?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study employed Contingent Valuation and Discrete Choice Experiment methods to investigate the potential of a Payment for Ecosystem Service mechanism that incentivizes sustainable land use practices by determining the willingness of ecosystem service beneficiaries to pay for delivery of services via adoption of sustainable land use practices by upland poor, ethnic minority communities, and vice versa, the willingness of communities to adopt such practices upstream of Vu Gia river, central Vietnam. From the users’ side, 64% and 56% of pooled respondents said they are willing to pay a higher rate for water and electricity consumption, respectively, if upstream watershed management is improved. On the providers’ side, WTA was high if the conditionality is relaxed. Our findings suggest a fundamental challenge in designing PES that matches the needs of buyers and providers – a scheme that ensures ecosystem service flows but does not impose stringent rules that limit stakeholders’ participation.

Introduction

While terrestrial biodiversity and ecosystems have been continuously threatened, neoliberalisation of biodiversity and ecosystem conservation offers opportunities to mobilize resources (financial, human and technical) from various sources for conservation. Many schemes have been tried with some certain successes (and failures) including market-based incentive instruments, tradable permits, REDD+, debt for nature swap, and payment for ecosystem services (PES) among others (Anderson et al., Citation2010; Bigger & Dempsey, Citation2018; Thomas & Theokritoff, Citation2021). Among them, PES has been fast growing as a promising solution to provide conditional incentives that motivate land-users to adopt environmentally beneficial land use practices (Farley & Constanza, Citation2010; Kaczan et al., Citation2013). The PES concept varies widely, from the narrow definition of Wunder (Citation2005) that ‘PES is a voluntary transaction where a well-defined ES (or land-use likely to secure that service) is being bought by a buyer from a provider, if and only if the provider secures ES provision (conditionality)’, to the broader concept of Muradian et al. (Citation2010) who defined PES as ‘a transfer of resources between social actors, which aims to create incentives to align individual and/or collective land use decisions with the social interest in the management of natural resources’. While Wunder’s definition of PES is strictly neoliberal (Büscher et al., Citation2014), implementation in developing countries deviates significantly from this definition (Fletcher & Breitling, Citation2012; Muradian et al., Citation2013; McElwee et al., Citation2014; Fletcher & Büscher, Citation2017). Indeed, most PES implementation are run by States, non-market, and often in the form of subsidies (Gómez-Baggethun et al., Citation2015). The neoliberalisation of biodiversity and ecosystem conservation is often critiqued for its ‘commodification of nature’ (Kopnina, Citation2017), narrowing human-nature relationship (Kolinjivadi et al., Citation2019), lack of marketability of ecosystem services (Landell-Mills & Porras, Citation2002), and ignorance of ecological, social, or spiritual values as separate from an income dimension (Kolinjivadi et al., Citation2014). Some suggest that government intervention, or even direct administration, is needed for PES to deal with complexity of natural resources management and ensure environmental function (Gao et al., Citation2020; Wang & Wolf, Citation2019). As a result, PES and local pre-existing systems in conservation and resources management are often combined into a hybridized structure (Fletcher & Breitling, Citation2012; Kaiser et al., Citation2021; McElwee et al., Citation2020).

Vietnam is an interesting case to see how ‘theoretical’ neoliberal conservation via PES breaches into a country, given its long history of socialism and command-and-control approach in forest governance. In 2010 a national policy on payment for forest ecosystem services (PFES) was initiated. Vietnam’s PFES takes the broad definition of PES wherein beneficiaries of the ES (e.g. hydropower companies) indirectly and obligatorily pay owners of the forest land that provide the ecosystem services. With the issuance of Decree 99/2011, the PFES policy is regarded as the nation’s only working PES mechanism (Do et al., Citation2018). Under Decree 99, ES users are hydropower enterprises, water supply companies, and eco-tourism businesses, while ES sellers/suppliers are forest owners who manage the forests, management boards of protected and special-use forests, individuals, forest companies, and local organizations with forest land titles. However, most hydropower plants, water supply companies and tourism operators, although called ES users, only simply act as fee collectors or intermediaries that pass the fees from one party to the next (their customers who consume electricity, water and tourism services). Many authors including Pham et al. (Citation2013) and Phan (2019) found that most end users were not aware of the PFES payment part in their electricity and water bills, and information exchange between end users and their suppliers are very limited.

A fixed rate of PFES payment has been applied. At the time of this study, hydropower enterprises pay VND 20 (USD 0.001) per KWh for commercially-produced power, while water supply companies pay VND 40 (USD 0.002) per cubic metre of produced clean water, and eco-tourism businesses pay 1–2% of their revenue.Footnote1 All transactions are made through the Viet Nam Forest Development and Protection Fund (VNFF), the agency mandated to collect and distribute ES payments. In this indirect payment mechanism, any negotiation or contact between sellers and buyers is simply out of necessity. Despite being mentioned in Decrees 99/147/156, direct payment (implying voluntary PES) was never elaborated in policy documents (Do et al., Citation2018). For the Vietnamese government, the PFES program has helped in successfully raising over US$ 100 million annually for forest protection with proxy indicators on environmental performance such as decreased area of forest loss (McElwee et al., Citation2020). The PFES program has been criticized for its reverse decentralization of State’ forest governance (Suhardiman et al., Citation2013), avoidance of voluntary negotiations (Do et al., Citation2018; Kolinjivadi & Sunderland, Citation2012), largely excluding rightful beneficiaries (To & Dressler, Citation2019), and lack of conditionality and monitoring systems to report on outcomes (Pham et al., Citation2015). Nevertheless, few studies report on making the PFES more voluntary and performance-based (Do et al., Citation2018; McElwee et al., Citation2020; Nielsen et al., Citation2018; Simelton & Dam, Citation2014).

