ABSTRACT

In this article, inspired by the idea of using data to think with theory [Jackson, A., and L. Mazzei. 2012. Thinking with Theory in Qualitative Research: Viewing Data Across Multiple Perspectives. London: Routledge], we explore how our ethnographic visual data will be ‘thought’, ‘theorised’ and verbalised using concepts such as the photo elicitation method, punctum and the decisive moment. These concepts are ‘plugged in’ to the data as we explore what new aspects the concepts produce for our analysis. In our ethnographic data, children photographed their ordinary afternoons during after-school activities. As to the analysis, our challenge is twofold: firstly, how does one verbalise photographs and, secondly, how can one write about photographs, specifically those taken by children. Following Jackson and Mazzei, the specific concepts were ‘arrested’ in order to help us extend our analysis.

Introduction

Jackson and Mazzei (Citation2012, 1) pick up the concept of ‘plugging in’ from Deleuze and Guattari (Citation2011, 5; Deleuze Citation2004, 7–9; Salo Citation2015, 181–183) as they urge qualitative researchers to use data to think with theory. They outline their method as ‘a plugging of theory into data into theory’. This means that plugging in produces a sort of circuit that creates a different relationship between theory and data: they constitute one another and in doing so create something new. Our analysis follows the idea of plugging in to create something ‘new’ as we explore what the concepts of photo elicitation (Collier Citation1957), punctum (Barthes [Citation1981]Citation2000) and the decisive moment (Cartier-Bresson [Citation1952] Citation2014) produce in the analysis while theorising with the data. The method of ‘using data to think with theory’ means developing and experimenting with approaches emerging with the research process, rather than ‘applying’ methods designed and decided in advance (Pedersen and Pini Citation2017, 3). This emerging quality, as we think, is the very nature of ethnography and the quality that brings the practice of ethnography to life. In a similar vein, Price and Wells (Citation2015, 28–29) point out that theory contributes to ‘a system or set of tools’ whereby we can understand the ideas and processes of photographing better.

In our ethnographic research, the data consist of photographs, and the photographs were produced when children were given digital cameras and asked to photograph their ordinary afternoons. By the term ‘ordinary’ we mean things that happen in everyday life; a shifting assemblage of practices and practical knowledges, a scene of ‘liveness and exhaustion’ (see Stewart Citation2007, 1–2). In this context, we track down the ‘ordinariness’ of children’s after-school activities and the ways this is pictured in their photos. We theorise with our photographic data; how the visual ethnographic data and the ordinary afternoons transform into research writing, while simultaneously acknowledging a twofold methodological challenge: firstly, how to verbalise photographs and, secondly, how to write about the photographs particularly those taken by children.

In Finland, the after-school activities are organised primarily for first- and second-year pupils (age 7–9) and secondly for children with special needs (grades 3–9, age 9–16). Participation is voluntary and the activities are arranged during children’s leisure time. What is remarkable is that the after-school activities are not formally organised by school and there are various organisers, though the state is responsible for the activities.

The research is set in the context of after-school activities at a time, when new investment thinking is gaining ground in Finland, invoking increased interest in children’s extra-curricular activities from the standpoint of organised learning and education. The after-school question is incorporated into state politics, where emphasis is placed on organising children’s use of after-school time more efficiently and on strengthening the child’s individual competences and social capital. There is a close link established between focusing on children, on the one hand, and economic growth, efficiency and competitiveness, on the other (Strandell Citation2013). Consequently, the after-school activities have become an integral part of the ceremonious politics of continuous learning.

Skeggs (Citation2001, 426) points out that: the use, the politics of the researcher and the context in which interpretation takes place is what defines the operative type of ethnography in play at any one time. The article is motivated by the education policy encompassing children’s after-school activities, and ethnography is used in order to understand the friction at the interface between the institutionally organised activities for children and the creative power children themselves have while creating their leisure activities. We are interested in how children themselves ‘do’ their afternoons, that is, how they photograph and describe their afternoon activities. This ‘doing’ turned out to be even more intriguing while children started to ‘discover’ their afternoons; see them from novel and innovative visual angles. The way a digital camera was functioning was a new and inspiring medium to them as they were not able to write yet. This inspiration continued when they told stories about their pictures, like the special shade of a green leaves or the games they shared. These were captivating discoveries for both children and researchers alike.

Photographs in research with children

During the last two decades, the use of photographs in research with children and young people has become more common in different disciplines. Visual methods are commonly seen as a visual voice that brings out the things, persons and events as well as the very places and spaces important to children (Riessman Citation2008; Burke Citation2008). In addition, these are things that adults often fail to notice. As for ethnographic research, visual methods such as photography are advantageous as they enable participants to share their perspectives and feelings with researchers (Clark-IbáÑez Citation2004), especially when children themselves can decide what to photograph, and how to photograph it (Rutherford Citation2019).

Researchers often invite children and young people to take pictures of their everyday lives, for example: ‘all about me’ (Cooper Citation2017; McLaughlin and Coleman-Fountain Citation2019); ‘my way to school’ (Bourke Citation2017; Kullman Citation2012); the best places during the school day or free time (Barker and Smith Citation2012; Änggård Citation2015); what are fun or boring things in preschool (Almqvist and Almqvist Citation2015); or the ‘things that matter’ (Varvantakis, Nolas, and Aruldoss Citation2019). Some researchers regard photos as a useful addition to interviews, while the transcripts become coded and categorised more like traditional interview methods in order to find out larger themes, or alternatively to seek a deeper understanding about the participants’ thoughts, motives and perceptions on which to form conclusions (Almqvist and Almqvist Citation2015; Torre and Murphy Citation2015). Researchers analysing photos simultaneously with interview transcripts typically attend to the symbolic characteristics of the photos such as framing, foregrounding and backgrounding, and what is included or left out of photos (Torre and Murphy Citation2015; see Dennis and Huf Citation2020). Ethnographically speaking, our focus is on how children construct their organised after-school cultures in their photos and the meanings they attribute to them during photo talks.

