ABSTRACT

Introduction: The patent expiration of some biologics used in chronic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has led to the development of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies. The tailored regulatory approval route for biosimilar development ensures that approved biosimilars show similarity to their originators in terms of efficacy and safety, and avoids unnecessary repetition of clinical trials carried out with the originator product. However, some patients may still have concerns about using biosimilars and it is the responsibility of healthcare professionals (HCPs) to alleviate these concerns.

Areas covered: This review highlights clinical and real-world evidence supporting efficacy and safety of biosimilars in patients with IBD. Moreover, based on international surveys, potential patient concerns are highlighted, along with possible actions HCPs can take to address these concerns.

Expert commentary: The rising use of biosimilars in IBD is expected to have a positive impact on the availability of biologics and healthcare costs. Several biosimilars have been approved for use and more are likely to come to the market in the future; however, transitioning patients to biosimilars could pose an unexpected challenge without the help and support of HCPs.

1. Introduction

The increasing use of high-cost biologics across many areas of chronic disease management is having a significant impact on healthcare expenditure [Citation1,Citation2]. Biologics are being used earlier in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [Citation3], which raises concerns that if current trends of rising biologics expenditure continue, patient access may be restricted [Citation1]. Loss of patent protection of a number of biologics coupled with advances in technological innovations and biomanufacturing lead to a reduction in the time and cost to develop new biologic drug products [Citation4]. The development of high-quality biosimilars can offer a cheaper, yet equally effective alternative [Citation1,Citation5]. In 2004, a dedicated route for the approval of biosimilars was introduced in the European Union (EU) and over the years, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has issued scientific guidelines to aid developers in conforming to the strict regulatory requirements for approving biosimilars [Citation5]. Biosimilar use and development may enable wider access and better value to be obtained from the money spent on healthcare services [Citation6] for conditions with high ‘socioeconomic burden,’ such as IBD [Citation7].

In patients with chronic conditions like IBD, clinical studies demonstrate that biosimilars have long-term efficacy and safety profiles [Citation8–Citation10] and that they are non-inferior to the originator biologic [Citation11]. However, some patients are not familiar with biosimilars and some have concerns about the efficacy or safety of these agents [Citation12]. This suggests that healthcare professionals (HCPs) need to be proactive in providing more information to patients to alleviate these concerns.

This review explores biosimilars from the point of view of a patient with IBD, based on study results in mainly European territory. Patients may have concerns regardless of whether they are starting treatment with a biosimilar or switching from their originator product to a biosimilar. We also discuss how HCPs can help alleviate patients’ concerns regarding biosimilars by providing up-to-date, practical evidence-based guidance on biosimilar treatment to patients.

2. Development of biosimilars and potential cost savings

The EMA states that ‘a biosimilar is a biologic medicinal product that contains a version of the active substance of an already authorized reference medicinal product’ and must be similar to the originator product in ‘quality characteristics, biological activity, safety, and efficacy’ [Citation13]. On the same line, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that ‘a biosimilar is a biological product that is highly similar to and has no clinically meaningful differences from an existing FDA-approved reference product’ [Citation14] and World Health Organization states that ‘a biotherapeutic product that is similar in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy to an already licensed reference biotherapeutic product’ [Citation15]. Biosimilar approval builds on the existing scientific knowledge on efficacy and safety of the originator product gained during its clinical use; therefore, fewer clinical data are required for the biosimilar but each biosimilar does undergo comprehensive comparability testing with its originator product [Citation5]. Comparability, testing is required to prove similarity between a biosimilar and originator product and to show that any observed differences are not clinically meaningful [Citation16]. This tailored biosimilar development program which builds on existing scientific knowledge gained from the originator product avoids unnecessary repetition of non-clinical and clinical studies and this can be less costly for healthcare systems [Citation5]. A report in 2016 estimated that the emergence of infliximab biosimilars could significantly reduce healthcare spending [Citation17]. Therefore, the growing use of biosimilars is expected to have a significant positive impact on healthcare costs.

