ABSTRACT

Recently, the issue of harassment and intimidation of women in politics in long-established democracies has become a source of concern. Current research emphasizes that while women may be more frequently attacked, not all incidents of abuse against women in politics are of a gendered nature. This finding prompts further questions such as are women more frequently targeted because they are women and does such targeting inhibit women from fully participating in political campaigning? Using data from the Representative Audit of Britain’s survey of candidates contesting the 2019 General Election, this study shows that harassment has a negative electoral effect for women, even while controlling for the visibility of the candidate. This article argues that the harassment of women candidates in the UK is gendered, both in its motives and outcomes as it forces women to modify their campaign activities in ways that diminish their chances of gaining office. Our findings contribute to the theoretical and empirical understanding of violence towards women in politics and gendered political violence.

Introduction

When a new General Election was announced in November 2019, some 20 women MPs from different parties decided to step down and not seek re-election. They cited the daily abuse, harassment and intimidation as a reason for doing so, suggesting that harassment would impact negatively all efforts made to improve the representation of women in the UK (Perraudin and Murphy Citation2019). Surprisingly, a record number of women presented themselves for office, as 37% of candidates were female and a record number of women candidates went on to become MPs (220), comprising 34% of the total number of members of the House of Commons (Collignon Citation2019). The increase in the number of women standing for office in 2019 compared with 2017 can be the result of all the institutional mechanisms, such as nominating women in winnable situations and All-Women Shortlists, that parties have put in place to improve recruitment among women. But the substantive and frequent abuse they surfer indicates that they have to pay an additional cost for being disruptive in a traditionally male-dominated sphere, especially if we consider that visibility in politics is a key driver for harassment, abuse and intimidation (Hayes and Lawless Citation2016; Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020; Håkansson Citation2021). The case of the UK suggests a tension between cultural, institutional and psychological factors, indicating that the effects of harassment on representation may not be straightforward to observe. This presents an important question for the descriptive and substantive representation of women in the UK: are women more frequently targeted because they are women and does such targeting inhibit women from fully achieving electoral success? In this article, we put forward the argument that the effect of harassment and intimidation on women’s representation is mediated by women’s changes in campaign-style as a reaction to such experiences, which in turn, reduces their electoral success.

Pundits, academics and practitioners in the UK have preferred to use the terms “harassment”, “intimidation” and “abuse” rather than “violence”, which is the preferred academic term in the field (James et al. Citation2016; Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020). In this context, harassment, intimidation and abuse constitute forms of violence, overlapping with the definition of violence against women in policis as a continuum that manifest in different and often, intertwined ways, that include online and offline physical, psychological, economic and semiotic forms of violence perpetrated against women in politics (Kelly Citation1988; Krook Citation2017, Citation2020). In this article, we use broadly the terms harassment, abuse and intimidation to refer to different acts and forms of violence to be consistent with the language used in the UK context and in the survey used to offer empirical evidence to our claims and the terms violence against women in politics to when the literature explicitly uses such term.

The emerging and fast-growing literature on violence against women in politics (VAW-P) has mainly focused on the conceptualization of violence and on raising awareness about this problem to motivate policy change (Kuperberg Citation2018; Krook and Restrepo Sanin Citation2019; Krook Citation2017). The findings of this body of research suggest that women are being targeted because of their sex and their ambition to participate in politics (Herrick et al. Citation2019; Kuperberg Citation2018). The violence suffered by women in politics has significant gendered consequences for women and the democratic life of the country (Bardall Citation2020; Piscopo Citation2016) because it reduces policy effectiveness, distorts the political pipeline, and diminishes political transparency and accountability (Krook Citation2018, 65).

There is a need to understand the gendered dimensions of political violence (Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo Citation2020; Piscopo Citation2016), a matter that has been challenging to study. One reason is that with some exceptions (Herrick et al. Citation2019; Herrick and Franklin Citation2019; Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020; Håkansson Citation2021; Bjarnegård Citation2021), current research is based on anecdotal evidence, focus exclusively on elected women or in visible, physical acts of violence taking place in the public sphere (Bjarnegård Citation2018). The lack of comparison between men and women politicians makes it difficult to reach conclusions regarding the gendered nature of the abuse and to disentangle violence against women in politics from gendered political violence and general structural violence (Piscopo Citation2016). Additionally, the traditional focus on elected women difficults disentangling their position, visibility and sex from the issues they advocate, obscuring the relationship between harassment with electoral success.

This article looks at the direct and indirect gendered impact of harassment on women candidates’ electoral success. It does so by following Bjarnegård (Citation2018)’s recommendations to study men and women, their experiences of harassment, intimidation, threats, physical and psychological violence. The article looks at their gendered campaign alterations resulting from such experiences and their subsequent effect on electoral success. By doing so it contributes to our understanding of the gendered impact of intimidation and harassment on women and men politicians, an issue of high importance that has so far, been understudied.

This article shows that in the UK, women suffer from gendered violence that prevents them from reaching office. It disentangles the likelihood of harassment from the visibility of the candidate showing that when women react to harassment by modifying their campaign strategy, they also reduce their possibilities to get elected, in particular if they are forced to avoid constituency-intensive campaign activities such as canvassing. Harassment thus does not necessarily prevent already visible women from reaching office but reduces the chances of many more from achieving their goal. We test our argument using the Representative Audit of Britain (RAB) survey to candidates standing in the 2019 General Election. The response rate is 36% (N=1162). After a review of the relevant literature, we introduce our theoretical framework data and methods before presenting our results and conclusions.

