Abstract

Agricultural landscapes in Ethiopia have undergone unprecedented changes. The direction of change, however, is unsustainable as manifested in land degradation, biodiversity loss, and low agricultural productivity. The objective of this study is to examine the patterns and trends of agricultural landscape development and responses of the local people within the framework of the dynamics of demography, socioeconomic conditions, politics, and natural resources in the Chencha and Arbaminch areas, Southern Ethiopia, during the last century. Information on cultivated and grazing land areas was acquired by satellite image interpretation. Interviews and group discussions provided important information on agricultural land use systems. A review and an analysis of secondary sources and documents of past studies were also used for trend analysis as a baseline and a supplement to oral history. The results show that cultivated land was expanded by 39% from 1973 until 2006, but per capita farming land holdings decreased enormously. In the same period of time, grassland shrank by 69% thus causing a significant decrease in livestock. Cultivated land scarcity can mostly be related to demographic pressure, which was exacerbated by government policy, land tenure, and the nature of subsistence agriculture. The farmers, however, were resourceful and developed skills over millennia to cope with the problems associated with population density and scarce resources. However, these traditional land use activities and land management practices have been deteriorating recently. Land use planners and environmental managers should take local knowledge and innovation into account in order to make sound decisions for the future.

Introduction

Agriculture is the source of livelihood of 84% of the total population (74 million) who live in rural areas in Ethiopia (PCC, Citation2008). It also accounts for 50% of the GDP, 90% of exports and 85% of total employment (MEDaC, Citation2008). Agricultural landscapes in Ethiopia underwent unprecedented changes (particularly during the last century) due to the dynamics of political, demographic, socio-economic, and cultural factors.

The extent of available agricultural land in Ethiopia has enormously increased, particularly during the last century. From 1900 until 1989, about 4.7 million households required arable land for cultivation (Hurni, Citation2007). Since 1900 about 23 M ha of forest land were cleared, mainly driven by a conversion to arable farmland (EFAP, Citation1993). More recent satellite image analysis of the period between 1973 and 1990 for the entire country also revealed that about 24,543 km2 of forest (2.14% of the total forest resources of the country) was cleared, mainly because of the demand for acreage (Reusing, Citation1998). Moreover, a considerable portion of grassland was also shifted to cultivated land (Benin, Ehui, & Pender, Citation2006). In the period between 1961 and 2002, areas fit for the cultivation of cereals, pulses, and oil seeds increased from 5,440,000 ha to 7,812,000 ha, which amounts to about a 44% increase land for cultivation (Mulat, Fantu, & Tadelle, Citation2004). Various case studies in different parts of the country also report an increase of plough land. A case study in North Western Ethiopia demonstrated an increase of acreage from 39% to 77% in the period from 1957 to 1995 (Zeleke & Hurni, Citation2001). In South West Ethiopia, another study also revealed an increase of cultivated land from 27% to 63% in three different but adjacent sites from 1957 until 1993 (Reid et al., Citation2000). On the other hand, in some case studies it was reported that the change to cultivated land has been very minor since the 1980s because there is no more suitable land left that can be converted (Tekle & Hedlund, Citation2000). This also implies that the upper limit of possible arable farmland has been reached and that no further expansion can occur in some regions of Ethiopia.

Notwithstanding the general increase of land for cultivation in the country, per capita land holdings are declining. The national per capita land holding rate ranged to maximally 3 ha and below in 1960. Before the end of the last century, approximately 39% of farming households worked less than 0.5 ha and about 89% worked less than 2 ha. Only 0.75% of the farmers cultivated more than 5 ha (CSA, Citation2006; Rahmato, Citation2009). The decrease of farmland per capita is attributed to a rapid population growth, a lack of off-farm employment opportunities, and a lack of rural-urban migration due to economic stagnation (Mulat et al., Citation2004; Samuel, Citation2006). The total population of Ethiopia increased from about 12 million in 1900 to about 26 million in 1970 and over 77 million in 2007 (Central Statistical Authority (CSA), Citation2006; Sahilu, Citation2003). Likewise, the rural population has grown from about 12 million in 1900 to 64 million in 2007 (Central Statistical Authority [CSA], Citation2006; Hurni, Citation2007). With the current growth rate (nearly 3%), the rural population is expected to reach about 85 million by 2018, which will also bring about a growing number of land-short and landless rural residents.

Farmland scarcity has already caused farmers to cultivate marginal land areas and fragile ecosystems. Moreover, it is also possibly a reason for the reduction and abandonment of fallowing practices and crop rotation. This, in turn, resulted in a decline in soil fertility and an increase in soil erosion. The estimated annual soil loss in Ethiopia amounts to 1.5 billion tons, of which 50% erodes from croplands where soil loss by water may be as high as 296 tons ha−1 year−1 on steep slopes and soil nutrient losses may be as high as 80 kilogrammes of Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium per ha and year or more. In general, half of Ethiopian highlands are moderately to severely eroded (FAO, Citation1986; Hurni, Citation1993; Lemenih, Karltun, & Olsson, Citation2005). The problem of soil erosion in Ethiopia is one of the serious threats to agricultural development and overall food insecurity during the last 50 years (Sonneveld, Citation2002).

