ABSTRACT

Support for the populist radical right (PRR) has surged across Europe. Existing studies on female support for the PRR are mostly cross-national in nature and have found that neither social-demographic nor attitudinal differences satisfactorily explain the gender gap in PRR support. Here we focus on the gender gap in support for UKIP and the Brexit Party, two parties that have significantly shaped British politics. Using data covering two European Parliamentary and three General Elections, we show that a gender gap exists in PRR support, but that it varies over time. In line with comparative studies, we find little evidence to suggest that social-demographic or attitudinal differences explain the gender gap in PRR support. Instead, we show that party leadership is crucial. Women in the British electorate hold negative opinions on Nigel Farage and this explains the gender gap in PRR support in Britain.

Introduction

Since the 1980s, researchers have revealed that more men than women support the radical right (Spierings and Zaslove Citation2017). Although the existence of the gender gap “is among the most consistent and universal findings” about PRR parties (Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Citation2018, 369), scholars are unable to agree on its cause. Demand-side explanations in particular, which maintain that the gender gap is driven by men’s embrace of attitudes that align with radical right support, have been upended by studies which show that women hold anti-immigrant and authoritarian attitudes with a similar intensity to men. Further, although the radical right gender gap has been documented throughout Europe, its presence (or absence) in Britain has largely evaded scholarly attention. Therefore, the extent of Britain’s gender gap, and the similarities and differences between men and women PRR supporters, are unclear.

Our article breaks new ground by presenting the first comprehensive overview of the British radical right gender gap via a study of women’s support for the United Kingdom’s two most electorally successful populist radical right (PRR) parties: UKIP and the Brexit Party. Until now, scholars have typically excluded Britain from studies of the radical right gender gap and failed to consider the role of gender in UKIP and Brexit Party support (although see Allen and Goodman Citation2021). This lacuna is significant in light of the role that UKIP and the Brexit party have played in British politics – particularly relating to the EU referendum outcome – and limits our understanding of the women who support these populist radical right parties. Better insight into the gendered nature of support for UKIP and the Brexit Party could also provide a foundation for understanding men’s and women’s endorsement, or rejection, of other PRR parties during a time of rising Euroscepticism.

The paper proceeds as follows. We first discuss the populist and radical right nature of UKIP and the Brexit Party, followed by an overview of the leading explanations for the PRR gender gap. We then detail our data and methods before turning to our analyses. Drawing on data from the online British Election Study Internet Panel (BESIP) across five elections (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2020), we find that the gender gap varies over time and that remarkable similarities exist between men and women radical right voters when it comes to their demographic profiles and political attitudes. Yet, we show that men and women have significant and substantively different views of UKIP and Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage, with women expressing more negative views about him when compared to men. We show that these gender differences in support for Farage are an important explanation for the gender gap in PRR support in Britain. A final section discusses the implications of our research.

The British populist radical right

UKIP is Britain’s most significant PRR party; it has enjoyed unusual popularity as a minor party in a first-past-the-post system, and its electoral growth helped to precipitate the EU referendum (Carella and Ford Citation2020). Although the Brexit Party has been unable to replicate UKIP’s General Election vote tallies, the party was the runaway winner of the 2019 European Elections during a time when the UK’s departure from the EU was the main issue (Campbell and Shorrocks Citation2021).

The novelty of the Brexit Party means that few political scientists have had the opportunity to research its voters. However, it is surprising that UKIP has been excluded from most cross-national analyses that focus on the PRR gender gap. It is possible that UKIP’s status as a PRR party may not be at the forefront of observers’ minds because of its origins as a single-issue, anti-European Union pressure group (Ford and Goodwin Citation2014). It is also plausible that UKIP’s reluctance to embrace “blood and soil” nationalism (March Citation2017, 293) may lessen its radical appearance, while the notoriety of the BNP’s violence and open racism may make it a more obvious contender for any cross-national comparisons.

We follow Mudde (Citation2007) in contending that an ideological core of nativism, authoritarianism and populism defines the populist radical right. Nativism refers to a belief that states should be exclusively inhabited by native members, with non-native elements posing a threat. Authoritarianism reflects a desire for a strictly ordered society where infringements of authority are harshly punished. Mudde (Citation2004, Citation2007) understands populism as an ideology that considers society to be separated into two homogenous and competing groups: the pure people and the corrupt elite.

