ABSTRACT

Background:

The first 1000 days (conception to 2 years postnatal) are crucial for parent and infant health. Visual art-based interventions are used to promote positive parental mental health, but currently, there are no comprehensive insights into how these interventions can support new parents during this critical perinatal period.

Aims:

To synthesise research on visual art-based interventions designed to promote parents’ mental well-being during the first 1000 days to understand if and how these interventions made a difference and to identify any barriers or facilitators to parents’ engagement.

Method:

A keyword search of five databases (CINAHL, Embase, Medline, PsychInfo and Scopus), searches via Google Scholar and backward and forward chaining were undertaken. Quality appraisal was conducted using design appropriate tools, and a narrative thematic approach was used.

Results:

4417 hits were identified, and 10 studies met eligibility criteria and were included. Interventions were classified as art therapy (n = 8) or creative arts (n = 2), and overall, a lack of robust evidence was highlighted. Six themes were constructed that describe the psychosocial impacts and experiences of the interventions and relational and contextual factors that influenced parents’ engagement. While both types of interventions had benefits, art therapy had the most profound impacts. Challenges regarding sustainability of impacts and facilitator skills were noted for creative arts, rather than art therapy interventions.

Conclusion:

While art therapy interventions promote positive parental mental health and well-being, high-quality evidence is needed.

Implications for future research:

More robust evaluation designs to identify mechanisms of effectiveness in art therapy interventions are needed.

Plain-language summary

In this study, we aimed to combine and summarise all available published research on visual art-based interventions (such as art therapy and creative arts) that had been designed to improve parents’ mental health and well-being during pregnancy or up to two years after birth. We wanted to find out if and how these interventions made a difference to parents, and what helped or did not help parents to take part. We found 10 relevant studies that involved different art-based interventions – eight were art therapy interventions delivered by a trained art therapist and two interventions were creative arts interventions delivered by other professionals (e.g. specialist health visitor, arts officer).

Most studies (80%) were undertaken in high-income countries, used different study designs, and often only included a small number of participants. Overall, there were benefits of both types of interventions for parents, but the most lasting and significant impacts were for art therapy. Parents in arts therapy studies felt the intervention had helped to increase awareness of their mental health issues, improved their confidence and self-esteem, helped them to build positive parent-baby connections and encouraged them to seek out further help.

Group-based art therapy also helped parents to form connections and friendships and to reduce social isolation and loneliness. Some factors that influenced parent participation were positive relationships with the therapist and being provided with clear information. Barriers to engagement were generally reported in creative arts, rather than art therapy interventions. Overall, the evidence suggests that art therapy could be an important intervention for parents who have poor mental health. However, more research is needed.

Introduction

The first 1000 days, defined as from conception to 2 years after birth, can be a time of celebration with a new arrival into the family, however, for some parents, it marks a period of challenge, uncertainty, and deterioration in mental health (Howard et al., Citation2014). This period involves physical and psychological challenges and adjustments, as well as culturally and socially imposed pressures and expectations about becoming a parent (Crane et al., Citation2021). All these events can impact the well-being of a new parent, and can have complications long after the perinatal period ends.

Perinatal mental illness affects around 10–20% of women (Bauer et al., Citation2014) and 4–25% of men (Stadtlander, Citation2015). Research suggests that about half of all cases of poor perinatal mental health go undetected (Hogan et al., Citation2017), with these rates suggested to be even higher amongst marginalised parents (such as those who have a mental illness or minoritised ethnic parents) due to a lack of access to health care (McNab et al., Citation2022). While the early postnatal period is crucial to build foundations for optimum infant health (Evans, Citation2019), untreated perinatal mental health can have adverse effects on both parent and child. This is due to physical health issues including poor nutrition, smoking and substance misuse, and mental health issues such as insecure maternal/new-born attachment, child temperament and psychopathology (Bhat et al., Citation2017; Demontigny et al., Citation2013; Ramchandani et al., Citation2008). It has been identified that poor perinatal mental health costs approximately 8.1 billion a year, with most costs assigned to impacts on the child (Bauer et al., Citation2014).

In the UK there is a commitment to develop specialist perinatal mental health services to ensure that all women and birthing people can access appropriate care (NHS, Citation2019) with all NHS trusts expected to have a perinatal mental health service in place by 2023/2024. While these services are likely to offer more traditional therapies such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (NICE, Citation2011), over the last few decades research has been undertaken into alternate interventions. Art therapy is one alternate form of intervention which emerged in the middle of the nineteenth century. The British Art Therapy Association (BAAT.org, Citation2022) defines art therapy as ‘a psychological therapy delivered by trained art therapists/art psychotherapists to help anyone whose life has been affected by adverse experiences, illness or disability by supporting their social, emotional and mental health needs’. Case and Dalley (Citation2006) describe art therapy as a therapeutic relationship that uses drawings and paintings as methods to express feelings and emotions and to promote psychological well-being. Furthermore, while other creative art-based interventions use similar materials (e.g. painting, drawing, sculpture) to promote mental well-being, these interventions are led by artists or others who have not received psychological training (Anolak, Citation2022).

