Abstract

Even though injury is common in elite sports, there is still a lack of knowledge of young athletes’ injury perception both during and after injury. The aim of this mixed-method study was, therefore, to explore, in-depth, data on injury consequences and adolescent elite athletes’ perceptions and experience of injury. Three hundred and forty adolescent elite athletes (age range 15–19), from 16 different sports, were bi-weekly monitored over 52 weeks using a valid questionnaire. Twenty athletes from the same cohort were interviewed in focus groups about injury experience and perceptions. The results show that the average bi-weekly prevalence of injury was 38.7% (95% CI 37.3–40.1), with 30.0% (n = 102) of the athletes injured for more than half of all reporting times. An overarching theme from the focus groups highlighted the risk among young athletes of a loss of identity while injured. The findings support several suggestions that may improve the rehabilitation process and enhance rehabilitation outcomes: (a) provide clear pathways to the medical team, (b) recognize the identity loss, (c) involve the injured athletes with the rest of the teammates and (d) educate athletes about how to interpret pain signals. Future research should explore and evaluate the effectiveness and generalization of such interventions.

Highlights

The injury risk is high in adolescent elite athletes, with higher risk of injury in female athletes compared to male athletes.

Injuries have consequences on sports involvement and performance, but may also lead to experiencing negative psychological responses (frustration, anger), daily living activity consequences (sleep disturbances, study issues), as well as feelings of loneliness, self-blame or self-criticism, in adolescent elite athletes.

Sports involvement seems to constitute an important part of an adolescent elite athlete’s life, while injury may lead to a loss of identity.

Introduction

The high participation in sports activities has resulted in sports being the primary cause of injury in young people (Emery, Citation2003; Abernethy & Bleakley, Citation2007; Goldberg, Moroz, Smith, & Ganley, Citation2007), with probably the highest injury rates in competitive athletes such as adolescent elite athletes (DiFiori et al., Citation2014). Even if long-term injury surveillances reports are lacking in several sports of adolescent elite athletes (Steffen & Engebretsen, Citation2010), the existing ones have shown high injury incidence (Kolt & Kirkby, Citation1999; Kirialanis, Malliou, Beneka, & Giannakopoulos, Citation2003; Price, Hawkins, Hulse, & Hodson, Citation2004; Le Gall et al., Citation2006; Le Gall, Carling, & Reilly, Citation2008; Westin, Alricsson, & Werner, Citation2012; Jacobsson et al., Citation2013) as well as high injury prevalence (Jacobsson et al., Citation2012; von Rosen, Frohm, et al., Citation2016; von Rosen, Heijne, et al., Citation2016). These findings highlight a need for exploring the consequences of such injuries.

The recent development of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) Overuse Injury Questionnaire (Clarsen, Myklebust, & Bahr, Citation2013) has led to that consequences of injury, based on self-reported data, can be explored in a reliable and valid manner. However, injuries may lead to other individual consequences that may be hard to capture based on questionnaires (Wiese-bjornstal, Smith, Shaffer, & Morrey, Citation1998). The majority of studies (Jacobsson et al., Citation2012; Kolt & Kirkby, Citation1999; Kirialanis et al., Citation2003; von Rosen, Frohm, et al., Citation2016; von Rosen, Heijne, et al., Citation2016) have used a quantitative method to identify injury consequences or focused on a qualitative approach mainly including adult athletes (Clement, Arvinen-Barrow, & Fetty, Citation2015; Ruddock- Hudson, O’Halloran, & Murphy, Citation2014). A mixed-method approach on adolescent elite athletes is lacking, and by combining quantitative and qualitative methodology, an in-depth understanding of injury consequences in young elite athletes could be obtained.