Analysis of recent UKIP manifestos (March Citation2017) reveals that the party embodies Mudde’s (Citation2007) definition of PRR by displaying indicators of nativism, authoritarianism and populism. Our examination of UKIP’s most recent manifesto – “Policies for the People” (Citation2019) – identifies similar traits as the party accuses non-UK citizens of abusing the National Health Service, calls for a reduction in early release prison sentences, and rejects the House of Lords as “an affront to democracy”. The Brexit Party’s “People’s Contract” (Citation2019) contains indicators of populism and nativism. The party demands “fundamental democratic reforms to fix our broken political system and make Parliament serve the People”, and its call for border protection was complemented by Farage's campaign pledge to cap immigration at a "sensible" 50,000 per year (BBC Citation2019-08-26). However, the manifesto contains relatively little of the law-and-order rhetoric that often characterizes authoritarianism, although it does demand an increase in visible policing that would see officers focus on violent crimes, “rather than enforcing restrictions on free speech”. We are therefore of the view that while UKIP is clearly captured by Mudde’s (Citation2007) definition of PRR, the Brexit Party’s status is less clear-cut. March (Citation2017) contends that classifying a party as populist can be a question of degree (more-or-less) rather than dichotomy (either-or); if we extend this approach when ascertaining whether a party is populist radical right, then it is arguable that the Brexit Party’s a PRR party, albeit to a lesser degree than UKIP.

Explanations for the populist radical right gender gap

Perhaps the most prominent explanation for the PRR gender gap contends that gender differences within the labour market fuel the anti-immigrant attitudes that underpin PRR support. Here, it is argued that because men with lower levels of education are overrepresented in blue-collar industries, they may have to compete with immigrants for jobs in a globalized economy and will therefore be attracted to the radical right’s xenophobic and protectionist sentiments (Arzheimer and Carter Citation2006; Betz Citation1994; Coffé Citation2018). Although anti-immigrant attitudes are an important driver of radical right voting (Clarke et al. Citation2016), the strength of this explanation for the gender gap is undermined by existing studies which reveal that men do not necessarily hold more strongly anti-immigrant attitudes than women (Harteveld et al. Citation2015; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015a). Indeed, previous research drawing on European Social Survey data suggests that within Britain, women are more likely than men to be opposed to immigration (Ponce Citation2017).

Authoritarian beliefs are also an important attitudinal component of radical right support (Donovan Citation2019), and some studies contend that gender differences make men more likely than women to endorse authoritarianism (Gilligan Citation1982). Campbell’s (Citation2006) study of UK voters found that some significant differences exist between men’s and women’s positions on the liberal-authoritarian scale; however, other research suggests that gender differences over authoritarian attitudes are overstated (Harteveld et al. Citation2015). Existing scholarship within the UK has found that voting to leave the European Union – a key UKIP and Brexit Party issue – is strongly correlated with Right-Wing Authoritarianism (Kaufmann Citation2016). However, this research did not focus on the gender differences – if any – of these authoritarian attitudes.

Voters who are discontented with the political system are more likely to support populist parties, and for this reason, gender differences in democratic satisfaction could be relevant to explaining the PRR gender gap (Givens Citation2004; Harteveld et al. Citation2015). However, it is unclear whether and why women should be more satisfied with democracy than men. Indeed, Harteveld et al.'s (Citation2015) study of the gender gap across 17 European countries found that women are slightly less contended with democracy than men. Women’s greater democratic discontent could potentially be explained by their historical exclusion from the political process or by the low levels of women’s descriptive representation around the world (see Williams, Snipes, and Singh Citation2021). If women are indeed more dissatisfied with democracy than men, then the radical right gender gap is unlikely to be explained by this particular attitudinal difference.

Finally, attitudes towards redistribution are also held to be relevant to the gender gap; here, the argument goes that because women are more dependent than men on the welfare state, PRR economic hostility towards public services may render this party family unappealing to women (see Gidengil et al. Citation2005). This argument has been challenged, though, by research suggesting that PRR supporters generally do not have right-wing economic attitudes (Allen and Goodman Citation2021) and by research showing that PRR parties are increasingly practising “welfare chauvinism” whereby support for redistribution is predicated on the fact that welfare benefits should be restricted to native citizens only (Harteveld et al. Citation2015). Certainly, in the British case, there is evidence that UKIP practised welfare chauvinism by seeking to restrict immigrant access to health and financial benefits while increasing British national access to those same services (Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2018).

Scholars also examine sociodemographic characteristics, in addition to attitudes, as a way to explain the radical right gender gap. Previous cross-national studies of the European gender gap have found that manual workers and individuals with lower levels of education – who tend to be men – disproportionately support the PRR (Givens Citation2004; Immerzeel, Coffé, and van der Lippe Citation2015). However, there is some evidence that the sociodemographic characteristics of British radical right supporters may be more heterogeneous than their European counterparts. Although early studies of UKIP revealed that support was concentrated amongst the skilled working classes (Ford and Goodwin Citation2014), more recent research (Evans and Mellon Citation2016) shows that UKIP attracts a coalition of the working class and the “petty bourgeoisie” – the self-employed and small employers. Indeed, numerically, most of their supporters are drawn from the lower professional and managerial occupations. If fewer British women are employed in working class or lower professional/managerial occupations, then the potential pool of UKIP/Brexit Party voters could be smaller amongst women than men.

