ABSTRACT

Introduction

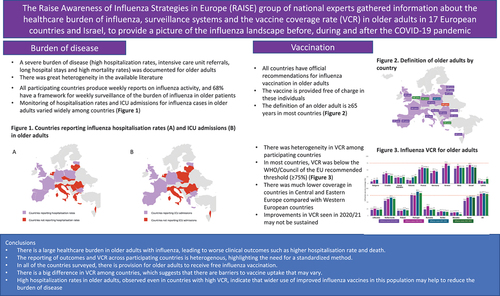

The Raise Awareness of Influenza Strategies in Europe (RAISE) group gathered information about the healthcare burden of influenza (hospitalizations, intensive care unit [ICU] admissions, and excess deaths), surveillance systems, and the vaccine coverage rate (VCR) in older adults in 18 European countries and Israel.

Areas covered

Published medical literature and official medical documentation on the influenza disease burden in the participating countries were reviewed from 2010/11 until the 2022/23 influenza seasons. Information on the framework for monitoring the disease burden and the provision for ensuring older adults had access to vaccination in their respective countries was provided. Data on influenza VCR in older adults were collected for the 2019/20 to 2022/23 influenza seasons. Data are reported descriptively.

Expert opinion

Influenza presents a significant healthcare burden in older adults. Reporting outcomes across participating countries is heterogeneous, highlighting the need for standardized approaches. Although older adults receive free influenza vaccination, vaccine uptake is highly variable among countries. Moreover, hospitalization rates remain high even in countries reporting a high VCR. Increased awareness and education on the burden of disease and the broader use of improved influenza vaccines for older adults may help reduce the disease burden on this population.

1. Introduction

While influenza and the common cold are both contagious viral respiratory tract illnesses [Citation1], influenza can be a serious disease that could lead to severe complications and unfavorable outcomes due to broader consequences [Citation2]. Some of these consequences include cardiovascular events, exacerbation of chronic underlying conditions, increased susceptibility to bacterial infections and functional decline, all of which may lead to an increased risk for hospitalization and death or profound disability in a substantial proportion of those affected [Citation3]. Furthermore, influenza can trigger secondary bacterial infections [Citation4], instigate a proinflammatory cytokine storm [Citation5] and exacerbate preexisting chronic medical conditions [Citation3], leading to severe complications, increased morbidity and mortality and increased use of antimicrobial agents, which is a key driver of antimicrobial resistance [Citation6].

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that annual influenza epidemics resulted in about 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness and about 290,000 to 650,000 deaths globally; thus, influenza is a significant global public health burden [Citation7]. Owing to the combination of COVID-associated lockdowns, national and international travel restrictions, and the use of other non-pharmacological mitigation measures [Citation8], there was a drop in reported influenza cases during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, after one season without influenza activity, the 2021/22 season was defined in many countries by two waves of influenza of moderate influenza activity separated by more than 4 weeks, both of which were due to the H3 influenza subtype. This gave rise to one of the longest periods of influenza epidemic activity in the past 40 years – an unprecedented situation in the recent history of influenza. Following a decline in influenza activity during the subsequent warmer months, the number of influenza cases in Europe, according to the WHO, during the 2022/23 season reached epidemic levels by November 2022 [Citation9], and the U.S.A. has seen the highest influenza hospitalization rates in a decade for the same season [Citation10]. Furthermore, surveillance data for the 2022/23 season show that several countries in the Southern hemisphere are experiencing higher or earlier flu activity than before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, activity varies by country and region [Citation11]. In both Europe and the U.S.A., the 2022/23 influenza season has persisted for an unprecedented length of time, up to March 2023, thus being the second abnormal flu seasonal epidemic in the post-acute COVID-19 pandemic period [Citation12,Citation13]. As a whole, the COVID-19 pandemic has reset the landscape for many of the main respiratory viruses.

