ABSTRACT

Are elections becoming personality contests? A growing literature is concerned about the increasing personalization of politics and its democratic consequences. This paper argues that part of the phenomenon is due to voters using politicians’ personalities to infer their party and valence and that voters of populist parties are especially able in this inferential task. Using a varying conjoint experiment in Spain, the author certainly finds evidence that the importance of personality decreases when voters learn both about candidates’ party and valence and that this mediating effect is especially relevant for Vox and UP voters. These results dispel concerns about the irrationality of today's politics by showing that the independent effect of personality is minimal and suggesting that populist voters efficiently use the personality of politicians to infer classical vote determinants.

Introduction

“Feijoó, the leader who put ‘the pillars’ of his personality studying in León” (Fernández Citation2022), “The 5 keys to Feijóo’s personality” (Martos Citation2022), “Feijóo, the good manager of himself” (Oliver Citation2016). These are just some of the headlines on the latest new political leader (of the conservative PP party) in Spain, Alberto Núñez Feijóo. The interest in politicians’ personalities, however, is not only a Spanish thing. Over the last decades, the advent of more direct and visual media systems has allowed party leaders and front-runners to attract more attention from journalists and voters. (Mughan Citation2000; Poguntke and Webb Citation2005; Rahat and Kenig Citation2018). Based on this personalization of politics, some scholars have hypothesized that voters consider the personal dimension of candidates, and particularly their personality profile, as a key independent element for casting a vote (Adam and Maier Citation2010; Bittner Citation2015). This leads most research to assume that citizens not only care about candidates’ ideological standpoints and perceived political valence, but also about a rather nonpolitical element such as personality (Vitriol, Ksiazkiewicz, and Farhart Citation2018; Bittner Citation2018; Nai, Coma, and Maier Citation2019). The main assumption, therefore, is that citizens use their intuitions about human nature when evaluating candidates as if they were the people they deal with on a day-to-day business instead of evaluating them according to political criteria (Rahn et al. Citation1990).

Yet, another possibility is that when voters are exposed to political information, the importance of candidate personalities decreases because voters use personality as an indirect source of political information. Although this intuition has not yet been tested, research on leader effects suggests that voters look for rationality behind leader characteristics by focusing on those traits that are politically relevant and oriented towards performance (e.g. Bean Citation1993; Ohr and Oscarsson Citation2011). Stated differently, voters may be interested in a leader's personality traits because they can draw valuable inferences about the leader’s political values and qualities, which may inform their electoral decisions. This paper takes a step back and hypothesizes that the independent effect of candidates’ personalities is minimal and is conditional to the presence of both party and valence. Furthermore, it explores the heterogeneity of this effect and speculates that voters of populist parties, which habitually gravitate around the leadership of charismatic politicians (e.g. Mazzoleni Citation2008), are especially able to use personality as a mediator. Not only because of the populist appeal of strong leaders but because research suggests that populists use this low-complexity information to extract politically relevant information (Hauwaert and Kessel Citation2018).

It is key to understand the role of personality assessments as they are probably the most constant routine judgments of other people along with attractiveness. It takes 100 ms to make a first impression that does not usually change the perception of the other after a longer period of time (Willis and Todorov Citation2006), and research shows that even these first-sight impressions are often accurate enough to navigate the complexity of the social world (Funder Citation2012). This would mean voters use their very well-trained intuitions about people’s personalities to assess their favorability directly or indirectly for politicians.

In order to causally disentangle the role of candidates’ personality traits in voters’ decisions, I conducted a varying conjoint experiment embedded in an original representative survey in Spain. Following the methodology of Acharya and colleagues, respondents were asked to choose between pairs of fictional candidates under different informational scenarios (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Citation2018). All respondents were exposed to candidates’ randomly varying personality traits, but only some voters with candidates’ party affiliations, valence proxies, or both. This allowed us to causally separate the direct and indirect effects of personality traits on the voters’ decisions.

Results show that voters indeed significantly consider personality traits when making decisions between candidates. Although the importance voters place on personality drops significantly in the presence of both valence and party affiliation, personality continues to have a small independent effect on voters’ choice of candidate. This suggests that the candidates’ personality plays a particularly important role in the decision-making of voters in elections when voters do not have access to exhaustive information about candidates, are unwilling to gather, or are overwhelmed by the complexity of this information. A finding that resonates with the high personalization that is experienced in low information electoral contexts such as local politics where the personality of mayoral candidates are of particular relevance (Magre and Bertrana Citation2007).

Additionally, confirmatory evidence is found that voters of Unidas Podemos (populist left-wing party) and Vox (populist right-wing party) may use personality as a mediator to a greater degree. These results contribute to understanding the drivers of voters’ decision-making in candidate-centered or personalized elections, and more particularly, the role that personality plays in the ballot.

Theory

Personality traits and its role in the vote decision process

The ever-growing importance of political candidates and leaders in parliamentary elections (for a review, Rahat and Kenig Citation2018) has risen up the question of whether candidates’ personality traits might figure as a new component to the vote decision calculations (Lobo and Curtice Citation2014). This would not be the first association established between personality traits, defined as “descriptions of people in terms of relatively stable patterns of behavior, thoughts, and emotions” (Biesanz and West Citation2000), and political reasoning. The Big Five model, an integrative framework of personality composed of five superfactors such as Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Emotional StabilityFootnote1, has emerged as the most established measure of personality in analyses of political behavior and attitudes (for a review, Gerber et al. Citation2011). In this case, the personality of candidates could have both a direct or an indirect effect on people’s voting calculations from traditional determinants of the vote, party affinity, and political valence. Despite the division in the literature on how to conceptualize political valence, associated with issues or as leadership personality traits, researchers have found that there are two main candidates “super-categories” of valence – competence and trustworthiness/responsiveness – that comprise other surrounding traits such as intelligence or leadership (e.g. Barisione Citation2009; Bittner Citation2015). As the focus of this paper is to study the potential indirect use of personality, this study takes a compromised conception of valence, closely linked to political action. From this perspective, competence refers to the perceived capability of parties and candidates to execute their promises or policy proposals and to achieve the intended outcomes, and responsiveness denotes how reliable parties and candidates are when promising to fight for a certain policy or, more generally, how predictable their future political behavior is (for a deeper discussion on the conceptualization of valence, read Appendix A2).

