ABSTRACT

During a civil war and its aftermath, rival powerholders frequently engage in decision-making over land use, for example, via land acquisitions or legal reforms. This paper explores how powerholders influence land use decision-making and what their engagement implies for territorial control. We analyse three cases of land use changes in Myanmar’s south between 1990 and 2015, where the Myanmar state and an ethnic minority organization fought over territorial control. We gathered qualitative data with a mix of methods and visualised actor networks and institutions. Our analysis reveals that the state managed to increasingly control decision-making over local land use from a distance by employing actor alliances and institutions such as laws and incentives, whereas the ethnic organization lost influence. We conclude that engaging in land use decision-making plays a crucial role in influencing the outcomes of a civil war and that it represents a form of war- and state-making.

1. Introduction

Civil wars are widespread, cause tremendous suffering, impact negatively on economic development, political stability, and environment (Baumann & Kuemmerle, Citation2016; Sambanis, Citation2002). They typically involve the state and rebels as combatants competing over territorial control and sovereignty (Doyle & Sambanis, Citation2000). During subsequent periods of peacemaking, i.e. the transition from armed fighting to peace agreements with ceasefires (Doyle & Sambanis, Citation2000), powerholders such as states frequently attempt to secure further territorial control (Diepart & Dupuis, Citation2014; Klem, Citation2014). One way for rival powerholders to gain control over land and thus territory is by influencing decision-making processes over land use, land use changes (LUCs), land access, and land tenure (Bassett & Gautier, Citation2014; Diepart & Dupuis, Citation2014; Klem, Citation2014) – phenomena which also constitute relevant fields of research in land system science (Global Land Programme, Citation2016; Verburg et al., Citation2013). In the present study, we refer to land use decision-making (LUDM) as all these collective processes in which decisions over access to and use of land are made by various interacting actors across scales and sectors. Unlike the more agent-based understanding of LUDM (emphasizing individual cognitive decision-making by land users), our governance-oriented understanding of LUDM thus focuses on issues such as the following: the role actor networks play in decision-making processes; what actors exert influence on others in these processes; what interests they pursue; and/or who is included in (or excluded from) a decision-making process. Similar to the concept of land access (Ribot & Peluso, Citation2003; Sikor & Lund, Citation2009), our governance-oriented understanding of LUDM also enables us to shed light on crucial aspects of power and authority. Social scientist Charles Tilly introduced the terms ‘war-making’ and ‘state-making’, both intertwined and describing processes in which powerholders try to eliminate or neutralize their rivals inside a certain territory (Castañeda et al., Citation2017). Compliant with Tilly’s argument, state authorities have been found to delineate protected forests with the aim of controlling and weakening insurgent groups who live and operate within them (Peluso & Vandergeest, Citation2011). Similarly, scholars (e.g. Thein et al., Citation2018; K. Woods, Citation2011) have pointed out how, in recent decades, the Myanmar state used agricultural land acquisitions in the country’s north to weaken its rivals. Similarly, in Indonesia and Colombia, large-scale oil palm plantations have been seen to increase the territorial power of the respective state (Schaffartzik et al., Citation2016; Vargas & Uribe, Citation2017).

Tilly does not provide a definition of the term ‘powerholder’. In the present study, we use the term ‘powerholder’ to refer to a political, armed organization that holds and exerts political, economic, institutional, and social influence and control vis-à-vis other actors. Consequently, in the context of civil war, the powerholders are the state, on one side, and the opposing rebels, on the other, which represent and govern a certain segment of society. This understanding of the term powerholder makes it possible to include non-state actors and/or self-claimed governments in the analysis, setting aside the assumption that only state authorities can be the legitimate holders of power.

There are several ways in which powerholders can control and engage in LUDM to steer or determine eventual land use, access, or tenure. For instance, controlling LUDM involves territorial projects such as national parks or zones with special economic functions (Bassett & Gautier, Citation2014), land legalization processes, as well as violence (or threats thereof) (Peluso & Lund, Citation2011). Similarly, in ceasefire and post-war periods, powerholders often engage in land reforms (Samuels, Citation2006) and state territorialization projects including constructing strategic roads to previously isolated regions, delineating zones with changing land uses and demarcating forests (Klem, Citation2014; Peluso & Vandergeest, Citation2011).

To control LUDM via territorial projects, powerholders often rely on networks of actors that help govern local areas from a distance (Lestrelin, Citation2011). Such ‘territorial alliances’ composed of actors located in diverse social, institutional, and geographic locations can be decisive for territorial control (Bassett & Gautier, Citation2014). Territorial alliances can be driven from above, as in territorialization projects using large-scale land acquisitions granted by a state (K. Woods, Citation2011). Territorial alliances can also be locally-driven. In Senegal, for example, an alliance of farmers, NGOs, state bureaucrats, and traditional authorities managed to defend farmers’ land from urban development (Bassett & Gautier, Citation2014). To understand the functioning of these networks of territorial alliances and their role in LUDM, it is necessary to analyse the actors involved and their interests.

Formal and informal institutions, defined as rules governing the behaviour of actors, largely determine human–nature interactions (Biermann et al., Citation2009). For example, land reforms or making forests into protected areas alter how people use land and forests. In this way, institutions regulate territories and decision-making over their purpose (Sikor et al., Citation2013), and, thus, processes of LUDM. At the same time, powerholders can rely on, or even create, different institutions to achieve their aims.

In recent years, scholars have begun considering how state interests in civil war and ceasefire contexts influence LUCs such as commercial land acquisitions or delineation of protected areas, but there are still very few studies investigating possible links. Additionally, the existing literature rarely addresses the role of powerholder engagement in LUDM on the outcomes of civil wars. Further, there remains a lack of understanding of the actors involved in and excluded from LUDM, their interests and alliances, and the effects of institutions on land uses in times of war and ceasefire. Post-war, it is crucial for durable peace efforts to address questions of LUDM, including changes in land use, access, and tenure (Diepart & Dupuis, Citation2014; Unruh & Williams, Citation2013). To address such questions, post-war powerholders must first disentangle and understand their civil-war legacies and any reforms made in the immediate aftermath of war – the ceasefire period – before they can effectively negotiate and (re-)build a durable peace. For this, evidence of wartime, ceasefire period, and post-war LUDM is needed, including changes in land use, access, and tenure.

Against this background, the present article focuses on LUDM during wartime and the ceasefire period. Its overall goal is to explore (1) how rival powerholders make use of actor networks and institutions in order to influence LUDM; and (2) the implications of their engagement in LUDM in terms of resulting territorial control. More specifically, our investigation focuses on Myanmar, which experienced a long civil war lasting from the 1960s until the early 2010s and then finally began a transition with various ceasefire agreements between 2011 and 2015 – accompanied by critical land reforms (see section 2). In a study of a typical conflict-ridden borderland, we analyse three cases of changing LUDM between 1990 and 2015 (covering wartime and the ceasefire periodFootnote1). The study is guided by the following research questions: (A) What were the main LUCs between 1990 and 2015? (B) What were the changes in LUDM leading to these main LUCs? The latter research question will shed light on (i) which actors were involved in the changing LUDM by being part of the actor network that ultimately fostered the LUC; (ii) what overall agenda and interests these actors had when engaging in LUDM; (iii) who was eliminated from the changing LUDM; (iv) what institutions influenced the changing LUDM; and (v) who did or did not share and adhere to these institutions. In part one (section 4.1), we analyse each LUDM case individually. In part two (section 4.2), we compare the three cases of LUDM to capture implications of the powerholders’ engagement in LUDM for their territorial control.