In the 28 European Union countries between 2002–2011 (excluding the 2009/10 H1N1 influenza pandemic) using a two-stage modeling approach, there were an estimated 27,600 (range 16,200–39,000) respiratory deaths associated with seasonal influenza each winter (88% in people aged ≥65 years). Furthermore, the rates of mortality in the ≥65 years group were approximately 65 times higher compared with younger patients [Citation14].

Older patients are particularly at risk for infection, hospitalization and death due to influenza-related complications such as pneumonia [Citation15] and they bear the highest burden of influenza-related mortality of any age group [Citation16]. Recognition of these broader consequences of influenza virus infection is essential to determine the entire burden of influenza among different age groups, especially older adults, and to appreciate the value of preventive approaches such as vaccination.

High annual influenza vaccine coverage rates (VCRs) are considered crucial to reduce the disease burden, particularly in vulnerable populations such as the elderly. However, up to 2018 [Citation17,Citation18], great variation in VCRs across Europe were observed. Accordingly, the WHO/Council of the European Union set an influenza vaccination target of ≥ 75% in the elderly and other groups at high risk of serious illness, complications, and death [Citation17].

The Raise Awareness of Influenza Strategies in Europe (RAISE) group of national experts in 18 European countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain and the United Kingdom) and Israel gathered data on influenza VCRs before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, to ascertain if the pandemic led to an increase in VCRs. The RAISE expert group also gathered data on the disease burden and mapped the influenza surveillance systems and vaccine implementation tools, recommendations and settings in the respective countries. To our knowledge, this is the first endeavor to collate locally available data on vaccine coverage, the infrastructure for influenza monitoring in the contributing countries and the burden of influenza, and make it available in the global domain.

2. Methods

The RAISE experts in each of the countries were asked to provide citable data on the framework for monitoring the burden of disease in each of the contributing countries. These data related to the influenza surveillance systems, official recommendations for influenza vaccinations in older adults, and the vaccination implementation framework, all of which were mapped for each country using official and publicly available sources. Data on influenza VCRs in older adults were collected from the respective official national sources for the 2019/20, 2020/21, 2021/22, and 2022/23 (where available) influenza seasons in the 19 countries.

In addition, where available, the RAISE experts in each country were asked to provide evidence on severe influenza disease and its complications, including the incidence and severity in older adults, hospitalization and intensive care admissions and lengths of stays, hospitalizations due to respiratory and cardiovascular causes, and costs and economic burden. These data were collected from published medical literature and official medical documentation in the participating countries, starting from 2010/11 (after the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009/10), to provide a narrative overview of the influenza burden. The data were selected by the experts in each country.

All findings are reported descriptively.

3. Results

3.1. Vaccine coverage rates (VCRs)

Updated influenza VCRs in older people in Europe were collected from the 2019/2020 season (before the COVID-19 pandemic) up to the 2022/23 season (where available). The VCR in older adults was heterogeneous, ranging from 5.6% (in Slovakia during the 2022/23 season) to 88.3% (in Portugal during the 2021/22 season) (). Only two countries (Portugal and the UK) met the WHO/Council of the European Union target of ≥ 75% coverage for older adults [Citation17], in the 2019/20, 2021/22 and 2022/23 seasons in Portugal and the 2020/21, 2021/22 and 2022/23 seasons in the UK [Citation19].

Figure 1. Influenza vaccination coverage rates among older adults* in Europe, by country and influenza season (where data are available).

Improvements in coverage were seen in fifteen (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Israel, Lithuania, Netherlands, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain and UK) of the nineteen countries in 2020/21 (the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic). However, a decrease in VCRs was observed in the 2021/22 season in eleven of these countries (Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Israel, Lithuania, Romania, Serbia, and Spain) (). VCRs increased in the 2021/22 season in Bulgaria, Estonia, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and the UK compared with the previous season. There was a clear trend for much lower VCRs in countries in Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Serbia, and Slovakia) compared with Western European countries (). For those countries where the 2022/23 VCRs were available, all except Portugal and the UK were below the WHO target, and the trend persisted for countries in Eastern Europe to have lower VCRs compared with those in Western Europe ( ; ).