The first possibility is that personality is a purely independent factor in voting decisions due to the growing saliency of leaders and candidates in the elections (e.g. Bittner Citation2015; Nai, Coma, and Maier Citation2019). This would lead Big Five researchers to find that voters are directly affected by the personality of politicians, either because they are attracted to those with a personality similar to their own (Caprara and Zimbardo Citation2004; Vecchione, Castro, and Caprara Citation2011; Weinschenk and Panagopoulos Citation2014), or because voters hold a preference for a homogenous personality ideal profile (Klingler, Hollibaugh, and Ramey Citation2019; Aichholzer and Willmann Citation2020), in the mode of the “Presidential Prototype” of Kinder’s seminal work (Kinder et al. Citation1980). Regardless of the exact way in which candidates’ personalities influence people’s choices, what seems clear is that personality should have a direct and independent effect on the vote choice, even if they simultaneously learn about candidates’ party and valence.

However, there are compelling reasons to believe that when citizens consider political information such as party or valence, the personality effect decreases. First, because the more relevant information is presented to citizens, it is reasonable to think that the relative importance of personality decreases. Second, and more importantly, in the presence of direct political information, the heuristic effect of personality loses its raison d'être. According to heuristics theory, citizens navigate the complexity of their political environment by relying on shortcuts that simplify their decision-making (Tversky and Kahneman Citation1974; Gigerenzer, Hertwig, and Pachur Citation2011). Caprara and Zimbardo argue that citizens transform impressions about politicians’ personalities into valence assessments (Caprara and Zimbardo Citation2004). They suggest that voters assemble personality traits assessments in two categories, which in turn serve as a cue for competence and trustworthiness (that includes responsiveness) assessments (Caprara and Zimbardo Citation2004; Caprara and Vecchione Citation2017). In a similar fashion, leaders’ ideology has been found to be systematically correlated to greater levels of certain personality traits both in Italy and Germany (Best Citation2011; Caprara et al. Citation2006). This is consistent with research on the homophily of the vote. From this viewpoint, voters are attracted to politicians with personalities like their own in a mediated way, i.e. because “similarity in traits carries similarity in worldview and values”, aspects closely connected to ideology and partisanship (Caprara and Vecchione Citation2017, 236). From this rationale it emerges that, although personality must have an independent and direct effect, it declines dramatically in the presence of both ideology and valence.

H1. Political candidates’ personality traits have an independent and direct effect on voters’ choices (Independent effect hypothesis).

H2. The effect of political candidates’ personality traits diminishes when voters are simultaneously exposed to candidates’ party and valence in addition to candidates’ personality (Conditional effect hypothesis).

Populist voters as personality-oriented voters

Scholars of leader effects (in which research on candidates’ personality is often subsumed) have tackled a similar question to the “conditionality” of personality effects (Barisione Citation2009; Mughan Citation2015). From this perspective, the effect of political candidates’ traits would be heterogeneous depending on the features of political parties or the voters’ individual characteristics.

From the perspective of individual characteristics, political psychologists have identified a special homophilic attraction in the realm of populist politics (Nai, Maier, and Vranić Citation2021; Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher Citation2016; Vasilopoulos and Jost Citation2020; Mayer, Berning, and Johann Citation2020). Thus, a relationship has been identified between support for populist/dark options and markers of low agreeableness (Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher Citation2016), authoritarianism, social dominance, system justification (Vasilopoulos and Jost Citation2020), and neuroticism (Mayer, Berning, and Johann Citation2020). Additionally, respondents with dark traits have been associated with the appeal for politicians with dark traits (Nai, Maier, and Vranić Citation2021). Dark traits that in turn are associated with the personality of the populist leaders themselves (Nai and Coma Citation2019).

Related to this, there is consensus on the fact that a majority of Western European right-wing populist parties have typically originated around the figure of a charismatic leader: Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Front National, Jörg Haider’s Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, Umberto Bossi’s Lega Nord, Pia Kjaersgaard’s Dansk Folkeparti, or Geert Wilders’ Partij voor de Vrijheid are good examples of this (Kefford and McDonnell Citation2018). Although with a different style from his extreme right-wing peers, Vox leader’s Santiago Abascal stands out for being the Spanish politician with the most followers on Instagram, a platform where he cultivates prototypical aspects of a strong and masculine leader such as his physical strength (Miro Citation2021; Sampietro and Sánchez-Castillo Citation2020). Charismatic leaders are not exclusive to the populist right; there is also a left-wing version. Pablo Iglesias’ Podemos, Alexis Tsipras and Yanis Varoufakis’ first Syriza or Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement are also European examples of strong masculine leaders that embody their party (Caiani, Padoan, and Marino Citation2021; Stavrakakis Citation2015), that resonate with long-lasting Latin American leftist populist charismatic leaders (De la Torre Citation2017). This preeminence of strong leadership in populist parties fits with recent evidence that puts the spotlight on the voters of these parties. In this regard, Michel and colleagues recently found that voters’ evaluations of party leaders are significantly associated with voting for populist radical right parties (Michel et al. Citation2020). This means there is evidence of leaders’ effects being more important for certain populist supporters. Populist supporters, which in turn, tend to follow parties that revolve around the aura of a charismatic leader.Footnote2

However, exposure to simple cues such as leaders’ persona does not necessarily come with less informed decisions. An example of this comes from political communication research. Although populist parties generally send less cognitively demanding messages as compared to non-populist voters (Bischof and Senninger Citation2018), these messages produce observable framing effects that can be easily translated into politically relevant information via heuristics (Cassell Citation2021). This resonates with the finding that, instead of apathetic citizens, populist supporters tend to be attentive and politically interested (Hauwaert and Kessel Citation2018). From this, it follows that populist voters believe character matters less in political leadership than individuals who scored low on populism (Seijts and Clercy Citation2020), not because the leaders do not have a greater presence in populist parties, or because homophily is not present, but because they use simple cues like leaders’ personality traits to infer political information.