2. Context and case study

2.1. Historical background of the civil war and land governance in Myanmar

Lasting from the 1960s into the 2010s, Myanmar’s civil war was one of the world’s longest-running such conflicts (Brenner & Schulman, Citation2019). In 1962, General Ne Win seized power in a coup d’etat. He expanded the military by recruiting mainly Bamar males. This and later military regimes became markedly ethno-nationalist in their character, envisioning a unified Myanmar based on Bamar Buddhist identity (Jolliffe, Citation2016). The central state removed local governments of previously federal, ethnic states, and developed a deep military state. Shan, Kachin, Karen, and other ethnic armed movements rose in power and armed conflicts escalated dramatically across the country (Jolliffe, Citation2016). Likely, the civil war was rooted in the precolonial divide between the country’s centre and its borderlands, according to which the ethnic majority of Bamar have lived and ruled in the centre of today’s Myanmar and other ethnic groups have long governed themselves in the more mountainous regions of today’s borderlands (Brenner & Schulman, Citation2019). British and later Japanese rule and occupation deepened this divide in various ways. Decided to be united in one multi-ethnic country following independence in 1948, the ethnic minorities in the mountainous borderlands grieved over their lack of influence in political decision-making, absence of development in their areas, and repression of their cultural and religious freedom, compared to the ethnic majority of the Bamar in the country’s centre (Kramer, Citation2015). In contrast, the authoritarian Bamar-led regime developed a self-image of being the guardians of the Myanmar state, with the central military considered the main actor responsible for unifying all ethnic groups in one Myanmar (Brenner & Schulman, Citation2019; Jones, Citation2014). At the same time, the inequitable distribution of resources between the Burman centre and the resource-rich ethnic borderlands is believed to be the key driver of ethnic conflict in Myanmar (Kramer, Citation2015). The military-led central state increasingly conducted so-called development projects in the borderlands such as agribusiness, resource extraction ventures (minerals, precious stones, natural gas etc.), and hydropower facilities (Buchanan et al., Citation2013). These projects typically exported the resources to provide revenue to the state as well as income to local-level commanders from the Myanmar military and rebel groups’ splinter groups (Jolliffe, Citation2016). Several scholars and civil society representatives argue that the Myanmar military-led state used these development projects during civil war and ceasefires as a means to expand the state’s influence into government-non-controlled areas of the borderlands (Barbesgaard, Citation2019; Buchanan et al., Citation2013; Ferguson, Citation2014; Gum Ja Htung, Citation2018; Kenney-Lazar, Citation2016; Thein et al., Citation2018; K. Woods, Citation2011; K. M. Woods, Citation2019).

Following pro forma elections in November 2010, a quasi-civilian government ruled between 2011 and 2015, still under the strong influence of the military. It negotiated various regional ceasefire agreements after 2011 and oversaw a nationwide ceasefire agreement in 2015 (Lundsgaard-Hansen et al., Citation2018; Schneider et al., Citation2020). Once these ceasefire agreements were finally reached, conflicts declined between the Myanmar military and many (but not all) ethnic armed organizations (rebel groups), and internally displaced people and refugees returned to their homes in some areas. However, many still remain in provisional camps due to loss of land to land grabs during their absence, environmental damage of their natural resource base as a cause of war, fears of violence, eroded infrastructure or social institutions (Displacement Solutions, Citation2013; KHRG, Citation2019; Transnational Institute, Citation2017). The quasi-civilian government also issued several land-related reforms (Lundsgaard-Hansen et al., Citation2018; Schneider et al., Citation2020), which ushered in new land-related policies, laws, and committees aimed at managing land use and tenure centrally and formally (instead of customarily). However, pre-ceasefire problematic laws, power structures, and institutions from the past were not dissolved (Conservation Alliance of Tanawthari, Citation2018; Franco et al., Citation2015; Kenney-Lazar, Citation2016; Mark, Citation2016; Oberndorf, Citation2012).

From 2016 to early 2021, Myanmar was led by a democratically elected civilian government, tasked with resolving manifold legacies from the civil war and ceasefire period, while still under the strong but largely hidden influence of the military. Centralization of state authority continued (Stokke & Aung, Citation2020) and land uses and changes implemented during war remained, including agricultural concessions and top-down conservation zones in the borderlands. Myanmar found itself mired in countless unresolved land disputes and a situation of legal pluralism and ambiguity (Mark, Citation2016); a common state of affairs among post-conflict societies (Unruh & Williams, Citation2013).

Since the most recent military coup on 1 February 2021, the country is again in turmoil, appearing on the brink of another civil war.

2.2. Civil war and land governance in the case study area

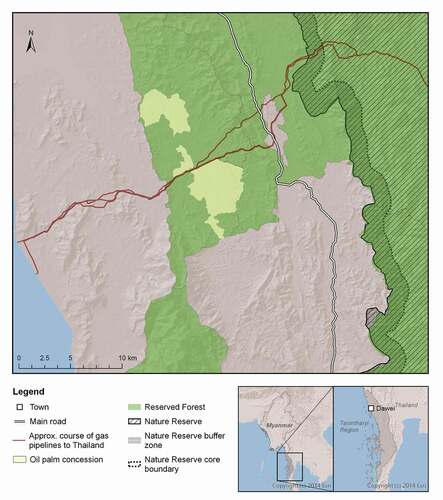

Our case study area is located in Yebyu Township, northern Tanintharyi Region, in Myanmar’s south (see ). It is situated in one of the country’s borderlands where armed conflict prevailed until 2011, in particular between two parties: the Myanmar state and the rebel group Karen National Union (KNU; an ethnic minority political organization) (Jolliffe, Citation2016). After independence, the Karen people’s request to form their own state to obtain territorial sovereignty was ignored by the Burmese and British leaders, resulting in a Karen rebellion led by the KNU (Brouwer & van Wijk, Citation2013). The military coup in 1962 worsened the tensions. For decades, the two rivals fought for territorial control, first in various areas of Myanmar, and later mainly in the southeast of Myanmar.Footnote2 In the 1990s, the Myanmar military set up a main base in the case study area for several years, during which time Karen ethnic people suffered serious human rights violations by (Bamar) soldiers, including rape of women, torture, killing, and denying access to cultivated plots, markets, and food.Footnote3 Moreover, in both case study villages (Bamar and Karen), residents were forced to provide food to troops on both sides, and were forced to work as porters or construction labourers for the Myanmar military.

The transformation to a quasi-civilian government in 2011/2012 led to the signing of a durable regional ceasefire agreement between the Myanmar state and the KNU – followed by a national agreement in 2015. At some point, the KNU altered its request and communicated in its strategic mission that there should be a Karen state with a just and fair territory and self-determination within the Federal Union of Myanmar (Karen National Union, Citation2018).

To date, northern Tanintharyi Region remains a mixed control area, meaning that both the Myanmar state as well as the KNU claim sovereignty over the territory.Footnote4 The territory requested by the KNU is about three times the size of what the Myanmar state defines as the ‘Karen State’, and includes Tanintharyi Region in Myanmar’s south (for maps, see KHRG, Citation2018). Both factions have their own – in part rival – land governance systems. In our study area, ethnic Bamar villages usually follow the governance system of the Myanmar state, while Karen villages try to follow both systems.

2.3. Case study villages

In order to avoid exposing them to possible political repercussions or other consequences, we refer to our case study villages as Village A and Village B and do not share their exact location. Village A has a predominantly Karen-Christian population, whereas Village B is mainly Bamar-Buddhist. Village A lies in the immediate vicinity of an oil palm concession and in a zone considered ineligible for land use certificates (use rights) by the Myanmar state,Footnote5 having been previously officially declared a ‘Reserved Forest’ area (a legacy from colonial times) without allowance for agricultural cultivation of land (see ). By contrast, residents of Village B can apply for formal land use certificates issued by the Myanmar state for agricultural use (since 2012), as it is situated in a zone where agriculture is legally permitted. Further, Village B is situated at the edge of a nature reserve.

3. Methodology

3.1. Conceptual framework

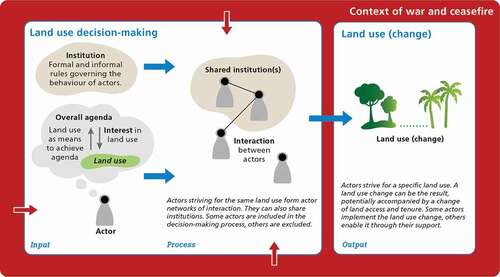

In the present study, we employ a governance-oriented understanding of LUDM. In so doing, we use the term LUDM to refer to all the collective processes, in which decisions over land use, LUCs, land access, and land tenure are made by various actors across scales and sectors. In this study, we conceive of land users as belonging to a dynamic system in which various actors interact across scales and sectors while articulating claims to land. We argue that these actors pursue their own agenda when interacting with each other and that they adhere to a certain set of (formal and/or informal) institutions. illustrates how we conceptualize LUDM. In our conception, LUDM encompasses inputs to the decision-making process as well as the process of decision-making itself, in which various actors interact. The output of LUDM is a particular land use or a change thereof (an LUC), possibly including a change in land tenure or access, and thus control over land.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework of how land use decision-making leads to a particular land use or land use change, potentially including a change of land access and tenure (bolded terms form the major elements in the data analysis)

As inputs to LUDM (, left side), two components are crucial: First, institutions can be formal such as written policies, laws, or land tenure rules; or they can be informal, such as traditional or customary rights (Biermann et al., Citation2009). Second, actors are guided by their own stakes when engaging in LUDM (Lundsgaard-Hansen et al., Citation2018; Wiesmann et al., Citation2011). We differentiate between an actor’s overall agenda (broader goal in the context of war and/or the ceasefire period, e.g. survival), on the one hand, and the actor’s specific interest in a particular land use (e.g. subsistence food production), on the other, which helps to achieve his or her overall agenda (see ). Each actor generally has one overall agenda, but several narrower interests in various land uses.

