ABSTRACT

This paper offers a critical assessment of how tourism development in the municipality of Los Cabos, Baja California Sur affects land and water use. Los Cabos is a seaside tourism Mecca located at the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula, in Mexico’s northwest. There, subsidised profits and a process of dispossession in the tourism sector have to do mainly with land and water appropriation in the form of restrictions to beach access by the local population, urban segregation and, in an arid region, privileging water provision for the tourism industry over the needs of the population. In order to sustain these claims, we map water and land use for tourism in Cabo San Lucas. We also analyse the expansion of the Los Cabos type of tourism to the small town of La Ribera, in the East Cape-Cabo Pulmo area, where marinas and high scale housing for residential tourism sprout along the coast. We argue that the seemingly ever-growing presence of tourism in the region carries with it an urgent call for the reappraisal of current approaches to land and water use, if local resources are to deliver quality of life for the population, and not only economic profitability for (mostly) foreign capital. Analytically, we address these issues by unpacking David Harvey’s concept of accumulation by dispossession, which – we argue – is for our purposes a broader tent than the (mostly Latin American) theorisations on extractivism, as we explain later in the relevant section of the paper.

1. Introduction

Land and water grabbing rank high in the worldwide intensification of extractive activities as a key feature of the global competition for access and control of natural resources, especially in peripheral regions. The uneven and intensive appropriation of resources connected to those extractive activities is traditionally associated with mining, agriculture and industry, but – we posit – also occurs in the services sector, particularly in tourism, a composite activity the involves land appropriation and construction, as well as lodging and food and beverages. The effects of such intensification raise questions about power and legitimacy, social responses to processes of change, and the possibilities for sustainability (Frederiksen & Himley, Citation2019), as well as social justice (Harvey, Citation2004).

Although the economic benefits of tourism activities have been heavily stressed by governments, concerned non-governmental organisations, critical academics and local populations have demanded industry representatives and tourism developers to address the social and environmental justice impacts of tourism activities (Krippendorf, Citation1982). As shown in the second section of this paper, a line of research has recently developed to study tourism from a critical perspective, exposing the linkages between tourism and global capital expansion. Since tourism relies heavily on land(scape) and natural resources, the analysis of the industry’s extractive practices in a key destination is a means to test the argument of tourism’s uneven appropriation and dispossession of such resources.

This paper offers a critical assessment of the effects of tourism growth in the municipality of Los Cabos (Baja California Sur, Mexico) on land and water use. Los Cabos (known abroad as ‘Cabo’) is located in the country’s north-western Baja California peninsula. Los Cabos is one of the seaside resorts included in a five-site government-led program set in the 1970s to develop ‘Integrally Planned Tourism Centres’ (CTIPs in Spanish), among which Cancun towers as an internationally-known resort destination. CTIPs were justified with the argument that, as development poles, they would stimulate growth in lagging regions (Gámez, Citation1993). The government gave initial impulse to CTIPs by facilitating the acquisition of land at cheap prices, building the basic infrastructure required for the provision of public services and ensuring terrestrial, maritime and air connectivity to attract investments. The further development of CTIPs, including all tourism infrastructures, would be in charge of the private sector.

Los Cabos took off in the 1990s and – save the catastrophic effects of the 2008 global financial crisis – has been growing ever since. Along the 32-kilometre\tourist corridor between the cities of San José del Cabo and Cabo San Lucas, massive hotels and second homes complement high-end amenities and residential neighbourhoods. Currently, mostly fed by foreign investment and United States (U.S.) and Canadian visitors, Los Cabos – as the area is locally referred to – is one of the most dynamic beach tourism destinations in Mexico.

Baja California Sur has a population of approximately 800,000 people, but tourists – most of whom flock to Los Cabos – more than double this figure. As the number of visitors has risen, the tourism sector’s profitability has increased apace. At the same time, the rapid growth of the formerly small towns of Cabo San Lucas and San Jose del Cabo has made the municipality of Los Cabos the most populous in the state. Los Cabos continues to attract labourers from the less affluent regions of Mexico, as well as foreign blue and white-collar workers and expatriate immigration from the U.S. and Canada. In a place where land and landscape are highly priced, access to housing is markedly dependent on income. Thus, a clear social divide shapes urban life. This is most in evidence in the form, type and location of housing: on the one hand, seemingly never-ending, feeble peripheral settlements house most Mexican newcomers; on the other, luxury residential developments pop up along the coastline for those who can afford them (Bojórquez & Ángeles, Citation2014).

Tourism activity has long overgrown the boundaries of the original urban polygon, and hotels, residences, marinas and golf courses have expanded northward along the Pacific seashore (El Pescadero, Todos Santos) and eastward on the Gulf of California coastline (La Ribera, Los Barriles). Although tourism has heavily influenced life in those communities, La Ribera stands out because of the disproportionate levels of investment and size of the tourism projects under way as compared to the dimension of the town, of merely 2,300 inhabitants, most of them originally farmers or fishermen (Niparajá, Citation2011).

This paper seeks to understand the rapid rates of tourism growth in Los Cabos and its patterns of expansion in order to account for the reshaped landscape and the appropriation of land and water resources by tourism interests, as well as their social implications. Critical accounts of tourism growth are needed because they involve questions about how society’s resources are distributed; about social justice. Thus, they raise important issues in the public agenda, such as: How fair is the access to public goods and space? What processes and outcomes are involved in the making of individual and social identities in tourism destinations? On which basis is tourism income distributed and why? What is the extent of environmental costs/externalities related to the growth of tourism? Who are the winners and losers?

Some studies have already addressed those questions with a view to the region under study in this paper (Gámez, Citation1993; López-López, Cukier, & Sánchez-Crispín, Citation2006; Bojórquez, Citation2014; Bojórquez and Angeles Citation2014; Anderson, Citation2017; Graciano, Citation2018). These authors critically examine tourism growth processes that increase private wealth but deepen social divides. Yet, no one so far has offered a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches that employ land and water use maps as key indicators of an on-going process of accumulation by dispossession; nor has the process of tourism expansion been applied to La Ribera in this manner. David Harvey’s ‘accumulation by dispossession’ (Harvey, Citation2004) concept is used here to explain how and why tourism development rests upon the alienation of land and water. In Los Cabos and elsewhere land is needed for the construction of tourism facilities (hotels, restaurants, second homes, etc.); water is required to slake the visitors’ thirst, and that of the hotels’ golf courses. In such a context, La Ribera becomes a good example of the early stages of the kind of tourism expansion and accumulation by dispossession experienced in Los Cabos since the 1990s.

1.1. Methodology

Both quantitative and qualitative research techniques were used for this analysis. On the one hand, in order to account for the reshaped landscape and water use, data on water and land distribution with relation to tourism facilities and households in Cabo San Lucas and in the Corridor served to map patterns of resource appropriation. Maps 2, 3 and 4 are based on online cartographic material from Mexico’s National Institute for Geography and Statistics (INEGI in Spanish), National Commission for Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO), and Secretariat for the Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT). Information from those sources and satellite images from the SAS Planet programme were filtered through ArcGis 10.3 and QGIS 2.6.1. The set of vectorial data was obtained from INEGI’s National Geostatistical Framework, originally in the ‘Shape’ format and employing the Lambert Conical Conformation (CCL) as their geographical projection with reference to datum ITRF92; this was then converted to datum WGS84/UTM. Once the official geographic information was received and the information processed, the following maps were prepared:

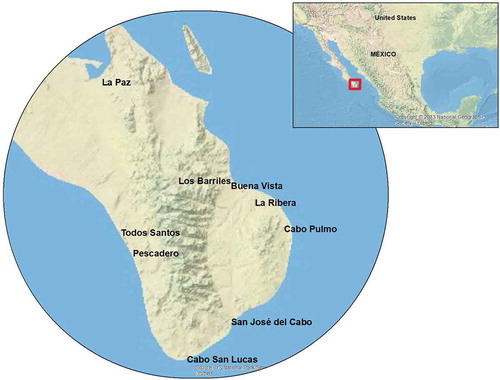

: shows the delimitation of the study area according to the INEGI cartography at 1:250,000 scale.

