ABSTRACT

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic inflammatory, disabling disorder characterized by prominent eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus, leading to troublesome symptoms including dysphagia and food impaction. The natural history of EoE is poorly known, but it may lead to esophageal strictures. The therapeutic armamentarium is expected to grow in the near future, especially due to the availability of novel biological therapies targeting crucial inflammatory pathways of EoE.

Areas covered

In this review, we discuss the main clinical features and natural history of EoE, focusing on the current therapeutic strategies, as well as past and current trials investigating biologics for its treatment.

Expert opinion

Dupilumab has been the first approved biologic drug for the treatment of EoE; long-term studies assessing how it could change the natural history of EoE are awaited. Novel biological drugs or other molecules are currently under study and could change the current treatment algorithms in the near future. Proper drug positioning and long term ‘exit strategies’ are yet to be defined.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated disease of the esophagus and belongs to the spectrum of primary eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGID) [Citation1]. EoE is characterized by a dense epithelial eosinophilic infiltration and is, by definition, associated with clinical manifestations, which may vary with age, with dysphagia for solid food being the main symptom in adults [Citation2].

Once thought a rare disease, EoE is currently on the rise, being associated with a significant burden of disease, due to disease-related complications, including food impaction and esophageal narrowing, as well as quality of life impairment due to dysphagia, behavioral adaptations and symptom-specific anxiety [Citation3,Citation4]. Moreover, it may be associated with procedure-related complications, including esophageal perforation [Citation5,Citation6]. Indeed, along with its epidemiologic increase, the number of emergency visits for EoE have risen, with nearly half of patients presenting to the emergency department requiring endoscopy, and 40% foreign body removal [Citation6].

The knowledge of its natural history/evolution is of great importance, since it has considerable implications, such as the need for a long-term treatment with drugs or allergen-free diets and is the basis for the shared-decision making about its management with the patients and family members. Moreover, it is central for socioeconomic purposes to health care institutions and health- and life-insurances to estimate the burden of the disease with its direct and indirect costs, also for planning contrasting measures [Citation6].

Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) have represented one of the main treatment options for almost two decades, along with allergen-free diets and topical steroids with off-label formulations. In the last two years many therapeutically breakthroughs have been achieved. More precisely, the drug regulatory agencies have approved for adult patients ad hoc-devised swallowed topical steroids (STS), including oro-dispersible and oral suspension budesonide, and a monoclonal antibody targeting IL4/IL13, the latter being approved in adults and also adolescents (>11 years) and weighting more than 40 kilos, and more recently also in children aged one year and older in the United States [Citation7–12].

Though the introduction of novel and powerful drugs may deeply ameliorate the natural history of EoE and the quality of life, yet the positioning of biologics in the therapeutic algorithm remains poorly understood. Particularly, it is not known whether biologics should be prescribed upfront in most patients or only in refractory cases or in those presenting side effects to first line treatments, such as PPI, STS, or allergen-free diets [Citation13].

Moreover, new biological drugs targeting both the T helper (Th)-2 axis and fibrosis are being evaluated in clinical trials and these molecules might enlarge the therapeutical armamentarium to treat the disease in the upcoming years.

Starting with these premises, we revised in a narrative fashion the changing landscape of the evolution of EoE in the present era of biological therapies, with a critical appraisal of the current limitations and future promises of this targeted pharmacological approach.

1.1. Epidemiology and risk factors

According to epidemiological studies, the incidence and prevalence of EoE are increasing not only in the United States and Europe, but possibly also in Asia where EoE has been increasingly reported [Citation14–17]. Currently, the prevalence of EoE reaches 1 case per 1000 in the US and Europe [Citation18]. This epidemiologic surge cannot be accounted for by the increased awareness of the diagnosis alone and its recognition through endoscopy and histology [Citation19]. It probably reflects the second ‘epidemic of atopic diseases,’ being EoE the last step of progression of the atopic march [Citation20,Citation21]. The atopic march describes the temporal trajectory of development of type 2 inflammation, from atopic dermatitis, IgE-mediated food allergy, allergic asthma and rhinitis to EoE. Indeed, EoE shares several risk factors with other atopic disorders acting through genetic and epigenetic mechanisms, including among others environmental factors/exposures and genetic susceptibility, such as climate changes, exposure to pollutants, detergents, microbes and allergens, microbiome alterations, early life factors (e.g. cesarean section, use of antibiotic in the first years of life), epithelial barrier disruption (due to filaggrin mutations among others), and alterations in gene involved in Th2 inflammation [Citation21–23]. EoE as opposed to other atopic disorders such as IgE-mediated food allergy prevails in the male sex although the mechanistic interpretation of this finding is still elusive [Citation23].

