ABSTRACT

The paper reports on a study that explored selected lecturers’ perspectives and discourses on a university's Student Evaluation of Teaching (SET) policy in South Africa; particularly what the policy prioritised in terms of purpose and evaluation processes. It also reports on the lecturers’ reflections on the additional questions they included in the self-designed evaluation tools. A questionnaire, informal group conversations, and extended observations were used to collect data, and Latour (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford University Press and Latour (2013). An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence. Translated by C. Porter. London: Harvard University Press works helped make sense of the lecturers’ perspectives and discourses. Findings indicate a partial grasp of what the SET policy promotes. Lecturers’ understanding seemed to emphasise teaching evaluations’ professional development and accountability functions. Little attention was paid to the context in which teaching and learning occurred. The conclusion suggests ways in which the guidance given to lecturers could be improved to help them understand and work more effectively with their university’s SET policy.

Introduction

Teaching and course evaluations in higher education are used primarily to monitor teaching effectiveness (Blackmore Citation2009), promote the accountability of those who teach and justify decisions on how to reward lecturers at different stages of their careers (Kember, Leung, and Kwan Citation2002), for example, confirming a permanent appointment in the case of probation or justifying a promotion. In some institutions, when processing students’ responses for evaluation reports, each question is scored on a scale of 1–5 and individual lecturer’s performance is compared with the performance of other lecturers across the department/school, faculty and institution. Afterwards, an average percentage score determines the quality of an individual’s teaching effort. It is generally assumed that a lecturer is doing well if the score is above the university average or on par but not below. In addition, there is an expectation that teaching evaluation through peer reviews of lectures will be conducted to corroborate the student feedback (Patton Citation1990). However, often SET is prioritised because of the possibility of quantifying the feedback, which makes it easier to use based on ratings.

This paper reports on a study that investigated how lecturers in a South African university interpreted the purpose, linked different aspects of their SET policy and engaged with it in practice. To clarify the context in which their perspectives and discourses were obtained and had to be made sense of, the paper first discusses the policy, then follows a brief account of the theory used to make sense of the data collected, a discussion of how the study was designed, the presentation of the findings and their discussion.

The SET policy in university X

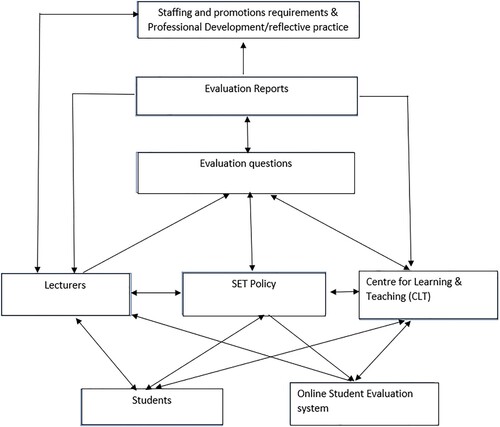

The SET policy in University X connects teaching evaluations to lecturers’ professional development, accountability for teaching effectiveness, and academic appointments. General standard questions (core items) that mainly focus on the teaching process are set by the university and compulsory for all evaluations to facilitate comparability. The questions are provided as survey statements on teaching effectiveness that students have to agree or disagree with. Albeit, to ensure evaluations that also focus on teaching in relation to what is conceptually fundamental to the different disciplines, the policy encourages lecturers to have a voice and a stake in SET through an opportunity to either choose relevant questions from an item bank or develop new ones (Brewington and Hall Citation2018).

Lecturers are not compelled to participate in SET. They participate as and when they need to. The Centre for Learning and Teaching (CLT) coordinates quarterly teaching and course evaluation cycles (which include organising the SET online system and students’ completion of forms, supporting lecturers’ declaration of interest to conduct evaluations and selection of additional questions, preparing and making the reports available for use by different stakeholders within the university). After the evaluation process, the lecturers engage with the feedback in the reports to reflect on teaching and make submissions to line managers to account for their performance and to committees responsible for promotions.

indicates all aspects the SET policy proposes as important when teaching is evaluated and how they should relate.

Studies on SET, amongst others, Steyn, Davies, and Sambo (Citation2019), Saunders, Charlier, and Bonamy (Citation2005), and Shulha (Citation2000) emphasise the relevance of teaching evaluations to students and teaching contexts. The authors criticise evaluations that promote the accountability agenda based on rating performance at the expense of lecturers’ knowledge and expertise, students, and the teaching and learning context (see also Saunders Citation2012). No studies that specifically looked at how these aspects were collectively considered in designing and carrying out teaching evaluations could be traced. Therefore, in conducting the study, the researchers investigated how lecturers, as organisational actors in a higher education institution (Yanow Citation2009), understood the purpose and evaluation processes that were promoted by the SET policy as part of the ‘everyday-ness’ (Ybema and Kamsteeg Citation2009) of their work. They (researchers) wished to answer the following question: ‘How do the lecturers’ perspectives (views) and discourses (thinking and speaking) reflect an understanding of the purpose and evaluation practices that are prioritised in the SET policy?’

