ABSTRACT

In western Uganda, land inheritance has been the key means to bequeath livelihood opportunities to children, but land competition is increasing rapidly. Shrinking parcels and higher prices have made bequeathing land more difficult, especially for women, whose control over land has been customarily limited. We surveyed 50 rural women about their strategies and challenges investing in children’s future livelihoods. We present both quantitative and qualitative analysis of their responses. Over 80% believed it is better to invest in education rather than land, to help children secure remunerative off-farm jobs. Mothers wanted the majority of their children to leave the village to seek work elsewhere, equally for sons and daughters. Many also wished to provide a land-based safety net but worried this was no longer possible. Mothers’ assets affected both aspirations for and educational attainment of their children, highlighting potential for intensifying land competition to exacerbate inequality.

1. Introduction

1.1. From land to education

In western Uganda, as in many rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa, land has been the primary means for intergenerational transfer of wealth and livelihood security (Doss et al., Citation2012). Land can provide a homesite, food, and income. If necessary, it can generate a pulse of cash as the property itself is sold. Where there is limited access to formal financial instruments for savings, land is a key option for bestowing assets to children. The current intense competition for land in places like western Uganda threatens poor rural livelihoods and the well-being of the next generation. Rural parents are left to find alternative ways to support their children, including investing in education to prepare them to make their living from off-farm jobs in urban areas. This study documents perspectives and decisions of one group navigating these changing circumstances: mothers of school-aged children. Women’s voices are less represented in research on land markets, but their experiences of increasing land marketization and the resulting influence on children’s opportunities are important for understanding implications of agrarian transitions. This research offers a chance to hear personal experiences of women in western Uganda, and the questions driving this study reflect their concerns. Specifically, we ask:

To what extent are land-based activities providing funds for education?

Looking forward, do mothers think it is better to leave children with land or education?

Do mothers want their children to stay in the village, or do they believe they will have better futures elsewhere?

To what extent are mothers’ assets and aspirations for whether children leave the village associated with schooling outcomes for children?

We explore whether the answers to these questions depend on a mother’s own access to land and education, and whether she is planning for a son or a daughter.

1.2. Regional context

Increasing land competition and marketization has been documented in >40 African countries and recent research points to farm sizes shrinking rapidly and land values surging in many rural areas (Jayne et al., Citation2016, Citation2014; Wineman & Jayne, Citation2018). Factors accelerating land competition vary regionally and include local population growth, land grabs and investment by foreign corporations, increasing prevalence of midscale commercial and investment owners, and changing national policies pertaining to agriculture and land tenure (Hall, Citation2011; Hall et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2010). Uganda has experienced all these pressures. At 3%, Uganda’s annual population growth rate is among the highest in the world (World Bank, Citation2021), and land parcels have shrunk as they have been subdivided across inheritors. The national average landholding decreased from 2.1 to 0.9 hectares between 1991 and 2006 (Jayne et al., Citation2014). Many landowners have also sold off portions of their parcels. Although individuals most commonly acquire land through inheritance under customary tenure arrangements, market-based transactions have increased rapidly (Baland et al., Citation2007).

Beginning in 1996 and continuing through today, Uganda has enacted a series of land reforms to promote private freehold tenure over customary tribe and kin-based arrangements, in pursuit of more equitable and efficient land distribution. This included bolstering women’s control over land, which was historically limited under customary systems (Djurfeldt, Citation2020). However, reforms also liberalized land markets and encouraged large-scale agricultural investments, creating an appetite for land accumulation and speculation by powerful elites (Tumushabe et al., Citation2017). According to a recent report about Uganda, ‘shifted modes of land access from traditional means (inheritance, gifts, and squatting) to market modes hits some segments of the population hard, such as the youth that previously benefited from traditional means of land access’ (Tumushabe & Tatwangire, Citation2017). Women also remain vulnerable given that local norms are often still biased against them (Djurfeldt et al., Citation2018). In some parts of western Uganda, growing land scarcity made male clan leaders more resistant to allowing women access to land (J. Kigula in Tripp, Citation2004). Some worry that despite reforms, the combination of population growth, large-scale commercial agriculture expansion, and land speculation generate ‘a perfect storm of land tenure instability’ in Uganda (Kandel, Citation2016, p. 274), undermining women’s ability to buy their way to land security for their children.

Off-farm income plays a critical role amid these increasingly land-constrained and land-insecure situations (Djurfeldt et al., Citation2018; Dzanku, Citation2019; Marenya et al., Citation2003). As a substitute for or supplement to land-based income, off-farm jobs have long been important for diversifying livelihoods, even in rural areas (Barrett et al., Citation2001). Off-farm jobs range from working on plantations, to teaching or running a business. There are sources of off-farm income in rural areas, but urban centers offer a greater number and variety of off-farm jobs. Drivers of high rates of urbanization in the region include both the pull-factor of potential employment and the push-factor of land shortages (Kristensen & Birch-Thomsen, Citation2013). Still, urban areas do not always deliver on the promise of off-farm employment, and good jobs can be difficult to find (Kristensen & Birch-Thomsen, Citation2013).

