ABSTRACT

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of the different pharmacological agents in preventing post-ERCP acute pancreatitis

Methods

We included clinical trials of pharmacological interventions for prophylaxis of acute post-ERCP pancreatitis. The event evaluated was acute pancreatitis. We conducted a search strategy in MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to nowadays. We reported the information in terms of relative risks (RR) with a 95% confidence interval. We assessed the heterogeneity using the I2 test.

Results

We included 84 studies for analysis (30,463 patients). The mean age was 59.3 years (SD ± 7.01). Heterogeneity between studies was low (I2 = 34.4%) with no inconsistencies (p = 0.2567). Post ERCP pancreatitis was less in prophylaxis with NSAIDs (RR 0.65 95% CI [0.52 to 0.80]), aggressive hydration with Lactate Ringer (RR 0.32 95% CI [0.12–0.86]), NSAIDs + isosorbide dinitrate (RR 0.28 95% CI [0.11–0.71]) and somatostatin and analogues (RR 0.54 [0.43 to 0.68]) compared with placebo.

Conclusions

NSAIDs, the Combination of NSAIDs + isosorbide dinitrate, somatostatin and analogues, and aggressive hydration with lactate ringer are pharmacological strategies that can prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis when compared to placebo. More clinical trials are required to determine the effectiveness of these drugs.

1. Introduction

Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) pancreatitis is the most common adverse event derived from the use of the technique [Citation1–3] because of the diagnosis and the management of the multiple conditions affecting the biliary-pancreatic tree. The incidence can vary between 2.1% to 24.4% [Citation4–6]. Mortality from this cause is not negligible either; some works [Citation1] have reported that the associated mortality was 3.08 (95% CI 1.65–4.51). In addition to morbidity, post-ERCP pancreatitis is a costly entity; for 2012, in the United States, the costs of managing post-ERCP pancreatitis amounted to 150 million dollars [Citation7].

The pathophysiology of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis is not well understood. Multiple aggression mechanisms have been described, which classify it as a multifactorial event that includes a combination of events inherent to the patient (chemical, mechanical, hydrostatic, thermal, enzymatic, allergic, and/or microbiological) and surgical intervention (excessive manipulation of the sphincter Oddi, injection of contrast into the pancreatic duct) [Citation8].

In order to prevent acute post-ERCP pancreatitis, multiple pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions have been studied. Pharmacological interventions include vigorous hydration with crystalloids [Citation9,Citation10], protease inhibitors such as intravenous Nafamostat [Citation11], NSAIDs in different routes of administration [Citation12–14], among others. In each of these studies, the interventions carried out have shown different degrees of effectiveness for preventing pancreatitis. However, prophylactic management remains controversial due to a) the current problem of regular external validity that clinical trials carried out with this objective present and b) the lack of comparisons between treatments (most pharmacological treatments have been compared with placebo). With those mentioned above, the need arises to understand if the effectiveness of the Pharmacological management is comparable among them or if, on the contrary, one intervention may be more effective than another.

Post-ERCP acute pancreatitis affects many patients every year with individual, family, social and economic consequences on a large scale, so it is essential to establish whether the measures used to prevent post ERCP pancreatitis may benefit high-risk patients. This finding would allow the standardization of clinical management guidelines that reduce this event and improve patients’ quality of life. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effectiveness of the different pharmacological agents in preventing post-ERCP acute pancreatitis in patients at risk.

2. Methods

We performed this review following the Cochrane Collaboration recommendations following the PRISMA statutes. We registered the protocol in PROSPERO (CRD42018114302).

2.1. Inclusion criteria

We included randomized controlled clinical trials that included patients evaluated with pharmacological interventions for the prophylaxis of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The intervention was any pharmacological therapy for the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The primary objective was the effectiveness of these different pharmacological agents, defined as the frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis reported by the authors. The event of acute post-ERCP pancreatitis was defined as pain in the irradiated back band, of the epi-mesogastric location of burning or oppressive colic type that does not yield to the administration of symptomatic management. Also, the increase of serum amylase more than three times the normal value in 24 hours. The presence of radiological changes consistent with the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. For all objectives, the studies had to have at least 24 hours of follow-up. There were no language restrictions in the search. We excluded animal studies and non-pharmacological surgical or endoscopic interventions.

2.2. Information sources

We carried out the literature search according to the Cochrane recommendations. We searched MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from inception to nowadays (Appendix 1). We searched in google scholar, clinical trials, conferences, reference list, thesis database, and asked different authors to saturate the information.

2.3. Data collection

Each reference was inspected by title and abstract. Subsequently, the studies’ full-text were reviewed, applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and we extracted the data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Relevant data were collected using a standardized data extraction tool that included the following variables: Name of the authors, year of publication, title, study design, geographic location, objectives, age, gender, number of participants, conflicts of interest, intervention, clinical and paraclinical variables of follow-up and outcome (pancreatitis).

2.4. Data analysis/results synthesis

The statistical analysis was carried out in R with the frequentist model of the netmeta library together with the netmeta command. We reported the information on relative risks (RR) with a 95% confidence interval for categorical outcomes according to the type of variables studied. Subsequently, we pooled the information through a random effect meta-analysis according to the expected heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 test. The transitivity assumptions were taken into account and evaluated according to the type of comparisons. Similarities and possible effect modifications were considered during the different comparisons paired or not.

