ABSTRACT

Democratic responsiveness implies that politicians are expected to be responsive to public demands and needs but also that the public is expected to respond to actual policies and reforms by adjusting their demands. What is often over-looked is that policy-specific knowledge is imperative for public policy responsiveness to send correct signals. By using survey experiments, we tested the effects of policy-specific information on policy preferences for privatization of welfare services in Sweden. In line with the thermostatic model, we expected information on the increase of privatization to show negative correlations with demand for more privatization. The experiments showed that policy preferences changed in most policy areas when policy-specific facts were provided. The negative effects of information about privatization were most pronounced among centre-left respondents, increasing the left-right polarization. The results suggest that policy-specific knowledge can serve as a useful mechanism in order to meet the identified theoretical need to strengthen the causal relationship in theories of public responsiveness. The study adds important knowledge to how we understand public responsiveness, and highlight the need of “reality checks” when analysing policy demands.

Introduction

Democratic responsiveness implies that politicians are expected to be responsive to public demands and needs but also that the public is expected to respond to actual policies and reforms by adjusting their demands and evaluations (Bingham Powell Citation2004; Stimson, Mackuen, and Erikson Citation1995). In order for the public to respond properly to policy, they need at least some knowledge concerning the policy in question. Otherwise, the response, in terms of preferences for more or less policy, will not be based on peoples’ true policy preferences and decision-makers will consequently receive in-correct signals from the public, which may disrupt the democratic process as such. In this article, we seek to expand on this research area by testing the effect of policy-specific knowledge on public responsiveness.

In spite of the centrality of public responsiveness, previous research on public responsiveness to policies are quite heterogeneous, both when it comes to which policy domains are investigated and what kind of effects are found (Larsen Citation2018). However, a substantial body of literature demonstrates that the public respond to policy by adjusting their preferences thermostatically, especially in salient policy domains (e.g. Wlezien Citation1995; Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010; Ellis and Faricy Citation2011; Jennings Citation2009; Bendz Citation2015; Andersson, Bendz, and Stensöta Citation2018). Still, there is need for further research on the conditions under which policy feedback effects on public opinions occur, and the links through which people become aware of policy and policy change (Larsen Citation2018; Neuner, Soroka, and Wlezien Citation2019). A first condition is that policy must be visible in order for people to notice and respond to policy (Soss and Schram Citation2007; Levendusky Citation2011; Andersson, Bendz, and Stensöta Citation2018). Further, theories that include the dynamic interplay of policy and public opinion often make the assumption that citizens are knowledgeable enough to be able to assess policy. At the same time, empirical findings suggest that the ignorance of political matters is widespread (e.g. Delli Carpini and Keeter Citation1996; Oscarsson and Rapeli Citation2018). Even though some earlier findings indicate that sophisticated or highly educated citizens react to policies since they are more likely to possess adequate information, the effect of actual policy knowledge and information on public responsiveness is seldom investigated empirically (e.g. Campbell Citation2012; Larsen Citation2018; Mettler and Soss Citation2004). We aim to contribute to fill this gap by testing if and how public responsiveness is conditioned by information on policy facts, and ask: What happens to policy preferences when people get a “reality-check”? Do people adjust their response to policy change when policy is made explicitly visible through information concerning how policy programs work? If this is the case, it suggests that theories on public responsiveness need to include assumptions on how responsiveness interacts with knowledge of policy.

We present a unique experimental approach of if, and in that case how and under what conditions, policy-specific information affects policy preferences. This is done by providing respondents with information concerning actual policy. In relation to studies using other cues to information about policy, foremost media coverage (e.g. Williams and Schoonvelde Citation2018), our study contributes by making it possible to establish the link between perceptions of policy and policy preferences (see Neuner, Soroka, and Wlezien Citation2019).

The focus for the experiments is privatization of welfare services in Sweden, which is a highly salient and ideologically divided policy area between left and right.Footnote1 First, we argue that this is a critical case for information effects since the left-right cleavage is known to be very strong, meaning that attitudes are often firmly aligned along this dimension. Second, we expect that the ideological division will lead people to respond differently to policy depending on their political orientation (Branham Citation2018; Bendz Citation2015).

The article continues with a discussion of the central theories regarding public responsiveness and policy-specific information effects for opinion formation. We present the Swedish case where privatization of welfare services has developed over the last decades, and where privatization of welfare services is persistently high on the political agenda. The experimental design is presented in detail. The results reveal information effects, and that they are partly in accordance with the thermostatic theory of responsiveness, and that the effects are contingent on ideological predispositions. Our conclusion is that policy-specific information leads to an adjustment of policy preferences, and that information seems to increase the polarization in privatization opinions between left-and right-oriented.Footnote2

Framework

Public responsiveness

Even though most previous research on responsiveness has focused on how political representatives respond to public demands (Esaiasson and Wlezien Citation2017 for an overview), an increasing interest is directed also to if and how the public respond to policies. The reason for this interest is poignantly expressed by Stuart Soroka and Christopher Wlezien in their book “Degrees of Democracy”: “Without public responsiveness to policy, there is little basis for policy responsiveness to public opinion” (Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010, 41). Several studies over the years have shown that institutionalized policies influence target groups in terms of political engagement and mobilization as well as in political trust and empowerment (see for example, Campbell Citation2003; Jæger Citation2009; Kumlin and Rothstein Citation2005; Kumlin and Stadelmann-Steffen Citation2014a; Mettler Citation2005; Soss Citation1999; Ünvera, Bircan, and Nicaise Citation2020).