Among the triggers of the disease, allergens seem to exert a relevant role. Both aero- and food allergens are involved. Respiratory allergens are thought to play a role since, they may initiate the disease or increase its severity; however, while seasonal variation in the diagnosis of EoE and of bolus impaction has been observed in some studies, this has not been confirmed in a meta-analysis [Citation24–26]. Food allergens trigger the disease, as allergen-free diets lead to disease remission in a substantial number of patients [Citation27]. The interplay between respiratory and food allergens is complex, since food allergens may also cross-react with respiratory allergens. Moreover, allergens administered as allergen-specific immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis (sublingual immunotherapy), or food allergy (oral or sublingual immunotherapy) may have a role in triggering some cases of EoE [Citation28]. Of note, subcutaneous immunotherapy, possibly bypassing the esophagus, doesn't seem to be burdened by these complications [Citation29].

The local acid environment due to gastroesophageal reflux disease has a role, as confirmed by the therapeutical effect of gastric acid secretion inhibition by PPI which can induce in adults a histological response in 49.6% and a clinical response in 60.8% of patients according to a recent meta-analysis [Citation30]. The effects of PPI seems to be more complex and not just limited to gastric acid inhibition, but also including anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting eosinophil trafficking to the esophagus through the reduction of adhesion molecules and of STAT6 mediated-eotaxin 3 expression [Citation31].

1.2. Clinical presentation

While in adults, the most frequent clinical symptom is dysphagia, i.e., a difficulty or discomfort in swallowing, of varying severity up to bolus impaction, in children clinical manifestations are much more heterogeneous, vary according to age, and they may include nonspecific symptoms such as heartburn, acid regurgitation, nausea, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, weight loss and failure to thrive, and may be filtered by the caregiver especially in infants and toddlers [Citation1,Citation19,Citation32,Citation33].

According to some evidence, the diagnostic delay of EoE seems to have been progressively reduced in the last decade, yet EoE may be untimely diagnosed, and early identification of at risk individuals who still do no present overt or major/classifying symptoms is key to prevent disease-related complications [Citation1,Citation34,Citation35].

In this instance, given the absence of a reliable noninvasive esophagus-specific diagnostic biomarker, the combination of suggestive clinical characteristics, such as dysphagia, even if not troublesome, and atopic comorbidity in male patients should prompt an endoscopic evaluation with biopsy, as suggested by a predictive model to identify high-risk individuals with a case-finding strategy [Citation36,Citation37].

1.3. Endoscopic and histopathological diagnosis

Endoscopy and histology are essential to diagnose EoE and to monitor the disease responsiveness to treatment in both children and adults, as required by guidelines [Citation38].

Overall, 83%–93% of patients present endoscopic abnormalities, including exudates (27%), edema (41%), mucosal fragility on the endoscope passage, furrows (48%), plaques, strictures (21%), rings (44%), which can be fixed (‘trachealization’) or transient (‘felinization’) and lastly a small-caliber esophagus [Citation39]. The prevalence of these alterations varies with age and disease duration, in children alterations linked to inflammation, such as edema and exudates, are more common than alterations linked to fibrosis and remodeling such as rings and strictures, which are common in adults [Citation33].

These endoscopic features have been incorporated into a validated grading system for EoE named EREFS, which stands for Edema, Rings, Exudates, Furrows, Stricture, and which predicts with high accuracy the diagnosis of EoE in both adults and children with an area under the curve of 0.93 in a receiver operating characteristic analysis [Citation33,Citation38,Citation40]. Despite its usefulness, endoscopy alone is not sufficient to make a diagnosis and assess disease activity, since in up to one fifth of patients, especially children, no endoscopic abnormalities are found [Citation33].

Given the patchy distribution of epithelial eosinophil infiltrates in EoE, several samples should be collected, usually six biopsies, from different portions of the esophagus, usually at least two, and they should be focused on areas characterized by mucosal endoscopic alterations 38. When no suggestive features of EoE are present at endoscopy, but clinical suspicion is high, biopsies should be randomly collected from all esophageal segments, upper, middle, and lower. To exclude involvement of the stomach and duodenum, these regions should also be biopsied, especially in children [Citation38]. Moreover, histological sampling should be performed after every therapeutic intervention, usually 6 to 12 weeks, to assess response, since clinical manifestations alone are unreliable in predicting disease activity [Citation38].

The most important histological feature for diagnosis is the intraepithelial eosinophil infiltrate expressed as the peak number of eosinophils counted in a high-power field (HPF). The diagnostic histological cutoff for eosinophil is 15/HPF and has a high accuracy in discriminating EoE from gastroesophageal reflux disease; it is also used to define histological remission (<15 eosinophil/HPF). Yet, in addition to eosinophils, other histologic features could be found, such as micro-abscesses, basal zone hyperplasia, dilated intercellular spaces, eosinophil surface layering, papillary elongation, and lamina propria fibrosis [Citation39,Citation40]. These features are incorporated in the EoE histological scoring system, HSS [Citation41].