Unlike land, off-farm jobs cannot be bequeathed to children. Education, however, can enhance a child’s likelihood of securing remunerative off-farm work (Canagarajah et al., Citation2001; Fabusoro et al., Citation2010; Marenya et al., Citation2003). Uganda instituted Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1997 and Universal Secondary Education (USE) in 2007 to make public schools freely available to all citizens. The policies improved enrollment rates, especially among girls, children from poor households, and children in rural areas, though concerns persist about the quality of public education (Deininger, Citation2003; Grogan, Citation2008). Private schools are perceived as providing a better education, but the fees can be prohibitive (Härmä & Pikholz, Citation2017), and there can be substantial charges for uniforms, books and supplies, examinations, and other incidentals even in public schools. One estimate for households in western Uganda places expenditures on school fees and requirements at an average of 50% of household income (Schmidt & Mawenu, Citation2013). Quality vocational education is particularly costly.

With limited financial resources, parents face a dilemma: securing access to sufficient land for agriculture can preclude maximizing investments in education. In development studies’ Sustainable Livelihoods framework, households devise livelihood strategies by deploying different forms of capital (financial, human, etc.). Access to capitals (or assets) is informed by the trends and shocks that make up the household’s vulnerability context, and mediated by policies and institutions (Chambers & Conway, Citation1992; Carney, Citation1999; Scoones, Citation1998). In this study, land and education are two main productive assets that parents can bequeath to their children. As land becomes more expensive, we assess the extent to which parents are working to transform it into, or substitute it with, education. Following a later emphasis on differences within households (De Haan & Zoomers, Citation2005), we consider whether investments in children’s futures depend on a child’s gender when the expected returns to land or education differ for boys and girls (Tripp, Citation2004).

Finally, we explore the extent to which there really is a choice between land and education, and with whom the choice resides. Parents can consciously choose to prioritize land or education-based pathways for children’s future livelihoods, but they are also subject to biases and structural constraints. Parents cannot ultimately control outcomes for their children (i.e. whether children stay in the village or pursue off-farm work elsewhere), but neither do a child’s livelihood options simply begin with the child’s own decisions. We examine how the decisions, assets, and aspirations of the parental generation mediate outcomes for the subsequent generation. Investments in a child’s future opportunities result from the joint efforts of mothers, fathers, and others within and beyond a child’s household, but it can be especially important to attend to women as they frequently bear greater responsibility for ensuring children’s education (Lloyd and Blanc, Citation1996), and their perspectives are often muted in discussions about land trajectories and in land administration decisions (Tripp, Citation2004; Tsikata, Citation2016). We analyze mothers’ perspectives on how to secure livelihood options for their children: when should a mother invest in increasingly costly land or in no-guarantees education?

1.3. The case of Kanyawara Parish

Our study is set in Kanyawara Parish (population ~3,000), located in an area of western Uganda known for its fertile soils and high biodiversity (Naughton-Treves et al., Citation2011). The landscape includes a national park (Kibale Forest), tea estates, and smallholder agriculture. The mild climate (1500 m.a.s.l., mean max. temp. 23.3°C), and rainfall (1719 mm/year) support a variety of food crops (e.g., bananas, maize, and cassava) most often managed by women while men have authority for cash crops. Population growth has been high, driven both by high natural fertility rates (half the population is <18 years (UBOS, Citation2019)) and waves of immigration starting in the mid-20th century (Hartter et al., Citation2015). By 2006, population density reached ~300 people per square kilometer (Hartter & Southworth, Citation2009).

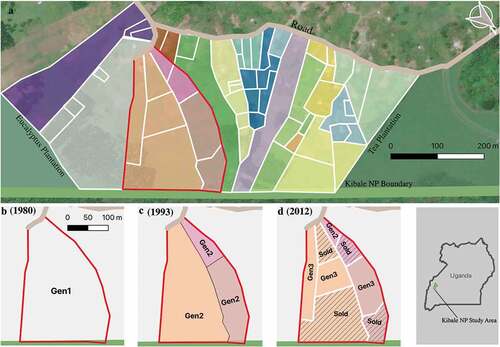

Overall wealth of Kanyawara’s residents has improved over the past generation (1996–2006), a pattern that accords with the rest of western Uganda (World Bank, Citation2021), but inequality has also increased (Naughton-Treves et al., Citation2011). Land purchases by tea companies (Naughton-Treves et al., Citation2007) and new investors have exacerbated land competition (L’Roe & Naughton-Treves, Citation2017). As is common in western Uganda, the majority of land is held under customary tenure and most residents do not have legal land titles, but they recognize property boundaries and engage in land transactions (Kabonesa, Citation2002). From 1993 to 2012, land prices doubled, the number of households tripled (L’Roe & Naughton-Treves, Citation2017), and residents complain of intensifying land scarcity (Hartter et al., Citation2015; ).

