Art therapy with people with ASD

Art Therapists advocate art therapy as a valuable addition to treatment options, citing it as an effective and non-threatening way for autistic people with LD. to communicate and express their emotions (Gazeas, Citation2012; Malchiodi, Citation2003; Martin, Citation2009b). The benefits of art therapy outlined are that it can make abstract concepts more concrete (Elkis-Abuhoff, Citation2008), facilitate communication and aid emotional regulation (Richardson, Citation2015), and assist developmentally with symbol formation and socialisation (Martin, Citation2009a)

Emery proposes that art-making can help develop object constancy and a sense of self that can help one relate to others (Emery, Citation2004, p. 144; Gazeas, Citation2012). The use of art materials thus can help an autistic child move beyond repetitive behaviours and encourage sensory-perceptual and cognitive development (Evans, Citation1998; Evans & Dubowski, Citation2001: Gilroy, Citation2006; Haque & Haque, Citation2015; Regev et al., Citation2013).

The hands-on materials and creative process can stimulate the need to communicate with the outside world (Osborne, Citation2003), and provide a way of building social relationships without the difficulty of verbal language processing (Alter-Muri, Citation2017). Art Therapy can provide sensory experiences that meet sensory integration needs (Wallace, Citation2015), facilitating communication and aiding emotional regulation (Richardson, Citation2015).

For people with learning disabilities, art therapy can also enhance the capacity to reflect and express feelings through different forms of communication (Rees, Citation1995), enabling interaction and communication (Hackett et al., Citation2017).

Malhotra (Citation2019) discusses the common misconception that autistic people cannot empathise, highlighting research that people with ASD have difficulties processing emotional material and showing empathy due to a lack of flexibility and cognitive memory. They demonstrate the role of puppets and mirroring in improving social interaction and self-awareness (183).

Art therapy and emotional regulation

Emotional regulation strategies in art therapy equate to a conscious focus and reflection before and after art-making (Haeyen et al., Citation2018, p. 10). Emotional content can be explored and processed through cognitive re-appraisal when reflecting on themes, metaphors, and the process.

Gruber and Oepen (Citation2018) found that art-making is more effective for ER than other psychological therapies, with the distraction strategy (Gross, Citation1998) being more successful. They point to research that expressing emotion through art is more beneficial than ‘venting’.

So art therapy may be more valid as an emotional regulation strategy for autistic people with learning disabilities as it relies less on cognitive capabilities for re-appraisal and provides an immersive distraction technique. Incongruous and spontaneous processes in the art can be humorous and reduce rigidity, as research has shown that autistic people can enjoy visual, incongruent humour where unexpected things happen (Kana & Wadsworth, Citation2012; Samson et al., Citation2013; Weiss et al., Citation2013).

Other research related to emotional regulation includes Springham et al. (Citation2012), who found that art therapy can assist in helping clients develop mentalization capabilities. Art Therapists have also documented their work with anger management (Liebmann, Citation2008; Malchiodi, Citation2003), which has benefits for autistic people who can struggle with anger.

Further art therapy research with ASD

Case descriptions of art therapy with autistic people were reviewed by Schweizer et al. (Citation2014, Citation2017), with art therapy contributing to a more flexible attitude; with sensory experiences improving attention; assisting with social-communicative problems, and reducing restricted patterns of behaviour.

Regev et al. (Citation2013) research investigated the work of 10 art therapists, with common themes of art assisting communication; and activating senses. The artwork is a third-party mediator in the client-therapist relationship, with joint drawing allowing communication and joint attention.

Van Lith et al. (Citation2017) recommend a top-down approach related to the Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC) (Kagin & Lusebrink, Citation1978), gradually moving toward using more sensory and kinesthetic materials after the relationship-building phase (184).

Art therapy, ASD and the attachment system

According to attachment theory, successful child and caregiver bonding is crucial for psycho-social development (Bowlby, Citation1968; Nolte et al., Citation2011). Art Therapists have proposed that art therapy can help to restore attachment systems impaired by adverse childhood experiences, which can help develop communication skills and emotional regulation; (Naff, Citation2014).

We have seen that sensory dysfunction and a lack of self-regulation can inhibit the development of attachments. Durani (Citation2014) describes an autistic child blocking sensory input as a defense against unpleasant sensations. Art activity and attunement with an art therapist can improve sensory dysfunction and self-regulation.

Art therapy, social communication, and the triangular relationship

In art therapy, the art object provides a third space for the client to ‘project’ thoughts and feelings, provides a transitional space (Winnicott, Citation1972), and can be a space for the client and therapist to interact without direct verbal interaction (Isserow, Citation2008, p. 34). This triad of patient, art object, and therapist is a fundamental concept in art therapy, (Case, Citation2000; Dalley et al., Citation1993; Schaverien, Citation2000; Wood, Citation1990)

For autistic people, this reciprocal and sensory interaction can be a way of tolerating the presence of another and regulating sensory input (Evans & Dubowski, Citation2001, pp. 97–98; Regev et al., Citation2013). Joint art making encourages interactive sensory experiences and strengthens the sense of self (Regev et al., Citation2013; Sarah Furneaux-Blick, Citation2019).

Materials and methods

Participant information

The participant in the study was a 27-year-old adult with a diagnosis of autism and learning disabilities. He has anxiety, a sensory processing disorder, and externalising behaviour. I have called him Stephen for this study.

Stephen lives in a residential service and receives excellent support from staff and a behavioural support team. Stephen gave his consent with help from his parents, with accessible information provided.

Procedures

The weekly art therapy sessions took place in a familiar activity room in the residential home. The participant got to know the therapist before the sessions, helping them to feel more confident. The video recorder was in a visible place.

The session structure drew on recommendations by Van Lith et al. (Citation2017) with clear beginning and endings to the sessions, with space to be spontaneous and to access sensory tolerance. Directive and non-directive approaches would be at the client's own pace.

The researcher utilised a research journal and wrote notes reflecting on the process of the art making, artwork created, the space, the non-verbal and verbal interactions, and considerations of transference and countertransference (Dalley & Case, Citation2003; Poensett, Parker, Hawtin, & Collins, Citation2006, p. 83).

The interview happened after the sessions with a clear gap between the two. The interviewer did not bring any new ideas or interpretations and was not a therapy session. An interview observer was asked to ensure this and reassure the client if needed. The interview was audio-taped and transcribed using the standard verbatim method and with notes to indicate expressive verbal tones from the participant.

Analytic methods

The enhanced methods of the video based interactive square and arts-based narrative analysis were added to the case study and the interview analysis to add rigour to the study. See .

Table 1. Structure of the research project.