There is less agreement whether policies also influence attitudes and policy preferences. Even though studies have found some support for the “thermostatic model” (e.g. Wlezien Citation1995, see further below) where individuals are found to adapt their opinions in relation to policy change, there is according to research overviews on policy feedback by Campbell (Citation2012) as well as Larsen (Citation2018) inconclusive evidence that changes in policies result in changes in opinion. Busemeyer et al. (Citation2019) suggest that some of the disagreements and contradictions of previous research is due to conceptual ambiguity, where research, for example, focus on different time perspectives.

The focus of the present study is specific public responsiveness in a short-term perspective, where we use assumptions derived from thermostatic theory. According to this theory, a responsive public will behave like a thermostat and adjust preference for more or less policy in relation to the policy undertaken in various domains. If the public’s preferred level of policy is below the current level, and the decision-makers respond by increasing the level of policy, the public is predicted to respond by expressing an aggregated decrease in preference for more policy. That the direction of feedback is negative is seen as crucial: It means that the public is effective in sending signals to the decision-makers about when the level of policy is close to what the public prefers. If the policy makers then respond accordingly, policy representation is satisfactory (Wlezien Citation1995; Soroka and Wlezien Citation2004, Citation2010). Further, policy that is perceived as salient by the public is in this research demonstrated empirically to be more likely to generate attention and response. For democracy, policy representation is therefore concluded to be better when the domain or policy is considered salient by the public, since they pay more attention and thus signal clear preferences back to policy makers (Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010).

Thermostatic theory has mainly been tested on responses to government spending (budget decisions). Soroka and Wlezien measure the public’s net preference for the level of spending on areas such as defense and welfare and show that over time, the public responds thermostatically: When spending increases, the public responds with a decrease in relative preference for more spending (Soroka and Wlezien Citation2004, Citation2010; Wlezien and Soroka Citation2012, Citation2019; see also Ellis and Faricy Citation2011). There are however numerous policies that are not clearly related to budget, yet still very important to citizens and the quality of political representation (Barabas Citation2011; Thomas Citation2010). Some studies have thus tested the theory on other kinds of policy, e.g. environmental policy (Johnson, Brace, and Arceneaux Citation2005) and immigration policy (Andersson, Bendz, and Stensöta Citation2018; Jennings Citation2009). In the welfare policy area, Bendz (Citation2015) show that public responses to increased privatization of primary health care are in line with the expectations of the thermostatic model, however only in some ideological groups (Bendz Citation2015). The empirical evidence shows that thermostatic theory works as expected in general, also across countries (Jennings Citation2009; Wlezien and Soroka Citation2012) and across policy domains (Wlezien Citation1995); the public also seems to react thermostatically on sub-national government levels (Johnson, Brace, and Arceneaux Citation2005).

Political knowledge and preference formation

A general understanding of how political preferences and opinions are formed argues that we use various cognitive short cuts such as general ideological leaning or party cues rather than information gathering and processing in formation and adaption of policy-specific opinions (Leeper and Slothuus Citation2014; Page and Shapiro Citation1992; Zaller Citation1992). By following ideological and party cues, the individual can form an opinion without necessarily have that much factual knowledge of the policy issue in question. However, this does not deny the importance of political knowledge for adaption or changes in political preferences. According to Zaller’s central understanding of opinion formation, politically more aware individuals are more likely to pick up (“receive”) elite messages. They are also, due to their exposure to multiple and often conflicting messages, less likely to accept messages that are inconsistent with their prior attitudes (i.e. they are more selective). Less aware individuals receive fewer messages, but are more likely to accept them (even if they are conflicting) (Zaller Citation1992). Thus, Zaller argues, there is a positive correlation between political awareness and the consistency and stability of political opinions.

In line with Zaller’s model, several studies have shown that general political knowledge and attentiveness have a certain effect on public responsiveness (see e g Delli Carpini and Keeter Citation1996). Soroka and Wlezien find that people with higher education seem to be more attentive and thus also more responsive to policy change than people less educated (Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010). In spite of this, in relation to policy-specific public responsiveness, general political knowledge and attentiveness might be insufficient. Public responsiveness focuses on change and adaptions of opinions rather than the formation of the opinions in the first place. In order for policy-specific public responsiveness to occur, citizens need to be aware of specific facts concerning particular political issues in order to form and convey preferences (Barabas and Jerit Citation2009; Gilens Citation2001; Kuklinski et al. Citation2000; Stolle and Gidengil Citation2010). If not, it is probably less likely that they will adjust their position once the representatives have responded and changed the policy. The result might be that it is not the “true preferences” (Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010; Wlezien and Soroka Citation2012) of the public that are fed back to the representatives, which in the long run might lead to disappointments and frustrations over lacking policy responsiveness. Martin Gilens conclude his study of effects of policy-specific information on political preferences by stating that: “Despite the central importance of the public’s policy preferences to democratic theory, we remain surprisingly ignorant of the forces that shape them” (Gilens Citation2001, 392).

