ABSTRACT

Introduction

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is the prototypical neutrophilic dermatosis, commonly associated with inflammatory bowel disease, with pulmonary involvement being the commonest extracutaneous manifestation. PG with tracheobronchial involvement may present as upper airway obstruction and can be life-threatening.

Areas covered

To evaluate the clinical characteristics and predictors of PG with pulmonary involvement, we reported a case of PG with tracheobronchial involvement in China, and performed a literature retrieval on PG with pulmonary involvement. Demographic data, clinical presentations, underlying diseases, radiological and histopathological findings, treatments, and clinical outcomes were collected and subjected to statistical analysis. Forty-seven cases (including ours) were identified. Diseases associated with PG with pulmonary involvement were similar. Clinical presentation of PG with pulmonary involvement was nonspecific, with cough and dyspnea being the most common clinical symptoms, and pulmonary infiltrates and cavitation being the most common radiological signs. Further univariate analysis suggested stridor and young age (p < 0.01) may be predictors of tracheobronchial involvement in PG.

Expert opinion

PG with tracheobronchial involvement can be life-threatening, with young age and stridor being possible predictors. Therefore, prompt airway assessment and management are required in younger patients with PG with pulmonary involvement presenting with stridor.

1. Introduction

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) belongs to a group of disorder called neutrophilic dermatoses, which is characterized by dermatological lesions with histology showing intense inflammatory infiltrates composed of mainly neutrophils [Citation1]. The pathophysiology and etiology of this skin condition are not well understood [Citation2]. The incidence of PG is estimated to be 3–10 cases per million population worldwide, with the peak incidence between 20 and 50 years old [Citation3,Citation4]. It is one of the common cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease [Citation5] and is also associated with a wide range of diseases including autoimmune disease such as rheumatoid arthritis [Citation4,Citation6], hematological malignancy, and rarely drugs such as cocaine and sunitinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) [Citation7,Citation8].

Classic PG is characterized by the presence of pustules developing into burrowing ulcers with violaceous edges typically occurring over the shins [Citation5]. However, extracutaneous manifestations are not uncommon, which can involve most of the organs in human, including the eye, brain, muscle, heart, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and spleen, with pulmonary involvement being the most common manifestation [Citation2,Citation9]. Diagnosis of PG is mainly made through the PARACELSUS score, which includes three major criteria, four minor criteria and three additional criteria as there is no specific histological changes or pathognomonic tests for definitive diagnosis of this disease [Citation10]. It would be more challenging in clinical setting if there is extracutaneous involvement of PG as it can mimic other diseases, especially opportunistic infections.

In this study, a case of PG with tracheobronchial involvement was reported. As our study demonstrated the severity of tracheobronchial disease, a review of current literature with statistical analysis was performed, so as to identify possible clinical characteristics that would predict such involvement in PG.

2. Case report

A 17-year-old boy was referred to our hospital as a result of fever for one week accompanied with nonproductive cough and wheezes for four days. He was previously diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease 4 years before this admission. Prednisolone and mesalazine were started since then, and he was followed up regularly at the clinic with his disease under control. The patient was a nonsmoker, and he had no history of pulmonary tuberculosis or contact history with patients with tuberculosis.

On physical examination, he was found to have a high-grade fever, oral aphthous ulcers, wheezes and multiple painful ulcerative skin lesions on the face and all extremities with brownish exudates. Initial investigation revealed leukocytosis with thrombocytosis, and normal liver and renal function tests. C-reactive protein (CRP) was 153 mg/L, with procalcitonin 0.18 ng/ml (Cutoff for sepsis < 0.5 ng/mL). Serum IgA, IgG, IgM, C3 and C4 were all within the normal range. Septic workup including blood culture, nasopharyngeal swab for respiratory virus, and serum for Mycoplasma pneumoniae antibody were negative except numerous white blood cells were detected by Gram stain of the pus from the lower extremity wound and bacterial culture of the pus showed scanty growth of Streptococcus mitis, Rothia species, Actinomyces odotolyticus, and Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Herpes simplex virus DNA was not detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the pus swab. Serostatuses of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and Treponema pallidum were all negative.

