ABSTRACT

Land-use conflict has become a topical issue due to an increase in the number of stakeholders having incompatible interests related to particular land uses. Competing land-uses include those for conservation, irrigation, game and livestock farming, settlements and mining. These groupings of land-uses have different interests and objectives. This study aims to investigate the basis for the land-use conflict, and to get insights into how various stakeholders perceive and interpret existing conflicts. Empirical results were drawn from observation, interviews and documents collected between 2011 and 2018. The interviews were held with various stakeholders involved in land-use decisions. Qualitative data were analysed through thematic content analysis, and observations assisted with the corroboration of information collected through interviews. The study recorded four central land-use conflicts: irrigation farming with conservation; game farming with conservation; settlements/livestock farming with conservation; and mining with conservation/game farming/irrigation farming. The study also explains how local stakeholders understand these conflicts.

1. Land-use in Mapungubwe: historical and current trends

Over the years, farming has been the main land-use activity in the Mapungubwe region (Anon, Citation1944; Union of South Africa, Citation1946). In 1922, conservation was introduced as an additional land-use activity when a block of nine farms was set aside at the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers, to form the Dongola Botanical Reserve. The primary aim of the reserve was to study the vegetation, and assess the agricultural and pastoral potential of the area (Carruthers, Citation1992, Citation2006). In 1944, the idea of a reserve was extended to the concept of a wildlife sanctuary after the Welsh botanist, Dr Pole-Evans, together with the then Prime Minister of the Union Jan Smuts and Minister of Lands Andrew Conroy, resolved that the area was not suitable for human habitation (Carruthers, Citation1992; The Star, Citation1945). It was at this time that the possibility of linking the proposed Sanctuary with conservation areas in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and the colony of Bechuanaland (now Botswana) was first mooted (Carruthers, Citation2006; Sunday Tribune, Citation1987). It would have been the first formal transfrontier conservation area (hereafter TFCA) in Africa. Unfortunately, the idea of a wildlife sanctuary led to land-use conflict because the position of conservationists on the use of the Mapungubwe landscape was very different from that of farmers in the area (Sinthumule, Citation2017a). Whilst conservationists viewed conservation of biodiversity as the best land-use option, farmers believed farming was the best land-use option.

As a result, the dream of creating a wildlife sanctuary was contested and challenged by private landowners (Sinthumule, Citation2017a). Opposition to the idea of a wildlife sanctuary did not end with farmers. Rather, it became a political issue that led to conflicts between Prime Minister Jan Smuts’ government (United Party) that was in favour of the sanctuary, and the opposition (National Party) that was against it (Union of South Africa, Citation1946). The establishment of the wildlife sanctuary went ahead in 1947; however, less than two years later it was abolished, following the victory of the National Party in the general elections of 1948 (Union of South Africa, Citation1949). The money that was raised for the development of the sanctuary was repaid to donors, and the farms acquired were returned to the original owners by the National Party government (Sinthumule, Citation2017a). Farming and a small provincial Vhembe Nature Reserve (comprising 8 746 ha), which was established in 1967 for conservation purposes, were the only two land-use activities in the Mapungubwe area until the early 1990s (Robinson, Citation1996).

Over the past three decades, the Mapungubwe area has been subjected again to a proposal for transformation, into a TFCA. Sandwith et al. (Citation2001) defined a ‘TFCA’ as a conservation area that straddles the political boundaries between two or more countries, and includes ‘natural systems’ of one or more protected areas. The dream of establishing the TFCA was finally realised on 22 June 2006, with the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) by the relevant Ministers of the three countries the TFCA is located in – South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe. The current Mapungubwe, however, is a fragmented landscape, as is evidenced by several land-uses in the TFCA. In addition to conservation, the landscape is also used for irrigation farming, game farming, livestock farming, mining, and for settlements by land claimants and farm workers. The position of conservationists – South African National Parks (SANParks), Peace Parks Foundation (PPF) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) – regarding the use of the Mapungubwe landscape is very different from other stakeholders such as farmers, mining companies and land claimants. Whilst conservationists are advocating for conservation of biodiversity, other stakeholders are more interested in consumptive uses of the land to bring economic benefits. As a result, the land is becoming a contested resource in Mapungubwe, leading to increased conflict between different land users. A greater land scarcity has also fostered competition amongst land-use actors (Müller & Munroe, Citation2014). As Campbell (Citation1996) has noted, every land-use conflict and competition is unique and emerges from site-specific social, economic and ecological interactions. As a result, each conflict requires specialised understanding of claims lain for land use.

The aim of this study is to analyse current conflicts between the above-mentioned land-use sectors in the study area, and to get insights into how stakeholders perceive and interpret these conflicts. The key research questions guiding the discussion of this paper are as follows: firstly, which of the land-use conflicts arise from wildlife conservation, irrigation farming, game farming, livestock farming, settlement or mining land-use sectors, respectively? Secondly, how do various stakeholders perceive and interpret land-use conflicts in the study area? In working towards answering these research questions, the study uses the South African section of Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area (hereafter GMTFCA) as the case study.

2. Understanding land-use conflicts

Researchers have used the concept of ‘land-use conflict’ in various ways in different settings. According to Magsi and Torre (Citation2013, p. 122), a … ‘land-use conflict is a social dispute that arises with the involvement of the institutions, development movements, non-governmental organisations, developers, industries, civil service and regulatory agencies, and often launched by the actions of a central actor introducing development projects’. Adam et al. (Citation2015) state that a land-use conflict is typically associated with competing interests over the type of land-use, limited access and use rights, unclear ownership and property rights, and the delineation of boundaries. For Wehrmann (Citation2005), a land-use conflict can be understood as the misuse, restriction or dispute over property rights to land. Given these conceptual variations, it is not surprising that there is little consensus on the definition of land-use conflict. However, this study adopts the Von der Dunk et al. (Citation2011, p. 149) definition that states that a ‘land-use conflict occurs whenever land-use stakeholders (i.e., conflict parties) have incompatible interests related to certain land-use units (i.e., geographical component)’.

