ABSTRACT

Nearly one hundred years ago, a group of Mennonites left the prairies of Manitoba for the deserts of Northern Mexico. Since then, Mennonites have created over two hundred agricultural colonies across Latin America, spanning nine countries and seven biomes. In this paper, we provide the first continental-scale map and account of Mennonite expansion in Latin America over the last century. We show that Mennonite colonies today cover an area exceeding that of the Netherlands, having expanded through the conversion of uncultivated land to agriculture in remote areas. We discuss the implications of Mennonite expansion for the study of frontier land-use change. We argue that Mennonite farmers differ from both peasant and capitalist farmers, two categories of agents commonly featured in studies of frontier land-use change, in ways that have made them more likely to take a pioneering role in agricultural frontiers. We finish by proposing some avenues for future research.

1. Introduction

Over the last century, the global land area used for agriculture has increased massively (Foley, Citation2005), not least in Latin America, where staggering expansion rates have been reported for crop- and pasturelands in recent decades (Graesser et al., Citation2015). The appropriation of space for food, fiber, and fuel production has propelled agricultural frontiers in which uncultivated land is turned into croplands and pastures, thereby integrating remote areas into a national and global agricultural economy. In Latin America, increasing demand for agricultural commodities, pressure to accommodate growing rural populations, and state territorialisation efforts through frontier settlement, have all contributed to the conversion of millions of hectares of intact forests to agriculture (Gibbs et al., Citation2010).

To understand local dynamics of agricultural frontier expansion, it is necessary to examine the logic of the agents that drive them. Latin American agricultural frontiers have often been characterised as either populist frontiers (Browder & Godfrey, Citation1997; Pacheco, Citation2005), driven by small-scale peasant farmers, or corporatist (Browder & Godfrey, Citation1997), capitalist (Pacheco, Citation2005) or neoliberal frontiers (S. B. S. B. Hecht, Citation2005), driven by large-scale, capitalist farmers. Although both dynamics can be present in a given frontier (Barbier, Citation2012; Pacheco, Citation2012), peasant and capitalist farmers represent contrasting modes of decision-making. Peasant farmers typically respond to a logic centered around household reproduction, expanding their cultivated area primarily in response to changing needs of the family unit, although some degree of market integration is common (Caldas et al., Citation2007; Van der Ploeg, Citation2013). Capitalist farmers, on the other hand, seek to maximize return on capital through various means, including the capture of changing economic rents in remote and uncultivated areas (le Polain de Waroux et al., Citation2018).

In this paper, we turn our attention to a group of agents that seems to defy these categories and that, in spite of its disproportionate influence on agricultural expansion in several Latin American countries, has received relatively little scrutiny in studies of frontier land-use change. That group is Low German Mennonites, a socio-religious community tracing its origins back to 16th-century western Europe, which, since the migration of some of its members from Canada to Mexico and Paraguay almost a hundred years ago, has generated over 200 new agricultural settlements, or colonies, scattered across the continent. In what follows, after a brief summary of early Mennonite migrations, we review the expansion of Mennonite colonies in Latin America and discuss its implications for the understanding of frontier land-use change. In doing so, we aim to contribute to both the empirical and the conceptual basis for the study of agricultural frontiers. Empirically, we propose the first complete map, account, and family tree of the expansion of Mennonite colonies over their first hundred years in Latin America. Conceptually, we propose that these colonies form a distinct yet significant class of agents in the ‘frontier ecosystem,’ one that operates following a logic not quite like that of either peasant or capitalist farmers, and which, given its influence in the development of Latin American agricultural frontiers, deserves to be better understood. We propose a research agenda to that effect at the end of this paper.

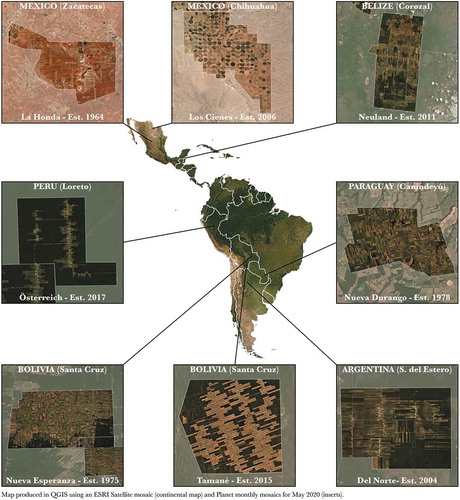

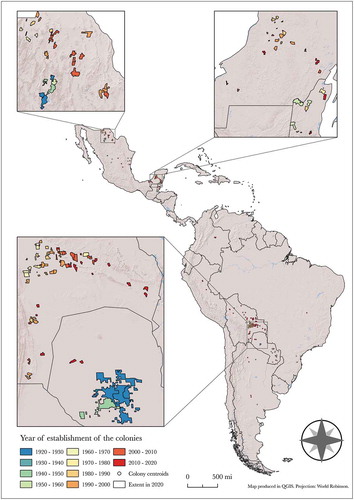

Our account of Mennonite colony expansion is based on a variety of sources including published academic literature, multiple books published within the Mennonite community (e.g., Bergen, Citation2017; Giesbrecht, Citation2018; Giesbrecht & Klassen, Citation2015; Penner, Citation2014; Schartner & Schartner, Citation2009), online sources (e.g., https://gameo.org/), and a 16-year digital archive (2004 to 2020) of the Mennonitische Post, a bi-monthly German-language newspaper aimed at the Low German Mennonite diaspora in the Americas that carries news, travel reports, and reader letters from colonies across the region. Drawing on these sources, we identified every Mennonite colony in Latin America, its date of establishment, and the origins of its first settlers, and reconstituted, where possible, the history, motives, and mechanisms behind its creation. We produced a map of Mennonite colonies based on a combination of existing maps, textual information, and visual interpretation of satellite imagery. To do this we started by consolidating and digitizing maps published in various books and atlases (e.g., Giesbrecht, Citation2018; Penner, Citation2014; Schroeder & Huebert, Citation1996; Warkentin, Citation1987) and in the Mennonitische Post, as well as maps produced by colony administrations and knowledgeable individuals. We then used visual interpretation of satellite images to update or create polygons, combining the use of the history function in Google Earth Pro (which displays yearly Landsat mosaics from ~1984 to 2016 at a 30-m resolution) with images from Planet Explorer (high-resolution image mosaics for 2016–2020). We used expansion trends and settlement patterns to identify or update the boundaries of colonies ().