Case studies

This study uses a case study methodology to investigate the impact of the art therapy sessions. Art therapy case studies examine the visual material and the client’s responses to the art-making in the socio-cultural and institutional context. They analyse the material retrospectively from the clinical notes and the therapist’s subjective comments (Gilroy, Citation2006; Kapitan, Citation2015).

Art Therapy case studies can lack rigorous methodologies (Edwards, Citation1999), omit the client input (Malchiodi, Citation1998), and have biases (Kapitan, Citation2015, pp. 104–111; Nisbet & Watt, Citation1984). While advantages are they fit an inquiry into a real-life context, as opposed to the contrived contexts of an experiment or survey (Yin, Citation1994), and can highlight best practices in therapeutic interventions.

Kapitan recommends Stake’s (Citation1995) triangulation strategies to improve the validity of case studies, using multiple perceptions to clarify meaning and verify the repeatability of an observation (Stake, Citation1994) (Kapitan, Citation2015, p. 111), with some degree of objectivity (Noffke & Somekh, Citation2005, p. 190).

A case study by (Hanevik et al., Citation2013) is an example of a multiple case study methodology aiming to add rigour and minimise biases.

Theory and methodological triangulation are utilised, with theoretical knowledge informing the interactive square analysis of the video recording and the arts-based narrative analysis of the interview with the client. Data gathering and analysis took place after the art therapy sessions and the interview and cross-checked with the clinical supervisor.

The interactive square analysis

The Interactive square concept, developed by (Bragge & Fenner, Citation2009), was used to identify interactive components from video recordings of the sessions that could facilitate communication and emotional regulation. The elements of the interactive square are summarised below in .

Table 2. Interactive square analysis.

Video research methods

The video allowed the therapist to engage in the art-making process promoting joint attention and concentration with the client Isserow (Citation2008), providing a less pressurised environment where an autistic person is free to withdraw and re-engage when they feel like it (Evans & Dubowski, Citation2001).

The video gives the practitioner-researcher an outsider’s view and another frame of reference in addition to the therapist's subjective responses and notes (Bragge & Fenner, Citation2009, p. 20).

Narrative analysis

Narrative inquiry is thus well suited to this study as it explores subjective experience (Bruner, Citation1990) in the shape of a recollected interpersonal account (Guignon, Citation1998), shaped by the sociocultural context. This approach contextualises the material more effectively than thematic analysis (Riessman, Citation1994, p. 2) and gives vulnerable populations a voice (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990).

Arts-Based narrative inquiry

Art therapists enable people to express narratives, process feelings and understand experiences. With expertise in picking up non-verbal cues of communication to help a client interpret and reflect on their thought processes and behaviour (Gilroy, Citation2006; Kapitan, Citation2015).

So the potential of creative art forms as a tool of analysis to understand individual experiences (McNiff, Citation1998) is pertinent to this study as it can be a tangible way for an autistic person with learning disabilities to understand the sessions. While the interview aimed to help an autistic person re-appraise their experiences in a structured way as a tool for emotional regulation.

One model of arts-based narrative analysis is Barbee’s (Citation2002) study, which identifies common themes in images, interviews, and narrative transcripts.

Holistic and categorical content analysis

I have used an adapted form of Lieblich et al. (Citation1998) method of narrative analysis to construct a text from the interview, using the holistic content approach to analyse as a whole and the categorical approach to identify specific components that impacted communication and emotional regulation. This approach, was also used in Collie et al. (Citation2006) study.

With the holistic-content approach, a narrative formed from the interview transcript, with questions looking at how the client was at the beginning and the end, with the themes emerging related to the whole set of the art therapy sessions.

The categorical-content approach highlighted passages in the personal narrative that dealt with the research question. These new data subsets were triangulated with the interactive square video and visual material analysis, drawing on relevant literature to define categories that deal with the impact of art therapy on communication and emotional regulation.

The interview

A semi-structured interview with open-ended questions took place that allowed space for the participant to reflect on their experience. It began with accessible questions about art experiences, the individual sessions, and what was challenging. The artwork was available through the interview as a reference (Springham & Brooker, Citation2013) and session visual aids to help the client recollect and re-appraise their experience, with a staff observer present during the interview.

Ethical considerations

Safeguarding and respecting rights were the priority of this research (Kapitan, Citation2015, p. 155; Kvale, Citation2003). There was clear information to all parties to minimise anxiety (University of Manchester, Citation2007), with care taken to ensure the client did not feel coerced. The art therapy sessions and the interview were in a private, familiar room, with the video recordings stored on a password-protected laptop.

Methodological considerations

In this study, the art therapist combined the roles of practitioner and researcher, specified throughout the research (Myers-Walls, Citation2000), to avoid blurring boundaries. There was the issue of research bias as the client knew the therapist in the service, although this did make the participant feel more comfortable. The video analysis and the interview transcript were cross-checked (Kvale, Citation2003) with the supervisor, while a research journal increased reflexivity (Cresswell, Citation2007).

Results and conclusion

Outlined is a summary of the Interactive Square Analysis from the case study and the arts-based narrative analysis from the interview.

Interaction 1: Introduction to client and general interpersonal relationship

Client  Therapist

Therapist

Stephen is a 27-year-old man diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), learning disability, anxiety, and sensory processing disorder. He is hypersensitive to sensory stimulation, with body awareness (proprioception) and body orientation (vestibular) challenges. He uses cognitive strategies and has a history of seeking-out restraint for proprioceptive input when in a high state of arousal.

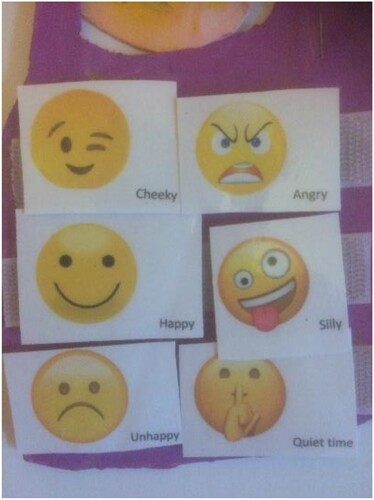

In the sessions, Stephen presented as verbally proficient, enjoying social interaction with an understanding of slapstick humour and verbal puns. Structured elements at the beginning and the end of the sessions included a feelings board of emoticons and friends, family, and places activity to finish.

Stephen found the activity about how emotions can affect your body difficult but enjoyed choosing emoticon images such as ‘silly’ () and ‘cheeky’ ( ) for how he was that day. In session three, he said he was sad earlier but was silly later, and in session 4, wondering why he was angry with some staff and liked the funny staff.

The ‘Friends, Family and Places’ board had different visual sections on the board and he used puns saying that the word ‘section’ not being the same as the word ‘sectioned’, referring to past experiences in in-patient metal health units.