Ethiopia is one of the largest food aid receivers in the world. From 1945 to 1954 Ethiopia was self-sufficient and an exporter of food crops, mainly cereals. During this period, Ethiopia exported about 154,000 tons of cereals given the shortage of food grain after the Second World War (Rahmato, Citation2009). However, the situation reversed and Ethiopia started to import food crops as of the second half of the 1950s. Subsequently, the World Food Programme began to operate and expedite food aid to Ethiopia in 1965. Since then Ethiopia has remained one of the largest food aid recipients. Between 1985 and 2000, Ethiopia received about 700,000 tons per annum, which represents about 10% of the national food grain production. The largest amount of food aid, 26% of the total domestic food production, was received in 1984 due to the worst drought that affected over 14 million people, 22% of the total population of the country. Food aid has increased by an average growth rate of about 2.5% per year from 1980 to 2001 (Clay, Molla, & Habtewold, Citation1999; Devereux, Citation2000; Mulat et al., Citation2004).

In order to overcome food insecurity problems and to maintain natural resources, various plans, programmes, and policies have been formulated and implemented over the last century by different governments that have ruled Ethiopia, during the Imperial period from the 1920s–1960s, during the phase of the military government – the Derg – from the 1970s–1980s, and during the incumbent government from the 1990s–present. Despite sporadic positive effects, the various governments were neither able to meet food demands nor to maintain the environment (McCann, Citation1995; Mulat et al., Citation2004; Rahmato, Citation2009).

Nevertheless, different localities have developed and practised various traditional mechanisms to cope with the challenges of population pressure, environmental degradation, and food insecurity (low productivity) over a long period of time. One of the cases in point is the study areas Chencha and Arbaminch in Southern Ethiopia. The area is characterized by a high population density (within a range between 300 and 400 persons per km2) and the land holding rate was less than half a hectare in the 1960s, which has been surpassed by the carrying capacity (the capacity of a given land to produce food and materials so as to meet the needs of the people who are using this specific land) since then (Rahmato, Citation2009). The farmers, however, are resourceful, gathered a wide range of experience, and developed skills over millennia to cope with the problems associated with population density and scarce resources (Jackson, Citation1972; Jackson, Rulvaney, & Forster, Citation1969). They have used an intensive cultivation system, various natural resource management practices, and cultivated diversified crops. ‘Demographic’, i.e. drought tolerant plants such as Ensete ventricosum were used, which make the area one of the least affected by the recurrent droughts in Ethiopia. As Rahmato (Citation2009, p. 35) has succinctly put it: if these intensive agricultural techniques and discrete innovations had not been practised in the area over centuries, the people would not have survived. However, this agricultural system and these mechanisms against adverse conditions have not gained attention and appreciation by planners and researchers. Hence, there are only very few attempts to investigate and study the state of agriculture land use, land use systems, and the resourcefulness of the farmers in the area (Jackson, Citation1972; Olmstead, Citation1975).

Furthermore, there are very few attempts to study the dynamics of agricultural land use and the forces that drive Ethiopia in general, and the study area in particular, on a long term basis. An historical investigation of agricultural landscape development which took place during the last century is therefore necessary to provide valuable information for decision-makers, land use planners, and environmental managers who need to make sound decisions. During the past century in particular, there has been a very significant development of agricultural landscapes. During this period, the three aforementioned regimes emerged and deployed different ideologies and differing agricultural land utilization and land policies. The regime changes were radical and the impacts were reflected in resource utilization and management. Furthermore, population growth was also very rapid during these phases. The last century was therefore a period of dynamic socio-economic and political changes which played an immense role in modifying agricultural landscapes (McCann, Citation1995; Rahmato, Citation2009).

In light of the earlier discussion, the objective of this study is to examine the patterns and trends of agricultural landscape development and the responses of the people within the framework of the dynamics of demography, socio-economic conditions, politics, and natural resources in the Chencha and Arbaminch areas in Southern Ethiopia during the last century. The specific objectives are: (1) a determination of the extent and trends of changes of agricultural land use systems and driving forces, and (2) an assessment of strategies and approaches of the local people in response to agricultural landscape dynamics.

Methods of the study

Description of the study area

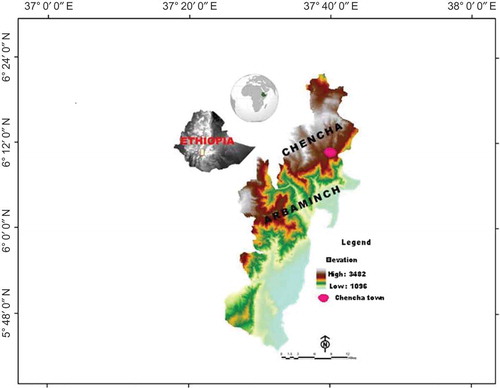

Chencha (6° 15ʹ N, 37° 34ʹ E) and Arbaminch (6° 2ʹ N, 37° 33ʹ E) are located in the Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Regional State (). They are situated about 480 km southwest of Addis Ababa and bounded on the east by Lake Abaya and Lake Chamo. The topography is marked by a series of undulating and rugged landscapes, which include, from east to west, the Rift Valley Plain, the escarpment with incised valleys, and high plateaus, which are topped by hills and mountains. The lower part of the study area lies in the plain of the Rift Valley while the middle and upper parts are situated in the southwestern highlands of Ethiopia. The altitude ranges within a short distance of only 20 km from 1100 m in the Rift Valley to 2300 m above sea level (a.s.l.) in the highlands.

Figure 1. Location of the study area. To view this figure in colour, please see the online version of the journal.

