ABSTRACT

The concept of marginal land in large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) has become important to understand land for LSLA deals. Based on remotely gathered geospatial data, the biophysical dimension of the concept dominates the characterization of land for LSLA deals. Little attention is paid to the socio-cultural dimension that represents years of dynamic community–environment interactions as lived experiences that are well structured in traditional knowledge. Informed by participatory appraisal methods in Nansanga farm block, an LSLA deal in Zambia, this study aimed at providing socio-cultural evidence that questions the concept constructed within science-development policy and political spaces. Overall, based on socio-cultural evidence, the findings suggest that Nansanga cannot be discounted as marginal land. In contribution to improving our understanding of human-environment interaction in land-use science, the paper argues for a mix of process-oriented and pattern-based approaches to gain better insights into land use change at spatial and temporal scales.

1. Introduction

The contemporary wave of large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) triggered by a convergence of global crises regarding finance, food, environment and energy (Borras & Franco, Citation2012) has highly been contested among stakeholders. The wave has involved the (re)valorization of land as new governance rules shift from territorial to flow-centred arrangements (Sikor et al., Citation2013). One of the reasons for the contestation regards ecosystem degradation (for adverse impacts of LSLAs, see Oberlack et al. (Citation2016)). In contrast, proponents of LSLA deals apply the concept of ‘marginal land’ (CML) to suggest that trade-offs between forest and commercial agriculture can be minimized through spatial management and the use of degraded land (Lambin & Meyfroidt, Citation2011). CML has therefore, increasingly become important in the LSLA debate though it does not have a precise meaning (Nalepa & Bauer, Citation2012). According to McCarthy et al. (Citation2012), land is marginal if a cost-benefit analysis yields a negative result, or if the land is deemed to be of poor quality, is remote, is arid, is infertile or lacks infrastructure. Dauber et al. (Citation2012, p. 10) on the other hand, define marginal land as ‘idle, underutilized, barren, inaccessible, degraded or abandoned lands, lands occupied by politically and economically marginalized populations, or land with characteristics that make a particular use unsustainable or inappropriate.’ Gironde et al. (Citation2014) indicate that land is marginal if it is unused yet suitable for agriculture. Particularly related to the production of biofuels, marginal lands refer to degraded lands that are not suitable for other food crops (McCarthy et al., Citation2012). Deininger et al. (Citation2011) refer to marginal lands as lands that are uncultivated, non-forested that would be ecologically suitable for rain-fed cultivation in areas with less than 25 persons km−2. Nalepa and Bauer (Citation2012) indicate that in the context of LSLAs, marginal lands generally refer to lands that are arable, yet degraded or difficult to farm, based on biophysical characteristics such as soil profile, temperature, rainfall and topography (slope). These different interpretations highlight the socio-cultural, economic and biophysical dimensions of CML that are employed to revalorize land as a factor of production that leads to its (re)definition and (re)assembling. Sikor et al. (Citation2013, p. 522) define (re)valorization as ‘the process whereby qualitatively or quantitatively distinct values, which differ from those previously extant or recognized, are given to specific lands.’ The process of (re)valorization therefore, is an assemblage of materialities, relations, technologies and discourses to turn land to productive use (Li, Citation2014). Also, the interpretations bring to the fore three aspects that shape patterns of land use: actors; driving forces; and land change (Hersperger et al., Citation2010). As a defining factor, CML becomes useful at conceptual and theoretical levels in understanding the human-environment interaction and the environmental changes that ensue from the interaction.

CML based on biophysical features is more predominant in characterising land targeted for LSLA deals as ‘non-competitive’ (Nalepa & Bauer, Citation2012). Borras et al. (Citation2013) note that stakeholders make arguments based on biophysical and economic features in their support for LSLA deals. In contribution to land-use science within the contemporary wave of LSLAs, CML sheds light on the interaction among actors and driving forces, and how that interaction leads to land use change. summarizes the three dimensions of CML relevant to understanding the biophysical and human causes of land use change in the context of LSLA.

Table 1. Main dimensions of the concept of ‘marginal land’

From , the environmental and economic dimensions in shaping land use are dominated by interactions between policy makers and investors within the development policy space. In this space, policy makers seek to commercialise land to achieve rural development while investors (national and foreign) seek land for capital accumulation. The interplay between them informs land use decisions and shapes land use change. The socio-cultural dimension is related to immediate land users and is spatially context-specific. The biophysical and economic dimensions therefore, tend to be more important for the interests of policy makers and investors, while the socio-cultural dimension tends to be more important for local communities. Land marginality based on biophysical features and economic opportunities happens within a science-policy and political space. Contrarily, the socio-cultural dimension is a community lived experience of human-environment interaction – highlighting power play in CML between the science-policy and political space and rural communities whose land is involved in LSLA deals. The three dimensions of CML have parallels with actors, driving forces, and land use change as building blocks of land-use science (Hersperger et al., Citation2010). Driving forces refer to policies that interact with or are acted upon by actors (who might be land users, policy makers or investors) to produce non-linear land use changes.

According to Hersperger et al. (Citation2010), characterizing land use change is based on two approaches: a process-oriented approach based on household surveys (anthropologic); and a land evaluation, pattern-based approach based on remote sensing and census data. The second approach is consistent with identifying marginal lands based on biophysical features (Nalepa & Bauer, Citation2012). Thus, there is overreliance on biophysical features to understand land change even if biophysical variables have received less attention as causal factors (Turner et al., Citation2007). However, German et al. (Citation2013) caution that the identification of marginal land is based on assumptions and perceptions rather than evidence. Little attention is paid to context-specific socio-cultural and economic processes as actors and driving forces interact to: i) (re)valorize, (re)assemble and redefine land (Li, Citation2014) as ‘marginal;’ and ii) produce land use change (+ or -ve).