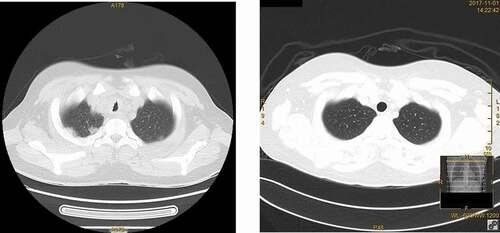

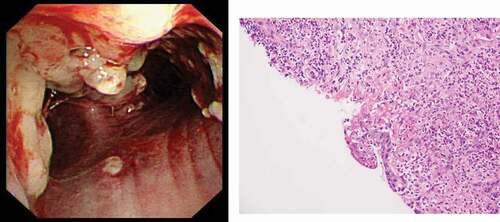

Computed tomography (CT) of thorax with contrast on admission showed multiple small scattered subpleural patchy infiltrates, and nodular mucosal lesions on the trachea, bronchi and right bronchioles ()). Bronchoscopy revealed multiple nodular mucosal lesions extending from the trachea to bronchi ()), with histological examination of tracheal lesion biopsy showing suppurative inflammation with squamous epithelial hyperplasia, but no definite granulomatous inflammation ()). No suspicious organisms were identified by Ziehl-Neelsen stain, periodic acid Schiff stain, and Grocott methenamine stain of the biopsy tissue. Bacterial culture of broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid only showed scanty growth of Streptococcus mitis. Mycobacterium tuberculous DNA was not detected by PCR from BAL.

Figure 1. Comparative Computed Tomography of Thorax (a) on presentation and (b) after treatment. Note the presence and resolution of mucosal irregularity over the trachea before and after treatment.

Figure 2. (a) Bronchoscopy finding of our case with pyoderma gangrenosum with tracheobronchial involvement. Note the presence of multiple whitish nodular lesions over the trachea together with erythema over the mucosa to suggestive of marked inflammation over the tracheobronchial area. (b) Subsequent biopsy with histology showing suppurative inflammation with marked neutrophil infiltration together with squamous epithelial hyperplasia. No definite granulomatous inflammation was seen in the biopsy.

Empirical antibiotics for community acquired pneumonia, inhaled corticosteroids, bronchodilators together with oral thalidomide and mesalazine were given, but the patient developed further clinical deterioration with stridor, increasing inspiratory and expiratory wheezes, decreasing oxygen saturation, together with further progression of ulcerations on the nasal bridge and all extremities. The largest lesion was on the right shin with a diameter of 4 cm, and had a sharp edge, with circumferential edema and erythema ().

Figure 3. Clinical photo of skin lesions on subsequent presentation. Presence of multiple burrowing ulcers with violaceous edges over right anterior shin, typical of pyoderma gangrenosum.

The patient was subsequently diagnosed to have PG with tracheobronchial involvement after consultation of the clinical microbiologist and rheumatologist 7 days later, according to two of the three major criteria including progressive course of disease and reddish-violaceous wound border, two of the four minor criteria including characteristically bizarre ulcer shape and extreme pain >4, and two of the three additional criteria including suppurative inflammation and systemic disease [Citation10]. He was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for respiratory support in view of possible clinical deterioration to complete upper airway obstruction. Adalimumab (a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonist) was started together with high-dose methylprednisolone, with subsequent defervescence and clinical improvement in both respiratory and dermatological condition. Parameters including white blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP were normalized after the above treatment. Reassessment CT Thorax two and half months later showed resolution of all mucosal lesions in the respiratory tract ()). During the subsequent 12 months, there was no relapse in terms of respiratory symptoms or skin condition. The patient is currently followed up regularly at the Rheumatology clinic.