While we partly agree with some authors including Roth and Dressler (Citation2012), Suhardiman et al. (Citation2013), and McElwee et al. (Citation2020) that the non-neoliberal parts of PFES are influenced by a history of socialist development, we believe that neoliberalisation is a process, not an outcome, since any governmentality must be continuously reproduced or re-enacted (Kolinjivadi et al., Citation2019), and thus PFES can be improved towards more fair, market-oriented scheme without being completely neoliberal (Kaczan et al., Citation2013). Our study does not aim to engage in the endless neoliberal versus non-neoliberal debates, but rather on generating empirical evidence for negotiating a voluntary, performance-based PES, which policy-makers can use to improve the existing PFES program. It contextualizes a hypothetical PES scheme wherein current PFES users may want to further secure ES supply by paying extra amount to upland communities who may want to adopt sustainable land use practices with conditional incentives – and, unlike the PFES, the hypothetical scheme involves direct and voluntary transactions. Our study complements existing PFES literature because (1) we employed contingent valuation (CV) and choice experiment (CE) to quantify buyers’ and suppliers’ preferences for a PES design, not just to value ES; and (2) we expanded the scope of PES to include sustainable land use practices (e.g. agroforestry) outside natural forests that have already been covered by PFES, thus avoiding overlap while still promoting income generation and ES delivery by farmers.

Materials and methods

Study sites

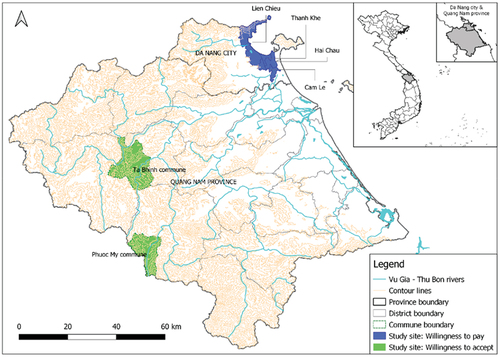

WTA study site – phuoc my and ta bhinh communes, quang nam province

Phuoc My and Ta Bhinh communes are located in the buffer zone of Song Thanh Natural Reserve (STNR) in Quang Nam province (). The two communes lie in the valley of Central Anamite range. Agricultural land in the two communes were small compared to total land (<3% in Phuoc My and <16% in Ta Bhinh). Phuoc My had 1,590 people belonging to the Gie Trieng (Bhnong), Kinh, Tay, Nung, Co Tu ethnic groups (2014 statistics). Ta Bhing had 2,438 residents, predominantly belonging to the Ca To ethnic group. In terms of socio-economic status, 50% of households in Phuoc My were poor, 24% near-poor and 26% non-poor, while in Ta Bhinh, the figures were 64%, 18% and 18%, respectively (Catacutan et al., Citation2017).

Soil and water conservation technologies were rarely practiced in both communes, resulting in moderate to severe soil erosion. Farming has been affected by drought, heavy rain and storm, flooding, landslide and soil erosion. Although restricted by STNR management authorities, agricultural expansion has ensued furtively.

The quality of natural forests has declined after years of overexploitation. Timber and NTFPs were depleted. Few farmers obtained benefits from their forests besides firewood, medicinal plants and mushroom. Farmers wanted to plant fast-growing trees for the pulp and paper industry. Households from several villages in Phuoc My earned income from the PFES program, while this was the case for only one village in Ta Bhing. Paddy and upland rice remain the main agricultural crops in both communes.

WTP study site – Da Nang city

With 1.1 million people, Da Nang is the sixth most populated city in Vietnam and had the highest urbanization ratio among provinces and municipalities in Vietnam. Around 87% of population live in urban areas with an average annual urban population growth of 3.5%.Footnote2

Da Nang city () has a total area of 1,285 km2, lying on the coast of the South China Sea and downstream of the Vu Gia-Thu Bon rivers.Footnote3 Water demand for millions of residents and tourists is projected at 500,000 m3/day by 2025 (Asian Development Bank, 2012). The main water source is Cau Do River, which relies on water from the Vu Gia River. Da Nang’s water supply has declined in recent years due to upstream forest destruction, low rainfall and hydropower operations. It is also suffering from salt-water intrusion and fresh-water shortage. Since Da Nang could not control the intake of water, and the flow of Vu Gia River has been unstable, it is urgent for residents to negotiate with upstream land holders in Quang Nam province to rehabilitate the Vu Gia watersheds.

Contingent valuation method to assess WTP

Contingent valuation method (CVM) is a widely used economic tool for measuring the maximum WTP of potential users for an environmental good or service (Wedgwood & Sansom, Citation2003). The tool relies on two key assumptions: (1) people have well-ordered, but concealed, preferences for all types of environmental goods; (2) people are capable of transforming preferences into monetary values (Hoevenagel, Citation1994). The method can include either open- or closed-ended questions. We used a close-ended CVM to estimate households’ WTP for improved management of watersheds in and around STNR. Four districts in Da Nang city were surveyed – Hai Chau, Cam Le, Lien Chieu, and Thanh Khe. Their populations benefit from Da Nang Water Supply Company and are therefore ES beneficiaries of STNR watersheds.

Sampling procedure and survey

Questionnaires were administered to 203 randomly selected households by trained CVM enumerators, consisting of six parts: (1) Study purpose; (2) Socio-demographic information; (3) Current water/electricity supply situation, consumption behaviors, awareness level, attitude towards nature; (4) Contingent valuation market scenario; (5) WTP (dichotomous choice); and (6) Alternative solutions.

Steps 4 and 5 were repeated twice – first to determine the WTP per unit of water, then again per unit of electricity. At the end of each WTP section, respondents could provide comments on their decision and suggest alternative solutions to shortages. Twenty HHs were pre-tested to gauge interviewees’ awareness about the watershed and to calibrate the final bid amounts.

Bid Amounts

A close-ended, dichotomous choice format was used to determine if respondents are willing to pay a certain amount (the starting bid) for improved management of Vu Gia river basin. For a ‘Yes’ response to the first bid, participants were offered a second higher bid while a lower bid is offered to a ‘No’ response. The final bid amounts were VND 10, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 170, and 300 per kWh of electricity, and VND 50, 70, 90, 110, 130, 150, 170 and 500 per m3 of water. The VND 300/kWh and VND 500/m3 bids were used to control for acquiescence response bias.

Data Analysis

SPSS was used to perform truncated tests at 5% significance level for correlations between respondents’ WTP and selected variables. Descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations between the percentage WTP and select variables were also conducted.

Discrete choice experiment (DCE) to assess WTA

Discrete choice experiment (DCE) belongs to a class of quantitative techniques that are based on stated preference (SP) – an individual’s preferences for ‘alternatives’ (whether goods, services, or courses of action) expressed in a survey context (Louviere et al., Citation2010). DCE is based on the random utility theory (RUT) proposed by Thurstone (Citation1927), which has been expanded to multiple comparisons (McFadden, Citation1986; Midway et al., Citation2020). This method has been widely applied in PES studies (Chaikaew et al., Citation2017; Kaczan et al., Citation2013; Khan et al., Citation2019). Using DCE in evaluating farmers’ WTA in the two selected communes was due to several reasons: (1) In the absence of a real-world situation, SP method is required; (2) in WTA application, DCE is less prone to bias than other stated choice methods (Burton, Citation2010); and (3) DCE is relatively simple and less likely to cause cognitive burden to respondents (particularly those with lower literacy).

