ABSTRACT

Changes linked to forest management institutions in diverse communities and cultural settings continue to attract research interest. However, comparative insights on their manifestations are lacking in Former British and Former French Cameroon. We trace the evolution of forest management institutions in the Kilum-Ijim and Santchou landscapes of Cameroon and analyse their compliance determinants, using key informant interviews (n = 12), focus group discussions (n = 6) and household surveys (n = 150). The results revealed a fairly stable culturally embedded institutional landscape in Kilum-Ijim, and a significant multiplication of structural institutions for Santchou. The logistic regression showed that perception and compliance with forest management institutions substantially depend on educational attainment, migration, membership in organisations, length of stay in the area and proximity of respondents to protected areas. The conclusion drawn is that landscapes which came under British colonial influence have fairly stable culturally embedded institutions, when compared to those that came under French influence. These site-specific traits shed light on the complexities linked to embedded institutions and their evolution. It further edifies theoretical perspectives on critical institutionalism. Studies on the source and content of the ‘last vestiges’ of these institutions are required.

1. Introduction

The advent of decentralized natural resource management saw the establishment of community-based forest management institutions. These institutions have significantly metamorphosed over the last few decades, leading to changes in the state of protected area management (Hersi & Kangalawe, Citation2016; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). Growing interest on the roles played by institutions in shaping the management of protected landscapes further indicates that the subject remains perennial in scientific circles (Friman, Citation2020). Within the emerging field of Critical Institutionalism, spatio-temporal evidence on the manifestations of culturally embedded institutions in diverse cultural settings of sub-Saharan Africa demonstrates lacunae (Friman, Citation2020; Ingram et al., Citation2015; J. N. Kimengsi & Balgah, Citation2021). The sustainable management of protected areas (especially forests) is critical as they serve as habitats to mankind and other organisms. Occupying about one-third of the global land cover, forests are not only home to a significant population of indigenous people and forest farmers, they also provide important services and goods necessary for overall socio-economic development (Pretzsch et al., Citation2014). Their important roles validate the need for protected area governance.

Protected area governance refers to the modus operandi by which protected areas are governed. This is shaped, to some extent, by the effectiveness of institutions (FAO, Citation2018). Institutions refer to humanly devised constraints (formal and informal) that structure societal interaction. They either enhance or constrain human actions while also playing a role in explaining institutional compliance (Kingston, Citation2019; North, Citation1990). Informal constraints are culturally linked and transcend several generations, while changes in formal rules are policy rooted. Formal institutions are represented by legal rules and sanctions (e.g. forestry policy and regulatory mechanism for effective forest governance), while informal institutions may assume dimensions such as social norms and networks devised and nurtured by community members (Bajracharya, 2008; Ngowo, Citation2014). While some institutions are exogenously rooted, a handful of others are endogenously sourced (Kimengsi et al., Citation2022a). The latter category, largely informal at community level, is virtually ignored by present day institutional structures (Buchenrieder & Balgah, Citation2013; Lambi et al., Citation2012). This virtual neglect has contributed to reinforce the countervailing force of endogenous institutions (Buchenrieder & Balgah, Citation2013). It can thus be said that while exogenous institutions assume legitimacy and dominance, their efficacy is usually countervailed by endogenous ones. The latter represents the culturally embedded institutional systems. This is one of the central focuses of critical institutionalism. Critical institutionalists theorize on the need to explore institutional complexity (especially culturally embedded ones) entwined in the everyday aspirations and choices of resource users. This suggests the need to fully understand the geography of institutions, i.e. what institutions are (composition), and how their manifestations play out differently on a spatio-temporal basis (Cleaver & de Koning, Citation2015; Kimengsi et al., Citation2021). A fertile laboratory to understand this is sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

As the most ethnically diverse region in the world, SSA represents a fertile ground to analyze the dynamics of community-based institutions. For instance, with an ethnic fractionalization score of 0.71, SSA surpasses the global average of 0.48 (Fearon, Citation2003). This diversity is a pointer to the diversity of informal institutions. Cameroon, as a case study in SSA, has an ethnic fractionalization score (0.89) which surpasses the average in SSA. In addition, the diversity of informal institutions and their countervailing effect (Buchenrieder & Balgah, Citation2013; Kimengsi et al., Citation2022b) further justifies why state-centred and more exogenous institutions have proven to be inefficient. There is a clarion call to potentially draw from informal institutions, in a bid to address current protected area management challenges (Osei-Tutu, Citation2017; Yeboah-Assiamah et al., Citation2019). This explains why there is an effort to explore the ‘last vestiges’ of informal institutions (Foli et al., Citation2018; Kimengsi et al., Citation2021). However, knowledge of where such institutions exist and their potentials are yet to be fully ascertained in the current dispensation, where institutional change processes have potentially led to the ‘rebirth’ of new institutions. This is pertinent for Cameroon which has been exposed to significant changes from the pre-colonial to post-colonial periods. The pre-colonial period in Cameroon dates as far back as the period before 1884 when communities managed their resources by drawing from informal institutional arrangements. The colonial period began in 1884 when Cameroon became a German Protectorate (Nuesiri, Citation2012; Sunseri, Citation2012) and extends to the period of French and British influence. Post-colonial Cameroon effectively began from 1961 when the British-ruled part of Cameroon joined the already independent French Cameroon. In both settings, protected areas exist – Santchou and Kilum Ijom – are classical examples.