H3. The mediating effect of political candidates’ personality is stronger among voters of populist parties (Populist hypothesis).

Methods

The survey

To explore the role of leaders’ personalities in elections, I conducted a survey with 1263 Spanish citizens representative of the national population in December 2018. The survey took place between 3 and 12 December in 2018 and was conducted by Survey Sampling International (now Dynata). In order to have a sample representative of the Spanish society we applied quotas on gender, education and age over the online pool of the company’s online pool. This type of samples, although not identical to probability samples, “much of the empirical research suggests that they provide valid results for experimental treatment effects” (Krupnikov, Nam, and Style Citation2021).Footnote3 The participants were first asked a set of basic sociodemographic questions (Appendix A3 for a short summary of survey characteristics and respondents’ attributes). Thereafter, the participants were exposed to a varying candidate-based conjoint experiment. Subsequently, participants had to answer a broadly validated self-assessed personality test (mini-IPIP; Donnellan et al. Citation2006) and a set of questions that capture their ideal candidate in terms of personality.

The varying conjoint experiment

I field a conjoint experiment that deviates from typical conjoint analyses in two ways. First, participants are not exposed to full-informed profiles of the fictional candidates. Instead, I randomly divided our sample into four further groups each of them showing a slightly different type of conjoint set with different information scenarios. shows what type of information is shown to the participants in each of the groups. All four types of conjoint show profiles contain information about candidates’ Big 5 (OCEAN) personality traits. Group 1 is only exposed to candidates’ personality traits. Groups 2 and 3 are additionally exposed to party and valence, respectively. Only Group 4 receives full information about fictional candidates’ parties, valence, and personality traits.

Table 1. The information scenarios of each of the conjoint experimental groups.

By doing this I extend the experimental technique developed by Sen and colleagues to measure whether the inclusion of a dimension reveals a mediation effect (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Citation2018; Sen Citation2017). In their case, they study whether US Supreme Court candidates’ ethnicity serves as a cue for voters to assess party leaning. To this end, they assign participants randomly in two groups. The first group is exposed only to candidates’ sociodemographic information. The second one is exposed to the same information but includes one additional factor: party affinity of the candidates. This design allowed them to causally disentangle the direct and indirect effect of the “black” racial cue, which in their case was found to be significant (Sen Citation2017).

This study’s conjoint experiment is based on the same logic. I scrutinize whether citizens’ preferences for candidates are shaped by candidates’ personality traits and to what degree the effect of personality traits disappears when further information about candidates’ party and valence is included in the decision-making, because, as Conover and Feldman (Citation1981) show, political evaluations are fraught with other consistent attitudinal and social control functions. If the effect of personality traits vanishes once information about party affiliation or valence is provided, this indicates that respondents use the former to infer the latter.

In addition, the sample is divided in two random groups, each of them being asked to choose between two different types of fictional politicians in five consecutive rounds.Footnote4 The first group had to choose between fictional mayor candidates, while the second group had to choose between fictional prime minister (PM) candidates. This test is supposed to show that my findings are consistent across different manipulated contexts, and it is not dependent on the level of personalization of the type of election.

The Spanish context

I choose to situate the survey in Spain for two main reasons. First, it is an ideal case to study the heuristic value of personality in the case of populist voters. This results from the fact that in front of three moderate parties, there are two populist parties, one on each side of the ideological spectrum (United Podemos and Vox) headed by two strong male leaders (Manganas Citation2021).Footnote5 Second, Spain has varying levels of personalized politics across different political arenas, which allows us to appropriately deal with the question of whether candidate-centered elections lead to the greater importance of candidates’ personalities. Spanish local elections have adopted a “strong-mayor form” by which the political power heavily concentrates on the mayor (Mouritzen and Svara Citation2002), making elections look like a contest between presidential candidates. Although some have argued that Spanish national elections are affected by a global personalization of politics (Camps Citation2009), the fact that the Spanish electorate indirectly chooses the prime minister (as compared to the direct choice of the mayor) makes these elections, by definition, less personalized (Martinez-Fuentes and Ortega Citation2010; Sagrera et al. Citation2017).Footnote6

Conjoint information

So far, I have explained that conjoint-sets vary depending on whether respondents have to choose pairs of fictional mayor candidates or fictional PM candidates, as well as the type of information scenario proposed to take the decisions. Now, the information used to describe each of the potential determinants of the vote will be explained.Footnote7

Party labels.

Valence. Here a proxy for each of the dimensions – competence and responsiveness – is chosen. As explained in the theory section, the former refers to the ability to go ahead with candidates’ political duties. Therefore, I chose the relative past performance of candidates in a valence issue such as employment. Relatedly, responsiveness is important in the sense that it allows respondents to develop some reliable expectations of what candidates’ political behavior will be. I, thus, used the accomplishment of political promises in previous political jobs. Since valence assessments can be appropriately done based on previous experience, in this experiment it is assumed that all candidates have previously occupied some political position in which they have had the opportunity to deliver their promises and contributed to lowering/increasing local unemployment rates in a certain manner.

Personality traits. The challenge of including short descriptions of different levels of the Big Five personality traits was met by using the Standard Feedback Form of NEO PI-R (Weiner and Greene Citation2007). Our decision was guided by the rationale to find the clearest and shortest but validated description of the OCEAN personality traits I found.

Gender. Although gender is not the focus of this study, I include this attribute to avoid biased self-treatments. If participants are not informed about candidates’ gender, they might assume it, which would add noise to the study. Moreover, by including candidate’s gender I am able to control female candidates’ advantage found by a meta-analysis of 67 conjoint experiments (Schwarz and Coppock Citation2022).

