ABSTRACT

Writing fieldnotes is an important part of ethnographic research. However, there is a striking lack of discussions about how different ways of producing fieldnotes may influence ethnographic research and meaning-making. The use of shorthand notation is sometimes mentioned as a tool to increase the speed and efficiency of note-taking, but I have not been able to find any discussions about when and how shorthand may be useful and appropriate for ethnographic fieldwork. This paper addresses this gap by discussing possible effects of using shorthand notation in ethnographic fieldwork on confidentiality, rapport, and power relations; researchers’ well-being and career opportunities; the amount of data produced; reflexive meaning-making; and linguistic meaning-making. Drawing on fieldnotes from an ethnographic study in which I used shorthand notation and ethnographic literature on the writing of fieldnotes, I argue that shorthand notation may be more or less useful and appropriate for different types of ethnographic research projects.

Introduction

The crucial role of fieldnotes in ethnographic research is today widely acknowledged (Walford Citation2009; Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011; Delamont Citation2018; Raggl Citation2018). More specifically, the writing of fieldnotes is often described as a first, crucial step of textualization in ethnographic research (Delamont Citation2018; Raggl Citation2018). However, while ethnographic writing has been extensively discussed since the 1980s, most of this discussion has centred on the writing of published research reports and scholars have only recently started to turn their attention to the writing and handling of fieldnotes. Fieldnotes have been described as a ‘muted medium’ (Lederman Citation1990, 72) that is surrounded by a ‘suspicious silence’ (Raggl Citation2018, 191) and thus constitutes a ‘noteworthy absence’ (Wolfinger Citation2002, 85). Leading contemporary scholars argue that more research is needed on the role of fieldnotes in ethnographic research (Delamont Citation2018; Raggl Citation2018). There is also a lack of practical guidance for novice ethnographers, both in the research literature and in research training programmes (Wolfinger Citation2002).

The present paper aims to address this gap by discussing practical and theoretical concerns related to the production of ethnographic jottings: brief written notes that are taken during field observations and that later serve as a memory support for constructing detailed fieldnotes (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011). More specifically, the paper discusses the value and appropriateness of using shorthand notation for producing jottings in different kinds of research contexts.

Methods

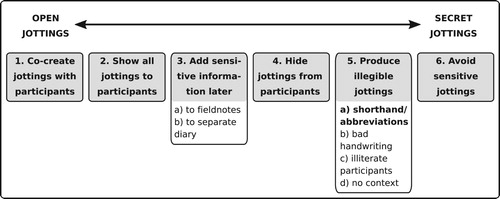

The discussion in this paper is empirically grounded in my personal experiences of using shorthand notation in an ethnographic study in a higher education context in Sweden (Lönngren, Citationforthcoming). In that study, I conducted more than 120 h of overt participant observations (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007) of lectures, tutorials, seminars, student presentations, student group work, and student welcome activities. In most of those observations, I used a Swedish shorthand notation system (the Melin system of stenography) to produce jottings. I primarily focused on observing actions, e.g.: What did teachers and students talk about and how? How did they relate to each other? What types of student behaviour and expressions were praised or scolded? I also took notes on, for example, physical settings; how students and teachers positioned themselves and moved in these settings; how they were dressed; and my own actions, experiences, and reflections during the observations. As soon as possible after each observed activity (typically by the next day), I expanded the jottings into digital fieldnotes, thus producing a more detailed description and adding personal reflections and preliminary ideas for analysis and interpretation (see for an example).

Figure 1. Extract from my shorthand jottings (top left), their translation into longhand (top right, translated from Swedish), and the extended fieldnotes that I wrote after the observation based on these jottings (translated from Swedish). S(?) indicates that I did not remember which student the description refers to.

For the data analysis for the original project (see Lönngren, Citationforthcoming), I imported all fieldnotes into the qualitative data analysis software MaxQDA. As I engaged in an open coding process for the original project, I noticed that my fieldnotes contained interesting reflections on my experiences of using a shorthand notation system. I therefore decided to systematically code my fieldnotes for any reflections related to the use of shorthand notation and thus identified 28 excerpts that were relevant for the discussion in this paper. I analysed these excerpts against the published literature on fieldnotes in ethnographic research (see list of references). I imported the selected titles (n=40) into MaxQDA and coded for any excerpts that could be related to the use of shorthand notation in ethnographic research in general and to my previously identified personal reflections in particular. I identified 47 relevant excerpts. I then performed a second round of coding of the excerpts from both my fieldnotes and the literature (see Appendix for the code book) and thus combined personal reflections about my own use of stenography in my ethnographic research with discussions related to ethnographic fieldnotes from the ethnographic literature. Finally, I performed axial coding to identify themes for the discussion in this paper.

