ABSTRACT

Becoming a parent is a profound change in one’s life that likely has consequences for political mobilization. This paper focuses on the earliest stages of parenthood, which have rarely been theorized nor empirically investigated. Close to childbirth, there may be substantial demobilizing effects due to hospital stays, immediate childcare responsibilities, parenting distress and the physical burden of pregnancy and childbirth. It is unclear how sizeable these effects are on political demobilization as well as the extent to which they are long-lasting. Based on two individual-level register datasets from Denmark and Finland, we compare the voter turnout among parents in local elections across different dates of childbirth. We find a robust negative short-term effect. We also find that the recovery periods after childbirth are differentiated by gender, illustrating a somewhat stronger demobilizing effect of early stages of motherhood compared to the early stages of fatherhood. There are also some indications that recovery periods after childbirth are slower for women with higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Our study shows that childbearing and childbirth have strong demobilizing, although mostly temporary, implications for electoral participation, even in these strong welfare states.

Introduction

Giving birth to a child is one of the most important life events, but there is a lack of systematic research on how early phases of parenthood are linked to political engagement. By making use of two individual-level register-based datasets from the 2009 Danish and the 2012 Finnish municipal elections, we study the extent to which propensity to vote among expecting and new parents is shaped by pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period. The data are very suitable for this purpose as they contain remarkably large sample sizes, the precise birthdate of all children in relation to the timing of the closest elections, the actual voter turnout which is not self-reported and a wide variety of appropriate controls. These features enable for a fine-grained analysis of the immediate effects of childbirth as well as detecting gender-differentiated and other moderating effects.

Our theoretical approach relies on the expectation that parenthood has dampening effects on voting in the early phases of parenthood, especially around childbirth. The physical and psychological effects of childbirth are thought to have demobilizing consequences as exhaustion, time commitments and extended care for a newborn baby make it difficult, if not impossible, to engage in politics. This expectation stands in contrast to the existing work which instead emphasizes the mobilizing effects of parenthood, where parenthood is seen to be related to new experiences and a rise of stakes in politics. Our point is that parenthood probably has such mobilizing effects in the long run, but that there are important demobilizing effects in the early stages, and that detecting these will help understand the details of the political consequences of parenthood. Furthermore, it is important to study how long-lasting such effects are and when – as time passes from the pregnancy, the birth and the first care for the newborn – the mobilization can be observed.

In what follows, we present the framework for the study of the early phases of parenthood and electoral participation, including our hypotheses. After describing the context regarding the Danish and Finnish municipal elections and parental leave schemes in these countries, we introduce the research design and discuss its advantages and limitations. The empirical section is divided into four parts, focusing on the overall effects, the robustness tests, the gender-specific effects and other interaction effects. Our conclusion is that childbirth has a strong short-term negative effect on turnout. Recovery periods last some months, and we detect an indication of variation between different types of voters, of which most important is that women recover slower than men. In addition, both older and married women as well as women with higher socioeconomic status seem to have a slightly slower recovery rate compared to their counterparts who are younger, unmarried and have lower socioeconomic status though in most cases differences between the groups are insignificant. In sum, our findings suggest that childbearing and childbirth have demobilizing rather than mobilizing consequences for electoral participation even in strong welfare regimes such as Denmark and Finland, where women on average are more active voters than men and where pregnant women and mothers of newborns are supported by state-subsidized social services with regard to pregnancy, childbirth and childcare.

Previous research and hypotheses

Previous research has examined the consequences of having children in general. For instance, there are studies on the effects of having children on women’s participation in the workforce (England Citation2005; Harell et al. Citation2017; Population and Development Review Citation2006), engagement in volunteer work (Kovács Citation2007) and their interactions with relatives and friends (Bost et al. Citation2002). Moreover, some analyses have evaluated the impact of parenthood on a number of political attitudes and behaviors, such as political values and partisanship (Conley and Rauscher Citation2013; Elder and Greene Citation2007; Goodyear-Grant and Bittner Citation2017; Oswald and Powdthavee Citation2010; Urbatsch Citation2014), as well as on political participation (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Citation1995; O’Neill and Gidengil Citation2017; Voorpostel and Coffé Citation2012) and voting in elections (Jennings Citation1979).

When it comes to political consequences of having children particularly with regard to political engagement, two types of models dominate the debate. On the one hand, pregnancy and childbirth are expected to demobilize freshly minted parents politically, particularly mothers. This is reflected in the literature on the effect of having children on women’s political resources (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Citation1995; Jennings Citation1983) and in physiological and psychological research on pregnancy (Galea et al. Citation2008; Mastorakos and Ilias Citation2003). According to this approach, women with young children participate less in politics compared to their counterparts without children or with older children, at least in the US context. Interestingly enough, this tendency is not reflected in interest in politics (Jennings Citation1979; see also O’Neill and Gidengil Citation2017). From the little we know, several causal mechanisms might be at work behind the process of demobilization.

One such deactivating mechanism can be summarized under the concept of “maternal distress” (Emmanuel and St John Citation2010, 2105), which include all sorts of potential inconveniences such as health problems, obstetric risks and weight-related stress, role conflict, lack of parity in the relationship with a spouse or a difficult infant. Like any type of mental or physical health issue, the sense of distress expectedly has negative consequences for political participation (Pacheco and Fletcher Citation2015) as it is linked to lower sense of political efficacy and a reduced capacity to follow politics (Denny and Doyle Citation2007; Schur, Kruse, and Blanck Citation2013, 93). These factors might shape both the ability and motivation to vote.

