?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article focuses on how party identity can shape policy support or opposition to the controversial issue of legalizing cannabis in Sweden, which is strongly opposed by the public. In a survey experiment (N = 3612), we manipulated if a message that supported or opposed a policy proposal to legalize cannabis was presented by a representative of the own party or an outgroup party. Results showed increased opposition to the proposal when the ingroup party opposed the policy and when the outgroup party endorsed the policy. When the ingroup party endorsed the policy and when the outgroup party opposed the policy, attitudes to the policy were not influenced. We argue that prior attitudes moderate how ingroup- and outgroup party messages are processed and that voters do not blindly follow the party line. Only when the own party presents a position that coincides with the individual’s prior position, are attitudes strengthened and voters follow the party line. Attitudes are also strengthened as a way to increase distance to a disliked outgroup party. When the party cue contradicts prior beliefs (ingroup-endorse; outgroup-oppose), the information is ignored, which allows individuals to retain their view of the party, be it positive or negative.

Introduction

This article aims to understand how party identity influences opposition towards, or support for a controversial policy proposal. Party sympathy is often used as a heuristic in political decision making, and political actors function as cues that play important roles in shaping public opinion (Nicholson Citation2012). While much of this research is based in a US context, party persuasion and source cues have been less explored in systems with greater number of parties, although there are notable exceptions (e. g. Brader and Tucker Citation2012; Torcal, Martini, and Orriols Citation2018). We here focus on the case of Sweden, a proportional representational system with multiple parties.

Our theoretical argument draws on social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986), and we assume that social identification with a party influences how individuals form impressions of both their ingroup (the party they support) and outgroup (the party they oppose), and their members (Bankert, Huddy, and Rosema Citation2017; Huddy, Bankert, and Davies Citation2018; Renström, Bäck, and Schmeisser Citation2020; Torcal, Martini, and Orriols Citation2018). According to social identity theory, when an ingroup party representative expresses opinions on policies, voters should follow their lead (Brader and Tucker Citation2012). Shared expectations about what party supporters should do, so-called injunctive norms, strongly influence how identification with the party shapes behavior (Pickup, Kimbrough, and de Rooij Citation2020). Moreover, when an outgroup party representative expresses an opinion on a policy, it should have the opposite effect, that is, the voter should try distance themselves from the undesired party (Nicholson Citation2012; Huddy, Bankert, and Davies Citation2018). When it comes to controversial policies however, we argue that this pattern may be moderated, because the individual harbors attitudes and feelings related to the issue, which are likely to influence the decision. In line with this argument, research from the US context shows that party loyalty may vary with salience of the issue (Mummolo, Peterson, and Westwood Citation2019). Here we draw on previous research which has shown that prior attitudes influence information processing such that attitudinally congruent information is evaluated as stronger than incongruent information (Taber and Lodge Citation2006). Moreover, citizens may actually shift their opinion away from their party’s position, if they thouroughly process compelling policy information that is supportive of an alternative view (Boudreau and Mackenzie Citation2014, Citation2018).

Hence, voters do not just blindly follow the party’s lead, but are influenced by their prior beliefs and knowledge. According to the dual-process model of attitude change (Eagly and Chaiken Citation1993), heuristics and cues are mainly used when individuals are uninvested in an issue. Therefore it is important to explore how citizens’ react to party cues when the issue at hand is controversial and they are likely to already have a strong opinion on the matter.

We evaluate the potential impact of party cues conducting a survey experiment with about 3,600 respondents in Sweden, focusing on the controversial issue of whether cannabis should be legalized for private use. In the Swedish case, the parties in general take a conservative stance, and the general population is strongly against legalization. Respondents were randomly assigned to receive an endorsing or opposing cue, presented by a representative of their in- or outgroup party, on a policy proposal to legalize private use of cannabis.

Our results show that the message on a controversial proposal increased individuals’ opposition to the proposal in two instances; when the ingroup party opposed the policy and hence was in line with the participant’s view and positive ingroup image, and when the policy was endorsed by the outgoup party, and hence could support a negative view of the outgroup party. However, when the ingroup party endorsed the policy, contradicting the participant’s beliefs, and when the outgroup party opposed the policy, supportive of the participant’s beliefs, the attitudes remained unchanged. Hence, party cues clearly matter for an individual’s attitudes on a controversial issue. However, the results differ from previous research in that we only see a strengthening of the own position, but not a weakening or attitude shift, which indicates that prior attitude position on controversial issues influences how party cues are processed.

