ABSTRACT

This study sought to understand why and how the area of irrigated agriculture in Janos County, in northwestern Chihuahua, Mexico, has tripled since 1987. Expansion of agricultural frontiers has often been attributed to state policies and programs or von Thünian land-rent dynamics. Here, a political ecology approach relying on qualitative interviews with landowners was used to understand the drivers and patterns of conversion from native rangeland to crops. Results show that socioeconomic patterns of agricultural frontier expansion evolved over time, with different drivers at different phases. State policies, especially the land reform, were initially important for settling the agriculture frontier in small farms. Subsequently, economic differentiation, intensification, and growth of existing farms drove expansion. Since 2010, expansion has been driven by investment-oriented land purchases by absentee owners and larger-than-family farms. The Janos case details what may be common but underappreciated temporal dynamics at agricultural frontiers.

Introduction

The term and concept of the frontier are old and fraught, often described as a transitional space between ordered and chaotic, legible and unknowable, socially productive and unused. The term is also discursive, employed specifically to ‘legitimize processes of “freeing” land for extraction, exclusion and dispossession’ (Eilenberg, Citation2014, p. 161). In the last two decades, a multitude of studies has examined the entanglement of state development, security objectives or neoliberal policies, and transnational capital in the proliferation of ‘land grabs’ and other large-scale land conversions at resource frontiers (Borras, Kay, Gómez, & Wilkinson, Citation2012; Hall, Citation2013; Tsing, Citation2003). Like other resource frontiers, agricultural frontiers are sites of land use/land cover change (LULCC), where agricultural production is initiated for the first time or experiences significant changes in production technology or output intensity. Rather than focus on large-scale land grabs, this study examines an agricultural frontier expanding through a more gradual, mundane process, wherein small-scale commodity farmers achieve LULCC with state assistance and as a consequence of undergoing agrarian change. Hall and Caviglia-Harris (Citation2013) described this process as an agricultural ‘industrial life cycle’ of proliferation, development, and consolidation.

Much of the recent literature on agricultural frontiers in Latin America looks at forest clearing for ranching and farming (e.g. Barona, Ramankutty, Hyman, & Coomes, Citation2010; Brannstrom, Citation2009; Hecht, Citation1993; Jepson, Citation2006; Morton et al., Citation2006), and tropical forests were the source of most agricultural expansion in the 1980s and 1990s (Baldi, Guerschman, & Paruelo, Citation2006; Gibbs et al., Citation2010; Hannah, Carr, & Lankerani, Citation1995). Less attention has been paid to the conversion of native rangeland (woodlands, shrublands, and grasslands) to crops. While the conversion of grazed rangeland to crops has sometimes been labeled as mere ‘agricultural intensification’ (e.g. Piquer-Rodríguez et al., Citation2018), many scholars describe the transition as the expansion of an agricultural frontier (e.g. Brannstrom, Citation2009; Jepson, Citation2006; Spera, Galford, Coe, Macedo, & Mustard, Citation2016). I also consider cattle-to-crops conversion to constitute an agricultural frontier, especially when – as is true for my study area in Chihuahua, Mexico – the land previously grazed was native rangeland and not cleared forest or sown pasture; the change entails altered land cover, production technology, ecological impacts, and increased output intensity (yield or value per hectare).

Conversion of rangeland to crop agriculture has ecological impacts, including soil erosion and loss of soil organic matter (Burke et al., Citation1989; Paul, Paustian, Elliott, & Cole, Citation1996), altered hydrology (Gordon, Peterson, & Bennett, Citation2008), release of soil carbon (Deng, Zhu, Tang, & Shangguan, Citation2016; Guo & Gifford, Citation2002), and loss of wildlife habitat (Lindenmayer & Fischer, Citation2013; Wilcove, Rothstein, Dubow, Phillips, & Losos, Citation1998). In Chihuahua, conversion of rangeland – especially Chihuahuan Desert grassland – to crops has destroyed (federally protected) black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) colonies (Ceballos et al., Citation2010) and threatens numerous migratory grassland bird species (Pool, Panjabi, Macias-Duarte, & Solhjem, Citation2014). Cropland expansion also contributes to aquifer depletion due to widespread reliance on groundwater for irrigation (Scott, Citation2011).

Agricultural frontier expansion is often attributed either to land rents or state action (policies, programs, or other interventions), or both (Jepson, Citation2006; Jepson, Brannstrom, & Filippi, Citation2010; Walker, Citation2004). Problematically, LULCC studies often focus on large-scale drivers of land use, overlooking the people actually changing the landscape (Hersperger, Gennaio, Verburg, & Bürgi, Citation2010). Identifying how LULCC is carried out and who wins and who loses in the process is valuable for improving policy but requires people-centered research methods.

This study seeks to understand how the drivers and socioeconomic characteristics of agricultural expansion change as the expansion progresses over time, using Janos County (municipio) as a case study. Located in the northwest corner of Chihuahua (), Janos is primarily composed of native Chihuahuan Desert grassland and shrubland long grazed by cattle. Crop farming there is both relatively recent and conducted by multiple social groups operating under multiple forms of land tenure. As a result, drivers of LULCC can be elucidated by tracking agricultural expansion backward to when most of the land was first put to the plow and by comparing social groups and forms of land tenure. Results from this study suggest that the actors and economic opportunities involved in expanding agricultural frontiers shift over time, shaped by hallmarks of capitalist agriculture highlighted in theories of agrarian change: economic differentiation, consolidation of land ownership, and expansion of successful firms.

The paper is organized as follows: First, I present dominant theoretical perspectives on the drivers of agricultural frontier expansion, followed by the historical context of land ownership and use in Mexico generally and more specifically in Janos County. Then, after describing the research approach and methods, I present the socioeconomic history of agricultural expansion in Janos from 1950 to 2017, as described in qualitative interviews with landowners and local stakeholders. I then discuss how the Janos case is characterized by multiple theoretical explanations of agricultural expansion at different historic phases, offering insights on how agricultural expansion may proceed elsewhere.

Theorizing agricultural frontiers

Land-rent (or ‘bid-rent’) approaches to understanding agricultural frontiers draw on von Thünen’s model where land use and land valuation are determined largely by distance to markets (Walker, Citation2004; Walker et al., Citation2009). According to the theory, land values increase as the functional distance to market decreases, such as by the construction of a new road or railroad. Land-rent theory is readily incorporated into LULCC models because transportation distance and infrastructure are easily quantified (e.g. Weinhold & Reis, Citation2008). That said, land-rent alone is insufficient to explain LULCC in part because it occludes the political economics behind the infrastructure and commercial activities that shape von Thünian distances (Bockstael, Citation1996; Jepson, Citation2006).

State programs and policies are also theorized as causal mechanisms of LULCC (e.g. Geist & Lambin, Citation2002; Hecht, Citation1985; Lambin, Geist, & Lepers, Citation2003; Lambin et al., Citation2001). Commonly cited drivers of expanding agricultural frontiers include: national policies promoting colonization of ‘underutilized’ land (e.g. Hall, Citation1989; Hecht, Citation1985), land titling programs (e.g. Gould, Carter, & Shrestha, Citation2006), and financial incentives such as commodity price supports, tax breaks, and subsidized credit or inputs (e.g. Heimlich, Citation1986; Pacheco, Citation2006). Such policies and programs have the explanatory advantage of being presumably temporally discreet and spatially uniform, helpful traits for generalization and extrapolation; in reality, their effects are heterogeneous, requiring additional explanation to account for variable LULCC outcomes.

In Mexico, the state played a strong role in expanding agricultural frontiers during the twentieth century. The conversion of native forest to agriculture on the Yucatan Peninsula was driven largely by state colonization programs in the 1970s (Bray & Klepeis, Citation2005; Klepeis & Turner, Citation2001; and see Dobler-Morales; Chowdhury & Schmook; and Kelly, all this issue). More recently, direct agricultural subsidy payments have been positively correlated with agricultural expansion by ejidatarios (Schmook & Vance, Citation2009), but not by private landowners (Ellis, Montero, Gómez, Porter-Bolland, & Ellis, Citation2017). In Mexico’s arid north, expansion of high-intensity commodity agriculture prior to the 1970s was often driven by large-scale governmental irrigation schemes (Hicks, Citation1967; Lewis, Citation2002; Walsh, Citation2008; Whiteford, Bernal, Diaz-Cisneros, & Valtierra-Pacheco, Citation1998). Agricultural expansion outside of such irrigation projects was less predictable, sometimes driven by incremental improvements to land or irrigation (e.g. Doolittle, Citation1988) or private funding of new groundwater irrigation (Scott & Shah, Citation2004), including by MennoniteFootnote1 farmers (Pool et al., Citation2014).

