ABSTRACT

Background: Paediatric long-term physical health conditions such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis can have a significant impact on the mental health and well-being of children and their families. Arts-based therapies have been shown to have a beneficial effect for this group.

Aims: The aim of the study was to develop an online group art therapy intervention for children with long-term physical health conditions.

Methods: The process of developing the intervention was informed by guidelines for the development of complex interventions and comprised four key stages: (1) an expert development process, (2) formation of a stakeholder group and (3) decision-making team, (4) identification of relevant literature and use of existing theories/a theoretical model.

Results: The GAIN (Group Art Therapy Intervention for communicating Needs of children with long-term conditions) was developed. GAIN comprises a treatment manual, six 90-minute online sessions for children (age 8–11 years) and six 30-minute parent-led home sessions.

Conclusions: Next steps are to evaluate the GAIN in a feasibility study.

Implications for practice/policy/future research: The intervention has potential to benefit children and their families; it offers a psychosocial approach for integration with medical care of paediatric long-term physical health conditions and aligns with NHS England’s focus on supported self-management of healthcare.

Plain-language summary

Paediatric long-term physical health conditions, for example juvenile arthritis, can have a significant impact on the mental health and well-being of children and their families. Children may miss out on daily activities, and families may experience emotional distress. Arts-based therapies have been shown to have some beneficial effects for this group. Arts-based therapies are complex interventions that combine therapeutic approaches with creative activities aimed at promoting creative expression and communication. The aims of this study were to develop an online group art therapy intervention for children with long-term physical health conditions.

The process of developing the intervention is described in this paper. We followed a published framework and guidelines for the development of complex interventions. The development process comprised four non-linear key stages: (1) an expert development process, (2) formation of a stakeholder group, (3) formation of a decision-making team and (4) identification of relevant literature and use of existing theories.

We called the intervention ‘GAIN’ (Group Art Therapy Intervention for communicating Needs of children with long-term conditions). GAIN comprises a treatment manual, six 90-minute online sessions for children (age 8–11 years) and six 30-minute parent-led home sessions.

The next steps in this work are to build on the study findings and evaluate the new GAIN in a well-designed follow-up research study. The GAIN offers an approach that considers psychological factors for children and families alongside their social environment to complement medical approaches in the management of paediatric long-term physical health conditions. The GAIN also aligns with NHS England’s approach of using techniques to support and improve the confidence of people with long-term health conditions to manage aspects of their healthcare.

Introduction

Long-term conditions are defined as health problems requiring a clinical follow-up more than twelve months after the initial episode, and they affect up to 27% of children and young people (Wijlaars, Citation2016). Long-term conditions of any type can have a detrimental impact on parent–child interactions, leading to strained relationships and social isolation (Herzer et al., Citation2009). However, familial involvement in the management of long-term conditions can have a positive impact on patient outcomes for goal setting and adopting positive health behaviours (Martire & Helgeson, Citation2017).

It is becoming more accepted that a biopsychosocial model, rather than a bio-medical model, gives a better understanding of the impact of long-term conditions. Biopsychosocial models are able to consider the impact of people’s health inequality context and factors such as anxiety, depression, exercise, psychological coping, family stress and poverty (Herzer et al., Citation2009; Nijhof et al., Citation2018). In the biopsychosocial treatment of long-term conditions, cognitive behavioural approaches are a current recommended method but may have some limitations, for example only having short-term effects (Hamel, Citation2021; Thabrew et al., Citation2018).

The impact of long-term conditions on children and young people’s mental health and the pressure it puts on family life has been observed by art therapists embedded in paediatric rheumatology clinics in the United Kingdom (UK) (Watts et al., Citation2019). Arts-based approaches with children who have long-term conditions are considered to be age-appropriate and have been shown to have some beneficial effects (Wigham et al., Citation2020).

Long-term conditions in children and young people

Diabetes, asthma and juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) are among the most common long-term conditions in childhood (Smith et al., Citation2015). According to the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, children with long-term physical health conditions are more likely to develop mental health conditions (RCPCH, Citation2020). Anxiety and depression levels in children with JIA are higher than in peers without a diagnosis (Fair, Citation2019). The presence of chronic conditions can result in more severe mental health problems in children; however, there may be barriers to mental health services referrals, and gaps in mental health service provision and pathways for this group have been identified (King et al., Citation2023; Weiland et al., Citation1992).