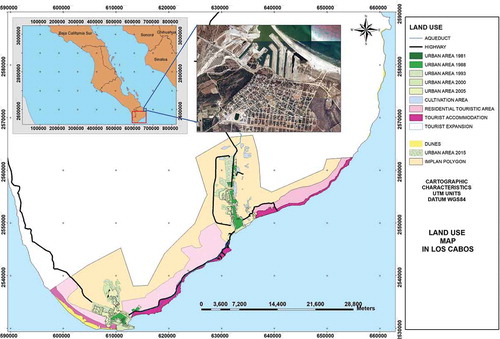

: presents land use in Los Cabos on the municipal government’s Urban Development Plan 2040, the document that so far leads urban growth in Los Cabos and according to the INEGI’s cartography at 1:250,000 and at 1:50,000 scale.

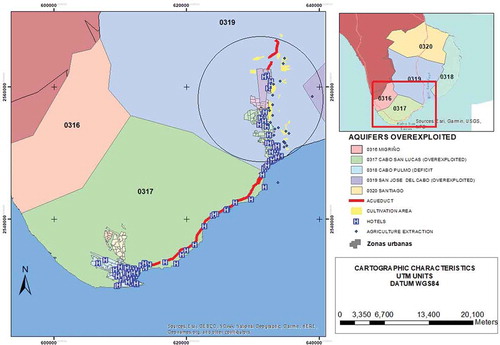

: spatial identification of the aquifers and the hotel zone in general included in the municipality of Los Cabos, based on the cartographic information from the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) and the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO) at 1:250,000 scale. The location of hotels was obtained from the National Statistical Directory of Economic Units (DENUE) at 1:50,000 scale.

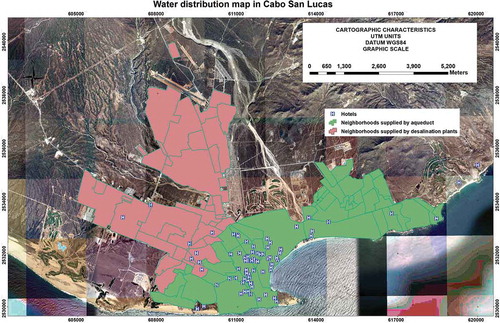

: presents water distribution in Cabo San Lucas by supply source, based on information obtained from CONAGUA and INEGI’s cartography at 1:250,000 and at 1:50,000 scale

Content Standards for Digital Geospatial Metadata were observed in employing official information.

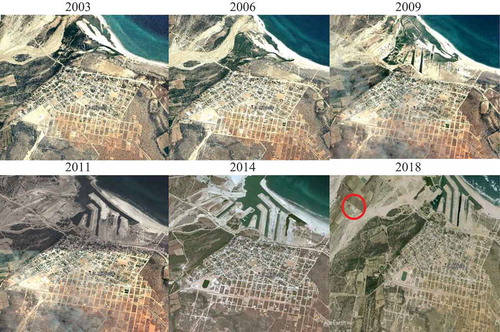

For the elaboration of , Google Earth Pro (version 7.3.2.5776) was used, superimposing Historical Imagery to track changes to the coastline as a function of time. On the other hand, in order to identify social perceptions in La Ribera, electronic media coverage was followed up using ‘environmental water conflicts’ and ‘land use’ as search criteria, and interviews were carried out there to assess the inhabitants’ perceptions about the process of tourism growth in their community (see Appendix A. Interview items). Considering population size, a non-probabilistic sampling technique was applied. Using snowball sampling, by which initial participants referred to potential interviewees, 20 adult people were approached using a semi-structured interview format in February and June 2019.

Figure 1. Littoral modifications in La Ribera, Baja California Sur (East Cape), 2003–2018 (Google, Citation2019).

The study started by locating adults residing in La Ribera for 15 or more years; once interviewed, they were asked to recommend a person who met these criteria to be interviewed. In the event that the person referred to was not present at the time of the visit or refused to answer the interview, another recommendation was sought. The use of any non-probability sampling methods could cast doubts about sample representativeness when making inferences about populations based on the obtained sample (Voicu, Citation2011), however, snow ball sampling was a useful research tool in La Ribera small community, due to the limited number or predisposition of local inhabitants towards answering outsider’s inquiries.

Apart from two college students in their early twenties, the rest of the respondents were 40 years old or above. The majority was employed in small business (trade, fishing, bar-tending, school teaching), but the group included two housewives and a former local government official. Since the aim was to identify the perceptions of average locals about tourism growth in La Ribera, neither high tourism resort and marina agents nor public officers related to tourism were specifically approached, under the assumption that they were prone to support the type of tourism expansion underway in the area. It is worth mentioning that a member of the community (an undergraduate student at the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur, campus Los Cabos) made the interviews possible, since people initially refused to answer; in the end, except from two persons, they asked to remain anonymous.Footnote1 Systematic content analysis (López, Citation2002) was performed to data obtained from the interviews.

After this introduction, the paper is divided into five sections. The first reviews Harvey’s argument about accumulation by dispossession, and the role of tourism in this process as exemplified by cases in Spain and other parts of Mexico. The second offers a general overview of the tourist economy of Los Cabos. The third unpacks an analysis that uncloses the uneven land and water distribution in Los Cabos, which clearly favours hotels and tourism facilities over the needs of the local population. The forth, briefly, refers to La Ribera inhabitants’ perceptions about tourism growth in their community. In the last section, concluding remarks are presented to assess the application of the accumulation by dispossession argument to land and water use in Los Cabos.

2. Accumulation by dispossession in tourism

David Harvey coined the phrase ‘accumulation by dispossession’ to underscore the fact that this type of accumulation, mediated by legal or extra-legal actions, has become a permanent feature of capitalism. Harvey’s point is to create awareness of the survival of Marx’s primitive accumulation (Marx, Citation1976) in a great variety of new forms that have become key elements for the progress of the existing economic system. Harvey’s aim is to show the dependence of markets on forces formally unrelated to them that, nevertheless, play the role of assigning disproportionate power and resources to the owners of capital (Harvey, Citation2004). If, as Thomas More claimed, 16th Century England was a place where ‘sheep ate men’ through the application of the commons for pasturage (More, Citation2016), in our time capital eats men in many different ways. Besides paying very low wages to most if their employees for very long hours of in wearing and often mindless jobs, tourism capital takes over the land and water that, in different circumstances, could be used for the benefit of the population at large.

