Abstract

Women who are victims of intimate partner violence often suffer of depression and anxiety disorders. We evaluated the performance of the SRQ-20 scale (screening test for common mental health disorders), in women victims of intimate partner violence by male partners. A total of 100 women were surveyed from the out-patient mental health services in four health institutions in Valle del Cauca (Colombia). SRQ-20 scales (Binary version versus Likert version) were compared with mental health diagnoses based on the HSCL-25 scale, as the gold standard. Optimal SRQ-20 cut-off score is > = 6 points; lower than the initially suggested, sensitivity of 96.6% and specificity of 90.9%. The new SRQ-20-Likert scale, establishing a cut-off of > = 8 points, shows better sensitivity (98.9%) and equal specificity than the original scale. Studied SRQ-20 scales are promising instruments for screening mental health disorders among women victims of intimate partner violence in primary health care settings.

Introduction

In Colombia, the Observatory of Violence of the National Institute of Forensic Medicine (in Spanish, INMLCF) has reported that during 2020 to 2021, the percentage variation in cases of intimate partner violence against women has been increased 10%. During these years, 26,701 cases were against women. Likewise, the feminicides, i.e. homicides against women due to gender issues, increased by 3.7%, going from 81 cases reported in 2020 to 84 cases in 2021 (INMLCF, 2022). This violence causes serious consequences in the mental health of women as depression, anxiety and posttraumatic distress disorder symptoms, mainly in those who have vulnerability factors (forced displacement forced, childhood abuse, poverty, among others), which increase the risks of being victims and suffer the most severe forms of intimate partner violence (Lennon et al., Citation2021).

It is recognized that women survivors of intimate partner violence are at greater risk of presenting mental health problems throughout their lives as a consequence of this violence with a more significant occurrence of depressive symptoms, anxiety and suicidal ideation (Loxton et al., Citation2017); however, less is said about the bidirectional relationship between the underlying mental condition and intimate partner violence, which could act in a protective way, through resilient elements (Machisa et al., Citation2018) or, on the contrary, could act as a determinant that precedes and potentiates the risk of violence, as happens with men and women with depression, poor mental functioning or problematic alcohol use (Loxton et al., Citation2017; Machisa et al., Citation2018; Devries et al., Citation2013).

The World Health Organization developed the Self Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) in the early 1980s, as a part of a strategy designed to expand mental health services, mainly in developing countries. The instrument was created to screen mild and moderate common mental disorders, focused on syndromes with symptoms of depression and anxiety in primary health care settings. It was designed using binary response questions (i.e. options Yes/No) (Barreto do Carmo et al., Citation2018; World Health Organization, Citation1994). In other versions of the SRQ, four (4) questions were added scrutinizing psychotic symptoms in addition to one question on occurrence of seizures, which comprises the SRQ-25 version (Climent & de Arango, Citation1983; World Health Organization, Citation1994). Finally, the Spanish version, developed by researchers of the Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia), added other five (5) screening questions on abusive alcohol consumption, which comprises the SRQ-30 version. According to the authors, it took fewer than fifteen minutes to apply the SRQ-30 and could be provided by non-professional personnel trained on its application (Climent & de Arango, Citation1983).

In regard to common mental health disorders, the SRQ-20 instrument has versions in different languages (World Health Organization, Citation1994) and has been used in different scenarios, such as primary health care settings, community dwellers, or with victims of natural disasters and forced displacement (Lima et al., Citation1992; Paraventi et al., Citation2015; Tejada et al., Citation2014; Ventevogel et al., Citation2007). Nonetheless, the positive screening cut-off points for this scale have not been clearly established (Tejada et al., Citation2014), with scores ranging from > = 8 to > = 17 points, and even establishing gender specific cut-off points (Climent & de Arango, Citation1983; Mari & Williams, Citation1986; Paraventi et al., Citation2015; Ventevogel et al., Citation2007).