Intimidation and harassment of political elites

It is not until very recently that the issue of harassment and intimidation of female politicians in long-established democracies started to become an international source of concern (Kuperberg Citation2018; Herrick et al. Citation2019; Håkansson Citation2021). Claims of widespread abuse can be understood in the light of the literature on psychology and political science focussing on cases of harassment and intimidation to politicians in office. Using surveys of sitting MPs, researchers have determined that the frequency in which Parliamentarians suffer from violence while performing their duties is alarming. In the UK, 81% of Parliamentarians surveyed in 2010 had suffered some form of abuse (James et al. Citation2016). This figure reaches 87 and 84% in New Zealand and Norway and it is considerably smaller in Canada (30%) (Adams et al. Citation2009; James et al. Citation2016; Every-Palmer, Barry-Walsh, and Pathé Citation2015).

Later surveys of British MPs on their experience with online trolling conducted in 2018 found that between 62 and 100% of respondents had experienced this form of harassment (Akhtar and Morrison Citation2019; McLoughlin and Ward Citation2017). According to these studies, female MPs received fewer abusive messages per day than male MPs, but the content of the abuse was different: women MPs report a substantially higher number of communications that involve threats of sexual abuse and physical violence or that questioned their position as MPs and asked them to resign (Southern and Harmer Citation2021). There are reasons to suggest that online abuse is not going to get better in the future as it increased in 2019 and 2017 compared to 2015 (Gorrell et al. Citation2018, Citation2021). The frequency and harmful nature of online communications have motivated researchers to call for further action by social media platforms to tackle the issue (Delisle et al. Citation2019). However, other than the political position of the victims (as MPs), this body of research neither examines the political nature of the attacks nor the gendered dimension of the abuse.

New research on violence against women in politics is being undertaken by Gender and Politics scholars. This emerging and fast-growing body of literature have focused on highlighting the experiences of female politicians and de-normalise them (Krook Citation2020; Krook and Restrepo Sanin Citation2019; Kuperberg Citation2018). This stream of research gives voice to women by presenting their stories and experiences. However, its focus on elected women using self-recruited surveys and narratives make it difficult to establish conclusively whether women indeed suffer more abuse than men and whether such abuse has a gendered component (Piscopo Citation2016). To understand the distinctive experiences of women in politics, it is necessary to take into account the particular experiences of men, who as gendered individuals, also suffer from abuse in particular forms (Bjarnegård Citation2018).

Some few studies have systematically analysed the experiences of men and women in politics (Herrick et al. Citation2019; Herrick and Franklin Citation2019; Håkansson Citation2021; Collignon, Sajuria, and Rüdig Citation2019; Bjarnegård, Håkansson, and Zetterberg Citation2020; Bjarnegård Citation2021). Herrick et al. (Citation2019) and Håkansson (Citation2021) focus on local level politicians in the US and Sweden to conclude that local politicians experience psychological and physical abuse. They find that women politicians experience more violence than men (Herrick et al. Citation2019) and that the gender gap in violence exposure increases together with the politician’s visibility (Håkansson Citation2021). Even fewer studies look at candidates, finding that in Sri Lanka, women candidates are exposed to forms of intimidation of a sexual nature more often than men (Bjarnegård, Håkansson, and Zetterberg Citation2020) while women candidates in the Maldives were more exposed to threats and to verbal and figurative sexualized aggression than men (Bjarnegård Citation2021). In the UK, Collignon and Rüdig (Citation2020) look at Parliamentary candidates standing in the 2017 General Election. Their results show that the harassment and intimidation of Parliamentary candidates are widespread across the UK with some important variations between parties and that female, young and leading candidates are being targeted. Their findings corroborate other research suggesting that the visibility of a candidate is a significant driver of abuse and highlight its intersectionality with age and gender (Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020; Håkansson Citation2021; Gorrell et al. Citation2021). Current literature comparing men and women in politics has made significant advances in showing that women are targeted by violence and this violence is motivated by their sex, their desire to participate in politics and their success when they do so. But the question regarding gendered impacts of harassment remains understudied.

Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Citation2020) urge researchers to look further from the frequency of attacks experienced by women and determine if gender is in the motive, the form and/or the impact before determining the presence of gendered political violence. They propose a useful framework to disentangle gendered political violence and violence against women in politics from simple political violence. They suggest that to study the gendered impact of political violence researchers should examine and unpack how different actors understand political violence and how differences in understanding and experiences define observed outcomes in policy, behaviour or institutional representation. Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Citation2020) conclude that gendered outcomes take place when women and other underrepresented groups change their political behaviour as a result of experiences of violence. While this theoretical framework is extremely useful to differentiate between gendered political violence and violence against women in politics, it presents the empirical researcher with an important challenge to disentangle the motives from the outcomes when looking at the institutional representation of women.

Researchers have raised the concern that political violence seems to be targeting women more intensively than men, posing an additional obstacle to political gender equality (Ballington Citation2018; Håkansson Citation2021). Other research has found that women with high political visibility are targeted because they are challengers in the political sphere whose norms privileged men (Håkansson Citation2021). Admittedly, the relationship between these two elements remains understudied, one reason being that institutional efforts have been made to increase the number of women sitting in legislative chambers (Hughes, Paxton, and Krook Citation2017) and they have been successful in doing so despite the abuse suffered by other women in politics.