The centrality of irrigation in agricultural expansion in northern Mexico highlights that it takes more than land to establish crops. Land tenure policy does shape land use and may be particularly important at a frontier, incentivizing land modification, consolidation, and investment (Alston, Libecap, & Schneider, Citation1996; Angelsen, Citation1999; Gould et al., Citation2006; Southgate, Citation1990). In order to benefit from land, however, users must also leverage other means of production, including labor, financial capital, and a method of delivering products to market. Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003) termed the ability to derive benefits from land access, which includes more than simple land control. People, organizations, and institutions interact to structure access to land in what are called ‘access regimes’ (Jepson et al., Citation2010), which may benefit some groups or individuals over others.

Agricultural frontier expansion may be initially driven by in-migration but continued subsequently due largely to the expansion of existing farms. Researchers have identified one pattern in which state colonization policies and production supports generate a wave of migration that expands an agricultural frontier at a particular point in time, while in following years favorable market conditions foster capital investments that propel operational expansion, pushing the frontier outward (e.g. Hecht, Citation2005; Jepson et al., Citation2010; Pacheco, Citation2006). In a second pattern, migration to a frontier may be ‘spontaneous,’ while subsequent land titling and agrarian change propel capital investments, intensification, and expansion (e.g. Gould et al., Citation2006; Humphries, Citation1998; Southgate, Citation1990). The first pattern is initiated by explicit state activity, while the second by varying push-pull factors including land-rent factors like improved transportation networks. In both patterns, colonization of new frontiers is performed by poor people looking for cheap land with which to create a livelihood, while subsequent intensification of production (generally via capital investments) and consolidation of landholding are carried out by firms with better access to the means of production. This evolution of production appears common regardless of the initial drivers of expansion, suggesting a fundamental socioeconomic pattern of agricultural expansion.

Scholars of agrarian change have been documenting intensification of production and consolidation of landholding by commodity-producing farmers at least since Karl Kautsky’s and Vladimir Lenin’s pioneering work more than a century ago. A hallmark of agrarian change is economic differentiation, wherein farmers who were economically homogenous separate along an economic spectrum (e.g. Akram-Lodhi & Kay, Citation2010a; Bernstein, Citation2010). On one end of the spectrum are large-scale farmers who invested profits in buying more land and intensifying production through higher-value crops and improved technology (e.g. hybrid seeds, specialized farm machinery, chemical usage); on the other end are landless laborers who sold their farms due to economic shortfalls, a process sometimes called ‘dispossession by differentiation’ (Araghi, Citation2009). The process of agrarian change is ubiquitous in market-oriented farming and may explain the two-stage frontier expansion described above, in that profitable farmers expand their area of production beyond that cleared during in-migration. The case of agricultural expansion in Janos, Chihuahua illustrates these dynamics in action.

Land and agriculture in Mexico

Mexico’s political history was central to establishing conditions for agricultural expansion in Janos. Mexico’s revolution (1910–1920) was largely motivated by vastly unequal land ownership and rampant foreign investment (Hart, Citation2002; Wasserman, Citation1984). Afterward, the new federal government established a national land reform process to make landownership more egalitarian. Individuals and firms were limited in the number of hectares they could own, depending on use, with the excess subject to expropriation (Assies, Citation2008; Sanderson, Citation1981). Ranch size was limited to the land necessary to support 500 cattle. The land reform (1915–1992) and its official termination have been widely analyzed as important drivers of land use and management – a quintessential policy driver of LULCC (Bonilla-Moheno, Aide, & Clark, Citation2012; Cornelius & Myhre, Citation1998b; Ellis et al., Citation2017; Farley, Ojeda-Revah, Atkinson, & Eaton-González, Citation2012; Klooster, Citation2003; Vasquez Castillo, Citation2004).

The most notable product of land reform was the ejido, where non-saleable land-use rights – not private titles – were distributed to communities of named individuals (usually men, see Deere & Leon, Citation2001) with voting rights on community leadership and land management. Ejidos were established through government expropriation of land with redistribution to petitioners or through land occupations with subsequent legal retitling. Although ‘patterns of land use in individual ejidos are so varied that it is difficult to generalize’ (DeWalt & Rees, Citation1994, p. 47), most ejidos were established for agricultural production, either crops or livestock or both. Ejidos are generally divided into three categories of land: residential plots; areas designated for common use and benefit sharing, such as forested or grazing areas (called uso común); and parcelized areas for individual use, such as farming (called parcelas)(Téllez, Citation1993). By the end of land reform in 1992, there were more than 27,000 ejidos accounting for more than half the country’s land base (Assies, Citation2008).

Access to land for agriculture does boost rural incomes (Finan, Sadoulet, & De Janvry, Citation2005), but agricultural profits for ejidatarios (ejido members) have been limited. Agricultural development and incomes were hampered by poor land quality, small parcels, the initial poverty of land recipients, and irregular and insufficient government support programs (Assies, Citation2008; Cornelius & Myhre, Citation1998a; De Janvry, Gordillo, & Sadoulet, Citation1997). Ejido land could not be used as collateral, which limited access to farm credit to cumbersome state financial institutions, notably the Banco Nacional de Crédito Rural (BANRURAL) (De Janvry et al., Citation1997; Myhre, Citation1998). Wage labor has become increasingly vital for sustaining livelihoods (Cornelius & Myhre, Citation1998b; De Janvry & Sadoulet, Citation2001).

Beginning with the Salinas administration (1988–1994), Mexico undertook a far-reaching liberalization of the economy – including land tenure policy – which has frequently been described as a turn toward ‘neoliberalism’ (e.g. Liverman & Vilas, Citation2006). In the 1990s, Mexico joined the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), formally ended BANRURAL, began privatizing water and electricity systems, reduced or ended price supports and state purchasing programs for agricultural products (notably the Compañía Nacional de Subsistencias Populares, CONASUPO), and established a process to allow privatization of ejido land (Assies, Citation2008; Liverman & Vilas, Citation2006; Otero, Citation1996; Yunez–Naude, Citation2003). These reforms increased production costs and reduced crop prices, precipitating sales and renting out of ejido farm fields and increasing emigration to the US (De Janvry, Emerick, Gonzalez-Navarro, & Sadoulet, Citation2015; Lewis, Citation2002; Luers, Naylor, & Matson, Citation2006; Valsecchi, Citation2014). The percentage of Mexico’s citizens living in the US surged from 3.5% in 1980 to 5.2% in 1990 to 10.2% in 2005 (Hanson & McIntosh, Citation2010).

Research methods

Site description

The northern Mexican state of Chihuahua is mostly the Chihuahuan Desert, an arid to semi-arid rangeland in the rain shadow of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Chihuahua is Mexico’s largest state but is sparsely populated, and livestock grazing is the dominant land use. Of Mexico’s 32 states, Chihuahua had the third-largest cattle herd and the second-largest number of ‘improved breed’ cattle in 2014 (INEGI, Citation2015).

During the twentieth century, crop agriculture was expanded across northern Mexico through strong governmental support for irrigation works and national land reform (e.g. Aboites Aguilar, Citation2012; Rochin, Citation1985; Sanderson, Citation1981), and also by private Mennonite agriculture in the Cuauhtémoc area (Sawatzky, Citation1971). Agriculture in Chihuahua has expanded faster than in Mexico as a whole, especially irrigated agriculture. Chihuahua’s expansion of agriculture from 1980–2015 is equal to 36% of Mexico’s total increase, and 90% of the increase in irrigated farmland (https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/[Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria Y Pesquera – SIAP]). In 1950, Chihuahua had 305,659 ha devoted to its four most-planted crops (in descending order): maize, cotton, beans, and wheat; nationally, the top four ranking was maize, beans, cotton, and wheat (Secretaria de Econamia, Direccion General de Estadistica, Citation1954). From 1980 to 2015, Chihuahua increased the area planted in annual crops from 722,532 ha, of which 29.1% was irrigated, to 916,316 ha, of which 40.0% was irrigated (https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/[SIAP]).

