ABSTRACT

Sketch-map-facilitated interviews were conducted in 23 villages in two adjacent regions in the southern Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico – the Maya (and increasingly Mennonite) forest-agriculture mosaic of the Chenes, and the late-20th-century-settlement forest frontier of Calakmul – to determine the frequency and typology of local-scale reserves, including the external (e.g. Payments for Environmental Services programs) and internal sources of their generation. 9% of the study communities are found to satisfy the author’s criteria for deliberate, autochthonous reserves. The static polygon reserve and static map are found to have limited value for understanding the evolving cultural ecologies of these regions. Alternative approaches are discussed, particularly those employed by geographers.

Introduction

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, a growing number of scientists and policymakers have turned their attention to village-scale forest reserves (Brockington, Citation2007; Kitamura & Klapp, Citation2013). They consider these and other locally managed protected areas as potentially more effective environmental conservation tools than large, state-driven parks: less prone to apathy or resistance (Ruiz-Mallén et al., Citation2014; Wily & Dewees, Citation2001), and, as a dispersed system, more flexible in responding to climate change (Hannah et al., Citation2007). These are defined here as: 1) static polygons (areas with clearly defined, enduring boundaries); 2) covered primarily in mature forest; 3) between typical patch and landscape scales, responsive to ‘individual forest management actions’ (Fischer, Citation2018, p. 139), interpreted herein as larger than approximately 5 ha; 4) with land uses restricted by village rules (written or unwritten).

Fewer studies focus on a subset of these: deliberate, autochthonous village-scale forest reserves (DAVFRs), with additional criteria: 5) deliberately set aside as forest, not merely left over by accident or neglect; and 6) independently established without (or before) the external influence of a government, NGO, or commercial conservation program. These measures are rarely sharply defined; rather, they exist along continuums. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) includes one reserve category that is unambiguously deliberate and autochthonous: the ‘sacred natural site’ (Martin et al., Citation2011, p. 259). DAVFRs are possibly more effective and durable conservation instruments than other local reserves. If reserves arise primarily from pre-existing cultural practices, village residents may be more likely to acknowledge their existence and accept them (Ruiz-Mallén & Corbera, Citation2013), and more likely to participate in their management (Méndez López, García-Frapolli, Ruiz-Mallén, Porter-Bolland, & Reyes-García, Citation2015, p. 697). This may safeguard against corruption and inequitable distribution of benefits from reserves (Brockington, Citation2007). Additionally, DAVFRs are intrinsically interesting as cultural geographic practices within systems of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). They may be co-opted by state or commercial initiatives that transform their local meanings (Appau Asante, Aababio, & Boaykye Boadu, Citation2017), or else play a key role within an externally initiated conservation system (Becker & Ghimire, Citation2003).

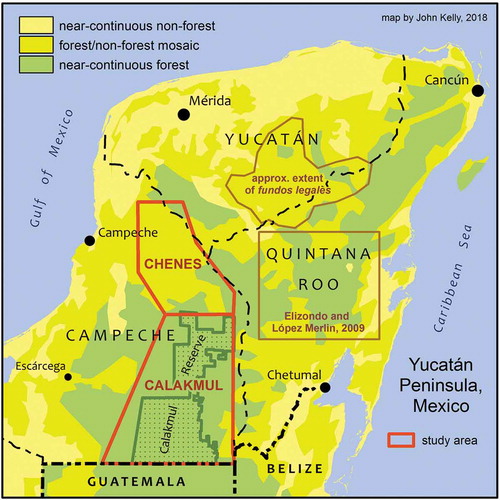

This study documents DAVFRs and government-certified village-scale forest reserves among a sample of villages in two contiguous areas in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico (): 1) the Chenes region, where indigenous Maya have long occupied a forest-agriculture mosaic landscape, south of the peninsula’s ‘ecumene’ (i.e., a predominantly agricultural and/or urbanized core region, where economic power and national culture are concentrated); 2) the Calakmul forest region further south, where non-indigenous, late-20th-century settlers carved out a ragged colonization front in the vicinity of a large biosphere reserve established in 1989 (Turner, Geoghegan, & Foster, Citation2004). One additional study village (in the Chenes mosaic landscape region) was founded during a third phase of settlement: Mennonites migrating from northern Mexico, principally since 2005 (Ellis, Romero Montero, Hernández Gómez, Porter-Bolland, & Ellis, Citation2017, p. 477).

Figure 1. Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico: the Chenes and Calakmul study areas, the location of Elizondo and López Merlín (Citation2009) study, and the approximate extent of fundos legales (periurban multiuse forest reserves, sensu Levy Tacher et al., Citation2016). Land cover classes based on ‘tree cover’ layer in Hansen et al. (Citation2013), ‘intact forest landscape’ layer in Greenpeace (Citation2013), and author’s interpretation of 2018 LANDSAT imagery.

All the study’s Maya Chenes villages, and all but two of its Calakmul villages, are collectively-titled ejidos. The social property system (ejidos and, in some indigenous regions, similar territories called comunidades agrarias) was implemented throughout Mexico mainly between 1930 and 1992, and today covers about 45% of the country’s land area with vegetative cover (Alix-García et al., Citation2018, p. 7017). Neoliberal counter-reforms since 1992 have weakened the system nationally by introducing privatisation options, but most ejidos in the Yucatán Peninsula avoided full privatisation. They certified only the perimeters of their territories, not internally distinct areas such as zones with individual agricultural parcels (Morett-Sánchez & Cosío-Ruíz, Citation2017). In predominantly forested areas like Calakmul, more complete privatization was limited by legal restrictions (Haenn, Citation2006, p. 141). In Yucatán state, this retention of social property tenure was by choice (Torres-Mazuera, Citation2014). In contrast, Chenes Mennonite villages are collections of individual private properties (Ellis et al., Citation2017).

The Chenes and Calakmul study areas ostensibly embody two concepts of the settlement frontier: the culturally and ecologically stable forest-agriculture mosaic, and the recently populated, dynamic forest zone (Angelsen & Rudel, Citation2013). The objectives of this study were to find: 1) if deliberate, autochthonous village-scale forest reserves exist in the study areas, and 2) are more abundant in one zone or the other, relative to government-certified reserves (GCRs). Secondary objectives were to: 1) document any subtypes (classes) of DAVFRs and GCRs, 2) learn what the term ‘reserve’ means locally, and 3) document any decline in DAVFRs as a cultural practice (e.g. through loss of tree cover, or transformation into purely GCRs, or a lack of interest among younger villagers).

I hypothesized that deliberate, autochthonous, village-scale forest reserves exist in both areas, but are more common among the Chenes Maya villages, where they are one cultural practice contributing to the spatial patterns of the forest-agriculture mosaic, though perhaps declining in some communities. I hypothesized that the Calakmul forest frontier would contain a greater proportion of government-certified reserves, where unintentionally remnant ‘excess’ forest would draw the attention of external (including state-driven) conservation programs. These hypotheses arose from experiences in 1999–2000, when I initiated a remote sensing analysis and ethnographic fieldwork with geographer Gerardo García Gil (now at the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán). We noted that several Calakmul communities claimed to maintain parts of their territories as ‘ejido reserves’ of varied origins.

These predictions were found to be incorrect. The Chenes mosaic area, more than the Calakmul forest frontier, proved to be the locus of important cultural and forest cover change, necessitating an additional study community – a Mennonite village – during the 2017 field visit. Few unambiguous DAVFRs were found in either study area, while government-certified reserves were common in both of them, particularly areas set aside through the federally administered Payment for Environmental Services (PES) program, initiated in 2003 (see Results section for a more detailed description).

After introducing the study areas and existing literature on village-scale forest reserves there, I briefly summarize geographical approaches to characterizing the forest frontier. A description of methods follows. The results for reserves in both study areas are presented, followed by additional information about the two principal cultural groups within the Chenes area (Mennonite and Maya).

While reviewing the findings, the constraint of the ‘reserve’ as a static polygon emerged as a productive theme for exploring theoretical approaches to understanding human-environment interactions along the forest frontier gradient. Residents in both study areas likely employ deliberate, autochthonous, village-scale forest management practices, but not necessarily in the form of forest reserves. When applying their findings to conservation, social and biological scientists often focus on what is easy to illustrate on a fixed map, ‘avoiding the “messiness” of reality’ and the perceived ‘unreliability’ of the indigenous, local perspective (Piper, Citation2002, p. 13). State-sanctioned tools for land use control are often constrained by Euclidean conceptions of space and property as fixed and sharply bounded (Adams & Hutton, Citation2007; Crampton & Krieger, Citation2010; Harley, Citation1989; Vaccaro, Beltran, & Paquet, Citation2013). This theme is explored in the Discussion section.

