ABSTRACT

Previous studies have investigated to what extent voters can achieve proximity between their preferences and the positions of the party they vote for. Combining data from the European Social Survey and the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, we investigate whether trust in political parties increases ideological proximity voting. We argue that voters use their level of trust in parties as a heuristic mechanism. First, trust can increase proximity voting because citizens need to trust that political parties will take voters’ policy preferences into account when in government. Second, we examine whether low-trusting voters tend to cast a protest vote, and do not engage in ideological proximity voting. We test this assumption regarding three determinants of the vote choice: general left-right ideology views, preferences for income redistribution, and anti-immigrant sentiments. We find that ideological proximity voting is indeed moderated by trust: those who trust political parties are more likely to cast a vote based on their policy preferences, while those who distrust tend to vote for protest parties. Nevertheless, also among protest voters, trust is conducive for higher levels of proximity voting.

Introduction

The assumption that citizens vote according to their ideological positions on important policy issues is well established in the political science literature. Ideological proximity voting is crucial to ensure the representativeness of democratic elections, where voters are expected to have positions on multiple policy issues and to vote for a political party that is in line with their positions (Powell Citation2000): only if there is a strong correlation between the position of voters and the parties they vote for, it can be assumed that elections are a prime tool to reveal the political preferences of the population (Golder and Stramski Citation2010).

Various determinants of ideological proximity voting have already been investigated, with their focus being either on the characteristics of the individual voter, or the electoral system (Lau et al. Citation2014). On the individual level, it has been shown that sophisticated and motivated voters are more likely to vote based on their policy preferences (Dassonneville et al. Citation2020; Lau et al. Citation2014). On an institutional level, a good deal of attention has been given to how the political information environment, like having a multiparty system, a fragmentized media system, or compulsory voting, facilitates proximity voting (Dassonneville et al. Citation2019; Hooghe and Stiers Citation2017; Lau, Andersen, and Redlawsk Citation2008; Lau et al. Citation2014).

We argue that previous research investigating voters’ motivation and ability to cast an ideological proximity vote, did not pay sufficient attention to an important aspect of proximity voting: voters’ perceptions of the trustworthiness of political parties. We assume that voters will put more effort into casting an ideological proximity vote if they trust political parties. The key point is that when political parties are perceived as responsive to the wishes of citizens, citizens will be more likely to cast a vote in line with their own political preferences. Trust in parties can thus be used as a heuristic by citizens for the extent to which parties will take the electoral signal into account.

Two conditions are crucial for ideological proximity voting. First, it has to be assumed that political parties are “sincere”, i.e. that on average, parties and politicians will put an honest effort to fulfil their campaign pledges (Stiers et al. Citation2021). The literature on the fulfilment of electoral pledges suggests that political parties indeed try to implement their promises, even if this effort is not necessarily successful. It also suggests that parties who are more successful at implementing their promises, are rewarded in subsequent elections (Matthieß Citation2020). Second, it is equally important that voters see this effort and believe that parties can be trusted with the mandate they receive. When trust is absent, we can assume that voters will not bother to cast an ideologically coherent vote, and turn to protest parties instead (Dalton and Weldon Citation2005). Hence, citizens rely on their trust perceptions to assess political parties through a dual screening mechanism: while trusting citizens vote for a party closest to them, low-trusting citizens are more likely to turn to anti-establishment parties as a form of a protest vote, thereby lowering the congruence of their vote.

We test whether citizens achieve higher levels of ideological proximity voting when they believe that political parties are trustworthy. To do so, we combine the European Social Survey (ESS), which contains information on respondents’ vote choices, political preferences, and trust in political parties, with data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), which has information on parties’ ideological positions on policy issues. In the literature, various suggestions have been made on how best to operationalize ideological proximity voting (Lau and Redlawsk Citation1997, Citation2006). We follow Dassonneville et al. (Citation2019) as we measure the correspondence between voters’ preferences on specific topics, and the position of the party they voted for (Hooghe and Stiers Citation2017; Wagner, Johann, and Kritzinger Citation2012). We focus on the general ideology of citizens, and their preferences on two specific issues, i.e. their preferences regarding economic redistribution, and immigration attitudes. The results of the analyzes provide corroborating evidence for our hypotheses: citizens with higher levels of trust in parties, are more likely to vote in an ideologically consistent manner, and low-trusting citizens vote for protest parties. However, protest party voters with higher trust in parties, are also more likely to cast an ideologically proximate vote.

