ABSTRACT

This study contributes to the literature on gendered candidate choice by investigating how voters’ ideological positions on both the socioeconomic left–right and the cultural GAL–TAN dimensions are associated with support for women candidates, and how these associations play out among women and men voters. The study is situated in the open-list proportional electoral system (OLPR) of Finland, where voters are obliged to cast a vote for a single candidate from a large selection of nominees and where women have a strong presence in the political sphere. We use unique data on voters’ self-reported candidate choice from two Finnish post-election studies in 2011 and 2019. The results show that a majority of both men and women voters tend to engage in same-gender voting, meaning that women voters are more inclined to cast a vote for women candidate than men voters are. We further show that the two ideological dimensions have different connections for men and women voters. While women voters’ propensity to support women candidates is connected to their position on the left–right dimension, but not to the GAL–TAN dimension, the opposite holds for men voters.

Introduction

The vote choice literature has identified a myriad of important factors that explain both party choice and candidate choice. In this study, we ask how ideological positions of voters are associated with their tendency to cast a vote for a women candidate. Studying support for women candidates is important because it has an impact on women’s representation in politics and since both genders have traditionally tended to vote for men candidates, partly due to the overrepresentation of men among the nominated candidates (McElroy and Marsh Citation2010; Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass Citation2014). The dominance of men in political life is also attributed to persistent gender stereotypes, according to which men are considered more competent in politics (Huddy and Terkildsen Citation1993; Eagly et al. Citation2004; Sanbonmatsu Citation2002) and less obliged to navigate both work and home responsibilities (Campbell and Childs Citation2017; McKay Citation2011). However, the presence of women in the political sphere has grown substantially in many countries, allowing voters to choose from more women candidates (Wängnerud Citation2000). In candidate-oriented electoral systems, such an increase in women politicians would not take place if voters were unwilling to cast a vote for women candidates.

Previous research into support for women candidates have mostly been situated in electoral systems with single-member districts where the choice of party and candidate are intertwined (Plutzer and Zipp Citation1996; Sanbonmatsu Citation2002). The relatively scarce literature based on elections in multimember districts, where voters are offered an intraparty choice between candidates of different genders, has provided mixed results. While some point towards voters not discriminating against women candidates (Paolino Citation1995; McElroy and Marsh Citation2010), others have found distinct differences in support for women candidates across electoral contexts (Giger et al. Citation2014) and groups of voters. These voting patterns vary with age, gender, political sophistication, group consciousness and gender ideology (e.g. Holli and Wass Citation2010; Marien, Schouteden, and Wauters Citation2017; Erzeel and Caluwaerts Citation2015; Dolan Citation1994). Previous research has explored the role of party preferences, and generally found that supporters of left-wing parties are more inclined to vote for women candidates compared to supporters of right-wing parties (Holli and Wass Citation2010; Erzeel and Caluwaerts Citation2015). The more specific role of political ideology (economic or cultural) in explaining support for women candidates has so far received relatively limited attention (but see Marien, Schouteden, and Wauters Citation2017; Rosenthal Citation1995).

We set out to contribute to the research on gendered candidate choice by theoretically and empirically exploring these issues. We focus on how both the economic left–right and the cultural GAL–TAN dimensions are associated with the voters’ propensity to vote for women candidates. We also explore the extent to which these different ideological dimensions show diverging associations for men and women voters. Our study is situated in Finland, an institutional context that is ideal for studying gendered candidate choice due to its open-list proportional representation system where it is mandatory for voters to cast a preference vote for a single candidate in their electoral district. Voters can choose between numerous men and women candidates from multiple party lists. Furthermore, the analyses of support for women candidates in this study are based on actual reported candidate choice, which is novel in the Finnish context and seldom applied in other contexts with a large supply of candidates.

Based on data from the Finnish National Election Study (FNES) from 2011 and 2019, our findings show that women are on average more likely to cast a vote for a woman candidate than men voters are. We further demonstrate that voters’ positioning on both the left–right and the GAL–TAN dimensions are associated with the likelihood of supporting a woman candidate, but that the effect of the two dimensions are played out differently for men and women voters. Leftist women voters are the most likely to cast a vote for a woman candidate, while the opposite holds for men voters with a distinct TAN position.

Gendered candidate choice

In candidate-oriented electoral systems, where the votes cast for individual candidates regulate which candidates become elected, voters and their behaviour have a direct impact on the level of descriptive representation. Under such conditions, we can expect those voters who prioritize descriptive representation to vote for a candidate who resembles them, for example, in terms of gender, and thus engage in same-gender voting (Holli and Wass Citation2010). The underlying reason for using gender as a basis for a voting decision can, however, differ across groups of voters. It might be motivated by group consciousness or an in-group bias, but it may also simply result from unconscious use of gender as a shortcut when confronted with an overload of political information and a multitude of candidates to choose from (for an overview, see Goodyear-Grant and Croskill Citation2011). Especially for less politically sophisticated voters, the candidate’s gender may work as a heuristic tool if they rely on gender-linked personality traits, ideological positions and competences between women and men candidates (McDermott Citation1998; Dolan Citation2014). It is, however, often assumed that an underlying motivation for same-gender voting is a wish for substantive representation, i.e. representation of interests that are specific for that group, and that voters make inferences about candidates’ stances on such interests based on their gender (e.g. Dolan Citation2014; Huddy and Terkildsen Citation1993; Rosenthal Citation1995; Sanbonmatsu Citation2002).

