1. Introduction

Gray-zone lymphoma (GZL), or B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), is a diagnosis that spans the biologic spectrum between DLBCL, namely primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL), and CHL, particularly nodular sclerosis (NS) subtype, encompassing tumors that show morphologic and immunophenotypic overlap with both entities [Citation1]. It typically involves the mediastinum of young males (mediastinal gray-zone lymphoma, MGZL), and is associated with a more aggressive clinical course than CHL or PMBL [Citation1–Citation4]. However, GZL lacks precise diagnostic criteria, thus posing a considerable challenge in terms of pathologic diagnosis and treatment. We discuss the current difficulties and diagnostic considerations encountered in the histopathological evaluation of this rare lymphoma.

2. Background

MGZL was initially recognized as a possible distinct clinicopathological entity at a workshop on Hodgkin disease and related entities in 1998 with the identification of five cases that showed transitional features between DLBCL and CHL and involved the mediastinum [Citation5]. Following this, a series of 21 cases from the NIH describing morphologic and immunophenotypic attributes was published in 2005 [Citation6] and the category of B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with features intermediate between DLBCL and CHL was recognized as a provisional category in the 2008 WHO classification [Citation7]. Currently, composite and sequential cases of CHL/PMBL are viewed as biologically related; however, these are not strictly accepted as GZL [Citation1]. Furthermore, non-mediastinal presentations of gray-zone lymphoma (non-MGZL) are recognized, occurring more frequently in older patients [Citation8].

3. PMBL and CHL: at the extremes of a biologic continuum

Although established entities with well-delineated pathological features, certain commonalities and associations between CHL and PMBL are well recognized. As well as overlap on morphologic and immunophenotypic grounds in the form of GZL, both entities have been encountered as a composite lymphoma or as sequential lymphomas in the same patient [Citation6]. Clinically, both tumors usually involve the anterior mediastinum or supraclavicular lymph nodes [Citation1,Citation9]. Seminal gene expression profiling studies performed by Rosenwald [Citation10] and Savage [Citation11] have shown that PMBL is distinct from other types of DLBCL and related to CHL. Furthermore, both PMBL and CHL have been shown to share similar genetic aberrations including amplification of 9p24.1 (JAK2/CD274/PDCD1LG2), rearrangements of CIITA at 16p13.13 and gains at the REL locus at 2p.16.1. Other mechanisms of NFκB and JAK-STAT pathway dysregulation found in both PMBL and CHL include point mutations in TNFAIP3 and SOCS1 genes [Citation9,Citation12].

The morphology and immunophenotype of CHL-NS and PMBL are defined and distinct. CHL-NS is characterized morphologically by a nodular growth pattern with intervening bands of fibrosis and lacunar type Reed-Sternberg cells that express CD30 and CD15, and show negative or at most weak, variable expression of B-cell markers such as CD20 or CD79a [1,Citation5,Citation12]. In contrast, PMBL is characterized by sheets of atypical cells with a diffuse growth pattern and surrounded by fine compartmentalizing sclerosis. The cells have large nuclei, often have clear cytoplasm and show a mature B-cell phenotype with expression of CD20, CD79a and other B-cell transcription factors such as OCT2 and BOB1. CD23 is often positive and CD30 is often weakly expressed [Citation1,Citation13].