The study areas

The largest forest cores in lowland tropical Mexico are Chimapalas (Oaxaca and Chiapas states), Lacandon (Chiapas), and the Selva Maya of the southern Yucatan Peninsula (Campeche and Quintana Roo states). In Mexico the Selva Maya is known as the Calakmul region, and it continues into Guatemala as the Peten region. From each of these forest cores, an ecumene extends in several directions. Between each forest core and ecumene is a gradient of regions, each embodying varied facets of the frontier through its landscape dynamics and settlement histories; e.g. geographer Susanna Hecht (Citation2008, p. 146) classifies these as environmental, socio-environmental, agro-industrial, and peasant landscapes.

In the Yucatan Peninsula, the principal ecumene comprises most of Yucatán state (), a stable core of human settlement on the peninsula since the Precolumbian period (Henderson, Citation1981). East of the Calakmul forest core in south-central Quintana Roo state lies another region of stable indigenous settlements, but with a high percentage of forest cover and large-area ejidos. Located between the Calakmul and Sian Ka’an biosphere reserves, its forests are a focus of the Corredor Biológico Mesoamericano (Mesoamerican Biological Corridor), a collection of government studies and programs initiated in the 2002 (Robles de Benito, Citation2009, p. 53).

The two study areas of this paper lie south of the Yucatan state ecumene, in the eastern half of Campeche state. The more northerly study area is the forest-agriculture mosaic known as the Chenes (many of its villages end in the Yucatec Maya word chen, meaning ‘well’ or ‘watering hole’), where indigenous ejidatarios practice a blend of swidden and mechanized, permanent agriculture, including maize and apiculture (honeybees) (Schüren, Citation2003, p. 51). To its south is the Calakmul region; here, mainly in the 1980s, non-indigenous settlers from many parts of Mexico established precarious farming activities along three highways, during the terminal, ‘internal colonization’ phase of Mexico’s social property land reform program (García Gil & Pat Fernández, Citation2000, p. 215)Footnote1. The southern Yucatan Peninsula region overall lost significant forest cover to cropland and cattle pasture between 1991 and 2007 (Galvan-Miyoshi, Walker, & Warf, Citation2015, p. 765), but deforestation rates specifically in the Calakmul region have slowed since about 2000, with some areas undergoing forest regrowth, as many smallholders have abandoned their farms, some of them relying more apiculture (Ramírez-Delgado, Christman, & Schmook, Citation2014). This mélange of forest cover dynamics parallels the complex, multi-scale links among people and their livelihoods. While proponents of the Forest Transition Model have characterized any regrowth as a mere effect of rural-to-urban migration, conceptual dichotomies such as ‘rural vs. urban,’ ‘unoccupied vs. settled,’ and ‘migrant vs. stable resident’ are oversimplifications (Hecht, Citation2008, p. 144; Hecht, Yang, Sijapati Basnett, Padoch, & Peluso, Citation2015).

Starting in the 1980s but principally after 2000, many of the national and private parcels between the Chenes Maya ejidos territories were purchased and settled by Mennonites: Mexican citizens of Anabaptist German origin, many of them fleeing the insecurity related to drug trafficking in the northern Mexican borderlands (Acosta Pacheco, Citation2011). These Mennonite ‘colonos’ have been replacing many forest patches with mechanized, permanent, input-intensive soy and sorghum farms (Ellis et al., Citation2017).

Background: DAVFRs in the Yucatan Peninsula

To my knowledge, the one documented example of deliberate, autochthonous village-scale forest reserves in the Yucatan Peninsula in the 21st century are the fundos legales: multi-use forest reserves at the margins of some village centers (Cob-Uicab, Granados-Sánchez, Arias-Reyes, Álvarez-Moctezuma, & López-Ríos, Citation2003; Levy Tacher et al., Citation2016; Rodríguez-Sánchez, Levy Tacher, Ramírez-Marcial, & Estrada-Lugo, Citation2019). Another study, of ejido forest reserves in part of Quintana Roo state (Elizondo & López Merlín, Citation2009), less conclusively identified several of them as partially deliberate and autochthonous.

In the centuries before the Mexican Revolution, a fundo legal was the village center granted by the government to an indigenous community for their homes and solares (backyard gardens) (Castro Gutiérrez, Citation2015). They are the antecedents for what are called zonas urbanas (urban zones) or asentamientos humanos (human settlements) in the post-1920 social property system. In certain places in Mexico, where the fundo legal was larger than the area required for houses and other buildings, the leftover ring-shaped land was maintained as a community forest reserve for firewood, fruits, and sometimes construction materials (Levy Tacher et al., Citation2016, p. 304) – a greenbelt between the village center and the area of agricultural parcels.

The forest frontier of south-central Quintana Roo state () resembles the Chenes in that most ejidos have long, relatively stable histories and an indigenous Maya culture, but it also is like Calakmul in that most ejidos contain large forest patches, with each household allotted many more hectares than can typically be farmed. This combination enabled commercial forestry to flourish, first to private concessions, and after 1986 largely through community forest enterprises (CFEs) (Ellis et al., Citation2015, p. 4301). Assisted by a German government development grant, permanent forest areas (areas forestales permanents, or AFPs) with sustainable forest product harvest practices were established in 50 ejidos through the Plan Piloto Forestal (PPF) program. In 1992 the PPF model was extended to the Calakmul forest region, where about 30 Calakmul ejidos also designated AFPs (Boege, Citation1993, p. 114). Because Calakmul’s ejidos were more recently established, their populations more transient, and the best commercial already logged by pre-1980s foreign companies (Haenn, Citation2005, p. 12), few of its AFPs were used for systematic, sustainable community timber harvesting. Instead, they became informally managed sites for apiculture, hunting, non-timber forest products like xate, an ornamental palm plant.Footnote2

In 2009, Cecilia Elizondo and David López Merlín issued a report for Mexico’s national biodiversity commission, CONABIO, on village-scale forest reserves in this region of Quintana Roo state. Reserves were defined broadly, varied greatly in size, history, and purpose, and were usually located far from the village centre. Any predio (property or piece of land) was included if its use was controlled or restricted by the village, either explicitly (through its assembly) or implicitly. Especially in the foreword by cultural ecologist Victor Toledo, the report acknowledges that not all local forest-sustaining practices can be captured by static polygons. Nevertheless, the report features maps depicting the reserves as static polygons with uniform cartographic symbology.

The authors focused on the ‘easily mapped’ because a goal was to help launch a new government program: Áreas de Conservación Voluntaria (ACVs), later changed to Áreas Destinadas Voluntariamente a la Conservación, or Areas Voluntarily Dedicated to Conservation (AVDCs). In 2008, Mexico’s federal Natural Protected Areas Commission (CONANP) added this category to its menu of protected area types (Elizondo and López Merlin Citation2009, p. 25). The ADVC evolved from a collection of concepts such as the ‘ejido reserve’; land owned or managed by a conservation NGO; the UMA (wildlife management unit, often for commercial sport hunting); and the Forest Stewardship Council-certified forested area (Anta, Citation2007). ‘An important aspect of the AVDC is that the communities themselves are responsible for decision-making, although they may act under the advice of, or in collaboration with, external actors’ (Méndez-López, García-Frapolli, Ruiz-Mallén, Porter-Bolland, & Reyes-Garcia, Citation2015, p. 695). In contrast to a PES set-aside, registry as an AVDC does not automatically entail government payments, but nor does it necessarily entail state-enforced land use restrictions, but ‘in the future will be accompanied by funds directed toward management of the area’ (p. 698).

Of the 50 ejidos visited, 49 had some kind of reserveFootnote3, and 35% of these had approved their reserve(s) in a village assembly. Some had declared their reserves during a 1977–83 federal program called Coplamar (Elizondo & López Merlín, Citation2009, p. 41).