Santchou protected area is situated in the part of Cameroon which came under French influence, while Kilum-Ijim is located in the part which came under British colonial influence. The approaches employed by Britain and France during their colonial administration have differentially shaped informal institutional arrangements in both natural resource settings (J. N. Kimengsi & Balgah, Citation2021). For close to a century and relative to other protected areas of Cameroon, these protected areas have a long history of endogenous (informal) and exogenous (formal) institutional influence. Therefore, assessing institutional change over space and time remains an issue of interest in these landscapes. With rising interest to understand changes linked to forest management institutions in diverse communities, comparative studies involving settings which came under both British and French influence are required. This paper contributes by analysing the role of endogenous cultural institutions in shaping forest management in the Kilum-Ijim and Santchou protected areas.

Santchou protected area is located in a cultural transition zone between the coastal environment and the human montane environment. Kilum-Ijim is located in a humid montane landscape with its unique traditional features. In terms of cultural intactness, Santchou is a melting pot of people from different cultures; this suggests a progressive dilution of her informal institutional arrangements. Kilum-Ijim is located in a remote humid montane landscape where the mix of cultures and potential dilution is minimal (J.N. Kimengsi & Moteka, Citation2018). Both study sites are grappling with different realities linked to increased pressure for settlement and agricultural expansion (for Santchou) and increased pressure for plantation establishment and cattle grazing (for Kilum-Ijim). This paper seeks to: (1) analyse the evolution of protected area management institutions from the pre-colonial, to the post-colonial periods. (2) assess the determinants of compliance with forest management institutions, and discuss the implications for future management of the landscape. The results contribute to provide further comprehensive evidence on the nature and functioning of these institutions and further inform critical institutionalist thinking.

2. Theoretical framework of critical Institutionalism

The new institutionalist approach considers the interaction of external factors (e.g. demographic, economic, technological and socio-political) as well as internal factors such as bargaining power and actor’s ideology in shaping the interaction between institutions and individuals. New institutionalism proves useful as it enhances our understanding of institutional change in the context of protected areas. Institutional change – the adjustments in institutional structures and processes (rules) have been the subject of much interest in the field of natural resource management – including protected areas (North, Citation1990; Greif and Laitin, 2004; Ostrom, Citation2005; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010; Cleaver, Citation2012; Haller, Citation2016; Wartmann et al., Citation2016). Such changes are shaped by myriads of forces including economic factors (e.g. market access), technological change, local leadership influence, and demographic changes (Ensminger, Citation1992; Haller, Citation2013). Irrespective of the magnitude of change, they translate to either efficient (Hagedorn, Citation2013; Hillman & Howitt, Citation2008) or inefficient resource management outcomes (Haller, Citation2016, Citation2013). Institutional change has been explored by different schools of thought, including Critical Institutionalists. As an emerging field in the broader institutional theoretical field, Critical Institutionalism (CI) strives to address the yet-to-be-filled gap between theories and ground realities (Cleaver, Citation2002). At the core of critical institutionalism is the need to understand the multiple reaction scenarios of culturally embedded institutions in the face of the introduction of new (exogenous) ones (Kimengsi et al., Citation2022a; J. N. Kimengsi & Balgah, Citation2021). This field underscores the need to unbundle the complexity of institutions entwined in everyday social life. As an evolving field, it continues to beg for significant empirical evidence from diverse contexts. To contribute to this knowledge base, an in-depth context-specific analysis of the ‘last vestiges’ of culturally embedded institutions is required. This will enable the framing of forward-looking questions that seek to uncover the complexities linked to the interaction between culturally embedded institutions and exogenously shaped ones.

3. Materials and methods

3.1 Study area

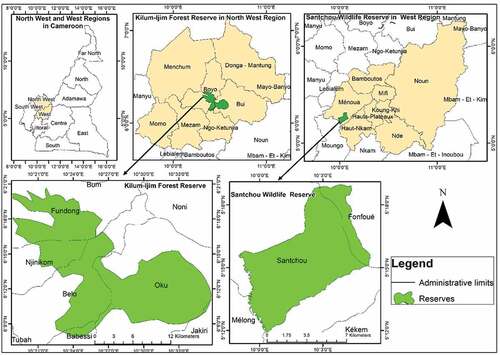

Cameroon has over 30 protected areas (Lambi et al., Citation2012); Kium-Ijim and Santchou protected areas constitute two of these. The contiguous Kilum-Ijim Landscape () is located in Bui and Boyo Divisions of Cameroon, covering an area of 20,000 ha, and containing unique flora and fauna (Cheek et al., Citation2004; FAO, Citation2002; Fogwe & Kwei, Citation2015). The Santchou landscape is located in the Menoua division of the West Region of Cameroon. It covers a surface area of 7,000 ha. It is rich in species such as dwarf elephants, dwarf buffalo and some endemic plants. While the Kilum-Ijim landscape came under British influence, the Santchou Landscape was influenced by the French.