Of notable importance is that preference for descriptive representation is not equally strong for all voters, and the emphasis put on these issues tends to be associated with stances on gender roles. In the literature, the concept of “gender ideology” refers to individuals’ stand on the role of men and women in society (see Campbell and Erzeel Citation2018, 94). Regardless of their gender, some people are conservative in terms of gender ideology; they therefore support traditional gender roles and are less likely to vote for women candidates. In contrast, people who are progressive in terms of gender ideology do not see a problem with voting for women candidates (Erzeel and Caluwaerts Citation2015, 269). This gender ideology is not decoupled from political ideology, as we strive to examine in this paper.

From early childhood, individuals are exposed to gender stereotypes, i.e. ideas of what men and women are presumably like (Bussey and Bandura Citation1999), which can have a substantial effect on voters’ preference for a candidate’s gender (Dolan Citation2014; Sanbonmatsu Citation2002). While many societies across the world have generally become more egalitarian, traditional assumptions about gender, like politics being a man’s world, persist and create bias against women (Fox and Smith Citation1998). Sanbonmatsu (Citation2002), for instance, has found that people who believe men are better suited for politics and stronger on “hard” issues (crime and foreign affairs) are more likely to express a preference for men candidates. Most research point towards men voters being less inclined to cast a vote for a woman candidate than women voters (Holli and Wass Citation2010; Erzeel and Caluwaerts Citation2015; Marien, Schouteden, and Wauters Citation2017). Men hence have a strong tendency to vote for men candidates, an act which appears to be more related to subconscious tradition or habit, rather than an expression of gender consciousness or a genuine wish for descriptive or substantive representation (Rosenthal Citation1995; Holli and Wass Citation2010).

Given the historical underrepresentation of women in politics, it is to be expected that the motivations for a gendered candidate choice will be different between women and men. Research has demonstrated that voters who feel that women should be better represented in office are more inclined to vote for women candidates (Holli and Wass Citation2010). Thus, while women voting for women candidates is linked to feelings of group consciousness, with men voting for men candidates, it is less likely to be associated with feelings of solidarity and pursuit of gender equality in society. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that support for women candidates can be related to candidate supply (McElroy and Marsh Citation2010; Giger et al. Citation2014). Historically, globally and in Finland, which is the empirical case explored in this study, there has been a greater supply of men candidates to choose from. While this has changed in many countries, older generations of voters in particular have been socialized into voting during times when the supply of women candidates was low. For this reason, both older women and men may be more used to voting for men candidates (Holli and Wass Citation2010).

Ideology and gendered candidate choice

Political scientists have long noted a gender gap related to the ideology of voters; a gap that has been transformed over time. While women in early studies of public opinion were found to be more right-leaning, supporting parties on the right, this pattern gradually reversed during the latter part of the twentieth century, into what is described as “the modern gender gap”. As women’s roles and positions in society have changed, women are now more likely than men to be left-leaning and support parties on the left (Duverger Citation1955; Inglehart and Norris Citation2000). It is also possible that the gender gap (traditional or modern) can be accounted for by different views along a liberal-conservative ideological continuum, which captures attitudes such as traditional values, moral standards and tolerance (Norrander and Wilcox Citation2008).

As noted in the introduction, previous research has found support for women candidates to vary across parties. Overall, voters (both men and women) supporting leftist parties have been more active in voting for women candidates, while the opposite holds for voters of right-wing parties (Holli and Wass Citation2010; Erzeel and Caluwaerts Citation2015). The role of political ideology, such as economic left–right and cultural liberal–conservative political orientation, in explaining gendered candidate choice has received limited attention in the literature so far (see, however, Marien, Schouteden, and Wauters Citation2017; Rosenthal Citation1995). Hence, we believe that a closer exploration of the two ideological dimensions currently structuring political space in many advanced democracies, and their relation to the choice of candidate, can contribute to our understanding of the mechanisms behind the support for women candidates.