3. Method

3.1. Literature search

Literature review was performed using the search terms ‘pulmonary, lung, respiratory, bronchopulmonary, tracheobronchial or bronchial’ and ‘pyoderma gangrenosum’ in PubMed. Only articles in English were included in the review unless the abstract or available translation was sufficient to obtain clinical information for analysis. Patients with concurrent anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) positive vasculitis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome), pulmonary tuberculosis, invasive mold infection (e.g. Aspergillus and Fusarium), acute respiratory distress syndrome, sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement secondary to inflammatory bowel disease such as chronic organizing pneumonia were excluded. Additional articles may be further included from the reference lists of the identified articles during the initial literature search.

We noticed a similar systemic review on pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement was published in 2018 [Citation11]. Our review followed the algorithm published and updated the review with new information in the past three years, at the same time analyzed the available data from the literature statistically to try to identify possible clinical predictors that allow us to alert to the possibility of tracheobronchial involvement.

3.2. Data extraction and assessment

Demographic data, initial clinical presentation, associated underlying diseases, radiological findings in CT/Chest X-ray, tissue biopsy results, treatment received together with clinical outcome were extracted from the available publications, and subjected to statistical analysis. Tracheal/bronchial involvement is defined as the presence of bronchoscopic findings of PG in the airway, biopsy showing neutrophilic infiltrates in the tracheobronchial mucosa or radiological finding of nodules in the airway. Categorical variables were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed by Mann Whitney U test using SPSS version 24.0. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

50 cases (from 47 literatures) of pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement were identified from our literature review [Citation12–58] (). After inclusion of our case, a total of 51 cases were included for statistical analysis.

Table 1. Summary of literature included in the systemic review

The majority of the patients were female, accounting for 27 out of 51 patients (52.9%) in our review, with age ranging from 4 months to 82 years old (median age 48 years old). The extracutaneous PG was associated with hematological disorders (23.5%, 12/51), inflammatory bowel disease (11.8%, 6/51) and autoimmune disease (9.8%, 5/51). Within hematological disorders, myelodysplastic syndrome (33.3%, 4/12) and IgA monoclonal gammopathy (33.3%, 4/12) were the most common, followed by myeloid leukemia (16.7%, 2/12), lymphoid leukemia (8.3%, 1/12), and plasma cell dyscrasia (8.3%, 1/12). Besides the above three major categories of associated disorders, 1 patient in our review had underlying hidradenitis suppurativa [Citation36], which was previously thought to be associated with PG. Another patient was also found to have T cell lymphopenia [Citation15], whereas the association with PG was less certain.

Initial clinical presentation of PG with pulmonary involvement was usually nonspecific. Cough (43.1%, 22/51) was the most common symptom, followed by dyspnea (27.5%, 14/51), chest pain (15.7%, 8/51), hemoptysis (9.8%, 5/51), constitutional symptoms (9.8%, 5/51), and stridor (7.8%, 4/51).

Concerning further investigation among the 51 patients included in this review, 46 patients (90.2%) received a CT of the thorax for further delineation of underlying pulmonary pathology. The most common radiological findings were pulmonary infiltrates (84.8%, 39/46), followed by cavitary lesions (39.1%, 18/46), pleural effusion (13.0%, 6/46), and consolidation (10.9%, 5/46). Other radiological findings included interstitial lung disease and interstitial pneumonia. Only 27 patients (52.9%, 27/51) received bronchoscopy or open/radiological guided lung biopsy for further confirmation of the diagnosis as well as exclusion of other similar etiologies. Neutrophil infiltration or inflammation (85.2%, 23/27) was a common finding in the histopathology of the respiratory specimen, with 2 patients (11.1%, 3/27) showing pulmonary fibrosis and 5 patients (22.2%, 6/27) showing granulomatous inflammation, and with negative bacterial and fungal staining excluding the possibility of opportunistic infection in these patients.