Theoretical argument and hypotheses

Social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986) is one of the most influential social psychological theories and has been highly influential within the field of political psychology, explaining various forms of political attitudes and behavior. The basic idea of social identity theory is that individuals form emotional attachments to the groups that they belong to and that groups constitute parts of an individual’s identity. These groups, called ingroups, become an extension of the individual, inevitably leading to biases in efforts to construct positive ingroup views and often also negative outgroup views (Brewer Citation1991). As a social identity, party sympathy therefore affects how impressions of the ingroup and outgroup party and its members are formed (Ditto et al. Citation2018; Iyengar et al. Citation2019; Renström, Bäck, and Schmeisser Citation2020), which most likely influences how messages from these groups are processed.

Hence, intergroup differentiation leads to biases in perceptions of others and the messages that they convey. Most biases in social perception aim to keep a positive ingroup image (or self-image), and the ingroups (and its members) are expected to act in positive ways, which increases positive evaluations and strengthens identification. Simultaneously, negative outgroup behavior functions to differentiate and distance the individual from the (out)group. However, when ingroup members display negative behavior, or when outgroup members display positive behavior, this creates dissonance between the observed and desired view of the groups. To handle such situations, people may simply disregard contradictory information and attribute it temporary circumstances – a phenomenon called the ultimate attribution error (Hewstone Citation1990), which has the goal of making it possible to retain the previous view of the group – be it a positive ingroup view or a negative outgroup view. In line with this, Taber and Lodge (Citation2006) discuss “disconfirmation bias”, which entails the uncritical bolstering of information in line with prior attitudes and the disregard of attitudinally incongruent information.

Put in a political context, a message that comes from an ingroup party should be more persuasive if it is attitudinally congruent with the individual’s own position, compared to an attitudinally incongruent message, which should be left more or less unattended. Conversely, a message from an outgroup party should strengthen the prior attitude if the message is incongruent with this prior attitude, which increases distance to the outgroup and functions to confirm a negative outgroup image. However, if the outgroup presents a message that is congruent with the individual’s prior attitude, they may simply disregard this information.

Hence, as described in the introduction, our theoretical argument draws on previous research which suggests that when an ingroup party representative expresses opinions on policies, voters should follow this kind of party cue (Brader and Tucker Citation2012), and when an outgroup party representative expresses an opinion on a policy, the voter should distance themselves from the undesired party (Nicholson Citation2012). However, when dealing with controversial policies, where the voter is likely to hold strong opinions and feelings related to the issue, such attitudes are likely to influence the voter’s decision whether or not to follow the party cue. Here, the prior attitude will moderate the impact of party cues, and we thus hypothesize that:

(H1) When a party cue is congruent with the own attitude position (opposition to a controversial policy proposal), ingroup party cues will strengthen the attitude position, while outgroup party cues will be left unattended.

(H2) When a party cue contradicts the prior attitude (endorsement of a controversial policy proposal), ingroup party cues will be left unattended, while outgroup party cues will polarize (distance) and strengthen the prior attitude.

Materials and methods

The case: legalization of cannabis for private use in Sweden

Some political issues do not have a clear association to a particular leader or party (compare Walgrave, Lefevere, and Tresch Citation2012), which can be said for the case about legalization of cannabis in Sweden. While private use of Cannabis has become legal in many parts of North America and the public is increasingly positive (Resko et al. Citation2019), it is still a very politically controversial issue in Sweden (Larsson, Citation2019), and no party outspokenly supports such a policy proposal (SVT Citation2017). However, more recently, some parties have suggested a review of the current policies (Reuterskiöld Citation2019), and younger representatives from the centre-liberal or green political parties argue that Sweden should loosen the restrictive policies in favor of a more liberal stance (see for example, Ling Citation2020). Yet, the party (and public) mainstream view is largely against cannabis for private use. According to data drawn from a representative survey performed in 2016, 65% of the respondents were strongly opposed a proposal to legalize cannabis.Footnote1 We thus situate the study in a context where most citizens oppose legalization of cannabis to formulate messages that are congruent or incongruent with this prior stance.

To briefly describe the context, Sweden employs a proportional electoral system, and a multiparty system characterized by a left-wing bloc led by the Social Democrats, a right-wing bloc led by the Moderates, and the populist anti-immigration party, the Sweden Democrats. Data were collected during a period in between two general elections in Sweden, and about one year before the coming general election. It was thus an important period for shaping policy preferences, but it was not a period of the most intense campaigning by the political parties. During the period, the Social Democrats and the Green party were in government.

