Disclaimer

As a service to authors and researchers we are providing this version of an accepted manuscript (AM). Copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proofs will be undertaken on this manuscript before final publication of the Version of Record (VoR). During production and pre-press, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal relate to these versions also.1.0 INTRODUCTION

Macular edema (ME) after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) repair still represents an important clinical challenge given the lack of consensus among the ophthalmologist on its management after intraocular surgery. The reported incidence of ME after primary RRD repair varies from 6% to 36% of the patients, whose operation was either scleral buckle or vitrectomy[Citation1]. Although several different studies have attempted to elucidate the risk factors associated with ME onset after RRD surgery, the physiopathology remains still poorly understood. Among them, age older than 50 years, presence of pseudophakia or aphakia, macula status, severity of RRD with development of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), intraoperative techniques including retinectomy, having performed an intraoperative 360 degree direct laser retinopexy, and the adoption of silicone oil (SO) have been shown to play a role in ME onset in patients operated for RRD [Citation2–4]; however, the primary factor contributing to the development of ME seems to be subsequent inflammation. This perspective is supported by the detection of elevated levels of various cytokines in the aqueous humor of eyes post-pars plana vitrectomy (PPV), as well as the increase in inflammatory cytokines observed in RRD itself, regardless of the treatment method employed, such as scleral buckling, pneumatic retinopexy, or PPV[Citation5].

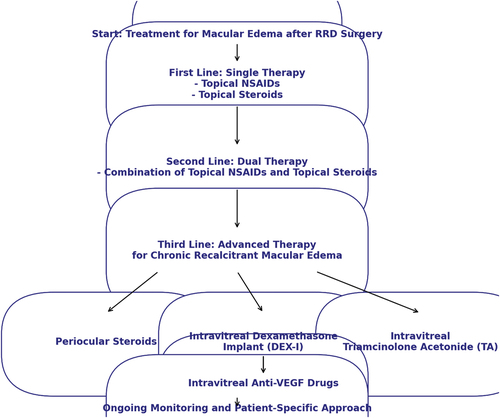

Figure 1: Flowchart showing the recommended therapeutic approach in macular edema after retinal detachment repair

Furthermore, studies reveal also a significantly higher incidence of postsurgical ME in patients with macula-off RRD compared to macula-on RRD. This evidence indicates that macula-off RRD increases the risk of postsurgical ME by 4.3 times, with incidence rates between 26.5% and 83%, regardless of the surgical procedure employed[Citation6].

There is consistent evidence showing that the complexity of the RRD is strictly interconnected with ME onset along with inflammatory predisposition; In fact, the presence of re-detachments is often associated with higher incidence of ME rather than single surgery RRD. In a multivariate analysis on 493 eyes undergoing PPV for RRD, Merad et al. demonstrated that at 12 months the most important contributing factors were low initial visual acuity and presence of PVR grade C [Citation1,Citation7]. In this regard, it has been widely reported that several inflammatory mediators, including interleukin 1, 6 and tumor necrosis factor alfa, are involved in the pathogenesis of PVR, leading to the breakdown of the blood retinal barrier, increased permeability and ME onset [Citation8]. Clinical studies have provided an incidence of ME in severe stages of PVR ranging from 33% to 52% of the patients [Citation9,Citation10]. Other studies on complex RRD cases have also shown the influence of proinflammatory factors, including retinectomy and SO tamponade, for ME development. In fact, SO has been reported to cause ME due to both an inflammatory insult by stimulating macrophage-driven inflammation and mechanical tractional forces from adhesive interactions with the retinal surface [Citation11].

Another pathogenic theory relies on the concept that retinal hydration may contribute on post-RRD cystoid ME (CME) onset, with fluorescein angiography (FA) studies suggesting dynamic fluid movements in the area of leakage [Citation12]; however, further evidence is needed to understand the potential alteration of the pumping mechanisms in RPE cells following RRD and any permanent damage to these cells during RRD.

2.0 TREATMENT OPTIONS

While almost 80% of the ME cases after one single RRD surgery resolve within 6 weeks after conservative treatment, including steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) eye drops, in some cases a chronicization of the edema can occur and more invasive treatment is needed [Citation13].

2.1 NSAID

Topical NSAIDs, which work by blocking cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 and thus prostaglandin production, can be currently considered the first approach for treating postoperative cystoid ME, given their effective ocular tissue penetrance and the non-invasive administration route [Citation14]; however, most of the evidence derives from post-cataract studies. In fact, Sivaprasad et al. conducted a systematic review of various studies on topical NSAIDs for CME after cataract surgery, finding that ketorolac, diclofenac, and their combination with topical corticosteroids were effective for acute CME (less than four months), but not for the recalcitrant forms [Citation15]. Few studies focused specifically on ME after RRD, showing that topical NSAID alone or in combination with topical steroids may be effective in reducing intraocular inflammation and CME onset after RRD surgery [Citation12,Citation16]; in spite of these findings, more randomized, larger-scale and prospective clinical trials are needed to better describe the clinical efficacy of topical NSAID for reducing ME after RRD surgery.