Defining attributes and attribute levels

Prior to this study, we conducted a baseline study in the buffer zone of STNR and found agroforestry models (like intercropping and home gardens) that could maintain some degree of ecosystem functionality while allowing for agricultural production and income generation in the buffer zone. Such models can provide carbon sequestration services and biodiversity (above and below ground) comparable to regenerated forest, and contribute to better surface flow regulation (Catacutan et al., Citation2017). Although inferior to original forest, maintaining agroforests can offset forest cover loss. Yields and subsequent profits are estimated to be higher than those from baseline practices although there are investment requirements in both financial and management aspects (Catacutan et al., Citation2017). Regardless of the exact profit differences however, it is likely that long term maintenance of improved agroforestry requires providing farmers with additional incentives above the profits that are already associated with this farming method. The hypothetical PES program is focused on this goal: farmers would receive rewards (in cash and in kind) if they establish and maintain agroforestry plots that would help to generate ES benefits to downstream water and electricity users.

We initially identified relevant attributes to farmers’ decision and sustainable land use practices, including land area subscribed to the program, land use types, upfront payment amount, tree density, level of technical support, preferential loan provided, monitoring and reporting methods, contract duration, annual payment, individual/collective payment, fund management, farmers’ in-kind contribution, exit option, etc. A choice set was developed for field testing to narrow the choice experiments and define attributes that most influence farmers’ decision-making. Thirty farmers participated the pre-test wherein farmers preferred individual payment, while contract length held very marginal effect on their decision. Farmers also revealed concerns on their technical capacity during the test. Accordingly, we adjusted the attributes as shown in the final set in Annex 1.

Questionnaire development and design

Responses in a DCE can take on different formats including ‘pick-one’, ‘best-worse’, and others. We applied ‘pick-one’, as this is similar to real life decision making. A three-alternative design was adopted, wherein each choice set included three options for respondents to choose from. The alternatives in our DCE were unlabeled (Louviere et al., Citation2000) with generic titles (options A, B and C). A ‘none’ option (Status quo) was included to reflect unconditional demand and thus, ensure conceptual validity of the design given the voluntary nature of farmer participation in PES. Most upstream farmers were observed to have relatively low education level and unexposed to multiple-choice situations. To collect as much information without imposing the cognitive burden of answering many choice sets, nine choice sets were then used. These choice sets were introduced to farmers as a hypothetical PES program.

Survey administration

The survey took place in all villages of Phuoc My and Ta Bhing, involving 235 respondents. To facilitate communication in local languages, up to eight enumerators (i.e. forest rangers, commune officers) were employed in each meeting. Respondents’ information is given in below.

Table 1. DCE survey administration.

In each village, households were gathered in the ‘Guol’ – a village hall. The meetings started with questions about village land uses, followed by the introduction of the hypothetical PES program. Each household representative made his/her choices individually and answered exit questions with the help of enumerators.

Data analysis

Choice experiment design and data analysis were performed using SAS’s JMP Statistical Discovery software version 11.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Citation2013). The software used a special default bias-corrected maximum likelihood estimator described by Firth (Citation1993). The choice statistical model is expressed as:

Let X[k] represent a subject attribute design row, with intercept

Let Z[j] represent a choice attribute design row, without intercept

Then, the probability of a given choice for the k’th subject to the j’th choice of m choices is expressed in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) below:

where:

⊗ is the Kronecker row-wise product

the numerator calculates for the j’th alternative actually chosen

the denominator sums over the m choices presented to the subject for that trial

Results

Contingent valuation method – willingness to pay

Perceptions of the environment and awareness of watershed services

Questions around two variables of the New Ecological Paradigm, namely stewardship of nature and mastery of nature were used to gauge respondents’ vision of the relationship between humans and nature (Dunlap et al., Citation2000; de Groot et al., Citation2011). 86.7% of respondents strongly agreed that technological progress would enable humans to solve future environmental problems, illustrating why respondents were willing to invest in watershed management, and nearly all (95.1%) strongly agreed that humans are responsible for conserving the environment for future generations (). Nearly all respondents were aware of the connection between upstream watershed management and downstream water supply, and most were aware of STNR itself. Such high awareness is likely explained by respondents’ relatively high educational level (53% of respondents finished at least high school, 33% were university graduates, 5% had no formal schooling, and 9% chose not to reveal their educational level).

Table 2. Awareness and perceptions of respondents.

Majority of respondents felt their current utility supply is sufficient (85% and 84% for water and electricity, respectively). Yet, approximately 48% of respondents reported having water and/or electricity shortages in the last 6 months. This inconsistency is likely because the city’s water supply in current year was relatively stable compared to the intense rationing and alarm raised in previous years ().

Table 3. Respondents’ rating of water and electricity sufficiency and experience with shortage in the last 6 months.

WTP

Ten variables were tested for their association with Da Nang residents’ WTP. Water shortage experience and insufficient supply in the last 6 months and average monthly water consumption were linked to the residents’ higher WTP (), while electricity WTP was correlated with electricity shortage and average monthly water consumption (). With regard to electricity, respondents were willing to pay more if they had experienced electricity shortages in the past 6 months. Further cross-tabulations confirmed no significant associations between gender, age, level of education, or other variables in the residents’ WTP for water and electricity. For both water and electricity, the higher the respondent’s monthly consumption, the higher their WTP becomes. In this scenario, the level of consumption might be a proxy for income level – presence of higher disposable income could thus be linked to the residents’ WTP for watershed protection measures.

Table 4. Correlation analysis of variance for water WTP.

Table 5. Correlation analysis of variance for electricity WTP.

Sixty-four per cent of pooled respondents said they would be willing to pay a higher rate for water to improve upstream watershed management, whereas 56% were willing to pay higher electricity rates. Buyers were likely less willing to pay more for electricity than water because current electricity rates were perceived as already being too high (). Thirteen respondents said they were not willing to pay higher prices because they could not afford to, especially for electricity which is already too high. Interviewees also did not elicit a WTP because they doubted the effectiveness of the proposed watershed management solution or did not prefer the PES financing mechanism. Overall, buyers expressed that they would be more willing to pay if there will be better monitoring and reporting.

