ABSTRACT

The Santa Cruz lowlands, east Bolivia, are one of South America’s most dynamic agricultural frontiers. In the Chiquitania, bordering Brazil, San Ignacio de Velasco was in 2017 ranked first nationally in terms of deforestation. There, two deforestation fronts meet with mechanized agriculture expanding from the West and South and cattle ranching from the East. Chiquitano communities are demographically dominant locally but often face land scarcity. Because of their comparatively low impact on forest vegetation, they are not well represented in broad-scale quantitative Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) studies. Based on an empirical, human geographical approach, this paper investigates the transformation of the local indigenous productive matrix, the associated land-use patterns and potential socio-ecological implications. The overall aim is to bear witness to the rapid and profound reconfiguration of traditional livelihoods with their integration in the market economy and to highlight the significance of micro-scale LULC-processes at global scale.

Introduction

Lowland indigenous populations have generally been perceived as actors of low influence in state-of-the-art studies on the rapid Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) changes associated with the expansion of the agricultural frontier in East Bolivia. Attention has, instead, been focused on the actors most responsible for the rapid forest conversion, especially agroindustrial (trans)national companies, cattle ranchers and (Andean, Japanese and Mennonite) farmer colonists (Killeen et al., Citation2008; Müller et al., Citation2014; Thiele, Citation1995). Lowland indigenous populations have occasionally secured large territories,Footnote1 which are still mostly covered by (primary) forestFootnote2 (Martinez, Citation2000; Paye et al., Citation2010; Tierra, Citation2011). Therefore, they are often perceived as actors who may contribute to curbing deforestation. For example, Tejada et al. (Citation2016) elaborated LULC scenarios for the Bolivian lowlands, which explicitly considered formally designated indigenous territories. In theory, these territories may guarantee a controlled access to the forests and natural resources therein, and thus play a critical role in the future maintenance of primary forests. In practice however, the designation of indigenous territories, protected areas or forest reserves has not succeeded in halting the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the eastern Bolivian lowlands (Cuéllar et al., Citation2012; Fundación para la Conservación del Bosque Chiquitano [FCBC], Citation2015).

I focus on Chiquitano populations, who have not secured official territories, and face chronic land scarcity due to historical dispossession and unresolved land titling procedures exacerbated by demographic growth. This is well illustrated in the situation of the Chiquitano communities of the Velasco Province, in particular the District of San Ignacio de Velasco,Footnote3 East Bolivia, which are undergoing profound transformations (de la Vega-Leinert, Citation2017). Indeed, this region lies between two converging fronts of land conversion: the rapid progression of commercial agroindustry (in particular soybean cultivation) from the West and South, and of cattle ranching from Brazil’s Mato Grosso in the East (de la Vega-Leinert & Huber, Citation2019; Meyfroidt et al., Citation2014; Redo et al., Citation2011). Chiquitano communities have, until recently, maintained a largely subsistence-based economyFootnote4 associated with comparatively low rates of forest conversion, despite changing policy contexts (Kaimowitz et al., Citation1999; Killeen et al., Citation2007). Based on an empirical, qualitative, human geographical approach, the present article explores how Chiquitano traditional subsistence agricultural systems are being reconfigured by changing regional and international contexts that drive increasing economic, infrastructural and cultural integration.

First, I draw a brief panorama on existing LULC research in the Bolivian lowlands and present the research methodology. Second, based on secondary data from the available (grey) literature, I introduce general trends associated with the expansion of the agricultural frontier in Santa Cruz and San Ignacio de Velasco and point at the main-associated drivers. Third, I illustrate how Chiquitano producers are being encouraged to alter their traditional land management and productive matrix and to incorporate market-oriented agriculture. Fourth, by deriving characteristic trajectories of change, and their possible spatial expression, I visualize and discuss some profound transformations that Chiquitano communities are undergoing with their integration into the agricultural frontier. The paper finally invites scholars to reflect on how regional and global LULC modelling may address quantitatively ‘invisible’ micro-scale changes, such as those described here. These transformations are indeed significant at global scale, since they bear witness to the rapid and profound reconfiguration in autochthonous populations, their livelihoods and more broadly their cultural values and ways of life.

Investigating LULC changes at agricultural frontiers in the Bolivian lowlands

Frontier regions are complex, contested areas, particularly appropriate for developing innovative conceptual and methodological bridges between disciplines of relevance to LULC Studies. Indeed, agricultural frontiers are characteristically resource- and ecologically rich regions, of low demographic density. They are located at the interface between forest and advancing fronts of land conversion, and land use is typically unsustainable. Agricultural frontiers have often been constructed as empty, peripheral, unproductive land, of strategic importance and up for grabs from the perspective of a remote political and economic centre (Coy & Klingler, Citation2014). This has legitimized the appropriation of land and natural resources by incoming actors, as centrally steered governance regimes pushed new forms of governance, infrastructural developments and market integration (Brand & Wissen, Citation2018; Coy et al., Citation2017; Rasmussen & Lund, Citation2018). The process of colonization, occupation and control of the frontier region often takes place in centrifugal waves (Coy et al., Citation2016) and is associated with profound socio-ecological transformations (Peluso & Lund, Citation2011). As pioneer fronts mature, settlement and economic activity consolidate and formalize, more powerful actors take possession of available land and resources and push less powerful actors to open new pioneer fronts in search of new land (Bastiaensen et al., Citation2015; Fearnside, Citation2008; Neuburger, Citation2003). Typically, customary systems and rights are overridden. This privileges large scale, incoming actors at the expenses of the autochthonous populations, who are progressively excluded from decisions over land, despite their great knowledge of, and experience with, these environments.

In the Bolivian lowlands, the rapid expansion of agricultural land use that radiates from the departmental capital of Santa Cruz de la Sierra has been the primary focus of LULC analysis (e.g., Grau & Aide, Citation2008; Steininger et al., Citation2001a). Research has focused on pioneer frontiers, where ‘intruding’ land conversion process (i.e. deforestation, forest fragmentation) can be detected through remote sensing methods and quantitatively modelled (e.g., Killeen et al., Citation2007; Marsik et al., Citation2011; Redo, Citation2012; Steininger et al., Citation2001b). This has enabled scientists to investigate:

LULC patterns related to a range of driving forces, including bio-climatic suitability, access to market (Müller, Citation2011), policies encouraging in-migration, the construction of road infrastructure (Forrest et al., Citation2008; Redo, Citation2010), land tenure (Paneque-Gálvez et al., Citation2013), changing demographic dynamics, actor constellations and their specific land-use patterns (e.g., Killeen et al., Citation2008; Redo, Citation2013);

Policy contexts and institutional arrangements that have favoured rapid LULC changes (Bottazzi & Dao, Citation2013; Kaimowitz et al., Citation1999; Müller et al., Citation2014; Pacheco, Citation2006; Redo et al., Citation2011);

Plausible directions in future LULC on potential socio-ecological impacts and policy alternatives to avert undesirable futures (e.g., Andersen et al., Citation2016; Armenteras et al., Citation2019; Müller, Citation2011; Sangermano & Eastman, Citation2012; Tejada et al., Citation2016).