Background

Fieldnotes and jottings

It is no wonder that fieldnotes are hard to think and write about: they are a bizarre genre. Simultaneously part of the “doing” of fieldwork and of the “writing” of ethnography, fieldnotes are shaped by two movements: a turning away from academic discourse to join conversations in unfamiliar settings, and a turning back again. As a kind of communication addressed primarily to oneself, they are unlike both the face-to-face but ephemeral sociability of fieldwork and the indirect but oddly enduring exchanges at home. (Lederman Citation1990, 72)

During field observations, researchers often produce handwritten jottings (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011), also called ‘scratch notes’ (Sanjek Citation1990b). The production of jottings has been described as a process of textual inscription: ‘A participant-observer jots down a mnemonic word or phrase to fix an observation or to recall what someone has just said’ and thus turns (inscribes) the observed action and discourse into written text (Clifford Citation1990, 51). These jottings serve as ‘preludes to full written notes’ (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011, 31), also called ‘fieldnotes proper’ (Sanjek Citation1990b) or simply ‘fieldnotes’ (the latter will be used in this paper).

Researchers differ in their approaches to writing jottings along at least three dimensions. First, some researchers include personal reflections while others try to exclude them as far as possible. Second, researchers may take jottings openly in the field and allow participants and/or researchers to read them, or they may make an effort to hide their jottings and/or make them illegible. Third, researchers use different strategies for speeding up their note-taking in order to record as much concrete detail and verbal quotes as possible. In my own research, when I was preparing for my first ethnographic fieldwork, I searched the literature for discussions related to these three dimensions of variation in the practice of producing jotting. I was able to find discussions about the pros and cons of in/excluding personal reflections from jottings and of showing/hiding jottings to/from participants and other researchers; but I was not able to find detailed descriptions of concrete approaches to speeding up one’s note-taking.

One strategy for faster note-taking that is sporadically mentioned in the literature is the use of shorthand notation (see e.g. Currall et al. Citation1999; Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011). Several well-known anthropologists and ethnographers have reported that they use(d) shorthand notation in their research (e.g. Franz Boas (see e.g. Hatoum Citation2016) and Susan Eliot (see e.g. Pelto Citation2013)), but there is a striking lack of discussions about the pros and cons of using shorthand notation in different research contexts. There is also a lack of concrete descriptions of practical experiences of using shorthand notation in ethnographic research projects. In the remainder of this paper, I aim to open up a space for these discussions. Throughout the paper, I focus exclusively on manual shorthand writing. While shorthand typewriters (e.g. Veyboard or Stenokey) may be an alternative to manual shorthand for professional stenographers, they require specialised keyboards and are therefore unlikely to be practical tools in ethnographic fieldwork.

I first provide a brief introduction to the history and practice of shorthand notation. I then describe shorthand notation as a useful tool for producing jottings at a reasonably fast pace and for keeping them secret from participants and other researchers. Finally, I discuss possible effects that the use of shorthand can have on ethnographic resarch.

Shorthand notation as a tool for faster writing

Modern shorthand notation systems (also called stenography) were first developed during the 16th and seventeenth century based on early methods for accelerated writing among Persians, Jews, Greeks, and Romans. Shorthand was further refined during the eighteenth century (Lovell Citation2015). During the nineteenth century,

stenography brought about an unsung communications revolution in the modern world. For the first time ever human beings had a technology that allowed the written word to keep pace with speech and accurately record it. … No wonder enthusiasts could promote stenography as a sign of human genius and progress. Its economic and civilizational benefits were almost too numerous to mention. (Lovell Citation2015, 1)

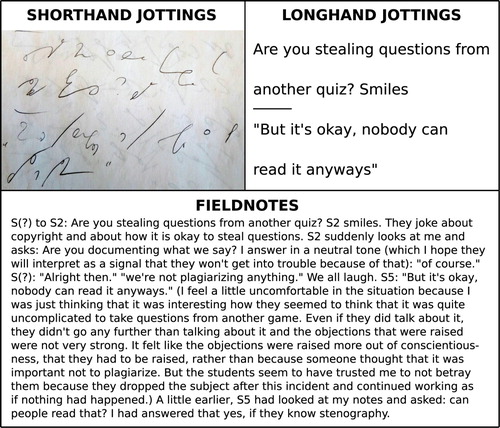

Similar to other shorthand systems, the Melin system consists of relatively simple symbols for consonants, consonant combinations, vowels, common word-endings, and abbreviations of common words. It is based on sounds (rather than spelling) in the Swedish language (i.e. words that sound similar but are spelled differently are written with the same stenographic symbols). The Melin system is designed to reduce the number of pen strokes needed to write Swedish words and to minimise the need for abrupt changes in pen stroke direction. For example, the symbol for the sound ‘A’ (or ‘a’ since no distinction is made between upper- and lowercase) in the Melin system is a short diagonal stroke and does not require the writer to lift the pen or change the direction of writing; thus, a single stroke is required to represent this sound. To write the Latin letter ‘A’, on the other hand, the writer needs to both lift the pen and change direction and a total of three pen strokes are needed (). It is this reduction in number of pen strokes and changes in writing direction that makes it possible to write faster and more efficiently than with ‘normal’ (longhand) writing.