Art therapy and creative art-based interventions have been used within a perinatal population (Armstrong & Howatson, Citation2015; Arroyo & Fowler, Citation2013; Hosea, Citation2006; Swan-foster, Citation1989; White et al., Citation2010), however, to date there are no comprehensive insights into parents’ experiences or impacts of these approaches within the first 1000 days. Previous reviews in this area have focused on art therapy within the parent-infant dyad, thereby targeting older children (Armstrong & Ross, Citation2020) or art therapy during pregnancy (Crane et al., Citation2021), that fails to consider how these interventions can support the parenting transition and early parenthood. Hogan and colleagues also published a brief literature review of art therapy in antenatal and postnatal care (Hogan et al., Citation2017), with unstructured approaches being in danger of missing key research. Here we adopted a systematic and focused approach to combine all the published research of visual art-based interventions that were designed to improve parental mental health and well-being during the first 1000 days. We aimed to understand if and how these interventions made a difference and what factors could influence parents’ engagement. An integrative review approach was adopted as it allows for the combination of different methodologies to create a broader understanding of the focus of interest (Cronin & George, Citation2020; Oermann & Knafl, Citation2021; Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005).

Methods

Aims

This integrative review aimed to synthesise research on visual art-based interventions designed to promote parents’ mental wellbeing during the first 1000 days to understand if and how these interventions made a difference, and to identify any barriers or facilitators to parents’ engagement.

Design

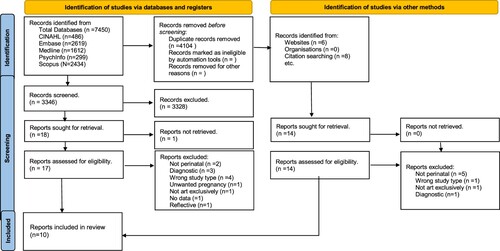

An integrative review using the approach developed by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Citation2021). The protocol for the systematic review was registered on Prospero and is available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID = CRD42022332963.

Search strategy and study selection

The search terms were developed using the PEO (P – population; E – exposure; O – outcomes) framework and involved identifying terms used in similar reviews (i.e. Armstrong & Ross, Citation2020; Crane et al., Citation2021) and support from an expert librarian. Following initial scoping searches to test the efficacy of the search terms, searches were undertaken in five databases (CINAHL, Embase, Medline, PsychInfo and Scopus). Search terms are detailed in .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Relevant articles obtained through the database searches were transferred to Endnote, duplicates removed and then uploaded to Rayyan for title and abstract screening using inclusion and exclusion criteria (see ).

Title and abstracts of identified articles were screened by one author, with a sample of 20% independently screened by at least one other member of the review team. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Inter-rater reliability for title and abstract screening was 99%. Following title and abstract screening, full text review of all potentially suitable articles was undertaken by three members of the review team and interrater reliability was 100%.

A data extraction sheet was developed and used to record information about the included studies and findings directly related to the review question. This information included country, study aim, participant demographics, sample size, intervention details and findings in relation to mental health and well-being and facilitators and barriers. Two authors were involved in data extraction and interrater reliability was recorded at 100%.

Data evaluation

Data evaluation (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005) was undertaken using the Mixed Method Assessment Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Citation2018) and Walsh and Downe’s (Citation2006) quality assessment grading criteria, with studies graded on a scale of A-D (see ). All studies were graded by two authors independently and interrater reliability was recorded at 100%.

Table 2. Quality assessment grading criteria.

Data analysis

An inductive narrative analysis approach was used (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005), with all quantitative data reported narratively. All the extracted data (quantitative and qualitative) was uploaded into excel and organised into codes, and then synthesised into themes and sub-themes that represented the whole data set. Data analysis was undertaken by two authors with all final themes reviewed and agreed by all authors.

Results

The results of the systematic search and screening process are displayed in a PRISMA flow chart (see ). A total of 7450 articles were initially identified from database searches, 6 articles were identified from Google Scholar and 8 via forward and backward chaining. After removal of duplicates, 4117 were retained, 31 remained for full-text review, and overall, 10 articles met the eligibility criteria and were included. Two of the included papers report data from the same study (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018, Citation2020).

Study characteristics

Descriptive information and the quality appraisal of all included studies are presented in . Four studies were undertaken in the United Kingdom, two in USA, two in Sweden and two in Iran. Eight of the studies were undertaken in high-income countries, and two in upper middle income. Four studies targeted pregnant women (Jalambadani et al., Citation2019; Swan-foster, Citation1989; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018, Citation2020), four focused on mothers of children under two (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Perry et al., Citation2008; Ponteri, Citation2001), and two studies were undertaken with parents whose infant was admitted to a neonatal unit (Jouybari et al., Citation2018; White et al., Citation2010). More than half the studies (n = 7) were graded as having few flaws unlikely to affect quality, with the rest (n = 3) being graded as poor quality (either C or D).

