ABSTRACT

This article, through the use of political ecology perspectives on coercive conservation, aims to explain how in two separate Colombian Natural Parks and buffer zones, environmental policies designed to (re)take control of the frontier, have produced a similar territorial differentiation in the contention of illicit activities. Los Farallones in the Colombian Pacific and La Macarena/Puerto Rico in the Ariari region have experienced different stages of the armed conflict and are at the center of this analysis. I argue that in the contexts of both conflict escalation (1998–2007) and conflict de-escalation (2008–2016), the State in its attempt to control the frontier has not only had military intervention in areas of conservation but has also reinforced environmental programs that attack illegal mining and coca, producing both a territorially differentiated containment of illicit activities and an uneven progression of the illicit frontier.

Introduction

Land in Colombia has been the subject of important transformations since the early 2000s (Baquero, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Bejarano & Pizarro, Citation2005; Centro Nacional, de Memoria Histórica [CNMH], Citation2010a; Citation2015a; De Rementería, Citation2001; Fajardo, Citation2002, González, Citation1994; González et al. Citation2003). Successive governments have negotiated Peace Accords with the largest insurgent and counterinsurgent armies in confrontation with two partially demobilized illegal structures: The United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) in 2006 and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in 2016. A third negotiation is underway between the second largest guerrilla group, the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the government. These peace accords have had important impacts on the reconfiguration of the Colombian society, but changes have been particularly visible in the countryside (CNMH, Citation2010a, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Grajales, Citation2015, Citation2013, Citation2011).

Table 1. Coca distribution per jurisdictional regime in Colombia, 2001–2017.

Table 2. Machinery used to extract mineral in the area, 2016.

Table 3. Forced aerial and manual eradication of coca in the department of meta in hectares, 2001–2016.

Current conditions might reveal the intensity of those transformations in the extensive Colombian frontier. On the one hand, the approval of the Law 1726 of 2016 known as Ley de Zonas de Interés de Desarrollo Rural Económico y Social, among others, is propelling both large-scale land acquisition and legal grabbing in public vacant lands by Colombian companies, mainly in the Eastern Plains as an effort to promote agribusiness and biofuel clusters in former cocalero territories (Contraloría General de la Nación, Citation2013; Oxfam, Citation2013; Rodríguez, Citation2014; Lugo, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). On the other hand, different offices have revealed that Colombia is once again swimming in illicit crops, with more than 200,000 hectares of cultivated coca (UNODC Citation2017; El Colombiano, Citation2018; UNODC, Citation2018). This is the greatest peak since 2001 when the country recorded 170,000 hectares during the most lethal stage of the Colombian conflict. A significant percentage of the areas under coca cultivation are located in peasant, Afro-descendant, indigenous and National Natural Park territories (see ) where formal conservation programs have been difficult to implement.

Two points stand out in the overlapping of forces between increasing large-scale land acquisition and the boom of coca and illegal mining: The first being that the State has developed strong campaigns and alliances to access some of those frontiers through militarily supported environmental discourses. Secondly, a division between the frontiers where the State has gained some legitimacy and those where illicit economies and new criminal bands have revitalized, has increased.

Based on the previous categorization, in this article I intend to establish how militarily oriented environmental programs determine the mobility and uneven progression of illicit frontiers in Colombia. The questions that orient this research are: What are the military and environmental devices adopted by the State to increase its control over conservation areas that have experienced long-standing armed conflicts? How do a territorially differentiated presence and cooperation between environmental, military, and international institutions produce not only a mobility in the generation of illegal income but also an uneven progression of illicit frontiers inside conservation regimes?

The questions that orient this research are connected with two of the most sensitive aspects that this Special Issue on agrarian and extractive frontiers in Latin America addresses: on one side, this article approaches land use change and the dynamics around smuggling and traffic of drugs. While on the other, it analyzes the interdependence of law enforcement, violence, criminal networks and land use land cover (LULC) changes. To this end, I draw attention to diverse (neo)extra-activist mechanisms (the general aim of this SI) to usufruct land in special conservation regimes that have experienced intense armed confrontations.

To comply with the main goals of this article, I will contrast spatial information obtained from several public offices with reports from conservation and private institutions and a number of interviews from environmental offices and transnational organizations to analyze how the implementation of militarily oriented, environmental policies to re-control contested landscapes, meaning conservation regimes, has determined a mobility in the extraction of illicit income in Los Farallones NNP/buffer zones (Colombian Pacific) and Puerto Rico/La Macarena NNP (Ariari region). To display the respective contributions, this article has been divided into the following sections: a state-of-the-art of the literature on coercive conservation, a selection of the case studies, methodological considerations, background to violence in regimes of environmental conservation (in the Ariari region and Los Farallones), results, discussion (with a deep examination of militarily-oriented, environmental policies in light of political ecology perspectives), and final remarks.

New Frontiers and the role of coercive conservation in territorialization programs

Following Peluso and Lund (Citation2011), the conservations areas that have been approached in this article are categorized as New Frontiers of Land Control (NFLCs). According to the authors,

[T]hese created frontiers are not sites where ́development ́ and progress meet wilderness or traditional lands and peoples. They are sites where authorities, sovereignties, and hegemonies of the recent past have been or are currently being challenged by new enclosures, territorializations, and property regimes. What is new is not only land grabbing or ownership but also, new crops with new labor processes and objectives for the growers, new actors and subjects. As well as new legal and practical instruments for possessing, expropriating, or challenging previous land controls (2011: 5).

The (re)production of New Frontiers requires the presence of several elements:

Trans-regional companies along with State institutions are the new actors that redefine the boundaries of land control and access to natural resources in the periphery,

There must be new forms of territorialization, more interdependent and neoliberal in context (Moore, Citation2005; Brockington, Citation2009; West, Igoe, & Brockington, Citation2006);

Finally, these NFLCs require high levels of violence and corruption. There is violence of enclosure and primitive accumulation by forced appropriation as well as political violence and militarization projects in contested zones.

Los Farallones and Puerto Rico-La Macarena, the selected case studies, mirror many of the structural and socio-cultural transformations that have characterized New Frontiers for decades. They are comprised of towns with high levels of displacement, land abandonment, dispossession, and armed intimidation by outlaw groups in Colombia (DNP, Citation2014). Their history has been plagued with countless stories of how territorial control by armed actors, state programs to access the frontier, and illicit economies (under a broader transnational chain of organized crime), have defined them (Fajardo, Citation1989, Citation1994, Citation2002; CNMH, Citation2015a; Lugo, Citation2019a). Recently, they have experienced a territorially differentiated de-escalation of the armed conflict, which has resulted in new struggles for land and new mechanisms to accumulate it. Three successive peace negotiation processes between the largest outlaw groups and the governments in charge have redefined those frontiers. Therefore, I argue that the ways in which, the State, through a comprehensive securitized, environmental and post-conflict discourse, has interacted with third actors, has determined the differentiated trajectories of illicit containment in these frontiers.

I will highlight both coercive conservationFootnote1 and state re-territorializationFootnote2 in the context of peace negotiations to explain the implications that environmental policies and military campaigns to decrease the intensity of the conflict have had over the use of land. This should be understood in the context of Post-Accords politics and the new violence that has emerged due to the partial dismantling of the biggest illegal armies in Colombia. Peace negotiations and post-conflict military and environmental interventions not only work to provide background but are also key discourses and institutional devices behind campaigns intended to reinforce state control with a paradoxical readjustment of illegal markets and more focalized criminalities.

Concerning this, political ecologists have noted how processes of state-formation have been analyzed not only through the classical explanations of the concentration of violent means but also through renewed discourse of responsible environmental preservation (Peluso, Citation1993; Vandergeest & Peluso, Citation1995; Brockington, Igoe, and Neves, Citation2008; Castree, Citation2007; Brockington, Duffy, & Igoe, Citation2008, Igoe, Citation2004). The first approach has been at the center of the academic discussions for decades. The second however, has gained relevance by focusing on the emergence of networks of international funding, global media, environmental groups, and the scientific/research community to create an ideology of wise global resource management. As Peluso (Citation1993) notes, the State has often pursued a goal of military centralization but under the implementation of renewed coercive conservation programs. The State plays a twofold game: on the one hand, it accelerates systems of resource extraction under the platform of environmental conservation by conceding extensive portions of lands to companies, NGOs, and foreign states who look for the creation of new economic sectors such as forestry, ecotourism, and biofuel production (Ybarra, Citation2013; Woods, Citation2011). While on the other hand, it promotes strong campaigns of military intervention to recover the contested frontier (Brockington & Duffy, Citation2010). The discourse of conservation is effective to the extent that it adds followers and global attention to a fair cause of environmental preservation while guaranteeing both the conditions for global capital expansion (Corson, Citation2010) and a greater military access in territories where formal control has been limited (Bakker, Citation2005, Citation2009; Castree, Citation2008a, Citation2008b).