Firstly, the economic left–right dimension has played a central role in understanding political behaviour in general. The left–right dimension primarily captures the economic policy preferences of citizens but is often considered to encompass a broader spectrum of political issues, such as egalitarianism (Mair Citation2007). In the scholarship on gender and politics, an emphasis on women’s political representation has often been connected to the left (Celis and Childs Citation2012; Lovenduski and Norris Citation2003; Fernández and Valiente Citation2021). Parties to the left have traditionally put a stronger emphasis on feminist values and gender equality, while rightist parties have been seen as anti-feminist (Lovenduski and Norris Citation2003; Wängnerud Citation2000). Left-wing parties have also given more attention to descriptive representation of women and other groups that have traditionally been marginalized in the political arena. In line with attempts to increase women’s descriptive representation in politics, parties on the left have a longer history of recruiting and selecting female candidates, compared to parties on the right side of the ideological spectrum (Kittilson Citation2008). The legacy of the left in terms of promoting women’s representation makes it likely that there are connections between economic left–right and gender-based voting, with the core expectation being that individuals with left-wing ideologies, who support equal opportunities and outcomes in socioeconomic terms, should also be in favour of gender equality in the political arena (Erzeel and Caluwaerts Citation2015, 269). Likewise, left-leaning individuals are expected to support subordinated groups (Marien, Schouteden, and Wauters Citation2017), such as women, who are often underrepresented in parliaments around the world.

Secondly, following long-term structural development, gradual value change has taken place, and an alternative, or complementary, value dimension, which also can be seen as relevant when it comes to issues of gender equality and representation of women in politics, has grown in salience in many Western countries. This increasingly influential dimension has been described as consisting of cultural liberalism versus conservatism (Kriesi et al. Citation2006), post-materialist versus materialist values (Inglehart Citation1977), libertarian/universalistic versus traditionalist/communitarian values (Bornschier Citation2010) or green/alternative/libertarian versus traditional/authoritarian/nationalist (GAL–TAN) values (Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Citation2002). We prefer the broad conceptualization of the GAL–TAN dimension of political conflict and will be using it for the purposes of this study. This captures several different non-economic issues, such as law and order, moral issues, social freedom, environmental protection, and immigration (Kriesi et al. Citation2006; Polk and Rovny Citation2019).

While the connection between the left–right dimension and support for women candidates is expected to be primarily related to emphasis put on equal opportunity across different segments of society, and the importance of descriptive representation for underrepresented groups, the values incorporated in the GAL–TAN dimension are more directly related to views on women and men and their stereotypical roles in society. Cultural conservatism tends to go hand in hand with support for traditional gender roles, and the view of men as providers and leaders of the household, and as leaders in public life (Kriesi et al. Citation2006). It hence seems plausible that a TAN voter would find it a more natural choice to vote for a man candidate, compared to a woman candidate. The rising political importance of the GAL–TAN dimension in politics can also be connected to the spread of antifeminism, which has been understood through the theory of counter-movements (Blais and Dupuis-Deri Citation2012). In response to the heightened prominence of feminism, emphasis on traditional values and even distinct antifeminism has become more visible across Western countries (e.g. Elder, Green, and Lizotte Citation2021), meaning that same-gender voting among men can potentially also be motivated by ideology. Empirically these expectations render support in research demonstrating that populist radical right (PRR) parties, which are clearly positioned on the TAN side of the GAL–TAN dimension, attract men voters, and nominate men candidates, to a disproportionate extent (Coffé Citation2019).

Hypotheses

Drawing on the above review of the relevant literature, we offer three main hypotheses and two sub-hypotheses. We will start with a baseline hypothesis well supported in previous research on support for women candidates and on same-gender voting, even in the Finnish context (Holli and Wass Citation2010):

H1: Women voters are more likely to support women candidates than men voters.

H2a: Left-leaning voters are more likely to support women candidates than right-leaning voters.

H2b: The association between left–right ideology and support for women candidates is stronger for women voters than for men voters.

H3a: GAL-leaning voters are more likely to support women candidates than TAN-leaning voters.

H3b: The association between GAL–TAN ideology and the support for women candidates is weaker for women voters than for men voters.

The case of Finland

In comparison with the situation internationally, Finland is a case with a high presence of women in politics and a relatively high level of gender equality in society (Holli and Kantola Citation2007). Finland was one of the first countries in the world to introduce universal suffrage in 1906, and Finnish women have actively used their political rights. Since the 1980s, women have voted more actively in elections than men (Borg and Pikkala Citation2017, 11), and the share of women candidates in parliamentary and local elections increased steadily until the beginning of the 2000s, reaching a share of approximately 40 percent, which also reflects the share of elected women representatives (Borg and Pikkala Citation2017, 20; Pikkala Citation2020, 82). In the 2019 parliamentary elections, the share of elected female MPs reached an all-time high of 47 percent. Women have held many prominent political positions. In the period 2000–2012, Tarja Halonen was acting President; Finland has had a female Prime Minister since December 2019, and the majority of ministers in the government are women. Outside the political sphere, it is notable that women are more highly educated than men (Statistics Finland Citation2021a), and women participate in the labour market at similar rates as men. The employment rate in 2020 was 72.5 among men and 70.7 among women (Statistics Finland Citation2021b).