Figure 1. Shrinking parcels in one of Kanyawara’s villages. Unique colors indicate extent of parcels in 1993; white lines indicate parcel boundaries in 2012. Insets highlight changes in one parcel across 3 generations due to inheritance and sales.

Roughly one-quarter of families in Kanyawara are woman-headed (UBOS, Citation2019). Under customary tenure, women only have usufruct rights to land gained through a husband or male relative. A few women have acquired land via purchase, but the option to purchase land has been limited for most women due to poverty and illiteracy (Kabonesa, Citation2002). Women have been vulnerable to losing land when husbands die or relationships sour, and women’s limited power to control land has made fathers reluctant to bequeath land to their daughters (Kabonesa, Citation2002). Meanwhile, women bear the bulk of the responsibility for raising children and have a principal role in managing school fees. Most children aged 6 to 12 in Kanyawara attend primary school (85.5% of boys, 84% of girls) while a much lower percentage attend secondary school (32% of boys, 28% of girls; UBOS, Citation2019). Over one-quarter of adults are illiterate (UBOS, Citation2019).

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

To document impacts of land competition on strategies for investing in children’s futures, we surveyed 50 women with school-aged dependents in Kanyawara in late 2017 and 2018. We followed the surveys with focus group discussions in 2019. Members of the author team have been conducting research onsite for >30 years and two are residents. This engagement facilitated more open sharing around potentially sensitive topics of land access and concerns for children’s futures. Surveys were administered by resident coauthor DK in the respondents’ first language (Rutooro). DK went door to door over the course of several months in three contiguous villages and surveyed all willing women with children in school. Across the villages, the response rate was between 50% and 80%. Our sample includes female caregivers (we call them ‘mothers’ in the broad sense) in circumstances across the local range of income sources, marital situations, and land-holding arrangements and sizes. We did not specify that women needed to be the biological mothers, just that they were the ones responsible for school fees, and respondents included grandmothers, stepmothers, etc. Answers to survey questions were recorded in open-ended format and then encoded according to the quantitative variable definitions in . In addition to mother-level variables, we also collected information about all school-aged dependents (). We did not enumerate infants or grown children for our quantitative analysis to minimize abstract projections about future decisions and recall bias about historic practices. The broader author team conducted focus groups in Rutooro with respondents and additional mothers in 2019 to clarify and expand on survey responses. We present illustrative quotations (translated to English by DK and FK) from the open-ended survey answers and the focus group sessions.

Table 1. Summary of operationalized explanatory variables

We draw from the surveys and focus groups to answer four questions about the links between land and education in Kanyawara. We summarize trends for the group as a whole and then examine whether answers depend on a mother’s own access to land, education, and income.

2.2 To what extent are land-based activities providing funds for education?

Women were asked to describe income sources they used to pay school fees for their currently enrolled children. Respondents could indicate multiple sources and often did. Women included income from their husbands when relevant, e.g. if school fees were paid partly from a husband’s salary as a motorcycle taxi driver. Sources were coded into land-based (selling crops, livestock, tea, timber, or firewood from one’s own farm) and non-land-based categories (e.g., businesses, salaries, or plantation workers). We report resulting descriptive statistics and the outcomes of bivariate tests for differences in the types of women likely to use certain strategies. We used nonparametric Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests for ordinal outcomes (wealth ranking), Student’s T-tests for continuous outcomes (land holdings and years of education), and two-sample tests for proportions for binary outcomes (whether fathers contribute).

2.3. Do mothers think it is better to leave children with land or education?

We report descriptive statistics supplemented with illustrative quotations from the answers to the survey questions: ‘Do you think it is better to leave children with land or education? Why?’ We present a correlation matrix between mother-level explanatory variables and the propensity to say that it is better to leave children with land (or with both land and education). Pearson correlation coefficients with dichotomous variables produce equivalent t-statistics and p-values to a t-test on the continuous variable over the dichotomous one. We use a correlation matrix because explanatory factors like mothers’ land assets, education, wealth, and support from fathers are often correlated, and in this small sample we are cautious about causal interpretations.

2.4. Do mothers want their children to stay in the village, or do they believe they will have better futures elsewhere?

For each enumerated child (school-aged dependents, n = 144), women were asked where they hoped that child would live when they grew up. The open-ended responses were encoded. ‘On family land’ and ‘nearby in the village’ were common near-verbatim responses – these were preserved as unique categories. We combined variations on ‘Fort Portal’ and ‘Kampala’ into a category for ‘urban centers’ and created a separate category for less specific answers indicating that the mother did not want the child to stay (e.g. ‘elsewhere’) or that finding a job was more important than a particular location (e.g. ‘wherever there is work’). A final category contained responses that were unspecific (e.g., ‘it is for him to decide’) or missing. We report descriptive statistics and illustrative quotes. We also performed bivariate tests. At the child level, we conducted chi-square tests between a child’s gender and where mothers wanted them to live. At the mother level, we include the proportion of children that mothers wanted to stay in the village (both ‘on family land’ and ‘nearby in the village’) in the correlation matrix with mother-level explanatory variables.