While the physical discomfort is usually most substantial just before the childbirth, the demobilizing psychological and fatigue-related factors must weigh in most intensely right after the child is born. Both would make the act of voting, including the trip to the polling station and waiting in line, simply less convenient and more costly. Parents experience a lack of time and commitment to the new child makes societal engagement simply difficult. Following childbirth, parents’ social networks might change to offer fewer occasions to discuss politics and to engage in politically relevant actions. Thus, for any or several of these reasons, women with ongoing or recent experiences of being pregnant and giving birth could at least temporarily lose interest in public issues and politics overall, especially just after the child is born. However, it is unclear how long a potential demobilization prevails after childbirth.

On the other hand, parenthood can also have mobilizing effects. Most importantly, having children shapes identity and perspective. Making a commitment to parenthood enables personal growth (Nelson Citation2003, 468–469; see also Barlow and Cairns Citation1997), which could mean a change of perspective when it comes to the stake of elections: the outcomes of political decision-making processes now seem to matter also for an unborn or newly born child and not just for oneself. With growing parental responsibilities, voting may begin to feel more like a civic duty. In a similar fashion, issues such as future-oriented environmental protection, education, childcare, safety and health are likely to play a growing role in the life of a parent and open more direct linkages to policies and stances of political parties and ultimately voting (Micheletti and Stolle Citation2017). Going to the polling booth might thus seem like a meaningful way to influence issues with the increased level of saliency. In short, there is a growth in terms of both normative and expressive considerations of voting (cf. Wass and Blais Citation2017, 466–467). However, most of these effects will play out in the long run, rather than in the immediate aftermath of childbirth.

Clearly, in the long run, children enable parents to increase their propensity to make new friends with other families (for review, see Nelson Citation2003, 473–474). In line with the social logic of politics (Zuckerman Citation2005), multiple ties provide more recruitment opportunities by churches, voluntary associations, informal social networks and political organizations (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995, 16–17). They also mean more occasions for political discussions, together with practical benefits like a companion on a way to the polling station and babysitting while parents are voting. All of these changes may stimulate the desire or pressure to vote. Innovative literature in the field has also paid attention to so-called trickle-up socialization process from older children to their parents. The empirical analyses often suggest a mobilizing effect of parenthood. For instance, a child-initiated discussion about politics, prompted by a civics curriculum or KIDS voting experiment, encourages parents to enhance their civic competence through increased exposure to news media, knowledge gain and opinion formation (McDevitt and Chaffee Citation2002).

In addition, there is an important institutional component to parenthood that could shape turnout. Already during the pregnancy, parents gain experience from various support and care-giving institutions, such as prenatal clinics, antenatal appointments, childbirth classes, midwives (for a review, see Novick Citation2009), birth centers and hospitals (see, e.g. Coyle et al. Citation2001). Thereafter follows childcare contacts as well as contacts with healthcare for children and schools, etc. Parental contacts with these strengthen the links between an individual voter and public institutions and may thus contribute to the understanding that voting shapes how institutions perform and what they deliver. In practice, such contact may either be positive or less satisfactory. In either case, a mobilizing impact can be expected in the long run as experiences grow on the individual. An affirmative perception motivates to vote for parties and candidates that struggle for maintaining current prenatal and parenthood facilities. Correspondingly, a negative perception can reveal the need for society to offer a more extensive or a higher-quality support system. In sum, in the long run, parenthood may boost parents’ self-images as active citizens, enhance their sense of civic duty, the understanding of linkages between institutional experiences and politics, expand social networks and encourage pro-social acts in general.

Overall, while research has found evidence for both demobilizing and mobilizing consequences of having children, the cross-national character and the timing of these forces are not fully determined. If demobilization occurs, when exactly does it set in: during the pregnancy or only after childbirth, and if so, when exactly? Does this process also happen in well-developed welfare states? Related to these research questions, we explore whether demobilization occurs also in Nordic welfare states such as Denmark and Finland where the length of parental leave makes the postnatal period less hectic, potentially leaving at least some room to follow politics. Secondly, we examine the timing of potential demobilization and mobilization in terms of turnout during pregnancy and right after childbirth.

The third contribution of this study is to understand whether mothers and fathers are equally or differently shaped by the early phases of parenthood (c.f. Andersson, Glass, and Simon Citation2014; McLanahan and Adams Citation1987). Noteworthy, some studies claim that fatherhood has generally smaller effects on attitudes and behavior than motherhood. This is often traced to the larger psychological, biological and physical impact of pregnancy on women (e.g. Pancer et al. Citation2000, 258). Mothers usually face deeper consequences of having a child while taking longer breaks from work or experiencing career interruptions more so than fathers. We could thus expect to find a stronger demobilizing effect among women than men.

However, in some political areas, fatherhood seems to have a different impact than motherhood. For instance, fathers usually turn more conservative (compared to non-fathers) and not more liberal like mothers do (Elder and Greene Citation2012). This gender-differentiated effect is expected to occur because, in comparison to fathers, mothers more often consider generous social welfare states preferable in facilitating their efforts to balance work and family. While parenthood has no effect on attitudes among women towards gay marriage, fathers are notably more conservative on the issue compared to non-fathers (Elder and Greene Citation2012). Recent work from Banducci et al. (Citation2016), based on data from the European Social Survey, similarly finds that parenthood can have a polarizing effect on attitudes among men and women. The strongest indication of this was found in countries where there is less state-subsidized support for parental responsibilities, emphasizing the importance of understanding the politics of pregnancy in different contexts. In line with these empirical observations, the gender-related differences in the effect of parenthood should be modest in the two Scandinavian countries under scrutiny in this study.