Majority of patients (96.1%, 49/51) also had co-existing dermatological involvement, except two patients with isolated respiratory involvement [Citation28,Citation58]. Other organ involved included the spleen (7.8%, 4/51), eye (3.9%, 2/51) and bone (3.9%, 2/51). Tracheobronchial involved of PG was present in 11 patients, and more than one third (36.4%, 4/11) of these patients presented with stridor on presentation. Further univariate analysis suggested that stridor (p < 0.01, by Fisher’s exact test) and young age (p < 0.01, by Mann Whitney U test) might be the predictors of tracheobronchial involvement, with the age range of patients without tracheobronchial involvement (14 months to 82 years old) higher than those with tracheobronchial involvement (4 months to 54 years old).

With the available information, systemic corticosteroid (85.7%, 42/49) was the mainstay of treatment, with occasional use of other immunosuppressants (36.7%, 18/49) and even targeted therapy (20.4%, 10/49), such as TNF alpha blockers (Infliximab, Adalimumab), proteasome inhibitors (Bortezomib) and Janus kinase inhibitors (Tofacitinib). 91.8% of patients (45/49) recovered with the resolution of clinical symptoms, skin lesions or progress imaging after treatment, however, 4 patients (8.2%) unfortunately deteriorated due to either poor response to treatment or underlying disease.

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

PG, as well as other conditions presenting with neutrophilic dermatoses, can be classified into neutrophilic disease, and almost every organ can be involved by neutrophilic inflammation [Citation11]. Although pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement is an unusual presentation of a rare disease, pulmonary involvement is the commonest extracutaneous manifestation of PG, with the age of patients and associated diseases (namely inflammatory bowel disease, hematological disorder together with autoimmune disease) similar to those reported in existing literature in classic PG [Citation3,Citation4].

However, the diagnosis of PG with pulmonary involvement is usually difficult. Firstly, the initial presenting symptoms of majority of the patients in our literature review were cough and dyspnea, which were nonspecific that clinicians might consider other more common differential diagnosis such as heart failure or pneumonia. Even if further imaging such as chest radiographs or CT of the thorax was ordered for these patients, the radiological findings could be so subtle that clinicians might not be aware of the possibility of PG with pulmonary involvement. Furthermore, patients may refuse invasive procedures such as bronchoscopy or open lung biopsy. It will be even more challenging as 4% of patients in our literature review presented with pyoderma gangrenosum with isolated pulmonary involvement. With the above reasons, although our literature search only yielded 51 cases, this number is likely an underestimation of the current situation.

In our case report, the treatment of PG with pulmonary involvement was delayed. One of the reasons is that the pulmonary radiological finding may mimic other pathology such as ANCA associated vasculitis, malignancy and pneumonia [Citation59], especially when PG is associated with diseases that are immunocompromising due to either the disease itself (hematological disorder) or the treatment received (inflammatory bowel disease and autoimmune disease). In addition to that, treatment of PG requires the use of high dose steroids and immunosuppressants. With the common radiological findings of pulmonary cavitation in patients with PG, physicians will be reluctant to start treatment early while awaiting further investigation to rule out opportunistic infection. To further complicate the picture, in our locality, Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is prevalent in South East Asia and well known to cause pulmonary cavitation [Citation60]. As patients with inflammatory bowel disease and autoimmune disease may receive TNF alpha blockers and patients with hematological diseases may have persistent neutropenia, these will increase the risk of acquiring Mycobacterium tuberculosis [Citation61].

Another important point demonstrated by our case report is that tracheobronchial involvement of PG could be life-threatening if the clinicians were not aware of this disease manifestation and treatment was not given promptly. In our case, the patient first presented to the hospital with normal oxygen saturation, however, as the treating clinician was not aware of the possibility of pulmonary involvement of PG, the patient was treated with multiple empirical antibiotics, which delayed the optimal treatment of the patient and caused the disease to further progress into upper airway obstruction. Our literature review demonstrated that stridor on presentation and young age were associated with tracheobronchial involvement, and the finding is compatible with previous evidence of stridor indicating a high likelihood of involvement of trachea [Citation62], therefore in a patient with suspected PG with pulmonary involvement, prompt airway assessment and treatment should be given to patients in younger age group.