2.5. Risk of bias

We assessed the risk of bias for each study using Cochrane’s risk of bias tool by REVMAN 5.3. Two independent investigators judged the possible risk with the extracted information that is classified as ‘high risk,’ ‘low risk,’ or ‘unclear risk.’ A graphical representation of the risk of bias was constructed using the Cochrane REVMAN 5.3 collaboration tool

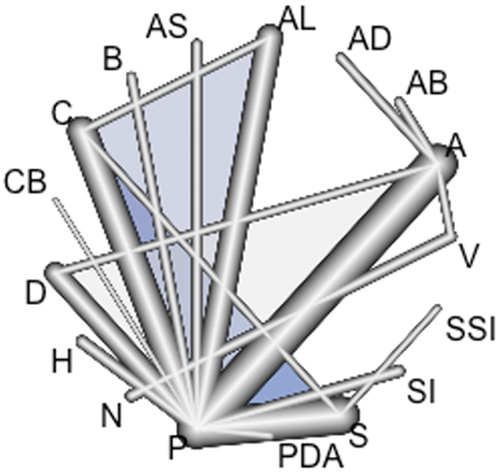

2.6. The geometry of the network

For each treatment, we estimated the probability of appearing in a position to infer a classification of treatments. Through the network geometry, we compared all treatments versus placebo. The resulting significant pharmacological options were compared with the rest of the treatments. We designed network diagrams to show the amount of evidence available for each outcome and the most frequent comparisons. The nodes’ size was proportional to the total number of patients assigned to each intervention in the clinical trials, and the width of the lines was proportional to the number of studies evaluated in each comparison.

2.7. Inconsistency assessment

We evaluated the state of consistency through direct and indirect comparisons in pharmacological therapies. Statistical inconsistency was also evaluated. We considered the model inconsistent if the p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

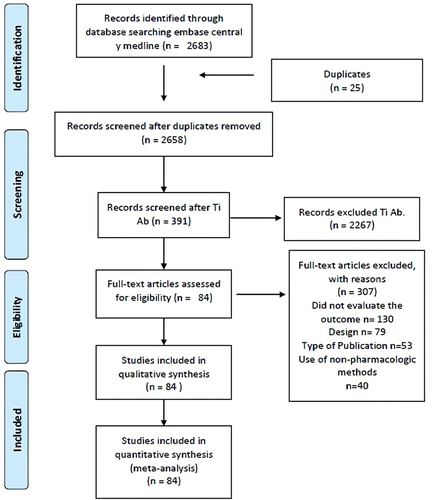

We found 2683 studies using the search strategy. We removed 25 duplicates. After review by title/abstract and full text, 84 records that met the inclusion criteria were included ().

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

Thirty thousand four hundred sixty-three patients were included, with a median of 293 patients per study (Interquartile range [IQR] 157 to 456). The mean age of the patients was 59.3 years (SD ±7.01). The male: female ratio was 1: 1.2. Seventy-one studies compared some type of intervention with placebo ().

Table 1. Clinical trials included in the network meta-analysis.

3.3. Excluded studies

We excluded 307 studies due to the following reasons: a) they did not assess the presence of post ERCP pancreatitis, b) the design did not correspond to a randomized clinical trial, c) the type of publication did not correspond to a scientific article, and/or d) they used prophylactic methods other than pharmacological ones.

3.4. Geometric network abstract

Seventy-one studies compared some type of pharmacological intervention with placebo. Of these, 23 studies used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [Citation7,Citation12,Citation15–35]; four studies compared placebo with allopurinol [Citation36–39], one evaluated somatostatin in conjunction with NSAIDs [Citation40], one evaluated beta carotenes [Citation41], four evaluated corticosteroids [Citation42–45], one evaluated the use of nifedipine [Citation46], six studies compared placebo with glyceryl trinitrate [Citation47–52], two estimated the effect of heparin [Citation53,Citation54], one study compared the effect of udenafil aceclofenac [Citation55] and placebo, 22 studies evaluated the use of somatostatin and analogues [Citation56–77], one compared risperidone to placebo [Citation78], Moreover, one evaluated the aggressive hydration regimen with lactate ringer [Citation9].

Three studies compared NSAIDs versus another pharmacological intervention. In one study, the intervention was the Combination of antibiotics and NSAIDs [Citation79],

another study evaluated aggressive hydration with lactate ringer [Citation80] Moreover, the third compared them with Isosorbide Dinitrate [Citation81]. Two studies compared aggressive hydration regimen with lactate ringer vs. aggressive hydration regimen with normal lactate [Citation82,Citation83].

Finally, a study compared somatostatin vs. somatostatin and risperidone [Citation84] ().

Figure 2. Post-ERCP acute pancreatitis network. A: non-steroidal analgesics (NSAIDs); AB: NSAIDs and Antibiotics; AD: NSAIDs and Isosorbide Dinitrate; AL: Allopurinol; AS: NSAIDs and somatostatin; B: beta carotenes; C: Corticosteroids; CB: Nifedipine; D: glyceryl trinitrate; H: Heparin; N: hydration with normal lactate; PDA: udenafil aceclofenac; S: somatostatin and analogs; SI: Risperidone; SSI: unilastatin-Risperidone; V: aggressive hydration with lactate ringer.