For Arbaminch (1200 m a.s.l.) a mean annual precipitation of 782 mm and for Chencha (2700 m a.s.l.) a mean annual precipitation of 1392 mm were measured from 1970 to 2006. The rainfall pattern is of a bimodal type. The first rainy season, locally known as gabba, occurs from March to June and the peak reaches 148 mm in April for Arbaminch and 185.4 mm for Chencha. The second season, locally known as silla, occurs from August to November. The maximum mean monthly temperature in Chencha is 15°C in February and the minimum temperature is 13°C in October. The average annual temperature of Arbaminch is 23°C. There the maximum mean monthly temperature is 26°C, which occurs in March and the lowest temperatures are recorded from December to February.

The population of Chencha was 134,531 and that of Arbaminch was 247,915 in 2005 (Central Statistical Authority (CSA), Citation2006). Population density is estimated about 368 and 205 persons per square kilometre in Chencha and Arbaminch, respectively. Olmstead (Citation1975) estimated that 5000 to 35,000 people lived in Chencha area at the end of nineteenth century. The area is in the centre of the region Gamo Gofa, which is divided into 40 dere (small discrete political units). Gamo is the dominant ethnic group who inhibited in the area. Arthur et al. (Citation2010) identified a 1 km2 open-air hilltop settlements, garrison sites with deep 3 m trenches for defence and mountain-top fortification. They have also found an assemblage of earthenware ceramics, a clay bead, modified flakes, and other materials. They made an excavated test that dated about 6400 ca. B.P. (calibrated, before present) which suggests the period of time that the local people have lived in their current location.

Cultivating crops and livestock rearing have been the dominant economic activities since the beginning of settlement in the area (Arthur et al., Citation2010; Cartledge, Citation1995). The farming systems in the highlands are marked by small-scale agriculture entirely dependent on rainfall. In the lowlands, small-scale irrigation is also practised for growing bananas and other crops. The two methods of tillage used in the area are conducted with the hoe plough and the ox plough, the former being dominant. The instrument used for tilling by hand is locally known as tsolle. It has two-headed, pronged hoes with a wooden haft. Tilling by hand is carried out by the household head and/or by a group. Raising livestock is also an integral part of the economy.

Methods

In this study, data from primary and secondary sources were collected. Primary data were generated from satellite images, interviews, and group discussions while secondary data that were pertinent to the study were gathered from books, journals, travel accounts, and records from government and non-government institutions.

Satellite image analysis

A time series was created (acquired) from satellite image analysis. Landsat MSS, TM, and ETM+ satellite images of the years 1973, 1986, and 2006 were used in conjunction with field surveys. These images were geometrically registered to the 1:50,000 scale topographic map of the area. Agricultural land use was identified from the images by a supervised classification method. Agricultural land includes cultivated lands and grasslands, which are mainly used for grazing. Cultivated land is used for annual and perennial crops. It includes areas currently under crops, fallow land, land under preparation, and homestead land. Data for ground referring (ground truth) were employed from extensive field observations and interviews.

Household interviews

To cover the different agro-ecological zones, areas that belong to the highlands (Doko Mesho), middle altitudes (Dorze Belle), and lower elevations (Chano Chelba) were selected. From the lists of the households in the kebeles (the lowest tier of the administrative units of 1000–5000 people), a total of 120 household heads were randomly selected. The interviews were carried out with the help of assistants. The assistants were college graduates who knew the local languages. Trainings for assistants were carried out conveying ways of establishing contact, methods for conducting interviews, interview procedures, and cultural issues. Interviews were conducted by going to individual households in the morning and during the afternoon, which are usually appropriate times for the farmers since neither an agricultural activity nor any other activities in which the household head was involved in took place at these time of the day. Interviews were also held outdoors as long as the people were willing to respond to the questions. If the informant was unwilling to give information then she or he was asked to propose someone who would be willing to be an informant. The estimated time to conduct an interview with one household head was about 2 to 2.5 hours.

Group discussions

Group discussion is an important technique to check and refine the data, which was acquired by structured interviews of household individuals and key informant interviews. It is useful in order to rule out exaggeration or underestimation of the situations. Likewise, the household interviews and the research area were divided into three segments including the Chano Chelba, the Dorze Belle, and the Dokomesho areas. Ten informants were selected from each area. Participants in the discussions were elders (mainly over 50 years of age, both sexes) who could remember and convey past events of agriculture land use. Discussions were carried out based on a check lists.

Results

Cultivated land changes during the last four decades

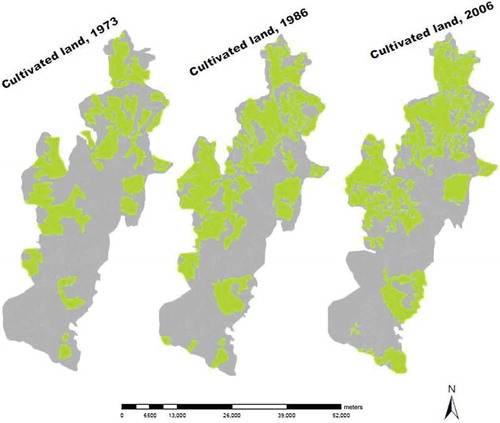

The results of satellite image interpretation show that cultivated land amounted to 57%, 64%, and 67% in 1973, 1986, and 2006, respectively (). The results indicate that cultivated land has increased by 39% from 1973 to 2006. However, there was no continuous linear increase over time from 1973 to 2006. The small increase in the last four decades was the result of the limited area of land which could be cultivated. This confirms the results of studies that were carried out in Northern and Central Ethiopia (Amsalu, Citation2006; Gebrelibanos & Assen, Citation2013; Tekle & Hedlund, Citation2000). On the other hand, a large part of the increase of cultivated land in the former period was partly attributed to the radical change of the government. Particularly, the change from the Imperial to the Derg regimes in 1974 resulted in the conversion of a large proportion of forest land into cultivated land. Similarly, at the time of the change of the Derg to EPRDF in 1991, an overwhelming area of shrub land was converted to cultivated land. These were the periods when there were loose government controls. A similar finding was also reported by Dessie and Christiansson (Citation2008), showing that a large proportion of forest and shrub land in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia was converted to cultivated land during these changes of government.