Management of PG comprises of identification of associated underlying disease and immunomodulation by the use of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, including steroid-sparing agent such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, thalidomide, and dapsone, together with targeted therapy such as TNF alpha blockers and proteasome inhibitors. To date, there is still no clinical guideline for the treatment for patients with PG with pulmonary involvement. As the number of cases is limited, it is difficult to comment on the difference in the efficacy of different treatment combination, but at least the majority of patients receiving immunosuppressant responded to treatment.

5.2. Limitations

One of the limitations of our study is that the literature involved in our review are all in English. There are several literature and case reports in other languages such as Japanese and French, which were not included in our review. In addition, the above statistical analysis was based on the limited information available in the publications, whereas information not included in the literature was not able to be included in the statistical analysis. Furthermore, information such as ethnicity was unfortunately not available in most literature for further analysis, therefore the difference between the presentation of this disease entity in different ethnicity is still unknown.

6. Conclusion

In summary, pulmonary involvement is the most common extracutaneous presentation of PG, and it may mimic other disease entities such as opportunistic infection in terms of clinical presentations and radiological findings, especially in immunocompromising conditions that PG typically associates. Tracheobronchial involvement can present as upper airway obstruction and may be life-threatening. Young patients and stridor on presentation may suggest a higher likelihood of involvement of trachea/bronchus and require prompt airway assessment and management.

7. Expert opinion

Pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement is an unusual presentation of a rare disease. The nonspecific nature of initial presenting symptoms, radiological findings together with requirement of invasive procedures such as bronchoscopy and lung biopsy are the challenges of making the correct diagnosis. It is paramount for clinicians to be aware of the possibility of pulmonary involvement of pyoderma gangrenosum in younger population, as a delay in diagnosis without prompt treatment may result in life-threatening consequences. We believe that early involvement of dermatologists in patients presented with pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions may shorten the time from clinical presentation to arriving at the correct diagnosis. In order to guide non-dermatologists in diagnosing PG, useful and novel diagnostic algorithms should be designed and introduced in order to strengthen the awareness of clinicians on this clinical entity. Although currently such diagnostic algorithms are not yet available, scoring system approach based on underlying disease, age and extend of rash involvement may be helpful for clinicians in evaluation of the likelihood of the pulmonary involvement is due to pyoderma gangrenosum or not. Furthermore, PG with pulmonary involvement is still an entity that requires further investigation and study, as its relationship with other demographic factors such as ethnicity is not yet well understood.

To date, there is no practical guidelines for the optimal treatment of PG with pulmonary involvement, and the approach is mainly derived from small uncontrolled studies, clinical experience and expert opinion. From our case and literature review, systemic corticosteroids, the first-line therapy of PG with extensive or rapidly progressing disease, were prescribed for the patients as the mainstay of treatment. Steroid sparing agents such as cyclosporin can be an alternative regimen if patients are unable to tolerate systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Other second-line agents such as mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and methotrexate may be beneficial and have also been reported in the literature. With the advance in development of biologics, such as TNF alpha blockers, targeted therapeutic agents specifically targeting certain pathway are useful in reduction of the dosage and adverse effect of corticosteroids. However, due to the limited cases in the literature, it is difficult to ascertain the best treatment regimens for patients with PG with pulmonary involvement. Therefore, further researches such as case control study or randomized-controlled trial are necessary to determine the optimal treatment for this group of patients.

In addition to that, it should be emphasized that upper airway obstruction is a life-threatening complication of pyoderma gangrenosum, therefore early clinical suspicious of pyoderma gangrenosum, prompt initiation of appropriate treatment together with close monitoring of patient in intensive care unit are paramount to the clinical outcome of the patient.

Article highlights

Pulmonary involvement is an extracutaneous manifestation of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement is difficult for non-dermatologists due to the nonspecific symptoms, subtle radiological finding, and requirement of invasive procedures.

