ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes land-system dynamics changes due to energy infrastructure development and explores the environmental and social ramifications of hydraulic fracturing, through a case study in Central Appalachia. Grounded in photographic data, satellite images, and ethnographic material, this study demonstrates landscape and embodied experiences of change over time. Data show major shifts in terms of wildlife behavior, possibilities for farming and gardening, and byproducts of construction like noise, pollution, and excavation. However, what we argue is crucial to examine is the emotional toll that these changes have taken on rural residents. Interviewees chose to live in West Virginia because of deep enchantment with the surrounding natural beauty, which they feel they have lost due to energy development. While energy research has been dominated by technical disciplines and explanations, we advocate for an emotional-oriented analysis that accounts for individually lived experiences in the context of these landscape-level changes.

Introduction

Energy systems have been directly correlated to land-use change (Jepson & Caldas, Citation2017), and the United States (US) is a major focal point of these ongoing changes. The US is the world’s largest producer of natural gas (Doman & Kahan, Citation2018), producing 93.1 billion cubic feet of dry natural gas per day in 2019 alone (Kopalek & Geary, Citation2020). An increase in the price of natural gas in the mid-2000s led to the proliferation of shale gas extraction across the US, notably iin the Bakken Shale in North Dakota, the Barnett Shale in Northern Texas, and the Marcellus Shale in Appalachia (Ratner & Tiemann, Citation2015). Natural gas-fired energy production has continued to increase in all regions in the United States (York, Citation2020).

Hydraulic fracturing (‘fracking’) has developed rapidly in the past two decades, opening up unconventional sources of oil and natural gas (Sovacool, Citation2014). In the early 2000s, energy companies combined horizontal drilling with fracking to tap these reserves in many areas of the US, including the Appalachian region. In this process, machinery drills horizontally through a rock layer and injects a pressurized mix of water, sand, and chemicals that fracture the rocks and allow oil and gas to flow back up with the drilling fluids.

Although this ever-increasing natural gas production in the US is often attributed to the need for energy independence and the growth of a domestic energy supply (Sica & Huber, Citation2017), in actuality, the US is a world leader in natural gas exports (Zaretskaya, Citation2020). Natural gas is exported to 35 counties across 5 continents (Lester & Frias, Citation2021). The disconnect between narratives about energy independence and the realities of mass exportation – the transport of natural gas, via large-diameter and high-pressure pipelines across the US. – has spurred public resistance. One of the most prominent resistance movements was against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), a crude oil pipeline that put Meskwaki and Sioux tribal land and water at risk, made famous by the enduring protests from 2016 to 2017 (Deem, Citation2019). The following year, Appalachian residents mobilized against the construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) in southern West Virginia and southwest Virginia (Board, Citation2018).

The Marcellus Shale region, located in western New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, is the largest shale gas formation in the country and is believed to have a natural gas supply equivalent to 45 years of U.S. national consumption (Finkel & Law, Citation2011). Natural gas is one of the many valuable natural resources of the Appalachian region, which has historically been occupied by the extractive industries – most famously, coal. While extraction of natural resources has significantly shifted the landscape of the region, it has also affected the economic and social wellbeing of rural communities. Appalachia is the epitome of a resource curse economy: an extraction economy that while enriching some, often outside the region itself, has pushed the majority of the working-class population into poverty and dependency on a single revenue stream (cf. Luong & Weinthal, Citation2006). This legacy continues to shape the region’s current economic resource extraction model through hydraulic fracturing and pipeline development.

Critical geographers have approached energy research by developing spatial and place-based analyses that consider ‘energy landscapes’, which include the material, visible, and emplaced aspects of energy systems and how energy demands transform landscapes (Pasqualetti & Stremke, Citation2018). Energy landscapes shape space and place, as they are distributed across space and spatially constituted; as such, they are intertwined with social relations, livelihoods, place attachments, attitudes, and culture (Baka & Vaishnava, Citation2020).

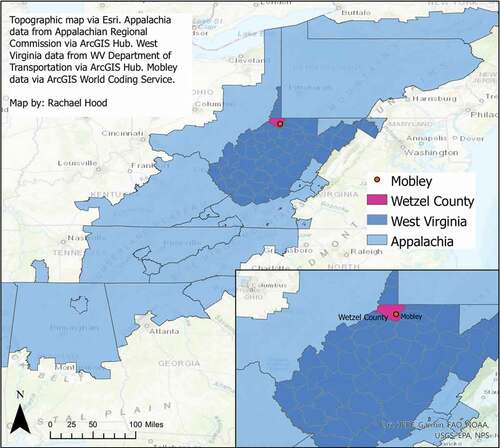

Departing from energy landscapes, the aim of this paper is to analyze land-system dynamics changes due to energy infrastructure development. Through a case study approach, this paper explores the environmental and social ramifications of hydraulic fracturing in Appalachia, a rural region being transformed into a composite landscape of industrial sites. We zoom in on the community of Mobley, West Virginia (WV), in the heart of the Marcellus Shale of Appalachia and the site of numerous crisscrossing gas and oil pipelines (Finley-Brook et al., Citation2018).

We start by outlining how energy development has shaped the landscape of Appalachia as a region within the United States. Second, we present a mixed methods approach of our case study. Third, we delve into the study results in relation to the changing energy landscape of Appalachia and how that is experienced by local residents. Finally, we discuss these results vis-à-vis energy geography and emotional geography literature, solidifying the interlinkage between these two bodies of work.

Background – U.S. energy sprawl

Energy sprawl, or new land required for energy production, is the biggest driver of land use change in the United States, according to Trainor et al. (Citation2016). This development rate is more than double the rate of urban and residential development, which has been the biggest conversion driver since the 1970s. An emergent and developing research agenda in land use science addresses the direct and indirect roles that energy geographies have on land use dynamics. Much of this research surrounds quantifiable energy sprawl, impacts, and intensity of production, using quantitative methods at a large scale, including work to measure energy potential of biomass production (Prade et al., Citation2017); map satellite data to demonstrate how bioenergy threatens food security (De Souza et al., Citation2017); and model deforestation as a result of oil exploration (Mena et al., Citation2017). Qualitative and mixed-method studies have focused on, for instance, socioeconomic, policy, and farm-level factors influencing sugarcane development and land-use change (Bergtold et al., Citation2017), or the social and political landscapes of industrial solar production (Mulvaney, Citation2017).