Figure 2. Number and direction of pen strokes needed to write the sound ‘A/a’ in Melin stenography (left) and the Latin letter ‘A’ (right).

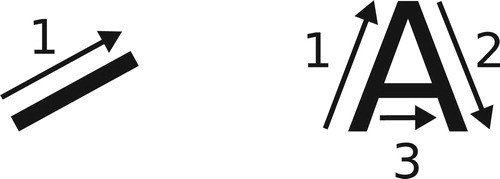

Professional stenographers are able to write up to 400 words per minute, but achieving such a high pace requires years of intensive training (Currall et al. Citation1999; Ito, Matsuda, and Shimojo Citation2015). Still, compared to other types of shorthand notation, the Melin system is considered to be relatively easy to learn since it is highly consequent and has few rules and few exceptions from these rules. In an overview over the system, the anonymous author claims that ‘already after a few days [of using the system], you will be able to replace your normal ‘longhand’ with stenography’ and ‘after approximately one month’, you will be able to ‘use stenography as a more efficient form of handwriting (…), without actively practicing to do so’ (“Melins system” Citationn.d., my translation, italics in original). My personal experience is that it was necessary to actively practice, but that a relatively small amount of training was enough to increase my speed of writing: I downloaded images of the Melin ‘alphabet’ from Wikipedia (Citation2017) and used these images together with a short introduction on how to use this alphabet (“Melins system” Citationn.d.). During nine weeks, I spent approximately one or two hours per day translating the text of a Swedish crime novel (Holt Citation2009) into the Melin system (). After those nine weeks, I was able to fluently take shorthand notes at at least the same speed as my normal handwriting (but of course still much slower than professional stenographers).

Figure 3. Extract from a crime novel (Holt Citation2009) with stenographic translation written between the lines.

Once I started taking stenographic notes regularly during my fieldwork, my writing-speed quickly increased and writing in stenography became an automatic process. In fact, already during my second day of fieldwork, I noticed that writing in stenography had become so automatic that I struggled to switch back to normal handwriting:

Today, I found myself trying to copy text from the whiteboard with normal letters, but I struggled to remember how to write them [despite the fact that I could see them written on the whiteboard]. Had to start over several times when I realised that I had used stenographic signs. I’ve also noticed that, sometimes, when I’m writing on the computer, I spontaneously want to write words as they sound [as is done in stenography] instead of using correct spelling. (fieldnotes)

Shorthand notation as a form of ‘Secret script’

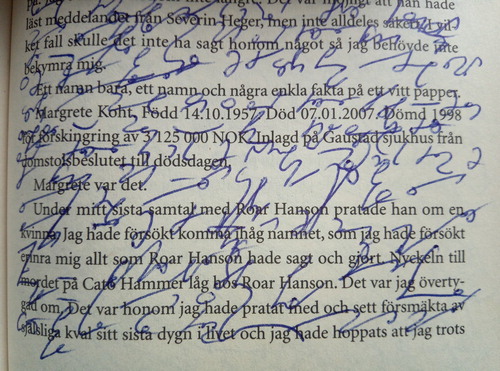

According to Hatoum (Citation2016, 260), some ethnographers use shorthand notations ‘as a form of ‘secret script’’. Similarly, Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw (Citation2011, 35) note that ‘abbreviations and symbols [, such as shorthand,] (…) make jotted notes incomprehensible to those onlookers who ask to see them and, hence, provide a means for protecting the confidentiality of these writings’. As a background for discussing possible effects of using shorthand notation, it is useful to locate shorthand notation on a continuum of more or less open approaches to producing jottings in ethnographic research ().

In some contexts, researchers may strive to produce jottings as openly as possible. They may even choose to co-create jottings with participants. For example, in a research project with children and young people who may face and/or reproduce unequal power relations, Russell (Citation2018, 157) allowed her participants to not only see her jottings, but also ‘contribute to them, scribble on them and edit them in situ’.

In other situations, researchers may want to show all jottings to participants, but avoid allowing participants to contribute to jottings. A common argument for this approach is that, while openness is important, participants may ‘self-censor’ jottings in an attempt to present themselves in a more positive manner (Russell Citation2018, 157). A common argument for showing all jottings to participants is that such a practice can contribute to creating trust and confidence. For example, Shah (Citation1979) not only allowed participants to ‘inspect’ original jottings and field works; Shah also translated notes to the participants’ local language to render them readable for participants who did not speak English. Similarly, Osgood (Citation1953; cited in Sanjek Citation1990a, 326) ‘deliberately read fieldnotes [and jottings?] back to informants’.