Unlike the definitions of Adam et al. (Citation2015) and Wehrmann (Citation2005), it is the view of Steinhäußer et al. (Citation2015) that land ownership and property rights do not have to be the main issue causing land-use conflict. According to Von der Dunk et al. (Citation2011)’s definition, land-use conflict occurs between and among various stakeholders who usually have different interests, objectives and perceptions (Dumrongrojwatthana et al., Citation2011; Wehrmann, Citation2008). In other words, conflicts often occur when stakeholders become involved in opposing an undesired project or activity from being realized in an area (Hersperger et al., Citation2015; Jensen et al., Citation2019) or when stakeholders perceive that one land-use interferes with the function of another (Kaya & Erol, Citation2016; Magsi & Torre, Citation2013). Often these conflicts are associated with not in my backyard (NIMBY) reactions to new developments (Schively, Citation2007) and locally unwanted land-use (LULU) activities (Kaya & Erol, Citation2016; Schively, Citation2007). It is the view of other stakeholders that these projects should be located elsewhere because of their real or perceived harmful effects (Hersperger et al., Citation2015; Wehrmann, Citation2008). Land-use stakeholders have incompatible interests and Alston et al. (Citation2000) argue that under extreme circumstances, conflict might escalate into violence due to failed negotiations over land acquisitions or because of compensation disagreements (Rooij, Citation2007).

Recent literature has applied the definition of Von der Dunk et al. to explain land-use conflicts in various parts of the world, including Australia (Brown & Raymond, Citation2014), Germany (Steinhäußer, Siebert, Steinführer, & Hellmich, Citation2015), Sudan (Adam et al., Citation2015), Turkey (Kaya & Erol, Citation2016), North Carolina (Jensen et al., Citation2019) and Thailand (Phromma et al., Citation2019). Numerous studies have shown that land-use conflicts and tensions are especially predominant in urban and peri-urban areas (Jensen et al., Citation2019; Von der Dunk et al., Citation2011), protected areas (Phromma et al., Citation2019) and areas of new infrastructure development (Sabir et al., Citation2017). The same holds true for multifunctional landscapes (Darly & Torre, Citation2013; De Groot, Citation2006) and mining areas (Hilson, Citation2002; Moomen, Citation2017). Most research from these broad categories of land-use conflict has focused on the reasons leading up to conflict (Magsi & Torre, Citation2013), impacts of land-use conflict (Hilson, Citation2002; Sabir et al., Citation2017) and typology of conflicts (Torre et al., Citation2006; Von der Dunk et al., Citation2011). In addition, recent studies have focused on conflict resolution (Dumrongrojwatthana et al., Citation2011), which is conceptualized as the methods and processes involved in facilitating the peaceful ending of conflict. This is often done by engaging in collective negotiation (Hersperger et al., Citation2015). There has been limited research and analysis of multiple land-use conflicts in one area/region. Therefore, there are gaps in our understanding of land-use conflicts. This study contributes to the debate on land-use conflict, by analysing land-use conflicts arising from a variety of land-use sectors. The study argues that an understanding or analysis of contemporary conflicting issues is an important step before developing ideas for conflict resolution.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study area

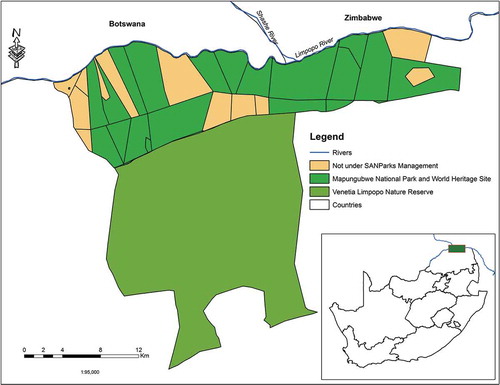

The study area is located in the Limpopo Province of South Africa and forms part of the GMTFCA which extends into Botswana and Zimbabwe. The case study was conducted in the South African section of the GMTFCA, situated at the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers. These rivers serve as a boundary between South Africa and both Botswana and Zimbabwe (). The conservation area encompasses the Mapungubwe National Park – made up of government and contracted freehold land – and is also known as the Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape because of the cultural significance of the area. According to Huffman (Citation2000), archaeologists date the earliest human settlements in Mapungubwe from one million to 250 thousand BC. The Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape was placed on the World Heritage List in 2003. The landscape was deemed worthy of World Heritage status based on evidence of an important interchange of human values that resulted in significant cultural and social changes in the southern African region between 900 and 1300 AD (Carruthers, Citation2006; Huffman, Citation2000). At the time, Mapungubwe was the largest ‘kingdom’ in the sub-continent and was estimated to comprise 9 000 inhabitants at its peak (Huffman, Citation2000). Its geographical position is significant because some seven hundred years ago, Mapungubwe straddled the trade routes with eastern Africa and Asia (Carruthers, Citation2006). On the southern side of the Mapungubwe National Park is the 36 000 ha Venetia Limpopo Nature Reserve, which was established in 1990 as a private nature reserve by the De Beers Mining Company.