While unconventional gas production has a less direct contribution to US energy sprawl as compared to conventional oil and gas in terms of acreage used for well pads (because more wells can be drilled on each pad), it has a larger impact in terms of overall landscape, given that a larger area is required for roads, pipelines, and processing and storage facilities to extract the same amount of energy (Trainor et al., Citation2016). This more significant impact is in part due to the fact that, while conventional wells are produced at a slower but more constant rate, unconventional shale gas wells show incredibly high production for only a few months and maintaining production requires constant infrastructure buildout (Lave & Lutz, Citation2014). Multiple studies have shown that shale gas development is a significant driver of landscape change and has the potential to substantially alter landscapes into so-called fracked landscapes (see for e.g. Meng, Citation2014; Moran et al., Citation2015). Environmental impacts associated with fracking include but are not limited to land disturbances, forest fragmentation, groundwater contamination, water withdrawal, and air pollution (see for e.g. Buchanan et al., Citation2017). What remains under-explored, however, is how these changes have been experienced by local residents and how they have affected people’s emotional attachment to their surroundings.

Additionally, much of the landscape change research done around hydraulic fracturing and pipeline development has relied on quantitative methods, including aerial photography, remote sensing, and GIS (e.g. Donnelly et al., Citation2017). Many of these studies look specifically at forest loss and fragmentation (e.g. Jantz et al., Citation2014; Oduro Appiah, Opio, & Donnelly, Citation2020). This fragmentation threatens biodiversity and results from a variety of infrastructures, including well pads, roads, pipelines, compressor stations, staging areas, storage ponds, and rail lines (Bohannon & Blinnikov, Citation2019). However, these quantitative studies assert that unconventional oil and gas extraction can be carried out in a way that does not severely impact land, particularly if effective management and public policy decisions are put into place, for instance, by reducing forest fragmentation through the placement of new well pads near existing pipelines and pads to consolidate infrastructure (Langlois et al., Citation2017).

There is significant hydraulic fracturing activity across the Appalachian region, contributing to ongoing landscape change initiated by other industries. While the landscape of southern Appalachia has become increasingly agrarian in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries (Gragson et al., Citation2008), much of Central Appalachia has shifted in other ways: from rural woodland and pastures to barren industrial sites. This change is usually attributed to coal mining; thus, significant research has been done on landscape changes due to surface mining including shifts in water quality (Vengosh et al., Citation2013), soil composition (Miller et al., Citation2012), and biodiversity (Maigret et al., Citation2019). Environmental changes have occurred in conjunction with economic and social changes, as evidenced by proximity between coal impoundments and socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods (Greenberg, Citation2017); increased levels of risk for some landowners who allow fracking on their land (Bugden & Stedman, Citation2019); and in regard to Pennsylvania’s unconventional oil and gas extraction, the ‘externalization of costs to the environment, public health, and community integrity’ (Chalfant & Corrigan, Citation2019, p. 92). That is, economic growth in the short term has been prioritized over concerns about the long-term environmental, health, social, and financial effects of natural resource extraction that shape the lives of community members living in proximity to industrial buildout.

This paper aims to add to the body of work around energy geography and land use change by showing that energy questions are not only technical in nature but also social and political, using a case study of a rural town in North-Central Appalachia. Historically, the presence of extractive industries in the region has led to other landscape changes, such as an increase in land usage for county, state, and interstate roads. These industries have fueled energy sprawl over time, making places like Mobley, WV, the epitome of such development. The increase in interstate development demonstrates the tension between a ‘modernized landscape’ and ‘predominantly agricultural landscape’ more closely linked to ‘traditional place identities’ (Hurt, Citation2010, p. 72). Although we present a community in north-central West Virginia as a case to highlight these shifts, we contribute to larger conversations about U.S. energy sprawl by exemplifying what energy landscapes look like in practice from above through satellite pictures and from below through local residents’ interviews and pictures. This mixed methods approach, which we present in the following section, is novel in what has been described as a rift between natural scientists’ description of manageable fracking impacts and social scientists' ‘apocalyptic tone’ (Lave & Lutz, Citation2014, p. 739). While other social science studies (e.g. Perry, Citation2012; Willow et al., Citation2014) have stressed the social and economic impact of hydraulic fracturing and how it generates disempowerment, vulnerability, and displacement, we aim to interrogate energy sprawl in the rural setting of Appalachia and how it has been experienced emotionally by its residents. We do this through a mixed methods approach, as we outline in the following section.

Methodology

Guided by a participatory, feminist epistemological ethical standpoint (see Caretta, Citation2016), the data used for this article was gathered and validated through IRB-approved protocols between 2018 and 2020. In 2018 we conducted 60 semi-structured interviews with north-central West Virginia residents who had experienced hydraulic fracturing development in their communities. Given the local demographics, the lack of jobs, and the fact that West Virginia is relatively inexpensive to live in, several of those that we interviewed were retirees, either originally from the area or that had decided to move to the area to retire. In 2018 we met the late Bill Hughes, an environmental defender who dedicated more than a decade of his retirement to photo-documenting the changes that north-central West Virginia had undergone due to unconventional oil and gas development. Mr. Hughes took us to Mobley, a town whose changes he had documented meticulously, and shared with us a wealth of photographic data that he wanted us to use for scientific and pedagogical purposes. In 2020, we carried out 30 additional outdoors, socially distanced, and masked semi-structured interviews with north-central West Virginia residents to explore how their everyday lives had been affected by numerous pipelines that had been constructed to transport fracked gas. At this stage we made use of photovoice (Sullivan, Citation2017) and invited interviewees to share photos with us that they had taken in the years prior for their own purposes or by their own volition. These roughly 1500 photos were useful as an additional source of data and as an ice-breaker for interviewees to be able to share their experiences, as well as a way for us to have a visually shared understanding of how their surroundings had changed due to oil and gas development. All cumulative 90 interviews – ranging from 45 to 90 minutes – were transcribed and analyzed in the qualitative data software NVivo. For this paper, we focus on the codes of ‘land,’ ‘landscape,’ ‘erosion,’ ‘home,’ ‘rural,’ and ‘livelihood’ (for additional studies see Brock Carlson & Caretta, Citationin print; Turley & Caretta, Citation2020).

