ABSTRACT

Dichotomies emerge among early-career land scientists when balancing their career goals with family obligations, exhibiting differences in gender and regions. Through on-line surveys, we examined the interconnection between family obligations and doctoral performance through a gender lens on an international sample of doctoral students. The analysis of the findings indicated that more women than men in the doctoral program were responsible for family obligations, with mothers experiencing a prolonged duration of completing their doctorates and a lower publication rate. Majority of the respondents, primarily women from the Global North, decided not to be parents due to anticipated challenges with maintaining a work-life balance exacerbated by traditional gender roles, limited financial support for childcare, and high demands of academia. The constraints of early-career land scientists, particularly mothers from the Global South living apart from relatives, need to be addressed for institutes to strengthen international gender equality in land science.

Introduction

The under-representation of women in education and academia is a societal issue that has persisted across centuries, underpinning early feminist movements for gender equality.Footnote2 In one of the earliest books of feminist philosophy in the 18th century, Wollstonecraft (Citation1792) strongly argued for the need for women to be educated, which would allow them ample opportunities to contribute to society, aside from domestic labor. Currently, there is a much higher proportion of educated women, with many achieving doctorates in academic institutions that were traditionally exclusive to men. Globally, the number of women, who entered tertiary education, attaining bachelor, master, and doctorate degrees, has tripled between 1995 and 2018 (UNESCO, Citation2020). This number is higher than male enrolment over the same period. However, women still represent only a small proportion of doctorate holders and candidates compared to the proportion of women with bachelor’s degrees in all world regions except for Central Asia (UIS and UNESCO, Citation2019).

Particularly in the traditionally male-dominated fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), there is a stark under-representation of female doctoral students (UNESCO, Citation2020; UNESCO & UNESCO IESALC, Citation2021). Literature on gender equality in academia has highlighted the sharp decline of the number of female scientists in soil and land science after they complete their doctorate (Dawson et al., Citation2021; Maas et al., Citation2021; Vaughan et al.,Citation2019). This trend is supported by statistics on gender equality in Germany and the U.S., where women’s representation in post-graduate research positions in STEM fields, particularly associate and full-time professorships, is less than 25% (BMFSFJ,Citation2016; Gender Equality: Statistics, Citation2021; Vaughan et al., Citation2019). These numbers demonstrate that academia is no exception to the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions.

Authorship in publications, one of the conventional indicators of academic performance, also continue to be dominated by male researchers. A study conducted by the UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (UNESCO & UNESCO IESALC, Citation2021) observed that globally, between 1999 and 2003, 71% of the authors of academic publications were men and only 31% were women. Moreover, during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, the submission of academic papers for publication increased, but the growth was significantly slower for female researchers (Shamseer etal., Citation2021; Squazzoni etal., Citation2021; Viglione, Citation2020; Vincent-Lamarre, et al., Citation2020) nutshell, women can be seen as the gender, which faces most challenges in embarking on academic pathways.

While the differences in challenges between men and women in academia is apparent and well documented in the literature, the differences in academic performance and experiences between women academics from the Global NorthFootnote3 and Global SouthFootnote4 is a less-discussed, yet emerging issue being highlighted in recent publications. Studies unveil acute gender gaps in academic environments in the Global South (Archer et al., Citation2015); Dawson et al.,Citation2021) along with ethnic disparities of authorship in publications on land science (Kamau et al., Citation2021) and climate science (Blicharska et al., Citation2017). Kamau et al. (Citation2021) found that the representation of ‘Black’ women in any authorship position is lower than the share of ‘white’ and ‘Asian’ female authors, which aligns with the findings in Blicharska et al. (Citation2017) showing how less than 10% of author affiliations in publications on climate change were from the Global South. A study in sub-Saharan Africa found that only 28% of students enrolled in doctorate programs in science from 2015/2016 to 2018/2019 were women (Fisher et al., Citation2020). On the contrary, a study in the U.S. identified an increase of women pursuing doctorates in land and soil science between 1960 and 2020, reaching 38% to 53% between 2013 and 2018 (Vaughan et al., Citation2019)). Additional findings from Riegle-Crumb et al. (Citation2019) showed a 19% higher dropout rate in STEM fields among black women compared to white women, which could have contributed to the under-representation of female early-career academics from the Global South.

Fisher et al. (Citation2020) also found that the majority of women in the doctoral programs in sub-Saharan Africa focused their research on agricultural issues, a key topic under the auspices of land science, an interdisciplinary field rooted in human geography, social sciences, economics, and forestry. Land science is hinged on the idea that land use itself is complex and requires the integration of diverse, transdisciplinary, and intersectional perspectives to unravel the dynamics of human and land-based ecological systems. Thus, according to the study by Fisher et al. (Citation2020) among others (Cook, et al., Citation2019; SOFA Team, and Doss, Citation2011; Villamor, et al., Citation2013) land science is a highly relevant field for women from countries in the Global South, who play a significant role in managing land-based systems, such as agriculture, and responding to external socio-environmental threats on these systems. Women are also often the victims of pervasive gender discrimination in countries where traditional, patriarchal gender norms persist, resulting in constraints on their use of and access to land (Fonjong et al., Citation2013). Female researchers from the Global South are, therefore, crucial contributors to land science due to their close attachment to regions experiencing an increase in multifaceted land pressures.

These statistics on gender inequality and ethnic disparities in academic institutions focused on STEM can be explained by multiple factors, such as, gender bias by elite male faculty hiring fewer female graduate students, gender discrimination against women scientists culminating in less academic resources accessible to female faculty, and a lack of institutional support for women pursuing graduate positions in STEM (Monroe et al., Citation2008; Sheltzer & Smith, Citation2014). However, an under-researched rationale for the gender imbalance in academia, particularly at the doctorate level, is the pressure of traditional gender roles (Ledin et al., Citation2007). Childcare and related domestic responsibilities are particularly highlighted in literature as a main challenge for academics with children or plans to start a family (UN Women, Citation2018). As a result, women academics many times have to decide between family and professional priorities. While some avoid bearing children during their scientific careers, others leave academia after their first child. For women, balancing family and work obligations usually comes with a cost to their academic performance and a prolonged duration of their research projects. (Cech & Blair-Loy, Citation2019; Fisher et al., Citation2020; Perry et al., Citation2018; Sallee et al., Citation2016).

With most of the literature primarily focusing their analyses on the relationship between gender differences at the faculty level and academic performance using western case studies in North America and Europe (Ashencaen Crabtree & Shiel, Citation2019; Van Den Brink & Benschop, Citation2012; Winchester & Browning, Citation2015), knowledge gaps prevail on the challenges of mothers with origins in the Global South pursuing scientific careers. Apart from Fisher et al. (Citation2020), few studies explored the gender imbalance in STEM-based doctoral programs where majority of the candidates are from the Global South. Specifically, there are a paucity of studies that, firstly, compare the family obligations of doctoral students from the Global North and Global South, and, secondly, examine international gender equality in institutions focusing on land science, a relevant field for women from developing countries.