During the process of decision-making (see ), actors can form networks of interactions (Borgatti et al., Citation2013; Fischer et al., Citation2017), which we refer to as ‘actor networks’ (see section 3.3). In particular, the actors may form alliances (Bassett & Gautier, Citation2014) and collaborate towards implementation of common LUC when they have a shared interest in the same potential land use. At the same time, actors may jointly adhere to one or more shared institutions. Conversely, actors may be excluded from the decision-making process by not interacting (or by being prevented from interacting) in particular actor networks, or by not sharing certain institutions. The actors relevant to LUDM, and thus potentially included in such networks, range from local farmers to international organizations; the relevant institutions range from informal customary systems to national statuary laws. Notably, the temporal and spatial occurrence of decision-making processes varies widely. Key processes may occur to large extent in a single meeting, or they may slowly evolve over several years.

The output of LUDM (, right side) is the realization of the envisaged land use and potential LUC, which can include changes in land tenure or land access, and thus in control over land.

In addition, the context such as war or ceasefire usually influences LUDM at any stage and time (, red arrows) (Wiesmann et al., Citation2011).

3.2. Data collection

Data collection lasted from April 2016 to May 2018 and followed four steps. In the first step, we facilitated eight participatory focus group discussions in 2016–2017 in our two selected villages, including between 11 and 28 participants in each discussion (for selection of villages see Appendix A.1). The focus group participants were local residents (experienced farmers, elderly villagers, village heads, plantation workers), men and women alike, who represented particular land uses. In the discussions, we first identified the main LUCs (outputs of LUDM) in and around the villages from the perspective of participants (see Appendix A.3. for criteria of ‘main’ LUCs). The spatial boundary was not precisely predetermined (e.g. administrative village boundary), but rather explicitly left open to enable local residents to interpret what they perceived as their village’s surrounding.Footnote6 We then collected data – during the focus group discussions – on the process of LUDM preceding each LUC by facilitating and recording a narrative dialogue about past events and by drawing causal loop diagrams. We did not predetermine the temporal starting point of analysis. Instead, the open narrative dialogue exercise revealed that all the main LUCs began occurring in the late 1990s. Only afterwards did we define the time points for the analysis (see section 3.3.). This procedure of narrative dialogue served (a) to establish a timeline of events for each case from its beginning; (b) to identify the new dominant actors (see definition below); and (c) to identify the initial land users before the changes occurred. Identification of the new dominant actors in LUDM and the initial pre-change land users gave us a starting set with which we could disentangle the wider network of actors involved in LUDM. Given the high importance of organizations in LUDM – particularly in terms of potential influence – we chose to focus our analysis on collective and organizational actors (Fischer et al., Citation2017) rather than on individual people.

In the second step, we conducted an actor survey to collect further data on the LUCs (the outputs of LUDM) and to investigate the inputs and processes of LUDM that led to the LUCs. The starting set were the dominant actors in LUDM as well as the initial land users as identified in the focus groups. From there, we applied a snowball sampling technique (Reed et al., Citation2009) to identify subsequent sets of actors from the first set of actors. We developed the survey in English and then translated it into Burmese. The survey included, among other aspects, questions on additional facts of the LUCs, the overall agenda of actors, their interest in certain land uses, their interactions with other actors (operationalized as exchanges of goods, financial capital, information, or human capital (based on Bennett et al., Citation2012; Wiesmann et al., Citation2011), as well as the formal and informal institutions to which they adhered (see survey structure in Appendix A.2.). The face-to-face survey sessions with respondents lasted 50–150 minutes. They were mainly conducted in Burmese and a few in English. Interviewees’ responses about interactions and shared institutions were used to identify the next set of actors/respondents. We then repeated the snowball procedure with the newly identified actors, ultimately conducting a total of 68 actor surveys. Two aspects served to delimit the scope of the actor network and thus define the spatio-temporal boundaries of the system under study: Firstly, we applied relevancy criteria to data collection, as we explicitly chose not to predefine the boundaries of the actor network. In general, interactions (with the next actor) and institutions had to be directly or indirectly linked to and consequential for the LUCs under focus to qualify for inclusion (see Appendix A.3. for relevancy criteria). Secondly, practical considerations such as finite time and money for travelling abroad placed limits on data collection, as did the lack of accessible data or respondents with respect to certain network actors (see Appendix A.4.).

Our third step involved filling in missing data on actors that were identified by the snowball procedure, but who did not respond to the survey, or did so only in part, as a result of lack of knowledge, refusal, or unavailability. Out of 78 actors in total contacted for the survey, 10 did not respond and 12 only partially responded (see Appendix A.5.). In order to fill gaps in our data and address uncertainties and contradictions, we conducted qualitative semi-structured expert interviews (44 face-to-face, 7 by phone) with third partiesFootnote7 (see Appendix A.5.) in addition to consulting scientific and grey literature. For example, the surveyed rubber smallholders and traders were unable to name and explain the Myanmar state’s influential economic and institutional incentives for rubber production. Thus, we conducted interviews with several rubber experts in Myanmar to obtain data on these relevant institutions. See Appendix A.4. for more detailed information on procedures and actors related to data gaps.

Finally, in the fourth step – and as an added means of setting the spatio-temporal system boundary – we narrowed down for further analysis a selection of only those actors representing one of the following roles in the LUDM process or the resulting LUC:

Powerholders and their armed forces: In the present study, the term ‘powerholder’ (Castañeda et al., Citation2017)Footnote8 refers to the Myanmar state or the KNU, who competed over territory in southern Myanmar and continue to hold different forms of power over the territory and people. The Myanmar state, the KNU, and their respective armed forces are represented in the actor networks, regardless of whether they occupy a specific role vis-à-vis the LUDM or not. This is necessary to explore the powerholders’ engagement in LUDM.

Initial land users before any changes occurred: Smallholders in 1990 who mainly practiced shifting cultivation.

Dominant actors in LUDM: (a) New land users and, thus, implementers of LUC: Those actors, who invested their resources to implement LUC, administered LUC, and claimed tenure of corresponding land. (b) Key enablers: Those actors without whose involvement in LUDM the LUC would not have been possible, for example, by creating a decisive institution, providing critical funds.

Note that the initial land users, powerholders, and their armed forces can also be implementers and key enablers. For limitations of the study stemming from data collection, see section 5.2.

3.3. Data analysis

For the analysis, we also proceeded in four steps: First, we sought to identify the actors involved in and excluded from LUDM leading to the main LUCs. This analysis revealed how the rival powerholders made use of actor networks, which actors took over decision-making from whom, and who was eliminated from decision-making. Second, we analysed the overall agenda and interests of those actors who newly dominated LUDM. Third, we scrutinized what formal and informal institutions the powerholders and other actors created or used when influencing decision-making. Fourth, we compared the three cases of LUDM.

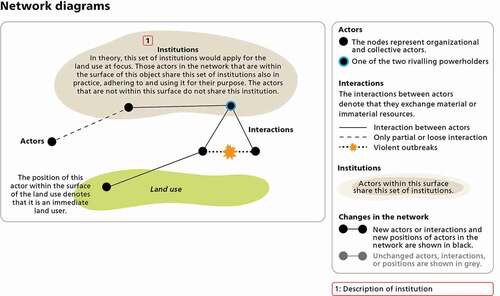

Based on our conceptual framework, we visualized the process of LUDM in the form of a complemented actor network as shown in . The following elements are integrated in the complemented actor network diagrams of LUDM (short: ‘network diagrams’): (i) The green ‘surface’ beneath the actor network represents the land use resulting from the LUDM (output). (ii) The nodes represent the actors. The two powerholders are explicitly highlighted. (iii) The ties between actors represent interactions encompassing the exchange of goods, financial capital, information, and/or human capital. (iv) The shades behind actors represent formal as well as informal institutions representing rules that in theory would apply to the land use under focus. Actors covered by a given shade adhere to and share that institution also in practice. Actors outside a given shade do not adhere to and share the institution in practice.