Selection of study sites

Three communities per study site were selected for this study (). In both study sites, the communities were randomly selected from a list of communities which were judged to significantly depend on these protected areas for their livelihoods. In this case, the selection was informed by the interest and use of protected area resources by these communities. Additionally, and based on information provided by our gatekeepers, the three communities were significantly involved in the exercise of informal institutions. These communities have an estimated number of 655 households. From there, a sample of 150 households was drawn for the study which constitute 22.9%. The study began with the design of a key informant interview guide and a focus group discussion guide. The key informant interview guide consisted of 10 questions, while the focus group discussion (FGD) guide had 8 questions. The key informant interview guide consisted of questions on the history of the community, the key forest resources of interest, traditional institutions which existed in the past, the source of these institutions, the key traditional actors and events which transcend generations, beliefs, customs and taboos linked to forest resources, changes in terms of the structures and functions of institutions and their drivers. For the FGD guide, emphasis was placed on the source of traditional institutions, the resource potentials of the protected areas, the interactions and conflicts between traditional and state institutions, and the evolution of traditional institutions based on village history, including the possible forces responsible for such changes. A semi-structured questionnaire (N = 25) was designed for household data collection. Besides identifying aspects of institutional change, the questionnaire placed emphasis on rating the changes and compliance determinants with forest management institutions. The questionnaire also captured the implications for future management of these protected areas. To generate qualitative data, 12 key informant interviews were conducted. The key targets were traditional rulers, notables, aged persons in the community, youths and women. The aged persons and traditional authorities were targeted as it was judged that they would provide rich information on the history of their communities and on the respective protected area-linked institutions. Furthermore, women and youths were interviewed; while women shared their experiences on the historical evolution of certain cultural manifestations that prohibited their participation in the appropriation of certain resources, the youths shared their views with regard to changes in cultural practices and their future preferences.

Table 1. Selected villages in the target protected areas.

To further triangulate the data, we conducted six FGDs, three per study site. In each study site, a mixed group was constituted, followed by a male constituted FGD, and a female constituted one. The participants ranged from 10 to 12 members per FGD. Each FGD lasted for between 45 minutes and 1 h. The selection of participants per community was based on their involvement in forest-related activities and on their knowledge about institutional arrangements linked to the protected areas. It should also be noted that some key informants who were judged to have a mastery of the institutional set-up also constituted members of some of the FGDs. Considering the latent nature of institutions, qualitative approaches (key informant interviews and FGDs) were employed first to uncover salient aspects linked to the dynamics of institutions. Key informant interviews and FGDs have proved to be very useful in the analysis of the dynamics around socio-ecological systems (Ochieng et al., 2018; Haller, Citation2016). The design of the data collection instruments was performed in May and June 2020 and the first set of data were obtained between July and September 2020. Further complementary data were obtained in March 2021. In specific terms, key informant interviews and FGDs were conducted in both protected areas in July and August 2020. In September 2020, a questionnaire-based survey was performed in Santchou. Additionally, in March 2021, the survey was carried out in the Kilum-Ijim protected area. A total of 150 households were sampled using the random sampling and the snowball sampling techniques (). Random sampling was performed in Santchou. The selected villages in the Santchou landscape were visited for an ad-hoc household numbering to be performed. Then, raffle draws were repeatedly conducted to choose household numbers randomly. The houses chosen were numbered. This facilitated the location of the exact house for the questionnaire to be administered. This approach has been employed in previous studies related to forest resource use in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Gakou et al., Citation1994; Melaku et al., Citation2014). In the case of Santchou, the services of a translator who could communicate in French were sought. For Kilum-Ijim, the ongoing security challenge to access this area led to the adoption of the snowball sampling approach. Crisis-displaced persons were therefore targeted in Bamenda. They were visited during their village groupings. The respondents identified further led us to other respondents – in a snowball-like manner. Snowball sampling is a recommended tool which has been applied to collect data in very sensitive or crisis-ridden contexts (Libert Amico et al., Citation2020). Fieldnotes were used to record the data which was further elaborated upon and arranged thematically. The data was collected by the first and second authors, with the aid of research assistants.

Empirical model

The empirical analysis focuses on estimating the effect of individual/household socioeconomic and demographic factors on forest management institutional compliance and on the evolution perception in the Santchou landscape of Cameroon. The econometric equation for this relationship is specified as follows: The socio-demographic analysis suggests that 71% of the respondents are male, while up to 40% of the overall sample are migrants. The mean age of the individuals in the sample is 51 years with a standard deviation of 16.7. As expected, most of the individuals have completed only primary education (75%), compared to 25% with at least some secondary education. Quite a significant proportion of the respondents (80%) are involved or are actors in forest management; 69% are members of community-based institutional structures. The mean household size is 14 and on average, 45% of the individuals are involved in non-agricultural activities as their main occupation. Over 63% of the respondents reside less than 3 km from the protected areas and about 68% have lived in their communities for at least 5 years. An average of 68% is not surprising since over 40% of the sample are migrants ().

Table 2. Individual and household characteristics.

4. Results

4.1 Evolution of culturally embedded institutions

The evolution is discussed under three periods: the pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial periods. Emphasis is placed on the changes in the structures and functions of these institutions.

4.1.1 Pre-colonial culturally embedded institutions

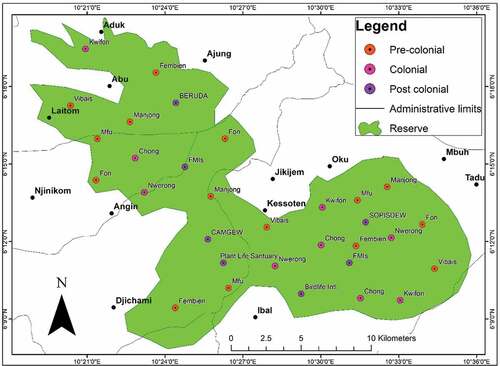

In both landscapes, the pre-colonial period was characterized by low population density and minimal forest exploitation. In the case of Kilum-Ijim, precolonial structures included the Bah Tie, Kwifon, and Manjong/Njong, among others (). These structures designed community-based rules of access, use and management of protected areas, and enforced them. For instance, the Manjong/Njong was charged with the task of fire tracing and control. Furthermore, they ensured that the Ankara farming system (characterized by burning) near the forest was prohibited. Besides enforcement, this structure carried out sensitization of the population against bush fires near the forest. Key processes (rules) include taboos such as the prohibition of people from accessing the Fon’s hunting ground and sacred forests, as well as the prohibition of women from killing anything in bloody form. This was also characterized by the respect for country Sundays.

