[D]on’t waste your energy trying to change opinions … Do your thing and don’t care if they like it.

Tina Fey (2011, p. 145). Bossypants, Little, Brown and Co, pp. 352.

Introduction

We are delighted to present this collection of articles under the theme ‘WomenFootnote1 in Land Science.’ The three guest editors and one editor in chief all decided to collate such an issue at a March 2021 virtual meeting of the journal’s editorial board when brainstorming ideas of current interest and timely need, for this journal to address. The Journal of Land Use Science was seen as a perfect location for such a special issue focus. The journal itself is a strong representation of excellence in the field as well as representation by gender as highlighted both in the journal co-editors and the editorial board composition. More specifically, the journal is co-edited by two lead scientists, Dr. Daniel Müller and Dr. Darla Munroe, one man and one woman. Of the 22 members of the editorial board, there are 12 men and 10 women serving in this role. The representation of female scientists in key research leadership positions is an important factor within the discourse on gender bias.

In a recently published piece in AGU Advances (Ranganathan et al., Citation2021), the authors highlight the continuing persistence of inequality within academia in the geosciences. Their research finds that while 27% of faculty in academia in the US are women, this is not equal across ranks. More specifically, while 46% of assistant professors are female, this decreases to only 19% of full professors. The researchers did not have sufficient data to determine all the causes of such discrepancies especially related to higher attrition of female researchers; however, they do discuss other research that has pointed to higher female attrition linked to existing institutional cultures and policies such as very weak or inadequate childcare and maternity leave, a lack of protection from harassment, inadequate timelines to tenure, and existing cultures of sexism all leading to academic careers becoming inaccessible to women and other historically excluded groups. This article was part of a special issue in AGU Advances addressing ‘Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the Earth and Space Sciences.’ Thus, the current JLUS issue is timely in that we are also making space for these discussions, happening in many other fields across the social and natural sciences.

According to UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), less than 30% of the world’s researchers are women (uis.unesco.org 2021) and so the goal of this special issue is twofold. First, we wish to highlight some of the amazing research being conducted and led by female research scientists within the field of land-use science. In addition, we also wish to contribute to the necessary discussions on the challenges and possible deterrents for women researchers within these same fields. The fact that such an issue could also be the very first Open Access issue for the journal was extra motivation for us to put out a call and move papers through the submission, review, and revision process as quickly as possible. It is a testament to the passion and the dedication of the authors in this issue that we received such an intellectually rich set of contributions that are scientifically important, timely, and collectively can forge an ambitious agenda for the land-system science community in its efforts to broaden and diversify in the years to come.

In the sections below, we first reflect on our experience and relations to gender equity in land-use science. We then briefly summarize three emergent themes from the issue: the coherence among the land science applications featured in the issue, the contours of the extant gender gap in land science training, research, and authorship, and finally, what opportunities exist for quickest and effective interventions. In this final section of this introduction, we draw from the insights of these authors to issue an ongoing challenge to our community – given the work that remains to be for greater gender equity in land science, what role do we all have to play?

Reflections of the editors

This issue resulted from a JLUS editorial board meeting, as part of our efforts to feature scholars from traditionally excluded or minoritized groups, as well as to reach a broader audience. Some board members brought up troubling accounts of how the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected women academics, not the least through school disruptions and other heightened family responsibilities, and that therefore, an issue featuring women and non-binary scholars in land science was sorely needed at this moment in time. Many academic disciplines and subdisciplines have been reckoning with the causes and consequences of gender disparities in science, and our community was long overdue to take stock.

In thinking through the ideas and challenges as discussed throughout this special issue, it brought to light a reflection for each of the editors of their own journey within the field of land-use science and both the many obstacles and supporters along our paths. Drs. Jane Southworth and Darla Munroe met in 2000, both as postdoctoral scholars working at the Center for the Study of Institutions, Population and Environmental Change (CIPEC) at Indiana University, directed by Elinor (Lin) Ostrom and Emilio Moran. There was especially collaborative energy on the third floor of the building that housed us, and several other female scholars, including Harini Nagendra, Dawn Parker, and Catherine Tucker. Casual discussions about recent human–environment scholarship over coffee spontaneously led to new joint projects. This hub was central for us in forming lasting professional networks that later included Karen Seto. Lin Ostrom was wonderful in mentoring and encouraging us (Southworth and Munroe), but we also quickly adopted a practice of mentoring each other: on research practices, publishing, the job search, and grant writing. A core group of women around the same career stage, placed geographically together in a vibrant research center, fomented a supportive community that launched our careers and has broadened and deepened over time. Such a highly interdisciplinary and collaborative environment, with female scientists at all levels within CIPEC, from students through leadership roles, led to a lifelong commitment of inclusion within exciting shared opportunities, many of which continue to this day. Several of us rely on other female colleagues for frequent advice, especially in our respective roles as department chairs, associate deans, or directors of programs.