We address this prevalent literature gap by investigating the challenges of the dichotomy between having a family and pursuing an academic career among a sample of female and male doctoral students, from both developed and developing countries, in the Bonn International Graduate School for Development Research (BIGS-DR) at the Center for Development Research (ZEF). In order to determine trends in the international gender equality of parents pursuing careers in land science, we assess the experiences of doctoral students, particularly parents in different stages, based on their gender and regional origins. Firstly, we expect that the association between family obligations with academic performance varies across gender, being particularly challenging for mothers, rooted in the persistence of traditional gender roles. Secondly, we hypothesize that the pursuit of academic careers among women are dependent on cultural, institutional, and economic contexts and that there are differences in family obligations between female academics from developed and developing regions, contributing to the exacerbation of challenges in work-life balance among female doctoral students from the Global South.

By examining the gender and regional dichotomies among early-career land scientists with children and traditional gender roles as an underlying issue assigning responsibilities of parenting and household duties to women, we highlight the disparity between men and women when it comes to taking care of family and the impacts it has on their academic performance. Alleviating the pressures on parents, particularly mothers from the Global South, during their doctorate is crucial in the worldwide efforts to erase barriers in women achieving their aspirations of becoming scientists. Their research contributions in the field of land science are key for identifying the inter-linked, intersectional problems of land-based systems and developing science-based, fair solutions, which will help countries to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG5 (gender equality) and SDG15 (life on land) (Gao & Bryan, Citation2017).

Materials and methods

Considering that gender barriers are context-dependent, we adopted a case study approach based on data from current students and alumni of the Bonn International Graduate School for Development Research (BIGS-DR), hosted by the Center for Development Research (ZEF) at the University of Bonn in Germany. There are roughly 400 alumni and 125 current students from 100 countries in this renowned international and transdisciplinary doctoral program, running since 1999 (ZEF, Citation2018). Over 40% of the student and alumni body are women, and 82% of the current doctoral students as of 2017 are from non-OECD and transition countries (ZEF, Citation2017, Citation2018). The average duration of the program is three and a half years, with around 20–30 students entering the program each year. The current research themes at ZEF focus on 10 topics related to land science, including science policy, biodiversity, governance and conflict, land use and agriculture linked to climate change, gender, mobility and migration, markets and services, water resources, health, and nutrition (ZEF, Citation2021). The extensive research related to disciplines of land science and the significant proportion of students from the Global South make the doctoral program at ZEF a suitable case study for this research topic.

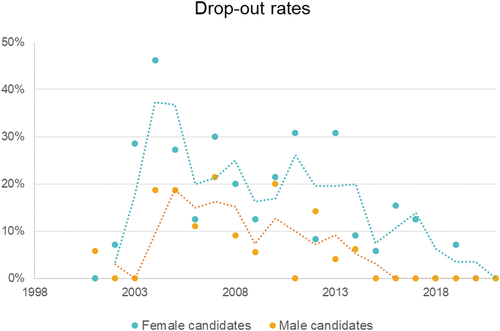

Since 1998, 10% of graduate students (n = 62) failed to complete the doctoral program. From these, two-thirds are female students while one-third are male students, which goes against the total proportion of male/female students in the program (45%/55%). The dropout rates have been decreasing for both genders since 2013, but the reasons for the higher number of female students leaving the program remains unknown () (BIGS-DR, Citation2021). Besides, the limited data on the marital and/or parenting status of doctoral students represent constraints for the unveiling potential gender-based challenges, such as differences in the academic performance. Thus, our research findings intend to inform international doctoral programs on the key concerns among doctoral students related to work-life balance.

Figure 1. Share of drop-out rates among female candidates and among male candidates from the doctoral program at ZEF, according to their batches, from 1998 to 2021.Footnote8

To do that, we collected quantitative and qualitative data from online surveys to assess the differences between gender, and trends over time regarding family obligations. We designed the survey through Google Forms with 11 closed-ended questions and the option to leave open-ended comments, in order to reduce the complexity and duration of the survey, and increase the response rate (see Appendix 1). Besides the two genders of men and women, the survey encompassed non-binary identities. The research problem was introduced via a brief explanation about the scope of the study, general guidelines of the survey and the role of their participation in this process, for example, to provide personal views on family obligations during the doctorates of the participants. The objective here was not to reveal the gender aspect of the analysis in order to avoid biased answers. As part of the survey design, the term ‘family obligations’, frequently used in related literature (Sallee et al., Citation2016), was interpreted by the inter-disciplinary research team and divided into two main activities according to recent publications (Ferrant et al., Citation2014; Sayer, Citation2005; Shelton, Citation1999; UN Women, Citation2018): household duties and parenting. Naturally, activities related to family obligations are many and diverse, such as, caring for siblings, the elderly and voluntary commitment work. This paper specifically seeks to contribute to the analysis of the main time-consuming activities for unpaid work that usually falls on women: childcare, cooking and cleaning. These activities are cited as the main time-consuming factors for unpaid work that usually falls on women.

We conducted all subsequent analyses at these two levels, adding the variables of academic performance to each profile of the doctoral student. The academic performance was defined based on two indicators: the number of years to complete the doctoral studies and the number of publications during that period, both information provided by the respondent during the survey. We used an estimation to calculate the expected study-length for respondents currently enrolled in the doctoral program. Respondents from batches later than 2018 received the standard-length of time of 3.5 years, while respondents from earlier batches (study-length higher than 3.5 years) had their length estimated by the difference of the starting year and the current year, with one year added considering this as their final year.

The online survey was widely distributed via e-mail listings accessed by current and former ZEF doctoral students across two weeks, one week in June and another in October 2021. A diversity of perspectives, disciplines, and nationalities coexist in the ZEF community, due to its diverse geographical coverage and over 20 years of operation, comprising of multiple generations of students. Addressing the research question to a target audience through anonymous individual questionnaires is a way of ensuring that many of these perspectives are represented (Garmendia et al., Citation2010; De Marchi et al., Citation2000). Besides, this approach allowed us to collect controversial opinions regarding a sensitive topic, such as gender roles, in a systematic, anonymous, transparent, and structured manner (Martinez-Alier et al., Citation1998).

After the deletion of incomplete or duplicated responses, we retained 116 responses. The statistical significance of differences between the variables was assessed using boxplots and two statistical tests: Wilcoxon Rank Sum Tests for continuous data and not normally distributed variables, and Fisher’s exact test for binary categorical variables. The survey data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel and the statistical computing environment R (R Core Team, Citation2020). The packages used were stats, dplyr (Wickham et al., Citation2018), ggplot2 (Wickham, Citation2009), tidyverse (Wickham, Citation2017), exactRankTests (Hothorn & Hornik, Citation2019), summarytools (Comtois, Citation2021).

To enhance our discussion, we used content and thematic analysis to systematically organize the qualitative data from the responses for the open-ended questions of the survey (see Appendix 1). We coded the data in an inductive manner, resulting in the emergence of a set of semantic codes or keywords, which we transformed into a few overarching themes, embodying the summary of patterned meanings of the data (Clarke & Braun, Citation2014; Joffe, Citation2012).