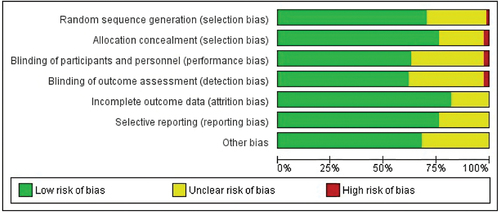

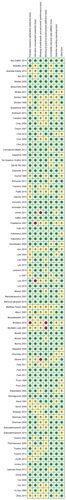

3.5. Risk of bias in included studies

All but six studies were considered low risk. One study due to the random sequence generation, two studies due to group allocation concealment, two due to non-masking of the study personnel, and two due to the non-masking of the assessor. Montaño’s 2006 study [Citation28] it was classified as high risk due to the generation of the random sequence and due to the evaluator’s non-masking. The risk of reporting bias was measured as low as well ( and ).

3.6. Post-ERCP acute pancreatitis

Post-ERCP pancreatitis was 35% lower in patients who received NSAID prophylaxis than patients who received placebo (RR 0.65 95% CI [0.52 to 0.80]).

Aggressive hydration with Lactate Ringer was also significantly protective compared to placebo (RR 0.32 95% CI [0.12 to 0.86]). NSAID therapy in Combination with Isosorbide dinitrate was also protective when compared to placebo (RR 0.28 95% CI [0.11 to 0.71]), and somatostatin analogs were equally effective (RR 0.54 95% CI [0.43 to 0.68]).

There were no significant associations between antibiotics, allopurinol, somatostatin, beta-carotenes, corticosteroids, nifedipine, glyceryl trinitrate, heparin, aggressive hydration with lactate versus placebo concerning the outcome of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis.

NSAIDs, aggressive hydration with ringer lactate, NSAIDs + isosorbide dinitrate, and somatostatin analogues were independently compared with the rest of the pharmacological therapies to determine whether there were inconsistencies with previously estimated associations with placebo. We did not find significant differences between the effectiveness of the four treatments (see ). However, these four pharmacological modalities were significantly superior to the others.

Figure 5. Forrest plot for post-ERCP acute pancreatitis A: non-steroidal analgesics (NSAIDs); AB: NSAIDs and Antibiotics; AD: NSAIDs and Isosorbide Dinitrate; AL: Allopurinol; AS: NSAIDs and somatostatin; B: beta carotenes; C: Corticosteroids; CB: Nifedipine; D: glyceryl trinitrate; H: Heparin; N: hydration with normal lactate; PDA: udenafil aceclofenac; S: somatostatin and analogs; SI: Risperidone; SSI: unilastatin-Risperidone; V: aggressive hydration with lactate ringer.

3.7. Inconsistency exploration

However, these four pharmacological modalities were significantly superior to the others. For the post ERCP pancreatitis event, heterogeneity between studies was low (I2 = 34.4%) with no inconsistencies (p = 0.2567). The p-value was higher for studies comparing placebo with allopurinol (0.8127), risperidone (0.7361), and corticosteroids (0.7203) (See annex).

The comparisons that made it possible to evaluate the consistency of the model were: NSAIDs versus Glyceryl trinitrate (p = 0.7746), NSAIDs versus placebo (p = 0.8263), Allopurinol versus corticosteroids (p = 0.7391) and Allopurinol versus placebo (p = 0.5539). We concluded that there were no inconsistencies in the model.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of main results

In the present study, NSAIDs, NSAIDs + isosorbide dinitrate, somatostatin analogues, and aggressive hydration with lactate ringer were the pharmacological strategies that prevented post-ERCP pancreatitis when compared to placebo. None of these methods were superior to each other. There were no significant associations for antibiotics, allopurinol, the combined use of somatostatin and NSAIDs, beta-carotenes, corticosteroids, nifedipine, heparin, regular hydration with lactate ringer, udenafil aceclofenac, glyceryl trinitrate, risperidone, and unilastatin-risperidone.

4.2. Comparison with the literature

Previous systematic reviews evaluated endoscopic interventions in addition to pharmacological ones. Akshintala et al. [Citation85] evaluated 16 pharmacological interventions. They concluded that topical epinephrine administered endoscopically and NSAIDs administered rectally were effective agents in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis. In our study, we decided to exclude topically administered epinephrine as a pharmacological strategy, as well as any endoscopic or procedural measure. We considered the above mentioned due to the difficulty of finding the pancreatic papilla and the probability of generating adverse events such as bleeding, pancreatitis, and perforations that could complicate the patient’s clinical status [Citation86].

Furthermore, Akshintala et al. [Citation85] concluded that NSAIDs, regardless of administration route, turned out to be an effective prevention measure for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Like the Akshintala group, Kubillium et al. [Citation87]

In 2015 confirmed that NSAIDs, in general, are appropriate for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis, especially for high-risk cases.

Lyu et al. [Citation88] concluded that gabexate, as a somatostatin analog, is the most effective drug for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in a previously published meta-analysis. In this study, NSAIDs, glyceryl trinitrate, and unilastatin also presented protective factors. In our study, glyceryl trinitrate did not confirm its effectiveness.

This meta-analysis confirms what is described by Akshintala et al. [Citation85] and Kubillium et al. [Citation87] on the protective effect conferred by NSAIDs administered before ERCP. NSAIDs have inhibitory properties on phospholipase A2, the cyclooxygenase cascade, and the neutrophil-endothelium interactions and different pathways to reduce the activation of the inflammatory phenomenon, which could justify the positive results found by this study and previous ones [Citation12,Citation89].