Finally, the effects of parenthood might not be experienced homogeneously among women from different segments of the electorate. Just like being closely associated with voting propensity in general (for review, see Wass and Blais Citation2017), socioeconomic status may also play an important role in the early parenthood–turnout relationship. We anticipate a number of scenarios when it comes to differentiated effects of pregnancy and childbirth along socioeconomic lines. First, pregnancy and childbirth might strengthen existing inequalities between groups with high and low socioeconomic status. This might be the case if low SES women are more affected by pregnancy and childbirth than higher SES women because handling the parental responsibilities is especially stressful for less privileged mothers (Avison Citation1997; Pacheco and Plutzer Citation2007). Correspondingly, women with lower socioeconomic resources might be disproportionately affected by childbirth, as they have fewer resources to receive help during the first weeks and months of family life; and overall political inequalities might increase. Alternatively, when women give birth, they might become fairly similar to each other in many respects because biological factors might suppress the forces that normally cause inequality. As a result, around childbirth women of all walks of life might vote at similar levels. This might be the case if women with high socioeconomic status are more affected by pregnancy and childbirth than those of lower SES status. A third option is that women with low and high socioeconomic resources are equally shaped by pregnancy and childbirth, keeping the usual difference in voter turnout between these two groups intact.

To conclude, while having children may shape and change the role of parents as citizens and their views of society, it remains unclear exactly in which direction, for how long and under which conditions. This study will contribute to understanding the magnitude and length of a political demobilization effect on turnout directly around childbirth. In addition, we explore a potential gender effect of parenthood that shapes mothers and fathers differently. Finally, this research will examine how socioeconomic variables, including mothers’ age, marital status and SES shape the demobilizing forces of childbirth.

Institutional context

Our study concentrates on voting in two municipal elections taking place in Denmark and Finland. These types of elections are particularly suitable context for the examination of effects related to early phases of parenthood since municipalities are in charge of producing some health and most social services in both countries, including maternity clinics (guidance of the expectant mothers and postpartum check-ups), child clinics and daycare facilities. Municipalities finance these services via subsidies from central government and taxation. Denmark scores highest and Finland third highest among OECD countries in general government expenditures as a percentage of GPD (OECD Citation2013, 75). It is notable that while issues at stake in municipal elections are highly salient for many voters, turnout in these elections remains at a lower level than in national elections. In the elections under scrutiny here, turnout was 65.8% in the 2009 Danish elections and 58.3% in the Finnish 2012 elections, hence providing larger variation in turnout compared to national elections.

According to the state of the world’s mothers 2015 report (Save the Children Citation2015, 60), Finland is the second-best country, while Denmark is ranked on fourth. The comparison is based on lifetime risk of maternal death, under-5-mortality rate, expected number of years of formal schooling, GNI per capita and participation of women in national governments (Save the Children Citation2015, 65–66).

As reflected in mothers’ index ranking, both countries have generous schemes for parental leave. In Denmark, parents are in total given about one year of leave. Maternal leave typically begins four weeks prior to the birth. Fathers take at least two weeks after the birth. Apart from 14 weeks reserved to the mother after the birth, the remaining period can be shared among the parents. On average fathers take about 10% of the total leave. The Finnish parental leave scheme resembles that of Denmark but has less flexibility in the distribution between the parents. While 105 working days are reserved for the mother (including 30–50 days before the birth), the corresponding figure for fathers is 54 days. The remaining 158 days can be shared between the parents.

In general, parents do not spend a long time in the hospital in connection with births. Women giving birth to their first child are normally hospitalized for two to three days, others for one or two days or even less after uncomplicated births. Consequently, hospitalization per se should form a relatively small obstacle for voting in most cases. In addition, although most people vote on the Election Day in both countries, both countries facilitate early voting. In Denmark, advance voting takes place from six weeks to three days prior to elections. The corresponding time span in Finland is from 11 to 5 days prior to elections. Voting outside the polling booth is also possible in both countries. This includes voting in hospitals and various types of housing facilities (only early voting) and home voting due to illness or disability. These measures reduce the costs of voting to future or newly minted parents, such that the demobilizational effects of pregnancy and birth-giving should be small in these two welfare states; in fact, they are probably the minimal effects we can expect across the Western world.

Research design

Data

Our analysis is based on two sets of individual-level register data. The Danish dataset covers information on voter turnout in the 2009 municipal elections. In Denmark, the voter lists are administered by the municipalities and municipal cooperation is thus needed to obtain the lists. We offered all 98 municipalities a chance to participate in the study out of which 44 accepted. This comprises more than 2.3 million voters in total. As the information from these municipalities with few exceptions include all eligible voters, the data do not suffer from individual-level self-selection bias, often characteristic to survey data. Over-reporting is neither a problem since information about voting is derived from official records.

For Denmark, the data from the voter lists were merged in an anonymized form with highly detailed socio-demographic information from Statistics Denmark. The sub-registers available include the so-called birth register which contains the birthdates and parents’ ID for all births in Denmark. From this register, the birth date of the child born closest to the elections was connected to both of its parents. Also, information about the birth order of the child was included.

For Finland, the data from the 2012 Finnish municipal elections were compiled from those electoral wards that used electronic voter registers.Footnote1 These included 211 electoral wards out of 2265, covering 13.6 percent of the electorate. The data, administrated by the Ministry of Justice, were released to Statistics Finland after the elections. In Statistics Finland, the information on whether a person voted or not in these elections was linked to other datasets via personal identification code. For the purpose of this study, Statistics Finland was requested to add information about the birthdate of the child born closest to the 2012 elections. We received this information from parents who had a child one year before the elections to about one year and two months after the elections. The dataset also includes a variable indicating whether other children were born in the family within the time period.

Modeling strategy

We run parallel analyses for the two countries. The empirical approach is based on a comparison of turnout among parents with varying timing of the birth of their child. Our study population consists of individuals who had a child ±1 year from the elections in question. This gives us room to use the turnout rate of both parents before they expect a child as a baseline and to follow similar persons until after the end of the parental leave. For instance, when discussing the effect of having a child on Election Day, we compare turnout rates of parents who had a child on that day to the turnout rate of individuals who were not yet expecting a child (i.e. those who had a child about a year after the elections). The covered period (two years in total) is small enough to limit (though not eliminate) issues concerning unobserved unit heterogeneity which could occur if parents who have children at different times vary on unobserved variables. To state it differently, concentrating on births occurring ±1 year around the elections allows us to study a time period that is essential in terms of the hypothesized mechanisms while not that long that the parents included should be expected to be very different.