Anxiety and depression can cause significant problems for children with long-term conditions by complicating treatment and recovery, increasing the likelihood of children and families missing out on participating in daily activities and education, because they want to avoid distress (Fair, Citation2019; Keppeke et al., Citation2018; Runions et al., Citation2020). Children and young people with long-term conditions are also at an increased risk of experiencing stigma, social exclusion and bullying, with lower school attendance due to ill health and medical appointments. Lack of awareness of these issues from school staff can contribute to psychological distress (Runions et al., Citation2020).

The impact on families

Alongside the psychological impact of long-term conditions on children and young people, the family can also be affected. Supporting children and young people with long-term conditions may elicit emotional distress throughout the family and impact a family’s ability to cope with their child’s health condition (Holmes & Deb, Citation2003; Smith et al., Citation2015). Parents and carers can experience guilt, worry, anger, sadness and uncertainty when caring for children and young people with a long-term condition, and this highlights the need for emotional resources to be available for families (Smith et al., Citation2015; Wallander et al., Citation1989).

In order to support parents of children with long-term conditions, Bonner et al. (Citation2006) developed the Parent Experience of Child Illness (PECI) to measure how parents have adapted to their child’s long-term condition. It has been found that the uncertainty of the impact of a child’s long-term condition on daily life affects parental physical and mental health. Recommendations have been made to develop interventions to improve the mental health of both children and parents (Holm et al., Citation2008). Successful interventions should be engaging and accessible and should be designed in consultation with children and young people, parents and practitioners (Moore et al., Citation2019).

Art therapy and long-term conditions

Arts therapies are complex interventions combining activities to facilitate creative expression with psychotherapeutic techniques (Jones et al., Citation2020). Art therapy has been considered to be a developmentally appropriate way to support children and young people with long-term conditions, and as a creative intervention it offers a different experience compared with a medical intervention (Malchiodi, Citation1999). For some children creativity through art can offer alternative opportunities for communication alongside or instead of verbal language (Jayne et al., Citation2021). A systematic review of effectiveness of arts-based approaches to improve mental health for children and young people with long-term physical health conditions reported a number of intervention benefits that require further testing (Wigham et al., Citation2020). Arts-based approaches were associated with improved quality of life, coping behaviours and self-concept, and with reduced anxiety (Wigham et al., Citation2020).

O’Neill and Moss (Citation2015) developed a 12-week community-based art therapy group for adults living with chronic pain associated with long-term conditions. The need for the group arose from pilot projects to facilitate distraction from pain and to support social connectedness, mental health and self-management strategies, and the group demonstrated potential as a replicable model of support. However, the authors have identified the need for a larger-scale study to determine the benefits of art therapy programmes for people with chronic pain associated with long-term conditions.

In the UK, art therapy is provided to some paediatric rheumatology clinics supporting children and young people with many long-term conditions, including JIA (Farrugia, Citation2018). However, a lack of research into the efficacy of art therapy in paediatric settings means that access to art therapy is available inconsistently, often only provided through charitable organisations, and is not part of a standard health intervention (Leith, Citation2018).

Manual-based psychosocial interventions

Manual-based treatment within psychosocial and psychotherapeutic approaches facilitate more rigorous measurement within clinical research trials (Mansfield & Addis, Citation2001a, Citation2001b). There have been significant developments in art psychotherapy research towards detailed manual development which can enable assessing treatment fidelity (Hackett et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). Manuals can be developed to target specific mental health conditions and complex mental health difficulties (Jayne et al., Citation2021, Citation2022).

Some barriers to using manual-based therapies are that few clinicians are aware of manual-based treatments and few have been trained in their use (Mansfield, Citation2001b). Knowledge of manualised treatments can broaden the skillset of therapists and can make supervision more focused (Wilson, Citation1996). While there are some concerns about manual-based treatments, they encourage therapists to think critically about why they do what they do and take greater responsibility for their work (Mansfield, Citation2001b). Additionally, Addis (Citation1997) argued that knowing a treatment is empirically supported can help practitioners to feel optimistic and confident when working with clients with complex issues.

Online art therapy

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, art therapists had practised primarily face-to-face with client(s), the therapist normally sharing the same physical space for the therapy sessions during both individual and group therapy. In the rapid shift to online delivery in 2020, many art therapists in the UK creatively adapted their ways of working online in order to be able to continue supporting their clients remotely.