In our research, the photos are a kind of starting point, not an addition to the interviews. The photo elicitation method emerged as an important component when children were invited to photograph their ‘ordinary afternoons’ and when they were afterwards asked to tell about the pictures they had taken. While children tell about their photos – and simultaneously produce their photo talks – they examine their own doings not only as a participant of the after-school activities, but also as a ‘photographer’. For example, how they concentrate on framing a picture often was of serious concern.

The photographs made it possible to start talking about things not so easily seen or said, not to mention written, while our participants could not yet write themselves. Furthermore, the cameras influenced the children’s actions and the research process as the cameras invited the children to engage in explorative activities in their surroundings (see Kullman Citation2012; Änggård Citation2015). Änggård (Citation2015) writes how the children in her research did not use the camera for taking pictures, but for a play activity – how they pretended they were watching a TV. In episodes like this, the camera itself and its functions seemed to play an active role. In our research, the ways by which the world is discovered and surprisingly framed by the cameras are also great moments. From the socio-constructivist point of view, children are not merely constructors of their social and discursive worlds (James, Jenks, and Prout Citation1998), but also of the material, non-human dimensions, which are part of their worlds and intra-action (Barad Citation2007).

The methodological challenge while ‘doing’ visual methods is: How does a researcher catch up with the discoveries and understandings that children are involved in? Methodologically, where children are concerned, it is essential to underline the children’s own interpretations of their photographs, as this is how discussions open up new dimensions of the data (Barker and Smith Citation2012; Bourke Citation2017). Therefore, working communication and understanding between the researcher and the participants are seen as paramount just as pointed out, among others, in the ethnographic research of Clark-IbáÑez (Citation2004), Cooper (Citation2017) and Kullman (Citation2012).

While analysing images, it is important to evaluate what is both seen and unseen (Fischman Citation2001; Torre and Murphy Citation2015). Children in particular make the kind of observations about their pictures that are not even visible to a researcher (Fischman Citation2001). Sometimes it may also happen that the very point of a photo – nevertheless described by a photographer – is not even within the frame of a picture (Barker and Smith Citation2012). When children narrate images captured by themselves, their voice and authority increase and the researcher’s bias diminishes, since much of the significance of the images is known to the photographer alone (Lapenta Citation2011; see also Barley and Russell Citation2019). It seems that photographing takes children by surprise and, while photographing, they come to know their worlds differently – and from a new angle – so that what they are doing makes more sense than they realise (see Bourdieu Citation1990, 69). In a word, this is something that goes beyond the ordinary and reaches for the extraordinary.

Sometimes children and young people may be quite challenged in finding words to describe their photographs. Therefore, it is methodologically, not to mention ethnographically, noteworthy who makes or selects images and which photos are used in dialogues with a researcher and participants. (Barker and Smith Citation2012; Lapenta Citation2011). This process conveys practical, methodological as well as ethical issues (Woolhouse Citation2019).

We ask how to analyse children’s photographs and this means that we have to explore how to write about our visual ethnographic data and how to solve the problem methodologically. This article is based on the premise that photographs taken by children convey valuable insights into their worlds, their cultures, thoughts, experiences and meaning making (Barker and Smith Citation2012; Luttrell Citation2010). We are guided by Edwards (Citation2012, 22) as she promotes how ‘photographs cannot be understood through visual content alone but through an embodied engagement with an affective object world, which is both constitutive of and constituted through social relation’.

Data: good photos, art photos and secret snapshots

The visual ethnographic data were produced with children participating in after-school activities organised in three different schools in the Helsinki metropolitan area for approximately 4–5 weeks in each. The fieldwork was carried out during November–December (17 interactions), January–March (20 interactions) and May (10 interactions) in the 2009–2010 academic year. The children engaged in the research (124 in total; 70 girls, 54 boys) were mostly first and second graders (age 7–9), a few were third graders (age 9–10) and two of the fifth and sixth graders (age 11–12). Kristiina was responsible for producing the data in the field, as this is part of her dissertation. She joined the children in their after-school activities as a participant observer, gave the digital cameras to the children for the afternoon, was hanging around the grounds, wrote field notes and discussed the images with the children. Every child photographed for one whole afternoon, and most of the time four cameras went into use simultaneously. The children were invited to photograph their ordinary afternoons, their favourite places or places they disliked, and things they did during the supervised after-school activities on school premises. They were told that they could take as many pictures as they wanted and most of them chose to take 10–40 (the data comprise 4952 photographs). As an ethnographic arrangement, this was rather traditional while guided this way by a researcher. In the first place, the researchers had the role of the ethnographer, whereas if arranged again, we would reconsider the children more like auto-ethnographers of their organised afternoons.

Afterwards, a day or a week later, the images were viewed from the computer screen together with each photographer in turn. Some of the children had not used a digital camera before this study. The children themselves frequently took over the browsing when they were explaining the images. In the end, each photographer was asked to choose five images (in terms of data, 620 photographs in total) best representing their afternoon and the one they would later receive in print. Moreover, children were asked to tell why they chose the pictures they did. We have called ‘photo talks’ those discussions we had with the children concerning the detailed stories of their photographs. These talks and stories were recorded (103 in total) or written down (21 in total), partly transcribed; in addition, notes were made. Overall, the data is composed of photographs taken by the children, children’s photo stories and photo talks, participant observations and field notes. All the names of the photographers are pseudonyms in the text.

A written consent was requested from parents or caregivers for their children to participate in the study and to share their images. Additionally, children who did not take photographs had permission to appear in other children’s photos, with only a few parents refusing consent. Finally, when the children had chosen their five images, once again we made sure that other children visible in the image had permission from home for publication. Although children themselves participated in the research process with enthusiasm, ethical considerations required seeking parental consent (TENK Citation2019).