Some researchers argue that participants should be allowed to see all jottings, but that such openness also requires the researcher to be selective with regard to what can be written. Thus, researchers may allow participants to see all jottings that are produced in the field, but they may add sensitive information later, after leaving the field (see e.g. Walford Citation2009; Russell Citation2018). Such sensitive information can, for example, consist of researchers’ emotional reactions to, and personal reflections about, what they observe in the field. Researchers may choose to (a) integrate these types reflections in their regular fieldnotes or (b) write about them in separate research ‘diaries’ (Sanjek Citation1990b; Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011).

In yet other situations, researchers may feel a need to actively hide jottings from participants (e.g. Adair Citation1960), for example by retracting to ‘private spaces’ in the field, such as bathrooms or stairwells, to produce jottings out of sight from participants (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011; see e.g. Pollock Citation2004; Walford Citation2009). As Clifford notes (Citation1990, 54), ‘the ethnographic observer is always her- or himself observed’ and participants can be expected to be curious about the researcher’s notes. Participants may even try to ‘grab’ notebooks from researchers (e.g. as described by Bob Jeffrey in Walford Citation2009).

In some contexts, researchers may experience a need to uphold a higher level of secrecy than can be achieved by hiding jottings. Researchers may therefore choose to produce illegible jottings. As described above, using existing shorthand notation systems or self-devised (see e.g. Delamont Citation2018) systems of abbreviations (a) provides a means to producing jottings that are illegible – not only to participants but also to fellow researchers who are not able to read shorthand notation. Another means to producing illegible jottings is through bad handwriting (b), either accidentally (since the researcher is trying to write hurriedly), and/or on purpose (e.g. as described by Bob Jeffrey in Walford Citation2009). Jottings can also be illegible to participants if the latter are not able to read (c) or if the jottings do not contain sufficient information about the context in which observations are carried out (d). This difficulty of reading and understanding another person’s jottings is widely acknowledged in the anthropological community (e.g. Smith Citation1990; Sanjek Citation1990b; Van Maanen Citation2011).

Finally, there are situations in which researchers may find secrecy so important that they choose to completely avoid sensitive jottings, i.e. they choose to not write down sensitive information at all and instead keep that information exclusively in the form of ‘headnotes’ (Jackson Citation1990b).

In conclusion, the use of shorthand notation is just one of many different tools that can be used to increase the secrecy of jottings vis-à-vis participants and/or other researchers. Depending on the specific aims and contexts of a research project, shorthand notation may be more or less useful and appropriate. Due to the large variety among ethnographic research projects, it is not possible to formulate general rules for when (not) to use shorthand notation. Rather, I hope that this paper stimulates researchers to reflect upon and discuss whether or not shorthand could be a useful tool for specific projects – in much the same way as we today routinely discuss whether or not audio-recording may be a useful and appropriate tool for a specific project in a specific context.

Possible effects of using shorthand notation for producing jottings

Effects on confidentiality, rapport, and power relations

[The tutorium leader] glances at my computer screen. I try to turn [the computer] away a little – without making it too obvious that that’s what I’m doing, but it’s not really easy.

Because I used pseudonyms, changed the names of towns and villages, and even gave the compass a whirl when I wrote it, my efforts to protect informants have been successful at that basic level. Yet in the original fieldnotes for that village, even though we assigned everyone an identification number, the names of the individuals we knew best had a way of slipping in. (Wolf Citation1990, 352)

The possible effects of shorthand notation on rapport are less clear-cut. On the one hand, the fact that the researcher is making a visible effort to protect confidentiality may improve rapport and participants’ trust in the researcher. For example, upon noticing that I took notes in shorthand, one of my research participants exclaimed: ‘stenography!? (…) That’s what I call anonymization!’. In another situation, I was observing a project meeting of a group of five students who were developing a quiz. Suddenly, one of the students exclaimed (to another): ‘Are you stealing questions from another quiz?’ We all laughed together. One of the students then looked at me and asked: ‘Are you documenting what we say?’ I answered (in what I hoped to be a neutral tone and with a slight smile): ‘Of course!’ One student countered: ‘Alright then! (…) we don’t plagiarise anything here!’ One of the students concluded: ‘But it’s okay, nobody can read it anyways’. We all laughed together and the students continued to work as if nothing had happened (see fieldnote extract in ). If I had not used stenography, the students might have reacted differently. They might have been more careful regarding what to say and do in my presence and the described incident could have damaged rapport and future fieldwork. Other researchers have described situations in which participants’ reading of their jottings has damaged rapport, either because of the information contained in the notes (Adair Citation1960; cited in Sanjek Citation1990a, 325), or because of unintentionally harsh formulations in hurriedly produced jottings: ‘The danger is that when I’m speaking I can be polite, but the fieldnotes are in black and white’ (anonymous anthropologist, cited in Jackson Citation1990a, 23).