Exploring their perspectives and discourses as dimensions of meaning-making (Ybema and Kamsteeg Citation2009, 6–7) had to expose taken-for-granted and often uncritical stances that needed to be addressed to make professional development activities meaningful.

Latour (Citation2005) argued that social activities should be best understood as a plurality of human and non-human aspects (people and things) that are seamlessly connected. For every activity to function effectively, the human and non-human aspects it incorporates need to be understood as connected/a network. This work, together with its extension, Latour's (Citation2013) An Inquiry into Modes of Existence (AIME), was useful to examine and explain how lecturers understood human and non-human aspects (for example, biographies, effective teaching, the context of teaching and learning on courses and student success and how SET was linked to professional accountability and development) identified as crucial in their university’s SET policy, as collectively constituting the teaching evaluation process. However, Latour’s views were not applied exclusively nor utilised fully to explain the lecturers’ understanding of their institution’s SET policy. Specifically, as researchers and teacher development practitioners, we were interested in how lecturers referred to and related aspects that needed to be linked when designing tools and conducting teaching evaluations.

Theoretical framework – Latour on ANT and AIME

Latour (Citation2005) employs Actor-network theory (ANT) to explain how social activities or projects are accomplished through people and things co-acting across ‘geographical, institutional, or temporal boundaries’ (Tummons Citation2021, 3). He argues that, when studying social activities/projects, philosophical rigour is only possible by exploring the relationship between human and non-human elements, particularly how these elements are referred to and related. Failure to focus on these aspects is likely to result in category mistakes that point out qualities that social projects ‘ … could not possibly possess’ (Latour Citation2005, 3). In Latour (Citation2013), he extends ANT with AIME and explains, amongst others, four qualities that distinguish social activities/projects as modes of existence. The first refers to the being of social projects, human and non-human that constitute them and the course of action being followed, that is, the logic, movement or path followed in structuring them as social phenomenon. To identify hiatuses (breaks) in such a course of action, it is important to look at how human and non-human aspects are/were brought together through co-acting across institutional or temporal boundaries. The second quality is about truths and untruths in a course of action and has to do with what Latour calls the felicity and infelicity conditions in the mode of existence. The third is the principle of symmetry or the interconnectedness of the various features in a social project/activity, and the last is the otherness or alterity that distinguishes modes of existence [how one mode is distinguished from another] (see Latour Citation2013; 488–489 in Tummons Citation2021). Based on this argument, Latour proposes that AIME be used as a research approach to avoid the narrow and restrictive interpretations based on what he refers to as ‘moderns and their peregrinations’ (Latour Citation2013, 22).

Viewing social activities/projects as modes of existence, that is, ontological features of the world, brought into view – [not constructed] – by empirical inquiry, derived from experience, and therefore capable of being added to [see Tummons Citation2021] makes them have unique forms of truth and falsehood that researchers should strive to clarify. This pluralistic approach, ‘in which a course of action has to be grasped, the direction in which one should plunge’ (Latour Citation2013, 52) in research, helps to avoid a false dichotomy between human and non-human aspects when studying social projects. In short, AIME promotes a multidimensionality that significantly affects how truth is arrived at. With it, research is not solely epistemological but ontological and philosophically rigorous in focusing on how people and things are co-actants within social activities/projects.

Kincheloe (Citation2006) also criticised social inquiries that are detached from socio-historical contexts that constitute and constrain knowledge production by overlooking the impact of such contexts. Separating humans from their non-human surroundings and failing to discern the unique ways context shapes social projects undermine the organic interconnection of humans and their surroundings. In the place of such inquiry, Kincheloe (Citation2006, 183) suggests using critical ontology as an inquiry that connects humans in numerous ways to a living social and physical web of reality on various levels. This study is therefore designed to establish whether lecturers understood the complexity of relations that had to be considered in translating the SET policy into evaluation tools and processes.

The study

Context

The university in which the study was conducted is a public institution and one of the best internationally ranked within South Africa. Its almost 40,000 students and over a thousand academics are unequally distributed across the faculties. Most students and staff are in the Social Sciences and Humanities degrees.