Theory: why trust in parties should matter for ideological proximity voting

Elections are the cornerstone of representative democracy, as they allow citizens to express their political preferences. To enable effective representation, it is important that political parties act upon the signal sent by the electorate through elections and link the political preferences of the voters with their actions or policy outcomes (Manin Citation1997). Building on Lau and Redlawsk’s (Citation1997, Citation2006) work, we argue that for effective representation to occur, not only high levels of electoral turnout matter, but also the extent to which voters cast votes in line with their political preferences (Lau, Andersen, and Redlawsk Citation2008). Even in cases of high turnout, if all voters would cast a vote randomly, or spoil their ballots, the elections would not provide much information about the policy preferences of the electorate (Lau et al. Citation2014). Therefore, for democracies to function well, citizens should cast a vote in line with their own values, and political beliefs (Lau and Redlawsk Citation1997).

Our conceptualization of ideological proximity voting builds on two distinct elements: political parties and voters. Political parties play a crucial role in linking citizens’ preferences to the political decision-making process. Parties are expected to provide the electorate with policy programmes, on which they compete with each other. When in government, parties use governing bodies to implement those programmes (Mair Citation2006; Powell Citation2004). The closer voters’ political preferences resemble those of the parties they voted for, the more responsive political institutions can be, and the more effective democracy works (Powell Citation2004; Stiers and Dassonneville Citation2019).

This leads to the second political actor in proximity voting: the voters. The literature on ideological proximity voting has pointed out that, even though most voters cast a vote for parties that represent their political preferences fairly accurately (Dassonneville et al. Citation2020; Green and Jennings Citation2017; Lau et al. Citation2006; Lau and Redlawsk Citation1997, Citation2006; Stubager and Slothuus Citation2013), it is less clear how exactly they make this decision. Spatial theories on voting behaviour rely on past experience as a possible mechanism, where over time, voters recall which party is typically closest to them, as they develop a party attachment on the basis of their preferences (Downs Citation1957).

However, past experiences with political parties can also produce a sense of trust or distrust in parties. Trust is a characteristic of relations, which has subjects (in this case voters), objects of trust (here: political parties) and expectations about what that object of trust should do (Bertsou Citation2015; Braithwaithe and Levi Citation1998). Trust in parties can be seen as an evaluative judgement of citizens, based on the perceived responsiveness and reliability of parties (Citrin and Stoker Citation2018; Dalton Citation2004; Dalton and Weldon Citation2005; Hetherington and Husser Citation2012; Hooghe and Okolikj Citation2020; Levi and Stoker Citation2000).Footnote1 Hence, trust in political parties depends on citizens’ expectations that what is promised during the campaign will be delivered when that party gets elected, or at least that there will be an attempt to deliver on the election pledges. It should be noted that by using this definition, we firmly situate ourselves in the research tradition that citizens are critical trusters, i.e. that their trust depends on the behaviour of specific institutions, rather than on the innate trusting nature of citizens (Van der Meer and Ouattara Citation2019; Wu and Wilkes Citation2018).

Trust in parties potentially has important ramifications for ideological proximity voting, since trust can be used by citizens to predict future behaviour of parties as a heuristic. Indeed, if parties were unreliable in the past (leading to low trust), why would they be reliable in the future (Fiorina Citation1981; Hetherington Citation2005; Hetherington and Rudolph Citation2015)? In reality, trust in political parties is quite low in Western democracies (Dalton and Weldon Citation2005; Kim Citation2007), and it should be highlighted that trust in parties is usually even lower than trust in other political institutions, corroborating the critical truster approach (Hooghe and Okolikj Citation2020; Kim Citation2007; Zmerli and Hooghe Citation2011). This is an additional reason to further study the consequences of levels of trust in parties as a heuristic specifically (rather than trust in general) on citizens’ vote choices and the functioning of electoral democracies.

We argue that citizens who think that political parties are untrustworthy have fewer incentives to vote based on policy preferences. If one does not trust that political parties will implement what they stand for, ideological proximity voting becomes less salient. In contrast, when citizens trust parties and believe that these parties will take on voters’ signals to develop future policy, they will be encouraged to send strong policy signals with their vote. This argument is in line with the broader literature on the use of political trust as a heuristic, i.e. as a cognitive shortcut to make difficult political decisions (Hetherington Citation2005; Hetherington and Husser Citation2012; Rudolph Citation2017).

We expect this association to occur regardless of the political orientation of citizens, as both left- or right-leaning citizens can express political (dis)trust. Moreover, if citizens overall distrust parties, they will make less of an effort to compare party programmes across different parties. Hence, trust in parties should steer voters towards ideological proximity voting:

Hypothesis 1: The ideological proximity vote is stronger for voters with a higher level of trust in political parties than for voters with lower levels of trust in parties.