In the case of the UK General Elections of 2017 and 2019, women were significantly more likely to be targets of abuse (Collignon, Campbell, and Rüdig Citation2021; Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020) but if we look purely at institutional outcomes, we may observe that actually, more women were elected than ever to sit in Parliament (Collignon Citation2019). Just looking at this outcome we would conclude that the political violence experienced by women does not have gendered outcomes, as defined by Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Citation2020). But this conclusion can be biased because the personal characteristics of a politician are linked to their likelihood to be elected (Collignon and Sajuria Citation2018) and the likelihood of harassment (Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020; Gorrell et al. Citation2018, Citation2021; Greenwood et al. Citation2019). It then becomes important to analyse the direct and indirect outcomes of harassment and intimidation to be able to determine whether or not outcomes are gendered. This article looks at disentangling this potential problem of endogeneity and takes a step forward to demonstrate that harassment indeed represents an obstacle for gender equality and representation because it makes it more difficult for women to get elected.

Candidate attributes are a salient concern in every election, and they reflect directly on the level of descriptive representation of particular groups. Gender, race and localness are candidate’s characteristics that matter for vote choice (Childs and Cowley Citation2011; Collignon and Sajuria Citation2018; Campbell and Cowley Citation2014) and that they are also key on defining campaign styles and intensity and together, they determine electoral success (Herrnson and Lay Citation2003; Zittel and Gschwend Citation2008). We argue that women react to the harassment experienced by modifying their campaign style and this, in turn, reduces their electoral success.

Campaigning activities at the constituency level can deliver important electoral payoffs, even when the candidate stands for an unpopular party (Fisher et al. Citation2019). Campaign strategies vary in their intensity the most directly linked to the constituency is the use of direct mail, doorstep canvassing, leafleting and electronic campaigning (Fisher, Cutts, and Fieldhouse Citation2011). In recent years, new forms of campaigning facilitated by the widespread use of new technologies of information are increasing in their importance vis-à-vis traditional campaign strategies that are constituency intensive (Chadwick and Stromer-Galley Citation2016) but the efficacy of face to face traditional campaigns is still superior (Fisher and Denver Citation2009; Gerber and Green Citation2000; Fisher et al. Citation2016). Since not all forms of the campaign are equally effective in improving candidate’s chance of success, we can expect that women forced to modify their campaign-style by reducing their face to face contacts as a result of harassment will see their electoral prospectus more negatively affected than women forced to reduce their online or remote interactions with potential voters.

H1 Harassment leads women to avoid key campaign activities.

H2 Women who modify their campaign-style/behaviour are less likely to succeed in the election.

H2a Women who modify their campaign-style/behaviour by reducing their face to face contact with constituents are less likely to succeed in the election.

H2b Women who modify their campaign-style/behaviour by reducing their online contact with potential voters will see a smaller or no effect on their chances of election than women who reduce their face to face interactions.

Data and methodology

The analysis is based on the Representative Audit of Britain (RAB)Footnote1 survey, an original individual-level survey data of all candidates standing in the UK General Elections of 2019. The survey included one wave of printed questionnaires in May and June 2020, followed by several e-mail reminders. We obtained an overall response rate of 36% (N=1162). The response rate is very similar between men and women (36%), 40% among non-incumbents and lower among incumbent MPs (18%). Results are weighted by the party (Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020).

The survey included a unique battery of questions specifically designed to capture the experiences of harassment and intimidation, the specific political and gendered nature of the incidents and other politically relevant information. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the most comprehensive survey of this kind applied to parliamentary candidates in the UK. The vote share of the candidate comes from the British Election Survey (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2017).

We used two analytic approaches to identify patterns in our data. First, we provide information on the distribution of individual responses for harassment and types of harassment, identifying overarching patterns in individual responses. In our second set of analyses, we relied on a path analysis estimated with a generalized structural equation model (GSEM). Since the variables included in the model present different levels of measurement, we considered this to be preferred over a simple SEM model, more suitable to fit linear models with continuous variables. Using GSEM models also represent the advantage of using a method that fits the theory. Because factors determining the likelihood of harassment are also determinants of electoral success it can be hard to separate what is causing the outcome. Structural equation modelling enables a model relating the various factors to be tested for its fit to the data, determining if it is the visibility of the candidate or its reaction to the abuse that drives the electoral outcome (Gorrell et al. Citation2018).

Variables

The main outcome variable of the model is the share of votes obtained by a candidate. The reason why we are using vote share is because of the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system used in the UK and to account for different constituency sizes and populations. Some constituencies are labelled as “safe” seats as they normally don’t change hands between parties after an election takes place. However, safe constituencies are sometimes used by other parties to test the performance of “apprentice” candidates. For example, a Conservative candidate standing in a safe Labour constituency who can reduce the margin of victory separating both parties may enhance their chances of being selected for a winnable seat at a future General Election. Likewise, a candidate standing for a smaller party who takes a large share of votes from the main parties can be considered successful as, from the beginning, their chances of winning the seat have been negligible. Thus, we consider that vote share is a better measure of electoral success than other measures like winning or not a seat.