Research strategy

Each study yields ten observations per respondent, one for each hypothetical candidate with which they are presented across their five choice tasks, which gives ten observations per respondent if we count both those selected and those not selected in each of the 5 rounds (e.g. there are 1263 × 2 × 5 = 12,630 observations).

For the general model, our causal quantity of interest is the average marginal component effect (AMCE) of each level of a PM/Mayor candidate attribute – that is, the change in the probability that a candidate is preferred by the average respondent when the value of the attribute (component) of interest is changed from one level to another, averaging over all possible values of the candidates’ remaining attributes and all possible values of the attributes of the other candidate in the choice task (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). Because our design employs completely independent randomization, simple difference-in-means analysis yields unbiased AMCE estimates (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014) (Appendix A7 for proof of the randomization performance of the attributes). I estimate these differences by fitting a linear regression and clustering for respondents. All the calculations are done with R using the package cregg (Leeper Citation2018).

However, as recently demonstrated, comparing the AMCEs of population subgroups can lead to interpretive errors. This is because the effect of regression interactions is sensitive to the reference category used in the analysis (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020). That is why I assume the recommendation of using MMs (marginal means) to model the results of the mediating hypotheses.Footnote8

Results

Three sets of results are presented. In the following, I will first present the results for the independent hypothesis (H1), then the mediating hypothesis (H2), and finally the populist hypothesis (H3).

Figure A2 (Appendix A5) presents the AMCE results for each of the groups that were exposed to different levels of information scenarios. The group that only received information about the personality of the candidates can be observed in the first grid. Apart from extraversion that shows a relatively weaker effect, all the rest of personality traits seem to impact equally on respondents’ decisions.

More concretely, I find that relative to candidates with low traits, participants favor in general candidates who are high or moderate in all personality traits. There is only one exception which is neuroticism. In this case, respondents prefer emotionally stable candidates. It should be noted that respondents do not seem to have strong preferences between the moderate and high levels (low for neuroticism respectively) of each of the personality traits.

The second grid shows the results of group 2 of our sample in which respondents were provided not only with information about candidates’ personality traits but also about the candidate’s party. I find that respondents prefer moderate parties, both on left and on the right, over the extreme right party, VOX. But does including party labels suppress the effect of personality traits? While it is found weaker effects of certain personality traits, particularly in the case of neuroticism, all personality traits still have a significant impact on respondents’ choices. Hence, so far personality traits seem to show an independent effect on the choice of our respondents and are not only a mere shortcut to partisanship.

Group 3 (see third grid) was exposed to the same conjoint set as Group 2 but was informed with proxies about the valence of candidates instead of their party affiliation. Respondents preferred highly trustworthy candidates strongly over less trustworthy candidates. Compared to candidates who fulfilled 40% of their promises in their past political activity, candidates who scored 60% are more preferred although not as much as those who reached 80% of fulfillment. Highly competent candidates are also liked by respondents albeit to a lesser degree as compared to trustworthy ones. By contrast, results do not show differences between candidates who maintained unemployment rates and those who increased them, meaning that only highly competent leaders are favored. As with group 2, personality traits remain significant predictors for the candidate choice of participants despite the inclusion of valence proxies. In both groups, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness remain as the most significant personality traits.

The last grid represents the model in which respondents were exposed to a full information scenario with information about candidates’ personality traits, valence, and party affiliation. Again, trustworthiness appears to be the attribute that conditions the most the decision of our respondents. Similarly, the model shows a preference for highly competent candidates and respondents’ objections towards VOX candidates (although the full model also shows little general opposition against PP and Unidos Podemos). However, in contrast with previous models, the relative importance of personality traits seems to diminish when respondents are confronted with both valence and party cues.

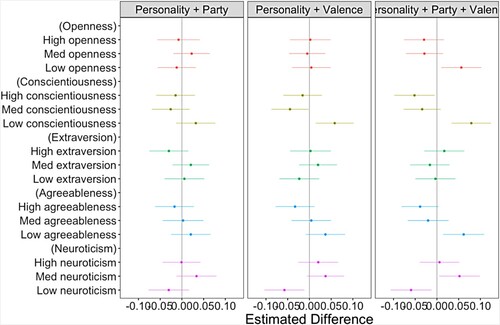

Focusing on the effect of personality traits only, shows the difference between the MMs estimates of the first model (only personality) with each of the remaining ones. The first two grids exhibit how learning about party labels or valence affects respondents’ considerations of candidates’ personality traits. While learning about candidates’ parties does not seem to elicit any significant difference in the model, showing valence cues significantly reduces the influence of neuroticism and conscientiousness on respondents’ decisions. Concretely, low neuroticism impacts less positively in voters’ decisions less when they simultaneously learn about candidates’ valence. The same occurs but in reverse with low conscientiousness: it is not so harmful to be poorly conscientious when respondents know more about candidates’ valence.

Contrarily, the effects of openness, extraversion, and agreeableness are not affected by adding information about party affiliation or valence. This means that personality traits still matter significantly when respondents are exposed to either valence or party labels.

The last grid of the figure demonstrates that respondents’ decision is indeed significantly affected by the inclusion of the combination of both party affiliations and valence information except for the case of extraversion (whose mediating effect remains as low as in previous models). This suggests that respondents’ preferences are indeed shaped by candidates’ personality traits although to a significantly lesser extent when respondents also learn about the combination of both valence and party affiliation.

The effects of personality traits although weakened are still significant when they are exposed to full information (except for openness). In turn, the fact that the effects of personality traits weaken when all the information is displayed suggests that they act as a shortcut when either valence or party attachment lacks or both. The effects show a statistically identical pattern regardless of whether respondents have to choose Mayor or PM candidates (Appendix A6). Thus, evidence suggests that although personality traits are a minimal independent determinant of the vote it effects dramatically decays when the classic determinants of the vote (party and valence) are included.

