ABSTRACT

Background: Like other health care professionals, art therapists are required to write clinical notes. As well as following general rules regarding this practice, art therapists must consider how client artwork and art-making are reflected in notes. This subject is inadequately covered in the literature, and research is needed to expand the knowledge base and contribute to developing best practice.

Aims: The aim of this research is to examine current practices, challenges and perceived benefits or drawbacks of reflecting client artwork and art-making in clinical notes, from the viewpoint of art therapists.

Methods: To obtain rich, qualitative data, three semi-structured interviews were carried out with qualified art therapists. The data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis to identify themes.

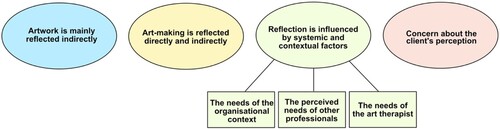

Results: Four themes were identified. These were: ‘Artwork is mainly reflected indirectly’, ‘Art-making is reflected directly and indirectly’, ‘Reflection is influenced by systemic and contextual factors’ and ‘Concern about the client’s perception’.

Conclusions: Significant findings were arrived at, which broaden understanding of how client artwork and art-making are reflected in clinical notes by early-career art therapists and factors that influence and shape this practice.

Implications for practice/policy/future research: This research raised awareness of both the complexity and the possibilities involved in reflecting client artwork and art-making in clinical notes. It drew attention to the need for greater sharing of experience and knowledge within the profession so that best practice can be developed.

Plain-language summary

Art therapists, like other health care professionals, must write clinical notes. There are general principles that guide note writing, but art therapists have the additional task of deciding how to reflect client artwork and art-making. A search of the art therapy literature revealed that there was very little discussion about the subject.

To address this, three interviews with art therapists were carried out. The questions were designed to explore how art therapists reflect client artwork and art-making in their notes and what they felt were the challenges and benefits of this practice.

By using thematic analysis, the data were broken down into codes and grouped into themes. Reflective art-making was carried out to raise awareness of any personal bias that might influence the results. Finally, four themes were identified. The first of these focused on participants’ practice of mainly reflecting final artwork indirectly. The second theme described ways in which the art-making process is reflected directly and indirectly. The third theme identified that reflection on artwork and art-making is influenced by the needs of third parties with vested interests. The fourth theme highlighted caution around language, due to concern about how the client might feel when reading their notes.

This research is useful to art therapists because it promotes discussion on the many factors involved in writing about client artwork and art-making in clinical notes and encourages good practice to be developed and shared within the profession.

Introduction

Art therapists, like other health care professionals, must write clinical notes (also known as progress notes). The British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT) (Citation2014, p. 11) describes clinical notes as ‘the official record that the art therapist produces to represent the clinical work that they have been doing with a client to third parties with vested interests’. As the practice of writing notes is a professional requirement and a means of communicating with other people involved in a client’s care, one would assume that it is thoroughly discussed in the literature. However, there is a lack of information in the art therapy handbooks, and only one peer-reviewed article that addresses the practice directly (Coles, Citation2018). For art therapists, integral to the task, is a consideration of how client artwork and art-making is reflected. Topics related to this aspect of note writing, such as ‘confidentiality’ and ‘interpretation’, are useful, but nowhere is relevant information gathered together and discussed. Moon’s (Citation2002, p. 268) impassioned discourse, encouraging art therapists to risk feeling ‘foolish’ when writing about client artwork and art-making, inspires questions about what the potential is for this practice and which factors shape the task. This research focuses on the thoughts and experiences of early-career art therapists as they seek to reflect client artwork and art-making in clinical notes.