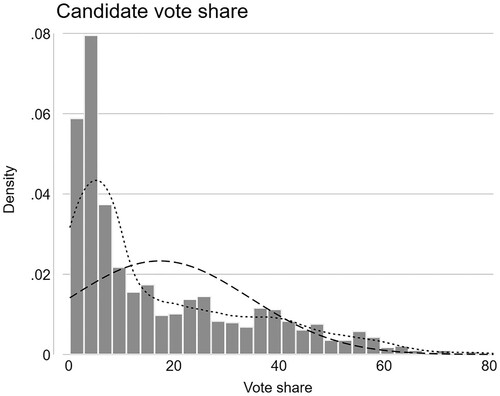

The variable range goes from 0 to 100. It has an unweighted mean of 15.5 and a standard deviation of 16.85. The minimum and maximum values observed in the sample are 0.19 and 80.77. It is heavily skewed to the left, as demonstrated in below.

Figure 1. Distribution of outcome variable. Source: Own analysis based on Fieldhouse et al. (Citation2017).

Explanatory variables include whether the candidate declared or not to have experienced some form of harassment, intimidation or threats to their security while campaigning for the 2019 General Election.

Changes in campaign style: We asked candidates whether they have modified their campaign strategy as a result of the harassment. We are measuring this with three survey items provided by their response to the question: Which, if any, of the following things have you done during the 2019 General Election campaign for reasons of personal security? Avoided canvassing voters, avoided going to political meetings or rallies and avoided using online media, like Twitter (all recoded to Yes/No).

Sex of the candidate is a binary bvariable coded 0 if canidates self identify as men and 1 for candidates who self identify as women. We established men as the baseline for comparision to be able to detect if the experiences of women are significantly different to those experienced by men.

Other control variables included in the model consist of demographics (age and whether they declare to have a disability, being from an ethnic minority background or belonging to the LGBT+ community), their party and ideology (left/ right) and their condition as incumbent MP or not. We also included a variable indicating if the candidate is competing in a “safe seat”, defined as a seat previously won by the same party with a majority larger or equal than 10%.

Descriptive results: the gendered nature of harassment in the UK

Following the approach used by Collignon and Rüdig (Citation2020), we compared the frequency of harassment declared as such by respondents. This is, the frequency of experiences that they will openly label as harassment. The analysis of RAB 2019 responses indicates that 49% of candidates suffered from some form of harassment or intimidation while campaigning. This is an increase of 11 percentage points compared with 2017 when 38% of the candidates answered positively to the same question (Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020).

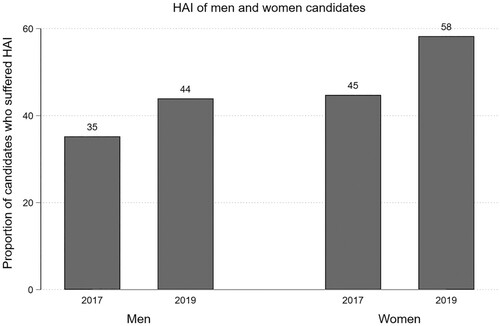

A simple cross-tabulation with a Pearson’s χ2 test show that women are being particularly targeted and that the gap between men and women is increasing. In 2017 45% of female candidates suffered harassment and intimidation, compared with 35% of males (p<0.05). In 2019 the proportions were significantly larger, 44% of men and 58% of women were abused in some form. It is particularly worrying to observe that harassment against women increased by 13 percentage points ().

Figure 2. Harassment during UK electoral campaign. Source: Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020; Representative Audit of Britain 2017, 2019.

Comparing responses to the same question between 2017 and 2019 gives us a good opportunity to get some understanding of how the issue evolved between elections. However, it is contingent on what the social understanding of the term harassment is. Therefore, responses may refer only to widely recognized forms of abuse or other more subtle experiences (Bufacchi Citation2005). Individuals may consider the word too strong to be used to refer to, for example, abusive emails or abuse on social media (Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020) which may reflect gendered differences of what is understood and socially recognized as abuse (Bjarnegård Citation2018). To circumvent this issue, we also asked candidates to indicate the kind of abuse they suffered, what was the content or intention, and the kind of perpetrator.

We find that men are significantly more likely to be physically assaulted than women (6 and 3%, respectively) but women are significantly more likely to be targeted in almost all other categories. in the appendix offers a detailed breakout of the types of harassment experienced by candidates -men and women-. The five most frequent include abuse on social media (Twitter, Facebook etc) (54% of women and 40% of men candidates); inappropriate emails (42% and 31%); unwanted approaches (32% and 22%); threats of harm (23% and 16%) and inappropriate letters (18% and 15%). All these forms of abuse can be understood as part of a continuum of violence (Kelly Citation1988; Krook Citation2020), if we take at all possible expressions of violence, we see that the proportion of candidates who suffered from some form of abuse, harassment or intimidation in the UK 2019 GE goes up to 58% and that the proportion is again, significantly higher for women (67%) than men (54%).

As we noted in the theory section, the content of the threat and its intention is important to define the gendered nature of the political violence observed. 73% of the sample indicated that they have suffered harassment at the hands of supporters of other parties or candidates. The proportion is significantly larger for women (83%) than it is for men (68%). Women are also targeted by angry members of the public, blaming politics or politicians for their problems (83% of women 71% of men). We do not find any evidence suggesting that women are targeted by individuals presenting signs of delusion obsession, incoherence, paranoia or other behavioural disorders (49% of woman and 43% of men).