4. Features of GZL

4.1. Morphology and immunophenotype

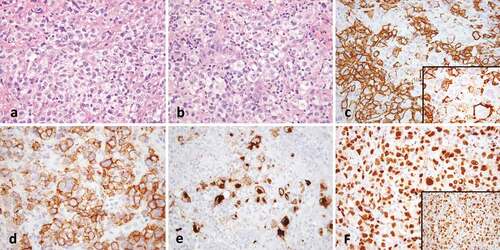

GZL is characterized by varying degrees of discordance between morphology and immunophenotype that make the classification as either CHL or PMBL difficult. Tumor cells are usually abundant [Citation1,Citation2] and although traditionally categorized as ‘PMBL-like’ or ‘CHL-like’, the cytomorphological spectrum is usually transitional between that typically seen in PMBL or CHL. The cells may have a centroblastic or immunoblastic appearance reminiscent of PMBL; however, can be larger with more pleomorphism [Citation2,Citation6,Citation8]. Lacunar cells or Reed-Sternberg (RS)-like cells may be present in variable numbers and more intermediate in size, displaying less frequent prominent eosinophilic nucleoli than typical RS-variants [Citation2,Citation8]. The inflammatory background usually associated with CHL [Citation2,Citation6,Citation8] is often less apparent, with fewer eosinophils and plasma cells [Citation8]. Necrosis is variably present but may be scarce or absent [Citation1,Citation6,Citation8]. Tumor architecture is usually diffuse, but occasionally a nodular growth pattern and coarse fibrosis may be present [Citation2,Citation8]. Expression of PAX-5, BOB.1, and OCT-2 is variable among GZL [Citation6], but in general, there is an expression of at least one B-cell marker in a panel of CD20, CD79a, and PAX5 [Citation2]. Cases rich in centroblastic-appearing cells may lack or only partially express certain B-cell markers (e.g. CD20) but show positivity for CD30 or moderate to strong CD15 [Citation8,Citation13]. Tumors with an abundance of RS-like cells may have a strong expression of multiple B-cell markers/transcription factors and CD45, and lack CD15 expression [Citation6,Citation8,Citation13]. CD30 is usually expressed, although it may be weak [Citation6,Citation8] and expression of CD23 [Citation8] may also be present. MAL may also be positive irrespective of histology [Citation6,Citation8]. EBER positivity has occasionally been reported [Citation2,Citation6,Citation8], though interpretation is controversial (see ).

Figure 1. Gray-zone lymphoma. (a) There is a diffuse infiltrate of atypical lymphoid cells with clear cytoplasm (40x). (b) Occasional cells have Hodgkin-like features (40x). (c) CD20 shows strong staining with some variability (40x, inset 100x). (d) CD30 is strongly positive and (e) CD15 shows golgi and membranous staining in a subset of Hodgkin-like cells (both 20x). (f) OCT2 (40x) and PAX-5 (inset, 40x) are strongly positive.

4.2. Molecular features

Methylation studies have demonstrated a close relationship between GZL, CHL, and PMBL as tumors that are epigenetically different from DLBCL. Importantly, it has also been shown that GZL has a distinct epigenetic signature that is intermediate between CHL and PMBL [Citation14] supporting the classification of GZL as a separate entity. As in PMBL and CHL, alterations have been reported at the JAK2/CD274/PDCD1LG2 locus at 9p24 and the CIITA locus at 16p13.13, including gains, amplifications, and rearrangements [Citation8,Citation14]. Gains at the REL locus at 2p.16.1 have been described in 33% of cases and gains at the MYC locus at 8q24 in 27%[Citation14].

5. Differential diagnosis of GZL

The difficulties that arise in the classification of these overlapping neoplasms relate to the level of morphologic and immunophenotypic ambiguity required to make a diagnosis of GZL rather than CHL or PMBL.

Assessing the threshold of B-cell transcription factor/marker expression that is acceptable in a tumor that morphologically resembles CHL is often challenging. With modern antigen-retrieval techniques, it is not uncommon to see CD20 positivity in CHL-NS with otherwise typical morphology and the expression of CD20 in this setting is insufficient to diagnose GZL [Citation1,Citation2]. The degree of CD20 positivity observed is usually variable in cases of CHL, and in general, the presence of strong and diffuse positivity should warrant evaluation of other B-cell markers or transcription factors [Citation13,Citation15]. Even so, CD79a positivity is infrequently present in CHL and weak partial expression of transcription factors BOB1 and OCT2 may occur in up to 33%[Citation16]. Similarly, expression of CD30 is not confined to CHL and is commonly seen in up to 69% of PMBL, although the level of expression is variable [Citation17].

In a retrospective study by Pilichowska et al. [Citation2], only 38% of GZL cases were confirmed following consensus pathology review. In this, and a second study by Sarkozy et al. [Citation8], GZL cases were most often reclassified to CHL-NS following review. One particular pitfall is the morphologic variant of CHL-NS known as ‘grade 2’. This variant is characterized by a tumor cell-rich infiltrate with necrosis and the typical inflammatory background of CHL, but the stroma also contains zones of fibrosis where the inflammatory background is minimal. CHL-NS grade 2 may be interpreted as GZL due to the confluent growth of the tumor cells in conjunction with the expression of CD20, particularly in areas where eosinophils and neutrophils are inconspicuous [Citation2]. Recognition of the inflammatory component and the typical morphology of the tumor cells should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of CHL over GZL. In all cases, careful assessment of morphology is of critical importance; however, it should also be appreciated that minor morphologic variation such as occasional RS cells in PMBL or aggregates of mononuclear RS cells in CHL may be observed and by themselves are not indicative of GZL [Citation1,Citation13].