In Colombia, Asher and Ojeda (Citation2009), Ojeda (Citation2012), Bocarejo and Ojeda (Citation2015), and Devine. (Citation2017), among others, argue that the privatization of Natural Parks in Colombia has been facilitated by the green economy’s discourse regarding the need to protect paradisiacal natural spots. To the extent that the military in Colombia has guaranteed a path towards legality of former cocalero areas in the Caribbean Coast, environmental offices have then promoted privatized development as a ‘responsible’ option to employ minorities and former coca growers, moving them away from the illicit world. Some of the consequences of those paths of state conservation are violence, in the sense of displacement of ancestral groups and ethnic minorities, dispossession due to productive reconversion and the commodification of nature through either eco-tourist or green biofuel projects. As well as the imposition of new legal frameworks, orienting (and restricting) customary uses of land are some of the consequences of those paths of state conservation (Cárdenas, Citation2012; Devine., Citation2017; INDEPAZ, Citation2015; Ojeda, Citation2012; Oxfam, Citation2013).

In this article and through two different case studies, I argue that the way in which the State has advanced in the implementation of militaryFootnote3 and environmental programs to (re)take control of the frontier, has redefined not only paths of state re-territorialization but also the movement of illicit industries in New Frontiers. Although Los Farallones NNP and La Macarena NNP/Puerto Rico, belong to two different bio-ecological regions, they have been impacted by the influence of different armed actors and illicit economies in different times in history and have experienced different waves of settlement and peasant colonization. However, the implementation of major environmental policies, led initially by the Office of National Parks, have produced a similar outcome in both regions: a territorial differentiation. This is where state intervention has resulted in the containment of illicit production and a re-conversion of illicit productive activities toward legal commodities in some areas and a boom in the generation of illegal income (illegal mining and coca) in others.

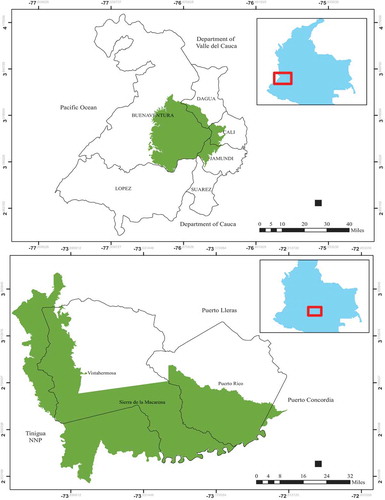

Map 1. Administrative division of the cases – Los Farallones & Puerto Rico.

Selection of case studies

These case studies are focused on areas of conservation in which differentiated trajectories in the contention of illicit activities have been traced as part of a state effort to gain control of the frontier. They belong to two different bio-ecological regions and are regulated through two different conservation regimes. The selection of the case studies (following a Direct Method of Agreement, in which two or more cases with a number of different conditions, have one common factor that explains the similar outcome; see George and Bennett, Citation2005; Van Heuveln, Citation2000) is based on the following criteria:

Los Farallones NNP belongs to the Pacific Basin in the department of Valle del Cauca. La Macarena NNP, belongs to La Macarena North Integrated Management District, which in turn is part of the Special Management Area of La Macarena. From the foothills of the Western Andes (Cordillera Occidental), Los Farallones leads towards the jungle and forests that comprise the Pacific basin. From the Andean-Amazonian foothills (Piedemonte Amazónico), La Macarena – Puerto Rico leads towards the savannahs of the Eastern Plains. Therefore, they represent two different transitional ecological systems.

Although, Los Farallones and La Macarena are National Natural Parks, they are regulated by different conservation regimes. Los Farallones, for example, belong to a major protected area called: The Regional Subsystem of Protected Areas in the Pacific, which includes NNPs, Wildlife Sanctuaries, Forestry Reserves, and several Afro-Colombian Community Councils. Adjacent to Los Farallones are the following Community Councils: Anchicayá, Agua Clara, Bellavista, Llano Bajo, Raposo, Mayorquín-Papayal, Cajambre, Yurumanguí, and El Playón. These entities were created to guarantee the protection and biological and socio-cultural reproduction of Afro-Colombian communities; however, they have major productive restrictions. Agriculture, mining, and fishing, among others, must comply with specific environmental requirements and production must be oriented towards family consumption and conservation (Los Farallones NNP, Citation2005; Citation2017 unpublished; Los Farallones – Barreto, Citation2013 unpublished). Puerto Rico/la Macarena, in turn, belongs to an area of conservation called La Macarena Special Management Area (AMEM, in Spanish). Special Management Areas, of which La Macarena is one of the largest in Colombia with more than 3.4 million hectares, are intended to restore ecological equilibriums in highly biodiverse regions (ANLA, Citation2017; La Macarena NNP, Citation2011, Citation2018; Sinchi, Citation2013). Four ecological and productive categories are part of the AMEM: 1) National Natural Parks, 2) Recovery Areas for Production; 3) Recovery Areas for Preservation, and 4) Areas for Production (Agroguejar, Citation2012; La Macarena NNP, Citation2018). Although, Los Farallones and La Macarena – Puerto Rico revolve around two National Natural Parks, they represent and are regulated by two different legal and environmental regimes.

Socio-spatially, La Macarena-Puerto Rico and Los Farallones are thought of as separate worlds but in fact, they are closely related. The reallocation of illicit production from one region to the other one; the mobilization of military forces from one National Park to the other, as well as the economic and infrastructural investments made by the State to connect both and secure a corridor from the Pacific to the Atlantic, have made the Pacific and the Ariari two highly connected socio-spatial constructions.

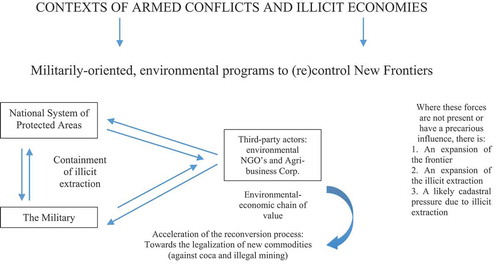

The State has been active in the promotion of coercive conservation policies in both regions through alliances with private and multilateral actors. In the Pacific, the initial alliance between the Office of National Natural Parks and the Military has allowed for the presence of conservation agencies to contain the expansion of illicit income and the frontier. In la Macarena NNP/Puerto Rico, joint efforts between the Office of National Parks and the Military have resulted in the arrival of biofuel companies that collaborate to promote green grabbing around alternative sources of energy. This tripartite framework, formed by the Office of National Parks, the Military & third-party actors linked to transnational chains of environmental value, is the analytical device that would explain the presence of a similar outcome, meaning a differentiated trajectory of illicit contention, in two New Frontiers of Land Control in Colombia. The hypothesis I will test in this document can be summarized as follows:

Diagram # 1

Methodological considerations

A multipronged research method was developed throughout this research. The main strategy, which is the estimation and analysis of spatial data, especially vector and grid data, include:

The visualization of coca crops per grid and year

The estimation of polygons showing areas of influence of unlicensed mechanized gold mining and palm production

The estimation of polygons based on accumulated anthropic changes between 2000 and 2016 for four scenarios previously estimated by the Office of National Natural Parks – Los Farallones: 1) Polygons of forest recovery, in which recovery of forest cover between 2000 and 2016 was reported through the processing of aerial imagery by the Office of National Natural Parks. 2) Polygons of forest loss, in which loss in forest cover was reported between 2002 and 2016 by the same institution. 3) Polygons of constant pressure, in which permanent loss of forest cover (no significant change over time) has been reported in areas of human settlement from 2000–2016. Permanent loss of forest cover has been associated with regular agriculture, cattle ranching, fishing, and other daily activities by groups who settled and colonized the area before 2002 and have lived there since then. Finally, 4) areas with no anthropic change, in which changes in forest cover either are not present or are so small that they are undetectable using satellite and aerial imagery.

Spatial data analysis and visualization of information provided by State and multilateral offices such as the Office of National Natural Parks, the Integrated Illicit Crops Monitoring System and ELEMENTA, among others, were complemented with content analysis to trace major productive changes, associated with the presence or absence of coca, illegal mining, and palm. Content analysis was developed using reports provided by some of the above-mentioned institutions and by social organizations that are present in the regions of study. Several official documents that belong to the analyzed corpus have an unpublished character and I was granted access to them only for the development of this project. Anonymity about who wrote these documents has been preserved and for the documents that have an unpublished character, they have been specified in the main text and the references as unpublished.