2. From the Low Countries to Canada

Mennonites have long been known as pioneer farmers. This Anabaptist Christian denomination, named after the Dutchman Menno Simmons (ca. 1496–1561), emerged in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, coalescing around ideals of nonviolence, adult baptism, and separation from ‘the world.’ A strong attachment to land and farming also became a defining characteristic over the years, as did the use of Low German (Plautdietsch). The Mennonites’ early history in Europe was marked by a series of migrations. The trajectory of most relevance to this paper led a group to migrate from Flanders to Friesland, then to West Prussia in the 16th century (around the city of Gdańsk, then called Danzig), to the steppes of Ukraine in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and finally to Canada in the late 19th century (Loewen & Nolt, Citation2012, pp. 5–7). Each of these migrations was driven in large part by the changing attitudes of national governments towards what came to be called the Privilegium: the demand for Mennonites to be exempted from military service, the swearing of civil oaths, and, increasingly over the years, national education. While these hard-working colonists were initially welcomed by states seeking to consolidate their sovereignty over remote territories, their demands for differential treatment grew increasingly intolerable as states moved from territorial consolidation to nation-building (Cañás Bottos, Citation2008, pp. 68–69). Inevitably, the moment would come when these exemptions were revoked, forcing Mennonites to either assimilate or leave.

This cycle of settlement and uprooting continued after Mennonites had crossed the Atlantic Ocean. In 1919, amidst growing pressure to integrate English public schools and increasing suspicion towards the German-speaking Mennonites’ exemption from military service in the wake of World War I, a group of conservative Mennonites decided that migration was ‘the only way out’ (Gingrich, Citation2014; Sawatzky, Citation1971, p. 27). Delegations were sent to Latin America, and Mexico and Paraguay, two countries whose presidents were willing to honour the Privilegium, were chosen as resettlement destinations. This led to a massive relocation in the 1920s. From then on, as will be described below, Low German Mennonites would expand not only within these countries but also into multiple others, forming an ever-increasing number of new colonies in remote agricultural frontiers.

3. A century of Mennonite expansion in Latin America

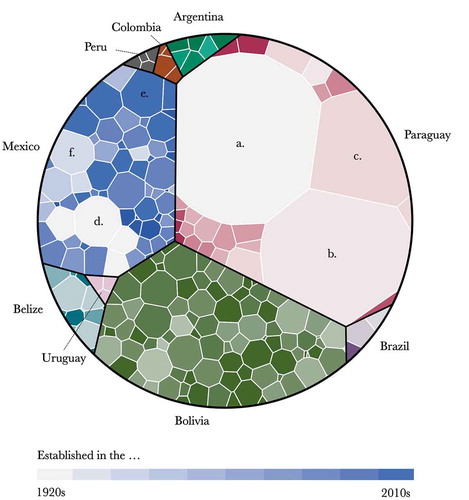

Today, our dataFootnote1 indicate that 214 Mennonite colonies cover a total area of about 3.9 million hectares in Latin America, more than the total land area of the Netherlands (, ; at least 14 additional colonies have been dissolved). This estimate does not reflect land owned by Mennonites individually outside colonies, which in some areas like the Paraguayan Chaco represents another several hundred thousand hectares. In what follows, we attempt a brief country-by-country summary of the process of expansion that has led to this current state of affairs in Latin America. In that account, we necessarily simplify: we omit, for example, multiple failed attempts at creating new colonies, the constant back-and-forth of migrants between colonies after their creation, and the many thousands of Mennonites who have returned to Canada, particularly from Mexico and Paraguay (over 40,000 until 2004 (Janzen, Citation2004) and likely many more today). Discussing all these movements in one paper would be impossible, and as our interest lies in the process of expansion, we focus on events of colony creation.

Table 1. Summary of Mennonite colonies by country

Figure 2. Map of Latin America Mennonite colonies. A vector file of all colonies is available for download under the following link: https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/I4FEQZ

Figure 3. Land area of the colonies, by country. Each bubble is a colony. The total land area of the colonies is ~39,000 km2. Letters designate colonies with an area greater than 500 km2: Menno (a), Fernheim (b), and Neuland (c) in Paraguay, and Manitoba (d), Los Reyes (e), and Ojo de la Yegua (f) in Mexico. The figure was created using the package ‘voronoiTreemap’ 0.2.0 in R

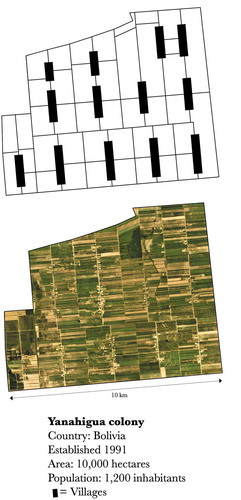

Before we proceed, a few words about the nature of these colonies are in order. Mennonite colonies in Latin America are distinct from other settlements in their morphology and organization. Centered around a church and school, they typically take the form of one or several ‘street-villages’ or Straßendörfer, consisting of a row of farmhouses evenly spaced on either side of a road, each housing one family (). Life revolves around mixed farming, the main livelihood for the large majority of the Mennonite population. Each village is headed by an elected leader called Dorfschulze (Village leader) who manages local affairs, while the colony is represented by one or more Vorsteher (Colony leader). Religious leaders called Prediger, Diakone, and Ältester (Preacher, Deacon, and Elder or Bishop), elected for life, exert important influence on colony affairs. Small colonies may have as few as a dozen families organized along a single village, while larger colonies can reach several thousands of individuals in dozens of villages, with multiple schools, churches, and Vorsteher. Numerous colonies reject some modern technologies, which are seen as corrupting influences. The most conservative colonies reject the use of rubber tires on tractors and of telephones and the connection of houses to the electricity grid, among other things. Members of more progressive colonies find it normal to own smartphones or pick-up trucks and have TV. Diversity does not stop at technology adoption: colonies (and sometimes, villages within colonies) further differ in their positions towards education, labour, language, and more generally, relationships to the outside world.