Given the participatory angle of this project, data was validated through member checking (Caretta, Citation2016), i.e. we shared transcripts and analyzed data with interviewees and additional community members through public presentations, follow-up interviews, and, in 2020, an online focus group. Member checking increased validity not only by confirming our analysis, but also by adding the understanding and interpretation of those participating in the member checking sessions, who had not been previously interviewed.

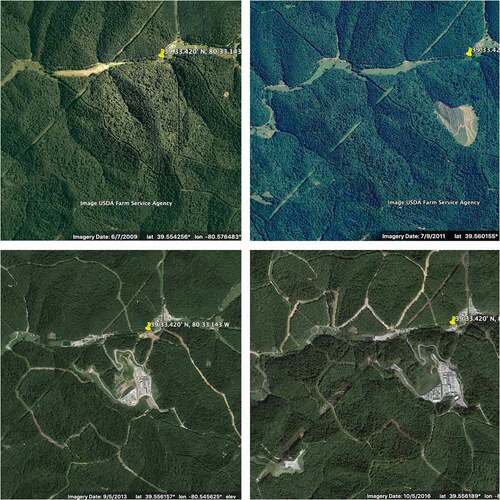

Aerial images from Google Earth were used to establish landscape change patterns at the town level. Using the GPS coordinates of Mobley as provided by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) in their permit for the MarkWest natural gas storage and processing facility (West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, Citation2017), images were captured at four intervals during which the largest transformation of the landscape is documented: 2009, 2011, 2013, and 2016. These images were analyzed qualitatively to note patterned changes in the landscape that serve to both support the claims and descriptions of interviewees and to connect the reported embodied experiences of pipeline development with landscape-level changes to Mobley.

Study site

Mobley is an unincorporated community located in Wetzel County in the northern panhandle of West Virginia. Wetzel County’s economic fate has historically been tied with oil and gas development since the 19th century. Wetzel County runs along the Ohio River to the south of the West Virginia northern panhandle (). The county has a population of about 15,270. Wetzel County has had a 24% decrease in population since 1970 (Headwaters Economics, Citation2021). Wetzel County’s economy consists of chemical industry and manufacturing plants along the Ohio River, along with some agriculture, glass production, sand and gravel processing, and lumber milling. In the past decade, Wetzel County – like neighboring Marshall, Doddridge and Harrison counties – has seen a dramatic increase in unconventional oil and gas extraction which has in turn affected personal and county income, as well as temporary population changes as pipeline workers settle briefly in the area to complete projects.

Mobley lies at the intersection of two local roads where a handful of houses are located. Mobley is representative of the county and the state because of its socioeconomic makeup. For example, the median household income for Wetzel County residents in 2019 was $43,107; for West Virginia residents altogether, the figure was $46,711 (U.S. Census, 2019). Housing and public infrastructure are rather run down, and there are limited options in terms of career-paths if residents wish to remain local; most of the local population is employed in the oil and gas industry or county government and schooling.

Mobley is an exemplary case of the hydraulic fracturing development that has characterized the Marcellus shale region of Appalachia since the end of the 2000s, given its location and the numerous wells and other gas extractive infrastructure that have been put in place. Perhaps most notably, Mobley is where the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) begins. The MVP is planned to be 303 miles, stretching from its initial point in Mobley to southern Virginia. As of the writing of this article, the pipeline is scheduled to be in service by late 2021 (Overview, 2021), despite several construction delays along the planned route.

Results- energy landscapes of Central Appalachia

Mobley, WV is one community where the effects of energy sprawl become clear. While visual data gathered over time illustrates how rural landscapes might become more industrial over a period of time, more localized accounts reveal the daily material and emotional impacts of landscape change. Residents in this rural area reported disruptions to their daily lives during periods of construction, when pipelines were laid and processing plants were built, as well as more enduring changes that have permanently altered not only their surroundings, but their experiences with those surroundings.

In the summer of 2009, the landscape surrounding the town of Mobley was characterized mostly by forests. These were the early days of hydraulic fracturing in Wetzel County. In the following years, MarkWest Energy bought part of the forest and properties in Mobley and started construction, as the 2011 satellite picture shows (). The plant became the most important feature of the town of Mobley. This infrastructure is the crux of the fate of the energy sprawl experienced by Mobley and its people, which we examine in this article.

Figure 2. This satellite imagery reflects the industrial development in Mobley over a seven-year period. The top left image was captured 7 June 2009; top right 9 July 2011; bottom left 5 September 2013; and bottom right, 5 October 2016. Images taken from Google Earth and provided by USDA Farm Service Agency