Figure 2. Cultivated land of the study area. To view this figure in colour, please see the online version of the journal.

A high increase rate of cultivated land was reported in the lowland area of the Rift Valley, for example, an increase of about 65% between 1973 and 1986 and an increase of about 21% between 1986 and 2006. This was mainly attributed to the recent movement of many people from the intensively populated highlands to areas for settlement and cultivation in the Rift Valley. Similar settlement and cultivation of adjacent lowlands was also reported for different parts of Ethiopia (Reid et al., Citation2000). In contrast, the lowest change in the amount of cultivated land was found in the highland (dega) regions with an increase of 28% from 1973 until 2006. This is due to the obvious fact that most of the land which is suitable for cultivation was previously brought under cultivation in these areas. In some case, land which used for cultivation in the past (1973 and 1986) was abandoned recently as a result of soil erosion.

In 1973 about 8% of all cultivated land acreage in the highlands was situated on steep slopes. Until 2006 it increased to 14% of the total cultivated land areas. First, cultivation land was mainly situated on the less inclined foot slope areas. It was then expanded to the plain lands in the valley areas of the highlands. The steep slopes only came under cultivation during the last few decades. This has been confirmed by discussions with the informants. However it is important to note that steep slope land of the Dorze Belle area has been under cultivation with terraces over the last 800 years (Assefa, Citation2012).

Dynamics of household cultivated land areas and fragmentation since the 1960s

Household holdings of cultivated land have decreased over time despite an increase of the extent of acreage in the highlands. About 30% of interviewed farmers pointed out that their land holdings had decreased by 75% when compared to the Derg regime period, whereas 45% of the interviewed farmers mentioned a decrease of 50%, and 15% of the respondents stated that their holdings had not changed.

The declining trend of cultivated landholdings can also be depicted in a comparative study of the present survey with past surveys. The survey, which was conducted by four members of the Oxford University Expedition in 1968 (Jackson et al., Citation1969) significantly overlaps with present study sample sites and could therefore be used as a reference for comparison. According to the Oxford study, cultivated land per household in the highlands was about 1.6 ha on average. The present survey revealed that about two thirds of the interviewed farmers of the highlands own land below 0.5 ha per household. This pattern is similar to a survey of Chencha woreda. According to an agricultural survey of the country, 56% of the households of Chencha woreda cultivate areas with sizes below half a hectare (CSA, Citation2001/2002). However, holdings vary according to the different study sites as shown in . In the lowlands, the households worked >0.5 ha on average while in the middle altitudes about 0.47 ha were cultivated.

Table 1. Landholdings of households.

According to Jackson (Citation1972), the average number of fields per household in the highlands amounted to 4.6 in the 1960s. Some farmers possessed up to 20 farm plots. But more than 50% of the farmers owned less than 4 fields. However, the fragmentation of agricultural land is an important characteristic of the highlands, because fields at different topographical positions were considered to be more advantageous than consolidated land since it allows farmers to grow different types of crops according to different site conditions. Moreover, farmers who owned consolidated cultivated land were locally labelled as poor farmers (Jackson, Citation1972). The present survey also reported the large number of fragmented landholdings. The average number of fields in fragmented cultivated land areas is estimated at about 5.0 in the upper highlands, 4.6 in the middle highlands, and 3.7 in the lowlands. The maximum walking distance from the house to the farthest field is about 1 hour.

The large number of fields in the fragmented land areas in the highlands is a result of several factors including long periods of settlement, high population growth, and land inheritance. For example, farmers partitioned their miniscule land plots to their sons when they married and plots are distributed among the sons after the death of the head of the families. A farmer divided his land into equal parts for all sons, for one son or for several sons according to preference. Land distributions during the Derg regime and current grazing land conversion to arable land have also contributed to fragmentation. Last but not the least, the subjective value of fragmented land over consolidated land by farmers is also another contributing factor to fragmentation. However, it is now also argued that land fragmentation is not convenient for the application of structural soil and water conservation and it also impedes the ox plough.

Dynamics of cropping patterns and crop varieties

In the 1960s, the principal cultivated crops, in terms of area coverage and food importance, included barley, enset, beans, peas, and wheat in the highlands and maize, cotton, and bananas in the lowlands (Jackson, Citation1972). The present survey identified barley, wheat, and enset as the principal crops in the highlands and bananas, lemons, papayas, mangos, maize, and cotton in the lowlands . Land allocations for different crops, cropping patterns, and crop varieties have undergone unprecedented changes owing to various social and economic reasons.

Table 2. Land use and allocation by surveyed households.

Enset is the centre of agricultural production in the study area. Sometime in the remote past, the enset plant was first domesticated and used as a staple food in Southern Ethiopia in general and in the study area in particular (Cartledge, Citation1995; Westphal, Citation1975). However, the extension of the area devoted to enset is declining. In the 1960s, the area used to grow enset reached about 16% of the total cultivated land of the highlands (Jackson et al., Citation1969). At present, enset acreage comprises about 10% of total acreage. According to surveyed households, the main reasons for the decrease of enset cultivation are a decline of soil fertility due to low amounts of manure application, a scarcity of land which forced farmers to cultivate crops with short growth periods, and diseases. Other enset growing regions of Southern Ethiopia, including Sidama, Hadyia, and Wollayita, have also experienced a similar decline of enset cultivation due to land shortages and a substitution of enset by cash crops (Tsegaye & Struik, Citation2002).