Policy-specific knowledge

Even though most studies in the field of political knowledge focus on general knowledge, some studies explicitly address policy-specific knowledge, where it is argued that general political knowledge is not sufficient when forming policy preferences (Gilens Citation2001; Barabas and Jerit Citation2009; Stolle and Gidengil Citation2010; Kuklinski et al. Citation2000). As Barabas and Jerit (Citation2009) conclude, many civic activities necessitate information about particular programs, policies and problems and policy-specific knowledge is then more powerful than more general knowledge in shaping political judgements. Empirically, Gilens (Citation2001) have demonstrated that when respondents received information of a particular policy fact, policy preferences changed in several cases, most significantly among respondents with high levels of general political knowledge. In a somewhat related study, Staffan Kumlin found significant effects on evaluations of policy-specific information of outcomes in the welfare sector (Kumlin and Stadelmann-Steffen Citation2014b, 292). Though focused on policy feedback effects on performance evaluation rather than adjustments or changes in opinions, his study supports the notion that policy-specific information can be of importance, at least as additional to general political knowledge and ideological or partisan cues. This leads us over to the question on how citizens receive policy-specific information.

Channels for policy-specific information

Policy-specific information could be achieved through various channels. Often news media are believed to be central in providing policy-specific information. News coverage increases salience, and thereby increases the probability for public response to policy outputs (Neuner, Soroka, and Wlezien Citation2019; de Vreese and Boomgaarden Citation2006; McCombs and Shaw Citation1972; Soroka Citation2003). Barabas and Jerit (Citation2009) demonstrate that media coverage has positive effects on policy-specific knowledge by using a number of “natural experiments” where they isolate effects of policy-specific news in actual media on increased knowledge on these policies (Barabas and Jerit Citation2009). In a recent study, Williams and Schoonvelde (Citation2018) verified with a longitudinal study that news coverage of specific policy output strengthen public responsiveness and form a link between policy outcomes and public preferences (Williams and Schoonvelde Citation2018). In another important study, Neuner, Soroka, and Wlezien (Citation2019), conclude that media coverage on defense spending in the USA facilitates thermostatic public responsiveness. The effects of media coverage on thermostatic responsiveness were found also in the case of Sweden, where Andersson, Bendz, and Stensöta (Citation2018) find that media coverage serves as a link between asylum policy and preferences concerning receiving refugees in to the country.

Another way of gaining policy-specific knowledge is through personal experiences with the policy in question. This is in line with Soss and Schram’s notion of policy proximity as a mechanism between the individual and a certain policy (Citation2007). Lerman and McCabe found that personal experience with a policy (proximity) act as an information channel partly independent of general political knowledge as well as of partisanship (Citation2017). However, they found the effect to be most pronounced among low information voters and voters with low partisanship. In his research overview, Larsen, on the other hand, concludes that “there is no evidence that policy feedback effects are stronger when studied as proximate experiences” (Larsen Citation2018, 17). Finally, a possible channel for policy-specific information is election campaigns. In a study of information effects in the Canadian general election of 1997, Richard Nadeau with colleagues found information effects of the campaign, but mainly among voters with medium or high previous knowledge (Citation2008).

Aim and hypotheses

The focus for our study is to investigate the effects of policy-specific information on public responsiveness in terms of opinion change. The aim is to investigate if, and in that case under what conditions, policy-specific information has effects additional to effects of ideological cues. Our main focus is on thermostatic responses in line with Wlezien and Soroka’s previous work, and the policy area in question is privatization of welfare services in Sweden. Following this work, our study measures change in relative preferences.

The issue of privatization of welfare services has been at the core of the political debate in Sweden for many years. Since the 1990s, the previously dominantly public financed – public provided welfare services have through several political reforms allowed for an increase in private providers, even though all welfare services are still publicly financed. Today, there are numerous private providers in the areas of schooling, health care and elderly care, also in form of large and sometimes international for-profit companies. This development has led the issue of privatization of welfare services in Sweden to be very debated, visible and salient in public debate. Not the least is this the case since in the encompassing Swedish welfare state, most citizens have a quite close contact with several welfare services during their life span. Due to the high visibility and proximity of welfare services in Sweden, we see this as the most likely case for public responsiveness. At the same time, the strong ideological polarization when it comes to opinions on privatization means that added policy-specific information may have limited effects when people state their preferences, as preferences is likely to be firmly grounded in ideological values and thus not so easily affected by additional information.

We expect Swedes in general to have a “preferred level” regarding privatization, and more concrete information on the actual degree and development of privatization to lead to adjustments of opinions. Our first hypothesis is on the main effect and states that policy specific information has effect on opinion (H1).