Unlike previous studies, this study found that somatostatin inhibitors and other peptides also have a comparable protective effect with NSAIDs and aggressive hydration with lactate ringer. By inhibiting pancreatic enzymes’ secretion, it reduces the risk of increased hydrostatic pressure that, added to that already provided by contrast liquid, generates post-ERCP pancreatitis [Citation77]. Therapy with NSAIDs + isosorbide dinitrate reduces the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis for a multimodal mechanism.

4.3. Implications for practice

The causes of post-ERCP pancreatitis are not well understood. Multiple theories have been developed in order to explain the cause and the pathophysiological mechanisms by which acute post-ERCP pancreatitis develops, the most important of which consist of the presence of a transient ischemic or inflammatory event caused by various mechanisms, among these, decrease in the mean arterial pressures of patients during the procedure or the presence of mild local insult or increased intraductal pressure by cannulation or injection of contrast into the pancreatic duct [Citation90]. With these premises, various pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions have been proposed. In this study, the use of isotonic solutions turned out to be a prevention strategy for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Increasing the mean arterial pressure using hydration schemes allows the perfusion of organs and tissues to be improved, reducing the described ischemic event.

From the findings found in this meta-analysis and previously published studies, the need arises to establish pre-surgical preventive protocols, especially in high-risk patients, to reduce the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guide [Citation91] suggests using 100 mg of diclofenac transrectal or indomethacin as first-line preventive management, aggressive hydration with lactate ringer in case of intolerance of NSAIDs, or 5 mg of glyceryl trinitrate in case of contraindication of the previous measures.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

This meta-analysis showed that NSAIDs, aggressive hydration with ringer lactate, therapy with NSAIDs + isosorbide dinitrate, and somatostatin inhibitors and analogs are effective pharmacological strategies to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Since there was no heterogeneity or inconsistency, a network analysis was possible.

This study has some limitations. The first is related to the sample size; not including observational studies could have some impact. On the other hand, unlike controlled clinical trials, observational studies allow information on more variables to be obtained, thus approaching the reality of clinical practice. Although we clarify that randomized clinical trials are the ideal method to evaluate an intervention, but they are difficult to reproduce in clinical practice. Regarding the non-evaluation of non-pharmacological measures, it could influence the sample size, but also, but these are the cause of other adverse events that could alter the outcomes and, therefore, the result of our study. Further prospective studies are required to confirm the effectiveness of these groups of drugs against each other.

5. Conclusion

NSAIDs, the combination of NSAIDs + isosorbide dinitrate, somatostatin analogues, and aggressive hydration with lactate ringer are pharmacological strategies that can prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis when compared to placebo. More clinical trials are required to compare the effectiveness of these groups of drugs with each other.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chen J-J, Wang X-M, Liu X-Q, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review of clinical trials with a large sample size in the past 10 years. Eur J Med Res [Internet]. 2014;19(1):26. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-19-26

- Katsinelos P, Lazaraki G, Gkagkalis S, et al. Predictive factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech [Internet]. 2014;24(6):1. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000012

- Ding X, Zhang FC, Wang YJ. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon [Internet]. 2015;13(4):218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2014.11.005

- Talukdar R. Complications of ERCP. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2016;30(5):793–805. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.10.007

- Tryliskyy Y, Bryce G. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: pathophysiology, early identification and risk stratification. Adv Clin Exp Med [Internet]. 2018;27(1):149–154. doi: 10.17219/acem/66773

- Kochar B, Akshintala VS, Afghani E, et al. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review by using randomized, controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc [Internet]. 2015 Jan 1 [cited 2020 Sep 30];81(1):143–149.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.06.045

- Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, et al. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2012;366(15):1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111103

- Cooper ST, Slivka A. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36(2):259–276. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.03.006

- Choi JH, Kim HJ, Lee BU, et al. Vigorous periprocedural hydration with lactated ringer’s solution reduces the risk of pancreatitis after retrograde cholangiopancreatography in hospitalized patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2017;15(1):86–92.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.007

- Park CH, Paik WH, Park ET, et al. Aggressive intravenous hydration with lactated ringer’s solution for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical trial. Endoscopy. 2018;50(4):378–385. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-122386

- Yu G, Li S, Wan R. Et alNafamostat mesilate for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2015;44(4):561–569. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000310

- Ishiwatari H, Urata T, Yasuda I, et al. No benefit of oral diclofenac on post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(11):3292–3301. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4251-x

- Sun HL, Han B, Zhai HP, et al. Rectal NSAIDs for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surgeon [Internet]. 2014;12(3):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2013.10.010

- Patai A, Solymosi N, Á V P. Effect of rectal indomethacin for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis depends on difficulties of cannulation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(5):429–437. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000168

- Kato K, Shiba M, Kakiya Y, et al. Celecoxib oral administration for prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a randomized prospective trial. Pancreas. 2017;46(7):880–886. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000852

- Khoshbaten M, Khorram H, Madad L, et al. Role of diclofenac in reducing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(7 PT2). doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05096.x

- Levenick JM, Gordon SR, Fadden LL, et al. Rectal indomethacin does not prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in consecutive patients. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2016;150(4):911–917. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.040