Experimental design and procedure

We designed a survey experiment to test the hypotheses about the relationship between party cues and party identity on attitude formation to a controversial policy. The design was a 3 (sender group: ingroup/outgroup/anonymous) x 2 (message: endorsing/opposing) between groups factorial design, resulting in 6 conditions. We also added a control condition where participants did not get any information about the proposal, but just rated their attitude position. This functions as a baseline of attitude position against which we compare the other conditions.

The experiment was run at the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORe) Citizen panel at the Society Opinion and Media (SOM) Institute at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden 14 June–14 August 2017, one year before the next general election. 5000 self-recruited members of the panel were invited, and 3612 responded. There were 1291 (35.7%) women, 2262 (62.6%) men, 18 participants (0.5%) stated other gender and 41 (1.1%) did not answer. Mean age was 52 (SD = 14.6). Most participants, 2692 (75%) had some form of higher education (college or university), 89 participants (2.5% had basic schooling), 475 participants (13%) had the equivalent of high school, 301 (8%) had post high school education that was not college/university (usually some sort of vocational training), and finally, 4 participants (0.1%) had not completed basic schooling. Hence, our sample has higher education level, consists of more men and is slightly older compared to the population as a whole. We control for these socio-economic characteristics in the main analyses.Footnote2

In the experiment, respondents were randomly assigned to a policy proposal stance on the legalization of cannabis from a party that they preferred, a party that they disliked, or an anonymous sender. The participant received preferred party treatment based on declared vote intention in a previous wave of the same Internet Campaign Panel. As an indicator of the “least preferred” party we used a proxy, which was the rightwing populist party the Sweden Democrats for all participants except for this party’s own supporters who got the most leftist party, the Left party, as the treatment for their least preferred party. The reason to choose the Sweden Democrats (SD) as a least preferred party for mainstream party supporters was pragmatic, and is based on the fact that previous studies show that SD is the most disliked party among mainstream parties, who have treated this party as a “pariah”, and that it has, up until recently been the least liked party among all parties’ supporters except for the Moderate party supporters (Oscarsson, Citation2017; Sannerstedt Citation2015). In the message, an anonymized representative of the party declared a stance that either endorsed or opposed a policy proposal to legalize cannabis. The message in the party treatments was accompanied by the party’s current graphical logotype (see Appendix for example screenshots of the experimental treatment).

After reading the message, respondents rated on their attitude to the proposal on a 5-point scale, from very positive, somewhat positive, neutral, somewhat negative to very negative toward the policy proposal to legalize cannabis.Footnote3 After the experiment, participants were debriefed about the intentions of the study and participants randomized to the party information conditions were informed that the message that they had received was manipulated.Footnote4

Empirical analyses

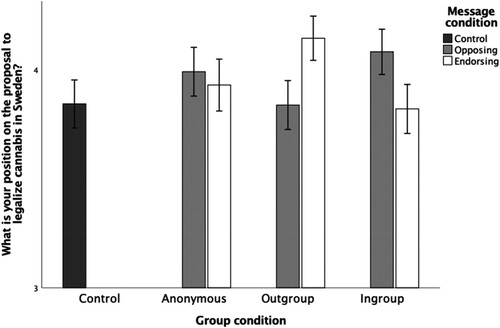

shows means for the different conditions. More detailed information is found in the Appendix. As can be seen, participants were relatively negative in the control condition. The average in this group was a 3.84 on a 5-point scale (higher values indicate more negative attitude). The results for this group also show that a majority of the participants were very negative to the proposal to legalize cannabis – less than 20% of the participants stated that they were very positive or somewhat positive to the suggestion (i. e. 1 or 2 on the scale), and 63% were somewhat negative or very negative (4 or 5 on the scale). The distribution is shown in the Appendix.

Figure 1. Mean attitude ratings on the proposal to legalize cannabis in Sweden across the different experimental conditions. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. Note that the Y-axis has been cut at 3, i.e. representing the opposition side of the scale.

To test our hypotheses that attitude congruent ingroup party cues will strengthen the own position, while attitude congruent outgroup party cues will be left unattended (H1), and that attitude incongruent ingroup party cues will be left unattended, while incongruent outgroup party cues will polarize (strengthen prior attitude) (H2), we ran an anova with policy attitude as dependent variable. We created a new variable where values specified each cell in the design, and hence it had 7 levels (ingroup-endorse; ingroup-oppose; outgroup-endorse; outgrup-oppose; anonymous-endorse; anonymous-oppose; control). We also included age, gender and education level as covariates. The results are shown in .