Table 3. Pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial institutions in the Kilum-Ijim Landscape.

The Santchou landscape saw an array of structures such as traditional councils, cultural groups, secret societies and village management committees. These structures defined processes or rules (taboos, traditional beliefs, perceptions, norms, customs, and values) and enforced them. These rules are manifested in several ways. For instance, in the belief system, women were excluded from consuming certain products (especially animals). Animals such as hyena, rat mole, snake or antelope were forbidden – to avoid birth complications. An 89-year-old female respondent recounted this:

When we were very young, our mothers tolds us about this belief. We also witnessed cases were women died during child birth as a result of serious bleeding. Also, we have seen cases of prolonged labour which were attributed to their consumption of snake. These complications which sometimes lead to death were very common in the past and people believed it.

Besides enforcing beliefs and taboos, these structures contributed to preserving protected areas from the territorial expansionist tendencies of neighbouring communities ().

Table 4. Pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial institutions in the Santchou Landscape.

4.1.2 Colonial culturally embedded institutions

During the colonial period in Kilum-Ijim, very little change was observed in the composition of structures. This could be attributed to the fact that Kilum-Ijim came under the influence of the British Indirect rule, in which the British ruled the people through their traditional leaders and structures in place. It should be noted, however, that the functions diminished for some of these structures. For instance, the Manjong/Njong’s initial role was reduced to the execution of palace orders, and the sensitization of villagers on the need to manage the environment. This group hardly paid attention to bush fire protection interventions (). Regarding rules, additional rules such as the fact that night keeps in the forest were prohibited, sacred forests were used for ancestral rites and to enthrone fons, making them inaccessible for protected area exploitation, were emphasized (). Both structural and functional reductions of institutions were observed for Santchou. For instance, the number of sacred societies has reduced to five, with their key functions being the protection of the village from danger, and the creation of fear in the minds of people with regard to non-encroachment into sacred sites ().

Figure 2. Forest management institutional landscape of Kilum-Ijim (pre-colonial to post-colonial period)

An important institutional set-up in this landscape is the Abashi which plays an influential role in shaping the behaviour of most forest users. A focus group discussion respondent noted as follows:

Abashi is one of the most feared institution in Santchou. Although it came from the South West part of Cameroon, it has contributed to enforce most of the sanctions linked to land and forest resource use and community protection.

4.1.3 Post-Colonial culturally embedded institutions

Most of the structures which existed during the pre-colonial period were virtually maintained (). However, a remarkable adjustment could be observed for village committees. These committees were extended to cover most of the adjacent villages, and they were charged with forest protection responsibilities. These modifications improved upon the monitoring of protected areas. While most of the rules in the past are observable today, the extent to which they are enforced is yet to be clarified. However, there are some additions especially with regard to taboos. For instance, people are prohibited from stealing hives and animals (e.g. rat moles and other bush animals) from people’s traps in Kilum-Ijim.

This addition is linked to the growing demand for forest products which cause locals to further intensify their exploitation. Such intensification sometimes results in graziers encroaching and overgrazing the land, in the stealing of beehives, especially as Oku honey gained prominence in national markets – a signal of increasing demand. Also, the growing population meant more mouths to feed; this has orchestrated booty-theft from snares which was not the case in the past. A key informant interviewee recounted this as follows:

In the past it was impossible to even conceive the idea of animal theft in someones’s snare. Today there are few cases of that, since some people also traditionally guard their snares.

Post-colonial Santchou saw the multiplication of structures (). Institutions such as Abashi, malongei and other vigilante groups were introduced during this period. The Abashi ensures, among others, that the forestland is protected from external encroachment. Although it is not strictly crafted for protected area management, its role indirectly supports protected area management. Vigilante groups serve as monitors against illegal harvesting of timber and non-timber forest products. Rules relating to non-trespassing into sacred forests were applicable. Only members of structures such as Abashi and Nyampu were allowed to go there once in 2 years to perform cultural rights. With the multiplicity of structures and overlapping functions, it is clear that the division of institutional labour has not addressed the problem of protected area degradation problem. The belief that women should not consume certain animals is hardly respected since the early post-colonial periods.

4.2 Determinants of compliance and the evolution of forest management institutions

The compliance of forest management institutions in the Santchou and Kilum-Ijim landscapes is shaped by differential determinants. In addition, perception about the evolution of these institutions is differentiated by individual and household characteristics. In this section, we present an empirical analysis using a series of explanatory variables which explain compliance and people’s perception about the evolution of forest management institutions. The explanatory variables are physical (e.g. proximity to protected areas), social (e.g. education and household size) and economic (e.g. occupation) in nature. shows the descriptive statistics of the respondents. From the analysis, 60% of the respondents comply with forest management institutions and over 86% believe that these institutions have evolved over time.