Related to the source of harassment, 62% of women experience prejudice against women, misogyny (compared with 12% of men). Women are also more likely to suffer racism (34% women and 21% men), anti-Semitism (17% women and 13% men), ableism (17% women and 10% men) and right-wing radicalism (47% of women and 32% of men) and to be harassed by Brexit supporters (64% of women and 42% of men). Women also face Islamophobia (26% women and 21% of men), homophobia (26%), left-wing radicalism (44%) and are harassed by Remain supporters (41%) but no statistical evidence of targeting was found here.

As a result, women felt significantly more unsafe than men, scoring 4 and 2.7 respectively on a scale that goes from 0 (safe) to 10 (unsafe). They also express significantly higher levels of fear, 71% of women indicated to feel fearful during the campaign compared with 45% of men.

Finally, we asked candidates if, for reasons of their security, they avoided going to political meetings or rallies, avoided canvassing voters or avoided using social media like Twitter or Facebook. We find that overall, 15% of candidates avoided going to political meetings of rallies, 20% avoided canvassing voters and 31% avoided using social media during the campaign. Unsurprisingly since women feel more unsafe than men, are significantly more likely to avoid such activities as a result of concerns for their safety. in the appendix presents a detailed breakdown by sex.

Statistical analysis: the gendered impact of the abuse

Moving forward, we show that the relationship between harassment and electoral success is not direct and straightforward. We first fitted a log-linear model using the logarithmic transformation of the share of votes. We used the logarithmic transformation because the variable is heavily skewed to the left and can only present values that are larger than 0.

The first model in indicates that candidates who were harassed, intimidated or abused on any form during the campaign obtained on average, 51% more votes than candidates not harassed, it also indicates that women get, on average, 16% larger vote share than men. This would (misleadingly) indicate that harassment improves the chances of electoral success.

Table 1. Coeffects and standard errors from log-linear and binary regressions.

In terms of other demographics, we observe the expected relationship between control variables and vote share. Each point closer to the right brings candidates an increase in vote share of 6% (note this will be in line with the landslide victory of the Conservative Party in 2019) and being the incumbent MP significantly increases the share of votes by 102%. Candidates with a disability have a significantly harder time increasing their vote share (having a disability decreases vote share by 23%). These relationships hold even if we control for party and the type of seat the candidate is standing for (candidates in safe seats get on average 58% more votes). Age, ethnic background and sexual identity (LGBT+) do not show a significant relationship with vote share. Looking at the outcomes of model 1 leads to the impression that harassment increases electoral success. But, as discussed in the theory section, this relationship can be spurious, motivated by a problem of endogeneity. To show this, the second model in the table switches the predictors in a logistic regression to predict harassment using a model similar to that of Collignon and Rüdig (Citation2020). It can be appreciated there that vote share is a significant predictor of harassment, which is consistent with previous findings that the competitiveness and visibility of a candidate make them more prone to abuse (Håkansson Citation2021; Herrick et al. Citation2019; Collignon and Rüdig Citation2020) and more likely to win. Together, models in show that there is a problem of endogeneity, as harassment predicts vote share and vote share predicts harassment, suggesting that a more careful approach needs to be taken to test the effect that harassment has on the electoral success of women standing for office in the UK before we reach any valid conclusions.

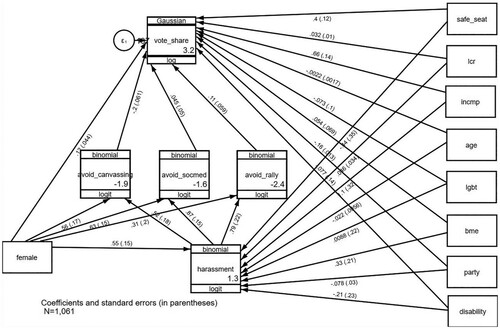

To deal with the problem of endogeneity and provide evidence of the causal mechanism proposed, we fitted a GSEM model with vote share as the main outcome variable but mediating the effect of harassment on vote share by the decision to avoid rallies, canvassing or campaigning on social media. presents graphically a GSEM model with the coefficients and standard errors linking outcome and explanatory variables. presents the results in full detail.

Figure 3. Coefficients and standard errors (in parentheses) of GSEM model. Source: Representative Audit of Britain 2019.

Table 2. Coefficients and t-statistics of GSEM model explaining vote share.

Our results from the first direct model indicate that sex (female), ideology, incumbency and safety of the seat are still predictors that directly significantly increase vote share. Candidates standing in safe seats get, on average almost 40% larger vote share than candidates standing in unsafe seats. LGBTQ+, BAME, disability and age do not play a significant role to predict vote share.

On the other hand, the second direct model indicates that incumbent MPs, are more likely to be harassed, again suggesting that the visibility of the candidate may play a role in driving harassment. Our results corroborate that women and young candidates are significantly more likely to be harassed than men and older candidates. Ideology, ethnicity, disability and sexual identity are variables that do not significantly affect the likelihood of harassment in the sample. Results from the GSEM models are in line with what was observed in the models presented in , increasing our confidence in the results.