IBD, comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is associated with high socioeconomic burden (direct healthcare costs of €4.6–5.6 billion annually in Europe) [Citation18] and due to its early-onset and chronic nature is associated with productivity losses including sick leave and unpaid work [Citation19]. In a report published in 2013, it was estimated that there were 2.5–3 million people in Europe with IBD [Citation18], and a more recent report published in 2017 indicated that the prevalence of IBD exceeded 0.3% in westernized countries [Citation20]. Healthcare costs associated with IBD are mainly driven by medication costs, particularly with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) inhibitors [Citation19]. The relatively high cost of TNFα inhibitors and the patent expiration of these biologics has triggered a rise in the use of biosimilars for IBD [Citation16], with the first biosimilar for infliximab (CT-P13) approved by the EMA Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use in 2013 [Citation21]. Since then, several infliximab biosimilars have been approved and, as of August 2018, many biosimilars were approved for use in Europe (). However, despite biosimilars being a potentially more affordable and readily available therapy for patients with IBD [Citation5], patients still have concerns with regard to the safety and efficacy of these agents [Citation12]. To adequately address patients’ concerns, HCPs must be knowledgeable and confident in explaining what biosimilars are, including how a biosimilar might be beneficial for the patient (for example, increased access to treatment and more treatment options [Citation22]) and be ready to explain patient-accessible clinical data.

Table 1. Biosimilars approved for use in Europe (as of August 2018).*

3. Clinical evidence supporting similarity of biosimilars to originator biologics

The EMA recognizes that, if a biosimilar is highly similar to the originator product in terms of efficacy and safety in one therapeutic indication, then these data may be extrapolated to other indications approved for the originator product, if sufficiently supported by scientific evidence [Citation5]. For most biosimilars assessed in clinical trials, efficacy compared with the originator product has been evaluated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis as clinical experience with biosimilars is greatest in this population, and because this population is considered a sufficiently sensitive model for establishing equivalence of efficacy between an anti-TNF biosimilar and its originator product [Citation16]. Consequently, immunogenicity of biological medicines are always monitored post-marketing by regulatory authorities once the product is on the market [Citation5].

Recent studies investigating the safety and efficacy of infliximab biosimilars in IBD indicate similar efficacy and safety of biosimilars compared with originator biologics (). The NOR-SWITCH trial assessed the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) in adult patients with chronic conditions, including IBD, and the results showed non-inferiority of CT-P13 in disease worsening (primary endpoint) in patients switching from infliximab originator to CT-P13, when compared with continued treatment with the originator biologic; although the study was not powered to show non-inferiority between disease types. In addition, there also appeared to be no differences in the safety and immunogenicity between the two treatment groups [Citation11]. Assessment of long-term efficacy and safety of CT-P13 was examined in ≥52-week studies in patients with IBD [Citation8–Citation10] where results showed that, in a real-life cohort of patients with IBD, switching from infliximab originator to CT-P13 had no significant impact on clinical outcomes, including disease activity, safety, drug survival, and pharmacokinetics [Citation10], and no occurrence of unexpected safety issues [Citation9]. In one of these studies, 51% of patients with IBD achieved clinical response at the end of the 54-week treatment period following continuous treatment with CT-P13 [Citation8]. Moreover, a Phase 4 non-inferiority study showed that switching to CT-P13 in patients with IBD in clinical remission was efficacious and well tolerated, with no noted differences in clinical, biochemical, and pharmacokinetic outcomes [Citation31]. However, patients with IBD might still consider currently available biosimilars to be ‘different’ to originator biologics; therefore, it is important that HCPs understand patients’ attitudes toward biosimilars and have knowledge of the appropriate clinical data to address these concerns.

Table 2. Clinical evidence supporting efficacy/effectiveness and safety of infliximab biosimilar in inflammatory bowel disease.