Figure 4. Typical structure of a colony (col. Yanahigua, Bolivia). Evenly-spaced, linear “street-villages” are connected by a grid of country roads, with narrow agricultural plots extending outward from each village

3.1 Mexico

The first Mennonite colonies in Mexico were created in the 1920s by Canadian Mennonites fleeing what they perceived as a threat to their way of life, as the Canadian government reneged on its earlier promise of guaranteeing freedom of religion and education (Loewen, Citation2008; Sawatzky, Citation1971, p. 27). These colonies, founded in the desert lands of the northern states of Chihuahua (col. Manitoba, Santa Clara, Swift Current) in 1922 and Durango (col. Nuevo Ideal) in 1924, attracted an estimated 8000 migrants between 1922 and 1929, or over 13% of the total Mennonite population in Canada at the time. Canadian Mennonites found in President Álvaro Obergón’s post-revolutionary Mexico a government eager to develop agriculture and assert its territoriality in the North. Obregón was therefore willing to accommodate their demands for the privileges under threat in Canada in exchange for a commitment to cultivating these marginal lands (Dormady, Citation2014). The first settlers acquired large extents of land for these original colonies and therefore had plenty of room to grow for the next quarter of a century. More Canadian Mennonites came in 1948, creating two more colonies in Chihuahua (col. Las Manzanillas and Los Jagueyes). However, after several years, land in the original colonies became scarce and the Manitoba colony, one of the three colonies established in 1922, created its first of many ‘daughter colonies’ not far to the north (col. Ojo de la Yegua, also called Nordkolonie). From then on, almost all new colonies in the country would be the result of endogenous growth within Mexico (see family tree in SI1).

As population grew, the Chihuahua colonies generated numerous daughter colonies, first locally, then also in other states. Thirty-one Mennonite colonies now cover over 650,000 hectares in the state of Chihuahua, though not all of that is cultivated. By comparison, the total cultivated area in that state was 2.6 million hectares in 2017 (INEGI, Citation2017). Meanwhile the Nuevo Ideal colony in Durango expanded first by creating daughter colonies in the neighboring state of Zacatecas (col. La Batea and La Honda). Then, in the 1980s, agricultural extension agents visiting Nuevo Ideal reported that large quantities of land were for sale in the dry forests of the Yucatán peninsula, fifteen hundred kilometers to the south-east (Bergen, Citation2017, p. 8). Nuevo Ideal residents, facing increasing land scarcity, were eager to find new outlets for growth, so they went to see it for themselves and in 1983 they created Nuevo Ideal’s first daughter colony in Yucatán, Yalnón. This was followed by Chavi, a daughter colony of La Batea, in 1986. The move implied a drastic transition from a desert area receiving under 450 mm of rainfall per year, to one with over 1000 mm/year (Karger et al., Citation2017). From these beginnings, the Yucatán peninsula became a major focal point of expansion, particularly for more conservative groups. In 2020, there were 22 colonies in the peninsula. In the state of Campeche alone, Mennonite colonies spanned close to 70,000 hectares, or about 8.5% of the total area cultivated in that state in 2017 (INEGI, Citation2017). Mennonites are also said to have pioneered soybean agriculture in the region (Bergen, Citation2017, p. 83).

As they created new colonies across the country, Mexican Mennonites also started expanding abroad (). Settlement in Mexico had never been without its challenges, particularly in the northern part of the country. In addition to land scarcity and rising land prices making it more difficult for young households to establish themselves as farmers, frequent and prolonged droughts (particularly acute in the 1950s) made rainfed farming unpredictable, which pushed farmers to adopt irrigation, a much more cost-intensive proposition. On top of that, there were recurrent signs that the tolerance of the Mexican government for the privileges granted by Obregón was wearing off. One of these was the threat of inclusion in the national social security system in 1955, which led to a first wave of migration to Belize. There was also growing pressure towards modernization and adoption of new technologies, decried by the more conservative elements in the colonies, and which itself partly emerged from pendulum migrations of Mexican Mennonites to Canada and the US for work as a result of their difficulties in Mexico in the 1950s (Nobbs-Thiessen, Citation2020, p. 96). In the 1990s, the degradation of economic conditions for farmers under neo-liberal reforms added to these pressures (Dormady, Citation2014), all of which helped make Mexico into a major exporter of colonists to other countries. In addition to Belize, Mexican Mennonites moved in large numbers to Bolivia and Paraguay in the late 1960s and Argentina in the 1980s and 1990s (). In the 2000s, further droughts, groundwater scarcity, and the threat of narcotrafficking-related violence compounded these challenges in the northern Mexico colonies, leading to a new wave of land search and migration to Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia.

3.2 Belize

The first colonies in Belize were founded in 1958 by Mexican Mennonites from Chihuahua. The Belizean authorities, aware of the growing unease in Mexico, had invited a delegation in 1955 and later offered to grant incoming Mennonites the full privileges they were seeking (Plasil, Citation2017). This offer was welcomed by groups concerned that their negotiations with the Mexican government to be exempted from the social security system were stalling (Sawatzky, Citation1971, p. 334). Mennonites coming from the Chihuahuan desert built three new colonies (col. Shipyard, Spanish Lookout, and Blue Creek) in a moist tropical forest that received over 1500 mm of rain per year. The rain, while welcome, brought its own challenges. One colonist interviewed by Tanja Plasil and Carel Roessingh recounts: ‘We knew nothing, we came from a dry land – everything was different here … the horses drowned in the mud’ (Roessingh & Plasil, Citation2009, pp. 52–53). All subsequent colonies created in Belize were derived from these original ones, with the exception of a couple of very small settlements created by Canadian and American Mennonites, which have all but disappeared today.

Several of these daughter colonies were created by conservative dissidents dissatisfied with increasing modernization and adoption of technology in the mother colonies. This was the case of Barton Creek, created in the late 1960s, which became an outlet for the most conservative members of the core colonies and later generated its own daughter colonies (col. Springfield, Pine Hill, Bird Walk, Roseville, and Agua Viva) as a response to land shortage (Roessingh, Citation2007). Little Belize (est. 1979) and Indian Creek (est. 1988), served a similar purpose as an outlet for conservative Mennonites from the Shipyard colony (Roessingh & Boersma, Citation2011). This combination of land scarcity and an aversion to creeping modernization led some to emigrate internationally to Bolivia (forming col. Nueva Esperanza in 1975), Paraguay, and recently (in 2017), Peru.