Dr. Verena Seufert spent her academic adolescence during her PhD and early Postdoc years at McGill University and the University of British Columbia surrounded mostly by male mentors and colleagues, but in a lab that nonetheless offered a warm, supportive and enabling atmosphere in which all kinds of personalities and people of diverse backgrounds were able to thrive. Her experience speaks to the importance of the role of men as allies of female and non-binary land use scientists and as important enablers of gender parity in the land-use sciences, as the weight of changing academic culture to become more inclusive should and cannot be carried by women alone.

During the later Postdoc years and the transition into academic adulthood (aka assistant professorship), Verena Seufert experienced several of the obstacles that make an academic career so difficult to combine with a healthy work-life balance and with raising a family, particularly for women. Such obstacles include, for example, the need for constant mobility (in her case three international moves for different academic positions in five years) but also the challenges of bearing and raising children and starting a family while on temporary job contracts. The high demands of care work that come along with parent- and motherhood are in strong conflict with the demands of a career in which one’s performance is constantly being evaluated in the competition for too few permanent academic positions.

An incredibly important supportive anchor during this period has been – mirroring the experiences of the other editors – a network of female peers. This network does not only provide professional and emotional support and advice, but it also provides safe spaces for experimenting with different ways of collaboration and (collective) leadership rooted on values of care, inclusivity, and reflexivity (as an example, see, Care et al., Citation2021). In terms of some more concrete examples – such female peer support includes, for example, joint grant writing endeavours with a group of other academic moms in which the ebbs and flows of personal lives (e.g. sick children, or maternity leaves) are accommodated without questions, e.g. by sharing and distributing all writing, administrative and leadership responsibilities within the group, but also weekly ‘Getting sh* done’ writing sessions on zoom in which dedicated writing blocks are interspersed with spaces for sharing and discussing various professional (or personal) challenges.

Reviewing our pathways as women in land science leads to the recognition that it does not only take a village to raise a child but it also takes a community to enable a (woman’s) academic career, and that community may be led and shared with other female academics, but features important male roles too.

Featured land science research in this issue

The call for papers for this special journal issue welcomed expressions of interest to highlight the excellent and cutting-edge scholarship of women in land science. The goal of this special issue was to showcase the diverse and important contributions being made by female or non-binary scientists to the field of land use science, but also to acknowledge the challenges and gender bias women are still facing. Many of the papers are conventional research papers that just happen to feature women in the lead authorship role. Presumably, large teams across the Global Land Programme (GLP) community found in our call an opportunity for women, particularly junior or mid-career women, to lead a publication, and advancing research articles within the standard scope of the journal was justification enough for us to include them. These diverse topics defy easy classification beyond tackling important land science, and yet arguably call attention to important questions of vulnerability, equity, social axes of difference (indigeneity, motherhood, childhood, etc.) and other big questions that have long been the purview of feminist scholarship, broadly defined. The first 10 articles all fall within the categories of more traditional research addressing a diversity of topics within the field of land use science. These topics addressed by some of the leading research groups within our field, led here by female scientists, is itself a testament to the existing strengths of women within our field.

Our first paper of the special issue sets the stage for a thoughtful discussion of global tradeoffs in land systems. By identifying ‘conservation frontiers’ as the geographic expansion of conservation itself (Buchadas et al.), the authors call our attention to where and why interest is sparked in shifting or reversing prior land change. They argue that the principal driver of biodiversity loss is due to the expansion of agriculture into natural ecosystem regions. This pressure from land use change is only expected to increase as the human population grows and as demand for land-based products continues to increase. The research analyzes conservation through three specific perspectives linked to tools widely used within land system science. The authors first frame conservation as an effort to either slow or stop other frontiers. Second, the authors phrase the expansion of conservation to itself be described as its own frontier process. Finally, frontiers are presented as spaces where multiple land uses, including conservation, can interact with each other. These authors thus provide justification for analyzing conservation through these novel perspectives which allows for a bridge between the disciplines of Land System Science and Conservation Science, resulting in an innovative analysis of the social-ecological contexts in which conservation happens. Finally, these authors argue that such closer collaboration across these research communities will only provide better integration of conservation as a core component of dynamic land systems.