In the data, there are photos of friends, activities such as playing football, different mascots and toys, the schoolyard and the surrounding nature. Some of the children would take several snapshots of the same target, exploring various backgrounds and assembling the images. For example, the children named photographs depicting one or two children looking calmly at the camera as ‘good photos’, while describing others that were one of a kind as ‘art photos’, for example an image of pencil sharpener waste on the table. Some children tended to take ‘stolen pictures’ (see Delahaye Citation1999) waiting very quietly to be able to photograph without other children’s knowledge because they thought they could get better images that way. Institutional environments, though, constitute a challenge, as children are able to photograph only places they have access to (Barker and Smith Citation2012; Lehto and Eskelinen Citation2020). It should be noted, however, that even though childhood is a time most often shaped by institutions, such as in school and after-school activity setting, children themselves ‘do’ their afternoons (James, Jenks, and Prout Citation1998). These ‘doings’ in particular were under our ethnographic gaze. This is not to say, however, that gazing as tightly and tenaciously as ever, we could, as adults, totally share children’s doings on their own level. Nevertheless, as researchers, we could take a position vis-à-vis the children that is more aware than most adults would be in this situation (see Thorne Citation1994).

Methodology: using photographic data to think with theory

We approach the data firstly through photo elicitation (Collier Citation1957). Photo elicitation is a research method, in which photographs are used as a basis for photo talks between researchers and participants, as the method enables participants to share their perspectives and feelings (Clark-IbáÑez Citation2004). In our analysis, the photo elicitation method helps bring up the hidden views of the young photographers. Though for us, as ethnographers, the photo elicitation method does not mean the mere production of data; it is rather about analysing the data at the same time. We aim to get at the very core of the photo stories, including sounds, maybe fragrances and other occurrences that are present at the specific moment when a picture is taken (Edwards Citation2012). Secondly, we think that when there is a plenitude of photographs, the concept of punctum (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000) would work methodologically while we are ‘close reading’ the data. In a photograph, punctum is often a detail, a strong feeling that pierces the viewer. It resists the clear meanings and the cultural field of looking at pictures (this is what Barthes calls studium) (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000; see also Olin Citation2002). Thirdly, the idea of the decisive moment (Cartier-Bresson [Citation1952] Citation2014) makes it possible to describe the presence of events and join together the ‘past’, ‘present’ and ‘future’ in one moment. When using the decisive moment for analysing children’s photographs, images can be examined through the way children themselves and different events are present in the photos. Nevertheless, photography is never about the present; the act of looking occurs in the present and the time-specific characteristic of the photograph is implicit (Price and Wells Citation2015, 37). In a sense, as Skeggs (Citation2001, 429, 431) underlines, ethnography can be seen as one way in which theoretical deliberation is conducted within a context. Moreover, Skeggs emphasises how moving through different theoretical debates changes the analysis and makes possible a different understanding of the data. In our research, it is exactly this ‘different understanding’ where the chosen theoretical concepts invited us to explore.

Like so often in ethnographic research, various objects, affects, utterances, bodies and fragments relate in an ‘unholy mixture’ (Lecercle Citation2002, 53), rather than being wholly accessible to analysis. MacLure (Citation2013, 662) suggests approaching the analysing process as a spooling out without a predetermined destination. The spooling out adapts the idea of ‘becoming’, in which sense matters (Deleuze and Guattari Citation2011; Salo Citation2015). Sense is important, MacLure (Citation2014) elaborates, for its potential to trigger action in the face of the unknown. It can appear that the process flees the violence of ordinary, representational language; but, then again, it can open up the analysis in such a way that elements could be brought into motion and make them come alive also for the reader (Salo Citation2015).

In the article, the analysis started by spooling out the ‘five images browsed’ and searching for details and happenings in the images. Another starting point was to listen to the photo talks. Looking at the images on the computer screen while simultaneously listening to these photo talks gave us clues to the photographic processes. Following Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000, we think that when an image, a detail in it or something in the photo story strikes one or begins to disturb, it can be viewed as a part of a more extensive series of pictures. Major (Citation2012) claims that a single image gains its meaning especially when it becomes attached to other images.

Particularly where visual ethnographic research is concerned, a question can arise as to how an ethnographer and informants situate themselves in relation to the images, or how the informants create narratives with and around the images and the ethnographer (Pink Citation2007; see also Barley and Russell Citation2019). There are many affects and expectations that the photographer not only offers of the image to be looked at, but also of the story behind it (Drew and Guillemin Citation2014). The photograph, however, easily flees the reader’s attempts to grasp its meanings (Rose Citation2014; Rutherford Citation2019). Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the appearance of the images, the kind of information told about them, the motives of the viewer and the criteria whereby the images are chosen (Barker and Smith Citation2012), and finally, how those images are verbalised.

Aesthetic and cultural codes and one’s own experience mediate how we are capable of looking, reading, writing and producing the image (see Burgin Citation1986; Woolhouse Citation2019). In ethnography, writing cannot be separated from analysing, whereas writing as a method of research can generate a new kind of knowledge and can deepen an analysis (Salo Citation2007). The data are ‘partial, incomplete, and always in a process of retelling and remembering’ (Jackson and Mazzei Citation2013, 262). In this article, we have enclosed some images in order to prove the points we are making with the data as well as to illustrate the ambiguities we have faced while interpreting the data. We theorise with our photographic data and photo talks; what we see and how we see, ‘why one story is told and not another’ (Jackson and Mazzei Citation2013, 262), and how we write the words for the photographs taken by children.

Photo elicitation: stories behind the scenes

In this article, when a young photographer and a researcher are looking at images together, there is not only ‘you’ and ‘me’ but also ‘the two of us’, both are the audience and produce shared photo talks about images at the same time. ‘Talking pictures’, or more generally photo elicitation (Collier Citation1957), is explored here as a method of getting an idea of children’s photographs (Clark-IbáÑez Citation2004; Lapenta Citation2011). Most of all, photo elicitation is considered a collaborative process. In the data, when the participants themselves have taken the photos, they take the leading role in interpreting the images, and this creates a more equal relationship between the researcher and the participants (Lapenta Citation2011; Pauwels Citation2015; Pink Citation2007). The process permits shared understanding and thus it is essential for the analysing process.