Some lowland indigenous populations have managed to secure their own territories, and are in the process of formalizing diverse degrees of autonomous governance to protect their land and natural resources (Tockman, Citation2017). However, if land titling, property rights and strong institutions can reduce deforestation, they can also exacerbate it, as other critical socio-economic and political factors operate in combination (Bottazzi & Dao, Citation2013; Pacheco & Benatti, Citation2015). Further, lowland indigenous populations may actively partake in land conversion. For example, some local actors may informally lease common land secured through the designation of indigenous territories,Footnote5 land that is, in theory, unalienable (e.g., McKay, Citation2018, p. 208). Alternatively, they may support recent forest management strategies that facilitate the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the lowlands (ABT, Citation2017),Footnote6 in keeping with the national development strategy ‘Agenda Patriótica 2025’ (Patriotic Agenda 2025 – Ministerio de Comunicación, Citation2013) and the 2015 Summit ‘Sembrando Bolivia’ (Sowing Bolivia). The latter policy framework has been developed by the central state in alliance with the agroindustrial and cattle ranching sectors (Los Tiempos, 2015; Castañon Ballivián, Citation2015; Colque, Citation2014; McKay & Colque, Citation2016; Tierra, Citation2015).Footnote7

In contrast, lowland indigenous populations who have not managed to secure a (large) territory, like most Chiquitano communities in the Velasco Province, face pervasive land scarcity and rural exodus with population growth (Tierra, Citation2003). This substantially reduces the room for manoeuvre these communities have during the process of integration in the agricultural frontier. In this paper, the local Chiquitano productive systems (i.e. the crop composition, management systems, spatial expression and evolution) serve as an entry point to investigate micro-scale LULC changes, their underlying processes and socio-ecological implications. Changes at household and community levels, which cumulatively only cause minor quantitative impacts on LULC, are indeed difficult to incorporate in low resolution regional LULC models. This is a general methodological caveat related to limited local data and simplistic assumptions on land user groups and their decisions (Alcamo et al., Citation2011; Matthews et al., Citation2007; Schaldach & Priess, Citation2008). The productive matrix is seen here as a tangible proxy indicator for broader socio-cultural changes that are difficult to grasp spatially, let alone quantitatively. What people cultivate, where, and how, give important indications about the underlying local economy, food systems and land management. These changes, in turn, help to understand how indigenous communities are incorporating new lifestyles, knowledge and cultural meanings, blending these with their own, or neglecting local ways in the process. Accordingly, the questions structuring this research are:

How is deforestation and land conversion affecting the East Chiquitania in recent decades?

How does the advancing agricultural frontier alter Chiquitano productive systems?

Which spatial expression may be associated with these micro-scale changes?

What do land use trajectories indicate about broader socio-cultural changes at local scale?

Methodology

Data on current deforestation and more generally LULC changes in the region were obtained through the review of the available scientific literature and strategic planning documents at national, departmental and district levels. Further, a case study on LULC changes and associated future impacts on the District of San Ignacio de Velasco was commissioned within the project and performed by the NGO Fundación Amigos de la Naturaleza [FAN] (Citation2019). This involved (a) mapping of deforestation and LU change, and (b) a Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) study for the selected district. The present work includes some findings from this study.

Empirical qualitative research methods based on Punch (Citation2013) and Yin (Citation2009) were used to perform the case study. Fieldwork core questions were framed based on the following sensitizing concepts: ‘traditional agriculture systems’, ‘market-oriented agriculture’, ‘livelihoods’, ‘regional market integration’ and ‘socio-ecological transformations’. The purpose of the analysis was to capture the diversity of agricultural productive systems and changes during the last decades in Chiquitano communities in the Velasco Province. A detailed actor-analysis was performed for the case study region to identify strategic academic and NGOs partners, who (a) were able to provide key information and context, (b) acted as gate openers to local communities, and (c) facilitated logistical support. A range of secondary data on changes to local productive systems and management was identified during discussions with local key informants. This was complemented by a thorough search for relevant (grey) literature in online depositaries and libraries of (non) governmental organizations performed by the author. These documents were often based on detailed, participatory processes in communities considered in the present work, and provided rich insights on local land management and use. For example, current planning regulations encourage the development of territorial plans at communal level (Plan de Gestión Integral de Bosque y Territorio – PGIBT), which include detailed actor analyses, resource and LU maps, timeline of access to land and communal history.

Fieldwork was carried out by the author during 22 weeks in 2016 and 2018. A broad range of communities was visited before focussing on selected Chiquitano communities, which had characteristic central activities (e.g., agroforestry, pasture, sesame and peanut cultivation). All in all, data were collected for 38 communities, with visits to 15 of them. This helped to identify locally characteristic mixes of agricultural activities. provides an overview of the empirical basis that informs the present work. A number of empirical qualitative methods of data collection were deployed. Detailed insights were obtained through semi-structured individual and group interviews and field excursions with key informants. A total of 75 interviews were carried out with farmers, young people and representatives of local authorities, indigenous people / farmers unions, cooperatives and private agribusinesses. Numerous additional interviews and informal conversations were held with key informants from collaborating NGOs, and academic and governmental institutions. Facilitated discussions in workshop and focus group formats were preferred when sufficient participants could be gathered, in particular with young people and farmers. Finally, non-participant observation was used during visits to specific agricultural plots and during attendance at community and cooperative assemblies.

Table 1. Summary of the empirical basis.

Interviews ranged from 15 min to 2 h, were generally recorded digitally after obtaining consent from interviewees, and transcribed verbatim. Information collected in communities focused on local settlement history, agricultural practices, productive matrix, livelihood strategies, market access and youth employment perspectives. Additionally, expert interviews provided an overview on important policy changes and their implications for food production and forest protection. This empirical basis helped to better understand the local diversity in livelihood strategies, recent changes in indigenous agricultural practice and their potential LULC implications. This was refined for a few selected emblematic communities in detailed conversations and triangulated with field observations and secondary sources of information. Finally, synthetic insights on characteristic changes in agricultural practices in the Chiquitano communities investigated and their possible spatial expression were derived.

Deforestation trends in San Ignacio de Velasco

‘The Santa Cruz agricultural frontier is coming to us.’ It is with these words that a technician of a locally important producers’ cooperative based in San Ignacio de Velasco summarized the current situation in the eastern Chiquitania. This progression, perceived as inevitable, explained, why, after decades of fostering environmentally friendly agroforestry, the organization was considering turning to mechanized agricultural systems. Before considering how Chiquitano communities are changing their land use, I first introduce the study region via a short review of the general context of deforestation and land conversion, based on secondary data from the available (grey) literature.

San Ignacio de Velasco: a dynamic pioneer front at national level

Estimates of forest cover and extent of deforestation in Bolivia strongly vary according to the sources consulted (). Cumulatively, existing data confirm that although forests still approximately cover half of Bolivia’s national territory, their conversion has rapidly accelerated since the turn of the 21st Century.

Table 2. Comparative data on deforestation in Bolivia.

Deforestation is concentrated in the lowlands, especially the Department of Santa Cruz, which has been the target for the expansion of the agricultural frontier since the 1960 s. de la Vega-Leinert and Huber (Citation2019) contextualize the ongoing widespread forest conversion in the Bolivian Chiquitania region and draw a parallel with trends and drivers of deforestation in the neighbouring Brazilian State of Mato Grosso. In both regions, the State played an important role in the integration of forested regions in the national economy via strategic programs for infrastructural development and colonization, and via land allocation to landless farmers. This resulted in rapid deforestation, recurrently associated with dramatic forest fires. Concerning the recent forest fires in 2019, although at the international level Brazil was the focus of attention, preliminary data from Tierra (Citation2019) indicate that fires in Bolivia affected approximately five million hectares of forested areas, ca 3.6 million hectares alone in the Department of Santa Cruz.

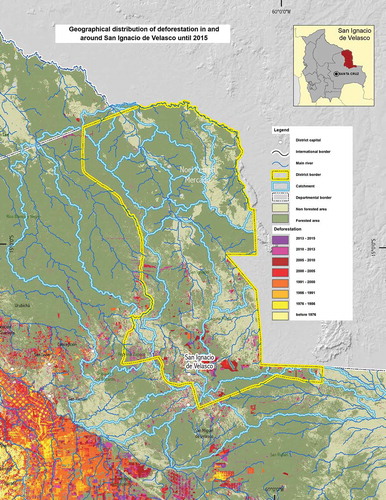

In 2009, 79% of San Ignacio de Velasco, East Chiquitania, was still covered by forests. A large proportion of these forested areas was located within protected areas of importance at national, departmental and district levels (GAMSIV – FCBC, Citation2011). Compared to the Western part of the Santa Cruz Department, deforestation is a relatively new phenomenon in this district (Müller et al., Citation2014). FAN (Citation2016: 76 and ) illustrated how the agricultural frontier has been progressively expanding eastwards in a radiating pattern from the 1970s, reaching San Ignacio de Velasco towards the end of the 1980s. Deforestation data are patchy and lack consistency, and have to be collated with caution. The district management plan indicates that by 2009 ca. 6% of total district area had been deforested (GAMSIV – FCBC, Citation2011). The Forest Administration (ABT, Citation2017) recorded a rapid increase in cumulated deforestation from 27,533 ha (2000–2005), 68,856 ha (2005–2010) to 82,940 ha (2013–2017, the later period only referring to authorized deforestation). FAN (Citation2019), however, has calculated much higher values with cumulative deforestation accelerating by 500% between 2005 and 2018 (from ca 47,000 ha to ca 281,000 ha), and an annual rate of deforestation increasing from ca 3,000 ha/yr to 21,000 ha/yr ( and ). At departmental level, Cuéllar et al. (Citation2012) ranked San Ignacio de Velasco 3rd in terms of forest loss between 2000 and 2010. In 2016, San Ignacio de Velasco reached for the first time the highest rates of deforestation at the national level (MMAyA & ABT, Citation2018).