Barley is one of the major, long-time crops in the highland area. In the 1960s, the cultivated land allotted to grow barley was estimated at about 39% of the total cultivated land (Jackson, Citation1972). Currently, it is still grown on a large proportion of the land (23% of total acreage). Wheat is another prevailing crop that presently grows on about 21% of the total cultivated land. In the past, it was rarely cultivated and the total production was therefore insignificant (Jackson et al., Citation1969). This can be attributed to a widely spread disease which prohibited its cultivation.

At present, bananas are grown on three-fourths of the total cultivated land acreage in the lowlands. According to an informant, bananas were introduced in the lowland area in the early 1960s. At that time, however, the principal cultivated crop was maize. Other plants such as papaya, lemon, and cotton were also grown. Generally, cropping patterns have changed since the 1990s due to the enormous economic significance of bananas. This caused farmers to replace other crops such as maize and cotton with banana.

Crop species diversity and variety diversity in the area have also changed during the few last decades. There are many new crops which have been introduced to the area at different periods of time. Among others, the main new crops were apple, teff, sisal, rice, and different varieties of barley, wheat, and potato. Teff was introduced at the beginning of the twentieth century when the area was incorporated into Ethiopia. The cultivation of wheat was initiated in the area at the middle of the twentieth century. Moreover, rice was imposed by the government for cultivation in the lowlands in the 1980s. However, the cultivation of rice was abandoned when the cultivation of bananas started to dominate the area. Apples were another new crop introduced to the highlands in the 1950s as stated above. On the other hand, area coverage and the frequency of some crops (biodiversity and richness of plants) have remarkably decreased and some are under a threat of disappearance. Maize (Zea mays) and sweet potato (Ipomoea batata) are disappearing today in the lowland area (Belachew, Citation2002).

Cropping patterns have also undergone significant changes. Previously, the cultivation of different types of crops on one field (multiple cropping) had become common practice of farmers to minimize risks and to fulfil all food requirements from one’s own land. But present cropping patterns are shifting towards monocropping. However, the replacement of indigenous as well as varieties of crops during a shift to monocropping has several negative biodiversity effects and implications. Moreover, this development has also caused a significant shift in the diet of the people. In the recent past, people on the lowlands were entirely dependent on maize, which they produced in the area. But at present, they buy food items such as teff, barley, etc. from the highlands and other parts of the region. Further investigations are required on dietary changes in the area.

Dynamics of livestock and implications

The number and types of livestock in the investigation area are shown in . The average level of livestock holdings per surveyed household amounted to 2.59 TLU (Tropical Livestock Unit; conversion rate is given under ). The average TLU per household in Doko Mesho in the highlands was 1.6, in Dorze Belle at a mid-altitude was 2.1, and in Chano Chelba in the lowlands was 3.8. The proportion of different livestock varieties in the total research area includes cattle (46.3%), sheep (36.7%), goats (11.6%), donkeys (2.2%), mules (1.5%), and horses (1.7%). Among the livestock varieties, cattle are dominant in the middle and low altitudes. Sheep constitute a large proportion in the highlands and 95% of goats are found in the lowlands and at the middle altitudes.

Table 3. Total number of livestock owned by all sampled households.

With regard to trends of livestock holding, about 50% of respondents in the highlands, 43% of respondents at the middle altitudes, and 16% of respondents in the lowlands stated that livestock holding is declining. In contrast, there is a slight increase in the number of sheep in the highlands owing to the comparatively low feeding requirements of sheep, as described by informants.

Despite the various cattle feed sources, the majority of respondents (87%) in the highlands stated that shortage of cattle feed is the main cause for the decrease of the number of cattle. The mentioned fodder shortage is mainly caused by a conversion of large grassland areas to farmland. This is also attested by satellite image interpretation, which revealed that about 37% of grasslands in the highlands were converted to cultivated land from 1973 to 2006. Large grassland areas were already converted to cultivated land in the 1960s as revealed by Jackson et al. (Citation1969). In particular, private grazing land was totally abandoned as witnessed by the surveyed households. A major part of the communal grazing land was then converted to cultivated land. Today, further sources of past grazing land, such as grazing inside forests and the use of enset leaves, are also deteriorating. This is a result of a decline of enset cultivation and the domination of eucalyptus trees on forestland at steep slopes which hinders the growth of grass. Furthermore, irrigation of grazing land entirely ceased when grasslands were converted to arable farmland (Jackson et al., Citation1969), which also implies the deterioration of the availability and quality of feed resources in the area.