3.3 Paraguay

The same outmigration of Canadian Mennonites that originally led to the creation of the first colonies in Mexico also resulted in the birth of the first Mennonite colony in South America. In 1926, col. Menno was established in the Paraguayan Dry Chaco, in an area characterized by dry woodlands and savannahs and rainfall typically around 900 mm/year, more than 400 km away from the capital city Asunción, with no road connecting the two and barely any settlements in-between. The creation of Menno was followed by that of Fernheim nearby in 1930 by a group of Russian Mennonite refugees fleeing persecution from the Soviet Union. The two groups were quite different in multiple respects: while the Menno settlers, a conservative group, were in search of greater religious purity, the Fernheim group had left a prosperous life behind against their will and ‘interpreted their flight and resettlement as a tragedy’ (Eicher, Citation2019, p. 130). The hardships of the early days led many families to return to Canada over the years (M. W. Friesen, Citation2009). Some members of Fernheim, discouraged by the hostile environment of the Dry Chaco, turned to the more amicable climate of Eastern Paraguay, between the Humid Chaco and the Atlantic Forest, where they created the Friesland colony in 1937. Russian Mennonite refugees would form two more colonies in 1947, one in the Chaco (col. Neuland) and one in the East (col. Voldendam). New groups of Canadian Mennonites seeking to escape modernization joined them soon after, creating the colonies Bergthal and Sommerfeld in 1948. After a twenty-year hiatus, a new wave of colony creation in Eastern Paraguay was spurred by Mexican Mennonites responding to land scarcity, rising land prices, and perceived threats to their way of life in Mexico (Penner, Citation2014). Four colonies were founded from the late 1960s onwards by Mennonites from Chihuahua, and one by Mennonites from Durango. A final group of migrants to Paraguay were conservative Old Colony and Amish Mennonites from the United States and Belize, who created five small and isolated settlements in Eastern Paraguay in the 1960s and 1970s, two of which have since been dissolved.

Because land was abundant in Paraguay, these colonies mostly expanded locally through land acquisitions, rather than by creating daughter colonies in other regions. The Chaco region, in particular, had plenty of land for sale at low prices. As a result, the Chaco colonies were able to grow massively – Menno, for example, grew from about 55,000 hectares in 1926 (Kleinpenning, Citation2009, p. 5) to 420,000 ha in 1995 (Schroeder & Huebert, Citation1996, p. 150) and 700,000 ha in 2007 (U. Friesen, Citation2007). Some local daughter colonies, however, were created in Eastern Paraguay near but separate from the mother colonies Bergthal (Neu-Bergthal, est. 1989), Río Verde (Río Verde del Este, est. 2006), and Sommerfeld (Neu-Sommerfeld, est. 2010). In the 2010s, two Eastern Paraguay colonies (Nueva Durango and Río Verde), unable to expand locally, generated two new daughter colonies in the far reaches of the Chaco, towards the Bolivian border (SI2).

The Mennonite colonies of Paraguay were instrumental in the development of the country’s agricultural sector. In addition to becoming the country’s major producers of dairy products after a road to the capital city was completed (A. Hecht, Citation1975), their expansion in the Chaco in particular paved the way for later investors – Europeans, Brazilians, Argentines, and others – whom Mennonites provided with know-how, infrastructure, and services (Vázquez, Citation2013, pp. 112–122). Mennonites were also active participants in the country’s soy boom in the 1990s and 2000s (Correia, Citation2019). Altogether, our map suggests Mennonite colonies today control about 1.8 million hectares in Paraguay, or 4.5% of the national territory. To this must be added the hundreds of thousands of hectares of land owned privately by Mennonites outside the colonies, which in 2010 already brought that number closer to 8% (Giesbrecht & Klassen, Citation2015, p. 157). Since Mennonites constitute 0.45% of the population of Paraguay, they thus control close to twenty times more land than average Paraguayans.

Paraguayan colonies also produced their share of dissidents, following the familiar pattern of modernization and differentiation common throughout Low German Mennonite society (Cañás Bottos, Citation2008, pp. 71–77). Many of these would move to Bolivia, where they became participants in the prodigious expansion of Mennonite colonies into the country’s lowlands.

3.4 Bolivia

Bolivia, the ‘refuge of conservative Mennonites’ (Schartner & Schartner, Citation2009), hosts the most Low German Mennonite colonies in Latin America – close to one hundred today – with new ones appearing each year. These colonies have been major contributors to the expansion of agricultural frontiers into the Eastern Lowlands (see map in SI3), an area that sits at the limit of the Dry Chaco and the Chiquitano dry forests and is characterized by relatively abundant rainfall (around 1200 mm/y) that decreases east- and southwards.

A first and relatively minor wave of Mennonite migration to Bolivia was initiated by dissidents from the Chaco colonies in Paraguay (Menno and Fernheim) concerned with changes in education (Giesbrecht, Citation2018, p. 143) and frustrated with ‘a rigid cooperative system’ (Nobbs-Thiessen, Citation2020, p. 89). They were joined by a few Canadian families from northern Alberta fleeing modernization and worldliness (Bowen, Citation2001). These people formed five colonies around the regional capital Santa Cruz de la Sierra between 1954 and 1967, four of which were later dissolved as members moved on to other colonies or returned home.

The real impulse for Mennonite expansion in Bolivia came later from Mexico. Having heard of a few groups of Paraguayan Mennonites settling successfully in Bolivia, and aware that the president was keen to attract foreign farmers, the Chihuahua colonies sent delegations to negotiate conditions of establishment with the Bolivian government. Their agreement resulted in the creation of four major colonies in 1967–8, covering over fifty thousand hectares of land (col. Riva Palacios, Santa Rita, Sommerfeld, and Swift Current). Immigration from Mexico continued after that, with new colonies created by Mexican Mennonites at a pace of about two colonies per decade. Almost all of these immigrants came from Chihuahua, with the exception of one colony formed in 1996 by Mennonites from La Batea (Zacatecas). Most of them were formed in the area east of Santa Cruz de la Sierra.