The main assumption of the thermostatic theory is that the public responds like a thermostat in that when policy increases (decreases), preferences for more policy will decrease (increase). That is, the public responds mainly to changes in policy. The development of privatization differs between welfare policy areas, where for some, it has increased and for some, there has been no change during the 2000s. We use this real-life variation in our experiments, and for two of the included areas, the privately provided services have increased, while for two, the share of privately provided services has been constant. In relation to thermostatic theory, this means that we expect that the respondents will in general adjust their preferences in a negative direction when given information on an increase in privatization, but not when given information describing a constant level of privatization over time (H2).

Previous research on opinion formation states the central importance of information short cuts such as ideology or party- and elite cues. Privatization of welfare services has been in the centre of the Swedish welfare debate for the last decades, and the subject is strongly polarized ideologically between left and right. We expect the variable on ideological orientation to incorporate the absolute preferences, that is whether private elements in the welfare sector are desirable or not. In order to capture the effect of information on the relative preferences, we first hypothesize that the effect of policy specific information is additional to the effect of ideology and awareness (political interest) (H3).

Furthermore, we also expect the response to be conditional on ideological leaning of the respondents. This is based on the thermostatic model of “preferred level”, where the left in this case is negative to privatization whilst the right cherishes it. As privatization of welfare in Sweden have increased quite dramatically during the last decades, the right-oriented, who in general are more positive to privatization, have seen their preferences be met. Even though we do not have a measure of the absolute preferences, it is quite safe to assume that at least some of the right-oriented are satisfied with the current level even though it is possible that those that are most in favour of privatization have not seen their preferred level just yet. Even so, it is reasonable to expect that the right-oriented respond to information concerning privatization with less evident changes in preferences compared to left-oriented, a group who has instead seen a political development less in accordance with their preferences and that is therefore likely to want it stopped or even reversed. Because of this known difference in absolute preferences and considering the increase over time when it comes to privatization, we expect left-oriented to respond with negative feedback, in accordance with the thermostatic theory, since the level of privatization exceeds their preferred level. We expect right-oriented to respond with unchanged preferences, since they are likely to have reached their preferred level of privatization. Accordingly, we hypothesize that among left-leaning respondents the information lead to decreased support for further privatization (H4a), and that right- leaning respondents will not adjust their preferences in relation to the information (H4b). In addition, we expect that people defining themselves very much to the left will be less susceptible to information and consequently not adjust their attitudes, since it is reasonable to believe that their opinions are quite firm and that they might not be able to be that much more negative to privatization.

Following this line of reasoning, an increase in privatization should increase polarization between ideological groups. The assumption relates to the discussion concerning whether subgroups of the population respond in parallel to policy change (Page and Shapiro Citation1992) or if subgroups differ in their responses to a particular policy change (see Enns and Wlezien Citation2011). A study of Branham (Citation2018) show that there are differences along partisan groups on high salience issues with relatively large disagreement among parties in the US case, thereby highlighting the importance of bringing in factors expressing political preferences into analyses on public responsiveness (see also Bendz Citation2015; Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010).

Method

We argue that an experimental approach is the most suitable method to identify the causal effects of information on different kinds of behaviour and attitudes (see e.g. Levendusky Citation2011). By using survey experiments, we are able to investigate the effect of added information by constructing a “tight connection” between information and policy attitudes where the facts are very recent to the respondents when they are asked to state their preferences. In relation to, for example, studies using media as an information source, we can thus more safely assume that respondents take part of the information and also that they actually have the information in mind when expressing their preferences. A possible caveat is that we have no way of knowing if people are already aware of the presented facts. Given the results of research, concerning political knowledge discussed above, it is even so reasonable to assume that people in general are not aware of the details of policies even though they may possess a more general knowledge.

The experimental study includes four welfare areas: Primary school, retirement homes for elder, hospital care and homes for disabled, where private actors are allowed to run the services on equal terms as public actors, in accordance with laws and regulations. The actual degree of privatization differs, where the primary school sector and retirement homes are where we find the largest share of private providers. The welfare domains were chosen with the ambition to vary development over time (during the 2000s), where the share of independent primary schools and private retirement homes have increased during the 2000s, and the share of disabled living in privately run homes as well as the share of private hospital care has been mainly stable during the period.

For the experiments, we used the Citizen Panel, run by the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE) at the University of Gothenburg. The Citizen panel is an online survey of more than 60,000 active respondents around Sweden that volunteer to be part of the panel and regularly get invited to take surveys on a wide range of topics. No payment is made to the panel participants. The majority of participants are self-recruited and the panel is therefore not statistically representative. The self-recruited respondents are mainly used for randomized experimental studies or panel data collections, with focus on change over time within individuals or within specific groups.

For our experiments, we used a sub-sample from the non-probability sample participating in The Citizen Panel 25 carried out between 20 April 2017 and 15 May 2017. The subsample consists of 5000 respondents, randomized into 5 groups (control group, and four groups displayed information concerning different aspects of welfare), where we for this study used the control group and the group receiving information concerning privatization.