The use of such a narrow window (±1 year) should substantially reduce the possibility that individuals under investigation would vary substantially on other factors than the timing of the birth of their child. In order to limit this option further, we include a range of control variables commonly used in the turnout literature and which in principle also could be correlated with the timing of birth. We include the most established background characteristics such as gender, marital status, education, country of origin and citizenship. We also control thoroughly for age (dummies for age at elections in months). This is warranted given that age of a parent could be an obvious confounder as those who have children at a later point in time are likely to be older than those who have children a couple of years before (and thus vote at different rates). We also control for the birth order of the child and whether the parents have other children born close to the election. Finally, we control for geographical differences, for Denmark a municipality fixed effect (a dummy for each municipality), and for Finland the most nuanced unit available, namely a district fixed effect (a dummy for each district).

We include in the main analyses parents of all children born in the relevant period (±1 year around the elections). However, additional analyses were conducted focusing on the difference between the firstborn and later birth orders. While stress relating to becoming a parent does not seem to be lower during the second-time around (e.g. Krieg Citation2007), the established parental identity and previous experiences of parenthood suggest that political implications should be milder among parents who already have children.

A major advantage of the datasets lies in their level of accuracy and precision, combined with large sample sizes. These enable a rather precise estimation of the effects even in a very narrow time span around the birth of a child. The substantial power due to the large datasets also makes it possible to examine the heterogeneity of the effects (i.e. differences in the effects among sub-groups, particularly fathers vs. mothers), especially in Denmark. As already mentioned, the datasets contain detailed background characteristics which can be included as controls in order to take into account possible differences among parents who have children at different time points.

The main disadvantage of the data concerns their cross-sectional character. The results are thus potentially vulnerable to unobserved unit heterogeneity. For instance, a Danish parent who had a child one year before the 2009 elections may be different from parents who had a child one year after the elections. Our strategy is to alleviate this problem by examining a relatively narrow time span as individuals who have marginally different timing in the birth of their child relative to the elections are probably similar. Therefore, we do not expect the problem of unobserved heterogeneity to be as serious as in many other cross-sectional studies, especially given the quality of the control variables. It should be noted that the issues related to unobserved heterogeneity are more relevant for the test of long-term effects than short-term effects (as we do here).

As both countries under scrutiny represent strong welfare states with comprehensive support networks for expecting parents with lengthy maternal and parental leaves, our analysis forms a stringent test of a possible effect of childbirth. That is, rehabilitation after labor should be easier than in some other contexts. The stringent character of our analysis is further emphasized by the inclusion of all childbirths instead of focusing only firstborns.

Results

Overall effects

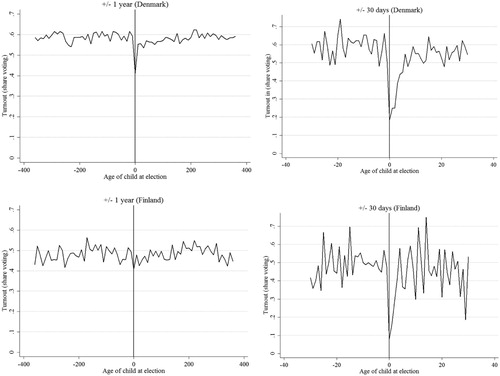

We first analyze the overall influence of pregnancy and childbirth on turnout by looking at turnout among parents before, during and after childbirth. In order to take a first peek at the relationship, shows the bivariate relationship between childbirth and parental turnout in the two elections plotted during a ±1-year interval and a more fine-grained ±1-month period, where numbers on the X-axis denote the age of the child on Election Day. The vertical lines indicate the day of the elections. To the left of this line, we find the turnout among expecting parents, and to the right of that vertical line, we find the turnout among parents with newborns. At the vertical line, we see the turnout when the baby is born on Election Day. Individuals situated on the most left (e.g. −365 to −270 days) are those who are not yet expecting and thus treated as the baseline in subsequent models. This range covers parents who deliver their baby after the elections and thus had not commenced pregnancy at −365 to −270 days, but who will have become pregnant after that.

Figure 1. Turnout as a function of age of a child at the time of the elections in Denmark and Finland.

Note: In the left-hand panels, one data point equals a 10-day increment. In the right-hand panels, one data point equals one day in order to better distinguish individual days close to the elections.

shows a substantial drop in turnout when a child is born around election time, especially in the Danish case. This pattern is consistent with a demobilizing effect of childbirth. However, the period for the decline in turnout is fairly short. In Denmark, turnout is close to 60 percent almost during the entire two-year period covered in the analysis and remains high close up to the delivery. That is parents generally maintain a relatively high turnout level regardless of the closeness of their child’s birthday to the election date. Nevertheless, there is a sharp drop when a child is born close to the election, most of the original turnout rate is regained after not too long. The pattern in Finland is essentially similar. The drop is even shorter in time and only visible in a more detailed graph with ±30 days.

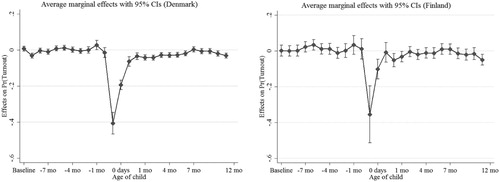

In , we examine whether the observations obtained in bivariate models hold in a more elaborate analysis. Parental turnout is used here as the dependent variable. Age of the child is modeled as dummy variables indicating age in days on Election Day, with negative values indicating days before the delivery and positive numbers days after the delivery. As small changes in time are likely to matter more near childbirth, we create more fine-grained dummies when the age of a child at the time of elections approximates zero. In the figure, the left part of the X-axis indicates parental turnout when their child was born before the elections, whereas the right one indicates turnout figures among parents who had children after the elections. Again, the baseline period is always from −365 to −270 days. The coefficients depicted in are average marginal effects.