Janos County includes sections of the Sierra Madre Occidental but the northern and eastern sections are dominated by basin-and-range topography and mixed desert rangeland. Basin rangelands have an average elevation of about 1,400 m (Davidson et al., Citation2010). Annual rainfall is highly variable but averages 306 mm, bimodally concentrated in a late summer monsoon and scattered winter rains (Davidson et al., Citation2010). Winters are cold with lows frequently below freezing, and summers are hot with highs above 45 C. Crops are planted in the spring with the exception of wheat and oats, which are often planted in the fall for harvest the following spring.

In 2010, the county had 10,953 residents; the largest town was Janos with 2,738 people (Secretaria de Desarrollo Rural, Citation2013). Janos town was originally established as a Catholic mission in 1580, but the area remained sparsely settled for centuries due to the region’s aridity and long-running conflict with the Apache (Griffen, Citation1988). By 1900, three giant ranches owned by US citizens occupied most of Janos County (Hart, Citation2002; Wasserman, Citation2015). Under the land reform, all three were forcibly subdivided and redistributed. Fourteen ejidos were established within the county by 1992, accounting for 33% of the county’s total 742,046 ha (INEGI, Citation1999). By 2015, 97% of the county had electricity and 94% had piped domestic water (INEGI, Citation2016).

Of the 14 ejidos, only six have a significant area of farmland. Each of those six is composed of parcels (parcelas) allocated to individual ejidatarios for farming, and common grazing areas (uso común) that are typically divided and fenced by groups or families working together. The other eight ejidos are devoted either to cattle or to cattle and timber. Beside the ejidos, the dominant landowners in the county are ranchers and Mennonites. Mennonite landownership is concentrated in five colonies (colonias), each of which includes at least one 2,000–6,000 ha block purchased as a single property and internally subdivided among individual households. Nearly all land not controlled by the ejidos or Mennonites is in privately owned cattle ranches, typically 5,000–13,000 ha in size.

‘Mennonite’ refers to people of a Christian faith originating in Flanders in the early sixteenth century with the teachings of Menno Simons. Mennonite communities historically sought to establish farming communities in underdeveloped areas in exchange for exemptions from state requirements like military service and educational standards. This led them eastward to Russia in the late eighteenth century, to central Canada in the 1870s, and Mexico in the 1920s. President Obregón granted several thousand conservative Mennonites state exemptions (from military service, education standards, and others) to settle in northern Mexico in the hope they would facilitate a post-Revolution economic recovery. The largest concentration of Mennonites started farming and dairying communities in the Sierra Madre foothills of central Chihuahua, near what became the city of Cuauhtémoc (Bridgemon, Citation2012; Dormady, Citation2014; Sawatzky, Citation1971). Mennonites from Mexico, Canada, and Russia subsequently immigrated to numerous other countries in Latin America (see also Caldas, Goodin, Sherwood, Campos Krauer, & Wisely, Citation2015; Ellis et al., Citation2017; Sawatzky, Citation1971, Appendix).

In Chihuahua (at least), Mennonites have assimilated very little. Among all communities in Janos, the noun ‘Mexicano/a’ (Mexican) always refers to a non-Mennonite, though Mennonites are also Mexican citizens. Rarely intermarrying or proselytizing, they remain ethnically distinct, continue to use Plautdietsch (a unique dialect of low German/Prussian) as their first language, typically dress distinctly, and many colonies maintain varying technology prohibitions (e.g. television, domestic electricity, cars); farming technology is much less restricted, and not at all in Janos since the early 1990s. Most Mennonites also retain dual Mexican and Canadian citizenship, as Canadian law prior to a 2009 amendment permitted Canadian citizens to apply for citizenship for children born outside Canada (Government of Canada, Citationn.d.).

Research approach and methods

The focus on land in LULCC research often overlooks the complex constellations of actors and their motivations involved in changing the land, a core topic of this Special Issue. This study sought to understand how the process of agricultural frontier expansion evolves over time through an examination of the people who conducted that expansion. By studying agricultural frontier expansion as a historic social process, the connections between changes in the land and changes in political economic or other social conditions are brought to the fore. To that end, this study follows a political ecology approach. Political ecology is a bottom-up tradition of research and analysis related to human geography that ‘seeks to unravel the political forces at work in environmental access, management, and transformation’ (Robbins, Citation2012, p. 3). Political ecology and land-change science share an interest in historical processes of social and environmental change and included social-ecological feedbacks, although political ecology tends to focus more on social drivers of change (Turner & Robbins, Citation2008). To understand who conducts LULCC and why this research was based on asking the people who own and manage land about who they are and how and why they managed their land as they do.

Field research took place from March to October of 2017, during which time I lived on one of the ejidos. Research relied primarily on two types of interviews: 114 semi-structured interviews with landowners or ex-landowners (49 ejidatarios, 40 Mennonites, and 25 ranchers), and 53 open-ended interviews with key informants, local experts, government officials, and at least one member of every ejido and Mennonite colony in Janos County. Rancher interviews were used primarily for historical background and to explain specific large land transactions. Landowner interviews focused on the personal history of land ownership and use, reasons why land use/cover changes were made, available resources, and livelihoods (questionnaires are included as supplemental material). Open-ended interviews were used to fill in specific knowledge gaps about historical details, specific communities, farming and ranching practices, and government policies/programs. All interviews were conducted in Spanish except two in English.

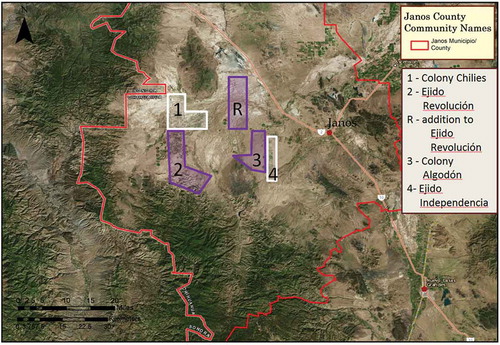

The 49 ejidatario landowner interviewees were selected from Ejido Independencia and Ejido Revolución, while the 40 Mennonite landowners were selected from Colonia Algodón and Colonia Chiles (ejido and colonia names have been changed). Ejido Independencia is almost entirely arable, while approximately one-third of Ejido Revolución’s designated grazing land is too hilly for farming (). Ejido Independencia and Colonia Algodón are adjacent, and Ejido Revolución and Colonia Chiles are adjacent (). Adjacent communities were selected to capture intergroup dynamics, and these specific combinations were selected to include differences in Mennonite colony size and age and differences in ejidatario livelihoods and outmigration. Interviewees were selected via a snowball sampling approach stratified by age, primary livelihood, and amount of land owned. This common qualitative approach garnered interviews with all socioeconomic segments of each focal community but does not generate a statistically representative sample. Where possible, data gained from interviews (e.g. important land transactions, BANRURAL functioning) were verified in subsequent interviews and with key informants to ensure an accurate accounting of historical change and the functioning of important drivers. Some details, such as the mechanics of certain large land sales or the use of particular credit sources, took months and many interviews to triangulate.

Table 1. Specific details about the four focal communities of this study. Note that Mennonites have recently acquired additional land for farming adjacent to the original two Mennonite colonies, but these lands are not managed by colony institutions. Data on Mennonite colonies come from interviews; data on ejidos come from the Registro Agrario Nacional.

Figure 2. Map of Janos county showing the location of the four focal communities. Ejidos are outlined in purple, Mennonite colonies are outlined in white.

Interview notes were topically coded using MaxQDA v.11 software (produced by VERBI GmbH) to facilitate qualitative analysis. I created 46 in-vivo (terms taken directly from the notes) and constructed codes (terms/ideas I developed during analysis) using line-by-line open coding, focusing on land use (e.g. ‘crops grown’), land ownership (e.g. ‘land sales’, ‘land purchases’), household economics (e.g. ‘economic diversification’, ‘credit use’), farming technology (e.g. ‘irrigation’, ‘farm machinery’), the environment (e.g. ‘drought’, ‘groundwater’), social dynamics (e.g. ‘cooperation’), and policy impacts (e.g. ‘land reform’, ‘BANRURAL’). Most important for this study, personal land-use histories and mechanics of individual land transactions detailed in interviews were scrutinized to determine drivers and establish patterns in the process of agricultural expansion. Analysis sought to identify patterns of transitions in land use and ownership (such as when a parcel is converted from rangeland to crops or sold to a neighbor) at the level of the individual and at the level of the community.