This dilemma may drive distrusting voters to cast a vote for parties that are not necessarily closely representing their ideological preferences in order to express their discontent. Hence, our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Citizens with low levels of trust in parties are more likely to cast a protest vote.

Before going into the more specific issues, a note needs to be made about the association between trust in parties, ideological proximity voting, and turnout. In most countries, citizens who do not trust parties also have the option to abstain from voting, and one could wonder why someone not trusting parties would turn out to vote (Dalton and Weldon Citation2005). Indeed, our analyzes show a significant positive association between trust in political parties and self-reported turnout in the last national election (see Appendix C). To some extent, this behaviour fits our theoretical mechanism: self-evidently, if low trust in parties leads citizens to abstain from voting, they also do not signal their policy preferences, further decreasing the overall representativeness of the electoral result. We would like to highlight that there are many other reasons for turnout among low-trusting voters, such as citizens’ feeling of duty to vote (Blais Citation2000), due to a strategic, instead of a sincere vote (Cain Citation1978), or as a way to ventilate their discontent by casting a protest vote (as hypothesized) (Bélanger Citation2017). In this study, we focus on what happens at the voting booth, i.e. among those citizens that do make the effort to vote.

Data and methods

In order to test our hypotheses, we combine information about the position of political parties by using the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, with information about citizens’ political attitudes and their vote choice through the European Social Survey. For individual-level analyzes, the ESS is an ideal source as it asks the same questions across various countries and years. For our party-level data, the CHES uses expert surveys to judge political parties’ positions on different issues, which is consistently done across years as well. We match the position of political parties from the CHES, with the reported vote choice from the respondents in the ESS. Since the political parties included in the ESS self-evidently are the same as the political parties measured in the CHES, we were able to match the political parties in the two datasets. We were able to identify and match three comparable cross-national survey years from these two datasets, conducted in the same years and providing us with three consecutive time points: 2006, 2010, and 2014. The CHES overlaps in these time periods with ESS information on 21 European countries, which allows us to match and include j = 56 national surveys in total, with i = 62,548 individual observations.

To test hypothesis 1, we focus on three different measures of political preferences. First, we use the general left-right continuum, measured on a 0–10-scale where 0 refers to the ideological left and 10 to the ideological right. This general ideological measure suits our purposes of modelling proximity voting well: as a “super issue” it encapsulates cleavages salient to voters at a certain point in time (Van der Eijk, Schmitt, and Binder Citation2005), and it has been shown that voters’ perceptions of left and right are comparable to those of experts – which we use here (Dalton, Farrell, and McAllister Citation2011). This measure hence allows us to calculate a direct difference score to be able to model proximity voting (see Dassonneville et al. Citation2019; Hooghe and Stiers Citation2017) (for a full description of the variables see Appendix A; for descriptive statistics, see Appendix B).

After testing proximity voting using this broad ideological continuum, we focus on two of the most salient issues in contemporary elections: (1) positional economics, with a focus on income redistribution (Lewis-Beck, Nadeau, and Foucault Citation2013; Quinlan and Okolikj Citation2020), and (2) attitudes toward immigration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). We measure views towards the economy with the question in the ESS using a five-point scale: “Government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels”. Those who strongly agree with this statement were coded 1 and those who have strong opposing views were coded 5. We expect that respondents that report a preference for higher levels of income redistribution, vote for a party with similar policy positions. Second, we focus on an important new cleavage, that is based on libertarian versus authoritarian values. Kriesi et al. (Citation2012) have argued that the issue of globalization, which manifests itself through immigration preferences, has become an important cleavage in electoral politics. We measure anti-immigration sentiments using a composite score of three questions asked in the ESS. Respondents were asked to indicate their views on what effect immigration has on (a) the economy in their country, (b) the culture in their country, and (c) whether immigrants make their country a worse or a better place to live. All three variables load well on a unidimensional scale, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. The composite score retains the original 11-point scale of the separate questions, with 0 referring to positive attitudes toward immigration and 10 to negative attitudes towards immigration, which matches our dependent variable.