Design of experiments

We provided respondents in the experiment group with accurate, factual policy-specific information concerning the level of privatization within primary school, hospital care, retirement homes for the elder and homes for the disabled. Our aim with this design is in other words to isolate the effect of information on preferences for an increase or a decrease of policy measured as attitudes to further privatization of the welfare services.

The respondents were randomized into groups where the experiment group (n = 1074) got all four treatments, in randomized order. The treatments consisted of information of the share of users in privately provided services for each area (schools, hospitals, retirement homes and homes for the disabled).Footnote3 Directly following the information, the respondents were asked about their preferences for further increase or decrease of the possibility to choose private service providers within each of the specified public service areas (nine- point scale, ranging from sharp increase to sharp decrease, with “unchanged” as a middle option and no labels for other options). This question, capturing changes in relative preferences for private alternatives, is the dependent variable in the analyses. The control group (n=940) got the same question but no treatment.

We present two types of analyses, a comparison of means (independent sample t-test) in order to check the basic effects of the experiments, and OLS regressions. The first model is bivariate, with information (experiment variable) as the independent variable. In the second model, we add control variables; left-right orientation and political interest, which we consider as a proxy for awareness. In model 3, an interaction term is added, with left-right orientation and information, in order to draw conclusions on how responses to the information vary depending on ideological leaning.

The variable used for measuring left-right orientation, is an 11-point scale where respondents place themselves from the very left to the very right, with the alternative “neither left nor right” in the middle of the scale. For the analyses, the two values at the endpoints were collapsed, as the number of respondents here are quite small, resulting in a 9-point scale. For the regressions, dummy variables are used. The variable used for measuring awareness is a question concerning political interest, a 4-point scale ranging from very interested, rather interested, rather uninterested, very uninterested. For regressions, dummy variables are used.

Results

The first step of the analysis is to check if the policy-specific information had any effect on the attitudes to increasing the possibilities to choose private service providers within each welfare area. The results are presented in .

Table 1. Effect of information on preferences for further freedom of choice for welfare services.

The value 5 represents the option of keeping things as they are. For homes for the disabled as well as for retirement homes, the mean value for the control group indicates that respondents in general want to increase freedom of choice. For primary schools, the mean value signifies that the control group want to decrease the possibilities to choose slightly while for hospitals, the mean indicates that respondents want to keep things as they are.

When exposed to the policy-specific information, respondents adjust their attitudes in a negative direction, i.e. wanting to decrease the possibilities to choose private service providers, when it comes to primary schools, retirement homes and homes for the disabled. As for hospital care, the difference between groups is not significant, indicating that the information does not make a difference for attitudes. In conclusion, even though the effects are quite small, the information leads to adjustments of attitudes for three welfare services, which mean that H1 finds support for three out of four welfare services.

The hypothesis 2, departing from an expectation that respondents will adjust their preferences in a negative direction when given information on an increase of privatization, finds partial support in that preferences changed in a negative direction for primary schools and retirement homes. However, the expectation that information about an unchanged level of private alternatives should result in no adjustment of preferences is only valid for hospital care while the result for homes for disabled display the same negative effect as for the areas where information described a change.

In the next step of the analysis, we use regressions to further analyse the effect of information (Model 1), add control variables to establish the additive effect of information (Model 2) and test interaction effects (Model 3) ().

Table 2. Effects of information, left-right orientation and political awareness on attitudes to increase/decrease of possibilities to choose private providers.

Model 1 confirms the effects found in , where policy-specific information has a negative effect on preferences concerning possibilities to choose private welfare providers for primary schools, retirement homes and homes for the disabled. Model 2 tests H3, the assumption that the effect of policy specific information is additional to the effect of ideology and awareness (political interest). First, we note that the effect of information is still present when we add ideological orientation and political interest to the model. Despite the expected strong effect of ideological orientation on privatization attitudes, we still see an independent effect of policy-specific information. The conclusion about an additive, relative effect of information is strengthened by the fact that R2 increases slightly when the information variable is added to a model including ideological orientation and political interest (model not shown here).

In , the analysis continues by adding variables expressing the interaction between left-right orientation and information to Model 2.

Table 3. Effects of information, left-right orientation and political awareness on attitudes to increase/decrease of possibilities to choose private providers for primary school, hospital, retirement homes, homes for disabled.