Results

In total, there were 116 respondents, 56 of whom were female, 57 who were male, and three who did not state their gender. The responses comprised of 34 current and 79 former doctoral students,Footnote5 of which 48 (41%) were parents. Our sample includes mostly respondents from the Global South, whereas 28% are from the Global North (North America, Europe, or Oceania – ITU Regional Classification). This sample follows a similar distribution found for all doctoral students in the program according to the official data at the Center for Development Research (ZEF) (ZEF, Citation2017). Among the topics of research, respondents cited Natural Resources and/or Ecosystems (50%), followed by Economics (39%) and Social Science (31%), which reflects the three departments from the doctoral program. Land science is a cross-cutting topic prevailing on the research lines at ZEF (ZEF, Citation2021).

During their studies, a bigger share of the respondents lived without a life partner during their doctoral studies (62%), and the house-sharing status was similar between genders (see ). Proportionally, more students from the Global North lived together with a partner (43%) compared to students from Global South countries (34%). However, for the female students, all regions represented equal house-sharing status: 35% of female respondents lived with a partner and 65% of them did not. From the total number of respondents, 25% of them decided to postpone having a partner or living together with a partner during the doctorate, considering this as a challenge for their work-life balance.

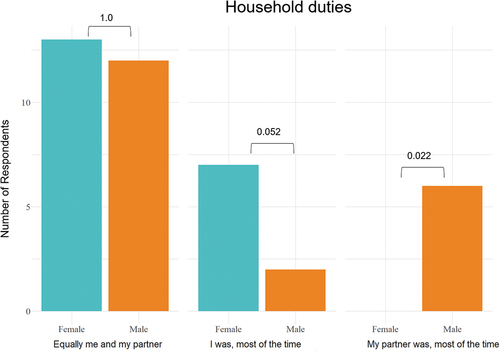

Among the respondents living with a partner, this study found significant gender differences on the share of household responsibilities (). The students responsible for household duties were mostly female, while male students equally shared or received higher support from their partners than female students (). Those additional responsibilities for the household did not affect the academic performance in general, but it could have specific impact on the study length. Students who relied more often on their partners for the household duties had a lower study length (x = 3.6) compared to students who shared the duties equally (x = 4.5, p < 0.05) or who were in charge of the household duties (x = 4.1) ().

Table 1. Differences between genders regarding family obligations and academic performance indicators

Figure 2. Share of household responsibilities among men and women during doctoral studies between partners. differences are tested for statistical significance with p-values shown above the respective bars.

Besides the household responsibilities, we assessed the experiences of doctoral students regarding parental responsibilities. The majority of respondents, both male and female, did not have children before becoming doctoral students (75%). A higher proportion was found among female students from the Global North, where 90% of the respondents did not have kids before the doctoral program compared to 75% of female students from Global South countries. For almost half of the doctoral students in our survey, matching family obligations and the workload of the doctorate emerged as the main barrier to maintain a work-life balance during the program. Therefore, 28% of them decided to postpone their plans to have children. Among the respondents who had children, a significantly higher number of male students were parents before entering the doctoral program compared to female students (p < 0.05). Around one-quarter of the total respondents became parents during the doctorate, with similar numbers between genders. The number of children per parent was also similar among the genders.

Our findings indicate that the extra parental responsibilities may have impacted the academic performance of the doctoral students in our sample. Students who had a child during the doctorate needed more time to complete their studies (p < 0.01) than the othersFootnote6. Besides, the average number of authored publications as a result of the doctoral studies was lower for parents from both genders compared to child-less doctoral students (p < 0.1). This result is in line with the perception of the respondents. When asked whether parenting was a barrier to achieving academic goals, two-thirds of the respondents answered yes or sometimes.

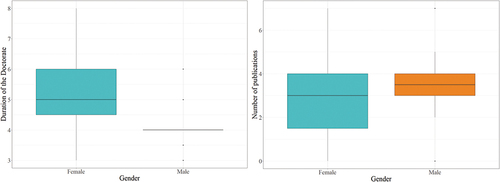

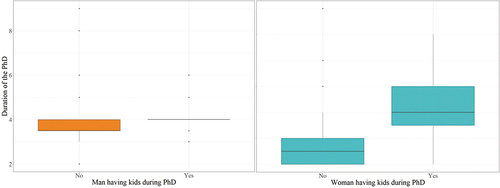

Above all, our results suggest that the additional parental responsibilities of doctoral students influenced the academic performance not only among the parents, but especially among the mothers with new-borns. While there was no difference between male and female students in our sample regarding their academic indicators, students who were mothers during the doctorate performed worse in all the indicators for academic performance when compared to fathers (,). For instance, female doctoral students who were mothers during the doctoral program took significantly longer (average 5.3 years, respectively) to complete their doctorate than male doctoral students in the same situation (average 4.1 years, respectively, p < 0.05). The combination of two factors, gender, and parenting, influencing the duration of the doctorate is confirmed when mothers are compared to child-less students and fathers. While fathers during the doctorate had the same study-length as the other male students (p = 0.20), mothers during the doctorate presented higher study length than other women (p < 0.1). These numbers indicate that mothers with new-borns faced more challenges in completing their doctorate promptly compared to fathers, who completed their doctorate in less time. Furthermore, this group of mothers published significantly less than the fathers in the same situation (p < 0.01), with a greater mean difference for mothers with more than one child before their doctorate (p < 0.01).

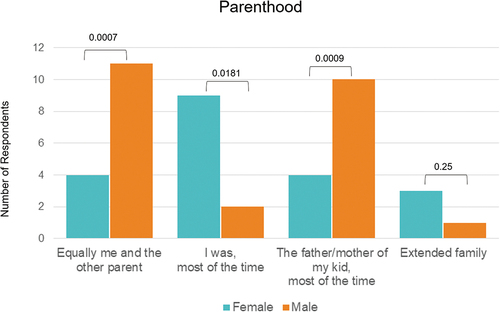

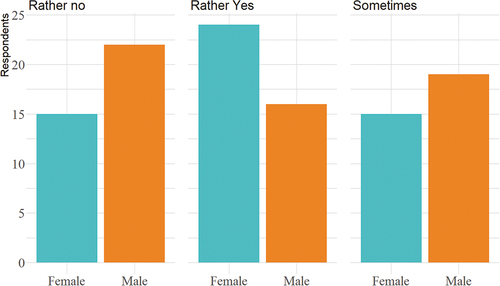

This result may reflect an unbalanced shared of parental responsibilities among genders. For both cases of parents (before and during the doctorate), mothers claimed to invest more time in parenting than men. Mothers reported significantly more often that they were mostly responsible for parenting while studying (), whereas fathers reported more often that either their partners were mostly responsible for parenting (p < 0.01), or that they were equally sharing the parenting role with their partners (p < 0.01) (). When describing barriers to achieving their academic career, the female respondents considered family obligations as a barrier more often than men (p < 0.1), while a higher number of men considered those obligations not a barrier (). Nevertheless, there was no gender difference among the survey participants on deciding whether to have children during the doctorate at ZEF or not.

