ABSTRACT

Although Brazilian Quilombolas possess specific land rights referring to their past as African slaves, the realization of such rights often fails due to the absence of land surveys, clarified institutional competencies and the general lack of power under which minorities suffer. Additional factors such as an expanding commercial agriculture contributing to land and water degradation and new actors introducing new logics intransparent to traditional populations often aggravate the situation. In order to identify options for traditional populations to overcome a development-deadlock typical for peripheral regions, the case of a Quilombo in Pará/Brazil will be analysed that has been struggling since decades with conflicting land tenure legislations and institutions. Starting from an inter- and transdisciplinary qualitative research process, scenario building by backcasting can represent an innovative approach to organize the central conflicts which have to be solved in order to overcome the development deadlock of the Quilombo Vila Formosa in Pará.

Introduction

Amazonian land conflicts are often conceptualized as legally overlapping, historically derived problems (Benatti & Fischer, Citation2017; Benatti Citation2018). In this specific case study, the Quilombo of Vila Formosa in Alto Acará, accumulating land tenure and social conflicts have resulted in a complex situation that is difficult to unravel. Although Brazilian QuilombolasFootnote1 possess specific land rights referring to their Afro-Brazilian legacy, the realization of such rights often fails due to the absence of land surveys, maps and land titles, respectively, clarified institutional competencies and the general lack of power under which minorities suffer. In peripheral regions like Acará where understaffed and underfinanced institutionsFootnote2 struggle to implement public policies, commercial agriculture often aggravates the situation, e.g., by engaging in land-grabbing (Borras et al., Citation2010; Edelman, Citation2013; Schönenberg, Citation2019) for monocultures and thereby contributing to land and water degradation (Moreira da Silva & Navegantes Alves, Citation2017). At the same time, the arrival of new agricultural activities, new civil society actors and the introduction of new concepts and rules such as CAR,Footnote3 REDD+Footnote4 and ISO-standardsFootnote5 introduce new decision-making logics, intransparent to traditional populations. The thereby created ‘development-deadlock’ describes a vicious cycle of hurdles such as the lack of public services, institutional weakness of land regulation administrations, lack of adequate credit lines, land-grabbing, corruption and organized crime, limited access to markets, bad infrastructure difficult to be dissolved.

The theoretical characterization of land occupation as frontier (Coy & Klingler, Citation2014; Martins, Citation1997; Turner, Citation1893) and post-frontier (Klingler, Citation2017; and Klingler & Mack in this volume) is a fuzzy but adequate approach to get hold of the rather volatile conditions of peripheral regions. Defining access as ‘the ability to derive benefits from things’ (Ribot & Peluso, Citation2009) will help to systematically answer the question who can use which resources under frontier conditions, in this case, in Acará/Pará/Brazil. Based on the assumption that global change may impact negatively in many ways at the same time on the same location, additionally, the syndrome approach (Lüdeke et al., Citation2004) will help to contextualize the field data of the informal Quilombo at the frontier-region Vila Formosa in Alto Acará in the global context.

The aim of this paper is the identification of a potential development-path for traditional populations caught in between fading customary law and incomplete legal formalization of land tenure, in this case in rural Amazonia (Benatti Citation2018; Benatti & Fischer, Citation2017), and to thereby contribute to the understanding of further frontier regions with comparable conditions elsewhere in the Global South.

In this LUS-volume we discuss the possible contributions of social sciences to land use sciences that are frequently being approached to deliver policy recommendations and thereby contribute to land use planning processes, especially in the Global South. We presuppose that quantitative, natural science based land use sciences can greatly profit from detailed and process-oriented qualitative data social sciences collect and analyse, for example, as basis for writing substantial storylines. At the same time, social sciences can learn a lot from natural sciences on the materiality of their study subjects and can benefit from systematic methodologies such as backcasting that starts from the desired scenario in the future. It is a methodology that combines well with social sciences’ use of qualitative research methods such as narrative interviews, workshops, participatory observation and focus groups, all enabling the understanding of the texture of societal relations that characterizes the original conflict, however, often without being able to characterize neither its material features nor its quantitative dimensions. When it comes to the integration of qualitative and quantitative data (Holton & Walsh, Citation2016), the challenge is huge and tailor-made solutions are common: for example, applied in joint scenario-building, where the fusion of qualitative and quantitative approaches can result in interdisciplinary added value (Schönenberg et al., Citation2017).

The aim of this article is twofold:

First and foremost, to unravel the development-deadlock of the Quilombo Vila Formosa in Alto Acará/Brazil and to identify pathways on how it could be overcome;

Additionally, I want to show how profound knowledge of societal processes can contribute to future scenarios and policy recommendations demonstrating the value of inter- and transdisciplinarity.

The paper will start with a historical reflection of land occupation in the research region, and then, specific historic and legal background of the Quilombos in Brazil. After giving the reader this overview on the legal framework and the location, the theoretical approaches and the empirical background will be introduced and the basics on present-day Acará will be outlined. Since backcasting is the chosen methodology to unravel the desperate situation in the research region, it will first be explained and then, in the results, it will be implemented based on the qualitative data collected in Acará. In the discussion, the hypothetical results of the exercise will be debated, although the necessary participatory process on the ground is yet to come. The conclusions critically reflects on possible contributions of inter- and transdisciplinary science towards conflict resolution.