2.5. How do mothers’ assets and aspirations for where children will live affect schooling outcomes for children?

We constructed a set of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) models predicting each child’s educational attainment. Educational attainment was encoded as a numerical equivalent of the highest grade-level reached. We predicted educational attainment as a function of both child-level variables and mother-level variables, as summarized in . As an additional child-level explanatory variable,we included a dichotomous variable set to 1 when mothers wanted children to live ‘on family land’ or ‘nearby in the village,’ proxying mothers’ aspirations for each child with respect to urban employment vs. finding space within the local land market. We present three models with differing explanatory variables to demonstrate the extent to which results are robust to inclusion of different predictors.

3. Results

3.1. Land-based activities (unevenly) provide funds for children’s education

Land-based activities provided the means to fund children’s education for 78% of respondents. Only 8% reported having sold some land to pay for education. Most commonly, women sold food crops (67%) or livestock (43%), but some also sold tea (12%) and wood from tree plantations (10%). Selling tea was championed by local women’s groups as a financially sustainable solution for mothers to provide school fees, but access to this option was un even. Mothers who sold tea or trees to pay for education were wealthier (p < 0.001), had access to more heritable land (mean: 1.3 ha vs. 0.4 ha, p < 0.001), and were more likely to have a husband contributing to school fees (90% vs. 51%, p < 0.05). Many women had children from multiple fathers. Overall, 41% of respondents reported that fathers did not contribute to funding education for at least some of their children (because he was dead, they were separated, he was a drunkard, etc.). 45% reported using off-farm income for school fees – these women tended to be wealthier (p < 0.05) and more educated (6.3 vs. 3.7 years of education, p < 0.05). Off-farm income sources included small business (e.g. selling beer), picking tea at commercial plantations, and a few salaried options like nurse or teacher. When asked what they would have done with the money if they had not been using it for school fees, respondents listed a variety of large investments, e.g. ‘buy land’ (n = 23), ‘build a good house’ (n = 12), ‘invest money in a business’ (n = 9), and ‘buy livestock’ (n = 8); – implying that fees are substantial and there are indeed opportunity costs to investing in education.

3.2. It is difficult to pass on land; education is preferred

The 50 women in our study reported owning a median of 1 heritable acre (0.4 ha) in 2017 (range: 0 to 2.8 ha), where ‘owning’ predominantly referred to land they accessed through their husbands. 70% reported that they live on their husband’s land and 22% on land inherited from their family. Only four (8%) had bought land for themselves. They also rented or used an average additional 0.24 ha of land owned by others, often on relatively large parcels of absentee owners. Most (~70%) say they plan to pass on land to their children, but they qualify this by saying that it is not actually theirs to pass on. Many expressed frustrations with customary norms around marriage and inheritance. For example, women and their children are sometimes ‘chased off’ land inherited from their family by male relatives, and land from their deceased husbands often goes to his children rather than to her. When women legally marry (usually only an option for wealthier families), they are more protected under Uganda’s land and property laws, but most marriages are customary and favor the husband with respect to property and inheritance.

We as women of Uganda, we have no power of inheriting - those powers belong to men, and women are suffering a lot in terms of looking after the kids. - 45 yrs., 0.4 ha of ‘husband’s land’, 4 years of education

As women, we are in trouble. When you get married, you start farming and planning for your children, but a man can bring more children from outside, and they also get a share on that land, because the men are in control. - 37 yrs., husband left but she stays on his 0.4 ha parcel, no education

Even when mothers are more confident about their right to pass on land to their children, they worry about farm size. Only 20% believe they have enough land for their children to inherit and only 26% think it will be possible for their children to buy land nearby in the community.

In answer to the direct question ‘Is it better to leave your kids with land or education?’ 82% said education, 6% said land, and 12% insisted that mothers must do both. 41% explicitly made the point that with education, children can make enough money to buy their own land. Others prioritized education because it helps children to plan for themselves, it can empower daughters, it can help children get a good job to support themselves and their parents, and children could not sell it and ‘remain with nothing’.

A good education - because when they are educated and get jobs, they will buy their own land. - 50 yrs., 0.4 ha of ‘husband’s land’, no education

Both, because if you don’t educate the children, they will sell the land looking for a better life and at the end you find them in trouble. - 37 yrs., 0.4 ha of ‘husband’s land’, no education

Most of the women [here] are not educated and men are ignoring them. Once you are educated a man cannot ignore you, and if he does, you can manage to do what you want. - 27 yrs., 0.2 ha of ‘husband’s land’, 7 years of education

Those preferring to leave land explained that it is hard to find a job and that a child needs a starting point or place to stay.

It is better to have plenty of land because jobs here are few. – 28 yrs., 0.2 ha of ‘husband’s land’, 4 years of education

Education here in Uganda is very difficult because most families have no money to put their kids in good schools, and you find someone has sold land to pay school fees but at the end you find the kids are at home with no job and then you suffer again. −49 yrs., 0.8 ha of land from her late husband, 12 years of education

Notably, those with least secure land access (women who rented or borrowed more land and women with less help from fathers for school fees) were more likely to say that it is important to leave a child with land ().