Interaction 2: Client media response and visual expression

Client

In session one, Stephen completed a collage artwork using fine motor skills to apply shapes and tissue paper (). He enjoyed the visual aspect of the bright colours and used rollers, sponges, and brushes to apply paint.

In sessions one, two, and six, Stephen squirted paint and laughed at the ‘squishing’ sound from the paint containers. In the video analysis, he would put paint on his hand and face when the therapist was not looking, as he enjoyed the humorous reaction when the therapist noticed.

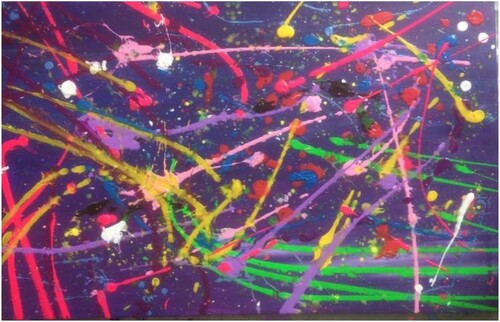

Stephen completed an action painting activity ( ), where he had to drip paint onto a canvas. He enjoyed the bright colours and the unpredictable process of squirting paint straight from the containers onto the canvas.

In sessions three and four, Stephen did not enjoy the touch of plaster and clay but did enjoy the visual experience of mixing plaster with a brush.

Interaction 3: Therapist media response and visual expression

Therapist

In sessions one, two, and five, the therapist modelled to Stephen how to use the roller, sponge, and squeeze paint. The therapist would help to prepare the art materials during the sessions. Sometimes Stephen would need a break, and the therapist would continue for a short time, enabling less pressurised interaction. In sessions four and five, the therapist pre-prepared a canvas mixing blue, pink, and purple colours that the client enjoyed in the previous sessions.

Interaction 4: Comparative view of client and therapist’s artwork

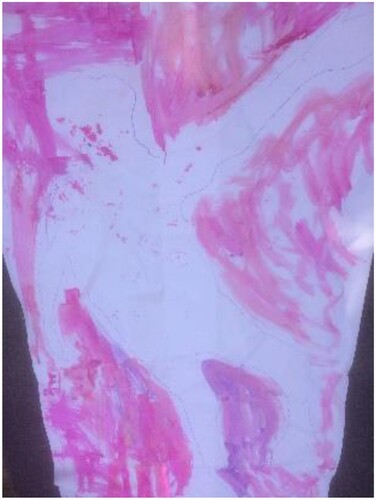

In sessions one and two, Stephen completed a life-size portrait activity () with the art therapist, lying down on a large sheet of paper, with the therapist drawing around him on a large sheet of paper. The body outline was painted, with the client doing the top right and the therapist doing the bottom half.

For the action painting’ Stephen selected bright luminous colours to drip on the canvas while the therapist used more muted colours. In session three, Stephen and the therapist created a textured artwork, and he enjoyed dripping plaster onto the board.

Interaction 5: Art therapy interactions – totality of therapeutic reactions, summation of client’s art therapy process

Through analysing the video footage, Stephen enjoyed working collaboratively on making art, and the process allowed for non-intrusive interactions and exchanges. The qualities of paint provided interest and engagement, and he laughed when the paint splashed onto his shoes and floor.

The personalised emoticons () developed together in the first session and were an effective way of beginning each session and ‘checking in’ with Stephen. Silly and cheeky were positive emotions for him, relating to his love of humour and having fun with the staff.

The friends, family, and places board became a comfortable way to end each session and related to an emotional regulation distraction strategy, where he talked about favourite things and people when he felt anxious. It also stimulated some reflection about why he was calm with some staff and not others.

Holistic-content analysis

Stage 1 foci global summary

The interview took place two weeks after the art therapy sessions. The interview lasted for 20 min, with artwork available as a visual aid. The interview questions invited Stephen to talk about his past experience of art, how he found the sessions, and to look at what he enjoyed and found difficult .

Table 3. Holistic content analysis.

Holistic content analysis themes

‘Messy’ Materials

‘Messy’ Materials

Stephen enjoyed using paint and being ‘messy’ seemed to indicate a positive sensory experience for him. Referring to messy early on in the interview:

00:00.

IV: Ok this is the interview … to tell us about the art therapy session

IE: Yeah but I enjoyed them

00:15.

IV: So why did you enjoy them?

IE: Because they were lovely

00:35.

IE: Andy I like getting messy.

IV: OK

IE Because that is one of the things that I do enjoy

When talking about his favourite art activities at school he again mentioned messy.

01:35.

IV: So what did you like about painting?

IE: I like … getting messy.

‘Foul’ Materials

‘Foul’ Materials

Art materials that were a negative sensory experience, such as plaster and clay, were called ‘foul’, and Stephen enjoyed saying ‘foul’ humorously. He enjoyed mixing plaster, so he likes the visual quality rather than the tactile.

10:39.

IV: Then we had a go at plaster and bandages. What did you think about doing plaster on your hand?

IE: I did not like that at alllllll

IV: Why didn’t you like that bit?

IE: I didn’t like that it was a bit foul

IV: Foul ok, that’s a good word to say

Tone of voice

Tone of voice

In the interview, Stephen used different tones to communicate and emphasise positive and negative feelings about his experiences. So it seems that voice tones are just as important as the actual meaning for Stephen.

Softer tone:

About the sessions: ‘Because they were lovely’ (00:15); ‘Andy I like getting messy’.

High pitched tone:

When asked whether he like doing art, he said ‘yeah’ in a higher pitched tone (02:10); ‘yeahhhh’ when asked whether he enjoyed the ‘friends, family and places board’ (16:42).

He responded in a high pitched ‘squeal’ of delight pointing to ‘silly’ and ‘cheeky’ when asked about the emoticons.

Neutral or low tone:

Not enjoying some art materials on his hands, he emphsised ‘Noooo’ in a tone low (11:10).

‘Not very well’ in low tone when he said he did not understand about the ‘Emotions and the Body’ activity (16:10).

When talking about negative experiences that had happened that day, he used a low voice. ‘Andy I did not mean to do that’ (12:00) or saying ‘because I was a bit anxious’ when we referred to a session that could not be undertaken (12:57).

Difficult things

Difficult things

In the interview, Stephen communicated things he found difficult in the art therapy sessions, such as the abstract concept of the ‘Emotions and the Body’ activity. There were also difficulties in understanding complex words such as ‘concentrate’ (05:32) and the context of words when he answered ‘cheerful’ (02:41).

Worry

Worry

Occasionally, Stephen would need reassurance, referencing an incident where he became angry. With the missed session, he said he was anxious, and it was excellent that he could say before the session.