Table 6. Percentage distribution for Bid amounts of respondents who elicited WTP for water.

Table 7. Percentage distribution for Bid amounts of respondents who elicited WTP for electricity.

Of the respondents who elicited a WTP, the mean WTP was 113.24 VND/m3 and 98.07 VND/kWh for water and electricity, respectively (), which is a positive sign for exploring a voluntary PES mechanism.

Table 8. Mean truncated WTP of respondents (in VND) per unit of electricity and water.

Alternative solutions

The final part of the survey was an open-ended question about solutions to water shortage (). Sixteen respondents recommended improving supplier management (e.g. controlling corruption, increasing transparency), 12 posited technological solutions (e.g. solar power, water-efficient appliances), 11 suggested improving natural resources management (e.g. preventing illegal logging and improving forest management), and 3 proposed better end-user management (e.g. awareness raising).

Table 9. Alternative solutions to water and electricity shortages.

Discrete choice experiment – willingness to accept

General WTA

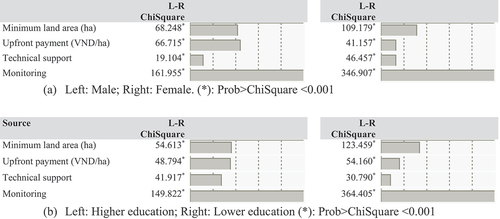

We employed the Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE) in determining the attributes that explain farmers’ utility (WTA) toward the hypothetical PES contract. The most significant attribute was monitoring level, followed by minimum land area, upfront payment, and technical support (). Predictably, both monitoring level and minimum land area negatively affected WTA wherein, an increase in the level of monitoring and land area requirement would decrease farmers’ WTA, while upfront payment and technical support showed positive impact, which means that an increase in these attributes would motivate farmers’ WTA (). All of the effects were significant.Footnote4 However, the impact of technical support was only marginal compared to other attributes, meaning that farmers’ WTA would only increase very slightly with more technical support (). The multinomial logit models of preferences for a hypothetical PES program is shown in Annex 2.

Figure 2. Effects of attributes on respondents: (a) relative magnitude of effects; (b) effect of each attribute on WTA; (c) marginal effects. source: author’s analysis.

The effects of changing the attribute levels were linear except for monitoring level (). Increasing upfront payment and technical support, or decreasing the minimum land area subscribed to the PES program elevated farmers’ WTA level proportionally. However, WTA dropped sharply with a change in the monitoring level from moderate to strict, while a change from low to moderate monitoring level did not significantly affect farmers’ WTA. Farmers WTA was 1.36 when all attributes are at minimum level, and changed to .97 and −.24 when the monitoring level changed to moderate and strict. The marginal effects of each attribute on farmers’ decision are shown in .

Site differences

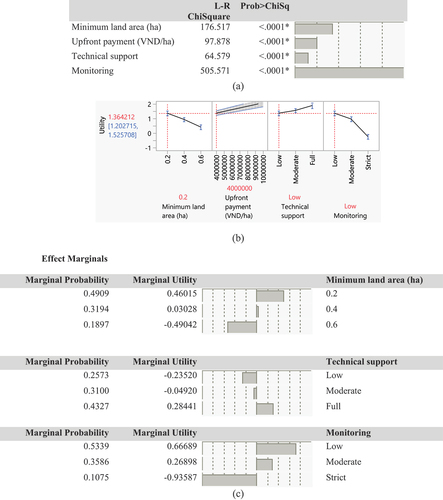

Given the very similar natural and socio-economic conditions of the two communes, heterogenetic impacts of attributes on respondents’ choice were not expected. We found that farmers in Phuoc My were more strongly motivated by technical support than in Ta Bhing (). This is likely because most of the respondents in Phuoc My have already been involved in the PFES program and may have realized the technical difficulties in implementing activities (Catacutan et al., Citation2017).

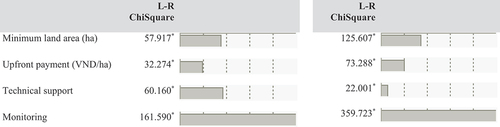

Gender and literacy differences

The most significant difference between gender groups was found in the upfront payment. The male group preferred a higher upfront payment, which corroborates with earlier findings of a REDD+/PES study in Bac Kan province wherein men were more cash-oriented than women (Eastman et al., Citation2013). The female group’s WTA was much more strongly influenced by monitoring level and minimum land area (). Female’s WTA decreased more sharply as land area or monitoring level increases. This result concurs with some behavioral economics studies concluding that women are psychologically more risk averse than men (Croson & Uri, Citation2009). In terms of literacy level, upfront payment and technical support had stronger effects on people who attended high school or above compared to those with lower education (). It is assumed that respondents with higher education (thus presumably higher literacy level and skills) had better cognitive ability (Barnes et al., Citation2004; Kravchenko, Citation2021), and therefore could realize the full picture of the hypothetical PES contract rather than focusing on one or two ‘perceived’ important factors.

Status quo

The status quo (SQ) or no-choice option is a scenario where no action is taken. Twenty-four people (10% of total respondents) had at least one SQ taken. The total number of SQ option taken was 60 (2.8%) from the total number of choices made. Only one person took SQ options in all nine choice sets given. This was not a protest response, but the person was observed to be unsure about his understanding of the hypothetical scenarios. His response is unlikely a reflection of his true WTA, but rather the result of avoidance of choice due to confusion or complexity (Barreiro-Hurle et al., Citation2018).

Discussions

Implications of WTP and WTA to PES participation and voluntariness

In terms of WTP, surveyed residents present a high degree of environmental awareness. The majority was willing to pay for improved watershed management; 64% were willing to pay more per m3 of water, and 56% were willing to pay more per kWh of electricity. Understandably, those willing to pay more have experienced recent shortages. Buyers may have been quicker to rate their electricity supply as sufficient because, compared to water, electricity was not rationed.

While respondents elicited a WTP through a surcharge on both water and electricity bills, it is advised that the PFES policy to be amended to allow inter-province negotiation on increasing buyers’ payments through their water bills only. This is because water supply can be directly traced from the catchment to the water supplier, then to consumers. For electricity, the water can only be traced from the catchment to the HPP supplier because electricity is distributed to different regions; hence, Da Nang City residents could not be assured of stable power supply by their regional HPPs, and the ES would leak to non-paying beneficiaries in other regions.