Paraguayan Mennonites made a return to Bolivia in the mid-1990s, when conservative members from eastern Paraguay seeking an escape from modernization and land scarcity at home created a first colony in the lowlands (col. Hohenau), followed by several more during the next decade. Most of these colonies were created in the area east of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, with the exception of three colonies created by people from Nueva Durango in the more isolated Chaco region. Other, more modest contributors to Mennonite expansion in Bolivia were Canada, with three small colonies (two of them now dissolved); Argentina, with one colony in the Chaco; and Belize, with two colonies (col. Nueva Esperanza and Belize) in the Lowlands. The first of these two, Nueva Esperanza, is remarkable for its initial degree of isolation: when it was established in 1975, the colony was 250 kilometers away from the nearest developed agricultural areas. It wasn’t until the 2000s that other farmers came to cultivate surrounding areas.

A look at the map ( & SI3) suggests four broad directions of expansion within Bolivia. The main trend has been an eastward expansion, fuelled both by migrants from other countries – notably from Belize in the case of Nueva Esperanza – and by endogenous growth, the latter being responsible for the more recent developments toward the Brazilian border. A second trend is represented by southward expansion toward the dry Chaco, which started with daughter colonies of the Bolivian Riva Palacios colony (col. Pinondi) but soon involved colonies created by groups of migrants from Eastern Paraguay, Argentina, and Northern Mexico. These colonies have recently started generating their own daughter colonies locally, expanding south- and eastward into the Dry Chaco woodlands. A third trend is represented by a cluster of daughter colonies emanating from the original Bolivian colonies, which started to develop in 2005 in the area of Santa Rosa de la Roca, in the northeastern Chiquitania region. A final trend is one of expansion into the tropical grasslands and forests north of Santa Cruz, as far as 700 kilometers away from the original colonies. With a couple of exceptions, that expansion was the result of endogenous growth.

Altogether, Bolivian Mennonites today farm upwards of one million hectares in the Bolivian lowlands, mainly in the department of Santa Cruz (about 875,000 ha). Besides this tremendous spatial footprint, Mennonites were also a major force behind the rise of soybean farming, which has become the most important crop in the lowlands (Nobbs-Thiessen, Citation2020, p. 212).

3.5 Argentina

The relatively few Argentine Mennonite colonies in existence today all have their origin in Mexico. Nueva Esperanza, was created in 1986 in the semiarid Espinal shrublands of La Pampa province by migrants from the states of Chihuahua and Zacatecas. Cañás Bottos (Citation2008) explains that wariness about growing educational and military demands from the Mexican state played a role in this migration, as did land scarcity, difficulties with irrigated agriculture due to the rising price of fuel, and, in La Honda (Zacatecas), modernization. As Nueva Esperanza’s population grew beyond its capacity to expand in area, younger households moved north and created two daughter colonies in Santiago del Estero province in the Dry Chaco, where migrants from Nuevo Ideal (Durango) had created another colony in 1996. More recently, land scarcity in Northern Mexico, water issues, and narcotrafficking violence have prompted Mexican Mennonites to consider Argentina once again as a potential destination. A group from Chihuahua founded a new colony (El Tupá) in the province of San Luís in 2014, and as of early 2020, another group was about to set up another one nearby. With about 55,000 hectares altogether, Mennonites still only have a very modest footprint for a country as large as Argentina’s. The same is true of Brazil and Uruguay.

3.6 Brazil and Uruguay

The history of Brazil and Uruguay’s Mennonite colonies is distinct from that of most other Latin American countries. The first wave of migration was one of Russian Mennonite refugees who founded a series of settlements in the Krauel river valley, west of the German town of Blumenau in the state of Santa Catarina. Witmarsum, the name of one of the settlements, came to be used as the name for the area as well. This settlement had difficulties from the start, being remote and hard to clear (Schroeder & Huebert, Citation1996), and people soon moved out. Many of them moved to the city of Curitiba, and some to two new colonies – (Neu) Witmarsum, close to Curitiba, and Colônia Nova in Rio Grande do Sul. There were several attempts to expand and create new colonies, but these failed, and Brazil never experienced the sort of Mennonite expansion seen in Bolivia or Paraguay.

The same is true of Uruguay, where three small colonies were created in the early 1950s by Russian Mennonite refugees, but never produced any daughter colonies. Recently, however, Mennonites from Chihuahua, in their search for new opportunities, re-ignited interest in Brazil, and created a first new colony in 2015 in the state of Bahia (California). It is too early to tell whether this colony will be successful and incentivize other movements to the region, but as of 2020, reports were positive.

3.7 Peru and Colombia

This panorama wouldn’t be complete without including very recent yet significant developments in Peru and Colombia. Mennonite colonies were absent from Colombia until recently. Delegations of people from the Chihuahua colonies started visiting the country in search of land around 2014, and after surveying multiple areas, they settled on a location in the department of Meta, in the wet Llanos savannah. The first families moved in 2016 close to the town of Puerto Gaitán and formed the Liviney colony. This colony had promising beginnings, and three more colonies have been created since, for a total of over 28,000 ha. These are relatively progressive migrants, driven out of northern Mexico by a combination of land scarcity, increasing difficulties with irrigation, and search for new opportunities. Untypically, the land they purchased was already developed farmland, although they had to build new roads to connect it.

By contrast, the new Mennonite colonies that have appeared in the tropical rainforest of Peru in recent years (Sierra Praeli, Citation2020) were created by conservative groups from Bolivia and Belize seeking isolation from worldly influences and modernization, as attested by their choice to relocate to the remotest corners of the country. After a failed attempt in 2014 that forced them to relocate, families from the Bolivian colony of El Cerro founded three colonies in 2017 – one south of the Amazonian city of Pucallpa (col. Masisea), and two further to the north (col. Vanderland and Österreich). In parallel, Belizean Mennonites from the colony of Little Belize moved near the latter two, forming a colony simply known as Belize. As of early 2020, two more Amazonian colonies were planned by people from Belize and Mexico. As with Brazil, it is impossible to tell whether new settlements in Peru and Colombia will be successful in the long run and provoke the arrival of more colonists. If recent history is any guide, however, it seems very reasonable to assume they will.