Figure 3. Share of parenting roles among men and women attending the doctoral program. differences are tested for statistical significance with p-values shown above the respective bars.

Figure 4. The impact of having kids during the doctorate on (A) the duration of the program and (B) on the number of related authored publications.

Figure 5. The impact of having kids during the doctorate on the duration of the studies for (A) fathers and (B) mothers comparing to students who did not have kids during the doctorate.

Figure 6. Respondents’ perception regarding family obligations as barriers to achieving career goals in academia.

It is noteworthy that, although not statistically significant, men exhibit slightly higher average academic performance than women in general, including the group of single, child-free female doctoral students. This result may indicate that additional factors, other than family and household responsibilities, may affect the academic performance of each gender. For instance, one-third of the doctoral students mentioned that staying away from family is another challenge they faced during the doctorate, and more women than men considered being away from family support as challenging (p = 0.15) ().

Figure 7. The share of challenges in achieving a ‘work-life balance’ among men and women attending the doctoral program at ZEF.

For the open-ended question, the majority of respondents agreed that a doctorate is a full-time commitment that limits job opportunities for academic travel and fieldwork, making it very difficult for students to achieve a work-life balance. Several female respondents also mentioned that mobility restrictions – particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic – and being away from their family and partners made them prioritize family obligations rather than their doctorate, which caused delays in some aspects of the study including the dissertation defence. It is abundantly clear that the COVID-19 pandemic added another layer of challenges for both male and female respondents, with many referring to the difficulty of balancing parenting or spousal duties and doctoral studies during nationwide lockdowns and travel bans/restrictions.

An interesting point made by female respondents was how funding and the availability of childcare support was a big challenge for bearing and raising a child during their doctoral studies. For instance, some respondents mentioned how the main scholarshipFootnote7 provided by the doctoral program did not consider maternity leave as a reason to extend the duration of the funding. Therefore, its requirements were frequently regarded as a key factor in their decision to postpone or avoid having children during their doctorate.

Among the respondents who did not consider family obligations as a barrier to achieve their career goals in academia, majority were male doctoral students (61%), and the smallest proportion were women from the Global South. The men, in particular, explained how the access to a supportive network and sufficient organization and planning during their doctoral studies helped combat any challenges they faced. Some of them, in this case, contradict the female perspectives, claiming it is possible to balance an academic career and family obligations and that these challenges do not justify a negative doctoral performance.

Despite the low number of respondents from the Global North, we observed a few differences in the qualitative responses that distinguish the parenting experiences among female respondents from the Global North and Global South. Notably, women from the Global South placed a greater emphasis on the difficulties of balancing career and family obligations, citing the absence of nearby family support for childcare as a significant factor as well as the pressures of the long-hours work culture in German academic settings and the traditional gender roles that persist in society (both in ‘Northern’ and ‘Southern’ countries). Additionally, more women from the Global North highlighted their choice of being child-free which did not appear in the responses from the Global South, who rather mentioned the postponement of family plans with their partners. It was not possible to identify any significant regional differences among male respondents, most likely due to the insufficient number of responses from the Global North.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the relationship between academic performance and family responsibilities for doctoral students at ZEF analysing gender and regional differences between these variables. Based on our findings, we verified our hypothesis that family obligations of parenting and household duties were a heavier burden on and concern among women, even more for women from the Global South, pursuing a doctorate compared to men. In this section, we contextualize our key findings with similar studies and deduce potential factors as well as propose steps forward for doctoral programs at institutes, like ZEF, with a large number of international students from developing countries who face significant hardships in achieving a work-family balance while pursuing a doctorate in land science.

Gender & regional differences in family obligations and influence on academic performance

… Being an active member of the family required me to spend time away from my PhD or delay some aspects of my study in order to be able to spend time with my family.

One of the key findings from our survey revealed that more female doctoral students than male students among the respondents living with a partner were responsible for household duties and parenting (see and ). The students who were responsible for household duties were mostly female, while male students equally shared or received significantly more support from their partners than female students. In this case, the male doctoral students did not receive an equal burden of household duties while performing their study.

This gender difference in family obligations is reflected in the results from other studies emphasizing how female academics are burdened with a disproportionate share of family responsibilities compared to their male counterparts (Cech & Blair-Loy, Citation2019; McGuire et al., Citation2012; Monroe et al., Citation2008; Sallee et al., Citation2016). This article supports the existing literature in asserting that women pursuing an academic career in STEM fields, including, land science, consider work-life balance as a greater challenge (Santos & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2008; Sheltzer & Smith, Sheltzer and Smith, Citation2014). Majority of the studies indicate the persistence of traditional gender roles and stereotypes, in both developing and developed countries, as an underlying cause for work-life balance to be more challenging for women in science. According to related literature, most people have been sub-consciously socialized with gender stereotypes since childhood: women are conditioned to be ‘nurturing, caring, and comforting’, performing care-giving tasks, while men are expected to be self-reliant and dominant in the family, serving as the primary breadwinners (Bhatti & Ali, Citation2020; Liani et al., Citation2020; Monroe et al., Citation2008; Santos & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2008).

Two other crucial findings from our study showed that mothers in the doctoral program took longer to complete their doctorates and women who were mothers before entering the program authored fewer academic publications compared to fathers and child-less doctoral students. These findings confirm our first hypothesis on the imbalance of doctoral performance among fathers and mothers, indicating the exacerbated impact of family obligations on female doctoral students. These results complement the findings of previous studies which also found a prolongation of doctoral studies and a dwindling number of publications among mothers as well as married women, particularly from the Global South (Fisher et al., Citation2020; Yusuff, Citation2014). For instance, Fisher et al. (Citation2020) found that being a mother while pursuing a doctorate increased the duration by 17%, but, on the contrary, being a father reduced the duration by 14%. Previous literature provided evidence on other consequences of the disproportionate burden of family obligations among women and men with academic careers, including less time for leisure for mothers, stress and conflict in both work and household settings, and more women leaving academia altogether after having their first child (Cech & Blair-Loy, Citation2019; Else, Citation2019 McGuire et al., Citation2012; Monroe et al., Citation2008).

Furthermore, many respondents highlighted the lack of institutional and peer support for childcare and maintaining a work-life balance as an overriding concern reiterated by female academics in other studies. Liani et al. (Citation2020), among others (McGuire et al., Citation2012; Santos & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2008; Yusuff, Citation2014), described absent or limited funding for and access to affordable childcare in academic institutions. Their findings are in line with the concerns among some respondents in this study who did not receive sufficient flexibility nor financial support from their scholarship provider for bearing and caring a child during the doctoral program. Prior studies suggested that the challenges of women, as well as men, pursuing academic careers are a result of the lack of family-friendly policies, such as, paid paternity leave, limited on-site and subsidized childcare facilities, and flexibility in academic deadlines (Cech & Blair-Loy, Citation2019; Fisher et al., Citation2020).