The high WTA of respondents in Phuoc My and Ta Bhing corroborates with other study results that cash payment is not always the most important factor for rural communities to adopt conservation and new farming practices (Adhikari & Boag, Citation2013; Costedoat et al., Citation2016; Lliso et al., Citation2022; Zanella et al., Citation2014). In many cases found in the literature, cash payment is less preferred, especially when the villages are poor and have limited market access (Hoynes & Schanzenbach, Citation2009; Nordén, Citation2014). In our study, the upfront investment per unit area (one ha), which is USD 200 ha-1 was sufficient to trigger participation when other factors were unfavorable. This amount was less than half of the establishment cost of an agroforestry plot, so it is possible that respondents either did not consider or had no idea about the establishment or opportunity costs involved. Another possibility is that the expected benefit from the investment was high, superseding the value of the input itself. However, a high WTA could also reflect rural communities’ tendency to say ‘yes’ to an external agent, although we tried to minimize this notion by being open about our intention.

We also found that preferences in the WTA were somewhat homogenous. Differences between gender, literacy, and commune existed, but were not significantly high to be categorized into discrete classes and treated differently. In other words, a voluntary PES program can be applied uniformly throughout the population of Phuoc My and Ta Bhing.

The main difference between our hypothetical PES scheme and the national PFES is that while participation in the latter is compliant, the former is voluntary. In PFES, ES users are ‘charged’ by the policy, while suppliers enjoy payments through labor contracts with legal forest holders (mostly State-owned forest entities). Some of the risks to PFES relate to motivational crowding out – for example, the way local people received daily wages (often representing instrumental values of ecosystem services) for forest patrolling could potentially undermine their willingness to protect forests for relational and intrinsic values and discourages sustainable land management activities that provide economic and ecological benefits. Consequently, they are considered passive participants in the PFES program, and had no role in decision-making (Hoang et al., Citation2021). It is evident that upstream-downstream payment programs that ignores relational and intrinsic values will likely have less participants and could even threaten those values by reducing access to traditional lands (Arias-Arévalo et al., Citation2017; Bremer et al., Citation2018; Lliso et al., Citation2022). This motivation crowding out effect is often a result of non-participatory, top-down approach, not aligned with personal development, elite capture, individual payments conservation tasks, and commodification, among others (Ezzine-de-Blas et al., Citation2019), and should be well considered in PES design and implementation. A voluntary approach makes the PES scheme more socially acceptable than the government’s regulatory approach (Kolinjivadi & Sunderland, Citation2012), and helps to avoid potential conflicts associated with mandatory regulations (Lindhjem & Mitani, Citation2012). Our case study presents a clear opportunity to engage stakeholders more actively in securing downstream water supply and developing agroforestry upstream through a PES scheme without creating an artificial ES demand through regulatory administration. It lends lessons and better understanding on designing tailor-fitted PES schemes that incentivize upland poor communities to adopt sustainable land use practices at a payment level that downstream buyers can readily afford, while local concerns are specified and addressed (Wang & Wolf, Citation2019).

Conditionality in context

While the neoliberal nature of PES is broadly contested, conditionality is considered the core feature that makes PES a novelty as opposed to command-and-control and other non-coercive conservation approaches (Kaczan et al., Citation2013; Sommerville et al., Citation2009; Wunder, Citation2015). In his revised PES definition, Wunder (Citation2015) emphasized conditionality as the single most important PES feature, while voluntariness can be a preserved criterion. Conditionality ensures payments can actually result in positive outcomes on landowners’ behavior and the ES (Sommerville et al., Citation2009). On this premise, Van Noordwijk and Leimona (Citation2010) identified four PES types with decreasing levels of conditionality (I–IV). Level I is where payment can be linked to actual improvement of ES, and IV is when farmers are evaluated against their commitments to implementing management plans favouring ES. Voluntariness of ES suppliers is arguably disproportional to conditionality: the higher level of conditionality, the heavier the burden on local land managers, and vice versa. Preferences of PES stakeholders, especially suppliers are therefore assumed to be heavily influenced by conditionality (Kaczan et al., Citation2013).

In our study, level of conditionality was found a limiting factor to participation of poor communities, conforming the studies of Van Noordwijk and Leimona (Citation2010), To et al. (Citation2012), Kaczan et al. (Citation2017), and L. Loft et al. (Citation2019). This is a fundamental challenge in developing a voluntary PES scheme wherein WTA was high at low monitoring level (low conditionality), while WTP varied from low to moderate if high conditionality was required. In general, farmers are likely to participate in a program that accounts for their actions but not the environmental outcomes because the latter is more difficult to comply (Kaczan et al., Citation2013). The strong effect of monitoring level to farmers’ WTA could be also explained by farmers’ skepticism towards a foreign land use (.e.g. agroforestry). Since respondents were unsure about outcomes, they wanted to try agroforestry in the smallest area possible first, to reduce the risk of failure or observe the benefits. We posit that if the communities have sufficient experience on sustainable land use practices e.g. agroforestry, their preferences would be less about ‘afraid of failure’ as reported in the literature (Costedoat et al., Citation2016). The impacts of low and medium level monitoring (representing conditionality in this case) were not much different. Therefore, a future PES scheme can employ a moderate monitoring level based more on trust amongst community members than physical inspection of compliance. Instead of a strict monitoring scheme, a high-level technical support can be provided to help farmers, especially poor farmers with low educational attainment to fulfil their contractual obligations.

Moving towards voluntary, pro-poor PES scheme that addresses both conditionality and voluntariness

The PFES policy appears to embody the notion of Compensation for Opportunity-Skipped (COS; Van Noordwijk & Leimona, Citation2010). However, the low payment rate failed to address the opportunity costs of unfriendly forest uses, especially forest land conversion to agriculture (Lan et al., Citation2016; Pham et al., Citation2015), and has undermined legitimacy and effectiveness. Even with increased payment, the current language, ‘payment’ would not likely halt timber and NTFP exploitation because forest dwellers are paid for ‘not doing harm’ (e.g. do not cut forest) rather than ‘actively doing good things’ (preserve and enhance the actual ES). The regulatory nature of PFES thus, inhibits participation (especially those without legal tenure rights) and information exchange between stakeholders. Participation in PFES is by default (as perceived) an obligation than an option, where information flow is lacking, awareness of rights and responsibilities are questionable, and non-participation in decision making is common (Lan et al., Citation2016; Le et al., Citation2016; Pham et al., Citation2016). The PFES was also criticized for poorly managed conditionality partly due to ineffective monitoring, reporting and verification (McElwee et al., Citation2020; Trieu et al., Citation2020).