Delayed diagnosis of tracheobronchial involvement in pyoderma gangrenosum may be life-threatening.

Treatment for patients with pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement comprises of systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and targeted therapeutic agents.

Majority of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement responded to the current combination therapy, but further researches are required for determination of optimal therapy for this condition.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff at the Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infection Control, the Department of Pathology, The University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital, and Department of Microbiology, The University of Hong Kong for facilitation of the study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Prat L, Bouaziz JD, Wallach D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses as systemic diseases. Clin Dermatol. 2014 May-Jun;32(3):376–388. •• This paper provides a review of neutrophilic dermatoses together with different extrareview of neutrophilic dermatoses together with different extracutaneous manifestations of the disease

- Borda LJ, Wong LL, Marzano AV, et al. Extracutaneous involvement of pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol Res. 2019 Aug;311(6):425–434.

- Monari P, Moro R, Motolese A, et al. Epidemiology of pyoderma gangrenosum: results from an Italian prospective multicentre study. Int Wound J. 2018 Dec;15(6):875–879.

- Alavi A, French LE, Davis MD, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update on pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017 Jun;18(3):355–372.

- Annese V. A review of extraintestinal manifestations and complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2019 May-Aug;7(2):66–73.

- Bennett ML, Jackson JM, Jorizzo JL, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. A comparison of typical and atypical forms with an emphasis on time to remission. Case review of 86 patients from 2 institutions. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000 Jan;79(1):37–46.

- Wang JY, French LE, Shear NH, et al. Drug-induced pyoderma gangrenosum: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018 Feb;19(1):67–77.

- Akanay-Diesel S, Hoff NP, Kürle S, et al. Sunitinib induced pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcerations. Eur J Med Res. 2011 Nov 10;16(11):491–494.

- Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet. 1998 Feb 21;351(9102):581–585.

- Jockenhöfer F, Wollina U, Salva KA, et al. The PARACELSUS score: a novel diagnostic tool for pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Mar;180(3):615–620.

- Gupta AS, Greiling TM, Ortega-Loayza AG. A systematic review of pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement: clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 Jul;32(7):e295–e297.

- Xu P, Cai Y, Ying X, et al. A case of persistent fever, cutaneous manifestations and pulmonary and splenic nodules: clinical experience and a literature review. Intern Med J. 2019 Feb;49(2):247–251.

- Li X, Chandra S. A case of ulcerative colitis presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum and lung nodule. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014 Feb 17;4(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/jchimp.v4.23402.

- Marchiori E, Hochhegger B, Guimarães MD, et al. A cutaneous ulceration with pulmonary mass. Neth J Med. 2014 Apr;72(3):152–156.

- Brown TS, Marshall GS, Callen JP. Cavitating pulmonary infiltrate in an adolescent with pyoderma gangrenosum: a rarely recognized extracutaneous manifestation of a neutrophilic dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 Jul;43(1 Pt 1):108–112.

- Sartini A, Bianchini M, Schepis F, et al. Complete resolution of non-necrotizing lung granuloma and pyoderma gangrenosum after restorative proctocolectomy in a woman with severe ulcerative colitis and cytomegalovirus infection. Clin Case Rep. 2016 Jan 2;4(2):195–202.

- Bostan E, Günaydın SD, Karaduman A, et al. Excellent response to bortezomib in a patient with widespread ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum accompanied by pulmonary involvement and IgA monoclonal gammopathy. Int Wound J. 2019 Aug;16(4):1052–1054. • This paper describes the use of Bortezomib in management of pyoderma gangrenosum

- Mercer JM, Kuzel P, Mahmood MN, et al. Fatal case of vulvar pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement: case presentation and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014 Nov;18(6):424–429.

- Bittencourt Mde J, Soares LF, Lobato LS, et al. Multiple cavitary pulmonary nodules in association with pyoderma gangrenosum: case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2012 Mar-Apr;87(2):301–304.