Figure 2. Turnout as a function of the age of the child on Election Day (average marginal effects from logistic regressions).

Note: See Table A2 (logit coefficients) and A3 (average marginal effects) of the online appendix for full models. The models control for gender, marital status, education, country of origin, citizenship, birth order, other children born close to elections, age dummies and geographical dummies. Summary statistics can be found in Table A1 of the online appendix.

affirms that there is an evidence of a substantial decline in turnout due to childbirth in both Denmark and Finland, although the effect is somewhat larger in Denmark. Parents delivering a child on the same day that elections were held have a 41-percentage points lower probability of voting in Denmark (see Table A3 of the online appendix for the exact numerical results) and 35 percentage points lower in Finland than those who are about to become pregnant (the base category is −365 to −271 days, i.e. a group not pregnant on Election Day).

Interestingly, turnout does not attenuate substantially before giving birth as even the −7 to −1-day dummy is insignificant in both countries. Also, during the postnatal period, participation increases quickly. Parents with a child born one to seven days before the elections are 19 percentage points (Denmark) and 10 percentage points (Finland) less prone to vote than the base group. For parents with children born 8 to 14 days before the elections were held, the corresponding figures are diminished to six and one percentage points (the Finnish figure is even insignificant). Although turnout continues to increase in Denmark, the effects remain negative in tendency, and at our last point of measurement, it is significantly negative in both countries, possibly because this is the time both parents are working again. The main takeaway point is that parental turnout drops sharply during a short period after the childbirth, but most (though not all) of the drop is regained not long thereafter.

It is worth noting that we did not find any indications of positive effects of early pregnancy and the later postnatal period. Apart from one single coefficient in each country, all coefficients are either insignificant or negative in direction. It is somewhat surprising that turnout remains low even during the later period of parental leave. Thus, it does not seem to be the case that voting among freshly minted parents increases due to an enhanced sense of civic duty or other potential mechanisms during the immediate period after the childbirth. Alternatively, while civic duty may play a role, it is dwarfed by the negative mechanisms. Naturally, our findings do not imply that such parenthood boost in turnout could not occur in the long run, as we present here simply short-run effects.

In additional analyses (reported in the online appendix), we made a range of extensions to our models. First, we tested the influence of the birth order of the child. The psychological effects of parenthood may be stronger for the firstborn child compared to children that follow. To examine this further, we re-calculated the models in with interactions between the birth timing dummies and a dummy indicator for child order (firstborn vs. other birth numbers). Figure A1 in the online appendix shows that the detected pattern is the same for firstborns and subsequent children. Yet, there is some tendency for stronger negative effects among parents having their first child when the child is born close to the elections. This finding is consistent with a larger psychological impact of the firstborn and a tradition of longer hospitalization for the first-time parents. For instance, Danish parents whose child was born on the same day as the elections took place experience a negative effect of 48 percentage points compared to about 34 percentage points for those having children with a later birth order.

We also estimated effects outside the ±1-year range. This is only possible for Denmark since for Finland we only have access to data for a shorter time period. It should also be noted that when increasing the window examined, the concerns of unobserved unit heterogeneity increases as individuals having children several years apart could plausibly differ on other variables. These reservations aside, the analysis indicates that the effects remain at the same negative level as the effects after 12 months (see Figure A2 in the online appendix). Overall, Figure A2 shows that the recovery has almost reached pre-pregnancy levels after one year but there is a slight amount of turnout that is not recovered at all in the period under investigation. This in itself is an important result that will inform the analysis of differences in political behavior more broadly, especially as they come from contexts with generous welfare state support for the parents.

Gender differences

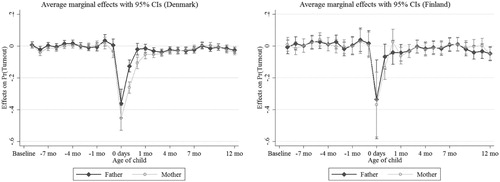

Next, we address the question of whether the effect of pregnancy and childbirth on turnout is gender-differentiated. Any positive or negative effects of childbirth could have a stronger impact on mothers as they are often thought to be more influenced on average by childbearing and delivery, have more contacts with care institutions during the pregnancy and spent more time with a newborn and possibly other parents. In , we test this hypothesis based on logistic regression models identical to those presented in but including interactions between the birth dummies and the gender of a parent. A numerical representation of the effects can be found in the online appendix (Table A4).

Figure 3. Turnout as a function of the age of the child on Election Day interacted with gender (average marginal effects from logistic regressions).

Note: Average marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals shown. The base category for age is –365 days to –271 days. The models control for gender, marital status, education, country of origin, citizenship, birth order, other children born close to elections, age dummies and geographical dummies.

In Denmark, there is a clear tendency of a stronger negative effect of childbirth among mothers as compared to fathers. The negative marginal effect for women is higher than for men until several months after the birth, though only significantly so in the immediate period after the birth (until 1 month, see Table A4 and Figure A3 in the online appendix for differences in the marginal effects between women and men). The demobilizing effect of having a child one to seven days before the elections is around 13 percentage points for fathers, while the corresponding figure is twice as high for mothers (26 percentage points). In the period from 8 to 14 days, men are only two percentage points below their baseline, whereas women are 11 percentage points below their baseline and at 15–30 days the numbers are one percentage points for men and five percentage points for women. Thus, men regain their previous participation rates faster than women. This may reflect the fact that women are physically affected after a delivery or that they simply bear a larger part of the burden of childcare and thus have less time and interest for societal activities, such as gathering political information and voting. Alternatively, women with longer parental leaves lag behind men because re-integration into work contributes to a faster recovery in turnout.