Literature review

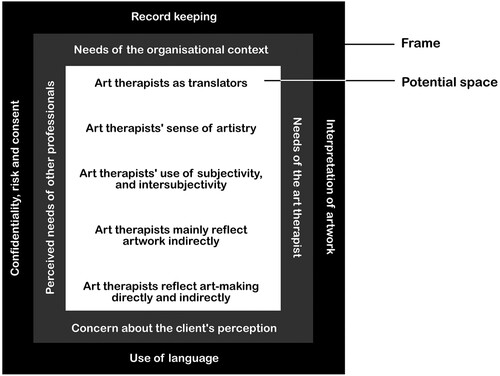

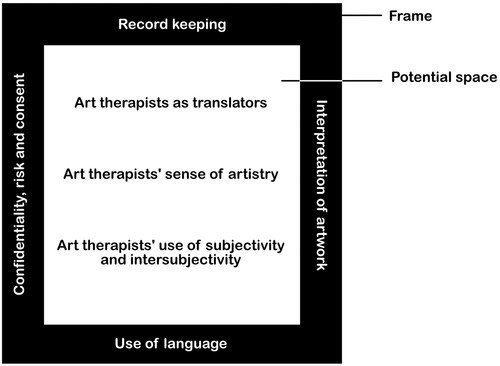

Literature relevant to the research topic appeared to fall into one of two categories. The first category seemed best characterised by the idea of the ‘frame’, as used by Milner (Citation1952, p. 181), to describe the physical and psychological boundaries of the art therapy session. In this context, the ‘frame’ could be said to comprise anything that shapes the way client artwork and art-making are reflected. This includes legal and ethical issues such as the requirement to keep records, confidentiality, risk and consent, interpretation of artwork and use of language. The second category appeared to embody the concept of ‘potential space’, as used by Winnicott (Citation1971/Citation2005) to describe the interpersonal space within which one can play. In the case of clinical notes, the ‘potential space’ could be ascribed to the memory of the session in the mind of the therapist and the translation of aspects of it into written words. Coles (Citation2018, p. 101) writes that within the ‘framework’ of requirements for note writing, there is ‘leeway’, but it seems that the possibilities afforded by this freedom are rarely explored in art therapy literature. Notable exceptions to this are the writings of Moon (Citation2002), in her exploration of the art therapist as translator, Coles (Citation2018), who teases out the artistry which can enrich the space, and Hardy (Citation2013), who advocates for bolder use of intersubjectivity in notes. These themes are explored in further depth below. The ‘frame’ and the ‘potential space’ of note writing, which emerged from the literature, are represented as a diagram in .

Figure 1. Diagram showing topics from the literature review, represented as a ‘frame’ and a ‘potential space’.

The frame

The requirement to keep records

An ambivalence towards note writing can be detected in art therapy literature, where it is referred to as ‘peripheral work’ (Case & Dalley, Citation2014, p. 12) and not the most ‘rewarding’ part of the job (Edwards, Citation2014, p. 73). BAAT (Citation2014) simply states that clinical notes are ‘mandatory’, 'the best means of evidencing work’ and ‘should describe what happened’ (pp. 11, 13). From the small amount of literature on the subject, it is clear that there is no one way to write notes and very little reference to how, or if, client artwork or art-making should appear in them. Hogan and Coulter (Citation2014, p. 214) state that ‘briefer notes are preferred’ and write that staff just want to confirm attendance and whether the client has had any issues or concerns.

Confidentiality, risk and consent

Confidentiality is the ‘cornerstone of the therapeutic alliance’ (Moon Citation2015, p. 32) and extends to a client’s artistic expression (Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), Citation2013). Despite this, clients should be told that confidentiality is held by the treatment team and will be overridden if the therapist believes the client, or someone else, is at risk (BAAT, Citation2019). Hogan and Coulter (Citation2014, p. 59) write that clients should be made aware of with whom reflections on their artwork and art-making will be shared and assert that there is an ethical responsibility to report images of risk. Case and Dalley (Citation2014) add some caution to this view when they write that an image or art process alone may not be enough to indicate risk and the client should be supported to explore its meaning.

Interpretation of artwork

Case and Dalley (Citation2014, p. 98) affirm the non-interpretive stance of British art therapy when they state that, in relation to artwork, meaning can only be arrived at collaboratively with the client. BAAT (Citation2014, p. 10) lays out the legal position on the interpretation of artwork when it states that artwork is ‘non-literal’, has ‘non-fixed meaning’ and is ‘highly ambiguous’ and, as such, cannot stand alone as evidence; BAAT also says that assurance should be given to the client that their artwork will not be analysed by the art therapist without their involvement. To protect against this, Hogan and Coulter (Citation2014) promote a cautious attitude to describing artwork in notes, asserting that it can lead to the art therapist being questioned about its meaning.