While a diagnosis of EoE in the setting of a major classifying clinical presentation and diagnostic eosinophilic count can be made straightforwardly, yet a differential diagnosis should be considered, especially when the clinical presentation is not typical. Moreover, endoscopy and histology, together with anamnestic, clinical and laboratory data, could be useful to exclude celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, infections, and graft versus host disease among others.

2. Natural history of EoE

Two seminal observational studies have examined the natural history of EoE, i.e. in the absence of treatment, confirming the chronic nature of the disease and offering precious insights into its pathogenesis.

In one observational study following up 30 patients for a mean of 7.2 years, both primary features of EoE, eosinophilia and dysphagia were still detectable in almost all patients [Citation42]. Moreover, endoscopic appearance of the esophagus was also stable in the majority of patients. More precisely, although a certain degree of improvement of dysphagia was found in 36.7% of patients, in 36.7% it remained stable and in 23.3% it increased. Symptoms completely disappeared in one patient (3.4%). The symptomatic improvement in a subset of patients is likely attributable to esophageal dilation, which was required in one-third of patients, and to behavioral adaptions to dysphagia, including slow eating, food texture alteration and food avoidance, which occurred in almost half of patients. Histologically, sub-epithelial fibrosis was noticed in 87% of patients. Of note, in this study no cases of eosinophilic involvement of other tract of the gastrointestinal tract other than the esophagus and no esophageal cancer were observed.

According to another randomized study from the same center, in patients with remission after budesonide, placebo was given for one year. Eosinophil counts were then found to be increased and symptoms relapse was observed in 64% of them. Though not statistically significant an increase in sub-epithelial fibrosis was also detected [Citation43].

Moreover, in unrecognized disease, the prevalence of fibrotic features and strictures at endoscopy have been shown to increase in a time-dependent fashion from 17% to 70.8%, with a diagnostic delay of 0–2 years and >20 years respectively, thus correlating with the length of time of untreated disease [Citation44].

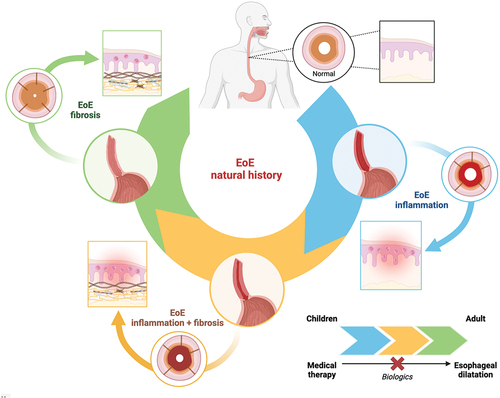

Collectively, these studies have clarified that although EoE is not associated with reduced survival and neoplastic disease, if unrecognized or left untreated, it may be associates with fibrotic complications, since the uncontrolled inflammation leads to structural alterations of the organ with fibrosis, stricture formation and impaired function and hence a reduced/impaired quality of life ().

Figure 1. The natural history of EoE is characterized by different stages, from an inflammatory one (rich in eosinophils, among other cellular types,), to a stage where inflammation is present together with fibrosis and finally to a mainly fibrotic stage (with a reduced inflammatory infiltrate), leading to stenosis and small caliper esophagus, as depicted in the Figure by means of different colors (upper part of the figure). The squared inset depicts histological changes, while the circular ones the sagittal and transversal view of the esophagus. The transition from one stage to the other is influenced by the duration of the disease and related diagnostic delay and age of the patient, and treatment, (lower part of the figure). According to the different stage of the disease, a specific treatment modality may be more appropriate from medical therapy to mechanical dilation. As shown, biological therapy can alter the progression.

3. Biological treatments

In the last decade, several biological therapies, mainly used to treat severe eosinophilic asthma, have been evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of EoE, including monoclonal antibodies targeting IgE, eosinophils, through the inhibition of interleukin (IL)-5 and IL5 receptor, and, more recently, of IL14/IL13 [Citation1]. Nonetheless, at present only dupilumab is approved for EoE treatment, since it achieved the coprimary endpoint of clinical and histological response in phase 2 and 3 randomized clinical trials, administered at the dosage of 300 mg every week, which is a schedule with more frequents dosages as compared to asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with polyposis and atopic dermatitis [Citation45,Citation46]. Clinical trials evaluating the effects of biological agents are summarized in .

Table 1. Biologic therapies investigated in clinical trials for the treatment of EoE.