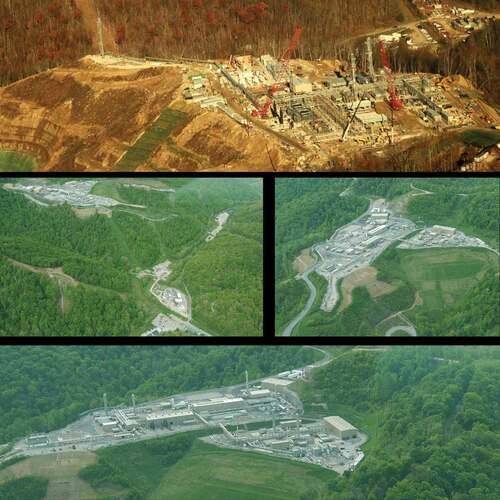

The MarkWest plant is an industrial facility that processes Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs) before transporting the NGLs through a pipeline gathering network to a fractionation complex in Washington County, Pennsylvania, where the products are separated and marketed (MarkWest Energy Partners Announces Commencement of Mobley Processing Facility in Wetzel County, West Virginia, Citation2012). Natural gas enters the facility from surrounding area wells, moves into one of the four cryogenic plants to remove excess water, and is then refrigerated to remove heavier hydrocarbons. Afterwards, the gas is compressed in a compressor engine before entering a pipeline for distribution. In 2012, the plant had a processing capacity of 200 million cubic feet per day (MMcf/d). At that time, while a large swath of trees had been cleared, many of the homes in Mobley, visible in the green sliver in the top half of the top right image (), were still standing. In 2013, just 2 years after the first image was taken in 2011, the infrastructure of the MarkWest compressor plant occupies a substantial acreage in the landscape and several homes have disappeared and been replaced by other industrial facilities. The 2013 image outlines how the landscape has been further fragmented by additional road development. In 2014, Mark West announced plans to expand the processing capacity to a total of 965 MMcf/d with the addition of a fifth cryogenic gas plant (West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, Citation2015). In the bottom right image, taken in 2016, the opening in the forest and the change in landscape are clearly delineated, as roads have been widened and more infrastructure constructed. These satellite images show how from 2009 to 2016 this rural community of a few homes has been supplanted by an industrial site for the extraction of fracked gas. In 2019, MarkWest’s processing capacity was reported to be 920 MMcf/d, as well as a de-ethanization capacity of 10,000 barrels per day (MarkWest Energy Reports Growth Locally, Citation2019).

The scale of the landscape change is visible and stark both from satellite () and aerial perspectives (). Evidence of deforestation, levelling of ridges, and removal of homes are clearly seen in the satellite images; these are but a few of the manifestations of energy sprawl that the inhabitants of the area have had to contend with. These changes occurred over a relatively short span of time, making them even more significant in the eyes of local residents. While these images illustrate changes over time from a birds’ eye view, a deeper inquiry into the moments between photos, where residents experienced construction and the realities of living with industrial infrastructure, reveals the emotional implications of these dramatic changes in the landscape.

Figure 3. Mark West Plant between 2012 and 2017. Photos by Bill Hughes (15 November 2012) and Vivian Stockman (10 May 2017), ohvec.org. Flyover courtesy SouthWings.org

From rural idyll to despair

As aforementioned, Mobley is just one of the many Appalachian communities shaped by energy development. All across northern and central West Virginia, participants in both 2018 and 2020 unanimously reported experiencing disruptions in their daily lives during drilling and construction of hydraulic fracturing sites and pipelines.

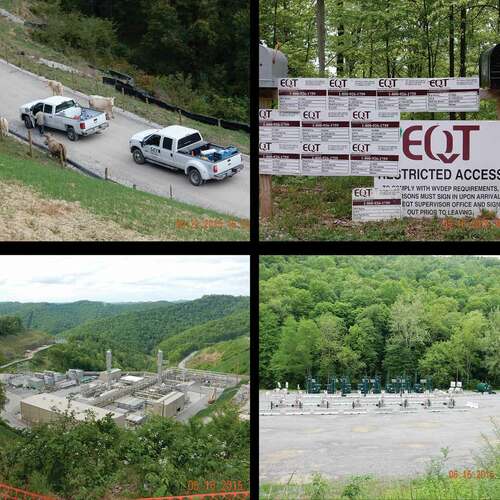

During construction periods, which would often last several months in the spring and summer, residents would have to negotiate with companies their access to their own property, including their homes, as construction equipment and crews blocked roads (). Participants reported other disruptions in their daily lives, including increased traffic, noise, and dust.

Figure 4. Construction crews, drilling permits, Mark West plants and well pads in 2015. Photos by Bill Hughes

As shows, the rural landscape underwent a substantial change, both over time and immediately, due to the development of unconventional oil and gas infrastructure. The changes are expressed through the contrast to company trucks being blocked by grazing cattle and residential mailboxes overcrowded by dozens of drilling permits (). In another contrast, the Mark West industrial site and the well pads (seen also in ) in a fabricated flat area are juxtaposed with the surrounding hilly, rural landscape.

These images give a sense of the stress experienced by local residents living near a construction site. While images cannot directly convey noise, movement, and traffic, these encounters would often be some of the first interactions residents would have with their new corporate neighbor, as this participant recalls:

The air quality, the noise … .it was totally about the nuisance of, changing your way of life is what it was about. In other words, we were used to farming, the rural living. The quiet. We didn’t have the noise and the traffic, all the lights. We were living in the rural, we went sort of into living next to a corporation … We now have a compressor station right up the road we hear running 24 hours a day. (Interview 5, 2018)

This new industrial setting, complete with corporate signs, exhaust stacks, well pads, and paved roads, all where untouched nature once stood, represented other changes for participants, such as changes in local ecosystems. Making these experiences more jarring is that these changes ran counter to the expectations of participants, who prized their rural setting. When asked why they had decided to move into remote West Virginia, participants would often comment on the idyllic nature of their land:

Coming in, we want to say it’s rural, it’s quiet, it’s peaceful, you know, people drive in, they’re going to go past all that oil and gas stuff and they’re going to say we made a wrong decision. Like G said, if there’s a station right here – so to me it’s going to affect, it probably has. Wild wonderful WV? No way. It’s toxic and terrible. (Interview 15, 2018)

The quiet, the remote location, and the nature were big draws to West Virginia for interviewees. However, these features that drew them to the countryside have been jeopardized during roughly the last 15 years of oil and gas development. With the quick appearance of industrial and extractive infrastructure, participants stressed that their sense of security, embodied in their homes and peaceful surroundings, had disappeared just as quickly. In addition to the sights and sounds of industrial development combined with dramatic changes in the landscape, participants reported that they were unsettled by the possibility of pollution, water contamination, and even explosions due to this infrastructure near their property (see also Turley & Caretta, Citation2020).

Well it [a 42 inch pipeline] really impacted mine because like I said I do a big garden. And it’s out in the middle of that field. And it would be like this normally, you’d hear the birds and the insects, it was beautiful. Well it was so bad, I mean I would sit out there and cry … (Interview 14, 2020).