- Lua GW, Muthukaruppan R, Menon J. Can rectal diclofenac prevent post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis? Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):3118–3123. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3609-9

- Mansour-Ghanaei F, Joukar F, Taherzadeh Z, et al. Suppository naproxen reduces incidence and severity of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(21):5114–5121. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i21.5114

- Montaño Loza A, Rodríguez Lomelí X, García Correa JE, et al. Effect of the administration of rectal indomethacin on amylase serum levels after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and its impact on the development of secondary pancreatitis episodes. Rev Esp Enferm Dig [Internet]. 2007;99(6):330–336. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082007000600005

- Murray B, Carter R, Imrie C, et al. Diclofenac reduces the incidence of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(7):1786–1791. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00384-6

- Otsuka T, Kawazoe S, Nakashita S, et al. Low-dose rectal diclofenac for prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(8):912–917. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0554-7

- Senol A, Saritas U, Demirkan H. Efficacy of intramuscular diclofenac and fluid replacement in prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(32):3999–4004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3999

- Sotoudehmanesh R, Khatibian M, Kolahdoozan S, et al. Indomethacin may reduce the incidence and severity of acute pancreatitis after ERCP. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(5):978–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01165.x

- Abu-Safieh Y, Altiti R, Lobadeh M. Diclofenac vs. Placebo in a randomized double blind controlled trial, in post ERCP pancreatitis. Am J Clin Med Res. 2014 Feb 28;2(2):43–46. doi: 10.12691/ajcmr-2-2-1

- Wen ZX, Jun BJ, Hu C, et al. Effect of diclofenac on the levels of lipoxin A4 and resolvin D1 and E1 in the post-ERCP pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(12):2992–2996. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3280-6

- Park S, Chung M, Oh T, et al. Intramuscular diclofenac for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized trial. Endoscopy [Internet]. 2014 Nov 19 [cited 2020 Jun 3];47(1):33–39. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390743

- Montaño-Loza A, García-Correa J, González-Ojeda A, et al. Prevención de hiperamilasemia y pancreatitis posterior a la colangiopancreatografía retrógrada endoscópica con la administración rectal de indometacina. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2006;71(3):262–268.

- Andrade-Dávila VF, Chávez-Tostado M, Dávalos-Cobián C, et al. Rectal indomethacin versus placebo to reduce the incidence of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: results of a controlled clinical trial. BMC Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2015;15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0314-2

- Bhatia V, Ahuja V, Acharya SK, et al. A randomized controlled trial of valdecoxib and glyceryl trinitrate for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(2):170–176. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181eb600e

- Cheon YK, Cho KB, Watkins JL, et al. Efficacy of diclofenac in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in predominantly high-risk patients: a randomized double-blind prospective trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007 Dec;66(6):1126–1132.

- Chik IAN, Jarmin R, Ariffin A, et al. A less invasive method of reducing the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: intravenous diclofenac sodium versus placebo. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018 Oct 1;11(10):140–144. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i10.26474

- de Quadros Onófrio F, Lima JCP, Watte G, et al. Prophylaxis of pancreatitis with intravenous ketoprofen in a consecutive population of ERCP patients: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Surg Endosc Interv Technol. 2017;31(5):2317–2324. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5234-x

- Döbrönte Z, Szepes Z, Izbéki F, et al. Is rectal indomethacin effective in preventing of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(29):10151–10157. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.10151

- Fujita Y, Hasegawa S, Kato Y, et al. Intravenous injection of low-dose flurbiprofen axetil for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients: an interim analysis of the trial. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4(10):E1078–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-115172

- Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Chatzis J, et al. High-dose allopurinol for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective randomized double-blind controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):407–415. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02647-1

- Martinez-Torres H, Rodriguez-Lomeli X, Davalos-Cobian C, et al. Oral allopurinol to prevent hyperamylasemia and acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(13):1600–1606. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1600

- Mosler P, Sherman S, Marks J, et al. Oral allopurinol does not prevent the frequency or the severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(2):245–250. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(05)01572-5

- Romagnuolo J, Hilsden R, Sandha GS, et al. Allopurinol to prevent pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Apr;6(4):465–471.

- Katsinelos P, Fasoulas K, Paroutoglou G, et al. Combination of diclofenac plus somatostatin in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2012;44(1):53–59. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291440

- Lavy A, Karban A, Suissa A, et al. Natural β-carotene for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2004;29(2):e45–e50. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200408000-00018

- Budzyńska A, Marek T, Nowak A, et al. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of prednisone and allopurinol in the prevention of ERCP-induced pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2001;33(9):766–772. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16520

- Dumot JA, Conwell DL, Barry O’Connor J, et al. Pretreatment with methylprednisolone to prevent ERCP-induced pancreatitis: a randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998 Jan;93(1):61–65.

- Sherman S, Blaut U, Watkins JL, et al. Does prophylactic administration of corticosteroid reduce the risk and severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized, prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(1):23–29. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.307

- De Palma GD, Catanzano C. Use of corticosteroids in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: results of a controlled prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Apr;94(4):982–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.999_u.x

- Sand J, Nordback I. Prospective randomized trial of the effect of nifedipine on pancreatic irritation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Digestion. 1993;54(2):105–111. doi: 10.1159/000201021

- Beauchant M, Ingrand P, Favriel JM, et al. Intravenous nitroglycerin for prevention of pancreatitis after therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2008 Aug;40(8):631–636.