School environments are universally rather dull places. Therefore, it would be obvious that, after receiving a camera, the children would photograph all kinds of things not so ordinary in the institutionalised environment. On the other hand, they were expressly asked to photograph their ordinary afternoons. In the analysis, the crucial thing would be to strive to see beyond the dull ordinariness to capture how children see the worlds around them.

The significance of events, things and places for children may escape the researcher’s attention, but some of these can be unpacked by photo talks. For example, Emma (After-school Group 1) had taken a photo () of the schoolyard through the window of the entrance hall. For the most part, the image consists of grey paving. Emma explains the photo:

That’s the spot where we are waiting to go out. There far away [in the schoolyard] we put some moss there once in the summer, in one, in such a hole, and it’s still there. Sometimes we skip around there. When we can go, like to play, then I hardly notice that we can go.

How to rupture the ordinary? How to take a closer look at it? Photo elicitation gives methodological ‘assistance’ as children’s photographs become further deepened and clarified through photo talks. It is obvious that children know what kind of pictures they took or how they framed their pictures. The personal significance of the photographs may also be unpredictable and produce unexpected information (Lapenta Citation2011). Some pictures may look very much alike and have the same spot in focus, and yet, photo talks with children reveal that they do not necessarily belong together as experiences and motifs, which may be quite different (see Barker and Smith Citation2012). Similarly, photographs of friends may include various meanings as Lauri narrated the four images that he took of Pete (After-school Group 3):

In the first picture, ‘Pete is waving his arms’. In the second one, ‘Pete is doing “the weird man”, I took the photo because Pete wanted me to’. In the third one, ‘Pete, from closer up. Pete looks – There’s lots of good in it’. For the fourth picture Lauri gives a name: ‘Pete, the football guy!’

By tradition, ethnography is informed by what is ‘writable’ and what is ‘readable’ (Atkinson Citation1992). In our case, the situation is somewhat more complicated. At its best, photo elicitation can permit the non-sayable to become the seeable (Riessman Citation2008) and make the invisible visible (Woolhouse Citation2019). Still, it is necessary to critically reflect on the whole process in which visual images are being deployed (Pauwels Citation2015; Piper and Frankham Citation2007; see also Richards Citation2011). The increasingly popular technique for eliciting young people’s ‘voice’ can have problems in the way it is sometimes employed, especially in relation to the interpretation and representation of children’s and young people’s visual ‘statements’ (Piper and Frankham Citation2007, 374). Further, childhood researchers are urged to attend children’s silences rather than merely their voiced utterances (Spyrou Citation2016). The photograph is not transparent and the ‘meaning does not lie in the photograph ready to be collected’ as Barker and Smith (Citation2012, 98; see also Richards Citation2011; Salo Citation2015) remind us. As we argue, the photo stories help writing with photos, but stories alone may not be sufficient to get the idea of an image (see Barker and Smith Citation2012; Eskelinen Citation2012). In order to seek deeper understanding of children’s perspectives on their own photographs, we need other theorisations beyond the photo elicitation method.

Punctum: withdrawing the usual blah-blah

Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000 uses a Latin word punctum for his purpose as an element that rises from the scene and shoots out of it like an arrow and pierces the spectator. Punctum is unforeseen and private, often a part object, a quiet, attractive or sharp affect in the photograph caused by a detail (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000; Kraus Citation2011). It is this very little something in the image that draws attention and stands out from the ordinary (Burgin Citation1986). Sometimes the detail fills up the whole image of the photograph and the viewers cannot take their eyes off it. Punctum produces an attraction or even adventure, a kind of ‘pressure of the unspeakable which wants to be spoken’, as Barthes ([Citation1981] Citation2000, 18–19; see also Fried Citation2005) puts it.

When spooling out the data, suddenly a girl without shoes appeared on the scene: She is carrying pink Converses in her hands and a friend of hers seem to be stunned by the occasion (). As they are outdoors, wearing only socks on their feet goes against the institutional practices. This is the way the notion of punctum (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000) becomes actual in the data. In the analysing process, a researcher becomes focused on the special detail that catches one’s attention and attracts one to it. In this particular picture, the detail raises some questions: What has happened? Why is the girl carrying her shoes in her hands?

Figure 2. A girl carrying shoes in her hands. (All sides of the image are cropped for the purpose of this article).

Punctum occurs ‘in the field of the photographed thing like a supplement that is at once inevitable and delightful’ (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000, 47). However, it is personal to a viewer and what the viewer adds to an image, as punctum, exists already in it (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000; Olin Citation2002). Barthes ([Citation1981] Citation2000, 47) claims that the photographer ‘could not not photograph the partial object at the same time as the total object’. Yet, punctum also has ‘a power of expansion’, which can be metonymic; in that case, in a way, the viewer complements the photo by thinking about its context (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000, 45). In the same way, the young photographer could not photograph the girl in the queue ‘separated’ from the other children or the Converses ‘separated’ from the hands of the girl. As to the context of , we can perceive a way of queuing, and the tidy environment of an elementary school.

Barthes ([Citation1981] Citation2000, 76) argues that reference is fundamental to photography, wherein the photographed things and events acknowledged to explore what was there, ‘which has been placed before the lens’ (see also Price and Wells Citation2015; Rutherford Citation2019). A photograph and the scene it portrays is – ‘a kind of natural being-there of objects’ (Olin Citation2002, 100), even though it is not informative of what the photographer perceived and thought while taking the picture. As in , the photographer said that she did not actually know what was happening there in the picture. This is something that punctum calls into play as even if punctum is seen by the viewer, it is not shown by the photographer to whom punctum principally does not exist (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000; Elkins Citation2011; Fried Citation2005). In the process of analysis, punctum produces a researcher’s viewpoint. Therefore, when children’s photographs are analysed, for a researcher there is the need to reflect the ethics of each image thoroughly; what the image brings out, whether each person has permission to be in the picture and whether the image can be published (see Woolhouse Citation2019). In order to bring forth punctum and still protect the privacy of the children, we decided to show a cropped and blurred version of the photo above ().