Finally, a small set of interviews has been developed to contextualize and interpret the information provided in the above-mentioned sources. Two types of respondents have been interviewed: official representatives from environmental and social state agencies that work in the areas of analysis and represent different levels in the corporate chain of command. Also, social leaders – especially in Puerto Rico – have been interviewed to understand how the processes of productive segmentation and unevenly progression (containment) of the illicit frontier have affected the communities. Given the sensitivity of the topics discussed in this article, anonymity has been guaranteed for all the respondents, although basic information in the sense of professional and gender descriptors have been included to identify them. The collection and processing of the data has been developed by the present author.

Background to violence in environmental regimes

Socio-political conditions in the Pacific

Los Farallones belongs to a region known as the Pacific, made up of the coastal districts of four departments: Chocó, Cauca, Nariño, and Valle. It is one of the poorest and most convulsive regions in Colombia due to its social isolation, economic exclusion, political contestation, and racial segregation. Since the political reforms of the late 1980s that ended up in the Constitution of 1991, the Pacific has become a hub for environmental and cultural conservation. Six of the largest National Natural Parks in Colombia have their boundaries inside the Pacific and almost 80% of the Afro-descent population living in Community Councils (an entity created to protect Afro-Colombian communities) are located there. Conservation through environmental and socio-cultural preservation has made the Pacific an interesting case of land re-orientation; putting thousands of hectares of land out of the private market.

Territorial Zoning, which was created as a government policy to administer natural resources and relocate vulnerable populations (Asher & Ojeda, Citation2009) has made this region a zone with several restrictions in terms of economic and infrastructure investments. This emphasis has resulted in low levels of economic development. Additionally, Afro-descendant and mestizo communities, with the latter being the main group of inhabitants of Los Farallones, have experienced significant levels of segregation due to their historical, economic and racial exclusion as well as an absence of formal institutions. Productive restrictions that a conservation regime might cause, by limiting the economic options available for a peasant family, superimposed on deficient basic social and physical infrastructure, have kept the standard of living of mestizo and peasant communities low.

Politically, the history of these lands has been anything but a bed of roses. As has happened with the expansion of the frontier throughout Colombia, lands inside and around the Park have witnessed armed, economic, and socio-cultural contestation. The FARC’s Front 30th and Manuel Cepeda Vargas since 1980s, the AUC’s Calima Block during the 2000s, and more recently the ‘third and fourth stages’ of the narcotrafficking chain represented by the Norte del Valle Cartel and more atomized post-AUC groups under the lead of La Empresa (criminal band), Henry Loaiza, Diego León Montoya (alias don Diego), Luis Fernando Gómez (alias Rasguño), and Arcángel de Jesús Henao (alias don Mocho), among others, have been the most prominent actors, fighting for territorial control of the region especially of Buenaventura and Calima (CNMH, 2015). Some of the most violent episodes of the armed conflict have occurred there, among them: the collective kidnappings of ‘La María’ (180 people kidnapped; El País, Citation2014; El Tiempo, Citation2019a) and ‘the Kilometer 18th’ (70 people kidnapped; El País, Citation2010) as well as the massacre of Naya by paramilitary forces (CNMH, Citation2015a), in which, more than 120 locals were assassinated in 2001 (El Espectador, Citation2009).

Political turmoil in the area, however, must be interpreted with an understanding of armed contestation, in which different groups have tried to secure a hegemonic position around the routes for drug trafficking (Ballvé, Citation2012; Grajales, Citation2013). The strategic position of Los Farallones as a corridor that stretches from the third largest Colombian city, Cali, to the main port over the Pacific, Buenaventura, has led to the creation of a blurred corridor characterized by illicit activities, armed control, corruption, and multidimensional poverty. Systematically, armed actors especially AUC and post-AUC militias, have proffered distinct forms of intimidation, a situation that was at a peak between 2000 and 2004 when, at least, 15 massacres were reported in Buenaventura, Los Farallones, and surrounding districts. Owing to this, this corridor was one of the areas most affected by the conflict. In 2014, NCR and ACNUR reported in the census that, up until that year, of the 392,054 inhabitants of Buenaventura, 187,542 were victims of the conflict and 42% of the total population had experienced some form of displacement (NCR & ACNUR, Citation2014).

Socio-political conditions in the Ariari

In the case of Puerto Rico, this town belongs to La Macarena Special Management Area (AMEM – department of Meta). Legally, a Special Management Area is intended to regulate the exploitation and use of renewable natural resources in highly biodiverse regions. The Central Government created this Special Area in 1989 and two departments (Meta and Guaviare), 19 municipalities, 589 districts, and 15 Indigenous Reservoirs currently make it up (La Macarena NNP, Citation2011, Citation2018; Sinchi, Citation2013).

Politically, its history has been marked by the evolution of an armed conflict, as it was the center of the failed Caguán peace process during the late 1990s. In 1999, former president Andrés Pastrana (1998–2002) established a demilitarized zone for the development of the peace negotiations with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) through the Resolution 85 of October 14th of 1998. The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) included the municipalities of La Uribe, La Macarena, Mesetas, and Vistahermosa in the department of Meta and San Vicente del Caguán in the department of Caquetá. The history of the AMEM and especially of La Macarena North Integrated Management District (where Puerto Rico belongs), has been a synthesis of the different political conflicts this country has experienced during its long civil war.

The FARC’s excesses in the DMZ with hostages brutally deprived from freedom for political and economic reasons (El Tiempo, Citation2019a), the boom in coca crops during the 1990s and 2000s (UNODC, Citation2018), as well as the intense military and paramilitary re-control after the failure of the Caguán Peace Talks in 2002 (this aspect was consistently discussed by a number of interviewed respondents during fieldwork), illustrate the political turmoil this region has witnessed in recent times.

The Ariari represents a transitional zone from the Amazonian foothills to the Eastern Plains. Socio-spatially, the existence of different productive systems due to consecutive booms in marihuana, oil, cattle, coca, and more recently in palm, has turned this region into a laboratory, in which licit and illegal income have historically overlapped. Whether the chains of economic production are integrated into peasant or agribusiness systems, Puerto Rico has been constructed as an extractive frontier amid a strong armed conflict. Its condition as a periphery with regard to national (Bogotá) and regional (Villavicencio) centers of power with both open valves for anthropic transformation in La Macarena National Natural Park (NNP) and closed frontiers in the north, reflects its character as an extractive region, with high levels of multidimensional poverty, marginal access to public services, and a high rate in the incidence of armed conflict into daily activities (ELEMENTA, Citation2018).

Results

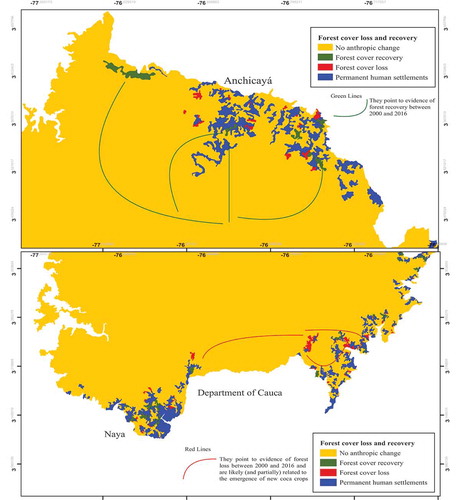

Results presented for the cases of 1) Los Farallones NNP and buffer zones (Map # 1) and 2) La Macarena NNP/Puerto Rico and buffer zones (Map # 2), show loss of forest cover during the early 2000s. Based on the visual estimations, the concentration of activities of illicit extraction is visible for the case of coca in the northwest, north, center, and southwest of La Macarena NNP/Puerto Rico.

In the case of Los Farallones, since the early 2000s, the expansion of the productive licit and illicit frontier has spread toward increasingly inaccessible areas inside the Park. In map # 4A, some of the blue (constant pressure since 2000) and green polygons (forest recovery until 2016) reflect how the coca frontier advanced toward the north and south of the park. This loss of forest cover goes against the environmental and legal regulations of a Natural Park. Although, in Colombia legislation around the System of National Natural Parks has advanced from a static position (following a Yosemite approach to preserve crystalline environments) to a more conciliatory vision of National Parks with people, restrictions are still important, and look for the prohibition of any land use.