Of note, drugs directly targeting eosinophils, such as anti-IL-5(R) mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab, and a monoclonal antibody targeting an inhibitory receptor on eosinophil and mast cells, i.e., Siglec 8, lirentelimab, have not been successful [Citation59,Citation60]. Despite determining a reduction in tissue eosinophilia, no significant clinical improvement, as assessed by the scales evaluating dysphagia, was observed. Several explanations can be put forward to account for the lack of clinical effects of these compounds. It is possible that these trials enrolled patients with a long history of disease and possibly a less inflammatory and more fibrotic phenotype, making patients less responsive to the effects of the drug targeting eosinophils. The dosage/schedule of the compound may have been inappropriately low and/or not tailored to tackle gastrointestinal inflammation. Of note, the dosage of most biological agents used to treat inflammatory bowel diseases is higher than that to treat other extra-gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases.

However, given the lack of a class effect of anti-eosinophils drugs, it is to speculate whether eosinophils are indeed the main target of the pathogenesis in EoE. Considering the clinic-histological response obtained with other therapies, such as PPI and allergen-free diets, which have shown anti-inflammatory effects targeting Th2 cells, together with the response to dupilumab, the role of eosinophils in EoE should be partially toned down. Despite being a phenotypic feature of the disease and contributing to its pathogenesis, eosinophils are probably not the main driver of the disease and secondarily attracted to the esophagus.

Moreover, more recently EoE-like variants devoid of eosinophils have been identified and characterized, suggesting that the spectrum of inflammatory conditions targeting the esophagus is more complex than previously thought and that eosinophilic infiltration is not a constant feature of EoE [Citation61].

3.1. Anti IL4/IL13

The initial evidence of efficacy of dupilumab in EoE derived from a multicenter multinational phase 2 RCT in 47 adult patients with active disease and at least two episodes of dysphagia per week which were refractory to PPI who were randomized to dupilumab 300 mg s.c. every week or placebo [Citation45]. The primary endpoint was the change form baseline to week 10 of the Straumann Dysphagia Instrument patient-reported outcome score. The follow-up included other 16 weeks. Document history or the presence of more than one type 2 comorbid atopic disease was among the inclusion criteria; whereas esophageal stricture unable to passed by an endoscope and esophageal dilatations at screening were exclusion criteria together with use of steroid within 3 weeks prior to screening. A mean of 3.0 reduction was observed as compared to 1.3 in the placebo-treated group (p < 0.03). Moreover, a mean 86.8%reduction in the peak of intraepithelial eosinophil count, a 68% improvement in the histologic scoring system and a 1.6 improvement in the endoscopic reference score were observed. Of note, a 18% increased distensibility as evaluated by a functional luminal imaging probe assessing impedance planimetry was found in patient treated with dupilumab. This represents a very important functional outcome. The treatment was also well tolerated.

Concomitantly, a retrospective multicenter US pediatric study evaluated the effects of dupilumab prescribed for other indications, i.e. asthma, atopic dermatitis, nasal polyposis, with a dosing every 2 weeks or monthly depending on the age and weight of the patient as compared with weekly dosing prescribed in the EoE phase 2 adult trial, or compassionate use for EoE. Out of 26 patients with endoscopy available before and after starting the drug, histologic improvement was found in 22 [Citation62]. Symptom scores improvement was found in 28 patients and symptom resolution in 24, allowing treatment reduction and diet expansion.

More recently, the results of a phase 3 multinational RCT confirmed the effects of dupilumab in a larger sample of patients, (n = 240), including adolescents, on symptomatic (as assessed by the Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire), histological, endoscopic, and molecular features of EoE up to 52 weeks [Citation46]. Notably, the presence of other comorbid atopic diseases was not required since in the Phase 2 study dupilumab proved effective also in patients without atopic comorbidities. Moreover, esophageal stricture unable to passed by an endoscope and esophageal dilatations at screening were not included among exclusion criteria. Of note, in this trial dupilumab 300 mg was also tested with the administration every other week that did not prove effective in attaining the clinical endpoint while attaining tissue eosinophil depletion.

In a recently published pre-specified subgroup analysis, dupilumab increased the proportion of patients achieving histological remission and clinical improvement regardless prior use of topical swallowed corticosteroids or inadequate, intolerance or contraindication to topical swallowed corticosteroids [Citation63].

The exact place of dupilumab in the management algorithm of EoE patients is however not yet defined. According to an expert opinion consensus, the use of dupilumab can be foreseen in several scenarios [Citation13].

The first scenario is to adopt this treatment as a ‘step-up’ therapy in patients refractory to current therapy, such as PPI and STS, due to persistent symptoms or esophageal inflammation or patients who present adverse effects, intolerance, or reduced adherence to those treatments. Consistently, the use of dupilumab could be foreseen in patients who frequently need rescue therapy, such as esophageal dilatations, oral systemic steroids, or amino acid formula.

Another therapeutic scenario is the use for dupilumab as a first therapy in some precise clinical settings. Given the systemic effects of dupilumab on type 2 inflammation on different epithelia, such as the skin and the respiratory system, the ideal patient would be that with moderate, persistent, or difficult to control comorbid atopic disorders, such as atopic dermatitis, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, asthma, and possibly also food allergy.