4. Biosimilars: patient’s view and HCPs’ knowledge

Despite clinical evidence that biosimilars approved through the EMA can be used as safely and effectively in all their approved indications as other biologics [Citation5], misconceptions surrounding the efficacy and safety of biosimilars still exist amongst patients and in the general population [Citation12,Citation37]. An international cross-sectional survey assessed the awareness of biosimilars amongst patients (including those with breast cancer, colorectal cancer, IBD, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, psoriasis, or rheumatoid arthritis), diagnosed advocacy (patients with the aforementioned diseases who participated in patient support groups), caregivers (individuals involved in decisions or dialog about medication or therapy options for a loved one with these conditions), and the general population in the United States (US) and EU in 2014 [Citation37]. Of the 3,198 individuals who responded, awareness of biosimilars was significantly higher in diagnosed and diagnosed advocacy versus the general population in the EU. Furthermore, 20–30% of respondents who were involved in patient advocacy groups had at least a general expression of biosimilars compared with only 6% of the general population [Citation37]. There were knowledge gaps relating to the efficacy and safety of biosimilars amongst respondents, as well as concerns relating to accessibility with only 40–41% of patients in the EU considering biosimilars an affordable treatment option and/or one that would provide effective care at a reasonable cost [Citation37]. Similar concerns were also mirrored in a survey conducted by the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Association (EFCCA) between November 2014 and October 2015 [Citation12]. Of the 1,181 patients with IBD who participated in the EFCCA survey, only 38% had heard of biosimilars and >40% of patients were concerned about the efficacy and/or safety profile of biosimilars [Citation12]. In addition, only 25% of patients had no concerns about biosimilars and only 31% would be fully confident about biosimilars, even if they were prescribed and explained by a treating physician [Citation12]. Clearly, a significant proportion of patients with IBD are not familiar with the concept of biosimilars, suggesting that more needs to be done by HCPs to address these concerns. In addition, evidence suggests that not all HCPs are yet confident in the use of biosimilars in clinical practice. Indeed, a European Crohn’s Colitis Organisation (ECCO) survey conducted in 2015 among IBD specialists indicated that, out of 118 respondents, 19.5% of respondents still had little or no confidence in the use of biosimilars and only 44% felt that biosimilars can be used interchangeably with the originator biologic [Citation38]. This was despite an improvement in confidence in biosimilars in 2015 as compared with the ECCO survey in 2013 [Citation39], with almost double the proportion of respondents in favor of increasing the use of biosimilars in 2015 versus 2013 [Citation38]. Moreover, a one-time web-based survey to compare HCPs’ attitudes toward utilization of infliximab biosimilar and insulin glargine biosimilar in hospitals in the United Kingdom (UK) found that of the 234 respondents (professionals associated with dermatology [26%], rheumatology [26%], gastroenterology [23%], and diabetology [25%]), 77% considered biosimilars ‘extremely’ or ‘very important’ to save costs for the National Health Service (NHS) [Citation40]. Gastroenterologists had the highest utilization of infliximab biosimilars (14% in 2015 rising to 62% in 2016); HCPs had greater concerns about switching patients to biosimilars compared with treating biological-naïve patients with these agents [Citation40]. From this study, the authors concluded that UK HCPs have a good understanding of biosimilars, but there is significant variation between specialties [Citation40].

5. How can HCPs address patients’ concerns?

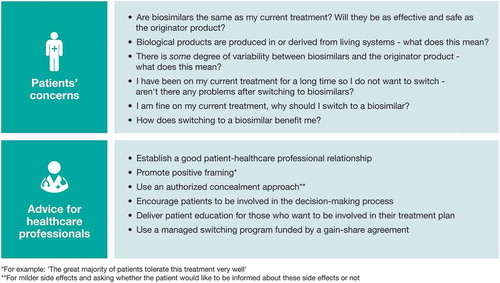

It is the responsibility of HCPs to ensure that patients receive sufficient information about biosimilars to reduce concerns (). The EFCCA survey conducted between 2014 and 2015 indicated that 20% of patients would be worried about starting treatment with biosimilars and would probably stop treatment at the ‘first doubt, or alternative event’ [Citation12]. Respondents also appeared to have more trust in their treating physicians than in pharmacists or regulatory agencies which highlights the importance of good patient-HCP relationships [Citation12] and may help mitigate the ‘nocebo effect.’ The ‘nocebo effect’ occurs when the expectation of side effects leads to those symptoms being realized [Citation41] and might occur when switching patients to generic treatment from branded therapies [Citation42]. Consequently, generic medications are often associated with increased reporting of side effects by patients and treatment non-adherence [Citation42]. This ‘nocebo effect’ may occur not only in patients switching to a generic from a branded product, but also in patients switching from originator biologics to biosimilars [Citation43]. Therefore, HCPs can help minimize the ‘nocebo effect’ with biosimilars through positive framing. The benefits of positive framing have been shown in study participants receiving the opioid analgesic remifentanil where positive treatment expectancy substantially enhanced the analgesic benefit of remifentanil [Citation44]. This suggests that a patient’s expectation of a drug’s effect influences its therapeutic efficacy [Citation44] and positive framing by HCPs may also aid treatment outcomes for patients who take biosimilars.

Figure 1. Patients’ potential concerns regarding biosimilars and what healthcare professionals can do to address these concerns.