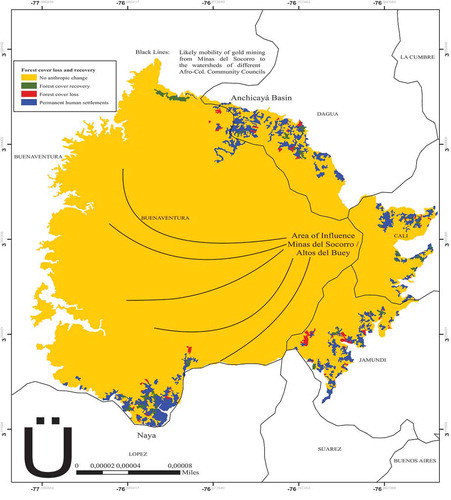

In this vein, the presence of coca inside the Park was a delicate matter for the Office of National Parks. Its cultivation, however, was not the most urgent issue. During the mid-2000s, the out of control increase of unlicensed mechanized extraction of gold was the main socio-environmental concern for the public opinion, including representatives from Los Farallones NNP (El País, Citation2015). Between 2010 and 2015, different points of extraction in the sense of underground tunnels and galleries had been identified inside the Park, especially in the area known as Minas del Socorro-Altos del Buey. The above was affecting not only newly-deforested areas due to the penetration of mountains () and rivers for gold extraction, but especially the system of watersheds that pour water to the third largest metropolitan area in Colombia: Cali-Buenaventura-Jamundí-Dagua.

Before 2012, the regional NNP office, although in charge of this area, was certainly incapable of stopping the advance of the frontier and illegal economies. According to official representatives from Los Farallones NNP OfficeFootnote4 and localsFootnote5 who live in the area of influence of Minas del Socorro, previous Chiefs of Protected Areas, under a more conciliatory discourse, were not able to deter locals from getting involved in these activities. The situation changed with the advent of new institutional orientations, based on the imposition of specific environmental rules to stop the contamination of water sources around Minas del Socorro and greater economic resources since 2012.

Map # 2. Forest cover loss and recovery in Los Farallones NNP, 2000-2016

Source: Own spatial and visual estimations (using vector data) based on information provided by the System of National Natural Parks – Pacific Regional Office. The information visualized in this article has been collected and processed with the support of the Office of National Natural Parks. Through, Radicado OFI17-31,405-DCP-2005, Radicado EXTMI17-33,971 and Radicado 2,017,766,000,931, permission was granted to access and use data from The Office of National Natural Parks – Los Farallones only for research purposes and for the output that will result from my research projects.

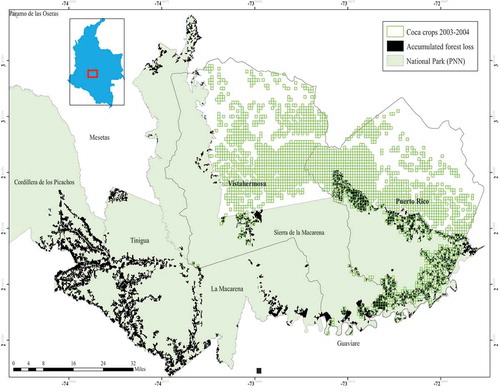

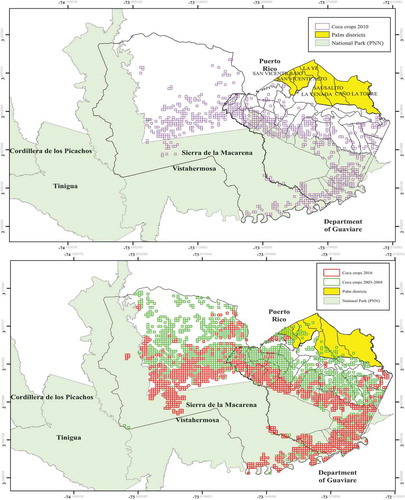

Map # 3. Illicit landscape in Puerto Rico Coca crops (grids), 2003 & 2004

Source: Own spatial and visual estimations (using grid and vector data) based on information provided by the System of National Natural Parks (https://mapas.parquesnacionales.gov.co/), ELEMENTA (Human Rights Consulting) – Usos, Impactos y Derechos: Posibilidades Políticas y Jurídicas para la Investigación de la Hoja de Coca en Colombia, in: https://www.elementa.co/capitulo-5usos-impactos-y-derechos-posibilidades-politicas-y-juridicas-para-la-investigacion-de-la-hoja-de-coca-en-colombia/, 2018, and the Integrated Illicit Crops Monitoring System.

As for the case of Puerto Rico/La Macarena NNP, since the mid-1990s, coca spread around a significant portion of the Park except for the most inaccessible forest and jungles that lead towards the Amazon. Evidence of deforestation in this and near National Parks such as Tinigua (black polygons Map # 3) are associated not only to the cultivation of coca but also to other productive activities that are seen as coca-byproducts such as pastures and cattle ranching (Tinigua NNP, Citation2015 unpublished). Thus, the presence of coca and the fact that La Macarena NNP and surrounding municipalities served as one of the most important retreats for insurgencies during the failed Caguán Peace Process and DMZ, defined the environmental interventions developed in this region years later. In the next pages, an interpretation of the results, case by case, will be presented

Case # 1: Los Farallones and its renewed conservation policy

Map # 4. (a) Forest cover loss and recovery in the Anchicaya Basin (north of the Park), 2000-2016. (b) Forest cover loss and recovery in the Naya Basin (south of the Park), 2000-2016

Source: Own spatial and visual estimations (using vector data) based on information provided by the System of National Natural Parks – Pacific Regional Office

The first step in the above-mentioned ladder of environmental preservation is the alliance between the new regional office in Los Farallones and the military to destroy any source of gold extraction and install fixed checkpoints to stop the flow of coca and minerals. Once this condition has been covered, the NNP has looked for the gradual collaboration with eco-tourist programs, the media, conservation agencies and research institutes to attack frontally the legitimacy of miners and coca growers. The installment of a few mobile forces, the implementation of a judiciary scheme to prosecute people involved in illicit activities (El País, Citation2015, Citation2018; El Tiempo, Citation2019b) and the development of a program of voluntary eradication of coca, which gave life to the first National Program for the Substitution of Illicit Crops in the region, partially decreased both gold extraction in Minas del Socorro and coca cultivation in Anchicayá as controls in show. However, illicit activities never disappeared. As the Maps # 4A and 4B show, constant settlement (no expansion of the frontier) and environmental recovery is visible in both Cali and Dagua while in Jamundí and Naya, anthropic transformation in the sense of forest loss cover has increased. This loss of forest cover is likely associated to the presence of new coca crops and new corridors for drug trafficking, among others.

Since 2012, Los Farallones has designed a set of institutional devices and strategies to implement an aggressive program of conservation – using military and other institutional means – to contain illicit extraction of coca and gold mining (Los Farallones, 2015 unpublished). Three are the cornerstones of this program: 1) The Values Subject of Conservation (or the VSC) strategy, which looks for a careful aerial, terrestrial, and satellite estimation of regions inside the Park that need to be preserved; 2) the Use, Occupation, and Land Tenancy (or the UOT) strategy, which looks for a detailed examination of the legal status of the occupants (and their properties) inside the park and the assessment of solutions that will contribute to stop the expansion of the frontier; 3) and a Policy of Participative Ecological Restoration, which is intended to increase forest cover in areas previously affected by human intervention.

Under the Policy of Participative Ecological Restoration, the Office of National Parks has promoted key coalitions with the following actors: High Mountain Battalion # 3 Rodrigo Lloreda, Battalion of Engineers Agustín Codazzi, Military Health Units, the Attorney General Office, the Technical Investigation Corps of the Attorney General’s Office, and the Criminal Investigation Department, among others. These alliances between different military offices and the new leadership in Los Farallones to restore the environmental and institutional control in this frontier and stop the contamination of water sources due to the illegal extraction of gold has gone hand in hand with the intervention of other environmental agencies. That is the case of the WWFFootnote6, an international NGO that has worked in the promotion and assessment of ecological restoration inside the Park and the National Program for the Substitution of Illicit Crops (PNIS, in Spanish), which has been a program designed to contain coca crops, initially in the region of Anchicayá.