Use of language

Kapitan and Kapitan (Citation2023) write passionately about the need for art therapists to be self-reflexive about how they use words in clinical notes. They advocate for language that ‘centres around care’ and avoids ‘dehumanising, invisibilising and pathologising’ (p. 66). The Data Protection Act (Citation2018) gives clients and their representatives the right to access their records, and it is important for them to see themselves written about respectfully (Kapitan & Kapitan, Citation2023; Coles, Citation2018; Moon, Citation2002; Spaniol & Cattaneo, Citation1994). Research has highlighted the variability of language that is used by art therapists and the difficulty that this could cause when communicating with other professionals (Van Lith & Bullock, Citation2018). To address potential confusion, Kwok et al. (Citation2022) designed a post-session documentation tool for art therapists, listing eight common art interventions such as ‘Third Hand Technique’ (p. 16). They recognised the risk of oversimplification and suggested that the tool should be used in conjunction with training, to provide other professionals with a more nuanced understanding of client artwork and art-making.

The potential space

Art therapists as translators

The tension that lies at the heart of writing art therapy clinical notes, is the need to translate into words a form of psychotherapy that uses visual media as its primary mode of communication. Moon (Citation2002) writes that art therapists must speak many overlapping languages such as ‘truth and fiction; artistic language and the language of therapy; words and enactments; and universality, cultural context and idiosyncratic expression’ (p. 242). Spaniol and Cattaneo (Citation1994, p. 268) use the quote, ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’, to remind readers of how much can ‘get lost in translation’, especially as notes are generally kept short. Art therapists must also translate ‘raw undigested material’ into ‘thinking’ (Brown et al., Citation2003, p. 72), a process Coles (Citation2018) writes about when she describes the psychological processing that occurs when she translates the aesthetic content of the session into clinical notes.

Art therapist’s sense of artistry

In the words of Coles (Citation2018, p. 101), writing clinical notes is a ‘creative act’; she promotes using the language of the artist and paying attention to the aesthetic qualities of sessions such as ‘flow, shape, colour, texture and sound’ (2018, p. 102). In trying to express what has happened in a session, Spaniol and Cattaneo (Citation1994, p. 269) and Moon (Citation2002, p. 268) write that they try to paint a picture with words, referring to their clinical notes ‘word-pictures’. Similarly, Coles (Citation2018, p. 103) writes: ‘I’m not presenting a photographic representation but more of a landscape painting’. Hardy (Citation2013, p. 36) emphasises the need for art therapists to continue engaging in their own art-making if they are to write notes that are ‘more attuned to the creativity of our clients’; he focuses on the ‘materiality’ (p. 34) of language to convey the intensity of sessions, while Moon (Citation2002, p. 270) suggests that art therapists use ‘a poetic-based language’.

Art therapists’ use of subjectivity and intersubjectivity

BAAT (Citation2014) states that to demonstrate clinical reasoning in notes, both ‘subjective’ information, which includes countertransference, and ‘objective’ information are valid. BAAT clarifies that the language used when writing subjectively needs to make clear that it is an ‘impression or hearsay’ (p. 16). Attitudes to subjectivity in clinical notes differ between art therapists. Hogan and Coulter (Citation2014) promote stating only the facts and not including any subjective views, while Coles (Citation2018, p. 103) writes: ‘I’m not pretending that my notes are anything more than my impressions. The notes appear under my name – the mind behind the notes is visible’. Hardy (Citation2013, p. 30) advocates for art therapists to use a less ‘objectified’ vocabulary in their notes and make the intersubjective nature of the work clear. Similarly, Coles (Citation2018, p. 102) states: ‘when writing clinical notes, we are attempting to give shape to a highly complex, multi-layered interaction’.

Aim

BAAT’s (Citation2014) observation that exploration of law and practice is often ‘inhibited by anxiety’ (p. 1) may provide a clue as to why there is so little discussion about note writing in the literature. Coles (Citation2018, p. 104) identifies the danger of this when she writes that, ‘responsible professional practice, involves interrogating what we do in order to ensure that we provide the best possible service to our clients’. This qualitative study aimed to address the deficit by examining current practices, challenges and perceived benefits or drawbacks of reflecting client artwork and art-making. Interviews with art therapists were carried out with the aim of expanding the knowledge base and helping to develop best practice.