This global transition to online art therapy practice initially demanded increased effort from therapists in ensuring client safety and adapting practice (Zubala, Citation2020) but has since proven to bring new possibilities for art therapy, particularly in widening access to treatment. Recent research demonstrated benefits of online art therapy intervention for a remote island community in Scotland (Zubala et al., Citation2023), and research is growing in support of positive impacts of online art therapy groups for young people’s well-being (Datlen & Pandolfi, Citation2020; Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., Citation2021; Shaw, Citation2020).

While multiple advantages of online art therapy practice have already established it as an approach likely to remain (Zubala & Hackett, Citation2020), more guidance for art therapists in how to conduct online treatment sessions would increase their confidence and ensure a safe and valuable treatment for their young clients. The aims of this study were to develop a manual-based online Group Art Therapy Intervention for communicating the Needs of children with long-term physical health conditions (GAIN).

Method

The process of developing the intervention was informed by a published framework and guidelines for the development of complex interventions (Skivington et al., Citation2021) (see ). The process was iterative, non-linear and comprised five stages: (1) Plan the development process; (2) formation of a stakeholder group; (3) formation of a decision-making team; (4) identification of relevant literature and existing theories; (5) intervention refinement (Skivington et al., Citation2021). The development process resulted in a working treatment manual and intervention description complying with the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) checklist, a guide and reporting checklist that was developed to improve the completeness of reporting and ultimately the replicability of interventions (Hoffmann et al., Citation2014).

Table 1. GAIN Complex Intervention Development Stages (based upon ‘Framework of actions for intervention development, Skivington et al., Citation2021, p. 41).

1. Plan the development process

Previous work by the research team (PW and SH), who have developed and led art therapy programmes in clinical and NHS settings, provided experience and impetus for an intervention development plan (Hackett et al., Citation2017, Citation2020; Watts et al., Citation2019). The GAIN manual framework was initially developed by two authors (PW and SH) as part of a plan to address the needs of children and young people with chronic health conditions and with a focus on creating a replicable intervention and resource. Funding was sought and obtained to undertake a systematic review of the impact of arts-based therapies on the mental health of children with long-term physical health conditions (Wigham et al., Citation2020). A protocol detailing the process to be undertaken to develop the intervention was awarded funding based upon the use of arts-based approaches, related theories, the potential to have a positive impact on mental health and well-being (Hackett et al., Citation2017, Citation2020; Zubala et al., Citation2023) and stakeholder consultation (O’Cathain et al., Citation2019).

2. Formation of a stakeholder group

The expert development process was informed and overseen by a multi-disciplinary stakeholder group and decision-making team (Skivington et al., Citation2021). The steering group members included a Senior Clinical-Academic Consultant Art Psychotherapist (SH); Clinical-Academic Consultant Paediatric Rheumatologist (SJ); Hospital Arts Programme Manager (KH); Art Therapy Charity CEO (SR); Digital/Online Arts Therapy Expert (AZ); Childrens Hospital Research and Innovations Manager (JA); Doctoral Clinical-Academic Arts Psychotherapist (JB); two Rheumatology Clinical Nurse Specialists (LC/RW) and Intervention Innovator Art Psychotherapist (PW). Additional patient and public involvement (PPI) consultation with children and families was carried out at key stages by members of the group (PW, LC) and fed back into the wider steering group and decision-making team. The GAIN project steering group met on nine occasions between 29 January 2021 and 28 November 2022 to initiate and oversee development activities.

Patient and public involvement (PPI) in the development of psychosocial care can empower people with long-term conditions to better manage their conditions (Vassiliadou et al., Citation2020). In the development of GAIN, early consultation took place with an adult who had had childhood lived experience of a long-term condition and who was actively engaged in supporting children with long-term conditions as a Young People and Families Manager for a UK charity. Early PPI advice informed the shaping of the initial GAIN group structure and highlighted the need for involvement of parents and families. Applying a holistic approach to designing and delivering interventions, that encompasses the expertise of children and families, as well as addressing the common issues of their lived experience, is fundamental in successfully managing long-term conditions and changing behaviour – for example, by increasing the likelihood of sustained use of the self-management/self-care techniques developed during GAIN (Rodrigues, Citation2022; Skivington et al., Citation2021).