Anger

Anger

In the interview, Stephen communicated fears about losing control and exhibiting aggression, relating to him having favoured staff who work with him, indicating a need for control in response to his anxiety.

12:00.

IE: Andy this morning I did not mean to do that.

IV: Ok that’s alright, let’s talk about this then.

IV: And you did say you don’t always understand why you feel angry with some staff and happy with others.

IE: mmmmm.

IV: That was a very good thing that you said.

(All nod and agree).

Humour

Humour

Humour in the interview was a way for Stephen to communicate positive emotions and a coping strategy. He relates to clumsy comic characters, as he can struggle with motor skills and everyday tasks. He also liked the references to unexpected things happening in the sessions, such as paint squirting on his shoes and the therapist by mistake.

Categorical-content analysis

The categories highlight different forms of communication, the impact of sensory responses, and the link between anxiety and rumination. The unexpected qualities of art materials and humour were positive factors for emotional regulation .

Table 4. Categorical content analysis.

Communication

Stephen would struggle to understand complex words and appeared to understand more than he appeared, demonstrating social camouflaging (Hull et al., Citation2017).

Processing input can be overwhelming for autistic people with LD. (Davis et al., Citation2011), so when Stephen disengaged and re-engaged from an activity, this allowed him to regulate stimuli. An approach used by art therapists such as Evans and Dubowski (Citation2001) and Bragge and Fenner (Citation2009) and highlights the value of art therapy in enabling less-pressurised interactions (Alter-Muri, Citation2017), with sensory experiences providing the tangible flow to communication (Osborne, Citation2003), facilitating periods of concentration and frustration tolerance. It was interesting during the interview that repetitive communication related to anxiety, while the more positive communication was around sensory experiences and humour.

Sensory

Sensory aspects of the art materials in the art therapy sessions resonated strongly with Stephen during the interview. With positive feelings equated to the word ‘messy’, associated with the visual stimulation of paint, the unexpected drips, and splashes. In contrast to the visual sensory experiences, Stephen described tactile experiences with plaster and clay as ‘foul’, indicating a hypersensitivity to touch. When he did touch paint, it was to generate a humorous reaction.

The large artworks enabled Stephen to move comfortably around them, increasing his confidence about his coordination. The colourful collage activity was visually stimulating and helped Stephen maintain increased concentration with the motor tasks that can be difficult for people with autism (Posar & Visconti, Citation2018).

In the interview, he mentioned an animal art therapy activity, humorously reminding himself that he was like an animal that lived in water, referring to his use of baths as a calming activity giving him proprioceptive input. So sensory art activities can help stimulate communication and provide sensory integration that positively impacts emotional regulation.

Emotional regulation

In the sessions, the emoticons activity gave Stephen a concrete way of describing his feelings (Elkis-Abuhoff, Citation2008) and the friends, family, and places reduced anxiety. During the sessions and the interview, Stephen would worry about controlling himself, reflecting on why he gets angry with some staff and not others.

We have discussed how suppressive defenses, ‘projection’ (Freud, Citation1918), and externalising behaviour is prevalent for autistic people with LD. (Laurent & Rubin, Citation2004; Mazefsky et al., Citation2012; Samson et al., Citation2014) and distressing manifestations of anxiety (Vasa et al., Citation2018). Stephen uses maladaptive emotional regulation strategies such as suppression, which increases his anxiety and arousal.

During supervision, I discussed my countertransference manifesting in the sessions with a worry that I would lose ‘control’, and that he would exhibit aggressive behaviour. For one session, Stephen did not take part, and he confirmed in the interview that he felt too anxious, demonstrating a level of self-awareness when re-appraising (Gross, Citation1998).

Humour

A great deal of the communication in the sessions was about humour, with Stephen appreciating people who have a sense of fun. In the video footage, Stephen enjoyed when unexpected things happened, such as pain squirting onto the therapist and to his shoes.

Stephen enjoys slapstick visual comedy and wordplay that is not reliant on intellectual concepts or social awareness. This preference for incongruent humour with unexpected things, relates to research about ASD and humour. (Kana & Wadsworth, Citation2012; Samson et al., Citation2013; Weiss et al., Citation2013).

Stephen demonstrated wordplay by switching the word ‘section’ to ‘sectioned’ illustrating how he used humour to refer to the experience of mental health hospitals.

Limitations of study

As the sole researcher and therapist, there are inevitable issues with objectivity and reflexivity in the research with the single case study approach, despite attempts to include triangulation methods. The therapist had a pre-existing work relationship with the client which brings inevitable bias, although existing rapport did benefit in helping the client feel comfortable.

Due to the client's presenting needs, there were limitations with the number of sessions conducted, as there were times that the participant struggle with anxiety and behavioural challenges so care was taken to make sure his wellbeing was the priority.

Conclusions

Analysis indicates that art therapy enabled non-intrusive communication for the client, building relationships, as described in the literature (Alter-Muri, Citation2017). The client benefited from a non-pressurised method of attuning where the client can choose to withdraw or engage (Bragge & Fenner, Citation2009; Evans & Dubowski, Citation2001).

There was evidence that art therapy helped Stephen improve his concentration and communication abilities. The collaborative art process helped with attention, and he could regulate his distance from the therapist through art making and ‘sensory’ breaks. With the video analysis providing a third viewpoint, the therapist could be freer to engage in art-making with the client, working on joint attention skills (Isserow, Citation2008).

During the interview, Stephen would communicate and engage more when discussing the art materials and the artworks made, commenting on what sensory experiences he liked and disliked, and this concretised abstract concepts for him (Elkis-Abuhoff, Citation2008) with the sensory, inviting engagement with the outside world (Osborne, 2013).

In the art therapy sessions, Stephen enjoyed the visual properties of paint and the unexpected nature of the ‘messy’ art materials. These sensory experiences could be ‘visceral feelings’ stimulated by art-making, engaging the senses, enabling communication and emotional awareness. According to the Collins dictionary, visceral feelings are ‘"feelings’ that you feel deeply … . not the result of thoughts”’ (Collins Dictionary, Citation2019). I am proposing that his sensory and self-regulatory systems are both ‘visceral’ systems that are difficult to manage.

Visceral sensations and sensory information are processed by somatosensory systems (Dougherty, Citation1997), and these sensory-motor systems develop alongside emotional and relational systems (Elbrecht & Antcliff, Citation2015, p. 211). We have seen that sensory sensitivities for an autistic person can impact the ability to mirror and attune with a caregiver and to develop emotional regulation capabilities.