Contributing to addressing environmental and societal problems, theories, concepts and models around land use change (Turner et al., Citation2007), land-use science continues its quest to better understand land use at different spatial and temporal scales (Müller & Munroe, Citation2014). In this quest, CML deserves critical attention within LSLA scholarly discourse. The attention is relevant at three levels: i) CML is an outcome of the ‘human-land nexus’ that is mediated by driving forces; ii) the identification of ‘marginal land’ has methodological concerns related to anthropologic and pattern-based approaches for characterizing land use change; and iii) LSLA deals in which CML is applied are a land-use science issue involving actors, driving forces and land interacting in dynamic and hard to predict socioeconomic, policy and political processes. Additionally, due to time and financial constraints, combining process-oriented and pattern-based approaches to better understand land use change is not a very common practice. This paper makes a case that CML that is used to justify LSLA deals constitutes (often downplayed) complex interactions that include: territoriality (spatial dimension); biophysical conditions (environmental affordances); and social relations (constructed by more influential stakeholders, reflecting power play) as actors with different motivations interact (in time, reflecting the temporal dimension) with land to produce land use change.

Using a process-oriented approach, this paper has one aim: to provide the socio-cultural evidence of previously held customary land that has been leased as an LSLA deal to promote commercial agriculture under the 2002 government of Zambia-spearheaded farm block program in the Nansanga miombo woodland. The paper then uses the evidence to make an informed commentary on the marginality of the leased land. In this paper, I use the term ‘socio-cultural’ loosely to refer to aspects of the Nansanga miombo woodland that communities depend on for their intangible social and cultural values as well as tangible livelihood benefits. Operationally, this means that the leased land is marginal if there is no socio-cultural evidence of community use of the land. Therefore, I define land to be marginal if it is unused by communities for their intangible values and livelihoods. With reference to Scoones (Citation1998, p. 5), livelihoods refer to the ‘capabilities, assets (including both material and social resources) and activities required for a means of living.’ In this regard, Nansanga area is marginal if community members do not apply their capabilities and assets to the area to extract both material and social resources for their living because the resources are non-existent and/or scarce.

At local level, the cultural value of land is an ‘all-life’ lived experience of different community land uses. The cultural value of land in CML is ascriptive due to power imbalances during stakeholder interactions. Similarly, while acknowledging that land provides many ecosystem services and provides cultural and spiritual services (Verburg et al., Citation2013), land-use scientists see the cultural value of land as a product of land (re)valorization for economic or political reasons (see Sikor et al., Citation2013) (see discussion section).

The paper contributes to land-use science in four main ways: First, within the human-environment nexus, the paper theorizes that CML is produced during the ‘actor-driving forces’ interaction to produce land use change. Second, the few attempts to understand land targeted for LSLAs deals have used the pattern-based approaches, e.g. geospatial technologies (see Messerli et al., Citation2014; Nalepa & Bauer, Citation2012). This paper makes a methodological contribution by using a process-oriented, community-centred approach informed by participatory rural appraisal methods to provide socio-cultural evidence that informs the qualification of land targeted for LSLA deals as marginal or not marginal. Third, the paper makes a contribution to a research call by Messerli et al. (Citation2014) who have argued for a development of new approaches and methods to empirically link socio-ecological patterns in LSLA target contexts to key determinants of land investment processes. Fourth, as a research-based assessment of CML that focuses on socio-cultural aspects, the paper brings into perspective a local people-centred process-oriented approach to understand the centrality of land to local livelihoods, while theoretically advancing the understanding of livelihoods in the human-environment nexus in LSLA deals – an approach often disregarded for non-local economic interests. Finally, as a case study in Zambia, the paper contributes a spatial dimension to LSLA research with particular resonances with other studies, for example, in Asia (e.g. Neef & Singer, Citation2015), Latin America and the Caribbean (e.g. Borras et al., Citation2012) and continental and Southern Africa (e.g. Hall, Citation2011; Schoneveld, Citation2017).

The paper is structured as follows: I draw on ecological equilibrium to theorize CML in LSLA deals in section 1.1. In section 2, I present the research design and methods, including a brief history of the development of Nansanga farm block. Presentation of results is in section 3. Discussion of results and the conclusion are in sections 4 and 5, respectively.

1.1 Theorizing the concept of marginal land in LSLA deals: ecological equilibrium

In this section, I briefly attempt to theorize CML more in terms of explaining the ‘actor-driving force’ interaction, and how that interaction leads to land use change within the context of LSLAs. I don’t attempt to validate CML but highlight its coherence in explaining (Briassoulis, Citation2019) how actors and drivers of LSLA deals interact to (re)valorize land as marginal. I refer to the farm block program in Zambia.

The 2007/2008 food price spike that raised food security concerns, financial investments following the global financial crisis, and biofuel production have been cited as the three main global drivers of the new wave of LSLAs (see Taylor & Bending, Citation2009; Woodhouse, Citation2012). While LSLAs have been contested citing socio-economic and environmental concerns in host countries (Borras & Franco, Citation2011), the global drivers have drawn new attention to land, its uses and value (Li, Citation2014). The new attention has put LSLAs on global policy agenda, e.g. the World Bank holds an annual conference on land and poverty that brings together different stakeholders.

LSLAs have spatial and jurisdictional scales. Chilombo et al. (Citation2019) propose a conceptual framework to improve the understanding of LSLA deals, arguing for a mix of methodological approaches that simultaneously consider context-specific micro-level processes and how they are linked to broader, higher policy and geographic level spaces and contexts. To theorize CML in contribution to land-use science, LSLAs are understood as a form of land use change within a coupled human-environment system interaction. While the interaction is biophysical-dependent and territorially conditioned, the modes and patterns of land use are also influenced by socio-cultural and economic dimensions, as these are characterised in . It is noted that elements of these dimensions can be either endogenous (originating within the territory where LSLA deals unfold and CML is applied) or exogenous (originating from outside the territory – such as foreign investors and global drivers). Thus, the implementation of an LSLA deal at local level is a cumulative process (therefore, temporally relevant) that brings together different actors and policy, economic and institutional drivers (therefore, spatially relevant). Scale is therefore, relevant to theorizing CML within the farm block program in Zambia that has led to the conversion of customary land to leasehold for national (and beyond) level interests, and economic interests of non-local investors.