Focusing on these issues, the analysis takes several steps. First, using the general left-right continuum, we estimate a traditional proximity model by calculating the distance between the voters’ own position, and the position of the party this voter voted for (based on the CHES data). We then test whether those with higher levels of trust in parties span, on average, a smaller ideological distance with their vote. For the two more specific issues, we cannot calculate such a direct distance measure, as the scales of the ESS and CHES are not directly comparable. Therefore, we construct two additional dependent variables indicating the policy position of the party the respondent voted for – in line with the two political issues under investigation. The first dependent variable indicates the extent to which the party the ESS respondent voter for, favours (lower values on the scale) or is against (higher values on the scale) government action in reducing income differences, on a 0–10-scale (measured in the CHES). In line with our focus on immigration policy, the second dependent variable indicates an immigration policy scale of the party the ESS respondent voted for, with 0 meaning a very liberal stance toward immigration and 10 meaning being strongly against immigration. For these issues, we first test whether voters link their preferences on these issues with the party they vote for – i.e. whether the respondents’ vote is in line with their ideological position – by regressing their own opinion on the position of the party they voted for. Then, following our hypotheses, we test whether trust in political parties strengthens the level of voter-party ideological proximity by including an interaction term between the voters’ own position and their level of trust in parties.

Our main argument is that trust in political parties plays an important moderating role in ideological proximity voting. We use a standard question in the trust literature from the ESS, which asks respondents how much they trust political parties, on an 11-point scale, with 0 indicating that respondents do not trust parties at all, and 10 meaning complete trust.

To test our second hypothesis on the dual screening mechanism, we define low-trusting voters as those voters that are at least one standard deviation below the mean on the trust in parties scale (i.e. voters who scored 0 or 1 on the trust question). This amounts to about 25% of the respondents.

There are several ways in which protest voting can operationalized. In order to make a meaningful comparison between the countries and parties under study, we adopt the view that distrusting citizens protest against the current system by voting for populist or radical parties (Bélanger Citation2017; Hooghe Citation2018). Hence, we operationalize protest voting through the PopuList (Rooduijn et al. Citation2019), and the ParlGov databases. Voters of parties classified as being populist, radical left or radical right in the PopuList, and of parties scoring above 8, or below 2, on ParlGov’s left-right economy scale (0–10 point scale), were coded as protest voters. About 22% of voters are classified in this way. The dependent variable protest voting is thus having voted for a protest party (Yes = 1; No = 0).

Turning to the construction of our models, we use several standard socio-demographic and political variables to control for the possible omitted variable bias. Our socio-demographic variables include age, gender, and the level of education of respondents. We also use political interest as a control variable, as this is the only available indicator for political sophistication within the ESS questionnaire.

To account for the nested structure of our data, we use linear (H1) and logit (H2) multilevel models with random intercepts for countries and random intercepts by survey combinations in all our analyzes (Gelman and Hill Citation2007). We report three levels of clustering, where respondents are our micro-level observations, clustered by survey (level 2) and country (level 3). Uncentred data are reported. For robustness, we conducted various alternative model specifications (see Appendix D–J). In these analyzes, we include several additional control variables (e.g. income, fractionalization index, party identity), and explore alternative modelling strategies (e.g. running fixed effects models, excluding left-authoritarian voters). We also in Appendix F specifically include a complex model with several interactions simultaneously to test the robustness of our findings. We report no significant deviations from the results reported in the main empirical section.

Results: general ideology

To investigate ideological proximity voting and the moderating effect of trust in political parties, we estimate multilevel linear regression models (). The dependent variable in this first analysis denotes the distance between the voter’s position on the general left-right continuum, and the party s/he voted for in the last election.

Table 1. Ideological proximity voting.

The results in show evidence in support of our hypothesis 1, as there is a negative association between trust in political parties and the ideological distance of the vote: those who have higher trust in political parties, will span a smaller ideological distance when they cast their vote. The results in Model 2 show that this association is robust when including a set of control variables. Hence, looking at general ideology, we find support for our hypothesis that the most trustful will cast more proximate votes.

Preferences on economic redistribution, and anti-immigration sentiments

After looking at ideological proximity voting, we focus on two more specific issues: economic redistribution and immigration. The results for these two issues are summarized in . For each respective issue, the dependent variable denotes the position of the party the respondent voted for in the last election on the issue. Note that we do not estimate traditional proximity models for these two specific issues, as the measurement scale of the ESS and CHES respectively differ too much.

Table 2. Trust in parties and specific policies (economic redistribution and immigration attitudes).