Stephen would have strong reactions to the materials, as either ‘messy’ (positive) or ‘foul (negative), indicating hyper-activation of sensory input (Malchiodi, Citation2020). He struggled with coordination and interoception, with difficulties with vestibular balance and proprioceptive body awareness. Encountering these different materials helped him to balance his sensory input (Wallace, Citation2015), stimulating less rigid thinking and minimising the sensory dysfunction that can contribute to avoidant behaviours, increased arousal, and aggressive behaviour.

These insights point to the value of a bottom-up therapeutic approach (Elbrecht & Antcliff, Citation2014, p. 22) that involves kinesthetic and motor impulses stimulation which can restore the ability to integrate sensory, emotional, and relational information impaired due to adverse childhood experiences (Elbrecht & Antclif, 2014, Citation2015, p. 219). Research has found that art-making can reduce stress (Kaimal et al., Citation2016) and access those parts of the brain that code trauma (Carr & Hass-Cohen, Citation2008; Perry & Pollard, Citation1997; Schore, Citation2013). Gendlin (Citation1982) and Levine (Citation2010) describes this as the ‘felt sense, a physical experience of getting in touch with your body that can transform trauma, as trauma can remain trapped in the body (Van Der Kolk, Citation1987).

With emotional regulation, the ‘friends and family activity helped to enable the ‘distraction’ strategy (Gruber & Oepen, Citation2018). Whilst, the action painting allowed Stephen to ‘sublimate’ (Kramer, Citation1971) his energies into a productive activity (Mango & R; Richman, Citation1990), suggesting that the artwork could function as the ‘container’ as described by Bion (Citation1961).

During the sessions and in the interview, Stephen reflected on why he was angry with some staff and not others, an example of re-appraisal, a processing system essential for emotional regulation (Gross, Citation1998), stimulated by the sensory art-making, non-invasive approach, and the artwork referenced in the interview. Lobban (Citation2014) tells us that unconscious unprocessed material expressed through image-making, then decoded using cognitive appraisal mechanisms, involves reduced avoidance and increased tolerance of emotions which leads to improved insight (p.41).

These findings demonstrate elements of the art therapy sessions assist with emotional regulation, providing a non-verbal communication method to interact and express oneself and process feelings (Haeyen et al., Citation2018). These strategies are an alternative to avoidance and cognitive suppression, which lead to anxiety and externalising behaviour.

D'Amico and Lalonde (Citation2017, p. 176) point to art therapy allowing autistic individuals to learn information through sensory experiences, addressing feelings of anxiety, depression, and frustration. Incongruent and fluid qualities of art materials can have unexpected effects that surprise, like humour, highlighted in the analysis as a coping strategy for Stephen. So humorous wordplay, interaction, and spontaneous sensory experiences distract from ruminations and serve to decrease anxiety and arousal levels for Stephen. Another tool developed in the sessions was an emotion board using emoticon signs. The humorous aspect of the images was engaging and a concrete representation of abstract concepts.

We know that art and humour can express repressed thoughts and feelings and strengthen the ego (Mango & Richman), equalising relationships and building rapport and social cohesion (Lobban, Citation2014). Stephen uses humour to identify with comedic characters and the unexpected things that can happen in art. So combined with creative expression can help the cognitive processing of emotionally charged memories (Kopytin & Lebedev, Citation2015). He also used humorous wordplay to refer to his experience of being ‘sectioned’ and staying in in-patient mental health services.

So Incongruous humour and expressive spontaneity can release anxiety and dissipate aggression, an excellent emotional regulation strategy for autistic people with learning disabilities like Stephen.

Art Therapy can thus assist with expressing unprocessed material and decoding using cognitive appraisal mechanisms. Autistics hold many memories without having the cognitive skills to re-appraise and move past them. Sensory engagement promotes communication and emotional awareness, reducing the reliance on maladaptive emotional regulation strategies such as suppression and avoidance.

Recommendations for further research

The multiple analysis of the interactive square and the arts-based narrative analysis has provided additional triangulation methods to add depth to the study. As well as the thoughts and feelings of the participant,

Although in a large study, ‘Investigator Triangulation’ where different observers consulted would uncover alternative viewpoints (Kapitan, Citation2015, p. 111; Stake, Citation1995), with a research team checking analysis and conclusions.

The holistic and categorical lens does have some repetition with one participant, although this could be a model to apply to larger sample sizes. Therefore, holistic content analysis could be used for each participant in the study, and categorical analysis could extrapolate categories from the data and provide conclusions that apply to the larger autistic populations. Thematic analysis could be used on collections of interview transcripts to provide a wider lens of analysis.

A research ‘facilitator’ (Noffke & Somekh, Citation2005) would lend another level of objectivity reflexivity to the research Carr and Kemmis (Citation1986), and the cyclical nature of action research could be more coherent.

Investigating the research with individuals across the ASD spectrum including people who are non-verbal and people with Asperger’s syndrome. would be valuable. Including parent insight, interviews participants to take on the roles described in participation-based action art therapy research (Spaniol, Citation2005).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2023.2275927)

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrew Christopher Wright

Andrew C Wright is a trained Art Psychotherapist, UK licensed and registered, who trained at Goldsmiths College, University of London UK in 2002 and he has completed a Masters in Educational research at the University of London in 2019. Andrew has worked in London, Singapore, and Dubai. He is now based in Bournemouth, Dorset, working in private practice, and provides art therapy services to children, adolescents, and adults. He is also an approved private practitioner and clinical supervisor for BAAT.

References

- Alter-Muri,S. (2017) ‘Art education and Art therapy strategies for autism spectrum disorder students.’ Art Education ,70(5):20-25.https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2017.1335536.

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Autism Act . (2009). UK government legislation. National Archives. Retrieved August 20, 2019, from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2009/15/contents/enacted

- Barbee,M. (2002).A visual-narrative approach to understanding transsexual identity. Art Therapy , 19 (2),53–62.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2002.10129339

- Baron-Cohen,S. , Leslie,A. M. & Frith,U. (1985).Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition 21(1),37–46.https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8

- BBC News . (2019). The failings in learning disability services in six charts. Retrieved July 21, 2022, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-48355111

- Bion,W. R. (1961). Experiences in groups .Tavistock Publications.

- Bowlby,J. (1968). Attachment and loss: Vol.1-3 .Basic Books.

- Bragge,A. , & Fenner,P. (2009).The emergence of the ‘interactive square’ as an approach to art therapy with children on the autistic spectrum. International Journal of Art Therapy , 14 (1),17–28.https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830903006323

- Bruner,J. (1990). Acts of meaning .Harvard University Press.