Table 1. Burden of disease monitoring framework.

3.2. The burden of disease in individual countries

Details of the source data on the disease burden for influenza-related complications (specifically GP visits, hospital and ICU admissions, and excess deaths) in each country are summarized in and described in more detail in the Supplementary Material. Owing to the heterogeneity of the data collected across the countries surveyed, these data are presented as a narrative overview (Supplementary Material) to provide more context to the reader of the results presented in this manuscript. A brief overview of the findings is presented below and in .

Table 2. Source data for burden of disease.

While vaccination is protective, the burden of influenza in older adults is an unmet medical need, as evidenced by the results of the studies/reviews. The literature analyzing the burden of influenza in the elderly across wider regions of Europe generally reflect the clear trend observed in individual European country reports – a high burden (reflected by influenza-related complications [GP visits, hospital and ICU admissions and mortality]) coupled with high vaccination rates in countries in Western Europe compared with low rates in countries in Central and Eastern Europe [Citation88,Citation137,Citation151], particularly in Poland [Citation129–132,Citation152–154].

This situation may have changed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic across Eastern Europe, as policies have been introduced to increase access to influenza vaccines in older adults in these regions as part of a cost-effective approach to reducing the burden of influenza [Citation88,Citation155]. However, based on the trends reported here, following the initial spike during the 2021/22 season coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, VCRs remain below the recommended level.

3.3. Burden of disease monitoring systems

To understand if significant differences in the countries would explain the high variability in VCRs, the influenza monitoring systems (influenza activity and case surveillance in older adults) and the vaccination implementation setting in each country were investigated ().

All countries have weekly reports on influenza activity (). Thirteen (68%) of the 19 countries have a weekly framework for national surveillance of influenza cases in older adults (). All countries produced an annual report at the end of each influenza season. The annual reports for nine countries included hospitalization rates in older adults, the annual reports for ten countries included ICU admissions for older adults, and the annual reports for 11 countries included all-cause excess deaths for older adults ().

Of interest, all countries have official recommendations in place for influenza vaccination in older adults. Thirteen of the countries surveyed defined older adults as being ≥65 years; in Estonia, Germany, Greece and Netherlands, the definition was ≥60 years; in Slovakia it was ≥59 years; and in Poland it was >55 years (). In all countries, the influenza vaccine was provided without charge to the vaccine for those designated as older adults at some point in the period investigated. In 12 of the 19 countries surveyed, there was a financial incentive for vaccinators to administer influenza vaccinations ().

4. Discussion

The results of the RAISE survey show that, although the overall influenza VCR slightly increased in most Western European countries after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, only two countries (Portugal and the UK) met the WHO/Council of the European Union target of ≥ 75% coverage in older adults. This is despite all countries having in place a defined framework for the monitoring and reporting of influenza activity and the delivery of universal vaccination for older adults. All the countries in the survey have weekly reports on influenza activity. However, these are not specific for influenza in older adults. Only thirteen of the 19 countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Italy, Israel, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain, and the UK) have a weekly framework for national surveillance of influenza cases in older adults. Fourteen countries have a framework for the reporting of extreme outcomes (either hospitalizations, ICU admissions, all-cause mortality, or combinations thereof) during an influenza season.

Older adults are particularly vulnerable following influenza infection [Citation156–160] and are at greater risk of serious complications from influenza than younger, healthy adults because their immune defenses are reduced with increasing age and comorbidities are common. Influenza can lead to primary viral or secondary bacterial pneumonia, serious cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction or stroke, and neurological complications in otherwise healthy older adults [Citation2]. In addition, influenza can also aggravate underlying chronic illnesses, such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and diabetes [Citation161], many of which have interconnected pathologies and are recognized as conditions that can lead to profound disability. Overall, age-related factors, such as underlying conditions and frailty, in conjunction with influenza in the vulnerable older population contribute to increased hospitalizations, reduced autonomy [Citation160] and increased mortality. Aging also leads to a decline in immune function (immunosenescence), which is associated with increased vulnerability to common infections and a decreased and more evanescent response to vaccination. Pertinently, as the proportion of elderly persons is growing, and because age and its associated immunosenescence, chronic diseases, and frailty are risk factors for severe influenza, the toll from influenza can only be expected to increase unless control measures are applied more vigorously [Citation162–164].