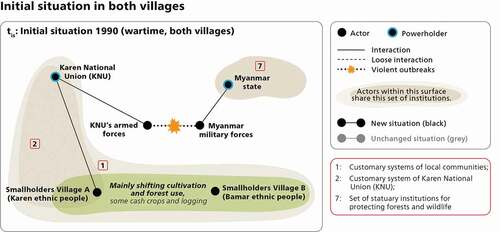

Figure 3. How to read the network diagrams visualizing actor networks and institutions in the land use decision-making process

We analysed the LUDM at different time points (t) in order to see how the three cases of LUDM evolved over time. Based on the narrative dialogue exercise (see section 3.2.), we refer to the year 1990 as the ‘initial situation’ of LUDM in the case study area, the years 1998–2010 as the ‘wartime’ era when major changes began, and the years 2011–2015 as the ‘ceasefire period’, as the warring parties in the case study area ceased to engage in armed conflict. Accordingly, the first time point (tis) represents the initial situation of LUDM in 1990 (initial situation = LUDMis). This baseline initial situation is identical in all three cases, as changes only occurred afterwards. Then, for each case of changing LUDM (oil palm = LUDMop; nature reserve = LUDMnr; commercial agriculture = LUDMca), the beginning is captured in 1998–2010 (wartime; top1, tnr1, tca1). The later time points represent the situation of each LUDM case in 2011–2015 (ceasefire period; top2, tnr2, tca2).

4. Results

Presented in a narrative style, the following subsections describe the inputs and the process of LUDM leading to the main LUCs. The narratives do so by highlighting the main actors in LUDM one after the other, as well as their overall agenda, their interest in particular land uses, and their interactions and shared institutions with other actors. In this way, the following subsections explain how the powerholders engaged in LUDM and how they eliminated or neutralized their respective rival. For a more detailed overview of the inputs to LUDM in each case, see Appendix B.

4.1. The three cases of changing land use decision-making

The initial land users in 1990 (smallholders) practiced mainly shifting cultivation and used some forest products. They were the only land users and thus the dominant actors in LUDM. They shared their communities’ customary systems, practised by Karen ethnic people (Village A) in accordance with the customary system of the KNUFootnote9 (tis, ). The smallholders pursued the same overall agenda and interest in the initial land use across villages, namely that of surviving the civil war and having enough food.

In the initial situation around 1990 (LUDMis), both powerholders (Myanmar state and KNU) claimed territorial control in the case study area. The KNU followed its overall agenda of a democratic, Federal Union of Myanmar guaranteeing the equality and self-determinationFootnote10 of all ethnic nationalities, including the Karen people. Moreover, it aimed at a Karen state with a just and fair territory, independent within a hoped-for decentralized federation (Jolliffe, Citation2016; Karen National Union, Citation2015, Citation2018). Meanwhile, the Myanmar state pursued its overall agenda of building a united, disciplined, multi-ethnic nation, with the military (a synonym for the Myanmar state at that time) being perceived as the main actor for building this union (Brenner & Schulman, Citation2019; Jones, Citation2014). However, the Myanmar state was physically further away from the case study area than the KNU. Generally, smallholders in both villages had virtually no interaction with Myanmar state representatives. In Village A, smallholders interacted with KNU representatives.

In Village A, the KNU was a relevant actor at that time since it governed not only questions of land (thus influencing LUDMis), but also those of social and cultural life (Jolliffe, Citation2016). Interpreting from literature, the main interest of the KNU in land use ca. 1990 was most likely that of enabling all Karen and other ethnic people to use their land consistent with principles of self-determination and equality (Jolliffe, Citation2016; Karen National Union, Citation2018, Citation2015).

In the early 1990s, the physical presence of armed troops sharply increased among both powerholders, partly connected to the LUCs that followed. Between the late 1990s and 2011, the KNU withdrew continuously towards the Thai border, operating with diminished links to its ethnic people in Village A.

In the focus groups, we identified three main LUCs. The changes in LUDM leading to these LUCs started in the 1990s and can be summarized as follows:

LUDMop (only in Village A): A military company received a land concession and converted forest, shifting cultivation areas, and some smallholder cash crop plantations into a large-scale oil palm monoculture. Local smallholders lost access to land.

LUDMnr (only in Village B): International oil and gas companies sponsored the implementation of a 170,000 hectare (ha) nature reserve (affording stricter protection status than the prior ‘Reserved Forest’). Conservation enforcement was low during the war but increased during the ceasefire period. A semi-state-owned conservation organization was in charge of implementing and monitoring the nature reserve. Smallholders gradually lost access to the forest.

LUDMca (in both villages): A regional private agribusiness, many regional land speculators, and local smallholders contributed to the expansion of private sector commercial agriculture – predominantly small- or medium-scale cultivation of rubber and betel nut – at the expense of forest and shifting cultivation.

4.1.1. Oil palm

Actors included in LUDMop and relevant institutions:

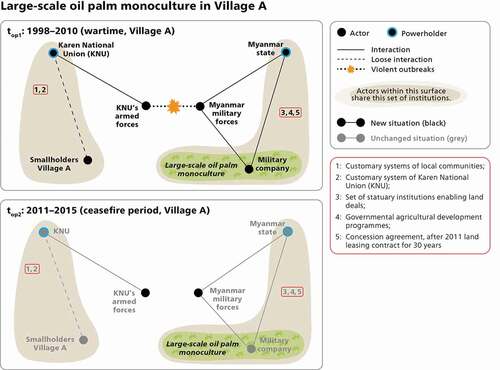

The implementer of the LUC and thus a dominant actor in LUDMop was a military company (see ) who had received a large-scale land concession from the Myanmar state in the late 1990s (and a more formal land lease contract in 2011). The military company was interested in producing palm oil for use in its own soap factory. The company belonged to a military-owned conglomerate, which pursued the overall agenda of guaranteeing the welfare of military personnel and their families, in addition to creating jobs and supporting regional development.

Figure 5. Land use decision-making over the large-scale oil palm monoculture around Village A (see also Appendix B.2. for more details on institutions)

The biggest key enabler and thus a dominant actor in LUDMop was the Myanmar state. Besides providing the land concession and lease contract to the company, the Myanmar state furnished other necessary institutions for this and other military-friendly companies to invest in oil palm cultivation in Tanintharyi Region (illustrated as shades in top1, ): A legal basis was facilitated with introduction of several land-related laws and state development programmes, paving the way for large-scale, industrial investments in agriculture. The Myanmar state incentivized companies to invest in oil palm cultivation (e.g. privileges in accessing mills). Respondents also stated that the Myanmar state required companies to exploit a land acquisition in Tanintharyi Region in return for permissions for business activities elsewhere.

The Myanmar state pursued particular interests when issuing oil palm concessions in Tanintharyi Region: First, as officially communicated by authorities, the state aimed at reducing its dependency on palm oil imports from abroad, in line with a national self-sufficiency plan (Lundsgaard-Hansen et al., Citation2018). The state expected to strengthen domestic production for the domestic market. Second, as explained in expert interviews, the state planned to open up the government-non-controlled area with tree plantations, in order to build physical infrastructure (e.g. roads), improve access to the contested area, and thereby improve territorial control – as well as generating development and helping to pacify the region. Consequently, vast areas of Tanintharyi Region were conceded for oil palm cultivation, forest was cleared, and villages were resettled.

Myanmar’s military forces were another dominant actor in LUDM. They provided security to the military company while it converted the land use, making the armed forces a key enabler of the LUC. Their interests in the oil palm monoculture in Village A are unclear, but the overall agenda of the Myanmar military in the case study area appears to be related to its ‘four cuts’ strategy of cutting off the KNU from food, funds, information, and potential local recruits (Brenner & Schulman, Citation2019; Jolliffe, Citation2016; K. M. Woods, Citation2019).