- Cai,R. Y. , Richadale,A. L. , Dissanayake,C. , & Uljarevic,M. (2018).Brief report: Inter-relationship between emotion regulation, intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and depression in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 48 (1),316–325.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3318-7

- Care Quality Commission Interim Report . (2019). CQC calls for action to fix the closed system that leads to people with a learning disability or autism being segregated in hospital. Retrieved August 20, 2019, from https://www.cqc.org.uk/news/releases/cqc-calls-action-fix-closed-system-leads-people-learning-disability-or-autism-being

- Carr,R. , & Hass-Cohen,N. (2008). Art therapy and clinical neuroscience .Jessica Kingsley.

- Carr,W. , & Kemmis,S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research .Falmer Press.

- Case,C. (2000).‘Our lady of the queen’: Journeys around the maternal object. In A. Gilroy , & G. McNeilly (Eds.), The changing shape of Art therapy. New developments in theory and practice (pp. 1555).Jessica Kingsley.

- Case,C. , & Dalley,T. (2003). The handbook of art therapy (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Case-Smith,J. , Weaver,L. L. , & Fristad,M. A. (2015).A systematic review of sensory processing interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism , 19 (2),133–148.https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313517762

- Collie,K. , Bottorff,J. L. , & Long,B. C. (2006).A narrative view of Art therapy and Art making by women with breast cancer. Journal of Health Psychology , 11 (5),761–775.https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105306066632

- Collins Dictionary . (2019). Retrieved July 21. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/visceral

- Connelly,M. , & Clandinin,J. (1990).Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher , 19 (5),2–14.https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002

- Costello,P. M. (2003). Action research .Continuum.

- Creswell,J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Dalley,T. , Rifkind,G. , & Terry,K. (1993). Three voices of Art therapy: Image, client, and therapist .Routledge.

- D'Amico,M. , & Lalonde,C. (2017).The effectiveness of Art therapy for teaching social skills to children with autism spectrum disorder. Art Therapy , 34 (4),176–182.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2017.1384678

- Davis,T. E. , Moree,B. N. , Dempsey,T. , Reuther,E. T. , Fodstad,J. C. , Hess,J. A. , Jenkins,W. S. , & Matson,J. L. (2011).The relationship between autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: The moderating effect of communication. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders , 5 (1),324–329.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.04.015

- Dougherty,P. (1997). Chapter 2: Somatosensory systems. Section 2 sensory systems. Neuroscience online, the open-access neuroscience electronic textbook. Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy, McGovern Medical School at UTHealth. Retrieved August 19, 2019, from https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/s2/chapter02.html

- Durani,H. (2014).Facilitating attachment in children with autism through Art therapy: A case study. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration , 24 (2),99–108.https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036974

- Edwards,D. (1999).The role of the case study in Art therapy research. Inscape , 4 (1),2–9. doi:10.1080/17454839908413068.

- Elbrecht,C. , & Antcliff,L. (2015).Being in touch: Healing developmental and attachment trauma at the clay field. Children Australia , 40 (3),209–220.https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2015.30

- Elbrecht,C. , & Antcliff,L. R. (2014).Being touched through touch. Trauma treatment through haptic perception at the clay field: A sensorimotor art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy , 19 (1),19–30.https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2014.880932

- Elkis-Abuhoff,D. L. (2008).Art therapy applied to an adolescent with Asperger’s syndrome. The Arts in Psychotherapy , 35 (4),262–270.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2008.06.007

- Emery,M. J. (2004).Art therapy as an intervention for autism. Art Therapy , 21 (3),143–147.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2004.10129500

- Evans,K. (1998).Shaping experience and sharing meaning- Art therapy for children with autism. Inscape , 3 (1),17–25.https://doi.org/10.1080/17454839808413055

- Evans,K. , & Dubowski,J. (2001). Art therapy with children on the autistic spectrum – beyond words .Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Fenning,R. M. , Baker,J. K. , & Moffitt,J. (2018).Intrinsic and extrinsic predictors of emotion regulation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 48 (11),3858–3870.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3647-1

- Freud,S. (1918). From the history of an infantile neurosis (Vol 17) .Hogarth Press.

- Furneaux-Blick,S. (2019).Painting together: How joint activity reinforces the therapeutic relationship with a young person with learning disabilities. International Journal of Art Therapy , 24 ( 4 ),169–180.http://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1677732

- Gazeas,M. (2012).Current findings on Art therapy and individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal , 25 (1),15–22.https://doi.org/10.1080/08322473.2012.11415558

- Gendlin,E. T. (1982). Focusing .New York: Bantam.

- Gilroy,A. (2006). Art therapy, research and evidence-based practices .Sage Publishers.

- Goldsmith,S. F. , & Kelley,E. (2018).Associations between emotion regulation and social impairment in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 48 (6),2164–2173.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3483-3

- Gross,J. J. (1998).The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology ,2 (3),,271–299. First Published September 1, 1998 Research Article. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271.

- Gruber,H. , & Oepen,R. (2018).Emotion regulation strategies and effects in art-making: A narrative synthesis. The Arts in Psychotherapy , 59 ,65–74.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.12.006

- Guignon,C. (1998).Narrative explanation in psychotherapy. The American Behavioural Scientist , 41 (4),558–577.. ProQuest pg. 558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764298041004007

- Gupta,S. , Caskey,A. , Soares,N. , & Augustyn,M. (2018).Autism spectrum disorder and mental health comorbidity leading to prolonged inpatient admission. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics , 39 (6),523–525.https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000599

- Hackett,S. , Ashby,L. , Parker,K. , Goody,S. , & Power,N. (2017).UK art therapy practice-based guidelines for children and adults with learning disabilities. International Journal of Art Therapy , 22 (1),1–11. doi:10.1080/17454832.2017.1319870.

- Haeyen,S. , Van Hooren,S. , Van Der Veld,W. M. , & Hutschemaekers,G. (2018).Measuring the contribution of Art therapy in multidisciplinary treatment of personality disorders: The construction of the self-expression and emotion regulation in Art therapy scale (SERATS). Personality and Mental Health , 12 (1),3–14.https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1379

- Hanevik,H. , Hestad,K. , Lien,L. , Teglbjaerg,H. S. , & Danbolt,L. J. (2013).Expressive art therapy for psychosis: A multiple case study. The Arts in Psychotherapy , 40 (3),312–321.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2013.05.011

- Haque,S. , & Haque,M. (2015).Art therapy and autism. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research , 8 (6).https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ajpcr/article/view/8242/3387.

- Hull,L. , Petrides,K. V. , Allison,C. , Smith,P. , Baron-Cohen,S. , Lai,M.-C. , & Mandy,W. (2017).“Putting on My best normal”: social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 47 (8),2519–2534.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5

- Irvine,M. , & Beail,N. (2016).Chapter 1: Identifying and meeting the emotional and mental health needs of 11 people who have intellectual disabilities through psychological therapies. In N. Beail (Ed.), Psychological therapies and people who have intellectual disabilities (pp. 11–19).Leicester: British Psychological Society.