A number of psychological factors associated with injuries in various sports have been implicated, such as anxiety, frustration, depression, low self-esteem, rage, depression, fatigue, insomnia, loss of appetite, disbelief and low coping skills (Hardy, Richman, & Rosenfeld, Citation1991; Lavallée & Flint, Citation1996; Smith, Citation1996; Johnston & Carroll, Citation1998; Finnoff, Citation2012; Clement et al., Citation2015). Factors influencing return to sports participation post-injury are motivation, confidence and the fear of re-injury (Podlog & Eklund, Citation2004; Ardern, Taylor, Feller, & Webster, Citation2013). Although the abovementioned psychological factors associated with injuries are likely to be relevant in adolescent athletes, adolescent elite athletes differ from adult athletes in several aspects. For example, adolescent elite athletes are in the beginning of their sport career and probably not as used to being injured as adult athletes. They are also not used to handle performance expectations from coaches, parents, competitors (Merkel, Citation2013) or setbacks when returning to sports participation following an injury period, compared to adult elite athletes. In addition, the close relationship between injury and athlete-identity has previously been highlighted in adult elite athletes (Brewer, Selby, Under, & Petttpas, Citation1999; Grove, Fish, & Eklund, Citation2004), yet the impact of injury or missed sports participation for the self-identity in a young elite athlete is limited explored.

More in-depth knowledge is crucial in order to understand the interaction between various psychological factors and the social environment over time, also in order to understand how various rehabilitation approaches may impact in different ways on athletes. We, therefore, decided that combining interviews of adolescent elite athletes in focus groups with prospective recorded injury data would generate a more in-depth understanding of injury experiences, consequences and perceptions. The aim of this mixed-method study was, therefore, to explore, in-depth, data on injury consequences and adolescent elite athletes’ perceptions and experience of being injured.

Methods

In this mixed-method study, focus groups interviews were carried out with adolescent elite athletes and an online questionnaire about the experience of injuries were bi-weekly distributed over a year to these athletes. Ethical approval has been received from the Regional Ethical Committee in Sweden (2011/749-31/3, 2015/288-32).

Recruitment process and participants

Recruitment of participants was conducted from September 2013 to December 2014. The National Federations of Sports in Sweden were invited to participate in this project. The National Federation of American football, Athletics, Bowling, Canoe, Cycling, Golf, Handball, Orienteering, Rowing, Skiing, Water ski, Wrestling and Triathlon, accepted participation. A total of 24 National Sports High Schools were then invited. The available cohort consisted of 494 adolescent elite athletes (age range 15–19), representing 16 different sports; athletics, cross-country skiing, orienteering, ski-orienteering, handball, down-hill skiing, freestyle skiing, water skiing, canoe, rowing, wrestling, bowling, triathlon, golf, cycling and American Football. One of the authors visited each school to inform the coaches and the athletes about the purpose of the study and written consent was obtained.

All athletes were then invited by e-mail, of which 430 athletes (87.0%) responded to the invitation. A questionnaire was bi-weekly e-mailed to the athletes over a period of 52 weeks. If no response was registered, a reminder e-mail was sent four days later. In addition, an online background questionnaire was distributed to all athletes during the first week of the study. The software Questback online survey (Questback V. 9.9, Questback AS, Oslo, Norway) was used for data collection.

In line with Clarsen, Bahr, Andersson, Munk, and Myklebust (Citation2014), we excluded athletes due to insufficient data, resulting in the exclusion of 90 athletes with less than 10% response rate on an individual level. Importantly, the excluded athletes did not differ from the cohort under investigation, regarding sex (p = .556) or injury at study start (p = .820). Consequently, the final cohort consisted of 340 adolescent elite athletes (female = 155, male = 185), with an average age of 17 (range 15–19).

Questionnaire and operational definitions

The questionnaire consisted of three parts; (1) the validated and translated version of the OSTRC Overuse Injury Questionnaire (Clarsen et al., Citation2013), (2) questions about new injury occurrence, described by Jacobsson et al. (Citation2013) and (3) questions about return to sport after an injury, described by Jacobsson et al. (Citation2013). However, in this study, only part one was analysed. The OSTRC Overuse Injury Questionnaire addresses injury consequences on sports participation, performance, training and pain based on four questions with alternative responses. Please see Clarsen et al. (Citation2013 for additional information. The completion of the questionnaire took approximately five minutes.

Based on the OSTRC Overuse Injury Questionnaire, an injury was defined as any physical complaint that affected participation in normal training or competition, led to reduced training volume, experience of pain or reduced performance in sports (Clarsen et al., Citation2013). A substantial injury was defined as an injury leading to moderate or severe reductions in training volume, or moderate or severe reduction in performance, or complete inability to participate in sports.