Nonetheless, there were still a considerable number of male respondents who shared responsibility of household duties and parenting with their partners, albeit, not as much as women. This finding is in line with prior literature, particularly McGuire et al. (Citation2012) who, after performing a longitudinal study, found a sharp increase since 1988 in male ecologists sharing family responsibilities, indicating progress in gender equality within the household among younger ecologists. Our study additionally found that several male respondents considered work-life balance as a challenge, much like the female respondents. Prior studies that similarly observed fathers facing hardships, like mothers, in balancing academic goals and family obligations, suggested how a prevailing stigmatization of men choosing family over career could have contributed to the challenges and pressures fathers experienced (Monroe et al., Citation2008; Sallee et al., Citation2016).

Thus, the minimal funding and family-friendly policies from scholarship providers for parents to carry an equal parenting role is cited as key factors, combined with traditional gender roles, for why women continue to carry a heavier burden in achieving a work-life balance in academia, particularly while pursuing a doctorate. We also recognize the deeper, embedded patriarchal norms in academia that contribute to all women – both mothers and single, child-free women – facing more challenges in completing their doctorate. Family pressures are, therefore, just one part of the equation explaining why women have lower publishing rates and experience a longer duration to complete their doctorates compared to men. Besides addressing the work-family challenges that both mothers and fathers grapple with during their doctoral studies on land science, it is crucial to combat the discriminatory academic practices – by sex and regional origin – as well as highlight the insufficient mentoring and financial support, which limit the job opportunities of women, especially from developing countries (Cummins, Citation2005). Essentially, the cumulative experiences of all women, regardless of their origin and civil status, cannot risk being ignored or overlooked by academic institutions.

Trade-offs and pressures of pursuing a doctorate in land science

Academia is highly demanding and not made to balance family and parenting. It is also male dominated, even in more developed societies like Germany, where you would expect more gender balance and inclusion. (Survey Respondent, 2021)

A significant finding from this study that is sometimes overlooked in related literature is that three-quarters of the doctoral students, regardless of gender, refrained from having children or postponed their plans to start a family during the doctorate stage of their academic careers. Even so, several female respondents viewed family responsibilities as a career barrier and there were more men than women who were parents prior to the doctoral program. We consider this a culmination of several factors, one of which being the traditional gender roles and stereotypes, succumbing women to domestic pathways and ultimately slowing their career progression. The influence of traditional gender roles is a common discussion topic in related studies examining the gender imbalance in academia. Yet, only a few articles discuss how it may factor into the low number of married women and/or mothers entering doctoral programs in land science.

One of our main results that confirms our second hypothesis on the disparity of female doctoral students from the Global North and Global South, indicates that more female students from the Global North were child-free during the doctorate compared to female students from Global South countries. This finding is also aligned with a few qualitative responses where many female students from the Global South cited postponement of living with a partner and Global North women explicitly stated they did not plan or desire to be mothers. This finding could be partly linked to the heightened awareness and action on widespread gender equality, particularly in developed countries (Cech & Blair-Loy, Citation2019; McGuire et al., Citation2012), resulting in less societal stigma for women from the Global North to be child-free, compared to women in the Global South who may face more societal pressures.

Recent studies emphasize that traditional gender roles and family expectations at the household level persist in all global regions, yet they are exacerbated in countries in the Global South where gender roles were historically perpetuated by western, patriarchal powers, fundamentally contributing the higher allocation of care-giving responsibilities to women working in academia, despite both women and men having full-time careers (Liani et al., Citation2020; McGuire et al., Citation2012). However, to explain why there was still a high proportion of child-free women from the Global South (75%) in the doctoral program at ZEF, we assume it is based on their anticipation of the consequences for married women and/or mothers prioritizing academia over family life, including the aforementioned impact on academic performance, risk of divorce or separation with partners, and being far away from family support for childrearing.

Hence, for women in the doctoral program to be able to successfully complete their doctorate and pursue a career in academia they decided to ‘challenge socio-cultural norms and expectations by not getting married’ and remaining child-less, as was observed in other studies (Bhatti & Ali, Citation2020; Fisher et al., Citation2020; Liani et al., Citation2020; McGuire et al., Citation2012). These decisions can be rooted in traditional gender roles that persist across the world, where societal norms allocate majority of the reproductive and domestic labour to women, and men are primarily associated as ‘good workers’ who are not concerned with domestic issues (Liani et al., Citation2020; Sallee et al., Citation2016; Santos & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2008; Yusuff, Citation2014).

The key difference between societies in the Global North and Global South, is that the latter region adopts traditional customs where relatives share the burden of childcare and support parents in meeting family obligations. One of the survey respondents noted this difference and the anticipated challenge of pursuing a doctorate in Germany away from close relatives and friends offering consistent support in childcare:

[There are] unavoidable trade-offs between the production of new and relevant scientific knowledge with the parental tasks of educating your own children. I think this applies particularly to “Western societies”, in which the responsibility to educate children falls entirely into parents, without much assistance expected from their close social circle. (Survey Respondent, 2021)

Without this essential support system combined with the ‘gendered division of labor’ (Liani et al., Citation2020), there are more barriers women face pursuing and advancing in demanding academic careers that frequently entail relocation and international travel.

For the women who are able to have a family while working in academia, a study described how they felt ‘prejudiced by the community’ for focusing more on work instead of their families if they stayed late in the office (Bhatti & Ali, Citation2020). Consequently, the pressure on women to conform to the traditional gender roles lead to most women prioritizing families over their careers (Bhatti & Ali, Citation2020; Yusuff, Citation2014), and the small proportion of women who pursue a scientific career decide not to have children during the advanced education or training stages, that is, doctorate. The overriding perception among women in this study, along with others (Yusuff, Citation2014), is that the pressures of society and academia do not allow them to ‘have it all’, unlike men who traditionally carry less of a burden in caregiving. This would also explain the low representation of women pursuing doctorates in STEM fields, such as, land science, which typically demands more time for fieldwork and lab-work (Fisher et al., Citation2020).

Nevertheless, given the high proportion of women who were single and child-free in our sample who, alike the parents in the doctoral program, faced many challenges in achieving a work-life balance, our findings indicate that differences in academic performance were not solely led by parental responsibilities. Thus, there are many other factors that need to be considered, one of these being the lack of support networks as well as the social and financial benefits accompanied with nearby families and civil partnerships which can help women in academia meet their scientific career goals (Cummins, Citation2005). It has been argued that the absence of this support for child-free, single, female doctoral students might have resulted in cases where they face even more challenges in achieving a work-life balance and experience lower academic productivity than mothers (Davis & Astin, Citation1990; Martinez et al., Citation2013). They might also risk being excluded from the academic networks that put married women and mothers on a pedestal as the ideal pathway for a female academic (O’Leary et al., Citation1990).