We are aware of the critique on the writings of Barthes and especially the critique of the use of punctum (see Derrida Citation2001; Elkins Citation2011; Olin Citation2002). Barthes ([Citation1981] Citation2000) ideas of photographic images are not regarded as theoretical enough, his concepts tend to change and the concept of punctum has often been misunderstood and too widely referenced as well. Punctum is a viewer’s notion that is ‘idiosyncratic, unpredictable or essentially incommunicable’ (Elkins Citation2011, 171). Consequently, theorising or attempting to describe the concept of punctum would be contrary to what Barthes potentially had in mind (Elkins Citation2011). Moreover, Barthes’ style of writing about punctum is laconic, what stands out as a focal point against the backdrop of details is the event in the picture (Burgin Citation1986). How can this kind of ambiguous concept be used, then, in order to interpret the photos taken by children?

Barthes himself discovered the nature of photography ‘starting from the place of no more than a few photographs’ (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000; Newton Citation2007, 3). In our article, a starting point was the ethnographic data of photographs and our methodological task was how to analyse children’s photographs, seize an image and solve the problem of analysis. Even though the photographic data are produced by children, for the researcher, the photographs are a kind of found materials. When you analyse a mass of photographs and find occurrences by pure coincidence, this offers an option for punctum and a close reading of the data. We argue that punctum can offer new approaches to the data, such as to realise the event in the picture or capture the ways by which children resist institutional practices. We found the concept of punctum quite inspiring, as it makes it possible to look at photographs in a different way, in detail and out of the ordinary, like ethnographers are used to doing, withdrawing the usual blah-blah, as Barthes ([Citation1981]Citation2000, 55) puts it.

Decisive moments of photographs: like hinges of happenings

The concept of the decisive moment is usually connected to Cartier-Bresson's photographs. Cartier-Bresson aimed at the right timing of the picture by framing it in advance and then waiting for something to happen. The decisive moment is a sort of ‘photographic kairos’ (Chéroux Citation[1952] 2014, 15), i.e. when things arrange themselves, at one precise moment, in an order that is both aesthetic and meaningful (Chéroux Citation2008, 96). The decisive moment can be characterised also as peripateia, which means the ‘course of action when all hangs in the balance’ – the ‘moment before’ something happens, or the ‘moment after’ something has just happened (Burgin Citation1986, 161). In the Aristotelian drama, peripeteia traditionally indicates a turning point, as there is no return after that (Aristoteles Citation1967).

The decisive moment resembles a kind of ‘hinge’, which articulates the moments ‘before’ and ‘after’ (Petäjä Citation2014). When theorising with the decisive moment, the photographs can be analysed in the ways the children were producing their photographs, how they themselves and various events are present. Some of the children aimed to take photos at a certain event or of a certain quality. Achieving a certain atmosphere in their photos was frequently the very idea of an image. In addition, the idea of something snatched up or stolen is always carried in the decisive moment (Warner Marien Citation2012). This was seen particularly in the photos where the children i.e. tried to achieve the very special shade of the colour in their pictures or how they waited for the special moment when the ball reached the basket.

The decisive moment can be seen particularly as a photographer’s intention. In digital photography, it is possible for the photographer to keep shooting until the desired point is captured. Still, the decisive moment does not occur in every photo, or even every time a photograph is taken. A photograph’s quality to freeze a rapid scene at a crucial moment may bring out something new, something previously unsuspected, into close scrutiny. Most often this happens when the object of a photo is unaware of being photographed (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000). Sometimes it happens that ‘[t]he picture-story involves a joint operation of the brain, the eye and the heart’ and thus ‘there is one unique picture whose compositions possesses such vigour and richness, and whose content so radiates from it that this single picture is a whole story in itself’ (Cartier-Bresson [Citation1952] Citation2014).

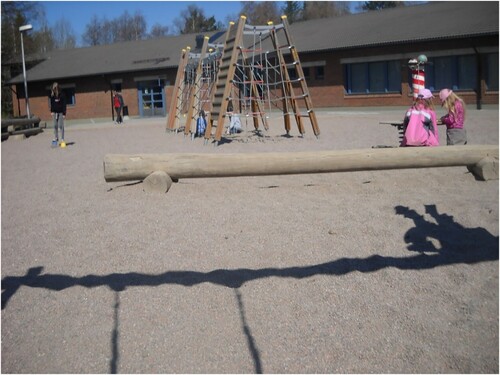

The image in is from the schoolyard where the children who participate in after-school activities spend their time. In the centre of the photo, there is a log on which to sit or walk and behind it, there is a jungle gym and two other play structures. The background of the photo shows the school building and the foreground the shadow of a swing. On the sandy ground under the jungle gym, there are two children playing. In the right corner of the photo, two children are examining something, which cannot be discerned in the photo. In the left corner, a child is walking on top of pair of plastic cups. The supervisor is moving away from the school building. No one in the photograph is looking at the camera.

The image could easily be entitled ‘an overview of after-school activities’. However, the photographer Thea (After-school Group 3) said she had taken the photo while swinging. When she was asked ‘you’re swinging at the same time?’ – ‘Yep’, she said. ‘ … and taking the photo?’ – ‘Yep’, she said again. Thea emphasises the simultaneousness of the swinging and the taking of the photo. The foreground space of the image, at first sight seemingly empty, becomes meaningful through the concept of the decisive moment. The shadow of the swing provides a hint at how the photographer is present in the photo, even though the proper action (swinging, photographing and being in the photo) is situated outside of the image. Thea’s whole sphere of life at that moment is presented in the image – which is as much outside her as inside her (see Cartier-Bresson [Citation1952] Citation2014).