3.2. Data gathering and analysis

The fieldwork that supports this paper was conducted between March 2011 and June 2018. Permission to conduct this research was granted by SANParks. The project was also discussed in the Trilateral Technical Committee (TTC) meeting of 8 June 2011 and approved by committee members from three participating countries. Authorization to interact with people at the local level were obtained from farm owners and managers as well as land claimants. The fieldwork involved observations and home interviews with participants. In addition, the study also relied on documents as a key means of data collection. Purposive sampling was used as the main sampling approach to select informants of this study. As Guest et al. (Citation2006) noted, in purposive sampling, there is no overall sampling design that dictates the number of interviewees required. In congruence with methodologies proposed/followed by Guest et al. (Citation2006) and Bernard (Citation2017), respondents were interviewed until the point at which no new information or themes were observed in the data. This was done to ensure that the sample size was adequate. The sample for this study was drawn from land-use stakeholders – organisations and individuals who make decisions or who have an interest in land-use and its impacts. This included the officials from Mapungubwe National Park (N = 3), officials from Venetia Limpopo Nature Reserve and De Beers Consolidated Mines (N = 2), game farmers and managers (N = 11), irrigation farmers and managers (N = 15), an official from Coal of Africa Limited (N = 1), and land claimants who are also residents of Mapungubwe (N = 6). Collectively, a total sample size of 38 participants was interviewed based on their willingness and availability. The sample comprised four females and 34 males, and the oldest interviewee was 78 years while the youngest was 44.

Respondents were asked their permission before they were interviewed. Participants were briefed about the purpose and scope of the research and were notified that researchers are academics who are not involved in possible conflict-resolution processes. They were also informed that their participation was voluntary, and that their individual identities would be kept confidential. Informants were further notified that they could terminate their participation at any time should they feel that they no longer want to participate. A semi-structured, face-to-face interview was used as the data collection technique. This method was found suitable because it is flexible and allows for an open dialogue that can extend beyond the questions set in the interview schedule (Corbetta, Citation2003).

The interview questions were prepared to capture local views regarding land-use conflict in Mapungubwe. Stakeholders were asked to explain land-use changes, concurring and conflicting issues in Mapungubwe from their organisation’s point of view, and the implications of these factors on the area. The length of an interview ranged from 45 to 60 min and all responses were recorded in a notebook. Interviews were conducted in English and Tshivenda and no interpreter was required since the authors are fluent in both languages. Respondents interviewed did not show any resistance to the research. They were accommodating and expressed their views freely. Informants who were interviewed during a first visit were interviewed again in a second visit, and they were still willing to participate and share their experiences regarding land-use conflicts in the area. Their cooperation in a second visit was important in order to validate the information given in the first visit. Data obtained from the interviews were analysed using thematic content analysis. This is a qualitative analytic method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns or themes within data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The four themes that emerged are discussed below. Field observations helped in validating information provided through interviews. It also assisted to observe new land-use developments in the area. Other sources of data included newspaper articles and PPF reports and maps. These documents provided a means to examine land-use changes, conflicting issues, and the implications of these in Mapungubwe.

4. Results

Four themes emerged following a thematic analysis of the qualitative data. Each of these themes is discussed in turn in this section.

4.1. Land-use conflicts between irrigation farming and conservation

Over the last three decades, conservationists including SANParks, PPF and WWF have been at the forefront of the attempt to convert the whole of the Mapungubwe region into TFCA. Currently, the Mapungubwe National Park forms only part of the TFCA. It is important to note that the PPF is a non-governmental organization created in 1997 with the purpose of stimulating and facilitating the development of TFCAs in the region. The vision for converting the Mapungubwe area into a TFCA has been achieved through buying some of irrigation farms in the area. Irrigation farmers are private landowners whose properties are located within or around Mapungubwe National Park. These landowners have property rights that empower them to have control over their land. The farms are mainly used for citrus and crop farming. The main crops that are planted include beans, sweet potatoes, cabbages, tomatoes, butternut, green peppers, watermelons and maize. Although several farms were purchased from private landowners for purposes of conservation, some irrigation farmers were not interested in selling their land for conservation purposes (Sinthumule, Citation2016a, Citation2017a). One farmer commented: I have been farming on this land for 38 years. Wealth comes from the soil. This land is big enough to make a living for me and my family. I have no intentions of selling it to anyone including SANParks (Interview#1, 22/09/2016).

As a result, Mapungubwe National Park remains a fragmented landscape. There are currently 13 large-scale irrigation farms that fall within either the Mapungubwe National Park or the TFCA, but are not part of either conservation entity (). Irrigation farming and conservation are two types of land-use activities that are not compatible. As a result, there is a conflict between conservationists and commercial irrigation farmers. The conflict revolves around wildlife – particularly elephants – causing damage to irrigation farms in the Mapungubwe area. The Mapungubwe region is semi-arid and a very dry area with low and unpredictable rainfall. Consequently, the elephants from the Mapungubwe National Park and the TFCA are attracted to irrigation farms because these areas are always green.

Fieldwork evidence suggests that elephants regularly destroy electric fencing and find their way into the farms where they ‘harvest the fruits and crops on behalf of the farmers’. One farmer narrated: Elephants eat whatever they want at any time in our farms. When we report the matter to SANParks management and the Department of Environmental Affairs, they only come and take pictures. The main painful thing is that we are not compensated for the damage caused by elephants (Interview#2, 23/09/2016). It is clear that the elephants cause serious destruction on irrigation farms in Mapungubwe, which results in economic losses. Irrigation farmers also complain that ever since the idea of a TFCA emerged in the Mapungubwe region, SANParks has been reluctant to maintain its fence. Subsequently, commercial irrigation farmers in the Mapungubwe area see this reluctance as an act of de-fencing by default (Interview#3, 23/07/2011; Interview#4, 09/12/2011). SANParks, on the other hand, argue that it maintains the fences regularly. Other small to medium-bodied wildlife such as baboons, bush pigs, vervet monkeys, warthog, waterbuck and bushbuck were also reported to be causing serious damage on irrigation farms in Mapungubwe. Baboons and monkeys are responsible for damage during the day, whereas bush pigs cause damage during the evening. Farmers indicated that in order to avoid small- to medium-bodied wildlife from causing destruction, they are paying huge amounts monthly to employees guarding against invasions from wildlife.