The effects of a structured communication strategy with opt-out option in non-mandatory transitioning from etanercept originator to etanercept biosimilar (SB4) on drug survival and effectiveness were investigated in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease (BIO-SPAN study) [Citation45]. In this study, adult patients treated with etanercept originator were firstly informed by letter about the option of switching to SB4, and at the time of planned prescription refill were contacted by a pharmacy technician to ask whether they would agree to transition to SB4 [Citation45]. If patients were in agreement, they were prescribed SB4; if they were not in agreement, they were contacted by their treating rheumatologist to discuss the transition [Citation45]. Of the 642 patients who were contacted in 2016, 99% of patients agreed to transition to SB4 (of whom 625 were included in the BIO-SPAN study) with an acceptable persistence rate of 90% following 6 months of treatment [Citation45]. The persistence rates of patients continuing to take SB4 was comparable with that of a historical cohort of patients who received etanercept originator treatment in 2014 (90% vs 92%); although, the transition cohort had a significantly higher relative risk of discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio 1.57, 95% confidence interval 1.05–2.36), differences in the persistence rate and disease activity were not considered clinically relevant [Citation45]. It was hypothesized that the higher acceptance rates of SB4 in the BIO-SPAN study versus the previous BIO-SWITCH study [Citation45,Citation46] may be due to the structured communication strategy that was implemented before patients transitioned to SB4. This may have positively influenced patients’ expectations of transitioning to a biosimilar whilst reducing the possibility of the ‘nocebo effect’ [Citation45]. Results from the EFCCA survey conducted between 2014 and 2015 indicated that 44% of patients would want to know that they were receiving a biosimilar and not an originator biologic. Similarly, 21% of patients would require all the necessary information about the biosimilar before it was administered, as well as written information about the product that could be used for future care [Citation12]. Taken together, these data indicate that traceability is also important for patients [Citation47] and a structured communication strategy might positively influence patients’ expectations on transitioning to a biosimilar [Citation45].

HCPs can also encourage patients to become engaged in the decision-making process. For patients who want to be involved in this process, patient education and shared decision-making optimizes the chance that the chosen therapy matches a patient’s personal preference and, therefore, patients are more likely to be confident in their treatment plan and adhere to their chosen therapy [Citation48]. Although not all patients prefer to be involved in the shared decision-making process, and some decisions cannot be made collaboratively between patients and HCPs (e.g. it should be considered whether standard of care has already been established [Citation48]), patient education driven by HCPs may still be critical in switching patients from originator biologics to biosimilars. Between April 2015 and March 2016, a managed switching program was trialed in the UK for switching patients with IBD from infliximab originator to its biosimilar (CT-P13), funded via a gain-share agreement [Citation49]. This managed switching program was developed to support patients through the transition process and included a risk-management plan in the hope that any problems with switching to CT-P13 would be detected at the earliest opportunity [Citation49]. The managed switching program was developed with input from all key stakeholders, including gastroenterologists, pharmacists, an IBD nursing team, and a local IBD patient panel [Citation49]. In this study, prior to switching to CT-P13, patients were given an information sheet on biosimilars and the opportunity to ask questions to HCPs about biosimilars. Additionally, the IBD patient panel were reassured that patients would receive increased monitoring as part of the managed switching program [Citation49]. In the 143 patients (118 CD, 23 UC, and 2 IBD unclassified) who switched to CT-P13, there was no significant difference in drug persistence, side effects, incidence of adverse reactions, disease activity, or blood test results compared with those who received the infliximab originator [Citation49]. In addition, using the managed switching program reduced drug acquisition costs by £40,000–60,000 per month for this particular hospital in the UK [Citation49]. This study showed that using this managed switching program in patients with IBD not only showed no significant difference in patient-reported efficacy and safety outcomes between infliximab originator and CT-P13, but also delivered significant cost savings [Citation49]. This gain-share agreement also invested into the nurse-led IBD biologic service, leading to improvements in patient quality-of-care and safety, recruitment into research studies, and significant cost savings [Citation49]. It is possible that the savings associated with biosimilars could also be invested in IBD patient services [Citation49]. In support of this, the 2016 national clinical audit of biologic therapies for UK IBD published by the Royal College of Physicians found that annual treatment costs could be reduced from £10,000 to less than £5,000 per patient per year by using biosimilars [Citation3]. This could equate to an annual saving of £3 million to the NHS if all patients with IBD were treated with biosimilars [Citation17]. These data indicate that with the correct support through managed switching programs, similar to those implemented in the UK, patients may be more likely to effectively transition to biosimilars which may have a positive impact on healthcare systems.

Finally, IBD nurses are important for patients care since they usually touch with patients more frequently than physicians. As the roles of nurses are critical addressing patients’ concerns, patient education and empowerment, education in nurses is required that nurses can deliver the correct information about biosimilars [Citation50].