The Finnish open-list proportional representation (OLPR) electoral system provides voters with a lot of freedom when choosing a preferred candidate. (For an overview of the Finnish electoral system, see von Schoultz Citation2018.) Preferential voting is mandatory; voters must choose one candidate who represents a party. Voters are hence not able to cast a vote for a party list. Furthermore, most parties refrain from ranking their nominated candidates. Instead, they place their candidates in alphabetical order on lists, which leaves voters without an indication of parties’ preferred order of candidates. To draw support from as many social groups as possible, parties apply a so-called “balanced list strategy”, i.e. offering voters a wide selection of candidates with various social backgrounds to choose from (Arter Citation2013, 104; von Schoultz Citation2018, 610; Sipinen Citation2021, 215–219). This strategy also implies that parties aim to nominate an approximately equal share of women and men candidates on their lists, which has become commonplace during past decades, especially after the enactment of the Act on Equality Between Women and Men in 1987 (Huttunen Citation2012, 190; Kuitunen Citation2008, 115). Other important aspects in terms of balanced lists include candidates’ age, place of residence and their occupational background, since Finnish voters use this information when evaluating which groups the candidates would represent if elected (Arter Citation2013, 104; Kuitunen Citation2008, 123).

Given, firstly, the candidate-centred electoral system, secondly, Finland’s long tradition of political representation of women (along with a good supply of qualified female candidates in all elections) and thirdly, the female-friendly social context, Finland can be considered a most likely case for finding high levels of electoral support for women candidates.

Data and variables

To examine how respondents’ ideological positions in the economic left–right and cultural GAL–TAN dimensions are connected to voting for women, we use voter data from two Finnish National Election Studies: the 2011 and 2019 parliamentary elections.Footnote1 These are the only two Finnish surveys which include a question asking voters to specify the name of the candidate for whom voters cast their single mandatory preference vote (see below for more information). The two post-election surveys with face-to-face interviewing were carried out within two to three months of each election. The samples were drawn with the help of quota sampling, based on region of residence, mother tongue, gender and age (and type of municipality in 2019). Interviews were conducted with 1,298 individuals in 2011 and 1,598 in 2019. Data on candidates (gender and number of co-partisans on the list) are based on registry data from official sources. The combined dataset provides unique and comprehensive information on the characteristics of both voters and candidates.

While capturing same- or cross-gender voting is more straightforward in single member districts simply by asking the party of vote and electoral district, most studies of multimember districts use survey data where respondents are asked whether they voted for a man or woman candidate (e.g. Giger et al. Citation2014; Holli and Wass Citation2010). In this study, however, the dependent variable is based on actual vote choice (see also van Erkel Citation2019). Since we want to obtain more in-depth details of the characteristics of both voters and candidates, as well as link candidates to a specific party list in an electoral district, we find it useful to concentrate on those respondents who were willing to reveal the actual candidate they had voted for. We are aware that asking voters to reveal their vote choice could be linked to self-reporting bias, especially after an election, but we decided to opt for an objective measure of selecting a woman candidate. We are also aware that some voters might have been reluctant to reveal their actual vote choice or have forgotten whom they voted for; 49 percent of those who had voted remembered and were willing to reveal whom they had voted for in the 2011 self-administered drop-off questionnaire, while the share was 43 percent for the 2019 main survey with face-to-face interviews. The total number of respondents who revealed which candidate they voted for is 854 (333 in 2011 and 521 in 2019).Footnote2 After removing observations with missing values, we end up with a group of 812 respondents.

Our dependent variable, woman candidate vote, is binary and indicates whether the respondent voted for a woman candidate (coded 1) or for a man candidate (coded 0). The key independent variable in the model is the gender of the respondent. Hence, woman voter is a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the respondent is a woman and 0 if the respondent is a man. The logistic regression coefficient for woman voter will tell us to what extent women voters are more (or less) likely to vote for women candidates than for men candidates.

The other key independent variables measure voters’ ideological positions along two dimensions. We have included ideological positions instead of party choice because this measure gives us a more precise location of the voter in both issue dimensional spaces. First, the economic left–right ideological scale, which has long featured in national election studies, is based on how respondents place themselves on a scale between 0 (left) and 10 (right). The vast majority (96%) gave a response in terms of where they land on the left–right scale. Respondents who were not familiar with the scale, did not know where to place themselves or refused to answer are removed from the analysis. For comparability reasons, we rescale the variable to vary between 0 (most left) and 1 (most right). Second, the cultural GAL–TAN scale comprises seven items, six of which asked respondents to indicate a preference on an 11-point scale regarding what Finland should focus on. The response categories range from “a very bad proposition” to “a very good proposition”, with a middle category of “neither a good nor a bad proposition”. The six items asked about Christian values, status of traditional nuclear families, law and order in society, immigration, status of sexual minorities and eco-friendliness. The seventh item follows a Likert format and asked about the role of strong leaders (see ). Scores were recoded and standardized so that low values reflected GAL (green-alternative-libertarian) and high values TAN (traditional-authoritarian-nationalist). Internal consistency is acceptable, with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.64 for all respondents in the election surveys and 0.72 for the respondents in the analysed sample. Linear principal component analysis (PCA) including all respondents affirms that a single-factor solution adequately represented the observed data (eigenvalue = 2.41). All factor loadings are estimated to be 0.4 or above. A factor score is then derived and recoded to vary between 0 and 1.