The expectations tested here was that among left-leaning respondents the information should lead to decreased support for further privatization (H4a) and that right-leaning respondents will not adjust their preferences in relation to the information (H4b). First, it should be noted that the general effect of information on attitudes disappears when we add the interaction term, with the exception of homes for the disabled. This means that effects of information are rather found in particular subgroups than among the respondents in general. Our findings reveal that the policy-specific information triggers a response among left-oriented, as they want to decrease the possibilities to choose private service providers, compared to the reference group (neither left nor right). At the same time, respondents leaning to the right do not respond to the information. In line with the hypothesis 4b, we understand this as a satisfaction with the actual privatizations that have taken place in the Swedish welfare sector. To note here is also that respondents in the group most far to the left do not react with adjusting preferences when exposed to information, possibly because they are already very much in favour of decreasing the possibilities to choose private alternatives – in other words, it is reasonable to interpret this as a floor effect. Neither group 4, the left-oriented identifying themselves as close to the middle (neither left nor right) change their preferences significantly in comparison with the reference group 5 when receiving information. Accepting p < .1, the results are consistent across welfare areas, where the groups slightly to the left (2 and 3) respond to the information, with the exception of hospital care, where only group 2 reacts. In conclusion, our hypotheses 4a and 4b both receive support and the information seems to polarize attitudes between left- and right-oriented respondents even further.

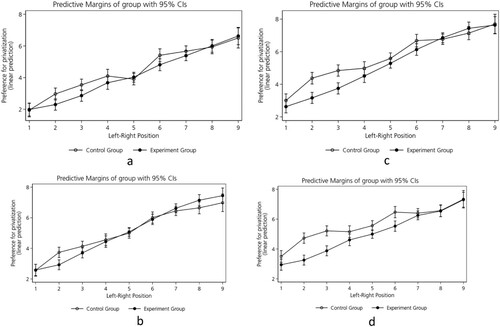

The results from are illustrated more clearly in the (a–d), where predictive margins are displayed.

Figure 1a–d. Interaction effects between left-right orientation and information. Predictive margins (reference category left-right = 5, results from table 3). A: Primary schools B: Hospitals C: Retirement homes D: Homes for disabled.

The predictive margins illustrated in clearly illustrates that the information effects are found mainly among the moderate left-oriented. Privatization attitudes among respondents with the most polarized left-right orientation are not affected by the factual information on privatization, and among respondents in the centre of moderate right effects are clearly limited.

Discussion

Our general conclusion is that peoples’ policy preferences change when they are provided with factual information, even in a case where the left-right cleavage is pronounced, such as the case of privatization of welfare services in Sweden. As a consequence, the signals to decision-makers change. In our study, the general effects indicate that information concerning privatization of welfare services leads to respondents adjusting preferences in a negative direction, meaning that they want to decrease choice of private providers. This is the case both for primary schools and retirement homes, where the share of private service providers has increased during the 2000s. These results support the main assumption of the thermostatic theory: When policy in terms of privatization increases, the public responds by turning down the thermostat and asks for a decrease which indicates that the preferred level of privatization has been reached. However, people also respond with a decrease in relative preferences in the case of homes for the disabled, where the information described stability, not change. This is also where we find the largest mean effect of the information (see ). Tentatively, relating to the theoretical discussion about proximity and saliency (Soss and Schram Citation2007; see also Bendz Citation2015, Citation2017), we suggest that this result may be attributed to the likely lower awareness of homes for the disabled, where few people have personal experiences and where there is also less media attention compared to school, hospital care and retirement homes: The facts about privatization may simply have been more of a surprise for the respondents than the information on the other areas.

A second result is that information seems to polarize opinions in this case. Privatization of welfare services is a question that is characterized by strong left-right cleavages. Left-oriented in general prefer less privatization than right-oriented, they have in other words different preferred levels of policy. When receiving information about an increase of private alternatives, left-oriented responded by expressing a preference to decrease the possibility to choose private providers, while the right-oriented did not react. Interpreted in relation to the thermostatic theory, this means that privatization has exceeded the preferred level of the left-oriented and they, therefore, wanted to turn the thermostat down, while the preferred level for right-oriented has by and large been reached through the recent decades of policy decisions allowing private actors to provide welfare services. As also concluded in Bendz (Citation2015), privatization of welfare services seems to be a case where the assumption of parallel publics is not valid. In forming theoretical assumptions concerning public responsiveness, possible variation between how sub-groups respond should therefore be considered, according to the character of the policy domain (see also Branham Citation2018).

In conclusion, we suggest that policy-specific knowledge can serve as a useful mechanism in order to meet the identified theoretical need to strengthen the causal relationship in theories of public responsiveness. Our study implicates that if people in general are uninformed about the basic facts about a policy, they may send “wrong” signals to decision-makers, which on an aggregated level may direct policy in a direction that is unwanted by the majority. To be noted in this particular study is that the differences in mean values between control group and experiment group are mostly quite small, which means that the information does not necessarily generate an effect that would change the signal to decision-makers in a momentous way. Still, in those areas where the differences are significant, we can see that preferences are adjusted in a certain direction and this indicates that policy-specific information is important to consider in studies on public responsiveness even though the effects can be assumed to vary depending on policy domain and perhaps also institutional and political context. We regard the case of welfare policy in Sweden as a rather hard test for information effects, considering that the policy is salient and also proximate to most people in Sweden. It is possible that the effect of policy-specific information is more evident, and display other response patterns, in policy areas which are less salient and proximate for the public (an assumption that is strengthened by the result concerning homes for the disabled, mentioned above). In recognizing this, we suggest that it would be of value for future research to test the effect of policy-specific information on policy preferences in a broad range of policy areas as well as in other contexts.