Historical reflection of land occupation in the research region

The historic contextualization of current land conflicts in the Global South almost always leads to the confrontation with the colonial legacy (Schönenberg, Citation2011; Simmons, Citation2005) which often persists due to the colonial foundations of current land law. Also, in the case of Acará, the underlying history shapes the present noticeably. Prior to the Portuguese occupation during the 17th century via the Acará River, the region of Acará was presumably occupied by Turiwará and Tembé (today TI Tembé), unfortunately, a period of weak documentation. In the 16th and 17th century, the Portuguese crown distributed land rights, so-called sesmarias (1530–1822) and capitanias. While the latter gave origin to the state-structure of the federal Brazilian state, the former became the base for economic valorization during the colonial period and often substantiate even current land claims (Treccani, Citation2001). After the Portuguese Governor Pombal forced the Jesuits to leave the country in 1755, many localities received a formal status to reaffirm the outreach of the colonial state, so too, in 1758 the settlement Acará became a parish. In 1820 the Capitania Pará had 37 municipalities with 80.000 inhabitants, of this 25.000 living in Belém; in 1850 the first ‘land law’ was proclaimed that defined land as property that could be bought or being donated by the King and which had to be cultivated to keep it (Schönenberg, Citation2011, pp. 27–100). In the beginning of the rubber-boom, 1876, Acará was renamed São José de Acará. Triggered by the invention of vulcanizationFootnote6 and the beginning tire-production, the local rubber extraction took off in the Amazon and new national and international actors claimed land rights to secure their profits and bring the local, family-based rubber production under their control.Footnote7 After the decay of the rubber-boom in the early 1920’s, Acará fell back to family-based agriculture and began to specialize in manioc-flour production. In 1932, two years after the so-called revolution of 1930Footnote8, Acará lost its autonomy becoming a part of Belém. Only three years later, Acará regained an autonomous status and in 1959 became the Municipality of Acará.Footnote9 As in all Brazilian hinterlands, a constant process of administrative and political sub-divisions of too large municipalities hampered consistent institution-building on a local level. During the 1970’s, the Brazilian military dictatorship proclaimed the doctrine of ‘integrar para não entregar’ and ‘terra sem homens para homens sem terras’,Footnote10 a kind of state-imposed migration (geo-)policy established for Amazonia (Becker, Citation2005). The respective National Integration Program (PIN) was a geopolitical program created by the Brazilian military government through Decree-Law No. 1106 of 16 July 1970, signed by President Médici. The proposal was based on the use of north-eastern labour released by the great droughts of 1969 and 1970 and the notion of Amazonian demographic emptiness. This doctrine impacted heavily on Amazonian life initiating large infrastructure programs triggering migration from the Northeast and South. Additionally, the integration policy led to the duplication of federal and local state institutions, amongst others claiming the right to regulate land tenureship. It is since the implementation of the National Integration Plans (PINs) during the 1970 s that about 70% of the Legal AmazonFootnote11 is under federal jurisdiction. Only after recognizing the legal history of land occupation, current blockades become comprehensible. Summing up, currently, one has to consider four layers of possible land claims:

Customary law, claimed by Indigenous people, Quilombolas, early settlers, so-called Caboclos, with different legal recognition;

Colonial law, claimed on the basis of sesmarias that have been sold, bought and faked over the centuries, a process being documented in private notary’s offices,

State law: Land titles registered by the Land Institute of the State of Pará (ITERPA)Footnote12

Federal law: Land titles registered by the Federal Administrations such as INCRA,Footnote13 for land and agrarian reform, FUNAIFootnote14 for indigenous lands, Palmares Foundation for Quilombo land and the environmental institute IBAMA/ICiMBioFootnote15 for all further environmental delimitations.

Those political-administrative fragmentations led to a complex dynamic of undefined competencies and endless political struggles for rights and responsibilities to plan and decide on land use (Benatti & Fischer, Citation2017; Schönenberg, Citation2011). Keeping in mind those layers is vital to understand the current conflicts in Acará.

Historic and legal background of Quilombos in Brazil

Brazilian Quilombola communities had their origin between the 16th and 19th century, when slaves either fled from farms in the Brazilian hinterlands or, after the abolition of slavery in 1888, when there were no policies to take responsibility for the new citizens, many Afro-Brazilians continued to work as small subsistence farmers in the region where they were enslaved before (Dalosto et al., Citation2019) – the latter being the case in Acará. One hundred years after the formal abolition of slavery, the property rights for the lands occupied by the remaining Quilombolas was recognized in the Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988. Accordingly, the Palmares Cultural Foundation (FCP) was created with the aim of preserving the cultural, social and economic values of descendants of Quilombolas (BRASIL, Law 7.668, 1988). Despite the improvements guaranteed by the 1988 Constitution such as special land rights, it is only in 2003 that the land rights of the Quilombolas were effectively regulated by Decree 4.887 of 20 November 2003. Meanwhile, data from the Palmares Cultural FoundationFootnote16 officially indicate the existence of 2,648 Quilombos; 30 years after the adoption of the constitutional right to Quilombola-land, only about 30 communities received the title of their communal lands. Following this slow rhythm of titling, it would take more than 900 years to guarantee all the Quilombola communities their territorial rights. Why is that so? Hopefully the disentangling of the situation in Vila Formosa in Alto Acará can shed light on this issue, too.

Theoretical approaches

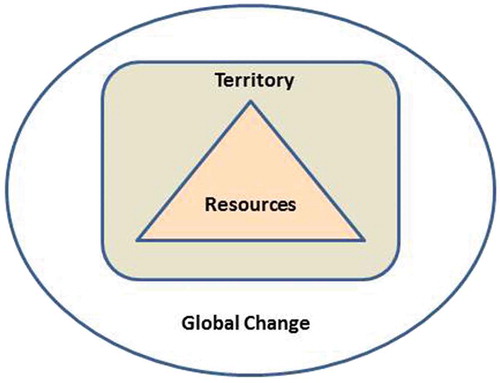

Talking about ‘rural peripheries’ in the Global South, we need to tackle three dimensions.

First, the territory, where the case-study takes place needs to be framed – here, I use the concept of frontier (Coy & Klingler, Citation2014; Fold & Hirsch, Citation2009; Martins Citation1997; Peluso & Lund, Citation2011;Turner, Citation1893) and refer to the very special societal conditions during the transition from informal to formal social structures (Schönenberg, Citation2019).

Second, the nature of the resources within that territory causing the conflicts need to be analysed – here, I use the access concept (Ribot & Peluso, Citation2009) that offers a comprehensive interpretative perspective on resource use conflicts.

Third, Global Change that structures the external conditions impacting on the single case have to be considered – here, I use the syndrome approach (Lüdeke et al., Citation2004) offering a typology for specific negative development-processes due to global change.

Since Frederick Turner’s (Citation1893) dichotomy between the wild and civilization to more recent processes of land occupation and resource appropriations (Martins 1996, Coy & Klingler, Citation2014), the concept of frontier has been discussed continuously. The characterization of land occupation and subsequent socialization as frontier or post-frontier (Klingler, Citation2017) deals with the volatile conditions of peripheral regions where access to land and natural resources is constantly contested. It is no longer a question of the conventional agricultural frontier, as a zone of transition between forests and agricultural land but of a ‘space of multifaceted development trajectories’ (Fold & Hirsch, Citation2009, p. 95) characterizing the current post-frontier debate (Peluso & Lund, Citation2011). Post-frontiers are spaces that are in one way or another connected to national, regional and global commodity flows, legal and cultural influences that for their part reshape frontier regions (Fold & Hirsch, Citation2009). Consequently, new actors enter and compete for land and natural resources. Regarding the Amazon, Geiger (Citation2008) emphasizes that we are currently witnessing the destruction of mainly informal property systems, political structures, social relations, and life-worlds to enable new cycles of resource extraction. This interpretation converges with the arguments of Peluso and Lund (Citation2011, p. 668) that ‘new frontiers of land control are being actively created’. Although internet-campaigns against predatory exploitation of natural resources during such processes are common place and environmental governance is mostly at least rudimentarily existent, the crude capitalist style of valorisation (Bunker, Citation1985) of peripheral regions respectively of new resources in old frontiers is still predominant and frequently accompanied by conflict and violence against nature and local populations. Reporting about his research in the Brazilian Amazon, Klingler (Citation2017) recently characterized the incorporation of multiple governance-instruments of land and natural resource-regulation as elements of a post-frontier accompanying the process of capitalist valorisation. Due to complex bureaucratic proceedings of resource governance it is much easier for capitalist companies to apply for licences or to comply with codes and legislations than for local populations. This applies also in the case of land-grabbing (Edelman, Citation2013) and is very well illustrated in our research region by the activities of the Biopalma CompanyFootnote17 and in the Quilombos of Acará, where the lack of efficient governance ever since post-colonial occupation led finally to administrative standstill and permissiveness in the face of the current oilpalm-front.