The Student's t-test results suggest that, on average, the level of compliance is significantly higher among the male population, the more educated and non-farming individuals. Migrants are significantly less likely to comply, whereas those closer to the protected area, and those who lived in the area for at least 5 years are more likely to comply with forest management institutions. Those involved in forest management activities, community leaders and those who are members of community organisations are more likely to comply with these institutions. Regarding the perception towards the evolution of forest management institutions, males, the more educated and married individuals significantly held the view that these institutions have witnessed changes over the years. Members of community-based organisations, actors in forest management, those close to protected areas and those who have lived in the area for at least 5 years indicated that forest management institutions have evolved over the years ().

In , we report the odds ratios (OR) and standard error (SE) of the effects of individual socio-economic and demographic factors on the perception of the evolution and compliance with forest-based management institutions. The results show that individual characteristics substantially explain the level of compliance and perception on the evolution of forest management institutions. The results show that being male reduces the probability of compliance with forest-based management institutions (OR = 0.498, SE: 0.160) and being married reduces the probability (OR = 0.004, SE: 0.011). Individuals with at least secondary education substantially had a higher probability of compliance with institutions (OR = 1.452, SE: 0.851) relative to those who fall under the category less than secondary education. Migrants had a lower probability of compliance with forest-based institutions (OR = 0.133, SE: 0.197) compared to non-migrants. The probability of compliance with forest-based institutions is substantially higher among community leaders (OR = 2.449, SE: 0.084), and members of community organizations (OR = 2.805, SE: 0.369) relative to their counterparts. Residing less than 3 km away from the protected areas increases the probability of institutional compliance (OR = 4.899, SE: 0.966) and staying in such an area for more than 5 years equally increases the probability of compliance (OR = 1.082, SE: 0.135). Being in the non-farming sector increases the probability of compliance (OR = 1.241, SE: 0.320).

Table 5. Determinants of forest management institutional compliance and evolution.

Concerning the evolution of these institutions, the results show that the probability of perceiving changes in forest-based management institutions in the Santchou Landscape increased substantially for individuals with at least secondary education (OR = 1.114, SE: 0.163) and reduces (OR = 0.132, SE: 0.184) if the individual is married. The probability of perceiving changes in these institutions increased substantially (OR = 1.704, SE: 0.184) when the respondent is a migrant. Being a member of a community organisation was substantially associated with a higher probability (OR = 2.296, SE: 0.476) of perceiving changes in forest-based management institutions compared to those who were non-members. Residing less than 3 km from the protected areas and having lived in the community for more than 5 years were substantially associated with the perception of institutional evolution. Respondents who live less than 3 km away from the protected areas were associated with a higher probability of perceiving evolution in forest-based management institutions (OR = 7.520, SE: 0.581) compared to those who lived more than 3 km away from the area. Those who have lived in a community for more than 5 years were associated with a higher probability of perceiving changes in forest-based management institutions (OR = 1.081, SE: 0.121). Migrants were less likely to perceive an evolution in the forest management institutions (OR = 0.421, SE: 0.566) compared to non-migrants. The probability of perceiving the evolution in the institutions was higher among male individuals (OR = 1.080, SE: 0.113) and those in community leadership (OR = 1.110, SE: 0.918) than their respective counterparts. A substantial evolution in the forest-based management institutions was perceived among those who were employed in the non-agricultural sectors (OR = 1.704, SE: 0.657).

Generally, the results suggest that being male, educational attainment, being a member of organisations, holding community leadership positions and living closer to protected areas are important determinants of compliance with forest-based management institutions, while age, being married, in-migration and length of stay in the area reduces compliance. Concerning the evolution of forest-based management institutions, age, education, occupation, community leadership, being a member of community organizations and proximity to the reserve increased the probability to perceive the evolution of forest-based institutions. Considering the snow-balling approach employed in data generation for Kilum-Ijim, we judged to focus our analysis more from a qualitative spectrum in this case. However, further studies will potentially capture quantitative data for analysis.

5. Discussion

This paper sought to analyze the evolution of institutions in two ethnically diverse protected landscapes in Cameroon – the Kilum-Ijim and Santchou Landscapes. Based on the evolution of institutions, we observed a fairly stable culturally embedded institutional landscape for Kilum-Ijim, with a few adjustments linked to the extension of the arms of village committees, and the enforcement of some taboos. This could be attributed to the dominance of strong and highly centralized traditional systems in the western highlands. Furthermore, the colonial history of the western highlands (to which the Kilum-Ijim landscape belongs) was shaped by the British indirect rule which gave significant powers to traditional authorities (Nuesiri, Citation2012; Angwafo et al., Citation2016; J. N. Kimengsi & Balgah, Citation2021). This traditional set-up is still fairly strong today as it continually defines the socio-cultural life of the people. As recounted by an elderly respondent in the Kilum-Ijim area:

We have a strong attachment to our customs and tradition. Even the kwifon and other traditional institutions depend on the forest and its resources to carryout certain practices. This makes the Kilum-Ijim forest an important site for the communities.

This position validates the existence of fairly stable traditional institutional arrangements in parts of sub-Saharan Africa which were formerly colonized by Britain. In parts of East Africa, local forest management saw the domination of traditional leadership. While this may work well for some areas, it did not in this case, as leaders modify rules to meet their individual interests (Mohammed & Inoue, Citation2012).

In the case of Santchou, there was a significant multiplication of structures, accompanied by the limited compliance with rules, and overlapping institutional functions. A female respondent from Mokot village recounted as follows:

Today, many structures and organs have emerged, all of them struggling to exercise power and authority. The problem is that most of the leaders in these structures, including some of the chiefs do not work for the interest of the community. For this reason, people hardly respect their decisions and judgements.