In , we estimate several models to test our hypotheses using a stepwise approach. Model 1 (redistribution) and Model 4 (immigration) estimate the direct effects of opinions regarding the issues (i.e. opposing income redistribution and anti-immigrations sentiments), and trust in political parties, on the position of the party the respondent voted for regarding the issue. We find positive and significant coefficients for both issues. These results indeed show a high level of ideological proximity voting: the more opposed the voter is toward income redistribution, the more the party the respondent votes for is similarly against economic intervention by the state. In the same way, the more the respondent believes that immigration is a threat to their society, the more opposed the party this voter votes for. Furthermore, the coefficients are sizeable: for a one-unit increase on the five-point scale of redistribution, the position of the preferred party increases with 0.466; for immigration, this amounts to 0.202.

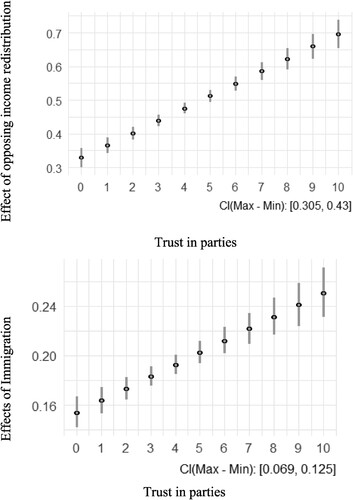

The main theoretical interest, however, is in the moderating impact of trust in political parties. To test this moderation effect, we include an interaction between trust in parties and political issues. The results are reported in Model 2 and Model 3 (redistribution) and Model 5 and Model 6 (immigration) in . The results show a clear pattern: people vote in line with their issue preference, and the significantly positive interaction coefficients show that these effects are stronger among those who have a higher level of trust in political parties. These findings provide support for our first hypothesis: the higher a voter’s level of trust in political parties, the stronger ideological proximity voting. While the coefficient of opposing income redistribution is 0.329 for the least trusting voters, it increases with 0.037 for every unit increase in trust in parties on an 11-point scale (Model 3, ). For immigration, the main effect for the voters with the lowest trust is 0.154, and this increases with 0.010 for every increase in trust (Model 6, ). To provide a full assessment of the moderating impact of trust in parties on the impact of opinions on redistribution and immigration on the ideological party vote, we plot the interactions based on this full model in .

Figure 1. Moderating effect of trust in parties on proximity voting. Note: The upper figure shows the effect of opposing income redistribution on the ideological party vote at different levels of trust in parties. Estimations based on Model 3 in . The lower figure shows the effect of immigration on the ideological party vote at different levels of trust in parties. Estimations based on Model 6 in .

The results displayed in the upper plot of visualize the effects of opposing to income redistribution. The findings show that the association is sizeable among the least trustful voters (i.e. 0.329) and becomes stronger as trust increases – up to its highest level of 0.699 for the most trusting voters. The lower plot of shows the effects of anti-immigration sentiments. For those who do not trust political parties, the effect of ideological proximity voting regarding immigration is 0.154. However, with 0.251, the average effect of ideological proximity voting is substantially larger among those that fully trust political parties. As can be seen, the effect of trust on ideological proximity voting regarding immigration policies is smaller compared to income redistribution. This might be related to the fact that most party systems that were included in the analysis are still structured more strongly among economic dimensions, while not all political parties have an equally unequivocal position regarding immigration issues.Footnote2

In sum, ideological proximity voting is an important predictor of the vote choice, tested for general ideology, economic preferences, and attitudes toward immigration. Second, trust in political parties is an important factor of ideological proximity voting that connects voters and political parties. Those who trust political parties are more likely to select a political party that matches their own policy preferences. However, proximity voting among low-trusting voters is substantially less prevalent and this requires further investigation, i.e. how do low-trusting voters express their views?

A dual screening mechanism among distrusting voters

As discussed in the theoretical section, distrusting voters are caught in the crossfire between choosing a party that is ideologically closest to them, or casting a vote for parties that promise to reform the political system. To test hypothesis 2, we examine whether low-trusting voters are indeed more likely to cast a protest vote (). We use two operationalizations of trusting voters: in model 1, those that trust parties one standard deviation below the mean are coded 1 (i.e. voters who scored 0 or 1 on the trust question), others 0. In model 2, we use the original 11-point scale of trust in parties as our independent variable. The dependent variable for both models is a vote for a protest party. In these analyzes, we further include ideology as a control variable.

Table 3. Distrust and protest voting.

We find that distrusting voters are more likely to cast a protest vote. The odds of voting for a protest party are 38.8% higher among low-trusting voters than for high trusting voters. In model 2, we show that this association remains when the original trust in parties question is used as a scale, i.e. as the level of trust increases, the likelihood of voting for an extreme party decreases.