3. Formation of a decision-making team

The decision-making team comprised the core research study team and co-authors who acquired the funding and discussed the study and project-managed during online and in-person meetings throughout the duration of the study and subsequent write-up.

4. Identification of relevant literature and existing theories

A systematic literature review on arts-based approaches for children with long-term conditions informed the early stages of intervention development (Wigham et al., Citation2020). The target age group was identified from a service review conducted by the Teapot Trust (Watts, Citation2019) which highlighted that children (n = 99) aged between 8 and 11 years had high uptake for individual and group art therapy. Wagner’s (Citation1998) Chronic Care Model (CCM) focuses on informing and empowering patients to be proactive partners in the self-management of their own long-term conditions through goal setting and working collaboratively with clinicians to improve health outcomes (Findley, Citation2014). The CCM links closely with a reported art therapy approach (Watts & Walsh, Citation2019) where children and young people were actively encouraged to set therapeutic goals and work alongside clinicians to achieve them. In addition, concepts were considered of children as ‘active agents’ in being able to influence their own and others’ healthcare needs (Montreuil & Carnevale, Citation2016) and the inter-related/interdependent relationships between children and adults (Cockburn, Citation2013). Involvement of parents and family members in the intervention was therefore considered important. A study by Byrne et al. (Citation2021) found that parent-led CBT was an effective way for younger children to receive support. Parent education programmes that help parents of children with long-term conditions cope and manage their children’s conditions more effectively are important and help to build on families’ strengths and lead to improvements in self-efficacy (Kieckhefer et al., Citation2014).

5. Intervention refinement

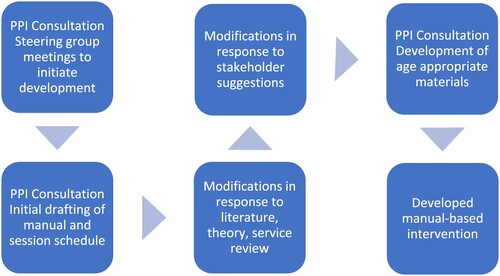

Initial drafting (by PW and SH) of the GAIN manual and session schedule followed in response to literature, theory and service review (Watts et al., Citation2019). The stakeholder group suggested modifications including how to adapt the materials for online use to increase accessibility and reach (Zubala, Citation2020, Citation2021). Digital connectivity for children and families accessing online groups was also considered with mitigations against digital exclusion (Holmes & Burgess, Citation2022). Age-appropriate resources (for 8–11-year-olds), such as worksheets and graphics, were developed. Delivery of groups within six sessions were considered by the steering group as being more likely to maximise group attendance by children within school term time, and home session resources were included with the aim of enhancing parental engagement. The GAIN manual and resources were refined through a process of iterative design informed by PPI consultation at key stages (see ).

All resources were adapted to a child-friendly format for online use by a Digital Consultant working under instruction from the GAIN steering group and decision-making team. Guidance for parents was also created and added to a bespoke online platform which included videos, information sheets and the group resources. Further PPI consultation on initial GAIN manual resources took place with a young person with a long-term condition, and their parent, who had previously received one-to-one art therapy. Feedback focused on how user-friendly and accessible the resources were and further suggestions for improvement and utility; changes were made to the resources in response to the suggestions.

Visual images were created, and the materials were adapted for online use to make them more accessible for parents, visually appealing for children and easier to use for art therapists (see ).

Results

Intervention description – Group Art Therapy Intervention for communicating the Needs of children with long-term health conditions (GAIN)

The core aims of GAIN were: (a) to work collaboratively with children and their parents or carers, (b) to acknowledge their expertise in managing their condition and (c) to empower children and their families to set their own goals for the management of their condition (CitationNHSE; Wagner, Citation1998). The overall objective was to support group members to take age-appropriate responsibility for their health and well-being and communicate their needs clearly (increased agency and self-advocacy) through using creative methods (Jones, Citation2021). Parents are also viewed as experts by experience in their child’s condition, often managing this daily by monitoring symptoms, administering medication, navigating medical appointments and offering emotional support and reassurance (Bogetz et al., Citation2021; Findley, Citation2014; Martire & Helgeson, Citation2017).

The GAIN manual prescribes that art therapists should use a semi-directive/semi-structured approach with set themes and activities (see ). GAIN Therapists (in the UK) are Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) registered Art Psychotherapists who have received training in use of the GAIN manual and ongoing supervision. This ensures that groups offered by different art therapists in different settings have consistency, and children are offered a set of tools, informed by a chronic care model (CCM) (Wagner, Citation1998), that can assist with continued management of their condition after the group has ended.