Sampling

Forty-five lecturers affiliated with 4 faculties were invited to participate in the study after they had attended workshops on teaching evaluations run by the CLT. The lecturers were responsible for either a full-year university course or part of a course they evaluated at the end. A total of 25 lecturers with diverse teaching backgrounds agreed to participate, but only 17 proceeded, 5 of whom offered full-year courses and 12 semester courses in the faculties. The lecturers who decided not to participate were worried about increasing their workload and impacting other responsibilities, such as research. provides more details about the participants. While the sample size appears limited, this aligns with ethnographic sampling (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2011) and facilitated an in-depth exploration of the lecturers’ views.

Table 1. Representation of participants across the faculties.

Fieldwork

The study was conducted between July 2018 and October 2020. The university context was a natural environment that allowed adequate immersion (Jeffrey and Troman Citation2004) in a higher education organisation (Yanow Citation2009) because one of the researchers worked in a unit for academic staff development and could collect data without specific preparations for actual on-site presence. Part of her responsibilities and key performance areas included monitoring and studying (researching) SET. However, she had to follow proper research processes. She set up an independent study and formally requested permission from lecturers who agreed to participate by completing consent forms. Ethical clearance was also applied for in the university and obtained as ‘ethics protocol H16/11/44’. As put by, for example, Ybema and Kamsteeg (Citation2009) (cited in Jayathilaka Citation2021, 97), ‘when doing fieldwork in situations or settings that are or have become strongly familiar to us, strangeness is not a given but an achievement.’ The other author had an insider/outsider's status in the study as a former academic in the institution which provided greater reflection and impartiality in interpretation. Both authors were involved in the management and analysis of the data and writing of the paper.

The research process

We believed that as organisational actors in a higher education institution (Yanow Citation2009), the lecturers would to some extent draw on taken for granted ‘interpretive models of and prescriptive models for reality’ (Ybema and Kamsteeg Citation2009, 8) adopted and developed within the university when thinking, speaking and implementing the SET policy directed activities, and adopted organisational ethnography (Cunliffe Citation2010: Ybema and Kamsteeg Citation2009) as a methodology to study their perspectives and discourses. As put by Jayathilaka (Citation2021, 95):

… the interplay between data and theory and between the researcher and the researched can be rich sources of inspiration which are clearly incorporated in organizational ethnography. … Seeing the extraordinary-in-the-ordinary may help to elicit curiosity about people ‘strangeness’, as well as challenge the taken-for-granted logic of things, both the participants’ and the researchers.

Administering questionnaires were followed in the first quarter evaluation cycle (March–May 2019) by studying the additional questions lecturers had included in their self-designed SET tools to encourage students to reflect on priority aspects in their courses. Two informal monthly group meetings with the researcher on-site were also arranged to discuss the questions set and notes prepared by both authors as preliminary analysis of the lecturers’ questionnaire responses. The conversations gave the lecturers a chance to learn from each other’s tools. Many (n = 15 of 17) had not discussed their SET reports with anyone else before, except for line managers, when required. Handwritten notes and recordings were made to ensure that both authors were aware of levels of participation across the faculties involved in the study and had access to the different lecturers’ voices.

In the second semester, during the initial phase (July–September 2019), observations were conducted by the researcher to capture how the lecturers conducted teaching evaluations, including how they encouraged and guided students when completing the evaluation forms. Guided by, amongst others, Ybema and Kamsteeg (Citation2009) and Chiseri-Strater (Citation1996), to approach this role with an open mind, the researcher consciously acted as a non-participant observer and maintained a critical distance from her unit's activities that focused on SET by not attempting to influence processes during this phase. The evaluation processes were observed, and field notes describing the actions witnessed were written for both authors because one author was not involved in this process. From mid-October 2019 to March 2020, the researcher on-site conducted the second phase of informal group conversations by discussing her observation notes with individual lecturers. The conversations were once again recorded for sharing. presents the different phases of collecting data.

Table 2. Different phases of the data collection process.

Data management

Data analysis was ‘iterative’ (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2011, 186); it occurred during data collection, moving backwards and forwards between the phases. For example, firstly, guided by Moyo (Citation2016, 97) we used textual analysis as informed by discourse analysis (Fairclough Citation2003) to analyse the questionnaire responses (as the first voice of the lecturers) and singled out keywords and the main ideas that pointed to an understanding of the purpose of the SET policy and how lecturers were guided to implement it.