Indeed, food allergy improvement has been observed with dupilumab when administered for other indications, such as atopic dermatitis. The effect of dupilumab is being evaluated in clinical trials with oral immunotherapy for food allergy and it may have an adjunct role [Citation64,Citation65]. Mechanistically, dupilumab could exert beneficial effects through the inhibition of Th2 cell differentiation and IgE-class switching among other immune phenomena thus helping, together with food specific oral immunotherapy, to achieve food tolerance or at least increase the eliciting dose [Citation66].

In patients with a strong preference or rational to avoid topical steroids (such as diabetic patients, patients experiencing candidiasis, or when multiple steroid formulations to treat type 2 comorbidities are used in the same patients or there is a preference to limit the cumulative steroid dosage) or dietary restrictions (such as patients with several food triggers) an upfront treatment with dupilumab could be also considered.

Notably, dupilumab could be adopted in cases of severe fibro-stenotic disease. Indeed, the efficacy of dupilumab in this setting has been evaluated in a real-life retrospective study on 46 individuals who were treatment-refractory to standard therapies [Citation67]. With a median of 6 months of treatment, global symptom amelioration was found in 91% of patients together with tissue eosinophil reduction and endoscopy score improvement. Moreover, a significant increase in pre-dilation esophageal diameter, from 13.9 to 16 mm, was found, despite the stability in the number of strictures.

In addition to the beneficial effects of dupilumab, the relevance of the Th2-axis in EoE has been further and mechanistically confirmed in a murine model of EoE bearing several similarities with the human disease [Citation68]. More precisely, the knockout of IL13 receptor or in vivo IL13 neutralization protected the mouse from development of experimental EoE. This result strengthens the notion that IL13 is central in the pathogenesis of EoE. Indeed, it was previously observed that IL13 is overexpressed in the esophagus epithelium and induces EoE-like alterations, such as epithelial barrier disruption through CAPN14 induction, and the secretion of the eosinophil chemoattract eotaxin 3 [Citation69].

Overall, no major safety issues for dupilumab in EoE have been detected with the most frequent side-effects being arthralgia and injection-site reactions [Citation46]. Yet larger and real-life studies are needed to confirm this finding, particularly with reference to dupilumab-induced eosinophilia.

3.2. Anti IL13

A monoclonal antibody targeting IL-13 at two different dosages, administered as an intravenous bolus and subsequently subcutaneous, has been evaluated in a 12-week phase-2 RCT in 99 patients with active EoE [Citation52]. The drug significantly depleted tissue eosinophils and induced an amelioration in endoscopic and overall clinical features, but the improvement in dysphagia symptoms (frequency and severity) as assessed with a daily diary was not statistically significant. Of note, an amelioration in the patient-perceived and in the physician-assessed disease severity was observed. Interestingly, in a pre-specified subgroup analysis dealing with patient with refractory-disease, the improvement in the dysphagia score approached statistical significance (p = 0.054). These findings have been further strengthened in the extension phase of the trial reaching one year [Citation53].

3.3. Other agents

Several other agents are being evaluated in clinical trials, such as drug targeting the alarmin thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TLSP), which is a very interesting target due to the fact that it is a proximal epithelial inflammation driver. This drug has been recently approved for the treatment of severe asthma and is effective regardless of eosinophil counts [Citation70,Citation71].

Another interesting cellular target is KIT, which is a regulator of mast cell lineage and is targeted by a monoclonal antibody called barzolvolimab (NCT05774184). Mast cells in the esophagus are resident cells as opposed to eosinophils, and are key cellular targets since they may be involved in the earliest phases of EoE pathogenesis.

4. Conclusion

In the last years, many therapeutic breakthroughs have been obtained in EoE management, including, among others, the introduction for the first time of a biological therapy, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL4 and IL13, dupilumab, which has been shown to attain clinical and histological response in clinical trials, as opposed to therapies directly targeting eosinophils, such as anti IL5(R) monoclonal antibodies. Of note, these positive effects were not present only in cases with significant type 2 comorbidity and when significant fibrosis was absent. Indeed, dupilumab has been shown to improve esophageal distensibility, a very important functional outcome, and proved effective in real-life studies including cases with severe a fibrotic phenotype. These findings may hold a promise for a beneficial effect also in the preventive setting, which is a very important outcome considering the young age of patients with EoE, and also possibly in terms of concomitant drug-sparing effect. The treatment is generally well tolerated, and no major safety issues have been detected in clinical trials.

In case of disease remission, it is currently not known whether a dose reduction/interval increase in drug administration or even drug holiday is possible.