2.2 Steroids

Corticosteroids are effective for treating postoperative cystoid ME by reducing inflammation and tightening the blood-retinal barrier (BRB). Among the various administration routes, periocular and intravitreal injections generally provide more efficacy than systemic and topical steroids; however, intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide, though effective, has a more rapid clearance in vitrectomized eyes [Citation17].

The dexamethasone implant (DEX-I), which releases medication over approximately six months, has been shown to significantly reduce central retinal thickness and to improve visual acuity in both vitrectomized and non-vitrectomized eyes, making it an appropriate treatment for chronic CME [Citation13,Citation18]. Several different studies have demonstrated the long-term efficacy of DEX-I for CME despite recurrence, indicating that repeated intravitreal injections may be necessary [Citation19].

Chatziralli et al. studied 86 eyes post-vitrectomy for RRD and found that 14 eyes with postoperative ME treated with DEX-I achieved a 71% resolution rate with a single injection, showing significant improvement in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) after one year [Citation20].

Thanos et al. observed substantial anatomical improvements and BCVA gains in 17 eyes with ME secondary to RRD and resistant to topical medications after DEX-I treatment, although all required a second injection after three months due to recurrence. Furthermore, early intervention with DEX-I within four months of diagnosis resulted in fewer injections needed during the follow-up [Citation21].

Two large multicenter studies EPISODIC 1 and 2 evaluated the effectiveness of DEX-I in different causes of post-surgical ME and determined the predictive factors. Despite significant improvements in functional and anatomical responses at six and twelve months after DEX-I injection, the EPISODIC 1 and 2 studies reported poorer outcomes in the postoperative ME group due to RRD compared to the post cataract surgery group [Citation22,Citation23].

A 2-year, large, multicenter, randomized, clinical trial investigated the clinical efficacy of DEX-I in 140 patients with complex RRD with PVR grade C. Although after 2 years similar anatomic success was reported between the DEX-I and placebo group, after 6 months it was shown a reduced incidence of ME in the intervention group as compared with controls (42.7% vs 67.2%,p=0.004), showing the beneficial effect of DEX-I in preventing ME onset [Citation24].

Additionally, large multicenter studies have confirmed DEX-I efficacy and safety for ME secondary to RRD, with common complications including cataract progression in 32.5% of phakic eyes and increased intraocular pressure (IOP) in 26.5% of eyes, which was medically controlled in 90% of cases [Citation25]. These findings underscore the importance of early and repeated DEX-I injections for optimal long-term management of CME; nonetheless, the reported higher risk of developing increased IOP should not be neglected in patients undergoing intravitreal injections with steroids.

To date, only one case report has described the clinical efficacy of the long-acting 0.19 mg fluocinolone acetonide implant in a patient with refractory ME after RRD surgery. In this patient, which did not respond to previous treatment with intravitreal triamcinolone and DEX-I, fluocinolone acetonide implant kept the retina dry for the 13-month follow up period [Citation26].

3.0 EXPERT OPINION

Cystoid ME is a relatively common complication following RRD repair surgery, characterized by the accumulation of intraretinal fluid and reduced visual acuity due to the breakdown of BRB caused by surgical trauma, inflammation, and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators. Hence, given this putative pathogenic background, most of treatment strategies primarily focus on reducing inflammation.

The first-line approach involves topical NSAIDs, such as ketorolac and diclofenac, alone or in combination with topical corticosteroids. Combination of drops can be considered as second line strategy. Differently, for recalcitrant cases that do not respond to this initial treatment, periocular or intravitreal corticosteroids, and in particular DEX-I, are recommended as a third-line treatment option. The DEX-I, which offers a sustained release of medication over several months, has proven particularly beneficial for chronic CME and shows similar efficacy in both vitrectomized and non-vitrectomized eyes.

Given the multifactorial nature of CME, a tailored, patient-specific approach with ongoing monitoring is essential to achieve the best outcomes. The personal preferences of the authors are combination of steroid and NSAIDs for a period of minimum 6 weeks with a gradual reduction if complete resolution was achieved. For refractory cases, the escalation to periocular or intravitreal corticosteroids is recommended. In complex cases such as PVR-related RRD, patients who have undergone retinectomies and in SO-filled eyes, our preference is DEX-I when topical therapy proves ineffective. This preference is supported by a randomized clinical trial demonstrating its clinical efficacy and safety profile. Furthermore, several studies referred DEX-I long-term efficacy in chronic ME, with substantial anatomical and visual improvements, even though repeated injections may be necessary.

It is crucial however to inform patients that complete resolution may not be achievable in complex cases, and further research is needed to optimize treatment strategies.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Table 1: Recommended treatment options with level of evidence and grade of recommendations in patients with macular edema following to retinal detachment surgery (OCEBM Levels of Evidence)

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Merad M, Verite F, Baudin F, et al. Cystoid Macular Edema after Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Repair with Pars Plana Vitrectomy: Rate, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 21;11(16). 10.3390/jcm11164914 4914

- Bonnet M. Prognosis of cystoid macular edema after retinal detachment repair. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1986;224(1):13–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02144125

- Wang JC, Ryan EH, Ryan C, et al. Factors Associated with the Use of 360-Degree Laser Retinopexy during Primary Vitrectomy with or without Scleral Buckle for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment and Impact on Surgical Outcomes (Pro Study Report Number 4). Retina. 2020 Nov;40(11):2070–2076.