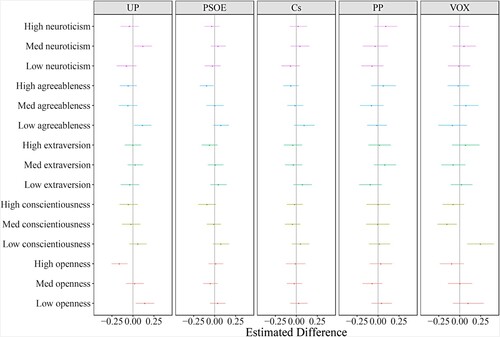

sheds light on the expectation that populist partisans will use personality as an inferential channel to personality and valence to a greater degree than partisans of non-populist parties. To do so it shows the same exact results as the last grid of (the comparison between choosing only based on personality vs the full model) but now the model is divided by respondents’ partisanship. For sample size reasons, only results for the main five Spanish are shown. Two of the five parties are populist (leftist UP and far-rightist VOX), and three of them are non-populists (center-leftist PSOE, center-rightist Cs, and rightist PP). If the focus is put on non-populist parties, one can see that there is no statistically significant difference that could indicate a mediating effect. Only in the case of PSOE, a minimal mediating effect for agreeableness can be observed, indicating that PSOE respondents deduce politically relevant information when they are exposed to highly agreeable voters.

Conversely, the first and last grids show the mediating effects of the populist parties’ supporters. Out of both, UP partisans seem to be the ones that show a clearer mediating behavior. In fact, in addition to perceiving a mediating effect in agreeableness as occurs with PSOE partisans, this effect is also perceived in the case of neuroticism and openness, where the effect is particularly strong. This suggests that UP voters infer politically relevant information from three of the big five personality traits. Regarding the right-wing populist party Vox, a strong mediating effect of conscientiousness can be noted. Particularly, it can be appreciated how when VOX supporters simultaneously know the party and the valence of the candidates the negative effect of being poorly conscientious decreases significantly.

Concluding remarks

In this paper, I show evidence that personality has an independent effect on candidate choice when the respondents are provided with information on only one of the two classic determinants of the vote.

In parallel to the independent effect of personality, results show that when voters lack a thorough understanding of the valence or ideology of political candidates, the importance of personality traits, mainly openness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, in their voting calculations increase significantly. This has important implications. While personality assessments are among the most common and quick judgments made by citizens on a daily basis since childhood (Charlesworth et al. Citation2019; Willis and Todorov Citation2006), candidates’ political qualities are not always easy for ordinary voters to determine. This is especially true in times in which more than half of Western Europeans feel that politics are too complicated (Valgarðsson Citation2020, 111). Given that research shows that people use personality to a large extent and tend to be accurate (Funder Citation2012), the fact that they use it so much in the absence of other information is important. This could mean that personality will matter more in person-centered contexts or those in which there is simply not enough information about candidates’ valence or party.

I expected that the mediating effect of personality is something especially present in supporters of populist parties. All in all, these are voters that typically follow parties that are leader-centered. Findings support this idea. When the sample is split into parties, apart from PSOE, only Vox and (especially) Unidas Podemos show a significant mediating effect of personality cues. PSOE, although not as populist as its mainstream counterpart is a party that under Pedro Sánchez has moved towards an “overwhelmingly personalistic” style in both performance and decisions in recent times (Barberà and Rodríguez-Teruel Citation2020). The fact that not only in populist parties this effect is present, but also in the PSOE, suggests that it is the centrality of leadership that determines the use of personality as a cue to learn about the underlying politics.

These results should be considered relevant from three perspectives. First, from a rational perspective, this paper responds to normative concerns about the irrationality of today’s elections. Concerns include the risk that increased personalization may introduce irrational features into democratic politics prioritizing personality above the impersonal rule of law and institutions, and that parasocial relations between leaders and the people will weaken accountability structures (Pedersen and Rahat Citation2021). The independent and direct effects of personality seem to be in any case small when voters face an information-rich setting. That is why the concerns should be driven more toward facilitating voters’ deeper knowledge of candidates’ party and valence than toward reducing candidates’ salience.

Second, this paper asked whether voters of populist parties were more able to use personality as an inferential tool. Indeed, this paper finds evidence to support this prediction, with special emphasis on the case of the left-wing populist party Unidas Podemos. This reinforces the idea that voters of populist parties, despite being exposed to simpler cues, either personality or messages, transform these cues into relevant information for their vote.

Finally, this paper contributes to the existing literature on the causal independence of personality effects. A dominant interpretation of these results is that voters could be using information about candidates’ personalities to efficiently infer relevant information about their party and political valence. This would have crucial implications for the literature on the personality effects of politicians. Given that a major part of personality is used to infer politics, one possible avenue for new research is to focus on exactly how each personality trait is used and whether it is used equally with candidates from different parties. Additionally, varying the electoral level of competition (mayoral or government) fictitiously in the way this paper does has its limitations. That is why future research should test how these results vary with observational evidence.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (352.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A detailed explanation of the Big Five personality traits is in the appendix A1.

2 Although populism is understood in multiple ways among the public (M. C. Casiraghi Citation2021; M. C. M. Casiraghi and Bordignon Citation2023) and the literature (Hunger and Paxton Citation2022), in this paper we consider as a defining aspect of populism its reliance on flamboyant and strong “leaders able to mobilize the masses with the aim of enacting radical reforms” and protecting them from an Manichean elite silencing the voice of the real people (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2014, Citation2017; Weyland Citation2001; Eatwell Citation2002).

3 Although the survey was sent to 1489 respondents, only 1263 respondents passed the response quality control comprised of two criteria: passing an attention check question that verified that they were reading the survey attentively and finishing the survey within 5 min for a survey that lasted on average more than 10 min.

4 Although recent research shows that the response quality remains high up to dozens consecutive conjoint tasks (Bansak et al. Citation2018), I stick to five rounds given the fact that my conjoint-sets involve more information than the average conjoint.