The challenges are compounded for single women from the Global South completing their doctorates in a developed country, like Germany. While they may exhibit higher academic productivity than mothers, living far away from their families can be very challenging as the lack of emotional support may negatively affect their short- and long-term academic career plans. This is reflected in one of the findings on the regional differences of family obligations among doctoral students at ZEF, with there being more students from the Global North who lived together with a partner compared to students from the Global South. While we were unable to identify any attribution of regional origin to the doctoral performance, this may have led to single, female doctoral students from the Global South to face increased hardships in meeting their academic goals.

For doctoral students from the Global South with family plans and partners, we can assume they were also disadvantaged compared to students from the Global North. The additional challenges they faced include obtaining additional visa support for their partners to join them in Germany, the absent or limited funding provided by research institutes for partners who do not have children to travel to and live in Germany (McGuire et al., Citation2012; Santos & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2008; Yusuff, Citation2014), as well as the tough decision to postpone their family plans in order to focus on their academic career while abroad, preferring the added familial support of having children in their home countries (Liani et al., Citation2020).

The pandemic particularly exacerbated the disadvantages for students from the Global South living without or apart from families, who lacked the support system needed to advance in their studies, especially when unable to travel to visit family members in their home countries. Essentially, loneliness in academic settings is a key factor of academic performance which needs to be highlighted to combat the common assumption that single people can work more because they do not have parental responsibilities (Utoft, Citation2020). Recognition of the large array of problems women face, dependent on multiple contexts not just limited to their regional origins and family status, is needed in research settings for early-career land scientists to overcome the obstacles in their academic careers.

The other factor that explains our findings is the long hours work culture engrained in most research institutions and universities as documented in related studies. Universities have over time intensified their demands of academic employees, including doctoral students, by imposing long working hours (50–60 hours per week), extensive research activities, and international travel for conferences (Santos & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2008). Thus, academia promotes an ideal they expect scientists to aspire to in which the only pathway to success is through ‘more than full-time devotion’ to research productivity (Santos & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2008; Van Den Brink & Benschop, Citation2012), at the expense of their social lives (Else, Citation2019; Sallee et al., Citation2016). These ideal places incredibly high burdens to both men and women pursuing a career in academia, who are expected by society and their employers to commit equally and effectively to family and work obligations (Cech & Blair-Loy, Citation2019; Monroe et al., Citation2008; Sallee et al., Citation2016). Yusuff (Citation2014) and Santos and Cabral-Cardoso (Citation2008) explain that the arduous working norms in universities are embedded in the ‘historical male dominance’ of academia which considers family obligations as an interference in academic productivity. The academic environment is, therefore, more unfriendly to women pursuing scientific careers while traditionally bearing the brunt of family responsibilities.

Considering the findings of this study and recent evidence from related literature, the demands of a doctorate in research institutions clashes with the demands of society to conform to traditional gender roles. We found that many respondents of our study were aware of these pressures as they explained how the substantial workload and high standards of academic productivity on doctoral students made them perceive parenting as a barrier to achieving academic goals. Precisely, our research demonstrated that 28% of doctoral students decided to postpone their plans to have children and 24% of the students postponed having a partner or living together with a partner, among other trade-offs. Accordingly, the work culture and practices at research institutes could be a contributing factor to why majority of the sample of doctoral students decided not to have children before or during the program, a high likelihood cited in other cases (Santos & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2008). These ideals also potentially discourage more mothers and fathers from pursuing a career in land science or lead to many doctoral students choosing to get married and/or have children in their post-graduate careers which are typically characterized by financial stability and work flexibility (Perry et al., Citation2018).

Limitations of study

This is a sample study from a small universe that gives an overall idea of the academic challenges junior researchers face when establishing and forming a family. Although the study was randomly and widely distributed, it has the limitation that not all former doctoral students answered the survey, thus we acknowledge a potential self-selection bias. Besides, the data was only analysed without interviewing participants in order to determine further reasons why there were differences between the sexes. There was also an information gap on why many researchers viewed the balance between work and family as a challenge. Although it was not possible to deepen our understanding on the reasons behind the answers through qualitative participatory methods – such as, semi-structured interviews – we achieved the main objective of this paper by collecting key information on the facts and opinions of the professional and personal lives of current and former doctoral students.

Conclusions and recommendations

The findings from this study suggest that mothers in doctoral programs experienced more constraints in maintaining a work-life balance compared to fathers and child-less doctoral students, leading to a prolonged duration of the doctorate and lower publication rates. Ergo, majority of students postponed their plans to start a family or live with a partner, aware of the challenges parents face pursuing an academic career. These results corroborate evidence from other studies, indicating that women, especially from the Global South where strong family support networks are the cultural norm, are disadvantaged in maintaining a work-life balance while pursuing a doctorate at international research institutes in developed countries. We suggest four main factors to these findings: (1) the persistence of traditional gender roles; (2) the intensive, long-hours work culture at research institutes; (3) the limited financial support for parents pursuing doctorates; and (4) difficulty of childrearing without consistent support from relatives.

Moreover, we reiterate other studies in emphasizing that any pathway women and men decide to pursue while completing a doctorate in land science, whether it is having children, living apart from their partners or staying single and child-less, are acceptable and possible options. These personal decisions are essential aspects for doctoral programs to consider as circumstances in the household setting are inherently intertwined with the work performance. Early-career researchers, regardless of gender, civil status, and origin, are entitled to living a full and happy life that is hinged on access to the support and resources required to meet domestic and academic responsibilities, making a work-life balance achievable in academia.

We recommend academic institutes and associated funding organizations become more receptive to the concerns and challenges in maintaining a healthy work-life balance among students in their doctoral programs, especially mothers, as well as recognizing the influence of traditional gender roles on the different pathways researchers choose to take. This can be done through regular information-gathering and evaluation of students’ satisfaction and stress levels at home and at work, followed by a set of prompt actions collectively determined by doctoral students and the program’s coordination team. These actions can include the adoption of more family-friendly policies and increased access to resources to meet family and academic responsibilities, and transformation of work norms to be more flexible and accommodating to personal needs of researchers, allowing delays in academic deliverables.

Furthermore, to achieve this we also need to develop alternative metrics for academic success that are more equitable, thereby, dependent on contexts, particularly for women academics from the Global South who face additional burdens and obstacles than ‘Northern’ researchers. Additionally, when assessing academic success and developing policies on gender equality in academic institutions, less focus should be on increasing the productivity rates and quantity of research outputs for women. Rather, institutions should encourage quality and diversity of academic outputs for both women and men while maintaining a work-life balance that confronts the long-hours work culture in academia (Pereira, Citation2021).

By being more receptive to the work-family challenges, these programs will not only improve retention rates and conditions for early-career researchers, but they will also contribute to more career opportunities in land science for parents, particularly mothers, who would have otherwise been deterred from pursuing a career in land science. With the accompanied actions, we foresee a rise in gender and regional balance in scientific institutions focused on land science, followed by more scientific innovation and creativity.