The results showed a main effect of condition on policy attitude, F(6,3509) = 4.07, p < .0001, = .007. Pairwise follow up comparisons with Bonferroni corrections revealed that both the ingroup-oppose, p = .046, Cohen’s d = 0.19, and the outgroup-endorse, p = .002,Footnote5 Cohen’s d = 0.25, significantly differed to the control group. There was no significant difference between the control condition and the ingroup-endorse and outgroup-oppose conditions. There were no differences between the anonymous condition and the control condition.

The results support our hypotheses that when a party cue is attitudinally congruent, prior attitudes are strengthened when the cue is presented by the ingroup party, but attitudes are unaffected when the cue is presented by the outgroup party. Also, when the party cue is attitudinally incongruent, ingroup party cues are left unattended while outgroup party cues function polarizing and strengthen prior attitude, that is opposition to the policy.

To further evaluate the hypotheses, we made pairwise comparisons between ingroup-endorse and control, and outgroup-oppose and control, and calculated the Bayes factor for these two comparisons. This test allows to compare the likelihood of the data given the null hypothesis with the likelihood of the data given the alternative hypothesis (i. e. no difference between ingroup-endorse/outgroup-oppose conditions and control vs difference between ingroup-endorse/outgroup-oppose conditions and control). As the Bayes factor increases, there is more support in favor of the null hypothesis (no difference) compared to the alternative hypothesis (difference) (Jarosz and Wiley Citation2014). The Bayes factor in this case was 19.62 (ingroup-endorse) and 20.78 (outgroup-oppose), which indicates that the null hypothesis is about 20 times more likely than the alternative hypothesis, and hence strengthens the finding that these messages are left unattended.

To summarize, the analyses show that the cue on a controversial proposal strengthens party supporters’ prior attitudes when the cue originated in the own party and was attitudinally congruent (opposing the proposal), but also when the cue originated in the outgroup party and was attitudinally incongruent. Hence, when the outgroup party endorsed the policy, people reacted with distancing, and strengthening the own prior position. When the cue was either attitudinally incongruent but originated in the ingroup party, or when the cue was attitudinally congruent but originated in the outgroup party, the cue did not affect individuals’ attitude position. Finally, when the cue originated from an anonymous sender, there was no change in attitudes regardless of whether the cue was congruent or incongruent with prior attitudes.

Discussion

The experimental study presented here shows that party sympathy and antipathy matters for how a message is perceived when the issue is controversial, and involvement should be fairly high, depending on party source and policy position of the cue. The results found here show that when party cues are attitudinally congruent, ingroup party cues strengthen the position, while outgroup party cues are left unattended. When party cues are attitudinally incongruent, ingroup party cues are ignored, while outgroup party cues polarize and increase differences to the outgroup party. When the cues come from an anonymous source, the attitudes are unaffected indicating that quality of the argument is less relevant than the party source.

These results are in line with social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986), and the ultimate attribution error (Hewstone Citation1990), which motivates individuals to uphold a positive ingroup image, and a negative outgroup image. They are also in line with directional partizan goals in partizan motivated reasoning literature (e. g. Taber and Lodge Citation2006). However, participants also seem to be motivated and affected by substantive information and accuracy goals since they do not blindly follow the party’s lead (Taber and Lodge Citation2006; Brader and Tucker Citation2012; Boudreau and Mackenzie Citation2014). The effect of party identity on attitude shift is thus likely to be conditioned upon the individual’s motivation – investment in an issue, or just knowledge (Bolsen, Druckman, and Cook Citation2014; Torcal, Martini, and Orriols Citation2018). We here focused on an issue, legalization of cannabis, that is highly controversial, which most (Swedish) citizens have strong negative feelings about, which should function to increase accuracy goals. If participants were solely driven by directional goals, they would have swayed more in the direction of their inparty’s presented position regardless of what the position was. Because the information provided to the participant made clear that it was one representative of the party that either endorsed or opposed the policy, it should have been fairly easy for the participants to ignore unwanted information, by attributing the position advanced to the specific representative and not the party as a whole. This would allow the participant to uphold their view of the party.