6. Conclusions

Despite clinical evidence, many patients are still concerned about the efficacy and safety of biosimilars [Citation12], or starting on biosimilars treatment. It is the responsibility of the HCP to address and alleviate these concerns with patients. Increasing healthcare costs and constraints on healthcare budgets may have a negative impact on patients with chronic debilitating conditions [Citation1,Citation2], such as IBD. Although biologics are effective therapies for IBD, they are expensive [Citation1,Citation19] and some countries across Europe have poor access to these agents [Citation51], which could lead to potentially inappropriate management and adverse outcomes. Clinical data indicate that biosimilars demonstrate long-term efficacy and safety in patients with chronic conditions, such as IBD [Citation8–Citation10]. Moreover, due to their tailored development program [Citation5], biosimilars offer a more cost-effective therapeutic alternative [Citation1,Citation3,Citation17]. Patients favor transparency [Citation47]; therefore, optimizing patient-HCP interactions through a structured communication strategy [Citation45], shared decision-making, and the development of managed switching programs [Citation49] may increase confidence (as well as adherence to treatment) with biosimilars. This may in turn aid patients who are transitioning from a biologic to biosimilar therapy or starting their first biosimilar. By taking a more active role in addressing potential patient concerns about biosimilars, HCPs can help to reassure those patients who may benefit from biosimilar therapy, but who might otherwise disagree with the treatment plan and/or be non-adherent to the treatment.

7. Expert commentary

It has been more than a decade since the first biosimilar (somatropin) was approved in the EU in 2006 [Citation1,Citation52]. The technology involved in the manufacturing of biologics has significantly advanced, including the capability to characterize in detail the molecular and functional attributes of monoclonal antibodies, which has led to the development of high-quality biosimilars. This, coupled with comparative pre-clinical and clinical studies in a sensitive indication, fulfills the strict standards set by the EMA in the EU [Citation5] to receive marketing authorization after patent expiration of originator products. The worldwide expenditure on biologics is growing and some analysts predict that by 2020, biosimilars will comprise 4–10% of the total biologic market [Citation53]. As of August 2018, several biosimilars were approved by the EMA. For IBD, four of these were infliximab and six were adalimumab biosimilars (), and these numbers are expected to increase. The introduction of biosimilars could increase competition, resulting in a reduction in pricing for the total market [Citation54]. This increase in price competition may be further challenged by the introduction of multiple biosimilars and, as a consequence, price reduction may ultimately result in increased patient access.

On the other hand, price reduction and entrance of multiple biosimilars might influence prescription habits, and price reductions of the originator product may result in reverse switches (from biosimilar to originator). A randomized, double-blind study in patients with chronic plaque-type psoriasis demonstrated equivalent efficacy and comparable safety and immunogenicity among patients who were treated with the originator etanercept, the biosimilar etanercept, or went through more than one switch (originator to biosimilar and vice versa) during treatment [Citation55]. Additionally, cross-immunogenicity data in patients with IBD showed that antibodies to the originator infliximab recognize and cross-react with infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) to a similar degree, suggesting similar immunogenicity of these two agents [Citation56].

When multiple biosimilars of the same compound are available, switching between different biosimilar compounds may be possible but this may cause uncertainty about long-term immunogenicity of these products. The BIOSIM01 study was an observational, retrospective study in patients with IBD, which aimed to determine if antibodies to infliximab cross-react with the biosimilars CT-P13 and SB2. Patients were treated with either the infliximab originator only, CT-P13 only, or the infliximab originator followed by a switch to CT-P13. Sera from these patients was used in a bridging enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to cross-link patient antibodies to the infliximab originator, CT-P13, or SB2. The results of this study showed that there was full cross-reactivity between the infliximab originator and the biosimilars CT-P13 and SB2, regardless of treatment. These data suggest that immunodominant epitopes present in the infliximab originator are equally present in CT-P13 and SB2, and that these infliximab biosimilars have the same degree of reactivity as the originator product [Citation57]. This demonstrates cross-reactivity between these agents. However, at present, it is unknown if multiple switches between biosimilar compounds remain to have a safe, long-term immunogenicity profile.

When multiple biosimilars of the same compounds are available, it seems that the first biosimilar to the market will have the greatest uptake. However, the choice of biosimilar – hypothesizing a non-significant price difference in a competitive market – would also be driven by post-marketing studies, as well as ‘added values.’ Therefore, biosimilar companies should seek for ‘added values’ beyond the biosimilar itself to improve experience of patients, healthcare providers, as well as payers.

8. Five-year view

As of August 2018, there were four infliximab biosimilars and six adalimumab biosimilars approved for use in IBD in Europe (). It is expected that the biosimilars market will grow substantially in the coming years with several pharmaceutical companies working on biosimilar development. In August 2018, there were 12 biosimilar products approved for use by the FDA [Citation58], and it is likely that since the approval process for biosimilars has been finalized, more biosimilars will be available to the US market.