5. Expert opinion

Increasing data seem to corroborate the evidence that systemically active monoclonal antibodies may offer the conceptual benefit over topical steroids and in EoE this would translate into the advantage of targeting the transmural inflammatory process in addition to the epithelial one. This benefit in terms of remodeling may allow the prevention of disease progression and complications, including esophageal strictures and food impactions. Yet, the disease-modifying effect of monoclonal antibodies in the long term still needs formal demonstration in ad hoc designed clinical trials and in real life practice. Accordingly, trials aimed at specifically assessing functional outcomes, such as esophageal distensibility and distension-induced contractility, as assessed by functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP), in a prevention setting are highly awaited. Moreover, biological therapy targeting IL4/IL13 has been shown to be effective in targeting globally all the sites of type 2 inflammation, which is a very important effect especially in patients with EoE who are burdened by significant atopic comorbidity.

Future studies should also clarify whether biological therapies are effective in specific groups, such as treatment naïve patients, patient’s refractory to PPI or swallowed topical steroids and patients with concomitant primary EGID outside the esophagus.

Other important aspects are the identification of prognostic markers, which could possibly justify early treatment with biological therapy in certain patient groups to prevent complications, and predictive markers of response, since at present it is not possible to foresee whether a patient will respond to a given treatment. Moreover, even with current biological therapy, not all patients attain remission. In this instance, it is of importance to assess whether current therapies can also target EoE when type 2 is low/absent inflammation, such as in the pediatric setting EoE may be associated with esophagus atresia, celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease, or autism, and/or purely fibrotic phenotypes, where anti-fibrotic drugs, such as those used in primary pulmonary fibrosis are used, may have a role [Citation72].

Another unmet need is the absence of codified therapeutic algorithms, incorporating ‘step-up’ and ‘step-down’ approaches according to disease severity and response to therapeutic agents. At present, it is still unknown whether in the long-term administration of biological agents could be spaced maintaining disease remission and whether concomitant therapies be reduced and/or diet expanded. Another unknown aspect is whether biological treatment can be temporarily or even eventually withheld in some well controlled patients.

Moreover, at present it is not known how frequently patients undergoing biological therapy for EoE should be followed up endoscopically, although in an expert opinion document it is recommended after 5–6 months after dupilumab start and at every dosage modification and in case of worsening symptoms [Citation13].

Biological therapy with dupilumab is currently the most expensive among the available therapies for EoE. Cost effectiveness includes more than direct cost and measures the health benefit in terms of the number of quality-adjusted life years over a time length. Despite being costly, dupilumab with a dosing every two week has been shown to be cost-effective in the treatment severe and moderate atopic dermatitis, asthma, and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis with the usual economic threshold used in the U.S [Citation73–75]. Cost-effectiveness studies of the weekly dosing in EoE are currently not available and are thus largely awaited. Yet, even expensive treatments may have a role when they target significant functional outcomes.

However, given the current economic costs of biological therapy and the need for a long-term therapy in EoE, if not chronic, the introduction of biosimilar drugs may be of importance in terms of pharmacoeconomics. Yet, at present no such drug is approved for the treatment of EoE.

Article highlights

EoE is currently on the rise and is associated with a significant burden of disease, due to disease-related complications as well as quality of life impairment.

The knowledge of the natural history of EoE is of great importance, since it has considerable implications, such as the need for a long-term treatment, and is the basis for the shared-decision making about its management with the patients and family members.

If unrecognized or left untreated, EoE may be associates with fibrotic complications, since the uncontrolled inflammation leads to structural alterations of the organ with fibrosis.

Though the introduction of biologics may deeply ameliorate the natural history of EoE and the quality of life, yet their positioning in the therapeutic algorithm remains poorly understood.

The disease-modifying effect of biologics in the long term still needs formal demonstration in ad hoc designed clinical trials and in real-life practice.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors equally participated in the drafting of the manuscript or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and provided approval of the final submitted version. MV Lenti and A Di Sabatino reviewed the paper for important intellectual contents. MV Lenti and A Di Sabatino are the guarantors of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rossi CM, Lenti MV, Merli S, et al. Primary eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders and allergy: clinical and therapeutic implications. Clin Transl Allergy. 2022;12(5):e12146. doi: 10.1002/clt2.12146

- Straumann A, Aceves SS, Blanchard C, et al. Pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis: similarities and differences. Allergy. 2012;67(4):477–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02787.x

- Van Klink ML, Bredenoord AJ. Health-related quality of life in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2024;44(2):265–280. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2023.12.011

- Taft TH, Carlson DA, Simons M, et al. Esophageal hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(4):1133–1144. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.023

- Mukkada V, Falk GW, Eichinger CS, et al. Health-related quality of life and costs associated with eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(4):495–503.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.036

- Lam AY, Lee JK, Coward S, et al. Epidemiologic burden and projections for eosinophilic esophagitis-associated emergency department visits in the United States: 2009-2030. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(12):3041–3050.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.028

- Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/jorveza

- Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-eosinophilic-esophagitis-chronic-immune-disorder

- Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, Schlag C, et al.; International EOS-1 Study Group. Efficacy of budesonide orodispersible tablets as induction therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):74–86.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.025

- Straumann A, Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, et al.; International EOS-2 Study Group. Budesonide orodispersible tablets maintain remission in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(5):1672–1685.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.039

- Available from: https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2024/2024-01-25-19-30-00-2817342

- Available from: https://www.takeda.com/newsroom/newsreleases/2024/fda-approves-eohilia/

- Aceves SS, Dellon ES, Greenhawt M, et al. Clinical guidance for the use of dupilumab in eosinophilic esophagitis: a yardstick. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023;130(3):371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.12.014

- Roberts SE, Morrison-Rees S, Thapar N, et al. Incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis across Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2023. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12465

- Nagarajan KV, Krishnamurthy AN, Yelsangikar A, et al. Does eosinophilic esophagitis exist in India? Indian J Gastroenterol. 2023;42(2):286–291. doi: 10.1007/s12664-022-01313-9

- Kinoshita Y, Ishimura N, Oshima N, et al. Systematic review: eosinophilic esophagitis in Asian countries. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(27):8433–8440. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8433

- Sawada A, Imai T, Ihara Y, et al. Epidemiology And risk factors of eosinophilic esophagitis in japan: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024:S1542–3565(24)00447–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.035

- Straumann A. The natural history and complications of eosinophilic esophagitis. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(4):575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.09.004

- Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):319–332.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067

- Hill DA, Grundmeier RW, Ramos M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis is a late manifestation of the allergic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018 Sep;6(5):1528–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.010

- Paller AS, Spergel JM, Mina-Osorio P, et al. The atopic march and atopic multimorbidity: many trajectories, many pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.006

- Doyle AD, Masuda MY, Pyon GC, et al. Detergent exposure induces epithelial barrier dysfunction and eosinophilic inflammation in the esophagus. Allergy. 2023;78(1):192–201. doi: 10.1111/all.15457

- O’Shea KM, Aceves SS, Dellon ES, et al. Pathophysiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):333–345. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.065

- Wang FY, Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF. Is there a seasonal variation in the incidence or intensity of allergic eosinophilic esophagitis in newly diagnosed children? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(5):451–453. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000248019.16139.67

- Ekre M, Tytor J, Bove M, et al. Retrospective chart review: seasonal variation in incidence of bolus impaction is maintained and statistically significant in subgroups with atopy and eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2020;33(6):doaa013. doi: 10.1093/dote/doaa013

- Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, Redondo-González O, et al. Seasonal distribution of initial diagnosis and clinical recrudescence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2015 Dec;70(12):1640–1650. doi: 10.1111/all.12767

- Peterson KA, Byrne KR, Vinson LA, et al. Elemental diet induces histologic response in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):759–766. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.468

- Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Tenias JM. Relation between eosinophilic esophagitis and oral immunotherapy for food allergy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(6):624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.08.004

- Robey BS, Eluri S, Reed CC, et al. Subcutaneous immunotherapy in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(5):532–533.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.02.022

- Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, Molina-Infante J. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitor drugs for inducing clinical and histologic remission in patients with symptomatic esophageal eosinophilia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):13–22.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.041

- Franciosi JP, Mougey EB, Dellon ES, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis: history, mechanisms, efficacy, and future directions. J Asthma Allergy. 2022;15:281–302. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S274524

- Votto M, De Filippo M, Lenti MV, et al. Diet therapy in eosinophilic esophagitis. focus on a personalized approach. Front Pediatr. 2022;9:820192. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.820192

- Visaggi P, Savarino E, Sciume G, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical, endoscopic, histologic and therapeutic differences and similarities between children and adults. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1756284820980860. doi: 10.1177/1756284820980860

- Lenti MV, Savarino E, Mauro A, et al. Diagnostic delay and misdiagnosis in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53(12):1632–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2021.05.017

- Muir AB, Brown-Whitehorn T, Godwin B, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: early diagnosis is the key. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:391–399. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S175061

- Rossi CM, Lenti MV, Di Sabatino A. The need for a reliable non-invasive diagnostic biomarker for eosinophilic oesophagitis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(3):202–203. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00468-4

- Cotton CC, Betancourt R, Randall C, et al. A model using clinical and endoscopic characteristics identifies patients at risk for eosinophilic esophagitis according to updated diagnostic guidelines. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(9):1824–34.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.068

- Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis. Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022–1033.e10.