- Isserow,J. (2008).Looking together: Joint attention in Art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy , 13 (1),34–42.https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830802002894

- Kagin,S. , & Lusebrink,V. (1978).The expressive therapies continuum. Art Psychotherapy , 5 (4),171–180.https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-9092(78)90031-5

- Kaimal,G. , Ray,K. , & Muniz,J. (2016).Reduction of cortisol levels and participants’ responses following Art making. Art Therapy , 33 (2),74–80.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1166832

- Kana,R. , & Wadsworth,H. M. (2012). “The archeologist's career ended in ruins”: Hemispheric differences in pun comprehension in autism. Conference Paper · May 2009. Conference: International Meeting for Autism Research 2009. Retrieved August 20, 2019, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268141471_When_the_Archeologist's_Career_Ended_in_Ruins_An_fMRI_Study_of_Pun_Comprehension_in_Autism

- Kapitan,L. (2015). Introduction to Art therapy research (1st ed.).Routledge.

- Kientz,M. A. , & Dunn,W. (1997).A comparison of the performance of children with and without autism on the sensory profile. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 51 (7),530–537.https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.51.7.530

- Kopytin,A. , & Lebedev,A. (2015).Therapeutic functions of humour in group art therapy with war veterans. International Journal of Art Therapy , 20 (2),40–53.https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2014.1000348

- Kramer,E. (1971). Art as therapy with children .Schocken Books.

- Kvale,S. (2003).The psychoanalytic interview as inspiration for qualitative research. In P. M. Camie , J. E. Rhodes , & L. Yardley (Eds.), Quantitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 275–297).American Psychological Association.

- Laurent,A. C. , & Rubin,E. (2004).Challenges in emotional regulation in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Topics in Language Disorders , 24 (4),286–297.https://doi.org/10.1097/00011363-200410000-00006

- Levine,P. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness .Berkley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

- Lieblich,A. , Tuval-Mashiach,R. , & Zilber,T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation .Sage Publications, Inc.

- Liebmann,M. (2008). Art therapy and anger .Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Lobban,J. (2014).The invisible wound: Veterans’ art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy , 19 (1),3–18.https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2012.725547

- Malchiodi,C. (1998).Embracing our mission, art therapy. Journal of the American Art Therapy Association , 15 (2),82–83.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.1989.10758716.

- Malchiodi,C. (2003). Handbook of Art therapy .The Guildford Press.

- Malchiodi,C. (2020). Trauma and expressive arts therapy: Brain, body, and imagination in the healing process .Guilford Publications.

- Malhotra,B. (2019).Art therapy with puppet making to promote emotional empathy for an adolescent With autism. Art Therapy , 36 (4),183–191.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2019.1645500

- Mango,C. R. , & Richman,J. (1990).Humour and art therapy. American Journal of Art Therapy , 28 (4),111–114.

- Martin,N. (2009a). Art as an early intervention tool for children with autism .Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Martin,N. (2009b).Art therapy and autism: Overview and recommendations. Art Therapy , 26 (4),,187–190.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2009.10129616

- Mazefsky,C. , Pelphrey,K. , & Dahl,R. (2012).The need for a broader approach to emotion regulation research in autism. Child Development Perspectives , 6 (1),92–97. Published online 2012 Jan 12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00229.x

- Mazefsky, C. P., Herrington, J., Siegal, M., Scarpa, A., Maddox, B. B., Scahill, L., & White, S . (2013).The Role of Emotion Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder RH: Emotion Regulation in ASD. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 52 (7),679–688.

- McGuire,K. , Erickson,C. , Gabriels,R. L. , Kaplan,D. , Mazefsky,C. , McGonigle,J. , Meservy,J. , Pedapati,E. , Pierri,J. , Wink,L. , & Segal,M. (2015).Psychiatric hospitalization of children with autism or intellectual disability: Consensus statements on best practices. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 54 (12),969–971.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.08.017.

- McLeod,J. (2011). Qualitative research in counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.).Sage.

- McNiff,S. (1998). Art based research .Jessica Kingsley.

- Milton,D. , & Bracher,M. (2013).Autistics speak but are they heard? Medical Sociology Online , 7 (2),61–69.

- Mundy,P. (1995).Joint attention and social-emotional approach behavior in children with autism. Development and Psychopathology , 7 (1),63–82.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400006349

- Myers-Walls,J. A. (2000).An odd couple with promise: Researchers and practitioners in evaluation settings. Family Relations , 49 (3),341–347.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00341

- Nadeau, J., Sulkowski, M. L., Ung, D., Wood, J. J., Lewin, A. B., Murphy, T. K., May, J. E., & Storch, E. A. . (2013).Treatment of comorbid anxiety and autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychiatry (London) , 1 (6),567–578.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3809000/.

- Naff,K. (2014).A framework for treating cumulative trauma With Art therapy. Art Therapy , 31 (2),79–86.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2014.903824

- National Autistic Society Article . (2022). Number of autistic people in mental health hospitals: Latest data. Published on 17 February 2022. Retrieved Augsut 10. 2022, from https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we-do/news/autistic-people-in-mental-health-hospitals

- Nisbet,J. , & Watt,J. (1984).Case study. In J. Bell , A. Fox , J. Goodey , & S. Goulding (Eds.), Conducting small scale investigation in educational management (pp. 79–92).Harper and Row.

- Noffke,S. , & Somekh,B. (2005).Action research. In B. Somekh , & C. Lewin (Eds.), Research methods in the social sciences (pp. 89–95).Sage.

- Nolte,T. , Guiney,J. , Fonagy,P. , Mayes,L. C. , & Luyeten,P. (2011).Interpersonal stress regulation and the development of anxiety disorders: An attachment-based developmental framework. Frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience , 5 ,55.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00055.

- Osborne,J. (2003).Art and the child with autism: Therapy or education?. Early Child Development and Care , 173 ( 4 ),411–423.http://doi.org/10.1080/0300443032000079096

- Owen,J. P. , Marco,E. J. , Desai,S. , Fourie,E. , Harris,J. , Hill,S. S. , Arnett,A. B. , & Mukherjee,P. (2013).Abnormal white matter microstructure in children with sensory processing disorders. NeuroImage: Clinical , 2 ,844–853.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2013.06.009

- Perry,B. D. , & Pollard,D. (1997). Altered brain development following global neglect in early childhood. Society For neuroscience: Proceedings from annual meeting, New Orleans.