4. Factors In The Creation Of New Mennonite Colonies

Let us turn to a brief exploration of the causes of Mennonite migrations and colony establishment. Starting with factors that drive Mennonites out of existing colonies, the role of population growth and land scarcity cannot be understated. High fertility rates – large families are the norm – combined with small land parcels and a strong attachment to farming as a livelihood have inevitably led to land shortages, making it hard for young households to establish themselves as farmers within the colonies. This issue is sometimes resolved locally by acquiring new land close to the colony, as in the Paraguayan Chaco. Where local expansion is not feasible, Mennonites have often resorted to the creation of new colonies further afield. When doing so, because they almost always move in groups, Mennonites usually seek large blocks of land. In the first migrations to Mexico in 1922, for example, an important factor was the availability of large extents of land that latifundistas facing expropriation after the revolution were eager to sell (Will, Citation1997).

Other pressures on farming include structural factors influencing the viability of agriculture, such as changes in commodity prices or in other conditions of production. In Mexico, for example, multiple colonies in the state of Chihuahua have been facing water shortages, adverse agricultural policies, and severe droughts (Dormady, Citation2014; Gingrich & Preibisch, Citation2010), while farmers moving in recent years to Colombia invoked the high costs of irrigation as one of the reasons for their move (‘La poderosa congregación,’ Citation2018). Some have also cited soil exhaustion, particularly in Bolivia, where it is blamed on the rejection of modern agricultural technology in conservative communities (Kopp, Citation2015; Loewen & Nobbs-Thiessen, Citation2018).

Another frequently invoked reason is the existence of real or perceived threats to identity and cultural persistence. Such threats may come from changing attitudes of national governments towards Mennonite demands for separate treatment – the Privilegium or, where no Privilegium has been officially granted (e.g., in Argentina, Brazil, Peru, and Colombia), the informal promises made by some governments to respect Mennonite ways. This was the case with the migration from Canada to Mexico, but also with that of Mexican Mennonites to Belize, which as mentioned above was triggered by the threat of being incorporated into the Mexican social security system (Plasil, Citation2017; Roessingh & Boersma, Citation2011). Similarly, people leaving Mexico for Bolivia in the late 1960s and for Argentina in the late 1980s did so in part out of concern for the state’s increasing military and educational demands, and when Argentina decided that children born in the country had to be taught in Spanish using material provided by the state, several families moved to Bolivia (Cañás Bottos, Citation2008). Because of the national reach of these threats, resulting migration tends to be international.

Threats to cultural persistence also arise locally. Colonies are often located so as to minimize exposure to worldly influences (SI4), ‘close enough so as not to make their products unmarketable due to transport costs, but far enough in order to attain a level of isolation that would restrict everyday travel to town, especially for youngsters’ (Cañás Bottos, Citation2008, p. 72). Over time, however, the surroundings of most colonies end up developing, partly as a result of the Mennonites’ own activities, which undermines their attempts to remain separated from the world. Early migrants from Canada to Mexico, for example, were concerned about ‘everything turning English’ around their Canadian colonies (Bowen, Citation2001, p. 467). Those who later migrated from Mexico to Bolivia and Argentina reported that Mexican Mennonites’ ‘acceptance of pick-up trucks, cars, electricity and other aspects of modern life had breached the practice of separation from the world’ (Cañás Bottos, Citation2008, p. 220). This apparent paradox of Mennonites as settlers in search of isolation and as engines of modernization and frontier development has been raised repeatedly in the literature (e.g., Goossen, Citation2016).

The adoption of technologies deemed unacceptable by the more conservative members of a community, such as rubber tires on tractors (as opposed to steel wheels), is a recurrent theme. Rubber tires make it easier to use tractors to travel to nearby towns, increasing the risk of exposure to external influences (car ownership is banned in conservative colonies). Loewen and Nobbs-Thiessen recount a conversation with a man who moved in 1967 from Mexico to Bolivia: ‘The religion we have is that you don’t work with rubber tires,’ he says, ‘and the people started to work with them, and everything fell apart and we left’ (Loewen & Nobbs-Thiessen, Citation2018, p. 177). In Belize, Roessingh and Bovenberg report that a conflict over the adoption of mechanical agricultural equipment in the colony of Spanish Lookout led to the departure of 30 conservative members of the community in 1966 (Roessingh & Bovenberg, Citation2018). In Bolivia, most colonies created by international migrants were (at least partly) the result of such disagreements (SI5).

Finally, the increasing threat of violence has emerged in recent years as an important driver of migration out of Northern Mexico (Gingrich & Preibisch, Citation2010). Although violent episodes in Mexico had contributed to migrations before, for example, to Nova Scotia (Canada) in the 1980s (Pauls, Citation2004), a burst in narcotrafficking-related violence since the mid-2000s has become a ubiquitous concern for Chihuahuan Mennonites.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Mennonite colonies have expanded dramatically in Latin America over the last century. In some regions, like the Paraguayan Chaco, the Chihuahuan desert, or the Bolivian lowlands, they have become a major influence on the development of agricultural frontiers, not only because of their direct spatial footprint, but also because of their influence on the subsequent development of these regions’ agriculture. Indeed, Mennonites have frequently taken the role of pioneers, spearheading agricultural development in remote uncultivated regions, sometimes on their own, and sometimes alongside other colonist farmers. This, incidentally, frequently put them in situations of territorial conflict with the indigenous peoples inhabiting those areas (e.g., Loewen, Citation2016, pp. 180–181).

This tendency to settle remote areas, we argue, is related in part to the particular set of constraints and preferences shared by Low German Mennonites, which makes them somewhat different from both peasants and capitalist farmers, the typical agents of frontier land-use change. Indeed, while some can undoubtedly be characterized as successful capitalist farmers (e.g., in older Mexican or Paraguayan colonies) or as peasant colonists (e.g., in the new Peruvian colonies), these labels fail to capture some important dynamics, especially in terms of how and where new colonies are created. First and perhaps most evident is the prevalence of religious principles not only in decisions to migrate but also in the choice of where to settle. This characteristic has interesting implications for how we understand frontier dynamics. Rent-based frameworks normally assume that land-use agents – large or small – seek to minimize distance to markets. But here is one class of agents that seeks out remoteness, or at least enough remoteness to keep outside influences at bay.

Along with this comes a high tolerance for sacrifice and hard work (or drudgery in Chayanovian terms (Van der Ploeg, Citation2013)), which are arguably elevated to a value in and of themselves (Loewen, Citation2008). These two characteristics taken together mean that Mennonites have had a propensity to create colonies in remote, hard-to-settle regions. In doing so, they change the conditions for other actors. Successful colonies provide proof to other farmers that agriculture is possible in remote regions, and they create roads and provide services where there were none (many colonies have good mechanics and some Mennonites advise outsiders on their farms). This makes the prospect of agriculture more attractive around them, and consequently, colonies seldom remain self-contained islands for very long.