In Harvey’s updating of Marx’s primitive accumulation there are new mechanisms of dispossession, different from but related to those that Marx examined, for instance: 1) the development of novel forms of intellectual property rights and the creation of patents on genetic material; 2) the depredation of the global commons – air, land and water – for industrial processes; 3) the privatisation of formerly public assets, such as water, education and all sorts of services; 4) the elimination of regulatory frameworks so that rights such as those to a pension, public health services, and welfare are constantly under threat, if not forgone. Using a phrase that brings to mind the process of depopulation or rural England from the 15th to the 19th centuries, Harvey asserts that, taken together, these phenomena constitute ‘a new wave of enclosures of the commons’ (Harvey, Citation2004, p. 74).

Thus, although Marx’s primitive forms of accumulation still remain (for instance, displacement of peasant populations and the formation of a landless proletariat; privatisation of formerly common property resources, such as water) (Harvey, Citation2003, p. 144–145), new mechanisms of accumulation by dispossession have emerged in a process he calls ‘flexible accumulation’ (Harvey, Citation2004). This process of primitive accumulation is mediated by the ‘appropriation and co-optation of pre-existing cultural and social achievements’ Harvey (Citation2003, p. 146). Since these achievements (cultural traits, institutions, knowledges, social relations, and so forth) differ among regions, varied forms of accumulation and dispossession emerge, but combine along with the depletion of the global commons and ‘wholesale commodification of nature in all its forms’ (Harvey, Citation2003, p. 148). This process, aided by the State, to release devaluated assets (labour, land), which were accumulated by dispossession, aerates the capitalist system giving it a way out to its crises.

Harvey’s accumulation by dispossession has largely been ignored by mainstream scholars of tourism, indeed, of almost any area of social research. However, it has not lacked negative evaluations from some critical authors in the global North, who have condemned it as unnecessarily expansive and all-encompassing (Brenner, Citation2004; Fine, Citation2004). In the global South, some authors have faulted the concept for its ostensible disregard of imperialism (Das, Citation2017), despite Harvey’s numerous writings on the subject. In Latin America, the concept has run afoul extractivism and postdevelopment scholars. In particular Eduardo Gudynas, a key author on extractivism who writes from a social ecology standpoint, has termed Harvey’s interventions in Latin America ‘sympathetic colonialism’ (colonialismo simpático) (Gudynas, Citation2015).

Despite important differences of opinion and outlook, stemming in Latin America from the need to produce autochthonous research grounded on local realities (and a postdevelopment outlook) (Escobar, Citation2012) and not on Harvey’s professed universalism, we think that there is a way to reconcile viewpoints. This could be done by looking at both strands of thought as complementary, rather than rival approaches at least where extractivism is concerned; although not necessarily much farther than that. In our opinion, such an approach vindicates our reliance on accumulation by dispossession; a concept that, on the other hand, seems to us of greater analytical scope, especially when dealing with the services sectors of the economy, in which extractivism tends to be more diffused as compared to mining, for instance.

During the current so-called planetary urbanisation era (Brenner, Citation2014) across most of the world but especially in the global South, immense amounts of rural land have been converted to urban uses; and ongoing socioeconomic processes have made cities into products at the service of capital accumulation. The commodification of cultural forms and histories has opened up new opportunities for accumulation by dispossession in the way of a flourishing tourism industry in urban and rural areas. It is in this context that we argue that a process of accumulation by dispossession conceals the appropriation of land and water in Los Cabos through limited access to beaches, privileged tourism industry access to water over local inhabitants’ needs, and urban segregation. The following sections expand on the flexible accumulation process as linked to tourism

2.1. Tourism and flexible accumulation

Tourism is not a new phenomenon. It has been an important economic and leisure activity in high-income countries since the heyday of the Fordist-Keynesian mode of regulation during the middle years of the last century (Cornelisson, Citation2011; Lefebvre, Citation2014). Yet, it only became world-embracing during the current period of globalisation, adopting many of the characteristics of the neoliberal project in place in most of the world since the 1980s (Mosedale, Citation2016). For instance, traditional sun-and-beach tourism involves different levels of deconstruction of ‘original’ nature and the construction of ‘modern/postmodern’ spaces.

The political and economic organisation and governance of such spaces in coastal areas has entailed the multi-scale commercialisation of land and natural resources, among which water and landscape tower because of their centrality to the success of tourist-related businesses. Thus, a specialised economic architecture moves into place in order to accelerate the marketisation of spaces once considered part of the commons and, as such, not subject to economic pricing. These market-oriented practices have a central role in certain economies, particularly where tourism has become the mainstay of economic activity (Castree, Citation2008; Artigues, Citation2001:108; López, Citation2011).

At present, tourism is one of the most dynamic economic sectors worldwide. It accounts for about 4% of the world output and 10% of jobs worldwide (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2018); as such, it is being acknowledged as a tool for development and economic recovery. Governments align their public policies to the tourism market, which in turn contributes to the very growth of this economic sector (UNWTO, Citation2017). In general, the developmental objective, understood as an improved standard of living and a rising quality of life for the local population has seldom been met. As Spirou (Citation2011) has recorded, especially when seaside megaprojects have been the attractor of investment flows the trend towards the growth of tourism and the neglect of development runs unabated. When this fact is pointed out, tourism’s public and private sector spokespeople simply conflate development with growth.

Extensive coastal tourism, often achieved through rapid, unplanned building with all its associated social, environmental and political consequences, came to be known as balearisation, as a result of the type of tourism growth in the Spanish Balearic Islands in the early 1960s. Made up of three islands with a total area of 4,492 km2, the Balearic Islands have a resident population of slightly over 1 million people, of which about 30% are foreigners (INE, Citation2015). In addition, the Islands host almost 10 million tourists, many of them British and German. Balearisation exemplifies the effects that tourism can have over land and other resource appropriation: it is not just an example of special deconstruction and reconstruction, but of capital accumulation fuelled by the appropriation and domination of spaces that were previously fragmented for commercialisation by tourism entrepreneurial forces (Lefebvre, Citation1976; Mosedale, Citation2016; Murray, Citation2015).

Lefebvre’s fragmented vision of urban space is clearly noticeable in a tourist city, in view of the ever-present gated communities, marinas, elite golf courses, and privatised beaches, that is, the commodification, among other dimensions, of space and nature, which coexist with non-tourism settlements and zones. Since tourism dynamics are highly attractive to other economic sectors, such as real estate, urban land speculation and space privatisation, these other sectors are promoted at a higher rate and scale.

The Balearic tourism model has gone global to transform and assimilate any suitable beach destination into the capitalist system. The unsustainability of the model is marked by the highly unequal appropriation of space and resources (Blázquez, Murray, & Artigues, Citation2011; Cañada, Citation2010; Murray, Citation2015; Palafox, Citation2017). The transformation of the Balearic Islands into the second most-visited place in Spain (after Barcelona) led directly to the destruction of the littoral (Blázquez, Murray & Artigues, Citation2001). In Iván Murray’s words referring to Spain’s housing and residential tourism boom of the early years on this century: ‘Spanish capital eats land’ (Murray, Citation2015). This reinforces the view that when society-nature relationships are transformed, both land and water become commodities that respond to different types of appropriation and privatisation (Martínez, Citation2011). It also strengthens our view on the reliance of Los Cabos tourism on cheap and plentiful land, and a secure provision of water to meet its needs. In Los Cabos, then, tourism capital eats meat and drinks water.