- Posar,A. , & Visconti,P. (2018).Sensory abnormalities in children with autism spectrum disorder. Jornal de Pediatria , 94 (4),342–350.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2017.08.008

- Pounsett,H. , Parker,K. , Hawtin,A. , & Collins,S. (2006).Examination of the changes that take place during an art therapy intervention. International Journal of Art Therapy , 11 ( 2 ),79–101.http://doi.org/10.1080/17454830600980325

- Rees,M. (1995).Making sense of making space: Researching Art therapy with people who have severe learning difficulties. In A. Gilroy , & C. Lee (Eds.), Art and music: Therapy and research .Routledge.

- Regev,D. , Dagol,E. , & Snir,S. (2013).Art therapy for treating children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD): The unique contribution of Art materials.’ faculty of social welfare & health sciences. Graduate school of creative arts therapies . Academic Journal of Creative Art Therapies , 3 (2),251–260.https://ajcat.haifa.ac.il/images/Dec%202013/Regev%20Snir%20-Eng%20article.pdf.

- Richardson,J. F. (2015).Chapter 30: Art therapy on the autism spectrum: Engaging the mind, brain, and senses. In D. E. Gussak , & M. L. Rosal (Eds.), The wiley handbook of Art therapy (pp. 306–316).John Wiley and Sons Publishing.

- Rieffe,C. , Oosterveld,P. , Miers,A. C. ,Terwogt, M. M., & Ly, V. (2008).Emotion awareness and internalising symptoms in children and adolescents: The emotion awareness questionnaire revised. Personality and Individual Differences , 45 (8),756–761.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.08.001

- Riessman,C. K. (1994). Narrative analysis .Sage.

- Samson,A. C. , Huber,O. , & Ruch,W. (2013).Seven decades after Hans Asperger’s observations: A comprehensive study of humor in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Humor , 26 (3),441–460. doi:10.1515/humor-2013-0026

- Samson,A. C. , Phillips,J. M. , Parker,K. J. , Shah,S. , Gross,J. J. , & Hardan,A. Y. (2014).Emotion dysregulation and the core features of autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 44 (7),1766–1772.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-2022-5

- Sarris,M. (2017). Anxiety’s toll on people with autism. Interactive autism network at kennedy krieger institute. Date Last Revised: January 3, 2018. Date Published: December 26, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2022, from https://iancommunity.org/anxietys-toll-people-autism

- Sarris,M. (2018). What anxiety treatments work for people with autism? Interactive autism network at kennedy krieger institute. Date Published: January 3, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2022, from https://iancommunity.org/what-anxiety-treatments-work-people-autism

- Schaverien,J. (2000).The triangular relationship and the aesthetic countertransference in analytical Art psychotherapy. In A. Gilroy , & G. McNeilley (Eds.), The changing shape of Art therapy (pp. 5583).Jessica Kingsley.

- Schore,A. N. (2013).Relational trauma, brain development, and dissociation. In J. D. Ford , & C. A. Courtois (Eds.), Treating complex traumatic stress disorders in children and adolescents: Scientific foundations and therapeutic models (pp. 3–23).The Guilford Press.

- Schweizer,C. , Knorth,E. J. , & Marinus,M. (2014).Art therapy with children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of clinical case descriptions on ‘what works.’. The Arts in Psychotherapy , 41 (5),577–593.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.009

- Schweizer,C. , Spreen,M. , & Knorth,E. J. (2017).Exploring what works in Art therapy with children with autism: Tacit knowledge of Art therapists. Art Therapy , 34 (4),183–191.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2017.1392760

- Spaniol,S. (2005)."Learned hopefulness": An arts-based approach to participatory action research. Art Therapy , 22 (2),86–91.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129446

- Spence,S. H. (2003).Social skills training with children and young people: Theory, evidence and practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health , 8 (2),84–96.https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-3588.00051

- Springham,N. , & Brooker,J. (2013).Reflect interview using audio-image recording: Development and feasibility study. International Journal of Art Therapy , 18 (2),54–66.https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2013.791997

- Springham,N. , Findlay,D. , Woods,A. , & Harris,J. (2012).How can art therapy contribute to mentalization in borderline personality disorder? International Journal of Art Therapy , 17 (3),115–129.https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2012.734835

- Stake,R. E. (1995). The Art of case study research .Sage Publications.

- Thye,M. D. , Bednarz,H. M. , Herringshaw,A. J. , Sartin,E. B. , & Kana,S. R. (2018).The impact of atypical sensory processing on social impairments in autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience , 29 ,151–167.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2017.04.010

- University of Manchester . (2007). Guidelines for conducting research with the autistic community. Autism Manchester. Published version: October 2017. Accessed August 19, 2019, from http://www.autism.manchester.ac.uk/research/projects/research-guidelines/

- Van Der Kolk,B. (1987). Psychological Trauma .Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Van Lith,T. , Stallings,W. J. , & Harris,C. E. (2017).Discovering good practice for art therapy with children who have autism spectrum disorder: The results of a small scale survey. The Arts in Psychotherapy , 54 ,78–84.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.01.002

- Vasa,R. A. , Keefer,A. , Reaven,J. , South,M. , & White,S. W. (2018).Priorities for advancing research on youth with autism spectrum disorder and Co-occurring anxiety. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders ,48(3),925–934.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3320-0

- Wallace,K. O. (2015).Art therapy and autism. In There is no need to talk about this. Poetic inquiry from the art therapy studio series: Transgressions: Cultural studies and education (vol. 108, pp. 37–42).Brill Print Publication.

- Weiss,E. M. , Gschaidbauer,B. C. , Samson,A. C. , Steinbacker,K. , Fink,A. , & Papousek,I. (2013).From Ice Age to Madagascar: Appreciation of slapstick humor in children with Asperger’s syndrome. Humor , 26 (3),423–440.https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2013-0029

- Weiss,J. , Thomson,K. , & Chan,L. (2014).A systematic literature review of emotion regulation measurement in individuals With autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research , 7 (6),629–648.https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1426

- Weiss,J. , Thomson,K. , Riosa,P. B. , Albaum,C. , Chan,V. , Maugham,A. , Tablon,P. , & Black,K. (2018).A randomized waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy to improve emotion regulation in children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 59 (11),1180–1191.https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12915

- Wing,L. , & Gould,J. (1979).Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children: Epidemiology and classification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 9 (1),11–29.https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01531288.

- Winnicott,D. W. (1972). Playing and reality .Routledge.

- Wood,C. (1990).The triangular relationship: The beginnings and endings of Art therapy. Inscape: Journal of Art Therapy , Winter ,7–13.

- Yin,R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd ed.).Sage.