Some limitations are worth noting. We used the rightwing populist Sweden Democrats (SD) as the outgroup party for all participants except those identifying with SD. This could affect the outcome since some parties, such as the largest right-wing party, the Moderates, has distanced itself less toward SD in recent years. Future reseach should ideally use more direct measures of the individual’s outgroup party. Moreover, even though the effects found here were significant, they were fairly modest. One reason for this may be that we treated all participants as being opposed to legalization of cannabis, and even though this was true for most participants, a proper pre-treatment attitude measure should provide more reliable results. Nonetheless, since a part of the sample (barely 20% if we draw on our control group results) can be expected to be positive to legalize cannabis, the found effects are likely to be an underestimation of party cue effects.

The outcome of this study is important since it gives further nuance to some recent studies that it is the parties, rather than voters, who take the lead in forming opinions (e.g. Barber and Pope Citation2019). Our study shows that citizens’ interpretations of the party cue is contingent on their prior beliefs about what the party stands for in relation to themselves. Parties can emphasize certain elements of their repertoire to convince their core voters of their competence – however, voters will not follow them blindly. Since voters, at least in the European context, are becoming more volatile, sensitivity toward potentially changing public attitudes in controversial issues is likely to be important for the parties if they want to keep their voters. Hence, it is clearly not always possible for the party to simply sway their supporters’ opinions by making statements and relying on that the supporters will change their opinion to keep a congruent image of the ingroup party – on some issues that may have to use more complex strategies if they want to alter the attitudes of their clientele in a specific direction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hanna Bäck

Hanna Bäck is a Professor of Political Science at Lund University, specializing in comparative politics. Her work mainly focuses on political parties and political behavior.

Annika Fredén

Annika Fredén is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Karlstad University, specializing in voting behavior, experiments, and artificial intelligence in social sciences.

Emma A. Renström

Emma A. Renström is an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Gothenburg. Her research concerns political psychology, especially political polarization and participation.

Notes

1 Data were accessed in collaboration with Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson, University of Gothenburg and the editors of the 2017 SOM antology (Andersson et al. Citation2017). https://snd.gu.se/en/catalogue/study/snd1043

2 Gender was dummy coded as women = 1, men = 0, and education on a 9-graded scale from not completed basic schooling to having a PhD.

3 The scaling of the variable is based on the 2016 National SOM survey. We have treated this variable as interval level in the manuscript but since it contains few scale steps, we also ran additional analyses treating it as ordinal. These are shown in the appendix. Since the results did not differ we present the more intuitive parametric approach.

4 The following information was shown: “The text where a representative from a political party declared a policy position was fictive for this study and does not necessarily represent the view of the party.”

5 There were also significant differences within the ingroup condition between the endorsing and opposing message, p = .02, and between the endorsing and opposing message within the outgroup condition, p = .002. There were also significant differences between the outgroup and ingroup within the opposing message condition, p = .036, and between the outgroup and ingroup within the endorsing condition, p = .001. However, these effects are mainly due to a strengthening in opposition to the policy in the ingroup-endorsing and outgroup-opposing conditions, as they do not differ to the control condition.

References

- Andersson, U., J. Ohlsson, H. Oscarsson, and M. Oskarson, eds. 2017. Larmar och gör sig till. University of Gothenburg, the SOM Institute: Gothenburg.

- Bankert, A., L. Huddy, and M. Rosema. 2017. “Measuring Partisanship as a Social Identity in Multi-Party Systems.” Political Behavior 39 (1): 103–132.

- Barber, M., and J. C. Pope. 2019. “Does Party Trump Ideology? Disentangling Party and Ideology in America.” American Political Science Review 113 (1): 38–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000795.

- Bolsen, T., J. N. Druckman, and F. L. Cook. 2014. “The Influence of Partisan Motivated Reasoning on Public Opinion.” Political Behavior 36 (2): 235–262.

- Boudreau, C., and S. A. Mackenzie. 2014. “Informing the Electorate? How Party Cues and Policy Information Affect Public Opinion About Initiatives.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (1): 48–62.

- Boudreau, C., and S. A. Mackenzie. 2018. “Wanting What Is Fair: How Party Cues and Information About Income Inequality Affect Public Support for Taxes.” The Journal of Politics 80 (2): 367–381.

- Brader, T., and J. A. Tucker. 2012. “Following the Party’s Lead: Party Cues, Policy Opinion, and the Power of Partisanship in Three Multiparty Systems.” Comparative Politics 44 (4): 403–420.

- Brewer, M. B. 1991. “The Social Self: On Being the Same and Different at the Same Time.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17 (5): 475–482.