Actors and institutions excluded from LUDMop:

The initial land users (smallholders) did not agree with the LUC, but could not prevent it, as they were unable to tap into the military-dominated actor network of LUDM. They did not need to relocate, since the oil palm monoculture spared the main settlement area. Those directly affected by the LUC either began cultivating other land further away or began working as causal labourers, but not for the military company (the smallholders refused offers of labour from the military company for ideological as well as financial reasons). Some also fled to Thai refugee camps due to almost simultaneous outbreaks of armed fighting and repression of Karen residents. illustrates their lost access to the previously used land (node sits outside the green surface) and to LUDM for this specific land use (node is not connected to the decision-making actor network).

The KNU also opposed the LUC but could not stop it either. The KNU was excluded from LUDMop as well (not connected to the actor network, ). The customary systems (informal institutions), which were omnipresent in the initial situation, were ignored in LUDMop (see ).

Summary LUDMop:

Overall, LUDMop differs greatly from LUDMis. The Myanmar state dominated LUDMop, while the KNU was excluded. Further, the state managed to establish the physical presence of allies (military armed forces and military company) in the case study area via the LUC. In this way, the state increased its territorial control with LUDMop, while the KNU lost some of its control over the same territory.

4.1.2. Nature reserve

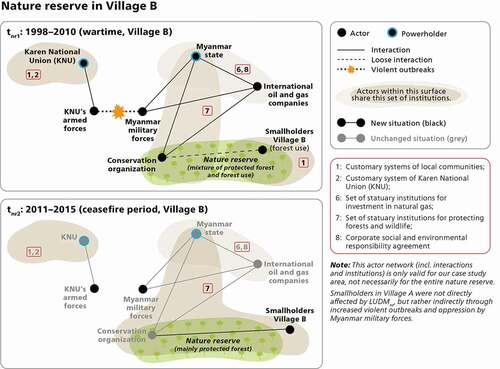

Actors included in LUDMnr and relevant institutions:

In 1996, the Myanmar state decided to establish the nature reserve, but they could not formally found it until security and financial concerns were settled in 2005 (Schneider et al., Citation2020). Tasked by the Myanmar state, the implementer of the nature reserve and thus a dominant actor in LUDMnr was a semi-state-owned conservation organization (see ). Based on its overall agenda of conserving biodiversity and protecting endangered species in collaboration with local communities, the conservation organization was genuinely interested in protecting the forest. During the war, implementation of the nature reserve was hampered by poor safety for staff. Following the regional ceasefire in 2012, however, the organization increasingly managed to implement the reserve, at least along most of the Western border of the reserve,Footnote11 where Village B is located.

Figure 6. Land use decision-making for the nature reserve near Village B (see also Appendix B.2. for more details on institutions)

A key enabler of the LUC and thus a dominant actor in LUDMnr were international oil and gas companies who made the nature reserve possible by substantially funding the conservation organization. Formally, this funding was part of a larger corporate social and environmental responsibility programme agreed with the Myanmar state, which explains the interest of the companies in the reserve. The environmental compensation was arranged in return for allowing company pipelines to cut through the biodiverse forest in order to deliver natural gas to Thailand (Schneider et al., Citation2020) – their overall agenda – as well as, to some extent, as a form of compensation for major human-rights violations in the early 1990s in connection with the pipeline construction (Barbesgaard, Citation2019; Lundsgaard-Hansen et al., Citation2018; K. M. Woods, Citation2019).

In the 1990s, Myanmar’s military forces accompanied the companies as security, making it an indirect but key enabler of the LUC. The interests of Myanmar’s military forces in the nature reserve per se are unclear. However, the troops actively fought the KNU’s armed forces, who posed a threat to the companies. The presence of Myanmar’s military troops also strongly intimidated local communities. Karen civilians reported numerous human rights violations by soldiers.

Again, the Myanmar state was a key enabler of the LUC and thus a dominant actor in LUDMnr. The corporate responsibility programme agreed upon by companies and the state (and created by the latter) represented a relevant formal institution for LUDMnr. Further, the Myanmar state provided the legal framework – including new forest-related laws – for creation of the nature reserve (see list of institutions in ). Overall, the Myanmar state had a vital interest in selling natural gas as a crucial source of state income, as did some military generals who pocketed considerable sums (Barbesgaard, Citation2019). At the same time, surveyed state department staff confirmed the state’s interest in better controlling and conserving forest resources due to high rates of deforestation in Myanmar. Notably, the forests designated for official protection were situated in the area where Karen ethnic people lived and the KNU operated. Whether the Myanmar state purposefully sought to classify the KNU stronghold as a conservation zone and therewith make existing Karen villages illegal was not openly expressed by any of our respondents. Nevertheless, other authors argue that ‘green territoriality’ was one strategy used by the Myanmar state to weaken the KNU (K. M. Woods, Citation2019).

Actors and institutions excluded from LUDMnr:

During civil war, the initial land users (smallholders) in Village B did not obey the restrictions on forest use inside the new nature reserve (node is still inside the green surface, tnr1, ). Only with the increased presence of the conservation organization after 2012 (due to heightened security), did the smallholders increasingly draw back from forest use inside the reserve, for fear of punishment. Accordingly, smallholders lost access to the forest inside the reserve (node lies outside the green surface, tnr2, ). However, they did not need to relocate further, as their village had already been forcefully moved (per order of the Myanmar state) from the inner forest to the main road in the course of civil war before 1990.

There was no prior informed consent with the KNU and the KNU disagreed with the forest protection status, since many Karen villages were located inside the demarcated zone. However, they could not prevent it from being issued.

Summary LUDMnr:

Overall, LUDMnr differs greatly from LUDMis. As in LUDMop, the Myanmar state dominated in LUDMnr, while the KNU was excluded. Once more, the Myanmar state increased the physical presence of its allies in the case study area via LUC. In this way, the state increased its territorial control. Notably, the situation might be different in villages located inside the nature reserve, the KNU stronghold area (see section 5.1.).

4.1.3. Commercial agriculture

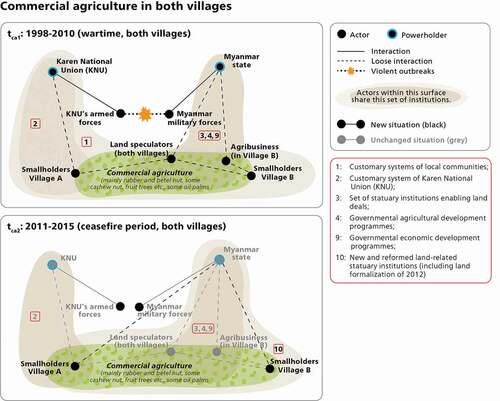

Actors included in LUDMca and relevant institutions:

Over the course of nearly 20 years, a variety of actors became implementers of the LUC from shifting cultivation/forest to commercial agriculture. Beginning in the late 1990s and in the 2000s (tca1, ), in particular a private sector agribusiness and countless regional land speculators (drawing especially urban elites) became implementers of the LUC. They all became pioneering dominant actors in LUDMca. According to their statements, they responded to state-made incentives (see shades of institutions 3, 4 and 9 in tca1, ) regarding land possession, commercial agriculture (such as abolishing rubber quotas; Lundsgaard-Hansen et al., Citation2018), or the announcement of the Special Economic Zone nearby (causing land prices to skyrocket). Moreover, they responded to the perceived promise of ‘white gold’, that is, rubber. While respecting the local communities’ customary system of land tenure, the agribusiness and speculators converted forest to cash crop monocultures, usually on the outskirts of the villages. While the agribusiness was rather interested in generating wealth through a commercial business, the land speculators’ interests were in acquiring land as a promising long-term investment, in addition to earning money by selling rubber liquid in the medium-term. When asked about their overall agenda, they all cited wanting to ensure a prosperous future for their children. Some smallholders also joined the LUC as well at this stage, but they were few in number (illustrated by their node just at the edge of the green surface, tca1, ).