5 According to the Global Party Survey Vox (9.2) and Unidas Podemos: (7.3) are the parties that score the highest in the populist scale in Spain, the scores of the rest of parties moderately low (Cs 3.7; PP: 3; PSOE: 2.5). (Norris Citation2020). The PopuList, an expert-coded index of populist parties, corroborates that Vox and Unidas Podemos are the two only national populist parties in Spain (Rooduijn et al. Citation2019).

6 I acknowledge that Spain is a representative democracy and that Spaniards do not directly choose their PM. Yet, it is reasonable to include such candidates given the somewhat “presidentialized” nature of the elections, and the fact that voters know significantly better candidates for PM than the candidates in their own constituency (Holmberg Citation2009).

7 A detailed table with the specific operationalization of the variables and an example of the conjoint tasks as it was presented to the respondents can be found in in Appendix A4.

8 Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley (Citation2020) show that while AMCEs “lead to inferences about subgroup differences in preferences that have an arbitrary sign, size, and significance”, MMs “clearly convey the similarity of these two subgroups without any sensitivity to reference category”.

References

- Acharya, Avidit, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen. 2018. “Analyzing Causal Mechanisms in Survey Experiments.” Political Analysis 26 (4): 357–378. doi:10.1017/pan.2018.19.

- Adam, Silke, and Michaela Maier. 2010. “Personalization of Politics A Critical Review and Agenda for Research.” Annals of the International Communication Association 34 (1): 213–257. doi:10.1080/23808985.2010.11679101.

- Aichholzer, Julian, and Johanna Willmann. 2020. “Desired Personality Traits in Politicians: Similar to Me but More of a Leader.” Journal of Research in Personality 88: 103990. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103990.

- Bakker, Bert N., Matthijs Rooduijn, and Gijs Schumacher. 2016. “The Psychological Roots of Populist Voting: Evidence from the United States, the Netherlands and Germany.” European Journal of Political Research 55 (2): 302–320. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12121.

- Bansak, Kirk, Jens Hainmueller, Daniel J. Hopkins, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2018. “The Number of Choice Tasks and Survey Satisficing in Conjoint Experiments.” Political Analysis 26 (1): 112–119. doi:10.1017/pan.2017.40.

- Barberà, Oscar, and Juan Rodríguez-Teruel. 2020. “The PSOE’s Deliberation and Democratic Innovations in Turbulent Times for the Social Democracy.” European Political Science 19 (2): 212–221. doi:10.1057/s41304-019-00236-y.

- Barisione, Mauro. 2009. “So, What Difference Do Leaders Make? Candidates’ Images and the ‘Conditionality’ of Leader Effects on Voting.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 19 (4): 473–500. doi:10.1080/17457280903074219.

- Bean, C. 1993. “The Electoral Influence of Party Leader Images in Australia and New Zealand.” Comparative Political Studies 26 (1): 111–132. doi:10.1177/0010414093026001005.

- Best, Heinrich. 2011. “Does Personality Matter in Politics? Personality Factors as Determinants of Parliamentary Recruitment and Policy Preferences.” Comparative Sociology 10 (6): 928–948. doi:10.1163/156913311X607638.

- Biesanz, Jeremy C., and Stephen G. West. 2000. “Personality Coherence: Moderating Self–Other Profile Agreement and Profile Consensus.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79 (3): 425–437. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.425.

- Bischof, Daniel, and Roman Senninger. 2018. “Simple Politics for the People? Complexity in Campaign Messages and Political Knowledge.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (2): 473–495. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12235.

- Bittner, Amanda. 2015. Leader Evaluations and Partisan Stereotypes: A Comparative Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bittner, Amanda. 2018. “Leaders Always Mattered: The Persistence of Personality in Canadian Elections.” Electoral Studies 54: 297–302. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.013.

- Caiani, Manuela, Enrico Padoan, and Bruno Marino. 2021. “Candidate Selection, Personalization and Different Logics of Centralization in New Southern European Populism: The Cases of Podemos and the M5S.” Government and Opposition 57 (3): 404–427. doi:10.1017/gov.2021.9.

- Camps, Guillem Rico. 2009. Líderes políticos, opinión pública y comportamiento electoral en España. Madrid: CIS.

- Caprara, Gian Vittorio, Shalom Schwartz, Cristina Capanna, Michele Vecchione, and Claudio Barbaranelli. 2006. “Personality and Politics: Values, Traits, and Political Choice.” Political Psychology 27 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00447.x.

- Caprara, Gian Vittorio, and Michele Vecchione. 2017. Personalizing Politics and Realizing Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Caprara, Gian Vittorio, and Philip G. Zimbardo. 2004. “Personalizing Politics: A Congruency Model of Political Preference.” American Psychologist 59 (7): 581–594. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.581.

- Casiraghi, Matteo CM. 2021. “‘You’Re a Populist! No, You Are a Populist!’: The Rhetorical Analysis of a Popular Insult in the United Kingdom, 1970–2018.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 23 (4): 555–575. doi:10.1177/1369148120978646.

- Casiraghi, Matteo C. M., and Margherita Bordignon. 2023. “The Rhetorical Contestation of Populism in Four European Parliaments (2010–2020).” West European Politics 46 (1): 173–195. doi:10.1080/01402382.2021.2013655.

- Cassell, Kaitlen J. 2021. “When “Following” the Leader Inspires Action: Individuals’ Receptivity to Discursive Frame Elements on Social Media.” Political Communication 38 (5): 581–603. doi:10.1080/10584609.2020.1829761.

- Charlesworth, Tessa E. S., Sa-kiera T. J. Hudson, Emily J. Cogsdill, Elizabeth S. Spelke, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2019. “Children Use Targets’ Facial Appearance to Guide and Predict Social Behavior.” Developmental Psychology 55 (7): 1400–1413. doi:10.1037/dev0000734.