The second paper in the special issue looks at the quantification of oil palm expansion in Southeast Asia utilizing a novel data fusion approach (Wagner et al). The research is of significance due to the expansion of tree-based plantations and other cash crops being the largest drivers of deforestation in Southeast Asia. Classifying different types of tree-based agriculture can be a real challenge due to the spectral similarity of the species involved. Specifically, these authors argue the quantification of oil palm plantations is critical for understanding environmental and social impacts both globally and locally. While radar data and high-resolution imagery have been utilized to improve the classification and for distinguishing oil palm agriculture from forests these data are only available for more recent dates, for limited geographic extents, or are simply absent completely. These researchers therefore present a new methodology to classify land cover change related to oil palm expansion which can provide insights into how land cover classifications can be enhanced with limited data. Within their study area, significant oil palm plantation expansion occurred across their study area. Their methods that utilize data fusion techniques and are more broadly applicable due to the lack of need for radar or high-resolution imagery, which are both expensive and limited in availability, are therefore of great value to help policymakers develop sustainable land management practices.

The third paper in our special issue addresses the environmental impact of armed conflict in Colombia (Quiroga Angel et al.). The importance of understanding such impacts of conflict is of paramount importance because most armed conflicts occur in biodiversity hotspots, nearly half of which occur in forested regions. In Colombia specifically armed conflict has resulted in significant clearing of large forest tracts for the establishment of illicit crop growth. The researchers built fixed effects models taking spatial autocorrelation into account and determined that the result of the armed conflict, via the cultivation of illicit coca crops, acted to promote deforestation through indirect, immediate, and temporally linked mechanisms. While the factors that control deforestation are clearly the product of complex interactions between political decisions and socioeconomic factors, in the research presented here the growth of coca crops very clearly promoted deforestation and was a direct result of the armed conflict. The research also presented a more novel deforestation model, which did not cover a single period as a temporal unit, but rather considered each year individually to reduce the impact of interannual variation.

The next paper in the special issue (Park et al.) examines the relationship between migration and landcover change in Ohio, given rural migration is an integral component of land systems ultimately altering land management both at the origin and destination of migration. Techniques used within the research are based on statistical analysis of a PCA ordination and cluster analysis, which allows for the spatial understanding and interpretation of rural migration patterns in order to determine how urban peripheries grew and how forested communities have lost population. Quantifying and mapping these dynamics provides important information on rural migration and landcover change patterns and also highlights exciting areas for future research linked to poverty pockets and the drivers of interactions between micropolitan and rural residential preferences.

Our fifth special issue paper addresses the issue of regional land surface temperature mapping as derived from remotely sensed data in order to assess urban climates (Turner et al.). Land cover plays a significant role in determining thermal conditions in cities which has become an urgent concern globally as cities must contend with increasingly extreme and inequitable heat impacts. As such, these researchers identify a potential mismatch between the type of information provided through traditional remote-sensing-based land systems data outputs and the type of information needed for effective decisions at a city level. This study therefore examines the appropriateness of such remote-sensing-based temperature data in guiding municipal heat planning using the example of Tucson, AZ by investigating the extent to which remotely sensed estimates of land surface temperatures or a useful proxy for different climate variables at hyper-local scales. Their research is important in that they conclude that remotely sensed estimates of land surface temperature are inadequate for guiding heat mitigation at hyper local scales in urban regions.

The sixth paper in the issue provides thoughtful reflections on using remote-sensing data to study more nuanced urban patterns of change, such as growth of informal settlements in Mexico City (Tellman et al.). In such cases, additional institutional context is needed to interpret the land-cover patterns. High-resolution (10 m pixel) data are essential, but other locally specific social and institutional information regarding the varied types of land transactions, structures, and spatial footprints are essential to understanding what otherwise may seem to be chaotic changes in urban expansion. They provide a framework for comparative remote-sensing studies of ongoing urbanization internationally. Better contextual understanding of informal urban growth is imperative for understanding both environmental and social implications for large cities in the Global South.