As shown here, the significant burden of influenza infection in older adults is an unmet medical need, with high hospitalization and mortality rates, even in countries with high VCRs. In light of this, it may be postulated that a VCR target of ≥ 75% may be insufficient with currently available influenza vaccines, and a target of 90% VCR in older adults, as is the case in the U.S.A. [Citation165], could be more appropriate. However, given the documented difficulties in increasing VCR, even in a favorable setting (i.e. the necessary recommendations and funding are in place), a focus on raising awareness and education on the burden of disease and broader usage of improved influenza vaccines for older adults could be considered as a complementary approach.

While the typical view of the burden of influenza considers the visible cases and outcomes (laboratory-confirmed cases seen by general practitioners, ICU or non-ICU hospitalizations, and deaths attributed to influenza), the true burden of influenza may be much larger and incorporate many ‘hidden’ elements (e.g. patients not seen by healthcare professionals or those seen by other healthcare services, hospitalizations and deaths triggered by influenza, complications triggered by influenza in at-risk patients, the disruption to the healthcare system and the increased use of antibiotics). In actuality, influenza represents a major disease burden: it had the highest burden among 31 infectious diseases from 2009–2013 and represented 30% of the disability-adjusted life year (DALY) burden of infectious disease in Europe when measured during this period [Citation166]. Moreover, the effects of complicated influenza are not confined to the respiratory system; it can involve other major organ systems with devastating complications, including heart attack and stroke [Citation167–170]. Another important social factor to consider in this regard is the global expansion of the elderly population, particularly in high-income countries such as those in the European Union. These factors add greater urgency to the current landscape reported and discussed in this article.

Overall, influenza is a vaccine-preventable disease, and annual influenza vaccination is the most effective method for prevention [Citation171–173]. Any protection conferred following vaccination should protect against influenza infection and the severe secondary complications of influenza that often require hospitalization and can result in death in older adults. All countries surveyed have in place official recommendations for the provision of free influenza vaccination to older adults or those with chronic conditions that place them at high risk of complications from influenza infection. However, for the most part, VCRs remain below the recommended threshold, with much lower rates reported in countries in Eastern Europe compared with those in Western Europe. Indeed, only two of the countries surveyed (Portugal and the UK) consistently exceeded the threshold VCR of ≥ 75% over the survey period, with both countries reporting VCRs in the region of 80% in the 2021/22 and 2022/23 seasons. The results for Portugal were in accord with the Vacinómetro® initiative (monitoring influenza vaccination rates amongst high-risk groups in Portugal), which showed an increased vaccination coverage rate in people aged ≥65 years, rising from 58.6% in 2008/09 to 76.0% in 2019/20, and meeting the WHO target for the elderly of ≥ 75% [Citation174]. In fact, real-time monitoring of influenza activity during a season has been crucial for monitoring a dynamic picture of the number of cases of influenza. For example, the Gripómetro telematic survey validated in Spain [Citation175], could anticipate deviations in flu vaccine coverage during the course of an influenza vaccination campaign, which could lead to the timely implementation of mitigating measures. Furthermore, the Research & Surveillance Centre of the Royal College of General Practitioners in England provides weekly information, and the UK National IT system in the participating general practitioners’ offices (1956 practices, representing one third of the population of England) enable regular VCR reports.