- Shah YS, Abidi M, Ahmed I, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Cystoid Macular Edema among Patients Undergoing Primary Repair of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. Ophthalmol Retina. 2024 May;8(5):456–464.

- Gu R, Zhou M, Jiang C, et al. Elevated concentration of cytokines in aqueous in post-vitrectomy eyes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016 Mar;44(2):128–134. 10.1111/ceo.12638

- Gebler M, Pfeiffer S, Callizo J, et al. Incidence and risk factors for macular oedema after primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment surgery: a prospective single-centre study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022 May;100(3):295–301. 10.1111/aos.14940

- Lai TT, Huang JS, Yeh PT Incidence and risk factors for cystoid macular edema following scleral buckling. Eye (Lond). 2017 Apr;31(4):566–571.10.1038/eye.2016.264

- Kon CH, Occleston NL, Aylward GW, et al. Expression of vitreous cytokines in proliferative vitreoretinopathy: a prospective study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999 Mar;40(3):705–712.

- Bonnet M. Macular changes and fluorescein angiographic findings after repair of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Retina. 1994;14(5):404–410. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199414050-00003

- Stopa M, Kociecki J. Anatomy and function of the macula in patients after retinectomy for retinal detachment complicated by proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011 Jul-Aug;21(4):468–72.

- Kontou EP, Karakosta C, Kounas K, et al. Macular Edema Following Silicone Oil Tamponade for Retinal Detachment: A Literature Review. Cureus. 2023 Dec;15(12):e51233.10.7759/cureus.51233

- Alam MR, Arcinue CA, Mendoza NB, et al. Recalcitrant Cystoid Macular Edema after Pars Plana Vitrectomy. Retina. 2016 Jul;36(7):1244–1251.10.1097/IAE.0000000000000892

- Souissi S, Allou V, Trucchi L, et al. Macular oedema secondary to rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair: risk factors for resistance to first-line therapy and long-term response to dexamethasone intravitreal implant. Eye (Lond). 2024 Apr;38(6):1155–1161.10.1038/s41433-023-02852-x

- Flach AJ, Dolan BJ, Irvine AR Effectiveness of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution for chronic aphakic and pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987 Apr 15;103(4):479–486. 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)74268-0

- Sivaprasad S, Bunce C, Crosby-Nwaobi R Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents for treating cystoid macular oedema following cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 15(2):CD004239. 10.1002/14651858.CD004239.pub3

- Yasuda K, Motohashi R, Kotake O, et al. Comparative Effects of Topical Diclofenac and Betamethasone on Inflammation After Vitrectomy and Cataract Surgery in Various Vitreoretinal Diseases. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Dec;32(10):677–684. 10.1089/jop.2016.0099

- Chin HS, Park TS, Moon YS, et al. Difference in clearance of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide between vitrectomized and nonvitrectomized eyes. Retina. 2005 Jul-Aug;25(5):556–560.10.1097/00006982-200507000-00002

- Pole C, Chehaibou I, Govetto A, et al. Macular edema after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair: risk factors, OCT analysis, and treatment responses. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2021 Jan 25;7(1):9. 10.1186/s40942-020-00254-9

- Zheng A, Chin EK, Almeida DR, et al. Combined Vitrectomy and Intravitreal Dexamethasone (Ozurdex) Sustained-Release Implant. Retina. 2016 Nov;36(11):2087–2092.

- Chatziralli I, Theodossiadis G, Dimitriou E, et al. Macular Edema after Successful Pars Plana Vitrectomy for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment: Factors Affecting Edema Development and Considerations for Treatment. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021 Jan 2;29(1):187–192. 10.1080/09273948.2019.1652330

- Thanos A, Todorich B, Yonekawa Y, et al. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for the treatment of recalcitrant macular edema after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair. Retina. 2018 Jun;38(6):1084–1090. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001720

- Bellocq D, Pierre-Kahn V, Matonti F, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dexamethasone implants for postsurgical macular oedema including Irvine-Gass syndrome: the EPISODIC-2 study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017 Mar;101(3):333–341.

- Bellocq D, Korobelnik JF, Burillon C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dexamethasone implants for post-surgical macular oedema including Irvine-Gass syndrome: the EPISODIC study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jul;99(7):979–983.10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306159

- Banerjee PJ, Quartilho A, Bunce C, et al. Slow-release dexamethasone in proliferative vitreoretinopathy: a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2017 Jun;124(6):757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.01.021

- Khurana RN, Porco TC Efficacy and Safety of Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant for Persistent Uveitic Cystoid Macular Edema. Retina. 2015 Aug;35(8):1640–1646.10.1097/IAE.0000000000000515

- Alfaqawi F, Sarmad A, Ayesh K, et al. Intravitreal Fluocinolone Acetonide (ILUVIEN) Implant for the Treatment of Refractory Cystoid Macular Oedema After Retinal Detachment Repair. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2018 Jun;48(3):155–157. 10.4274/tjo.34966