Background: geographical approaches to characterizing the forest frontier

The academic discipline of geography embraces a broad range of scholarly and practical approaches to understanding human-environment interactions. Most geographers use and produce maps in their research and applied work, though less often in published articles than before 1990 (Kessler & Slocum, Citation2019, p. 25), but their methods and theoretical frameworks are rarely limited to easily mapped artefacts like the static polygon reserve. Since the 1980s, building on a much longer familiarity with multiscale flows and linkages (Meyfroidt, Lambin, Erb, & Hertel, Citation2013), geographers have helped lead the social and geosciences toward elucidating cultural and economic marginalization and inequality (Finn & Hanson, Citation2017). This has included a critique of the static polygon (on a map, and on the land) as an instrument of the state-supported neoliberalism (Rankin, Citation2009; Wainwright & Bryan, Citation2009). Geographers were among the first to call attention to the harmful social histories and territorial rights violations of ‘fortress conservation’ reserves (Neumann, Citation2002).

Geographers have also documented resistance to (and creative engagement with) state- and market-sanctioned property regimes (Kelly, Citation2013). Some emphasize that static-polygon-defined territorial rights have benefited indigenous peoples, and cooperation among indigenous peoples and ‘colonization front’ settlers at the forest frontier (Herlihy & Tappan, Citation2019). The Calakmul region’s land use dynamics, land management practices, and agricultural economics were the subject of numerous studies during the 1990s and 2000s Southern Yucatán Peninsular Region (SYPR) project, directed by geographer Billie Lee Turner (Turner, Geoghegan, & Foster, Citation2004), and by other social and political scientists, notably anthropologist Nora Haenn. In the Chenes region, forest cover change and Maya-Mennonite cultural and economic tensions and cooperation have been investigated by a team lead by Edward Ellis of the Universidad Veracruzana, and by Jovanka Spiric of the Universidad Autónoma de México (UNAM) Centro de Investigaciones en Geografía Ambiental (Environmental Geography Research Center). These researchers typically employ some blend of qualitative or quantitative social techniques (e.g. participatory mapping-facilitated field interviews) with physical data (e.g. remote sensing-derived land use/land cover).

Village-scale forest reserves are just one possible component of the frontier cultural landscape, but where they exist, they potentially intersect several facets of the theoretical framework informing this paper. This approach suffuses geographer Susanna Hecht’s (Citation2008) (p., p. 147) description of the ‘socio-environmental rubric of land holding,’ in which the ‘ethnic-cultural terrain’ is understood in the ‘context of environmental and human rights.’ Hecht notes that the term ‘reserve’ has come to mean not just the exclusionary eco-park, but also (in some places) the self-governed indigenous territory (see, e.g. Kelly, Herlihy, Tappan, Hilburn, & Fahrenbruch, Citation2017). These communities simultaneously ‘critique modernization’ through practices arising from place-based traditional knowledge, and ‘interact strongly with international and national interlocutors.’ Anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz-Adler (Citation1992), as summarized by Nora Haenn (Citation2005, pp. 27–28), offers further insights on how the cultural landscape qualities of a particular region (e.g. a forest frontier) are (re)produced through local governance. Village and regional norms (including explicit rules and implicit communication styles) channel individual and community interactions with the physical environment, but these activities and perceptions are partly constrained by the state’s (i.e. the government’s) efforts to impose a uniform land use and land tenure model on all regions in its domain. As Jesse Ribot and Nancy Peluso (Citation2003) postulated in an influential paper, access – ‘the ability to derive benefits from things’ – does not automatically arise from territory-based property rights.

Materials and methods

In 2016 (four weeks in the Calakmul region) and 2017 (eight days in the Chenes region), I conducted semi-structured interviews, questionnaires, and sketch mapping exercises with village residents in 23 villages: 16 in Calakmul, and 7 in Chenes (including one Mennonite settlement). Typical participants were a comisariado ejidal (ejido leader) or equivalent, and two to five others, usually adult males. Because one initial interest was the effect of proximity to the Calakmul biosphere reserve on local reserves, I began my selection by identifying all Calakmul localities within 15 km of its eastern border. I discarded ten on which similar, recent work had been published; included seven where I had done initial fieldwork in 1999; and added four that were subjects of Haenn’s study (Citation2006) on dividing up of de facto common lands. In the Chenes, I tried to include a range of community sizes (land areas) within the small sample.

To begin each session, after I had familiarized myself with the approximate ejido boundaries through the GAIA GIS layer (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática [INEGI], Citation2012), I used Google Earth images to help orient the participants and myself to forest/non-forest land use patterns. On a 120-by-90-cm sheet of blank paper, I asked the participants to draw the boundaries of their community, and to fill the sketch map with all toponyms (place names). The aims of this participatory mapping exercise (adapted from Herlihy & Knapp, Citation2003) were to: 1) stimulate collective knowledge of the places that might be considered reserves; 2) orient me to the approximate locations and relative sizes of potential reserves; 3) expedite appropriate follow-up questions (e.g. if a forest patch was close to the village center, it might receive closer scrutiny as potentially deliberate); 4) possibly elicit unanticipated indications of individual or collective cognitive maps of a village territory; 5) create an opportunity for new research questions to arise (e.g. renting to Mennonites in some Chenes communities).

To avoid biasing the responses by using the word ‘reserve’ (reserva), but rather to potentially capture a broad range of reserve types and to ascertain how they arose, conversations followed a template (see Appendix 1, the English translation of the original guide). They began with current land uses (e.g. ‘what is the most common or popular land use?’), followed by where certain land uses were restricted or not practiced, and why. If the conversation stalled, set prompts were offered (e.g. ‘was there an deliberate decision to restrict land uses there, or is it merely land left over, e.g. too far from the village for productive activities that require conversion from forest?’; or, ‘why did you stop that particular land use there?’). If a possible reserve was identified, its past status was discussed, including if it predated any government-initiated, polygon-specific conservation activity.

The topic of formally declared or registered reserves was discussed next (e.g. ‘Are these rules written in the ejido laws?,’ and ‘Have these rules been shared with some government agency or NGO?’). The next questions related to how the reserve benefited the community, with prompts (if necessary) including ‘for firewood?,’ ‘for abundant and clean water?,’ or ‘for future individual parcels, if the population grows?’; and, if the reserve ‘belonged to the community as a whole’ (i.e. a de facto common use area). Finally, I asked ‘What do the words “reserve” and “protected area” mean to you?,’ and if they used the word ‘reserve’ for the previously identified locations.

In the Chenes region, an additional question was added to the same semi-structured interview: ‘Do you rent land to Mennonites; and if so, where?’ In two Calakmul communities, GPS points were taken to locate important features in the sketch map.

The interview material was analysed through a simple count of answers I understood to be roughly equivalent; e.g. ‘servicios ambientales’ (environmental services) was equated with ‘pagos de CONAFOR,’ (payments from CONAFOR, the federal forestry commission co-administering PES); and, ‘maíz’ (corn) was equated with ‘milpa.’ Through informal content analysis, special attention was given to unsolicited comments related to the ‘socio-environmental rubric of land holding’ (Hecht, Citation2008, p. 147), particularly the perceived character of the regional landscape and changes to it.

Supplementary data collection

Deforestation rates in the Chenes region among Maya and Mennonite communities

Interviews in the Chenes ejidos indicated concern about land use changes on Mennonite properties. 40 GPS-located training points (half forest, the rest non-forest) were acquired in the field and compared to contemporary Google Earth imagery, and the points adjusted to 2000 and 2010 values with historical Google Earth imagery. 2000 and 2010 LANDSAT images were classed to forest and non-forest through a supervised maximum likelihood algorithm in ArcGIS 10.1 on bands 3, 5, 6, and 7. 116 social, private, federal, and unknown-status property polygons were digitized from Campeche State cadastral (property) maps (Instituto Catastral Citation2010a; Citation2010b). For all inhabited polygons not visited during fieldwork, web-based research was conducted to determine the culture (Maya or Mennonite) and, when appropriate, approximate settlement date. Each private-property village area was treated as a single polygon. When known from field visits, ‘Maya with land rentals to Mennonites’ was added as a polygon category. In ArcGIS, the forest/non-forest rasters were clipped, their areas and percent change in each calculated, and the percent change averaged across communities in each category.