Using experiments is a rather unconventional method when investigating the interplay between policy and opinion. Instead of using measures of policy change and public opinion over time, sometimes with media or proximity as a mechanism, we made sure that people included in the study actually had information about the policy change. This meant that we could do more than just assume that people were aware of policy change when they formed their opinions, and thus we could establish a stronger connection between policy and opinion. In relation to thermostatic theory, we suggest that this kind of study can be useful to complement the longitudinal studies of the fluctuations in policy and opinion that is usually done in this research tradition. Even so, there are some caveats with our design. As mentioned above, we had no way of knowing for sure how much the respondents knew about the policies before being exposed for the treatments. Ideally, future studies should include measures of this in order to separate the effect of added information from what was already known by the respondents.

A final remark is that this study has demonstrated the existence of short-term feedback effects. The question remains if this process will also give rise to feedback effects that reinforce a long-term development path (Busemeyer et al. Citation2019). In the case of Swedish welfare policy, such development could imply a turn of the “policy mood” in direction of a more restrictive privatization policy.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Bendz

Anna Bendz is associate professor and senior lecturer at the Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg.

Maria Oskarson

Maria Oskarson is professor and senior lecturer at the Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg. Please get in contact if we should provide some more information.

Notes

1 Concerning attitudes to further privatization of welfare services (index including all four welfare service areas, Cronbach’s alpha .091), 70% of the left-oriented are very or moderately negative to further privatization, while 10% are very or moderately positive. For right-oriented, it is the other way around: 72% are very or moderately positive to allowing more privatization, while 10% are negative.

2 The authors want to thank research assistant Richard Svensson, dep of political science, University of Gothenburg, for excellent help. We also want to thank the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments that greatly contributed to improve the article.

3 The detailed formulation of the treatments is presented in online appendix 1.

References

- Andersson, Dennis, Anna Bendz, and Helena Olofsdotter Stensöta. 2018. “The Limits of a Commitment? Public Responses to Asylum Policy in Sweden Over Time.” Scandinavian Political Studies 41 (3): 307–335.

- Barabas, Jason. 2011. “Book Review on Soroka, Stuart N; Wlezien, C: Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion and Policy. New York: Cambridge University Press.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75 (1): 192–200.

- Barabas, Jason, and Jennifer Jerit. 2009. “Estimating the Causal Effects of Media Coverage on Policy-Specific Knowledge.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (1): 73–89.

- Bendz, Anna. 2015. “Paying Attention to Politics: Public Responsiveness and Welfare Policy Change.” Policy Studies Journal 43 (3): 309–332.

- Bendz, Anna. 2017. “Empowering the People. Public Responses to Welfare Policy Change.” Social Policy & Administration 51 (1): 1–19.

- Bingham Powell, G. 2004. “The Chain of Responsiveness.” Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 91–105.

- Branham, Alexander J. 2018. “Partisan Feedback. Heterogeneity in Opinion Responsiveness.” Public Opinion Quarterly 82 (4): 625–640.

- Busemeyer, Marius R., Aurélien Abrassart, Spyridoula Nezi, and Roula Nezi. 2019. “Beyond Positive and Negative: New Perspectives on Feedback Effects in Public Opinion on the Welfare State.” British Journal of Political Science. Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000534

- Campbell, Andrea Louise. 2003. How Policies Make Citizens: Senior Political Activism and the American Welfare State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Campbell, Andrea Louise. 2012. “Policy Makes Mass Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 15: 333–351.

- de Vreese, Claes, H., and Hajo Boomgaarden. 2006. “News, Political Knowledge and Participation: The Differential Effects of News Media Exposure on Political Knowledge and Participation.” Acta Politica 41: 317–341.

- Delli Carpini, Michael, and Scott Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know About Politics and Why it Matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Ellis, Christopher, and Christopher Faricy. 2011. “Social Policy and Public Opinion: How the Ideological Direction of Spending Influences Public Mood.” The Journal of Politics 73 (4): 1095–1110.

- Enns, Peter K., and Christopher Wlezien, eds. 2011. Who Gets Represented? New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

- Esaiasson, Peter, and Christopher Wlezien. 2017. “Advances in the Study of Democratic Responsiveness: An Introduction.” Comparative Political Studie 50 (6): 699–710.

- Gilens, Martin. 2001. “Political Ignorance and Collective Policy Preferences.” The American Political Science Review 95 (2): 379–396.

- Jæger, Mads Meier. 2009. “United but Divided: Welfare Regimes and the Level and Variance in Public Support for Redistribution.” European Sociological Review 25 (6): 723–737.

- Jennings, Will. 2009. “The Public Thermostat, Political Responsiveness and Error-Correction: Border Control and Asylum in Britain, 1994-2007.” Bristish Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 847–870.

- Johnson, Martin, Paul Brace, and Kevin Arceneaux. 2005. “Public Opinion and Dynamic Representation in the American States: The Case of Environmental Attitudes.” Social Science Quarterly 86 (1): 87–108.