The ongoing reformulation of the local power relations and access-conditions to resources under frontier conditions, in this case, in Acará, suggest that it is more important to have at one’s disposal ‘a bundle of powers’ than a ‘bundle of rights’ (Ribot & Peluso, Citation2009, p. 154). A bundle of power includes a much wider range of social relationships guaranteeing access than property relations alone:

‘The categories we used to illustrate the kinds of power relations that can affect rights-based mechanisms of access were: access to technology, capital, markets, labour, knowledge, authority, identity, and social relations.’ (Ribot & Peluso, Citation2009, p. 173).

This insight was verified during field research in the Municipality of Acará as we found out that besides conceptualizing the land conflicts as legally overlapping, historically derived problems (Benatti Citation2003, Citation2015), understanding the access to power networks is vital to understand ongoing conflict dynamics and to finally identify possible solutions.

Based on the assumption that global change may impact negatively in many ways at the same time on the same location, the syndrome approach (Lüdeke et al., Citation2004) can help to contextualize the field data of the informal Quilombo at the frontier-region Vila Formosa in Alto Acará in the global picture. Global change is impacting on the remotest regions of our planet. Impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss, droughts or floods, soil degradation interact with spirals of impoverishment, violent conflicts, weak and corrupt or institutions, impunity and absent public policies. Following the syndrome approach, Vila Formosa is characterized by four out of seven syndromes of global change described by Lüdeke et al. (Citation2004).

All three approaches frame the problematic situation of the researched region from different angles: the territorial, the resources and the global perspective.

Empirical background

Within the framework of the BMBF/FONA consortium project CARBIOCIAL (2011–2016), many results were achieved which could not be disseminated during the project period.Footnote18 Accordingly, and with the objective to give back some of the results on land tenureship in the Brazilian Amazon that could not be passed on during the Carbiocial-period, the NoPa-Project, Footnote19 ‘Agrarian and Environmental Law on the Ground’Footnote20 was implemented as a pilot in the Municipality of Acará in 2016 to 2017. The aim of the project was to elaborate, test, improve and disseminate interactive teaching modules and understandable charts on Agrarian and Environmental LawFootnote21 for different land-user groups in rural Amazônia. During field-work in Acará, we strived for a profound understanding of the practical implications of the complexities and overlaps of agrarian and environmental law by initiating transdisciplinary exchange on their contradictions. We tried to process the local legal situations towards adequate teaching modules cross checking them with local research partners. For this, we applied workshop-formats in Acará City, Vila Formosa and Brasília, testing and improving those modules in different locations together with local partner institutionsFootnote22 that were interested. Finally, we handed over the didactic materials for local land users to those organizations who indicated that they are interested in the dissemination of our methodology, namely the local representation AMARQUALTA, to the state-run agricultural consultancy, EMATER and the local planning secretary, SEPLAN in Acará and the Federation of rural trade unions, FETAGRI in Belém. Involved actors were the Law Clinic of the Institute of Juridical Science (ISJ) at Federal University of Pará (UFPA), the Latin American Institute and the Institute for Geographical Sciences of Free University Berlin, the Law and Society Institute of Humboldt University Berlin, the Environmental Ministry in Brasília, GIZ-Brasília and four M.A.-students on the Brazilian and four M.A.-students on the German side, as well as governmental and non-governmental organisations of the Municipality of Acará/Pará and about 80 members of the AMARQUALTA in Vila Formosa in Alto Acará which became our testing-field for interviews and interactive workshops.

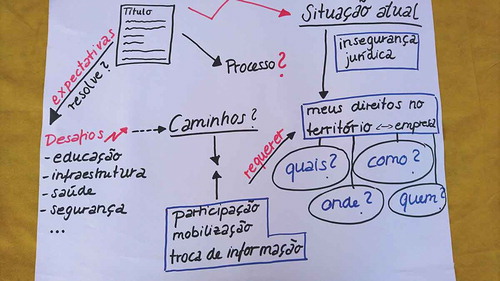

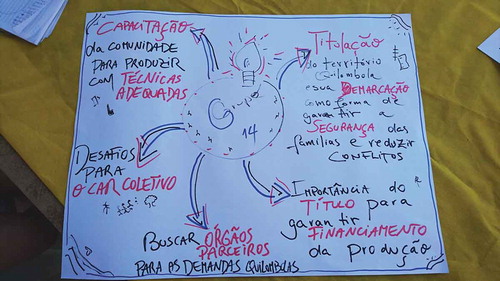

Two assumptions were made: First, that clarifying and securing land tenure rights is a cornerstone for improving environmental governance and the human rights situation in general; second, that the Brazilian government until the impeachment in 2016 had increased efforts to elaborate and implement legal instruments and laws (e.g., Terra legal e CARFootnote23) to enhance sustainable development in the Amazon region and to reduce environmental impacts from agricultural development and deforestation. All through the research process, we were confronted with the widespread attitude of local landholders of all categories that legal environmental constraints and agrarian legislation are intransparent, illegitimate, inadequate and hardly understandable. During our 1st workshop with AMARQUALTA in Vila Formosa in 2017 and also in most single conversations it was confirmed that concepts such as ‘law’ or ‘state’ are mostly seen as being an enemy by the people who have constructed self-made livelihoods in Amazonia. Sometimes, it was difficult to convince the participants to even discuss ‘law’ and in the end they apparently consented to do us a favour. And they were right: during the research-process they convinced us, the researchers, that more holistic approaches especially including access to clientelistic networks are more promising to secure local livelihoods than merely legalistic strategies.