Women’s greater religiosity is another demographic characteristic that is potentially relevant to the gender gap; here, is argued that because churches throughout Europe condemn radical right anti-immigrant rhetoric, churchgoers are unlikely to support this party family (Mayer Citation2015; Betz Citation1994). However, it is unclear whether religiosity is likely to influence the British radical right gender gap. Tilley (Citation2015) observes that religious cleavages in the UK are associated with party affiliations but also notes that because the number of people who actively practise their religion over time has fallen, religiosity is unlikely to be a highly salient element of political behaviour.

So far, our discussion has focused on potential gender differences in the demand-side factors of PRR support. However, supply-side factors are also important (see Mudde Citation2007); here, the role of party leadership may be particularly relevant to the PRR gender gap. Vote choice scholarship has shown the significance of party leaders in general (Bittner Citation2011), and various additional studies have suggested that the party leader is especially important in understanding support for PRR parties (Coffé and van den Berg Citation2017; Evans, de Geus, and Green Citationn.d.). This may be because PRR parties are often centred around a leadership figure and tend to lack more formalized structures. However, other research has found that party leader effects are similar for mainstream and PRR parties (van der Brug and Mughan Citation2007).

With respect to party leadership and the gender gap, Mayer (Citation2015) has found that in the 2012 French presidential election – and unlike her father before her – Marine Le Pen was equally supported by male and female voters. Mayer (Citation2015) observes that feelings of warmth towards Marine Le Pen were instrumental in closing the PRR gender gap, and, second only to Euroscepticism, were the best predictor of National Front voting. The role of leadership in the PRR gender gap is also examined in Allen and Goodman’s (Citation2021) cross-national study; here, the authors speculate that female leaders could reduce the radical right gender gap by (1) lessening the stigma associated with their party family if they are perceived as less extreme than their male counterparts (see also Harteveld et al. Citation2015; Ben-Shirit et al. Citation2021) and (2) providing women voters with descriptive representation. Somewhat surprisingly, Allen and Goodman (Citation2021) found that female leadership negatively predicted PRR support, although the authors acknowledge that because their study only included four parties led by women, this finding should be probed further.

This previous scholarship, then, suggests that party leadership may affect the PRR gender gap. However, because this research largely focuses on female leaders, the role played by male leaders in creating the gender gap is obscured. This is a significant omission; PRR parties (as well as mainstream parties) are overwhelmingly led by men, and strongman populism is on the rise throughout Western Europe and beyond (see Smith Citation2021). Importantly, Harteveld et al. (Citation2015) and Spierings and Zaslove (Citation2015b) speculate that the political style, and masculine leadership and rhetoric, that characterizes the PRR may deter women voters from supporting this party family. Turning to the British case, there is a strong argument that Nigel Farage promoted masculinity within both UKIP and the Brexit Party. The public persona of Farage is that of an Everyman: a straight-talker who shuns political correctness and is rarely photographed without his “pints-and-fags” (Starck Citation2020, 43). Farage as UKIP leader promoted toxically masculine practices within the organization (Daddow and Hertner Citation2019, 4–5): he made comments which denigrated women, admitted that the party looked “blokeish”, and engaged in stereotypically masculine behaviours such as beer-drinking, gambling and smoking. Throughout 2019 – the year of the Brexit Party’s participation in the European and General Elections – Farage’s masculine leadership and rhetoric continued; he bemoaned his exclusion from a pub crawl organized by Wetherspoons chairman Tim Martin, and used his platform within the European Parliament to urge fellow MEPs to “[s]trike a blow for your citizens” by voting against the candidacy of Ursula von der Leyen (Higgins Citation2020; European Parliament Citation2019).

The populist radical right gender gap, then, is typically explained with reference to attitudinal or sociodemographic differences, although some scholars (Allen and Goodman Citation2021; Mayer Citation2015; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015b) have suggested that a focus on PRR leadership could also shed light on this puzzle. With this in mind, we now turn to an empirical test of these various explanations for female support of the British populist radical right throughout recent elections.

Data

We use the combined wave 1–19 of the British Election Study Internet Panel (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2020) for our analysis. This data consists of 19 waves and covers 3 general elections (2015, 2017 and 2019) and 2 European elections (2014 and 2019). BESIP consists of an online sample of YouGov panel members that completed repeated questionnaires over time. Our analysis focuses on support for UKIP and the Brexit Party as British populist radical right parties. We exclude the British National Party (BNP) due to its small number of supporters during this time and because the party, with its history of physical confrontations, is likely to be classified as extreme - rather than populist radical - right (Goodwin Citation2011).