2.2. Balearisation in Mexico

The Balearisation phenomenon, that is, the physical and social transformation of coastal sites for tourism and financial capital, is not exclusive to Spain. Currently, parent world hotel chains have been established in Africa, the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico, among other regions. Particularly in Mexico, the unequal appropriation of space and resources linked to tourism is a well-known phenomenon. Since the 1990s, as part of the group of the so-called emerging economies, this country underwent a process of economic liberalisation that facilitated foreign investment. Tourism had been opened to foreign investment in a limited way before this, but with the new neoliberal regime international hotel chains expanded as not seen before.

The liberalisation of the Mexican economy is a main factor when explaining the expansion of tourism and the success of CTIPs seaside resorts, such as Cancun and Cozumel in Quintana Roo, and Los Cabos in Baja California Sur; but, also, the rebirth of more traditional destinations such as Acapulco and Mazatlan, as well as the second phase of CTIPs launched in the last decade along the Mexican Pacific coast. With government support, Mexico leaped from eighth to sixth place in the world ranking of international arrivals (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2018). The waves of new capital in tourism along the coastline had at least two clear consequences: they modified the shape and use of natural resources, and deeply transformed social and economic interactions as resort enclaves emerged. That is:

tourism that generally operates within a clearly demarcated, self-contained environment. Typified by high capital investment from large national and international corporations, or powerful interests, tourism enclaves contain a large number of facilities for tourists. Tourist activities and movements are arranged to facilitate maximum expenditures within the enclave while access to locales outside the enclave is often restricted and regulated. Not surprisingly, enclavic forms of tourism play a significant role in creating dependencies and adverse impacts such as lack of local control and local ownership, marginalization of local benefits, and prevention of meaningful interactions between residents and tourism (Healy & Jamal, Citation2017).

In his analysis on the impacts of tourism on coastal areas, tourism has been particularly influential in the definition of five main features of the Mexican coastline: a) land use competition; b) mass immigration that intensifies pressure on formal and informal labour markets; c) conflicts over water supply; d) increased regional infrastructure; e) conflict of interests over natural resources; and f) polluted water, beaches, and coral reefs (Gormsen, Citation1997). Government support to tourist enclaves focused on economic aspects (foreign investment and employment), land use (acquisition of large land extensions) and infrastructure creation (highways, airports, marines) (Brenner & Aguila, Citation2002). But the frenetic rush to develop was accompanied by unplanned cities, unfit settlements for workers, environmental stress, pressure on government agencies to deliver public goods, and a social divide that clearly separated mostly foreign tourist and second-home owners from the local population (Anderson, Citation2017; Hiernaux-Nicolas, Citation2005; Torres, Citation2005). At present, a new tide of seaside resorts along the Mexican Pacific coast is being promoted by FONATUR, under the same considerations as CTIPs (FONATUR. Fondo Nacional de Fomento al Turismo, Citation2019).

In Cancun, the first of the five original CTIPs and Mexico’s leading seaside resort, tourist space is clearly separated from the living space of local residents. Its urban configuration shows uneven development, inequitable power relations, and the control of space by the powerful, that only can be explained by the multiscale interaction between transnational forces, local elites and governmental agents. Cancun exemplifies the role of specific actors in flexible accumulation processes: government officials marketing the destination, national and international hotel brands which have taken over the sand bar and mangroves facing the Mexican Caribbean, and also a vast array of economic and social groups participating in what Harvey calls ‘appropriation and co-optation of pre-existing cultural and social achievements’. All things considered, it seems reasonable to advance that the current tourism model promoted in Mexico’s seaside resorts rests under the logic of flexible accumulation. This also, explains the reasons against transforming such a status quo.

The following section introduces Los Cabos’s main climatic features, as well as the patterns of land and water use

3. The tourist economy of Los Cabos

Los Cabos (see ) is bordered by the municipality of La Paz to the north, the Gulf of California to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south. Occupying 3,750 km2, it represents 5.2% of the state’s total surface area. It is an arid region (Latin: āridus, ‘lacking humidity’) that depends on the availability and recharge of groundwater. The contrast between the state’s semi-desert lands and sea landscapes has contributed to Los Cabos success in the world tourism market.

Climate in Los Cabos ranges from hot desert and dry temperate, which coexist with a variety of microclimates throughout the territory. Temperatures can exceed 40°C in the summer, and the annual average precipitation is 262.7 mm. Aquifers are the main source of water for human and productive uses. The combination of diverse geographic, geomorphologic, geological, and climate factors is fundamental in determining water availability. But aridity is more than a drought resulting from water scarcity or in limited supply (be it surface or underground); it is the result of a combination of diverse geographic, geomorphologic, geological and climate factors that are fundamental to determine water availability, mainly related to the reduced rainfalls. Average monthly rainfall during the hurricane season is about 65 millimetres and almost nil the rest of the year. These elements combined with the yearly arrival of nearly 2 million tourists for average stays of 4.1 days in over 16,000 hotel rooms make Los Cabos a unique region in Mexico in terms of land/water stress (Bojórquez, Ángeles, & Gámez, Citation2019; Graciano, Citation2018; Troyo et al., Citation2013).Footnote2

The services sector (commerce, restaurants, and hotels) produces 28% of total added value (INEGI. Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística, Citation2014) and is highly demanding when supplying water to hotel rooms, pools, and golf courses. Private-sector value added stood at MXN 10.6 billion (bn), or approximately USD 535 million (m). A third of this (about USD 180 m) was generated by the hotels, restaurants and bars sector. Research shows that half of construction activity, a third of commerce, and half of real estate directly relate to tourism, so that tourism value added rises to just over 50% in the municipality (Angeles, Gámez, & Ivanova, Citation2009; Bojórquez et al., Citation2019). Significantly, even though employment levels share a similar proportion, wages and salaries were just 30% of value added (16% in hotels, restaurants and bars), the rest being profits, interest and rent payments.

Tourism in Los Cabos began in the 1940s and 1950s, when wealthy Americans, led by film actors John Wayne and Bing Crosby, flew down from Los Angeles for sport-fishing and relaxation. In the late 1970s the National Tourism Fund (FONATUR) began its CIPT policy and included San José del Cabo in its plans, which led, in 1981, to the creation of the Los Cabos municipality. By 1990, when Los Cabos was first included in the Mexican Census survey as separate from La Paz, the state capital, it had a total population of about 35,000 people, who lived mostly in the town of San José del Cabo. The latter was the traditional administrative and political power centre, and Cabo San Lucas rapidly morphed from a fishing village into a first-class tourist destination (Bojórquez, Citation2014).

Harvey’s theory of accumulation by dispossession (Harvey, Citation2004) has been found to be useful to explain that process. Ejido landFootnote3 was firstly acquired through forcible but ‘legal’ expropriation, and later both by expropriation and legal purchase at very low prices, in order to build workers’ housing. Ejido land amounting to 386 hectares was expropriated for that purpose between 1981 and 2000 (Bojórquez & Ángeles, Citation2014). Thereafter, rapid population growth impelled further expropriations: for the construction of the huge Colonia Lomas del Sol, whose current population, estimated at just over 64,000 people is approaching the numbers for Cabo San Lucas 81,111 inhabitants (Gobierno del Estado de Baja California Sur, Citation2017).

Thousands of hectares were required to house the new arrivals, but they proved to be insufficient. Homeless families, most of them without formal employment and thus immersed in the informal economy, have taken possession of large areas of the municipality, mostly away from the seashore and lacking public services (water provision, sometimes even electricity, often security, always unpaved and badly served by public transport). Bojórquez et al. (Citation2019) also explain the take-over of beach space by tourism corporate interests, as well as popular resistance to them. Clearly, Harvey’s accumulation by dispossession has significant economic, ecological, social, and cultural effects. Land and water availability play an important role in the Los Cabos type of social and economic structure.