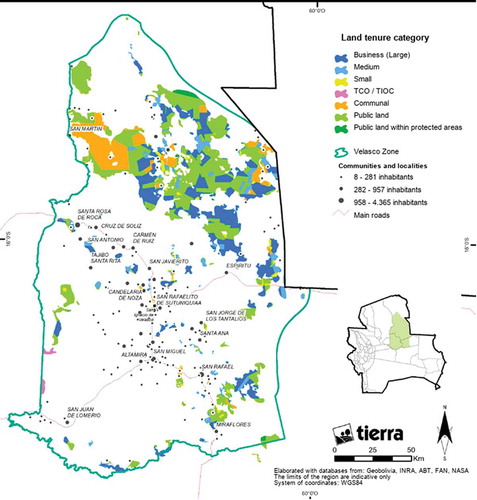

Deforestation follows three distinct patterns, which are closely related to the actors who drive land conversion, and the associated land tenure category (Arima et al., Citation2015; Barbosa de Oliveira Filho & Metzger, Citation2006; Padoch & Sunderland, Citation2013). First, large-scale conversion to pasture is characterized by rectangular fragmentation. This occurs primarily on land located in the vicinity of the Brazilian border, where private property is more common (Cuéllar et al., Citation2012). Second, fish bone patterns of forest clearance occur along main road axes to the west, either on communal (in particular in Andean colonist communities) or private land (Mennonite communities and, increasingly, private agroindustrial farmers). The size of these patterns is closely related to the degree of mechanization of their land users. Third, traditional agropastoral subsistence systems, based on swiddenFootnote8 cultivation, cover a minimal area, primarily in the centre and south of the district. These are concentrated around the district capital, San Ignacio de Velasco, and along the roads that connect the Jesuit Missions which historically structured the settlement of the Chiquitania after the Conquest (Thiele & Nostas, Citation1994).

For FAN (Citation2019), the main drivers of land conversion in San Ignacio de Velasco are infrastructural developments, land conversion for cattle ranching and agricultural purposes in the southern and central part of the district, as well as land allocation to the north, associated with the establishment of new settlements, and forest and mining concessions. These trends are supported through national policies that have spurred the expansion of the agricultural frontier via (1) encouraging land conversion as a strategy to secure land tenure, (2) loosening forest protection regulations, (3) legalizing deforestation, and (4) maintaining controlled fire as a management measure (de la Vega-Leinert & Huber, Citation2019). This is exacerbated by phenomena related to climate change, such as diminishing precipitations, increasing temperatures, and longer, stronger and more frequent droughts, which can induce further land conversion to compensate a lower productivity. For example, prior to the 2019 forest fires, the FCBC issued a warning on the critical meteorological drought, which was affecting the Chiquitania region. Markos (Citation2019) highlighted the positive feedback mechanisms between forest clearance and climate change resulting in accelerated pressure on hydrological and ecological resources. Martínez et al. (Citation2019), in an emergency report, further documented the impacts of the prolonged drought in San Ignacio de Velasco, including the drastic decline in water availability, both for human and animal consumption, and significant losses in harvest, cattle and income: all contributing to seriously affecting the local food security. In this context, it is hardly surprising that the Velasco Province, in particular San Ignacio de Velasco, has been one of the areas most badly hit by the 2019 forest fires. According to estimates from Tierra (Citation2019), 20% of the total area affected in the Department of Santa Cruz is located in the Velasco region.

compares three different sources of information on areas affected by deforestation or fires at three different scales over three different periods, to highlight common trends and points of departure. In all cases, land under private tenure (particularly large properties) is particularly affected by deforestation or fire. The values for affected areas under common tenure (incl. TCO/TIOC) are consistently lower in the lowlands as compared to values at national level. Within the lowlands, deforestation and fires have affected the land allocated to Andean peasant communities more than the land occupied by Chiquitano indigenous communities. However, since incoming Andean populations receive forested land, deforestation is necessarily associated with the establishment of new settlements and surrounding agricultural plots. In the Velasco Province, Tierra (Citation2019) estimated that ca. 70% of the public land available for distribution had been impacted by the forest fires. This appears to be closely related to their location at the current pioneer front of deforestation, in the vicinity of large private properties and new settlements of Andean farmers (see light green areas in ).Footnote9 In contrast, the core of the Chiquitano communities considered in this article (located around the district capital San Ignacio de Velasco, between Altamira and Candelaria de Nossa) do not appear to have been severely affected by the fires.

Table 3. Deforestation in San Ignacio de Velasco (2013–2017) and area affected by the 2019 forest fires in the Velasco Province in relation to land tenure.

Scarcity of agricultural land

With a surface of 48,959 km2 and a projected population of 59,548 inhabitants (1.2 inhabitant/km2),Footnote10 San Ignacio de Velasco controls a vast territory. Nevertheless, the agroecological zonification of the current land use plan (PLUS) originally classified over 68% of the district as Land under Permanent Forest Production (with ca. 35% of this under conservation status), and recommends extensive cattle ranching (alone or in agropastoral systems) in a further 29% (GAMSIV – FCBC, Citation2011). Officially, therefore, land is generally considered unfit for agricultural use, especially under intensive, mechanized systems. In terms of land use, in 2009, 79% of San Ignacio de Velasco area was dedicated to conservation and forestry management, 19% to cattle ranching and 1% under agricultural use. By 2015, both pasture and agricultural land use had nevertheless substantially increased, as illustrated areas in pink and violet in . Precise and updated land use data are not yet available.

Control on land and natural resources is strongly skewed. Private property is most extensive in the South and East, which concentrates most of the land suitable for cattle ranching and agropastoral use. There, Chiquitano communities are generally small (i.e. from ca. 100 to less than 6000 ha/community – Eger, Citation2014; GAMSIV – FCBC, Citation2011). At district scale, Chiquitano communities control only up to 8% of total district land.Footnote11 Chronic (agricultural/fertile) land scarcity among the Chiquitano population has been an historical constant since the development of the Hacienda system (Thiele & Nostas, Citation1994): a situation that has exacerbated since the 1960s, as land increasingly came under the control of complex (trans)national actor constellations, including cattle ranchers, timber and agribusiness companies, Mennonite communities, and, since the 1990s, growing numbers of Andean communities (Colque, Citation2014; Kopp, Citation2015; Tierra, Citation2003).

Precise data on the distribution of land per tenure category are difficult to secure. This is due to poor access to, and transparency in, governmental data on the land titling and allocation process, which was still ongoing at the time the study was carried out. FAN (Citation2019) compared data available for 2009 and 2019 and documented an important increase in the area under common tenure, especially in parcelled communities (i.e. generally those allocated to Andean peasant communities). shows important discrepancies presumably due primarily to inconsistent sources of information and different approaches used to compile data. Thus, while some land under private tenure was reverted to public tenure during the complex process of land titling (Eger, Citation2014; Tierra, Citation2003) and allocated to peasant communities,Footnote12 it appears unlikely that land redistribution alone accounted for the 12% gain in public land and the 18% decline in private land recorded in 2019. Further, pervasive structural inequality in land distribution at national level, numerous superimpositions (i.e. plots being claimed by different communities and/or land owners), and increasing incoming populations and investors have resulted in very dynamic (formal and informal) mechanisms of land acquisition and escalating conflicts over land (Regalsky et al., Citation2015; Urioste & Kay, Citation2005).