This fairly loose system which could be linked to the French colonial rule of assimilation (Kimengsi et al., Citation2021b), has contributed to reshape and make less effective the enforcement of culturally embedded institutions. This evidence holds true for other French West African countries. For instance, in Senegal, informal institutional arrangements which were established to control natural resource production and trade (e.g. charcoal) witnessed a significant transformation in favour of the needs of commercial and non-local (urban consumer) people (Post & Snel, Citation2003).

The results suggest that educational attainment, membership in community-based institutions, length of stay in the area and proximity to protected areas positively determine both forest management institutional compliance and the perception of institutional evolution. Compliance is substantially higher among the male population. Furthermore, migrants substantially reduce the probability of compliance, whereas proximity to protected areas and length of stay (5+ years) positively determine compliance with forest management institutions. In parts of Ethiopia, proximity to forest resources significantly determined the capacity of resource users to effectively adhere to forest management rules (Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). This aspect does not hold true for parts of Zimbabwe, where resource scarcity and infrastructural development precipitated non-compliance (Mupangwa et al., Citation2017).

With increased access to education, household members do not comply due to fear of the institutional provisions. They are, however, motivated to comply due to their understanding of the need to preserve parts of the forest. As explained by an educated respondent in Kilum-Ijim:

We have been educated on the need to sustainably manage our resources. The numerous international NGOs which have intervened in this landscape have also explained these to us. To me, protecting the forest resources and controlling its use is something that every member of our community must respect.

Logically, those who have lived in these communities for long understand their tradition. Furthermore, the length of stay in the community positively predicts compliance, indicating that older residents are more likely to comply with culturally embedded rules than their relatively newer counterparts. This is justified by the fact that older residents have deeper knowledge on the functioning of these institutions, including the possible sanctions/repercussions linked to non-compliance. It is also likely that they might have experienced such sanctions in the past and would never wish to fall victim. In the context of Burkina Faso, the age of community members significantly determined their level of compliance with forest resource access and use rules (Coulibaly-Lingani et al., Citation2009). This is opposed to findings from other parts of Cameroon where compliance with forest management institutions is negatively shaped by growing waves of Christianity and the changing perceptions of communities (Nkwi, Citation2017).

Migrants bring with them different cultures and ideas which sometimes differ from the values and systems in place. This explains why they negatively affect compliance. In parts of West Africa, migrants were not able to evade compliance with institutional arrangements, as forest management institutions (forest laws and customary rules and regulations) prevented them from significantly accessing forest resources (Coulibaly-Lingani et al., Citation2009). Households which were closer to protected areas found it incumbent on them to work towards regulating access and use of forest resources. However, gender, occupation and community leadership are also important determinants of compliance. Varied compliance determinants have been reported across SSA. For instance, in Ghana, timber-related income irregularity and inadequate farmer support compromised protected area management (Acheampong et al., Citation2016). In the case of joint forest management in the Shagayu forest reserve of Tanzania, natural factors such as ecological preservation were key determinants (Mbwambo et al., Citation2012). In Ethiopia, a mix of formal and informal structures constitute key enforcement agents of institutions – this enhanced compliance (Fischer et al., Citation2014). The results equally resonate with similar findings in Burkina Faso and Tanzania and were social factors such as modernization, age and ethnicity-shaped institutional compliance (Coulibaly-Lingani et al., Citation2009; Hersi & Kangalawe, Citation2016). On the issue of proximity to protected areas, the results agree with the findings of Tesfaye et al. (Citation2012) that location of forest resources was the major geographic factor that influences compliance with forest management institutions.

As a contribution to the field of critical institutionalism, this paper reveals that even in fairly stable culturally embedded institutional arrangements (such as in Kilum-Ijim), resource users tend to react differently with regard to their adherence to established institutions. For instance, even with strong taboos and sanctions, people still defy these sanctions and steal animals from snares. This further confirms the position that people’s compliance with institutions is shaped by their everyday realities. Furthermore, even recently introduced institutions could exert dominant influence in certain cases. This process of aggregation is clear in the context of Santchou, where the Abashi which is only three decades old in the landscape has become very influential. The evidence provides new insights to support critical institutionalism with regard to the daily realities that shape compliance with institutions and the history of some institutional arrangements.

As a limitation to this paper, on-the-spot empirical evidence could not be gathered for Kilum Ijim, considering the ongoing crisis hitting the region which makes access to study sites impossible. While interviews were performed in Bamenda, involving displaced persons from communities around Kilum Ijim, we judged that the displacement might have possibly affected the quality of quantitative responses provided. For example, it is possible that during such village data collection, respondents might be better informed by their environment to provide accurate responses. On this score, we simply drew some qualitative insights for Kilum-Ijim and reported. Therefore, future studies involving quantitative surveys for Kilum Ijim are recommended at such a time, when the crisis in this area has been managed.