4. Land and water use in Los Cabos

In this section maps 2, 3, and 4 are used to explore the processes of balearisation and accumulation by dispossession in Los Cabos. focuses on land use, whereas maps 3 and 4 show a spatial projection of water distribution and the effects generated by tourism growth in the coast. Tourism is the main land user in Los Cabos. The Urban Development Plan 2040 (IMPLAN Los Cabos, Citation2013) only focuses on a 55,000-ha polygon, which was divided into three broad areas: Current Urban Zone, Growth Reserve, and Ecologic Preservation. The current urban area comprises the cities of Cabo San Lucas (CSL) and San Jose del Cabo (SJC) which, together, are 7,059 ha. The so-called ‘suburban area’ (that is, the highly urbanised tourist corridor) covers 7,230 ha; while more than 1,000 ha (three quarters of them in CSL) are used for the different tourism activities available to visitors of both cities (hotel accommodation, residential, golf courses, etc.). In addition, the tourist corridor has over 8,500 ha that have been approved for tourism use, while SJC accounts for 4,000 ha.

This is shown on , as follows. The elongated space that runs along the seashore, shown in deep pink, is meant to signify the existing tourism corridor, specifically hotel structures and related facilities and amenities. There is a light black line that goes parallel to the corridor between the deep and the light pink areas: this is the original coastal road built by the Mexican government that has been partly privatised. Although it is still used by the population to transit between CSL and SJC, the road is meant to access the hotel zone. The Urban Development Plan registers 38 beaches in the municipality, but 26% have been privatised by various hotel chains (IMPLAN Los Cabos, Citation2013, p. 173), thus effectively banning the population from the seaside. Access to beaches is impeded by perimeter fences and security guards, unless the visitor has a valid reason to be there, namely being a guest. In 45% of all beaches, locals are formally admitted and have parking facilities. However, in 55% of the beaches either the public is not admitted or access facilities and parking are lacking.

The area shown in lighter pink denotes spaces for residential tourism accommodation and housing. The built environment within urban areas is shown in green. The area in yellow is covered by dunes and, although construction is not legally permitted there, ways have been found to skirt the letter of the law. The light brown area, which accounts for the rest of the polygon, is considered as an ecological reserve, at least according to the existing Urban Development Plan. Overall, given that in 1981 the urban area (that is, the cities of CSL and SJC, but not the tourist corridor itself) comprised 65 ha and that in 2015 the amount was 7,050 ha, in a 34-year period the urban area expanded 10,746%.

However, every municipal administration has the legal right to change the terms of the plan, and this has been the case, presumably influenced by the Consejo Coordinador Empresarial (Business Coordinating Council, which includes hoteliers and investors), which has a seat on the Planning Board and, given the entrepreneurial character (Harvey, Citation2016, ch. 6; Vives Miro, Citation2011) of the Los Cabos urban growth machine (Parker, Citation2015, ch., p. 7) has the deciding vote. A recent example of the power of this group is the privatisation of part of the existing tourist corridor by having the municipality build a new road farther inland, so as to divert local traffic from the hotel area and provide space for the construction of a new hotel (Reyez, Citation2016). Although not included on the map, Los Cabos boasts 12 golf courses and is considered one of the fifteen best golf destinations in the world: three of its courses are in the top 100. Additionally, Los Cabos has 11 marinas with 864 slots, denoting ‘the luxury environment that it seeks to provide’ (SECTUR. Secretaría de Turismo, Citation2014).

Mexican National Waters Law states that CONAGUA is bound to publish its data on groundwater availability for each aquifer and update the data at least every three years. In the last update, CONAGUA estimated a total recharge of 66.2 Mm3/year for the aquifers of Los Cabos, where SJC (0319) provides 54%, followed by Santiago (0320) with 37%, and the rest (9%) is provided by the other aquifers (see ).

Table 1. Average annual water availability (CONAGUA, 2015).

represents the location of the aquifers and urban areas, showing hotel and tourism facilities growth, along the aqueduct’s geographical pattern. Five aquifers water the area of study but all have been subject to limited extractions for domestic, industrial, agriculture irrigation and other uses since 1954. According to CONAGUA, the San José del Cabo aquifer is overexploited due to extraction of more groundwater than its natural capacity to recharge. This aquifer supplies water to the Tourist Corridor, urban zones, and the main agriculture area.

The extractivist expansion of the tourism frontier depends on water availability. The latest update (CONAGUA, 2015) showed considerable discrepancies with regard to data from 2009, when a lower deficit was reported by the municipal administration. This type of public policy contradiction is known as paper water; in other words, water volumes that are only written on the paper with the purpose of continuing to over license and overexploit waterbodies in pursuit of economic growth at the expense of the environment.

shows water distribution in Cabo San Lucas. The green area (the tourist zone) has a secured source of water, as it is supplied by the municipal water system that feeds from the aquifer. But in the brown area, where most of the population lives, water is provided by a privately-owned desalinisation plant.

Water consumption in hotel rooms varies according to the services provided in each facility. Hotels are classified into five categories: the higher the category, the higher the number of services provided, and the better their quality. Thus, a 5-star hotel consumes more water than other categories. In Los Cabos, 90% of hotel rooms are in 4- and 5-star hotels (10 and 80% respectively), luxurious facilities that offer superior and exceptional services (room size, meeting rooms, sport facilities, spa services, pools, recreational activities, green areas, parking lots, elevators, among many others).

A five-star hotel room uses an average of 1.5 m3 of water each day (m3/d), equivalent to the water consumption of 4.3 people.Footnote4 According to some environmental impact manifestations consulted, it was estimated in some cases water consumption of hotel rooms and golf courses was estimated up to 2 m3/day for each hotel room and 3,000 m3/day per golf course. Thus, 15,000 hotel rooms use 23,000 m3/d, which is enough to satisfy the needs of 63,000 people per day. An 18-hole golf course requires an average of 2,300 m3/day of water, equivalent to the domestic consumption of more than 8,000 people (Graciano, Citation2018, p. 167). In the meantime, 57,000 people in Los Cabos face shortages and depend on a limited water supply (Graciano, Citation2018, p. 155). In shanty towns and settlements in the periphery, people must pay an overprice to private water operators (‘tankers’). Barkin (Citation2006) describes this situation as a differential burden imposed on the most vulnerable social groups who are forced to pay high water prices and dedicate long hours to carry, purify, distribute and dispose of water.

The expansion of tourism in Los Cabos is not limited to the polygon set in the Urban Development Plan, but expands along both the Pacific and the Gulf of California coastlines, driven by the current trend of building enclave type seaside resorts along the municipality’s seashore. Although further studies need to be conducted to develop a more detailed understanding of how local inhabitants perceive such tourism growth, the following section focuses on the La Ribera community in an attempt to shed some light onto this matter, relying on qualitative research through the use of interviews as above mentioned in the methodology section.