The COVID pandemic did not seem to have a detrimental effect on influenza vaccine uptake, as reported here, which is an unexpected finding in light of the problems with vaccine acceptance surrounding the COVID vaccination programs. Indeed, different concerns have been identified among adults with respect to the COVID-19 and influenza vaccines. For COVID-19, the major reasons cited were wanting more research done, worries about vaccine safety and effectiveness, and believing they are already well-protected through prior vaccination or infection [Citation176]. Indeed, it is well documented that vaccine acceptance is a complex phenomenon [Citation177], with more than 70 influencing factors identified, many of which are time-specific and context-specific [Citation178]. These include, but are not limited to, mistrust of government and health authorities, concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy and, in some countries, age and minority race or ethnicity [Citation179–181]. While analysis of this complex behavioral phenomena is beyond the scope of this manuscript, our findings do suggest that there are differences in vaccine uptake across the countries who provided data that was particularly evident between countries in Western and Eastern Europe: for Western European countries, these include fear of adverse events, a lack of trust among the general public and healthcare professionals regarding the effectiveness of the influenza vaccine, and denial of the risk of catching influenza; for Eastern European countries these include a lack of appreciation of the true burden of influenza, particularly with regard to risk and severity, and a lack of trust in the health authorities [Citation178,Citation182]. We hope that the results presented herein will act as a call for future investigation that focusses on the disparities across Europe as a means to address the differences and harmonize vaccine uptake across the region.

Another noteworthy finding from this survey was that some of the countries with the lowest VCRs in older adults had the broadest recommendations for influenza vaccination in at-risk populations (e.g. children, adolescents, pregnant women). Based on the low VCR results presented here, we call for further studies to investigate the reasons that drive low vaccine uptake, on a country-by-country basis, with the intention to identify the commonalities and differences in the reasons as an initial step to address them. Furthermore, acceptance of a common list of recommendations for influenza vaccination in Europe could enable better comparison of VCRs among these countries.

We acknowledge several limitations of this survey. Firstly, when reporting the country-specific burden, no account was made for differences in population sizes among the different countries included in the survey. As some of the countries were small and we could not determine the demographic distribution or whether influenza care was universally distributed across the whole country or was focused on large cities/regions, we have not accounted for such differences and have chosen to report a snapshot of the overall data as reported in the publications. Secondly, we fully acknowledge the criticisms that have been raised about studies reporting vaccine effectiveness data for all-cause mortality and the efforts made to implement study designs that differentiate vaccine effects from selection bias in elderly populations [Citation183–191]. However, we again feel that further discussion of this topic is outside the scope of this manuscript. Finally, in a similar vein, we acknowledge that, even when VCR is high, there are many factors that could contribute to low vaccine effectiveness reported in older population, such as immunosenescence and during antigenic drift and egg adaption, which may be ameliorated through enhanced and non-egg-based vaccines. However, suggesting recommendations to improve vaccine effectiveness would be beyond the remit of this manuscript, the aim of which is to provide a snapshot of the current situation across the countries surveyed. Our results do, however, raise the question whether high VCRs alone are sufficient to fully tackle the burden of influenza or whether additional parallel measures should be adopted. For example, despite having consistently high vaccination coverage, NHS England mandated early vaccination for 2–3-year-olds and school-age children (reception to year 11, a super-spreader population) and children in clinical risk groups, commencing from 1 September 2023 or as early as possible after the vaccine becomes available, with the vaccination program completed by 15 December. The aim of prioritizing this group early in the season was to reduce transmission and ensure minimal impact on routine immunizations in the new year [Citation192]. We eagerly await the full report on the effect this intervention had on the influenza data for the 2023/24 season.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first endeavor to publish local data on vaccine coverage, the infrastructure for influenza monitoring in the contributing countries and the burden of influenza. The results of this analysis show there is an urgent need for a standardized, aligned, and consistent methodology for reporting influenza burden of disease and VCRs across Europe. As seen from the country-specific literature reported here, the VCRs remain below the WHO-recommended target in most of the countries surveyed, with a lower trend for uptake in countries in Eastern Europe compared with Western Europe. Data on increased hospitalization rates in the older population were available for Portugal and the UK, despite these being the only two countries consistently meeting the recommended VCR of ≥ 75%. These data show that the disease burden in older adults remains high. Factors contributing to this may include the loss of or reduced immunity during the COVID-19 lockdown periods, when the overall population were not exposed to influenza virus, and the use of non-pharmacological measures to limit disease transmission. This may indicate the need for complementary measures, such as increased awareness and education on the burden of disease, and broader usage of improved influenza vaccines for older adults. Unexpectedly, the COVID pandemic did not seem to have a detrimental effect on influenza vaccine uptake, and this finding could provide a unique insight for future studies on the behavioral basis of vaccine acceptance. Furthermore, owing to the great heterogeneity in the data and reporting methods among regions, recommendations for a standardized reporting framework may provide greater transparency and visibility on influenza severity and disease burden. These may also enable the impact of interventions, such as increased VCRs, improvements in the perception of the vaccines, and the introduction of improved vaccines for older adults, to be measured accurately.