Table 2. GAIN session schedule.

GAIN consists of six 90-minute online group sessions for children (age 8–11 years) and six 30-minute parent-led home sessions to complete resource worksheets with their children that are linked to weekly themes in the online group. To participate, group members require access to the digital online meeting via a phone/tablet/laptop/PC and art materials for their own use. Art materials and online and printable resources can be sent to group members in advance.

The online group session schedule (see ) includes the following sessions: 1. Getting to know each other; 2. Celebrating me; 3. Taking care of my health; 4. Honest Conversations; 5. Taking care of my feelings; 6. Stepping into my best future. Home parent-led sessions align with online group sessions to support preparation for group activities and increase family involvement. Home sessions worksheet resources include the following topics: 1. Celebrating me; 2. Understanding my needs; 3. Communication and conversations; 4. Taking part in things; 5. Taking part in things/my future goals; 6. My future goals in action.

The therapist leads the structure of the GAIN online sessions including a welcome, group introductions and introductory activity, reviewing group rules, introducing the session schedule themed activity, free art-making time, reflection and review, and preparations for using the home resources before ending each session. Groups may also include a break for children and an online breakout space.

Discussion

This paper details the development of GAIN (Group Art Therapy Intervention for communicating Needs of children with long-term conditions), an online group treatment manual. The intervention, its theoretical underpinnings, methods of delivery and the key components of the group intervention are outlined and discussed. GAIN has been developed as a targeted intervention for children aged 8–11 years who have lived experience of a long-term physical health condition and their parents and carers. Supporting the management of long-term conditions in children requires a biopsychosocial and systemic approach that considers the needs of the child and their family (Smith et al., Citation2015). To effectively address the challenges they face, interventions need to be designed and implemented with children, young people and parents’ and carers’ unique needs in mind (Rodrigues, Citation2022). To build upon this project and demonstrate that arts-based approaches are helpful, increased quality of research is required.

Strengths and limitations

There is no single internationally recognised standardised approach to the development of complex psychosocial interventions. However, guidance was followed from the framework for development and evaluation of complex interventions (Skivington et al., Citation2021) to best inform a process for the design and content of the GAIN manual, and this is a study strength. All activities reported here have been conducted within the time, capacity and resources available to the development team (Skivington et al., Citation2021). A strength of the study is applying and transferring knowledge acquired during previous art therapy intervention development by the research team to a new context and clinical population – paediatric rheumatology in the NHS in England. A limitation of this study is that an evaluation of implementation of GAIN is not presented.

Implications for policy and further research

It is vital to investigate any positive improvements in the mental health of children and ensure that improvements are personal and meaningful to children and their families, and more broadly to see improvements in their well-being and quality of life. Following GAIN development, future work should be carried out for ‘real-world’/‘proof-of-concept’ testing of the GAIN manual. There are several critical areas that require further examination, one of which is the acceptability of the programme to children, young people and their parents or carers.

The next stage of this work would be to evaluate implementation of the art therapy intervention in a clinical setting using a feasibility study design. A service evaluation has been completed which collected qualitative and quantitative data and assessed acceptability; this work will inform a future feasibility study and is in write-up for publication. Future research should include an economic evaluation, for example to explore if there are any changes in mental health service referrals/use after the art therapy intervention (Skivington et al., Citation2021).

GAIN has potential and offers a psychosocial approach for integration into the current methods of management of paediatric long-term physical health conditions. GAIN aligns with NHS England’s approach of supported self-management where interventions are implemented to increase the confidence, skills and knowledge of individuals with long-term conditions to self-manage aspects of their healthcare (CitationNHSE).

Conclusion

The GAIN art therapy manual aims to support and enhance post-intervention self-management for families where there is a child with a long-term condition and for the child themselves to adopt age-appropriate strategies for the management of their own condition, reducing the need for ongoing therapeutic support. Bespoke self-management resources may reduce barriers for families implementing self-management and improve outcomes for those with long-term conditions (Fiallo-Scharer et al., Citation2019). It is also hoped that the GAIN manual will be available in the future for clinicians wishing to provide art therapy to children and young people with long-term conditions, following further testing.