Results from our WTP and WTA studies provide a basis to shift from the COS type of PES to a Co-investment in landscape-stewardship (CIS) – a pro-poor PES that aims at enhancing capacity and responsibilities of local communities in conjunction with external financial rewards to achieve desired economic and environmental goals in a stepwise manner: conditionality is enhanced through trust-building, giving attention to non-monetary rewards that enhance the providers’ capacity such as technical training, conditional land tenure, and involvement in decision-making (Lliso et al., Citation2022; Van Noordwijk & Leimona, Citation2010). This way of PES framing (stewardship) embraces both relational and (partly) instrumental values, is fairer (because it recognizes the multiple ways that various social actors perceive the environment values), is more likely to cause motivational crowding-in, and thus ensure sustainability of the payment (Arias-Arévalo et al., Citation2017; Lliso et al., Citation2022).

The CIS-PES offers opportunities to include multiple perspectives in managing agroforestry-mosaic landscapes, which have been neglected by policymakers and PES-buyers who consider ES-benefits primarily from forests only. Given the lower conditionality included, attention should be paid to build public trust in the management of upstream natural resources and ES providers. The government should also be attentive to balancing the needs of providers who are often poor communities, with the users’ desire to secure ES supply.

Our study provided evidence on how ES users and providers make choices around ES management. It also shows the potential of a pro-poor CIS-PES, which is a more socially acceptable way to manage the exchange of natural and financial capitals between two sides. Direct and voluntary payment was mentioned in Vietnam’s PFES policy but progress in this direction is slow. Our key argument is that although financial sustainability has been easily secured via the regulatory-oriented PFES where taxes and fees are main funding sources, public-private partnerships can also result in tailor-fitted, self-sustaining PES schemes through direct transactions between local stakeholders for the ES of utmost concern. Such opportunity for pro-poor CIS-PES can only emerge if the Government shifts its role from being a regulator (as in the current PFES) to an enabler, creating the conditions for voluntary PES schemes and facilitating their implementation. This approach will potentially make a headway in the transformation of PFES in Vietnam.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (67.7 KB)Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (Funding code: 3617 USAD-1177A.01CK 084VNM). We sincerely thank all of those who helped with and involved in the experiments and the two anonymous reviewers who commented on the earlier versions of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Mekong Region Land Governance project (MRLG). MRLG is a project of the Government of Switzerland, through the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), with co-financing from the Government of Germany and the Government of Luxembourg.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2022.2127953

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. These rates of payment are regulated in Decree 99/2010/ND-CP of the Government issued in 2010. By the end of 2018, the Government issued Decree 156/2018//ND-CP that regulates payment rates as VND 36 per KWh of electricity and VND 52 per cubic metre of produced clean water.

2. Da Nang | ESCAP (unescap.org)

3. ibid

4. i.e. probability > Chi-square is less than 0.001 for all attributes

References

- Adhikari, B., & Boag, G. (2013). Designing payments for ecosystem services schemes: Some considerations. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(1), 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2012.11.001

- Anderson, J., Gomez W, C., McCarney, G., Adamowicz, W., Chalifour, N., Weber, M., Elgie, S., & Howlett, M. (2010). Ecosystem service valuation, market-based instruments and sustainable forest management: A primer (pp. 25). State of Knowledge primer. Sustainable Forest Management Network.

- Arias-Arévalo, P., Martín-López, B., & Gómez-Baggethun, E. (2017). Exploring intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values for sustainable management of social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 22(4), 43. doi:10.5751/es-09812-220443

- Asia Development Bank. (2012). . Da Nang Water Supply Project - Initial environmental examination (Revised to include PFR2 Investment only) ADB PPTA No. 7144-VIE (Hanoi: ADB),Accessed 15 April 2022. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-document/73227/41456-033-vie-iee-04.pdf

- Barnes, D.E., Tager, I.B., Satariano, W.A., & Yaffe, K. (2004). The relationship between literacy and cognition in well-educated elders. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 59(4), M390–M395. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.4.M390

- Barreiro-Hurle, J., Espinosa-Goded, M., Martinez-Paz, J.M., & Perni, A. (2018). Choosing not to choose: A meta-analysis of status quo effects in environmental valuations using choice experiments. Economía Agraria Y Recursos Naturales - Agricultural and Resource Economics, 18(1), 79–109. 2174-7350 doi:10.7201/earn.2018.01.04

- Bigger, P., & Dempsey, J. (2018). Reflecting on neoliberal natures: An exchange. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 1(1–2), 25–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618776864

- Bremer, L.L., Brauman, K.A., Nelson, S., Prado, K.M., Wilburn, E., & Fiorini, A.C.O. (2018). Relational values in evaluations of upstream social outcomes of watershed payment for ecosystem services: A review. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35 , 1–8. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.024

- Burton, M. (2010). Inducing strategic bias and its implications for choice modelling design Research Reports 95062. Australian National University, Environmental Economics Research Hub. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.95062

- Büscher, B., Dressler, W., & Fletcher, R. (Eds.). (2014). Nature™ inc: Environmental conservation in the neoliberal age. University of Arizona Press.