Socioeconomic differences among mothers

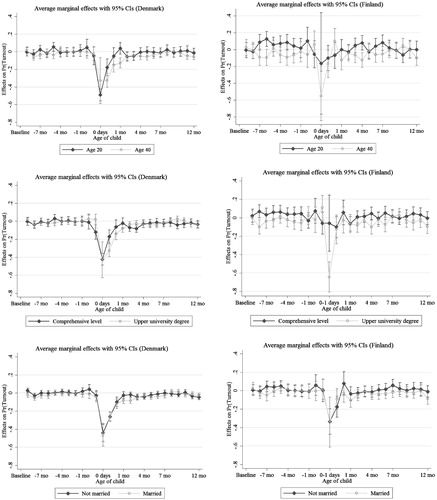

Our research design allows us to investigate three potential scenarios of the differential effects of pregnancy and childbirth across various levels of socioeconomic status. They can lead to increased, diminished or no effects on inequality of voter turnout between SES groups. We re-estimate the model from for the sample of mothers and include an interaction between timing of birth and important correlates of voting. shows the average marginal effect from three models focusing on age, education and marriage specifically (numerical marginal effects can be found in the online appendix in Table A5 for Denmark and Table A6 for Finland while graphical illustration of the difference between the marginal effects for the groups depicted can be found in Figures A4–A6).

Figure 4. Turnout as a function of the age of the child on Election Day interacted with age, education and marital status, respectively (average marginal effects from logistic regressions).

Note: Average marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals. The base category for age is –365 days to –271 days. Note that the category of “0” equals 0 to 1 day for education and marriage in Finland due to too few observations. Control variables for both countries include gender, education (in the education models a continuous version of education is used), country of origin, citizenship, civil status (a dummy variable is used in the marriage models), birth order (firstborn vs. others), other children born close to elections, age dummies (in the age models a continuous version of age is used) and geographical dummies.

There are some tendencies for larger negative marginal effects of childbirth for socioeconomic groups that normally vote in high numbers and who have more socioeconomic resources compared to more disadvantaged groups, implying some degree of convergence in voter turnout when we measure changes in percentage points. In Denmark, the grey line (40-year-olds) is below the black line (20-year-olds) in the first couple of months, though only significantly so in one of the first-time intervals after birth. Similar patterns can be seen for education and to some extent marriage in Denmark, but again only for a few intervals. Especially when a child is born, the high SES groups seem to show more decline in turnout than low SES groups. That is, women who are older, married and have higher education show a somewhat slower recovery of voter turnout over the first months with their newborn than their low SES counterparts. Overall, scenario two seems to be confirmed: women with higher SES resources seem largely more affected by childbirth, thus reducing the differences between mothers of low and high SES backgrounds at the time of childbirth. That is an interesting finding which we will discuss further in the conclusion. In Finland, we do not observe very robust evidence of convergence – though there are some (mainly insignificant) tendencies in the same direction as in Denmark. One reason might be that in Finland it is much more common to vote early (about 45%) compared to Denmark (about 5%). This societal norm and tradition might allow Finns to better address potential constraints of anticipated childbirth on turning out to vote as it is more likely that the expecting parents will vote early in Finland compared to Denmark where early voting is considered very atypical. It might be the case then that widespread use of early voting thus mitigates potential negative effects of childbirth on voting especially in Finland.

Conclusions

This study has investigated the effect of childbirth and early phases of parenthood on turnout. While we cannot detect the exact causal mechanism between the early phases of parenthood and turnout, we can nonetheless provide a precise estimate of the effect size. Overall, the results indicate that both women and men are affected by childbirth at least temporarily, though women more so. In a bigger picture, this dip matters less as it is so short that most individuals who experience childbirth will not be affected, although elections are held rather frequently. The finding that after the initial drop in childbirth turnout increase, but still remain significantly lower compared to prior levels is more important. Even when looking at a longer period (for Denmark), the loss in voter turnout is not completely recovered. Our study thereby shows that even in countries with extended parental leave arrangements and good childcare facilities, we see that the transition to parenthood has a small dampening effect on voter turnout when children are very young. This is an important result which has not been previously shown as clearly as we do here. This negative effect seems much milder in Finland, where the widespread use of early voting seems to prevent big losses in voter turnout around childbirth.

There are also indications that recovery periods after childbirth are slower for women with higher socioeconomic background compared to those with lower socioeconomic background. In that sense, childbirth seems to override the usual political inequalities across varieties of socioeconomic background, at least temporarily. One interpretation is that childbirth has fundamental physical and psychological consequences that trump otherwise common determinants of turnout (i.e. socioeconomic background). While these effects are not large, they should be seen as one of the few circumstances in which the importance of socioeconomic background for turnout becomes insignificant.

Overall, however, while our study shows that pregnancy and childbirth have demobilizing implications for electoral participation, especially for women, we note that they are mostly temporary. After 210 days after childbirth in Denmark and roughly 60 days in Finland, nearly all demobilization has disappeared. This is a result which is most likely due to the various services offered in Nordic welfare states, which provide comparatively strong societal support for the mother and the newborn. It is likely that other contexts will see a slower recovery for the participation of the mother.

How do we interpret the differences between the two countries? In both countries, childbirth lowers turnout significantly, for both women and men. The gender differences are larger in Denmark. In Finland, we do not find significant differences between men and women, and the point estimates for the two gender groups are similar after only a couple of weeks and show altogether small effects of childbirth. Further research can determine which aspects of parental leave policies or health policies might be responsible for this finding. Although both counties offer early voting policies, we have noted here the different norms and cultures around early voting, which might have helped to diminish a larger loss on voter turnout for new parents, particularly mothers in Finland. This insight might need further research to justify potential policy changes.