Data analysis prospective injury data

The response rate for the population was determined by dividing the number of responded athletes with the total number of athletes each week. The injury prevalence measure was calculated, by dividing the number of athletes reporting any injury by the number of questionnaire respondents. A similar calculation was performed for substantial injury as well as for the injury consequence variables (sports participation, performance, training and pain). The prevalence of injury, substantial injury, injury consequence variables and response rate were presented as bi-weekly averages for all athletes and by sex. Differences regarding the current injury at study start, for all athletes and between sexes, were analysed using the chi-square test. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed for all injury prevalence variables. All analyses were performed using the SPSS software for Windows, version 22.0 (SPSS, Evanston, IL).

Participants and recruitment process regarding the focus group interviews

The athletes were recruited from the main cohort described above. The inclusion criteria for the focus group interviews were as follows: (1) adolescent elite athletes studying on Swedish National Sports High Schools and (2) have had an injury that affected participation in their main sport, resulting in reduced training volume, experience of pain or reduced performance in sports, for at least four continuous weeks in the last year. The chosen injury time of four weeks was based on previous studies (Bianco, Malo, & Orlick, Citation1999; Bianco, Citation2001).

Swedish National Sports High Schools were strategically chosen by categorizing schools in groups based on the distance between schools. A maximum distance of 1.5 h by train between schools was allowed in each group, set in order to limit athletes travelling, resulting in that the coaches of nine Swedish National Sports High Schools of athletics, golf, canoe, orienteering, bowling, cross-country skiing, down-hill skiing and freestyle skiing were contacted. The coaches at each school asked the athletes, who met the inclusion criteria, if interested in participating in an interview-based study regarding injury experience. This resulted in that 24 athletes contacted the authors (2–3 athletes/school), of which 20 athletes (male = 8, female = 12) were enrolled based on a strategically sample selection to maximize variation regarding gender, injuries and sports participation. Consequently, five focus groups (4–6 adolescent elite athletes per group), with a mix of male and female athletes from different sports were formed. The athletes were representing the following sports; athletics jumping (n = 2), sprint (n = 2), middle-distance (n = 3), golf (n = 2), canoe (n = 1), orienteering (n = 2), bowling (n = 3), cross-country skiing (n = 2), down-hill skiing (n = 1) and freestyle skiing (n = 2). The athletes had been injured between 2 months and 4 years, with 5 athletes (20.0%) still injured at the time of the interview.

The focus group interviews

A semi-structured interview guide was initially developed by two experienced physiotherapists in sports medicine. The interview guide consisted of questions addressing an individual’s experience the period before injury, while injured and post-injury. Two pilot focus group interviews were then conducted. After these interviews some changes were added to the interview guide, involving questions about social support and injury consequences. The pilot interviews were not used for data analysis. The interview guide is presented in Appendix.

The interviews were carried out from April to November 2015. The interviewer was a physiotherapist with clinical experience in sports medicine and injury rehabilitation. At the time of the interviews, written informed consent was initially obtained from the athletes regarding participation in this part of the study. All interviews lasted between 25 and 42 min (average 29 min) and were all tape recorded. During the interviews, open-ended questions were attempted to be used, even if this does not completely hold during follow-up questions. The interviews were then transcribed verbatim (47 pages) by the first author.

Data analysis interview data

The semi-structured interview data were analysed using an inductive content analysis as described by Graneheim and Lundman (Citation2004). Following Graneheim and Lundman (Citation2004), a five-step approach in this content analysis was adopted, namely (1) data familiarization, (2) generation of initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes and (5) defining and naming themes. The text material was initially read thoroughly several times by three of the authors (PvR, AH, AK), two physiotherapists and one occupational therapist. Following the inductive process, the three authors initially coded the text into meaning units, i.e. words and statements relevant to the aim of the study. All meaning units were then condensed and grouped into “subthemes”, “higher order themes” along with an overarching main theme, using a back and forth iterative ongoing process. Comparisons and discussions indicated a high level of agreement between the selections of meaning units.

It was secured that the “subthemes” were exclusive, however meaning units not relevant for the aim was not arranged in “subthemes”. The analyses were at first performed individually, then circulated between the three authors with feedback and finally discussed during face-to-face meetings to achieve consensus. This allowed for incorporating different perspectives and interpretations on the data analysis and findings, as well as supporting collaboration to identify the most suitable “subthemes” and “higher order themes”.