Method

Data collection

To gather the insights of art therapists, qualitative data were collected via semi-structured interviews using a method developed by DeJonckheere and Vaughn (Citation2019). Ethical approval was granted by the University of South Wales research ethics committee. Due to the time constraints of the study, it was decided that three participants would be manageable to interview. With regard to the small sample size, DeJonckheere and Vaughn (Citation2019) state that the aim is not a large number of participants but an in-depth understanding of their thoughts, feelings and experiences. Participants were recruited through an advert on the professional network. Interview questions were developed out of perceived gaps in the existing art therapy literature to stimulate thought and prompt a broad range of feedback. A first iteration of questions was tested and adapted before deciding on five open-ended questions. (For the full interview protocol, see the supplementary appendix.) Interviews were conducted online to ensure accessibility, irrespective of the geographical constraints of participants. Interviews were then transcribed and anonymised. For basic demographic information about the participants, see .

Table 1. Basic demographic information about the participants.

Analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis (TA) was chosen as the preferred method for analysing the data, as it can help identify ‘shared-meaning’ based themes and is recommended for research seeking ‘clear implications for practice’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2020, p. 42). Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) take a flexible approach to sample size in reflexive TA, but indicate that ‘information power’ (Malterud et al., Citation2016) is a useful concept to consider. Reflexive TA involves six phases: ‘familiarisation’, ‘coding’, ‘generating initial themes’, ‘reviewing and developing themes’, ‘refining, defining and naming themes’ and ‘writing up’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2020).

Reflexivity

Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) state that themes are actively generated by the researcher at the intersection between the data and the researcher’s interpretive frameworks – their skills, their training and their assumptions. They emphasise the role of researcher reflexivity in identifying personal bias that might distort or influence how data are read. To support this process, reflexive art-making was undertaken by the researcher to visually respond to the data (see ).

The resulting image brought to mind a water game where the ‘bomb’ is thrown from player to player until it explodes and soaks the catcher. This image became an ‘object of enquiry’ (McNiff, Citation1998, p. 15), vividly exposing the researcher’s anxiety about note writing. This anxiety was rooted in the experience of being an MA art psychotherapy student, in an NHS placement, where the task of note writing gave rise to many questions and few clear answers. Discovering that a patient had requested to read their notes caused even greater anxiety. This experience, combined with the request by each of the participant’s to see a final copy of the research, gave rise to a parallel process, in which concern about how a client would feel if they read their clinical notes was also applied to how participants would feel when reading their views represented in the research. The researcher became aware that re-experiencing these feelings was amplifying previously felt anxiety and influencing the creation of themes. Following these realisations, code was regrouped and new themes and sub-themes were identified.

Results

During reflexive TA four main themes and three sub-themes were identified (see ).

Theme 1: artwork is mainly reflected indirectly

All the participants said that they are cautious about reflecting client’s artwork directly. P1 acknowledged differences between types of image: ‘I feel like some artwork is more sensitive, and so I probably wouldn't say as much about that’. P3 expressed care around interpretation: ‘I refrain from going into detail because I want that to stay within the triangular relationship and not be taken in an unhelpful way by other disciplines’. P2 sensed the difficulty of translation: ‘to try and put it into words would do a disservice because it would be filtered through my lens’. P2 addressed this by saying that they only share ‘themes’. Participants were also cautious about reflecting directly on images of risk. P1 said: ‘I would be explicit that it showed self-harm or suicidal ideation. I wouldn’t give details of what the image was’. P3 voiced similar views and said: ‘there's only so much detail you need to go into to keep that individual safe’. P2 said that they were more likely to reflect artwork indirectly as ‘an object in the relationship’ and note ‘how kind of engaged were they with my thinking’. P3 noted whether the artwork was ‘an embodied image’ and felt that notes should include the client’s ‘relationship to the artwork’.

Theme 2: art-making is reflected directly and indirectly

With regard to the art-making process, participants gave examples of both direct and indirect reflections. P1 said that they are more likely to write about ‘doing, rather than the work’ and that personal experience of art-making informs their reflections: ‘you have an understanding of what it feels like to make art and you’ve got that language that comes with it’. P2 noted what materials were chosen and how they were used: ‘the tactile quality of their anger and working it through with the clay’. P2 also spoke about their use of indirect reflections to note ‘engagement’, ‘did they paint for the full session and not say anything?’. P1 highlighted the need to reflect things that ‘there isn’t the language for, that sense of being in the room’ and ‘vitality effects’.