In sum, this article calls for strengthening international gender equality in academic institutions which necessitates including diverse perspectives of different genders and regions. This is pertinent for centres, like ZEF, dedicated to training future land scientists who have the capacity to alleviate the concerns and experiences of marginalized women directly using and managing threatened land systems. With further qualitative and quantitative research examining how single, child-free women are disadvantaged in academia, the regional and gender differences of dropout rates of doctoral programs on land science, and the effects of marital status on academic performance among doctoral students, there is potential for a deepened understanding on the hardships and trade-offs early-career land scientists face on their journey to achieving their career goals. Essentially, this study draws attention to the importance of work-life balance for land scientists to successfully fulfil their role in developing sustainable and fair solutions to threats on land-based systems.

Above all, this study offered the unique opportunity to analyze productivity differences by gender by comparing a steady and partly-uniform sample of doctoral students under the same load of studies, in-country context, and financial conditions, but from a diverse array of countries. Therefore, the results could be scaled to other international doctoral programs in the Global North, seeking to effectively implement better practices on decreasing gender inequality among the candidates.

Ethical approval

The research team abided by the institutional and legal standards in Germany regarding ethical approval. This study was non-interventional where the sole data source were survey responses from doctoral students, meaning approval from an ethics committee was not needed for this study according to national research regulations. According to ethical guidelines, the authors ensured anonymity of all respondents and obtained their informed consent by informing them on the purpose of the survey and where the findings will be shared.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, we would like to extend our utmost gratitude to the alumni and current students of BIGS-DR who contributed to our study by responding to the survey. Secondly, the success of the survey would not have been possible without the support from the former and current academic coordinators of the doctoral program who provided essential data on ZEF as well as access to alumni mailing lists. We would also like to thank the reviewers and editor for their valuable comments that improved the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Sara Velander and Fernanda Silva Martinelli share first authorship.

2. Gender equality is defined by (UN, Citation2002) as ‘the equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men and girls and boys.’

3. Countries in the Global North are classified as members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or high-income countries typically in Europe, North America, and Australasia (Blicharska et al., Citation2017).

4. Countries in the Global South are classified as upper-middle income, lower-middle income or low-income, located in Africa, South America, and Asia (Blicharska et al., Citation2017).

5. Three respondents did not inform the enrollment situation.

6. The term ‘other’ includes the child-free students and the students who had kids before starting their doctorate.

7. Majority of the participants in the doctoral program at ZEF are funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). According to information available, the current policy of DAAD is that under certain circumstances they may provide an additional monthly allowance for accompanying family members (spouses and children) of grant holders, if their funding period is more than 6 months (DAAD, Citation2021). DAAD also permits applications from prospective doctoral students who experienced an extensive delay in their prior graduate studies due to pregnancy and childbirth, as well as caregiving responsibilities for children up to 12 years old.

8. As the length of the doctorate is 3,5 years, the drop-out rates for the candidates from the most recent batches (2018 to 2021) can still suffer changes until their final completion.

References

- Archer, L., Dewitt, J. and Osborne J. (2015). Is Science for Us? Black Students’ and Parents’ Views of Science and Science Careers. Sci. Ed., 99(2), 199–237. 10.1002/sce.21146

- Ashencaen Crabtree, S., & Shiel, C. (2019). “Playing mother”: Channeled careers and the construction of gender in academia. SAGE Open, 9(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019876285

- Bhatti, A., & Ali, R. (2020). Gender, culture and leadership: Learning from the experiences of women academics in Pakistani universities. Journal of Education & Social Sciences, 8(2), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.20547/jess0822008202

- BIGS-DR. (2021). BIGS-DR database of alumni and current students. ZEF.

- Blicharska, M., Smithers, R.J., Kuchler, M., Agrawal, G.K., Gutiérrez, J.M., Hassanali, A., Huq, S., Koller, S.H., Marjit, S., Mshinda, H.M., Masjuki, H.H., Solomons, N.W., van Staden, J., & Mikusiński, G. (2017). Steps to overcome the North-South divide in research relevant to climate change policy and practice. Nature Climate Change, 7(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3163

- BMFSFJ.(2016). Gender Equality Atlas for Germany. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend.

- Cech, E.A., & Blair-Loy, M. (2019). The changing career trajectories of new parents in STEM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (10), 4182–4187. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810862116

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. In A.C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 6626–6628). Springer.

- Comtois, D. (2021). Summary tools: tools to quickly and neatly summarize data. In https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=summarytools. R package version 0.9.9

- Cook, N. J., Grillos, T. and Andersson, K. P. (2019). Gender quotas increase the equality and effectiveness of climate policy interventions. Nat. Clim. Chang., 9(4), 330–334. 10.1038/s41558-019-0438-4

- Cummins, H.A. (2005). Mommy tracking single women in academia when they are not mommies. Women’s Studies International Forum, 28(2–3), 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2005.04.009

- DAAD. (2021). Important information for scholarship applicants. German Academic Exchange Service. https://www.daad.de/en/study-and-research-in-Germany/scholarships/important-information-for-scholarship-applicants/

- Davis, D.E., & Astin, H.S. (1990). Life cycle, career patterns and gender stratification in academe: Breaking myths and exposing truths. In S.S. Lie & V.E. O’Leary (Eds.), Storming the tower: women in the academic world (pp. 89–107). Kogan Page.

- Dawson, L., Brevik, E. C. and Reyes‐Sánchez, L. B. (2021). International gender equity in soil science. Eur J Soil Sci, 72(5), 1929–1939. 10.1111/ejss.13118

- de Marchi, B., Funtowicz, S.O., Io Cascio, S., & Munda, G. (2000). Combining participative and institutional approaches with multicriteria evaluation. An empirical study for water issues in. In S. Troina Ecological Economics(vol. 34). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00162-22 267–282.

- Else, H. (2019). Nearly half of US female scientists leave full-time science after first child. Nature. 10.1038/d41586-019-00611-1

- Ferrant, G., Pesando, M., & Nowacka, K. (2014). Unpaid care work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes. OECD Development Centre.

- Fisher, M., Nyabaro, V., Mendum, R., & Osiru, M. (2020, December). Making it to the PhD: Gender and student performance in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE, 15(12), e0241915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241915

- Fonjong, L., Fombe, L. and Sama-Lang, I. (2013). The paradox of gender discrimination in land ownership and women’s contribution to poverty reduction in Anglophone Cameroon. GeoJournal, 78(3), 575–589. 10.1007/s10708-012-9452-z

- Gao, L., & Bryan, B.A. (2017). Finding pathways to national-scale land-sector sustainability. Nature, 544(7649), 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21694

- Garmendia, E., Gamboa, G., Franco, J., Garmendia, J.M., Liria, P., & Olazabal, M. (2010). Social multi-criteria evaluation as a decision support tool for integrated coastal zone management. Ocean and Coastal Management, 53(7), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.05.001

- Hothorn, T., & Hornik, K. (2019). Exact distributions for rank and permutation tests (Version 0.8-31). The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/exactRankTests/exactRankTests.pdf

- Joffe, H. (2012). Thematic analysis. In D. Harper & A. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners (pp. 209–223). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kamau, H., Tran, U., & Biber-Freudenberger, L. (2021). A long way to go: Gender and diversity in Land use science. Journal of Land Use Science VOL 00(00). doi:10.1080/1747423X.2021.2015001. Forthcoming .