Figure 7. Land use decision-making for private sector commercial agriculture in both villages (see also Appendix B.2. for more details on institutions)

Moving forward in time, following the regional ceasefire in 2012 (tca2, ), additional land speculators and the majority of smallholders (including the initial land users) became LUC implementers, in particular, in response to two conditions: First, the end of armed fighting enabled market access for the sale of agricultural goods. Second, land reforms/formalization measures of 2012 belonging to the state’s envisaged transition to peace offered land use certificates to land users who cultivated their plots permanently (therewith delegitimizing shifting cultivation as fallow land was not eligible for land use certificates) (see shade of institution n°10 in tca2, ). Guided by their overall agenda of improving their livelihoods and supporting their children’s education, smallholders’ interest in holding on to their land by obtaining a land use certificate and in earning income led them to contribute substantially to local conversions to and spatial expansion of commercial agriculture. Even though the land formalization law technically only applied to Village B (Village A lies in another land zone subject to other laws), smallholders in Village A also planted permanent crops, fearing they would lose their land otherwise and hoping to earn income (to improve their livelihoods and to ensure their children’s education). In this way, during the ceasefire period, smallholders in both villages became dominant actors in LUDMca in their own right, alongside the earlier agribusiness and land speculators. Further, many smallholders interacted with the agribusiness and land speculators, the latter offering them casual work opportunities.

Overall, the Myanmar state was a key enabler of this extensive LUC in its position as powerholder. With the creation of economic and institutional incentives (institutions) for commercial agriculture, the state actively fostered the LUC and became a dominant actor in LUDMca, both during the war and ceasefire. Following the first ceasefire agreement, the state increased its physical presence in the case study area via state department staff who administered land use certificates, taxes etc., such that the Myanmar state became better connected to the local land users (see ties in tca2, ). In LUDMca, we identified the state’s interests as that of fostering rural development via commercial agriculture driven by domestic and foreign investors, with priority given to large-scale industrial agricultural production (Schneider et al., Citation2020).

Actors and institutions excluded from LUDMca:

The KNU was able to improve its interactions with their ethnic people in Village A during the ceasefire. However, none of our respondents stated that the KNU had a direct influence on LUDMca. Thus, in tca2 (), the connecting tie to the smallholders remains dotted only.

Summary LUDMca:

Overall, more actors were involved in LUDMca compared to the initial situation, in particular because this LUC was highly incentivized by the Myanmar state such that several types of actors joined LUDMca, including the initial land users (smallholders). In this case, the state did not use the LUC to establish the physical presence of allies in the case study area, but rather led actors to interact and act on the state’s terms while neglecting the KNU’s terms. Thus, the KNU was neutralized in LUDMca. Through LUDMca, the state successfully increased its territorial control.Footnote12

4.2. Comparison

In all three cases of LUDM, we identified a shift of the powerholders’ engagement. While the Myanmar state increased its dominance, the KNU was gradually eliminated or neutralized in LUDM. Relatedly, the state managed to increase the physical presence of its allies and its own staff in the case study area. This leads us to assume that the Myanmar state was able to strengthen its territorial control in contrast to the KNU, who lost some of its ability to exert territorial control.

However, the three cases of LUDM differ in how the Myanmar state succeeded in removing the KNU from making decisions over land uses. In LUDMop and LUDMnr, the state explicitly and intentionally fostered or even requested the LUCs, directly mobilizing allies and useful institutions to implement the respective LUCs. In this way, LUDMop and LUDMnr represent top-down modes of decision-making. Moreover, in both cases we found evidence suggesting that the Myanmar state sought to weaken the KNU by altering the land uses: In LUDMop, the state was interested in opening up the entire region to state control and pacifying the region via oil palm concessions. In LUDMnr, the state might have applied a strategy of ‘green territoriality’ when delineating the nature reserve (K. M. Woods, Citation2019). Notably, the interests of the dominant actors in LUDMop and LUDMnr were very diverse (detailed overview in Table B.1, Appendix B). Even the interests of the state differed depending on the land use. Overall, the state and its allies did not share the same interests when joining the LUDM, but the jointly driven LUCs enabled each of the actors to achieve their respective overall agenda, facilitating collaboration.

In LUDMca, the mode of decision-making was mainly guided by incentives created by the Myanmar state, allowing for a bottom-up participation of various private sector actors. In this case, the state did not need to create or rely on allies in the actor network of LUDM to implement the LUC, but rather created economic and institutional incentives to promote actions and interactions of other actors, while ignoring the KNU’s institutions.

Taken together, all cases of LUDM have two results in common. First, in all cases, the Myanmar state managed to establish interactions with the immediate land users, compared to not having any connection in the initial situation. Second, for each case, the Myanmar state succeeded in facilitating institutions, which the new land users would adhere to and which would foster a LUC.

5. Discussion

5.1. Powerholders’ engagement in land use decision-making in civil war and the ceasefire period

One way for rival powerholders to gain control over land and thus territory is by influencing decision-making processes over land use, land use changes, land access, and land tenure (Bassett & Gautier, Citation2014; Diepart & Dupuis, Citation2014; Klem, Citation2014). In the present study, we conceive of land use decision-making (LUDM) as comprising all these collective processes, in which decisions over access to and use of land are made by various interacting actors across scales and sectors. In this way, we apply a governance-oriented understanding of LUDM. Based on our case study in southern Myanmar, the present article explored (1) how rival powerholders make use of actor networks and institutions to influence LUDM; and (2) the implications of rival powerholders’ engagement in LUDM for their territorial control. Our analysis revealed that, firstly, the ultimate powerholder – the Myanmar state – influenced LUDM by proactively making use of actor networks and institutions from a distance. Secondly, we find that the dominance of the Myanmar state in all three cases of LUDM (relative to the KNU) resulted in increased state-based territorial control in the case study area.

More specifically, in the case of large-scale oil palm monoculture, we found that the Myanmar state intentionally mobilized allies on the ground – the military company and Myanmar’s military forces – and facilitated necessary formal institutions by authorizing oil palm concessions in Tanintharyi Region from top-down. These concessions paved the way for improved state-based territorial control, because companies constructed business-related infrastructure through which the Myanmar military – and thus the Myanmar state – in turn gained better access to the contested area. Other studies from Myanmar and elsewhere present similar findings. BadeiDha Moe civil society organization (Moe, Citation2020) empirically investigated countless land grabs of the Myanmar military and its allies in the ethnic borderlands of Myanmar’s north and east during civil war. K. Woods (Citation2011) described the Myanmar state’s actions in the ceasefire period as ‘ceasefire capitalism’, according to which the Myanmar regime allocated land concessions in ceasefire zones as a deliberate post-conflict military strategy to govern land and populations in a regulated, militarized territory. Building on Woods, Thein et al. (Citation2018) point to ‘crony capitalism’ as a common Myanmar state practice during wartime and the ceasefire period, emphasizing that (ex-)military leaders and their family members frequently occupy important decision-making positions in powerful companies, benefit from special privileges, and control the economic sector in Myanmar. Further, studies from other countries show how construction of basic infrastructure, especially roads, can be part of an effective war or state-building strategy to access and fight an insurgent group and open up a previously isolated region to external influence (Klem, Citation2014). In this, we also see parallels to our Myanmar case and the processes of war- and state-making described by Castañeda et al. (Citation2017), according to which ‘war-making’ and ‘state-making’, both intertwined, are described as processes in which powerholders try to eliminate or neutralize their rivals inside a certain territory.

We observe similar processes of top-down LUDM in our nature reserve case. The Myanmar state gained local allies by entering new collaboration with oil and gas companies and creating a semi-state-owned conservation organization, and provided institutions to create a nature reserve. Both institutions and the actor network increased the Myanmar state’s territorial control from a distance and eroded that of the KNU. Scholars argue that states sometimes delineate protected forests in order to weaken insurgent groups (Bassett & Gautier, Citation2014; Peluso & Vandergeest, Citation2011). We cannot determine with certainty whether the Myanmar state issued the protected-area status with the aim of weakening the KNU. Nevertheless, the nature reserve contributed to the KNU being pushed back from territorial control along some parts of the western border. In this way, the de facto outcome of LUDM for the nature reserve demonstrated parallels to the processes of war- and state-making, whether or not it was done intentionally by the Myanmar state. Hence, while both cases of large-scale oil palm monoculture and nature reserve can be viewed as an integral part of development projects, they also bear characteristics of state-led territorialization projects (Klem, Citation2014; Lestrelin, Citation2011), in which territorial alliances (Bassett & Gautier, Citation2014; Lestrelin, Citation2011) and institutions proved decisive.