Table 4. Estimated land distribution per tenure rights in 2009 and 2019 (FAN, Citation2019).

Empirical evidence of the reconfiguration of Chiquitano agricultural productive systems

Since the Conquest, the ‘traditional’ subsistence system of lowland indigenous people in the Eastern Bolivian lowlands has been fundamentally reshaped by incoming actors. The introduction of extraneous land-use practices resulted in the increasing sedentarization of agriculture (Thiele & Nostas, Citation1994). This transformation process was initiated by the establishment of Jesuit and Franciscan missions in the region and, later, the boom in rubber extraction. This was followed, since the 1990s, with the development of commercial logging of tropical wood and, currently, the expansion of extensive cattle ranching and commercial agriculture (Tierra, Citation2011). At the same time, although local productive systems have persisted, they have increasingly incorporated extraneous elements. In communities which command forest, local agricultural systems combine the extraction of forest products with swidden agriculture, characterized by subsistence cultivation systems in small, dispersed plots used in a threefold rotation system (see also Bermeo et al., Citation2014). Rotation plays a key role in this system, including of crops cultivated on the same plot, of crops between winter and summer cultivation, and between cultivation and lengthy periods of fallow (Vadez et al., Citation2008). This produces a mosaic pattern of LU, which is not as easily detectable through remote sensing as fish bone patterns (Padoch & Sunderland, Citation2013).

summarizes the main categories in Chiquitano agricultural systems encountered in fieldwork together with typical income sources and influencing factors. In the following, I introduce important processes of changes resulting in differentiation in the local production matrix.

Table 5. Generic categories of agricultural productive systems.

Coping with land scarcity

Where land is abundant, population rates low, and fallow periods long enough, labour-demanding swidden cultivation can cover local food needs, with restricted impacts on surrounding forests (Metzger, Citation2003; Van Vliet et al., Citation2012). In San Ignacio de Velasco, however, Chiquitano communities have often very limited land at their disposal. For example, in 2003, the smallest communities could barely provide between one and three hectares per inhabitant, and if a number of communities had over ten hectares per inhabitant, very few could afford more than 30 ha per inhabitant (Tierra, Citation2003). With population growth and time, land scarcity is exacerbated and community land reserves progressively disappear as the young form their own households and establish cultivation plots.

Communities whose livelihood is based on swidden cultivation use rotation as a built-in mechanism to cope with declining soil fertility. The introduction of sedentary agriculture, however, and the structural condition of land scarcity that most Chiquitano communities face have hindered this traditional adaptation strategy. Thus, although since the 1990s vast stretches of land have been allocated to Andean colonists under common tenure, Chiquitano communities have encountered considerable obstacles in their agrarian claims. Except the Indigenous Territory of Bajo Paraguá in the North of the District, Chiquitano settlements have been officially designated as agricultural communities, and their land restricted to that available at the time of registration (Eger, Citation2014). As explained by the leaders of the local Chiquitano Indigenous Association (ACISIV):

“Some communities have received titles for a large territory and few families, but others have been left with a very small territory and many families … and they are surrounded by [private] properties, so that they had no more land to expand [to]. Some have ended up with 250 ha for almost 100 families. That is why [a community can] decide to apply for land for a new [settlement] under the argument of insufficient land. … All inhabitants who have not received land constitute a new community … they will receive 50 ha per person … This is [what] the Central [Única de Trabajadores Campesinos] of intercultural [i.e, Andean] peasants [is doing] … We too are prioritizing communities of original indigenous population, because we see that the communities have too little land.”

Through a process resembling swarming, a group of landless members of the community can seek land to establish a new settlement. Formally, this involves a costly and lengthy legal procedure, which includes the establishment and registration of a legal entity and the application for land to the National Agrarian Reform Institute (Centro de Documentación e Información Bolivia [CEDIB], Citation2008). Moreover, key informants from agrarian and development NGOs active in the area indicated that the land market in San Ignacio de Velasco is highly dynamic, with many external actors attempting to secure land, either formally via purchase or land allocation, or, via informal negotiations and deals with actors, who could facilitate land allocation (including agricultural workers’ unions and indigenous organizations). However, while in San Ignacio de Velasco a number of new Chiquitano communities are currently establishing and initiating their land use, the ACISIV leaders insisted that they had to do substantial lobby work to convince communities to apply for more land. The young Chiquitano population, in contrast to the incoming Andean colonists, were not necessarily envisaging a future on the land and sought alternative professional perspectives outside of rural communities and away from agriculture.

Nevertheless, the availability of land per se does not secure the maintenance of agriculture. Where communities are close to urban centres, large cattle ranches or the Brazilian border, off-farm agricultural (as cowboy) or non-agricultural employment (e.g., trade, transport, construction, tertiary employment) becomes the main income source, especially for young people. With ageing farmer populations, productive systems may thus become residual and primarily centred on households’ garden plots, typically tended by the women. In remote communities, agricultural land may revert to permanent fallow and secondary forest expand. However, well-connected communities may, instead, progressively urbanize. For example, as the district capital, San Ignacio de Velasco, grows, available land surrounding the city is rapidly vanishing. Nearby communities are turning into residential areas and access to agricultural land is becoming more difficult. A cooperative technician, for example, explained how his family’s plot in the district capital was rapidly gaining value as residential land, so that it could be sold at a good price to build a better house in a nearby community. Because his wife was originally from the latter community, she could use her right to apply for land before the ‘community’s book was closed.’ Indeed, communities collectively decide how many households may have access to land, and how much. This expression refers to a phase when a given community does not accept any further members and stops internal land distribution.

Diversifying the productive matrix

Chiquitano indigenous systems have undergone a process of adaptation, which has been strongly steered by public administrations and organizations of international cooperation and NGOs, who have for decades set the pace for rural development from the 1970s onwards within the CORDECRUZ (Corporación de Desarrollo de Santa Cruz) and PLADERVE (Plan de Desarrollo Regional de Velasco programs (see for, e.g., Bienert, Citation2004). These have first focused on diversifying the economic basis of Chiquitano communities by introducing new activities. Public programs have thus encouraged the development of extensive communal cattle ranching in Chiquitano communities, where native pasture is abundant (minimum five hectares per head of cattle) and water supply can be secured through the digging of rainwater reservoirs. Communities either receive cattle on a rotation basis (i.e. head of cattle must be returned after a number of years) or as a non-conditional subsidy. Cattle acts as a living savings account, with sales forming a core household income. Beef is therefore only rarely consumed locally. Cattle hurdling has become an important strategy to improve living standards, and better off farmers with sufficient resources acquire their own heads of cattle and establish their own pasture. In terms of land cover, natural and improved pasture can play an important role in the local land-use succession, replacing annual crops as soil fertility declines, thereby extending agricultural use and delaying fallow periods.Footnote13 Decisions on pasture area and total number of heads of cattle, nevertheless, are made at communal level, depending on land availability, so that when land is scarce, communities may prohibit this activity.

Today, cattle ranching forms the backbone of the local economy of many Chiquitano communities, but only accounts for about 1% of the approximately half a million head of cattle of the district herd, while large-scale properties concentrate the lion’s share (GAMSIV – FCBC, Citation2011). Community cattle ranching is, therefore, highly dependent on the surrounding large private cattle ranches, which provide employment and act as intermediaries (by buying community-bred young bulls to fatten them up). Nevertheless, cattle ranching is for indigenous communities a hazardous endeavour, with declining water supply as illustrated by the impacts of the 2019 drought (Martínez et al., Citation2019). Water shortage is not only related to changing climate conditions but often also to land and water appropriation by large private properties. Key informants indeed mentioned how water supply in Chiquitano communities can be substantially affected by unlawful damming of temporary rivers in surrounding private cattle ranches (see also Tierra, Citation2003).

In the region, typical household plots under subsistence farming are approximately one hectare in size, i.e. the area that a family can work manually, with some form of mechanization needed to augment cultivated area to produce surplus. Public programs have therefore supported the intensification of indigenous agricultural systems to facilitate a transition from subsistence to surplus agriculture. Programs sought to increase cultivated area, raise the productivity of local food staples (e.g., rice, maize) and complement them with crops for local consumption and sale (e.g., beans). They have further promoted the basic transformation of crops to increase added value (e.g., manioc flour) and decouple sales from peak harvest period.