Areas voluntarily dedicated to conservation (AVDCs)

The location and extent of AVCDs in both study areas, and their founding dates, were acquired in January 2019 through the CONANP (Natural Protected Areas Commission) interactive web map (advc.conanp.gob.mx).

Tentative identification of fundos legales in the Yucatán Península

Two sources were used: 1) On Google Earth imagery in April 2019, I located population centers displaying a land cover pattern resembling that of the seven ejidos described in (Levy Tacher et al., Citation2016), p. 2) I acquired shapefiles of social property tenure categories (common use, parceled, and human settlement zones) certified by the Registro Agrario Nacional (National Agrarian Registry) from its website (datos.ran.gob.mx). I noted that the apparent fundos legales coincided with a particular tenure morphology: land not in any of the three ejido internal categories (probably municipal, i.e. county-owned), surrounded by the ejido’s de jure common use area. I visually located the extent of this ejido type, to adjust the approximate boundary of fundos legales as DAVFRs.

Results

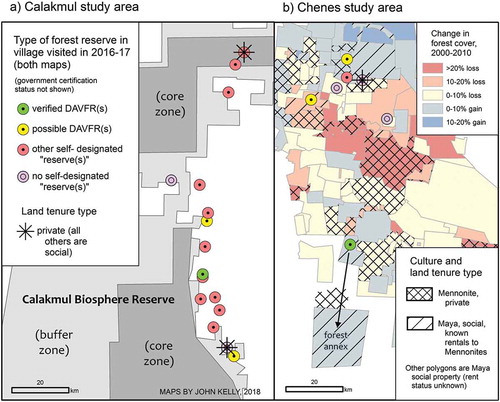

Key findings are presented in . Except where otherwise noted, data was obtained during the sketch mapping-facilitated field interviews.

Table 1. Frequency of village-scale reserve types in study communities, as documented in semi-structured, sketch-map-facilitated group interviews. DAVFR = deliberate, autochthonous, village-scale forest reserve. GCR = government-certified reserve.

Village-scale reserves in Calakmul and Chenes regions

Only two (9%) of the non-Mennonite villages included an unambiguously deliberate, autochthonous forest reserve (). An additional three (13%) contained a possible DAVFR (e.g. a forested archaeological site set aside before the PES program). The frequency of these reserves was similar in the indigenous Maya and non-indigenous settlement frontier regions. My hypothesis of a higher overall frequency, and of a higher frequency in Chenes than in Calakmul, was proven incorrect.

Figure 2. (a) Village-scale reserve types in the Calakmul study area; (b) Village-scale reserve types, land tenure classes, and forest cover change (2000–2010) in the Chenes study area. DAVFR = deliberate, autochthonous, village-scale forest reserve.

The two clear DAVFRs, one in each study area, arose in unusual circumstances. The Chenes Maya case is an ejido with two separate territories (): the standard agriculture-oriented polygon around the village center, and a much larger ampliación forestal (forest annexFootnote4) about 30 km further south, near where the Chenes region transitions to the Calakmul forest frontier. This gave the villagers the luxury of entering the federal government’s Payment for Environmental Services program (described below) on almost 3000 ha in the standard polygon, where hunting was not allowed, while maintaining the annex as a hunting reserve (part of it was already an UMA, or wildlife management area). The annex was unusually rich in local toponyms, supporting the sense that its care was well integrated into village culture.

The other deliberate reserve was in a Calakmul ejido with a long history of deep engagement with government and NGO conservation and development programs (I produced maps for a research botanist there in 1999; see also Burneo Mendoza, Citation2015). An informant said, ‘Our community is rather unusual. We well defined community conservation areas, even on individual [de facto] parcels.’ The same set-asides I observed in 20 years ago were ‘registered with the social property registry (RAN) around 2010ʹ (I have not determined the precise nature of this registration). The leaders of this village demonstrate creative engagement with the state to express local culture, in keeping with Hecht’s (Citation2008) ‘socio-environmental rubric.’

Government-certified, village-scale forest reserves (GCRs) were common in both study areas (). 82% were enrolled in the national Payment for Environmental Services program (PES; in Spanish, PSA), launched in 2003 to ‘offer annual payments of 20 to 80 dollars per hectare over 5-year periods to private and communal landowners, [who] must maintain existing forest or natural land cover and engage in land management activities such as building fences, controlling pests, or patrolling for illegal activity’ (Alix-García et al., Citation2018, p. 7016). Since 2009, the program has been considered a component of the United Nations-coordinated REDD+ initative to enhance forest carbon stocks (Spiric, Citation2015). The implementation of PES in Mexico has evolved, but in most cases the beneficiary must explicitly identify a static polygon: ‘the prospective participant submits an application along with … a map of the area to be included’ (Cortina & Porras, Citation2018, p. 4).

The interviews revealed that in all but one of the PES-enrolled villages, part or all of the PES-designated forest was ‘leftover land,’ already considered unsuitable at the time for productive activities that require removing trees. In Calakmul, where population densityFootnote5 is low, these ‘accidental reserves’ sometimes contained fertile soils, but were too remote to be worth exploiting. As one informant explained, ‘No one ever did farm work in the PES reserve; it’s too far away. It has good land, but everyone agreed to prohibit fire, clearing, and hunting there.’ In Chenes, excessive distance from the village center was sometimes a factor as well, but equally important was the clear distinction between rocky-soil uplands (cerros or monte) and more fertile flat areas (planadas). Informants in five of the six Chenes villages stated that increasing mechanization since around the 1990s facilitated the concentration of farming in the planadas and partial decline of swidden agriculture and ranching in the cerros. Calakmul residents also attested to increasing mechanization, but more often they attributed farmland-to-forest transition to out-migration (in half the villages), to the failure of commercial crops such as chili (see Keys & Chowdhury, Citation2006; Dobler-Morales, Chowdhury and Schmook, this issue), and to the increasing reliance on apiculture.

One Calakmul village included a large inadvertent forest reserve I had surveyed with theodolite and mapped in 1998. The ejidatarios had left it as de facto common use area (defined later in this section) because the government had accidentally granted them too much land; its status was resolved when it was converted to private property in 2006, owned jointly by a group of villagers.

In the Chenes ejidos, the average size of a PES set-aside is about 400 ha; in the Calakmul ones, it is about 1,000 ha. Ejidos in both regions kept parts of their forests outside their PES reserves because they did not want them subject to certain restrictions, e.g. hunting; or, the PES benefits had reached a per-person maximum; or, in one case, the community was considering clearing some forest in the future.

The Areas Voluntarily Dedicated to Conservation (AVDC) program has had a smaller impact on the study areas than PES. By 2018 Campeche had joined Oaxaca as a state with a relatively high number of them. Two of my Calakmul study area communities had AVDCs approved in 2017, after my field visits. One is entirely, and the other partly, within the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve buffer zone. Though both ejidos practice agriculture on part of their land, their entire polygons outside the urban zones were accepted as AVDCs, attesting to how this designation carries fewer restrictions (and fewer direct benefits) than PES. Through interviews with ejido authorities, in 1999 I had mapped the incidental reserves in one of these villages; they called them ‘forest reserves.’ By 2009, farming was more concentrated along the highway, leaving a slightly larger area for the PES reserve declared that year; also, the ejido’s population had increased considerably.

Besides PES and AVCD, another Mexican federal government program, the post-1915 social property system, may have essentially certified a village-scale reserve (though not necessarily for nature conservation) – but only if the ejido or comunidad chose to have all three intra-village land use categories (urban zone, area of individual parcels, and common use area) surveyed separately through the post-1992 PROCEDE action and its successor, FANAR (Smith, Herlihy, Kelly, & Ramos Viera, Citation2009). These de jure common use areas (CUAs) appear on the maps of the Registro Agrario Nacional (RAN).

If the ejido or comunidad instead chose to have only its outer perimeter surveyed and certified (or its perimeter and urban zone), its entire territory is legally a common use area. However, in practice most such villages do distinguish among de facto ‘common use’ and ‘individually parceled’ areas. De facto CUAs have varying degrees of formality (e.g. some create a map approved by the village assembly), and, like de jure CUAs, are used for a range of activities (typically including firewood and non-woody forest products) by individual ejidatarios or as an organized collective (Kitamura & Klapp, Citation2013).