Among women who are victims of intimate partner violence, the most prevalent mental health problems are the depressive and the anxious syndromes (Bott et al., Citation2012), which is why the SRQ-20 has been considered as a useful instrument for screening and directing the treatment of women affected with these conditions. In Latin America, the SRQ-20 has been used to identify the presence of mental health problems of intimate partner violence in Paraguay and Bolivia (Ishida et al., Citation2010; Meekers et al., Citation2013); but its use on this specific populations has not been tested in Colombia (Tejada et al., Citation2014).

On the other hand, the SRQ instrument was designed as an early identification strategy of depression and anxiety syndromes in the context of primary health care following the DSM-3 standard definitions, with a cut-off score > = 11 points (Climent & de Arango, Citation1983). The questionnaire was routinely administered by non-professional staff as part of the task shifting strategy and to broadening the health service base (World Health Organization, Citation1994). However, in the last 30 years, changes in the diagnostic procedures (formerly the DSM-IV and currently the DSM-5), transformations of the health systems, as well as greater community sensitivity to mental health problems, have increased the demand for mental health services in Latin America (Minoletti et al., Citation2012). Hence, the initial objective of the instrument, valid at the time, is no longer valid and requires a new approach. A high percentage of women victims of intimate partner violence do not spontaneously consult health services despite the presence of significant affective symptoms or other health problems (Bott et al., Citation2012). The newly proposed SRQ-20 scale with Likert-type responses, applied by trained, non-professional personnel in the community, would allow an early approach and treatment of chronic mental health problems in women victims of intimate partner violence. In this sense, this study has two objectives i) to test the performance of the SRQ-20 screening instrument for common mental health disorders, in women who were victims of intimate partner violence (by male partners) and ii) to adapt and to test the SRQ-20 screening instrument using a Likert response approach.

Subjects and methods

This is an exploratory retrospective diagnostic accuracy study of the SRQ-20 screening mental health scale for primary health care settings. This study was part of the research ‘Evaluation of a Cognitive - Behavioral Intervention for victims of Intimate Partner Violence in Cali and Tuluá, Valle del Cauca’, funded by MinCiencias (Ministry of Sciences of Colombia, previously: ColCiencias), Contract No. RC-756-2016. The ethical approval was carried out by the Institutional Review Board on Human Ethics (in Spanish: CIREH) of Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia), through the Act No. 009-017, Internal Code 043-017. Additionally, the project protocol was approved by the institutional review board on human ethics and/or the scientific committee of each participating health care institution: Ladera Public Health Network in Cali, Rubén Cruz Veléz Public Hospital in Tuluá, Divino Niño Public Hospital in Buga and Renaseres IPS, a private clinic, in Cali.

In this research, participants were women who consulted the health services for being victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) by male partners, or who were identified as victims of IPV by male partners after their health assessment and who were referred to the psychosocial or mental health services of three basic care level public hospitals in the municipalities of Cali, Tuluá and Buga (province: Valle del Cauca, Colombia), and a private clinic for outpatient mental health services, in Cali. A convenience sample was collected sequentially (between November 2017 and August 2019) among women who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, who agreed to participate with a signed informed consent, at the four participating health institutions. A sample size of 66 subjects was calculated with the formulae for estimating the area under the ROC curve of 0.80, with an error of 0.10 and a prevalence of depression and/or anxiety of 70% in a single study sample (Zhou et al., Citation2011).

To evaluate the performance of the SRQ-20 instrument (both versions: the original one using binary answers and the Likert adapted version) (World Health Organization, Citation1994), the diagnostic gold standard was established by means of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) using the referenced cut-off points. The HSCL-25 was designed following the DSM-IV-R definitions for the psychiatric diagnosis (Mollica et al., Citation2004). The HSCL-25 instrument was applied to all study participants. Two subscales were combined for stablishing the gold standard for analyses of the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (Zhou et al., Citation2011):

Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25), subscale for the Major Depression Disorder.

Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25), subscale for General Anxiety Disorder.

The HSCL-25 instrument has been translated into Spanish and adapted to different cultures. It has been validated and utilized in studies of mental health conducted in Colombia, e.g. Santaella-Tenorio et al. (Citation2018) and Bonilla-Escobar et al. (2018) (Bonilla-Escobar et al., 2018; Santaella-Tenorio et al., Citation2018).