Didactically, our teaching- modules should achieve two goals: first, to initiate the discussion on the history, role and function of law and thereby develop an empowered citizens’ perspective of its application; second, to convey solid knowledge on the legal situation and the organizational hierarchy as well as competencies of implementation agencies to landholders and responsible land and environmental agencies. The beneficiaries were small farmers and cattle ranchers and their respective institutional representatives, traditional populations and fishermen interested in widening their understanding of the topic.

During the one-year period in the field (from mid-2016 to mid-2017) several phases of qualitative research, employing narrative interviews, workshops, participatory observation, focus-group-discussions and one Research-into-use-Workshop with all research partnersFootnote24 and about 80 community members (2017) took place in the Municipality of Acará conducted by the above described interdisciplinary group of Brazilian and German social scientists and lawyers.Footnote25 The aim of the transdisciplinary action-research was to co-produce together with local stakeholders a common understanding of the potentials and limits knowledge of legal frameworks of land and environmental legislations and institutions might provide. This article focusses on the experiences we gained at one research site, the Quilombo Vila Formosa de Alto Acará where we understood that the opportunities tend to be sought beyond legally based solutions since after 10 years of approaching potentially competent institutions the involved stakeholders lost all hope in formal governance.

Basics on present-day Acará

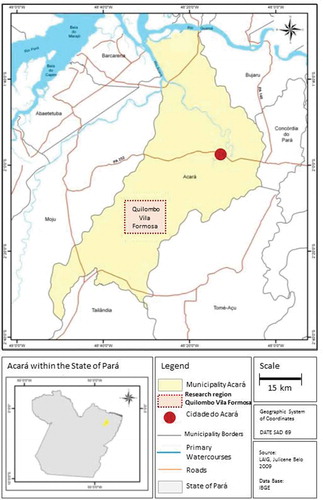

The current municipality of Acará with 4.343,80 km2, which represents 0.35% of the State of Pará, and about 55.000 inhabitants, is located in the northeast of the State of Pará (see ). With an area of 1,247,703 km2, Pará occupies almost 15% of the Brazilian territoryFootnote26; Pará has 7.5 million inhabitants, of which about 70% live in smaller and larger urban centres and about 30% in rural regions, whereas in the Municipality of Acará about 15.000 live in the City of Acará and about 40.000 in rural areas (see ). Approximately one third of the territory lacks a clear definition of ownership, including the City of Acará itself, which has hardly any well-defined municipal areasFootnote27 . Within the Municipality of Acará, Quilombola communities such as Jacarequara, Espírito Santo, Carananduba, Itancoã, Monte Alegre, São Pedro, Boa Vista, São Miguel, Santa Maria, Paraíso, Itaporama e Tapera are spread all over the territory. Answers to our frequently repeated question of how many Quilombos exist in Acará varied between 7 and 34 which give first evidence of unclear legal status and vague self-definitions. The researched Quilombo Vila Formosa in Alto Acará that we initially have chosen due to its conflictive characteristics did not make it to the official listing yet.

Table 1. Characteristics of the research region – the author, based on IBGE 2010, 2018 & http://acara.pa.gov.br/.

Traditionally, Acará lived off subsistence farming and the commercial production of manioc flour, mainly for Belém. Although, Belém with approx. 2 million inhabitants, the largest city in the Amazon region is situated only about 100 km away from Acará, life in Acará seems to have stopped a long time ago. The local administrative bodies are understaffed and under-financed, so that sometimes not even computers are available in public offices. Political violence is omnipresent, shops and restaurants pay protection money and the only business that is visibly flourishing is the drug businessFootnote28 . In the face of this insecure situation, all segments of society organize their interests in clientelistic networks referring to their ‘good contacts’ as conflict-resolution option and to a powerful person to represent their interests. Conflicts shaking the informal Quilombo Vila Formosa in the hinterlands of Acará are reflecting the situation in the City of Acará described above: interest-representation is being performed within clientelistic structures by two leaders of the local Amarqualta association, one living mostly in the City of Acará acting as an information and communication bottleneck for the local community, the second, a local priest of the Pentecostal church and a third newly elected representative who was shot in late 2018. The most visible organization of the approximately 112 families in Vila Formosa is a Pentecostal Church and the current speaker of the local association Amarqualta is the priest of that church. The wish of the local community is to survive ‘somehow’ planting manioc flour and subsistence products and to secure their land as basis for survival. However, the juridical situation is twisted and since its formation in 2009, Amarqualta is trying to legalize the situation of their approximately 1.200 associates, members of six communities by referring to quilombolas’ territorial rights: ‘The procedure to recognize quilombolas’ territorial rights is under the authority of the Federal and States governments. In the federal level the matter is disciplined by Federal Decree 4887/2003 and in the State of Pará, for example, the procedure is based on article 322 of the State Constitution, State Decree 261 of November 22/2011; State Law 6165/1998; and State Decree 2280/2010.’ (Fischer & da Cunha, Citation2013)

In this case, the institutional competencies for the primary delimitation of territory are divided between state and federal institutions, namely, ITERPA (land administration of the State of Pará) and INCRA (federal land administration) – two institutions that hardly cooperate with each otherFootnote29 . As part of an overall trend to transform farm land into palm oil monocultures, be it legally or illegally (Moreira da Silva & Navegantes Alves, Citation2017:3 + 7; Nahum & Santos, Citation2013, Citation2016), one third of the informally defined Quilombola-lands had been taken by the nearby Biopalma Company who referred to a falsified sesmarias-title that was finally localised in a notary’s office of the neighbouring municipality of Tomé AçúFootnote30 . Although the fraud was discovered, the lands are lost for the community since the company simply left the plantation without removing the oil palms and without accepting a cooperation-offer from the community. Currently, young men of the community formed an armed militia to avoid further land-grabbing activities.

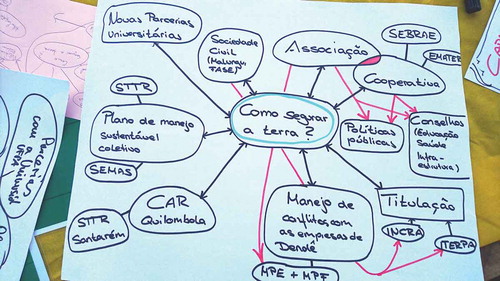

Analyzing the results of the conflictual working-groups in Vila Formosa it became obvious that there is no easy solution in sight; the historical reflection of the root causes and multi-dimensional impacts revealed that there is hardly any basis to project a positive future scenario. Even though, in Spring 2017, after field research weFootnote31 initiated a NoPa project-workshop in Brasília to discuss the situation together with representatives of Amarqualta and the Municipality of Acará with high ranking decision makers of the Environmental Ministry (MMA), the Chico Mendes Institute (ICiMBio), the Ministry of Agricultural Development (MDA), of INCRA and Terra Legal in order to exchange knowledge and to find a viable solution. After 6 hours without one glimpse of a solution we interrupted the exercise. In search of a methodology that might disentangle the situation retrospectively, I opted for ‘backcasting’.Footnote32

Backcasting

How could we, as scientists, encourage the pursuit of a sustainable development path in Vila Formosa, Municipality of Acará? To avoid the desolate present situation as a starting point for a basic storyline, I decided to make use of the backcasting-methodology.