Thea is observing the world from a particular angle, from that of the swing. It is possible to read the image as a physical and internalised activity, as a perspective suggested in non-representational theory (Thrift Citation2008) and not merely as a representation of time (Lundström Citation2012; Sutton Citation2010). The idea of photography as a non-representative practice (Thrift Citation2008) is attractive in relation to the concept of the decisive moment. Consequently, it allows one to examine the innermost aspects of the process of photographing (Lundström Citation2012). Thrift (Citation2008) sees photography as a waiting game while producing space and time, in which it is possible to catch the object. Cartier-Bresson’s ([Citation1952] Citation2014) idea of the decisive moment, the temporal ‘hinge’ of the events in the photo, can be compared with the relation between the photograph and time (Sutton Citation2010). Yet, something in the shadow of the swing does not cease to disturb.

Breaking down the frames: the girl keeps on swinging

In our ethnography, we were tracking down the children’s ordinary afternoons in their after-school activities – things that happen in their everyday life. In order to get a grip on the ordinariness, we asked the children to photograph their doings, feelings and happenings. As a result, we acquired rich data, the plenitude of photographs, though many of them seemed to be quite mysterious and puzzling for our ethnographic gaze. As anticipated, children’s photographs convey valuable insights into their worlds, their cultures, thoughts, experiences and meaning making. Generally speaking, the photographs proved to be ethnographic data of vital importance, and we argue that while doing ethnographic research, not to mention when children are not able to write, photography is irreplaceable, even though there are many ambiguities that follow their analysis as we have discussed in this article.

Where did children’s photographs take us? To begin with, a photograph can only show a framed part of the world around us, in the way that we have learned to read photographs in our culture (Burgin Citation1986; Lintunen Citation2013). Even the smallest details, however, may function so as to allow interpretations to flow freely while reading images (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000; Major Citation2012). Some images of our ethnographic data were incredibly touching, some even slightly repulsive or then similar to each other ad nauseam. At times, a picture caused ‘an urge’ to see the events outside of the frame of the picture. Although our article addresses single images it simultaneously reaches towards an analysis of the plenitude of photographs as the stories continue in other photographs of the data. As to the photographs taken by children, their analysis can be perceived as being fluid; this is so in the sense that we cannot be certain whether their original intention was the one described afterwards. This is the methodological dilemma that remains, ‘the photograph is indescribable: words cannot substitute for the weight or impact of the resemblance of the image’ (Price and Wells Citation2015, 37). However, the visual data analysed together with the photo talks and researchers’ observations made the analysis deeper in our ethnographic setting. Further, the chosen theoretical concepts brought added analytical value while the concepts invited us to explore further.

Initially, we were inspired by the idea of ‘theorising with data’ and we were keen on seeing how it works in our analytical process and what it produces. As to analytical value for further ethnographic research with and on children, the article certainly works as an example about doing ethnographic analysis while theorising with data. As we have shown, the chosen concepts worked very well in our research setting, whereas following Skeggs (Citation2001, 429, 431) different data need different understanding, different theoretical concepts and different theoretical discussions.

In the article, we have explored how to analyse and verbalise photographs and how to write about photographs taken by children while we have displayed some images and theorised with them. Epistemologically speaking, the idea of ‘theorising with’ produced subtle nuances that came into view while we, as researchers, started to grasp the situation better. In a sense, this meant the ‘different understanding’ (Skeggs Citation2001) and the ‘newness’ (Jackson and Mazzei Citation2012, viii) that contributes to further ethnographic research, as we expect.

The data was used as stopping points and the specific concepts were arrested on purpose, in order that they would help us to extend the analysis. The photo elicitation method, the concept of punctum and the concept of the decisive moment brought up new ways of thinking with the data. Photo elicitation was a sort of process in which children and researcher together produced a shared view, while talking with the photos. Punctum started to prick, bruise and burn (Barthes [Citation1981] Citation2000, 27) us, or more generally, it made it possible to keep on eye the very details of the data. The decisive moment in our article refers to the researcher’s interpretation of an idea as to how a thing or an event in a photograph taken by the child is present in the right place at the right time in the image. Actually, the photographs turned out to be more than ordinary, rather extraordinary and in a word, unordinary, as they showed the creative power children have while creating and developing their leisure activities, yet in an organised setting.

As to children’s after-school activities in institutional settings, our ethnography brings out the friction between the discourse of organised learning and education and the formal objectives that are set in accordance with them. Our ethnographic analysis sees efficiency, children’s individual competence and social capital in a different light. Against the logic of efficiency, children seem to have competencies in making their everyday activities more creative, spontaneous and meaningful than the formal objectives of organised learning and education propose. In terms of the celebrated economic growth, efficiency and competitiveness the creative resources might be of great value.

Ethnography is traditionally informed by what is both ‘writable’ and ‘readable’ (Atkinson Citation1992). Our methodological challenge stretched somewhat further as our ethnography is informed also by what is ‘non-sayable’ but ‘seeable’ and ‘invisible’ but ‘visible’. With the help of the photographs taken by children as well as the photo talks and the photo stories based on the photographs, we could bring up the subject. The photographs played a significant role in our ethnography.

Then again, while participating in the research, while kicking around and discovering their familiar surroundings anew, maybe the children started to know better what they are doing, to see their immediate surroundings differently and more expressively – to see them as if on a television screen. This is how the children played with the cameras focusing on the faces of their friends, or making their toys perform as if they were living beings, full of drama and excitement. The state of play draws parallels with Bourdieu’s (Citation1990, 69) notion that people may not completely know what they are doing and this is why social analysis is needed, because this way their doings make perhaps more sense than they realise.

Certainly, if the research was conducted today, there would be various photo-taking devices available. Reflecting on the meaning of this development goes beyond the scope of our research, whereas the novelty appeal of the digital cameras was advantageous to the research, not least because of the exploratory nature of our ethnography.