Zambia’s land tenure system that was inherited from colonial land administration is bifurcated into customary and statutory land; the former being under traditional leadership, and the latter under state institutions (Smith, Citation2004). In 2002, the Zambian government (henceforth State) decreed an agricultural program to establish nine farm blocks across the country for food security, reducing rural-urban migration and general rural development (GRZ, Citation2005). This was to be achieved by converting customary land to leasehold. This program led to the establishment of Nansanga farm block on 155 000 ha of previously held customary land that belonged to the chiefdom Muchinda, central Zambia.

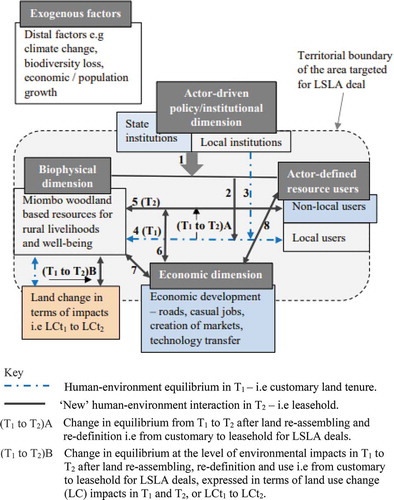

I delineate land use during customary land tenure in period 1 as T1, while land use during leasehold in period 2 as T2. To substantiate T1 and T2, I draw on ecological equilibrium, a theoretical postulate that espouses that a territory consists of a population, resources, technology and institutions that are constantly in a state of dynamic yet stable equilibrium (Coccossis et al., Citation1991). The territorial equilibrium is disrupted when one of the four factors changes. Thus, in the case of Nansanga, the transition from T1 to T2 was triggered by the change in one or more of socio-ecological defining factors of customary land as a territory. Originating in the writings of Paul Ehrlich (1968), Briassoulis (Citation2019) reminds of the operational relationship that links environmental impacts (I) to the change in population (P), affluence (A), and technology (T) at the global scale. This is presented in the expression I = PAT. To consolidate this operational relationship expressed in I = PAT, Ehrlich and Ehrlich (Citation2009) note that as human population grows, consumption patterns change and technological skills improve, the Earth is pushed over its limits to produce and support people. Drawing on this theoretical postulation, illustrates my attempt to theorize CML in LSLA deals.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework for theorizing CML within LSLAs

presents a territory, e.g. Nansanga that is targeted for an LSLA deal with four dimensions which encapsulate determinants of human-environment interactions at local level. Besides the biophysical dimension, local resource users (under actor-defined resource users) and local institutions (under actor-driven policy and institutional dimension), the other dimensions are present within and outside the territory that is targeted for an LSLA deal. T1 is characterised by local people’s interaction with land for their livelihood and wellbeing, regulated by T1 institutions. T2 is characterised by a new policy and institutional regime. The transition from T1 to T2 is an iterative but also cumulative process (step 1) that combines all the territorial dimensions and exogenous factors. Exogenous factors are distal in relation to the LSLA deal territory; however, they have an important role and influential when an LSLA deal is driven by factors such as biofuels to reduce carbon emissions, food security in response to the spike in food prices and land-based investments in response to global financial crisis.

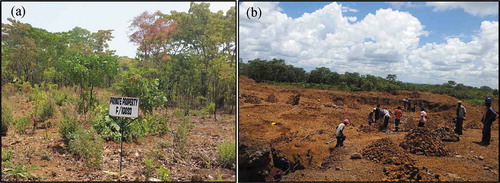

The framework assumes that an LSLA deal is an external disruption that introduces changes to the socio-ecological environment of rural communities. These changes include a new land governance regime from customary tenure (traditional authority without taxes) to leasehold (state administration with taxes) that changes access rights (e.g. private property rights) and modes of resource appropriation at both spatial (territory) and temporal scales, including land use change impacts (from T1 to T2) (e.g. see )).

Figure 2. Introduction of property regimes (farm #10,993) (a) and land use and land cover change (b) in leasehold (T2)

The steps 1 to 7 are not necessarily sequential because the changes within land systems are not linear processes (Long, Citation2020). Step 2 signifies the influences of T2 on T1. Step 3 represents how local institutions shape step 4 (T1) which represents the stable yet dynamic equilibrium in the community–environment interaction. It is important to note this stable, yet dynamic equilibrium reflects the socio-ecological system, that is, an interdependence between the local resource users and miombo woodland resources. As a stable, yet dynamic equilibrium, the interaction is a ‘safe operating space’ that is mediated by the asset portfolio of local resource users: natural capital, physical capital, financial capital, social/cultural capital, human capital and traditional knowledge. The interaction is also mediated by the local institutional infrastructure that governs customary land.

The economic dimension represents benefits for which LSLA deals are touted such as job creation, knowledge transfer (see Deininger, Citation2011). Steps 6 and 7 represent the interactions between the economic dimension and T2, and the biophysical dimension, respectively. Step 8 signifies the T2 interactions that resource users have with economic opportunities. Non-local resource users include direct resource beneficiaries such as investors and indirect ones such as policy makers. The change in (T1 to T2)A or a change from step 4 (T1) to step 5 (T2) leads to (T1 to T2)B, that is, land change in terms of impacts expressed as LCt1 to LCt2 (land change in T1 (customary tenure) to land change in T2 (leasehold)). In T2, depending on land use intensity, the impacts are likely to go beyond the territory.

Land marginality resonates with land (re)valorization in land-use science. In the contemporary wave of LSLAs, land use scientists’ research agenda is on strengthening transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary research that co-produces knowledge with stakeholders, and engage stakeholders to produce sustainable solutions (see Verburg et al. (Citation2015)). In the land system research agenda, land marginality is nested in how land-use scientists conceptualize land systems as dynamic interactions within the socio-ecological system that operate across spatial and temporal scales (Verburg et al., Citation2015). In this conceptualization, CML resonates with the process of land (re)valorization for economic, political or cultural reasons (Sikor et al., Citation2013). highlights that CML and the transition from T1 to T2 results are mediated by stakeholder (with different interests in land at different geographic levels and differentiated access to power) interactions. Thus, CML resonates with land system changes that directly result from ‘human decision making at multiple scales ranging from local land owners decisions to national scale land use planning and global trade agreements (Verburg et al., Citation2015, p. 30).’