- Conover, P. J., and S. Feldman. 1981. “The Origins and Meaning of Liberal/Conservative Self-Identifications.” American journal of political science 617–645.

- De la Torre, Carlos. 2017. “Populism in Latin America.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul A. Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy, 195–213. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Donnellan, M. Brent, Frederick L. Oswald, Brendan M. Baird, and Richard E. Lucas. 2006. “The Mini-IPIP Scales: Tiny-yet-Effective Measures of the Big Five Factors of Personality.” Psychological Assessment 18 (2): 192–203. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192.

- Eatwell, Roger. 2002. “The Rebirth of Right-Wing Charisma? The Cases of Jean-Marie Le Pen and Vladimir Zhirinovsky.” Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 3 (3): 1–23. doi:10.1080/714005489.

- Fernández, Fulgencio. 2022. “Feijoó, el líder que puso los pilares de su personalidad en León.” La Nueva Crónica: Diario leonés de información general, March 27, 2022, sec. LNC Culturas. https://www.lanuevacronica.com/feijoo-el-lider-que-puso-los-pilares-de-su-personalidad-estudiando-en-leon.

- Funder, David C. 2012. “Accurate Personality Judgment.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 21 (3): 177–182. doi:10.1177/0963721412445309.

- Gerber, Alan S., Gregory A. Huber, David Doherty, and Conor M. Dowling. 2011. “The Big Five Personality Traits in the Political Arena.” Annual Review of Political Science 14 (1): 265–287. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051010-111659.

- Gigerenzer, Gerd, Ralph Hertwig, and Thorsten Pachur, eds. 2011. Heuristics: The Foundations of Adaptive Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Daniel J. Hopkins, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2014. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1093/pan/mpt024.

- Hauwaert, Steven M. Van, and Stijn Van Kessel. 2018. “Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (1): 68–92. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12216.

- Holmberg, Sören. 2009. “Candidate Recognition in Different Electoral Systems.” In The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, edited by Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 158–170. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hunger, Sophia, and Fred Paxton. 2022. “What’s in a Buzzword? A Systematic Review of the State of Populism Research in Political Science.” Political Science Research and Methods 10 (3): 617–633. doi:10.1017/psrm.2021.44.

- Kefford, Glenn, and Duncan McDonnell. 2018. “Inside the Personal Party: Leader-Owners, Light Organizations and Limited Lifespans.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 20 (2): 379–394. doi:10.1177/1369148117750819.

- Kinder, Donald R., Mark D. Peters, Robert P. Abelson, and Susan T. Fiske. 1980. “Presidential Prototypes.” Political Behavior 2 (4): 315–337. doi:10.1007/BF00990172.

- Klingler, Jonathan D., Gary E. Hollibaugh, and Adam J. Ramey. 2019. “What I Like about You: Legislator Personality and Legislator Approval.” Political Behavior 41 (2): 499–525. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9460-x

- Krupnikov, Yanna, H. Hannah Nam, and Hillary Style. 2021. “Convenience Samples in Political Science Experiments.” In Advances in Experimental Political Science, edited by James N. Druckman and Donald P. Green, 165–182. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leeper, Thomas J. 2018. “Cregg: Simple Conjoint Analyses and Visualization.” R Package Version 0.2 1.

- Leeper, Thomas J., Sara Hobolt, and James Tilley. 2020. “Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments.” Political Analysis, 28: 207–221. doi:10.1017/pan.2019.30.

- Lobo, Marina Costa, and John Curtice. 2014. Personality Politics?: The Role of Leader Evaluations in Democratic Elections. Oxford: OUP.

- Magre, Jaume, and Xavier Bertrana. 2007. “Exploring the Limits of Institutional Change: The Direct Election of Mayors in Western Europe.” Local Government Studies 33 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1080/03003930701198557.

- Manganas, Nicholas. 2021. “Iberian Swagger versus Feminist Masculinity.” In The Culture and Politics of Populist Masculinities, edited by Outi Hakola, Janne Salminen, Juho Turpeinen, and Oscar Winberg, 3–27. London: Lexington Books.

- Martinez-Fuentes, G., and Carmen Ortega. 2010. “The Political Leadership Factor in the Spanish Local Elections.” Lex localis - Journal of Local Self-Government 8: 147–160. doi:10.4335/8.2.147-160(2010).

- Martos, Alicia. 2022. “Las 5 claves de la personalidad de Feijóo #ComunicaciónNoVerbal.” 20 Minutos, May 3, 2022. https://blogs.20minutos.es/comunicacion-no-verbal-lo-que-no-nos-cuentan/2022/05/03/las-5-claves-de-la-personalidad-de-feijoo-comunicacionnoverbal/.

- Mayer, Sabrina J., Carl C. Berning, and David Johann. 2020. “The Two Dimensions of Narcissistic Personality and Support for the Radical Right: The Role of Right–Wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation and Anti–Immigrant Sentiment.” European Journal of Personality 34 (1): 60–76. doi:10.1002/per.2228.

- Mazzoleni, G.. 2008. “Populism and the Media.” In Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy, 49–64. doi:10.1057/9780230592100_4.

- Michel, Elie, Diego Garzia, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, and Andrea De Angelis. 2020. “Leader Effects and Voting for the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe.” Swiss Political Science Review 26 (3): 273–295. doi:10.1111/spsr.12404.

- Miro, Clara Juarez. 2021. “Who Are the People? Using Fandom Research to Study Populist Supporters.” Annals of the International Communication Association 45 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/23808985.2021.1910062.

- Mouritzen, Poul Erik, and James H. Svara. 2002. Leadership at the Apex: Politicians and Administrators in Western Local Governments. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal R. Kaltwasser. 2014. “Populism and Political Leadership.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Leadership, edited by R. A. W. Rhodes and Paul 't Hart, 376–388. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2017. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mughan, Anthony. 2000. Media and the Presidentialization of Parliamentary Elections. New York: Springer.