Table 1. Measures of ideology.

To control for the possibility that leftist or GAL voters voted for female candidates just because these parties are more likely to nominate women candidates, we include the fraction of women candidates on the party list at the district level. Thus, we make sure that our results are not driven solely by there being more women on certain lists (see Marien, Schouteden, and Wauters Citation2017). This independent variable is measured as the proportion of women on the party’s list and takes values between 0 and 0.71. Additional control variables account for certain background characteristics of the voters – their age, level of education and interest in politics. Age is divided into five age groups: 18–29, 30–44, 45–59, 60–74 and 75–. The youngest age group (18–29) is the reference category in the regression analysis. Education is divided into three educational groups: primary, secondary and tertiary. Primary education is the reference category. To control for respondents’ political sophistication, we include interest in politics. The variable has three levels: “not interested”, “somewhat interested” and “very interested”. “Not interested” serves as a reference category. We also control for the difference in election study years, using the 2019 survey as the reference category.

Findings

shows the distribution of the dependent variable as well as the independent variables. In our sample, close to 47 percent of the respondents voted for a woman candidate. We use logistic regression to estimate the probability to cast a preference vote for a woman candidate.Footnote3 Standard errors clustered at the party level are used because responses may be correlated with each other. We enter the independent and control variables in different steps to detect possible changes in coefficients. The regression coefficients are presented in . For robustness, we estimated all models with party fixed effects and the coefficients are similar, except that the variable measuring fraction of women candidates becomes insignificant (see Table A1 in the online appendix).

Table 2. Weighted descriptive statistics (n = 812).

Table 3. Logistic regression models predicting voting for a woman candidate.

Our results are consistent with the first hypothesis stating that women voters are more likely to support women candidates than men voters. Model 1 in only includes the gender of the respondent (except for election year fixed effects). The independent variable woman voter is positively related to voting for a woman candidate. It has both a statistically and substantially significant effect. If we convert the coefficient on the logistic scale to the probability scale, 62 percent of the women respondents are predicted to vote for a woman candidate. For comparison, 33 percent of the men in the sample are predicted to vote for a woman candidate. The estimated log odds for woman changes only marginally in Models 2, 3 and 4 in which the remaining independent and control variables are introduced. Average predictive margins based on Model 4 indicate that 60 percent of the women and 35 of the men were predicted to vote for a woman, all else equal.

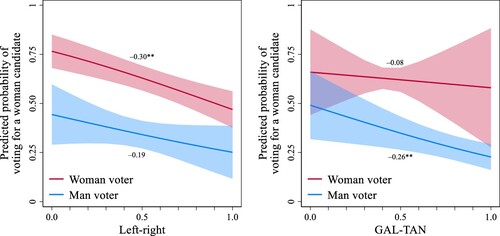

With regard to the first ideological measure, left–right position appears to best predict women’s propensity to vote for a woman candidate. According to Model 4, left–right position is substantively and significantly associated with voting for a woman candidate among all respondents, suggesting that left-leaning voters are more likely to support women candidates (H2a). In Model 5, the interaction term between ideological position and gender is introduced. The additional slope for women (i.e. the interaction term) is not statistically different from men’s slope. This means that the results do not provide robust support for the hypothesis that the association between left-right ideology and support for women candidates is stronger for women voters (H2b). However, the results come with a caveat. If the interaction is decomposed into simple slopes for each level of gender, the ideological dimension seems to matter for women voters but not for men voters. To demonstrate this, we calculate average predictive margins and visually display the predicted slopes based on the estimates for the main and interaction terms. The left panel in shows that the marginal effect for women voters is statistically significant. Voting for a woman candidate decreases from 77 to 47 percent when going from the most left to the most right on the left–right scale. Split sample regression (i.e. separate regression models for women and men) also shows that the simple slope for women voters is substantial and significant, but not for men voters (see Model 1 in Table A2 in the online appendix).

Figure 1. Predicted probability of voting for a woman candidate by ideology. Note: Average predictive margins (with 95% confidence intervals) based on the estimates in Model 5 (left-right) and Model 6 (GAL-TAN) in . The lines and coefficients represent the simple main effects when the gender of the respondents is set to woman and man.

In terms of GAL–TAN, the scale is initially substantially and significantly associated with voting for a woman candidate. However, the introduction of the control variable fraction of female candidates on the list in Model 4 leads to GAL–TAN position becoming an insignificant predictor. Our interpretation is that respondents with TAN values vote to a greater extent for men candidates who represent parties that have numerically more men candidates; or the other way around, respondents with GAL values are more likely to vote for women candidates who represent parties that are numerically dominated by women candidates. Therefore, we cannot find conclusive support for the hypothesis that GAL-leaning voters in general are more likely to support women candidates than TAN-leaning voters (H3a).