This lack of security is also manifested in the way that residents’ relationships with nature and their surroundings have changed as a result of pipeline construction. According to them, the land has been stripped and sectioned in a way that does not allow for the enjoyment of nature. One interviewee who spent a lot of time hiking and gathering vegetation in the woods described the presence of ‘flagging tapes and the stakes in the ground, drill pad, drill pad, 10 drill pads laid out, tank pad laid out over here’ in addition to sites marked for seismic testing. ‘Well, that was kind of a bummer right in the middle of my mushroom patch’ (Interview 11, 2020).

Interviewees noted that the vast wilderness they once knew has been altered by development. Residents noticed that activities such as foraging for mushrooms or walking in the woods had been changed due to construction and overall noise. They commented that the wilderness, with its varied wildlife and untouched landscape, was the reason why they bought property in West Virginia. With pipeline development, that wilderness is no longer there. Interviewee 22 said that the noise from the development caused animals and birds to leave the area, making her ‘get so angry. So I stopped walking. I stopped going out. I stopped sitting on my deck. Because I would just get angry’ (Interview 22, 2020). In addition to their own frustrations with changes in expectations for their own lives, they felt angry at the loss of wildlife, which they felt belonged in those wild landscapes.

Farming activity, which has occurred for generations, has also been directly impacted by pipeline and oil and gas development. A majority of interviewees noted how wells and pipelines directly reduced their farming acreage, while others mentioned farmhouses and other pieces of land being excavated and/or removed for oil and gas development. One interviewee described her reaction to the pipeline being laid and disrupting farmland that had been farmed by one family for over 80 years: ‘All these wells in one location. That is what I believed until my family lost 72 acres of their farm. They have over 1000 acres out here.’ (Interview 13, 2020). In some cases, companies purchased land and demolished large farmhouses that had been family homes for generations in order to bury pipelines. The emotions these changes brought about are expressed by Interviewee 6: ‘It was despair, because what we had farmed, and what other people we knew had farmed this land, all this year, had put their heart and soul into it, and our blood, sweat, and tears are into it.’ (Interview 6, 2020).

Despite the fact that residents receive compensation for their property from energy companies, our interviewees suggested several things. First, the compensation was not as much as one might think, given the value of the land and the financial importance of the energy infrastructure for the growth of the company installing it. Second, their home had significant emotional and community value, as in one interviewee’s experience, the house had been built by her husband who has since passed: ‘He set her up for life, then they took that’ (Interview 23, 2018). To interviewees, the home’s worth could not only be calculated in financial terms as it is synonymous with deep emotional connections to land and one another. However, because of these major environmental and landscape changes, many participants expressed a desire, however serious or lasting, to sell their land and go elsewhere.

Living through the construction process and the long-term establishment of energy infrastructure is described by many as deeply painful, as the retirement they had envisioned in the calm of rural West Virginia is simply not possible for them anymore. For some, it has been so painful that they made the difficult decision to sell their land and leave the area, despite the emotional attachment to their homes. For others, including many residents that we spoke with, they actively struggled with the idea of leaving the area, as some of their friends and neighbors had, because they simply could not afford to leave, or they were too attached to their homes – even if it did not feel like the same place where they settled anymore due to the changes in landscape and overall quality of life.

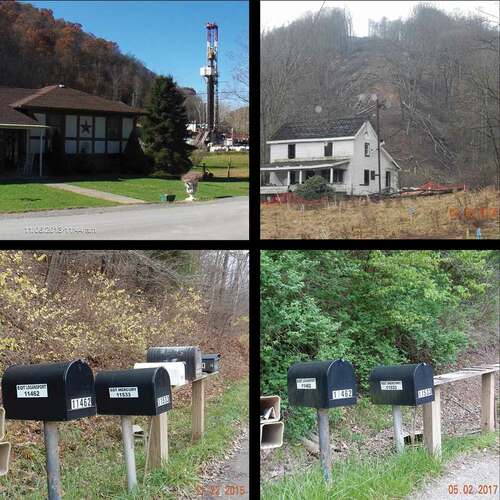

The phenomenon of residents leaving or selling their homes is most salient in the case study of Mobley. Not only did many of the Mobley residents leave their homes after being bought out by fracking companies, but the community as a whole was disrupted, both in terms of daily life and in social connection. The collection of homes that constituted Mobley as a residential community has been replaced by oil and gas infrastructure and company signs. The decrease in the number of mailboxes along the road in Mobley () in just 2 years’ time signals how quickly and how closely residents saw their surroundings change. The images in reflect this disruption, showing how homes became juxtaposed with bleak industrial artifacts. The removal of mailboxes reflects the decrease in population of the area.

Figure 5. The top left image (11.06.13) shows a Mobley resident’s home with fracking infrastructure located only a few hundred feet away. The top right image shows an abandoned home that was purchased by Mark West, with a pipeline on the hillside behind it, as indicated by the loss of trees on the right-of-way. The bottom two images demonstrate the loss of residents through time. In the bottom-left image (11.22.15), the mailboxes on the left are EQT mailboxes, while the mailboxes on the right are for residential homes. In the bottom-right image (05.02.17), a year and a half later, only the EQT mailboxes remain

Ultimately, the effects of the extraction industry in rural communities like Mobley are significant. In addition to the clear and often dramatic changes in landscape and scenery, the very uses of the land have changed, and with that landowners´ experiences and emotional attachments to the land as well.

Concluding discussion – moving towards emotional energy geographies

Through a case study in Central Appalachia, this paper analyzes land-system dynamics changes due to energy infrastructure development. Notably, departing from earlier literature with singular methodological entry points, we use photographic data and satellite images in conjunction with ethnographic material to show the landscape and embodied experiences of residents of these energy geographies.