4.2. Land-use conflicts between game farming and conservation

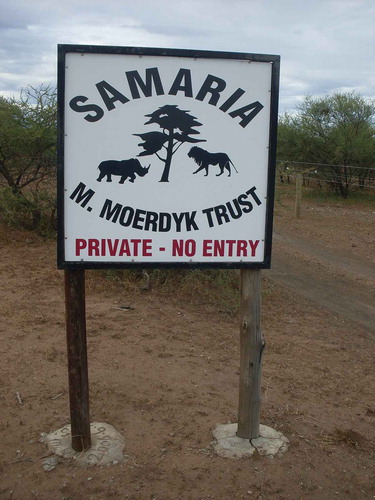

Game farmers are white private landowners whose business interest is game farming. These game farms were acquired during colonial and apartheid era. The passing of the Natives Land Act in 1913 empowered white minority over the black majority in terms of land ownership. The democratic state inherited this skewed land ownership, which was written into land policy. Game farms are located within and around Mapungubwe National Park and the TFCA. As with irrigation farmers, game farmers have property rights that allow them to have control over their land. Although conservationists have been successful in buying some game farms and negotiating a contractual agreement, some game farmers were not – and are still not – interested in releasing their land for conservation purposes (Sinthumule, Citation2016a). This refusal can be seen as an act of resistance against the new land-use activity. At the time of this study, there were ten game farms of varying ownership status within Mapungubwe National Park and the TFCA, and which were not managed by SANParks (). Game farming and conservation are two land-use activities that are not compatible for several reasons. First, there are differences in the utilisation of wildlife resources. In Mapungubwe National Park, photographic tourism is the sole economic driver and trophy hunting is not permitted. On the other hand, game farmers within and around Mapungubwe National Park rely on a combination of trophy hunting, live capturing of wildlife and biltong hunting as a source of income. These are lucrative businesses in southern Africa, which in the case of Mapungubwe has prompted game farmers to refrain from contractual agreements or selling their farms to SANParks as they fear losing their farms (Interview#5, 13/09/2018). Secondly, it is reported that tourists who pay high sums of money to be in the wilderness area complain about gunshots particularly during the hunting season. This jeopardises the park’s wildlife-based tourism attractions. As a result, conservationists view game hunting as a threat to conservation. Thirdly, other areas within Mapungubwe National Park are ‘no-go zones’ and there is signage prohibiting guests and tourists from entering private land (). These restrictions inconvenience officials and tourists on game drives in Mapungubwe National Park because they are not permitted to proceed through private land (Interview#6, 22/06/2011).

4.3. Land-use conflicts between settlement/livestock farming and conservation

The conflict between settlement/livestock farming and wildlife conservation is controversial. Former residents of Mapungubwe who were forcibly removed used the provisions of the Restitution of Land Rights Act 22 of 1994 to seek restitution. It is important to note that land restitution is one of the three pillars of land reform programme in South Africa. Consequently, the whole of Mapungubwe National Park, including the surrounding private land, is under claim. However, the land claims remain unresolved. In 2020, only one land claim, namely that of Den Staat Farm (within Mapungubwe National Park), was resolved in favour of the Machete and Sematla clans. The land claimants moved back onto the farm in 2009 with all their property, including livestock such as cattle, goats and sheep. The land claimants are using the farm for farming (livestock and irrigation) and as a settlement. The farm is used as grazing land for the livestock, which serves as a source of income for the land claimants (Interview#7, 22/06/2011). Thus, the land claimants are more concerned with consumptive uses of the land which will bring economic benefits to their lives. Unfortunately, the presence of livestock within the conservation area has created land-use conflict. The land claimants reported that wildlife – particularly lions, leopard, jackals and hyena – hunt the livestock on Den Staat Farm. This has devastating effects on the livelihoods of the land claimants.

At the time of this study, Den Staat Farm was administered as state land, meaning that the land claimants have no legal rights to use the land and its resources as they wish. It is for this reason that one of the land claimants who killed a rhino on Den Staat Farm in 2015 was arrested and charged for killing a wildlife in the property (Interview#8, 23/09/2016). This has intensified the conflict between land claimants and conservationists. The land claimants also use Den Staat Farm for irrigation farming and as a residential area (Interview#9, 06/06/2013). At the time of this research, it was estimated that 150 people were working and staying on the farm (Interview#10, 06/06/2013). As a result, SANParks is worried about the increased numbers of people on the farm. It was reported that more snares are now found on a regular basis particularly near Den Staat Farm, as well as near other irrigation farms with high populations of farmworkers (Interview#11, 24/09/2016). SANParks is also of the view that there is the harvesting of resources such as fuel-wood and fish within the park. As a result, SANParks maintains that the conservation of biodiversity is compromised because of the presence of people within the national park (Interview#12, 14/01/2013).