How generalizable are our results to other contexts? The sharp downturn in turnout around the days of childbirth, as well as the quick recovery, indicates that welfare states managed to deal with substantial physical and psychological burdens of the individual in such life-shaping moments. The demobilization we find can be seen as the minimal baseline, which would be much higher in non-Nordic welfare states.

Lastly, turnout is a somewhat crude measurement of political participation. What we gain in sample size and measurement accuracy by using register data on turnout, we lose in the nuance of political participation. Especially among women in the Nordic countries, turnout is perceived to be the normal; most women vote, simply. The fact that we find that some women take longer to return to vote indicates that they will take even longer to return to other types of political participation. It is probably likely that we would find even stronger demobilizing effects on more demanding forms of political participation, as well as participation that is less bound by social pressure from the immediate surrounding such as participation in demonstrations, or more individualized forms such as consumption of political information).

Online_appendix.docx

Download MS Word (625.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Yosef Bhatti is a PhD in Political Science. His work is published in journals such as British Journal of Political Science, Electoral Studies, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, Public Choice, Social Forces and West European Politics”.

Kasper M. Hansen is Professor of Political Science, University of Copenhagen, Department of Political Science. His research focuses on political behavior: Elections, referendums, voting behavior, turnout, and public opinion. His has published articles in e.g., Political Behavior, British Journal of Political Science, Political Communication, European Journal of Political Research, Party Politics, Electoral Studies, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, Scandinavian Political Studies, Public Administration. He is currently PI for Danish National Election Study and the Danish Turnout project. www.kaspermhansen.eu

Elin Naurin is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg with a wide interest in research on democratic representation and public opinion. She is a Wallenberg Academy Fellow and the PI for the project The Political Effects of Pregnancy, financed by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation as well as for the project Inward or outward: How pregnancy shapes political orientations, financed by the Swedish Research Council. Naurin's work is published in journals such as American Journal of Political Science, British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, Political Studies and West European Politics.

Dietlind Stolle is Professor in Political Science at McGill University and the Director of the Inter-University Centre for the Study of Democratic Citizenship (CSDC). She conducts research and has published on voluntary associations, trust, institutional foundations of social capital, ethnic diversity, and new forms of political participation. Her newest book is “Political Consumerism—Global Responsibility in Action” (2013) by Cambridge University Press (with Michele Micheletti). Stolle is co-PI of the project Inward or outward: How pregnancy shapes political orientations, financed by the Swedish Research Council.

Hanna Wass is an Academy Research Fellow and university lecturer in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Helsinki. She is a work package director in projects “Tackling the Biases in Bubbles in Participation (BIBU)”, funded by the Strategic Research Council, and “Elections Go! (EGO)”, funded by the European Commission. She is a member of the steering committee for the Finnish National Election Study, and the co-convener of the ECPR standing group “Public Opinion and Voting Behavior”. Her work has been published in journals such as Political Research Quarterly, Electoral Studies, the European Journal of Political Research and Political Science Research and Methods. She is a co-author of the book “Health and Political Engagement” (Routledge 2017).

ORCID

Elin Naurin http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7091-994X

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The pilot for the use of electronic voter registers was launched in the parliamentary elections of 2011. Municipalities can decide whether they prefer to use electronic registers and in which electoral wards it is used. Since the number of the electorate included in electronic register was very small in the 2011 elections, we use information from a subsequent election.

References

- Andersson, Matthew A., Jennifer Glass, and Robin W. Simon. 2014. “Users Beware: Variable Effects of Parenthood on Happiness Within and Across International Datasets.” Social Indicators Research 115: 945–961. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0244-8

- Avison, William R. 1997. “Single Motherhood nd Mental Health: Implications For Primary Prevention.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 156 (5): 661–663.

- Banducci, Susan, Laurel Elder, Steven Green, and Daniel Stevens. 2016. “Parenthood and the Polarisation of Political Attitudes in Europe.” European Journal of Political Research. First Published date 11 August 2016.

- Barlow, Constance A., and Kathleen V. Cairns. 1997. “Mothering as a Psychological Experience: A Grounded Theory Exploration.” Canadian Journal of Counselling 31 (3): 232–247.

- Bost, Kelly K., Martha J. Cox, Margaret R. Burchinal, and Chris Payne. 2002. “Structural and Supportive Changes In Couples’ Family And Friendship Networks Across The Transition To Parenthood.” Journal of Marriage and Family 64 (2): 517–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00517.x

- Brady, Henry E., Sidney Verba, and Kay Lehman Schlozman. 1995. “Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation.” American Political Science Review 89 (2): 271–294. doi: 10.2307/2082425

- Conley, Dalton, and Emily Rauscher. 2013. “The Effect of Daughters on Partisanship and Social Attitudes Toward Women.” Sociological Forum 28: 700–718. doi: 10.1111/socf.12055

- Coyle, Karen L., Yvonne Hauck, Patricia Percival, and Linda J. Kristjanson. 2001. “Ongoing Relationships with a Personal Focus: Mothers’ Perceptions of Birth Centre Versus Hospital Care.” Midwifery 17 (3): 171–181. doi: 10.1054/midw.2001.0258

- Denny, Kenny, and Orla Doyle. 2007. “Analysing the Relationship Between Voter Turnout and Health in Ireland.” Irish Medical Journal 100 (8): 56–58.

- Elder, Laurel, and Steven Greene. 2007. “The Myth of ‘Security Moms’ and “NASCAR Dads”: Parenthood, Political Stereotypes, and the 2004 Election.” Social Science Quarterly 88 (1): 1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00443.x

- Elder, Laurel, and Steven Greene. 2012. “The Politics of Parenthood Effects on Issue Attitudes and Candidate Evaluations in 2008.” American Politics Research 40 (3): 419–449. doi: 10.1177/1532673X11400015

- Emmanuel, Elizabeth, and Winsome St John. 2010. “Maternal Distress: A Concept Analysis.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 66 (9): 2014–2015.