6. Conclusion

Geographical appraisals of institutional change in the context of protected area management are gaining traction in diverse cultural settings of sub-Saharan Africa such as Cameroon. We contribute to advance this evidence base, by comparatively analysing the evolution of protected area management institutions from the pre-colonial, to the post-colonial periods, and their compliance determinants. With these, we draw the following conclusions: Landscapes which were formerly shaped by British colonial influence have a strong likelihood of witnessing fairly stable culturally embedded institutions as is the case of the Kilum-Ijim. However, a few adjustments are observable even in such culturally intact landscapes. While this holds true, it might be important to fully explore other forces that might account for institutional stability in diverse contexts. Furthermore, in settings which came under French influence, more loose culturally embedded institutions could be observed, as in the case of Santchou. It, however, remains to be determined how other forces (e.g. the high level of cultural mix and migration) might have contributed to account for the looseness of such an institutional setup. Household income and length of stay positively predict compliance with culturally embedded rules linked to forest resource use. It is plausible to conclude that site-specific traits are useful in understanding the complexities linked to the evolution of culturally embedded institutions. The exploration of such site-specific considerations presents a useful platform to identify patterns of institutional behaviour over space and time. This ultimately informs our understanding of the everyday (re)production of institutional arrangements or the navigation against multiple rules – a useful step in advancing critical institutionalism. We call for further evidence to explore the source and content of these ‘institutional relicts’.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the respondents who were kind enough to participate during the focus group discussions and key informant interviews. We appreciate the reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions to improve this paper. This research complies with the standards required in data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acheampong, E., Insaidoo, T.F., & Ros-Tonen, M.A. (2016). Management of Ghana’s modified taungya system: Challenges and strategies for improvement. Agroforestry Systems, 90(4), 659–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-016-9946-7

- Angwafo, E.T., Billa, S.F., & Fotang, C. (2016). Contribution of traditional institutions to the sustainable management of sacred forests: Case study of Mankon sacred forests northwest region, Cameroon. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences, 9(4), 1–19. http://www.innspub.net

- Buchenrieder, G., & Balgah, R.A. (2013). Sustaining livelihoods around community forests. What is the potential contribution of wildlife domestication? The Journal of Modern African Studies, 51(1), 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X12000596

- Cheek, M., Pollard, B.J., Darbyshire, I., & Onana, J.M. (2004). Plants of kupe, mwanenguba and the bakossi mountains, Cameroon. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

- Cleaver, F. (2002). Reinventing institutions: Bricolage and social embeddedness of natural resource management. Eur. J. Dev. Res, 14(2), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/714000425

- Cleaver, F. (2012). Development through bricolage: Rethinking institutions for natural resource management. Routledge.

- Cleaver, F., & de Koning, J. (2015). Furthering critical institutionalism. Int. J. Commons, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.605

- Coulibaly-Lingani, P., Tigabu, M., Savadogo, P., Oden, P.-C., & Ouadba, J.-M. (2009). Determinants of access to forest products in southern Burkina Faso. Forest Policy and Economics, 11(7), 516–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2009.06.002

- Ensminger, J. (1992). Making a market. The institutional transformation of an African society. Cambridge University Press.

- Ensminger, J. (1997). Changing property rights: Reconciling formal and informal rights to land in Africa. In J.N. Drobak & J.V.C. Nye (Eds.), The frontiers of the new institutional economics (pp. 165–196). Academic Press.

- FAO. (2002). Case study of exemplary forest management in Central Africa: Community forest management at the Kilum-Ijim Mountain Forest Region. Rome, Italy: Forest Resources Division FAO.

- FAO. (2018). The state of the world’s forests 2018 – Forest pathways to sustainable development. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- Fearon, J.D. (2003). Ethnic structure and cultural diversity by country. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(June), 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024419522867

- Fischer, A., Wakjira, D.T., Weldesemaet, Y.T., & Ashenafi, Z.T. (2014). On the interplay of actors in the co-management of natural resources – A dynamic perspective. World Development, 64, 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.026

- Fogwe, Z.N., & Kwei, J. (2015). Cameroonian protected Kilium-Ijim forests for the development of Oku forest fringe community. J. of Env. Research and Management, 6(5), 293–303. https://www.e3journals.org/cms/articles/1450419913_Zephania%20and%20Jude.pdf

- Foli, S., Ros-Tonen, M.A.F., Reed, J., & Sunderland, T. (2018). Natural resource management schemes as entry points for integrated landscape approaches: evidence from Ghana and Burkina Faso. Environmental Management, 62(1), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0866-8

- Friman, J. (2020). Gendered woodcutting practices and institutional bricolage processes – The case of woodcutting permits in Burkina Faso. Forest Policy and Economics, 111, 102045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2019.102045

- Gakou, M., Force, J.E., & McLaughlin, W.J. (1994). Non-timber forest products in rural Mali: A study of villager use. Agroforest Syst, 28(3), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00704757

- Hagedorn, K. (2013). Natural resource management: The role of cooperative institutions and governance. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity, 2(1), 101–121. http://dx.doi.org/10.5947/jeod.2013.006

- Haller, T. (2013). The contested floodplain. Institutional change of the commons in the Kafue Flats. Lexington, Rowman & Littlefield.

- Haller, T. 2016. Water and Food – Africa in a Global Context Tauris. Pp369-397. The Nordic African Institute. I.B.