- Catacutan, D.C., Do, T.H., Simelton, E., Hanh, V.T., Hoang, T.L., Patton, I., Hairiah, K., Le, T.T., van Noordwijk, M., & Nguyen, M.P. (2017). Assessment of the livelihoods and ecological conditions of bufferzone communes in song thanh national reserve, quang nam province, and phong dien natural reserve, thua thien hue province. World Agroforestry (ICRAF): Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Chaikaew, P., Hodges, A.W., & Grunwald, S. (2017). Estimating the value of ecosystem services in a mixed-use watershed: A choice experiment approach. Ecosystem Services, 23, 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.12.015

- Costedoat, S., Koetse, M., Corbera, E., & Ezzine-de-Blas, D. (2016). Cash only? Unveiling preferences for a PES contract through a choice experiment in Chiapas, Mexico. Land Use Policy, 58, 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.023

- Croson, R., & Uri, G. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.2.448

- de Groot, M., Martin, D., & de Groot, W. (2011). Public Visions of the Human/Nature Relationship and their Implications for Environmental Ethics. Environmental Ethics, 33, 25–44. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics20113314

- Do, T.H., Vu, T.P., Nguyen, V.T., & Catacutan, D. (2018). Payment for forest environmental services in Vietnam: An analysis of buyers’ perspectives and willingness. Ecosystem Services, 32, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.07.005

- Dunlap, R.E., Van Liere, K.D., Mertig, A.G., & Jones, R.E. (2000). New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00176

- Eastman, D., Catacutan, D.C., Do, T.H., Guarnaschelli, S., Dam, V.B., & Bishaw, B. (2013)). Stakeholder preferences over rewards for ecosystem services: Implications for a REDD+ benefit distribution system in Viet Nam. Working Paper 171. World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) Southeast Asia Regional Program. 17p. https://doi.org/10.5716/WP13057.PDF

- Ezzine-de-Blas, D., Corbera, E., & Lapeyre, R. (2019). Payments for environmental services and motivation crowding: Towards a conceptual framework. Ecological Economics, 156, 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.07.0

- Farley, J., & Constanza, R. (2010). Payments for ecosystem services: From local to global. Ecological Economics, 69(11), 2060–2068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.06.010

- Firth, D. (1993). Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika, 80(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/80.1.27

- Fletcher, R., & Breitling, J. (2012). Market mechanism or subsidy in disguise? Governing payment for environmental services in Costa Rica. Geoforum, 43(3), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.11.008

- Fletcher, R., & Büscher, B. (2017). The PES conceit: Revisiting the relationship between payments for environmental services and neoliberal conservation. Ecological Economics, 132, 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.11.00

- Gao, X., Xu, W., Hou, Y., & Ouyang, Z. (2020). Market-based instruments for ecosystem services: Framework and case study in Lishui City, China. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability, 6(1), 1835445. https://doi.org/10.1080/20964129.2020.1835445

- Gómez-Baggethun, E, Muradian, R., & Gómez-Baggethun, E. (2015). In markets we trust? Setting the boundaries of market-based instruments in ecosystem services governance. Ecological Economics, 117, 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.03.016

- Hoang, P.B.N., Takahiro, F., Iwanaga, S., & Sato, N. (2021). Participation of local people in the payment for forest environmental services program: A case study in central Vietnam. Sustainability, 13 (22), 1–13. MDPI https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212731

- Hoevenagel, R. 1994. An assessment of the contingent valuation method. in valuing the environment: methodological and measurement issues. Ed R. Pethig. 348. Valuing the Environment: Methodological and Measurement Issues. Springer Netherlands.

- Hoynes, H., & Schanzenbach, D.W. (2009). Consumption responses to in-kind transfers: Evidence from the introduction of the food stamp program. American Economic Journal. Applied Economics, 1(4), 109–139. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.1.4.109

- Kaczan, D., Pfaff, A., Rodriguez, L., & Shapiro-Garza, E. (2017). Increasing the impact of collective incentives in payments for ecosystem services. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 86, 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.07.011

- Kaczan, D., Swallow, B.M., & Adamowicz, W.L., (Vic). (2013). Designing a payments for ecosystem services (PES) program to reduce deforestation in Tanzania: An assessment of payment approaches. Ecological Economics, 95, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.07.011

- Kaiser, J., Haase, D., & Krueger, T. (2021). Payments for ecosystem services: A review of definitions, the role of spatial scales, and critique. Ecology and Society, 26(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12307-260212

- Khan, S.U., Khan, I., Zhao, M., Khan, A.A., & Ali, M.A.S. (2019). Valuation of ecosystem services using choice experiment with preference heterogeneity: A benefit transfer analysis across inland river basin. Science of the Total Environment, 679, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.049

- Kolinjivadi, V., Adamowski, J., & Kosoy, N. (2014). Recasting payments for ecosystem services (PES) in water resource management: A novel institutional approach. Ecosystem Services, 10, 144–154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.008

- Kolinjivadi, V.K., & Sunderland, T. (2012). A review of two payment schemes for watershed services from China and Vietnam: The interface of government control and PES theory. Ecology and Society, 17(4), 10. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-05057-170410

- Kolinjivadi, V., Van Hecken, G., Almeida, D.V., Dupras, J., & Kosoy, N. (2019). Neoliberal performatives and the ‘making’ of payments for ecosystem services (PES). Progress in Human Geography, 43(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517735707

- Kopnina, H. (2017). Commodification of natural resources and forest ecosystem services: Examining implications for forest protection. Environmental Conservation, 44(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892916000436

- Kravchenko, A.V. (2021). Information technologies, literacy, and cognitive development: An ecolinguistic view . Language Sciences, 84(2021), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2021.101368

- Lan, L.N, Wichelns, D., Florence, M., Chu, H., & Nguyen, P. (2016). Household opportunity costs of protecting and developing forest lands in Son La and Hoa Binh Provinces, Vietnam. International Journal of the Commons, 10(2), 902–928. http://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.620

- Lan, L.N., Wichelns, D., Milan, F., Hoanh, C., & Phuong, N. (2016). Household opportunity costs of protecting and developing forest lands in Son La And Hoa Binh Provinces, Vietnam. International Journal of the Commons, 10(2), 10.18352/ijc.620. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.620

- Le, N.D., Loft, L., Tjajadi, J.S., Pham, T.T., & Wong, G.Y. (2016). Being equitable is not always fair: An assessment of PFES implementation in dien bien, Vietnam. Working Paper 205. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR. https://doi.org/10.17528/cifor/006167

- Lliso, B., Arias-Arévalo, P., Maca-Millán, S., Engel, S., & Pascual, U. (2022). Motivational crowding effects in payments for ecosystem services: Exploring the role of instrumental and relational values. People and Nature, 4(2), 312–329. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10280

- Lindhjem, H. & Mitani, Y. (2012). Forest Owners’ Willingness to Accept Compensation for Voluntary Conservation: A Contingent Valuation Approach. Journal of Forest Economics, 18(4), 290–302. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2177598

- Loft, L., Gehrig, S., Le, D.N., & Rommel, J. (2019). Effectiveness and equity of payments for ecosystem services: real-effort experiments with Vietnamese land users. Land Use Policy, 86, 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.05.010