Theme 3: reflection is influenced by systemic and contextual factors

Sub-theme: the needs of the organisational context

P3 said that the organisational context impacted the length of their notes; ‘when you've got more time, you might write a more detailed note and then other times you don't’. P3 also talked about the pressure to write more, ‘to justify’ art therapy as an intervention. With regard to thought processes, P1 sensed a preference in one organisation for ‘more psychological thinking’, while P3 perceived hesitation, in another organisation, around using ‘speculative language’. In reference to the way art therapy is recorded, P3 described the possible introduction of an ‘outcome measure’, which would have required a formulaic way of recording client artwork and art-making including, ‘the implied energy, the space, the interrogation logic, realism, problem solving, development level, details of objects and environments’.

Sub-theme: the perceived needs of other professionals

Participants said that they recorded details about the artwork and art-making that they felt would be useful to other professionals in the care team. P3, who worked on an acute ward, said that they noted ‘paranoia’, ‘risk’ and ‘cognitive impairment’. P2 said that they included aspects which ‘add a human element that might give hope to other medical professionals’, while P3 tried to ‘give ideas of how to engage with the patient’. In terms of factors with the potential to inhibit what was reflected, participants named lack of understanding among other professionals. P3 said: ‘the unknown, the flexibility, the creativity of the intervention doesn’t sit well with everyone’. P2 drew attention to the lack of privacy in the NHS, as an inhibiting factor, and said: ‘I feel the need to protect the client from the all-seeing eye’.

Sub-theme: the needs of the art therapist

The needs of the art therapist have the potential to impact how they reflect client artwork and art-making in clinical notes. With regard to emotional containment, P3 described ‘that relief of handing it over’ and ‘that offload of what the experience was like’. In relation to evidencing work, P1 said they were a way of ‘backing yourself up’. While reflecting on the use of notes in psychological processing, P1 said, ‘it can be really valuable in terms of how you think about a young person’. Using clinical notes as a memory prompt was highlighted by P2 who said, ‘sometimes it’s really helpful, if you’re doing an assessment, to just go back and think there was X, Y and Z and continue the assessment’. Similarly, P3 talked about recording the whereabouts of client’s artwork, because ‘if there is any disagreement you’ve always got to have in mind where it is’.

Theme 4: concerns about the client’s perception

Participants noted three main ways in which knowing that a client can request their notes, affects how they reflect client artwork and art-making. These were in caution around the amount of detail and subjective opinion, use of accessible language and in writing respectfully. P1 held in mind, ‘how much detail they would have wanted me to put down’, while P2 said: ‘for me, it's really important that I don't share my impressions too much’. P1 also recognised the need to write in understandable language: ‘you need to get the message across and they won’t necessarily have that therapeutic language’. Also with regard to language, P3 said that they try to ‘write in a very respectful way. I highlight concern and risk but I always, kind of say at the end, a positive’.

It was noted that all the participants interviewed in the research had been qualified for two years. This meant that the research only captured the views of early-career art therapists. shows a diagram incorporating the findings from the literature review with themes from the research. Themes 1 and 2 were incorporated into the ‘potential space’ as they explore the possibilities inherent to reflecting artwork and art-making. Themes 3 and 4 were added to the ‘frame’ as ethical and legal issues that shape clinical notes.

Discussion

Theme 1: artwork is mainly reflected indirectly

Caution around reflecting client artwork directly was described by some participants as a concern about how much detail is necessary for ongoing formulation. They balanced this against how much detail is needed to keep the client safe. In clinical notes, art therapists must contribute to understanding around a client’s needs (BAAT, Citation2014) and record risk, ‘where missing information could be dangerous’ (NHS, Citation2003, p. 29). BAAT (Citation2014, p. 1) writes that ‘reasoned judgement is required’ for art therapists to determine the amount of detail needed. They should also take into account the confidentiality agreement with the client, which may include specific details about how and with whom client artwork will be shared (American Art Therapy Association (AATA), Citationn.d.). One participant acknowledged the disservice that they feel is done when artwork is translated into words and voiced a preference to share themes instead of detail (Case & Dalley, Citation2014). Participants felt that describing artwork made it vulnerable to misinterpretation and linked this to Schaverien’s (Citation2000) concept of the ‘triangular relationship’, in which the meaning of artwork has to be understood within the three-way relationship between client, therapist and picture. It is within this context that participants said they would indirectly reflect client artwork, noting the client’s relationship with the artwork and whether it is an ‘embodied’ image. This draws on Schaverien’s (Citation1992) theory of transference and counter-transference in artwork. In contrast to caution around direct reflection of artwork (Case & Dalley, Citation2014; Hogan & Coulter, Citation2014), Coles (Citation2018, p. 103) writes that she does sometimes reflect ‘something concrete about a client’s art making process or product’, but this is reflected within the context of the therapeutic relationship. Coles asserts the value of this in bringing fresh insight to the multi-disciplinary team.