As Tobin and Davidson (Citation1990) explain, in the data collection process ‘each textual layer (part of the process) reacts to earlier texts without entirely replacing, subsuming, or negating them’ (274). The responses in the questionnaires were carefully read, notes made and reflected upon to identify common core issues that were emphasised. During this, it became clear from statements such as ‘ … identify areas … that need improvement’ and ‘ … performance appraisal’; that the majority of the lecturers (n = 14 of 17) conducted evaluations to ‘review’ teaching and identify aspects that needed improving. The other equally highlighted aspect referred to the effectiveness of teaching practices, for example, ‘establish … teaching practices are effective … .’ and ‘ … students’ responses … a helpful guide to … different needs'. Teaching effectiveness was also linked to performance appraisals and career advancement; for example, ‘important for the end-of-year performance’; ‘satisfy university requirements regarding probation, promotion, etc.’ The statements made were each taken to constitute a unit of meaning, and through textual analysis, we attached a code to each unit (Moyo Citation2016, 98) and then inferred from the phrases in which the words appeared a reason for conducting SET. For example, phrases such as ‘having to design the tools makes me think harder about how effective my teaching should be in “delivering” course material … , and ‘SET makes me think of my teaching and course, … what to continue doing and how to deal with hinted dissatisfactions about my performance’ both described and reflected (Polkinghorne Citation1995) an understanding of the purpose of SET. We could then infer from them that the lecturers held a view of SET as developmental. Similarly, the phrase, ‘evaluations can be quite informative on what you do well and what you may need to address going forward’ meant that the lecturers viewed SET as important for improvement and professional development (bold added for emphasis). Overall, the excerpts from the lecturers’ responses align with the policy intent.

The data collected between March 2019 and March 2020 created the second voice, starting with the observations of the teaching evaluation processes, including group discussions of the self-designed SET tools and the conversations of the observation notes with each lecturer. It (second voice) complemented the first data set collected as questionnaire responses.

The explanations of how the self-designed tools were used in the evaluation processes observed by the researcher on site helped to deepen understanding of the lecturers’ perspectives and discourses, as illustrated in the findings of the study. Data from the observations and notes on the post-observation individual informal conversations with the researcher on site were examined, looking for references [REFs] and relations [RELs] between what was witnessed and how it was spoken about. The codes developed from the two data sets were linked to categorise perspectives and discourses; and afterwards used to create themes used to present findings. As Button (Citation2000) explains ‘we need to be more rigorous, demanding not merely scenic depictions of settings and doings, but analytic explications of how activities are done and ordered’ (330). Citing Ybema and Kamsteeg (Citation2009), Jayathilaka (Citation2021) also emphasises the importance of such analysis as follows:

Context-sensitive and actor-centered analysis is another salient feature of organizational ethnography which is about combining an orientation toward subjective experience and individual agency in everyday life with sensitivity to the broader social settings and the historical and institutional dynamics in which these emerge or are embedded. (94).

To validate the research, amongst others, the four trustworthiness components, namely, credibility, dependability, transferability and confirmability (Kivunja and Kuyini Citation2017; Lincoln and Guba Citation1985), were used as criteria.

In the next section, we present the findings, starting with the first data set (questionnaire responses) and views on the self-designed tools, then an example of how the tools were used in practice and finally, reflections on how lecturers experienced the SET.

Findings

Explaining the purpose of the SET (interconnectedness of the various aspects and their distinctiveness)

In explaining the purpose of SET, lecturers’ questionnaire responses highlighted the instrumental value of the practice, particularly, the importance of the questions they were allowed to add to what the university provided. They emphasised that both were primarily used for their own and students’ development.

it is used for continuous improvement; to reflect on my course design and identify the strengths and weaknesses of the Capstone course. Having to design the tools makes me think harder about how effective my teaching should be in ‘delivering’ course material or content. Over the years, students’ responses have been a helpful guide. Each cohort appears to have different needs based on how the material is received. I have to particularly think about this when designing SET tools and find out how stimulating my courses and teaching are.

… SET makes me think of my teaching and course material; identify areas that need improvement … establish if they are effective in supporting student learning. It’s good to evaluate my teaching skills. Feedback that is positive or negative is helpful for thinking about what to continue doing and how to deal with hinted dissatisfactions about my performance.

SET helps to identify areas of my teaching that need further investigation and improvement. Evaluations can be informative on what you do well and what you may need to address going forward. I get to ‘peep’ into the minds of the students and am able to see things from their perspective, reinforce the good, and think of how to address concerns without compromising my discipline.

I’m not altogether sure what is expected of me, although I was told at my induction that I needed to get evaluations. I found out more at the Teaching workshop in March about the value of evaluations for teaching and career progression.