- Mughan, Anthony. 2015. “Parties, Conditionality and Leader Effects in Parliamentary Elections.” Party Politics 21 (1): 28–39. doi:10.1177/1354068812462930.

- Nai, Alessandro, and Ferran Martinez i Coma. 2019. “The Personality of Populists: Provocateurs, Charismatic Leaders, or Drunken Dinner Guests?” West European Politics 42 (7): 1337–1367. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1599570.

- Nai, Alessandro, Ferran Martínez i Coma, and Jürgen Maier. 2019. “Donald Trump, Populism, and the Age of Extremes: Comparing the Personality Traits and Campaigning Styles of Trump and Other Leaders Worldwide.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 49 (3): 609–643. doi:10.1111/psq.12511.

- Nai, Alessandro, Jürgen Maier, and Jug Vranić. 2021. “Personality Goes a Long Way (for Some). An Experimental Investigation into Candidate Personality Traits, Voters’ Profile, and Perceived Likeability.” Frontiers in Political Science 3: 4. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.636745.

- Norris, Pippa. 2020. “Measuring Populism Worldwide.” Party Politics 26 (6): 697–717. doi:10.1177/1354068820927686.

- Ohr, D., and H. Oscarsson. 2011. “Leader Traits, Leader Image and Vote Choice.” Political Leaders and Democratic Elections 187–219. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=b66ed2c7b6c190427d8ca78d44c80626849646fb.

- Oliver, Juan. 2016. “Feijóo, El Buen Gestor de Sí Mismo.” Público, May 29, 2016, sec. Política. https://www.publico.es/politica/feijoo-buen-gestor-mismo.html.

- Pedersen, Helene Helboe, and Gideon Rahat. 2021. “Political Personalization and Personalized Politics within and Beyond the Behavioural Arena.” Party Politics 27 (2): 211–219. doi:10.1177/1354068819855712.

- Poguntke, Thomas, and Paul Webb. 2005. “The Presidentialization of Politics in Democratic Societies: A Framework for Analysis.” In The Presidentialization of Politics: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies, edited by Thomas Poguntke and Paul Webb, 1–25. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rahat, Gideon, and Ofer Kenig. 2018. From Party Politics to Personalized Politics?: Party Change and Political Personalization in Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rahn, Wendy M., John H. Aldrich, Eugene Borgida, and John L. Sullivan. 1990. “A Social Cognitive Model of Candidate Appraisal.” In Controversies in Voting Behavior, edited by Richard G. Niemi and Herbert F. Weisberg, 187–206. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Stijn Van Kessel, Caterina Froio, Andrea Pirro, Sarah De Lange, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Paul Lewis, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart. 2019. “The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe.”

- Sagrera, Pedro Riera, Raúl Gómez Martínez, Juan Antonio Mayoral Díaz-Asensio, Pablo Barberá Aragüena, and José Ramón Montero Gibert. 2017. “Elecciones municipales en España. La personalización del voto.” Revista Internacional de Sociología 75 (2): 062. doi:10.3989/ris.2017.75.2.15.140.

- Sampietro, Agnese, and Sebastián Sánchez-Castillo. 2020. “Building a Political Image on Instagram: A Study of the Personal Profile of Santiago Abascal (Vox) in 2018.” Communication & Society 33 (1): 169–184. doi:10.15581/003.33.37241.

- Schwarz, Susanne, and Alexander Coppock. 2022. “What Have We Learned about Gender from Candidate Choice Experiments? A Meta-Analysis of Sixty-Seven Factorial Survey Experiments.” The Journal of Politics 84: 655–668. doi:10.1086/716290.

- Seijts, Gerard, and Cristine de Clercy. 2020. “How Do Populist Voters Rate Their Political Leaders? Comparing Citizen Assessments in Three Jurisdictions.” Politics and Governance 8 (1): 133–145. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i1.2540.

- Sen, Maya. 2017. “How Political Signals Affect Public Support for Judicial Nominations: Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment.” Political Research Quarterly 70 (2): 374–393. doi:10.1177/1065912917695229.

- Stavrakakis, Yannis. 2015. “Populism in Power: Syriza’s Challenge to Europe.” Juncture 21 (4): 273–280. doi:10.1111/j.2050-5876.2015.00817.x

- Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1974. “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Science 185 (4157): 1124–1131. doi:10.1126/science.185.4157.1124.

- Valgarðsson, Viktor Orri. 2020. “Turnout Decline in Western Europe: Apathy or Alienation?” PhD thesis, University of Southampton. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/451366/.

- Vasilopoulos, Pavlos, and John T. Jost. 2020. “Psychological Similarities and Dissimilarities between Left-Wing and Right-Wing Populists: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey in France.” Journal of Research in Personality 88: 104004. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104004.

- Vecchione, Michele, José Luis González Castro, and Gian Vittorio Caprara. 2011. “Voters and Leaders in the Mirror of Politics: Similarity in Personality and Voting Choice in Italy and Spain.” International Journal of Psychology 46 (4): 259–270. doi:10.1080/00207594.2010.551124.

- Vitriol, Joseph A., Aleksander Ksiazkiewicz, and Christina E. Farhart. 2018. “Implicit Candidate Traits in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election: Replicating a Dual-Process Model of Candidate Evaluations.” Electoral Studies 54: 261–268. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.009.

- Weiner, Irving B., and Roger L. Greene. 2007. Handbook of Personality Assessment. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Weinschenk, Aaron C., and Costas Panagopoulos. 2014. “Personality, Negativity, and Political Participation.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 2 (1): 164–182. doi:10.5964/jspp.v2i1.280.

- Weyland, Kurt. 2001. “Clarifying a Contested Concept: Populism in the Study of Latin American Politics.” Comparative Politics 34 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2307/422412.

- Willis, Janine, and Alexander Todorov. 2006. “First Impressions: Making Up Your Mind After a 100-Ms Exposure to a Face.” Psychological Science 17 (7): 592–598. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01750.x.