In other ways, though, Mennonites appear more like a hybrid between peasant and capitalist farmers. A concern for social reproduction over capital accumulation, as well as small average farm sizes, situates them closer to peasant farmers (although capital accumulation and increasing land holdings have become more prevalent among older and more progressive colonies of Mexico and Paraguay). So does a focus on mixed farming systems managed at the family level. As organizations, however, Mennonite colonies operate much like transnational capitalist farms, negotiating access to large tracts of land, building their own roads, and transferring large amounts of capital as well as considerable know-how to their new locations. Additionally, Mennonites form a transnational network that differentiates them from most peasants in Latin America. This network can open up employment opportunities, e.g., for Mexican Mennonites traveling to Canada to work seasonally in Mennonite-owned farms and businesses (Gingrich & Preibisch, Citation2010). It also facilitates migrations and colony creation, by enhancing the awareness of conditions in potential destinations and offering support to candidate migrants. Mennonitische Post readers, for example, frequently comment on the creation of new colonies in other countries, offering opinions and advice, and newly established colonists send reports on harvests, weather, and other local conditions. Delegations sent to find new land in a country or region where colonies exist find help and advice in these colonies, similar to the network effects described in le Polain de Waroux (Citation2019) for large capitalist farms.

This particular blend of characteristics has arguably made Mennonite farmers into ‘perfect colonists’ in Latin America, a role that has unquestionably led them to become major agents of land-use change. Based on this observation, we propose seven lines of inquiry for future research. First, while it seems evident that Mennonite colonies have played an important role in the development of agricultural frontiers, questions remain about the nature and extent of that role. How exactly did Mennonite colonies in remote areas influence the subsequent development of these frontiers? Through what mechanisms might these colonies have incentivized the arrival of other actors at the frontier? Second, and relatedly, what has been the overall influence of these colonies on regional land-use change, agricultural production, and economic growth, but also on environmental sustainability? Third, what is the influence of their surroundings on Mennonite colonies? For example, do colonies absorb agricultural practices emanating from their neighbors? Fourth, while some colonies, like the ones in the Paraguayan Chaco, have become immensely successful, multiple others never grew much beyond their original size, and some were dissolved after just a few years. What explains the fact that some colonies have thrived over time while others stagnated or even collapsed? Fifth, how does the embeddedness of Mennonite colonists in a broader transnational network of colonies influence their land use – the search for land, the development of farming technology, investments in infrastructure? Sixth, Mennonites are a diverse group, particularly with respect to levels of religious conservatism. How do differences in beliefs shape land-use decisions, particularly with respect to the choice of locations for new colonies and of crops to cultivate? Do farmers in more progressive colonies align more with capitalist motives than those in conservative ones? Finally, the prominence of religious motives in land-use decisions puts some of the limitations of common frameworks used to understand frontier expansion into relief. What does the role of religion in Mennonites’ land-use decisions mean for how we understand frontier land-use change, particularly for the role of non-economic motives in this process? This is an ambitious agenda, but one we believe has the potential to yield important insights for the study of land-use change in Latin America and beyond.

Supporting_Information.docx

Download MS Word (13.4 MB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the people who made this article possible by sharing information, materials and insights, especially, but not exclusively: Kennert Giesbrecht from the Mennonitische Post, Ruben Giesbrecht (Mexico), Friedhelm Wiebe and the Neuland Cooperative (Paraguay), Willie Buhler and the Sommerfeld Cooperative (Paraguay), Peter T. Bergen from La Honda (Mexico), and Lucas Land from the Mennonite Central Committee in Bolivia. We would also like to thank Oliver Coomes, Daniel Müller, Tobias Kümmerle and Megan Toth, as well as three anonymous reviewers, for their helpful comments and suggestions. This research was supported by a grant from the McGill Sustainability Systems Initiative (MSSI).

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available for download under the following link: https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/I4FEQZ

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The complete data (vector files of the complete map, table and family tree of all colonies) is available under the following link: https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/I4FEQZ

References

- Barbier, E.B. (2012). Scarcity, frontiers and development. The Geographical Journal, 178(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2012.00462.x

- Bergen, P.T. (2017). Die 17 Kolonien in Campeche. Eine Reise durch die 17 Kolonien im Bundesstaat Campeche.

- Bowen, D.S. (2001). Die Auswanderung: Religion, culture, and migration among Old Colony Mennonites. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 45(4), 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2001.tb01496.x

- Browder, J.O., & Godfrey, B.J. (1997). Rainforest Cities, Urbanization, Development and Globalization of the Brazilian Amazon. Columbia University Press.

- Caldas, M., Walker, R., Arima, E., Perz, S., Aldrich, S., & Simmons, C. (2007). Theorizing land cover and land use change: The peasant economy of Amazonian deforestation. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 97(1), 86–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00525.x

- Cañás Bottos, L. (2008). Old Colony Mennonites in Argentina and Bolivia.Brill. http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/books/9789047430636

- Correia, J.E. (2019). Soy states: Resource politics, violent environments and soybean territorialization in Paraguay. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(2), 316–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1384726

- Dormady, J. (2014). Mennonite colonization in Mexico and the pendulum of modernization, 1920–2013. The Mennonite Quarterly Review, 88(2), 167–194.

- Eicher, J.P.R. (2019). Exiled Among Nations: German and Mennonite Mythologies in a Transnational Age (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108626392

- Foley, J. (2005). Global consequences of land use. Science, 309(5734), 570–574. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1111772

- Friesen, M.W. (2009). New Homeland in the Chaco Wilderness. Historical Committee of the Menno Colony.

- Friesen, U. (2007). Land– Oder Grundbesitz der Kolonie Menno. Die Mennonitische Post.

- Gibbs, H.K., Ruesch, A.S., Achard, F., Clayton, M.K., Holmgren, P., Ramankutty, N., & Foley, J.A. (2010). Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16732–16737. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0910275107

- Giesbrecht, K. (2018). Strangers and Pilgrims Volume II: How Mennonites are changing landscapes in Latin America. Die Mennonitische Post.