One of the impacts of declining livestock is reflected in the availability of manure. For centuries, farmers used manure to replace nutrients that are removed via continuous crop cultivation. Manure is the most important source of nutrient replacement since farmers cannot afford chemical fertilizers. According to the responses of the informants, livestock holding has decreased on average in the region under investigation by about 37%, which is equivalent to 109 TLU. On the average, about 3.2 tons of manure is produced by 1 TLU (ILICA, 1981 quoted by Amare, Citation1981). The average nutrient content of 1 kg of manure on small scale farms in Ethiopia constitutes: 21.3 g K, 18.3 g N, 16.4 g Ca, 5.6 g Mg, 4.5 g P, 10,776 mg Fe, 777 mg Mn, 92 mg Zn, and 24 mg Cu. Accordingly, in the region under investigation an average annual loss of about 7400 kg K, 6400 kg N, 5700 kg Ca, 2150 kg Mg, 1600 kg P, 3700 kg Fe, 27 kg Mn, 32 kg Zn, and 2 kg Cu results from the extraction of crops mentioned above. But the constituents of the nutrients vary depending on the availability of feed as testified by experiment (Lupwayi, Girma, & Haque, Citation2000). Thus, this estimate needs to be validated by further research regarding the availability and quality of feeding. However, the results show that the decrease of animals has significant impacts on the amount of nutrients in the soil, which has ripple effects. The missing nutrients must be replaced by inorganic fertilizers to maintain fertility and to obtain good yields. However, farmers cannot afford the price of inorganic fertilizers, as mentioned above. Nevertheless, high soil fertility is only maintained when organic matter is added. This dilemma implies that keeping livestock saves hard currency which otherwise has to be spent for the import of inorganic fertilizers from abroad. Otherwise, the structure of soil, which is important for infiltration and for various chemical reactions, will deteriorate significantly. Soil degradation will probably increase during the next years and decades and result in a significant abandonment of cultivated land (Cartledge, Citation1995).

Trends and determinants of agricultural production

Farmers consider agricultural production to be ‘sufficient’ if enough is produced to feed family members throughout the year and to also sell some of the produced goods to cover expenses for taxes, school, medicine, clothing, and the like. Among the respondents in the highlands, 76% reported that the profits generated from the farmlands are not sufficient for the whole year, about 21% answered that they produce sufficient yields, while the remaining respondents reported that there is no clear trend in agricultural production. The insufficient agricultural production reported by the majority of the farmers is in line with the South Ethiopia Regional report on livelihood and food security (South Nation Nationality and People Region of Ethiopia [SNNPR], Citation2005). It categorizes the whole area of the Chencha woreda to be under ‘the margin of food security’. A sale of crops by most farmers is induced by the prospect of getting other food items, and not due to surplus products they have produced. In contrast, the situation is different in the lowlands as the overwhelming majority of respondents (95%) reported that they are self-sufficient in feeding their families and affording their yearly expenses. This is due to the prevailing cash crop production of irrigated bananas, which have a high income per unit area turnover. This is also confirmed in the livelihood and food security report of the South Ethiopia Region (SNNPR, Citation2005).

As to the trend of agricultural productivity in the highlands, about 82% responded that there is a decline of productivity compared to the last 40 years, whereas 11% responded that there is no decline, and 7% said there is no change. With regard to the rate of decline of agricultural production, about 45% responded that there is a high rate of decline, 10% reported a medium decline, and 27% a low rate of decline. The remaining interviewees could not trace the rate of decline because of irregularities in the trend. However, all informants observed an increase in the production of some recently introduced crop varieties such as barley compared to the local indigenous varieties when the right amount of fertilizers is applied and when there is no unusually low rainfall. But the application of fertilizers and improved seed are constrained by the low-income level of the farmers.

Farmers reported different multiple determinants that affect agricultural productivity in the area as indicated in . The most frequently cited factors are: scarcity of cultivated land (97%), soil fertility decline (87%), grazing land shortage (86%), soil erosion (81%), low fertilizer input (56%), erratic rainfall (57%), lack of improved seed (53%), pests and diseases (17%), and inadequate extension services (23%). The problem of land scarcity is very acute because existing land is shared and distributed to the children. In the 1960s, Olmstead (Citation1975) and Jackson (Citation1972) already mentioned a high population density in the area. The scarcity of available acreage has increased since then as a result of the high population growth in the area. Moreover, a lack of off-farm employment keeps the people heavily dependent on the cultivation of their farmlands. This is also a factor that contributes to the enormous pressure on the land. The situation is aggravated by land tenure systems and governmental agricultural policies that banned the selling and buying of land. The only way to get access to land is by sharecropping and leasing.

Table 4. Major constraints of agricultural production in the highland as perceived by surveyed households*.

Discussion and conclusions

The agricultural system of the study area has undergone a significant change during the last century. The extension of farmland has increased considerably, but per capita acreage declined. Similarly, available grassland, the main feeding resource of livestock, has decreased and caused a huge decrease in livestock. Nevertheless, farmers are resourceful. They gathered a wide range of experience and developed skills to cope with the problems associated with increasing population density and scarce resources. Growing several varieties of crops (crop diversification) was one of the salient features of the agriculture practices in the area over a long period of time. In the lowlands and at middle altitudes, Belachew (Citation2002) identified about 133 different plant species of which 48 species are used as food for humans. Jackson et al. (Citation1969) also reported a wide range of grains, cereals, root crops, vegetables, and stimulant crops that grow in different agro-ecological regions. The varieties of crop species is also high in the area, for instance Samberg, Shennan, and Zavaleta (Citation2010) recognized about 65 varieties of barley while Olmstead (Citation1975) observed about 34 varieties of enset. Local farmers also reported that some of the varieties of barley were locally domesticated. Enset is endemic to the area (Cartledge, Citation1995).

Farmers use various methods to grow these varieties of crops. Intercropping (growing of different crops on the same field in the same season) is one of the systems. For instance farmers grow barley together with kolto, beans, and peas. They also grow enset with taro, coffee, and cabbages. Intercropping has been practised in the area due to the various advantages that overweigh monocropping systems in small holding agriculture. The main benefit is that self-sufficiency can be achieved with farming different types of crops.