- Louviere, J.J., Flynn, T.N., & Carson, R.T. (2010). Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. Journal of Choice Modelling, 3(3), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70014-9

- Louviere, J.J., Flynn, T.N., & Carson, R.T. (2010). Discrete Choice Experiments Are Not Conjoint Analysis. Journal of Choice Modelling, 3(3), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70014-9

- McElwee, P., Bernhard, H., & Nguyen, T.H.V. (2020). Hybrid outcomes of payments for ecosystem services policies in Vietnam: Between theory and practice. Development and Change, 51(1), 253–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/DECH.12548

- McElwee, P., Nghiem, T., Le, H., Vu, H., & Tran, N. (2014). Payments for environmental services and contested neoliberalisation in developing countries: A case study from Vietnam. Journal of Rural Studies, 36, 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.08.003

- McFadden, D. (1986). The choice theory approach to market research. Marketing Science, 5(4), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.5.4.275

- Midway, S., Robertson, M., Flinn, S., & Kaller, M. (2020). Comparing multiple comparisons: Practical guidance for choosing the best multiple comparisons test. PeerJ, 8, e10387. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10387

- Mills, N., & Porras, I. (2002). Silver Bullet or Fools’ Gold? A Global Review of Markets for Forest Environmental Services and their Impact on the Poor. International Institute for Environment and Development. https://pubs.iied.org/9066iied

- Muradian, R., Arsel, M., Pellegrini, L., Adaman, F., Aguilar, B., Agarwal, B., Corbera, E., Ezzine de Blas, D., Farley, J., Froger, G., Garcia-Frapolli, E., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gowdy, J., Kosoy, N., Le Coq, J.F., Leroy, P., May, P., Méral, P., Mibielli, P. … Urama, K. (2013). Payments for ecosystem services and the fatal attraction of win-win solutions. Conservation Letters, 6(4), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263x.2012.00309.x

- Muradian, R., Corbera, E., Pascual, U., Kosoy, N., & May, P.H. (2010). Reconciling theory and practice: An alternative conceptual framework for understanding payments for environmental services. Ecological Economics, 69(6), 1202–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.006

- Nielsen, M.R., Theilade, I., Meilby, H., Nui, N.H., & Lam, N.T. (2018). Can PES and REDD+ match willingness to accept payments in contracts for reforestation and avoided forest degradation? The case of farmers in upland bac kan, Vietnam. Land Use Policy, 79, 822–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.09.010

- Nordén, A. 2014. Payment types and participation in payment for ecosystem services programs: Stated preferences of landowners. Working Papers in Economics No 591. School of Business, Economics and Law at University of Gothenburg. Göteborg, Sweden: https://hdl.handle.net/2077/35726

- Pham, T.T., Bennet, K., Vu, T.P., Brunner, J., Le, N.D., & Nguyen, D.T. (2013). Payments for forest environmental services in Vietnam: From policy to practice. In Occasional Paper (Vol. 93). Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 78.

- Pham, T.T., Loft, L., Bennett, K., Le, N.D., Brunner, J., & Vu, T.P. (2015). Monitoring and Evaluation of Payment for Forest Environmental Services in Vietnam: From Myth to Reality. Ecosystem Services, 16, 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.10.016

- Pham, T.T., Wong, G., Le, N.D., & Brockhaus, M. (2016). The distribution of payment for forest environmental services (PFES) in Vietnam: Research evidence to inform payment guidelines. Occasional paper, no. (163) , Center for International Forestry Research https://doi.org/10.17528/cifor/006297,

- Roth, R.J., & Dressler, W. (2012). Market-oriented conservation governance: The particularities of place. Geoforum, 43(3), 363–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.01.006

- SAS Institute Inc. (2013). JMP® 11 discovering JMP.

- Simelton, E., & Dam, V.B. (2014). Farmers in NE viet nam rank values of ecosystems from seven land uses. Ecosystem Services, 9, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.04.008

- Sommerville, M.M., Jones, J.P.G., & Milner-Gulland, E.J. (2009). A revised conceptual framework for payments for environmental services. Ecology and Society, 14 (2), 34. URL. https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art34/.

- Suhardiman, D., Wichelns, D., Lestrelin, G., & Thai Hoanh, C. (2013). Payments for ecosystem services in Vietnam: Market-based incentives or state control of resources? Ecosystem Services, 5, 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.06.001

- Thomas, A., & Theokritoff, E. (2021). Debt-for-climate swaps for small islands. Nature Climate Change, 11(11), 889–891. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01194-4

- Thurstone, L.L. (1927). A law of comparative judgement. Psychological Review, 34(4), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0070288

- To, X.P., & Dressler, W. (2019). Rethinking ‘Success’: The politics of payment for forest ecosystem services in Vietnam. Land Use Policy, 81, 582–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.010

- To, X.P., Dressler, W.H., Mahanty, S., Pham, T.T., & Zingerli, C. (2012). The prospects for payment for ecosystem services (PES) in Vietnam: A look at three payment schemes. Human Ecology, 40(2), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-012-9480-9

- Trieu, V.H., Pham, T.T., & Dao, T.L.C. (2020). Vietnam forestry development strategy: Implementation results for 2006–2020 and recommendations for the 2021–2030 strategy. In Occasional paper (Vol. 213). Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 68. https://doi.org/10.17528/cifor/007879

- Van Noordwijk, M., & Leimona, B. (2010). Principles for fairness and efficiency in enhancing environmental services in Asia: Payments, compensation or co-investment? Ecology and Society, 15(4), 17. (Accessed 12 June 2013) https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art17

- Wang, P., & Wolf, S.A. (2019). A targeted approach to payments for ecosystem services. Global Ecology and Conservation, 17, e00577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00577

- Wedgwood, A & Sansom, K. (2003). Willingness-to-pay surveys: A streamlined approach: Guidance notes for small town water services. WEDC

- Wunder, S. (2005). . Payments for environmental services: Some nuts and bolts CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 42 , (Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR)). https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/OccPapers/OP-42.pdf

- Wunder, S. (2015). Revisiting the concept of payments for environmental services. Ecological Economics, 117, 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.08.016

- Zanella, M.R, Schleyer, C., & Speelman, S. (2014). Why do farmers join payments for ecosystem services (PES) schemes? An assessment of PES water scheme participation in Brazil. Ecological Economics, 105, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.06.004