I didn’t know such a policy existed. I am doing my first evaluation this semester since starting at the university. So, I will go find this policy. I relied on my knowledge about evaluations that I gained while teaching at another university.

The Head of School because he appraises me to help me develop interest in quality teaching and learning. So does another colleague because he is equally passionate about teaching and learning.

I had to submit to my HoD for probation purposes and asked him for advice on how to interpret the results.

I get a sense of what SET is about when I talk to the Learning Centre staff and HoD to get tips on how I can improve my teaching.

The Head of School provides support. He knows what is going on in my classroom and how students feel towards my teaching practices. From their feedback, he helps me identify how to correct or improve my teaching.

I share my reports with my mentor … especially if there were aspects that needed addressing and I didn’t know what to do.

Self-designed tools witnessed – SET in practice

YCM

The lecturer wished to use continuous feedback to enhance peer-supported learning, and spoke about his/her the self-designed evaluation tool as follows:

The purpose was to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the Capstone course design used for continuous improvement. … help students develop the required attributes and be able to independently integrate knowledge across their undergraduate and honours level courses.

In the teaching evaluation observed s/he invited them to reflect on the benefits of the course and how it was designed and suggested how new students should be guided to be well-prepared for the course. The following questions were asked in the self-designed tool:

How has engaging in the Capstone project in the last six months helped you understand what is involved in successful construction management?

Given your overall experience of the course, what stage of a construction project are you better prepared to work on?

What have you learnt about your abilities that would make you feel confident to perform as a graduate, construction project manager or give advice to new fellow students?

Are you confident that you can deal with the demands of real construction projects?

What in the course contributed to your confidence or not?

How well do you think you would perform if you were hired as a graduate in the field?

What questions or problems have been raised within the last six months of the course that you think will require further study and rethinking to help the next group of students?

The lecturer appreciated the feedback to the open-ended questions he had designed as follows:

Reading the portfolios made me realise the wealth of feedback that the students are capable of providing when given the opportunity. I had designed a tool to specifically make students focus on the format I used to teach. Questions focused on this aspect.

I think, for a more meaningful exercise, instead of current practices that do not allow for reflections at an appropriate time, we should be allowed, the lecturer/s in partnership with students, to decide the ‘when’ and ‘how’ to do course evaluations … The students are not being heard and that is why they take the exercise with a pinch of salt. Similarly, most of us lecturers are not ready to clash with the old system, so we abide, keep the status quo …

DSS

Used teaching evaluations to establish whether students had achieved the course outcomes related to ‘greater understanding of issues and debates, improved writing and verbal skills, ability to analyse what is going on in the political world.’

When evaluating his teaching s/he probed how students were taking responsibility for their learning by using a tool that focused on how they engaged with the resources provided in the course (lectures, tutorials, access to library material, course material, etc.) and participated in lectures. S/he invited students to reflect and indicate their responses to questions in the tool below.

As a [course name] student, what is your level of participation in the following?

Next to each statement tick either H or M or L, referring to High, Medium or Low participation in activities.

General comments: If any, indicate how effectively you participate in the course and what might enhance your participation:

As a [course name] student, which of these course learning outcomes have you achieved in your view, and to what extent? Next to each statement tick H or M or L, referring to High, Medium or Low achievement of these outcomes.

General comments: If any, what might enable you to better realise these course outcomes:

On reflection, the lecturer indicated being uncomfortable with the tool when s/he said:

I was a bit shy about undertaking this evaluation because I thought students might think that I was trying to turn the spotlight from myself to them to avoid judgement of my own performance. After all, I have power over them, and evaluations are normally their chance to speak back. Students who said harsh things were generally the weaker ones in class participation. Yet, I still cannot say if I appealed more to strong students and less to weak ones. Or did the critical students achieve fewer outcomes because of weaknesses in my teaching?

KGS

KGS taught a service course and used SET to establish reasons for the students’ lack of interest and consequent struggle with understanding course concepts. S/he expressed the concern as follows:

I felt that there is a disconnection between myself and the students inside the classroom. I wanted to find out why students are not interested in the course and struggle to understand concepts so that I can take measures to stimulate and improve their learning.

What should I (student) start doing?

What should I (student) stop doing?

What should I (student) continue doing?

How can the lecturer improve your learning experience?