In order to adapt the original screening scale (i.e. the SRQ-20-binary), designed by Climent and de Arango of the Department of Psychiatry of the Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia) in 1983, to an instrument with item response options on a combination of Likert and ordinal scales; questions 1 to 20 (Q1 to Q20) of the original scale were adapted in two blocks of questions, as followed:

Answers on Ordinal Frequency Scale: The first block of questions has answers on an ordinal frequency scale of 5 options (0 = Never to 4 = Always). It includes questions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19 and 20 of the original SRQ-20 binary instrument.

Answers on Likert Scale: The second block of questions has responses on a Likert scale of 5 options (4 = Strongly agree to 0 = strongly disagree). It includes questions 10, 14, 15 and 16 of the original SRQ-20 binary instrument.

On the other hand, the SRQ-20-binary scale has responses type 1 = Yes and 0 = No, for different mental health symptoms. Thus, the responses of the SRQ-20-Likert version were divided to indicate if each symptom was never present or if the subject matched the description of each mental health symptom (agree and strongly agree). The SRQ-20-binary score ranges between 0 and 20 points. The concordance between the screening cut-off score (i.e. > = 11 points) of the SRQ-20-binary scale and the HSCL-25 gold standard (for major depression and/or general anxiety syndromes) was estimated using the kappa statistics and its 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) (Klein, Citation2018).

For describing the accuracy of each SRQ-20 version, analyses of the areas under the ROC curve were conducted with the total scores of the SRQ-20-binary and SRQ-20-Likert scales, respectively, against the combined diagnosis of syndromes of major depression and general anxiety as the dichotomic gold standard. The last diagnosis was based on the cut-off point of 1.75 proposed for the HSCL-25 scale (Mollica et al., Citation2004). Furthermore, for each cut-off decision threshold over the SRQ-20-Likert and SRQ-20-binary scales scores, the following accuracy indexes were calculated (Zhou et al., Citation2011): sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ration (PLR), negative likelihood ration (NLR) and percentage of correctly classified subjects, which appear in and , respectively. In order to have more analytical elements, a comparative analysis of the area under the ROC curve was performed for the two SRQ-20 scales studied: Likert version versus Binary version. The internal consistency of the scales was evaluated using the Cronbach’s alpha (Fayers & Machin, Citation2015).

Table 1. Performance of the SRQ-20-Likert scale in relation to a diagnosis of major depression and/or general anxiety.

Table 2. Performance of the original SRQ-20-binary scale in relation to a diagnosis of major depression and/or general anxiety.

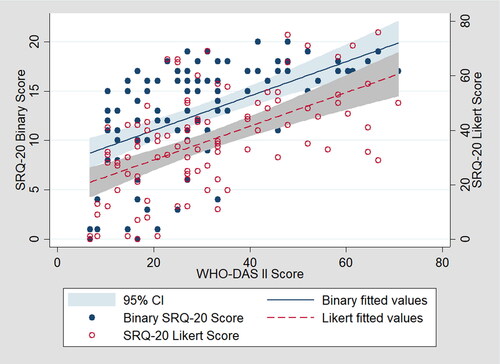

Additionally, the discriminant validity (Boateng et al., Citation2018) of both versions of the SRQ-20 was assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, comparing the corresponding SRQ-20 score between women with high and low scores (range: 0 to 57 points) of addition of the severe violence subscales (i.e. threat, physical and sexual) of the SVAWS instrument (Marshall, Citation1992; Burgos et al., Citation2012). The sum of the SVAWS severe violence subscales was split in two groups (high and low sums) according to the sample median. For assessing the convergent validity (Boateng et al., Citation2018), the correlations between the WHO-DAS II disability score (range: 0% to 100%) (Vásquez-Barquero et al., Citation2006) and each SRQ-20 version score were explored graphically with scatter plots and linear regression fit lines and the correlations were estimated using the Spearman’s coefficient and its 95%CI (Doménech, Citation2019). Statistical analyzes were performed using Stata® 14.2.