Table 2. ‘Where do you hope child X will live when they grow up?’

Table 3. Correlation matrix between mothers’ circumstances and perspectives

Table 4. OLS models predicting children’s educational attainment

3.3. Mothers want the majority of their children to leave the village

When answering where they wanted each of their children to live when they grow up, for 43% of their dependents (49 of 114), mothers expressed hopes that they would stay in the community. For the other 56% of enumerated children, mothers either explicitly said they wanted them to end up in urban centers, or that they should go wherever they find work. The most mentioned destination was Fort Portal, the ~60,000-person district capital 20 km away (n = 45 children), but several also mentioned larger cities like Kampala.

I want my child [female in secondary school] to stay in Kampala because chances of her getting jobs are higher than when she is in a village. −55 yrs., businesswoman, no husband, stays on land inherited from her mother and has bought her own land, 6 years of education

There was no statistically significant association between gender of children and where mothers wanted them to live (), but that is not to say that gender did not enter mothers’ calculations. Although sons were viewed as more likely to inherit family land, women thought daughters would take better care of mothers in their old age.

I want my girls to go far away from me because sometimes girls misbehave, and I want to stay with the boy [son] because when he grows up, he will marry and build. −32 yrs., 0.2 ha of ‘husband’s land’, 10 years of education

I want my girl to be near me because when I grow old, I may have no one to help me.” - 39 yrs., no education, no husband, 0.8 ha of land from her father’s family

Roughly half (52%) of respondents wanted at least one of their children to stay in the village. Even when they hoped children would go elsewhere for work, mothers still wanted the option to leave children land in the community. As one woman said: ‘if they don’t have land, where will they be buried?’ Many mothers expressed concerns that it may be difficult for even educated children to find jobs, and with no land left for them in the village, they would have no safety net.

Mothers with less education, less help from fathers, more rented or borrowed land, and lower wealth rankings tended to want a higher proportion of their dependents to stay in the village (). Essentially, those with least means to support children were also the ones who wanted them to stay on in the rural village, while those who were better off were more likely to want children to leave.

3.4. Mothers’ assets and aspirations influence children’s opportunities

In models of educational attainment, a child’s level in school (mean: 6.1, range: 1–15) is predicted by child-specific and mother-level characteristics, including whether the mother wants the child to stay in the village. Reassuringly, a child’s age accounts for most of the explanatory power for the grade a child attains (, Model 1). After controlling for age, there is a significant negative effect on educational attainment when a mother says she wants the child to stay in the village (, Models 2 and 3), implying that mothers may invest more in a child’s education when they want the child to leave the community for a non-farm job. The causality here could run the other way – mothers could also be basing their desires for their children’s futures partially on a child’s aptitude in school. The relationship between these variables is suggestive but should be interpreted cautiously.

For [my first daughter], I want her when she completes schooling to look for a job and work in Fort Portal or Kampala. For [my son], I want him to stay on family land, get a wife and marry. And [my other daughter], she will stay with me until she has looked for what to do because she is dull in school. - 38 yrs., 0.1 ha of land from husband who died, primary school education

Girls tend to stay in school longer – a trend corroborated by conversations with a local school administrator. When parent characteristics are included, we see children with more educated mothers also tend to stay in school longer. Controlling for mothers’ education, the wealth ranking also has marginally significant positive effect on educational attainment. Meanwhile, whether fathers help with school fees and the amount of heritable land the mother has access to do not seem to affect educational attainment of children. This accords with women’s assertion that they often bear the brunt of paying for school fees and they do what it takes to provide opportunities for their children’s education, even when that means growing crops on rented land.

4. Discussion

Land has long been the principal means for generating a livelihood in rural sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). It is also one of the most durable productive assets to bequeath to the next generation. Yet as parcels shrink and land prices rise, many of today’s children face a future without a land inheritance. A primary alternative tool for transferring livelihood opportunities from one generation to the next is education. We find that land-based activities still provide the means for 78% of the mothers in this study to pay for school. However, looking forward, the clear majority (82%) of mothers reported that it is better at this point to leave their children with education than with land. Indeed, the women in this study are investing in education: their children have completed more schooling than they have, and children are rarely pulled from school to work on the farm, as was previously common (Naughton-Treves, Citation1997). Mothers wanted more of their children to seek livelihoods elsewhere than stay in the village, and women’s assets and aspirations for their children were correlated with children’s educational attainment. We did not find that daughters had lower educational attainment, nor that mothers had systematic preferences about equipping sons to leave the village to look for jobs.