The argument we made is that the impact on harassment in electoral success is indirect and that harassment will decrease electoral success by forcing women to modify their campaign behaviour. Thus we mediated the effect of harassment by the decision to change their campaign activities. We find that women candidates are significantly more likely to modify their campaign behaviour as a result of experiences of abuse, harassment and intimidation as shown by the significant and positive coefficients of being female on the likelihood to avoid canvassing and social media, providing support for H1. Women are as likely as men are to avoid ralies.

Looking at the direct relationship between such behaviours and vote share (first direct model) and we find that candidates who avoid canvassing reduce their vote share by about 20%. Since women are significantly more likely to avoid canvassing as a result of harassment, we can say that by forcing them to modify their campaign strategy or behaviour, harassment affects the electoral success of women, providing general support for H2 and H2a. We find no evidence of a direct effect between reducing social media and rallies and vote share, as suggested by H2b. One reason is that canvassing is more strongly directly linked to the constituency where they stand than social media and rallies.

In sum, our results show that women react differently than men to harassment and modify their campaign behaviour in a manner that is detrimental to their success. Our measure of harassment puts together different forms of violence under the assumption that it is the perception of a threat that motivates individuals to change behaviour. Women in the UK do suffer significantly more abuse of almost any form -online, physical or physicological-, than men and in consequence present higher levels of fear and feelings of unsafety. As a reaction, they modify their campaign strategy, avoiding engaging in activities that are important for their success.

Conclusions

The issue of the harassment and intimidation of women in politics in the UK is a source of concern for the quality of public life and descriptive representation of women in the country. The generalized feelings of unsafety and fear among female candidates suggest that women in politics in the UK are subject of violence (Bjarnegård Citation2018; Bjarnegård Citation2018; Krook Citation2020). But is this violence gendered?

We find evidence that the abuse suffered by women in politics in the UK indeed leads to gendered outcomes. Using data from an original survey applied to all men and women candidates standing in the 2019 General Election in the UK, we provided evidence showing that the relationship between harassment and electoral success is not always easy to observe, as confounding factors such as candidate visibility in the race can affect empirical results. We then showed that the abuse suffered by women in politics impacts the representation of women because it makes it more difficult for them to get elected by forcing them to modify their campaign behaviour in meaningful ways. In other words, we find that when women run for office, they win, but at a higher cost from doing it (Hayes and Lawless Citation2016), and harassment is one such cost. Therefore, harassment indeed represents an obstacle to gender equality and representation because it makes it more difficult for women to get elected.

There are some reasons why women may change their campaign strategies as a result of harassment while men may not. One of them relates to the notion that men and women suffer from different forms of violence, and that women are more likely to know the perpetrator and suffer from physicological violence (Bjarnegård Citation2018). This in turn motivates stronger feelings of anxiety, concern and fear, leading them to feel considerably more unsafe. Psychology literature has shown that feelings of safety lead individuals to change behaviour (Lerner et al. Citation2015), and in the case of women, this manifests by changing campaigning behaviour and avoiding threatening situations. Meanwhile, men are more likely to suffer from physical and fatal violence by the hand of unknown perpetrators (Bjarnegård Citation2018), but these incidents are so rare in the UK that men candidates may not have this worry at the top of their minds.

Of course, women may design their campaigns in a different way than men in the first place. However, what we have shown in the first part of this analysis, is that the visibility of a women candidate attracts significant abuse. Thus, when women do well in an electoral campaign, harassment and intimidation are used to punish them for their success. This is, harassment forces women to make an important choice, either adapt their strategy and jeopardize the outcome, or campaign in fear.

Overall, harassment increased in the 2019 General Election compared with 2017 and the speed at which it increased for women is twice as fast as that of men. Feelings of fear and unsafety are also on the rise. Women are particularly targeted by angry members of the public blaming politics and politicians for their problems and by supporters of other parties and candidates. One reason behind these dynamics may be found in the type of party women are standing for. The Labour Party in the UK became in 2019 the first party proposing more women than men candidates. This is the result of a long-term commitment to improving the descriptive representation of women achieved by nominating women in winnable situations and All-Women Shortlists. Such affirmative actions have proven controversial among party supporters and voters in general but have had the desired effect of increasing by more than 50% the number of Labour Women MPs (Wäckerle Citation2020). However, these actions may as well have motivated a backlash to penalize women and their party from “going too fast”, challenging the existing status quo of male-dominated politics (Krook Citation2020).

It is important to recognize that women are not a homogeneous group. Women standing from different parties have distinctive expectations and opinions, and at the same time, they are subject to different expectations and biases. Women on the left and right in the political spectrum are frequent victims of harassment and intimidation but our findings indicate that they suffer from significantly more right-wing radicalism. This can be driven by their condition as women and the kind of policies they advocate, specifically related to issues of redistribution and equality associated with the left (as more women stand for the Labour party than the rest) and opposition to Brexit.

It is no secret that in the last decades, a surge in populism has made it popular to advocate for a return to “traditional values” which include strict ideas of what the specific role of women in society is. Women and in particular women from ethnic minorities are seen as a threat to these values and views and a reason for the disenfranchizing of white-working class men. Thus, it is not possible to completely disregard the idea that violence against women in politics in the UK may be motivated or facilitated by a rise of populist politics. This is an important issue that should be tackled by future research.