The study also found that livestock from Maramani, the neighbouring communal land in Zimbabwe, frequently pass through the Limpopo River to access grazing on Mapungubwe National Park. As a result, livestock graze together with wildlife with the consequent competition over grazing material. This may lead to problems of overgrazing particularly near the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers (Interview#13, 24/09/2016). Furthermore, the presence of livestock in Mapungubwe National Park is not only a huge concern for SANParks, but also for tourists visiting the park. For instance, ‘Tourist anger over cattle grazing in Mapungubwe National Park’ was the title of an article in the Daily Maverick newspaper describing the land-use conflict between livestock and wildlife in Mapungubwe. Recent sightings of an unspecified number of cattle inside the park from communal areas in Zimbabwe have raised the ire of several tourists seeking wilderness experiences. For instance, Ken Borland, a Johannesburg-based birdwatcher and wildlife lover narrated; ‘I was horrified by the number of cattle from across the border that were in the park and had clearly pushed much of the indigenous game out of the riverine areas. We saw way less game along the Limpopo River than we are accustomed to seeing, and there were also people fishing in the river on the park side’ (Daily Maverick Newspaper, Citation2018). As a result, there is a fear that the livestock will denude scarce grazing and jeopardise the park’s wildlife-based tourism attractions.

4.4. Land-use conflicts between mining and conservation/game farming/irrigation farming

The Mapungubwe region possesses several important mineral deposits that include calcite, granite, copper, marble, asbestos, diamonds and coal. However, most of the minerals in the region are relatively low-priced and have not been exploited (Robinson, Citation1996). In addition to diamond mining, there is also an abundance of coal deposit associated with the Volksrust Shale Formation that occurs north of Alldays in the Pontdrift area (Hall-Martin et al., Citation1994). Over the past 10 years, mining in Mapungubwe has generated much publicity after Limpopo Coal; a subsidiary of the Australian company Coal of Africa Limited, was granted mineral rights in 2010 by the South African Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) to mine coal 7 km away from Mapungubwe National Park. This was despite the park being a proclaimed World Heritage Site and a TFCA. Coal of Africa has bought a number of farms for the purpose of mining coal. As with irrigation and game farmers, Coal of Africa has property rights over their land that empower them to undertake mining or any other land-use activity. The initial approval by the DMR was challenged by the Mapungubwe Action Group, which comprised of local landowners, the Endangered Wildlife Trust, the Association of Southern African Professional Archaeologists, PPF, WWF, Birdlife South Africa, the Wilderness Foundation of South Africa and the office of the international coordinator of GMTFCA. The groups interdicted Limpopo Coal (Pty) Ltd on the basis that the location of its Vele Colliery, and the mining and related operations, would impact on the unique and sensitive landscape (Peace Parks Foundation, Citation2010).

Despite the objections by conservation lobby groups, in 2011 a new order mining right was awarded for the Vele colliery and its environmental management plan was approved. Mapungubwe Action Group did not object to the subsequent approval for Vele Colliery. When mining eventually began, there were air pollution complaints from private landowners (irrigation and game farmers) bordering the mine. For private landowners, there was also the fear that too much of dust from the coalmine would adversely affect the growth of citrus fruits and other crops on irrigation farms. It was believed that dust from mining would reduce production which would significantly jeopardise food security and the jobs of thousands of farm workers who are currently employed in the area (Interview#14, 26/03/2013). It was also believed that dust from mining would affect the growth of plant species which were the only sources of food for wildlife. This, it was feared, would subsequently lead to the collapse of the game farming industry in the area. There were also complaints about noise pollution because of heavy machinery used in the mine, as well as heavy traffic as a result of too many trucks coming in and out of the mine (Interview#15, 26/03/2013). Furthermore, there was the fear that with time, mining would ultimately lead to water pollution in the Limpopo River which would have devastating effects on farming. There was also concern that the region does not have sufficient water to maintain both farming and mining (Interview#16, 26/03/2013).

5. Discussion

Conflict between farming and conservation is a recurring problem wherever the home ranges of wildlife are also occupied by humans. According to responses received crop and livestock depredation by wildlife are the biggest threat in Mapungubwe. However, this is not unique to Mapungubwe; rather it is widespread in the condition in states where wildlife is abundant. For instance, crop depredation by wildlife has been reported to be common around Ngamiland in Botswana (Jackson et al., Citation2008), Daxueshan Nature Reserve in China (Huang et al., Citation2018) and the Białowieża and Knyszyn forests in Poland (Hofman-Kamińska & Kowalczyk, Citation2012). Similarly, numerous other authors also note how livestock within or around protected areas are killed by carnivores globally (Bauer et al., Citation2017; Boitani et al., Citation2011; Karanth et al., Citation2018). This threatens farmers’ income and food security, and contributes significantly to farmers’ negative attitudes towards wildlife and protected areas.

Farmers around the world applied conflict-mitigation approaches ranging from traditional scaring with noise and fire, to using high-technology repellents and fencing (King et al., Citation2011). In the study area, the use of electric fences by farmers as a mitigation strategy to reduce conflict has proved ineffective. As a result, even though farms are surrounded by electric fencing, wildlife are responsible for widespread killing of livestock and the destruction of citrus groves and fruit. The situation is made worse because SANParks has been reluctant to maintain its fence. This is in line with the concept of creating a borderless landscape to allow free movement of wildlife across the border (Sinthumule, Citation2014, Citation2017b). Over the years, conservationists have recognised that the cost of conserving wildlife is often borne disproportionately by farmers and those living around protected areas. As a result, this has spawned strategies to reduce human-wildlife conflict around protected areas (Watve et al., Citation2016). This includes killing the pests/problem animals, as occurs in the northwestern United States (Bangs et al., Citation2005), or utilising a range of non-lethal techniques in order to reduce crop loss (Osborn & Hill, Citation2005). In most countries, wildlife protection laws prohibit the killing of problem species for reasons such as crop or livestock depredation.

Given that the prevention of all damage by wildlife or the killing of problematic wildlife is not achievable, one popular response is to compensate farmers or rural residents for the costs of wildlife damage (Osborn & Hill, Citation2005). Compensation has become a policy principle to address land-use conflicts in many parts of the world. However, in the study area, local farmers are not compensated for the damage caused by wildlife. This has already created some antagonism and even hatred towards wildlife because farming is the only source of income for these farmers.