Results

Prospective injury data

At the start of the study, 157 (46.2%) adolescent elite athletes reported to be injured, with a significantly (p = .023) higher proportion of injured female athletes (52.9%, n = 82), compared to male athletes (40.5%, n = 75). The average bi-weekly response rate was 58.4% (95% CI 55.2–61.6).

Over the 52 weeks, the average bi-weekly prevalence of injury was 38.7% (95% CI 37.3–40.1) and 18.3% for substantial injury (95% CI 17.3–19.3) (). Female athletes reported a significantly (p < .05) higher average bi-weekly prevalence of injury (43.9%, 95% CI 42.3–45.5) and substantial injury (20.6%, 95% CI 19.0–22.3), compared to male athletes (34.5%, 95% CI 32.5–36.4; 16.4%, 95% CI 14.9–17.8).

Table I. The average bi-weekly prevalence of injury in percent, for all athletes and by sex, with 95% CI in parenthesis.

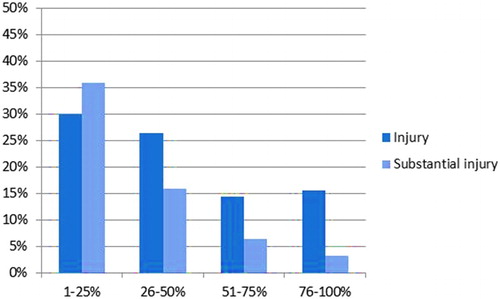

Of all athletes, 30.0% (n = 102) were injured more than half of all reporting times and 9.7% (n = 33) reported substantial injury more than half of the reporting times (). A higher fraction of female athletes reported a longer time of being injured, of which 38.7% (n = 60) were injured more than 50% of the reporting times and 11.0% (n = 17) reported substantial injury more than 50% of the reporting times, compared to male athletes (22.7%, n = 42; 8.7%, n = 16, respectively).

Interview data

The inductive content analysis led to those 15 – subthemes, 3 – “higher order themes” ((1) personal and environmental factors influencing the recovery process, (2) experiences and lessons learned from injury and (3) questioning the life-role as an elite athlete) and 1 – “overarching theme”, “Injury as a threat to the identity of a young athlete”, were derived from the analysis of the interviews (). The qualitative findings of the focus group interviews revealed a complementary and more complex pattern of injury consequences among adolescent elite athletes, compared to the prospective injury data.

Table II. Higher order themes, subthemes and examples of quotations.

Personal and environmental factors influencing the recovery process

A variety of important factors influencing the recovery process were identified by the participants in the first “higher order theme”. Aspects such as social support (or lack of), various coping strategies to be used in order to adapt to the new situation, and the importance of identifying the correct injury cause, were described as factors that influenced the injury recovery. As one participant stated in relation to the use of coping strategies:

Everybody gets injured and you have to accept the injury to be able to continue with sports participation. (Male participant from Focus group 3, line 253)

One dilemma described was the discrepancy in the rehabilitation process between the athlete and the practitioner. As an example, starting the rehabilitation with low-dose exercises was by some of the participants experienced as a further additional threat to the athlete’s identity, as the athlete was used to train with high power/volume. In addition, spending most time of the rehabilitation or alternative training alone, not being part of the elite athlete group anymore, was further perceived as being excluded from a social sport context.

The athletes also described feelings of concerns and questioning returning to future sports participation, due to the risk of re-injury. This fear of not reaching the same physical status or performance level as before the injury was expressed by the athletes, and contributed to the overarching theme: Injury as a threat to the identity of a young athlete.

Experiences and lessons learned from injury

The second “higher order theme” addresses the described experiences, increased knowledge and the development of prevention skills following the injury period. The athletes expressed reflections of an increased motivation, aspects on improving self-confidence, and also feeling mentally stronger following the rehabilitation of an injury. This was expressed by one participant as:

I am more motivated due to my injury. I want to run again and perform at maximum effort at the next training session. I cannot wait.

Finally, the perception of pain was also changed following the injury period, as described by the participants. Before the injury, they perceived their pain as a natural part associated with normal sports participation and did not recognize this as a sign of injury. However, after the athletes had been injured they described an increased awareness to injury threats and an increased awareness of their own body.