Results

This study included 100 women who were victims of intimate partner violence (by the current or a previous male partner aggressor), who signed the study informed consent, aged between 18 and 66 years old; the median age was 37 years (p25 = 28 and p75 = 44). 49 women lived in Cali, the province capital, 42 lived in Tuluá and 9 in Buga. 43 women were single, 12 married, 25 were living with her partner and 20 were divorced. Three women attained incomplete primary school or below, 31 had complete primary school, 11 had incomplete secondary school 42 had complete secondary school and 13 women attained higher education. Five women were studying, 35 were workers, 28 were independent workers and 32 were not working or studying. Seventeen women belong to the contributive private health system and 83 belong to the State subsidized health system. Regarding the violence victimization, women in the study show a wide range of scores in the sum of severe violence SVAWAS subscales, between 0 and 54 points with a median of 15 points (p25 = 5 points and p75 = 28 points).

According to the HSCL-25 gold standard, 89 women had a diagnosis of major depression and/or general anxiety and 11 women did not. On the other hand, 75 women had major depression and/or general anxiety and 11 women did not, according to the screening cut-off point > = 11 of the SRQ-20-binary scale; thus, the kappa statistic was 0.541 (95%CI: 0.339 to 0.743) indicating a moderate agreement.

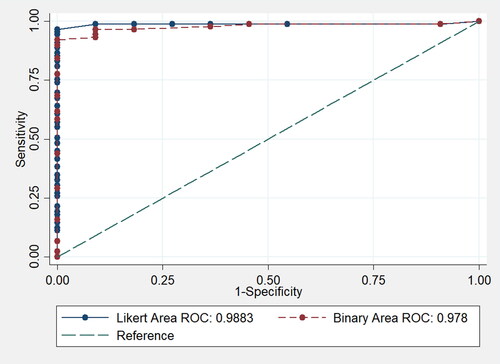

The area under the ROC curve of 0.988 (95% Confidence Interval = 0.946 to 0.999) indicates an excellent performance of the proposed SRQ-20-Likert scale (see ).

shows that the suggested cut-off points of the SRQ-20-Likert scale for the diagnosis of the two syndromes (major depression and/or general anxiety) was > = 8 points; because the best balance between sensitivity (98.9%) and specificity (90.9%) was achieved; also, with the highest percentage of appropriate classification of diagnoses in the study population (98.0%) and a high positive Likelihood Ratio (10.88). In addition, this is the cut-off point that takes most advantage of the higher sensitivity of the screening instrument before the sensitivity begins to decrease with the higher cut-off points.

shows that the original cut-off of > = 11 points suggested for the SRQ-20-binary scale, for the diagnosis of the two syndromes (major depression and/or general anxiety), had sensitivity of 84.3% and specificity of 100%. On the other hand, a decision threshold of > = 6 points renders higher sensitivity (96.6%), higher specificity (90.9%) and excellent positive Likelihood Ratio (10.63).

The area under the ROC curve of 0.978 (95% confidence Interval = 0.930 to 0.998) also indicates an excellent performance of the SRQ-20-original binary scale (see ), although this area is lesser than the area of the SRQ-20-Likert scale, proposed in this study (area = 0.988).

The internal consistency of the proposed SRQ-20-Likert scale works appropriately, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.939 (95% Confidence Interval > = 0.923, one tail). On the other hand, internal consistency of the original SRQ-20-binary scale is also good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.899 (95% Confidence Interval > = 0.873; one tail), showing that there is a significant difference in the reliability of the scales, in favour of the proposed new SRQ-20-Likert scale.

It can be observed that the areas under the ROC curve are very similar (see ), with the difference between them not being statistically significant (Chi2 = 2.02; p = 0.156). Keeping in mind the classification tables of previous scores, the performance of the SRQ-20-Likert scale is superior in terms of the balance between sensitivity (98.8%) and specificity (90.9%) for a cut-off score equal or higher than 8 (> = 8 points).