As noted in the Introduction, RAN-certified internal distinctions such as de jure common use areas are uncommon in the Yucatan Peninsula. De facto CUAs () are more common; 64% of the study villages used the phrase during the sketch-map-facilitated interviews. The prevalence of de facto CUAs was one of the few clear distinctions between the two study areas. Only 56% of the Calakmul study villages included them. In the other Calakmul ejidos, the entire territory (other than a few small locations like a school parcel or certain water features) is understood to consist of parcels ‘belonging’ to individual ejidatarios, even if they are partly or entirely heavily forested (often including a PES set-aside). These late-20th-century settlers allocated most or all of their ejido land grant among individuals, even if only part of each de facto parcel would be farmed (the average parcel size is about 40 ha).

83% of the Chenes Maya villages included de facto common use areas in their sketch maps, usually coinciding with all or nearly all large forested areas. The preponderance of CUAs may partly be due to geology (Bautista, Batllori-Sampedro, Palacio-Aponte, Ortiz-Pérez, & Castillo-González, Citation2005, p. 35). In the Chenes zone, as noted above, there is a clear distinction between arable plains and rocky-soil hills (cerro), and typically ‘the cerro belongs everyone.’ One informant noted that this was true even in the past, when swidden agriculture and free-roaming ranching were more common in these hills. Increasing mechanization of farming in the planadas has reinforced the recognition of de facto individual parcels there. (Note that a de facto common use area is also a DAVFR only if the villagers consider it a ‘reserve’ to conserve tree cover, without external influence or before it).

Responses to the question ‘what does reserva mean to you?’ were of roughly four types, all occurring in both study areas. Five (23%) did not know or did not use the word; these are labelled ‘no self-designated “reserve(s)”’ in . These include one of the study’s two private-property ejidos; the private-property Mennonite village also lacks a reserve of any kind. Two (9%) associated ‘reserve’ solely with a government agency or NGO (e.g. ‘it’s PROARBOL’s help for ejidos that take care of the forest’). Five (23%) offered an alternative word or phrase (e.g. ‘we prefer “conservation area,” because some activities are allowed, like beekeeping and seed collection’).

In four (18%) of the exchanges, the informants spontaneously discussed the double meaning of the word: something set aside and left alone, and something saved for some future, active use, such as de facto individual parcels for farming (also noted in Elizondo & López Merlín, Citation2009, p. 39 in Quintana Roo communities).

This dual meaning was expressed in several ways. One group mentioned ‘conserving the forest, like for oxygen,’ and also ‘keeping something for the future, like a forest so our children will have what they need to build a house, and have apiaries.’ The private-property community with almost no forest cover defined it as ‘whatever is reserved for the people, that they might divide up in the future,’ without mentioning forest. A resident of the Calakmul ejido with the unambiguous DAFVR drew the sharpest distinction between the two meanings: “It’s either something untouchable, for conservation – no hunting or burning; or else it means a surplus, like an extra gas tank – with a potential purpose, in case something goes wrong.’

Apiculture (honey production) emerged as an important, unsolicited theme during most sketch mapping-facilitated interviews. In all of the Chenes villages conversations, and half of the Calakmul ones, apiculture was cited as a principal land-based activity. ‘Beekeepers, in particular, not only protect their forest but also advocate among their neighbors for forest conservation and the reduction of agrochemicals to protect a larger area where bees can find flowers and maintain the organic certification of their honey’ (Rodríguez-Solorzano, Citation2014, p. 1). Though sharply defined forest set-asides can be contribute to their success, bee colonies transcend the static polygon; their geometry is of points and fuzzy-bounded areas (Chemas & Rico-Gray, Citation1991).

Contrasting trajectories in apiculture help outline the socio-environmental characters of the two regions. Most Calakmul communities are increasingly embracing beekeeping; of five ejidos where I had mapped bee colonies in 2000, this was cited as a contributor to forest transition in four of them. While drought and market fluctuations are a concern, the overall sense is of a distinctively regional cultural practice on the rise.

In Chenes, villagers are anxious about the future of honey production. In four of the six villages, prolonged drought was cited as a reason for its decline. In two of these, use of airborne pesticides and herbicides by Mennonite neighbours was given as an equally important factor; and in one, loss of forest cover on Mennonite properties (see Echanove Huacuja, Citation2016).

Mennonites and Maya in the Chenes study area

While Mennonite chemical spraying and deforestation may not be the only factors contributing to apiculture decline among the Chenes Maya, this anxiety punctuates the changing cultural landscape of this forest-agriculture mosaic region. While my questionnaire dealt only with intra-village spaces and practices, the Mayan participants also talked about links (constructive and destructive) with their Mennonite neighbors. One group included in their sketch map a pond outside their ejido boundary, but considered as belonging to the community, until Mennonites purchased and plowed over the pond. Two others mentioned that they are renting out some ejido land to Mennonites looking to expand their mechanized production of soya and sorghum. In two ejidos, I was told that ‘Mennonites get along with us’; in one, an informant happily said that ‘some of them have been learning to speak Maya.’

On the last days of the field visit, I arranged to undertake the same sketch-mapping-facilitated exercise with one Mennonite community, and later to collaborate with a student, Annie McIntyre, in comparing forest cover change among Maya and Mennonite territories using LANDSAT imagery. Simultaneously, Edward Ellis et al. (Citation2017) published a similar study, and in 2018 Jovanka Spiric conducted fieldwork to explore themes of intercultural cooperation, tension, political economy (including wage labour), and landscape change.

The emerging picture is of two groups with different relationships to the state, the market, and the forest, but sharing a socio-environmental space, reconfiguring it and possibly each other. The Mennonite community I visited did not have a reserve or common use area of any kind, and Mennonites (I was informed) typically do not participate in PES for private landowners (‘we have nothing to do with agencies like CONAFOR’). The community’s forested uplands were individually parcelled, with a few hectares cleared for ranching but otherwise left alone. They do have assemblies rather like ejido meetings, and seek bank credit as a community, but each individual owns their own equipment (a Maya informant noted that, in several Mayan ejidos, a tractor was shared by a group).

The remote sensing exercise produced 2000–2010 mean annual forest cover change rates of −0.19% for ejidos overall, −0.47% for Mayan ejidos known to be renting to Mennonites, and −1.25% for Mennonite private-property villages (). Ellis et al. (Citation2017), using a study area with somewhat different boundaries, calculated 2005–2015 rates of −0.38% for ejidos overall and −1.48% for all private lands; both loss rates were about double those found for 1995–2005. Overall, our findings match up well, telling the same story of forest clearing by some new Mennonite communities, possibly linked (e.g. through land rental) to lower but similarly increasing loss rates in some Maya ejidos.

Geographic extent of the zone of fundos legales

Through a preliminary analysis, I estimated the approximate extent of this peri-urban reserve type within the Yucatan Peninsula. It seems to be restricted to an southeastern part of Yucatan state and a small area of Quintana Roo (); about 40% of the Maya ejidos within this zone clearly have them. The zone is comparable to the Chenes study area in its position along the ecumene – forest core gradient.

In 64% of my Chenes and Calakmul villages, informants mentioned and mapped a small community-managed parcel (occasionally left as forest) near the village center. Most were designated parcela escolar (a social property tool originally designed for growing crops to benefit the local school), the rest unidad agro-industrial de la mujer (a program promoted since 1970s, where ejido women could collaborate in productive activities) (Haenn, Citation2005, p. 95). None were identified as forest reserves per se, and so are not counted as DAVFRs; nonetheless, their land uses merit further study.

Discussion

Along the human settlement gradient between the national ecumene and the last large forest cores, the ‘socio-environmental rubric of land holding’ persists in rural Mexico, almost three decades after the partial weakening of its social property system began. Indigenous Maya and forest frontier settler communities creatively engage evolving markets, climate regimes, and government programs in diverse but broadly similar ways. The deliberate, autochthonous, static protected area for nature conservation simply is not a common strategy here. When the state employs similar tools (e.g. payments for environmental services), many communities readily participate, and the tools take physical forms in part arising from local practicesFootnote6. However, at least in eastern Campeche state, these behaviors tend to be practical (e.g, in Calakmul, avoiding long trips; in Chenes, maintaining uplands as de facto common use areas), rather than being embedded in (for example) spiritual beliefs (see Massey, Bhagwat, & Porodong, Citation2011). Yucatec Mayans (and non-indigenous settlers) in many places undoubtedly retain place-specific traditional practices that foster sustainable use of natural resources, but they are not easily mapped, so externally driven programs that focus on the static polygon will fail to engage them directly, and participation will likely be weak (Méndez-López et al., Citation2015). Instead, their practices tend to be ‘dynamic, flexible’ multiple-use systems (Barrera-Bassols & Toledo, Citation2005; García-Frapolli, Toledo, & Martínez-Alier, Citation2008).