First, some background on the topic of scenario-techniques as such: Although working with scenarios is wide spread and currently includes crisis management, communication of complex scientific models, stakeholder participation, a future-research methodology, a planning tool for businesses etc., the origins of the methodology date back to Plato’s description of the Ideal Republic and future-visions from Thomas More to George Orwell (Von Reibnitz, Citation1988). As a strategic planning tool, scenario techniques are at home in the military and have been employed by military strategists throughout history, generally in the form of war game simulations (Bradfield et al., Citation2005; Brown, Citation1968). Currently, scenario-building is often used in combination with modelling (Priess & Hauck, Citation2014), as a bridge between social sciences-fed story lines and models (Schönenberg et al., Citation2017) or for stakeholder participation (Welp et al., Citation2006). Backcasting as one of many scenario techniques means to start from the desired scenario in the future reconstructing the necessary decisions to be taken to get there back to the present day (Grêt-Regamey & Brunner, Citation2011).

Results

Assuming a twelve-year forecasting horizon (2018–2030), sustainable solutions for the problems of Vila Formosa in the Municipality of Acará have to be projected for the following 8 conflicting fields that weFootnote33 have identified during our one-year research process in the Municipality Acará and the Quilombo Vila Formosa:

Addressing intergenerational conflicts;

Identifying and prioritizing of an economic survival strategy overcoming precarious subsistence farming;

Building capacities for external interest representation;

Identifying adequate forms of socio-economic and political representations;

Developing long-lasting conflict resolution strategies regarding land grabbing and agricultural poisoning;

Identifying and prioritizing forms of legal land tenureship and corresponding environmental governance;

Clarifying governmental responsibilities and competencies regarding further public policies (health, education, mobility, market access, energy etc.);

Addressing problems of corruption, impunity and organized crime.

All these steps need to be tackled before any form of rational land use can become viable.

All conflicting fields would have to be worked through bottom-up as a transdisciplinary endeavour together with the local community; participatory external mediationFootnote34 would be required to reformulate and complement the above list from a local perspective. The fact that problems 2, 5, 6 and 8 correspond with the above mentioned syndromes of global change () highlight the fact that the dynamics of underdevelopment in the rural areas of Acará can also be understood as part of global transformation processes.

Table 2. Syndromes adapted from Lüdeke et al. (Citation2004).

The following academic exercise applying the backcasting-methodology in order to elaborate on a positive development path for the Quilombo Vila Formosa can serve as a discussion platform with local stakeholders.

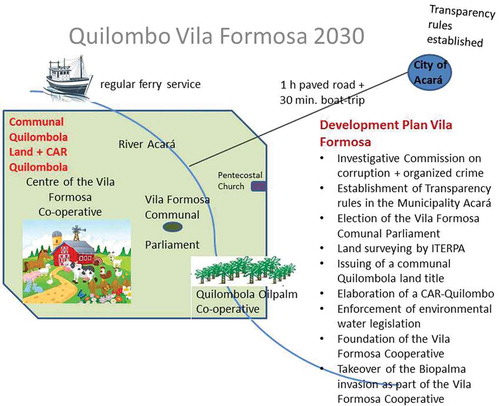

Quilombo Vila Formosa in 2030

In 2030 Vila Formosa is being governed by a communal parliament, which holds regular elections- There are always two presidents, one man and one woman representing the Quilombo at internal and external occasions. The active members of the communal parliament have undergone extensive capacity building to qualify for negotiations with more powerful actors outside their community. The same is true for the leaders of the Vila Formosa Cooperative which has been formed after successful negotiations with Biopalma Ltd. The illegal oilpalm plantation has passed into communal ownership and forms the economic backbone for the Vila Formosa cooperative. Meanwhile, further products, such as manioc-flour, pineapple, Açaí, cupuaçú and mamão have been taken into the commercial portfolio. The Vila Formosa women’s-group is engaged in local medicine, which is being commercialized, too. Both local businesses formed a partnership with the University Enterprise Centre of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), which is providing regular consultancies in economic, administrative and qualitative matters. Since the community became an important economic player in the hinterlands of Acará, the road to Acará City was paved, so that it now takes less than an hour to the city. Additionally, Acará has been connected to a regular ferry service linking Vila Formosa to the city of Acará and to Belém. The twisted land tenure situation was solved some years after the cooperative started to flourish. Community members finished University and manifold alliances were formed, with the UFPA/ICJ-Human Rights Clinic, among others. It was the access to power-resources that finally brought all involved institutions to one table. Federal INCRA ceded its responsibilities to state-based ITERPA who cooperated from the start with the Palmares Foundation to elaborate a solution that finally allowed for a communal Quilombola land title and the elaboration of an environmental cadastre, CAR-Quilombola. This also permitted to open up new credit lines by the Banco Amazônia. The Municipality of Acará has undergone some changes after some corrupt representatives were imprisoned. Now, a commission has been established to investigate corruption and organized crime. This has successfully established transparency rules for the Municipality.

This positive vision remains within the legal and political bounds of what is possible and describes a sustainable development path for Vila Formosa. Now, let us turn to the current situation and starting point for the route all involved would have to take in order to overcome the current developmental deadlock.

Vila Formosa in 2018

A former president of the Amarqualta Association, who is currently active in the city parliament of the Municipality, and hence, only sporadically present in Alto Acará dominates the political representation of Acará; the local Pentecostal priest took over as interim president. Meanwhile, the newly elected president was shot in 2018 under still unclear circumstances. The six communities are divided between Catholics and Pentecostal ProtestantsFootnote35 and between old and young (male) community membersFootnote36 who are fighting over the future of their community. The conflict with Biopalma Ltd., who appears to have stolen one third of communal land on the grounds of an outdated land title, led to the creation of an armed militia by young community members, which patrols at night. Due to the encirclement of communal lands by oilpalms the groundwater level has substantially dropped, so that the local manioc production stagnates and subsistence farming is becoming even more precarious. Because the Association Amarqualta could or would neither provide solutions for the water nor the land issues, a group of young community dissidents has formed a kind of anarchistic cooperative within the forest trying to survive without the, from their point of view, old-fashioned community-leadership. The land tenure questionFootnote37 is pending since 2009 when Amarqualta first asked for the inclusion to the Quilombola land programme. At that time, it was revealed that the administrative border between federal-INCRA (60 families) and state-ITERPA (52 families), the institutions responsible for the land surveying, runs in the midst of their lands. Only after those institutions finished their respective surveying work could the formal process of recognition as Quilombola land be initiated. Even after involving the law clinic of the Federal University of Pará and the Quilombola-NGO MALUNGO the competency-problem could not be solved, so that the initial situation remains unsettled.