Productive reconversion from coca and illegal mining towards eco-tourism and substitution of illicit crops under the rule of Los Farallones NNP has worked in containing certain forms of illegal extraction while it has allowed the insertion of some micro local economies into ecotourist (transnational) dynamics of hiking, bird sighting, and ranger familiesFootnote7. A military re-control of areas of conservation as a preliminary step to develop new forms of economic wealth (Bocarejo & Ojeda, Citation2015; Devine & Ojeda, Citation2017; Devine., Citation2017; Ojeda, Citation2012) is visible in the Park especially under the rubric of ecotourist practices near Minas del Socorro and Anchicayá. However, this generation of wealth seems marginal when compared to cases of environmental-military intervention in other NPPs such as Caño Cristales/La Macarena and Sierra Nevada, where levels of privatization of natural resources have been greater, and in some way, scandalous (El Espectador, Citation2009). Thus, coercive conservation (Peluso, Citation1993) in Colombia operates relatively well in areas where the alliance between the Office of National Parks, the Military & third-party actors linked to transnational chains of environmental value has been guaranteed.

As a result, since 2012, a spatially differentiated trajectory of illicit contention led by environmental offices, has produced three outcomes:

A containment path that has reduced the speed of both the expansion of the frontier and illicit extraction. The focus of this partially successful intervention has been on Altos del Buey/Minas del Socorro to stop illegal mining, and the Anchicayá Basin to transform coca cultivations into reforested areas and small-scale ‘legal’ crops (based on principles of family and environmentally sustainable agriculture).

An expansion of the frontier and a reallocation of illegal income, especially from coca, toward the Jamundí and Naya watersheds (red polygons and red zigzag arrows Map # 4B)Footnote8. This mobility of illegal crops is due not only to environmental and military interventions in Minas del Socorro and Anchicayá, which has meant a redeployment of illegal forces out of State radar but also to a productive readjustment amid a boom in the transnational chain of cocaine. Environmental and military interventions across the park and surrounding jurisdictions have been insufficient to control a predatory system in which more coca plantations have grown in the districts of Naya and Jamundí. In Anchicayá, the expansion of the coca frontier has been controlled and some communities are working under the supervision and pressure of the National Program for the Substitution of Illicit Crops (PNIS) to get incentives in eco-tourism, reforestation, silvo-pastoral projects, and agricultural programs. In turn, in Naya and the corridors that lead toward the foothills in Jamundí, the situation is critical not only in terms of the spread of coca but also in regards to the presence of new criminal actors as has been denounced in several occasions (El Pais, Citation2018, El Tiempo, 2019, El Espectador, Citation2009).

As part of this campaign by environmental entities in charge of Los Farallones to stop illegal mining in Minas del Socorro, backhoe gold extraction has grown exponentially in some of the watersheds that connect Buenaventura with the park (zigzag black arrows in Map # 2). That means that, although Los Farallones NNP has embarked on a program to partially stop backhoe loaders in Minas del Socorro, it has not been able to control a number of forces that now work around the watersheds that connect the park with the Raposo, Cajambre, Mayorquín, and Yurumanguí riversFootnote9. Strategically, gold mining in these watersheds has been established outside the limits of the park to avoid further controls from conservation agencies. According to information provided by the SINAP office in 2016 (see ), the following machinery has been reported or confiscated in the watersheds that collide with the western limits of Los Farallones NNP:

Between 2012 and 2015, during the climax of gold extraction () in Minas del Socorro, ecological affectations showed the following signals:

Figure 2. Camps for gold extraction and deforestation due to penetration of mining activities; Source: PNN Office, 2016.

However, systemic interventions by environmental and military offices, as well as a zero-tolerance policy against gold extraction in the area has led, to a partial reallocation of backhoe mining, this time around the watersheds that collide with the western limits of Los Farallones NNP.

Case # 2: Puerto Rico and La Macarena NNP

The construction of Puerto Rico (Ariari) as a New Frontier of differentiated illicit contention will be compared with the case of Los Farallones. In Puerto Rico’s case, there has been a readjustment in the spatialization of illicit crops although the diffusion of an environmental discourse has opened the door for increases in land grabbing and the progression of a new palm sector (following trajectories of land grabbing and promotion of flex crops such as the ones described by Borras, Franco, Kay, and Spoor, Citation2011 and by Borras, Hall, Scoones, White, & Wolford, Citation2011).

The Colombia verde operation and (again) the institutional discourse against coca

In Puerto Rico and La Macarena NNP, the relationships between the Military and the Office of National Parks have not been as pleasant as they have been in Los Farallones. In the former, any sort of active cooperation between these two institutions has been preceded by one of the most controversial programs to preserve a highly biodiverse region: The Colombia Verde Operation. This operation executed by the Presidential Program Against Illegal Crops between 2005 and 2006 was designed to eradicate 4,598 hectares of coca inside La Macarena NNP manually and by air. Until that time, the Colombia Verde Operation had been the only attempt executed by any state office in Colombia to eradicate coca crops using aerial spray of glyphosate. Thus, during the manual eradication process that lasted 200 days in 2005 and 2006, 2,909 hectares of coca were destroyed. However, during the 5-day period of aerial spraying in 2006, 1,769 hectares of coca, were eradicated (Lugo, Citation2019a).

This eradication process – opposed by the Office of National Parks at different levels – reflected an increasingly military influence in areas of conservation. In the AMEM, strategies to guarantee the (re)control of regions with coca planting and under the influence of different guerrilla fronts, such as Tinigua and La Macarena NNPs, were preceded by the creation of the Joint Task Forces Omega and AresFootnote10.

In 2003 and 2004 as the Map # 2 shows (see also green grids in Map # 5B), the majority of the private cadastral lands in Puerto Rico were cultivated with coca. A great portion of the northern sides of Vistahermosa and Puerto Rico and an important section of La Macarena NNP, in which the development of any type of human activity is prohibited, had at least, 0.1 hectares of coca.

Initially, aerial eradication was the main strategy to stop the spread of coca. As the shows, forced aerial and manual eradication have been two of the selected options to destroy coca plants regardless the impact that these strategies will have on the livelihoods and health of families in these territories.

Map # 5. (a). Productive reconversion in Puerto Rico Coca Crops vs. Oil Palm, 2010. (b). Accumulated productive reconversion in Puerto Rico Coca Crops vs. Oil Palm, 2003-2016

However, since Operation Colombia Verde, La Macarena NNP Office was able to advance in the implementation of a program called ‘Eradication of Illicit Crops inside National Natural Parks and Zones with a Buffer Function’ (Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia - Dirección Territorial Orinoquía, Citation2015) in the early 2010s for several reasons. Those being, the evolution of forced eradication, a regular decrease in violent actions since 2007, and the devising of selective programs to create a more inclusive and participatory scenario with communities who were subject to eradication initiatives.

In 2010, the lowest peak in the cultivation of illicit crops was reached. From 7,040 hectares cultivated in 2005, Puerto Rico recorded a sustained decrease until getting 757 hectares in 2010. Maps #3 and # 5A expose the retreat of coca during this process of voluntary and forced eradication guided by the Office of La Macarena NNP and the Omega Joint Task Force, among others. Map # 2 shows areas with more than 0.1 hectares of coca (green grids) in Puerto Rico, while Map # 5A provides a visual representation of the same crops in 2010, doing visible the effectiveness of the eradication process especially in the north and east of the municipality.

Thus, between 2006 and 2010, three major programs were implemented to attack coca crops in the area: the first being The Colombia Verde Operation from 2005–2006 (Gónzalez Plazas, Citation2007; Ruiz, Citation2006). The second one was the Eradication of illicit crops inside National Natural Parks and buffer zones, 2010–2014 (La Macarena, 2014 unpublished), and the third one, the regulation and legalization of land tenure in adjacent sectors to La Macarena NNP in the municipality of Puerto Rico, 2007–2011, which was oriented especially by La Macarena NNP Office (La Macarena NNP., Citation2011). This last program became a strategy to accelerate the titling of 825 properties (former public vacant lands) for an equal number of families, and to press for the successful eradication of coca crops in these new titled lands (Agroguejar, Citation2012; La Macarena, Citation2011). By law, former public vacant lands must be cleared from any trace of illicit extraction and potential property owners must certify that they do not participate in these activities during the following years in order to preserve their titles. The community that has benefited from this collective effort is The Peasant Association for Organic Agriculture and Fair Trade in the Güejar River Basin (AGROGUEJAR), a group of peasants whose families have settled Puerto Toledo and La Macarena’s public vacant lands for decades (Agroguejar, Citation2012; La Macarena NNP., Citation2011).