In section 1.1 I have attempted to theorize CML to highlight the coherence of the concept in explaining ‘actor-driving forces’ interaction to yield land use change. In the next section, I present the research design and methods. I first present the study area in section 2.1, and then give a brief history of the establishment of the Nansanga farm block in section 2.2, and finally methods in section 2.3.

2. Research design and methods

2.1 Study area

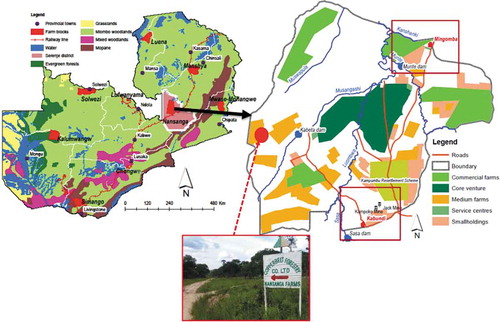

This study was carried out in Mingomba (~650 registered households) and Kabundi (~465 registered households) communities of Nansanga farm block (Nansanga henceforth) that sits on ~155,000 ha of previously held customary land (12° 47’S to 13° 0’S and 30° 5’E to 30° 4’E, elevation between 1,210.4 m and 1,347.4 m above sea level, and annual rainfall of 1 000–1 200 mm). Nansanga is in a structurally and floristically complex ecosystem, with soil fertility status that is characteristic of wet miombo woodlands crops (Chilombo, Citation2019). Mingomba and Kabundi community areas () were selected based on the level of developed infrastructure during Nansanga development, population concentration and accessibility. The pieces of infrastructure in both Mingomba (trunk road, Munte bridge, 6 000 000 m3 capacity Munte dam) and Kabundi (trunk road, 5 km irrigation canal, 10 000 000 m3 capacity Sasa dam) were finished in 2009–2010. Until the 1990s, the Lala people in the chiefdom practiced shifting cultivation on customary land. Traditionally, the Lalas are an uxorilocal society, and do not have typical clustered villages that are typical in most other rural parts of Zambia. Nansanga is a largely cashless rural economy, and communities cultivate maize, cassava, sorghum, groundnuts, and beans on 0.1–2 ha of land. They also rear village chickens, ducks, goats and pigs. This socio-economic context is detailed in the next section.

Figure 3. Study site – Mingomba and Kabundi areas

2.2 The establishment of the Nansanga farm block in the chiefdom Muchinda

In this section, I briefly describe the establishment of the farm block, reflecting the dimensions of CML as theorized in section 1.1. Also, I develop an understanding of the Lala’s interaction with land, and the socio-cultural context and experience that they have built over years of living in Nansanga. The discussion of CML in this paper is therefore, embedded in a concrete case with its own socio-cultural idiosyncrasies.

Given the size of customary land vs. state land in Zambia, LSLA deals happen on customary land, estimated at 51–54% of total land (Jayne et al., Citation2014). Thus, Nansanga was established in the wet miombo woodland of the chiefdom Muchinda of the Lala people. According to the State, the chiefdom was suitable for a farm block given its abundant annual rainfall (1,000–1,200 mm), good soil fertility status, sparse population and developed river system to support irrigation. The State invested financial resources to construct roads, bridges, boreholes, schools, health facilities, dams as well as pulling electricity into Nansanga (GRZ, Citation2005). By 2012 Nansanga had been parcelled into a core venture, commercial farms, medium size farms, smallholder farms and service centres () to operate as an out-grower scheme (GRZ, Citation2005). Investors who had bought farmland in the farm block were issued with title deeds by the State. These investors were mainly individual urbanites or companies such as the Copperbelt Forestry Company Limited that has a project to plant exotic tree species (see ). During the development process, community members were informed more than consulted about Nansanga (Chilombo, Citation2019).

The fieldwork for this study (2016–2019) showed that Nansanga is an LSLA deal in limbo of development: state-funded infrastructure has crumbled; there is no policy clarity on

the future development of the farm block given that the government does not have financial resources to complete the development of infrastructure; and many private investors have not developed the land they bought. Instead, tobacco contract farming by a private company, Tombwe Processing Limited, and two manganese open pit mines (Kampoko and Jack) have emerged as important economic activities in the farm block. Additionally, at the time of the fieldwork, there were 30 households with threats of displacement between Bwande and Munte rivers following a 2,202 ha land deal between Jeremy Baddock (businessman) and government officials.

Section 2.2 has briefly given an account of the establishment of Nansanga, highlighting the land tenure and cultural context of chiefdom Muchinda in which Nansanga farm block has been established. In the next section, I delve into the methodological approach.

2.3 Methods

The study used a process-based anthropologic approach informed by participatory rural appraisal methods to understand the process of farm block establishment, actor interests and power dynamics, and actor–environment interactions. In the next subsection, I detail the approach.

2.3.1 Understanding the socio-culturality of Nansanga farmland

Understanding the socio-culturality of Nansanga farmland relied on the experiences of local communities in the area. Therefore, evidence and knowledge of Nansanga farmland was co-produced with local communities as experts of the socio-cultural aspects of the area. This approach is embedded in socio-political constructivism that acknowledges that knowledge is not produced independently of values, assumptions and framings that are shaped by social interactions within, and experiences of the real world. Also, the theory acknowledges that scientific enquiry has limitations within a real world that is highly complex, and therefore uncertain and indeterminate (see Whitfield, Citation2016). This approach ensured that the understanding of the socio-culturality of Nansanga reflects local people’s values (and what matters the most in their relationship with land and associated resources), intentions and interests of land use that would otherwise not be possible with the use of remote spatial data techniques.

A total of 26 focus group discussions, and 41 key informant interviews were conducted. 14 of the informant interviews were done with government agencies, civil society organisations and developments outside Nansanga, and four with employees from the tobacco and mining companies. Focus group discussions each comprised eight – nine people, mixed with both men and women. The group discussions and informant interviews were complimented by walking interviews with traditional botanists, participatory resource mapping and transect walks, and family ‘evening fire’ meetings where more detailed data about the socio-cultural uses of Nansanga miombo woodland were collected. The traditional botanists identified the names of trees in the local language, Ichilala. I later translated the names based on a book of common trees in Zambia (see Storrs, Citation1995).