The analyzes in lead to the question if the moderating effect of trust in parties on ideological proximity voting that we found above can, at least to some extent, be explained by the potentially longer distance that voters have to cover to cast a vote for a protest party, that have a more radical ideological profile. To control for this, repeats our original analysis conducted in and , but for two subsets of respondents, based on the vote choice, i.e. whether the respondent voted for a protest party or for another (mainstream) party.

Table 4. A test of the dual screening mechanism.

The results in point to very similar findings as those presented in and when we consider the general sample of voters who do not vote for protest parties. In this sample, trust has a significant direct effect on proximity voting, i.e. the negative sign in model 2 shows that as the level of trust increases, the distance between the ideology of the respondent and the party s/he voted for decreases. Similarly, trust has a positive and significant moderating effect on both issues, income redistribution, and anti-immigration sentiments. , however, points to interesting findings regarding the protest voters. First, protest voters are more likely to have low levels of trust in parties (see ). Second, among the protest voters, we find that trust is associated with a higher level of proximity voting (, Model 1). Finally, the models indicate that protest voters are mainly concerned about immigration. Having trust in parties increases the likelihood of protest voters casting a vote for an extreme or radical party on the immigration issue. This, however, is not very clear regarding the economic issues, where we find no evidence that trust in parties matters to protest voters. Taken together, while there is clearly an association between political trust, protest voting, and congruent voting, protest voting alone cannot fully explain the findings presented in and . Indeed, more trusting protest voters seem to be better able at identifying the party that represents their interests.

Conclusion

For representative democracies, it is essential that voters use their vote to express their opinions on important policy issues. Our study suggests that trust in parties is essential for voters to be willing and motivated to express their political preferences with their vote. More specifically, we find that political trust is an important moderator of ideologically congruent voting. Whereas all voters seem to take into account their own political interests as well as the parties’ positions when casting their vote, voters with higher levels of trust in parties do so to a larger extent – a finding that holds when investigating the general left-right continuum, opinions on economic redistribution, and attitudes on immigration. In a second step, we tested whether protest voting is the main determinant of these findings: if a distrusting voter casts a vote for a protest party to express discontent, and this party has a more extreme position on the ideological spectrum, then the voter will be forced to cast a less congruent vote according to our operationalization. The findings of the models investigating this dual screening mechanism show that distrusting voters are indeed more likely to cast a vote for a protest party. However, looking at the main mechanism under investigation, we find evidence for our argument both among protest voters as among voters for mainstream parties. As such, we think that the current literature on ideological proximity voting, that has concentrated thus far mostly on elements like political sophistication or access to political information, should also take this attitudinal moderating factor into account. In that regard, our research also contributes to the wider literature on the consequences of trust in institutions. As Van der Meer and Zmerli (Citation2017, 8) noted: “We simply lack systematic information on how much low and declining levels of political trust should be of concern to representative democracy”. Our research shows that trust in parties can have important consequences for citizens’ vote choices, and hence, the quality of democratic representation.

Self-evidently, our study is subject to some limitations. As we are analyzing cross-sectional survey data, we face limitations with regard to the potential causality of the findings, and questions we might use in our analysis. For example, we focus on general ideology and two specific issues and types of parties. Clearly, there are other issues that are important to voters. As we did not have a “most important issue”-question available, we cannot examine to what extent voters care about economic redistribution or immigration policies. While a large body of literature has shown that the cleavages these issues represent are among the main determinants of the vote (Ford and Jennings Citation2020), we cannot be fully confident that these findings would be similar for other issues. Later research could explore our hypotheses using more comprehensive measures of proximity voting.

Further, we focused on trust in parties in general, whereas some citizens might have trust in one specific party, but not in parties overall. A plausible additional scenario could be that citizens may have trust in only a specific party, or a subset of parties, which influences their vote choices. In a similar vein, citizens with more political knowledge, or that consider themselves as electoral winners, might have additional reasons to trust (specific) parties, which influences their voting behaviour too. Currently available cross-national surveys do not include such measures, which is an important data gap that future studies could mitigate. It might also be the case that having a limited set of vote options (cfr. the number of parties available in a given election), has an impact on the quality of the vote choice and trust alike. Having fewer parties in an election could lead to lower levels of ideological proximity voting, because voters often have a harder time finding a party that corresponds with their political preferences (Lau et al. Citation2014). This could lead to lower trust in parties too, because citizens cannot find a party that expresses their concerns.