While the west experienced this titling effort to reduce the level of illicit extraction in both the Güejar River Basin and adjacent districts of La Macarena NNP, in the north and east of Puerto Rico (where coca cultivation also disappeared between 2006 and 2010) a renewed process of green grabbing started during the same period. Looking at Map 5B, former green grids (coca regions in 2003) have disappeared in the north and northeast to give way to a new palm corridor that has expanded across 35,000 hectares, previously controlled by the FARC. The districts that have been subject of this gradual reconversion are marked as yellow polygons in Map 5AFootnote11.

Before 2006 there was no record of palm plantations in these districts. However, in 2016, around 35,000 hectares of palm (figure provided by members of the Municipal Council) have replaced previous coca plantations in a transition that has been led by a few corporations. This has resulted in new waves of land grabbing and a territorial enclosure as several leaders from the region have noted (Lugo, Citation2019a)Footnote12.

Globally, la Macarena NNP Office, the Unit for Agricultural Rural Planning, the National Program for Voluntary Substitution of Illicit Crops, the National Roads Institute in charge of the Granada – El Guaviare HighwayFootnote13, among others, have led a program to reorient the economic activities in the region. These institutions have worked alongside a number of private investors of which InduAriari and Aceites Cimarrones are some of the most renowned brands. The above has crystalized an anti-insurgent vision of development that has allowed the progressive modernization of local agriculture far from the obscured past of the ‘easy-money & cocalero culture’. In this vein, Puerto Rico/La Macarena has experienced a process of peasant parceling and land redistribution in the west and a trajectory of resource grabbing in the east. In both cases, a joint effort by environmental and military offices to contain coca cultivation has led to the arrival of a third actor: The agency in charge of the National Integral Plan for Coca Substitution in the west and Colombian-based agribusiness conglomerates in the east. However, coca has hardly disappeared. Instead, it has moved to the south, towards more inaccessible areas in La Macarena NNP.

Discussion

This research points out to some forms of environmental intervention that are related to a territorially differentiated re-control of the State. As previous literature shows – not only for the Colombian case–, in highly contested conservation areas under increasing state pressure, there is an environmental apparatus that collides with progressive military campaigns, producing new controls and accesses to important natural resources (Brockington & Igoe, Citation2006; Brockington, Igoe, and Neves, Citation2008; Brockington & Duffy, Citation2010; Brockington & Scholfield, Citation2010; Duffy, Citation2005; Kramer and Woods, Citation2012; Woods, Citation2011). However, this new control is highly selective.

In Los Farallones, since the late 2000s, militarily-oriented environmental intervention has produced differentiated outcomes in terms of the expansion of the frontier and trajectories of forest recovery. In areas where the military and environmental agencies have joined efforts and have been able to control the cultivation of coca and unlicensed mechanized extraction of gold, frontier expansion has lessened and land use has been reoriented to ecological restoration. Also, third actors, especially environmental NGOs and national programs for coca voluntary substitution, have accelerated that transition. A stronger environmental policy has not only made clear that inside the Park there is no space for accumulation but has also promoted property fragmentation (with no option to expand the frontier). This has been visible around the watersheds of Cali and Anchicayá. But where one of those (or both) institutional forces fail, increases in the frontier and illicit activities are more likely. This is particularly true for the watersheds of Jamundí-Timba, Naya, and some of the Community Councils adjacent to the western limits of the Park. And in the middle of these transformations, there exist economically segregated groups, under pressure from both environmental policies that do not shed lights into alternative ways of earning ‘legal income’ (except for some ecotourism projects) and criminal bands that now control new territories and more powerful sources to extract gold and coca. Jamundí and Naya seem to be good examples of it.

Although, there is literature that describes how coercive conservation produces unintended consequences, an important part of this literature points out to the classical Harvey’s notion of accumulation by dispossession and the violent process of wealth generation (Bocarejo & Ojeda, Citation2015; Devine & Ojeda, Citation2017). In this vein, the militarization of the conservation process (Peluso, Citation1993; Vandergeest & Peluso, Citation1995; Ybarra, Citation2013; Woods, Citation2011) has promoted both a securitized vision of development and stronger connections between conservation regimes and transnational chains of environmental value (Devine & Ojeda, Citation2017; Ojeda, Citation2012). While these ideas are relevant, they overlook the segregation and socio-productive segmentation gradually developed as a result of the differentiated institutional treatment that the State and other formal actors have established in New Frontiers. This article through the analysis of state’s re-control of the frontier, shows how a newly emerged illicit frontier has been unevenly altered.

In this vein, new forms of land control – central in this Special Issue – arise: On one side, military and environmental burdens have taken off in areas where state pressure has stopped the advance of illicit activities. While on the other, novel forms of illicit extraction operate in farther areas in Los Farallones, now under the control of revitalized criminal bands.

In Puerto Rico – La Macarena, state efforts to reduce coca in the west while promoting green grabbing with no risks of deforestation in the north and east, have re-territorialized the landscape and transformed the distribution of land and its associated uses. Peasant titling, an enclosure of the titled Peasant Reserve Güejar-Cafre in the west and a re-introduction of coca cultivations inside the Park since 2015 in the south, contrast radically with the advance of land grabbing and the emergence of a palm economy, fenced for social and security reasons in the east. Segmentation and socio-productive segregation seems to be more visible in this last case, although the tripartite analytical framework proposed in previous sections operates in a similar fashion. At the end, coca has moved toward the south and has gained so much power that state and formal institutions, including the military, are currently incapable of controlling and even accessing the south of Puerto Rico/La Macarena NNP.

These findings on the re-adjustment of the illicit income supports contributions from political ecologists in which the mobility of illicit extraction accelerates in contexts of peace negotiations (Kramer and Woods, Citation2012). In these scenarios, previously contested regions have no longer the influence of traditional illegal actors, so the State faces more atomized violences, while trying to impose new environmental regulations in recently controlled areas. The paradoxical outcome of this selective presence is the movement of the illicit frontier.

Final remarks

As discussed throughout the article, coercive conservation has been a strategy deployed with regularity by the Colombian State to access New Frontiers of Land Control. As part of these NFLCs, conservation regimes have been key scenarios where not only the internal conflict has been fought, but also where a number formal and illegal actors have tried to secure a privileged access to different natural resources. In contexts of a territorially differentiated de-escalation of the conflict, a tripartite framework formed by the Office of National Parks – the Military – & third actors linked to transnational chains of environmental value, has been proposed as the analytical axis that explains how certain forms of state re-control operate. In areas where environmental and military state agencies have successfully collided, a containment in the generation of illegal income, especially from coca and illegal mining, has been accomplished. Once illicit containment has been partially stabilized, reconversion and substitution towards licit commodities is accelerated by the entrance of third actors, usually associated to transnational chains of environmental value. In areas where one of the original institutional forces (environmental offices or the Military) are absent, the frontier and income associated with the extraction of coca and illegal mining have expanded.

This article expands two topics that have been prioritized in this Special Issue: first, land use change and the dynamics around traffic of drugs, and second, the interdependence of law enforcement, violence, criminal networks and land use land cover (LULC) changes. As for the dynamics around smuggling and traffic of drugs, this article analyzes the movement of the illicit frontier as a response to some state initiatives and under increasing transnational chains of illicit extraction. In regards to the connection between law enforcement, illicit networks and land use land cover (LULC) changes, this article shows not only the differentiated functioning of coercive conservation strategies, especially the ones that link the Office of National Parks with the Military, but also the unbalanced results that such alliances produce. Thus, law and environmental enforcement shapes an unevenly progression of the illicit landscape in Colombia.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Julio Arias, attendees of the Annual Congress of the American Association of Geographers (AAG) - Boston 2017 who made observations to a preliminary version of this manuscript and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback. All remaining errors are my own

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Following Peluso (Citation1993), coercive conservation refers to state efforts to control valuable natural resources resorting to the militarization of the conservation process.

2. This research is based on Peluso and Vandergeest’s definition of state territorialization as: ‘an attempt by an individual or group to affect, influence, or control people, phenomena, and relationships by delimiting and asserting control over a geographic area. Territorialization is about excluding or including people within particular geographic boundaries, and about controlling what people do and their access to natural resources within those boundaries.’ (Peluso and Vandergeest, 1995: 387–389).

3. During the 1970s – 1990s military spending in Colombia moved between 2% and 3.1% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Since the late 1990s, due to the implementation of the first stage of Plan Colombia, military spending has grown to over 3.9% of the GDP. Additionally, between 2002 and 2017, the share of military spending in the National General Budget grew from 15% to 18%. (Llanes, Citation2017; Ministry of Defense, Citation2009).

4. Interview # 10 to a male representative from the Office of Natural Parks who has been working in activities of control inside the Park.