Questioning the life-role as an elite athlete

The third “higher order theme” relates to the consequences of injury on a more identity and psychological level, resulting in that the athletes started to question their reasons for continuing with elite sports. It also illustrates the complexity of the athletic identity and the uncertainty of the identity that is created when the athletes are withdrawn from their regular sports involvements.

The athletes also expressed a need to still be considered as a part in a group, receiving attention and admirations from others, as they were withdrawn from the regular contexts within the elite sports, where such recognitions are supported and received on a more regular basis. While injured, a feeling of loneliness was strikingly apparent in the participants’ descriptions. This was expressed by one participant as:

Your friends are training and it is like you should not be with them. You are just alone by yourself. You seat and do some easy rehab, but you are just alone.

Friends’ perceptions were described as highly important and the participants described how they sought to be recognized and acknowledged by their friends and teammates as a “normal” athlete and not as “the injured” one. This was expressed by one athlete:

Everybody should see the ones who are injured. See them. Talk to them. Acknowledge their training. And try to talk to them about something other than their injury.

Injury as a threat to the identity of a young athlete

All the processes in the “higher order themes” described above contributed to that the athletes, for the first time, started to question if elite sports were appropriate for them. This overarching theme reflects that some young elite athletes perceived a loss of identity while injured along with associated individual factors (i.e. perceptions by friends, loneliness) and environmental factors (i.e. social support, rehabilitation discrepancy) that may affect the identity process. The close relation between athlete and identity is illustrated by the following citation:

It’s who I am. I am an athlete, it’s the first thing I say. If that is not the case, then what?

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies addressing injury consequences in adolescent elite athletes using a quantitative and qualitative methodology. Exploring young athletes’ perception and experience of injury led to that an overarching theme “Injury as a threat to the identity of a young athlete” was identified. This theme illustrates that young athletes may experience a loss of identity while injured. The results are discussed in relation to rehabilitation actions and for developing strategies in preventing the long-term consequences injuries may lead to in this age.

Injury consequences

The first part of this study addresses the high average prevalence of injury in this population. It was found that 30.0% of the athletes reported injury and 9.7% substantial injury for more than half of the season. Female athletes reported a higher average injury prevalence (43.9%) compared to male athletes (34.5%), with a less significant difference for substantial injury (20.6% vs 16.4%), showing that both sexes are exposed to long-term injuries. The high average injury prevalence in this population, in line with studies on similar populations (Kolt & Kirkby, Citation1999; Kirialanis et al., Citation2003; Price et al., Citation2004; Westin et al., Citation2012; Jacobsson et al., Citation2013; von Rosen, Frohm, et al., Citation2016; von Rosen, Heijne, et al., Citation2016), highlight a need of exploring the injury consequences as well as injury experiences of young injured athletes. Our qualitative findings add to the picture of injury consequences by showing that some of the athletes experienced negative psychological responses (frustration, anger), daily living activity consequences (sleep disturbances, study issues), as well as experience of loneliness, self-blame or self-critics. Therefore, the combination of mixed data provided a more in-depth picture of injury consequences in this sample of athletes.

Athlete-identity

Diminish of self-identity while injured (Brewer & Cornelius, Citation2010; Grindstaff, Wrisberg, & Ross, Citation2010) or when sports participation is threatened (Sparkes, Citation1998; Brewer et al., Citation1999; Grove et al., Citation2004) have previously been explored in adult elite athletes. In this study, the manifested theme “Injury as a threat to the identity of a young athlete” describes that the self-identity is under threat even in young injured athletes and that the athletes are questioning their self-identity and lose track of their own identity without sports involvement. Even if similar findings have demonstrated in adult athletes this finding may be more crucial in adolescents due to that the identity exploration is of such importance in this life stage. The consequences of diminishing of self-identity in such young athletes are unclear but could be interpreted as injury or missed sports participation have a greater impact on identity in this age group than in adult athletes. In line with a report of a similar population of young athletes, using quantitative data from web-based questionnaires, von Rosen, Frohm, et al. (Citation2016) and von Rosen, Heijne, et al., (Citation2016) suggest that some adolescent elite athletes develop a large part of their identity or self-esteem on competence, performance or competition results. Identifying athletes with such attributes may suggest which athletes that might respond more negatively to injury in terms of self-identity which also might be an important factor to address during the rehabilitation stage following sports injury.