A slightly different picture emerges from our third case, where the Myanmar state fostered private sector commercial agriculture, but in a less top down fashion. Here, the Myanmar state managed to exert control over local sites from a distance without territorial alliances to single actors but by incentivizing a variety of local actors (agribusiness, land speculators, smallholders) to collaborate with the Myanmar state. This example underlines the power of institutions, which can – even from a significant distance – serve to steer LUDM and thus LUCs. The Myanmar state pushed for land formalization in the ceasefire period, thereby defining land resources as a market good. The land formalization rush that followed enabled the state to expand the reach of its statuary institutions into Myanmar’s south. This is what Sikor and Lund might call a legitimization of power and authority by regulating access to and property rights over land (Sikor & Lund, Citation2009). Meanwhile, the land formalization reforms weakened the tenure of (usually Karen) people living on land classified as ‘Reserved Forest’ (ineligible for smallholders’ land formalization) and home to KNU adherents. Such land reforms, similar to what we observed in Myanmar during its ceasefire period, have been identified beyond Myanmar as harming the welfare of ethnic minorities (such as the Karen people in Village A) while benefitting territorialisation purposes of powerholders (Lestrelin, Citation2011; Peluso & Lund, Citation2011). One could argue that for our case, the Myanmar state’s engagement in LUDM for commercial agriculture shows parallels to the processes of war- and state-making, whether intentional or not.

Taken together, in all cases the ‘winning’ powerholder (Myanmar state) used actor networks and institutions to influence and control LUDM at local level. With the increased presence of state-friendly actors and institutions, the Myanmar state also managed to significantly increase its territorial control in the case study area. At the same time, the KNU did not seem to use – or be able to use – actor networks or institutions to shape local LUDM. Possible explanations (based on Brouwer & van Wijk, Citation2013) for this might be that, firstly, the KNU leadership was perceived as being mainly interested in securing individual vested economic interests of the older generation’s leaders, rather than engaging at the frontlines. To our knowledge, the KNU leaders did not have any personal economic interests near the case study villages. Secondly, the KNU was said to be absorbed with internal political problems between the older, more hierarchical and change-resistant leadership generation and the younger, more moderate leadership generation. Thirdly, in the 1990s and 2000s, the KNU was often operating from the border with Thailand or from Thai territory, and the business- and military-friendly Thai president at the time preferred cooperating with the Myanmar military rather than supporting the KNU. Thailand only tolerated the KNU as long as it assumed a low profile, such that the KNU might have had difficulties winning allies. All these reasons might have hindered or stopped the KNU from proactively engaging in local LUDM through actor networks and institutions. In this way, based on the increased territorial presence and obvious engagement of the Myanmar state in local LUDM, in contrast to the KNU’s non-engagement and decreased territorial presence, we conclude that powerholders’ engagement in LUDM via actor networks and institutions is decisive for their territorial control.

5.2. Limitations of the study

Notwithstanding these results, some shortcomings of the study should be noted. Results of our study were clearly strongly determined by our selection of villages. We chose villages in the mixed control area. The LUCs and the LUDM preceding them would likely look different in areas controlled by a single powerholder. For example, had we chosen a village inside the nature reserve – not on the edge of the nature reserve (Village B) – the KNU would have been the major powerholder, not the Myanmar state. The core zone of the nature reserve was and is a KNU stronghold area, in which the distant institutions of the Myanmar state exist in theory, but are largely ineffective in practice for a variety of reasons (Lundsgaard-Hansen et al., Citation2018; Schneider et al., Citation2020).

In addition, as the present research topic is politically sensitive, we experienced refusal or partial refusal to participate in the survey as well as constrained access to potential respondents, especially regarding powerholders and other dominant actors in LUDM. Further, the two powerholders were difficult to reach for surveys and interviews due to lengthy bureaucratic procedures. We tried to compensate these data limitations in the surveys by acquiring in-depth case knowledge by means of expert interviews (with third parties) and by consulting the literature (see section 3.2 and Appendix A.4. and A.5.).

Finally, we acknowledge that the actor networks and institutions under study have been simplified for the sake of comprehensibility. On the one hand, some actors were grouped together. For example, the Myanmar state was and is by no means a homogenous actor. Within the Myanmar state apparatus, the overall agenda of the top leadership can differ greatly from the overall agenda of a particular state department. By ‘Myanmar state’, we have meant the core power entities within the state apparatus, usually the top leaders. On the other hand, by applying the spatio-temporal boundaries of the actor networks and institutions under study quite strictly, there was no room for reflection on other, possibly less obvious external influences on the main actors, such as involvement of top military personnel in the extraction of natural resources or the (il)legal border trade, as well as behind-closed-doors political and economic agreements with neighbouring states such as China.

5.3. Legacies of war- and state-making for Myanmar’s future

Following civil wars, it is critical to tackle questions of land tenure, management of natural resources, and land use in order to foster a durable peace (Baird & Le Billon, Citation2012; Diepart & Dupuis, Citation2014; Unruh & Williams, Citation2013) and accommodate groups who were excluded from decision-making and suffered repercussions. Myanmar’s national and local land use decision-making under the civilian government (2016 to early 2021) was still characterized by challenging, long-lasting legacies of civil war, including dispossessed smallholders who sought to reclaim ‘their’ land and refugees who returned to find their villages deemed officially illegal. Moreover, similar to other (temporary) post-war societies (Unruh & Williams, Citation2013), Myanmar under the civilian government faced a variety of other challenges such as legal pluralism and ambiguity, unclear rights, and elite control of the economy and politics. In our study, we witnessed how the Myanmar state’s formal institutions, introduced into the local context by implementers of land use changes, gradually dominated informal institutions (i.e. customary system) and local land users. To make matters worse, the current unfolding crisis in Myanmar might bring about further changes in land use decision-making (including land use, access, tenure) from the local to the national level, initiated by rival powerholders. If and when Myanmar ideally resumes a path towards peace, it will be of utmost importance that the ceasefire and post-war powerholders recognize the relevance of prompt and fair land conflict resolutions To build a durable peace in Myanmar’s centre and borderlands, current and future powerholders would need to become more determined to integrate the informal institutions of local and ethnic communities – e.g. customary systems or the KNU’s land use policy – into the centralized statuary institutions. Moreover, given the likely threat of re-escalating conflict, the state’s centrally-steered decision-making over land (use) would benefit from being more inclusive and respectful of ethnic minorities’ interests in the borderlands as well as just and inclusive legal reform, combatting legal pluralism and ambiguity, unclear rights, elite control, and unsustainable natural resource exploitation. Addressing war legacies such as large-scale land acquisitions by military-friendly actors (S. Thein et al., Citation2018), but also rebel group actors, is a challenging task for any post-war powerholders. To achieve a durable peace, however, they would need to break with particular land-related war- and state-making practices associated with other (former) powerholders’ regimes – and break with war legacies like land acquisitions. Under the civilian government of the past five years, this was hindered by the still-limited civilian control of the military and continued centralization of state authority (Stokke & Aung, Citation2020). The civilian government could not easily (or might not have desired to) revert land uses, remove allies of the military from powerful roles in land use, or change laws. It also did not manage to accommodate ethnic groups in political decision-making to a (for them) satisfactory extent.

The current anti-military statements issued by various ethnic organizations demonstrate an unequivocal demand for a united Myanmar, in which the involvement of all ethnic groups in political decision-making is called for. If the war legacies elaborated above continue to exist in the future (during a new ceasefire and a resumed peace process), and subsequent Myanmar state authorities fail to accommodate ethnic communities and organizations such as the KNU, the prospects for durable peace will be limited.

6. Conclusions

This present article sought to illuminate how, and to what end, rival powerholders in Myanmar engaged in land use decision-making, resulting in changes of land use, access to and control over land during civil war and the ceasefire period. In a case study of a conflict-ridden borderland in Myanmar, we analysed the land use decision-making that led to three main land use changes between 1990 and 2015. We analysed how two rival powerholders – the Myanmar state and the ethnic political organization KNU – made use of actor networks and institutions to influence land use decision-making. Moreover, we investigated the implications of the powerholders’ engagement in land use decision-making for their territorial control. Our analysis revealed that in all three cases, the Myanmar state strongly engaged in the decision-making, successfully increasing its control of local land use from a distance. Meanwhile, the KNU was gradually excluded from influencing land use decision-making. In two cases of territorial projects – an oil palm monoculture and a nature reserve – the Myanmar state achieved this by fostering top-down mechanisms, building actor alliances to help it control the territory, and using institutions that provided a basis for land use decision-making. The KNU was unable to influence land use decision-making in these two cases. In the third case – that of private sector commercial agriculture – the Myanmar state did not rely on alliances, but rather created strong economic and institutional incentives that encouraged private actors to pursue land uses that benefitted the state’s territorial control.