Understanding the socio-culturality of Nansanga was based on the socio-cultural values of important tree species, the Lala seasonal calendar, and the collection of mushrooms and caterpillars embedded in traditional knowledge. These were all informed by perspectives and years of experience of local communities.

3. Presentation of results

3.1 The socio-cultural values of important tree species and traditional knowledge

Section 3.1 presents results that reveal the level of community reliance and use of land and associated resources, underpinned by traditional knowledge. Traditional management of the miombo woodland in Nansanga is regimented. Burning takes place in August and September for land preparation, to allow shoots to sprout for domesticated ruminants, and to time the life cycle of caterpillars (focus group discussions in Mingomba and Kabundi, Nansanga, 2018).

The socio-cultural value of Nansanga is linked to the floristic composition. shows the 16 most important species with direct and indirect socio-cultural uses. Direct uses include medicinal, construction, food and aesthetics/art. Indirect uses include the making of handles of axes and hoes, and building canoes for other livelihood activities (agriculture and fishing).

Table 2. Most commonly used socio-cultural tree species in Nansanga

highlights community intimate interaction with land resources but also traditional ecological knowledge accumulated over years of socio-cultural practices and observations (Berkes et al., Citation2000). Lalas’ knowledge of tree species reveals the understanding of floral species biodiversity that ensures an ecological balance for the life cycle and survival of caterpillars, a rich yet cheap source of proteins. Caterpillars are tree species-specific, and therefore, the loss of trees on which eggs are laid will lead to the extinction of caterpillars in Nansanga (Key informant interview, Nansanga 2017).

The Lalas understand the ecology, including distinguishing the poisonous from the non-poisonous edible mushroom species. For example, they know that Bwitondwe (Cantharellus afrocibarius), Ubukungwa (Termitomyces titanicus), Tente (Amanita zambiana), Kabansa (Lactarius kabansus) and Chiteleshi (Russula ciliate) are associated with Brachystegia, Julbernardia, Isoberlinia, Marquesia, Monotes and Uapaca species, miombo ectomycorrhizal species (Frost, Citation1996). The Lalas have specific ways of pollarding trees, and understand tree regeneration patterns that they combine with rotation cycles to practice traditional chitemene system for crop production. shows years of land use through chitemene system – trees developing bulges on areas where they were cut and where they are coppicing.

Photo by author (Nansanga, November 2018).

Building on section 3.1 that has revealed community use of tree species underpinned by traditional knowledge, section 3.2 presents the seasonal calendar of the Lala people in Nansanga – further highlighting community–land interaction.

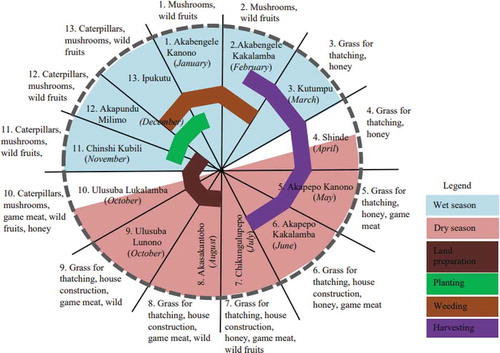

3.2 The Lala people seasonal calendar

To provide the socio-cultural evidence of the previously held customary land, the seasonal calendar was important to understand community livelihood activities. Overall, the seasonal calendar revealed patterns of collection of forest and non-forest products that constitute the means of community livelihoods, as well as the evolution of socio-cultural and economic activities after Nansanga. shows a 13-month traditional seasonal calendar, highlighting community–land interaction throughout the year. Being a cashless rural economy, the exploitation of land and forest resources constitutes the principal means to make a living. Barter system is still a common practice in the area, based on products from land and forest resources. For example, caterpillars and bushmeat are exchanged for maize flour or labour on family farms (focus group discussion # 3, Nansanga 2018).

Community members indicated that Nansanga introduced new regimes of resource access, control and use and non-Lala actors ()). Community members indicated that while they used land to cultivate crops and harvesting caterpillars, non-Lalas are using land differently. For example, they are burning the bush at any time of the year that suits them, while others are doing open-pit manganese mining (focus group discussion # 4, Nansanga 2018) ()).

Summarising the socio-cultural perception of land, one informant said:

Our life has been about land. We have been practising shift cultivation (chitemene system) time immemorial, as Lala people here. We use this land, and the morphology of trees is the proof we can show to anyone refuting our use of land. You also need to understand that even the Chibwela Mushi ceremony is about our cultivation of land and then our return to our villages in joy and celebration (Key informant interview, Nansanga 2018).

Section 3.2 has presented the seasonal calendar showing life in Nansanga revolves around the use of land and associated resources throughout the year. In section 4, I discuss these results in light of substantiating the socio-cultural evidence to determine the marginality of land in Nansanga.

4. Discussion

In discussing the results, I first relate the findings to CML before discussing the socio-cultural and seasonal calendar findings in sections 4.1 and 4.2, respectively.

CML has socio-economic but also biophysical dimensions on which different actors draw to engage in political processes to support or oppose LSLA deals. In this paper, I have chosen to use the term socio-cultural to reflect that the non-biophysical dimension of CML includes tangible and intangible benefits that communities get from the use of land. The biophysical dimension is informed by remote use of geospatial data. Other approaches such as forest surveys can also inform the biophysical dimension of marginal land – however, none of these approaches reflects the socio-cultural and policy processes that underpin changes in land use and land cover changes. Thus, community-level voices are hardly part of the processes of land (re)valorization. The socio-cultural dimension requires participatory approaches that engage affected communities in their environment to empirically link socio-ecological patterns in target contexts of land investment processes – important considerations of the Global Land Project (see Verburg et al. (Citation2013)).