However, the illegibility of shorthand jottings may also be detrimental to building rapport. For example, Govoreanu (personal communication, 11 Sept 2019) has argued that the fact that her jottings were legible ‘saved [her] life’ during her fieldwork in activist camps in Mexico (see Govoreanu Citation2014): Her notes were found during a raid in the camp and it was the recognizability of her notes as anthropological jottings that prevented her from being suspected to be a hostile spy rather than a neutral or benevolent researcher. Other researchers have also reported that they have actively taken measures to render their fieldnotes accessible to participants to avoid being suspected of acting as ‘American spies’ (De Bois Citation1970; cited in Sanjek Citation1990a, 327), to ‘head off misunderstandings’ (Whitten Citation1970; cited in Sanjek Citation1990a, 326), or to ‘reassure’ participants (as described by Paul Connolly in Walford Citation2009, 124). Thus, in research contexts where participants may hold a high level of suspicion towards researchers, transparency may be more important for building rapport than protecting confidentiality. Researchers who feel a need to be transparent with their jottings may choose to use other tools for increasing the secrecy of jottings (as discussed above).

Even potential effects on power relations should be taken into account when deciding whether or not to use shorthand notation. For example, questions arise about who ‘owns’ fieldnotes and jottings – and thus who should be able to read them: Many anthropologists ‘[muse] about whether their notes [are] strictly private property or somehow [belong] to the native community’ (Jackson Citation1990a, 15). At the same time, many ethnographers feel that fieldnotes and jottings are the researcher’s private property, since they are ‘part of a world of private memories and experiences, failures and successes, insecurities and indecision’ (Bond Citation1990, 273) and since researchers devote so much time and effort to constructing them (Jackson Citation1990a; see also Raggl Citation2018). The use of shorthand notation in constructing jottings (and the effort of learning a shorthand notation system to be able to do so) may increase researchers’ feelings of private ownership of notes and thus contribute to unequal power relationships with participants.

Unequal power relations are common in ethnographic research, since the mere fact of being observed by a researcher may be ‘felt as a power struggle with researchers sitting there quietly (…) without showing a lot of themselves’ (Raggl Citation2018, 194). While it is true that even ‘the ethnographic observer is always her- or himself observed’ (Clifford Citation1990, 54), it is the participants’ actions that are being documented and scrutinised and the researcher remains in a position of relative power vis-à-vis the participants. Russell (Citation2018, 154) argues that ethnographers ‘should be aware and make (sic) steps to manage power differentials via their writing (in the field and beyond)’, for example by allowing participants to read and contribute to note-writing (see above). Similarly, Bond argues that not allowing participants to read and critically evaluate researchers’ notes may contribute to cultural domination and intellectual exploitation:

The critical voices of indigenous scholars are usually absent from the field of academic discourse. The integrity and accuracy of fieldnotes are rarely subjected to indigenous scrutiny. Under these and other conditions it becomes comparatively easy to appropriate the history of others as, at the same time, our history and sociology becomes increasingly theirs. (Bond Citation1990, 288)

From the above discussion, we see that the decision to use or not use shorthand notation for producing jottings may have profound effects on confidentiality, rapport, and power relations, but that these effects may play out differently in different research contexts. Hiouani (personal communication, 11 Sept 2019) suggested that one way to protect participants’ interests could be to engage them in a discussion about whether they would prefer jottings to be readable or not. The issues raised in this paper can be used as a background for such a discussion.

Effects on researchers’ well-being and career opportunities

It is today widely recognised that ethnographic fieldwork can be emotionally challenging for researchers (Atkinson and Hammersley Citation2007). Researchers often write about emotional challenges in their jottings and fieldnotes as a way of dealing with challenges during and after fieldwork:

Many anthropologists use fieldnotes, especially a diary, for what we can call the ‘garbage-can function’ – a private place to vent spleen, to have control, to speak in a civilised language for a while: “Fieldnotes allow you to keep a grip on your sanity”. (Jackson Citation1990a, 16)

Fieldnotes and jottings also depict researchers’ ‘private memories and experiences, failures and successes, insecurities and indecision’ (Bond Citation1990, 273). They can ‘reveal what kind of person one is: messy, responsible, procrastinating, exploitative, tidy, compulsive, generous’. They can also ‘reveal how worthless your work was, the lacunae, your linguistic incompetence, your not being made a blood brother, your childish temper … ’ (Jackson Citation1990a, 21). Consequently, many anthropologists and ethnographers experience ‘strong and ambivalent feelings about their notes. The subject of fieldnotes is clearly complex, touchy, and disturbing for most of us’ (Jackson Citation1990a, 9). Using shorthand notation in jottings allows researchers to freely relieve themselves from self-doubt and other negative emotions, to ‘spew up one’s spleen’ and thus ‘keep a grip on your sanity’. In my research, I certainly used my shorthand jottings for that purpose: Whenever I felt extremely upset about what I was observing, writing about these feelings helped me to keep the feelings to myself and to quickly let go of them in order to be able to fully focus on my observations again – rather than carrying the emotions with me until leaving the field at the end of the day.