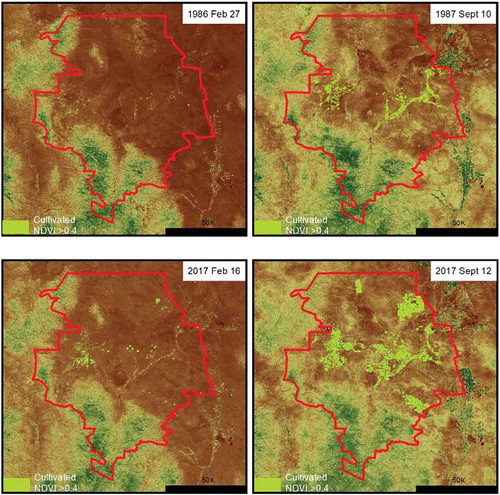

Government statistics report that Janos County had 10,698 ha of crops in 1970 (of which 4,067 ha were irrigated) (Dirección General de Estadística, Citation1975), 11,286 ha in 1981 (9,416 ha irrigated) (INEGI, Citation1986), and 35,377 ha in 2017 (34,639 ha irrigated) (https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/). Doolittle (Citation1988) commented on the inaccuracy of county-level (municipio) agricultural statistics. Based on my experience in the field and approximations from Google Earth Pro imagery, the most recent figure appeared to underestimate the area of crops. To test that hypothesis, remote sensing of Landsat imagery was used to provide a potentially more accurate – though still rough – estimate of agricultural expansion from 1987 to 2017 (years when good imagery was available at the right time of year). Using ArcGIS, Landsat 5 (Feb. 1986, Sept. 1987) and Landsat 8 (Feb. and Sept. 2017) 30m-resolution images of Janos County were preprocessed for radiometric calibration and processed to calculate normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI). February images were included to capture crops that over-winter, mainly wheat, oats, and alfalfa. To reduce the risk of misclassifying other cover types as crops, NDVI was only calculated within regions known to have crop agriculture, based on topography, my knowledge of the site, and imagery from Google Earth Pro. Agriculture was indicated by NDVI values greater than 0.4; background NDVI values are quite low due to the site’s aridity. Validation was performed solely based on knowledge of the site and by visual comparison with higher resolution imagery available through Google Earth Pro.

Results

Remote sensing

Between September 1987 and September 2017, land area under crop production increased by 37,916 ha, or 245% (). Crop area in September 1987 was calculated to be 15,436 ha, which includes 269 ha of land in crops in February 1986 but fallow in September 1987. In 2017, the crop area was 53,352 ha, which includes 928 ha only cropped in February. Each date includes some non-cultivated riparian vegetation and excludes some crop fields temporarily fallow when the images were taken.

Three phases of agricultural development

Expansion of the agricultural frontier in Janos occurred continuously, but interviews revealed that the process of expansion occurred in three successive phases, each with different drivers (). Each phase is typified by a different pattern of land ownership and technological and capital intensity of agricultural production.

Table 2. The three phases of agricultural development in Janos county, Chihuahua. Transition from one phase to another was gradual and varied by exact location, so dates are approximate.

Phase one – land reform and migration, ~1955–1990

Agricultural expansion during this period was driven primarily by in-migration to newly established ejidos and Mennonite colonies. Land reform created four ejidos with areas designated for farming (and three more just for grazing) on rangeland expropriated from private ranches. Most of the new ejidatarios had petitioned the government for land while working as wage laborers elsewhere in Chihuahua and arrived at Janos County with no farm equipment and little money. Threat of government land expropriation also motivated private ranchers to sell four separate parcels of land to groups of Mennonites from the Cuauhtémoc area for the purpose of establishing agricultural colonies. Except for 743 ha of farmland on the parcel purchased as Colonia Algodón (Sawatzky, Citation1971, p. 174), the four colonies and four farming ejidos established during this period were initially composed of native rangeland that had to be converted to farming.

With the exception of Ejido Libertad, which benefited from the town of Janos within its periphery, ejidos in Janos County have rarely been fully occupied by their members. Many ejidatarios lived elsewhere, abandoned their land rights (derechos), or sold them (which was illegal but generally accepted). Independencia is exemplary: of the 103 initial land recipients, no more than 50 ever lived in the area for more than a few years. For those ejidatarios that did establish residence, many raised cattle but could not start farms. Communal grazing land was fenced with government support, and cattle could be accepted as grazing fees for renting land to neighboring ranches. The government established a maximum ‘sustainable’ number of livestock allowed per land right (e.g. 7 on Independencia, 12 on Revolución). Cattle sales from just one land right could not support an ejidatario household, requiring additional income sources or the purchase of additional grazing land rights to make ends meet.

Farming on the ejidos has been limited by climate and lack of resources. Although farming parcels are large by ejido standards – 10–20 ha – investment costs for commercial farming are high. Crop agriculture was unreliable without irrigation, but the cost of drilling wells – currently $30,000–50,000 US dollars (USD) – has been prohibitive for the vast majority of ejidatarios. Various government programs paid to install a small number of wells on Independencia, Revolución, and four other ejidos, mostly in the 1970s, but only a minority of each ejido had good access. Those that did have irrigation were eligible for loans from BANRURAL for farm machinery and farm inputs. While many ejidatarios I interviewed on Ejido Revolución had tried farming without irrigation or credit from BANRURAL in the 1970s or 1980s, all but one gave up after a few years due to bad harvests. One man continued dry farming until 2012 despite declining harvests after 1992, growing maize to feed pigs to sell for meat. Crop production was generally for market and the most common crops – maize, beans, and sorghum – could be sold to CONASUPO at above-market prices. Many ejidatarios used animal-drawn plows in the early years but those were quickly replaced with tractors purchased through BANRURAL. Ejidatarios who did not have access to an irrigation well earned cash through wage labor or sometimes by buying/renting additional ejido grazing land to raise cattle, which was far cheaper than installing irrigation. Others simply gave up and sold out to other ejidatarios or non-rights-holding ejido residents – such as the sons of ejidatarios – before emigrating to the US or cities in Chihuahua. Formal recognition of these sales by ejido assemblies varied widely, one reason official records rarely reflect real ejido membership.

The first Mennonite colony in Janos was Algodón, formed in 1958 when a group of Mennonites from Cuauhtémoc bought the ~2,700 ha farm and ranch property from a US citizen faced with possible occupation and expropriation. As is common for Mennonite colonies, a single church order in Cuauhtémoc organized interested households and collected down payments for small parcels, with the remainder of the purchase price secured with a bank loan. Initial purchasers/settlers only occupied a portion of the land, and the remaining parcels were sold to subsequent settlers. The colony held the property deed, with internal documentation of who owned what land. This same process was repeated with Colonia Chiles (1981) and two other colonies (1979 and 1985). A smaller colony formed in 2005 was different, in that the sale was purchased after being converted to farming, allegedly by a drug cartel.

Initially, Mennonite farm parcels ranged from 15 to 50 ha, depending on the wealth of the purchaser. Many settlers sold farmland in Cuauhtémoc at operational farmland prices and bought larger parcels in Janos at (lower) rangeland prices, bringing farm equipment with them. Settlers bought, rented, or hired bulldozers to clear and level land for flood irrigation. To install wells, many neighbors pooled finances to hire another Mennonite to drill a well at the juncture of their parcels and share the water; payments were often delayed to allow payment with subsequent farming profits. During this period, the most common crops were cotton, maize, beans, sorghum, and oats. Colonies collected taxes that were used to build/maintain roads and, in the 1990s, to pay the requisite portion of installing electricity poles/lines.

Before the 1990s, the use of operating credit for farming was uncommon, and only a few Mennonites used BANRURAL loans to start farming. Instead, farmers saved profits from each year’s harvest to buy farm inputs the following year, often saving their own seed to reduce costs. Maize, beans, wheat, and sorghum were sold to CONASUPO, cotton to gins in Nuevo Casas Grandes (the much bigger town south of Janos), and milk and cheese through mostly local markets. Farm machinery was then, as now, usually purchased secondhand in the US, though young men usually start farming by borrowing machinery from family members until they can buy their own with farm profits.

Phase 2: economic differentiation and the neoliberal turn, ~1990–2010

Four important changes in the 1990s spurred changes in landownership and agricultural production, leading to new forms of agricultural expansion. The first was the ending of BANRURAL, which largely eliminated credit access for ejidatarios. As a result, many ejidatarios were no longer able to afford the necessary inputs for farming, and some returned farm equipment purchased on BANRURAL credit. Partly in response, a Mennonite credit union, UCACSA, opened in Cuauhtémoc in 1994, offering operating and equipment credit to Mennonites with solid references all over Chihuahua.