Regarding the discriminant validity, both SRQ-20 scales show significant results in the Wilcoxon rank-sum test indicating higher SRQ-20-binary scores (p = 0.008) and higher SRQ-20-Likert scores (p = 0.002) among women who underwent high levels of severe violence (threats, physical and/or sexual) according to the SVAWS subscales. Regarding the convergent validity, both SRQ-20 scales show significant Spearman’s correlation with the WHO-DAS II disability scale, the SRQ-20-binary has r = 0.622 (95%CI = 0.484 to 0.730) and the SRQ-20-Likert has r = 0.579 (95%CI = 0.431 to 0.697), although, without differences between scales on the correlation coefficients (p = 0.512). Additionally, shows the scatter plots and the linear regression fit lines for the correlations between WHO-DAS II and each SRQ-20 scale.

Discussion

The original cut-off score of the SRQ-20-binary scale, which was developed in Cali, Colombia (Climent & de Arango, Citation1983), was of 11 points or more. It is evident that in the group of female victims of intimate partner violence, the sensitivity of the cut-off score > = 11 points is only 84.3%, even though its specificity is 100%. This low sensitivity is unsuitable for a screening instrument/scale. This is the reason why other studies have utilized other cut-off scores above the initial 11 points (Mari & Williams, Citation1986; Lima et al., Citation1992; Paraventi et al., Citation2015; Ventevogel et al., Citation2007). Additionally, according to our results, the cut-off score of the SRQ-20-binary scale must be changed to > = 6 points, which shows higher sensitivity (96.6%), higher specificity (90.9%) and an excellent positive Likelihood Ratio (10.63).

The SRQ-20-Likert scale proposed in this study demonstrated a better ability for screening depressive and anxiety syndromes among women victims of intimate partner violence by male partners, compared with the original SRQ-20-binary scale. Additionally, the suggested cut-off score for this SRQ-20-Likert scale in contrast with the diagnoses of the two mental health syndromes is of 8 points or more (> = 8 points); because it achieves a better balance between the sensitivity (98.9%) and specificity (90.9%) of this screening instrument.

Moreover, the SRQ-20-Likert scale achieves the highest appropriate classification percentage (98.0%) of the two mental syndromes (which were identified in the study population), and a positive likelihood ratio of 10.8. Likewise, the internal consistency of the Likert scale is better than the internal consistency of the binary scale. Additionally, the proposed cut-off score (equal or higher than 8 points) allows for a higher sensitivity of the screening instrument, meaning the scale can be used in primary health care settings, or for supporting the assistance of female victims of intimate partner violence in the justice and protection sectors (Lennon et al., Citation2021).

One of the original main purposes of the SRQ-20 scale was to facilitate the identification of depressive and anxiety symptoms in the primary health care settings (Climent & de Arango, Citation1983). There were a lot of female victims of intimate partner violence who naturalize their situation, thus they do not consult early, leading to an identification of their mental health problems at a late and severe state (Bott et al., Citation2012). The adaptation of SRQ-20 scale to a Likert approach provides a greater chance to improve early identification of mental health problems in lower complexity health care settings (Tejada et al., Citation2014). Also, the scale could be timely applied by members of the community-based mental health services, who initially and oftentimes identify the situations of intimate partner violence in their respective communities (Lennon et al., Citation2021).

Regarding discriminant validity, both SRQ-20 scales could differentiate women with high and low levels of IPV victimization; a finding in line with the mental health consequences of IPV against women (Bott et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, both SRQ-20 versions have appropriate convergent validity with the WHO-DAS II disability scale, showing consistent findings with the complex relationships among the severity of intimate partner violence, mental health symptoms and disability levels (Sandoval et al., Citation2022).

The current study has some limitations: Firstly, the sample recruitment approach was purposive, and the sample size was relatively small; although, areas under the ROC curve, correlation coefficients and kappa index render significant estimates. Furthermore, the range of IPV victimization among study subjects was wide according to the SVAWS severe subscales; thus, the study sample would represent the range of IPV levels of women in the community. Secondly, the HSCL-25 gold standard was developed under the DSM-IV-R mental health diagnostic scheme (Mollica et al., Citation2004); thus, it is necessary to upgrade the analyses in future studies using the new DSM-5 diagnostic scheme.