Energized by the shift from conventional natural gas production with vertical drilling to unconventional gas extraction utilizing horizontal drilling, energy sprawl is unfolding in West Virginia, largely from natural gas. One of the main features of such energy sprawl is increased land use for infrastructures that support large-scale gas production such as pipelines and natural gas processing facilities. The visual evidence of landscape change, noted in satellite images and photographs taken of Mobley over the course of several years, is clear, and directs us to consider the emotional implications of these changes. Since conversations about energy development are dominated by technical understandings of these processes, embodied experiences have been left out of these conversations. But energy development, through the construction of processing plants, pipelines, and well pads, changes rural landscapes and, by extension, the emotions of rural communities towards surrounding landscapes. Mobley presents a clear case of how seemingly routine development of industrial infrastructure can have significant and lasting impacts on rural communities including but not limited to physical changes in the landscape. As several interviewees recounted, these changes are manifested in major shifts in terms of wildlife behavior, possibilities for farming and gardening, and byproducts of construction like noise, pollution, and excavation. Of course, these changes on their own are notable; however, the emotional toll that these changes have taken on rural residents is perhaps even more important to examine, we argue. Many interviewees chose their place of residence because of deep enchantment with the surrounding natural beauty, which they feel they cannot access anymore. The experiences that participants reported point to daily disruptions that feed feelings of stress, sadness, and even grief, as well as longer-lasting changes to their land and their feelings towards the land. Some experienced the gas-related development as unbearable, and they felt forced to sell or leave their property.

Earlier literature on place attachment highlights how landscape change affects people´s sense of belonging to a certain area (Manzo & Devine-Wright, Citation2014). Likewise, our results show that landscape change does affect one’s sense of home, making visible and personal the often-depoliticized technical discussions around energy infrastructure. The look of a landscape shapes the feelings that residents have towards that landscape, and, therefore, their homes within that landscape. We analyze these changes through the lens of energy and emotional geography as we problematize how energy development in the supposed service of the public good can disrupt peoples’ safety, security, comfort, and well-being. Conversations with research participants around the home reveal that many residents experience despair due to natural gas developments.

In this paper, we contribute to the literature on energy landscapes, focusing particularly on how the changes in landscape due to energy development in the form of hydraulic fracturing and pipeline infrastructure have been experienced emotionally by local residents. These data show that energy sprawl-driven landscape changes are indicative of more complicated relationships between industries and communities, as well as a more nuanced understanding of how landscape change directly changes the lives of residents in rural areas. The emotional attachments that participants have to their land and home emerge strongly from interviews and pictures participants took documenting the change in the landscape around their property. Whether they were living in a cabin in the woods or farming the land as their families had done for generations, participants felt connected to that land, and when it was irrevocably changed, their feelings towards the land changed too. By connecting evidence of major landscape changes, such as the proliferation of industrial sites alongside the decrease in rural and undeveloped areas, with more human-focused accounts of changes from photos and interviews, we demonstrate how physical landscape and emotional experience are intertwined.

From a land use science perspective, we advocate for bringing together energy geography and emotional geography (see also Rohse et al., Citation2020). We argue that, as emerging from the data presented, the emotional spillovers of energy development cannot be obfuscated by the need for energy independence or the transition towards cleaner energy sources (see e.g. Mulvaney, Citation2017). This dynamic is especially notable in Central Appalachia, where extractive industries have long been present and have impacted the ‘renewability’ of social and environmental communities in the region (Schumann, Citation2016, p. 19). Technical and statistical research into energy development’s environmental impact is overrepresented in scientific knowledge production, and this research often promotes the vision of increased development and growth towards the aim of energy independence (Sica & Huber, Citation2017; see also Brock Carlson & Caretta, Citationin print). However, energy systems affect more than just land use; energy system development and change also raises important questions about power and social relations. Emotional and embodied approaches can improve our understanding of how energy systems interact with lived experiences, an essential but overlooked aspect of energy production.

We advocate for an emotional-oriented analysis that accounts for individual lived experiences in the context of these landscape-level changes, which can contribute to environmental and energy justice analyses (for more see Brock Carlson & Caretta, Citationin print). Often, scholarship within the field of energy justice centers around access to energy services or lack thereof (also known as energy poverty) (e.g. Bouzarovski, Citation2014; Bouzarovski & Thomson, Citation2018; Harrison & Popke, Citation2011). Energy justice research often calls for an understanding of welfare support and energy policy that focuses not just on energy transition and production infrastructure, but also the inequitable energy consumption landscape (Harrison & Popke, Citation2011).

In this paper, however, we emphasize another lens of energy justice by focusing on the ways in which a community is sacrificed for the alleged goals of energy security and independence of a region or nation at-large. Proponents claim that this is necessary for reduced energy costs, but energy justice scholars demonstrate that energy remains unaffordable for impoverished households, regardless of the source (Harrison & Popke, Citation2011). The supply chain, landscape, and political economy of energy production not only leave impoverished homes still without security but also exploit fence line communities for corporate profit (Healy et al., Citation2019). Study participants reported experiencing a sense of despair around what has become of their surroundings, while also feeling insecure around potentially explosive gas pipeline infrastructure. Meanwhile, gas companies often paint a picture of benign community benefits for their extractive enterprises. However, our findings in Mobley mirror other studies which have found less consensus around energy production than is reflected in official narratives praising necessary and progressive energy transitions, whether toward natural gas or renewable energy infrastructure like wind and solar (e.g. Yenneti et al., Citation2016). Just as with the energy development debates, climate transition debates are often reduced in terms of technology and economics alone (Bosch & Schmidt, Citation2020), but works like ours demonstrate that the lived experiences of frontline communities must be heard and incorporated in any substantial plan to address climate injustices. Research that directly engages with lived experiences that are often dismissed or not captured as part of official discourses around energy development and landscape change offers a path into a more nuanced understanding of both existing fossil fuel energy landscapes, and those landscapes undergoing changes due to energy transitions.