Discussing the route from 2018 to 2030

The discussion points refer to the above outlined conflicting fields identified during the research process of the NOPA-project in 2016–2017Footnote38. Through the backcasting exercise the conflicting fields could be transformed into a positive vision – an exercise that can help to project step-by-step-solutions in all affected societal fields.

Community affairs

Intergenerational conflicts are currently obstructing common conflict resolution within the community. The situation is explosive since young men formed an armed militia to defend communal lands. The religious division of the community worsens the situation. To establish common grounds for the resolution of those and further conflicts, conflict mediation will be necessary: either a consensual person from the community or external mediation by an involved NGO such as MALUNGOFootnote39 or of the Human Rights Law Clinic of the Juridical Sciences Institute of the Federal University of Pará (ICJ/UFPA)Footnote40 needs to address those conflicts. The next step would be the identification of adequate forms of socio-economic and political representation within and of the communities. To pursue this goal the Quilombo Vila Formosa will have to form alliances with external actors, who can moderate the process on a long-term basis and guarantee access to capacity building for external interest representation.

Economic affairs

There are already plans to form an agricultural cooperative, however the economic basis and the respective knowhow is still lacking. The first step would be the identification and prioritization of a holistic and sustainable economic survival strategy. To reach this goal, a partnership with the Enterprise Centre of the Federal University in Belém, UFPA would be vital; here, the necessary capacity building regarding the management of cooperatives could be provided, too.

Political affairs

The keyword ‘forging alliances’ is particularly important for overcoming the politically driven problems of the Quilombo as part of the Acará municipality. This could take the form of a long-lasting strategy to resolve the conflict between the Quilombo and Biopalma Ltd. This should include mechanisms for the community to use the abandoned oil palm plantation on communal lands as economic engine for the newly formed cooperative, and to restrict further land grabbing and agricultural poisoning by Biopalma Ltd. in the future. Further, the representatives of the Quilombo need to press for the clarification of governmental responsibilities and competencies regarding further public policies (health, education, mobility, market access, energy etc.) needed in Vila Formosa. Also, problems of corruption, impunity and organized crime, which are endemic in Acará, have to be addressed together with e.g., the Ministério Público,Footnote41 the Human Rights Clinic of the Pará Federal University and further grass root organisations by pressing the municipal government. All those necessary activities are conditional on the achievement of internal unity.

Land tenure affairs

As field research was carried out in 2016/17, the identification, prioritization and implementation of legal land tenureship already appeared rather remote for the Quilombolas.Footnote42 Now, after the election of the new Brazilian President, Jair Bolsonaro, who is known for his critical stances on the implementation of the agrarian reform or the respect of minority rights,Footnote43 it seems more promising to tackle land tenure problems on a community-, economy- and state-based level than trying to legalize land tenure based on federal minority rights.

The two scenarios constructed above are in their details based on countless conversations during the research-process 2016/17, but it was only in the course of the backcasting methodology that possible solutions and viable future visions for the Quilombo Vila Formosa came into view.

Conclusions

The case study on the Quilombo Vila Formosa in Acará stands for many hinterlands of the Global South: weak institutions, corruption, organized crime and abandoned local populations exposed to ruthless agribusiness corporations taking advantage of the weakness of state governance. The syndromes which could be identified in Acará, being characterized by impoverished subsistence agriculture, without regular access to credits, infrastructure and markets; accompanied by land grabbing, agricultural toxicants and land concentration; manifesting in deforestation, overexploitation of soils and water by oilpalms and overfishing; leading to rural exodus to the City of Acará with no regular land tenure, precarious sewage systems, health problems, extortion, drug trafficking and corruption can also be found in many peripheries of the Global South.

The concomitant conflicts resulting from such a setting are exacerbated by inter-generational and representation conflicts, asymmetric power relations and the lack of access to urgently needed knowledge and finally constitute the framework for the development deadlock of Quilombo Vila Formosa.

Our action-research, which was directed towards conflict resolution through legal transparency, exposed that opting for conflict resolution through land titling and legal regulation of access to natural resources was not enough in a lawless peripheral region. Digging deep into societal dynamics of single locations helps understanding the complexity of protracted land conflicts for which short term technical measures are no solution. In these situations there are neither institutions nor political will to implement technical or legal solutions. On the contrary, sophisticated technical solutions favour new players who have access to formal proceedings and thereby engage in legalized land-grabbing at the post frontier, at the expenses of local populations, who have barely access to formal education and the knowledge necessary to understand and implement these solutions.

By classifying specific negative development-processes, for example, taking place in Acará, as part of global change phenomena, locally acquired knowledge on subtleties of conflictive land use practices can be acknowledged as element of an overarching process. Under frontier-conditions the access to land and natural resources is characterized by legal and institutional uncertainty and depends on social capital, access to power resources and negotiation skills.

Scientific reflection on land use conflicts in the framework of land use science as inter- and transdisciplinary endeavour can create methodological and analytical cross-fertilizations. This was illustrated in the case of the Quilombo Vila Formosa in Alto Acará (Pará/Brazil) by an interdisciplinary group of researchers with a transdisciplinary perspective. This article has shown that a bottom-up perspective combined with a mix of instruments for analysis may lead to more realistic recommendations regarding the regulation of land use conflicts than sticking to a legalistic perspective. In the spirit of ‘Science for Sustainable Development’ the integration of qualitative field research with the awareness of historic processes and a backcasting exercise was important to rethink and analyse the deadlock of Vila Formosa.Footnote44

The more interdisciplinary a research group works, the more diverse are the possibilities for combining research methods and approaches in order to obtain applicable solutions.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

This article belongs to the forthcoming Special Issue on “Transdisciplinary perspectives on current transformations at extractive and agrarian, frontiers in Latin America”, edited by Anne Cristina de la Vega-Leinert and Regine Schönenberg. The NoPa-project was funded by DAAD and GIZ.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. A Quilombola is an Afro-Brazilian resident of Quilombo settlements first established by escaped slaves in Brazil. Quilombolas are the Afro-Brazilian descendants of refugees from slave plantations that existed in Brazil until abolition in 1888, or of freed slaves who started subsistence agriculture after abolition, as it is the case in Acará.