Rehabilitation process

Discrepancies in rehabilitation expectations and goals between athletes and practitioner have been recommended to be highlighted at the start of the rehabilitation (Potter, Gordon, & Hamer, Citation2003). In this study, some athletes commented that their rehabilitation was not adjusted for them in their current life situation, likely affecting rehabilitation outcomes. The athletes also requested to receive an injury diagnosis in an early stage. However, barriers in receiving a diagnosis existed in this population. At some school, there was a direct access to medical staff, whereas at other school, the athletes were responsible to make contact and find adequate medical care on their own. By reducing the gap and enhance the cooperation between the medical team and the coaches, the path to an injury diagnosis may be quicker and smoother. This is likely also beneficial for the rehabilitation process, may lead to a complete rehabilitation and contribute to that the athletes will be more prepared to return to sports.

Include injured athletes

In young people, friends, family and the social context are of high importance (Crosnoe, Cavanagh, & Elder, Citation2003). While injured, some athletes describe how they are feeling excluded, lonely and losing their position in the team or training group. Attempt to involve the injured athlete with their teammates in sports activities or in less physical demanding activities (sports theory, tactic demonstrations) was acknowledged as relevant and important. By encouraging injured athletes to perform parts of their rehabilitation among friends and visiting training sessions, even if sport participation is not possible, may lead to that the athletes keep their place as an “athlete” in a sport environment instead of perceiving themselves as “ex-athletes”.

Changed pain image

It is concerning that those adolescent elite athletes with limited experience of injury associate pain with normal sports participation. Even if it seems to be common for athletes to experience pain associated with sports (Bahr, Citation2009), the consequences are unclear. However, it is reasonable to assume that accepting pain during long-term sports participation may affect the body’s “alarm” system, risking either a chronic pain problem or a more serious injury, e.g. repeated bone stress could result in a stress fracture (DiFiori et al., Citation2014). After injury experience, the pain image changed, from accepting pain to recognizing pain as an abnormal training response. Educational interventions targeting the relation of pain and normal sports participation in the early phase of a young elite athlete career could be relevant and possibly lead to increased body awareness. In addition, letting previous injured athletes share their experiences with younger elite athletes could lead to the development of role-models and that pain as an ordinary training response is not normalized.

Methodological considerations

By combining both quantitative and a qualitative data using a mixed-method design and by involving multiple authors in the data analysis, a wider and deeper perspective of injury perception, through triangulation, was achieved. However, the response rate associated with the quantitative findings may have led to an underestimation of the true injury prevalence, according to Clarsen et al. (Citation2013). By interviewing athletes with a mix of injuries, from different schools and sports, enriches the perspective of athlete’s injury experiences and enhance credibility. The fact that authors, with different professional profiles (physical therapist, occupational therapist) and experience (sport injuries, disabilities), were involved in all steps of the data analysis, also facilitated the credibility.

The evolving interview process led to that the interviewer developed techniques and more insight into the phenomenon, which may have influenced the follow-up questions and thereby affected the dependability (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). However, the semi-structured interview guide was used in all interviews and all athletes were requested to participate in the discussion and to answer all questions, to ensure stability in data collection. The data were collected over two semesters and all athletes met the inclusion criteria of having an injury for at least four weeks the last year. However, some athletes had been injury free for several months at the time of the interview, while a lower proportion of athletes were still injured and in the last stage of their rehabilitation. This was done to provide a deeper perspective, including both injured and non-injured athletes experience. The concept of injury as a threat to athlete’s self-identity has previously been explored in adult elite athletes (Brewer & Cornelius, Citation2010; Grindstaff et al., Citation2010), which may facilitate transferability to elite athletes in general.