Acknowledgments

We wish to dedicate this work to the memory of unstoppable and inspiring activist Bill Hughes. Without his, Marianne´s, and all other participants´ time and patience, we would have not been able to conduct this research. Funding for this research was provided by West Virginia University Energy Institute, the Heinz Foundation, and the West Virginia University Humanities Center. Thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their useful insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baka, J., & Vaishnava, S. (2020). The evolving borderland of energy geographies. Geography Compass, 14(7), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12493

- Bergtold, J.S., Caldas, M.M., Sant’Anna, A.C., Granco, G., & Rickenbrode, V. (2017). Indirect land use change from ethanol production: The case of sugarcane expansion at the farm level on the Brazilian Cerrado. Journal of Land Use Science, 12(6), 442–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2017.1354937

- Board, G. (2018, March 28). Pipeline protesters blockade path to pipeline. WV Public Broadcasting. Retrieved from https://www.wvpublic.org/news/2018-03-28/pipeline-protesters-blockade-path-to-pipeline.

- Bohannon, R., & Blinnikov, M. (2019). Habitat fragmentation and breeding bird populations in western North Dakota after the introduction of hydraulic fracturing. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 109(5), 1471–1492. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2019.1570836

- Bosch, S., & Schmidt, M. (2020). Wonderland of technology? how energy landscapes reveal inequalities and injustices of the German Energiewende. Energy Research & Social Science, 70, 101733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101733

- Bouzarovski, S. (2014). Energy poverty in the European Union: landscapes of vulnerability. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy and Environment, 3(3), 276–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/wene.89

- Bouzarovski, S., & Thomson, H. (2018). Energy vulnerability in the grain of the city: Toward neighborhood typologies of material deprivation. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(3), 695–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1373624

- Brock Carlson, E., & Caretta, M.A. (in print). Legitimizing situated knowledge in rural communities through storytelling around gas pipelines and environmental risk. Technical Communication.

- Buchanan, B.P., Auerbach, D.A., McManamay, R.A., Taylor, J.M., Flecker, A.S., Archibald, J.A., & Walter, M.T. (2017). Environmental flows in the context of unconventional natural gas development in the Marcellus Shale. Ecological Applications, 27(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1425

- Bugden, D., & Stedman, R. (2019). Rural landowners, energy leasing, and patterns of risk and inequality in the shale gas industry. Rural Sociology, 84(3), 459–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12236

- Caretta, M.A. (2016). Member checking: A feminist participatory analysis of the use of preliminary results pamphlets in cross-cultural, cross-language research. Qualitative Research, 16(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115606495

- Chalfant, B.A., & Corrigan, C.C. (2019). Governing unconventional oil and gas extraction: the case of Pennsylvania. Review of Policy Research, 36(1), 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12319

- de Souza, C.H.W.D., Cervi, W.R., Brown, J.C., Rocha, J.V., & Lamparelli, R.A.C. (2017). Mapping and evaluating sugarcane expansion in Brazil’s savanna using MODIS and intensity analysis: A case-study from the state of Tocantins. Journal of Land Use Science, 12(6), 457–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2017.1404647

- Deem, A. (2019). Mediated intersections of environmental and decolonial politics in the No Dakota access pipeline movement. Theory, Culture and Society, 36(5), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276418807002

- Doman, L., & Kahan, A. (2018, May 21). United States remains the world’s top producer of petroleum and natural gas hydrocarbons. US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=36292.

- Donnelly, S., Cobbinah Wilson, I., & Oduro Appiah, J. (2017). Comparing land change from shale gas infrastructure development in neighboring Utica and Marcellus regions, 2006–2015. Journal of Land Use Science,12(5), 338–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2017.1331274

- Finkel, M.L., & Law, A. (2011). The rush to drill for natural gas: A public health cautionary tale. American Journal of Public Health, 101(5), 784–785. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300089.

- Finley-Brook, M., Williams, T.L., Caron-Sheppard, J.A., & Jaromin, M.K. (2018). Critical energy justice in US natural gas infrastructuring. Energy Research & Social Science, 41, 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.019

- Gragson, T.L., Bolstad, P.V., & Welch-Devine, M. (2008). Agricultural transformation of southern Appalachia. In C. Redman & D.R. Foster (Eds.), Agrarian landscapes in transition: Comparisons of long-term ecological and cultural change (pp. 89–121). Oxford University Press.

- Greenberg, P. (2017). Disproportionality and resource-based environmental inequality: an analysis of neighborhood proximity to coal impoundments in Appalachia: resource-based environmental inequality. Rural Sociology, 82(1), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12119

- Harrison, C., & Popke, J. (2011). “Because you got to have heat”: The networked assemblage of energy poverty in eastern North Carolina. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101(4), 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2011.569659

- Headwaters Economics. (2021). A profile of socioeconomic trends Wetzel County. Retrieved from https://headwaterseconomics.org/apps/economic-profile-system/54103.

- Healy, N., Stephens, J.C., & Malin, S.A. (2019). Embodied energy injustices: unveiling and politicizing the transboundary harms of fossil fuel extractivism and fossil fuel supply chains. Energy Research & Social Science, 48(October2018), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.09.016

- Hurt, D.A. (2010). Highway expansion and landscape change in East Tennessee. Focus on Geography, 53(2), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8535.2010.00010.x

- Jantz, C.A., Kubach, H.K., Ward, J.R., Wiley, S., & Heston, D. (2014). Assessing land use changes due to natural gas drilling operations in the Marcellus Shale in Bradford County, PA. Geographical Bulletin, 55(1), 18–35. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=95523963&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Jepson, W., & Caldas, M. (2017). Changing energy systems and land-use change. Journal of Land Use Science, 12(6), 405–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2017.1408889

- Kopalek, M. & Geary, E. (2020, October 5). U.S. natural gas production, consumption, and exports set new recordsin 2019. U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=45377

- Langlois, L.A., Drohan, P.J., & Brittingham, M.C. (2017). Linear infrastructure drives habitat conversion and forest fragmentation associated with Marcellus shale gas development in a forested landscape. Journal of Environmental Management, 197, 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.03.045

- Lave, R., & Lutz, B. (2014). Hydraulic fracturing: A critical physical geography review. Geography Compass, 8(10), 739–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12162

- Lester, P., & Frias, G. (2021, January 11). Interactive map: U.S. liquefied natural gas exports breaking records. US Department of Energy. Retrieved from https:https://www.energy.gov/articles/interactive-map-us-liquefied-natural-gas-exports-breaking-records

- Luong, P.J., & Weinthal, E. (2006). Rethinking the resource curse: ownership structure, institutional capacity, and domestic constraints. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci, 9(1), 241–263. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.062404.170436

- Maigret, T.A., Cox, J.J., & Yang, J. (2019). Persistent geophysical effects of mining threaten ridgetop biota of Appalachian forests. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 17(2), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1992

- Manzo, L.C., & Devine-Wright, P. (2014). Place attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications. Taylor & Francis.