- Be M, Cha HJ, Park C, et al. Multiple pulmonary cavitary nodules with pyoderma gangrenosum in patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Transl Med. 2016 Jan;4(2):39.

- Kasuga I, Yanagisawa N, Takeo C, et al. Multiple pulmonary nodules in association with pyoderma gangrenosum. Respir Med. 1997 Sep;91(8):493–495.

- Krüger S, Piroth W, Amo Takyi B, et al. Multiple aseptic pulmonary nodules with central necrosis in association with pyoderma gangrenosum. Chest. 2001 Mar;119(3):977–978.

- Allen CP, Hull J, Wilkison N, et al. Pediatric pyoderma gangrenosum with splenic and pulmonary involvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jul-Aug;30(4):497–499.

- Kitagawa KH, Grassi M. Primary pyoderma gangrenosum of the lungs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Nov;59(5 Suppl):S114–6.

- Gade M, Studstrup F, Andersen AK, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of pyoderma gangrenosum: 2 cases and a review of the literature. Respir Med. 2015 Apr;109(4):443–450.

- Chahine B, Chenivesse C, Tillie-Leblond I, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of pyoderma gangrenosum. Presse Med. 2007 Oct;36(10 Pt 1):1395–1398.

- Contreras-Verduzco FA, Espinosa-Padilla SE, Orozco-Covarrubias L, et al. Pulmonary nodules and nodular scleritis in a teenager with superficial granulomatous pyoderma gangrenosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan;35(1):e35–e38.

- Sakata KK, Penupolu S, Colby TV, et al. Pulmonary pyoderma gangrenosum without cutaneous manifestations. Clin Respir J. 2016 Jul;10(4):508–511.

- Matsumura Y, Nishiwaki F, Morita N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome followed by possible extracutaneous manifestations in the gallbladder, liver, bone and lung. J Dermatol. 2011 Nov;38(11):1102–1105.

- Scherlinger M, Guillet S, Doutre MS, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum with extensive pulmonary involvement. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Apr;31(4):e214–e216.

- Wang JL, Wang JB, Zhu YJ. Pyoderma gangrenosum with lung injury. Thorax. 1999 Oct;54(10):953–955.

- Vignon-Pennamen MD, Zelinsky-Gurung A, Janssen F, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement. Arch Dermatol. 1989 Sep;125(9):1239–1242.

- Fukuhara K, Urano Y, Kimura S, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum with rheumatoid arthritis and pulmonary aseptic abscess responding to treatment with dapsone. Br J Dermatol. 1998 Sep;139(3):556–558.

- Maritsi DN, Tavernaraki K, Vartzelis G. Pyoderma gangrenosum with systemic and pulmonary involvement in a toddler. Pediatr Int. 2015 Jun;57(3):505–506.

- Kanoh S, Kobayashi H, Sato K, et al. Tracheobronchial pulmonary disease associated with pyoderma gangrenosum. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Jun;84(6):555–557.

- Lebbé C, Moulonguet-Michau I, Perrin P, et al. Steroid-responsive pyoderma gangrenosum with vulvar and pulmonary involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct;27(4):623–625.

- Mlika RB, Riahi I, Fenniche S, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 21 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002 Feb;41(2):65–68.

- Batalla A, Pérez-Pedrosa A, García-Doval I, et al. Pioderma gangrenoso con afectación pulmonar: caso clínico y revisión de la literatura [Lung involvement in pyoderma gangrenosum: a case report and review of the literature]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011 Jun; 102(5): 373–377. Spanish

- Bhat M, Dawson D. Wheezes, blisters, bumps and runs: multisystem manifestations of a Crohn’s disease flare-up. Cmaj. 2007 Sep 25;177(7):715–718.

- Merke DP, Honig PJ, Potsic WP. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the skin and trachea in a 9-month-old boy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996 Apr;34(4):681–682.