Clinical implications

Based on the finding of this study the following implications are recommended:

Reduce the gap and enhance the cooperation between the medical team and the coaches, and thereby provide clear pathways for the athletes to the medical team

Educate medical staff providers about consequences of injury in adolescent elite athletes

Change the image of pain as a normal condition. Allow for transparent communication about injury risks and causes

Use the experiences from injured athletes in education to show how injury can support maturation, athlete development, and minimize self-blame

Maintain injured athletes in most parts of training and exercise

Address social support, group inclusion and identity of the injured athletes

Explain the aims, stages and the athlete’s role in the rehabilitation process

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Anders Kottorp http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8976-2612

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abernethy, L., & Bleakley, C. (2007). Strategies to prevent injury in adolescent sport: A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(10), 627–638. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.035691

- Ardern, C. L., Taylor, N. F., Feller, J. A., & Webster, K. E. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(17), 1120–1126. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091203

- Bahr, R. (2009). No injuries, but plenty of pain? On the methodology for recording overuse symptoms in sports. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(13), 966–972. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.066936

- Bianco, T. (2001). Social support and recovery from sport injury: Elite skiers share their experiences. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 72(4), 376–388. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2001.10608974

- Bianco, T., Malo, S., & Orlick, T. (1999). Sport injury and illness: Elite skiers describe their experiences. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 70(2), 157–169. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608033

- Brewer, B. W., & Cornelius, A. E. (2010). Self-Protective changes in athletic identity following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(1), 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.09.005

- Brewer, B. W., Selby, C. L., Under, D. E., & Petttpas, A. J. (1999). Distancing oneself from a poor season: Divestment of athletic identity. Journal of Personal and Interpersonal Loss, 4(2), 149–162. doi: 10.1080/10811449908409723

- Clarsen, B., Bahr, R., Andersson, S. H., Munk, R., & Myklebust, G. (2014). Reduced glenohumeral rotation, external rotation weakness and scapular dyskinesis are risk factors for shoulder injuries among elite male handball players: A prospective cohort study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(17), 1327–1333. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093702

- Clarsen, B., Myklebust, G., & Bahr, R. (2013). Development and validation of a new method for the registration of overuse injuries in sports injury epidemiology: The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) overuse injury questionnaire. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(8), 495–502. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091524

- Clement, D., Arvinen-Barrow, M., & Fetty, T. (2015). Psychosocial responses during different phases of sport-injury rehabilitation: A qualitative study. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(1), 95–104. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.52

- Crosnoe, R., Cavanagh, S., & Elder, G. H. (2003). Adolescent friendships as academic resources: The intersection of friendship, race, and school disadvantage. Sociological Perspectives, 46(3), 331–352. doi: 10.1525/sop.2003.46.3.331

- DiFiori, J. P., Benjamin, H. J., Brenner, J. S., Gregory, A., Jayanthi, N., Landry, G. L., & Luke, A. (2014). Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: A position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(4), 287–288. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093299

- Emery, C. A. (2003). Risk factors for injury in child and adolescent sport: A systematic review of the literature. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 13(4), 256–268. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200307000-00011

- Finnoff, J. T. (2012). Preventive exercise in sports. PM&R, 4(11), 862–866. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.08.005

- Goldberg, A. S., Moroz, L., Smith, A., & Ganley, T. (2007). Injury surveillance in young athletes: A clinician’s guide to sports injury literature. Sports Medicine, 37(3), 265–278. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737030-00005

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Grindstaff, J. S., Wrisberg, C. A., & Ross, J. R. (2010). Collegiate athletes’ experience of the meaning of sport injury: A phenomenological investigation. Perspectives in Public Health, 130(3), 127–135. doi: 10.1177/1757913909360459

- Grove, J. R., Fish, M., & Eklund, R. C. (2004). Changes in athletic identity following team selection: Self-protection versus self-enhancement. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 16(1), 75–81. doi: 10.1080/10413200490260062

- Hardy, C. J., Richman, J. M., & Rosenfeld, L. B. (1991). The role of social support in the life stress/injury relationship. The Sport Psychologist, 5(2), 128–139. doi: 10.1123/tsp.5.2.128

- Jacobsson, J., Timpka, T., Kowalski, J., Nilsson, S., Ekberg, J., Dahlström, Ö, & Renström, P. A. (2013). Injury patterns in Swedish elite athletics: Annual incidence, injury types and risk factors. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(15), 941–952. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091651

- Jacobsson, J., Timpka, T., Kowalski, J., Nilsson, S., Ekberg, J., & Renström, P. (2012). Prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries in Swedish elite track and field athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(1), 163–169. doi: 10.1177/0363546511425467

- Johnston, L. H., & Carroll, D. (1998). The context of emotional responses to athletic injury: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 7(3), 206–220. doi: 10.1123/jsr.7.3.206