This article is a first step in the study of direct and indirect outcomes of harassment and intimidation in public life. At this stage, we cannot say whether violent/abusive experiences diminish the willingness to stand for office but the possibility raises serious questions about the quality of future representation. In particular, as harassment increases the barrier of women to achieve office and recruitment and motivation have already been identified as a key barrier for female descriptive representation (Fox and Lawless Citation2010; Lawless Citation2012). Future research is urgently needed in this direction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Representative Audit of Britain 2019 project is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), PI Professor Rosie Campbell (King’s College London), ES/S015728/1.

References

- Adams, S. J., T. E. Hazelwood, N. L. Pitre, T. E. Bedard, and S. D. Landry. 2009. “Harassment of Members of Parliament and the Legislative Assemblies in Canada by Individuals Believed to Be Mentally Disordered.” Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology 20 (6): 801–814.

- Akhtar, S., and C. M. Morrison. 2019. “The Prevalence and Impact of Online Trolling of UK Members of Parliament.” Computers in Human Behavior 99: 322–327.

- Ballington, J. 2018. “Turning the Tide on Violence against Women in Politics: How Are We Measuring Up?” Politics and Gender 14 (4): 695–701.

- Bardall, G. 2020. “An Overview of Policy Responses and Solutions to Violence against Women in Politics.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 3 (2): 299–301.

- Bardall, G., E. Bjarnegård, and J. M. Piscopo. 2020. “How is Political Violence Gendered? Disentangling Motives, Forms, and Impacts’.” Political Studies 68 (4): 916–935. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719881812.

- Bjarnegård, E. 2018. “Making Gender Visible in Election Violence: Strategies for Data Collection.” Politics and Gender 14 (4): 690–695.

- Bjarnegård, E. 2021. “The Continuum of Election Violence: Gendered Candidate Experiences in the Maldives.” International Political Science Review. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120977111.

- Bjarnegård, E., S. Håkansson, and P. Zetterberg. 2020. “Gender and Violence against Political Candidates: Lessons from Sri Lanka.” Politics and Gender 1–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000471.

- Bufacchi, V. 2005. “Two Concepts of Violence.” Political Studies 3 (2): 3193–3204.

- Campbell, R., and P. Cowley. 2014. “What Voters Want: Reactions to Candidate Characteristics in a Survey Experiment.” Political Studies 62 (4): 745–765.

- Chadwick, A., and J. Stromer-Galley. 2016. “Digital Media, Power, and Democracy in Parties and Election Campaigns: Party Decline or Party Renewal?” The International Journal of Press/Politics 21 (3): 283–293.

- Childs, S., and P. Cowley. 2011. “The Politics of Local Presence: Is There a Case for Descriptive Representation?” Political Studies 59 (1): 1–19.

- Collignon, S. 2019. “Election 2019: Analysis Shows Increase in Women MPs but Most Are in Opposition.” The Conversation. December 20. https://theconversation.com/election-2019-analysis-shows-increase-in-women-mps-but-most-are-in-opposition-129043.

- Collignon, S., J. Sajuria, and W. Rüdig 2019. “A Comparative Approach to Harassment and Intimidation of Parliamentary Candidates.” Paper Presented at APSA General Conference 2019.

- Collignon, S., R. Campbell, and W. Rüdig. 2021. The gendered Harassment of Parliamentary Candidates in the UK. Oxford Rountable on Violence Against Women in Politics.

- Collignon, S., and W. Rüdig. 2020. “Lessons on the Harassment and Intimidation of Parliamentary Candidates in the United Kingdom.” The Political Quarterly 91 (2): 422–429.

- Collignon, S., and J. Sajuria. 2018. “Local Means Local, Does It? Regional Identification and Preferences for Local Candidates.” Electoral Studies 56: 170–178.

- Delisle, L., et al. 2019. “A Large-Scale Crowdsourced Analysis of Abuse against Women Journalists and Politicians on Twitter.” 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2018), Montreal, Canada.

- Every-Palmer, S., J. Barry-Walsh, and M. Pathé. 2015. “Harassment, Stalking, Threats and Attacks Targeting New Zealand Politicians: A Mental Health Issue.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 49 (7): 634–641.

- Fieldhouse, E., J. Green., G. Evans., H. Schmitt, C. van der Eijk, J. Mellon, and C. Prosser 2017. British Election Study 2019 Constituency Results File, version 1.0.

- Fisher, J., D. Cutts, and E. Fieldhouse. 2011. “The Electoral Effectiveness of Constituency Campaigning in the 2010 British General Election: The ‘Triumph’ of Labour?” Electoral Studies 30 (4): 816–828.

- Fisher, J., D. Cutts, E. Fieldhouse, and B. Rottweiler. 2019. “The Impact of Electoral Context on the Electoral Effectiveness of District-Level Campaigning: Popularity Equilibrium and the Case of the 2015 British General Election.” Political Studies 67 (2): 271–290.

- Fisher, J., and D. Denver. 2009. “Evaluating the Electoral Effects of Traditional and Modern Modes of Constituency Campaigning in Britain 1992-2005.” Parliamentary Affairs 62 (2): 196–210.