2. All our interviewees from public administrations during field research in 2016/17 stressed their precarious situation regarding human and financial resources.

3. Cadastro Ambiental Rural – Environmental Rural Register.

4. Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.

5. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is an international standard-setting body composed of representatives from various national standards organizations. For the Amazon it is relevant because it sets sanitation standards for local products that are difficult to meet by local producers and thereby closes the access to local, national and global markets.

6. Invented 1839 by Charles Goodyear in the USA.

7. If we look at current land conflicts provoked by oil palm firms (Coomes & Barham, Citation1994) they resemble struggles between old and new elites some 150 years ago during the rubber boom (Santos, Citation1980) and can be instructive to understand ongoing processes of informal power-sharing.

8. Getúlio Vargas reigned Brazil from 1930-1945 insisting on a strong central state; he called his authoritarian rule and the revocation of political rights of the Brazilian states ‘revolution’.

9. See information on the history of the City of Acará: http://acara.pa.gov.br/.

10. ‘Integrate so as not to give up’ and ‘land without men for men without land’.

11. Amazônia Legal also known as Brazil’s Legal Amazon is the largest socio-geographic division in Brazil that encompasses all seven states of the North Region (Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima and Tocantins), as well as part of Mato Grosso in the Center-West Region and most of Maranhão in the Northeast Region. Amazônia Legal is a 5,016,136.3 km2 region with around 26 million inhabitants. The administrative unit was established by Federal Law No. 5.173/2 in 1966.

12. ITERPA – Instituto de Terras do Estado do Pará.

13. INCRA – Instituto Nacional de Colonisação e Reforma Agrária.

14. FUNAI – Fundação Nacional de Asuntos Indígenas.

15. IBAMA – Instituto Nacional de Meio Ambiente e Recursos Renováveis, ICiMBio – Instituto Chico Mendes de Biodiversidade.

16. Due to political conflicts the Palmares Foundation is currently offline – the site was accessed in April 2019 when the data was annoted.

17. The Biopalma Company belongs to the corporate family Vale S.A., one of the biggest mining companies of the world and as owner of Carajás the greatest tax payer and cultural sponsor of the State of Pará; further, the Vale S.A. is traditionally entangled with the most powerful political family of the State, the Barbalho-family, being Helder Barbalho the current Governor of Pará.

18. For details on the CARBIOCIAL-project see: http://www.uni-goettingen.de/de/211056.html.

19. NoPa: Novas Parcerias = new partnerships was a GIZ/DAAD-project line between 2014-2018.

20. See, project page on the NoPa-project: https://www.lai.fu-berlin.de/nopa/index.html.

21. As background for practitioners see complementary materials to this article: Attachment 1+2 in Portuguese.

22. STTR-Acará – the trade union of small peasants; the local representation of the respective Quilombo AMARQUALTA, EMATER-Acará – governmental agricultural consultancy, SEPLAN – local planning office, SEMA – local environmental office.

23. Terra Legal is a land titling programme that came into force in 2009 and used to be implemented together with an instrument called CAR – Cadastro Ambiental Rural = Rural Environmental Cadaster; both programmes are obsolete because the current Bolsonaro government closed the responsible agencies.

24. ADEPARÁ – Agência de Defesa Agropecuária do Pará, AMVIVI – Associação das Mulheres da Vila dos Vinagres, Associação Remanecentes Quilombola Acará, Banco do Brasil Acará, Conselho Nacional das Populações Extrativistas, EMATER – Empresa de Assitência Técnica e Extensão Rural, INCRA – Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária/Terra Legal, SEBRAE-Acará – Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas, Biopalma, ITERPA – Instituto das Terras do Pará, MALUNGO – Coordenação das Associações das Comunidades Remanecentes de Quilombo do Pará, CONAQ – Coordenação Nacional de Articulação das Comunidades Negras Rurais Quilombolas, MDA-Pará – Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário, SEMMA – Secretaría Municipal de Meio Ambiente-Acará, Secretaria Municipal de Agricultura de Prefeitura Municipal do Acará, Secretaria Municipal de Planejamento e Gestão de Prefeitura Municipal do Acará – see list in attachment.

25. See contact list attachment 1.

26. 1.247.689,5 km² (Pará) of 8.515.779 km² (Brazil) is 14,65%.

27. See website of the Municipality: https://acara.pa.gov.br/.

28. Almost all interview partners sooner or later refer to those phenomena – without being asked.

29. The competencies between the land institute of the State of Pará, ITERPA and the federal land institute INCRA are not well settled; additionally, they are normally under control of different political parties; both factors contribute to a mainly hostile and non-cooperative spirit among the two institutions.

30. This case of land-grabbing was reported by the Secretary of Planning/Município Acará, by the representative of EMATER (agrarian counselling), by the NGO MALUNGO and the inhabitants of Vila Formosa during the Workshop in August 2016.

31. GIZ-Brasília, the Institute of Juridical Sciences of Federal University Pará, Latin America Institute Berlin, Secretary of Planning of the Municipality Acará, Representative of the improvised co-operative of the Quilombo Vila Formosa Acará.

32. The selection of this method is to be understood as learning from natural science land use studies.

33. The NoPa-research team.

34. External mediation can be sought at the Ministério Público which can be translated with ‘public state attorneyship’.

35. As we were told during field research.

36. Besides the catering there was no visible involvement of women in community affairs; all discussions were male dominated, although women participated passively.

37. „Land tenure“ is the battle ground in Pará where about half of the lands are precariously regulated and in conflict (Benatti Citation2018; Schönenberg, Citation2011); in the year of the described field work, 71 people died in land conflicts in Brazil (Human Rights Watch, Citation2019).

38. See here background information on the programme: www.daad.de/der-daad/unsere-Aufgaben/entwicklungszusammenarbeit/foerderprogramme/hochschulen/infos/en/43835-german-brazilian-partnerships-in-sustainable-development/.

39. For background information on the NGO MALUNGO see: https://malungupara.wordpress.com/.

40. For background information on the Law Clinic see: http://www.cidh.ufpa.br/.

41. Public Prosecutor’s Office.

42. See the statistics of the Palmares Foundation above cited.

43. https://reporterbrasil.org.br/2019/01/governo-bolsonaro-suspende-reforma-agraria-por-tempo-indeterminado/, https://reporterbrasil.org.br/2019/01/governo-bolsonaro-volta-atras-e-cancela-suspensao-da-reforma-agraria/.

44. In the appendix you will find additionally the geo-data of the municipality, so that natural scientists get a better idea of it.