Theme 2: art-making is reflected directly and indirectly

The choice of art materials and how they are used, were given as examples, by participants, of how they reflect client art-making directly. This practice resonates with the writing of Moon (Citation2002, p. 246), who encourages art therapists to reclaim the ‘unique, action-orientated, here-and-now language of the arts’ and not let the experience of art-making become reduced to a discussion about the final artwork. The relationship between client and materials is most thoroughly explored in the Expressive Therapies Continuum (Hinz, Citation2020; Kagin & Lusebrink, Citation1978). One participant noted the need to use their own experience of art-making to write about the reaction of clients to different art materials. In order to make indirect reflections on art-making, one participant highlighted Stern’s (Citation2010) concept of ‘vitality affects’. Holmqvist et al. (Citation2019, p. 31) describe this as an ‘intra-subjective sense of energy, power, and meaning, a sense of aliveness’ and suggest that it provides a framework for art therapists to understand the non-verbal communication that arises between therapist and client during art-making. Recognising the intersubjective nature of art-making, Hardy (Citation2013, p. 35) encourages art therapists to avoid objectified language that writes ‘themselves out of the process’.

Theme 3: reflection is influenced by systemic and contextual factors

BAAT (Citation2014, p. 12) notes that there are a number of different ‘audiences’ for clinical notes, and it is useful to consider what information each group requires. This research identified that the needs of three of these audiences have a particular impact on how client artwork and art-making is reflected in clinical notes. These are the organisational context, other professionals and art therapists. The needs of the organisational context are stated as: service delivery, resource management and audit. One way these needs can be met is by using an outcome measure. This was mentioned by one participant and would have resulted in a prescriptive way of recording artwork and art-making. Nitsun (Citation1996, p. 160) observes that ‘the penetrating effects of the setting’ manifest themselves in many different ways. Participants felt pressure to write less, in response to there being no time, and more, to justify art therapy as an intervention. Coles (Citation2018) acknowledges time constraints when she writes: ‘I haven’t got long before my next client so I need to work quickly’. With regard to justification, BAAT (Citation2014, p. 13) states that art therapists should not detail ‘how in technical terms the therapy worked’. Other pressures were perceived as a need to use more psychological language and, in another context, less subjective thought. Kapitan and Kapitan (Citation2023) state the need to critically question the accepted practices of the workplace if it is not in the best interest of the client.

This research also identified that the needs of other professionals impacted on how client artwork and art-making are reflected in clinical notes. BAAT (Citation2014) states that other professionals use notes for continuity of care, handover and coordinating approaches. Participants felt the need to use language that clearly communicated the client’s experience of artwork and art-making (Kwok et al., Citation2022; Van Lith & Bullock, Citation2018). Additionally, participants spoke of the perceived need to humanise clients in their notes (Kapitan & Kapitan, Citation2023) by engaging colleagues at an emotional level (Coles, Citation2018; Moon, Citation2002).

Particpants expressed emotional and practical needs that were met by reflecting client artwork and art-making in clinical notes, creating a need for self-awareness that the therapists needs don't impinge on the rights of the client. An example of this might be in sharing what should be kept confidential in order to relieve the art therapist of anxiety. BAAT (Citation2014, p. 12) states that clinical notes provide art therapists with ‘an aide de memoir’, ‘legal protection’ and as a place for ‘processed feelings’. Coles (Citation2018) describes the role that writing clinical notes has for her, in the psychologically processing of the session. With regard to emotional containment, she also explores the role of note writing in ‘detachment’ from client work and in ‘holding’ client material between sessions. Bion (Citation1959), in his theory of the analyst as maternal container, also acknowledged the containment that putting experiences into words can provide.