Property and power relation have emerged as an important issue contributing to land-use conflicts between private landowners, land claimants and conservationists. As documented by many scholars, power relations manifest in nature conservation projects (Brandt et al., Citation2018; Kepe et al., Citation2005; Spierenburg et al., Citation2008). In the Mapungubwe area, while private landowners have property rights that empower them to have control over their land and its resources, land and resource rights on the farms occupied by land claimants are currently administered as a state land. As a result, the land claimants cannot use the farm as they wish – as in the case of the Makuleke community in the Kruger National Park (Kepe et al., Citation2005).

For instance, in Mapungubwe, private landowners can hunt or mine and thus make an income on their property, whereas their counterparts (land claimants) in Den Staat farm cannot hunt game or mine minerals. Similarly, private landowners within the borders of Mapungubwe National Park and the TFCA have used their land rights to resist the incorporation of their land into the Park (Ramutsindela & Sinthumule, Citation2017), whereas the incorporation of Den Staat farm requires the approval of government and not the land claimants. In this sense, property rights on private farms serves as a source of security, and as a sacred barrier even to the powers of the state. While conflict is common where there are people (Kepe et al., Citation2005; Spierenburg et al., Citation2008), what is of concern is that it is often ignored by those in power. This translates to continued marginalization of the land claimants who were dispossessed off their land during the colonial and apartheid eras. These conflicts at play in Mapungubwe challenge the whole idea of turning Mapungubwe into a TFCA. In the prevailing logic, private land can be defined as non-state spaces where private landowners reassert their authority and sovereignty over the land and its resources (Brandt et al., Citation2018). Another issue at the heart of the conflict is the livestock that graze inside Mapungubwe National Park. The analysis of our result revealed that the problem of livestock grazing in the park has already angered tourists who do not want to see cattle in a conservation area. Whilst tourists complain about cattle invasion into conservation areas, nothing is said about wildlife invasion into communal land in Maramani (Sinthumule, Citation2020). Mapungubwe National Park and the GMTFCA are marketed as a cultural landscape. Currently, the land use within the Mapungubwe Cultural landscape includes a national park, rural communities and their livelihoods, game ranching, agricultural activities, and World Heritage Site. This is in line with a bioregional model that seeks to integrate social, economic and ecological factors at a landscape level (Sayer et al., Citation2013; Sinthumule, Citation2016b). As a result, the grazing of livestock in the Mapungubwe National Park is to be expected. In fact, this makes Mapungubwe National Park unique as the only park in South Africa that accommodates different types of land-use. Thus, tourists need to appreciate and enjoy the Mapungubwe Cultural landscape for what it is and not compare it with other national parks.

Mining has emerged as the biggest threat in Mapungubwe because it affects all other land-use sectors. The conflict with mining reflects the LULU and NIMBY phenomenon (Schively, Citation2007). The results obtained in Mapungubwe showed broad similarities to those in Papua New Guinea (Hilson, Citation2002) and Ghana (Schueler et al., Citation2011), as in both cases the establishment of a mine resulted in land-use conflicts with local stakeholders. Land-use conflict is more common between mining and other land-use sectors because mining places fundamentally different socio-economic values on land (Moomen, Citation2017). Although mining is an important component of the economy of many nations, particularly in the developing world (Schueler et al., Citation2011), it is argued that local livelihoods rarely profit from mining activities (Kumah, Citation2006). Instead, the land demands placed particularly by surface mines often disrupt activities of nearby land-use sectors and hinder the development of other potentially profitable activities (Hilson, Citation2002). In the case of Mapungubwe, our interviewees indicated that local land-users are opposed to mining, as they are concerned about the social, economic and environmental impacts of mining (Schueler et al., Citation2011). They also recognized that the interconnectedness of the environment implies that mining activities can have detrimental impacts on other land-use sectors.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that land-use conflict around protected areas is a significant and growing problem around the world. Despite considerable research devoted to resolving problems of land-use conflict, wildlife continue to threaten local communities and farmers’ income and food security across the world. Ignoring this phenomenon does not help in achieving conservation goals, but rather contributes significantly to farmers’ hostility towards wildlife and conservation. As a result, compensation has become a policy principle to address land-use conflicts in many parts of the world. The empirical data presented in this paper supports this policy principle. What is distinctive about Mapungubwe is that unlike in other parts of the world, farmers and local communities are not compensated for the damage caused by wildlife. We thus identify compensation for wildlife damages as a promising mitigation strategy. A percentage of the revenue generated through tourism should be earmarked to establish a compensation scheme. Alternatively, funds for compensation can be raised from donors supporting conservation.

This study has also shown that the consolidation of land to create a TFCA in a human-dominated landscape is a social process shaped through local contestation over land, power, and belonging. While the powerful private landowners have property rights that permit them to have control over their land, this is sadly not the case for the powerless land claimants on Den Staat farm. As a result, unclear property rights does not only marginalise the land claimants, but also have long-lasting impacts on their lives and livelihoods.

With regard to mining, this study has demonstrated that other land-use stakeholders have negative attitudes towards the sector in Mapungubwe. Despite that local land-use stakeholders are against mining, mining permit has been issued by the DMR. This raises a host of questions. We end by raising some of these questions regarding mining in Mapungubwe. To our mind the fundamental – and as yet unanswered – question is why the government has approved the reopening of Vele mine in Mapungubwe despite objections by Mapungubwe Action Group? Were local land-use stakeholders consulted from the onset about mining in the area? Were the inputs of local land-use stakeholders taken into account when issuing mining permit?