Farmers have also gathered long-term experience in the efficient use of the garden areas close to their homesteads (Belachew, Citation2002). Except for a small field in front of a house, which is barren or covered by grass in some cases, all other land is used to grow crops. The main crop, which grows close to the homesteads, is enset. As a result, it is not uncommon to find enset groves surrounding the houses in the highlands. Other crops such as peppers, cabbages, onions, garlic, taro, tobacco, pumpkins, and kale are also grown in the gardens. These plants are usually grown intermixed with the early stage of enset. Additionally, some trees are also grown close to homesteads. Most recently, apple trees are grown in the highlands around the homesteads. In the lowlands, people used to grow bananas, vegetables, mangos, and papayas around their homes. Growing crops in gardens has various advantages, for example to control, expand, and use available resources efficiently. Moreover, by growing different trees near their homes and in the fields, the farmers benefit from various advantages of tree cultivation such as fertility input, additional food and fodder resources, shade, wood supplies, and ecological soil and water conservation.

The cultivation of enset is a central farming activity due to its various economic and ecological significances (Cartledge, Citation1995; Olmstead, Citation1975). Furthermore, enset is also known for its high starch content, yielding 20 million calories per hectare (Olmstead, Citation1975). High yields per unit area of enset also partially contribute to the support of a dense population in the southern region. The other salient feature of enset is its drought resistance as a result of its deep roots and its capacity to store water in tuberous roots and pseudo-stems. For this reason, it is known as a plant against drought (Shack, Citation1966) and the area is one of the least affected by drought in Ethiopia.

Livestock tending is the main integral part of the agriculture system in the area. It has played an important economic and ecological role in the area for a long period of time. Cattle supply milk, butter, and meat. They are the most common source of animal protein. Livestock is the main source of cash used to pay taxes, to buy clothes, and to meet other major expenses. Livestock also serves as a type of insurance during crop failures, when farmers sell animals and use the money to buy food. More importantly, livestock is the major source of manure.

For centuries, farmers used manure, crop rotation, and fallowing to compensate the extraction of nutrients by growing of crops. Manure is the most important source of plant nutrients in the area. The application of crop residues and compost are also other practices applied to maintain the fertility of the soil. Traditional terracing has also been used to protect the soil from erosion. The application of chemical fertilizers is very limited because of the costs. Farmers cannot afford chemical fertilizers.

Presently, these traditional land use activities and land management practices are deteriorating. The people have been forced to cultivate steep slopes, wetlands, and grasslands. The practice of fallowing and the application of manure are declining. The diversification of crops has also been reduced and in some cases has been replaced by monocropping because of the economic value of crops such as bananas and apples. Some indigenous and local crop varieties are becoming scarce. The farming communities have now recognized the impact of the deterioration of agricultural landscapes which obviously results in a decline of agricultural production. Thus, the direction of the changes of agricultural landscapes in the area is unsustainable as manifested in land degradation, biodiversity loss, and low agricultural productivity.

To sum up, the investigation revealed the paramount implications of the locally developed, long-term sustainable land use systems and land management techniques in providing food and material resources to the inhabitants over centuries. Thus, land use planners and environmental managers have to modify their policies to alter the present dynamics of agricultural land use systems. In particular, they have to be aware of vital local knowledge and the skills of the farmers as well as the ability of the latter to accept innovations. It is most important that local people are intensely involved in all development activities, including resource management, planning, and the implementation of changes. Participation is a precondition to re-establish sustainable land use systems and management practices.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all farmers and the enumerators who took part in the research. We would also like to thank the German Research Foundation (DFG) for financial support to the study. Thanks are also due to Eileen Kuecuekkaraca for proof reading the manuscript.

References

- Amare, G. (1981). Stability of mountain ecosystem with special reference to Ethiopia. Mountain Research Development, 4, 39–44.

- Amsalu, A. (2006). Caring for the land. Best practice in soil and water conservation in Beressa watershed, highlands of Ethiopia (Tropical Resource Management Papers, No. 76). Wageningen: Wageningen University.

- Arthur, W. K., Arthur, W. J., Curtis, C. M., Lakew, B., Lesur-Gebremariam, J., & Ethiopia, Y. (2010). Fire on the mountain: Dignity and prestige in the history and archaeology of the Borada highlands in Southern Ethiopia the SSA archaeological record. The Magazine of the Society for American Archaeology, 10, 17–21.

- Assefa, E. (2012). Landscape dynamics and sustainable land management in southern Ethiopia ( PhD dissertation). Kiel University, Kiel.

- Belachew, W. (2002). Study of useful plants in and around home gardens in the vicinity Arbaminch, southern Ethiopia: Ethnobotanic approach ( MSc thesis). Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

- Benin, S., Ehui, S., & Pender, J. (2006). Policies for livestock development in the Ethiopian highlands. In J. Pender, F. Simeon, & S. Ehui (Eds.), Strategies for sustainable land management in the East African highlands (pp. 55–76). Washington, DC: International Food Policy research Institute (IFPRI).

- Cartledge, D. (1995). Taming the mountain: Human ecology, indigenous knowledge, and sustainable resource management in the Doko Gamo society of Ethiopia ( Doctoral dissertation). University of Florida, Gainesville.

- Central Statistical Authority (CSA). (2001/2002). Ethiopian agricultural sample enumeration, 2001/02. Results for Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region. In Statistical report on area and production of crops. Addis Ababa: Author.

- Central Statistical Authority (CSA). (2006). Ethiopia statistical abstract. Addis Ababa: Author.