The results in Model 6 do not offer clear evidence that the association between GAL–TAN ideology and the support for women candidates is weaker for women voters than for men voters (H3b). However, a closer examination of the statistical estimates uncovers a significant association. If we obtain the simple slopes by gender, the negative simple slope for men is substantially and statistically significant. The same does not apply for women. illustrates the negative marginal effect for men: 49 percent of the most GAL-leaning men voted for a woman candidate compared to 23 percent of the most TAN-oriented men. Split sample regression confirms that the negative simple slope for men voters is substantially and statistically significant, but not for women voters (see Model 2 in Table A2 in the online appendix).

Conclusions

Women’s representation in politics and the dynamics behind it has attracted a great deal of interest from scholars of voting and political behaviour. In this study, we have contributed to this line of research by analysing how gender and the ideological positions of voters are related to voting for a woman candidate. We have studied these relations in Finland, an OLPR system with mandatory preference voting and a comparatively high level of gender equality both within and outside the political sphere. These factors, together with a rich selection of candidates of both genders make Finland a most-likely case for finding wide-spread support for woman candidates, and also an ideal case to identify the patterns related to women-centric vote choices.

Our analyses firstly identified the much-expected pattern that voting for women candidates is strongly related to the gender of voters with women being more inclined to support women candidates than men. The next step in our work was to look at the extent to which these patterns are influenced by the ideological dimensions currently dominating many western European political spaces – the economic left–right and cultural GAL–TAN. Given the scholarship on gender and politics, which has shown that left-wing parties and ideologies put a stronger emphasis on egalitarian values and support for underrepresented groups in politics, and on feminist values (Erzeel, Celis and Caluwaerts Citation2014; Lovenduski and Norris Citation2003; Wängnerud Citation2000), we expected voting for women to be particularly strong among left-leaning voters. We also expected the effect of left-right to be especially strong for women voters due to the emphasis on underrepresentation. Left-leaning voters were more likely to vote for women candidates, but this was more evident among women voters when deriving the simple regression slopes by gender.

For the cultural GAL–TAN dimension, in turn, we noted that these sets of values directly pertain to ideas of progressive versus conservative gender roles (Erzeel and Celis Citation2015). We hence expected voting for women to be more common among voters holding culturally progressive GAL-values. Our analysis did not show consistent evidence in support of this across both genders, but for men voters the effect of GAL-TAN turned out to be significant, with TAN-oriented men voters being less likely to vote for a woman.

Ideological stances reflect beliefs about how society should be organized and taps into values and belief systems such as gender equality or the role of women in society. It is hence not surprising that ideological positions have an impact on support for women in politics. The most intriguing observations in this study is that women’s voting behaviour in this sense is more strongly connected to left-right positioning, while men’s behaviour is more strongly driven by their position on the GAL-TAN dimension. Our interpretation is that values related to egalitarian opportunities and rewards for both genders are pushing women on the left to support women, while cultural values, tapping into views on gender roles, have a stronger impact on men’s behaviour. We hence conclude that ideology is relevant for understanding gendered candidate choice, and in extension women’s representation in politics, but that these relations are more complex than expected.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (110.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We would like to thank Veikko Isotalo for his work on developing accurate weights, as well as his work in retrieving the GAL – TAN dimensional information of candidates for both surveys.

2 There might be a skew in the sample if people who voted for a candidate that got elected were more likely to remember their choice. Also, in the Finnish case, there seems to be a tendency to reveal your choice if you are left-leaning. However, the differences in these samples do not influence our findings (see also von Schoultz, Järvi, and Mattila (Citation2020) for similar findings in 2019).

3 The equation of the full model is: logit(p) = b0 + b1(Woman) + b2(Left–Right) + b3(GAL–TAN) + b4(Share of woman candidates) + b5(Age 30–44) + b6(Age 45–59) + b7(Age 60–74) + b8(Age 75–) + b9(Secondary education) + b10(Tertiary education) + b11(Somewhat interested) + b12(Very interested) + b14(Year 2019) + e. The first interaction model also includes b15(Woman×Left–Right) and the second includes b15(Woman×GAL–TAN).

References

- Arter, David. 2013. “The “Hows”, not the “Whys” or the “Wherefores”: The Role of Intra-Party Competition in the 2011 Breakthrough of the True Finns.” Scandinavian Political Studies 36 (2): 99–120. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.12001

- Blais, Melissa, and Francis Dupuis-Deri. 2012. “Masculinism and the Antifeminist Countermovement.” Social Movement Studies 11 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1080/14742837.2012.640532

- Borg, Sami, and Sari Pikkala. 2017. Kuntavaalitrendit. https://kaks.fi/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/kuntavaalitrendit.pdf Helsinki: KAKS.