Like YCM, KGS valued the tool's potential to provide timely and usable student feedback and an opportunity to address identified challenges in the course. In referring to the evaluation tool he had designed s/he said, ‘I employed an informal technique (stop, start and continue) to get instant feedback. The tool is also less intimidating to the students than the institutional system.’ In further justifying the reasons for using such a tool, the lecturer added:

The questions were straightforward and made it easy for students to indicate that the course was pitched too high. Some pointed out I should use a mic because they cannot hear me clearly and that if I change how I teach the course, they will start taking notes, making time to read, and taking the course seriously. However, institutional processes regard such an evaluation as formative but … . its evidence would not hold for probation, confirmation or promotion purposes.

GWS

S/he was concerned that the first-year group took the longest time to adjust to the university environment and ‘find their feet’. S/he used SET to probe this slow transition and overall management of expectations in class and explained the focus as follows, ‘I decided to evaluate students instead (they had already evaluated both me and the course). I thought it would be interesting to ‘get inside their heads’ and see how they approach their studies.'

In the teaching evaluation observed, s/he used a tool that focused on students’ engagement in the learning process, that is, how they approached their studies; used assessment feedback, engaged with course materials, made notes, etc. Questions in the self-designed tool were as follows:

In order to support YOUR learning in the course:

What should you CONTINUE doing?

What should you START doing?

What should you STOP doing?

The lecturer was comfortable with the approach adopted and emphasised the value of the tool by indicating that it focused on the academic skills students needed for learning in higher education and also helped in identifying areas to focus on when supporting students’ transition to learning in higher education.

I wanted to move past the set questions and optional questions used by the university. I prefer qualitative evaluations like this one – the students clearly tell you what they like or dislike, what they are struggling with, so you have something defined for you to work on. With the feedback I have, I am now going to spend much of my introductory lecture advising them on how to cope at university, what is expected of them and how university differs from school − basically managing expectations.

LMS

This lecturer identified students’ poor class attendance as the main challenge in the course. To establish the reasons for non-attendance, s/he used SET.

When observing the online teaching evaluation, it became clear that s/he had prioritised additional questions rather than the university ones and explained the decision as follows:

University evaluations that allow students to evaluate lecturers don’t refer specifically to concepts and skills in the course. It’s not only about being happy during lectures. Evaluations cannot be a substitute for discipline or knowledge standards. However, they could provide useful information about pedagogical knowledge gaps in both lecturers and students’ existing knowledge.

Lectures form a core part of the teaching programme, along with tutorials and self-study.

Overall, do you find lectures make a valuable contribution to the teaching programme?

| 2. | What do you expect from a [name of courses] lecture? | ||||

| 3. | Did you find that the lectures for [name of course] met your expectations as indicated in Q2? | ||||

| 4. | Please elaborate on your answer for Q3. | ||||

| 5. | How many lectures for [course name] would you say that you attended?

| ||||

| 6. | When you did attend lectures, why did you attend the lectures? Choose all that apply | ||||

| 7. | When you didn’t attend lectures, why did you not attend lectures? Choose all that apply. | ||||

| 8. | Thinking about your lecture attendance, are you happy with the number of lectures you attended? | ||||

| 9. | Please let your lecturer know if there is something in her lecture she does especially well. | ||||

| 10. | Please make any specific suggestions as to how your lecturer could improve her lecturing. | ||||

During the individual post-observation reflection sessions, the lecturer indicated that although participation in the survey was low, the feedback was important and generally pointed out ways of engaging students preferred. S/he reacted to their comments as follows, ‘my slides could be more informative (which is interesting, as I designed my slides for an oral presentation, but it seems students want actual lecture notes); my explanations aren’t always clear to follow. Students want comprehensive lecture notes.'

When making general remarks, lecturers pointed out that students’ comments were at times unsettling and dealt with issues beyond their control. This made feedback difficult to use. Below are some examples of what they said,

You have to be able to explain students’ unhappiness; even the venues! It is stressful at times when the evaluation reports refer to areas beyond the control of the lecturer; for example, when referring to lecture venues and IT related matters. Stressful, because it takes more than me to create exciting teaching and learning environments and activities.

For a service course that I teach, and students are compelled to do it … , it is not very helpful nor pleasant. The students’ experience provides little opportunity to maximise the learning benefits. … poor commitment, they are forced to do the course and are not self-motivated. As a result, I am always stressing when opening the envelope to see how I scored against my expectations. They can also be discouraging and demotivating.

The popularity contest can be stressful like any in which one is subjected to judgement by others. They call it accountability, but I have sometimes found the data confusing and difficult to interpret. Sometimes some results don’t make complete sense i.e. they do not seem to reflect objectively provable evidence about a course. To be expected to make sense of it is hard; wanting me to water down my course …

I find Assessment of Lecturer Performance [ALP] – institutional survey – unhelpful. If you get a good, bad, or average score, that is one thing, but you have absolutely no idea why your score is what it is.