Rutherford (Citation2019, 37) suggests that we should ‘re-imagine’ the practice of photography ‘as an active – or as an act of – collaboration between medium and practitioner’ because scenes, events and ‘moments’ in photographs are not only taken but created by the act of photographing them. In the children’s photographs, while children are creating scenes, events and moments they are not only ‘re-imagining’ but also ‘re-organising’ their supervised space.

In this article, the photograph was seen as a frame for events, which begin, exist and continue outside the photograph and the moment of taking the photo. The photograph itself is permanent of the moment when it was taken; at the same time, however, it continues to live in time (Lintunen Citation2013). This is how the girl keeps on swinging, keeps on swinging.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to the participating children and to the staff of after-school activities who made this research possible. We also express our sincere thanks to two anonymous reviewers who made helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Almqvist, A.-L., and L. Almqvist. 2015. “Making Oneself Heard: Children's Experiences of Empowerment in Swedish Preschools.” Early Child Development and Care 185 (4): 578–593. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.940931.

- Aristoteles. 1967. Runousoppi [Poetics]. Translated by P. Saarikoski. Helsinki: Otava.

- Atkinson, P. 1992. Understanding Ethnographic Texts. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barker, J., and F. Smith. 2012. “What’s in Focus? A Critical Discussion of Photography, Children and Young People.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 15 (2): 91–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.649406.

- Barley, R., and L. Russell. 2019. “Participatory Visual Methods: Exploring Young People’s Identities, Hopes and Feelings.” Ethnography and Education 14 (2): 223–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2018.1441041.

- Barthes, R. [1981] 2000. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by R. Howard. Reprint. London: Vintage Books.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Translated by R. Nice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourke, J. 2017. “Children’s Experiences of Their Everyday Walks Through a Complex Urban Landscape of Belonging.” Children's Geographies 15 (1): 93–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2016.1192582.

- Burgin, V. 1986. “Diderot, Barthes, Vertigo.” In Situational Aesthetics: Selected Writings by Victor Burgin, edited by A. Streitberger, 159–182. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Burke, C. 2008. “‘Play in Focus’: Children’s Visual Voice in Participative Research.” In Doing Visual Research with Children and Young People, edited by P. Thomson, 23–36. London: Routledge.

- Cartier-Bresson, H. [1952] 2014. The Decisive Moment: Photography by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Translated by F. Destribats. Reprint. Paris: Verve, Simon and Schuster.

- Chéroux, C. 2008. Henri Cartier-Bresson. Translated by D.H. Wilson. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Chéroux, C. [1952] 2014. A Bible for Photographers. The Decisive Moment: Photography by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Translated by F. Destribats. Reprint. Paris: Verve, Simon and Schuster.

- Clark-IbáÑez, M. 2004. “Framing the Social World with Photo-Elicitation Interviews.” American Behavioural Scientist 47 (12): 1507–1527. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764204266236.

- Collier, J. Jr. 1957. “Photography in Anthropology: A Report on Two Experiments.” American Anthropologist 59 (5): 843–859. http://www.jstor.org/stable/665849.

- Cooper, V. L. 2017. “Lost in Translation: Exploring Childhood Identity Using Photo-Elicitation.” Children's Geographies 15 (6): 625–637. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2017.1284306.

- Delahaye, L. 1999. L’Autre. London: Phaidon.

- Deleuze, G. 2004. The Logic of Sense. London: Continuum.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 2011. A Thousand Plateaus. London: Continuum.

- Dennis, B., and C. Huf. 2020. “Ethnographic Research in Childhood Institutions: Participations and Entanglements.” Ethnography and Education 15 (4): 445–461. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2020.1722951.

- Derrida, J. 2001. “The Deaths of Roland Barthes.” In The Work of Mourning, edited by P. A. Brault and M. Naas, 31–67. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Drew, S., and M. Guillemin. 2014. “From Photographs to Findings: Visual Meaning-Making and Interpretive Engagement in the Analysis of Participant-Generated Images.” Visual Studies 29 (1): 54–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2014.862994.

- Edwards, E. 2012. “Objects of Affect: Photography Beyond the Image.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (1): 221–234. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23270708.

- Elkins, J. 2011. “What Do We Want Photography to Be: A Response to Michael Fried.” In Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, edited by G. Batchen, 171–185. Cambridge, MA: The MIT press.

- Eskelinen, K. 2012. “Iltapäivätoiminnan osallistumisen tilat ja puhuvat kuvat [Participation in After-School Activities: The Voice of Images].” The Finnish Journal of Youth Research. Nuorisotutkimus 30 (1): 20–34.

- Fischman, G. 2001. “Reflections About Images, Visual Culture, and Educational Research.” Educational Researcher 30 (8): 28–33.

- Fried, M. 2005. “Barthes’s Punctum.” Critical Inquiry 31 (3): 539–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/430984.

- Jackson, A., and L. Mazzei. 2012. Thinking with Theory in Qualitative Research: Viewing Data Across Multiple Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Jackson, A. Y., and L. A. Mazzei. 2013. “Plugging One Text Into Another: Thinking with Theory in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 19 (4): 261–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800412471510.

- James, A., C. Jenks, and A. Prout. 1998. Theorising Childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Kraus, R. E. 2011. “Notes on the Punctum.” In Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, edited by G. Batchen, 187–192. Cambridge, MA: The MIT press.

- Kullman, K. 2012. “Experiments with Moving Children and Digital Cameras.” Children’s Geographies 10 (1): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2011.638174.

- Lapenta, F. 2011. “Some Theoretical and Methodological Views on Photo-Elicitation.” In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by E. Margolis and L. Pauwels, 201–213. London: SAGE.

- Lecercle, J.-J. 2002. Deleuze and Language. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Lehto, S., and K. Eskelinen. 2020. “‘Playing Makes It Fun’ in Out-of-School Activities: Children’s Organised Leisure.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 27 (4): 545–561. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568220923142.

- Lintunen, M. 2013. “Silmä on aivojen jatke, kamera silmän [The Eye Is an Extension of the Brain, the Camera That of the Eye].” In Maailma, jossa olen: Kaisaniemen ala-asteen katseita, edited by T. Lehtoranta and M. Lintunen, 13–19. Espoo: Prometheus kustannus.