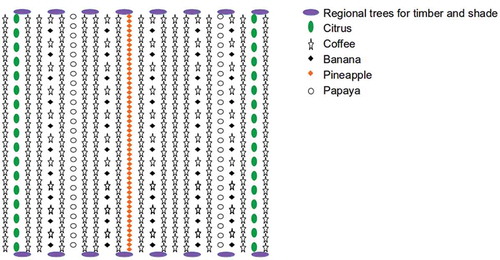

Further, from the mid-1980s, these programs supported the establishment of agroforestry systems, combining annual (e.g., maize, beans, rice) and biennial (e.g., manioc, pineapple) crops while perennial crops (e.g., coffee, bananas, plantains) and trees (citrus, fruit, nut, shade and timber) (e.g., ). These polyculture systems have been particularly valued by international cooperation and development and conservation NGOs active in the region. They can be managed agroecologically in compliance with the departmental and district land use plans and are perceived as a valuable alternative to restrict deforestation related to shifting agriculture. Further, they can combine subsistence crops with high-value commercial crops for sale to regional and international markets and animal husbandry, thereby contributing to secure livelihoods all year around. The implementation of this approach is well illustrated in the case of a local coffee cooperative, MINGA, which has received financial support from a combination of public and NGO sources at global (FAO), European (German cooperation), national and district levels to build the necessary productive capacity and fulfil export quality standards (MINGA, Citation2018). Additionally, specific projects have in recent decades encouraged the extraction of non-timber forest products (e.g., cusíFootnote14 and copaibo, Chiquitana almond, açaí) as an alternative source of income (Guzmán et al., Citation2015; De Urioste et al., Citation2015, Citationn.d.). In this context, the collection of wild nuts and fruits and their potential for domestication and cultivation are being explored (e.g., Chiquitano AlmondFootnote15). Further, basic processing infrastructure has been put at the disposal of producers groups (often women), which are to be managed collectively. The aim is to achieve added-value products, which can be commercialized at regional scale (e.g., in form of oil, frozen pulp, roasted almond).

Nevertheless, systems based on agroforestry and the extraction of forest products encounter critical problems in the case study area. Their maintenance requires substantial labour, while lack of appropriate management can increase environmental risks. For example, in recent years, banana cultivation has been affected by the spreading of the Panama disease (Fusarium wilt). Also, banana and coffee-based polycultures are particularly susceptible in times of drought, especially if leaf and shade management is poor. Plantations are, therefore, regularly devastated by extreme drought and forest fires (Bienert, Citation2004; Martínez et al., Citation2019). Further, while appropriate agricultural extension can significantly increase productivity and harvest, critical bottlenecks in producers’ organizations and multiple structural constrains prevent successful commercialization and appropriate income. These obstacles include in particular internal governance and management problems at community and cooperative levels, lack of transport or processing facilities, market saturation and high cost of certification and controlling.Footnote16 These conditions contribute to the recurrent boom and bust phases associated with the integration of small producers to national to global markets. Typically, the establishment of new plots results in periods of high production. As long as market demand is not saturated, intermediaries can offer ‘good’ prices, but as all producers focus on the same crops, oversupply brings prices and incomes down, resulting in many producers abandoning these activities.

Incorporating green revolution approaches

A second main aim of rural development programs in San Ignacio de Velasco has been to raise agricultural productivity, typically via the adoption of the so-called ‘technological package’, which facilitates access to seeds, mechanization, extension services and agrochemical, and more recently, organic inputs. Additionally, subsidies may help to pre-finance labour. These public programs originally encouraged the introduction of commercial annual crops to be cultivated in monoculture (e.g., peanut). More recently, private actors, primarily from the agribusiness sector (e.g., Lactos and AgroExport) have entered the arena and provided farmers similar services under the modality of credit by sales contract, conditional on payment at harvest. This has resulted in the increasing specialization in new cash crops (e.g., sesame, chia, soybean), this time clearly oriented towards global markets.Footnote17 Initially, from the end of 1990s, this trend characterized agricultural activities in Mennonite colonies and new settlements of Andean farmers. In the last decade, however, these schemes have been increasingly spreading also to Chiquitano communities. In terms of land use, (semi)-mechanized, commercial agriculture has implied the further expansion of cultivated area and the conventional intensification of management systems. To facilitate mechanization, public programs have encouraged the modality of the Chaco Bloque to concentrate individual agricultural plots on collective plots cumulating 10 ha to facilitate tractor work.

The trend towards conventional intensification in commercial agricultural systems is associated with substantial ecological impacts, including accelerated deforestation, rapid soil degradation, the proliferation of weeds, and decreasing soil fertility after three to 5 years under annual cultivation. Further, fire is still an important aspect of plot preparation, and local populations have substantial knowledge on how to apply this practice effectively (McDaniel et al., Citation2005). Nevertheless, increasing frequency and severity of meteorological droughts, combined with the less careful use or even deliberate misuse of fire by other actors (in particular cattle ranchers) can sharply increase the risk of uncontrolled fires, including in Chiquitano communities (Martínez et al., Citation2019; Tierra, Citation2019). Finally, where enough land is available, plots are put to fallow and cultivation displaced to other, often forested/fallow areas. Where farmers have sufficient financial means, the increased application of agrochemical treatments can delay and shorten fallow periods, with critical implications for the long-term vegetational recovery through ecological succession in cultivated plots.

For critiques from development and conservation NGOs and international cooperation, the spreading of conventional, mechanized agriculture in the region is especially worrying because it contravenes and thus undermines the existing land management plan, which excludes intensive agricultural practice on Land under Permanent Forest Production. Furthermore, it increases the dependency of Chiquitano farmers on public subsidies and private agribusiness actors, who control access to productive resources (via the ‘technological package’), while dictating prices. For example, communities can yearly receive local subsidies for specific projects including digging water reservoirs, road repairs, etc. Once the community has incorporated a cultivation system based on the Chaco Bloque modality, the yearly subsidy may become solely used for mechanization, hindering other important communal projects.

Changing practice and perception of agriculture

Over the last four decades, public programs in San Ignacio de Velasco have contributed to spur a spiral of local development. For example, the ‘Asociación de Grupos Mancomunados de Trabajo’ (Association of groups of collective work – a Chiquitano producers association, precursor of MINGA) has channelled many resources with important results. The agricultural production in participating communities has improved in volume and quality, processing and commercialization capacity has been built, and connections to local and regional markets have improved. Surplus and commercial agriculture have in turn increased incomes, which households could invest in diversifying productive activities and improving basic services (in particular housing, diversified diets, education and health). In this general context, generations of local agricultural technicians were formed, which have driven a progressive change in agricultural practice in Chiquitano communities. Moreover, since the 1990s, the cultural and ethnic composition of San Ignacio de Velasco has been substantially transformed, with the arrival of incoming Andean colonists, supported by the successive governments of the Movement towards Socialism Party (Movimiento al Socialismo – MAS).

This ongoing process of socio-cultural change has important LULC implications. Thus, while Chiquitano farmers are perceived, and tend to view themselves, as more respectful of a traditional agricultural practice that is compatible with local conditions, many increasingly seek to emulate the accomplishments of Mennonite and Andean commercial farmers. Comparisons between the ‘hard-working, successful, and strong-minded Andean peasants’ and the ‘peaceful, laid back, naive’ Chiquitano were recurrent in interviews. The Chiquitano leader of a community located in the vicinity of new settlements stated:

“They [the Andean colonists] are winning. They have more knowledge, more will to work. They are more independent. This is a key thing that we need to emulate. The people here [the Chiquitano] are selling their labour force. They are poorer. That is why they do this.”