Author contributions

PW, SH and SJ jointly contributed to conceptualisation and methodology. PW prepared the original draft manuscript with additional contributions by AZ, AI, KJ and SW. Supervision and oversight was by SH; funding acquisition SH and SJ. All authors contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the research participants. We would like to thank children and families from the Teapot Trust, CEO Sarah Randell, Art Psychotherapist Megan Keane and Grants Manger Louise Downing for supporting this project. We are grateful to members of our advisory group, Newcastle Hospitals Charity Arts Programme Manager Katie Hickman, Great North Childrens Hospital Research and Innovations Manager Julie Anderson, Rheumatology Clinical Nurse Specialists Lucy Craig and Ruth Wylie. We would like to thank Cumbria Northumberland Tyne and Wear Arts Psychotherapist Jane Bourne for online group therapy advice and Northern Ideas Digital Consultant Kacper Łyszkiewicz. Dr Simon Hackett is supported by funding from Health Education England (HEE)/NHS England and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Integrated Clinical Academic (ICA) programme Senior Clinical Lectureship Award. Dr Sarah Wigham is supported by an NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (Northeast and North Cumbria) Mental Health Fellowship and holds an NIHR Three Research Schools Mental Health Programme Fellowship (award number MH054). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Patricia Watts

Dr Patricia Watts is an Arts Psychotherapist.

Ania Zubala

Dr Ania Zubala is a Digital/Online Arts Therapy Expert.

Arman Iranpour

Arman Iranpour is an NHS researcher.

Kelly Jayne

Dr Kelly Jayne is an Art Psychotherapy Higher Degree Apprenticeship Course Leader & Senior Lecturer.

Sharmila Jandial

Dr Sharmila Jandial is a Consultant Paediatric Rheumatologist.

Sarah Wigham

Dr Sarah Wigham is a Senior Research Associate and NIHR Fellow.

Simon Hackett

Dr Simon Hackett is a Consultant Arts Psychotherapist, Senior Lecturer in Mental Health and NIHR Advanced Clinical Academic Fellow.

References

- Addis, M. E. (1997). Evaluating the treatment manual as a means of disseminating empirically validated psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1997.tb00094.x

- Bogetz, J. F., Trowbridge, A., Lewis, H., Shipman, K. J., Jonas, D., Hauer, J., & Rosenberg, A. R. (2021). Parents are the experts: A qualitative study of the experiences of parents of children with severe neurological impairment during decision-making. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(6), 1117–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.011

- Bonner, M. J., Hardy, K. K., Guill, A. B., McLaughlin, C., Schweitzer, H., & Carter, K. (2006). Development and validation of the parent experience of child illness. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31(3), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj034

- Byrne, G., Connon, G., Martin, E., McHugh, S., & Power, L. (2021). Evaluation of a parent-led cognitive behaviour therapy programme in routine clinical practice: A controlled trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 60(4), 486–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12309

- Cockburn, T. (2013). Rethinking children’s citizenship. Studies in childhood and youth.Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137292070_1

- Datlen, G. W., & Pandolfi, C. (2020). Developing an online art therapy group for learning disabled young adults using WhatsApp. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(4), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1845758

- Fair, D. (2019). Depression and anxiety in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Current insights and impact on quality of life. A Systematic Review. Open Access Rheumatol, 11(1), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S174408

- Farrugia, E. E. K. (2018). Art therapy in hospital waiting rooms. Rheumatology, 57(8). https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key273.017

- Fiallo-Scharer, R., Palta, M., Chewning, B. A., Rajamanickam, V., Wysocki, T., Wetterneck, T. B., & Cox, E. D. (2019). Impact of family-centered tailoring of pediatric diabetes self-management resources. Pediatric Diabetes, 20(7), 1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12899

- Findley, P. A. (2014). Social work practice in the chronic care model: Chronic illness and disability care. Journal of Social Work, 14(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017313475381

- Hackett, S. S., Taylor, J. L., Freeston, M., Jahoda, A., McColl, E., Pennington, L., & Kaner, E. (2017). Interpersonal art psychotherapy for the treatment of aggression in people with learning disabilities in secure care: A protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 3(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-017-0186-z

- Hackett, S. S., Zubala, A., Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Chadwick, T., Harrison, T. L., Bourne, J., & Kaner, E. (2020). A randomised controlled feasibility study of interpersonal art psychotherapy for the treatment of aggression in people with intellectual disabilities in secure care. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0545-z