Table 3. Descriptive summary of studies.

A summary of the interventions and findings are presented in . Overall, the approaches were heterogeneous in terms of activities, length, and context. Eight studies examined the impact or experiences of art therapy delivered by a trained art therapist (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Jalambadani et al., Citation2019; Jouybari et al., Citation2018; Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Ponteri, Citation2001; Swan-foster, Citation1989; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018, Citation2020), and the remaining two studies used creative arts facilitated by different individuals (e.g. specialist health visitors and an arts officer, or professional artists) (Perry et al., Citation2008; White et al., Citation2010). For the purposes of this paper and to help consider any differences between these interventions, studies have been classified as art therapy or creative arts (see ).

In terms of the focus of the studies, one used art therapy as part of a perinatal outpatient facility (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021). Another examined mindfulness-based art therapy with pregnant women (Jalambadani et al., Citation2019). Moriarty et al. (Citation2022) and Ponteri (Citation2001) art therapy studies were similar in terms of targeting mothers with depression. Swan-foster (Citation1989) examined how art therapy can provide pregnant women with a deeper sense of self during pregnancy through the creation of self-portraits. Whereas another brief creative arts intervention was developed through collaborative work between specialist health visitors and an arts health officer (Perry et al., Citation2008). Wahlbeck et al.’s randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Citation2020) and qualitative follow-up study (Citation2018) explored the impact and experience of an art therapy intervention designed to reduce fear of childbirth; all women who took part in this intervention also received midwife-led counselling. Jouybari et al. (Citation2018) three-arm RCT explored the impact of narrative writing or art therapy on maternal stress in the neonatal intensive care unit. The final study engaged parents in a neonatal unit in a visual arts programme (White et al., Citation2010).

Thematic analysis

Six themes emerged. The first five concern the psychosocial impacts and experiences of the interventions in terms of how they facilitated self-awareness, positivity and healing, the maternal bond, self-development and wider opportunities and connections. The final theme describes how certain strategies facilitated engagement.

Facilitating self-awareness

In four of the art therapy studies (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Swan-foster, Citation1989; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018) women considered how the time and space to engage in visual art-based activities as well as the images they produced had helped them to identify and become more fully aware of their mental health issues. In Bruce and Hackett’s (Citation2021) UK-based study women participated in an art therapy programme as part of a perinatal parent-infant mental health outpatient facility. Three-quarters of the women who participated in the evaluation felt the intervention had increased their self-understanding and facilitated clarity about their emotions and thoughts; one woman described how the art she produced had enabled her to see her ‘life as a museum’ (p. 118.). A further woman in Wahlbeck et al.’s (Citation2018) art therapy study reported:

It helped me to visualize much more clearly the things which I did not know how to put into words or really express what it was that I felt (p. 303)

Facilitating positivity and healing

In three of the included art therapy studies (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Swan-foster, Citation1989; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018;), women provided positive feedback, such as finding it ‘enjoyable’, ‘worthwhile’ and ‘cheered me up’. The creative arts study led by professional artists was reported to have provided an important means of distraction for parents of infants admitted on the neonatal unit, which helped to make the experience ‘more bearable’ (White et al., Citation2010). Other women referred to how the art therapy sessions were relaxing (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021), enabled them to express their feelings (Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018) and alleviated anxiety and stress (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Jalambadani et al., Citation2019; Swan-foster, Citation1989; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018; White et al., Citation2010).

In the RCT by Jouybari et al. (Citation2018) that compared narrative writing and art therapy, the intervention was not found to make a significant difference to maternal stress. Whereas in the Bruce and Hackett (Citation2021) art therapy study, there were noted variations in mood, whereby positive moods fluctuated across the six sessions. Mixed emotions were also reflected in the RCT and qualitative follow-up art therapy study by Wahlbeck et al. (Citation2018, Citation2020). The RCT (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2020) found that all women who took part in the trial had reduced fear of birth scores, but there were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups. In the qualitative follow-up study, women spoke of experiencing feelings of happiness and sadness during the art sessions (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). Women reflected on how the images and colours helped them to gain access to difficult emotions, which was distressing, but in turn, catalysed a healing process that continued between the sessions. One woman reflected:

Then it just came and it was so fantastic to let these emotions come up in the image – that it’s possible!! It made it easier to handle the fear and anxiety. (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018, p. 303)

Facilitating the parental bond

Participants in four of the art therapy studies (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Ponteri, Citation2001; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018) felt that the intervention had impacted on their feelings and relationships with their infant. For example, women in Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) study felt that the sessions had supported them in developing a positive relationship with their baby, and women in Wahlbeck et al.’s (Citation2018) study spoke of how art therapy had helped them to visualise and bond with their unborn child:

When I went home/after the art therapy session/I still had this feeling and a very clear picture of how I wished it would be when he was put on my chest. And I thought I got it down on paper and when he came, I recognized the emotions and then thought of art therapy. (p. 304)

They do a great job at bringing you closer to your baby by getting you to forget about the surroundings you’re in and concentrate on your baby and detail of your baby. (White et al., Citation2010, p. 168)

Facilitating self-development

Across most of the art therapy studies, parents reflected on how the interventions had led to self-development such as being able to adapt to their mental health issues and ‘move on’ (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018, p. 302) and to realise their own inner strength and determination (Ponteri, Citation2001). One of the statements rated most highly by participants in Pontieri’s (Citation2001) study was ‘the group helped me see my strengths as a person and as a mother’; for one led this led her to realise that it was OK for her not to be such a perfectionist:

Kids are messy, and I really need to let that part of myself go, because I don’t have to be perfect and neat and tidy all the time (p. 155)

I was worried not being able to get out of bed. But actually, it proved to myself that I could do that so that was quite good as well. (p. 11)

I saw that this is ME – in a way. It was a mammoth – gigantic, earthbound, and self-confident. I’m quite proud of that. I could almost consider framing it – actually. (p. 303)

It definitely helped with self-esteem because I felt I was amongst other people who sort of like you know were in the same boat as I was where they were unhappy with the situation, they found themselves in. (Perry et al., Citation2008, p. 41)

Facilitating wider connections and opportunities

Parents from five art therapy studies (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Jalambadani et al., Citation2019; Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Ponteri, Citation2001; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018) and the two creative arts interventions (Perry et al., Citation2008; White et al., Citation2010) considered their involvement to have facilitated connections with themselves, others in the group, and their partners. For instance, in Wahlbeck et al.’s (Citation2018) study, women described how art therapy had stimulated an inner therapeutic communication. Whereas in Swan-Foster’s study (Citation1989) the ‘intense imagery’ created by the women was perceived to have enabled them to create ‘a new form outside of herself’ (p. 291).

Three studies also reported benefits of group-based interventions where mothers were able to share insights and form relationships with others who had similar experiences (Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Ponteri, Citation2001; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). Women in Wahlbeck et al.’s (Citation2018) art therapy study spoke of the value of talking openly about their fears and how this was mirrored in other experiences. Whereas mothers in Ponteri’s (Citation2001) art therapy study reported that learning from others with similar concerns was the most enjoyable part of the intervention; over half of the group felt they had been able to empower others and in turn themselves through sharing their insights and experiences. In Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy study, both women who attended the sessions described a ‘strong’ relationship outside of the sessions, and that despite having ‘different illness […] we could relate to each other in that way and be a bit of a support for each other' (p. 13).

From a counter perspective, some challenges of group support were also highlighted. Mothers in Perry et al.’s creative arts study (Citation2008) spoke of difficulties when their experiences did not resonate with others:

Some people were talking about hobbies, but I sort of struggled to find things – I realised life was passing me by and I felt quite down about myself that week. (p. 41)

There was also evidence of art therapy impacting wider relationships. In Jalambadani et al.’s (Citation2019) mindfulness-based art therapy intervention, participants’ scores at the post-intervention stage revealed significant positive differences in their interpersonal relationships. Women in Wahlbeck et al.’s study (Citation2018) also described how art therapy had helped them in their relationships with their partners, with one reporting ‘It also made it easier to talk to my husband. Before it was difficult to put it into words’ (p. 303).

Some of the studies also highlighted how parents’ involvement in the intervention had stimulated access to wider opportunities for support. For example, in some of the art therapy studies parents reflected on how their involvement in the intervention had encouraged them to seek out further support (Perry et al., Citation2008; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). In Perry et al.’s creative arts study, this related to accessing local groups:

I've been able to go to lots of other groups since then. I go to Sure Start stuff nearly every day now. I don’t think I would have gone to any of that if Time for Me hadn’t given me that push. (p. 41)

Facilitating engagement

In four studies (Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Perry et al., Citation2008; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018; White et al., Citation2010), participants highlighted various issues that could help or hinder their engagement. For example, mothers in the Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy intervention, expressed how they would have liked to have had further information about what to expect from the type of art being created and how their babies would be involved. Whereas those in Wahlbeck et al.’s (Citation2018) art therapy study valued the artist providing them with a framework for what to produce, thereby providing a ‘therapeutic guideline’ (p. 302) they could follow.