The gender gap in populist radical right support

We find evidence of gender gaps in PRR support in all elections under study (). The support base for UKIP and the Brexit Party is always predominantely male, and the percentage of the male electorate that voted for these parties is always greater than the percentage of the female electorate that did so. The gender gap in PRR support is significant in all elections under study. There is over-time variation, with some indication that the gender gap has decreased, given that the largest gap was in 2014 (6%). This may reflect the fact that the positions held by UKIP and the Brexit Party – especially about the EU – have become increasingly mainstream, especially in the wake of the referendum. However, the second-largest gender gap was found in the 2019 European Elections (5%);this suggests that the gender gap is dependent on the overall levels of support for the party and we see larger gender gaps when the parties received their highest levels of support.

Table 1. Gender gaps in PRR support in Britain.

Explaining the populist radical right gender gap in the UK: demographic features and attitudinal differences

After having established a gender gap in support for the British PRR, we examine potential reasons for it. Existing studies have focused on two key explanations. First, they have suggested that differences in men’s and women’s demographic profiles, specifically types of occupation and levels of education and religiosity, may explain the lower levels of support among women (Arzheimer and Carter Citation2006; Betz Citation1994; Coffé Citation2018). Second, they have suggested that men and women may hold different political attitudes.

To understand the potential role of demographics, we took a descriptive look at demographic differences between the male and female electorate in Britain, and PRR supporters in particular (details in online supplementary materials Tables A1 and A2). In line with comparative literature, we find that men and women differ on certain demographics that are associated with PRR support. Women are more religious than men, and men and women work in different occupation sectors. Specifically, women are more likely to work in “intermediate” jobs (jobs that combine service and labour), but are less likely to work in “routine” jobs than men. Although it is thus possible that the under-representation of women especially in “lower supervisory and technical” and “routine” jobs may explain their under-representation among radical right supporters, we find that the occupational composition of PRR supporters mostly mirrors that of the general population, suggesting that demographic difference might not hold much explanatory power. We do not find any clear differences in the proportion of men and women with a university degree. We conduct a formal test to see whether different demographics are predictive for a vote for UKIP or the Brexit Party for men and women and do not find this to be the case (supplementary materials, Table A5).Footnote1

A second explanation for the PRR gender gap is differential attitudes. Several key attitudes have been linked to support for the radical right, including nativism – which consists of anti-immigrant and nationalist views – authoritarianism, and, to a lesser extent, attitudes toward economic redistribution and democratic dissatisfaction (Harteveld et al. Citation2015; Immerzeel, Coffé, and van der Lippe Citation2015; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015a; Citation2017; Givens Citation2004). In the context of Britain, attitudes toward the EU have also been shown to be crucial in explaining PRR support (Evans, de Geus, and Green Citationn.d.). We first explored whether men and women in Britain hold distinctly different attitudes that may explain differential levels of support for the PRR. We provide this information in Table A6 of the supplementary materials.

This analysis suggests that there are significant differences – on average – in key attitudes across men and women in the British electorate. However, it is not the case that British women consistently hold attitudes that would make them less predisposed toward voting for the PRR. Women display higher levels of Englishness than men at every point in time and are more likely to hold the view that immigrants are detrimental to the British economy. Women are also more authoritarian in their views than men, although this difference is partially driven by the fact that women are significantly more authoritarian on a particular item of the authoritarian scale – censorship. When this item is removed differences are not always significant and otherwise substantively small. Either way, women are not significantly less authoritarian when compared to men.

On other attitudes, women seem less supportive of the radical right worldview. With the exception of 2015, women are more satisfied with democracy than male respondents and women are more in favour of redistribution.Footnote2 When we look at EU attitudes and the cultural dimension of immigration an interesting pattern can be observed. Prior to the EU referendum (June 2016), the average female respondent was more negative about the EU compared to the average male respondent and was also more likely to state that immigrants undermine British culture. Yet, post-referendum, men become more opposed to the EU and more anti-immigrant on the cultural dimension. This could suggest that the EU referendum had a stronger effect on activating these attitudes in men, or that the EU referendum and its accompanying campaign had a negative effect on women’s support for these attitudes. That control formed a key part of the Brexit campaign – as evidenced by its slogan “Take Back Control” – may be relevant here, with gender studies literature indicating that exerting and resisting control are key features of masculinity (Schrock and Schwalbe Citation2009).Footnote3

It is also possible that certain attitudes associated with PRR support may exert different influences on men's and women's respective vote choices. Women may be more nationalist than men, but if nationalism is not important to women’s vote choice then this does little to explain women’s PRR support or the gender gap. This is referred to by Harteveld et al. (Citation2015) as a potential moderation effect of gender. We test this through conducting regression analysis of PRR vote choice based on attitudes and demographics. We find no evidence of moderation; there are no gender differences in the types of attitudes that matter in predicting a vote for UKIP or the Brexit party. For both men and women, EU and immigration attitudes are key predictors of PRR support. We provide these results in the online supplementary materials (Table A8).