- Kaffes AJ, Bourke MJ, Ding S, et al. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of transdermal glyceryl trinitrate in ERCP: effects on technical success and post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(3):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.060

- Kapetanos D, Kokozidis G, Christodoulou D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of pentoxifylline for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(3):513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.1045

- Moretó M, Zaballa M, Casado I, et al. Transdermal glyceryl trinitrate for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized double-blind trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(1):1–7. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.29

- Hao JY, Wu DF, Wang YZ, et al. Prophylactic effect of glyceryl trinitrate on post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(3):366–368. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.366

- Nøjgaard C, Hornum M, Elkjaer M, et al. Does glyceryl nitrate prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(6):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.11.042

- Barkay O, Niv E, Santo E, et al. Low-dose heparin for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Surg Endosc Interv Technol. 2008 Sep;22(9):1971–1976.

- Rabenstein T, Fischer B, Wießner V, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin does not prevent acute post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(6):606–613. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)00159-2

- Lee TY, Choi JS, Oh HC, et al. Oral udenafil and aceclofenac for the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients: a randomized multicenter study. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30(5):602–609. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.5.602

- Bai Y, Ren X, Zhang XF, et al. Prophylactic somatostatin can reduce incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis: multicenter randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2015 Jan 15;75:(5):12–25. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391227

- Bordas JM, Toledo V, Mondelo F, et al. Prevention of pancreatic reactions by bolus somatostatin administration in patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and endoscopic sphincterotomy. Horm Res [Internet]. 1988 [cited 2020 May 26];29(2–3):106–108. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/180981

- Ohuchida J, Chijiiwa K, Imamura N, et al. Randomized controlled trial for efficacy of nafamostat mesilate in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2015;44(3):415–421. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000278

- Park KT, Kang DH, Choi CW, et al. Is high-dose nafamostat mesilate effective for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis, especially in high-risk patients? Pancreas. 2011;40(8):1215–1219. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31822116d5

- Poon RTP, Yeung C, Lo CM, et al. Prophylactic effect of somatostatin on post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(5):593–598. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(99)70387-1

- Poon RTP, Yeung C, Liu CL, et al. Intravenous bolus somatostatin after diagnostic cholangiopancreatography reduces the incidence of pancreatitis associated with therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedures: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2003 Dec;52(12):1768–1773.

- Testoni PA, Bagnolo F, Andriulli A, et al. Octreotide 24-h prophylaxis in patients at high risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(7):965–972. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01015.x

- Thomopoulos KC, Pagoni NA, Vagenas KA, et al. Twenty-four hour prophylaxis with increased dosage of octreotide reduces the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(5):726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.934

- Tsujino T, Komatsu Y, Isayama H, et al. Ulinastatin for pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(4):376–383. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00671-8

- Shah TU, Liddle R, Stanley Branch M, et al. Pilot study of aprepitant for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in high risk patients: a phase ii randomized, double-blind placebo controlled trial. J Pancreas. 2012;13(5):514–518.

- Xiong GS, Wu SM, Zhang X-W, et al. Clinical trial of gabexate in the prophylaxis of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39(1):85–90. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000100010

- Yoo K-S, Huh KR, Kim YJ, et al. Nafamostat mesilate for prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2011;40(2):181–186. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f94d46

- Bordas JM, Toledo-Pimentel V, Llach J, et al. Effects of bolus somatostatin in preventing pancreatitis after endoscopic pancreatography: results of a randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47(3):230–234. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(98)70318-9

- Yoo JW, Ryu JK, Lee SH, et al. Preventive effects of ulinastatin on post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pancreas. 2008;37(4):366–370. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31817f528f

- Li ZS, Pan X, Zhang WJ, et al. Effect of octreotide administration in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis and hyperamylasemia: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial - CME. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jan;102(1):46–51.

- Cavallini G, Tittobello A, Frulloni L, et al. Gabexate for the prevention of pancreatic damage related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 1996 Sep 26 [cited 2020 May 26];335(13): 919–923. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351302.

- Chan HH, Lai KH, Lin CK, et al. Effect of somatostatin in the prevention of pancreatic complications after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71(12):605–609. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70002-4

- Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim GH, et al. Nafamostat mesylate in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis and risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009 Apr;69(4). doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.046

- Concepción-Martín M, Gómez-Oliva C, Juanes A, et al. Somatostatin for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind trial. Endoscopy. 2014 Oct 1;46(10):851–856. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377306

- Jowell PS, Branch MS, Fein SH, et al. Intravenous synthetic secretin reduces the incidence of pancreatitis induced by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Pancreas. 2011;40(4):533–539. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182152eb6

- Lee KT, Lee DH, Yoo BM. The prophylactic effect of somatostatin on post-therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a randomized, multicenter controlled trial. Pancreas. 2008 Nov;37(4):445–448. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181733721

- Manolakopoulos S, Avgerinos A, Vlachogiannakos, et al. Octreotide versus hydrocortisone versus placebo in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(4):470–475. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122614

- Uchino R, Isayama H, Tsujino TY, et al. RESULTS of the Tokyo trial of prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis with risperidone-2: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Gastrointest Endosc [Internet]. 2013;78(6):842–850. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.06.028