Theme 4: concerns about the client’s perception

In her article, Coles (Citation2018) reflects on the question shared by participants: ‘what if a client were to see my notes?’ She acknowledges the subjective and intersubjective nature of her notes, a cause of concern for one participant, and openly wonders: ‘would they recognize the landscape – something we had both created’ (p. 103). Knowledge that clients might read their notes caused participants to focus on using accessible and respectful language. This is supported by Kapitan and Kapitan (Citation2023) who assert the need for art therapists to be conscious of their use of language and take responsibility for the impact of their words. Spaniol and Cattaneo (Citation1994) write that ‘it may be that hearing themselves talked about in respectful terms can help clients think about themselves in more respectful terms’ (1994, p. 270).

Limitations of the study

Three main limitations to the research were identified. The first was the small scale, which meant that findings were based on the experience of only three art therapists. Despite the rich data this generated, it would have been useful to capture the experience of a greater number of art therapists. A second limitation was that all of the participants had two years of post-qualification experience. As such, the views and experiences of art therapists who had been practicing for longer were not captured. Interviewing art therapists with different lengths of experience might reveal if approaches to the task change over time. The final limitation is that these participants responded to the advert. Self-selection bias may result in the participants not being representative of the group being studied, or in particular findings being exaggerated.

Implications for policy, practice and further research

The findings reveal the complexity of reflecting client artwork and art-making in clinical notes and affirm that the subject should be given dedicated space in any future handbook on art therapy. They also demonstrate that it would be beneficial if BAAT updated and added more detail to their guidelines on note writing and the law (Citation2014) and invited articles on the subject to be published in the International Journal of Art Therapy (IJAT) and Newsbriefing. Continuing professional development (CPD) courses on note writing could create space for discussion and sharing of knowledge. Further research is needed to seek out the voice of clients and other professionals with vested interests in clinical notes, as their perspectives would enrich the discussion and help art therapists to triangulate best practice.

Conclusion

This research was rooted in the questions the researcher, as an art therapy trainee on placement, had about writing clinical notes. By interviewing three early-career art therapists and analysing the data, a deeper insight was gained into the practice of reflecting client artwork and art-making in clinical notes. The four themes that were identified were: ‘artwork is mainly reflected indirectly’, ‘art-making is reflected directly and indirectly’, ‘reflection is influenced by systemic and contextual factors’ and ‘concern about the client’s perception’. Although the findings cannot be generalised, the research brought awareness of both the complexity and the possibilities of this practice and the need for focused discussion in art therapy literature and training. This research challenges the notion that it is a peripheral and unrewarding task (Case & Dalley, Citation2014; Edwards, Citation2014), suggesting that it is rather more central to the work of the therapist and full of opportunities. As well as providing a ‘frame’ of legal and ethical points to consider, a ‘potential space’ of possibilities is highlighted to help art therapists develop their own ‘unique note writing process and style’ (Coles, Citation2018, p. 103). This research ends with an invitation, to all those with vested interests in clinical notes, to share their experiences of writing or reading reflections on artwork and art-making. It is in doing this, that a practice will be developed, that best serves the needs of clients, for whom art therapy exists.

Declaration of interest statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Ethics

The author has written, informed consent to publish all participant feedback included in the paper.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my MA dissertation supervisor, Ali Coles, for her guidance and for contributing to the literature on art therapy and clinical notes. I would also like to thank the three art therapists who answered my call for participants and shared their experience of clinical note writing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kim Morgan

Kim Morgan qualified as an art psychotherapist in 2022. She studied at the University of South Wales and now works in the NHS with older people, in inpatient and Community Mental Health Teams.

References

- American Art Therapy Association (AATA). (n.d.). Best practice guidelines. Informed consent: Documenting, sharing, and presenting artwork by clients. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.arttherapy.org/upload/Ethics/Informed%20Consent-Clients.pdf

- Bion, W. R. (1959). Attacks on linking. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 40, 308–315.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT). (2014). Art therapy, note-writing and the law. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from www.baat.org/Assets/Docs/General/Art%20Therapy,%20Note%20Writing%20and%20The%20Law.pdf

- British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT). (2019). Code of ethics and principles of professional practice for art therapists. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.baat.org/Assets/Docs/BAAT%20CODE%20OF%20ETHICS%202019.pdf

- Brown, C., Meyerowitz-Katz, J., & Ryde, J. (2003). Thinking with image making in supervision. International Journal of Art Therapy, 8(2), 71–78. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830308414056

- Case, C., & Dalley, T. (2014). The handbook of Art therapy (3rd ed). Routledge.