Explaining the gender gap: leadership

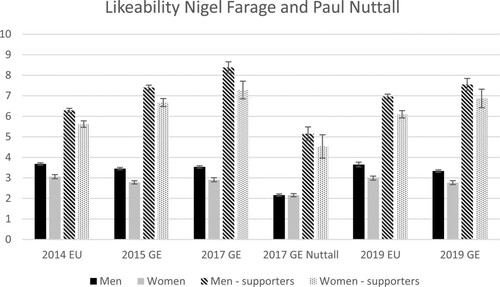

We now move to an analysis of Nigel Farage and his role in explaining gender differences in support for UKIP and the Brexit Party. We present the mean level of Farage’s likeability for men and women in the general electorate and for those who voted for UKIP and the Brexit Party in . We also include likeability scores for Paul Nuttall, who was UKIP’s leader in the 2017 General Election. Leader likeability is measured on a 0–10 scale with respondents being asked how much they like/dislike a given party leader.

Figure 1. Support for Nigel Farage and Paul Nuttall. Data are weighted, non-voters and don’t know responses excluded. Leader likeability from pre-election waves. Bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals. Supporters are those that voted for UKIP/Brexit Party in the given election.

It is evident that Farage is more liked among men than among women. Differences in Farage’s average likeability between men and women are statistically significant in all elections for both the general electorate and UKIP and Brexit Party supporters (Tables A9 and A10 of online supplement). Further, the differences are substantive, ranging between 0.56 and –0.67 on a 0–10 scale in the general electorate and between 0.2 and 1.10 among UKIP and Brexit Party supporters. By contrast, likeability scores of Paul Nuttall do not differ significantly between men and women in the general electorate, although they do differ significantly among party supporters, with women liking Nuttall less. We do note that Paul Nuttall was largely unfamiliar to people, with almost 30% of our sample giving a “Don’t Know” response to his likeability.

In line with existing research, we find that women were much more likely to answer “Don’t Know” when asked how much they like/dislike Nigel Farage and Paul Nuttall (Table A11). On the one hand, this may indicate that women do like Nigel Farage, but because they experience higher levels of social desirability pressure and consider Nigel Farage a controversial figure, they answer “Don’t Know” instead. The other option is that women do not have a clearly formulated opinion of Nigel Farage, either because they perceive his appeal to be mainly targeted to men or because his leadership is less important to their vote choice

To get some traction on how gender differences in Don’t Know responses affect our findings, we also looked at gender differences in the likeability ratings for other party leaders in this period (Table A12 online supplement). We find that female “Don’t Know” responses outnumber male “Don’t Know” responses in all cases. Further, the percentage of women that answered “Don’t Know” when asked about Nigel Farage is similar to that for Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn, thereby suggesting that this is not a pattern that is specific to Nigel Farage, but rather reflective of gender differences in survey responding.

To assess the robustness of our findings we rerun our analyses presented above and replace a “Don’t Know” response for both men and women with the average male or average female response.Footnote4 Using this approach we find the same substantive results. From this we conclude that women in Britain are significantly less positive about Nigel Farage than men, thereby reducing his appeal among the female voter pool.

Gender gap in populist radical right support: assessing the explanations

After having discussed three potential explanations for the gender gap in radical right support in isolation (demographics; attitudes; Nigel Farage), we now look at these explanations alongside each other. To assess the explanatory value of social-structural, attitudinal and leadership likeability, we take a stepwise regression approach. In the first model, we simply present the gender gap size; in the second model we include demographic variables (age, work status, education level, religiosity and occupation type); in the third set of models, we add attitudes (redistribution, immigration, EU attitudes, authoritarianism, nationalism and democratic dissatisfaction); and in the final model, we add likeability ratings of Nigel Farage and, in the case of the 2017 General Election, Paul Nuttall. To compare regression coefficients across models, we run OLS regression models with robust standard errors. Given that our dependent variables are binary (voted for UKIP or Brexit Party or not), these are linear probability models. We present the same models in the online supplement using logistic regressions and find the same substantive results (Tables A18 and A19).