5. Tourism and land and water use perceptions in La Ribera

As has happened with many other communities along the seashore in Baja California Sur, in La Ribera locals are in danger of being displaced by tourism growth. A project that started in 2007 but was stopped by the 2008 financial crisis has recently been reactivated with fresh funding under a new name, Costa Palmas East Cape. This project includes 141 hotel rooms, 19 private homes, 45 undeveloped residential lots, a golf course, a yacht club, and a marina. The Costa Palmas East Cape project is adjacent to Cabo Pulmo National Park, the living coral reef that is one of the main tourism attractions of the East Cape. Another large-scale project called ‘Cabo Cortes’ was proposed south of La Ribera around the same time, which planned to build 25,000 hotel rooms and residential accommodations, as well as sufficient housing for all the ‘support workers’ that visitors and new tourism residents would need (Angeles et al., Citation2009).

The magnitude and the expected social, economic and environmental impacts of such a project on the Cabo Pulmo natural protected area activated protests in favour of sustainability involving residents of the town of Cabo Pulmo and local academics. These actors were supported by nationally and internationally funded conservation organisations that have been present in the area for more than two decades (Gámez, Citation2008; Masse Magana & Guzmán Hernandez, Citation2015). Although the Cabo Cortes project was stopped in 2014 by Presidential decree, the Costa Palmas East Coast project (previously called Desarrollo Turístico-Náutico La Ribera or Cabo Riviera) has stirred old debates about the desirability of the changes brought about by tourism (Niparajá, Citation2011). The complaint is that the newly begun construction of residential units alongside the project’s marina has monopolised the use of the town’s water, forcing locals to rely on expensive tankers (SDPnoticias, Citation2019).

La Ribera illustrates the rapid and structural transformation of the East Cape littoral due to tourism. It is also an example of the type of land and water use problems present in the San Jose del Cabo-Cabo San Lucas Tourist Corridor. La Ribera depends on a single well for urban use and wells in neighbouring ranches for small agricultural and livestock producers. It is likely that mega tourism projects will exert pressure on water provision, which can adversely affect local inhabitants.

As to the spatial configuration of la Ribera, satellite images in show the change in the coastline brought about by the Costa Palmas East Cape marina.

Between 2003 and 2018, this marina has expanded so much that now it almost matches the size of La Ribera township. During that 15-year period, residential settlements have also grown based on increasing land sales in La Ribera as a part of a more general trend in the East Cape (Los Barriles to San José del Cabo).Footnote5 Customers tend to be mostly foreign retirees with economic leverage, who buy properties from large land developers at prices in the 1- to 3-million dollar range. (USD).

The extensive use of scarce resources is for some members of La Ribera community a lesser evil, insofar as although golf courses demand large amounts of water, they are perceived as beneficial as become a major attraction for tourists and high-income investors. Second homes mean spill-overs through house maintenance and service payments, especially when their owners decide to move in and integrate with local communities. However, as Mr. Soto highlighted that mega-cruise tourism ‘leaves nothing behind, nothing’.

Mrs. Gloria Chávez,Footnote6 a former sales manager for Hotel Los Arcos (in La Paz, the state capital), who is originally from La Ribera, offers a more critical view of tourism in that region. Her parents were engaged in agriculture and livestock activities; she studied basic education in her community, but left to settle in La Paz. She used to visit her parents repeatedly when they were alive; nowadays, she limits her travelling to La Ribera to 3 or 4 times a year because she keeps property and has a friend in that community. With more than a 20-year experience in the tourism business, her main concern regarding the arrival of the Costa Palmas East Cape project to La Ribera is the ‘great secrecy with which everything is done’. This is so, given that fewer people have access to the area where the beach used to be, and which has disappeared with the dragging works for the marina. It was there where their parents used to take her and her siblings on summer weekends during their childhood. She mentioned that all those lands were ejido property, later to be sold to large investors.

Other major concerns of hers regard water, security and other services. From her childhood in La Ribera, she remembers struggles over water availability and the community’s vulnerability to climate shocks during hurricane seasons, as heavy rains usually left the community in isolation for days. In the same way, she stated that megaprojects such as Costa Palmas East Cape project ‘will not generate as many benefits to the local community as many believe’. The arrival of foreigners is overwhelming, she says, and fears La Ribera will mimic other neighbouring communities such as Los Barriles and Buena Vista, where ‘when you walk on the streets the local population is scarce’. Finally, she says ‘that we are all equal’ and that economic profits should not overpower the common good or the environment, so people should be more aware and informed about the pros and cons of ‘this type of megaprojects’.

The above-mentioned reflections were confirmed by 20 semi-structured interviews wherein we sought to obtain from members of the La Rivera community their opinions on the positive and negative effects of tourism, which were conducted on June 8th and 9th, 2019. Respondents highlighted a number of positive aspects from the development of Costa Palma, such as the arrival of chain stores, better paid jobs, the opportunity to earn money selling and/or placing their properties for rent, as well as better telecommunication services. Among the negative aspects, they mentioned water shortages, wastewater spills, more expensive medical services and basic goods, the arrival of an alien population, insecurity, and an increase in land prices. The Costa Palmas project, according to what some respondents told us, had made a commitment not to use water from the aquifer and to building its own sewerage treatment plant. However, since it was established, it has always been connected to the municipal water and sewerage service.

6. Concluding remarks

The main focus of this paper has been to critically assess how tourism growth in Los Cabos affects land and water use. One main result is that the patterns of water consumption in tourism resorts in Los Cabos reveal severe inequities. The operation costs of the desalinisation plant are three times higher than those of the municipal system of aquifer extraction; an overprice the municipal government absorbs. In other terms, the municipal government subsidises tourism water consumption, which is mainly supplied by the aquifer extracting system. This model of water distribution reflects a gradual process of accumulation by dispossession of water.

Land use follows the same pattern, as the government buys ejido land for urban growth, which it later sells under market prices. As more remote shanty towns become regularised and social housing is built away from the coastline (acquiring land there is unaffordable to most of Los Cabos inhabitants), pressure increases on the government to provide sound public services. This becomes another way of subsidising tourism growth: tourism pulls labour into Los Cabos (and Baja California Sur), but that economic sector is not accountable for the subsequent costs of housing, education, health or security services for those workers, to mention but some services. At the same time, a social divide emerges as tourist and high-end residential zones are clearly separated from the rest of the city, and are located in the best places in terms of access to the beach, landscape, and services. This situation resembles experiences in other parts of Mexico, such as Cancun, but also in other countries, as in the case of the Balearic Islands, in Spain. The Mexican seaside tourism model is not new, but balearisation has been developed here to its full potential.

David Harvey’s concept of accumulation by dispossession is a capacious idea, meant to address many of the main characteristics of neoliberal capitalism. As discussed in the text, it is capable of providing important insights into such phenomena as how and why the historical processes in Los Cabos and other spaces that have undergone touristification show the emergence of a range of related manifestations: the disappearance of traditional economic activities and the displacement of the local population, the promotion of immigration from other, generally less well-off areas for the provision of cheap labour, and the appropriation of land and other valuable resources by extraneous (national or foreign) enterprises that reap the majority of the benefits of tourism in the form of profits and, increasingly, economic rents.

In our globalised times, tourism can be seen as a prime example of Harvey’s accumulation by dispossession. As it was argued in the main text, Los Cabos was created as a touristic space by governmental fiat, and then handed over to private interests, again largely foreign, in the 1970s. From a sleepy fishermen’s village up to the 1980s, Los Cabos has grown to be Baja California Sur’s main population centre, having overtaken the state capital, La Paz, a few years back. The growth of Los Cabos is explained almost completely by the growth of tourism, which has advanced through a constant process of production of tourist space.