- Coles, A. (2018). The Art of note writing: Art therapy and clinical notes (L’art de rédiger des notes : l’art-thérapie et les notes cliniques). Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 31(2), 101–104. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1080/08322473.2018.1522795

- Data Protection Act (DPA). (2018). Retrieved August 16, 2023, from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga /2018/12/contents/enacted

- DeJonckheere, M., & Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Semi-structured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), 1–8. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Edwards, D. (2014). Art therapy (2nd ed., p. 2014). SAGE.

- Hardy, D. C. (2013). Working with loss: An examination of how language can be used to address the issue of loss in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 18(1), 29–37. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2012.707665

- Health and Care Professions Council, (HCPC),. (2013). Standards of Proficiency for Art Therapists. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.hcpc-uk.org/resources/standards/standards-of-proficiency-arts-therapists/

- Hinz, L. D. (2020). Expressive therapies continuum: A framework for using art in therapy (2nd ed., p. xviii). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-48971-4.

- Hogan, S., & Coulter, S. (2014). The introductory guide to Art therapy experiential teaching and learning for students and practitioners. Routledge.

- Holmqvist, G., Roxberg, A., Larsson, I., & Lundqvist-Persson, C. (2019). Expressions of vitality affects and basic affects during art therapy and their meaning for inner change. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2018.1480639

- Kagin, S., & Lusebrink, V. (1978). The expressive therapies continuum. Art Psychotherapy, 5(4), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-9092(78)90031-5

- Kapitan, A., & Kapitan, L. (2023). Language is power: Anti-oppressive, conscious language in art therapy practice. International Journal of Art Therapy, 28(1-2), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2022.2112721

- Kwok, I., Belgrod, R., & Lederman, L. (2022). Communicating scope of practice: An outpatient group Art therapy documentation initiative (communiquer le champ de pratique: Une initiative de documentation sur l’art-thérapie ambulatoire de groupe). Canadian Journal of Art Therapy, 35(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/26907240.2022.2052644

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- McNiff, S. (1998). Arts-based research. Jessica Kingsley.

- Milner, M. (1952). Aspects of symbolism and comprehension of the not-self. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 33(2), 181–195. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Aspects-of-symbolism-in-comprehension-of-the-Milner/0d05e20a99da5fd282e64041c6efdf7b9f2e8037.

- Moon, B. L. (2015). Ethical issues in Art therapy (3rd ed.). Charles C. Thomas Ltd.

- Moon, C. H. (2002). Studio Art therapy: Cultivating the artist identity in the Art therapist. Jessica Kingsley.

- NHS. (2003). Code of practice: Confidentiality. Retrieved April 8 2022, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/200146/Confidentiality_-_NHS_Code_of_Practice.pdf

- Nitsun, M. (1996). The anti-group: Destructive forces in the group and their creative potential. Routledge.

- Schaverien, J. (1992). The revealing image: Analytical art psychotherapy in theory and practice. Routledge.

- Schaverien, J. (2000). The triangular relationship and the aesthetic countertransference in analytical art psychotherapy. In A. Gilroy, & G. McNeilley (Eds.), The changing shape of art therapy: New developments in theory and practice (pp. 55–83). Jessica Kingsley.

- Spaniol, S., & Cattaneo, C. (1994). The power of language in the art therapeutic relationship. Art Therapy, 11(4), 266–270. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.1994.10759100

- Stern, D. (2010). Forms of vitality: Exploring dynamic experience in psychology, the arts, psychotherapy, and development. Oxford University Press.

- Van Lith, T., & Bullock, L. (2018). Do art therapists use vernacular? How art therapists communicate their scope of practice. Art Therapy, 35(4), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2018.1540961 therapists communicate their scope of practice

- Winnicott, D. W. (2005). Playing and reality. Routledge. (Original work published 1971).