EBV positivity in GZL has been described and is noted in the WHO classification as a rare occurrence [Citation1]. In an early study by Traverse-Glehen 2/7 cases with a CHL morphology were EBV positive [Citation6] and more recent studies have shown variable rates of positivity from 4% to 24% [Citation2,Citation8]. However, with increasing appreciation of the spectrum of EBV-related B-cell proliferations, it is recognized that they may overlap considerably with CHL and show a similar morphologic appearance and immunophenotype, including the presence of RS-cells and upregulation of CD30 [Citation18]. The recent WHO classification recognizes that EBV-positive DLBCL can occur in younger patients [Citation1], and cases that involve the mediastinum with a ‘GZL-like’ pattern are described [Citation18]. EBV is usually absent in PMBL and is less common in CHL-NS, the subtype of CHL that overlaps with GZL, than in other subtypes of CHL [Citation1]. One perspective is that at the current time, EBV-positive lymphomas with gray-zone features are best classified as part of the spectrum of EBV-positive DLBCL in order to facilitate clearer definition of the GZL category as an entity outside of an EBV-driven process; however, these cases remain challenging and diagnosis is still subject to considerable variability.

Finally, the diagnosis of GZL in a post-therapy setting or on a needle core biopsy requires careful consideration and is often not advisable, as therapy may alter B-cell marker expression, and limited sampling as with needle core biopsy may make an adequate assessment of morphology difficult.

6. Conclusion

Histopathological diagnosis and classification of GZL remains challenging and subject to interobserver variability; however, recognition and diagnosis is crucial for the initiation of optimal treatment. Currently, morphologic and immunophenotypic evaluation in conjunction with an awareness of other differential diagnostic considerations is key to rendering a final diagnosis. As our knowledge expands, the future development of consensus guidelines may aid in more precise classification of this entity.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Revised 4th Edition ed. Lyon: IARC; 2017.

- Pilichowska M, Pittaluga S, Ferry JA, et al. Clinicopathologic consensus study of gray zone lymphoma with features intermediate between DLBCL and classical HL. Blood Adv. 2017;1:2600–2609.

- Dunleavy K, Wilson WH. Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and mediastinal gray zone lymphoma: do they require a unique therapeutic approach? Blood. 2015;125:33–39.

- Wilson WH, Pittaluga S, Nicolae A, et al. A prospective study of mediastinal gray-zone lymphoma. Blood. 2014;124:1563–1569.

- Rudiger T, Jaffe ES, Delsol G, et al. Workshop report on Hodgkin’s disease and related diseases (‘grey zone’ lymphoma). Ann Oncol. 1998;9(Suppl 5):S31–38.

- Traverse-Glehen A, Pittaluga S, Gaulard P, et al. Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma: the missing link between classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma and mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1411–1421.

- Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, et al. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019–5032.

- Sarkozy C, Copie-Bergman C, Damotte D, et al. Gray-zone lymphoma between Chl and large B-cell lymphoma: A histopathologic series from the LYSA. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:341–351.

- Steidl C, Gascoyne RD. The molecular pathogenesis of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:2659–2669.

- Rosenwald A, Wright G, Leroy K, et al. Molecular diagnosis of primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma identifies a clinically favorable subgroup of diffuse large B cell lymphoma related to Hodgkin lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2003;198:851–862.

- Savage KJ, Monti S, Kutok JL, et al. The molecular signature of mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma differs from that of other diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and shares features with classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2003;102:3871–3879.

- Mathas S, Hartmann S, Kuppers R. Hodgkin lymphoma: pathology and biology. Semin Hematol. 2016;53:139–147.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, de Jong D, de Mascarel A, et al. Gray zones around diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Conclusions based on the workshop of the XIV meeting of the European association for hematopathology and the society of hematopathology in bordeaux, France. J Hematop. 2009;2:211–236.

- Eberle FC, Rodriguez-Canales J, Wei L, et al. Methylation profiling of mediastinal gray zone lymphoma reveals a distinctive signature with elements shared by classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2011;96:558–566.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, Fend F. Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma. Haematologica. 2011;96:496–499.

- Browne P, Petrosyan K, Hernandez A, et al. The B-cell transcription factors BSAP, Oct-2, and BOB.1 and the pan-B-cell markers CD20, CD22, and CD79a are useful in the differential diagnosis of classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120::767–777.

- Higgins JP, Warnke RA. CD30 expression is common in mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112:241–247.

- Nicolae A, Pittaluga S, Abdullah S, et al. EBV-positive large B-cell lymphomas in young patients: a nodal lymphoma with evidence for a tolerogenic immune environment. Blood. 2015;126:863–872.