A rather unexpected effect of using shorthand notation on my personal well-being was that it helped mediate stress and anxiety during my fieldwork. In the field, I often experienced a high level of stress and a constant worry that I would make serious mistakes that could render my data useless, damage field relations so that future data collection would become impossible, or lead to negative consequences for participants. In those situations, using shorthand notation provided me with a sense of, at least, being in control of something: while everything else seemed insecure and uncertain, at least my note-taking was under control. While this certainly was an illusion of control, it did help me to persist throughout my fieldwork and to motivate myself to observe yet another lecture or seminar when I already felt exhausted and overwhelmed. As soon as I started to produce shorthand jottings, I forgot about feeling insecure and tired and was able to fully focus on what was happening around me. I also experienced note-taking in shorthand as an enjoyable and relaxing activity in itself, which contributed to my overall well-being in the field.

In addition, since shorthand notation systems are designed to reduce the number of pen strokes and abrupt changes in writing direction (see above), shorthand writing may be much more ergonomic than longhand writing. In my research, I sometimes had to use longhand notation for producing jottings (for example when observing activities in English, for which the Melin system is not particularly useful). In those situations, I clearly noticed a higher level of wrist pain during and after note-taking which forced me to take breaks and thus hindered me from taking notes continuously. However, as mentioned above, using shorthand for producing jottings could also have dramatic effects on researcher’s physical safety, since illegible jottings may raise suspicions that researchers act as hostile spies (e.g. De Bois Citation1970; cited in Sanjek Citation1990a, 326; Govoreanu, M., personal communication, 11 Sept 2019).

Finally, shorthand notation may have an effect on researchers’ career opportunities, since it may protect jottings from being ‘stolen’ by other researchers. For example, the following situation would most likely not have occurred if Obbo had written his notes in shorthand:

At an international meeting [a] colleague read a well-received paper. Some sections sounded like verbatim passages from my fieldnotes. I was flabbergasted as I listened. (…) My research assistant told me that a week before the meeting this man had sat down in my office and read my fieldnotes. My research assistant had thought that he wanted to chat and did not question him. (Obbo Citation1990, 296–297)

Effects on the amount of data produced

Using shorthand notation for producing jottings may influence the amount of data that is produced in an ethnographic project in two ways. First, as discussed previously, a faster pace of writing and better ergonomics can increase the amount of jottings produced per time spent in the field. Using shorthand notation can also increase the quality of jottings since it allows researchers to include more descriptions of concrete details as well as verbal quotes, both of which are important for producing high quality jottings and fieldnotes (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007; Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011). However, in my own research, I also found that translating shorthand jottings into digital fieldnotes took more time than translating longhand notes – which in turn may have forced me to work long hours and overall spend fewer hours in the field. The slower pace of translation is mostly due to the fact that reading shorthand may be challenging even for the author themselves. In fact, I sometimes spent up to a few minutes trying to decipher a word or a phrase that I had written just the day before. Similarly, the cultural anthropologist Franz Boas experienced difficulties in reading his shorthand notes: ‘I wrote all my notes in shorthand. I hope that I will be able to read them’ (quote from a letter to his sister Toni in 1923; cited in Hatoum Citation2016, 222). Hatoum (Citation2016, 227) explains:

In a world of signs in which accuracy and detail are key – where it really matters whether you are facing a short or a long line or a dome-shaped sign; whether this sign is placed horizontally, vertically, left, or right turned; whether a sign is placed on, above, or underneath a line – in such a world it really matters if Boas presents you with ‘a something’ that basically could be any one of these.

Effects on reflexive meaning-making

I have argued that using shorthand notation for producing jottings may limit the number of hours a researcher spends in the field since jottings may be difficult to read and thus take more time to translate into digital fieldnotes. However, in my research, I also experienced this slow translation process as productive since it forced me to reflect on the content of my notes rather than automatically copy text into a digital format. In fact, my fieldnotes contain a large amount of analytic reflections and I believe that the slower translation process has facilitated continuous preliminary analysis in parallel with on-going fieldwork – and thus progressively more focused observations and note-taking. Similarly, Sanjek (Citation1990b, 114) suggested that ‘sitting and thinking at a typewriter or computer keyboard brings forth the ‘enlarging’ and ‘interpreting’ that turns ‘abbreviated jottings’ and personal ‘shorthand’ into fieldnotes’. It seems reasonable to assume that more time spent ‘sitting and thinking’ may lead to more detailed and reflective fieldnotes.