- Hamel, J. (2021). Somatic art therapy: Alleviating pain and trauma through art. Taylor & Francis Group. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Herzer, M., Umfress, K., Aljadeff, G., Ghai, K., & Zakowski, S. G. (2009). Interactions with parents and friends among chronically ill children: Examining social networks. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(6), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c21c82

- Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., & Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Bmj, 348, g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

- Holm, K. E., Patterson, J. M., Rueter, M. A., & Wamboldt, F. (2008). Impact of uncertainty associated with a child’s chronic health condition on parents’ health. Families, Systems, & Health, 26(3), 282–295. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012912

- Holmes, A. M., & Deb, P. (2003). The effect of chronic illness on the psychological health of family members. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 6(1), 13–22.

- Holmes, H., & Burgess, G. (2022). Digital exclusion and poverty in the UK: How structural inequality shapes experiences of getting online. Digital Geography and Society, 3, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diggeo.2022.100041

- Jayne, K., Hackett, S., & Hill, M. (2021). Art psychotherapy for adults who have experienced complex trauma: An international survey. Perspectives on Trauma, 1(2), 33–43.

- Jayne, K. A. (2022). Identification of the contexts and mechanisms of art psychotherapy treatment that supports healing and recovery for adults who have experienced complex trauma: The development of a treatment manual–unification Neuro-informed trauma reconsolidation art psychotherapy (UNTRAP). University of Northumbria at Newcastle (United Kingdom).

- Jones, P. (2021). Child agency and voice in therapy new ways of working in the arts therapies. Routledge. ISBN 9780367861629.

- Jones, P., Cedar, L., Coleman, A., Haythorne, D., Mercieca, D., & Ramsden, E. (2020). Child agency and voice in therapy: New ways of working in the arts therapies. Routledge.

- Keppeke, L. D., Molina, J., Miotto e Silva, V. B., Terreri, M. T., Keppeke, G. D., Schoen, T. H., & Len, C. A. (2018 Dec). Psychological characteristics of caregivers of pediatric patients with chronic rheumatic disease in relation to treatment adherence. Pediatric Rheumatology, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0280-7

- Kieckhefer, G. M., Trahms, C. M., Churchill, S. S., Kratz, L., Uding, N., & Villareale, N. (2014). A randomized clinical trial of the building on family strengths program: An education program for parents of children with chronic health conditions. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(3), 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1273-2

- King, T., Hui, G. C., Muschialli, L., Shafran, R., Ritchie, B., Hargreaves, D. S., & Bennett, S. (2023). Mental health interventions for children and young people with long-term health conditions in children and young people’s mental health services in England. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13591045231216134. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045231216134

- Leith, K. (2018). The challenge to produce evidence-based research on the efficacy of early intervention arts therapy in paediatric rheumatology departments. Rheumatology, 57(8). https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key273.051

- Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Léger-Goodes, T., Mageau, G. A., Taylor, G., Herba, C. M., Chadi, N., & Lefrançois, D. (2021). Online art therapy in elementary schools during COVID-19: Results from a randomized cluster pilot and feasibility study and impact on mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 15(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00367-5

- Malchiodi, C. (1999). Introduction to medical art therapy with children. In C. Malchiodi (Ed.), Medical Art therapy with children (pp. 13–30). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Mansfield, A. K., & Addis, M. E. (2001a). Manual-based psychotherapies in clinical practice part 1: Assets, liabilities, and obstacles to dissemination. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 4, 68–69. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmh.4.3.68

- Mansfield, A. K., & Addis, M. E. (2001b). Manual-based treatment part 2: The advantages of manual-based practice in psychotherapy. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 4(4), 100–101. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmh.4.4.100

- Martire, L. M., & Helgeson, V. S. (2017). Close relationships and the management of chronic illness: Associations and interventions. American Psychologist, 72(6), 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000066

- Montreuil, M., & Carnevale, F. A. (2016). A concept analysis of children’s agency within the health literature. Journal of Child Health Care, 20(4), 503–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493515620914

- Moore, D. A., Nunns, M., Shaw, L., Rogers, M., Walker, E., Ford, T., & Coon, J. T. (2019). Interventions to improve the mental health of children and young people with long-term physical conditions: Linked evidence syntheses. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 23(22), 1–164. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta23220