- Giesbrecht, K., & Klassen, W. (2015). Auf den Spuren der Mennoniten: 19.000 km durch Amerika. Die Mennonitische Post.

- Gingrich, L.G. (2014). Preserving Cultural Heritage in the Context of Migratory Livelihoods. International Migration, 52(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12066

- Gingrich, L.G., & Preibisch, K. (2010). Migration as Preservation and Loss: The Paradox of Transnational Living for Low German Mennonite Women. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(9), 1499–1518. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2010.494825

- Goossen, B.W. (2016). Religious Nationalism in an Age of Globalization: The Case of Paraguay’s “Mennonite State”. Almanack, 14(14), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-463320161405

- Graesser, J., Aide, T.M., Grau, H.R., & Ramankutty, N. (2015). Cropland/pastureland dynamics and the slowdown of deforestation in Latin America. Environmental Research Letters, 10(3), 034017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/3/034017

- Hecht, A. (1975). The Agricultural Economy of the Mennonite Settlers in Paraguay. Growth and Change, 6(4), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2257.1975.tb00808.x

- Hecht, S.B. (2005). Soybeans, Development and Conservation on the Amazon Frontier. Development and Change, 36(2), 375–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00415.x

- INEGI. (2017). Encuesta Nacional Agropecuaria 2017. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ena/2017/.

- Janzen, W. (2004). Welcoming the Returning “Kanadier” Mennonites from Mexico. Journal of Mennonite Studies, 22, 11–24. jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/download/995/994

- Karger, D.N., Conrad, O., Böhner, J., Kawohl, T., Kreft, H., Soria-Auza, R.W., Zimmermann, N.E., Linder, H.P., & Kessler, M. (2017). Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas. Scientific Data, 4(1), 170122. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.122

- Kleinpenning, J. (2009). The Mennonite Colonies in Paraguay. Origin and Development (Ibero-Bibliographien). Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut. http://www.iai.spk-berlin.de/publikationen/ibero-bibliographien.html

- Kopp, A. (2015). Las colonias menonitas en Bolivia. Fundación Tierra.

- La poderosa congregación que ha comprado 16.000 hectáreas en el Meta. (2018). El Tiempo. https://www.eltiempo.com/justicia/investigacion/colonia-menonita-compra-extensos-terrenos-en-meta-202530

- le Polain de Waroux, Y. (2019). Capital has no homeland: The formation of transnational producer cohorts in South America’s commodity frontiers. Geoforum, 105, 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.016

- le Polain de Waroux, Y., Baumann, M., Gasparri, N.I., Gavier-Pizarro, G., Godar, J., Kuemmerle, T., Müller, R., Vázquez, F., Volante, J.N., & Meyfroidt, P. (2018). Rents, actors, and the expansion of commodity frontiers in the Gran Chaco. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(1), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1360761

- Loewen, R. (2008). To the ends of the earth: An introduction to the conservative Low German Mennonites in the Americas. The Mennonite Quarterly Review, 82(3), 427–448.

- Loewen, R. (2016). Horse-and-buggy genius: Listening to Mennonites Contest the Modern World. University of Manitoba Press.

- Loewen, R., & Nobbs-Thiessen, B. (2018). The Steel Wheel: From Progress to Protest and Back Again in Canada, Mexico, and Bolivia. Agricultural History, 92(2), 172. https://doi.org/10.3098/ah.2018.092.2.172

- Loewen, R., & Nolt, S.M. (2012). Seeking Places of Peace. Good Books.

- Nobbs-Thiessen, B. (2020). Landscape of Migration. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Pacheco, P. (2005). Populist and capitalist frontiers in the Amazon: Diverging dynamics of agrarian and land-use change. Clark University.

- Pacheco, P. (2012). Actor and frontier types in the Brazilian Amazon: Assessing interactions and outcomes associated with frontier expansion. Geoforum, 43(4), 864–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.02.003

- Pauls, K. (2004). Northfield Settlement, Nova Scotia: A New Direction for Immigrants from Belize. Journal of Mennonite Studies, 22, 167–184. jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/download/1003/1002

- Penner, B. (2014). Von Mexico nach Paraguay: Mexikanische Mennoniten finden in Paraguay ein neues Zuhause. Liberty Libros.

- Plasil, T. (2017). Community and Schism among the Old Colony Mennonites of Belize: A Case Study. Journal of Mennonite Studies, 33, 251–273. http://jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/view/1607

- Roessingh, C. (2007). Mennonite communities in Belize. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 1(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2007.013722

- Roessingh, C., & Boersma, K. (2011). “We are growing Belize”: Modernisation and organisational change in the Mennonite settlement of Spanish Lookout, Belize. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 14(2), 171. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2011.042718

- Roessingh, C., & Bovenberg, D. (2018). The Hoover Mennonites in Belize: A History of Expansion in the Shadow of Separation. Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies, 6(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.18061/1811/86023

- Roessingh, C., & Plasil, T. (2009). Between Horse and Buggy and Four Wheel Drive: Change and Diversity among Mennonite Settlements in Belize, Central America. VU University Press.

- Sawatzky, H.L. (1971). They Sought a Country: Mennonite Colonization in Mexico. With an Appendix on Mennonite Colonization in British Honduras. University of California Press.

- Schartner, S., & Schartner, S. (2009). Bolivien: Zufluchtsort der konservativen Mennoniten. Editorial Litocolor S.A.

- Schroeder, W., & Huebert, H.T. (1996). Mennonite Historical Atlas (2d ed.). Springfield Publishers.

- Sierra Praeli, Y. (2020). Menonitas en Perú: Fiscalías de Loreto y Ucayali investigan deforestación de 2500 hectáreas en la Amazonía. Mongabay LatAm. https://es.mongabay.com/2020/10/menonitas-peru-investigacion-deforestacion-amazonia/

- van der Ploeg, J.D. (2013). Peasants and the art of farming: A Chayanovian manifesto. Fernwood Publishing.

- Vázquez, F. (2013). Geografía Humana del Chaco Paraguayo: Transformaciones territoriales y desarrollo humano. ADESPO.

- Warkentin, A. (1987). Strangers and Pilgrims: Hebrews 11:13. Die Mennonitische Post.

- Will, M.E. (1997). The Mennonite Colonization of Chihuahua: Reflections of Competing Visions. The Americas, 53(3), 353–378. https://doi.org/10.2307/1008029