Second, NAFTA was ratified in 1994, which, combined with the termination of CONASUPO and related domestic price supports, caused a decline in farmgate prices of staple crops across Mexico (Cornelius & Myhre, Citation1998b). NAFTA also allowed the ready sale of some high-value crops, especially chilies and onions, to the US, making these crops lucrative, though volatile, for those farmers able to invest in the expensive plantings and manual labor (generally by migrant workers from southern and central Mexico). A significant share of chili production shifted from the border region in the US to northern Mexico during this period as more Mennonite farmers adopted the crop (see also Meyers, Citation2017).

Third, a decade-long drought started in 1992 (see also Ortega-Ochoa, Villalobos, Martínez-Nevárez, Britton, & Sosebee, Citation2008). The drought essentially ended the little remaining rainfed agriculture on the ejidos and severely reduced forage production for livestock, forcing ejidatarios and ranchers alike to sell off cows at low prices.

Lastly, electricity came to Janos County in the early 1990s. For ejidos, this was financed almost entirely by the government, while Mennonite colonies had to pay a much higher percentage of the cost. The real boon of electricity was for running water pumps and the newly arrived center pivot irrigation systems (which are far more water efficient, requiring less water to be pumped); by this time, rising diesel prices caused by declining diesel subsidies were making diesel pumps and flood irrigation unprofitable. Center pivots were common in Janos County by 2010.

Numerous interviews confirmed that, during the 1990s, many ejidatarios could no longer afford to continue farming due to lack of credit, rising operating costs, and declining crop prices. Those who could not farm frequently sold their land and emigrated, usually to the US. I interviewed many ejidatarios and Mennonites who had bought land from emigrating ejidatarios during the 1990s. Sales were facilitated by policy changes enacted since the formal end of the land reform in 1992, namely amendments to Article 27 of the constitution and establishment of the PROCEDE program.

Mennonites from Algodón also started buying farmland and rangeland on neighboring ejidos, which was considerably cheaper than land within the colony, usually installing new irrigation wells with each purchase. Algodón farmers bought land, and technically became ejidatarios, on four different ejidos, while Mennonites from Chiles own limited parcels on two more. Buyers are usually established farmers with significant annual profits and savings, though some young men start their farms by buying ejido land, often with family financial support. Loans are almost never used to buy land. Instead, Mennonites often pay the seller in multiple annual installments after taking control of the land, allowing them to pay for land with profits earned from farming that land. For example, one interviewee on Algodón bought his first 20 ha of farmland on Algodón with earnings from working (legally) in the US for 4 years. With farm profits, he went on to rent and then buy 110 ha in Algodón, 100 ha in Ejido Libertad, and then 50 ha in Ejido Independencia, having to either extend or drill a new well on each new property. When asked why the ejidatarios had first rented and then sold land to him, he shrugged and replied ‘Well, they do not know how to farm’ (my translation). Other Mennonites described buying land from ejidatarios who had family emergencies and no way to raise cash quickly except to sell land rights.

For decades each of the first four Mennonite colonies had land reserves available for purchase and conversion by younger generations or farmers looking to expand. Rather than buying virgin rangeland, however, many successful farmers bought out their neighbors’ farms instead; similar to the ejidatarios, many small farmers were forced to sell out as declining state agricultural supports made their farms insolvent, and many subsequently sought wage work in Mennonite-dominated towns in Canada. The average farm size grew during this period as the smallest farms were absorbed into larger operations.

Phase 3 – agricultural investment and von Thünian land rents, ~2010-present

By now, crop agriculture on the ejidos has been largely reduced to low-investment, low-return crops (e.g. alfalfa), farming by Mennonite renters or owners, and large-scale farming by a few ejidatario families who have bought up multiple farming parcels. Much designated farmland is still fallow. All crop farming at Ejido Independencia, for example, is now conducted by Mennonite owners or renters. At Ejido Revolución, I interviewed three ejidatario families who each farmed at least 100 ha, having purchased numerous parcels from other ejidatarios. In all three cases, multiple family members (brothers or fathers and sons) had cooperated to acquire land and machinery, farm the land, and engage outside wage labor as needed to bring in extra income. Few other ejidatario farmers on Revolución owned more than two parcels, with alfalfa as the most common crop. One older interviewee on Ejido Revolución lives off the income from his 12 cows and 30 ha of alfalfa, which he – like many others – pays a Mennonite to cut and bale for him. He called alfalfa ‘a crop for lazy people,’ but it provided a modest living with little investment.

Since 2010, the Mennonite colonies have continued to purchase more ejido land and have also expanded into private ranches. Land sales are stimulated in part by von Thünian land rents; Mennonites pay significant price premiums for rangeland bordering existing Mennonite farms (and therefore roads and powerlines). Rangeland bought for grazing cattle might go for $200–350 USD per ha, while rangeland bought by Mennonites for farming goes for $2,000–10,000 USD per ha, depending on the existence of wells, roads, and electricity lines. Ranchers and ejidatarios are motivated to sell land to Mennonites to capture what seem like windfall prices. Two brothers I interviewed used the earnings from selling one ranch to an adjacent Mennonite colony to buy two other ranches that did not border colonies, indicating how land prices vary with distance to a colony.

Small groups of members from Chiles and two other colonies have used farm profits to cooperatively purchase rangeland from neighboring ranchers and convert it to irrigated crops. In some cases, the buyers are resident Mennonites looking to expand their operations or buy land for their sons. In at least one case, investment-motivated buyers installed wells on a > 5,000 ha parcel, subdivided it, and sold off lots to other Mennonites at a profit. Other large parcels (e.g. 3,200 ha bordering Colonia Chilies) were bought by groups of investors from Cuauhtémoc and/or Canada who hire local young Mennonites to convert and farm the land. I observed this same pattern at another Mennonite colony in eastern Chihuahua where I also did interviews (October 2017). That colony was established by a handful of Mennonite families mostly from Cuauhtémoc in 1996. By purchasing additional ranches, including one ~4,000 ha ranch purchased by a single family from Cuauhtémoc, Mennonites now own approximately 100,000 ha of contiguous land, of which about half was cropped in 2017.

The innovations in Mennonite farming during this phase were the increasing adoption of drip irrigation and the planting of pecan orchards, both of which require high up-front investment costs. Drip irrigation is the most water-efficient irrigation method available, and its adoption is motivated by aquifer decline and superior performance in growing onions and chilies. Mennonite farmers have increased chili production so much that they flooded the New Mexico-dominated market in 2015, causing some buyers to halt purchases halfway through the harvest. According to my estimates from field observations, there are still less than 500 ha of pecans in Janos County but that number is increasing. Pecan trees are more profitable, have higher start-up costs, and require more water per hectare than any other crop grown in the area.

Discussion

Calculating the expansion of area under crops

The 1987 figure for crop area produced by remote sensing exceeds the 1981 INEGI figure by 4,150 ha, at least some of which is likely due to land converted in the intervening years. The 2017 remote sensing figure for crop area exceeds the 2017 SIAP figure by 17,975 ha. Given the rudimentary calculation method and lack of model validation, some misclassification in the remote sensing analysis is expected. Even if the 1987–1981 discrepancy is attributed only to misclassification of non-cropland as crops, however, that erroneous 4,150 ha accounts for less than one quarter of the discrepancy between the 2017 figures. It is reasonable to assume, then, that the 2017 SIAP figures are low and that the current true area of crops is at least 49,202 ha (53,352 minus 4,150), or nearly five times what INEGI reported in 1981.

The evolution of agricultural frontier expansion

Much of the literature on agricultural frontiers in Latin America highlights the role of the state in initiating waves of expansion, and the case of Janos County fits this narrative. The Mexican state directly redistributed land from ranchers to ejidatarios and indirectly (unintentionally) precipitated the sale of ranch land to Mennonites through national land reform. Put simply, the land reform stimulated in-migration of would-be farmers to Janos County. Following the settlement, the state also operated many agricultural support programs, especially for ejidatarios, that helped establish small-scale commercial agriculture on former ranches.

As in other research in Latin America (Gould et al., Citation2006; Hecht, Citation2005; Humphries, Citation1998; Jepson et al., Citation2010; Pacheco, Citation2006; Southgate, Citation1990), expansion of the agricultural frontier in Janos County began with in-migration of settlers but continued due to internal economic factors. The case of Janos suggests that this pattern of agricultural expansion is due partly to the dynamics of agrarian change typical of capitalist agriculture anywhere, especially economic differentiation and expansion of the most profitable farms.