A final and important limitation of the current analysis, is that we are unable to model time dynamics: to what extent are voters’ policy preferences independent of their party choice? The data do not allow us to investigate if the association uncovered is the result of the voter selecting the “correct” party, or of a “selection and adaptation” process, where citizens adjust their policy preferences to match with one’s party preference and identity. This is a highly relevant question, that future studies should further investigate.

Despite these limitations, the results hold strong implications for the way in which elections safeguard democratic representation. In terms of representation, it is essential that political parties take the voters’ signal into account. For parties to be able to be responsive to the voters’ demands, it is important that voters cast a vote for a political party that represents their political preferences. Our findings are especially important given the increasing level of political dealignment. With decreasing party attachment and a higher level of volatile voters, some authors have described these patterns as a risk for stable democratic representation (Mair Citation2006). While we do not investigate this argument directly, our results allow for democratic optimism. We find that even the least trusting voters vote according to their policy preferences, or find an outlet in protest parties. However, if parties are perceived as more trustworthy by voters, they will be more likely to show their policy preferences through their votes. Hence, it seems that, even in more volatile times in which voters move between parties, it is important that they have a basic trust in parties to be responsive towards the policy signal they send with their vote. If parties want to safeguard the representative function of elections, they need to foster trust among their voters.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Note that we investigate trust in political parties in general and our argument depends on having trust in parties overall (in the questionnaire this is referred to as “political parties”, without any further specification). If one would only have trust in one specific party, we cannot assume that higher trust would be associated with higher ideological proximity voting, as trust in just one specific party might lead to a vote for that party, even when it is not fully in line with the preferences of that citizen.

2 The findings on the basis of immigration preferences are also less robust: when restricting the ESS sample to waves held within six months after the last national election, the interaction effect is not statistically significant anymore (Appendix I). In all other robustness tests, the interaction effect remains similar and significant.

References

- Bélanger, E. 2017. “Political Trust and Voting Behaviour.” In Handbook on Political Trust, edited by S. Zmerli, and T. van der Meer, 242–255. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bergh, J. 2004. “Protest Voting in Austria, Denmark, and Norway.” Scandinavian Political Studies 27 (4): 367–389.

- Bertsou, E. 2015. Citizen Attitudes of Political Distrust: Examining Distrust Through Technical, Ethical and Interest-Based Evaluations. London: London School of Economics.

- Blais, A. 2000. To Vote or Not to Vote? The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Braithwaithe, V., and M. Levi. 1998. Trust and Governance. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Cain, B. E. 1978. “Strategic Voting in Britain.” American Journal of Political Science 22 (3): 639–655.

- Ceka, B. 2012. “The Perils of Political Competition. Explaining Participation and Trust in Political Parties in Eastern Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (12): 1610–1635.

- Citrin, J., and L. Stoker. 2018. “Political Trust in a Cynical Age.” Annual Review of Political Science 21: 49–70.

- Dalton, R. J. 2004. Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, R. J., D. M. Farrell, and I. McAllister. 2011. Political Parties and Democratic Linkage. How Parties Organize Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, R. J., and S. A. Weldon. 2005. “Public Images of Political Parties. A Necessary Evil?” West European Politics 28 (5): 931–951.

- Dassonneville, R., F. Feitosa, M. Hooghe, R. Lau, and D. Stiers. 2019. “Compulsory Voting Rules, Reluctant Voters and Ideological Proximity Voting.” Political Behavior 41 (1): 209–230.

- Dassonneville, R., M. Nugent, M. Hooghe, and R. Lau. 2020. “Do Women Vote Less Correctly? The Effect of Gender on Ideological Proximity Voting and Correct Voting.” Journal of Politics 82 (3): 1156–1160.

- Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

- Fiorina, M. P. 1981. Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ford, R., and W. Jennings. 2020. “The Changing Cleavage Politics of Western Europe.” Annual Review of Political Science 23: 295–314.

- Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Golder, M., and J. Stramski. 2010. “Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 90–106.

- Green, J., and W. Jennings. 2017. The Politics of Competence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hetherington, M. J. 2005. Why Trust Matters. Declining Political Trust and the Demise of American Liberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hetherington, M. J., and J. Husser. 2012. “How Trust Matters: The Changing Political Relevance of Political Trust.” American Journal of Political Science 45 (2): 312–325.

- Hetherington, M. J., and T. J. Rudolph. 2015. Why Washington Won’t Work. Polarization, Political Trust and the Governing Crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hooghe, M. 2018. “Trust and Elections.” In The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust, edited by E. Uslaner, 617–631. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2018. “Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset.” Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 109–135.