The next paper in the special issue looks at the dynamics of forest change and their socio metabolic drivers within the concept of forest transitions (Gingrich et al.). The authors argue that understanding the drivers of forest transitions is relevant to inform effective forest conservation. In addition, the researchers highlight the importance of forest conservation and the increased use of forest products as viable climate change mitigation strategies. As such they argue that understanding how forest cover change intersects with resource use and the understanding of which pathways of forest use are compatible with ecological sustainability aims is therefore a very important and timely research frontier. The researchers utilize studies from the United States, France, and Austria. The research findings highlight the importance of forest growth conditions in explaining long-term forest dynamics and as such they also demonstrate the distinct ways in which resource use acted as drivers of forest change. In addition, their research opens new grounds for exploring the dynamics of long-term forest change.

Our eighth paper also addresses agriculture as a key driver of land use and land cover change and as a main source of deforestation (Nolte et al.). This research addresses the very particular case of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural households. More specifically, the researchers are looking at how these impacts might affect the underlying drivers of land use decisions. The researchers make the clear argument that pandemics and land use change are closely related and while individual land-use decisions are clearly complex processes embedded in global and regional economic and environmental conditions, the processes of globalization strongly shape the underlying factors of land-use change. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is therefore a significant shock that is likely to have profound impacts on agricultural households and their land-use decision making. The findings are significant given the current global pandemic and they find COVID-19 affects agricultural households’ livelihoods substantially. The researchers expect that while some households will be able to cushion the impacts of the pandemic in the short term, many will have difficulties doing so in the long term. Accordingly, these researchers found the expectation that COVID-19 will result in a more land intensive expansion of agriculture in the future, although obviously context matters and there are likely to be large variations in land-use across different smallholders. Ultimately however land-use decisions adopted by households currently at the edge of survival will be very different from those that were previously adopted by market-oriented smallholders, and so the impact of this pandemic will be significant in the longer term for land use.

Continuing with the land use and agricultural theme, the next paper addresses the issue of global food systems and food security and the need for significant transformations to halt environmental degradation (Wartenberg et al.). These researchers parameterized multinomial logistic regression models to examine drivers of cropland transitions in California. They were especially interested in simulating future crop choices under different scenarios related to climate change, water shortages, and policy response. The authors argue that agriculture fundamentally underpins human survival specifically through the provision of food, materials, and income with agricultural land use currently occupying an estimated 40% of all land globally. The research found that agricultural land use transitions were highly sensitive to biophysical factors (such as slope, evapotranspiration, and soil quality), profits, and neighborhood effects. Their conclusions determined that climate change will likely lead to significant landscape level crop changes by 2050, which would result in very significant socio-ecological consequences, and that public policy should be prepared to address such changes.

Building more broadly on the topics already covered, the final paper in this first section of our special issue looks specifically at mothers’ investments in children’s future livelihoods under conditions of growing land competition in rural Uganda (L’Roe et al.). This research presents both quantitative and qualitative analysis based on surveys of rural women regarding their plans for investing in their children’s future livelihoods. Given that in western Uganda land inheritance is how livelihood opportunities are bequeathed to children and especially for women whose control over such land has been customarily limited. Most mothers interviewed wished for their children to seek work outside of the village, and this was equal for both sons and daughters and over 80% believed investment in education would long term be much more useful to their children than the provision of land. This research is especially important given how women’s voices are much less represented in research on land markets and so this work offers a chance to hear personal experiences from such women. The research presented here could be determined to be optimistic in the sense the mothers clearly value education for both their male and female children and as such prioritizing education is a reality. However, the reality may also be that there is simply not enough land and thus the passing of land is not an option for many of the respondents. The livelihood strategies discussed will then reflect the constraints around land availability more than the choices of the mothers. The research presented raises many questions and concerns for future generations within these landscapes and regions, especially emerging from a nexus of unequal access to land-based resources between genders and generations, making such questions and challenges an area ripe for ongoing research in land use science.