- Fisher, J., E. Fieldhouse, R. Johnston, C. Pattie, and D. Cutts. 2016. “Is all Campaigning Equally Positive? The Impact of District Level Campaigning on Voter Turnout at the 2010 British General Election.” Party Politics 22 (2): 215–226.

- Fox, R. L., and J. L. Lawless. 2010. “If Only They’d Ask: Gender, Recruitment, and Political Ambition.” The Journal of Politics 72 (2): 310–326.

- Gerber, A. S., and D. P. Green. 2000. “The Effects of Canvassing, Telephone Calls, and Direct Mail on Voter Turnout: A Field Experiment.” American Political Science Review 94 (3): 653–663.

- Gorrell, G., M. E. Bakir, I. Roberts, M. A. Greenwood, and K. Bontcheva. 2021. “Which Politicians Receive Abuse? Four Factors Illuminated in the UK General Election 2019.” EPJ Data Science 9 (1): 18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-020-00236-9.

- Gorrell, G., M. A. Greenwood, I. Roberts, and D. Maynard. 2018. “Twits, Twats and Twaddle: Trends in Online Abuse towards UK Politicians.” 12th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, ICWSM 2018. 2017 (Icwsm), 600–603.

- Greenwood, M. A., M. E. Bakir, G. Gorrell, X. Song, I. Roberts, and K. Bontcheva. 2019. Online Abuse of UK MPs from 2015 to 2019: Working Paper.

- Håkansson, S. 2021. “Do Women Pay a Higher Price for Power? Gender Bias in Political Violence in Sweden.” Journal of Politics 83 (2): 515–531.

- Hayes, D., and J. Lawless. 2016. Women on the Run: Gender, Media, and Political Campaigns in a Polarized Era. Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Herrick, R., and L. D. Franklin. 2019. “Is it Safe to Keep This Job? The Costs of Violence on the Psychological Health and Careers of U.S. Mayors.” Social Science Quarterly 100 (6): 2047–2058.

- Herrick, R., S. Thomas, L. Franklin, M. L. Godwin, E. Gnabasik, and J. R. Schroedel. 2019. “Physical Violence and Psychological Abuse against Female and Male Mayors in the United States.” Politics, Groups, and Identities. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2019.1629321.

- Herrnson, P. S., and J. C. Lay. 2003. “Women Running “as Women”: Candidate Gender, Campaign Issues, and Voter-Targeting Strategies.” The Journal of Politics 65 (1): 244–255.

- Hughes, M. M., P. Paxton, and M. L. Krook. 2017. “Gender Quotas for Legislatures and Corporate Boards.” Annual Review of Sociology 43 (1): 331–352.

- James, D. V., S. Sukhwal, F. R. Farnham, J. Evans, C. Barrie, A. Taylor, and S. P. Wilson. 2016. “Harassment and Stalking of Members of the United Kingdom Parliament: Associations and Consequences.” The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 27 (3): 309–330.

- Kelly, L. 1988. “How Women Define Their Experiences of Violence.” In Feminist Perspectives on Wife Abuse, edited by K. Yllö, and M. Bograd, 114–132. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Krook, M. L. 2017. “Violence against Women in Politics.” Journal of Democracy 28 (1): 74–88.

- Krook, M. L. 2018. “Westminster Too: On Sexual Harassment in British Politics.” The Political Quarterly 89 (1): 65–72.

- Krook, M. L. 2020. Violence against Women in Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Krook, M. L., and J. Restrepo Sanin. 2019. “The Cost of Doing Politics? Analyzing Violence and Harassment against Female Politicions.” Perspectives on Politics 18: 1–48.

- Kuperberg, R. 2018. “Intersectional Violence against Women in Politics.” Politics and Gender 14 (4): 685–690.

- Lawless, J. L. 2012. Becoming a Candidate: Political Ambition and the Decision to Run for Office, 279. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lerner, Jennifer, Ye Li, Piercarlo Valdesolo, and Karim S. Kassam. 2015. “Emotion and Decision Making.” Annual Review of Psychology 66 (1): 799–823.

- McLoughlin, L., and S. Ward. 2017. “Turds, Traitors and Tossers: The Abuse of UK MPs via Twitter.” ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops.

- Perraudin, F., and S. Murphy. 2019. “Alarm over Number of Female MPs Stepping Down after Abuse.” Women in politics.

- Piscopo, J. 2016. “Capacidad estatal, justicia criminal y derechos políticos: Nueva mirada al debate sobre la violencia contra las mujeres en política.” [State Capacity, Criminal Justice, and Political Rights: Rethinking Violence against Women in Politics]. Política y gobierno 23 (2): 437–458.

- Southern, R., and E. Harmer. 2021. “Twitter, Incivility and “Everyday” Gendered Othering: An Analysis of Tweets Sent to UK Members of Parliament.” Social Science Computer Review 39 (2): 259–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319865519.

- Wäckerle, J. 2020. “Parity or Patriarchy? The Nomination of Female Candidates in British Politics.” Party Politics, 1–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820977242.

- Zittel, T., and T. Gschwend. 2008. “Individualised Constituency Campaigns in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems: Candidates in the 2005 German Elections.” West European Politics 31 (5): 978–1003.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics (unweighted).

Table A2. Response rate by party.

Table A3. Types of harassment during 2019 GE campaign (weighted).

Table A4. Proportion of candidate that modified their behaviour as a result of harassment.