My findings roughly matched those of Elizondo and López Merlin (Citation2009) in nearby Quintana Roo forest frontier settlements. In that study, local reserves formed through ‘initiative of the ejido’ were be noted as a special observation (p. 45); this applied to 6% of the reserves. At least 18% ejidos with reserves had not (yet) enrolled in the Payment for Environment Services program. These lower and upper bounds of one interpretation of ‘deliberate and autochthonous’ are similar to my 9 to 13% for the Chenes and Calakmul regions.

My quest for deliberate, autochthonous, village-scale forest reserves was largely unsuccessful, but the sketch map-assisted directed conversations did begin to shed light on how these frontier regions are evolving. Facets of Hecht’s socio-environmental rubric included critiques of modernity (e.g. Mennonite agrochemical use), and simultaneously working with and against the state (one of the few DAVFRs was in an ejido that values creative engagement with the state and NGOs). Attitudes toward government conservation programs included benign avoidance (Mennonites), satisfaction, frustration (in a Chenes ejido, ‘the Payment for Environmental Services area doesn’t belong to us anymore – we can’t even collect firewood’), and anger (in a Calakmul private-property village stuck in the biosphere reserve, ‘they forced us to stop farming – we even need permission for apiculture, and we’re the ones who took care of the forest – there weren’t any timber-sized trees left by the time we settled here!’).

This local resistance to the ‘fortress conservation’ model echoes critiques of protected areas as tools of state-driven neo-colonialism, by geographers and other scholars (Haenn, Citation2006; Neumann, Citation2002; Tauli-Corpuz, Citation2016). Some advocate the ‘cultural landscape as protected area’ approach (Farina, Citation2000). Others assert that even the late-20th-century innovation of ‘adaptive co-management’ (typically, biosphere reserves with sustainable-production buffer zones) may fail to ensure broad conservation-oriented participation among local residents (Schultz, Duit, & Folke, Citation2011). Others question the increasing official recognition of locally managed reserves (sometimes called ‘ICCA,’ for ‘indigenous peoples’ conserved territories and community conserved areas’) for its constraining tie to legally-defined land tenure polygons (Smyth, Citation2015).

Might deliberate, autochthonous reserves once have abounded in Chenes and Calakmul, but were co-opted or obscured by government programs like PES? While this remains a possible factor, the interview questions should have elicited memories of pre-PES reserves, if they existed. Certainly, both study areas have among the densest concentrations of PES communities in Mexico (Alix-García et al., Citation2018, p. 7017), being frontier areas where the state is most concerned about forest loss.

A more likely explanation for the scarcity of deliberate, autochthonous conservation localities was my confining the object of study to the static polygon, a poor tool for capturing a community’s web of interactivity with its forests (Porter-Bolland, Drew, & Vergara-Tonorio, Citation2006; Toledo, Citation2003). The static map and the fixed reserve are inadequate for modelling, illustrating, or promoting the complexities of human-environment interactions. Geographers often emphasize easily mapped polygons, yet they (and related scholars) are also adept at transceding its limitations. Examples of research in the study areas (represening a wide ranging body of work) include work on: managed secondary vegetation succession (Román-Dañobeytia, Levy-Tacher, Macario-Mendoza, & Zúñiga-Morales, Citation2014); microlandscapes within PES reserves (Ramírez-Reyes, Sims, Potapov, & Radeloff, Citation2018); and multiscale linkages driving economic marginalization and migration amid evolving land use patterns in Calakmul (Radel, Schmook, McEvoy, Méndez, & Petrzelka, Citation2012). Rather than the static polygon, these and other approaches to understanding cultural landscapes suggest the alternative definition of ‘reserve’ summoned by informants in several study communities: a resource ready to be activated into useful energy, should the need arise.

Conclusion

In eastern Campeche state, Mexico in the early 21st-century, a variety of local governance practices mediate human-forest interactions – not as isolated, pristine cultural artefacts, but embedded in active links with surrounding communities (e.g. recently established Mennonite settlements), and with state conservation programs. At the Calakmul frontier settlement zone nearest the forest core, after a few decades of carving out and experimenting with a place in the forest, a still young culture region is approaching a fairly stable state, with slow or absent net deforestation (Abel Vaca, Golicher, Cayuela, Hewson, & Steininger, Citation2012).

Currently the more dynamic, contentious region is the Chenes, an agriculture-forest mosaic between Calakmul and the old, stable, metropolitan ecumene. This marginal zone of the Yucatec Maya indigenous culture area is lower in population density and more heavily forested than the ecumene further north and west. Here, previously unoccupied property gaps (national lands) between the Maya social property territories (ejidos) are being filled by Mennonite agro-industrial (yet community-oriented) settlers, causing landscape change at a regional scale. It may be valuable to carry out a land use and cultural study of a similar forest frontier-ecumene gradient; e.g. the environs of the Chimalapas region, where the Mexican federal government plans to develop infrastructure across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Mexico News Daily, Citation2019; Lehmann & Backhouse, this issue). A comparison of village-scale forest management practices along the gradient should include, but not be limited to, static-polygon ‘reserves.’

Autochthonous Maya ejido forest reserves, even if plentiful, would have little effect on current changes to the Chenes regional landscape mosaic. PES set-asides merely provide modest financial support for communities where land use patterns were driven by other factors (e.g. geology, and the increasing reliance on mechanized agriculture). Neither Calakmul’s ‘overabundance’ of forest (with regard to practical use of large individual de facto parcels), nor the Chenes’ intra-community stable mosaic, lends itself to spontaneous, locally initiated forest set-asides.

Work on village-scale landscape management in Chenes should include multi-village practices. An overemphasis on intra-village ‘local reserves’ might fail to capture the opportunities for co-management represented by nascent intercultural collaborations.

Easily mapped protected areas (static polygons) are limited as a tool for investigating, illustrating, and supporting cultural ecologies, but they do have important uses. Fixed-polygon reserves can still be an effective mechanism for protecting sacred sacred sites and water sources. In the socio-environmental space of Campeche, the self-governing ‘territorial rights’ function of the ‘reserve’ (broadly defined) is fulfilled by the ejido, a remarkably durable cultural-territorial form despite post-1992 threats to its existence.

appendix_1.pdf

Download PDF (93.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Annie McIntyre, Gerardo García Gil, Jovanka Spiric, two anonymous reviewers, and the people of the Chenes and Calakmul regions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. All quotations originally in Spanish are translated by the author.

2. Xate (Chamaedorea spp.) is a palm commercialized as an ornamental.

3. In a smaller, preliminary 2004 study by the same authors, 44% of respondents defined ‘reserve’ as a place ‘for conservation,’ where ‘no extractive or economic activity could take place’ (26% disagreed). Thus, in 2009 active forestry enterprise AFPs were excluded from consideration, because their primary function was commercial (even if sustainable) rather than ‘natural’ (Elizondo & López Merlín, Citation2009, p. 37).

4. Forest annexes were granted to several Campeche ejidos in the 1940s, including about one-third of what would become the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve in 1989 (García Gil & Pat Fernández, Citation2000, p. 224).

5. The average ejido land area was about the same in both study areas (50 sq km), but the population averaged 720 in Chenes and 310 in Calakmul (www.microrregiones.gob.mx/catloc, consulted December 2018). According to informants, population is declining in half of the study villages.

6. See (McAffee & Shapiro, Citation2010) on how the state was forced to alter the PES program after popular opposition.

References

- Abel Vaca, R.A., Golicher, J.G., Cayuela, L., Hewson, J., & Steininger, M. (2012). Evidence of incipient forest transition in southern Mexico. PloS One, 7(8), e42309.

- Acosta Pacheco, M. (2011, April 11). Perseguidos en Chihuahua por narcos, migran a Campeche [Chased in Chihuahua by drug dealers, they migrate to Campeche]. Diario de Yucatán. [online newspaper].