Vote choice is measured in the post-election waves. Demographics are also taken from the post-election waves, but missing data on these variables are filled in with pre-election wave data to maintain a larger portion of the sample for the regression analyses. Attitudes are measured in the pre-election waves, with the exceptions of attitudes in the 2019 European elections model, which are taken from the post-election wave to maintain a larger sample size and to better reflect the gender gap as found in .Footnote5 The exception to this is leadership ratings for which we use pre-election values to avoid endogeneity concerns. In the case of the 2017 elections, we present a model with Farage and a model with Nuttall.

What we expect to see is a gender gap in the first models (in line with the gender gap in ). Then, if either of the explanations underlies the gender gap, we expect this gender gap to be reduced in the subsequent models. Looking at , we see that there is a statistically significant gender gap in support for UKIP and the Brexit Party in all elections. The gender gap does not disappear – and occasionally increases – when demographics and political attitudes are added to the model, thereby suggesting that these do not explain the source of the gender gap.

Table 2. Regression models gender gap radical right support UKIP and Brexit Party.

However, when the likeability of Nigel Farage is added to the models, the gender gap reduces in size and ceases to be significant. The 2017 General Election further offers an interesting case where we can look both at the effect of including attitudes toward Farage and to the effect of including attitudes toward the then UKIP leader Paul Nuttall. Here we see that adding Farage likeability does render the gender gap insignificant, but including Nuttall does not; this suggests that the gender gap is really a Farage effect.

The importance of Nigel Farage in gathering votes for UKIP and the Brexit Party should not be under-estimated. For instance, using the full regression models including demographics and attitudes, we find that moving from the lowest to the highest like-score for Farage increased the likelihood of voting for the Brexit Party in the 2019 European elections from 0.23 to 0.72. To give an example of how the different levels of Farage likeability matter, we find that in the 2019 EU elections, a voter who held the average male likeability score of Nigel Farage had a predicted likelihood of voting for the Brexit Party in this election of 0.40, whereas a voter who held the average female position on Nigel Farage had a likelihood of voting for the Brexit Party of 0.37, holding all other attitudes at their mean value.

Discussion and conclusion

We find that the support base of UKIP and the Brexit Party in five recent elections was predominantly male. In testing explanations for the gender gap in PRR support in Britain, we find little evidence for social-demographic or attitudinal differences. Rather, we find that Nigel Farage’s leadership of both these parties is a key explanatory factor for the gender gap in PRR support in Britain. Farage was an important draw to both UKIP and Brexit Party voters across all elections included in our study. And yet, across all elections, we find that women are much less supportive of Farage compared to men. We have an interesting comparison case with Paul Nuttall as UKIP’s leader in 2017. We find that among the general electorate there were no gender differences in his likeability, suggesting that Farage was particularly unappealing to the female electorate. The fact that the success of UKIP and the Brexit Party have been so strongly linked to Farage suggests a conflict: in the absence of Farage, the party appears to struggle to attract general levels of support, but his presence prevents the party from drawing in a larger segment of the female electorate. To further understand this trade-off requires a better understanding of the extent to which the performance of masculine leadership is a particular draw (deterrent) to male (female) PRR supporters in Britain and elsewhere.

Farage’s masculine leadership style may be off-putting to women voters, who are in turn deterred from supporting his parties. In addition to his “man at the pub” political identity, the pro-Brexit rhetoric of Farage’s two parties at times slid into “a nationalism infused with ideas of restored empire and repossession” (Piatto Citation2018, 122). Given the close connection between manhood and nationhood (Nagel Citation1998), Farage’s rhetoric is unlikely to resonate with women voters. Future scholarship could further interrogate the role of Farage’s masculinity in UKIP/Brexit Party support by asking voters which gendered traits they associate with Farage (for example, decisiveness and aggression, or warmth and compassion) and whether they view those traits favourably or unfavourably. That some women who are not strongly supportive of Farage still vote for him is a finding that is likely to interest scholars of vote choice more broadly; because voters tend to have very high favourability ratings of the leaders of the parties they support (Coffé and van den Berg Citation2017), women's simultaneous lower levels of enthusiasm of Farage and endorsement of his party are something of an aberration. Future researchers could conduct qualitative interviews with women UKIP/Brexit Party voters who dislike Farage to probe this anomaly.

Unfortunately, our research has been unable to empirically test every explanation for the gender gap. We note two in particular. First, we have not considered here whether increasing equality between men and women fuels the gender gap. Norris and Inglehart (Citation2019) point to changes such as the replacement of traditional patriarchal values with norms favouring gender equality. White men without a college degree may be particularly resentful of these changes and embrace the socially conservative and authoritarian values that often align with PRR support. Second, because our data lacks the relevant measures, we have not considered whether British women are more motivated than men to control prejudice, and therefore less likely to support the radical right (see Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Citation2018).