- Clay, D. C., Molla, D., & Habtewold, D. (1999). Food aid targeting in Ethiopia: A study of who needs it and who gets it. Food Policy, 24, 391–409. doi:10.1016/S0306-9192(99)00030-5

- Dessie, G., & Christiansson, C. (2008). Forest decline and its causes in the south-central rift valley of Ethiopia: Human impact over a one hundred year perspective. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 37, 263–271. doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2008)37[263:FDAICI]2.0.CO;2

- Devereux, S. (2000). Food insecurity in Ethiopia. A Discussion Paper for DFID. Sussex: Institute of Development Studies.

- Ethiopian Forestry Action Program (EFAP). (1993). Ethiopian forestry action program: The challenge for development (Vol. II). Addis Ababa: Ministry of Natural Resources Development and Environmental Protection.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (1986). Ethiopian highlands reclamation study, Ethiopia. Final Report. Rome: Author.

- Gebrelibanos, T., & Assen, M. (2013). Land use/land cover dynamics and their driving forces in the hirmi watershed and its adjacent agro-ecosystem, highlands of northern Ethiopia. Journal of Land Use Science. doi:10.1080/1747423X.2013.845614

- Hurni, H. (1993). Land degradation, famine, and land resource scenarios in Ethiopia. In D. Pimentel (Ed.), World soil erosion and conservation (pp. 27–61). Cambridge: Cambridge Press.

- Hurni, H. (2007). Challenges for sustainable rural development in Ethiopia. Addis Abeba: Faculty of Technology, Addis Abeba University.

- Jackson, R. T. (1972). Land use and settlement in Gamu Gofa, Ethiopia. Department of Geography Makerere University Kampala Occasional Paper No. 17, Kampala.

- Jackson, R. T., Rulvaney, T. R., & Forster, J. (1969). Report of the Oxford University expedition to the Gamu highlands of southern Ethiopia. Oxford: Oxford University.

- Lemenih, M., Karltun, E., & Olsson, M. (2005). Assessing soil chemical and physical property responses to deforestation and subsequent cultivation in smallholders farming system in Ethiopia. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 105, 373–386. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2004.01.046

- Lupwayi, N. Z., Girma, M., & Haque, I. (2000). Plant nutrient contents of cattle manures from small-scale farms and experimental stations in the Ethiopian highlands. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 78, 57–63. doi:10.1016/S0167-8809(99)00113-9

- McCann, J. (1995). People of the plow. An agricultural history of Ethiopia, 1800–1990. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- MEDaC. (2008). Survey of the Ethiopian economy: Review of post-reform developments (1992/93–1997/98). Addis Ababa: Author.

- Mulat, D., Fantu, G., & Tadelle, F. (2004). Agriculture development in Ethiopia: Are there alternatives of food aid? Unpublished Paper, Addis Ababa.

- Olmstead, J. (1975). Agricultural land and social stratification in the Gamu highlands of Southern Ethiopia. In H. G. Marcus (Ed.), Conference on Ethiopian studies (pp. 223–234). East Lansing: African Studies Center, Michigan State University.

- PCC. (2008). Summary and statistical report of the 2007 population and housing census. Population size by age and sex. Addis Ababa: Population Census Commission, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Printed by United Nations Population Fund.

- Rahmato, D. (2009). The peasant and the state. Studies in Agrarian changes in Ethiopia 950s–2000s. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Press.

- Reid, R. S., Kruska, R. L., Muthui, N., Taye, A., Wotton, S., Wilson, C. J., & Mulatu, W. (2000). Land-use and land-cover dynamics in response to changes in climatic, biological and socio-political forces: The case of Southwestern Ethiopia. Landscape Ecology, 15, 339–355. doi:10.1023/A:1008177712995

- Reusing, M. (1998). Monitoring of natural high forest resources in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Sahilu, H. (2003). Population, environment and development. In A. Gedion (Ed.), Environment and environmental changes in Ethiopia (pp. 16–22). Addis Ababa: Forum for Social Studies.

- Samberg, L., Shennan, C., & Zavaleta, S. E. (2010). Human and environmental factors affect patterns of crop diversity in an Ethiopian highland agro-ecosystem. The Professional Geographer, 62, 395–408. doi:10.1080/00330124.2010.483641

- Samuel, G. (2006, March 20–22). Land, land policy and smallholder agriculture in Ethiopia: Options and scenarios. Paper prepared for the Future Agricultures Consortium meeting at the Institute of Development Studies, Addis Ababa.

- Shack, W. (1966). The Gurage: A people of the Enset Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sonneveld, B. G. J. S. (2002). Land under pressure: The impact of water erosion on food production in Ethiopia. Maastricht: Shaker Publishing.

- South Nation Nationality and People Region of Ethiopia (SNNPR). (2005). A report on regional livelihoods baseline study. Addis Ababa: Author.

- Tekle, K., & Hedlund, L. (2000). Land cover changes between 1958 and 1986 in Kalu district, Southern Wello, Ethiopia. Mountain Research and Development, 20, 42–51. doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2000)020[0042:LCCBAI]2.0.CO;2

- Tsegaye, A., & Struik, P. G. (2002). Analysis of Enset (Ensete ventricosum) indigenous production methods and farm-based biodiversity in major enset-growing regions of Southern Ethiopia. Experimental Agriculture, 38, 291–315. doi:10.1017/S0014479702003046

- Westphal, E. (1975). Agricultural systems in Ethiopia. Agricultural Research Report No. 826. Wageningen: Centre for Agriculture Publications.

- Zeleke, G., & Hurni, H. (2001). Implications of land use and land cover dynamics for mountain resource degradation in the Northwestern Ethiopian highlands. Mountain Research and Development, 21, 184–191. doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2001)021[0184:IOLUAL]2.0.CO;2