Two questions are relevant: can the same land be biophysically marginal but socio-culturally not? What is more important between biophysical and socio-cultural dimensions in land marginalization? The answer partly lies in who sets the agenda and the role of the state in LSLA deals. Through a political process, the State in Zambia recognises land under traditional authority as customary land. The legal recognition makes it possible for the Lala people to define the value (non-monetary) of land – what they can use it for, when, how, and set boundaries that mark exclusion of access and use (through chiefdoms). This particular recognition does not make it resourceful because customary land does not have a market value and cannot be collateralised. Therefore, the way that the state has made customary land as an environmental resource (Parenti, Citation2015) excludes it from the capital accumulation equation to directly benefit local communities. Land tenure conversion from customary and inefficient producers (see Deininger & Byerlee, Citation2012) is a ‘de-marginalization’ process – or land (re)valorization in land-use science, to ‘render it exploitable’ in capital accumulation as it gets a new meaning (Li, Citation2014). Also, land (re)valorization sets new political and social processes and boundaries regarding how old (local community members) and new users (investors) will interact with land. This is regimented through markers of ownership such as title deeds or beacons (see ) showing farm #10993).

There are competing visions and contestations around land that is perceived as a factor of production, a resource for capital accumulation, but also as a territory for assertion of power (Parenti, Citation2015) – shaping the sense of ownership and social belonging. Land means different things to different people, and so its uses and meanings change and can be disputed. Land has presence and location and has diverse array of affordances; and land has devices of inscriptions such as title deeds, trees, ancestral graves, maps that are used to assemble it for different actors (Li, Citation2014). These aspects are reflected in the conceptual framework for theorizing CML (). In this regard, CML highlights that lands targeted for LSLA deals are ‘territories of contestations,’ and the ‘actor-driving forces’ interaction to yield land use changes (-ve/+ve) is a process shaped by competing interests.

The ‘de-marginalization’ of customary land by the State was based on biophysical features of land in chiefdom Muchinda. To potential investors, Nansanga area was advertised as sparsely populated (therefore, spatially available) with idle though suitable soils for crop production. The area has enough rainfall with a river system to support irrigation. Thus, the ‘de-marginalization’ of customary land in Nansanga was influenced by the ‘environmental resourceness’ or the ‘biophysical affordances’ of land, including the physical size of the area.

However, land (re)valorization based on ‘biophysical affordances’ is dynamic in response to economic interests. Thus, using its political legitimacy, the State further (re)valorized leased Nansanga land and issued manganese mining licences on the land initially planned for commercial agriculture ()). This demonstrates that land does not have an intrinsic quality; however, its ‘resourceness’ is assembled and made up; it waxes and wanes, or morphs through state mediation (Li, Citation2014).

Land marginalization based on biophysical features is thus, a policy process and a top-down approach that is accomplished within the science-policy and political space. By contrast, land marginalization based on socio-cultural features is a local-context centred and bottom-up approach that draws on lived experiences of local community–environment interaction. Given the policy process and political legitimacy that accompany land marginalization, it is possible that the same land be biophysically marginal but socio-culturally not. By the same policy process, biophysical features seem more relevant to policy-makers and investors, while socio-cultural features are more relevant to direct land-users.

From the findings, the cultural value of land for local communities is largely non-monetary. For land-system scientists, the cultural value of land seems to be a result of the land (re)valorization process (e.g. for it to gain a productive, economic function as in agricultural use) (Sikor et al., Citation2013) – a process more likely to be informed by biophysical features. Land is a capital asset that belongs to its users. For local communities such as the Lalas, the cultural value of land is an ‘all-life’ system where land belongs to people, and people belong to land. I discuss this further in the next section.

4.1 Socio-cultural community uses of Nansanga miombo woodland and traditional knowledge

LSLAs are supported for their potential to contribute to infrastructure development, job creation and knowledge transfer (see Deininger, Citation2011). Predominantly, development is viewed as a quantitative and material process (Abbink, Citation2011) that is top down, with insufficient regard for local socio-cultural realities. Based on local interviews, the miombo woodland of Nansanga is, in the words of Dewees et al. (Citation2010, p. 61) ‘a pharmacy, a supermarket, a building supply store, and a grazing resource, providing consumption goods not otherwise easily available.’ It is in this ‘all-life’ context of Nansanga that the State socio-culturally ‘marginalized’ customary land ownership.

Neglecting community-level socio-cultural aspects has also been echoed in LSLA deals in Ethiopia. Abbink (Citation2011, p. 524) notes that the state authorities in Ethiopia dispose of land ‘without ascertaining its comprehensive value and socio-cultural role for existing communities and without consulting the “stakeholders” or a negotiated compensation.’ The striking difference between the Zambian and Ethiopian cases is that there are two land tenure systems (state and customary land) in Zambia, and only state land in Ethiopia. However, for the state in both countries, community land use marginalizes land; investor land use for capital accumulation ‘de-marginalizes’ it.

Among Lalas, customary land ‘ownership’ is through inheritance from parents or family members, or allocation by the senior chief. The Lalas therefore, feel that land is a heritage, more than a (re)valorized asset in purely economic sense. The socio-cultural fabric of the people is woven in land. Community members have deep pharmaceutical, artistic, architectural, domestic, ecological, and nutritional knowledge of tree species in Nansanga (see ). They also have biodiversity conservation knowledge – they understand that the loss of tree species associated with caterpillars and mushroom will lead to loss of these resources. This knowledge has been accumulated over many years of interaction with land in Nansanga. They have tested the knowledge and have proved that the trees work to meet their needs. The knowledge is part of community heritage. This evidence is instructive and suggests the intimate community–land interaction that discounts Nansanga as marginal.

It is noted that resource management based on socio-cultural practices and beliefs embedded in traditional knowledge is not unique to Nansanga. Dell’Angelo et al. (Citation2017) note that traditional communities use their ethical beliefs based on traditional knowledge to manage land and forest resources they directly depend on, making them resilient to social and environmental disturbances. For example, the Lugba people in Uganda are reported to use norms and local regulation to guide their resource use and management (Agatha, Citation2016).

4.2 The Lala people seasonal calendar

The seasonal calendar of the Lala people powerfully reveals that land is at the centre of the life in Nansanga throughout the year. Also, the calendar gives insight into the potential socio-cultural implication for community members when the State redefines land from customary to leasehold for capital accumulation by non-Lalas.

Management of land, including access to resources are all regimented based on traditional knowledge of the seasonal calendar. In this regard, the seasonal calendar is a marker of the traditional knowledge of the Nansanga socio-ecological system. If people did not use the land, they would not have developed such a structured seasonal calendar where all socio-cultural activities are linked to the use of land. The seasonal calendar therefore, provides socio-cultural evidence that suggests that land in Nansanga is not marginal.