A consultant who set up and monitored an agroforestry program stated:

“[we have] to face this new paradigm of peasants coming from the West with a clear culture of deforestation and with an ethic more focused on work, who work harder, [cultivate more] hectares, [produce] more tons, etc. How can the local indigenous people compete? Do we relegate them to a past century, in another period of history? Or do we [help] them become competitive? Because if they don’t die, they will become absorbed by this [new] culture. … ”

Mechanized agriculture becomes not only a promise of wealth for small producers, who want to secure a steady income, but also the means to rescue a bankrupted subsistence agriculture and a symbol for successful integration into modern agriculture. Thus, in 2016, the then president of a coffee cooperative was strongly steering the organization towards the incorporation of mechanized agriculture. To this end, the cooperative acquired a second-hand tractor by channelling funds which were originally planned to secure payment of coffee harvests to cooperative members. At the time, the administrator believed that the cooperative was ‘basically sacrificing the organization to pursue a dream.’ In a later visit in 2018, it became clear that the acquired tractor had indeed broken down soon after its purchase causing important losses to the cooperative. A former German cooperant summarizes the situation as follows:

“[the small producers] always look up to the cattle ranchers, the Mennonites, the big soybean producers and all this. Of course this is very attractive, because these are the rich [producers]. And they think: ‘well, that’s it. We will do the same and become rich, or at least become a little better off’. But in the communities this does not work so well.”

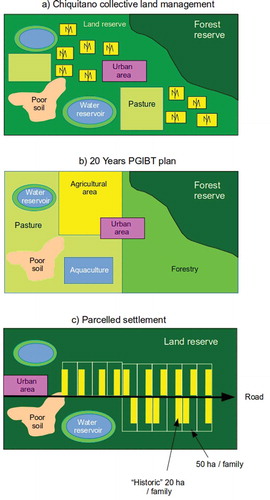

Changing land management approaches

Traditionally, in Chiquitano communities, land management is decided both at collective and household levels. Decisions concerning land/forest reserves, water and pasture management and collective plots (for community gardens and Chaco Bloque) are made at the community level. At the same time, individual households decide how much land they can cultivate on a yearly basis. Family plots are typically dispersed, often radiating from the urban core of the community, where houses and collective infrastructure are located (). Plots are only temporarily allocated to a household until they are left to revert to fallow. This system appears at first egalitarian since each household can access communal land. However, in practice, farmers with more resources (to pay for labour, mechanization or heads of cattle) can allocate themselves more land, at least as long as communal land reserves are sufficient.

For common land under Permanent Forest Production, strict regulations apply. A household may have a maximum of 20 ha of land under cultivation for life, although land allocation per household can reach a maximum of 50 ha in lowland regions (i.e. the remaining 30 ha are to be kept as reserve) (Müller et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, as noted above, the majority of Chiquitano agricultural communities are far too small to afford individual households such large plots. Further, households can yearly convert up to two to three hectares, with permits needed both for deforesting bigger plots and for using fire to prepare the land for sowing. Although permits are often applied for at the community level, they still imply the investment of time and resources for application. Futher, if authorizations are not received in time, farmers may not be able to prepare their plots before the onset of the raining season, thereby jeopardizing the chances of a good harvest. To ease this bureaucratic process, communities may elaborate an integral forest and land management plan (Plan de Gestión integral de Bosques y Tierra [PGIBT]) valid for a period of 10 years, after official approval by the local forest protection administration (ABT) (). This replaces the need for the application of individual permits, although yearly plans still need to be submitted and approved. Collective decision-making has been enshrined as a key approach in the methodology recommended for the elaboration of the PGIBT. Nevertheless, the process is costly and complex. Indeed, one important requisite, among others, is a detailed geo-referenced inventory of land, social and natural resources. Therefore, until 2018, only about 10 plans had been completed (out of the official 116 communities registered at the last demographic census). Although nine of these had been approved, none of the concerned communities had completed the requested yearly plans. The administrative formalization of land management has thus effectively created new insuperable hurdles for most communities.

Moreover, the land allocation process is progressively introducing a radically different conceptualization of land management itself. Indeed, new settlements tend to be parcelled, i.e. each land tenant receiving an individual plot of maximum 50 ha, typically on either side of a central road (). Although in keeping with a household-centred approach characteristic of Andean and Mennonite colonists (resulting in fish bone deforestation patterns), this is altering the traditional Chiquitano conceptualization of collective land, based on an ever-changing mosaic of dispersed plots radiating from a central urban core. Communities can themselves decide how they wish to structure their land use; however, public administrationsFootnote18 and foreign NGOs may impose new land planning modalities in their agricultural extension programs. Thus, in recent years, the World Wide Fund (WWF) for Nature in collaboration with the local authorities and a key local producers’ cooperative have applied the modality of Chaco Bloque to establish banana and coffee-based agroforestry system with the overall goal of promoting the diversification of the income basis following a sustainable intensification approach. The purpose of the concentration of individual plots into a Chaco Bloque was to avoid deforestation and ease fire control management. Nevertheless, participating communities did not necessarily have at their disposition the 10 ha of contiguous cultivated land needed to participate. Although the project did not authorize deforestation (in keeping with the conservation focus and sustainable intensification approach pursued by WWF), fallow land had to be included to obtain this surface, resulting in shortened fallow periods. Moreover, while land management in Chiquitano communities is traditionally decided at the communal level, agricultural work is performed and managed at the household level. Key informants from local development NGOs, reflecting on past projects, have highlighted a recurrent mismatch between the expectations embedded in extraneous projects and their implementation locally. For example, these projects often have collective management as prerequisite (e.g., of Chaco Bloques, community gardens, animal husbandry, processing equipment), which effectively only lasts during the project life, with participating households dividing plots, animals or tools thereafter, often resulting in the discontinuation of the projects over the long term.

Discussion: indigenous productive systems at a crossroad

Chiquitano indigenous communities in San Ignacio de Velasco have in recent decades been encouraged/driven to three main trajectories of change (): (a) specialize in a core activity (cattle ranching, commercial agriculture or forestry), (b) diversify into (certified) agroforestry systems or (c) progressively abandon agriculture as a main source of livelihood. These trajectories have a number of direct implications in terms of LULC. For example, these include the expansion, contraction or abandonment of cultivated area, changes in the composition and species richness of the productive systems per se (e.g., ranging from traditional food staples to specialized cash crops), in the management type (e.g., ranging from conventional to certified organic, from monoculture to agroforestry), and its intensification. The derived trajectories of change may apply to the whole community, a producer cooperative, a cattle-raising group or individual households. They are conditional on a broad range of structural conditions combined with factors that affect farmers’ agency (). Indeed, as demonstrated above, Chiquitano communities integrate the agricultural frontier from a position fraught with obstacles. Among these are in particular chronic land scarcity, dependency on public programs, lack of alternative employment opportunities and of knowledge related to incoming forms of agricultural and land management.

Table 6. Factors affecting changes in producers’ adaptive capacity.

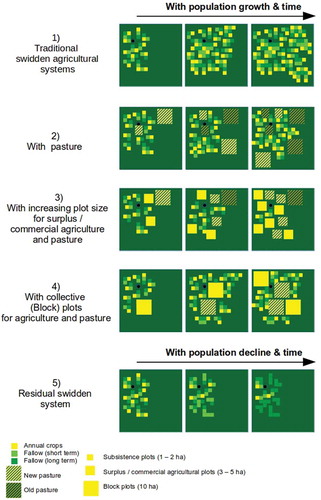

illustrates possible patterns of spatial-temporal changes in traditional Chiquitano agricultural subsistence systems associated with the above trajectories, including:

the progressing disappearance of land reserves as population grows and plots multiply,

the introduction of pasture, both on collective and individual plots,

the expansion of plots for surplus and commercial agriculture (whether in monoculture or polyculture),

the concentration of land for mechanized agriculture (e.g., on Chaco Bloque), and

the progressive abandonment of agricultural (land), as communities lose their young labour force.