The growing body of evidence supports the biosimilarity concept, and with more biosimilar products becoming available to the market, switching patients to these agents for economic reasons will become more common. The potential cost savings associated with biosimilars is expected to reduce the pressure on healthcare systems and these savings could be invested into other areas of healthcare where there are funding gaps. The introduction of biosimilars into routine clinical practice may also increase competition with originator biologics, causing pharmaceutical companies to reduce the overall price of biologics, thereby increasing patient access to treatment.

Patients’ trust in HCPs remains key and it is expected that the growing knowledge of HCPs regarding biosimilars will lead to successful adaption of the biosimilar paradigm and will also increase patients’ confidence in these agents. Moreover, the accumulation of biosimilar switching data could lead to the development of evidence-based managed switching protocols, which emphasizes why HCPs should be mindful of their role in instilling trust in their patients regarding biosimilars.

Key issues

Use of high-cost biologics in chronic diseases such as IBD is having a significant impact on healthcare costs.

The development of high-quality biosimilars when biologic patents expire, together with the use of quicker and less costly biomanufacturing processes, offers a therapeutic alternative with the potential for substantial cost savings.

Concerns among patients with IBD, as well as among HCPs, still exist and awareness of biosimilars among the general population is low, despite the EMA’s strict regulation about marketing authorization of biosimilars and requirements for post-marketing safety and immunogenicity studies.

HCPs can employ a variety of strategies to increase patients’ confidence when starting with or switching to biosimilars including: positive framing; application of a structured communication strategy for non-mandatory transitioning; patient engagement and HCP-driven patient education; and use of a managed switching program to support patients through the transition process.

Declaration of interest

K. Gecse has received consultancy fees and/or speaker’s honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ferring, Hospira, Immunic Therapeutics, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Takeda, TiGenix, and Tillotts.

G. D’Haens has served as an advisor for AbbVie, Ablynx, Amakem, Amgen, AM-Pharma, Avaxia Biologics, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene/Receptos, Celltrion, Cosmo, Covidien/Medtronic, Ferring, Dr Falk Pharma, Eli Lilly, enGene, Galapagos, Genentech/Roche, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Immunic Therapeutics, Johnson & Johnson, Lycera, Medimetrics, Millenium/Takeda, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Nextbiotics, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Pfizer/Hospira, Prometheus Laboratories/Nestlé, Protagonist Therapeutics, Robarts Clinical Trials, Salix, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, SetPoint Medical, Shire, Teva, TiGenix, Tillotts, Topivert, Versant Ventures, and Vifor Pharma. G D’Haens has also received speaker fees from AbbVie, Biogen, Ferring, Johnson & Johnson, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Norgine, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Shire, Millenium/Takeda, Tillotts, and Vifor Pharma.

F. Cummings has received advisory board fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Celltrion, Hospira/Pfizer, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Napp, and Takeda. F Cummings has also received speaker fees from AbbVie, Biogen, Hospira/Pfizer, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Napp, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, and Takeda; and has had research collaborations with AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, GlaxoSmithKline, Hospira/Pfizer, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Takeda.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they have previously served as a consultant to Samsung Bioepis.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Gemma McGregor, PhD, of CMC AFFINITY, a division of Complete Medical Communications Ltd, Glasgow, UK, and funded by Samsung Bioepis, Incheon, Republic of Korea, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Additional information

Funding

References

- McCamish M, Woollett G. Worldwide experience with biosimilar development. MAbs. 2011 Mar–Apr;3(2):209–217. PubMed PMID: 21441787; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3092622.

- Blackstone EA, Joseph PF. The economics of biosimilars. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013 Sep;6(8):469–478. PubMed PMID: 24991376; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4031732.

- Royal College of Physicians. National clinical audit of biological therapies. 2016 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/national-clinical-audit-biological-therapies-annual-report-2016

- Calo-Fernandez B, Martinez-Hurtado JL. Biosimilars: company strategies to capture value from the biologics market. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2012 Dec 12;5(12):1393–1408. PubMed PMID: 24281342; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3816668.

- European Medicines Agency. Biosimilars in the EU: information guide for healthcare professionals. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Leaflet/2017/05/WC500226648.pdf

- IMS Health. Shaping biosimilars opportunity: a global perspective on the evolving biosimilars landscape. 2011 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: https://weinberggroup.com/pdfs/Shaping_the_biosimiliars_opportunity_A_global_perspective_on_the_evolving_biosimiliars_landscape.pdf

- Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Dec;12(12):720–727. PubMed PMID: 26323879.

- Farkas K, Rutka M, Ferenci T, et al. Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 therapy is effective and safe in maintaining remission in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis - experiences from a single center. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017 Nov;17(11):1325–1332. PubMed PMID: 28819991.

- Kang B, Lee Y, Lee K, et al. Long-term outcomes after switching to CT-P13 in pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a single-center prospective observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018 Feb 15;24(3):607–616. PubMed PMID: 29390113.