5. Conclusion

The process of identifying land for LSLAs is predominantly based on biophysical affordances of land in the process of material accumulation, with little regard for socio-cultural affordances of the same land to rural populations. Using participatory rural approaches, this paper aimed at providing evidence of the socio-cultural affordances and use of the miombo woodland where Nansanga has been established to comment on the area’s marginality. The operational definition of CML in this paper has been that land in Nansanga area is marginal if there is no socio-cultural evidence of community use. With its different meanings, CML is important to understand human-environment interactions based on either biophysical features (top down) or socio-cultural features (bottom up). Overall, the findings suggest that Nansanga cannot be discounted as marginal land based on the socio-cultural uses of the land by community members.

As LSLA deals continue in the global south, this paper demonstrates the important role of process-based approaches (bottom up) in land-use science to understand human-environment interaction at micro-level where community members are co-producers of knowledge regarding land use change – relevant to the Global Land Project agenda. Based on the findings, it can safely be contended that if the concept and definition of land as marginal sufficiently reflected socio-cultural uses of land, LSLA deals would be designed differently to ensure investments led to ‘win-win-win’ situations for all stakeholders concerned. In this regard, land-system scientists have an important role in shaping the design and outcomes of LSLA deals – by advancing innovative methodological approaches that combine ‘top down and bottom up’ perspectives, and socio-cultural and biophysical dimensions of land to improve our understanding of the coupled human-environment interaction at different spatial and temporal scales.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their very useful comments. I thank Mr. Moses Chiposa, Mr. Edwin Shiaka and Mr. Mweemba Sunya from the School of Natural Resources, the Copperbelt University for their support in the collection of data during the forest surveys. The efforts of Mr. Herald Mwape, the senior chief advisor in Mingomba, and the village headman in Kabundi in identifying local botanists and key informants in Nansanga are acknowledged. Acknowledgements are also extended to Mr. Simon Mulenga and Mr. Rodrick Mwape for providing accommodation during the field visits within Nansanga, and spearheading family ‘evening fire’ meetings. Finally, I acknowledge the support of Ms Lombe Tembo in transcribing the focus group discussions and key informant interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbink, J. (2011). ‘Land to the foreigners’: Economic, legal, and socio-cultural aspects of new land acquisition schemes in Ethiopia. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 29(4), 513–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2011.603213

- Agatha, A. (2016). Traditional wisdom in land use and resource management among the Lugbara of Uganda: A historical perspective. SAGE Open, 6(3), 215824401666456. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016664562

- Ashukem, J.C.N. (2016). Included or excluded: An analysis of the application of the free, prior and informed consent principle in land grabbing cases in Cameroon. Per/pelj 19(19). https://doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2016/v19n0a1222

- Berkes, F., Colding, J., & Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery of traditional ecological management as adaptive management. Ecological Applications, 10(5), 1251–1262. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2

- Borras, S.B., Hall, R., & Scoones, I. (2011). Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: An editorial introduction. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.559005

- Borras, S.M., & Franco, J.C. (2012). Global land grabbing and trajectories of Agrarian change: A preliminary analysis. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(1), 34–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2011.00339.x

- Borras, S.M., Franco, J.C., Gómez, S., Kay, C., & Spoor, M. (2012). Land grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(3–4), 845–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.679931

- Borras, S.M., Franco, J.C., & Wang, C. (2013). The challenge of global governance of land grabbing: Changing international agricultural context and competing political views and strategies. Globalizations, 10(1), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2013.764152

- Briassoulis, H. (2019). Analysis of land use change: Theoretical and modeling approaches. Web book of regional science (3rd ed.). Lesvos.

- Chilombo, A., 2019. Understanding socio-economic and environmental impacts of large-scale land acquisitions: A case study of Nansanga Farm Block in Zambia. University of Edinburgh PhD Thesis. https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/36391.

- Chilombo, A., Fisher, J.A., & Van Der, H.D. (2019). A conceptual framework for improving the understanding of large scale land acquisitions. Land Use Policy, 88, 104184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104184

- Coccossis, H.N., et al. (1991). Historical land use changes: Mediterranean regions of Europe. In M. Brouwer (Ed.), Land Use Changes in Europe (pp. 441–461). Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-3290-9_20

- Dauber, J., Brown, C., Fernando, A.L., Finnan, J., Krasuska, E., Ponitka, J., Styles, D., Thrän, D., Van Groenigen, K.J., Weih, M., & Zah, R. (2012). Bioenergy from “surplus” land: Environmental and socio-economic implications. BioRisk, 50(7), 5–50. https://doi.org/10.3897/biorisk.7.3036

- De Schutter, O. (2011). How not to think of land-grabbing: Three critiques of large-scale investments in farmland. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 249–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.559008

- Deininger, K. (2011). Challenges posed by the new wave of farmland investment. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 217–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.559007

- Deininger, K., & Byerlee, D. (2012). The rise of large farms in land abundant countries: Do They Have a Future? World Development, 40(1), 701–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.04.030

- Deininger, K., Byerlee, D., Lindsay, J., Norton, A., Selod, H., & Stickler, M. (2011). Rising global interest in Farmland: Can it yield sustainable and equitable benefits? World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8591-3

- Dell’Angelo, J., D’Odorico, P., Rulli, M.C., & Marchand, P. (2017). The tragedy of the grabbed commons: Coercion and dispossession in the global land rush. World Development, 92, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.005

- Dewees, P.A., Campbell, B.M., Katerere, Y., Sitoe, A., Cunningham, A.B., Angelsen, A., & Wunder, S. (2010). Managing the Miombo Woodlands of Southern Africa: Policies, incentives and options for the rural poor. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research, 2(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/19390450903350846

- Ehrlich, P., & Ehrlich, A.H. (2009). “The population bomb” revisited. Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development, 1(3), 21–24. https://www.populationmedia.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/Population-Bomb-Revisited-Paul-Ehrlich-20096.pdf