- Ditto, P. H., B. S. Liu, C. J. Clark, S. P. Wojcik, E. E. Chen, R. H. Grady, Jared B. Celniker, and Joanne F. Zinger. 2018. “At Least Bias is Bipartisan: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Partisan Bias in Liberals and Conservatives.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 14 (2): 273–291.

- Eagly, A. H., and S. Chaiken. 1993. The Psychology of Attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. Fort Worth, TX.

- Hewstone, M. 1990. “The ‘Ultimate Attribution Error’? A Review of the Literature on Intergroup Causal Attribution.” European Journal of Social Psychology 20: 311–335.

- Huddy, L., A. Bankert, and C. L. Davies. 2018. “Expressive Versus Instrumental Partisanship in Multi-Party European Systems.” Political Psychology 39: 173–199.

- Iyengar, S., Y. Lelkes, M. Levendusky, N. Malhotra, and S. J. Westwood. 2019. “The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 22: 129–146.

- Larsson, J. 2019. “Legalize cannabis?.” [Legalisera cannabis?] Svenska Dagbladet, 8 January 2019, retreived from https://www.svd.se/legalisera-cannabis.

- Jarosz, A. F., and J. Wiley. 2014. “What Are the Odds? A Practical Guide to Computing and Reporting Bayes Factors.” The Journal of Problem Solving 7: 2–9.

- Ling, R. 2020. Green Party Representative Wants to Review Cannabis Legalisation Politics. Dagens Nyheter, Accessed April 28, 2020. https://www.dn.se/nyheter/sverige/mp-topp-vill-utreda-avkriminalisering-och-legalisering-av-cannabis/.

- Mummolo, J., E. Peterson, and S. Westwood. 2019. “The Limits of Partisan Loyalty.” Political Behavior, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09576-3.

- Nicholson, S. P. 2012. “Polarizing Cues.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (1): 52–66.

- Oscarsson, H.. 2017. The Swedish party system under change [Det svenska partisystemet i förändring]. In Larmar och gör sig till, edited by U. Andersson, J. Ohlsson, , H. Oscarsson, and M. Oskarson. pp. 411–427. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

- Pickup, M. A., E. O. Kimbrough, and E. A. de Rooij. 2020. “Identity and the Self-Reinforcing Effects of Norm Compliance.” Southern Economic Journal 86 (3): 1222–1240.

- Renström, E. A., H. Bäck, and Y. Schmeisser. 2020. “Vi ogillar olika. Om affektiv polarisering bland svenska väljare.” In Regntunga skyar, edited by U. Andersson, A. Carlander, and P. Öhberg. pp. 427–444. University of Gothenburg. SOM-institute: Gothenburg.

- Resko, Stella, Jennifer Ellis, Theresa J. Early, Kathryn A. Szechy, Brooke Rodriguez, and Elizabeth Agius. 2019. “Understanding Public Attitudes Toward Cannabis Legalization: Qualitative Findings From a Statewide Survey.” Substance Use & Misuse 54 (8): 1247–1259.

- Reuterskiöld, A. 2019. The Last Taboo of Swedish Politics: “Making Me Afraid of Losing My Job” [Politikens sita tabu. Gör mig rädd att förlora jobbet]. Svenska Dagbladet. Accessed April 28, 2020. https://www.svd.se/politikens-sista-tabu-gor-mig-radd-att-forlora-jobbet.

- Sannerstedt, A. 2015. “How Extreme are the Sweden Democrats?” [Hur extrema är Sverigedemokraterna?]. In Fragment, edited by Annika Bergström, Bengt Johansson, Henrik Oscarsson, and Maria Oskarson. pp. 399–414. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

- SVT (Swedish Public Television). 2017. The Swedish Parliamentary Parties’ Attitudes Toward Legalising Cannabis. [Så ställer riksdagspartierna till en legalisering av Cannabis]. Accessed April 28, 2020. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/sa-staller-riksdagspartierna-till-en-legalisering-av-cannabis.

- Taber, C. S., and M. Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 755–769.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1986. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel, 33–37. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Torcal, M., S. Martini, and L. Orriols. 2018. “Deciding About the Unknown: The Effect of Party and Ideological Cues on Forming Opinions About the European Union.” European Union Politics 19 (3): 502–523.

- Walgrave, S., J. Lefevere, and A. Tresch. 2012. “The Associative Dimension of Issue Ownership.” Political Opinion Quarterly 76 (4): 771–782.