However, using shorthand notation may not only have an effect on the amount of interpretive meaning that is created in fieldnote-writing; it may also have effects on the kinds of meaning that are created. This is so because writing jottings and fieldnotes is an inherently interpretative process:

In writing a fieldnote, then, the ethnographer does not simply put happenings into words. Rather, such writing is an interpretive process: It is the very first act of textualizing. Indeed, this often “invisible” work – writing ethnographic fieldnotes – is the primordial textualization that creates a world on the page and, ultimately, shapes the final ethnographic, published text. (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011, 20)

feelings of personal comfort, anxiety, surprise, shock, or revulsion are of analytic significance. In the first place, our feelings enter into and colour the social relationships we engage in during fieldwork. Second, such personal and subjective responses will inevitably influence one’s choice of what is noteworthy, what is regarded as strange and problematic, and what appears to be mundane and obvious. (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007, 151)

One could argue that the effects of restricting what can be written in jottings is be minimal since researchers can choose to include sensitive information in fieldnotes upon leaving the field. However, if we agree that ‘one should aim to make notes as soon as possible after the observed action’ and that ‘the ideal would be to make notes during actual participant observation’ (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007, 143), then we also have to agree that this applies to sensitive information and personal reflections as much as it applies to more neutral, descriptive information.

Some researchers, however, do not agree with Atkinson and Emerson et al. regarding the need to take notes about one’s personal reactions. For example, Delamont argued that blending descriptive notes with personal notes may lead researchers to focus too much on themselves and lose sight of the main focus of the research, i.e. the participants (Delamont Citation2018).

Effects on linguistic meaning-making

Last but not least, using shorthand notation may have effects on linguistic meaning-making. As described by Raggl (Citation2018, 191), producing jottings ‘can be seen as translating experiences into a text’. From this perspective, shorthand and longhand notation can be viewed as different ‘languages’ into which researchers can translate their field experiences. These different languages can lead to the construction of different meaning and, therefore, the choice between shorthand and longhand notation may have effects not only on reflexivity, but also on linguistic meaning-making.

While more research is needed on the effects of different forms of shorthand and abbreviation systems on linguistic meaning-making, we can use the characteristics of the Melin system to suggest a few ways in which it may influence meaning produced in jottings. First, in Melin shorthand (as well as in many types of abbreviations), word endings are often omitted and certain information may thus be lost, for example about whether a word was meant to be written in pluralis/singularis or in definite/indefinite form. In my research, I had to make a conscious effort to clarify word endings in verbal quotes in order to avoid this type of information loss. Still, when translating my jottings into fieldnotes, I noticed that I had not always succeeded in doing so and I could no longer be sure that the quotes I had written down were actually exact verbal quotes. Second, most shorthand notation systems do not distinguish between upper- and lower-case letters, nor between spelling variations. While these distinctions may be irrelevant for most descriptions and verbal quotes, it may be important for copying written text from a field context to jottings. For example, in my classroom observations, I copied everything that was written on the whiteboard using longhand notation in an effort to preserve as much as possible of the original layout. I found that capitalisation of certain words, for example, could provide important hints about what themes and concepts were constructed as important in the classroom discourse.

Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to contribute to much-needed scholarly discussions about the role of fieldnotes and jottings in ethnographic research. I have discussed practical and theoretical concerns that may be relevant for choosing to use – or not to use – shorthand notation for producing jottings in different kinds of research contexts. I have argued that using shorthand notation can be one of several approaches to increasing the secrecy of jottings vis-à-vis participants and/or other researchers and that the usefulness and appropriateness of shorthand notation depends on the specific aims and contexts of a research project. I have also discussed possible effects of using shorthand notation on confidentiality, rapport, and power relations; researchers’ well-being and career opportunities; the amount of data produced; reflexive meaning-making; and linguistic meaning-making. I hope that these discussions can support (particularly novice) ethnographers in taking well-informed decisions about how to produce jottings in a specific research study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adair, J. 1960. “Un Pueblo G.I.” In In the Company of Man: Twenty Portraits by Anthropologists, edited by J. Casagrande, 489–503. New York: Forgotten Books.

- Atkinson, P. 1992. Understanding Ethnographic Texts. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Atkinson, P., and M. Hammersley. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. London: Routledge.

- Bond, G. C. 1990. “Fieldnotes: Research in Past Occurrences.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 273–289. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Clifford, J. 1990. “Notes on (Field)Notes.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 47–70. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Currall, S. C., T. H. Hammer, L. S. Baggett, and G. M. Doniger. 1999. “Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methodologies to Study Group Processes: An Illustrative Study of a Corporate Board of Directors.” Organizational Research Methods 2 (1): 5–36.

- De Bois, C. 1970. “Studies in an Indian Town.” In Women in the Field, edited by P. Golde, 221–238. Chicago: Adeline.