- Kim HP, Vance RB, Shaheen NJ, et al. The prevalence and diagnostic utility of endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(9):988–996.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.019

- Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62(4):489–495. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817

- Collins MH, Martin LJ, Alexander ES, et al. Newly developed and validated eosinophilic esophagitis histology scoring system and evidence that it outperforms peak eosinophil count for disease diagnosis and monitoring. Dis Esophagus. 2016;30:1–8. doi: 10.1111/dote.12470

- Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, et al. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(6):1660–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.024

- Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(5):400–9.e. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.017

- Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1230–6.e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015

- Hirano I, Dellon ES, Hamilton JD, et al. Efficacy of dupilumab in a phase 2 randomized trial of adults with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):111–122.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.042

- Rothenberg ME, Dellon ES, Collins MH, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab up to 52 weeks in adults and adolescents with eosinophilic oesophagitis (LIBERTY EoE TREET study): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(11):990–1004. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00204-2

- Straumann A, Conus S, Grzonka P, et al. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody treatment (mepolizumab) in active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gut. 2010;59(1):21–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.178558

- Assa’ad AH, Gupta SK, Collins MH, et al. An antibody against IL-5 reduces numbers of esophageal intraepithelial eosinophils in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1593–1604. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.044

- Dellon ES, Peterson KA, Mitlyng BL, et al. Mepolizumab for treatment of adolescents and adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Gut. 2023;72(10):1828–1837. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-330337

- Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, et al. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):456–63, 463.e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.044

- Rothenberg ME, Wen T, Greenberg A, et al. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(2):500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.049

- Hirano I, Collins MH, Assouline-Dayan Y, et al.; HEROES Study Group. RPC4046, a monoclonal antibody against IL13, reduces histologic and endoscopic activity in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(3):592–603.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.051

- Dellon ES, Collins MH, Rothenberg ME, et al. Long-term efficacy and tolerability of rpc4046 in an open-label extension trial of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(3):473–483.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.036

- Dellon ES, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, et al. Dupilumab in adults and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2317–2330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2205982

- Straumann A, Bussmann C, Conus S, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha (infliximab) therapy for severe adult eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2):425–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.012

- Loizou D, Enav B, Komlodi-Pasztor E, et al. A pilot study of omalizumab in eosinophilic esophagitis. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0113483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113483

- Clayton F, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with IgG4 and not mediated by IgE. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(3):602–609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.036

- Dellone E. S446 results from KRYPTOS, a phase 2/3 study of lirentelimab (AK002) In adults and adolescents with EoE. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Oct;117(10S):e316–e317. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000858424.48968.ad

- Rossi CM, Lenti MV, Di Sabatino A. Toning down the role of eosinophils in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2023:gutjnl-2023–329864. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329864

- Available from: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2022/update-on-messina-phase-iii-trial.html

- Greuter T, Straumann A, Fernandez-Marrero Y, et al. A multicenter long-term cohort study of eosinophilic esophagitis variants and their progression to eosinophilic esophagitis over time. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2024 Apr 1;15(4):e00664. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000664

- Spergel BL, Ruffner MA, Godwin BC, et al. Improvement in eosinophilic esophagitis when using dupilumab for other indications or compassionate use. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(5):589–593. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.01.019

- Bredenoord AJ, Dellon ES, Hirano I, et al. Dupilumab demonstrated efficacy and was well tolerated regardless of prior use of swallowed topical corticosteroids in adolescent and adult patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis: a subgroup analysis of the phase 3 LIBERTY EoE TREET study. Gut. 2023 Dec 16. gutjnl-2023-330220.

- Rial MJ, Barroso B, Sastre J. Dupilumab for treatment of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(2):673–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.07.027

- Sindher SB, Fiocchi A, Zuberbier T, et al. The role of biologics in the treatment of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12(3):562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.11.032

- Fiocchi A, Vickery BP, Wood RA. The use of biologics in food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021 Aug;51(8):1006–1018. doi: 10.1111/cea.13897

- Lee CJ, Dellon ES, Terrault NA. Real-world efficacy of dupilumab in severe, treatment-refractory, and fibrostenotic patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;3(6):S1542–3565(23)00665–1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.07.020

- Avlas S, Shani G, Rhone N, et al. Epithelial cell-expressed type II IL-4 receptor mediates eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2023;78(2):464–476. doi: 10.1111/all.15510

- Davis BP, Stucke EM, Khorki ME, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis–linked calpain 14 is an IL-13–induced protease that mediates esophageal epithelial barrier impairment. JCI Insight. 2016;1(4):e86355. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86355

- Menzies-Gow A, Corren J, Bourdin A, et al. Tezepelumab in adults and adolescents with severe, uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(19):1800–1809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034975

- Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-maintenance-treatment-severe-asthma

- Ruffner MA, Cianferoni A. Phenotypes and endotypes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(3):233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.12.011

- Zimmermann M, Rind D, Chapman R, et al. Economic evaluation of dupilumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a cost-utility analysis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(7):750–756.

- Kuznik A, Bégo-Le-Bagousse G, Eckert L, et al. Economic evaluation of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(4):493–505. doi: 10.1007/s13555-017-0201-6

- Yong M, Wu YQ, Howlett J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing dupilumab and aspirin desensitization therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11(12):1626–1636. doi: 10.1002/alr.22865