- Adams, W.M., & Hutton, J. (2007). People, parks, and poverty: Political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conservation and Society, 5(2), 147–183.

- Alix-García, J.M., Sims, K.R., Orozco-Olvera, V.H., Costica, L.E., Fernández Medina, J.D., & Romo Monroy, S. (2018). Payments for environmental services supported social capital while increasing land management. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(27), 7016–7021.

- Angelsen, A., & Rudel, T.K. (2013). Designing and implementing effective REDD + policies: A forest transition approach. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 7(1), 91–113.

- Anta, S. (2007). Áreas Naturales de Conservación Voluntaria [Voluntary Natural Conservation Areas]. Study prepared for the Cuenca Initiative. [online].

- Appau Asante, E., Aababio, S., & Boaykye Boadu, K. (2017). The use of indigenous cultural practices by the Ashantis for the conservation of forests in Ghana. SAGE Open. doi:10.1177/2158244016687611

- Barrera-Bassols, N., & Toledo, V.M. (2005). Ethnoecology of the Yucatec Maya: Symbolism, knowledge and management of natural resources. Journal of Latin American Geography, 4, 9–41.

- Bautista, F., Batllori-Sampedro, E., Palacio-Aponte, G., Ortiz-Pérez, M., & Castillo-González, M. (2005). Integración del conocimiento actual sobre los paisajes geomorfológicos de la Península de Yucatán [Integration of current knowledge about geomorphological landscapes of the Yucatan Peninsula]. In F. Bautista & G. Palacio (Eds.), Caracterización y Manejo de los Suelos de la Península de Yucatán: Implicaciones Agropecuarias, Forestales y Ambientales (pp. 38–58). Coyoacán: Instituto Nacional de Ecología.

- Becker, C.D., & Ghimire, K. (2003). Synergy between traditional ecological knowledge and conservation science supports forest preservation in Ecuador. Conservation Ecology, 8(1), 1. [online].

- Boege, E. (1993). El desarrollo sustentable y la Reserva de la Biosfera de Calakmul, Campeche, México [Sustainable development and the Calakmul biosphere reserve, Campeche, Mexico]. Boletín de Antropología Americana, 28, 99–132.

- Brockington, D. (2007). Forests, community conservation, and local government performance: The village forest reserves of Tanzania. Society and Natural Resources, 20(9), 835–848.

- Burneo Mendoza, R.A. (2015). El Programa de Pago por Servicios Ambientales Hidrológicas en Calakmul: Respuestas Sociales de la Población de Narcizo Mendoza [The Payment for Hydrological Environmental Services in Calakmul: Social Responses of the Village of Narciso Mendoza] ( Master’s thesis in social anthropology). Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, Mexico City.

- Castro Gutiérrez, F.C. (2015). Los ires y devenires del fundo legal de los pueblos de indios [The comings and goings of the fundo legal of Indian villages]. In M. Martínez López-Cano (Ed.), De la Historia Económica a la Historia Social y Cultural: Homenaje a Gisela von Wobeser (pp. 69–104). Mexico City: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas.

- Chemas, A., & Rico-Gray, V. (1991). Apiculture and management of associated vegetation by the Maya of Tixcacaltuyub, Yucatán, México. Agroforestry Systems, 13(1), 13–25.

- Cob-Uicab, J.V., Granados-Sánchez, D., Arias-Reyes, L.M., Álvarez-Moctezuma, J.G., & López-Ríos, G.F. (2003). Recursos forestales y etnobotánica en la región milpera de Yucatán, México [Forest resources and ethnobotany in the milpa region of Yucatan, Mexico]. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente, 9, 11–16.

- Cortina, S., & Porras, I. (2018). Mexico’s payments for ecosystem services programmeCase Study Module 2. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Crampton, J.W., & Krieger, J. (2010). An introduction to critical cartography. ACME: an International Journal for Critical Geographies, 4(1), 1. [online].

- de Bonito, R.R. (2009). Las Unidades de Manejo para la Conservación de Vida Silvestre y el Corredor Biológico Mesoamericano México [Management units for wildlife conservation and the mesoamerican biological corridor]. Tlalpan: CONABIO.

- Echanove Huacuja, F. (2016). La expansión del cultivo de la soja en Campeche, México: Problemática y perspectivas [The expansion of soy cultivation in Campeche, Mexico: Issues and perspectives]. Anales De Geografía De La Universidad Complutense, 36(1), 46–69.

- Elizondo, C., & López Merlín, D. (2009). Las Áreas Voluntarias de Conservación en Quintana Roo [Voluntary conservation areas in Quintana Roo]. Tlalpan, Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

- Ellis, E., Romero Montero, J.A., Hernández Gómez, I.U., Porter-Bolland, L., & Ellis, P.W. (2017). Private property and Mennonites are major drivers of forest cover loss in central Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Land Use Policy, 69, 474–484.

- Ellis, E. A., Kainer, K. A., Sierra-Huelsz, J. A., Negreros-Castillo, Rodriguez-Ward, D., & DiGiano, M. (2015). Endurance and adaptation of community forest management in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Forests, 6, 4295–4327.

- Farina, A. (2000). The cultural Landscape as a model for the integration of ecology and economics. BioScience, 50(4), 313–320.

- Finn, J.C., & Hanson, A. (2017). Critical geographies in Latin America. Journal of Latin American Geography, 16(1), 1–15.

- Fischer, A.P. (2018). Forest landscapes as social-ecological systems and implications for management. Landscape and Urban Planning, 177, 138–147.

- Galvan-Miyoshi, Y., Walker, R., & Warf, B. (2015). Land change regimes and the evolution of the maize-cattle complex in neoliberal Mexico. Land, 4, 754–777.

- García Gil, G., & Pat Fernández, J.M. (2000). Appropriation of space and colonization in the biosphere reserve in Calakmul, Campeche, Mexico. Revista Mexicana del Caribe, 10, 212–231.

- García-Frapolli, E., Toledo, V., & Martínez-Alier, J. (2008). Adaptations of a Yucatec Maya multiple-use ecological management strategy to ecotourism. Ecology and Society., 13(2), 31. [online].

- Greenpeace. (2013). Intact forest landscapes, 2000/2013 (map data layer). Accessed through Global Forest Watch. Retrieved from www.globalforestwatch.org

- Haenn, N. (2005). Fields of power, forests of discontent: culture, conservation, and the state in Mexico. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Haenn, N. (2006). The changing and enduring ejido: A state and regional examination of Mexico’s land tenure counter-reforms. Land Use Policy, 23, 136–146.

- Hannah, L., Midgley, G., Andelman, S., Araújo, M., Hughes, G., Martinez-Meyer, E., & Williams, P. (2007). Protected area needs in a changing climate. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 5, 131–138.

- Hansen, M.C., Potapov, P.V., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S.A., Tyukavina, A., & Townshend, J.R.G. (2013). High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science, 342, 850–853.

- Harley, J.B. (1989). Deconstructing the map. Cartographica, 6(2), 1–20.

- Hecht, S. (2008). The new rurality: Globalization, peasants and the paradoxes of landscapes. Desenvolvimento E Meio Ambiente [Development and environment], 17, 141–160.

- Hecht, S., Yang, A.L., Sijapati Basnett, B., Padoch, C., & Peluso, N. (2015). People in motion, forests in Transition: Trends in migration, urbanization, and remittances and their effects on tropical forests (Center for International Forestry Research Occasional Paper 142). Bogor Barat, Indonesia: CIFOR.

- Henderson, J.S. (1981). The world of the Ancient Maya. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Herlihy, P., & Knapp, G. (2003). Maps of, by, and for the peoples of Latin America. Human Organization, 62, 303–314.

- Herlihy, P., & Tappan, T. (2019). Recognizing indigenous Miskitu territory in Honduras. Geographical Review, 109(1), 67–86.

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). (2012). Mapa digital de México [Digital Map of Mexico]. Retrieved from gaia.inegi.org.mx

- Instituto Catastral del Estado de Campeche. (2010a). Cobertura de Educación: Primaria [Primary education coverage]. [map]. Retrieved from http://www.infocam.gob.mx/infocam/estadisticas.php

- Instituto Catastral del Estado de Campeche. (2010b). Distribución de Tenencia de Tierra [Land Tenure Distribution]. [map]. Retrieved from http://www.infocam.gob.mx/infocam/estadisticas.php

- Kelly, J. (2013). Village-Scale Practices and Water Sources in Indigenous Mexico after the Neoliberalizing of Social Property ( dissertation). Department of Geography, University of Kansas.