Some participants in Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy study liked how the therapist painted with them rather than observing what they were doing and valued not being placed under pressure to create ‘something that had meaning’ (p. 11). Participants also referred to different components that helped them to relax, such as having flexibility in arrival times, being given a cup of tea (Moriarty et al., Citation2022) or being provided with guided relaxation (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). Parents in Perry’s (Citation2008) creative arts and Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy studies also spoke of how the supportive and relaxed environment, where everyone (including the art therapist) ‘was so nice’ (p. 41.), gave them the courage and motivation to keep attending. Although the professional artists in White et al.’s (Citation2010) creative arts study expressed challenges of engaging with parents in the neonatal unit due to them being in a heightened state of anxiety. Some of the mothers in Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy intervention also commented on contextual-related issues such as the need for suitable space, ‘I think if you’d had more people that room would not have worked’ (p. 13), furniture (i.e. due to chairs not being suitable for breastfeeding), and optimum group size (i.e. four mothers and babies) to enable women to develop trust-based relationships and to feel comfortable in disclosing their issues or concerns.

Discussion

The review synthesised existing evidence on the mental health and well-being impacts of art therapy and creative art-based interventions provided for perinatal parents in the first 1000 days, to understand if and how these interventions made a difference and to identify any facilitators and barriers to parent engagement. Collectively the review findings found that visual art-based interventions created a safe and non-judgemental space with positive implications for increased self-awareness, self-esteem, and confidence. The interventions were reported to help parents develop coping strategies, to build intra- and interpersonal connections, and to facilitate wider help-seeking behaviours. Key factors that appeared to influence parent engagement related to information provision, the use of relaxation methods and the interpersonal skills of the facilitators. The included studies were of art therapy and creative arts which are very distinct interventions. Art therapists are trained to understand and deal with the psychological and emotional needs of clients, whereas creative-arts interventions, led by other professionals (e.g. arts officer, or specialist health visitor), are more situated with a social prescribing team. Further consideration of the findings revealed important differences based on the type of art-based intervention, with more widespread and profound impacts being noted within the art therapy studies. Below we summarise the key findings and draw distinctions between the intervention types to highlight their respective value.

In line with art therapy’s focus of enabling individuals to focus on their feelings and address internal conflict (Farokhi, Citation2011; Hogan, Citation2001), parents involved in art therapy interventions reflected on how their involvement had helped them to become more aware of their mental health issues (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Ponteri, Citation2001; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). Whilst parents who accessed creative arts interventions reported how this had been beneficial as a distraction only (White et al., Citation2010), art therapy was more likely to be reported to have facilitated healing by enabling parents to focus on and work through their mental health concerns (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Swan-foster, Citation1989 Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018;).

Similar to findings from other arts-based interventions (Gallo et al., Citation2021; Jensen & Bonde, Citation2018; Macpherson et al., Citation2016) the included studies highlighted various salutary impacts such as self-esteem and confidence-building (Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Perry et al., Citation2008; Ponteri, Citation2001; Swan-foster, Citation1989; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018; White et al., Citation2010). Neither of the art therapy RCTs reported significant impacts (Jouybari et al., Citation2018; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2020). However, this could be due to both the intervention and control group receiving counselling by midwifes in Wahlbeck et al.’s (Citation2020) trial, reflecting earlier studies on the beneficial effects of midwifery counselling (Christiaens et al., Citation2011; Larsson et al., Citation2019; Larsson et al., Citation2015; Toohill et al., Citation2014). Whereas the RCT by Jouybari et al. (Citation2018) only provided a limited number of art therapy sessions (n = 3). From the qualitative evidence, those involved in art therapy interventions were more likely to report a deeper level of change by enabling parents to develop new self-identities (Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Ponteri, Citation2001; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018) and capabilities (Swan-foster, Citation1989; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). While parents involved in creative arts reported feeling ‘proud’ of their artwork (Perry et al., Citation2008), those involved in art therapy reported ‘mammoth’ personal change (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018) facilitated through the object relations of what they had created (Hogan et al., Citation2017). Further personal change reported by parents involved in art therapy related to positive impacts on their relationships with partners (Jalambadani et al., Citation2019; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018) and in communicating their needs to other providers (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018); impacts that were not reported in the creative arts interventions.

The use of malleable materials in art therapy is believed to be important to heighten primitive maternal senses, to stimulate conscious and unconscious maternal representations, and to help uncover what is influencing their relationship to their infant (Araneda et al., Citation2009; Slade et al., Citation2009). Parents in several of the included art therapy interventions felt their engagement had facilitated a positive relationship with their fetus and/or infant (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Ponteri, Citation2001; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). While these positive effects were not reflected in the art therapy RCT by Jouybari et al. (Citation2018) this could be due to targeting parents of infants admitted to neonatal care, and who likely had health concerns about their infant. Furthermore, while some of the parents involved in White et al.’s (Citation2010) creative arts study felt that the activities helped them to focus on and feel closer to their baby, many did not report feeling any differently.