- NHSE (National Health Service England). Supported self-management. Retrieved February 2024, from https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/supported-self-management/

- Nijhof, L. N., Nap-van der Vlist, M. M., van de Putte, E. M., van Royen-Kerkhof, A., & Nijhof, S. L. (2018). Non-pharmacological options for managing chronic musculoskeletal pain in children with pediatric rheumatic disease: A systematic review. Rheumatology International, 38(11), 2015–2025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4136-8

- O’Cathain, A., Croot, L., Duncan, E., Rousseau, N., Sworn, K., Turner, K. M., & Hoddinott, P. (2019). Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open, 9(8), e029954. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029954

- O’Neill, A., & Moss, H. (2015). A community Art therapy group for adults with chronic pain. Art Therapy, 32(4), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2015.1091642

- RCPCH. (2020). State of child health 2020. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.

- Rodrigues, M. (2022). Impact in the quality of life of parents of children with chronic diseases using psychoeducational interventions – A systematic review with meta-analysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 105(4), 869–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.07.048

- Runions, K. C., Vithiatharan, R., Hancock, K., Lin, A., Brennan-Jones, C. G., Gray, C., & Payne, D. (2020). Chronic health conditions, mental health and the school: A narrative review. Health Education Journal, 79(4), 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896919890898

- Shaw, L. (2020). ‘Don’t look!’ An online art therapy group for adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(4), 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1845757

- Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., & Moore, L. (2021). Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: Gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 25(57), 1–132. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta25570

- Smith, J., Cheater, F., & Bekker, H. (2015). Parents’ experiences of living with a child with a long-term condition: A rapid structured review of the literature. Health Expectations, 18(4), 452–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12040

- Thabrew, H., Stasiak, K., Hetrick, S. E., Donkin, L., Huss, J. H., Highlander, A., & Merry, S. N. (2018). Psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with long-term physical conditions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012488.pub2

- Vassiliadou, I., Tolani, E., Ip, L., Smith, A., & Papachristou Nadal, I. (2020). Patient and public involvement in integrated psychosocial care. Journal of Integrated Care, 28(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICA-06-2019-0027

- Wagner, E. (1998). Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice, 1(1), 2–4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10345255/

- Wallander, J. L., Varni, J. W., Babani, L., Banis, H. T., & Wilcox, K. T. (1989). Family resources as resistance factors for psychological maladjustment in chronically ill and handicapped children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 14(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.157

- Watts, P., Farrugia, E., Davidson, J., & Leith, K. (2019). FRI0726-Hpr does art therapy make a difference in the management of children and young people with rheumatic diseases: A multi-site service review to explore the impact of art therapy in two tertiary Paediatric rheumatology services in Scotland. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 78, 1061–1062. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.7073

- Watts, P., & Walsh, J. (2019). Art therapy and rheumatology: Using a collaborative approach to address the emotional needs of a child with Marfan syndrome. Rheumatology, 58(Supplement 4), October 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez416.008

- Weiland, S. K., Pless, I. B., & Roghmann, K. J. (1992). Chronic illness and mental health problems in pediatric practice: Results from a survey of primary care providers. Pediatrics, 89(3), 445–449. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1741220/

- Wigham, S., Watts, P., Zubala, A., Jandial, S., Bourne, J., & Hackett, S. (2020). Using arts-based therapies to improve mental health for children and young people with physical health long-term conditions: A systematic review of effectiveness. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1771. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01771

- Wijlaars, L. G. (2016). Chronic conditions in children and young people: Learning from administrative data. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 101(10), 881–885. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-310716

- Wilson, G. T. (1996). Manual-based treatments: The clinical application of research findings. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(4), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(95)00084-4

- Zubala, A., & Hackett, S. (2020). Online art therapy practice and client safety: A UK-wide survey in times of COVID-19. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(4), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1845221

- Zubala, A., Kennell, N., & Hackett, S. (2021). Art therapy in the digital world: An integrative review of current practice and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 595536. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.600070

- Zubala, A., Kennell, N., MacInnes, C., MacInnes, M., & Malcolm, M. (2023). Online art therapy pilot in the Western Isles of Scotland: A feasibility and acceptability study of a novel service in a rural community. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1193445. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1193445

- Zubala, A. H. (2020). Online art therapy practice and client safety: A UK-wide survey in times of COVID-19. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(4), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1845221