5. Interview # 14 to a male leader who knows both the process of extraction at Minas del Socorro and important institutional changes at Los Farallones.

6. Interview # 10 to a male representative from the Office of Natural Parks who has been working in activities of control inside the Park.

7. Interview # 12 to a male representative from the Office of Natural Parks who has been working in activities of control inside the Park.

8. Interview # 12 to a male representative from the Office of Natural Parks who has been working in activities of control inside the Park – Interview # 11 to a female representative from the Office of Natural Parks who has been working in control and administrative inside the Park.

9. Interview # 11 to a female representative from the Office of Natural Parks who has been working in control and administrative inside the Park.

10. Interview # 20 to a male representative from the Office of Natural Parks in Tinigua (and adjacent NNP to la Macarena) who worked in activities of control inside the Park. He is not working anymore in that Park.

11. Data provided by the National Federation of Palm Cultivators (Fedepalma, in Spanish) does not include a significant portion of the real cultivated area, so the estimation used in this article relies upon the districts (or corregimientos) in which new palm plantations have grown.

12. Interview # 22 to a group of leaders (3) from Agroguejar who have worked in several social, health, education, and productive programs. They have also participated in the titling processes in the Reserve of Guejar-Cafre and more recently in programs related to the incorporation of former FARC combatants to the civil society.

13. Interview # 23 to a male politician and social leader who has lived in the area for decades and provided detailed information about processes of productive reconversion in the east and west, as well as an assessment of the concentration of coca in the south.

References

- Agroguejar. (2012). Plan de Desarrollo Sostenible de Zona de Reserva Campesina Sector Guejar-Cafre Puerto Rico, Meta. Published online by the community. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/centrodedocumentacionanzorc/docs/plan_de_desarrollo_sostenible_de_la_c8173e8e0ae11c

- Asher, K., & Ojeda, D. (2009). Producing nature and making the state: Ordenamiento territorial in the Pacific Lowlands of Colombia. Geoforum, 40, 292–302.

- Asociación Nacional de Licencias Ambientales – ANLA. (2017). Reporte Area de Manejo Especial la Macarena. Bogotá: Autoridad Nacional de Licencias Ambientales.

- Bakker, K. (2005). Neoliberalizing nature? Market environmentalism in water supply in England and Wales. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 95(3), 542–565.

- Bakker, K. (2009). Neoliberal nature, ecological fixes, and the pitfalls of comparative research. Environment and Planning, 41(8), 1781–1787.

- Ballvé, T. (2012). Everyday state formation: Territory, decentralization, and the narco landgrab in Colombia. Environment and Planning, 30(4), 603–622.

- Baquero, J. (2014a). Layered inequalities Land grabbing, collective land rights, and Afro-descendant resistance in Colombia.

- Baquero, J. (2014b). Acaparamiento de tierras, regímenes normativos y resistencia social: El caso del Bajo Atrato en Colombia. In B. Göbel, M. Góngora-Mera, & A. Ulloa (Eds.), Desigualdades Socio-Ambientales en América Latina (pp. 435–458). Bogotá: Universidad Nacional.

- Los Farallones NNP, Barreto, L. (2013). Diagnóstico de la ocupación en el Parque Nacional Natural Farallones de Cali [Unpublished].

- Bejarano, A.M., & Pizarro, E. (2005). From ‘Restricted’ to ‘Besieged’: The changing nature of the limits to democracy in Colombia. In F. Hagopian & S. Mainwaring (Eds.), The third wave of democratization in Latin America (pp. 235–260). Cambridge University Press.

- Bocarejo, D., & Ojeda, D. (2015). Violence and conservation: Beyond unintended consequences and unfortunate coincidences. Geoforum, 69, February 2016, 176–183.

- Borras, S., Jr., Franco, J., Kay, C., & Spoor, M. (2011). Land grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean viewed from broader international perspectives (Transnational Institute Report). Santiago, Chile: FAO Office. Retrieved from https://www.tni.org/en/publication/land-grabbing-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-in-broader-international-perspectives

- Borras, S., Jr., Hall, R., Scoones, I., White, B., & Wolford, W. (2011). Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: An editorial introduction. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 209–216.

- Brockington, D. (2009). Celebrity and the environment: Fame, wealth, and power in conservation. London: Zed Books.

- Brockington, D., & Duffy, R. (2010). Capitalism and conservation: The production and reproduction of biodiversity and conservation. Antipode, 42, 469–484.

- Brockington, D., Duffy, R., & Igoe, J. (2008). Nature unbound: Conservation, capitalism, and the future of protected areas. London: Earthscan Publishers.

- Brockington, D., & Igoe, J. (2006). Eviction for conservation: A global overview. Conservation and Society, 4(3), 424–470.

- Brockington, D., Igoe, J., & Neves, K. (2010). A spectacular eco-tour around the historic bloc: Theorizing the convergence of biodiversity conservation and capitalist expansion. Antipode, 42(3), 486–512.

- Brockington, D., & Scholfield, K. (2010). The conservationist mode of production and conservation NGOs in sub-Saharan Africa. Antipode, 42(3), 551–575.

- Cárdenas, R. (2012). Green multiculturalism: Articulations of ethnic and environmental politics in a Colombian “Black community”. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 309–333.

- Castree, N. (2007). Neoliberal ecologies. In N. Heynen, S. Prudham, J. McCarthy, & P. Robbins (Eds.), Neoliberal environments: False promises and unnatural consequences (pp. 281–286). London: Routledge.

- Castree, N. (2008a). Neoliberalizing nature: The logics of deregulation and reregulation. Environment and Planning A, 40(1), 131–152.

- Castree, N. (2008b). Neoliberalizing nature: Processes, effects, and evaluations. Environment and Planning A, 40(1), 153–173.

- Centro Nacional, de Memoria Histórica. (2010a). La Tierra en disputa. Memorias de despojo y resistencia campesina en la costa Caribe (1960–2010). Bogotá: CNMH.

- Centro Nacional, de Memoria Histórica. (2014a). “Patrones” y campesinos: Tierra, poder y violencia en el Valle del Cauca (1960 – 2012). Bogotá: CNMH.

- Centro Nacional, de Memoria Histórica. (2014b). Putumayo: La vorágine de las caucherías. Bogotá: Memoria y testimonio.

- Centro Nacional, de Memoria Histórica. (2015a). Buenaventura: Un puerto sin comunidad. 2015. Bogotá: CNMH.

- Centro Nacional, de Memoria Histórica. (2015b). Una nación desplazada: Informe nacional del desplazamiento forzado en Colombia. Bogotá: CNMH – UARIV.

- Contraloría General de la Nación. (2013). Acumulación irregular de predios baldíos en la Altillanura Colombiana. Bogotá: Imprenta Nacional de Colombia.

- Corson, C. (2010). Shifting environmental governance in a neoliberal world: USAID for conservation. Antipode, 42(3), 576–602.

- De Rementeria, I. (2001). La Guerra de las Drogas. Cultivos ilícitos y desarrollo alternativo. Bogotá: Editorial Planeta.

- Devine., J. (2017). Colonizing space and commodifying place: Tourism’s violent geographies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 634–650.

- Devine, J., & Ojeda, D. (2017). Violence and dispossession in tourism development: A critical geographical approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 605–617.

- DNP. (2014). Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social República de Colombia Departamento Nacional de Planeación POLÍTICA PARA EL DESARROLLO INTEGRAL DE LA ORINOQUIA: ALTILLANURA - FASE I

- Duffy, R. (2005). The politics of global environmental governance: The powers and limitations of transfrontier conservation areas in Central America. International Studies Review, 31(2), 307–323.