Our research has also been unable to take into account the heterogeneity and intersectionality of women’s identities (Annesley, Gains and Sanders, Citation2021). Instead, we present research that focuses on women as a homogenous group, defined and differentiated by their gender. There might be much more substantive gender gaps in PRR support between men and women within certain segments of the population (e.g. young men and young women) (see Shorrocks Citation2016), but gaps in PRR support might also be substantial across various groups of women (e.g. white vs. non-white; or educated vs. non educated women). Understanding within-gender gaps and the importance of intersectional identities and PRR support is thus a crucial avenue for future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The exception is 2014 and occupation where we find that occupation type was a significant predictor for women, but not for men – although small employeeship was significant also for men. We don’t find statistically significant gender differences in the predictive power of occupation type in the other elections.

2 Although as discussed – this may or may not predispose them toward the PRR depending on whether PRR parties adopt welfare chauvinistic standpoints.

3 Table A7 in the online supplement replicates the main analysis but accounts for Don’t Know responses by setting these to the mid-points of the scale. This does not substantively alter the results, the exception is EU-attitudes where we find no significant gender difference prior to the referendum when using this approach.

4 Note we opt for this rather than setting the response to the mid-point of the scale (5) since the mean response for men and women in the electorate is below 5. Choosing the theoretical midpoint would strongly inflate Farage’s scores among both men and women. Results in Tables A13 and A14 of the online supplement.

5 For the 2019 EU model, the pre-elections wave model has N = 7647 compared to N = 9460. Furthermore, the “raw” gender gap in the 2019 European elections was approx. 5% and statistically significant (), which is better reflected when using the larger sample used here (gap = 3% and significant) versus the smaller sample (2% and not significant). Table A17 provides models using pre-election attitudes, and this specification supports the results presented here: the gender gap increases and is significant when demographics and attitudes are included, but is insignificant once attitudes toward Farage are accounted for.

References

- Allen, T., and S. Goodman. 2021. “Individual- and Party-Level Determinants of Far-Right Support among Women in Western Europe.” European Political Science Review 13 (2): 135–150.

- Annesley, C., F. Gains, and A. Sanders. 2021. “How Do Parties Appeal to Women Voters?” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.

- Arzheimer, K., and E. Carter. 2006. “Political Opportunity Structures and Right-Wing Extremist Party Success.” European Journal of Political Research 45 (3): 419–443.

- BBC. 2019. "General Election 2019: Nigel Farage Calls for 50,000 Net Migration Cap." Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election-2019-50478341.

- Ben-Shitrit, Lihi, Elad-Strenger Julia, and Hirsch-Hoefler Sivan. 2021. ““Pinkwashing” the Radical-right: Gender and the Mainstreaming of Radical-right Policies and Actions.” European Journal of Political Research.

- Betz, H. G. 1994. Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. Lt Hampshire: The Macmillan Press.

- Bittner, Amanda. 2011. Platform or Personality?: The Role of Party Leaders in Elections. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brexit Party. 2019 “Contract with the People.” Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.thebrexitparty.org/contract/.

- Campbell, R. 2006. Gender and the Vote in Britain: Beyond the Gender Gap? Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Campbell, R., and R. Shorrocks. 2021. ““Gender and the Vote in 2019: Change or Continuity?” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.

- Carella, L., and R. Ford. 2020. “The Status Stratification of Radical Right Support: Reconsidering the Occupational Profile of UKIP’s Electorate.” Electoral Studies 67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102214.

- Clarke, H., P. Whiteley, W. Borges, D. Sanders, and M. Stewart. 2016. “Modelling the Dynamics of Support for a Right-Wing Populist Party: the Case of UKIP.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 26 (2): 135–154.

- Coffé, H. 2018. “Gender and the Radical Right.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren, 200–211. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Coffé, H., and J. van den Berg. 2017. “Understanding Shifts in Voting Behaviour Away from and Towards Radical Right Populist Parties: The Case of the PVV Between 2007 and 2012.” Comparative European Politics 15: 872–896.

- Daddow, O., and I. Hertner. 2019. “Interpreting Toxic Masculinity in Political Parties: A Framework for Analysis.” Party Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819887591.

- Donovan, T. 2019. “Authoritarian Attitudes and Support for Radical Right Populists.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 29 (4): 448–464.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, L. 2018. “Welfare Chauvinism in Populist Radical Right Platforms: The Role of Redistributive Justice Principles.” Social Policy & Administration 52: 293–314.

- European Parliament. 2019. “Debates.” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-9-2019-07-16-ITM-003_EN.html.

- Evans, G., R. de Geus and J. Green n.d. “The Conservative Party and the Radical Right: How the Conservatives Won the 2019 UK General Election.”