- Ledin, A., Bornmann, L., Gannon, F., & Wallon, G. (2007). A persistent problem. traditional gender roles hold back female scientists. EMBO Reports, 8(11), 982–987. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401109

- Liani, M.L., Nyamongo, I.K., & Tolhurst, R. (2020). Understanding intersecting gender inequities in academic scientific research career progression in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 12(2), 262–288. http://genderandset.open.ac.uk

- Maas, B., Pakeman, R. J., Godet, L., Smith, L., Devictor, V. and Primack, R. (2021). Women and Global South strikingly underrepresented among top‐publishing ecologists. Conservation Letters, 14(4), 10.1111/conl.12797

- Martinez-Alier, J., Munda, G., & O’Neill, J. (1998). Weak comparability of values as a foundation for ecological economics. Ecological Economics, 26(3), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00120-1

- Martinez, E., Ordu, C., Sala, M., Della, R., & Mcfarlane, A. (2013). Striving to obtain a school-work-life balance: The full-time doctoral student. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 8, 39–59. https://doi.org/10.28945/1765

- McGuire, K.L., Primack, R.B., & Losos, E.C. (2012). Dramatic improvements and persistent challenges for women ecologists. BioScience, 62(2), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.2.12

- Monroe, K., Ozyurt, S., Wrigley, T., & Alexander, A. (2008). Gender Equality In Academia: Bad news from the trenches, and some possible solutions. Perspectives on Politics, 6(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592708080572

- O’Leary, V.E., Mitchell, J.M., & Lie, S.S. 1990. Women connecting with women: Networks and mentors in the United States. In S.S. Lie, and V. O’Leary (Eds.), Storming the tower: Women in the academic world (pp. 58-74).: Kogan Page .

- Pereira, M.D.M. (2021). Researching gender inequalities in academic labor during the COVID-19 pandemic: Avoiding common problems and asking different questions. Gender, Work and Organization, 28(S2), 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12618

- Perry, E., Tessmar-Raible, K., & Raible, F. (2018). Parents in science. Genome Biology, 19(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1549-3

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

- Riegle-Crumb, C., King, B., & Irizarry, Y. (2019). Does STEM stand out? Examining racial/ethnic gaps in persistence across postsecondary fields. Educational Researcher, 48(3), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19831006

- Sallee, M., Ward, K., & Wolf-Wendel, L. (2016). Can anyone have it all? Gendered views on parenting and academic careers. Innovative Higher Education, 41(3), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-015-9345-4

- Santos, G.G., & Cabral-Cardoso, C. (2008). Work-family culture in academia: A gendered view of work-family conflict and coping strategies. Gender in Management, 23(6), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410810897553

- Sayer, L.C. (2005). Gender, time and inequality: Trends in women’s and men’s paid work, unpaid work and free time. Social Forces, 84(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0126

- Shamseer, L., Bourgeault, I., Grunfeld, E., Moore, A., Peer, N., Straus, S. E. and Tricco, A. C. (2021). Will COVID-19 result in a giant step backwards for women in academic science?. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 160–166. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.004

- Shelton, B.A. (1999). Gender and unpaid work. In J.S. Chafetz (Ed.), Handbook of the Sociology of Gender (pp 375-390). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Sheltzer, J.M., & Smith, J.C. (2014). Elite male faculty in the life sciences employ fewer women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111( 28), 10107–10112. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1403334111

- SOFA Team, and Doss, C. (2011). The Role of Women in Agriculture, ESA Working Paper No. 11-02. Rome: Agricultural Development Economics Division, The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). https://www.fao.org/3/am307e/am307e00.pdf

- Squazzoni, F., Bravo, G., Grimaldo, F., García-Costa, D., Farjam, M., Mehmani, B. and Baccini, A. (2021). Gender gap in journal submissions and peer review during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. A study on 2329 Elsevier journals. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0257919. 10.1371/journal.pone.0257919

- UN Women. (2018). Turning promises into action: Gender equality in the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development.

- UN. (2002). Gender mainstreaming: an overview.

- UNESCO, & UNESCO IESALC. (2021). Women in higher education: Has the female advantage put an end to gender inequalities? http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en

- UNESCO. (2020). Global education monitoring report - gender report: A new generation: 25 years of efforts for gender equality in education.

- UNESCO, and UIS. (2019). Women in Science, FS/2019/SCI/55. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs55-women-in-science-2019-en.pdf

- Utoft, E.H. (2020). ‘All the single ladies’ as the ideal academic during times of COVID-19? Gender, Work and Organization, 27(5), 778–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12478

- van Den Brink, M., & Benschop, Y. (2012). Slaying the seven-headed dragon: The quest for gender change in academia. Gender, Work and Organization, 19(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2011.00566.x

- Vaughan, K., Van Miegroet, H., Pennino, A., Pressler, Y., Duball, C., Brevik, E. C., Berhe, A. A. and Olson, C. (2019). Women in Soil Science: Growing Participation, Emerging Gaps, and the Opportunities for Advancement in the USA. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 83(5), 1278–1289. 10.2136/sssaj2019.03.0085

- Viglione, G. (2020). Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here’s what the data say. Nature, 581(7809), 365–366. 10.1038/d41586-020-01294-9

- Villamor, G. B., Desrianti, F., Akiefnawati, R., Amaruzaman, S. and van Noordwijk, M. (2013). Gender influences decisions to change land use practices in the tropical forest margins of Jambi, Indonesia. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change, 19, 733–755. 10.1007/s11027-013-9478-7.

- Vincent-Lamarre, P., Sugimoto, C. R., and Lariviere, V. (2020). The decline of women's research production during the coronavirus pandemic. Nature Index. https://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/decline-women-scientist-research-publishing-production-coronavirus-pandemic

- Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., & Müller, K. (2018). dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation (R package version 0.7.6). The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr

- Wickham, H. (2009). ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer New York LLC.

- Wickham, H. Tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the “Tidyverse” (R Package Version. 2017, 1.2.1.

- Winchester, H.P.M., & Browning, L. (2015). Gender equality in academia: A critical reflection. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 37(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1034427

- Wollstonecraft, M. (1792). A vindication of the rights of woman: With strictures on political and moral subjects. Printed for J. Johnson.

- Yusuff, O. (2014). Gender and career advancement in academia in developing countries: Notes on Nigeria. International Journal of Sociology of Education, 3(3), 269–291. https://doi.org/10.4471/rise.2014.17

- ZEF. (2017). ZEF: Information in brief. University of Bonn.

- ZEF. (2018). Doctoral program (BIGS-DR). Center for Development Research (ZEF). https://www.zef.de/doctoral-program.html

- ZEF. (2021). ZEF strategy 2021-2030: Serving in new local and global contexts.Center for Development Research (ZEF).