Group art therapy is perceived to have benefits of allowing individuals to share their feelings, thoughts, and drawings, and foster imitative behaviour to help establish their own self-identity (Choi & Goo, Citation2012). This was reflected in the included group-based art therapy interventions, with parents valuing opportunities to connect with others from shared backgrounds (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Ponteri, Citation2001; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018) and how these communal opportunities helped them to develop their sense of self (Ponteri, Citation2001). A key difference between the intervention types was noted in terms of a group membership. For example, while mothers in Wahlbeck et al.’s (Citation2018) art therapy study reported valuing sharing insights with those who understood their realities, mothers in Perry et al.’s (Citation2008) creative arts study faced challenges when their experiences did not resonate with others. A similar finding was also highlighted in the systematic review and meta-ethnography by Jones et al. (Citation2014) that explored the impact of peer support in the context of perinatal mental illness. They found that when women’s experiences were not shared with others, this compounded feelings of disengagement and isolation. Furthermore, while parents in Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy study described strong relationships that continued outside of the sessions, mothers in Perry et al.’s (Citation2008) study expressed disappointment when other mothers did not want to continue the relationships after the group had ended. These variations in experiences highlight how art therapy seems to cultivate a group that can stimulate healing rather than for general socialisation purposes (Liebmann, Citation2004). Although, as some of the women in Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy group expressed reticence in what was disclosed, this suggests that ongoing consideration of the different needs of group members is warranted.

Factors that influence parental engagement were only reported in three studies (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021: Moriarty et al., Citation2022; White et al., Citation2010). While more obvious issues of feeling welcomed were raised (Bruce & Hackett, Citation2021; Perry et al., Citation2008; Ponteri, Citation2001), those who attended art therapy sessions valued being taught relaxation techniques (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). Mothers in Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy study also reflected on the importance of room size in restricting the number of parents who could attend. A smaller group was preferred, as this was considered important to facilitate group bonding (Moriarty et al., Citation2022), and in the wider literature, group size is believed important to enable cooperation and altruism (Powers & Lehmann, Citation2016). The need for clear information was highlighted (Moriarty et al., Citation2022; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). While complaints were raised about a lack of information concerning the art activities in Moriarty et al.’s (Citation2022) art therapy study, this may be due to different professionals being involved (art therapist, specialist health visitor and a nursery nurse): although the role and remit of these different professionals is not reported in the paper. Developing good relationships between the therapist and the parent was also highlighted as important. For example, in the study by Moriarty et al. (Citation2022) parents valued the therapist painting alongside them, aligning with art therapy’s ethos of forming trusting relationships based on presence, empathy and mirroring (Malchiodi, Citation2018); with trust perceived to be one of the key agents for change in this context (Fonagy & Luyten, Citation2018). Whereas in White et al.’s (Citation2010) creative arts study, the artists experienced difficulties engaging with parents due to the highly stressful neonatal environment; a finding potentially related to their lack of psychological training.

Strengths and limitations

The systematic review was undertaken with best practice principles and adopted an inclusive approach to enable a comprehensive understanding. Overall, the review identified a paucity of studies that examined visual art-based interventions within the first 1000 days and most studies focused exclusively on mothers. Although it was noted in one of the studies that while male parents were invited, they did not take-up the offer (Jouybari et al., Citation2018). Only two of the studies utilised a robust methodological design with measurement outcomes. Three of the studies were rated as low-quality, and eight of the included studies were undertaken in high-income countries. The studies lacked sociodemographic details, had small sample sizes, and included different interventions with different phases and implemented at different lengths of time during the perinatal period: all of which limits the generalisability of the findings.

Implications for policy and practice and future research

While most of the included studies involved art therapy, this modality was associated with wider and more substantial impacts when compared to those that were creative arts. There is a need for more robust evaluation methods including RCTs and alongside process evaluations to examine impacts and mechanisms of effectiveness of art therapy within different perinatal populations. There is also a need for longitudinal studies to study the effects over time. Group-based visual arts interventions need to be mindful of the background and experiences of included parents to optimise their potential benefits.

Conclusion

The findings from this integrative review indicate a paucity of research exploring visual art-based interventions to improve perinatal mental health in the first 1000 days. Most of the included studies were art therapy and while creative arts studies showed some benefits, this was to a different level and intensity than those delivered by a trained therapist. The process of creating art, supported by a trained therapist, stimulated self-awareness, healing and positive change for the self, parent-infant bonding, and relationships. Group-based art therapy also helped parents to foster new connections and friendships which could assist in reducing social isolation and loneliness. While barriers to engagement were generally reported in creative arts, rather than art therapy interventions, this underlies challenges of artists being in situations that may be beyond their training and skills. More robust studies with alongside process evaluations to help uncover the mechanisms of effectiveness within perinatal art therapy interventions are needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joanne Harris

Joanne Harris is a PhD student and works as a Research Associate at the University of Central Lancashire. Joanne’s academic background is in education and sociology. Her research interests span many different disciplines including sociology of childhood, perinatal mental health, co-production of research with a specific focus on how intersecting identities impact children’s mental health and well-being.