- Kelly, J., Herlihy, P., Tappan, T., Hilburn, A., & Fahrenbruch, M. (2017). From cognitive maps to transparent static web maps: Tools for indigenous territorial control in La Muskitia, Honduras. Cartographica, 52(1), 1–19.

- Kessler, F.C., & Slocum, T.A. (2019). The map’s changing role: A survey of the annals of the association of American geographers. In S. Brunn & R. Kehrein (Eds.), Handbook of the changing world language map (pp. 1–30). Cham: Springer.

- Keys, E., & Chowdhury, R.R. (2006). Cash crops, smallholder decision-making, and institutional interactions in a closing frontier: Calakmul, Campeche, Mexico. Journal of Latin American Geography, 5(2), 75–90.

- Kitamura, K., & Klapp, R.A. (2013). Common property protected areas: Community control in forest conservation. Land Use Policy, 34, 204–212.

- Levy Tacher, S.I., Aguirre Riviera, J.R., Vleut, I., Román Dañobeytia, F., Perales Rivera, H., Zúñiga Morales, J., & Macario Mendoza, P. (2016). Experiencias y perspectivas para la rehabilitación ecológica en zonas de amortiguamiento de las áreas naturales protegidas Montes Azules (Chiapas) y Calakmul (Campeche) [Experiences and perspectives for ecological restoration in buffer zones of the Montes Azules (Chiapas) and Calakmul (Campeche) protected areas]. In E. Ceccon & C. Martínez-Garza (Eds.), Experiencias Mexicanas en la Restauración de los Ecosistemas [Mexican Experiences in Ecosystem Restoration] (pp. 295–320). Cuernavaca: UNAM Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias.

- Lomnitz-Adler, C. (1992). Exits from the Labyrinth: Culture and ideology in the Mexican national space. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Martin, G.J., Camacho Benavides, C.I., Del Campo García, C.A., Anta Fonseca, S., Chapela Mendoza, F., & González Ortíz, M.A. (2011). Indigenous and community conserved areas in Oaxaca, Mexico. Management of Environmental Quality, 22(2), 250–266.

- Massey, A., Bhagwat, S., & Porodong, P. (2011). Beware the animals that dance: Conservation as an unintended outcome of cultural practices. Society, Biology, and Human Affairs, 7(2), 1–10.

- McAffee, K., & Shapiro, E. (2010). Payments for ecosystem services in Mexico: Nature, neoliberalism, social movements, and the state. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 100(3), 1–21.

- Méndez-López, M.E., García-Frapolli, E., Ruiz-Mallén, I., Porter-Bolland, L., & Reyes-Garcia, V. (2015). From paper to forest: Local motives for participation in different conservation initiatives. Case studies in southeastern Mexico. Environmental Management, 56, 695–709.

- Mexico News Daily. (2019, April 1). Big plans for the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, but does the isthmus want them? [online].

- Meyfroidt, P., Lambin, E.F., Erb, K., & Hertel, T.W. (2013). Globalization of land use: Distant drivers of land change and geographic displacement of land use. Current Opinions in Environmental Sustainability, 5, 438–444.

- Morett-Sánchez, J.C., & Cosío-Ruíz, C. (2017). Panorama de los ejidos y comunidades agrarias en México. Agricultura, Sociedad, y Desarrollo, 14, 1.

- Neumann, R.P. (2002). Imposing wilderness: Struggles over livelihood and nature preservation in Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Piper, K. (2002). Cartographic fictions: Maps, race, and identity. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Porter-Bolland, L., Drew, A.P., & Vergara-Tonorio, C. (2006). Analysis of a natural resources management system in the Calakmul biosphere reserve. Landscape and Urban Planning, 74(3–4), 223–241.

- Radel, C., Schmook, B., McEvoy, J., Méndez, C., & Petrzelka, P. (2012). Labour migration and gendered agricultural relations: The feminization of agriculture in the ejidal sector of Calakmul, Mexico. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12, 98–119.

- Ramírez-Delgado, J.P., Christman, Z., & Schmook, B. (2014). Deforestation and fragmentation of seasonal tropical forests in southern Yucatán, Mexico (1990–2006). Geocarto International, 29(8), 822–841.

- Ramírez-Reyes, C., Sims, K.R.E., Potapov, P., & Radeloff, V.C. (2018). Payments for ecosystem services in Mexico reduce forest fragmentation. Ecological Applications, 28(8), 1982–1997.

- Rankin, W. (2009). Cartography and the reality of boundaries. Perspecta, 42, 42–45.

- Ribot, J.C., & Peluso, N.L. (2003). A theory of access. Rural Sociology, 68(2), 153–181.

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, P., Levy Tacher, S.I., Ramírez-Marcial, N., & Estrada-Lugo, E. (2019). Análisis comparativo de la vegetación de fundo legal y la vegetación madura en el poblado de Yaxcabá, Yucatán, México [Comparative analysis of fundo legal vegetation and mature vegetation in the town of Yaxcaba, Yucatan, Mexico]. Botanical Sciences, 97(1), 50–64.

- Rodríguez-Solorzano, C. (2014). Unintended outcomes of farmers’ adaptation to climate variability: Deforestation and conservation in Calakmul and Maya biosphere reserves. Ecology and Society, 19(2), 53.

- Román-Dañobeytia, F.J., Levy-Tacher, S.I., Macario-Mendoza, P., & Zúñiga-Morales, J. (2014). Redefining secondary forests in the Mexican forest code: Implications for management, restoration, and conservation. Forests, 5, 978–991.

- Ruiz-Mallén, I., & Corbera, E. (2013). Community-based conservation and traditional ecological knowledge: Implications for social-ecological resilience. Ecology and Society, 18(4), 12.

- Ruiz-Mallén, I., Newing, H., Porter-Bolland, L., Pritchard, D., García-Frapolli, E., Méndez-López, M.E., … Reyes-García, V. (2014). Cognisance, participation, and protected areas in the Yucatan Peninsula. Environmental Conservation, 41(3), 265–275.

- Schultz, L., Duit, A., & Folke, C. (2011). Participation, adaptive co-management, and management performance in the world network of biosphere reserves. World Development, 39(4), 662–671.

- Schüren, U. (2003). Reconceptualizing the post-peasantry: Household strategies in Mexican ejidos. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 75, 47–63.

- Smith, D., Herlihy, P., Kelly, J., & Ramos Viera, A. (2009). The certification and privatization of indigenous lands in Mexico. Journal of Latin American Geography, 8(2), 175–208.

- Smyth, D. (2015). Indigenous protected areas and ICCAs: Commonalities, contrasts and confusions. Parks, 21(2), 73–84.

- Spiric, J. (2015). Uncovering REDD+ Readiness in Mexico: Actors, Discourses, and Benefit Sharing( PhD thesis). Programme in Environmental Science and Technology, ICTA, Barcelona, Spain.

- Tauli‑Corpuz, V. (2016). Report of the special rapporteur of the human rights council on the rights of indigenous peoples (A/71/150).

- Toledo, V.M. (2003). Los pueblos indígenas, actores estratégicos para el Corredor Biológico Mesoamericano [Indigenous peoples, strategic actors for the mesoamerican biological corridor]. Biodiversitas, 7(47), 8–14.

- Torres-Mazuera, G. (2014). Formas cotidianas de participación política rural: El Procede en Yucatán [Everyday forms of rural political participation: The procede program in Yucatan]. Estudios Sociológicos, 32(95), 295–321.

- Turner, B.L., Geoghegan, J., & Foster, D.R. (2004). Integrated land-change science and tropical deforestation in the Southern Yucatán: Final frontiers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vaccaro, I., Beltran, O., & Paquet, P.A. (2013). Political ecology and conservation policies: Some theoretical genealogies. Journal of Political Ecology, 20(1), 1. [online].

- Wainwright, J., & Bryan, J. (2009). Cartography. territory, property: Postcolonial reflections on indigenous counter-mapping in Nicaragua and Belize. Cultural Geographies, 16, 153–178.

- Wily, L.A., & Dewees, P.A. (2001). From users to custodians: Changing relations between people and the state in forest management in Tanzania (The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2569).