Each ejido and Mennonite colony in Janos County started out being relatively homogenous economically, though Mennonites were generally wealthier than ejidatarios. As farming costs rose and crop prices declined, economic differentiation within and between communities was characterized by profitable farmers intensifying production and buying more land while less profitable farmers sold land, sought wage labor, and migrated out. Colonia Algodón exemplifies this process; in 1985, a stereotypical successful Mennonite farmer had 50 ha of cotton and maize on flood irrigation and saved their own seeds. Now the same farmer might have 300 ha of chilies, onions, genetically modified cotton, and hybrid maize watered with center pivots and drip irrigation, and hires 1–3 full-time employees plus seasonal migrant laborers. Similar, if less dramatic, changes have occurred in some ejidos.

The acceleration of differentiation after Mexico’s neoliberal policy reforms of the 1990s fits the global narrative of ‘dispossession by differentiation’ described by Araghi (Citation2009). According to Araghi, neoliberal trade and austerity policies initiated since 1973 limited state protections for small-scale farmers and reduced real crop prices, leading to ‘depeasantization’ and rural-to-urban migration throughout much of the world (see also Araghi, Citation2000; Akram-Lodhi & Kay, Citation2010b). The case of Janos County clearly demonstrates how access, in the sense of Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003), varies between social groups, divided in this case by land tenure and ethnicity (see also Ellis et al., Citation2017; Fan, Li, Zhang, & Li, Citation2014).

The vast majority of ejidatarios who received land in Janos after 1950 had no familial history there, had not previously been farmers, did not know one another prior to arrival, and arrived with few material or economic resources. Ejidatarios were largely dependent on state support to establish and continue intensive-irrigated agriculture, and many had to abandon or reduce the intensity of agriculture (i.e. switch to alfalfa) after government support programs ended in the 1990s, as occurred in other areas of irrigated agriculture in northern Mexico (Lewis, Citation2002; Whiteford et al., Citation1998). Mennonites, in contrast, arrived in Janos County with resources to drill their own wells and establish irrigated farms. The Mennonite access regime was improved by social institutions – both within and off colonies – that facilitated access to credit, farm machinery, and agricultural services such as cotton gins and chili contracts. Mennonite farmers were also motivated to acquire large farms (sometimes >300 ha) so that they could pass on farmland to each son. In contrast, ejidatario farmers typically encouraged their children to pursue education and non-agricultural livelihoods, limiting motivation to acquire land. Recently, Mennonite social institutions motivated Mennonites from outside Janos – such as Cuauhtémoc – to buy and convert ranchland to farms adjacent to existing colonies once local infrastructure was established and a skilled Mennonite labor supply (young men) was available.

Conclusions

Expansion of crop agriculture into Janos County was initially promoted by state programs supporting migration and agricultural development, especially the land reform. But expansion continues decades after those programs were terminated even in the face of conservation policies designed to halt it (Hruska, Toledo, Sierra-Corona, & Solis-Gracia, Citation2017). The case of Janos County demonstrates that state action is important – though not necessarily required – for initiating expansion at an agricultural frontier. Once the expansion is underway, however, it can continue under its own economic momentum given suitable conditions. In Janos, agriculture now appears likely to continue expanding until groundwater becomes either too costly or too scarce, which nearly all interviewees agreed will happen eventually.

This study stresses the importance of taking into consideration how the dynamics of agricultural expansion change over time. State programs that support land transfer, migration, and the establishment of agriculture were important drivers only in the first stage of expansion in Janos. Subsequently, economic differentiation of farmers and von Thünian land-rent factors drove further land sales and LULCC. Differentiation created an investor class of farmers who could afford to buy rangeland for conversion to irrigated farming, furthering agricultural expansion. These findings demonstrate the role that agrarian change can play in expanding agricultural frontiers, where agriculture is market-oriented. Where agricultural colonists do not sell harvests or generate profits, as has often happened after land reforms (e.g. Chimhowu & Hulme, Citation2006; McCusker, Citation2004), agriculture may be abandoned rather than expanded. To understand the process of agricultural expansion, it is important to examine local microeconomics and to differentiate between LULCC driven by in-migrants from that driven by existing residents.

Economic differentiation of farmers and the associated intensification/expansion of successful farms may have divergent results for different social groups, exacerbating economic inequalities. The land reform gave ejidatarios land rights but not the resources necessary to establish self-sustaining intensive farms. Mennonites in Janos County benefited from better economic starting conditions than ejidatarios but also a unique access regime based on Mennonite institutions and social networks. While Mennonites continue to expand the agricultural frontier, consolidation of landownership is beginning to inspire claims of injustice even among many Mennonites.

As this paper demonstrates, empirical, qualitative research methods are needed to capture detailed information on the actors performing LULCC, their experiences, and specific contexts. Combining multi-scalar data from land-use science and agrarian studies research methods offers opportunities to better understand how agricultural frontiers evolve.

Interview_Questions_Supplement.docx

Download MS Word (24.7 KB)Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my project funders and the Instituto de Ecología at UNAM for making this research possible. Thanks to Carl Reeder for making the maps and running the remote sensing analysis with my uncertain direction; to Gabriela Duran-Irigoyen for tireless research assistance; and to Rodrigo Sierra Corona for endless tips, insights, and use of the bus. Lynn Huntsinger, Lauren Withey, Laura Dev, Juliet Lu, Cristina de la Vega-Leinert, and two anonymous reviewers all provided valuable suggestions for improving the manuscript. Many thanks to the communities who hosted me and treated me with kindness and humor despite their skepticism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Mennonites are members of a Christian Anabaptist sect that continue to speak a version of low German as their primary language, and who are ethnically distinct from the general Mexican population. A more complete description is provided in the Site Description section.

References

- Aboites Aguilar, L. (2012). The transnational dimensions of Mexican irrigation, 1900–1950. Journal of Political Ecology, 19(1), 70–80.

- Akram-Lodhi, A.H., & Kay, C. (2010a). Surveying the agrarian question (part 1): Unearthing foundations, exploring diversity. Journal of Peasant Studies, 37(1), 177–202.

- Akram-Lodhi, A.H., & Kay, C. (2010b). Surveying the agrarian question (part 2): Current debates and beyond. Journal of Peasant Studies, 37(2), 255–284.

- Alston, L.J., Libecap, G.D., & Schneider, R. (1996). The determinants and impact of property rights: Land titles on the Brazilian frontier. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 12(1), 25–61.

- Angelsen, A. (1999). Agricultural expansion and deforestation: Modelling the impact of population, market forces and property rights. Journal of Development Economics, 58(1), 185–218.

- Araghi, F. (2000). The great global enclosure of our times: Peasants and the agrarian question at the end of the twentieth century. In F. Magdoff, F.H. Buttel, & J. Bellamy Foster (Eds.), Hungry for profit: The agribusiness threat to farmers, food, and the environment (pp. 145-160). New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

- Araghi, F. (2009). The invisible hand and the visible foot: Peasants, dispossession and globalization. In A.H. Akram-Lodhi & C. Kay (Eds.), Peasants and globalization (pp. 111–147). New York: Routledge.

- Assies, W. (2008). Land tenure and tenure regimes in Mexico: An overview. Journal of Agrarian Change, 8(1), 33–63.

- Baldi, G., Guerschman, J.P., & Paruelo, J.M. (2006). Characterizing fragmentation in temperate south America grasslands. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 116(3–4), 197–208.

- Barona, E., Ramankutty, N., Hyman, G., & Coomes, O.T. (2010). The role of pasture and soybean in deforestation of the Brazilian amazon. Environmental Research Letters, 5(2), 024002.

- Bernstein, H. (2010). Class dynamics of agrarian change. Agrarian change and peasant studies series. Black Point, Novia Scotia: Fernwood; and Sterling, VA: Kumerian.

- Bockstael, N.E. (1996). Modeling economics and ecology: The importance of a spatial perspective. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 78(5), 1168–1180.

- Bonilla-Moheno, M., Aide, T.M., & Clark, M.L. (2012). The influence of socioeconomic, environmental, and demographic factors on municipality-scale land-cover change in Mexico. Regional Environmental Change, 12(3), 543–557.

- Borras, J.S., Kay, M., Gómez, C., & Wilkinson, J. (2012). Land grabbing and global capitalist accumulation: Key features in Latin America. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études Du Développement, 33(4), 402–416.