Rebecca Nowland

Rebecca Nowland is currently working as a Senior Research Fellow in the Maternal and Infant Nutrition and Nurture (MAINN) Research Unit at the University of Central Lancashire. Rebecca has a psychology academic background. Her research interests concern social influences on physical and mental health, with a particular interest in loneliness.

Jayneequa Peart

Jayneequa Peart is a 2nd year undergraduate psychology student who worked on the project as part of a 10-week research internship.

Gill Thomson

Gill Thomson is currently working as a Professor in Perinatal Health at the University of Central Lancashire. Gill has a psychology academic background and a PhD in Midwifery. Her research interests concern the influences and impact of perinatal mental health on maternal and family wellbeing, with a particular interest in birth trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder onset following childbirth, and peer support models of care.

References

- Anolak, M. H. (2022). Creative arts intervention in support of women experiencing a high-risk pregnancy. Women and Birth, 35, 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2022.07.020

- Araneda, M. E., Santelices, M. P., & Farkas, C. (2009). Building infant–mother attachment: The relationship between attachment style, socio-emotional well-being and maternal representations. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 28(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830903294987

- Armstrong, V. G., & Howatson, R. (2015). Parent-infant art psychotherapy: A creative dyadic approach to early intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(2), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21504

- Armstrong, V. G., & Ross, J. (2020). The evidence base for art therapy with parent and infant dyads: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(3), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1724165

- Arroyo, C., & Fowler, N. (2013). Before and after: A mother and infant painting group. International Journal of Art Therapy, 18(3), 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2013.844183

- Bauer, A., Parsonage, M., Knapp, M., Lemmi, V., & Adelaja, B. (2014). Costs of perinatal mental health problems. Personal Social Services Research Unit.

- Bhat, A., Ratzliff, A., Unützer, J., & Reed, S. D. (2017). Consensus bundle on maternal mental health: Perinatal depression and anxiety. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(2), 466–467. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002176

- Bruce, D., & Hackett, S. S. (2021). Developing art therapy practice within perinatal parent-infant mental health. International Journal of Art Therapy, 26(3), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1801784

- Case, C., & Dalley, T. (2006). The handbook of art therapy. Routledge.

- Choi, S., & Goo, K. (2012). Holding environment: The effects of group art therapy on mother–child attachment. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2011.11.001

- Christiaens, W., Van De Velde, S., & Bracke, P. (2011). Pregnant women's fear of childbirth in midwife- and obstetrician-led care in Belgium and the Netherlands: Test of the medicalization hypothesis. Women & Health, 51(3), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2011.560999

- Crane, T., Buultjens, M., & Fenner, P. (2021). Art-based interventions during pregnancy to support women’s wellbeing: An integrative review. Women and Birth, 34(4), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.08.009

- Cronin, M. A., & George, E. (2020). The why and how of the integrative review. Organizational Research Methods, 26(1), 168–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120935507

- Demontigny, F., Girard, M.-E., Lacharité, C., Dubeau, D., & Devault, A. (2013). Psychosocial factors associated with paternal postnatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.048

- Evans, N. (2019). Why the first 1,001 days are vital to childcare. Nursing Children and Young People, 31(1), 8–9. https://doi.org/10.7748/ncyp.31.1.8.s7

- Farokhi, M. (2011). Art therapy in humanistic psychiatry. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2088–2092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.406

- Fonagy, P., & Luyten, P. (2018). Attachment, mentalizing, and the self. In W. J. Livesley & R. Larstone (Eds.), Handbook of personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 123–140). The Guilford Press.

- Gallo, L. M., Giampietro, V., Zunszain, P. A., & Tan, K. S. (2021). COVID-19 and mental health: Could visual art exposure help? Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.650314

- Hogan, S. (2001). Healing arts: The history of art therapy. Jessica Kingsley.

- Hogan, S., Sheffield, D., & Woodward, A. (2017). The value of art therapy in antenatal and postnatal care: A brief literature review with recommendations for future research. International Journal of Art Therapy, 22(4), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1299774

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/efi-180221

- Hosea, H. (2006). ‘The brush's footmarks’: parents and infants paint together in a small community art therapy group. International Journal of Art Therapy, 11(2), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830600980317

- Howard, L. M., Piot, P., & Stein, A. (2014). No health without perinatal mental health. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1723–1724. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62040-7

- Jalambadani, Z., Borji, A., & Bakaeian, M. (2019). Examining the effect of mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) on stress and lifestyle of Iranian pregnant women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 40(6), 779–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2019.1652889

- Jensen, A., & Bonde, L. O. (2018). The use of arts interventions for mental health and wellbeing in health settings. Perspectives in Public Health, 138(4), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913918772602