Conclusions

The original binary SRQ-20 screening scale shows appropriate sensitivity and specificity levels to detect female victims of intimate partner violence by male partners, with moderate to severe symptoms of major depression and general anxiety, when working with a cut-off score of > = 6 points. This is a lower cut-off point in comparison with that originally suggested when the scale was developed in Colombia in 1983. The new proposed SRQ-20 scale with Likert-type response options uses a cut-off score of > = 8 points, which demonstrates better sensitivity and equal specificity as the original SRQ-20 scale. Thus, the SRQ-20 scales (both versions) show appropriate screening performance for common mental health disorders in women who are victims of intimate partner violence (by male partners) in primary health care settings; but further research is needed due to the purposive recruitment and small sample size of this study.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the study design, discussion of results and manuscript preparation. Initial statistical analyses were carried out by Andrés Fandiño-Losada. The supervision of the field work was carried out by Sara Pacichana-Quinayaz and Gloria Inés Rodas.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (225.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the management and research teams of the CISALVA Institute of the Universidad del Valle (Colombia) who participated in the project ‘Evaluation of a Cognitive - Behavioral Intervention for victims of Intimate Partner Violence in Cali and Tuluá, Valle del Cauca’, funded by MinCiencias, Contract No. RC-756-2016. The authors would like to thank managers and staffs of the health institutions participating in this study (Ladera Public Health Network and Renaseres IPS in Cali, Rubén Cruz Veléz Public Hospital in Tuluá, and Divino Niño Public Hospital in Buga) and to the patients who agreed to participate in this research.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was support by MinCiencias (Ministry of Sciences of Colombia), under Grant ‘Call for projects of Science, Technology and Innovation in Health– 2016, MinCiencias’ (Contract No. RC-756-2016).

References

- Barreto do Carmo, M. B., Santos, L. M. d., Feitosa, C. A., Fiaccone, R. L., Silva, N. B. d., Santos, D. N. d., Barreto, M. L., & Amorim, L. D. (2018). Screening for common mental disorders using the SRQ-20 in Brazil: What are the alternative strategies for analysis? Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1999), 40(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2016-2139

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

- Bonilla-Escobar, F. J., Fandiño-Losada, A., Martínez-Buitrago, D. M., Santaella-Tenorio, J., Tobón-García, D., Muñoz-Morales, E. J., Escobar-Roldán, I. D., Babcock, L., Duarte-Davidson, E., Bass, J. K., Murray, L. K., Dorsey, S., Gutierrez-Martinez, M. I., & Bolton, P. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral intervention for Afro-descendants’ survivors of systemic violence in Colombia . PloS One, 13(12), e0208483. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208483

- Bott, S., Guedes, A., Goodwin, M. M., & Mendoza, J. A. (2012). Violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries. Pan American Health Organization.

- Burgos, D., Canaval, G. E., Tobo, N., Bernal de Pheils, P., & Humphreys, J. (2012). Violencia de pareja en mujeres de la comunidad, tipos y severidad Cali, Colombia. Rev Salud Pública, 14, 377–389.

- Climent, C. E., & de Arango, M. V. (1983). Manual de psiquiatría para trabajadores de atención primaria. Organización Panamericana de la Salud.

- Mari, J. J., & Williams, P. (1986). A validity study of a psychiatric screening questionnaire (SRQ-20) in primary care in the city of Sao Paulo. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 148(1), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.148.1.23

- Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Bacchus, L. J., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Petzold, M., Astbury, J., & Watts, C. H. (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), e1001439. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439

- Doménech, J. M. (2019). Confidence interval for Pearson and Spearman correlation: User-written command cir for Stata [computer program]. V1.1.2. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. http://metodo.uab.cat/stata

- Fayers, P. M., & Machin, D. (2015). Quality of life: The assessment, analysis and reporting of patient-reported outcomes. John Wiley & Sons.