References

- Becker, B. (2005). Geopolítica na Amazônia., Estudos Avancados, 19(53).

- Benatti, J.H. (2018). Das Terras Tradicionalmente Ocupadas ao Reconhecimento da Diversidade Social e de Posse das Populações Tradicionais na Amazônia. In Propriedades em Transformação: Abordagens Multidisciplinares sobre a Propriedade no Brasil (pp. 195–216). Blucher. Open Access.https://doi.org/10.5151/9788580393279-10

- Benatti, J.H., & Fischer, L. (2017). New trends in land tenure and environmental regularisation laws in the Brazilian Amazon, May 2017. Regional Environmental Change18(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1162-0

- Benatti, J. (2003). Posse agroecológica e manejo florestal, Juruá Editora

- Benatti, J. (2015). Desafios para a Governanca de Terras num Território em Disputa: O caso do Estado do Pará, Belém, UFPA

- Borras, S.M., McMichael, P., & Scoones, I. (2010). The politics of biofuels, land and Agrarian change: Editors’ introduction. Journal of Peasant Studies, 37(4), 575–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2010.512448

- Bradfield, R., Wright, G., Burt, G., Cairns, G., & Van Der Heijden, K. (2005). The origins and evolution of scenario techniques in long range business planning. Futures, 37(8), 795–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2005.01.003

- Brown, S. (1968). Scenarios in systems analysis. In E.S. Quade & W.I. Boucher (Eds.), Systems analysis and policy planning: Applications in defence (pp. 298ff). American Elsevier Publishing Co.

- Bunker, S.G. (1985). Underdeveloping the Amazon. University of Illinois Press.

- Coomes, O.T., & Barham, B.L. (1994). The Amazon rubber boom: Labour control, resistance, and failed plantation development revisited. The Hispanic American Historical Review, 74(2), 231–257. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-74.2.231

- Coy, M., & Klingler, M. (2014). Pioneer fronts in transformation: The highway BR-163 and socio-environmental challenges. Revista Territórios & Fronteiras, Cuiabá, 7(1), 2014.

- Dalosto, C., Dalosto, J.A.D., & Oliveira, C.L.F. (2019). As Políticas Públicas para as Comunidades Quilombolas no Brasil. In As Políticas Públicas frente a Transformação da Sociedade. https://doi.org/10.22533/at.ed.28019090712

- Edelman, M. (2013). Messy hectares: Questions about the epistemology of land grabbing data. Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(3), 485–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2013.801340

- Fischer, L., & da Cunha, R. (2013). Environmental and land tenure limitations of rural properties in Brazilian Amazonia. UFPA/ICJ.

- Fold, N., & Hirsch, P. (2009). Re-thinking frontiers in Southeast Asia. Geographical Journal, 175(2), 95–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.2009.175.issue-2

- Geiger, D. (2008). Turner in the tropics. The frontier concept revisited. In D. Geiger (Ed.), Frontier encounters. Indigenous communities and settlers in Asia and Latin America (pp. 75–215). IWGIA.

- Grêt-Regamey, A., & Brunner, S. (2011). Methodischer Rahmen für den Einsatz von Backcasting zur Anpassung an den Klimawandel. DISP, 184(184), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2011.10557123

- Holton, J.A., & Walsh, I. (2016). Classic grounded theory. Applications with qualitative and quantitative data. SAGE.

- Human Rights Watch. (2019). World report; Chapter Brazil. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/brazil

- Klingler, M. (2017). Die Post-Frontier Amazonien im Zeichen der Zero Deforestation. In D. Anhuf (Ed.), Brasilien – Herausforderungen der neuen Supermacht des Südens (pp. 133–142). Selbstverlag Fach Geographie der Universität Passau.

- Lüdeke, M.K.B., Petschel-Held, G., & Schellnhuber, H.J. (2004). Syndromes of global change: The first panoramic view. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 13(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.13.1.10

- Martins, J.D.S. (Ed.). (1997). Fronteira a degradação do outro nos confins do humano. Hucitec.

- Moreira da Silva, E., & Navegantes Alves, L. (2017). A ocupação do espaço pela dendeicultura e seus efeitos na produção agrícola familiar na Amazônia Oriental. Confins 2017, (30). doi:10.4000/confins.11843

- Nahum, J.S., & Santos, C.B. (2013). Impactos Socioambientais da Dendecultura em Comunidades Tradicionais na Amazônia Paraense. Revista ACTA Geográfica (2013), Boa Vista, Ed. Esp. Geografia Agrária, 63–80. https://doi.org/10.5654/actageo2013.0003.0004.

- Nahum, J.S., & Santos, C.B. (2016). A dendeicultura na Amazônia paraense. Geousp – Espaço E Tempo (Online), 20(2), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.11606/.2179-0892.geousp.2016.122591.

- Peluso, N.L., & Lund, C. (2011). New frontiers of land control: Introduction. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(4), 667–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.607692

- Priess, J.A., & Hauck, J. (2014). Integrative scenario development. Ecology and Society, 19(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06168-190112

- Ribot, J.C., & Peluso, N.L. (2009). A theory of access. Rural Sociology, 68(2), 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x

- Santos, R. (1980). História econômica da Amazônia (1800-1920). T.A. Queiroz.

- Schönenberg, R. (2011). Viel Land – Viel Streit. Konflikte und Konfliktlösungsstrategien in Amazonien. SVH.

- Schönenberg, R. (2019). Collateral Damage of Global Governance on the local Level - An analysis of fragmented international regimes in the Brazilian Amazon. In A. Polese, A. Russo, & F. Strazzari (Eds.), Governance beyond the law. The immoral, the illegal, the criminal, international political economy series. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schönenberg, R., Schaldach, R., Lakes, T., Göpel, J., & Gollnow, F. (2017). Inter- and transdisciplinary scenario construction to explore future land-use options in southern Amazonia. Ecology and Society, 22(3), 13. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09032-220313

- Simmons, C.S. (2005). Territorializing land conflict: Space, place, and contentious politics in the Brazilian Amazon. GeoJournal (2005), 64(4), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-005-5809-x

- Treccani, G. (2001). Violência e grilagem: Instrumentos de aquisição da propriedade da terra no Pará. UFPA, ITERPA.

- Turner, F.J. (1893). The significance of the frontier in American history, published by the American Historical Association in Chicago during the world’s Columbian exposition. Chicago World’s fair.

- von Reibnitz, U. (1988). Scenario techniques. McGraw-Hill GmbH.

- Welp, M., de la Vega-leinert, C., Stoll-Kleemann, S., & Jaeger, C. (2006). Science-based stakeholder dialogues: Theories and tools. Global Environmental Change, 16(2), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.12.002