- Kirialanis, P., Malliou, P., Beneka, A., & Giannakopoulos, K. (2003). Occurrence of acute lower limb injuries in artistic gymnasts in relation to event and exercise phase. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 37(2), 137–139. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.2.137

- Kolt, G. S., & Kirkby, R. J. (1999). Epidemiology of injury in elite and subelite female gymnasts: A comparison of retrospective and prospective findings. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 33(5), 312–318. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.33.5.312

- Lavallée, L., & Flint, F. (1996). The relationship of stress, competitive anxiety, mood state, and social support to athletic injury. Journal of Athletic Training, 31(4), 296–299.

- Le Gall, F., Carling, C., & Reilly, T. (2008). Injuries in young elite female soccer players: An 8-season prospective study. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(2), 276–284. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307866

- Le Gall, F., Carling, C., Reilly, T., Vandewalle, H., Church, J., & Rochcongar, P. (2006). Incidence of injuries in elite French youth soccer players: A 10-season study. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(6), 928–938. doi: 10.1177/0363546505283271

- Merkel, D. L. (2013). Youth sport: Positive and negative impact on young athletes. The Journal of Sports Medicine, 4, 151–160. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S33556

- Podlog, L., & Eklund, R. C. (2004). Assisting injured athletes with the return to sport transition. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 14(5), 257–259. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200409000-00001

- Potter, M., Gordon, S., & Hamer, P. (2003). The physiotherapy experience in private practice: The patients’ perspective. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 49(3), 195–202. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60239-7. doi: 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60239-7

- Price, R. J., Hawkins, R. D., Hulse, M. A., & Hodson, A. (2004). The football association medical research programme: An audit of injuries in academy youth football. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(4), 466–471. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.005165

- Ruddock- Hudson, M., O’Halloran, P., & Murphy, G. (2014). The psychological impact of long-term injury on Australian football league players. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 26(4), 377–394. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2014.897269

- Smith, A. M. (1996). Psychological impact of injuries in athletes. Sports Medicine, 22(6), 391–405. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199622060-00006

- Sparkes, A. C. (1998). Athletic identity: An achilles’ heel to the survival of self. Qualitative Health Research, 8(5), 644–664. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800506

- Steffen, K., & Engebretsen, L. (2010). More data needed on injury risk among young elite athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(7), 485–489. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.073833

- von Rosen, P., Frohm, A., Kottorp, A., Fridén, C., & Heijne, A. (2016). Too little sleep and an unhealthy diet could increase the risk of sustaining a new injury in adolescent elite athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, doi: 10.1111/sms.12735

- von Rosen, P., Heijne, A. I., & Frohm, A. (2016). Injuries and associated risk factors among adolescent elite orienteerers: A 26-week prospective registration study. Journal of Athletic Training, 51(4), 321–328. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.5.01

- Westin, M., Alricsson, M., & Werner, S. (2012). Injury profile of competitive alpine skiers: A five-year cohort study. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 20(6), 1175–1181. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-1921-x

- Wiese-bjornstal, D. M., Smith, A. M., Shaffer, S. M., & Morrey, M. A. (1998). An integrated model of response to sport injury: Psychological and sociological dynamics. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 10, 46–69. doi: 10.1080/10413209808406377

Appendix

Semi-structured interview questions for injury perceptions/experience

Opening questions

What sports are you doing?

How long have you been involved in sports?

When was the last time you were injured? That is, had an injury that affected participation in normal training or competition, led to reduced training volume, experience of pain or reduced performance in sports, for at least four weeks.

Specific questions

How did you experience the period before the injury?

Describe, if you were feeling any signs/symptoms of injury before injury?

Describe what you were thinking/feeling when you realized you were injured?

Describe your personal perceptions of yourself when you realized you were injured?

How did you experience the support when you were injured? For example, from the medical staff, friends, classmates, parents, coaches, etc.

Describe if there were any support you were missing?

Looking back on the injury period, what are your thoughts today?

Describe what lessons, if any, you learned from the injury period?

Describe your goals today? Describe your goals before the injury period?

Describe if the injury, in any way, has changed your view on your sports participation?

Describe other consequences of your injury?

Anything else you want to add?