To some extent, mothers’ strong preference for investing in education reflects optimism. Mothers hope education will help their children plan for their future and compete for well-paid jobs in cities, and/or purchase their own land if they want to farm. Several emphasized that educated girls, in particular, will be able to reject abusive relationships and have more say in property ownership. However, women also expressed doubts about relying on education to secure livelihood options for their children. Indeed, despite universally accessible education policies, public education in rural Uganda does not necessarily prepare children to compete for well-paid jobs. A child who starts schooling at the age of 4 in Uganda is only expected to complete 6.8 years of school by their 18th birthday, compared to the SSA average of 8.3, and 2.5 years are considered ‘wasted’ due to poor quality of education (World Bank, Citation2021). Further, mothers’ doubts about the future availability of off-farm jobs are warranted: by some estimates, the Ugandan economy would need to generate ≥700,000 new non-farm jobs annually to keep up with growth in the labor force, far beyond the current increment of 75,000 (World Bank, Citation2021).

Mothers’ prioritizing education may also reflect the harsh reality that passing on land is not an option for many of our respondents. By Ugandan law women can control the bequeathing or sale of land they have purchased, but the local reality is that most acquire land through customary channels (inheritance and (informal) marriage) and suffer insecure tenure. Women’s rights activists in Uganda have made important progress improving women’s authority over land, and in April 2021, Ugandan parliament passed ‘The Succession Amendment Act’, a bill helping protect property inheritance rights of widows and children when a man dies without a will (Parliament of Uganda, Citation2021). Despite substantial legal achievements, challenges remain, both because women often hold less power in their marriages and because land is becoming expensive. Several women’s comments reflect stark gender inequalities within conjugal relationships. This matches regional trends in which girls have caught up with boys in enrollment in primary and secondary education but continue to face discrimination in other aspects of their lives (UNICEF, Citation2020).

For many mothers, the ideal option would be to leave children well educated and with at least a small plot in the village, even if only for cultural ties, supplementary income, or as an emergency back-up plan. The importance of land as a safety net has been previously documented in this site (Naughton-Treves et al., Citation2011) and profoundly highlighted again during Uganda’s recent experience with COVID-19 (FAO, Citation2020). Some experts predict that Uganda’s emerging land markets will improve equity (Baland et al., Citation2007; Mwesigye et al., Citation2017), but as the local price of land doubled in the space of a generation, only four of the 50 mothers managed to purchase their own small parcels. Similarly, it is increasingly difficult for the women’s children to purchase more land in the community. This is a serious problem when the local median parcel size is 0.2 hectares, <1/3 as large as in the previous generation, and a far cry from the 4-acre (1.6 ha) Farm Prosperity Model championed by Uganda’s president (Atukunda, Citation2019). Other scholars share concerns that inequitable tenure arrangements across genders and generations will stymy possibilities for inclusive agricultural intensification in Africa (Fischer et al., Citation2021; Haggar & Rodenburg, Citation2021).

Ultimately, it is difficult to know the extent that mothers truly ‘choose’ to bet on education over land to provide opportunities for their children. Livelihood ‘strategies’ sometimes reflect constraints more than choices (De Haan & Zoomers, Citation2005). In our study, some did have choices: mothers who preferred their children to leave and seek their fortunes elsewhere and who kept their children in school longer tended to be wealthier, more educated, and have access to more heritable land. Their children are more likely to have the opportunity to leave for a good job, and also to remain with a safety net of inherited land in the village. However, the more prevalent and troubling situation is to have very limited choices, with neither land nor education to give. It is telling that, paradoxically, those mothers with the least and most tenuous claims to land are more likely to want their children to stay in the community but have less land to bequeath and less means to ensure good education for children. Their children are more likely to be squeezed out of rural land ownership and forced to look for livelihoods elsewhere, ending up with neither job-ready educational credentials nor the safety net of inherited land. Whether mothers thought children would be better off staying in the village or seeking livelihoods elsewhere depended on the options they expected children to have outside the village. One outcome that women spoke of with hushed anxiety was for children to seek work with unregulated companies shipping youth to places like Dubai, where women feared they would ‘suffer’.

Our study offers a grounded perspective on how vulnerable groups live through the region’s increasing land competition. Our findings on rural women’s preferences for education versus land could be strengthened by additional research assessing preferences of men and of children. Other research documenting livelihood decisions of youth has also found that perception of land scarcity is adriver of migration to urban areas for young men in Uganda (Kristensen & Birch-Thomsen,Citation2013).

Understanding the personal dilemmas accompanying broader changes in rural land use helps to identify potential policy mechanisms for mitigating the tendency for rising inequality during these transitions. Policies must consider how gendered access to land can influence livelihood trajectories (Basu & Galiè, Citation2021), and how barriers to pursuing non-land-based livelihoods and limited options for transferring assets across generations can exacerbate the effects of rising land competition (Fischer et al., Citation2021; Lindsjö et al., Citation2021).