- Smits LJT, Grelack A, Derikx LAAP, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes after switching from remicade to biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017 Nov;62(11):3117–3122. PubMed PMID: 28667429; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5649598.

- Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2304–2316.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lonnfors S, Roblin X, et al. Patient perspectives on biosimilars: a survey by the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017 Jan;11(1):128–133. PubMed PMID: 27481878.

- European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on similar biological medicinal products. 2014 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/10/WC500176768.pdf

- Administration FaD. Biosimilar and interchangeable products. [cited 2018 Nov]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm580419.htm

- Organization WH. Similar biotherapeutic products. [cited 2018 Nov]. Available from: http://www.who.int/biologicals/biotherapeutics/similar_biotherapeutic_products/en/

- Ben-Horin S, Vande Casteele N, Schreiber S, et al. Biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease: facts and fears of extrapolation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Dec;14(12):1685–1696. PubMed PMID: 27215364.

- Royal College of Physicians. UK IBD audit highlights potential huge cost savings of using new biosimilar medicines. 2016 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/news/uk-ibd-audit-highlights-potential-huge-cost-savings-using-new-biosimilar-medicines

- Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2013 May;7(4):322–337. PubMed PMID: 23395397; eng.

- van der Valk ME, Mangen MJ, Leenders M, et al. Healthcare costs of inflammatory bowel disease have shifted from hospitalisation and surgery towards anti-TNFalpha therapy: results from the COIN study. Gut. 2014 Jan;63(1):72–79. PubMed PMID: 23135759.

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018 Dec 23;390(10114):2769–2778. PubMed PMID: 29050646; eng.

- European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Assessment report: remsima. 2013 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002576/WC500151486.pdf

- Inotai A, Csanadi M, Petrova G, et al. Patient access, unmet medical need, expected benefits, and concerns related to the utilisation of biosimilars in Eastern European countries: a survey of experts. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9597362. PubMed PMID: 29546072; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5818964. eng.

- Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilars approved in Europe. 2011 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Biosimilars-approved-in-Europe

- European Medicines Agency. Zessly. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/004647/WC500249650.pdf

- Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. EMA approves adalimumab and trastuzumab biosimilars. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://gabionline.net/Biosimilars/News/EMA-approves-adalimumab-and-trastuzumab-biosimilars

- European Medicines Agency. Hefiya. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Summary_of_opinion_-_Initial_authorisation/human/004865/WC500249885.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Halimatoz. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Summary_of_opinion_-_Initial_authorisation/human/004866/WC500249881.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Hyrimoz. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Summary_of_opinion_-_Initial_authorisation/human/004320/WC500249883.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Trazimera. 2018. [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Summary_of_opinion_-_Initial_authorisation/human/004463/WC500249790.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Kanjinti. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Summary_of_opinion_-_Initial_authorisation/human/004361/WC500246366.pdf

- Strik AS, van de Vrie W, Bloemsaat-Minekus JPJ, et al. Serum concentrations after switching from originator infliximab to the biosimilar CT-P13 in patients with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease (SECURE): an open-label, multicentre, phase 4 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Mar 29;3(6):404–412. PubMed PMID: 29606564; eng.

- Arguelles-Arias F, Guerra Veloz MF, Perea Amarillo R, et al. Effectiveness and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in real life at 6 months. Dig Dis Sci. 2017 May;62(5):1305–1312. PubMed PMID: 28281165; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5487700. eng.

- Fiorino G, Manetti N, Armuzzi A, et al. The PROSIT-BIO cohort: a prospective observational study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab biosimilar. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Feb;23(2):233–243. PubMed PMID: 28092307; eng.

- Gecse KB, Lovasz BD, Farkas K, et al. Efficacy and safety of the biosimilar infliximab CT-P13 treatment in inflammatory bowel diseases: a prospective, multicentre, nationwide cohort. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2016 Feb;10(2):133–140. PubMed PMID: 26661272; eng.

- Gonczi L, Vegh Z, Golovics PA, et al. Prediction of short- and medium-term efficacy of biosimilar infliximab therapy. Do trough levels and antidrug antibody levels or clinical and biochemical markers play the more important role? J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017 Jun 1;11(6):697–705. PubMed PMID: 27838610; eng.

- Schmitz EMH, Boekema PJ, Straathof JWA, et al. Switching from infliximab innovator to biosimilar in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month multicentre observational prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb;47(3):356–363. PubMed PMID: 29205444; eng.

- Jacobs I, Singh E, Sewell KL, et al. Patient attitudes and understanding about biosimilars: an international cross-sectional survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:937–948. PubMed PMID: 27307714; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4889091.