- MarkWest Energy Partners Announces Commencement of Mobley Processing Facility in Wetzel County, West Virginia. (2012, December 13). Business wire. Retrieved from https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20121213005378/en/MarkWest-Energy-Partners-Announces-Commencement-of-Mobley-Processing-Facility-in-Wetzel-County-West-Virginia.

- MarkWest Energy Reports Growth Locally. (2019, February 25). The intelligencer. Retrieved from https://www.theintelligencer.net/x-old-sections/cultivating-success-in-energy/2019/02/markwest-energy-reports-growth-locally/.

- Mena, C.F., Laso, F., Martinez, P., & Sampedro, C. (2017). Modeling road building, deforestation and carbon emissions due deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon: The potential impact of oil frontier growth. Journal of Land Use Science, 12(6), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2017.1404648

- Meng, Q. (2014). Modeling and prediction of natural gas fracking pad landscapes in the Marcellus Shale region, USA. Landscape and Urban Planning, 121, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.09.005

- Miller, J., Barton, C., Agouridis, C., Fogel, A., Dowdy, T., & Angel, P. (2012). Evaluating soil genesis and reforestation success on a surface coal mine in Appalachia. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 76(3), 950–960. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2010.0400

- Moran, M.D., Cox, A.B., Wells, R.L., Benichou, C.C., & McClung, M.R. (2015). Habitat loss and modification due to gas development in the Fayetteville Shale. Environmental Management, 55(6), 1276–1284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0440-6

- Mulvaney, D. (2017). Identifying the roots of green civil war over utility-scale solar energy projects on public lands across the American Southwest. Journal of Land Use Science, 12(6), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2017.1379566

- Oduro Appiah, J., Opio, C., & Donnelly, S. (2020). Quantifying, comparing, and contrasting forest change pattern from shale gas infrastructure development in the British Columbia’s shale gas plays. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 27(2), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2019.1649313

- Pasqualetti, M., & Stremke, S. (2018). Energy landscapes in a crowded world: A first typology of origins and expressions. Energy Research and Social Science, 36, 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.030

- Perry, S.L. (2012). Development, land use, and collective trauma: the Marcellus Shale gas boom in Rural Pennsylvania. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment, 34(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2153-9561.2012.01066.x

- Prade, T., Björnsson, L., Lantz, M., & Ahlgren, S. (2017). Can domestic production of iLUC-free feedstock from arable land supply Sweden’s future demand for biofuels?. Journal of Land Use Science, 12(6), 407–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2017.1398280

- Ratner, M., & Tiemann, M. (2015). An overview of unconventional oil and natural gas: resources and federal actions. Congressional Research Service: R43148. Retrieved from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43148.pdf

- Rohse, M., Day, R., & Llewellyn, D. (2020). Towards an emotional energy geography: attending to emotions and affects in a former coal mining community in South Wales, UK. Geoforum, 110, 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.006

- Schumann, W. (2016). Sustainable development in Appalachia: two views. Journal of Appalachian Studies, 22(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.5406/jappastud.22.1.0019

- Sica, C.E., & Huber, M. (2017). “We can’t be dependent on anybody”: the rhetoric of “Energy independence” and the legitimation of fracking in Pennsylvania. Extractive Industries and Society, 4(2), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2017.02.003

- Sovacool, B.K. (2014). Cornucopia or curse? reviewing the costs and benefits of shale gas hydraulic fracturing (fracking). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 37, 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.04.068

- Sullivan, P. (2017). Participating with pictures: promises and challenges of using images as a technique in technical communication research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 47(1), 86–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616641930

- Trainor, A.M., McDonald, R.I., Fargione, J., & Baldwin, R.F. (2016). Energy sprawl is the largest driver of land use change in United States. PloS One, 11(9), e0162269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162269

- Turley, B., & Caretta, M.A. (2020). Household water security: an analysis of water affect in the context of hydraulic fracturing in West Virginia, Appalachia. Water, 12(1), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010147

- U.S. Census. (2019, July 1). Wetzel County, West Virginia, West Virginia, demographic table. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/wetzelcountywestvirginia,WV,US/PST045219

- Vengosh, A., Lindberg, T.T., Merola, B.R., Ruhl, L., Warner, N.R., White, A., Dwyer, G.S., & Di Giulio, R.T. (2013). Isotopic imprints of mountaintop mining contaminants. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(17), 10041–10048. https://doi.org/10.1021/es4012959

- West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection. (2015). Engineering evaluation/fact sheet: mobley gas plant. Retrieved from https://dep.wv.gov/daq/Documents/January%202016%20Permits%20and%20Evaluations/103-00042_EVAL_13-2878D.pdf

- West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection. (2017). Engineering evaluation/fact sheet: mobley gas plant. Retrieved from http://dep.wv.gov/daq/Documents/June%202017%20Draft%20Permits%20and%20IPR/103-00042_IPR_13-2878E.pdf

- Willow, A.J., Zak, R., Vilaplana, D., & Sheeley, D. (2014). The contested landscape of unconventional energy development: A report from ohio’s shale gas country. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 4(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-013-0159-3

- Yenneti, K., Day, R., & Golubchikov, O. (2016). Spatial justice and the land politics of renewables: dispossessing vulnerable communities through solar energy mega-projects. Geoforum, 76, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.09.004

- York, S. (2020). Natural gas-fired generation has increased in most U.S. regions since 2015. U.S Enery Information Administration. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=46143.

- Zaretskaya, V. (2020). U.S. liquefied natural gas exports set a record in November. US EIA. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=46296.