- Frost, P. (1996). The ecology of Miombo woodlands. (B. Campbell, Ed.) In Miombo Transit. Woodlands Welf. Africa (pp. 266).CIFOR. http://books.google.com/books?hl=nl&lr=&id=rpildJJVdU4C&pgis=1

- German, L., Schoneveld, G., & Mwangi, E. (2013). Contemporary processes of large-scale land acquisition in Sub-Saharan Africa: Legal Deficiency or Elite Capture of the Rule of Law? World Development, 48, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.03.006

- Gironde, C., Golay, C., & Messerli, P. (Ed) 2014. Large-scale land acquisitions: Focus on South-East Asia, The Political Economy of Development. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472553867.ch-008

- GRZ, 2005. Farm block development plan (2005–2007). (unpublished document)

- Hall, R. (2011). Land grabbing in Southern Africa: The many faces of the investor rush. Review of African Political Economy, 38(128), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2011.582753

- Hersperger, A.M., Gennaio, M., Verburg, P.H., & Burgi, M. (2010). Linking land change with driving forces and actors: Four conceptual models. Ecology and Society, 15(4). http://www. ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art1/Research

- Jayne, T.S., Chamberlin, J., & Headey, D.D. (2014). Land pressures, the evolution of farming systems, and development strategies in Africa: A synthesis. Food Policy, 48, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.05.014

- Lambin, E.F., & Meyfroidt, P. (2011). Global land use change, economic globalization, and the looming land scarcity. PNAS, 108(9), 3465–3472. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100480108

- Larder, N. (2015). Space for pluralism? Examining the Malibya land grab. Journal of Peasant Studies, 42(3–4), 839–858. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1029461

- Li, T.M. (2014). What is land? Assembling a resource for global investment. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(4), 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12065

- Long, H. (2020). Land use transitions and rural restructuring, land use transitions and rural restructuring in China. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4924-3_9

- McCarthy, J.F., Vel, J.A.C., & Afiff, S. (2012). Trajectories of land acquisition and enclosure: Development schemes, virtual land grabs, and green acquisitions in Indonesia’s Outer Islands. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 521–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.671768

- Messerli, P., Giger, M., Dwyer, M.B., Breu, T., & Eckert, S. (2014). The geography of large-scale land acquisitions: Analysing socio-ecological patterns of target contexts in the global South. Applied Geography, 53, 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.07.005

- Müller, D., & Munroe, D.K. (2014). Current and future challenges in land-use science. Journal of Land Use Science, 9(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2014.883731

- Nalepa, R.A., & Bauer, D.M. (2012). Marginal lands: The role of remote sensing in constructing landscapes for agrofuel development. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.665890

- Neef, A., & Singer, J. (2015). Development-induced displacement in Asia: Conflicts, risks, and resilience. Development in Practice, 25(5), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2015.1052374

- Oberlack, C., Tejada, L., Messerli, P., Rist, S., & Giger, M. (2016). Sustainable livelihoods in the global land rush? Archetypes of livelihood vulnerability and sustainability potentials. Global Environmental Change, 41, 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.10.001

- Parenti, C. (2015). The 2013 ANTIPODE AAG lecture the environment making state: Territory, nature, and value. Antipode, 47(4), 829–848. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12134

- Peemans, J.-P. (2014). Land grabbing and development history: The Congolese (RDC) experience. In Ansoms, A. & Hilhorst, T. (Eds), Losing your land: Dispossession in the Great Lakes (pp. 11–35). http://hdl.handle.net/2078.1/168744

- Ryan, C.M., Pritchard, R., McNicol, I., Owen, M., Fisher, J.A., & Lehmann, C. (2016). Ecosystem services from southern African woodlands and their future under global change. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371(1703), 20150312. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0312

- Schoneveld, G.C. (2017). Host country governance and the African land rush: 7 reasons why large-scale farmland investments fail to contribute to sustainable development. Geoforum, 83, 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.007

- Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods a Framework for Analysis. IDS Working Paper (Vol. 72). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1110037

- Shepard, D. (2012). Situating private equity capital in the land grab debate. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(3–4), 703–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.674941

- Sikor, T., Auld, G., Bebbington, A.J., Benjaminsen, T.A., Gentry, B.S., Hunsberger, C., Izac, A.-M., Margulis, M.E., Plieninger, T., Schroeder, H., & Upton, C. (2013). Global land governance: From territory to flow? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(5), 522–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.06.006

- Smith, R.E. (2004). Land tenure, fixed investment, and farm productivity: Evidence from Zambia’s southern province. World Development, 32(10), 1641–1661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.05.006

- Storrs, A.E.G. (1995). Know Your Trees: Some Common Trees Found in Zambia. Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU), Nairobi.

- Taylor, M., & Bending, T. (2009). Increasing commercial pressure on land: Building a coordinated response. In International Land Coalition Discuss. Pap (pp. 1–25).

- Turner, L., Lambin, E.F., & Reenberg, A. (2007). The emergence of land change science for global environmental change and sustainability. PNAS, 104(52), 13070–13075. https://doi.org/www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0704119104

- Verburg, P.H., Crossman, N., Ellis, E.C., Heinimann, A., Hostert, P., Mertz, O., Nagendra, H., Sikor, T., Erb, K.-H., Golubiewski, N., Grau, R., Grove, M., Konaté, S., Meyfroidt, P., Parker, D.C., Chowdhury, R.R., Shibata, H., Thomson, A., & Zhen, L. (2015). Land system science and sustainable development of the earth system: A global land project perspective. Anthropocene, 12, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2015.09.004

- Verburg, P.H., Erb, K.H., Mertz, O., & Espindola, G. (2013). Land system science: Between global challenges and local realities. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(5), 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.08.001

- Whitfield, S. (2016). Adapting to climate change uncertainty in African agriculture: Narratives and knowledge politics. Routledge.

- Wolford, W., Borras, S.M., Hall, R., Scoones, I., & White, B. (2013). Governing global land deals: The role of the state in the rush for land. Development and Change, 44(2), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12017

- Woodhouse, P. (2012). New investment, old challenges. Land deals and the water constraint in African agriculture. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39, 777–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.660481

- Zoomers, A. (2010). Globalisation and the foreignisation of space: Seven processes driving the current global land grab. Journal of Peasant Studies, 37(2), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066151003595325