- Lundström, J.-E. 2012. “Valokuvallinen tieto [Knowing Photographs].” In Valokuvallisia todellisuuksia. Translated by S. Kokkola, edited by J.-E. Lundström, 9–36. Helsinki: Like.

- Luttrell, W. 2010. “‘A Camera Is a Big Responsibility’: A Lens for Analysing Children's Visual Voices.” Visual Studies 25 (3): 224–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2010.523274.

- MacLure, M. 2013. “Researching Without Representation? Language and Materiality in Post-Qualitative Methodology.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (6): 658–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788755.

- MacLure, M. 2014. “Classification or Wonder? Coding as an Analytic Practice in Qualitative Research.” In Deleuze and Research Methodologies, edited by R. Coleman and J. Ringrose, 164–183. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Major, E. J. 2012. “Valokuva todenkaltaisuuden otteessa [Photography Lost to Resemblance].” In Valokuvallisia todellisuuksia. Translated by S. Kokkola, edited by J.-E. Lundström, 113–131. Helsinki: Like.

- McLaughlin, J., and E. Coleman-Fountain. 2019. “Visual Methods and Voice in Disabled Childhoods Research: Troubling Narrative Authenticity.” Qualitative Research 19 (4): 363–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794118760705.

- Newton, R. 2007. “Photography, Dance, and the Concept of Punctum.” (Thesis). Edith Cowan University.

- Olin, M. 2002. “Touching Photographs: Roland Barthes’s ‘Mistaken’ Identification.” Representations 80 (1): 99–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2002.80.1.99.

- Pauwels, L. 2015. “‘Participatory’ Visual Research Revisited: A Critical-Constructive Assessment of Epistemological, Methodological and Social Activist Tenets.” Ethnography 16 (1): 95–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138113505023.

- Pedersen, H., and B. Pini. 2017. “Educational Epistemologies and Methods in a More-Than-Human World.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 49 (11): 1051–1054. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1199925.

- Petäjä, J. 2014. “Valokuvaaja jaksoi odottaa ratkaisevaa hetkeä [The Photographer Had the Patience to Wait for the Decisive Moment].” Helsingin Sanomat, December 14. https://www.hs.fi/kulttuuri/art-2000002785295.html

- Pink, S. 2007. Doing Visual Ethnography. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Piper, H., and J. Frankham. 2007. “Seeing Voices and Hearing Pictures: Image as Discourse and the Framing of Image-Based Research.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 28 (3): 373–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01596300701458954.

- Price, D., and L. Wells. 2015. “Thinking About Photography: Debates, Historically and Now.” In Photography: A Critical Introduction. 5th ed., edited by L. Wells, 9–74. London: Routledge.

- Richards, C. 2011. “In the Thick of It: Interpreting Children's Play.” Ethnography and Education 6 (3): 309–324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2011.6105822011.

- Riessman, C. K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Rose, G. 2014. “On the Relation Between ‘Visual Research Methods’ and Contemporary Visual Culture.” The Sociological Review 62 (1): 24–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12109.

- Rutherford. 2019. “Is This Photograph Taken? The Active (Act of) Collaboration with Photography.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 18 (1): 37–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2018.1488927.

- Salo, U.-M. 2007. “Etnografinen kirjoittaminen [Ethnographic Writing].” In Etnografia metodologiana: Lähtökohtana koulutuksen tutkimus, edited by S. Lappalainen, P. Hynninen, T. Kankkunen, E. Lahelma, and T. Tolonen, 227–246. Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Salo, U.-M. 2015. “Simsalabim, sisällönanalyysi ja koodaamisen haasteet [Abracadabra, Content Analysis and Challenges of Coding].” In Umpikujasta oivallukseen. Refleksiivisyys empiirisessä tutkimuksessa, edited by S. Aaltonen and R. Högbacka, 166–190. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

- Skeggs, B. 2001. “Feminist Ethnography.” In Handbook of Ethnography, edited by P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, J. Lofland, and L. Lofland, 426–442. London: Sage.

- Spyrou, S. 2016. “Researching Children’s Silences: Exploring the Fullness of Voice in Childhood Research.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 23 (1): 7–21.

- Stewart, K. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Strandell, H. 2013. “After-School Care as Investment in Human Capital: From Policy to Practices.” Children & Society 27 (4): 270–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12035.

- Sutton, D. 2010. “Delay: Notes on Photography as Non-Representational Thinking.” In PHotoEspaña 2010 Catalogue: Time Expanded, edited by S. Mah, E. Cavada, U. Baer, M.A. Doanne, L. Mulvey, R. Bellour, D. Sutton, et al., 145–151. Madrid: La Fábrica.

- TENK. 2019. “Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK Guidelines 2019.” The Ethical Principles of Research with Human Participants and Ethical Review in the Human Sciences in Finland.

- Thorne, B. 1994. Gender Play: Girls and Boys in School. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Thrift, N. 2008. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. Oxford: Routledge.

- Torre, D., and J. Murphy. 2015. “A Different Lens: Changing Perspectives Using Photo Elicitation Interviews.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 23 (111): 1–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v23.2051.

- Varvantakis, C., S.-M. Nolas, and V. Aruldoss. 2019. “Photography, Politics and Childhood: Exploring Children’s Multimodal Relations with the Public Sphere.” Visual Studies 34 (3): 266–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2019.1691049.

- Warner Marien, M. 2012. 100 Ideas That Changed Photography. Idea no 63, The Decisive Moment. London: Laurence King.

- Woolhouse, C. 2019. “Conducting Photo Methodologies with Children: Framing Ethical Concerns Relating to Representation, Voice and Data Analysis When Exploring Educational Inclusion with Children.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 42 (1): 3–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2017.1369511.

- Änggård, E. 2015. “Digital Cameras: Agents in Research with Children.” Children's Geographies 13 (1): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.827871.