- Jones, C. C. G., Jomeen, J., & Hayter, M. (2014). The impact of peer support in the context of perinatal mental illness: A meta-ethnography. Midwifery, 30(5), 491–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.08.003

- Jouybari, L., Abbariki, E., Jebeli, M., Mehravar, F., Asadi, L., Akbari, N., Sanagoo, A., & Moradi, Z. (2018). Comparison of the effect of narrative writing and art therapy on maternal stress in neonatal intensive care settings. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 33(4), 664–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2018.1499719

- Larsson, B., Hildingsson, I., Ternström, E., Rubertsson, C., & Karlström, A. (2019). Women’s experience of midwife-led counselling and its influence on childbirth fear: A qualitative study. Women and Birth, 32(1), e88–e94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.04.008

- Larsson, B., Karlström, A., Rubertsson, C., & Hildingsson, I. (2015). The effects of counseling on fear of childbirth. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 94(6), 629–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12634

- Liebmann, M. (2004). Art therapy for groups a handbook of themes and exercises. Taylor and Francis.

- Macpherson, H., Hart, A., & Heaver, B. (2016). Building resilience through group visual arts activities: Findings from a scoping study with young people who experience mental health complexities and/or learning difficulties. Journal of Social Work, 16(5), 541–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017315581772

- Malchiodi, C. (2018, May 30). Art therapy: The role of the relationship. Does art therapy effectively support relational treatment goals? Psychology Press.

- McNab, S., Fisher, J., Honikman, S., Muvhu, L., Levine, R., Chorwe-Sungani, G., Bar-Zeev, S., Hailegebriel, T. D., Yusuf, I., Chowdhary, N., Rahman, A., Bolton, P., Mershon, C.-H., Bormet, M., Henry-Ernest, D., Portela, A., & Stalls, S. (2022). Comment: Silent burden no more: A global call to action to prioritize perinatal mental health. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04645-8

- Moriarty, Y., O'Neill, C., Robling, M., Arroyo, C., & Owen, O. (2022). Feasibility of recruiting mother-infant dyads with mild-moderate depression to an art therapy painting group. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1489112/v1

- NHS England. (2019). The NHS long term plan.

- NICE. (2011, May 25). Recommendations: Common mental health problems: Identification and pathways to care: Guidance. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg123/chapter/Recommendations

- Oermann, M. H., & Knafl, K. A. (2021). Strategies for completing a successful integrative review. Nurse Author & Editor, 31(3–4), 65–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/nae2.30

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

- Perry, C., Thurston, M., & Osborn, T. (2008). Time for me: The arts as therapy in postnatal depression. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 14(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.06.001

- Ponteri, A. K. (2001). The effect of group art therapy on depressed mothers and their children. Art Therapy, 18(3), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2001.10129729

- Powers, S. T., & Lehmann, L. (2016). When is bigger better? The effects of group size on the evolution of helping behaviours. Biological Reviews, 92(2), 902–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12260

- Ramchandani, P. G., O’Connor, T. G., Evans, J., Heron, J., Murray, L., & Stein, A. (2008). The effects of pre- and postnatal depression in fathers: A natural experiment comparing the effects of exposure to depression on offspring. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(10), 1069–1078. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02000.x

- Slade, A., Cohen, L. J., Sadler, L. S., & Miller, M. (2009). The handbook of psychology and psychopathology of pregnancy. In C. H. Zeanah (Ed.), Handbook of infant mental health (3rd ed., pp. 22–39). Guilford Press.

- Stadtlander, L. (2015). Paternal postpartum depression. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 30(2), 11–13. Retrieved 2022, from .https://web.s.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=c9b95955-af81-437e-b45f-7395a0e8adb6%40redis

- Swan-foster, N. (1989). Images of pregnant women: Art therapy as a tool for transformation. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 16(4), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-4556(89)90051-8

- The British Association of Art Therapists. (2022, September 7). What is art therapy? Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://baat.org/art-therapy/what-is-art-therapy/

- Toohill, J., Fenwick, J., Gamble, J., Creedy, D. K., Buist, A., Turkstra, E., & Ryding, E. L. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of a psycho-education intervention by midwives in reducing childbirth fear in pregnant women. Birth, 41(4), 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12136

- Wahlbeck, H., Kvist, L. J., & Landgren, K. (2018). Gaining hope and self-confidence – an interview study of women’s experience of treatment by art therapy for severe fear of childbirth. Women and Birth, 31(4), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.10.008

- Wahlbeck, H., Kvist, L. J., & Landgren, K. (2020). Art therapy and counseling for fear of childbirth: A randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy, 37(3), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2020.1721399

- Walsh, D., & Downe, S. (2006). Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery, 22(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2005.05.004

- White, M. P., Anderdson, S., Stansfield, K. E., & Gulliver, B. (2010). Parental participation in a visual arts programme on a neonatal unit. Infant, 6(5), 165–169.

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x