- Brannstrom, C. (2009). South america’s neoliberal agricultural frontiers: Places of environmental sacrifice or conservation opportunity. Ambio, 38(3), 141–149.

- Bray, D.B., & Klepeis, P. (2005). Deforestation, forest transitions, and institutions for sustainability in southeastern Mexico, 1900–2000. Environment and History, 11(2), 195–223.

- Bridgemon, R.R. (2012). Mennonites and Mormons in northern Chihuahua, Mexico. Journal of the Southwest, 54(1), 71–77.

- Burke, I.C., Yonker, C.M., Parton, W.J., Cole, C.V., Schimel, D.S., & Flach, K. (1989). Texture, climate, and cultivation effects on soil organic matter content in US grassland soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 53(3), 800–805.

- Caldas, M.M., Goodin, D., Sherwood, S., Campos Krauer, J.M., & Wisely, S.M. (2015). Land-cover change in the Paraguayan Chaco: 2000–2011. Journal of Land Use Science, 10(1), 1–18.

- Ceballos, G., Davidson, A., List, R., Pacheco, J., Manzano-Fischer, P., Santos-Barrera, G., & Cruzado, J. (2010). Rapid decline of a grassland system and its ecological and conservation implications. PloS One, 5(1), e8562.

- Chimhowu, A., & Hulme, D. (2006). Livelihood dynamics in planned and spontaneous resettlement in Zimbabwe: Converging and vulnerable. World Development, 34(4), 728–750.

- Cornelius, W.A., & Myhre, D. (1998a). Introduction. In W.A. Cornelius & D. Myhre (Eds.), The transformation of rural Mexico: Reforming the ejido sector (pp. 1–24). La Jolla: Center for US-Mexico Studies, University of California, San Diego.

- Cornelius, W.A., & Myhre, D. (Eds.). (1998b). The transformation of rural Mexico: Reforming the ejido sector. La Jolla, CA: Center for US-Mexico Studies, University of California, San Diego.

- Davidson, A.D., Ponce, E., Lightfoot, D.C., Fredrickson, E.L., Brown, J.H., Cruzado, J., … Toledo, D. (2010). Rapid response of a grassland ecosystem to an experimental manipulation of a keystone rodent and domestic livestock. Ecology, 91(11), 3189–3200.

- De Janvry, A., Emerick, K., Gonzalez-Navarro, M., & Sadoulet, E. (2015). Delinking land rights from land use: Certification and migration in Mexico. American Economic Review, 105(10), 3125–3149.

- De Janvry, A., Gordillo, G., & Sadoulet, E. (1997). Mexico’s second agrarian reform: Household and community responses, 1990–1994. La Jolla, CA: Center for US-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA.

- De Janvry, A., & Sadoulet, E. (2001). Income strategies among rural households in Mexico: The role of off-farm activities. World Development, 29(3), 467–480.

- Deere, C.D., & Leon, M. (2001). Empowering women: Land and property rights in Latin America. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Deng, L., Zhu, G., Tang, Z., & Shangguan, Z. (2016). Global patterns of the effects of land-use changes on soil carbon stocks. Global Ecology and Conservation, 5(11), 127–138.

- DeWalt, B.R., & Rees, M.W. (1994). The end of agrarian reform in Mexico: Past lessons, future prospects. San Diego, CA: Ejido Reform Research Project, Center for US-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego.

- Dirección General de Estadística. (1975). V censos agricola-ganadero y ejidal – 1970. Mexico: Talleres Gráficos de la Nación.

- Doolittle, W.E. (1988). Intermittent use and agricultural change on marginal lands: The case of smallholders in eastern Sonora, Mexico. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 70(2), 255–266.

- Dormady, J. (2014). Mennonite colonization in Mexico and the pendulum of modernization, 1920–2013. Mennonite Quarterly Review, 88(2), 167–195.

- Eilenberg, M. (2014). Frontier constellations: Agrarian expansion and sovereignty on the Indonesian-Malaysian border. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(2), 157–182.

- Ellis, E.A., Montero, J.A.R., Gómez, I.U.H., Porter-Bolland, L., & Ellis, P.W. (2017). Private property and Mennonites are major drivers of forest cover loss in central Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Land Use Policy, 69, 474–484.

- Fan, M., Li, W., Zhang, C., & Li, L. (2014). Impacts of nomad sedentarization on social and ecological systems at multiple scales in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region, China. Ambio, 43(5), 1–14. doi:10.1007/s13280-013-0445-z

- Farley, K.A., Ojeda-Revah, L., Atkinson, E.E., & Eaton-González, B.R. (2012). Changes in land use, land tenure, and landscape fragmentation in the Tijuana river watershed following reform of the ejido sector. Land Use Policy, 29(1), 187–197.

- Finan, F., Sadoulet, E., & De Janvry, A. (2005). Measuring the poverty reduction potential of land in rural Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 77(1), 27–51.

- Geist, H.J., & Lambin, E.F. (2002). Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical DeforestationTropical forests are disappearing as the result of many pressures, both local and regional, acting in various combinations in different geographical locations. Bioscience, 52(2), 143–150. Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art1/

- Gibbs, H.K., Ruesch, A.S., Achard, F., Clayton, M.K., Holmgren, P., Ramankutty, N., & Foley, J.A. (2010). Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16732–16737.

- Gordon, L.J., Peterson, G.D., & Bennett, E.M. (2008). Agricultural modifications of hydrological flows create ecological surprises. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23(4), 211–219.

- Gould, K.A., Carter, D.R., & Shrestha, R.K. (2006). Extra-legal land market dynamics on a Guatemalan agricultural frontier: Implications for neoliberal land policies. Land Use Policy, 23(4), 408–420.

- Government of Canada. (n.d.). Changes to citizenship rules 2009 to 2015. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/canadian-citizenship/act-changes/rules-2009-2015.html

- Griffen, W.B. (1988). Apaches at war and peace: The Janos Presidio, 1750–1858. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Guo, L.B., & Gifford, R.M. (2002). Soil carbon stocks and land use change: A meta analysis. Global Change Biology, 8(4), 345–360.

- Hall, A.L. (1989). Developing Amazonia: Deforestation and social conflict in Brazil’s Carajás programme. New York: Manchester University Press.

- Hall, D. (2013). Primitive accumulation, accumulation by dispossession and the global land grab. Third World Quarterly, 34(9), 1582–1604.

- Hall, S.C., & Caviglia-Harris, J. (2013). Agricultural development and the industry life cycle on the Brazilian frontier. Environment and Development Economics, 18(3), 326–353.

- Hannah, L., Carr, J.L., & Lankerani, A. (1995). Human disturbance and natural habitat: A biome level analysis of a global data set. Biodiversity & Conservation, 4(2), 128–155.

- Hanson, G.H., & McIntosh, C. (2010). The great Mexican emigration. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 798–810.

- Hart, J.M. (2002). Empire and revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the civil war. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hecht, S.B. (1985). Environment, development and politics: Capital accumulation and the livestock sector in eastern Amazonia. World Development, 13(6), 663–684.

- Hecht, S.B. (1993). The logic of livestock and deforestation in Amazonia. Bioscience, 43(10), 687–695.

- Hecht, S.B. (2005). Soybeans, development and conservation on the Amazon frontier. Development and Change, 36(2), 375–404.

- Heimlich, R.E. (1986). Agricultural programs and cropland conversion, 1975–1981. Land Economics, 62(2), 174–181.

- Hersperger, A.M., Gennaio, M., Verburg, P.H., & Bürgi, M. (2010). Linking land change with driving forces and actors: Four conceptual models. Ecology and Society, 15(4), 1.

- Hicks, W.W. (1967). Agricultural development in northern Mexico, 1940–1960. Land Economics, 43(4), 393–402.

- Hruska, T., Toledo, D., Sierra-Corona, R., & Solis-Gracia, V. (2017). Social–Ecological dynamics of change and restoration attempts in the Chihuahuan Desert grasslands of Janos biosphere reserve, Mexico. Plant Ecology, 218(1), 67–80.

- Humphries, S. (1998). Milk cows, migrants, and land markets: Unraveling the complexities of forest-to-pasture conversion in northern Honduras. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 47(1), 95–124.

- INEGI. (1999). Chihuahua - tabulados basicos de ejidales por municipio: PROCEDE 1992–1998. Aguascalientes: Author.

- INEGI. (2015). Encuesto nacional agropequario 2014: Existencias de ganado bovino según calidad de ganado por entidad federativa. Retrieved from http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/encuestas/agropecuarias/ena/ena2014/doc/tabulados.html

- INEGI. (2016). Panorama sociodemografico de Chihuahua 2015. Mexico: Author.