- INMLCF – Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses. (2022). Violencias en tiempos de COVID. Bogotá: INMLCF. Retrieved from https://www.medicinalegal.gov.co/violencias-en-tiempos-de-covid

- Ishida, K., Stupp, P., Melian, M., Serbanescu, F., & Goodwin, M. (2010). Exploring the associations between intimate partner violence and women’s mental health: Evidence from a population-based study in Paraguay . Social Science & Medicine (1982), 71(9), 1653–1661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.007

- Klein, D. (2018). Implementing a general framework for assessing interrater agreement in Stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 18(4), 871–901. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1801800408

- Lennon, S. E., Aramburo, A. M. R., Garzón, E. M. M., Arboleda, M. A., Fandiño-Losada, A., Pacichana-Quinayaz, S. G., Muñoz, G. I. R., & Gutiérrez-Martínez, M. I. (2021). A qualitative study on factors associated with intimate partner violence in Colombia. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 26(9), 4205–4216. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232021269.21092020

- Lima, B. R., Chávez, H., Samaniego, N., & Pai, S. (1992). Psychiatric disorders among emotionally distressed disaster victims attending primary mental health clinics in Ecuador. Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), 26(1), 60–66.

- Loxton, D., Dolja-Gore, X., Anderson, A. E., & Townsend, N. (2017). Intimate partner violence adversely impacts health over 16 years and across generations: A longitudinal cohort study. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0178138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178138

- Machisa, M. T., Christofides, N., & Jewkes, R. (2018). Social support factors associated with psychological resilience among women survivors of intimate partner violence in Gauteng, South Africa. Global Health Action, 11(sup3), 1491114. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1491114

- Marshall, L. L. (1992). Development of the severity of violence against women scales. Journal of Family Violence, 7(2), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00978700

- Meekers, D., Pallin, S. C., & Hutchinson, P. (2013). Intimate partner violence and mental health in Bolivia. BMC Women’s Health, 13(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-13-28

- Minoletti, A., Galea, S., & Susser, E. (2012). Community mental health services in Latin America for people with severe mental disorders. Public Health Reviews, 34(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391681

- Mollica, R. F., McDonald, L. S., Massagli, M. P., & Silove, D. (2004). Measuring trauma, measuring torture: Instructions and guidance on the utilization of the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma’s versions of The Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) & the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ). Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma.

- Paraventi, F., Cogo-Moreira, H., Paula, C. S., & de Jesus Mari, J. (2015). Psychometric properties of the self-reporting questionnaire (SRQ-20): Measurement invariance across women from Brazilian community settings. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.020

- Sandoval, L. M., Castro, E. S., Fandiño-Losada, A., Pacichana-Quinayaz, S. G., Lennon, S. E., & Gutiérrez-Martínez, M. I. (2022). Violence exposure and disability in Colombian female survivors of intimate partner violence: The mediating role of depressive symptoms. Rev Colomb Psiquiat, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2021.11.009

- Santaella-Tenorio, J., Bonilla-Escobar, F. J., Nieto-Gil, L., Fandiño-Losada, A., Gutiérrez-Martínez, M. I., Bass, J., & Bolton, P. (2018). Mental health and psychosocial problems and needs of violence survivors in the Colombian Pacific Coast: A qualitative study in Buenaventura and Quibdó. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 33(6), 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X18000523

- Tejada, P. A., Jaramillo, L. E., Sánchez-Pedraza, R., & Sharma, V. (2014). Revisión crítica sobre los intrumentos para la evaluación psiquiátrica en atención primaria. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina, 62(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v62n1.43759

- Vásquez-Barquero, J. L., Herrera, S., Vásquez, E., & Gaite, I. (2006). Cuestionario para la evaluación de discapacidad de la Organización Mundial de la Salud – WHO-DAS II (Versión española del World Health Organization DisabilityAssessment Schedule II). Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales.

- Ventevogel, P., De Vries, G., Scholte, W. F., Shinwari, N. R., Faiz, H., Nassery, R., van den Brink, W., & Olff, M. (2007). Properties of the Hopkins symptom checklist-25 (HSCL-25) and the self-reporting questionnaire (SRQ-20) as screening instruments used in primary care in Afghanistan. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(4), 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0161-8

- World Health Organization. (1994). A user’s guide to the self reporting questionnaire (SRQ). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1–84.

- Zhou, X. H., Obuchowski, N. A., & McClish, D. K. (2011). Statistical methods in diagnostic medicine. John Wiley & Sons.