Discussion

The SET policy proved challenging to understand as an educational or social project involving numerous aspects/elements, in Latour’s (Citation2005) terms, human and non-human, that had to be collectively given equal status, recognition and connected when thinking and expressing views on it. The lecturers understood it (policy) as primarily a resource for improving the quality of teaching and satisfying students’ expectations and learning outcomes. For example, SET helped YCM to find out how to improve the course and teaching and DSS how to be effective in supporting learning. KGS reinforce the good and address concerns, GWS improve students’ transition to learning (in higher education) and LMS make concepts accessible. Questionnaire responses and explanations of the self-designed tools also highlighted the value the lecturers attached to students’ feedback/responses for improving, in general, their courses. For example, the responses were used to establish students’ view on the benefit of the course and how to prepare new students for the course (YCM), what students thought of their participation in lectures and meeting learning outcomes (DSS), reasons for students’ lack of interest in the course and struggle with understanding concepts (KGS), how students approached their studies (GWS) and ways of engaging preferred by students (LMS). However, relationships and connections between aspects emphasised as important in the policy; amongst others, students’ experience/biographies, technological resources and condition of the lecture rooms; were not referred to as equally important nor did the lecturers seem to understand these aspects as part of what shaped teaching and learning and needed to be included in evaluations. Exceptions were, for example, YCM’s emphasis on the need to evaluate ‘ … a communication style that is traditional … not appropriate to the current cohort of students … ’ and, GWS’s wish to establish how s/he could better ‘get inside their heads’.

Perceptions and discourses on the SET policy as a proposed course of action and part of the reality and ‘everyday ness’ of teaching and learning within University X (Ybema and Kamsteeg Citation2009) could therefore, be considered as philosophically rigorous in a Latourian (Citation2013) sense only if the lecturers referred to and explained the logic and path they used in, for example, designing tools and conducting evaluations in ways that included and related all aspects proposed as crucial to engage with in the policy. The gaps or partial interpretations/associations made to the policy thus made evaluation reports in KGS’s view, ‘ … always so factual and dry’. Nsibande (Citation2022) has also argued that narrow and restrictive interpretations of student feedback are a result of focusing on specific areas of teaching, neglecting broader aspects related to the teaching context and disciplines. This lack of references [REFs] and relations [RELs] (Latour Citation2005) to the multi-layered aspects of the SET policy that is significant to its effective implementation thus created category mistakes in the lecturers’ perceptions and discourses.

Detaching the SET policy from its socio-historical context also compromised its organic connection to the various social and physical levels that constituted its reality (Kincheloe Citation2006). As Ryan (Citation2015, 1144) argues, the partly standardised survey employed in the university not only decontextualised SET but overlooked other variables that often impact teaching and learning and ought to be considered in evaluating these social activities.

Ball (Citation2012) argued that the culture of performativity in higher education has moved attention from crucial knowledge-related issues to personalities that provide a service that should please students as its recipients. It is therefore possible that the pressures of accountability, recognition and reward system, may be making it difficult for the SET policy to achieve its purpose fully. Its proper and philosophically rigorous understanding is impossible without understanding it as embodying human and non-human aspects (people and context) that are seamlessly connected, as Latour (Citation2005) proposes.

Conclusion

We understood the gaps in the lecturers’ perspectives and discourses as the result of a realism within University X that is perhaps making it challenging to adapt to the post-apartheid educational ideals for higher education. Lecturers seemed to be influenced mainly and uncritically by the explicit ‘use by intended users’ (Patton Citation1990) concept that seemed to underpin the university’ SET policy and stance on career progression. For this reason, without deliberate and focused interventions on all crucial parts embodied in the SET policy, its effectiveness remains fragile and threatened, especially for those determined and who cannot stray from the core questions provided for SET. Therefore, it is recommended that policy custodians (senior management and academic support) championing SET and using SET feedback should be encouraged to engage more thoughtfully and critically to ensure the context supports appropriate perceptions and discourses. This will contribute to further professionalising lecturers on the role of SET in teaching and learning as those who enact policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ball, S. 2012. “Performativity, Commodification and Commitment: An I-Spy Guide to the Neoliberal University.” British Journal of Educational Studies 60 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2011.650940

- Blackmore, J. 2009. “Academic Pedagogies, Quality Logics and Performative Universities: Evaluating Teaching and What Students Want.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (8): 857–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902898664

- Bovill, C. 2011. “Sharing Responsibility for Learning Through Formative Evaluation: Moving to Evaluation as Learning.” Practice and Evidence of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 6 (2): 95–109.