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the respondents in Mapungubwe who participated in this study between 2011 and 2018.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam, Y.O., Pretzsch, J., & Darr, D. (2015). Land use conflicts in central Sudan: Perception and local coping mechanisms. Land Use Policy, 42, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.06.006

- Alston, L.J., Libecap, G.D., & Mueller, B. (2000). Land reform policies, the sources of violent conflict, and implications for deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 39(2), 162–188. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeem.1999.1103

- Anon. (1944). Homestead or wild animals? A Northern transvaal scandal being the story of the Dongola Botanical Reserve now told for the first time (Unpublished report) Zoutpansberg Farmer’s Union, The Dongola Committee.

- Bangs, E.E., Fontaine, J.A., Jimenez, M.D., Meier, T.J., Bradley, E.H., Niemeyer, C.C., … Oakleaf, J.K. (2005). Managing wolf-human conflict in the northwestern United States. Conservation Biology Series-cambridge-, 9, 340. https://0-doi-org.ujlink.uj.ac.za/10.1017/CBO9780511614774

- Bauer, H., Müller, L., Van Der Goes, D., & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2017). Financial compensation for damage to livestock by lions Panthera leo on community rangelands in Kenya. Oryx, 51(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003060531500068X

- Bernard, H.R. (2017). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Rowman and Littlefield.

- Boitani, L., Ciucci, P., & Raganella-Pelliccioni, E. (2011). Ex-post compensation payments for wolf predation on livestock in Italy: A tool for conservation? Wildlife Research, 37(8), 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR10029

- Brandt, F., Josefsson, J., & Spierenburg, M. (2018). Power and politics in stakeholder engagement. Ecology and Society, 23(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10265-230332

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, G., & Raymond, C.M. (2014). Methods for identifying land use conflict potential using participatory mapping. Landscape and Urban Planning, 122, 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.11.007

- Campbell, S. (1996). Green cities, growing cities, just cities?: Urban planning and the contradictions of sustainable development. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369608975696

- Carruthers, J. (1992). The Dongola Wild Life Sanctuary:‘psychological blunder, economic folly and political monstrosity’or ‘more valuable than rubies and gold’? African Historical Review, 24(1), 82–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00232089285310081

- Carruthers, J. (2006). Mapungubwe: An historical and contemporary analysis of a World Heritage cultural landscape. Koedoe, 49(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v49i1.89

- Corbetta, P. (2003). Social research: Theory, methods and techniques. Sage publications.

- Daily Maverick Newspaper. (2018, January 15). Tourist anger over cattle grazing in Mapungubwe national park. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-01-15-tourist-anger-over-cattle-grazing-in-mapungubwe-national-park/

- Darly, S., & Torre, A. (2013). Conflicts over farmland uses and the dynamics of “agri-urban” localities in the Greater Paris Region: An empirical analysis based on daily regional press and field interviews. Land Use Policy, 33, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.12.014

- De Groot, R. (2006). Function-analysis and valuation as a tool to assess land use conflicts in planning for sustainable, multi-functional landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning, 75(3–4), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.02.016

- Dumrongrojwatthana, P., Le Page, C., Gajaseni, N., & Trébuil, G. (2011). Co-constructing an agent-based model to mediate land use conflict between herders and foresters in northern Thailand. Journal of Land Use Science, 6(2–3), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2011.558596

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Hall-Martin, A.J., Novellie, P.A., & Knight, M.H. (1994): Dongola: Proposal for the creation of a major transfrontier national park between South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe, unpublished report, National Parks Board.

- Hersperger, A.M., Ioja, C., Steiner, F., & Tudor, C.A. (2015). Comprehensive consideration of conflicts in the land-use planning process: A conceptual contribution. Carpathian Journal of Earth and Environmental Sciences, 10(4), 5–13.

- Hilson, G. (2002). An overview of land use conflicts in mining communities. Land Use Policy, 19(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(01)00043-6

- Hofman-Kamińska, E., & Kowalczyk, R. (2012). Farm crops depredation by European bison (Bison bonasus) in the vicinity of forest habitats in northeastern Poland. Environmental Management, 50(4), 530–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-9913-7

- Huang, C., Li, X.Y., Shi, L.J., & Jiang, X.L. (2018). Patterns of human-wildlife conflict and compensation practices around Daxueshan Nature Reserve, China. Zoological Research, 39(6), 406. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2018.056

- Huffman, T.N. (2000). Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe culture. Goodwin Series, 8, 14–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/3858043

- Jackson, T.P., Mosojane, S., Ferreira, S.M., & van Aarde, R.J. (2008). Solutions for elephant Loxodonta africana crop raiding in northern Botswana: Moving away from symptomatic approaches. Oryx, 42(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605308001117

- Jensen, D., Baird, T., & Blank, G. (2019). New landscapes of conflict: Land-use competition at the urban–rural fringe. Landscape Research, 44(4), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1413173

- Karanth, K.K., Gupta, S., & Vanamamalai, A. (2018). Compensation payments, procedures and policies towards human-wildlife conflict management: Insights from India. Biological Conservation, 227, 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.07.006

- Kaya, I.A., & Erol, N.K. (2016). Conflicts over Locally Unwanted Land Uses (LULUs): Reasons and solutions for case studies in Izmir (Turkey). Land Use Policy, 58, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.011

- Kepe, T., Wynberg, R., & Ellis, W. (2005). Land reform and biodiversity conservation in South Africa: Complementary or in conflict? The International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management, 1(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17451590509618075

- King, L.E., Douglas‐Hamilton, I., & Vollrath, F. (2011). Beehive fences as effective deterrents for crop‐raiding elephants: Field trials in northern Kenya. African Journal of Ecology, 49(4), 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2011.01275.x

- Kumah, A. (2006). Sustainability and gold mining in the developing world. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(3–4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.08.007