As can be seen from these 10 research articles discussed above, the unifying theme of land use, especially as it relates to agricultural systems, utilizing state of the art techniques related to both qualitative, quantitative, modeling, and remotely sensed analyses, has been strongly showcased across these diverse and important contributions led by female researchers in land use science. In addition, the research highlights many geographical regions, scales of analysis, and different theoretical bases for the work all of which only contributes to the strength and interdisciplinarity of the field of land use science. While such papers are highly reflective of the excellence of research within this field, and especially as presented by these lead female authors, we must also understand, acknowledge, and discuss many of the current challenges and obstacles to women scientists within the field of land-use science. It is only when such barriers are understood that solutions can be developed. While many constraints may be well known they are not always articulated or shared within the literature in the same way that results of more traditional research is presented. It is due to these differences in presentation of such works that we invited both traditional cutting edge research scholarship papers as well as commentaries about the challenges of gender diversity working in land-use science to be submitted to this special issue. The next set of papers presented all address different challenges which we hope are useful to discuss within the field of land-use science.

Contours of the extant gender gap in land science training, research, and authorship

This second set of five papers provide compelling evidence for an ongoing gender gap despite much of the ongoing work on diversity, equity, and inclusion, across most college campuses and workplaces globally.

The first paper presented in the second grouping looks at decolonizing land management in institutions of higher education more broadly (O’Brien and Mudaliar). The piece is very interesting as it is written by a self-identified white woman educated at a liberal arts institution and a person of color educated in a formerly colonized country both existing at an institution in the Global North. The collaboration that was formed allowed the researchers to understand the implication in settler colonialism and also to acknowledge their responsibility toward ending it. More specifically, the research addresses how many institutions of higher education were indeed founded on, and continued to benefit from, the often violent dispossession of indigenous land. The work highlights the lack of inclusion of local and indigenous knowledge systems in institutes of higher education land management plans. Such local and indigenous knowledge systems have real implications for fostering resilient socio-ecological systems as well as for decolonizing institutes of higher education land management. The research presented utilizes qualitative methods to examine knowledge included within many institutes of higher education land management plans. The research results are concerning due to the almost complete absence of indigenous knowledge in such plans, which are completely dominated by scientific knowledge, followed by local knowledge, and then professional knowledge. The research concludes with the authors discussing the implications for decolonizing institutes of higher education land management both in higher education and beyond, such that these plans can then carry more weight and truly allow for a just, ethical, and sustainable future, where different knowledge systems and communities can thrive. While this research goes beyond just the inclusion of women in land science it does so in an inclusive manner which allows for a broader perspective and the inclusion of different knowledge systems all to improve land management systems more universally.

The next paper in this second section addresses the issue of positionality, “the field“, and its implications for knowledge production and ethics and land change science (Hausermann and Adomako). As with the previous research article in this section, the authors self-identify themselves as part of the research effort. More specifically, they discuss how as two geographers investigating land-use change in rural contexts, their own positionalities, as a black, Ghanian graduate student and a white, tenured professor, produce very differential fieldwork dynamics. In addition, in this work they link their own fieldwork experiences and relations to method and results. They include discussions of moments in academic spaces such as conferences, job talks, etc. where positionality also played a role in attempts to define what “counts” as land change science research. The authors argue that such conversations help examine the conditions under which fieldwork and method are conducted and as such these conversations have very important implications for knowledge production and for ethical research. In addition, they argue that how researcher positionality shapes knowledge production about land systems has remained largely unexplored within this field. Reflections on positionality both in ”the field” and within academia more broadly can thus help bolster efforts to make the field of land change science a more inclusive and interdisciplinary arena.