- Hersi, N.A., & Kangalawe, R.Y. (2016). Implication of participatory forest management on Duru-Haitemba and Ufiome Forest reserves and community livelihoods. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment, 8(8), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE2015.0550

- Hillman, M., & Howitt, R. (2008). Institutional change in natural resource management in New South Wales, Australia: Sustaining capacity and justice. Local Environment, 13(2), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830701581929

- Ingram, V., Ros-Tonen, M.A.F., & Dietz, T. (2015). A fine mess: Bricolaged forest governance in Cameroon. International Journal of the Commons, 9(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.516

- Kimengsi, J.N., Abam, C.E., & Forje, G.W. (2021). Spatio-temporal analysis of the ‘last vestiges’ of endogenous cultural institutions: Implications for Cameroon’s protected areas. GeoJournal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10517-z

- Kimengsi, J.N., & Balgah, R.A. (2021). Colonial hangover and institutional bricolage processes in forest use practices in Cameroon. Forest Policy and Economics, 125(2021), 102406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102406

- Kimengsi, J.N., & Moteka, P.N. (2018). Revisiting participatory forest management and community livelihoods in the Kilum-Ijim Montane forest landscape of Cameroon. Int. Journal of Global Sustainability, 2(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijgs.v2i1.12766

- Kimengsi, J.N., Mukong, A.K., Balgah, R.A., Pretzsch, J., & Kwei, J. (2019b). Households’ assets dynamics and ecotourism choices in the western highlands of Cameroon. Sustainability, 11(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071844

- Kimengsi, J.N., Mukong, A.K., Giessen, L., & Pretzsch, J. (2022b). Institutional dynamics and forest use practices in the Santchou Landscape of Cameroon. Environmental Science and Policy (128), 128, 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.11.010

- Kimengsi, J.N., Owusu, R., Djenontin, I.N.S., Pretzsch, J., Giessen, L., Buchenrieder, G., Pouliot, M., & Acosta, A.N. (2022a). What do we (not) know on forest management institutions in sub-Saharan Africa? A regional comparative review. Land Use Policy, 114, 105931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105931

- Kimengsi, J.N., Pretzsch, J., Mukong, A.K., & Ongolo, S. (2019a). Measuring livelihood diversification and forest conservation choices: insights from rural Cameroon. Forests, 10(81), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10020081

- Kingston, C. (2019). Institutional Change. In A. Marciano & R. G.b. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Law and Economics (pp. 1153–1161). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7753-2_259

- Lambi, C.M., Kimengsi, J.N., Kometa, C.G., & Tata, E.S. (2012). The management of protected areas and the sustenance of local livelihoods in Cameroon. Environment and Natural Resources Research (ENRR), 2(3), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.5539/enrr.v2n3p10

- Libert Amico, A., Ituarte-Lima, C., & Elmqvist, T. (2020). Learning from social–ecological crisis for legal resilience building: Multi-scale dynamics in the coffee rust epidemic. Sustain Sci, 15(2), 485–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00703-x

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (eds.). (2010). Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency and power. Cambridge University Press.

- Mbwambo, L., Eid, T., Malimbwi, R., Zahabu, E., Kajembe, G., & Luoga, E. (2012). Impact of decentralised forest management on forest resource conditions in Tanzania. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 21(2), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2012.698583

- Melaku, E., Ewnetu, Z., & Teketay, D. (2014). Non-timber forest products and household incomes in Bonga forest area, southwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Forestry Research, 25(1), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-014-0447-0

- Mohammed, A.J., & Inoue, M. (2012). Drawbacks of decentralized natural resource management: Experience from Chilimo Participatory Forest Management project, Ethiopia. Journal of Forest Research, 17(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10310-011-0270-9

- Mupangwa, W., Mutenje, M., Thierfelder, C., & Nyagumbo, I. (2017). Are conservation agriculture (CA) systems productive and profitable options for smallholder farmers in different agro-ecoregions of Zimbabwe? Renew Agric Food Syst, 32(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170516000041

- Ngowo, G.T. (2014). The role of formal and informal institutions in implementing REDD+ at local level in Rungwe District, Tanzania. In M.Sc., Management of Natural Resources for Sustainable Agriculture of Sokoine University of Agriculture Tanzania: Sokoine University of Agriculture. (pp. 121). https://www.suaire.sua.ac.tz/handle/123456789/1327

- Nkwi, W.G. (2017). The Sacred Forest and the Mythical Python: Ecology, Conservation, and Sustainability in Kom. 11(2), 31–47. http://www.onlineresearchjournals.com/aajoss/art/230.pd

- North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Nuesiri, E.O. (2012). The re-emergence of customary authority and its relation with local democratic government, RFGI Working Paper No. 6, CODESRIA

- Osei-Tutu, P. (2017). Taboos as informal institutions of local resource management in Ghana: Why they are complied with or not. Forest Policy and Economics, 85, 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.09.009

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton University Press.

- Post, J., & Snel, M. (2003). The impact of decentralised forest management on charcoal production practices in Eastern Senegal. Geoforum, 34(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(02)00034-9

- Pretzsch, J., Dietrich, D.H., & Eckhard, U. (2014). Forests and rural development. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. Institute of International Forestry and Forest Products Tharandt German. http://www.springer.com/series/5439

- Sunseri, T. (2012). Exploiting the “Urwald”: German post-colonial forestry in Poland and Central Africa, 1900-1960. Past & Present, 214(1), 305–342. https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtr034

- Tesfaye, Y., Roos, A., Campbell, B.J., & Bohlin, F. (2012). Factors associated with the performance of user groups in a participatory forest management around Dodola forest in the Bale mountains, Southern Ethiopia. The J. of Dev. Studies, 48(11), 1665–1682. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.714123

- Wartmann, F.M., Haller, T., & Backhaus, N. (2016). “Institutional shopping” for natural resource management in a protected area and indigenous territory in the Bolivian Amazon. Human Organization, 75(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.17730/1938-3525-75.3.218

- Yeboah-Assiamah, E., Muller, K., & Domfeh, K.A. (2019). Two sides of the same coin: formal and informal institutional synergy in a case study of wildlife governance in Ghana. Society & Natural Resources, 32(12), 1364–1382. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1647320