- Brewington, Q. L., and N. J. Hall. 2018. “Givin’ Stakeholders the Mic: Using Hip-Hop’s Evaluation Voice as a Contemporary Evaluation Approach.” American Journal of Evaluation 39 (3): 336–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214018769765

- Button, G. 2000. “The Ethnographic Tradition and Design.” Design Studies 21 (4): 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(00)00005-3

- Chiseri-Strater, E. 1996. “Chapter 7: Turning in Upon Ourselves: Positionality, Subjectivity, and Reflexivity in Case Study and Ethnographic Research.” In Ethics and Representation in Qualitative Studies of Literacy, edited by P. Mortesen and G. E. Kirsh, 115–133. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2011. Research Methods in Education. 7th ed. London: Routledge.

- Cunliffe, A. L. 2010. “Retelling Tales of the Field in Search of Organizational Ethnography 20 Years On.” Organizational Research Methods 13 (2): 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109340041.

- Fairclough, N. 2003. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Edinburgh Gate: Longman.

- Jayathilaka, A. 2021. “Ethnography and Organizational Ethnography: Research Methodology.” Open Journal of Business and Management 9 (01): 91–102. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2021.91005.

- Jeffrey, B., and G. Troman. 2004. “Time for Ethnography.” British Educational Research Journal 30 (4): 535–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000237220.

- Kember, D., D. Leung, and K. P. Kwan. 2002. “Does the Use of Student Feedback Questionnaires Improve the Overall Quality of Teaching?” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 27 (5): 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293022000009294

- Kincheloe, J. L. 2006. “Critical Ontology and Indigenous Ways of Being: Forging a Post-Colonial Curriculum.” In Integrating Aboriginal Perspectives Into the School Curriculum. Purposes, Possibilities and Challenges, edited by Y. Kanu, 181–202. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Kivunja, C., and A. B. Kuyini. 2017. “Understanding and Applying Research Paradigms in Educational Contexts.” International Journal of Higher Education 6 (5): 26–41. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, B. 2013. An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence. Translated by C. Porter. London: Harvard University Press.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Moyo, N. 2016. “The Interrelationship of Theory and Practice in In-Service Teacher Learning: Modes of Address in History Teaching in Masvingo District: Zimbabwe.” Unpublished DPhil thesis, University of Johannesburg.

- Nsibande, R. 2022. “Towards Response-Able Student Evaluation of Teaching Through Question Personalisation: Drivers and Barriers for Change.” Journal of Educational Studies Special Issue 1: 210–226.

- Patton, M. 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Polkinghorne, D. 1995. “Narrative Configuration in Qualitative Analysis.” In Life History and Narrative, edited by J. Hatch and R. Wisniewski, 5–23. London: Falmer Press.

- Ryan, M. 2015. “Framing Student Evaluations of University Learning and Teaching: Discursive Strategies and Textual Outcomes.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 40 (8): 1142–1158. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.974503

- Saunders, M. 2012. “The use and Usability of Evaluation Outputs: A Social Practice Approach.” Evaluation 18 (4): 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012459113

- Saunders, M., B. Charlier, and J. Bonamy. 2005. “Using Evaluation to Create ‘Provisional Stabilities’: Bridging Innovation in Higher Education Change Process.” Evaluation 11 (1): 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389005053188

- Shulha, L. M. 2000. “Evaluative Inquiry in University-School Professional Learning Partnerships.” New Directions for Evaluations 88: 40–53.

- Steyn, C., C. Davies, and A. Sambo. 2019. “Eliciting Student Feedback for Course Development: The Application of a Qualitative Course Evaluation Tool among Business Research Students.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (1): 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1466266

- Tobin, J., and D. Davidson. 1990. “The Ethics of Polyvocal Ethnography: Empowering vs. Textualizing Children and Teachers.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 3 (3): 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839900030305

- Tummons, J. 2021. “Ontological Pluralism, Modes of Existence, and Actor-Network Theory: Upgrading Latour with Latour.” Social Epistemology 35 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2020.1774815.

- Yanow, D. 2009. “Organizational Ethnography and Methodological Angst: Myths and Challenges in the Field.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 4 (2): 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465640910978427.

- Ybema, S., and F. Kamsteeg. 2009. “Making the Familiar Strange: A Case for Disengaged Organizational Ethnography.” In Organizational Ethnography: Studying the Complexities of Everyday Life, edited by S. B. Ybema, D. Yanow, H. Wels, and F. H. Kamsteeg, 110–119. London: Sage.