Looking very directly at the role of motherhood and its impact on graduate education and progress, our next paper discusses the dichotomy of domestic and academic pathways and the challenges of motherhood within such programs (Velander et al.). This research utilized online surveys to examine the interconnection between family obligations and doctoral student performance through a gender lens of international doctoral students. The researchers found more women than men responsible for family obligations with mothers specifically experiencing a longer time to completion of their doctorate and a lower publication rate overall. In addition, there was a significant finding that women from the Global North decided not to be parents due to anticipated challenges related to child care and the high demands of academia. Finally, mothers from the Global South who were found to live apart from relatives had additional constraints of early career land scientists which needed to be addressed. Such issues were significant to understand due to the underrepresentation of women in education and academia which is a societal issue which has persisted across centuries. Although there are currently more women than men in higher education women still represent only a small proportion of doctorate holders compared to the proportion of women with bachelor’s degrees globally. Additionally, authorship in publications continues to be dominated by male researchers and academia is no exception to the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions. The authors also highlight the need to undertake significant research on the experiences between women academics from the Global North and Global South which is an emerging, and as yet less discussed, issue. The researchers conclude by recommending that academic institutions and associated funding organizations become much more aware and receptive to the concerns and challenges of maintaining a work-life balance as a doctoral student. More broadly they argue that institutions should encourage quality and diversity of academic outputs for both women and men while maintaining a work-life balance.

The next paper in the special issue focuses specifically on gender and authorship patterns within the subfield of urban land science (Chen and Seto). Given how success in science is quantified, specifically in terms of obtaining grants, publishing research articles and being productive and impactful, metrics on publications and citations regarding gender differences are important to understand. These researchers look at patterns of gender and authorship in urban land science which is a relatively new field and therefore one which they felt may be less likely to be impacted by gender bias. Research findings did not support this however with results highlighting clearly the proportion of women among the most highly productive and impactful group, shrinking as they become more senior. In terms of numbers only one in 10 researchers with the highest h-index values are female, only 20% of first authors are female on the more influential papers, annually women publish less frequently than men, and have overall shorter career lengths. Overall, the researchers found that the proportion of women shrinks in groups with higher research output, citation impact, productivity, and career lengths. Although the field of urban land science is relatively young these gender differences were still apparent and this was considered due to structural inequities in academia that create and perpetuate systematic bias. As such the way forward is with institutional and policy changes which will be critical to accelerate the transition to gender parity. Some of the highlights in this research article link to occurrences and particular details of lower research productivity in the form of key research articles, citations, and lead authorship status, and these will all be returned to in the opportunities for effective intervention section below as possible mechanisms to help address and improve the situation for female land use scientists.

The final article in our special issue looks at gender and diversity in land use science overall (Kamau et al.). These researchers conducted a meta-analysis based on a systematic literature review including over 300,000 peer-reviewed journal articles. The researchers determined that female scientists and researchers with diverse cultural backgrounds, specifically those of the Global South, were underrepresented in scientific systems. Between 2000 and 2021, only 27% of all authors, out of the over 300,000 peer-reviewed journal articles, represented women. In addition, there was significant bias towards white researchers with 62% overall, followed by asian researchers at 30%, hispanic at 6%, and black researchers at 2%. The researchers determined that there was a significant need to empower women through supportive actions in order to reduce intersectional inequalities and to help achieve the sustainable development goals. In some good news, the authors did find a positive trend in terms of a closing gender gap over time, although they also argue that this comes at an exceedingly slow pace. Once again, these authors do make suggestions of what can be done to level this playfield for women academics. Some of the suggestions put forward relate to better working conditions for women, parental leave programs, mentoring programs, equal opportunities for grants, as well as overcoming patterns of systemic discrimination and creating a process of supporting future female land-use researchers and creating champions for future generations. Once more many of these suggested strategies will be highlighted below in the discussion of opportunities for effective intervention to enhance the role of women and land-use science.

Overall these five papers looking specifically at challenges and limitations placed on women in land-use science highlight a picture of inequality and discrimination. Despite this overall finding, a number of researchers do also highlight that change is occurring, all be it very slowly. In addition, a number of the papers clearly highlight differences between researchers from the Global North and Global South in terms of needs and potential intervention strategies. This collection of papers is especially exciting given the large number of strategies and possible interventions presented by these authors as potential mechanisms to improve and eradicate gender bias within our field. The next section addresses some of these potential strategies more closely and then leads directly to the discussion of next steps, which will end this special issue introduction piece.

Opportunities for effective interventions

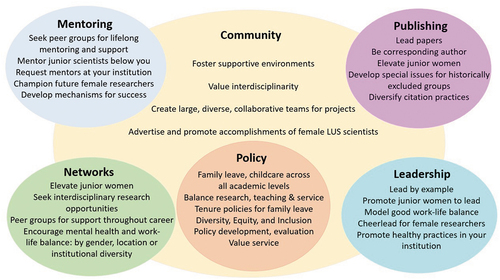

When we set out to organize and collate this issue, we were not exactly sure what we would receive in terms of submissions. It is fair to say that we were truly amazed not just at the outstanding research to be found in these pages but also in all the nuanced insights on the state of women in our interdisciplinary field. In order to provide a useful synthesis of hope for the future, and opportunities for change, we summarize several points discussed across these papers to make a case for where we need to go, as a community, and what our priorities should be (, ).