An additional dimension of change is the cyclicity related to rotation in LU. In , different succession paths are illustrated. After a phase of land conversion, during which forested areas are cleared for subsistence crops and natural pastures are used for grazing, comes a phase of intensification, which can include a progression to commercial monoculture, agroforestry and/or improved pastures. This is then followed by a phase of extensification as soil fertility diminishes and pastures degrade. Land is then put to fallow, and the agricultural activities are displaced onto another plot, where a new cycle starts. With declining land reserves, communities have had to adapt patterns in shifting cultivation, by incorporating agricultural extension methods and/or shortening fallow periods. Public and NGO programs have consistently supported the adoption of low-cost, locally adapted agroecological fertilization and pest management methods, but agrochemical inputs are also routinely used, where resources are available. Changing patterns of land use in Chiquitano communities are in keeping with the gradual transformation process swidden agricultural systems are undergoing globally. Available literature emphasizes the close relationships between local factors, such as land and labour availability, crop mix and fallow length, public policy and broader socio-economic changes driving the incorporation of subsistence systems in globalized economies (Coomes et al., Citation2000; Vadez et al., Citation2008; Hecht, Citation2010; Colque et al., Citation2015; Turner et al., Citation2017; and other articles in this issue). With the conversion to permanent (i.e. sedentary) agriculture, the introduction of mechanization and cash crops, local communities, often living in chronic poverty, can rapidly increase their income basis, at great socio-ecological costs however (Van Vliet et al., Citation2012).

The generic patterns of change presented above help to visualize the complex and multi-faceted adaptation process Chiquitano communities are undergoing with their progressive integration into the agricultural frontier. This drives both quantitative changes (e.g., in surface cultivated, crop diversity and agricultural cycle) and qualitative ones (e.g., individual and communal approaches to land, its management, its cultural meaning). The following six narratives frame various ongoing directions of change Chiquitano communities and producers take in the study region (adapted from de la Vega-Leinert, Citation2017):

‘Emulating the Andean colonists and Mennonites’ follows the main productivist discourse that underlies the ‘Sembrando Bolivia’ strategy. Producers are encouraged to embrace progress via conventional green revolution technologies with the ultimate goal of integrating global agricultural commodity chains.

In ‘Green market alternatives’ state programs, NGOs and increasingly also the agribusiness sector, promote the concept of ‘the other frontier’ (Programa de las Naciones Unidades para el Desarrollo [PNUD], Citation2008) that focuses on high-quality crops produced in ecologically friendlier agricultural practices. This may include regional forest products (e.g., Chiquitana almond, açaí, palm hearts, copaibo, cusí), cash crops incorporated into agroforestry (e.g., coffee, moringa, cashew) or monoculture, which may nevertheless be cultivated in organic systems (e.g., chia, sesame). Market niche potential may be enhanced by incorporating certification schemes.

‘Food and energy sovereignty’ seeks to establish a diverse productive matrix to (1) provide healthy and nutritious food for local consumption, (2) foster the use of renewable (wind, solar based) energy sources that enable a regular water supply for micro-scale horticulture and animal husbandry, the processing of crops into added-value products and their storage, and (3) ensure decent livelihoods through sales at local and regional markets (Caballero Leiva et al., Citation2016; Mamani et al., Citation2016).

In ‘Local Entrepreneurs’, social differentiation processes enable specific individuals, who position themselves in strategic roles (in local authorities, organizations and unions) to gain key competences and channel resources to construct local ‘empires’. For example, income from agricultural activities (cattle, mechanized monoculture and certified coffee plantations) can be enhanced by the construction and renting of recreation and tourism facilities, and a salary as civil servant or consultant in a local cooperative.

In ‘Leaving the land’, young people leave the community temporarily or permanently to raise income in non-agricultural employment. In farming communities, women and elderly become overrepresented. As population diminishes, agricultural activities reduce and concentrate in the core urban area. The more remote fields tend to be abandoned, plantations are unkept, resulting in secondary forest growth, which may become more susceptible to forest fires. Where communities are close to economic centres, they may become residential areas, and agricultural land replaced by urban development and infrastructure.

‘Remote forests as corridors of informality’. Transboundary regions, especially in the vicinity of protected areas, have a formal economy based on community forestry, the commercial extraction of forest products and nature-based tourism. Informal income may be enhanced by allowing right of way to illegal trafficking activities.

These narratives can contribute to develop regional land-use scenarios for quantitative LULC modelling exercises that can better take into account the profound transformation lowland indigenous populations are undergoing with their integration into the agricultural frontier.

Conclusions

The present work used the materiality of indigenous productive systems as an entry point to analyse micro-scale changes often overlooked in regional to global LULC modelling. Sequential steps followed involved:

deriving broad categories in productive systems,

identifying generic trajectories of change and possible constraining factors,

visualizing characteristic patterns of LU change, and

formulating narratives that frame current directions in local indigenous land use.

These steps help to explore the spatial expression of what Turner et al. (Citation2017) call the ‘local manifestation of globalization.Footnote19’ In combination, they can contribute to create an interface between qualitative and quantitative LULC studies to better understand the profound transformation Chiquitano communities are undergoing with their integration into the agricultural frontier. Ultimately, this approach can prompt a societal discussion on the future of indigenous livelihoods and the role of exogenous and endogenous approaches to land management therein. In this respect, the present work supports ongoing efforts to better apprehend the multi-dimensionality and complexity of socio-ecological transformations in rural areas in spatially explicit approaches. It can enrich Fischer et al. (Citation2017)’s framework to describe social-ecological systems and evolving states, according to their performance to provide food security and preserve biodiversity. It can contextualize Augstburger & Rist’s (Citation2019) approach to highlight the importance of indigenous and agroecological food systems in the provision and maintenance of diverse and resilient agricultural landscapes in the Bolivian lowlands.

The traditional swidden subsistence characteristic of indigenous communities is being profoundly transformed both quantitatively and qualitatively. However, the associated LU changes are not easily detectable through remote sensing as are typical ‘fish-bone’ patterns of deforestation, characteristic of commercial farmers in pioneer fronts. Generic insights derived from detailed empirical work can contribute to make visible and better represent complex spatio-temporal patterns of micro-scale LU in regional models. Controversy on the value of qualitative case studies in land use conceptualization and LULC modelling has primarily focused on methodological issues (centred for example, on scale, indicators, underlying data, comparability and transferability) (see for, e.g., Fischer et al., Citation2014; Green et al., Citation2005; Phalan et al., Citation2011). Beyond the imperatives related to quantification, detailed field studies point at the necessity to raise critical core normative questions related to the profound transformations of local, indigenous subsistence livelihoods and ways of life globally (de la Vega-Leinert & Clausing, Citation2016, and articles in this issue). Questions include: Who has the right to decide which productive matrix, land use management or rural development approach is ‘the right one’? Who bears the consequences of this decision? Is it socially acceptable to see certain ways of life, and the knowledge needed to maintain them, disappear with integration into the dominant commercial agriculture mode? To which extent can local populations shape this integration process and the process of hybridization of their cultures and productive basis? And further, to which extent are endogenous approaches developed by local populations to harness their integration into the agricultural frontier compatible with sustainable land use? To address these issues, the blending of LULC studies with political ecology and an environmental justice perspective is a promising avenue to pursue. This interestingly shifts the attention from land-use change processes per se to encompass issues of right and access to land and natural resources, and underlying societal injustice (Corbera et al., Citation2019).

‘Progress’ has been imported in remote rural areas, in particular via public policy, international cooperation, NGOs and commercial actors, who often emphasize a dearth of local solutions. This is particularly clear in frontier regions, where traditional agriculture persists next to incoming, intensive agro-industrial systems (Barbier, Citation2012). Rural areas are to be either modernized and absorbed within the dominant culture, or depopulated to enable ecological regeneration. Despite 14 years of official post-neoliberalism under the MAS governments and eloquent discourses on Mother Earth and its enshrinement in the 2009 Constitution of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, lowland indigenous people are de facto induced to ‘modernize’ and incorporate global commodity chains. Some adapt successfully, most remain in precarious living conditions. All become income-driven, dependent on external inputs and markets. This process undermines local food-sovereignty and knowledge about biodiversity that have buffered transitional crisis for centuries, while it contributes to the economic and socio-cultural assimilation of rural communities.