- Hauser G, Blažević I, Salkić N, et al. Diclofenac sodium versus ceftazidime for preventing pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(2):602–610. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5004-9

- Masjedizadeh A, Fathizadeh P, Aghamohamadi N. Comparative effectiveness of aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation with lactated Ringer’s solution and rectal indomethacin therapy in the prevention of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a double blind randomised contr. Prz Gastroenterol. 2017;12(4):271–276. doi: 10.5114/pg.2017.72102

- Sotoudehmanesh R, Eloubeidi MA, Asgari AA, et al. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin and sublingual nitrates to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2014;109(6):903–909. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.9

- Buxbaum J, Yan A, Yeh K, et al. Aggressive hydration with lactated ringer’s solution reduces pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2014;12(2):303–307.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.026

- Shaygan-Nejad A, Masjedizadeh AR, Ghavide A, et al. Aggressive hydration with lactated ringer’s solution as the prophylactic intervention for postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a randomized controlled double-blind clinical trial. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(9):838–843. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.170597

- Tsujino T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. The results of the Tokyo trial of prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis with risperidone (Tokyo P3R): a multicenter, randomized, phase II, non-placebo-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(8):982–988. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0698-5

- Akshintala VS, Hutfless SM, Colantuoni E, et al. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: pharmacological prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 2013 Dec [cited 2020 Jun 30];38(11–12):1325–1337. doi: 10.1111/apt.12534

- Navaneethan U, Konjeti R, Lourdusamy V, et al. Precut sphincterotomy: efficacy for ductal access and the risk of adverse events. Gastrointest Endosc [Internet]. 2015 Apr 1 [cited 2020 Jun 30];81(4): 924–931. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.015

- Kubiliun NM, Adams MA, Akshintala VS, et al. Evaluation of pharmacologic prevention of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2015 Jul 1 [cited 2020 Jul 2];13(7): 1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.038

- Lyu Y, Wang B, Cheng Y, et al. Comparative efficacy of 9 major drugs for postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a network meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutaneous Tech [Internet]. 2019 Dec 1 [cited 2020 Jul 6];29(6): 426–432. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000707.

- Zitinic I, Plavsic I, Poropat G, et al. ERCP induced and non-ERCP-induced acute pancreatitis: two distinct clinical entities? Med Hypotheses [Internet]. 2018;113(October 2017):42–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2018.02.017

- Tryliskyy Y, Bryce GJ. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: pathophysiology, early identification and risk stratification. Adv Clin Exp Med [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 2];27(1):149–154. doi: 10.17219/acem/66773

- Dumonceau JM, Kapral C, Aabakken L, et al. ERCP-related adverse events: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline [Internet]. Endoscopy. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 2];52(2):127–149. doi: 10.1055/a-1075-4080

- Mohammad Alizadeh AH, Abbasinazari M, Hatami B, et al. Comparison of rectal indomethacin, diclofenac, and naproxen for the prevention of post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(3):349–54.

- Devière J, Le Moine O, Van Laethem JL, et al. Interleukin 10 reduces the incidence of pancreatitis after therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 2001 Feb 1;120(2):498–505.

- Fujishiro H, Adachi K, Imaoka T, et al. Ulinastatin shows preventive effect on post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in a multicenter prospective randomized study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(6):1065–9.

- Hosseini M, Shalchiantabrizi P, Yektaroudy K, et al. Prophylactic effect of rectal indomethacin administration, with and without intravenous hydration, on development of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis episodes: A randomized clinical trial. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(8):538–43.

- Luo H, Zhao L, Leung J, et al. Routine preprocedural rectal indometacin versus selective post-procedural rectal indometacin to prevent pancreatitis in patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a multicentre, single-blinded, randomised controlled trial. Lancet [Internet]. 2016;387(10035): 2293. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30310-5

- Manes G, Ardizzone S, Lombardi G, et al. Efficacy of postprocedure administration of gabexate mesylate in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized, controlled, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(7):982–7.

- Masci E, Cavallini G, Mariani A, et al.Comparison of Two Dosing Regimens of Gabexate in the Prophylaxis of Post-ERCP Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(10):2182–6.

- Park CH, Paik WH, Park ET, et al. Aggressive intravenous hydration with lactated Ringer’s solution for prevention of postERCP pancreatitis: A prospective randomized multicenter clinical trial. Endoscopy. 2018;50(4):378–85.

- Kim SJ, Kang DH, Kim HW, et al. A Randomized Comparative Study of 24- and 6-Hour Infusion of Nafamostat Mesilate for the Prevention of Post–Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2016;45:1179–1183.

Appendix 1.