- Bornschier, Simon. 2010. “The new Cultural Divide and the two-Dimensional Political Space in Western Europe.” West European Politics 33: 419–444. doi:10.1080/01402381003654387

- Bussey, Kay, and Albert Bandura. 1999. “Social Cognitive Theory of Gender Development and Differentiation.” Psychological Review 106 (4): 676. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.676

- Campbell, Rosie, and Sarah Childs. 2017. “The (M)otherhood Trap: Reconsidering sex, Gender, and Legislative Recruitment.” In Mothers and Others: The Role of Parenthood in Politics, edited by M. Thomas, and A. Bittner, 25–45. Vancouver/Toronto: UBC Press.

- Campbell, Rosie, and Silvia Erzeel. 2018. “Exploring Gender Differences in Support for Rightist Parties: The Role of Party and Gender Ideology.” Politics and Gender 14 (1): 80–105. doi:10.1017/S1743923X17000599

- Celis, Karen, and Sarah Childs. 2012. “The Substantive Representation of Women: What to do with Conservative Claims?” Political Studies 60 (1): 213–225. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00904.x

- Coffé, Hilde. 2019. “Gender, Gendered Personality Traits and Radical Right Populist Voting.” Politics 3 (2): 170–185. doi:10.1177/0263395717745476

- Dolan, Kathleen. 2014. “Gender Stereotypes, Candidate Evaluations, and Voting for Women Candidates: What Really Matters?” Political Research Quarterly 67 (1): 96–107. doi:10.1177/1065912913487949

- Duverger, Maurice. 1955. The Political Role of Women. Paris: UNESCO.

- Eagly, Alice H., Amanda B. Diekman, Mary C. Johannesen-Schmidt, and Anne M. Koenig. 2004. “Gender Gaps in Sociopolitical Attitudes: A Social Psychological Analysis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87 (6): 796. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.796

- Elder, Laurel, Steven Green, and Mary-Kate Lizotte. 2021. “Feminist and Anti-Feminist Identification in the 21st Century United States.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 42 (3): 243–259. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2021.1929607

- Erzeel, Silvia, and Didier Caluwaerts. 2015. “Is It Gender, Ideology or Resources? Individual-Level Determinants of Preferential Voting for Male or Female Candidates.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 25 (3): 265–283. doi:10.1080/17457289.2015.1008495.

- Erzeel, Silvia, and Karen Celis. 2015. “Political Parties, Ideology and Women’s Substantive Representation.” Party Politics 22 (5): 576–586. doi:10.1177/1354068816655561

- Erzeel, Silvia, Karen Celis, and Didier Caluwaerts. 2014. “Are Conservatism and Feminism Mutually Exclusive in Belgium?.” In Gender, Conservatism and Political Representation, edited by K. Celis and S. Childs, 273–286. Essex: ECPR Press.

- Fernández, Juan J., and Celia Valiente. 2021. “Gender Quotas and Public Demand for Increasing Women’s Representation in Politics: An Analysis of 28 European Countries.” European Political Science Review, 1–20. doi:10.1017/S1755773921000126.

- Fox, Richard L., and Eric R.A.N. Smith. 1998. “The Role of Candidate sex in Voter Decision-Making.” Political Psychology 19 (2): 405–419. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00110

- Giger, Nathalie, Anne Maria Holli, Zoe Lefkofridi, and Hanna Wass. 2014. “The Gender gap in Same-Gender Voting: The Role of Context.” Electoral Studies 35: 303–314. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2014.02.009

- Goodyear-Grant, Elizabeth, and Julie Croskill. 2011. “Gender Affinity Effects in Vote Choice in Westminster Systems: Assessing “Flexible” Voters in Canada.” Politics & Gender 7 (2): 223–250. doi:10.1017/S1743923X11000079

- Holli, Anne Maria, and Johanna Kantola. 2007. “State Feminism Finnish Style: Strong Policies Clash with Implementation Problems.” In Changing State Feminism, edited by Joyce Outshoorn and Johanna Kantola, 82–101. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Holli, Anne Maria, and Hanna Wass. 2010. “Gender-based Voting in the Parliamentary Elections of 2007 in Finland.” European Journal of Political Research 49: 598–630. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01910.x.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, and Carole J. Wilson. 2002. “Does Left/Right Structure Party Positions on European Integration?” Comparative Political Studies 35 (8): 965–989. doi:10.1177/001041402236310.