- England, Paula. 2005. “Gender Inequality in Labor Markets: The Role of Motherhood and Segregation.” Social Politics 12 (2): 264–288. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxi014

- Galea, Liisa A. M., Kristina A. Uban, Jonathan R. Epp, Susanne Brummelte, Cindy K. Barha, Wendy L. Wilson, Stephanie E. Lieblich, and Jodi L. Pawluski. 2008. “Endocrine Regulation of Cognition and Neuroplasticity: Our Pursuit to Unveil the Complex Interaction Between Hormones, the Brain, and Behaviour.” Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology 62 (4): 247–260. doi: 10.1037/a0014501

- Goodyear-Grant, Elizabeth, and Amanda Bittner. 2017. “The Parent Gap in Political Attitudes: Mothers Versus Others.” In Mothers and Others. The Role of Parenthood in Politics, edited by Melanee Thomas, and Amanda Bittner, 201–225. Vanconver: UBS Press.

- Harell, Allison, Stuart Soroka, Shanto Iyengar, and Valérie Lapointe. 2017. “Attitudes Towards Work, Motherhood, and Parental Leave in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom.” In Mothers and Others. The Role of Parenthood in Politics, edited by Melanee Thomas and Amanda Bittner, 247–267. Vancouver: UBS Press.

- Jennings, M. Kent. 1979. “Another Look at the Life Cycle and Political Participation.” American Journal of Political Science 23 (4): 755–771. doi: 10.2307/2110805

- Jennings, M. Kent. 1983. “Gender Roles and Inequalities in Political Participation: Results from an Eight-Nation Study.” Western Political Quarterly 36 (3): 364–385. doi: 10.2307/448396

- Kovács, Borbála. 2007. “Mothering and Active Citizenship in Romania.” Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai. Serie: Politica LII (1): 107–127.

- Krieg, Dana Balsink. 2007. “Does Motherhood Get Easier the Second-time Around? Examining Parenting Stress and Marital Quality Among Mothers Having Their First or Second Child.” Parenting: Science and Practice 7 (2): 149–175. doi: 10.1080/15295190701306912

- Mastorakos, George, and Ioannis Ilias. 2003. “Maternal and Fetal Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axes During Pregnancy and Postpartum.” Annuals of the New York Academy of Sciences 997: 136–149. doi: 10.1196/annals.1290.016

- McDevitt, Michael, and Steven Chaffee. 2002. “From Top-down to Trickle-up Influence: Revisiting Assumptions About the Family in Political Socialization.” Political Communication 19 (3): 281–301. doi: 10.1080/01957470290055501

- McLanahan, Sara, and Julia Adams. 1987. “Parenthood and Psychological Well-Being.” Annual Review of Sociology 13: 237–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.13.080187.001321

- Micheletti, Michele, and Dietlind Stolle. 2017. “Toying Around with the Future: Sustainability Within Families.” In Mothers and Others. The Role of Parenthood in Politics, edited by Melanee Thomas and Amanda Bittner, 288–312. Vancouver: UBS Press.

- Nelson, Antonia M. 2003. “Transition to Motherhood.” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing 32 (4): 465–477. doi: 10.1177/0884217503255199

- Novick, Gina. 2009. “Women’s Experience of Prenatal Care: An Integrative Review.” Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health 54 (3): 226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.02.003

- OECD. 2013. “Government at a glance 2013.” doi:10.1787/gov_glance-2013-en.

- O’Neill, Brenda, and Elisabeth Gidengil. 2017. “Motherhood’s Role in Shaping Political and Civic Participation.” In Mothers and Others. The Role of Parenthood in Politics, edited by Melanee Thomas and Amanda Bittner, 268–287. Vanconver: UBS Press.

- Oswald, Andrew J., and Nattavudh Powdthavee. 2010. “Daughters and Left-wing Voting.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (2): 213–227. doi: 10.1162/rest.2010.11436

- Pacheco, Julianna, and Jason Fletcher. 2015. “Incorporating Health into Studies of Political Behavior: Evidence for Turnout and Partisanship.” Political Research Quarterly 68: 104–116. doi: 10.1177/1065912914563548

- Pacheco, Julianna, and Eric Plutzer. 2007. “Stay in School, Don’t Become a Parent – Teen Life Transitions and Cumulative Disadvantages for Voter Turnout.” American Politics Research 35 (1): 32–56. doi: 10.1177/1532673X06292817

- Pancer, S. Mark, Michael Pratt, Bruce Hunsberger, and Margo Gallant. 2000. “Thinking Ahead: Complexity of Expectations and the Transition to Parenthood.” Journal of Personality 68 (2): 253–280. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00097

- Population and Development Review. 2006. Policies to Reconcile Labor Force Participation and Childbearing in the European Union 32 (2): 389–393.

- Save the Children. 2015. State of the World’s Mothers 2015. The Urban Disadvantage. Westport, CT: Save the Children.

- Schur, Lisa, Donald Kruse, and Peter Blanck. 2013. People with Disabilities: Sidelined or Mainstreamed? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Urbatsch, Robert. 2014. Families’ Values: How Parents, Siblings, and Children Affect Political Attitudes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Verba, Sydney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Voorpostel, Marieke, and Hilde Coffé. 2012. “Transitions in Partnership and Parental Status, Gender, and Political and Civic Participation.” European Sociological Review 28 (1): 28–42. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcq046

- Wass, Hanna, and André Blais. 2017. “Turnout.” In SAGE Handbook of Electoral Behaviour, edited by Kai Arzhaimer, Jocelyne Evans, and Michael Lewis-Beck, 459–487. London: SAGE.

- Zuckerman, Alan S. 2005. “Returning to the Social Logic of Politics.” In The Social Logic of Politics, Personal Networks as Contexts for Political Behavior, edited by Alan S. Zuckerman, 3–20. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.