- Kuklinski, James H, Paul J. Quirk, Jennifer Jerit, David Schwieder, and Robert F. Rich 2000. “Misinformation and the Currency of Democratic Citizenship.” The Journal of Politics 62 (3): 790–816.

- Kumlin, Staffan, and Bo Rothstein. 2005. “Making and Breaking Social Capital: The Impact of Welfare-State Institutions.” Comparative Political Studies 38 (4): 339–365.

- Kumlin, Staffan, and Isabelle Stadelmann-Steffen. 2014a. “Citizens, Policy Feedback and European Welfare States.” In How Welfare States Shape the Democratic Public: Policy Feedback, Participation, Voting, and Attitudes, edited by Staffan Kumlin and Isabelle Stadelmann-Steffen, 3–19. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Kumlin, Staffan, and Isabelle Stadelmann-Steffen eds. 2014b. How Welfare States Shape the Democratic Public. Policy Feedback, Participation, Voting and Attitudes. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

- Larsen, Erik Gahner. 2018. “Policy Feedback Effects on Mass Publics: A Quantitative Review.” Policy Studies Journal 47 (2): 372–394.

- Leeper, Thomas J, and Rune Slothuus. 2014. “Political Parties, Motivated Reasoning and Public Opinion Formation.” Advances in Political Psychology 35 (1): 129–156.

- Lerman, Amy, E., and Katherine T. McCabe. 2017. “Personal Experience and Public Opinion: A Theory and Test of Conditional Policy Feedback.” The Journal of Politics 79 (2): 624–641.

- Levendusky, Matthew, S. 2011. “Rethinking the Role of Political Information.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75 (1): 42–64.

- McCombs, Maxwell, and D. L. Shaw. 1972. “The Agenda Setting Function of Mass Media.” Public Opinion Quarterly 36: 176–187.

- Mettler, Suzanne. 2005. “The Creation of the G.I. Bill of Rights of 1944: Melding Social and Participatory Citizenship Ideals.” Journal of Policy History 17 (4): 345–374.

- Mettler, Suzanne, and Joe Soss. 2004. “The Consequences for Public Policy for Democratic Citizenship: Bridging Policy Studies and Mass Politics.” Perspective on Politics 2: 55–73.

- Nadeau, Richard, Neil Nevitte, Elisabeth Gidengil, and André Blais. 2008. “Election Campaigns as Information Campaigns: Who Learns What and Does it Matter?” Political Communication 25 (3): 229–248.

- Neuner, Fabian G., Stuart Soroka, and Christopher Wlezien. 2019. “Mass Media as a Source of Public Responsiveness.” International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (3): 269–292.

- Oscarsson, Henrik, and Lauri Rapeli. 2018. “Citizens and Political Sophistication.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Politics, edited by Russel Dalton. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Page, Benjamin I., and Robert Y. Shapiro. 1992. The Rational Public. Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Soroka, Stuart, N. 2003. “Media, Public Opinion, and Foreign Policy.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 8 (1): 27–48.

- Soroka, Stuart N., and Christopher Wlezien. 2004. “Opinion Representation and Policy Feedback: Canada in Comparative Perspective.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 37 (3): 539–559.

- Soroka, Stuart N., and Christopher Wlezien. 2010. Degrees of Democracy. Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Soss, Joe. 1999. “Lessons of Welfare: Policy Design, Political Learning, and Political Action.” American Political Science Review 93 (2): 363–380.

- Soss, Joe, and Sanford F. Schram. 2007. “A Public Transformed? Welfare Reform as Policy Feedback.” American Political Science Review 101 (1): 111–127.

- Stimson, James A., Michael Mackuen, and Robert S. Erikson. 1995. “Dynamic Representation.” American Political Science Review 89 (3): 543–565.

- Stolle, Dietlind, and Elisabeth Gidengil. 2010. “What Do Women Really Know? A Gendered Analysis of Varieties of Political Knowledge.” Perspectives on Politics 8: 93–109.

- Thomas, Kathrin. 2010. “The Thermostatic Model of Representation Reviewed.” European Political Science 9: 533–543.

- Ünvera, Özgün, Tuba Bircan, and Ides Nicaise. 2020. “Opinion-policy Correspondence in Public Provision and Financing of Childcare in Europe.” International Journal of Educational Research 101: 2–17.

- Williams, Christopher J., and Martijn Schoonvelde. 2018. “It Takes Three: How Mass Media Coverage Conditions Public Responsiveness to Policy Outputs in the United States.” Social Science Quarterly 99 (5): 1627–1636.

- Wlezien, Christopher. 1995. “The Public as Thermostat: Dynamics of Preferences for Spending.” American Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 981–1000.

- Wlezien, Christopher, and Stuart N. Soroka. 2012. “Political Institutions and the Opinion–Policy Link.” West European Politics 35 (6): 1407–1432.

- Wlezien, Christopher, and Stuart Soroka. 2019. “Trends in Public Support for Welfare Spending: How the Economy Matters.” British Journal of Political Science. Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000103.

- Zaller, John. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.