Table 1. Suggested points of action at multiple levels to advance gender diversity.

Within the field of Land Change Science (LCS) the community has clearly diversified significantly in recent years. This has not come about without significant planning and one such group, the Global Land Programme (GLP), very intentionally worked to improve and broaden representation including women, people of color, and scholars and students from the Global South in conferences, committees, and networking. Given how complicated land dynamics are and that these dynamics are clearly the outcome of complex cultural, biophysical, and political interactions, such increasing inclusivity will surely serve to improve the quality of the research being undertaken, and to improve our understanding of these systems.

Specific take-home messages that we can extract across this range of papers can be highlighted here to feature possible techniques, tools, and strategies to improve the inclusion, representation, and accessibility of women in land-use science (). The strategies range from individual actions, to actions of communities and organizations, up to the role of leaders and leadership within the field ().

Overall, we can discuss many ways as indicated here (, ) which we can improve, accommodate, encourage, and facilitate the role of women within the field of land change science. However, an important issue was raised by Velander et al. (in this issue) in which they state that an improvement of work-life balance for everyone within academia would in turn help decrease disparities within the field. While we have highlighted a multitude of mechanisms and techniques to improve the academic and work environments of women within the field of land change science, we also agree with these authors that a review and an understanding of work-life balance by all researchers within the field of land change science would possibly produce more good than any of these other mechanisms. In addition, a review of work-life balance is long overdue within academia. Expectations for success within the academic community are heavily biased to research output and research productivity often at the cost of a more diverse and happier academic community. If an academic position is to truly be a reflection across the three pillars of research, service, and teaching then surely the review process and criteria developed to evaluate an individual’s success should be equally representative of these pillars. Currently, the emphasis on research productivity above all else leads to unreasonable workloads and long hours often at the cost of mental and physical health. A better balance of time spent and related rewards across all three areas undoubtedly leads to a more balanced system and a healthier academic community. The current shock of the COVID-19 pandemic may inadvertently lead many in academia to conduct their own review of their satisfaction with their jobs and their work-life balance. Ideally, the academic community can facilitate this review at the same time as reviewing overall practices and work conditions for all members of the academic community from students, researchers, faculty, and staff to produce more equitable work conditions and result in a happier academic community.

In summary, as we reflected on these diverse contributions in their final form, we were amazed at the synthetic lessons to be drawn from this loose collection – beyond simple stipulations about authorship, we had not intended to curate any particular messages to impart. Indeed, these papers speak for themselves in their high quality and timeliness. And while there is still much work to be done for a more inclusive land science community, many of these papers point to key intervention points to build bridges for all those scholars out there, particularly outside the North American or European contexts, to contribute to our community’s knowledge production in lasting and impactful ways.

Acknowledgments

This special issue contributes to the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion efforts of the Global Land Programme (glp.earth). We thank all the authors and the many reviewers who made this issue possible.

Notes

1. Formally: our call was to all those identifying as women and non-binary scholars, or those otherwise not identifying as cis men.

References

- Care, O., Bernstein, M.J., Chapman, M., Reviriego, I.D., Dressler, G., Felipe-Lucia, M.R., Graham, S., Hänke, H., Haider, L.J., Hernández-Morcillo, M., Hoffmann, H., Kernecker, M., Nicol, P., Piñeiro, C., Pitt, H., Schill, C., Seufert, V., Shu, K., Valencia, V., … Friis, C. (2021). Creating leadership collectives for sustainability transformations. Sustainability Science, 16(2), 703–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00909-y

- Ranganathan, M., Lalk, E., Freese, L.M., Freilich, M.A., Wilcots, J., Duffy, M.L., & Shivamoggi, R. (2021). Trends in the representation of women among US geoscience faculty from 1999 to 2020: The long road toward gender parity. AGU Advances, 2(3), e2021AV000436. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021AV000436