We conclude that engagement in land use decision-making can play a crucial role in influencing the outcomes of a civil war between rival powerholders, since controlling land use decision-making can imply controlling the land and territory. In our case, the Myanmar state managed to eliminate (or at least neutralize) its rival powerholder in Myanmar’s south, the KNU, from land use decision-making, thereby enabling the state to exert increasing territorial control. This can be understood as a form of war- and state-making, whether the ultimate powerholder pursues such a strategy intentionally or not. That said, it remains to be explored whether such powerholders engage in land use decision-making, and therewith push for particular land use changes, as an explicit means of war- and state-making. In the case of Myanmar, the current unfolding crisis (and likely re-outbreak of civil war) could, quite sadly, shed additional light on the explicit use of land use changes for war-making and/or state-making. Using actor networks (including an actor-agency model) as a conceptual tool in combination with spatial data could be helpful to systematically investigate such knowledge gaps.

Our findings show that land system science can provide useful insights into the role of land use decision-making and land use changes in civil wars and ceasefire periods. In particular, to (re-)build durable peace, post-war powerholders must address questions of land use, access, and tenure. To tackle such questions, post-war powerholders must first disentangle and understand the legacies of (civil) war and reforms made in the immediate aftermath of conflict. Only then can they effectively negotiate and (re-)build durable peace. For this, it is important to understand what actors were involved in or excluded from land use decision-making, their interests and alliances, and the effects of institutions on land use decision-making and land use changes during war and its aftermath. So far, this field still remains largely under-researched in land system science, despite its high relevance. We thus encourage land system scientists and others to engage in such research and related science–policy interaction, on behalf of lasting peace.

With regard to the case of Myanmar in particular, we quite sadly expect that the rival powerholders will again engage in land use decision-making and foster certain land use changes in order to increase their territorial control. If the unfolding crisis cannot be halted, we at least recommend that scientists and practitioners strive to monitor and document all upcoming major (and possibly minor) changes of land use, access, and tenure. Unfortunately, Myanmar’s civilian government (2016 to early 2021) did not have much documentation of land use, access, and tenure changes of the wartime and ceasefire period accessible (e.g. land grabs, abandonment, deforestation). As a result, land conflict resolution – a central element for durable peace – was hindered by slow and challenging attempts to gather such data first. Once peace will hopefully have returned to Myanmar, the post-crisis state authorities, ethnic organizations, civil society organizations, and other peace process supporters will ideally have immediate access to much-needed data on past, present, and future changes of land use, access, and tenure (rather than first needing to spend years gathering and documenting such data). In this way, land conflict resolutions could commence much sooner, be accomplished more rapidly, and have a much greater chance of being just, which in turn would increase the likelihood of durable peace. Further, such data could provide a valuable resource in the event that parties to war are brought before a court.

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was carried out as part of the project titled “Managing telecoupled landscapes for the sustainable provision of ecosystem services and poverty alleviation” (Project No. 152167). We thank the regional and local authorities in Tanintharyi Region for their support throughout the fieldwork. We further thank the villagers and all other interview partners for their valuable contributions. Special thanks go to the research team in Myanmar for the wonderful collaboration and great support, to Glenn Hunt and Henri Rueff for contextual feedback and discussions, to Simone Kummer for producing most figures, to Florian von Fischer for mapping the case study area, and to Anu Lannen for editing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This study both focuses on land issues and was carried out before the military coup of 1 February 2021. Hence, implications of this military coup on land use decision-making are not part of the analysis. However, in our discussion section, we reflect on possible interpretations of the results in light of the current unfolding crisis.

2. There are multiple armed Karen groups under the KNU. The composition and arrangements of these armed groups are highly complex. For more information on the KNU’s history, internal problems, and arrangements with armed Karen groups see (Brouwer & van Wijk, Citation2013; Jolliffe, Citation2016).

3. To our knowledge, the KNU never perpetrated such crimes on Bamar villages in this case study area.

4. In some parts, there is even a third actor who claims sovereignty: the New Mon State party (NMSP).

5. In recent years, the KNU has started offering land use certificates to farmers in Village A.

6. Administrative village boundaries are not precisely known by local residents in the case study area.

7. ‘Expert’ refers to individuals with extended knowledge of the core topics, for example, based on having lived in the area for a long time (e.g. elderly villagers) or having conducted relevant research or policy advising over several years (e.g. university professor).

8. ‘Rival’ refers to the respective opponent of given actors: From the perspective of the Myanmar state, the KNU is/was the rival, and vice versa.

9. In addition to the customary system, the KNU had a formal land use policy. However, smallholders in the case study village did not refer to it.

10. The KNU does not provide a description of what ‘self-determination’ means in this context. Besides political independence of a Karen state within a federation, ‘self-determination’ most likely also refers to land governance including the ‘recognition, restitution, protection, and support of the socially legitimate tenure rights of all Karen peoples and longstanding resident village communities […]’ (Jolliffe, Citation2016, p. 77).

11. Inside the nature reserve – a KNU stronghold – Karen villages continue their agricultural practices and forest use as they did before the conservation status was issued. However, given the new nature reserve regulations, the existence of the villages and their land and forest use are now formally illegal.

12. The KNU still holds an important role for Karen people in the case study area, but it is not influential regarding land uses in the case study villages (at the time of data collection in 2016–2018).

References

- Baird, I.G., & Le Billon, P. (2012). Landscapes of political memories: War legacies and land negotiations in Laos. Political Geography, 31(5), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.04.005

- Barbesgaard, M. (2019). Ocean and land control-grabbing: The political economy of landscape transformation in Northern Tanintharyi, Myanmar. Journal of Rural Studies, 69, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.014

- Bassett, T.J., & Gautier, D. (2014). Regulation by territorialization: The political ecology of conservation & development territories. Introduction. EchoGéo, 29. Article. https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.14038

- Baumann, M., & Kuemmerle, T. (2016). The impacts of warfare and armed conflict on land systems. Journal of Land Use Science, 11(6), 672–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2016.1241317

- Bennett, N., Lemelin, R.H., Koster, R., & Budke, I. (2012). A capital assets framework for appraising and building capacity for tourism development in aboriginal protected area gateway communities. Tourism Management, 33(4), 752–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.08.009

- Biermann, F., Betsill, M.M., Gupta, J., Kanie, N., Lebel, L., Liverman, D., Schroeder, H., & Siebenhüner, B. (2009). Earth system governance: people, places and the planet. science and implementation plan of the earth system governance project. IHDP: The Earth System Governance Project.

- Borgatti, S.P., Everett, M.G., & Johnson, J.C. (2013). Analyzing Social Networks. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Brenner, D., & Schulman, S. (2019). Myanmar’s top-down transition: Challenges for civil society. IDS Bulletin, 50(3), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2019.128

- Brouwer, J., & van Wijk, J. (2013). Helping hands: External support for the KNU insurgency in Burma. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 24(5), 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2013.866422

- Buchanan, J., Kramer, T., & Woods, K. (2013). Developing disparity—regional investment in Burma’s Borderlands. Transnational Institute (TNI), Burma Center Netherlands (BCN). http://www.tni.org/briefing/developing-disparity

- Castañeda, E., Schneider, C.L., & Schneider, C.L. (2017). Collective violence, contentious politics, and social change: A charles tilly reader. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315205021

- Conservation Alliance of Tanawthari. (2018). Our forest, our life: Protected areas in tanintharyi region must respect the rights of indigenous peoples (pp. 1–38). http://www.theborderconsortium.org/media/97682/CAT_Our-Forest_Our-Life_Feb2018_eng.pdf

- Diepart, J.-C., & Dupuis, D. (2014). The peasants in turmoil: Khmer Rouge, state formation and the control of land in northwest Cambodia. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(4), 445–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.919265

- Displacement Solutions. (2013). Bridging the HLP Gap—The need to effectively address housing, land and property rights during peace negotiations and in the context of refugee/IDP return (pp. 1–52).