We conclude that despite most mothers’ efforts and intentions, some children will not have the training to compete for jobs in cities nor can they count on inheriting enough land to farm. This troubling scenario matches the pattern of cyclical disadvantages described in other land-scarce areas (Marenya et al., Citation2003). It is an all-too-common phenomenon that the poorest of the poor are most likely to be disadvantaged by economic growth and market liberalization (Ravallion, Citation2003). Nonetheless, it is worth attending to in this context because land-based livelihoods have long been a refuge for people at the margins of the cash economy, and education is meant to be the great equalizer, reducing the degree that disadvantages are transferred across generations. It is important to assess whether these tenets hold true as land competition increases. We demonstrate that relative advantages in the present generation will influence livelihood positioning of the next generation, and that increased pressure on land places increased pressure on education to provide opportunities to smooth inequalities. The way that livelihood decisions, and potentially subsequent changes in land use, emerge from a nexus of unequal access to land-based resources between genders and generations is a ripe area for ongoing research in land use science.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Djurfeldt, A.A., Dzanku, F.M., & Isinika, A.C. (Eds.). (2018). Agriculture, diversification, and gender in rural Africa: Longitudinal perspectives from six countries (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Atukunda, M. (2019). Mbarara district to commence implementation of Museveni’s 4-acre farming model. Chimp Reports, https://chimpreports.com/mbarara-district-to-commence-implementation-of-musevenis-4-acre-farming-model/

- Baland, J., Gaspart, F., Platteau, J., & Place, F. (2007). The distributive impact of land markets in Uganda. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 55(2), 283–311. https://doi.org/10.1086/508717

- Barrett, C.B., Reardon, T., & Webb, P. (2001). Nonfarm income diversification and household livelihood strategies in rural Africa: Concepts, dynamics, and policy implications. Food Policy, 26(4), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9192(01)00014-8

- Basu, P., & Galiè, A. (2021). Nested scales of sustainable livelihoods: Gendered perspectives on small-scale dairy development in Kenya. Sustainability, 13(16), 9396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169396

- Canagarajah, S., Newman, C., & Bhattamishra, R. (2001). Non-farm income, gender, and inequality: Evidence from rural Ghana and Uganda. Food Policy, 26(4), 405–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9192(01)00011-2

- Carney, D. (1999). Livelihood approaches compared: A brief comparison of the livelihoods approaches of the UK Department for International Development (DFID), CARE, Oxfam and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Department for International Development.

- Chambers, R., & Conway, G. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. IDS Discussion Paper, 296. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/123456789/775

- de Haan, L., & Zoomers, A. (2005). Exploring the frontier of livelihoods research. Development and Change, 36(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00401.x

- Deininger, K. (2003). Does cost of schooling affect enrollment by the poor? Universal primary education in Uganda. Economics of Education Review, 22(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(02)00053-5

- Djurfeldt, A.A. (2020). Gendered land rights, legal reform and social norms in the context of land fragmentation—A review of the literature for Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. Land Use Policy, 90, 104305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104305

- Doss, C., Truong, M., Nabanoga, G., & Namaalwa, J. (2012). Women, marriage and asset inheritance in Uganda. Development Policy Review, 30(5), 597–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2012.00590.x

- Dzanku, F.M. (2019). Food security in rural sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the nexus between gender, geography and off-farm employment. World Development, 113, 26–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.017

- Fabusoro, E., Omotayo, A.M., Apantaku, S.O., & Okuneye, P.A. (2010). Forms and determinants of rural livelihoods diversification in Ogun State, Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 34(4), 417–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440041003680296

- FAO. (2020). National agrifood systems and COVID-19 in Uganda. Effects, policy responses and long-term implications ( pp. 13). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Fischer, G., Darkwah, A., Kamoto, J., Kampanje-Phiri, J., Grabowski, P., & Djenontin, I. (2021). Sustainable agricultural intensification and gender-biased land tenure systems: An exploration and conceptualization of interactions. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 19(5–6), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1791425

- Grogan, L. (2008). Universal primary education and school entry in Uganda. Journal of African Economies, 18(2), 183–211. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejn015

- Haggar, J., & Rodenburg, J. (2021). Lessons on enabling African smallholder farmers, especially women and youth, to benefit from sustainable agricultural intensification. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 19(5–6), 636–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1898179

- Hall, R., Scoones, I., & Tsikata, D. (2017). Plantations, outgrowers and commercial farming in Africa: Agricultural commercialisation and implications for agrarian change. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(3), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1263187

- Hall, R. (2011). Land grabbing in Southern Africa: The many faces of the investor rush. Review of African Political Economy, 38(128), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2011.582753

- Härmä, J., & Pikholz, L. (2017). Low Fee Private Schools in low-income districts of Kampala, Uganda ( pp. 57). CapitalPlus Exchange Corporation.

- Hartter, J., Ryan, S.J., MacKenzie, C.A., Goldman, A., Dowhaniuk, N., Palace, M., Diem, J.E., & Chapman, C.A. (2015). Now there is no land: A story of ethnic migration in a protected area landscape in western Uganda. Population and Environment, 36(4), 452–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-014-0227-y

- Hartter, J., & Southworth, J. (2009). Dwindling resources and fragmentation of landscapes around parks: Wetlands and forest patches around kibale national park, Uganda. Landscape Ecology, 24(5), 643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-009-9339-7

- Jayne, T.S., Chamberlin, J., Traub, L., Sitko, N., Muyanga, M., Yeboah, F.K., Anseeuw, W., Chapoto, A., Wineman, A., Nkonde, C., & Kachule, R. (2016). Africa’s changing farm size distribution patterns: The rise of medium-scale farms. Agricultural Economics, 47(S1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12308

- Jayne, T.S., Chapoto, A., Sitko, N., Nkonde, C., Muyanga, M., & Chamberlin, J. (2014). Is the scramble for land in Africa foreclosing a smallholder agricultural expansion strategy? Journal of International Affairs 67(2), 35 http://www.jstor.org/stable/24461734.