- Deregnaucourt D, Buche S, Coopman S, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum avec localisations pulmonaires traité par infliximab [Pyoderma gangrenosum with lung involvement treated with infliximab]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2013 May; 140(5): 363–366. French

- Field S, Powell FC, Young V, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum manifesting as a cavitating lung lesion. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008 Jul;33(4):418–421.

- Rajan N, Das S, Taylor A, et al. Idiopathic infantile pyoderma gangrenosum with stridor responsive to infliximab. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Jan-Feb;26(1):65–69.

- Watanabe M, Natsuga K, Ota M, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Med. 2016 Feb;129(2):e17–8.

- Poiraud C, Gagey-Caron V, Barbarot S, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum cutanéomuqueux et systémique [cutaneous, mucosal and systemic pyoderma gangrenosum]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010 Mar; 137(3): 212–215. French

- Mirkamali A, Martha B, Dutronc Y, et al. Abcès pulmonaire et pyoderma gangrenosum [pulmonary abscess and pyoderma gangrenosum]. Med Mal Infect. 2007 Dec; 37(12): 835–839. French

- Takeuchi K, Kyoko H, Hachiya M, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the skin and respiratory tract in a 5-year-old girl. Eur J Pediatr. 2003 May;162(5):344–345.

- Sasaki T, Miura K, Kurokawa H, et al. [Interstitial pneumonia associated with pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporine A]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2003 Jan 10;92(1):146–148. Japanese

- Grattan CE, McCann BG, Lockwood CM. Pyoderma gangrenosum, polyarthritis and lung cysts with novel antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies to azurocidin. Br J Dermatol. 1998 Aug;139(2):352–353.

- Liu ZH, Lu XL, Fu MH, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement? Eur J Dermatol. 2008 Sep-Oct;18(5):583–585.

- Vignon-Pennamen MD, Wallach D. Cutaneous manifestations of neutrophilic disease. A study of seven cases. Dermatologica. 1991;183(4):255–264.

- Peters FP, Drent M, Verhaegh M, et al. Myelodysplasia presenting with pulmonary manifestations associated with neutrophilic dermatosis. Ann Hematol. 1998 Sep;77(3):135–138.

- Shands JW Jr, Flowers FP, Hill HM, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in a kindred. Precipitation by surgery or mild physical trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(5 Pt 1):931–934.

- Urano S, Kodama H, Kato K, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum with systemic involvement. J Dermatol. 1995 Jul;22(7):515–519.

- Kędzierska MA, Szmurło A, Szymańska E, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum with visceral involvement: a severe, recurrent disease affecting pulmonary, splenic, mesorectal, and subcutaneous tissues. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020;130(7–8):688–690.

- Gallou S, Madelaine J, Planchard G, et al. Atteinte pulmonaire de pyoderma gangrenosum: discussion diagnostique et thérapeutique à partir d’un cas et d’une revue ciblée de la littérature [lung involvement of pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic and therapeutic discussion based on a case report and a targeted literature review]. Rev Med Interne. 2021;42(10):734–739. • This paper describes the use of Tofactinib in management of pyoderma gangrenosum

- Hooton TA, Hanson JF, Olerud JE. Recalcitrant cutaneous pyoderma gangrenosum with pulmonary involvement resolved with treatment of underlying plasma cell dyscrasia. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;9:28–30.

- Arai S, Furukawa N, Takahama M, et al. Extracutaneous neutrophilic infiltration of the spleen and lung associated with pyoderma gangrenosum of the skin [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 14]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.15065.

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. From acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis to neutrophilic disease: forty years of clinical research. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Dec;55(6):1066–1071.

- Basnyat B, Caws M, Udwadia Z. Tuberculosis in South Asia: a tide in the affairs of men. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2018 Mar 22;13:10.

- Solovic I, Sester M, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. The risk of tuberculosis related to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapies: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J. 2010 Nov;36(5):1185–1206.

- Strong MS. Cough, dyspnea and stridor. Med Clin North Am. 1957 Sep;41(5):1255–1266.