As a result, coastal land has been increasingly taken over by tourism, an activity that, as argued in the text, has long abandoned its urban origins in the towns of Cabo San Lucas and San Jose del Cabo and is now rapidly laying the foundations of an expanded, even more exclusive, tourism destination, far from the towns’ madding crowds, poverty and squalor. Tourism has also appropriated nearly half the urban water available, while the lower-income population – the great majority in the above-mentioned towns – faces severe shortages. Although, overall, the Los Cabos’ economy performs above the national average, the distribution of added value is markedly skewed in favour of profits, and the population at large endures high or very high levels of marginalisation.

Through land-grabbing, tourism has expanded from the original early 1990s highly urbanised areas of San José del Cabo and Cabo San Lucas mainly towards the ‘East Cape’ region but also northwards. Taking a leaf from the writings of the Spanish Balearisation group of political ecologists, we underscore the important implications of these issues for the region’s human/environment system and social well-being. Such imbalances in land use have led to a cross-sectoral dispute for water that is diverted towards agricultural products demanded by the international market and the displacement of putative profitable activities in terms of water consumption. Given water scarcity in the region, sowing in the desert sounds anecdotal.

As Elisabeth Rosenthal of the New York Times (2011) pointed out, this translates as the appropriation and economic accumulation of scarce natural resources (land and water) that are susceptible of being exploited for the purpose of generating profits by satisfying the desires of a faraway society. Finally, the several interviews that we conducted in support of this research produced a mixed bag of results: while estate agents and some locals approve the touristification of the La Ribera region due to the economic benefits it represents to them, there is also strong disagreement from some long-time residents fearful of losing their space and traditions.

More research is needed to clearly articulate spaces to debate and to reach at least a minimal consensus onto the extent and impacts that this luxurious-exclusive type of tourism, brings about in Los Cabos. Land(scape) and natural resources use has relevant impacts on the likely continuation of economic activities themselves, and also on the form of society that is being pursued. Recognising extractive frontiers and dealing with the unequal appropriation effects they entail are necessary if the so much advocated notions of development and human rights are to be fulfilled.

Acknowledgments

The paper was partly funded Mexico’s National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT), Research Project: Turismo y producción del espacio urbano: consecuencias para ciudades periféricas en el contexto de la restructuración global del Siglo XXI, CB-2014-100000000242545.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. During field research INEGI’s interviewers mentioned that people distrust the use of information.

2. Agriculture is an important user of land and water in the municipality. Los Cabos municipality has an area of 3,070 hectares (ha) with agricultural potential. Its irrigation surface covers 2.876 ha: 29% is equipped with pressurized water systems and, in the remaining 71%, irrigation is performed by gravity. Los Cabos represents only 5.1% of the state’s agricultural area, however, it is the main producer and exporter of organic products, consisting of 21 varieties of spices and vegetables, all destined for the U.S. market. The most important agricultural areas are San Jose del Cabo, Miraflores, Santiago and La Ribera (Graciano, 2013). Local produce is highly demanded in California, Florida, and New York, so that Los Cabos engages in what is commonly regarded as virtual water commerce.

3. Ejido is the traditional form of communal land holding in Mexico. Under the 1917 Mexican Constitution, the sale of ejido land was prohibited by law. It has been allowed since 1993, and millions of hectares have fallen into private hands, displacing millions of peasants who migrated to the cities in search of jobs. The low sale prices of land have been a huge subsidy to the tourism sector, and the process is ongoing. Also, large amounts of land were acquired by politicians while in office and, once in the hands of their heirs, much of it has also been converted to tourism use (Bojórquez & Ángeles, Citation2014).

4. Estimated calculation at a rate of 350 litters per inhabitant per day.

5. Personal communication with real estate agent Mr. Luis Enrique Soto, La Paz, BCS, 1 February 2019.

6. Personal communication with Mrs. Gloria Chávez, La Paz, BCS, 2 February 2019.

References

- Anderson, R. (2017). Roads, value, and dispossession in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Economic Anthropology, 4(1), 7–21.

- Angeles, M., Gámez, A.E., & Ivanova, A. (2009). On the impact of tourism on the economy of Baja California Sur, Mexico: A SAM approach. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, Sustainable Development and Planning IV, 2, 783–790.

- Artigues, A. (2001). Turismo de espacios litorales e insulares. In D. Barrado & J. Calabuig (Eds.), Geografía mundial del turismo (pp. 91–122). Madrid: Síntesis.

- Barkin, D., (Coord.). (2006). La gestión del agua urbana en México: Retos, debates y bienestar. México: Universidad de Guadalajara.

- Blázquez, M., Murray, I., & Artigues, A.A. (2011). La balearización global. El capital turístico en la minoración e instrumentación del Estado. Investigaciones Turísticas, 2(julio–diciembre), 1–28.

- Bojórquez, J. (2014). Evolución y planeación urbana en la ciudad turística de Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur (México). PASOS. Revista De Turismo Y Patrimonio Cultural, 12(2), 341–356.

- Bojórquez, J., & Ángeles, M. (2014). Expansión turística y acumulación por desposesión: El caso de Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur (México). Cuadernos De Geografía, Revista Colombiana de Geografía, 23(2), 179–202.

- Bojórquez, J., Ángeles, M., & Gámez, A.E. (2019). El Derecho a la Ciudad y rescate del espacio público en zonas urbanas turistizadas. Una reflexión para Los Cabos, Baja California Sur (México). Aposta. Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 80(January–March), 109–128.

- Brenner, L., & Aguila, A.G. (2002). Luxury tourism and regional development in Mexico. The Professional Geographer, 54(4), 500–520.

- Brenner, N. (Ed.). (2014). Implosion/explosion. Towards a study of planetary urbanization. Berlin: Jovis Verlag.

- Brenner, R. (2004). What is, and what is not, imperialism? Historical Materialism, 14(4), 3–67.

- Cañada, E. (2010). Turismo en Centroamérica, nuevo escenario de conflicto social. Informes en Contraste. Managua: Alba Sud.

- Castree, N. (2008). Neoliberalising nature: The logics of deregulation and reregulation. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(1), 131–152.

- Cornelisson, S. (2011). Regulation theory and its evolution and limitations in tourism studies. In J. Mosedale (Ed.), Political economy of tourism. London: Routledge.

- Das, R.J. (2017). David Harvey’s theory of accumulation by dispossession: A marxist critique. World Review of Political Economy, 8(4), 590–596.

- Escobar, A. (2012). Más allá del desarrollo: Postdesarrollo y transiciones hacia el pluriverso. Revista De Antropología Social, 21, 23–62.

- Fine, B. (2004). Debating the new imperialism. Historical Materialism, 14(4), 241–278.

- FONATUR. Fondo Nacional de Fomento al Turismo. 2019. Destinos Turísticos de FONATUR. México: FONATUR. Retrieved from https://www.gob.mx/fonatur/acciones-y-programas/destinos-fonatur

- Frederiksen, T., & Himley, M. (2019). Tactics of dispossession: Access, power, and subjectivity at the extractive frontier. Trans Inst Br Geogr., 1–15. doi:10.1111/tran.12329

- Gámez, A.E. (1993). Desarrollo y perspectivas del polo turístico de Los Cabos, BSc dissertation in Economics, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur. La Paz, BCS, México: UABCS.

- Gámez, A.E. (2008). Turismo y sustentabilidad en Cabo Pulmo. México: SDSU.