- Kabonesa, C. (2002). Gender relations and women’s rights to land in Uganda: A study of Kabarole district. Western Uganda. East African Journal of Peace and Human Rights, 8(2), 227–249.

- Kandel, M. (2016). Struggling over land in post-conflict Uganda. African Affairs, 115(459), 274–295. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adw001

- Kristensen, S.B.P., & Birch-Thomsen, T. (2013). Should I stay or should I go? Rural youth employment in Uganda and Zambia. International Development Planning Review, 35(2), 175–201. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2013.12

- L’Roe, J., & Naughton-Treves, L. (2017). Forest edges in western Uganda: From refuge for the poor to zone of investment. Forest Policy and Economics, 84, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2016.12.011

- Lindsjö, K., Mulwafu, W., Andersson Djurfeldt, A., & Joshua, M.K. (2021). Generational dynamics of agricultural intensification in Malawi: Challenges for the youth and elderly smallholder farmers. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 19(5–6), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1721237

- Lloyd, C. B., & Blanc, A. K. (1996). Children’s Schooling in sub-Saharan Africa: The Role of Fathers, Mothers, and Others. Population and Development Review, 22(2), 265–298. 10.2307/2137435

- Marenya, P.P., Oluoch-Kosura, W., Place, F., & Barrett, C.B. (2003). Education, nonfarm income, and farm investment in land scarce Western Kenya. (No. 14 Basis Briefs, 4). University of Wisconsin Madison.

- Mwesigye, F., Matsumoto, T., & Otsuka, K. (2017). Population pressure, rural-to-rural migration and evolution of land tenure institutions: The case of Uganda. Land Use Policy, 65, 1–14. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.03.020

- Naughton-Treves, L., Alix-Garcia, J., & Chapman, C.A. (2011). Lessons about parks and poverty from a decade of forest loss and economic growth around kibale national park, Uganda. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(34), 13919–13924. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1013332108

- Naughton-Treves, L., Kammen, D.M., & Chapman, C. (2007). Burning biodiversity: Woody biomass use by commercial and subsistence groups in western Uganda’s forests. Biological Conservation, 134(2), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.08.020

- Naughton-Treves, L. (1997). Farming the forest edge: Vulnerable places and people around kibale national park, Uganda. Geographical Review, 87(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.2307/215656

- Parliament of Uganda. (2021, March 31). Inside the new Succession law, Parliament of the Republic of Uganda. https://www.parliament.go.ug/news/5053/inside-new-succession-law

- Ravallion, M. (2003). The debate on globalization, poverty, and inequality: Why measurement matters. International Affairs, 79(4), 739–753. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00334

- Schmidt, O., & Mawenu, R. (2013). How do low income parents pay school fees? A diary based inquiry from Western Uganda. European Microfinance Research Conference, Norway, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314118891_How_do_low-income-parents_pay_school_fees_-_A_diary-based_inquiry_from_Western_Uganda

- Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. IDS Working Paper 72. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

- Smith, P., Gregory, P.J., van Vuuren, D., Obersteiner, M., Havlík, P., Rounsevell, M., Woods, J., Stehfest, E., & Bellarby, J. (2010). Competition for land. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365(1554), 2941–2957. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0127

- Tripp, A.M. (2004). Women’s movements, customary law, and land rights in Africa: The case of Uganda. African Studies Quarterly, 7 4 , 1–19 215-2448 https://asq.africa.ufl.edu/files/v7i4.pdf .

- Tsikata, D. (2016). Gender, land tenure and agrarian production systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, 5(1), 1–19 doi:10.1177/2277976016658738.

- Tumushabe, G., Tatwangire, A., & Mayers, J. (2017). Catching up with the fast pace of land access change in Uganda. (No. 17415 IIED Briefing Papers 4). International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Tumushabe, G., & Tatwangire, A. (2017). Understanding changing land access issues for the rural poor in Uganda. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

- UBOS. (2019). 2018 Statistical Abstract ( pp. 345). Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

- UNICEF. (2020). 25 years of uneven progress: Despite gains in education, world still a violent, highly discriminatory place for girls. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/press-releases/25-years-uneven-progress-despite-gains-education-world-still-violent-highly

- Wineman, A., & Jayne, T.S. (2018). Land prices heading skyward? An analysis of farmland values across Tanzania. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 40(2), 187–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppx038

- World Bank. (2021). Uganda—Overview. ( Text/HTML). https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/uganda/overview