- Evans, G., and J. Mellon. 2016. “Working Class Votes and Conservative Losses: Solving the UKIP Puzzle.” Parliamentary Affairs 69 (2): 464–479.

- Fieldhouse, E., J. Green, G. Evans, J. Mellon, and C. Prosser 2020. British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1–19.

- Ford, R., and M. J. Goodwin. 2014. Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain. Oxon: Routledge.

- Gidengil, E., M. Hennigar, A. Blais, and N. Nevitte. 2005. “Explaining the Gender Gap in Support for the New Right.” Comparative Political Studies 38 (10): 1171–1195.

- Gilligan, C. 1982. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. United States of America: Harvard University Press.

- Givens, T. E. 2004. “The Radical Right Gender Gap.” Comparative Political Studies 37 (1): 30–54.

- Goodwin, M. J. 2011. New British Fascism: Rise of the British National Party. Oxon: Routledge.

- Harteveld, E., and E. Ivarsflaten. 2018. “Why Women Avoid the Radical Right: Internalized Norms and Party Reputations.” British Journal of Political Science 48 (2): 369–384.

- Harteveld, E., W. Van Der Brug, S. Dahlberg, and A. Kokkonen. 2015. “The Gender gap in Populist Radical-Right Voting: Examining the Demand Side in Western and Eastern Europe.” Patterns of Prejudice 49 (1–2): 103–134.

- Higgins, M. 2020. “Political Masculinities and Brexit: Men of war.” Journal of Language and Politics 19 (1): 89–106.

- Immerzeel, Tim, Hilde Coffé, and Tanja van der Lippe. 2015. “Explaining the Gender Gap in Radical Right Voting: A Cross-National Investigation in 12 Western European Countries.” Comparative European Politics 13 (2): 263–286.

- Kaufmann, E. 2016. It’s NOT the Economy, Stupid: Brexit as a Story of Personal Values. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/personal-values-brexit-vote/.

- March, L. 2017. “Left and Right Populism Compared: The British Case.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19 (2): 282–303.

- Mayer, N. 2015. “The Closing of the Radical Right Gender gap in France?” French Politics 13: 391–414.

- Mudde, Cas. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 541–563.

- Mudde, C. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nagel, J. 1998. “Masculinity and Nationalism: Gender and Sexuality in the Making of Nations.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 21 (2): 242–269.

- Norris, P., and R. Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Piatto, G. 2018. “The Crisis of the Male Role Through the Lens of the Brexit Campaign.” In Miss Man? Languaging Gendered Bodies, edited by G. Balirano and O. Palusci. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Ponce, A. 2017. “Gender and Anti-immigrant Attitudes in Europe.” Socius 3: 1–17.

- Schrock, D., and M. Schwalbe. 2009. “Men, Masculinity, and Manhood Acts.” Annual Review of Sociology 35 (1): 277–295.

- Shorrocks, R. 2016. “Modernisation and Government Socialisation: Considering Explanations forGender Differences in Cohort Trends in British Voting Behaviour.” Electoral Studies 42: 237–248.

- Smith, J. C. 2021. “Bulldozing Brexit: The Role of Masculinity in Leaders’ Campaign Rhetoric in the 2019 UK General Election.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.

- Spierings, N., and A. Zaslove. 2015a. “Gendering the Vote for Populist Radical-Right Parties.” Patterns of Prejudice 49 (1-2): 135–162.

- Spierings, N., and A. Zaslove. 2015b. “Conclusion: Dividing the Populist Radical Right Between ‘LiberalNativism’ and Traditional Conceptions of Gender.” Patterns of Prejudice 49 (1–2): 163–173.

- Spierings, N., and A. Zaslove. 2017. “Gender, Populist Attitudes, and Voting: Explaining the Gender gap in Voting for Populist Radical Right and Populist Radical Left Parties.” West European Politics 40 (4): 821–847.

- Starck, K. 2020. “I am a Bull Trader by Nature: Performing Nigel Farage.” NORMA 15 (1): 43–58.

- Tilley, J. 2015. “'We Don't Do God'? Religion and Party Choice in Britain.” British Journal of Political Science 45 (4): 907–927.

- UK Independence Party. 2019. “Policies for the People.” https://www.ukip.org/pdf/UKIP_Manifesto_Nov_2019.pdf

- van der Brug, W., and A. Mughan. 2007. “Charisma, Leader Effects and Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties.” Party Politics 13 (1): 29–51.

- Williams, N. S., A. Snipes, and S. P. Singh. 2021. “Gender Differences in the Impact of Electoral Victory on Satisfaction with Democracy.” Electoral Studies 69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102205.