- El Colombiano. (2018). Récords vergonzosos en siembra y producción de coca. Retrieved from https://www.elcolombiano.com/colombia/records-vergonzosos-en-siembra-y-produccion-de-coca-YD9360526

- El Espectador. (2009). Las masacres del Naya. Retrieved from https://www.elespectador.com/impreso/nacional/articuloimpreso148899-masacres-del-naya

- El País. (2010). Diez años del secuestro masivo del Kilómetro 18. Retrieved from https://www.elpais.com.co/cali/diez-anos-del-secuestro-masivo-del-kilometro-18.html

- El País. (2014). Secuestro de iglesia La María, 15 años de un cautiverio que unió a los caleños. Retrieved from https://www.elpais.com.co/judicial/secuestro-de-iglesia-la-maria-15-anos-de-un-cautiverio-que-unio-a-los-calenos.html

- El País. (2015). Minería ilegal. El cáncer de Los Farallones. Retrieved from https://www.elpais.com.co/especiales/mineria-ilegal-en-los-farallones/

- El País. (2018). Pese a denuncias, no se logra frenar minería ilegal en los Farallones de Cali. Retrieved from https://www.elpais.com.co/cali/pese-a-denuncias-no-se-logra-frenar-mineria-ilegal-en-los-farallones-de.html

- El Tiempo. (2019a). Crónica del mayor secuestro masivo de Colombia: El terror en La María. Retrieved from https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/cali/secuestro-masivo-en-iglesia-la-maria-en-cali-cumple-20-anos–368806

- El Tiempo. (2019b). Polémica por construcción de puesto de control minero en Farallones. Retrieved from https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/cali/puesto-contra-la-mineria-ilegal-de-oro-en-farallones-si-se-hara-394196

- ELEMENTA. (2018). Consultoría en derechos. Cultivos de coca en Colombia: Impactos socio-ambientales y política de erradicación. Bogotá: ELEMENTA Consultoría en Derechos.

- Fajardo, D. (1989). La colonización de la Macarena en la historia de la frontera agraria. In A. Molano, D. Fajardo, & J. Carrizosa (Eds.), La colonización de la reserva de la Macarena (pp. 119–125). Bogotá: Corporación Aracuara - Fondo FEN - Editorial Presencia.

- Fajardo, D. (1994). La colonización de la frontera agraria colombiana. In Machado, A. (Ed.) Minagricultura 80 años. El agro y la cuestión social (pp. 42–59). Bogotá: TM editores, Banco Ganadero.

- Fajardo, D. (2002). Para sembrar la paz hay que aflojar la tierra. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia – Instituto de Estudios Ambientales.

- George and Bennett. (2005). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge: MIT University Press.

- González, F. (1989). Poblamiento, problema agrario y conflicto social Controversia, volumen I, No. 151–152. Bogotá: CINEP.

- González, F. (1994). Poblamiento y conflicto social en la historia colombiana. In R. Silva (Ed.), Territorios, regiones, sociedades (pp. 13–33). Cali: Universidad del Valle – CEREC.

- González, F., Bolívar, I., & Vásquez, T. (2003). Violencia política en Colombia. De la nación fragmentada a la construcción de Estado. Bogotá: CINEP.

- Gónzalez-Plazas, S. (2007). La erradicación manual de cultivos ilícitos en la sierra de La Macarena: Un ejercicio sobre la futilidad de las políticas. Centro de Estudios y Observatorio de Drogas y Delito (CEODD) - Facultad de Economía. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario Bogotá.

- Grajales, J. (2011). The rifle and the title: Paramilitary violence, land grab and land control in Colombia. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(4), 771–791.

- Grajales, J. (2013). State involvement, land grabbing, and counter-insurgency in Colombia. In W. Wolford, S. Borras, R. Hall, I. Scoones, B. White, (Eds.), Governing global land deals. The role of the state in the rush for Land (pp. 23–44). Sussex: Wiley Blackwell.

- Grajales, J. (2015). Land grabbing, legal contention and institutional change in Colombia. Journal of Peasant Studies, 42(3–4), 541–560.

- Igoe, J. (2004). Conservation and globalisation: A study of national parks and indigenous communties from East Africa to South Dakota. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- INDEPAZ. (2015). Recoquista y despojo en la Altillanura. El Caso de Poligrow en Colombia. Amsterdam: SOMO.

- Kramer, T. (2009a). Neither war nor peace: The future of the cease-fire agreements in Burma. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

- Kramer, T. (2009b). Burma’s cease-fires at risk; Consequences of the Kokang crisis for peace and democracy. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

- Kramer, T., & Woods, K. (2012). Financing dispossession - China’s opium substitution program in northern burma. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute (TNI) Drugs & Democracy Programme.

- La Macarena NNP. (2011). Documentación y Caracterización de la Experiencia de Ordenamiento Territorial y Formalización de la Tenencia de la Tierra en sectores aledaños al Parque Nacional Natural Sierra de La Macarena, Municipio de Puerto Rico Departamento del Meta. (2007-2011)

- La Macarena NNP. (2018). Plan de Manejo 2018–2023. Retrieved from https://storage.googleapis.com/pnn-web/uploads/2018/07/PM-Macarena-JULIO-9-de-2018-1.pdf

- Llanes, J. (2017). Perspectivas del gasto en seguridad y defensa frente al pos acuerdo [Thesis]. Bogotá: Universidad Militar Nueva Granada.

- Los Farallones NNP. (2005). Plan de Manejo 2005–2009. Retrieved from http://www.parquesnacionales.gov.co/portal/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/PlandeManejoFarallonesdeCali.pdf

- Los Farallones NNP. (2017). Plan de Manejo 2015–2019 [Unpublished].

- Lugo, D. (2019a). “Prosperity for Everyone” in the post-conflict? How does environmentally and militarily oriented state (Re)Control in the ariari region propel productive segmentation and social fracturing? Revista de Estudios Colombianos No. 53. (enero-junio de 2019), ISSN 2474–6819 (Online).

- Lugo, D. (fortcoming - 2019b). ‘Peace’ and the conquest of the last agricultural frontier in Colombia? Ceasefire economies, segmented development, and titling of public vacant lands in Vichada. In G. Nárvaez (Ed.), Sociologías de la Paz con Enfoques Territoriales - Serie 1. Bogotá: Editorial Universidad Santo Tomás.

- Ministerio de Defensa Nacional. (2009). La fuerza Pública y los Retos del Futuro. Dirección de Estudios sectoriales. In Serie de Prospectiva (Vol. 3, pp. 39–47). Bogotá: Ministerio de Defensa Nacional

- Moore, D. (2005). Suffering for territory: Race, place and power in Zimbabwe. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- NCR. (2014). Desplazamiento Forzado y Violencia Sexual Basada en Género BUENAVENTURA, COLOMBIA: REALIDADES BRUTALES. Bogotá: ACNUR.

- Ojeda, D. (2012). Green pretexts: Ecotourism, neoliberal conservation and land grabbing in Tayrona National Natural Park, Colombia. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 357–375.

- Oxfam. (2013). Divide y comprarás: Una nueva forma de concentrar tierras baldías en Colombia (pp. 40). Bogotá: OXFAM.

- Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia - Dirección Territorial Orinoquía. (2015). Propuesta para la erradicación de cultivos de uso ilícito al interior y en las zonas con función amortiguadora de los Parques Nacionales Naturales. Bogotá: Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia. (Unpublished)

- Peluso, N. (1993). Coercing conservation? The politics of state resource control. Global Environmental Change, 3(2), 199–217.

- Peluso, N.L., & Lund, C. (2011). New frontiers of land control: Introduction. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(4), 667–681.

- Rodríguez, I. (2014). Despojo, baldíos y conflicto armado en puerto gaitán y mapiripán (Meta, Colombia) entre 1980 y 2010. Estudios Socio-Jurídicos, 16(1), 315–342. doi: 10.12804/esj16.1.2014.08

- Ruiz, M. (2006). Operación Colombia Verde – ¿Asunto de locos? Bogotá: Revista Semana. Retrieved from http://static.iris.net.co/semana/upload/documents/Doc-1297_200684.pdf

- Sinchi. (2013). Formulación Participativa del Plan Integral de Manejo del Distrito de Manejo Integrado (DMI) La Macarena Norte, del Área de Manejo Especial La Macarena “Amem”, Departamento del Meta. Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas “SINCHI”.

- Tinigua NNP. (2015). Plan de Manejo, 2015-2019.

- United Nations Office against Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2017). Informe de monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2016. Bogotá: SIMCI-UNODC.

- United Nations Office against Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2018). Informe de monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2016. Bogotá: SIMCI-UNODC.

- Van Heuveln, B. (2000). A preferred treatment of Mill’s methods: Some misinterpretations by modern textbooks. Informal Logic, 20(1), 19–42.

- Vandergeest, P., & Peluso, N. (1995). Territorialization and state power in Thailand. Theory and Society, 35, 385–426.

- West, P., Igoe, J., & Brockington, D. (2006). Parks and peoples: The social impact of protected areas. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35(1), 251–277.

- Woods, K. (2011). Ceasefire capitalism: Military–private partnerships, resource concessions and military–state building in the Burma–China borderlands. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38, 4.

- Ybarra, M. (2013). Privatizing the tzuultaq’a? Private property and spiritual reproduction in post-war Guatemala. In N. Peluso & C. Lund (Eds.), New frontiers of land control (pp. 133–150). New York, NY: Routledge.