- Huddy, Leonie, and Nayda Terkildsen. 1993. “Gender Stereotypes and the Perception of Male and Female Candidates.” American Journal of Political Science 37: 119–147. doi:10.2307/2111526

- Huttunen, Taina. 2012. Pitkä tie Pohjois-Karjalasta Arkadianmäelle: Naisten edustajaehdokkuudet janaiskansanedustajien kouliintumishistoria 1907–1999. [The Long Road from North Karelia to the Finnish Parliament: Recruitment of Women for Parliamentary Candidates 1907–1999]. Doctoral dissertation. Joensuu: University of Eastern Finland.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1977. “Values, Objective Needs, and Subjective Satisfaction among Western Publics.” Comparative Political Studies 9 (4): 429–458. doi:10.1177/001041407700900403

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2000. “The Developmental Theory of the Gender gap: Women’s and Men’s Voting Behavior in Global Perspective.” International Political Science Review 21 (4): 441–463. doi:10.1177/0192512100214007.

- Kittilson, Miki Caul. 2008. “Representing Women: The Adoption of Family Leave in Comparative Perspective.” The Journal of Politics 70: 323–334. doi:10.1017/S002238160808033X

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey. 2006. “Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared.” European Journal of Political Research 45 (6): 921–956. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x.

- Kuitunen, Soile. 2008. “Vaalit ja Ehdokkaiden Asettaminen.” In Suomen Puolueet ja Puoluejärjestelmä, edited by H. Paloheimo, and T. Raunio, 109–133. Helsinki: WSOY.

- Lovenduski, Joni, and Pippa Norris. 2003. “Westminster Women: The Politics of Presence.” Political Studies 51 (1): 84–102. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00414

- Mair, Peter. 2007. “Left–Right Orientations.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Behaviour, edited by R. J. Dalton, and H.-D. Klingemann, 206–222. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marien, Sofie, Anke Schouteden, and Bram Wauters. 2017. “Voting for Women in Belgium’s Flexible List System.” Politics & Gender 13 (2): 305–335. doi:10.1017/S1743923X16000404

- McDermott, Monika L. 1998. “Race and Gender Cues in Low-Information Elections.” Political Research Quarterly 51 (4): 895–918. doi:10.1177/106591299805100403

- McElroy, Gail, and Michael Marsh. 2010. “Candidate Gender and Voter Choice: Analysis from a Multimember Preferential Voting System.” Political Research Quarterly 63 (4): 822–833. doi:10.1177/1065912909336270

- McKay, Joanna. 2011. “‘Having it All?’ Women MPs and Motherhood in Germany and the UK.” Parliamentary Affairs 64 (4): 714–736. doi:10.1093/pa/gsr001

- Norrander, Barbara, and Clyde Wilcox. 2008. “The Gender gap in Ideology.” Political Behavior 30 (4): 503–523. doi:10.1007/s11109-008-9061-1

- Paolino, Phillip. 1995. “Group-salient Issues and Group Representation: Support for Women Can-Didates in the 1992 Senate Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 39 (2): 29–313. doi:10.2307/2111614

- Pikkala, Sari. 2020. Naiset eduskuntavaaleissa ja sukupuolen merkitys äänestämisessä. In: Eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2019, 80–102.

- Plutzer, Eric, and John F. Zipp. 1996. “Identity Politics, Partisanship, and Voting for Women Candidates.” Public Opinion Quarterly 60 (1): 30–57. doi:10.1086/297738

- Polk, Jan, and Jonathan Rovny. 2019. “New Wine in old Bottles: Explaining the Dimensional Structure of European Party Systems.” Party Politics 25 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1177/1354068817752518.

- Rosenthal, Cindy Simon. 1995. “The Role of Gender in Descriptive Representation.” Political Research Quarterly 48 (3): 599–611. doi:10.1177/106591299504800307

- Sanbonmatsu, Kira. 2002. “Gender Stereotypes and Vote Choice.” American Journal of Political Science 46 (1): 20–34. doi:10.2307/3088412

- Sipinen, Josefina. 2021. Recruitment of Immigrant-origin Candidates in Finnish Municipal Elections. Doctoral dissertation. Tampere: Tampere University.

- Statistics Finland. 2021a. Education. https://www.stat.fi/tup/tasaarvo/education/index_en.html.

- Statistics Finland. 2021b. Working life. https://www.stat.fi/tup/tasaarvo/tyoelama/index_en.html.

- van Erkel, Patrick F.A. 2019. “Sharing is Caring: The Role of Voter-Candidate Similarities in Intra-Party Electoral Competition.” European Political Science Review 11 (1): 75–89. doi:10.1017/S175577391800022X

- von Schoultz, Åsa. 2018. “Electoral Systems in Context: Finland.” In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems, edited by E. S. Herron, R. J. Pekkanen, and M. S. Shugart, 601–626. New York: Oxford University Press.

- von Schoultz, Åsa, Theodora Järvi, and Mikko Mattila. 2020. “Edustuksellisuuden henkilökohtainen ulottuvuus–puoluejohtajat ja ehdokkaat.” Politiikan Ilmastonmuutos Eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2019: 169–195.

- Wängnerud, Lena. 2000. “Testing the Politics of Presence: Women’s Representation in the Swedish Riksdag.” Scandinavian Political Studies 23 (1): 67–91. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.00031