Search strategy

Medline (Ovid):

Choledocholithiasis.mp or Exp Choledocholithiasis or Exp common bile duct neoplasms or exp Cholangiocarcinoma or Cholangiocarcinoma.mp or (Cholangiocellular adj2 Carcinoma).mp or (Cholangiocarcinoma* adj2 Extrahepatic).mp or Exp common bile duct disease or (biliar adj2 stricture*).mp or (biliar adj2 injur*).mp or Exp cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic retrograde or (cholangiopancreatograph* adj2 endoscopic).mp or Cholangiopancreatograph*.mp or ercp.mp or Exp ercp

and/

Exp antibiotic prophylaxis or (prophylaxis adj2 antibiotic*).mp or Exp drug therapy or (drug adj2 therap*).mp or Exp pharmacotherapy or Pharmacotherap*.mp or Exp Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal or (Anti-Inflammatory adj2 Agent*).mp or Exp nsaids or Nsaids.mp or Exp isotonic solutions or (isotonic adj2 solution*).mp or Exp fluid therapy or (fluid adj2 therap*).mp or Exp hyperhydration status, organism or (Nafamostat adj2 administration).mp or (ketoprofen adj2 administration).mp or exp diclofenac or diclofenac.mp or exp indomethacin or indomethacin.mp or exp naproxen or naproxen.mp

and/

randomized controlled trial.pt or controlled clinical trial.pt or randomized.ab or placebo.ab or randomly.ab or trial.ab or (clinical adj2 trial).mp or (randomi*ed adj2 controlled adj2 trial).mp or exp double-blind method or exp cohort studies or (cohort adj2 stud*).mp or Non-randomized controlled trials as topic or (non-randomized adj2 stud*).mp or (quasi*experiment adj2 stud*).mp

Embase:

‘common bile duct stone’/exp or (common next/2 bile next/2 duct* Stone):ti,ab or ‘bile duct carcinoma’/exp or (bile next/2 duct next/2 carcinoma*):ti,ab or ‘bile duct cancer’/exp or (bile next/2 duct* next/2 cancer):ti,ab or (bile next/2 duct next/2 cancer next/2 Extrahepatic):ti,ab or ‘common bile duct disease’/exp or (common next/2 bile next/2 duct* next/2 disease*):ti,ab (biliar next/2 stricture*):ti,ab or (biliar next/2 injur*):ti,ab or ‘extrahepatic bile duct obstruction’/exp or (extrahepatic next/2 bile next/2 duct* next/2 obstruct*):ti,ab or ‘endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography’/exp or (endoscopic next/2 retrograde next/2 cholangiopancreatograph*):ti,ab or cholangiopancreatography:ti,ab or ercp:ti,ab

and/

‘antibiotic prophylaxis’/exp or (prophylaxis next/2 antibiotic*):ti,ab or ‘drug therapy’/exp or (drug next/2 therap*):ti,ab or ‘prophylaxis’/exp or ‘antiinflammatory agent’/exp or ‘nonsteroid antiinflammatory agent’/exp or (Anti-Inflammatory next/2 Agent*):ti,ab or (nonsteroid next/2 antiinflammatory agent):ti,ab or ‘isotonic solution’/exp or (isotonic Next/2 solution*):ti,ab or ‘fluid therapy’/exp or (fluid next/2 therap*):ti,ab or ‘fluid resuscitation’/exp or ‘nafamstat mesilate’/exp or (nafamstat next/2 administration):ti,ab or (ketoprofen next/2 administration):ti,ab or ‘diclofenac’/exp or diclofenac:ti,ab or ‘indomethacin’/exp or indomethacin:ti,ab or ‘naproxen’/exp or naproxen:ti,ab or ‘Ringer lactate solution’/exp or (infusion fluid next/2 administration):ti,ab or ‘infusion fluid’/exp or ‘sodium chloride’/exp or (sodium chloride next/2 administration):ti,ab

and/

‘randomized controlled trial’/exp or (randomi*ed NEXT/2 controlled NEXT/2 trial):ti,ab or ‘clinical trial’/exp or (clinical NEXT/2 trial):ti,ab or ‘double blind procedure’/exp or ‘cohort analysis’/exp or (cohort next/2 stud*):ti,ab or (quasi*experimental next/2 stud*):ti,ab

Central (through ovid)

Choledocholithiasis.mp or Exp Choledocholithiasis or Exp common bile duct neoplasms or exp Cholangiocarcinoma or Cholangiocarcinoma.mp or (Cholangiocellular adj2 Carcinoma).mp or (Cholangiocarcinoma* adj2 Extrahepatic).mp or Exp common bile duct disease or (biliar adj2 stricture*).mp or (biliar adj2 injur*).mp or Exp cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic retrograde or (cholangiopancreatograph* adj2 endoscopic).mp or Cholangiopancreatograph*.mp or ercp.mp or Exp ercp

and/

Exp antibiotic prophylaxis or (prophylaxis adj2 antibiotic*).mp or Exp drug therapy or (drug adj2 therap*).mp or Exp pharmacotherapy or Pharmacotherap*.mp or Exp Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal or (Anti-Inflammatory adj2 Agent*).mp or Exp nsaids or Nsaids.mp or Exp isotonic solutions or (isotonic adj2 solution*).mp or Exp fluid therapy or (fluid adj2 therap*).mp or Exp hyperhydration status, organism or (Nafamostat adj2 administration).mp or (ketoprofen adj2 administration).mp or exp diclofenac or diclofenac.mp or exp indomethacin or indomethacin.mp or exp naproxen or naproxen.mp

LILACS

(tw:(mh:” Cholangiopancreatography, Endoscopic Retrograde“)) AND (tw:((mh:Pancreatitis”) NOT (mh:”Pancreatitis, Chronic”))) AND (tw:(tw:”Prophylaxis”)) AND (mh:(ensayo clinico)) OR (tw:(doble ciego)) OR (tw:(experimento clinico)) AND (instance “Regional”)