- Hooghe, M., and M. Okolikj. 2020. “The Long-Term Effects of the Economic Crisis on Political Trust in Europe: Is There a Negativity Bias in the Relation Between Economic Performance and Political Support?” Comparative European Politics 18: 879–898.

- Hooghe, M., and D. Stiers. 2017. “Do Reluctant Voters Vote Less Accurately? The Effect of Compulsory Voting on Party-Voter Congruence in Australia and Belgium.” Australian Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 75–94.

- Kim, M. 2007. “Citizens’ Confidence in Government, Parliament and Political Parties.” Politics & Policy 35 (3): 496–521.

- Kriesi, H., E. Grande, M. Dolezal, M. Helbling, D. Höglinger, S. Hutter, and B. Wüest. 2012. Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lau, R., D. Andersen, and D. Redlawsk. 2008. “An Exploration of Correct Voting in Recent U.” S. Presidential Elections. American Journal of Political Science 52 (2): 395–411.

- Lau, R., P. Patel, D. Fahmy, and R. Kaufman. 2014. “Correct Voting Across Thirty-Three Democracies: A Preliminary Analysis.” British Journal of Political Science 44 (2): 239–259.

- Lau, R., and D. Redlawsk. 1997. “Voting Correctly.” American Political Science Review 91 (3): 585–598.

- Lau, R., and D. Redlawsk. 2006. How Voters Decide: Information Processing During Election Campaigns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Levi, M., and L. Stoker. 2000. “Political Trust and Trustworthiness.” Annual Review of Political Science 3: 475–507.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., R. Nadeau, and M. Foucault. 2013. “The Compleat Economic Voter: New Theory and British Evidence.” British Journal of Political Science 43 (2): 241–261.

- Mair, P. 2006. “Ruling the Void. The Hollowing of Western Democracy.” New Left Review 42: 25–51.

- Manin, B. 1997. Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Matthieß, T. 2020. “Retrospective Pledge Voting: A Comparative Study of the Electoral Consequences of Government Parties’ Pledge Fulfilment.” European Journal of Political Research 59 (4): 774–796.

- Powell, G. B. 2000. Elections as Instruments of Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Powell, G. B. 2004. “Political Representation in Comparative Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 7 (1): 273–296.

- Quinlan, S., and M. Okolikj. 2020. “Exploring the Neglected Dimension of the Economic Vote: A Global Analysis of the Positional Economics Thesis.” European Political Science Review 12 (2): 2019–2237.

- Rooduijn, M., S. Van Kessel, C. Froio, A. Pirro, S. De Lange, D. Halikiopoulou, P. Lewis, C. Mudde, and P. Taggart. 2019. “The PopuList.” http://www.popu-list.org.

- Rudolph, T. J. 2017. “Political Trust as a Heuristic.” In Handbook on Political Trust, edited by S. Zmerli, and T. van der Meer, 197–211. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Stiers, D., and R. Dassonneville. 2019. “Do Volatile Voters Vote Less Correctly? An Analysis of Correct Voting among Vote (Intention) Switchers in US Presidential Election Campaigns.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 29 (3): 283–298.

- Stiers, D., J. Larner, J. Kenny, S. Breitenstein, F. Vallée-Dubois, and M. Lewis-Beck. 2021. “Candidate Authenticity: ‘To Thine Own Self Be True’.” Political Behavior 43 (3): 1181–1204.

- Stubager, R., and R. Slothuus. 2013. “What Are the Sources of Political Parties’ Issue Ownership? Testing Four Explanations at the Individual Level.” Political Behavior 35 (3): 567–588.

- Van der Eijk, C., H. Schmitt, and T. Binder. 2005. “Left-Right Orientations and Party Choice.” In The European Voter. A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies, edited by J. Thomassen, 167–191. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Van der Meer, T., and E. Ouattara. 2019. “Putting ‘Political’ Back in Political Trust: An IRT Test of the Unidimensionality and Cross-National Equivalence of Political Trust Measures.” Quality & Quantity 53: 2983–3002.

- Van der Meer, T. W., and S. Zmerli. 2017. “The Deeply Rooted Concern with Political Trust.” In Handbook on Political TrustEdward Elgar Publishing.

- Wagner, M., D. Johann, and S. Kritzinger. 2012. “Voting at 16: Turnout and the Quality of Vote Choice.” Electoral Studies 31 (2): 372–383.

- Wu, C., and R. Wilkes. 2018. “Finding Critical Trusters: A Response Pattern Model of Political Trust.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 59 (2): 110–138.

- Zmerli, S., and M. Hooghe. 2011. Political Trust. Why Context Matters. Colchester: ECPR Press.