Indigenous mobilization has played a critical role in putting Evo Morales in power. It is recurrent and multi-faceted, although, in the last decade, it has been increasingly violently sanctioned, when challenging extraction. Since the repression of the March for the lowland indigenous territory and National Park Isiboro Secure (TIPNIS – Territorio Indígena y Parque Nacional Isiboro Secure), ethnic fractures between Andean and lowland indigenous have come to the surface (Delgado, Citation2017; Wanderley, Citation2018). Further, relationships between lowland indigenous and the white and mestizo elites are complex. Indeed, the traditional elites, on the one hand, have openly supported lowland indigenous populations against the incoming Andean peasants, and, on the other, sought to undermine their territorial claims (Weber, Citation2013). In recent years, the Velasco Province has become the hotspot of national deforestation, a tragic trend exacerbated by the August 2019 fires and current political turmoil. It can be speculated that a return to a right conservative government at the new presidential election originally planed for May (but postponed due to the Corona virus crisis ongoing at time of publication) will condone policies supporting extraction, the expansion of the agricultural frontier and undermine local protest. In that scenario, it is probable that the political basis of the MAS government in the lowlands (i.e. Andean colonists and coca farmers – Achtenberg, Citation2016) would lose its current prerogatives. In this context, whether current efforts towards decentralization and local autonomy can help lowland indigenous populations to reclaim control over their land, their territories and define their own trajectory of change remains to be seen.

Figure 1. Geographical distribution of deforestation in, and around, San Ignacio de Velasco until 2015 (Fundación Amigos de la Naturaleza, Citation2019). Reproduced with permission from FAN.

Figure 2. Cumulative Deforestation in San Ignacio de Velasco until 2018 (adapted from Fundación Amigos de la Naturaleza, Citation2019).

Figure 3. Areas affected by the 2019 forest fires according to land tenure classes (Tierra, Citation2019). Reproduced with permission of Tierra.

Figure 4. Example of an agroforestry system (adapted from Ayala Becerra, Citation2016).

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to key informants, in particular from Tierra – Oriente, Centro de Investigación y Promoción del Campesinado (Santa Cruz), Instituto para el Desarrollo Rural de Suramérica, the San Ignacio de Velasco District, Fundación para la Conservación del Bosque Chiquitano, Asociación de Grupos Manconumados de Trabajo MINGA, Centro de Documentación e Información Bolivia, Gobierno Autónomo de San Ignacio de Velasco and all interview partners who generously gave their time and expertise. Thanks are extended to Valeria Nelva Catoira Ordoñez for the transcription of the audio files, Dorna Lange for language editing and the two anonymous reviewers, whose suggestions greatly improved the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

This paper is based on empirical, qualitative data collected through participatory methods, field excursions and observations. Audio files, transcripts and coding results are archived by the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Currently, 60 TIOCs (Territorio Indígena Originario Campesino) exist, cumulating ca. 11.6 million ha, i.e. ca 11% of total national land area. TIOCs are territories allocated to recognized Pre-Conquest, autochthonous populations. Andean peasant and lowland indigenous populations, who obtained territories, have the right to control land and renewable natural resources therein according to the provisions specified by law. With the 2009 Constitution, the former TCOs (Tierra Comunitaria de Origen) were renamed TIOC to expand the category ‘original’ and establish all Pre-colonial indigenous and peasant communities as right holders. (Paye et al., Citation2010; Tierra, Citation2011).

2. These comprise 43.8% of the Land under Permanent Forest Production at national level (Tierra de Producción Forestal Permanente – TPFP). Under the Supreme Decree No. 26075, all primary forest areas have been placed under this category. Under the Master Departmental Land Use Plan (PLUS – Plan de Uso de Suelo, the only land use foreseen in TPFP areas is forestry). Land use classes are attributed based on a zonation, which takes regional pedological, vegetational, topographical and climatic factors (Müller et al., Citation2014; Paye et al., Citation2010; Proyecto CUMAT, Citation1985).

3. I choose ‘district’ as a translation for ‘municipio’, as in the lowlands, municipios are generally very large and the direct translation (municipality) may be misleading. The district of San Ignacio de Velasco has a surface of over four million hectares.

4. Traditional lowland populations rely on subsistence-oriented agriculture and the extraction of forest and aquatic resources (Thiele & Nostas, Citation1994).

5. See, for example: Hoy Bolivia (4 April 2017). Indígenas destapan tráfico de tierras en la reserva Guarayos. Retrieved from: https://www.hoybolivia.com/Noticia.php?IdNoticia=229305 (4 February 2020).

6. But this could also result from the fragmentation of the institutions representing lowlands indigenous populations (Bottazzi & Dao, Citation2013).

7. Political turmoil exacerbated by the catastrophic forest fires in 2019 forced President Morales to resign in November 2019 and flee Bolivia in exile. In the mist of vivid national and international controversy, former second vice president of the Senate Jeanine Áñez assumed the interim presidency and new elections have been set for May 2020. It is too soon to comment on how these drastic events will impact policies from the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) government that actively encouraged the expansion of the agricultural frontier. Retrieved from The Guardian (29 November 2019) https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/nov/24/bolivia-anez-regime-violence (6 February 2020).

8. Swidden, slash-and-burn and shifting agriculture are different terms for traditional subsistence systems characteristic of tropical regions (Van Vliet et al., Citation2012).

9. Tierra (Citation2019) documented 164 permits bestowed to new settlements cumulating ca 227,000 ha.

10. The last population census was in 2012. The population of San Ignacio de Velasco was then estimated at 52,362 inhabitants (INE, Citation2018).

11. This excludes the indigenous territory of Bajo Paraguá located in the north of San Ignacio de Velasco.

12. Thus, in 2008 ca 100,000 ha in San Ignacio de Velasco were allocated to three communities belonging to the landless movement, which faced strong opposition by both neighbouring private ranchers and Chiquitano communities, who claimed part of the land allocated as theirs (Caballero Leiva, Citation2013).

13. In contrast, conversion from pasture to agriculture in traditional systems requires a period of fallow. Key informants in the case study area, nevertheless, mentioned that private cattle ranchers are starting to diversify by converting pasture land into mechanized agriculture, a trend in keeping with the evolution in Brazil (de la Vega-Leinert & Huber, Citation2019).

14. See for example, GIZ (18 September 2018). Cusi Chiquitano – Aceite extra virgen. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C9yFyVx6itQ (19 February 2020) and Ebertseder (Citation2018).

15. Dipteryx alata (Vogel) (Vennetier et al., Citation2012).

16. A detailed analysis of these bottlenecks is being prepared in a companion paper. For a first overview, see De la Vega-Leinert (Citation2017) and de la Vega-Leinert, Brenner & Stoll-Kleemann (Citation2016).

17. This is particularly the case of contracted agriculture in the oilseed sector. Asociación de Productores de Oleaginosas y Trigo (22 May 2017) La agricultura por contrato en Bolivia. Retrieved from http://anapobolivia.org/noticias.php?op=1&id=1302 (6 February 2020).

18. At the time of fieldwork, the local official of the forest administration, while explaining the land management regulations, only referred to parcelled communities. Key informants later confirmed that many officials of central administrations tend to ignore the Chiquitano pattern of land use.

19. Turner et al. (Citation2017) investigated how households in South Bolivia have reconfigured their economies, land use and agrobiodiversity based on detailed ethnographic work.

References

- Global Forest Watch. (2020). Country specific data - forest change - bolivia. Retrieved from https://www.globalforestwatch.org/ (30.04.2020)

- ABT. (2016). Procedimiento de autorización de desmonte hasta 20 hectáreas para pequeñas propiedades y propiedades comunitarias o colectivas para actividades agricolas y pecuarias con sistemas productivos integrales. [Directriz ABT-005/2016]. Autoridad de Fiscalización y Control Social de Bosques y Tierra.

- ABT (2017). Con la apertura de la frontera agrícola y la moderniziación d ela ganadería el Beni puede convertirse en la región más rica de Bolivia. . Santa Cruz, Bolivia: Autoridad de Fiscalización y Control Social de Bosques y Tierra.

- ABT (2018). Desmonte de gestión 2013 a gestión 2017. CE-ABT-SIV-0905-2017. Autoridad de Fiscalización y Control Social de Bosques y Tierra.

- Achtenberg, E. (2016). Evo’s Bolivia at a Political Crossroads. NACLA Report on the Americas, 48(4), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2016.1258282