- Gobierno del Estado de Baja California Sur. (2017). Los Cabos Información Estratégica 2017. Dirección de Informática y Estadística, Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico, Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Retrieved from http://sdemarn.bcs.gob.mx/docs/2017/ESTRATEGICOLOSCABOS2017.pdf

- Google. (2019). Map of La Rivera, México timelapse 2003–2018. Retrieved from Google Earth Pro. kh.google.com

- Gormsen, E. (1997). The impact of tourism on coastal areas. GeoJournal, 42(1), 39–54.

- Graciano, J.C. (2018). Uso, manejo y apropiación del agua en destinos turísticos. El caso del municipio de La Paz, Baja California Sur. Ph.D. dissertation in Social Sciences: Sustainable Development and Globalisation, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur. La Paz. UABCS, BCS, México.

- Gudynas, E. (2015). Colonialismo “simpático” y las contradicciones de nuestros progresismos. Rebelión, 19 de noviembre. Retrieved from http://www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=205790

- Harvey, D. (2003). The new imperialism. Great Britain: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, D. (2004). The ‘New’ imperialism: Accumulation by dispossession. The Socialist Register, 4. Retrieved from https://socialistregister.com/index.php/srv/article/view/5811/2707

- Harvey, D. (2016). The ways of the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Healy, N., & Jamal, T. (2017). Enclave tourism. In Ed. (L.L. Lowry.), The SAGE international encyclopedia of travel and tourism. doi:10.4135/9781483368924.n160.

- Hiernaux-Nicolas, D. (2005). La Promoción Inmobiliaria y el Turismo Residencial: El Caso Mexicano. Scripta Nova Revista Electrónica De Geografía Y Ciencias Sociales, 9(194), 1–15.

- IMPLAN Los Cabos. (2013). Segunda actualización del Plan de Desarrollo Urbano de San José del Cabo y Cabo San Lucas, B.C.S. (PDU 2040). San José del Cabo: INPLAN Los Cabos. Retrieved from https://implanloscabos.mx/pdu-2040/

- INE. Instituto Nacional de Estadística de España. (2015). Cifras oficiales de población resultantes de la revisión del padrón municipal a 1 de enero de 2015. Retrieved from https://www.ine.es/

- INEGI. Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística. (2014). Censo económico 2014. INEGI. Aguascalientes: INEGI.

- Krippendorf, J. (1982). Towards new tourism policies: The importance of environmental and sociocultural factors. Tourism Management, 3(3), September, 135–148.

- Lefebvre, H. (1976). Espacio y política, el derecho a la ciudad II. Barcelona: Península.

- Lefebvre, H. (2014). Toward an architecture of enjoyment. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

- López Guevara, V.M. (2011). La reorientación del ciclo de vida del área turística. El caso de Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca (México). Investigaciones Turísticas, 1, 107–121.

- López Noguero, F. (2002). El análisis de contenido como método de investigación. XXI, Revista De Educación, 4, 167–179.

- López-López, A., Cukier, J., & Sánchez-Crispín, Á. (2006). Segregation of tourist space in Los Cabos, Mexico. Tourism Geographies, 8(4), 359–379.

- Martínez, A.H. (2011). Derecho al Agua, Derecho a la Ciudad: La Privatización del Agua en la Ciudad de México. Revista Latinoamericana De Estudiantes En Geografía, 2, 39–48. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/releg140/docs/releg_v5__1_

- Marx, K. (1976). Capital, Volume I. London: Penguin Classics.

- Masse Magana, M.V., & Guzmán Hernandez, C. (2015). The state and the touristic megaprojects: The case of Cabo Pulmo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Teoría Y Praxis, 11(18), 101–129.

- More, T. (2016). Utopia. London: Verso.

- Mosedale, J. (2016). Neoliberalism and the political economy of tourism. Projects, discourses and practices. In J. Mosedale (Ed.), Neoliberalism and the Political Economy of Tourism. London: Ashgate.

- Murray, I. (2015). Capitalismo y turismo en España. Del ‘milagro económico’ a la ‘gran crisis’. Barcelona: Alba Sud.

- Niparajá. (2011). Alcances del proyecto y aspectos de biodiversidad. Campaña de Orgullo para la Conservación de los Recursos Naturales de La Ribera, La Paz, BCS: Author.

- Palafox, A. (2017). Turismo e imperialismo ecológico: El capital y su dinámica de expansión. Prefacio para su análisis. Ecología Política. Cuadernos de Debate Internacional, January 9th. Retrieved from http://www.ecologiapolitica.info/?p=6717

- Parker, S. (2015). Urban Theory and the Urban Experience. Encountering the City. London: Routledge.

- Reyez, J. (2016). Privatizan tramo de Carretera Transpeninsular en Los Cabos, Contralínea, enero 19. Retrieved from https://www.contralinea.com.mx/archivo-revista/2016/01/19/privatizan-tramo-de-carretera-transpeninsular-en-los-cabos/

- SDPnoticias. (2019). Ordenan suspensión provisional de mega proyecto turístico en La Ribera, SDPnoticias. com, January 9th. Retrieved from https://www.sdpnoticias.com/local/baja-california-sur/2019/01/09/ordenan-suspension-provisional-de-mega-proyecto-turistico-en-la-ribera

- SECTUR. Secretaría de Turismo. (2014). Agenda de Competitividad del Destino Turístico de Los Cabos, Agenda de Competitividad de Destinos Turísticos en México. México: FONATUR-UABCS.

- Spirou, C. (2011). Urban tourism and urban change. Cities in a global economy. New York: Routledge.

- Torres, R.M. (2005). Gringolandia. The construction of a new tourist space in Mexico. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 95(2), 314–335.

- Troyo, E., Mercado, M.G., Cruz Falcón, A., Nieto, G.A., Valdez, C.R., García, H.J., & Murillo, A.B. (2013). Análisis de la sequía y desertificación mediante índices de aridez y estimación de la brecha hídrica en Baja California Sur, noroeste de México. Investigaciones Geográficas, 85, 66–81.

- UNWTO. World Tourism Organization. (2017). Why tourism matters, July. Retrieved from http://www2.unwto.org/content/why-tourism

- Vives Miro, S. (2011). Producing a “Successful City”: Neoliberal urbanism and gentrification in the tourist city – The case of Palma (Majorca). Urban Studies Research, 2011. Article ID 989676. doi: 10.1155/2011/989676.

- Voicu, M.C. (2011). Using the snowball method in marketing research on hidden populations. Challenges of the Knowledge Society, 1, 1341–1351.

- World Travel and Tourism Council. 2018. Travel and tourism economic impact 2018. London: WTTC. Retrieved from https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/regions-2018/world2018.pdf

Appendix A.

Interview items. La Ribera inhabitants’ perceptions about tourism effects on the community

Age (in completed years):

Sex: M__ F__

Schooling (in years):

Occupation:

Years of residence in La Ribera: _________

1. Are you involved in any tourism-related activity? Is so, please explain

2. Do you own, lease or rent the place you live in? Do you share a house?

3. Do you think that the price of land and housing has increased? Has income?

4. In recent years, have you had trouble accessing public spaces such as beaches?

5. How do you perceive your community in terms of security?

6. How do you perceive your community in terms of employment?

7. How do you perceive your community regarding medical services?

8. In recent months, have you had water shortages?

9. In recent months, have you had drainage problems?

10. What do you think are the main problems your community?

11. Do you think water is a problem in your community?

12. What economic activities make more use of water and land?

13. How do you think tourism has impacted your locality?