- Delamont, S. 2018. “Fieldnotes and the Ethnographic Self.” In Ethnographic Writing, edited by B. Jeffrey, and L. Russell, 33–44. Gloucestershire, UK: E&E Publishing.

- Emerson, R. M., R. I. Fretz, and L. L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd ed. Chicago: UCP.

- Forge, A. 1972. “The Lonely Anthropologist.” In Crossing Cultural Boundaries: The Anthropological Experience, edited by S. T. Kimball, and J. B. Watson, 292–297. San Francisco: Chandler.

- Govoreanu, M. 2014. “Ciudadanías en Plantones en la Ciudad de México: de la Construcción Sociolegal de las Desigualdades a las Prácticas Vernáculas. Etnografía de Desigualdades y Segregaciones a Partir de las Movilidades.” In Ciudades Latinoamericanas: Desigualdad, Segregación y Tolerancia, edited by M. Di Virgilio, and M. Perelman, 135–157. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. Great Britain: Routledge.

- Hatoum, R. 2016. “”I Wrote all my Notes in Shorthand”.” In Local Knowledge, Global Stage, edited by R. Darnell and F. W. Gleach, 221–272. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Holt, A. 2009. 1222 över Havet. Translated by M. Sjöwall. Falun: Piratförlaget.

- Ito, T., T. Matsuda, and S. Shimojo. 2015. “Functional Connectivity of the Striatum in Experts of Stenography.” Brain and Behavior 5 (5): 1–12.

- Jackson, J. E. 1990a. “‘Deja Entendu’: The Liminal Qualities of Anthropological Fieldnotes.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 19 (1): 8–43.

- Jackson, J. E. 1990b. “‘I Am a Fieldnote’: Fieldnotes as a Symbol of Professional Identity.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 3–33. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Lederman, R. 1990. “Pretexts for Ethnography: On Reading Fieldnotes.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 71–91. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Lönngren, J. forthcoming. “Exploring the Discursive Construction of Ethics in an Introductory Engineering Course.”.

- Lovell, S. 2015. “Stenography and the Public Sphere in Modern Russia.” Cahiers du Monde Russe 56 (2-3): 291–325.

- Melin, O. W. 1892. Lärobok i Förenklad Snabbskrift. Stockholm: A.B.Nordiska Bokhandeln.

- Melin, O. W. 1927. Stenografiens Historia. D.1. Stockholm: Nord. Bokh. i distr.

- Melinska Stenografförbundet. n.d. “Melinska Stenografförbundet.” Accessed June 30. http://www.stenografi.nu/index.php.

- “Melins system”. n.d. “Melins system.” Accessed 7 March. http://melinsstenografi.nu.

- Obbo, C. 1990. “Adventures with Fieldnotes.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 290–302. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Osgood, C. 1953. Winter. New York: Norton.

- Pelto, P. J. 2013. Applied Ethnography: Guidelines for Field Research. Abingdon & New York: Routledge.

- Pollock, M. 2004. Colormute: Race Talk Dilemmas in an American School. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Raggl, A. 2018. “Fieldnote Issues, Collegial Support and Collaborative Analysis.” In Ethnographic Writing, edited by B. Jeffrey, and L. Russell, 191–200. Gloucestershire, UK: E&E Publishing.

- Russell, L. 2018. “Competing Power Differentials in Ethnographic Writing; Considerations When Working with Children and Young People.” In Ethnographic Writing, edited by B. Jeffrey, and L. Russell, 153–170. Gloucestershire, UK: E&E Publishing.

- Sanjek, R. 1990a. “Fieldnotes and Others.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 324–340. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Sanjek, R. 1990b. “A Vocabulary for Fieldnotes.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 92–121. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Shah, A. M. 1979. “Studying the Present and the Past: A Village in Gujarat.” In The Fieldworker and the Field: Problems and Challenges in Sociological Investigations, edited by M. N. Srinavas, A. M. Shah, and E. A. Ramaswamy, 29–37. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, R. J. 1990. “Hearing Voices, Joining the Chorus: Appropriating Someone Else’s Fieldnotes.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 356–370. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Van Maanen, J. 2011. Tales of the Field. On Writing Ethnography. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Walford, G. 2009. “The Practice of Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes.” Ethnography and Education 4 (2): 117–130.

- Whitten, N. E. Jr.. 1970. “Network Analysis and Processes of Adaptation Among Ecuadorian and Nova Scotian Negroes.” In Marginal Natives: Anthropologists at Work, edited by M. Freilich, 339–402. New York: Harper and Row.

- Wikipedia. 2017. “Stenografi.” Accessed July 4. https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stenografi#Melins_system.

- Wolf, M. 1990. “Chinanotes: Engendering Anthropology.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, edited by R. Sanjek, 343–355. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Wolfinger, N. H. 2002. “On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (1): 85–93.