- INEGI [Instituto Nacional de Estadistico y Geographia – Mexico]. (1986). Anuario estadístico del Estado de Chihuahua, 1985 – Tomo II. Mexico: INEGI.

- Jepson, W. (2006). Private agricultural colonization on a Brazilian frontier, 1970–1980. Journal of Historical Geography, 32(4), 839–863.

- Jepson, W., Brannstrom, C., & Filippi, A. (2010). Access regimes and regional land change in the Brazilian Cerrado, 1972–2002. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 100(1), 87–111.

- Klepeis, P., & Turner, I.I, B.L. (2001). Integrated land history and global change science: Theexample of the southern Yucatán Peninsular region project. Land Use Policy, 18(1), 27–39.

- Klooster, D. (2003). Forest transitions in Mexico: Institutions and forests in a globalized countryside. The Professional Geographer, 55(2), 227–237.

- Lambin, E.F., Geist, H.J., & Lepers, E. (2003). Dynamics of land-use and land-cover change in tropical regions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 28(1), 205–241.

- Lambin, E.F., Turner, B.L., Geist, H.J., Agbola, S.B., Angelsen, A., Bruce, J.W., … Folke, C. (2001). The causes of land-use and land-cover change: Moving beyond the myths. Global Environmental Change, 11(4), 261–269.

- Lewis, J. (2002). Agrarian change and privatization of ejido land in northern Mexico. Journal of Agrarian Change, 2(3), 401–419.

- Lindenmayer, D.B., & Fischer, J. (2013). Habitat fragmentation and landscape change: An ecological and conservation synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Liverman, D.M., & Vilas, S. (2006). Neoliberalism and the environment in Latin America. Annual Review of Environmental Resources, 31, 327–363.

- Luers, A.L., Naylor, R.L., & Matson, P.A. (2006). A case study of land reform and coastal land transformation in southern Sonora, Mexico. Land Use Policy, 23(4), 436–447.

- McCusker, B. (2004). Land use and cover change as an indicator of transformation on recently redistributed farms in Limpopo province, south Africa. Human Ecology, 32(1), 49–75.

- Meyers, T. (2017). Red and green on the border: The nature and technology of southern new Mexico’s chile peppers. In S. Evans (Ed.), Farming across borders: A transnational history of the north American West (pp. 122–147). College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

- Morton, D.C., DeFries, R.S., Shimabukuro, Y.E., Anderson, L.O., Arai, E., Del Bon Espirito-Santo, F., … Morisette, J. (2006). Cropland expansion changes deforestation dynamics in the southern Brazilian Amazon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(39), 14637–14641.

- Myhre, D. (1998). The achilles’ heel of the reforms: The rural finance system. In W.A. Cornelius & D. Myhre (Eds.), The transformation of rural Mexico: Reforming the ejido sector (pp. 39–68). La Jolla: Center for US-Mexico Studies, University of California, San Diego.

- Ortega-Ochoa, C., Villalobos, C., Martínez-Nevárez, J., Britton, C.M., & Sosebee, R.E. (2008). Chihuahua’s cattle industry and a decade of drought: Economical and ecological implications. Rangelands, 30(6), 2–7.

- Otero, G. (Ed.). (1996). Neoliberalism revisited: Economic restructuring and Mexico’s political future. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Pacheco, P. (2006). Agricultural expansion and deforestation in lowland Bolivia: The import substitution versus the structural adjustment model. Land Use Policy, 23(3), 205–225.

- Paul, E.A., Paustian, K.H., Elliott, E.T., & Cole, C.V. (Eds.). (1996). Soil organic matter in temperate agroecosystems: Long term experiments in North America. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Piquer-Rodríguez, M., Butsic, V., Gärtner, P., Macchi, L., Baumann, M., Pizarro, G.G., … Kuemmerle, T. (2018). Drivers of agricultural land-use change in the Argentine Pampas and Chaco regions. Applied Geography, 91, 111–122.

- Pool, D.B., Panjabi, A.O., Macias-Duarte, A., & Solhjem, D.M. (2014). Rapid expansion of croplands in chihuahua, Mexico threatens declining north American grassland bird species. Biological Conservation, 170, 274–281.

- Ribot, J.C., & Peluso, N.L. (2003). A theory of access. Rural Sociology, 68(2), 153–181.

- Robbins, P. (2012). Political ecology: A critical introduction (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Rochin, R.I. (1985). Mexico’s agriculture in crisis: A study of its northern states. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 1(2), 255–275.

- Sanderson, S.E. (1981). Agrarian populism and the Mexican state: The struggle for land in Sonora. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Sawatzky, H.L. (1971). They sought a country: Mennonite colonization in Mexico. In With an appendix on Mennonite colonization in British Honduras. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Schmook, B., & Vance, C. (2009). Agricultural policy, market barriers, and deforestation: The case of Mexico’s southern Yucatán. World Development, 37(5), 1015–1025.

- Scott, C.A. (2011). The water‐energy‐climate nexus: Resources and policy outlook for aquifers in Mexico. Water Resources Research, 47(6), W00L04.

- Scott, C.A., & Shah, T. (2004). Groundwater overdraft reduction through agricultural energy policy: Insights from India and Mexico. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 20(2), 149–164.

- Secretaria de Desarrollo Rural. (2013). Resumen municipal - municipio janos. Retrieved from http://www.microrregiones.gob.mx/catloc/LocdeMun.aspx?tipo=clave&campo=loc&ent=08&mun=035

- Secretaria de Econamia, Direccion General de Estadistica. (1954). Anuario estadistico de los estado unidos Mexicanos, 1951–1952. Mexico D.F.: Secretaria de Economia, Ofecina de Inventarios, Almacenes, y Publicaciones.

- Southgate, D. (1990). The causes of land degradation along” spontaneously” expanding agricultural frontiers in the third world. Land Economics, 66(1), 93–101.

- Spera, S.A., Galford, G.L., Coe, M.T., Macedo, M.N., & Mustard, J.F. (2016). Land‐use change affects water recycling in Brazil’s last agricultural frontier. Global Change Biology, 22(10), 3405–3413.

- Téllez, L. (Ed.). (1993). Nueva legislación de tierras, bosques, y aguas. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, México.

- Tsing, A.L. (2003). Natural resources and capitalist frontiers. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(48), 5100–5106.

- Turner, B.L., & Robbins, P. (2008). Land-change science and political ecology: Similarities, differences, and implications for sustainability science. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 33, 295–316.

- Valsecchi, M. (2014). Land property rights and international migration: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 110, 276–290.

- Vasquez Castillo, M.T. (2004). Land privatization in Mexico: Urbanization, formation of regions, and globalization in ejidos. New York: Routledge.

- Walker, R. (2004). Theorizing land-cover and land-use change: The case of tropical deforestation. International Regional Science Review, 27(3), 247–270.

- Walker, R., Browder, J., Arima, E., Simmons, C., Pereira, R., Caldas, M., … de Zen, S. (2009). Ranching and the new global range: Amazônia in the 21st century. Geoforum, 40(5), 732–745.

- Walsh, C. (2008). Building the borderlands: A transnational history of irrigated cotton along the Mexico-Texas border (Vol. 22). College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

- Wasserman, M. (1984). Capitalists, caciques, and revolution: The native elite and foreign enterprise in Chihuahua, Mexico, 1854–1911. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Wasserman, M. (2015). Pesos and politics: Business, elites, foreigners, and government in Mexico, 1854–1940. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Weinhold, D., & Reis, E. (2008). Transportation costs and the spatial distribution of land use in the Brazilian Amazon. Global Environmental Change, 18(1), 54–68.

- Whiteford, S., Bernal, F.A., Diaz-Cisneros, H., & Valtierra-Pacheco, E. (1998). Arid-land ejidos: Bound by the past, marginalized by the future. In W.A. Cornelius & D. Myhre (Eds.), The transformation of rural Mexico: Reforming the ejido sector (pp. 381–400). La Jolla: Center for US-Mexico Studies, University of California, San Diego.

- Wilcove, D.S., Rothstein, D., Dubow, J., Phillips, A., & Losos, E. (1998). Quantifying threats to imperiled species in the United States. Bioscience, 48(8), 607–615.

- Yunez–Naude, A. (2003). The dismantling of CONASUPO, a Mexican state trader in agriculture. World Economy, 26(1), 97–122.