- Magsi, H., & Torre, A. (2013). Approaches to understand land use conflicts in the developing countries. The Macrotheme Review, 1(2), 119–136. https://prodinra.inra.fr/record/179383

- Moomen, A.W. (2017). Strategies for managing large-scale mining sector land use conflicts in the global south. Resources Policy, 51, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2016.11.010

- Müller, D., & Munroe, D.K. (2014). Current and future challenges in landuse science. Journal of Land Use Science, 9(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2014.883731

- Osborn, F.V., & Hill, C.M. (2005). Techniques to reduce crop loss: Human and technical dimensions in Africa. Conservation Biology Series-cambridge-, 9, 72. https://0-doi-org.ujlink.uj.ac.za/10.1017/CBO9780511614774

- Peace Parks Foundation. (2010). Mining in the Mapungubwe area ceases-for now. Press release, Peace Parks Foundation.

- Phromma, I., Pagdee, A., Popradit, A., Ishida, A., & Uttaranakorn, S. (2019). Protected area co-management and land use conflicts adjacent to Phu Kao–Phu Phan Kham National Park, Thailand. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 38 (5), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2019.1573689

- Ramutsindela, M., & Sinthumule, I. (2017). Property and difference in nature conservation. Geographical Review, 107(3), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2016.12208.x

- Robinson, G.A. (1996): Limpopo valley national park: towards transfrontier conservation in southern Africa, Unpublished report, National Parks Board.

- Rooij, B.V. (2007). The return of the landlord: Chinese land acquisition conflicts as illustrated by peri-urban Kunming. Journal of Legal Pluralism, 55(55), 211–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2007.10756176

- Sabir, M., Torre, A., & Magsi, H. (2017). Land-use conflict and socio-economic impacts of infrastructure projects: The case of Diamer Bhasha Dam in Pakistan. Area Development and Policy, 2(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2016.1271723

- Sandwith, T., Shine, C., Hamilton, L., & Sheppard, D. (2001). Transboundary protected areas for peace and cooperation. IUCN.

- Sayer, J., Sunderland, T., Ghazoul, J., Pfund, J.L., Sheil, D., Meijaard, E., … Van Oosten, C. (2013). Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(21), 8349–8356. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210595110

- Schively, C. (2007). Understanding the NIMBY and LULU phenomena: Reassessing our knowledge base and informing future research. Journal of Planning Literature, 21(3), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412206295845

- Schueler, V., Kuemmerle, T., & Schröder, H. (2011). Impacts of surface gold mining on land use systems in Western Ghana. Ambio, 40(5), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-011-0141-9

- Sinthumule, N.I. (2014). Land use change and bordering in the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area [Doctoral dissertation], University of Cape Town.

- Sinthumule, N.I. (2016a). Contested land in peace parks: The Case of greater Mapungubwe. Proceedings of the Centenary Conference of the Society of South African Geographers (pp. 125–132), Stellenbosch, South Africa.

- Sinthumule, N.I. (2016b). Multiple-land use practices in transfrontier conservation areas: The case of Greater Mapungubwe straddling parts of Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, 34(34), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1515/bog-2016-0038

- Sinthumule, N.I. (2017a). Resistance against conservation at the South African section of Greater Mapungubwe (trans) frontier. Africa Spectrum, 52(2), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/000203971705200203

- Sinthumule, N.I. (2017b). Unfulfilled promises: An exposition of conservation in the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier. Africa Today, 64(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.64.1.03

- Sinthumule, N.I. (2020). Borders and border people in the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier. Landscape Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2019.1632819

- Spierenburg, M., Steenkamp, C., & Wels, H. (2008). Enclosing the local for the global commons: Community land rights in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area. Conservation and Society, 6(1), 87–97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26392913

- The Star (1945, April 5). Dongola wildlife sanctuary scheme.

- Steinhäußer, R., Siebert, R., Steinführer, A., & Hellmich, M. (2015). National and regional land-use conflicts in Germany from the perspective of stakeholders. Land Use Policy, 49, 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.08.009

- Sunday Tribune (1987). Plan to Resurrect Dongola Game Reserve, The “New” Kruger Park, 15 November, Johannesburg.

- Torre, A., Aznar, O., Bonin, M., Caron, A., Chia, E., Galman, M., & Paoli, J.C. (2006). Conflicts and tensions around the uses of space in rural and peri-urban areas. The case of six French geographical areas. Regional Urban Economics Review, (3), 415–453. https://www.cairn.info/revue-d-economie-regionale-et-urbaine-2006-3-page-415.htm

- Union of South Africa. (1946). Report of select committee on the Dongola Wild Life Sanctuary Bill (Hybrid Bill) (Vol. 2). Government Printers.

- Union of South Africa. (1949). Table of alphabetical contents and table of laws, repealed or amended by these statutes. Government Printers.

- Von der Dunk, A., Grêt-Regamey, A., Dalang, T., & Hersperger, A.M. (2011). Defining a typology of peri-urban land-use conflicts–A case study from Switzerland. Landscape and Urban Planning, 101(2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.02.007

- Watve, M., Patel, K., Bayani, A., & Patil, P. (2016). A theoretical model of community operated compensation scheme for crop damage by wild herbivores. Global Ecology and Conservation, 5, 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.11.012

- Wehrmann, B. (2005) Landkonflikte im urbanen und peri-urbanen Raum von Großstädten in Entwicklungsländern. Mit Beispielen aus Accra und Phnom Penh. Urban and Peri-urban Land Conflicts in Developing Countries. Research Reports on Urban and Regional Geography 2. Berlin.

- Wehrmann, B. (2008). Land conflicts: A practical guide to dealing with land disputes (pp. 12–13). Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (gtz).