- Danese S, Fiorino G, Michetti P. Changes in biosimilar knowledge among European Crohn’s Colitis Organization [ECCO] members: an updated survey. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2016 Nov;10(11):1362–1365. PubMed PMID: 27112706.

- Danese S, Fiorino G, Michetti P. Viewpoint: knowledge and viewpoints on biosimilar monoclonal antibodies among members of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2014 Nov;8(11):1548–1550. PubMed PMID: 25008477; eng.

- Chapman SR, Fitzpatrick RW, Aladul MI. Knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare professionals towards infliximab and insulin glargine biosimilars: result of a UK web-based survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Jun 21;7(6):e016730. PubMed PMID: 28637743; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5726079. eng.

- Faasse K, Petrie KJ. The nocebo effect: patient expectations and medication side effects. Postgrad Med J. 2013 Sep;89(1055):540–546. PubMed PMID: 23842213.

- Faasse K, Cundy T, Gamble G, et al. The effect of an apparent change to a branded or generic medication on drug effectiveness and side effects. Psychosom Med. 2013 Jan;75(1):90–96. PubMed PMID: 23115341.

- Rezk MF, Pieper B. Treatment outcomes with biosimilars: be aware of the nocebo effect. Rheumatol Ther. 2017 Dec;4(2):209–218. PubMed PMID: 29032452; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5696297. eng.

- Bingel U, Wanigasekera V, Wiech K, et al. The effect of treatment expectation on drug efficacy: imaging the analgesic benefit of the opioid remifentanil. Sci Transl Med. 2011 Feb 16;3(70):70ra14. PubMed PMID: 21325618.

- Tweehuysen L, Huiskes VJB, van Den Bemt BJF, et al. Open-label, non-mandatory transitioning from originator etanercept to biosimilar SB4: six-month results from a controlled cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Sep;70(9):1408–1418. PubMed PMID: 29609207; eng.

- Tweehuysen L, Huiskes VJB, Bjf VDB, et al. Higher acceptance and persistence rates after biosimilar transitioning in patients with a rheumatic disease after employing an enhanced communication strategy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:557.

- Lönnfors S. Patient perspective: lessons drawn from the biologics and biosimilars survey. Patient Advocacy and Safety Conference; 2016 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.efcca.org/sites/default/files/Lessons%20from%20BAB%20survey.pdf

- Siegel CA. Shared decision making in inflammatory bowel disease: helping patients understand the tradeoffs between treatment options. Gut. 2012 Mar;61(3):459–465. PubMed PMID: 22187072.

- Razanskaite V, Bettey M, Downey L, et al. Biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: outcomes of a managed switching programme. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017 Jun 1;11(6):690–696. PubMed PMID: 28130330.

- Armuzzi A, Avedano L, Greveson K, et al. Nurses are critical in aiding patients transitioning to biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease: education and communication strategies. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2018 Oct 4. PubMed PMID: 30285235; eng. DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy150

- The European Federation of Crohn’s & Ulcerative Colitis Associations. Biologics and biosimilars: patient access and advocacy workshop. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.efcca.org/sites/default/files/Rome_Workshop_Report.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Omnitrope. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/000607/WC500043689.pdf

- European Pharmaceutical Review. Biosimilars: the future of pharma? An interview with Boehringer Ingelheim. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/article/51115/biosimilars-future-pharma/

- Quintiles IMS. The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/23102

- Griffiths CEM, Thaci D, Gerdes S, et al. The EGALITY study: a confirmatory, randomized, double-blind study comparing the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of GP2015, a proposed etanercept biosimilar, vs. the originator product in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Apr;176(4):928–938. PubMed PMID: 27787890; eng.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Benhar I, et al. Cross-immunogenicity: antibodies to infliximab in Remicade-treated patients with IBD similarly recognise the biosimilar Remsima. Gut. 2016 Jul;65(7):1132–1138. PubMed PMID: 25897019; eng.

- Antibodies to infliximab in patients treated with either the reference biologic or the biosimilar CTP13 show identical reactivity towards biosimilars CTP13 and SB2 in inflammatory bowel disease, P633 Sess. 2017. Available from: https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/publications/congress-abstract-s/abstracts-2017/item/p633-antibodies-to-infliximab-in-patients-treated-with-either-the-reference-biologic-or-the-biosimilar-ct-p13-show-identical-reactivity-towards-biosimilars-ct-p13-and-sb2-in-inflammatory-bowel-disease-2.html

- US Food and Drug Adminstration. FDA-approved biosimilar products. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm580432.htm