6. Expert opinion

Periodic surveys, such as this one conducted by the RAISE expert group, provide an invaluable snapshot on the burden of influenza and the measures in place to tackle influenza across Europe. Pertinently, the results of this survey show that the burden of disease in older adults (influenza-associated GP visits, hospitalizations, ICU admissions and deaths), remains high, while VCR is below the WHO/Council of the European Union recommended threshold of ≥ 75% in all but two of the countries. There is a wide disparity in VCR between countries in Western Europe and in those in Central and Eastern Europe. Annual vaccination leading to an appropriate VCR in high-risk populations is considered a necessary approach to reduce the disease burden. Such a strategy may also improve protection beyond influenza itself and address the ‘hidden’ burden of influenza in high-risk groups such as older adults. Recognition of the broader consequences of influenza virus infection is essential to determine the entire burden of influenza among different subpopulations, especially in older adults, and appreciate the true value of preventive approaches such as vaccination.

Notably, following the COVID-19 pandemic there seems to have been a modest increase in influenza VCR in the 2020/21 season; however, the situation in the subsequent seasons would suggest that levels are once again returning to pre-pandemic levels. This highlights the pressing need to capitalize on the ‘COVID-19 effect’ and to implement ways in which this can be maintained and improved upon, leading to a sustained change in attitudes to vaccination across the continent. Whether this requires the application of complementary measures, such as increased awareness and education on the burden of disease, wider use of improved influenza vaccines in older adults, targeting other populations that are affected by seasonal influenza and act as super-transmitters (e.g. children) or the application of a more stringent VCR threshold – as is the case in the U.S.A., where a 90% VCR threshold has been recommended – needs to be thoroughly investigated.

Although beyond the scope of this manuscript, there are several recognized barriers to flu vaccine uptake in older adults. Furthermore, the barriers to vaccine acceptance may vary between Western European countries (fear of side effects, a lack of trust among the general public and healthcare professionals regarding the effectiveness of the influenza vaccine, and denial of the risk of contracting influenza) and Eastern European countries (a lack of appreciation of the true burden of influenza, particularly with regard to risk and severity, and a lack of trust in the health authorities). Furthermore, additional educational interventions should be aimed toward healthcare workers because members of some countries pointed out the problem of vaccine acceptance among this group is inevitably reflected in the vaccine acceptance among the general population. This clearly demonstrates that a one-size-fits-all approach will not be sufficient to address the barriers to vaccine acceptance across Europe. Only by identifying and addressing the root causes of these and acknowledging that the causes may vary among regions, can country-by-country contingency plans be developed and instigated with the aim to identify the commonalities and differences in the reasons. Acknowledging this may be an initial step to bring all countries up to the recommended threshold for vaccine coverage.

Finally, owing to the great heterogeneity in the data and reporting methods among regions, developing a standardized reporting framework and standardized recommendations for influenza vaccination among the European countries may provide greater transparency and visibility on influenza severity and the burden of disease. These may also enable the impact of interventions, such as increased VCR, improvements in the perception of the vaccines and the introduction of improved vaccines for older adults, to be measured accurately.

Article highlights

This survey highlights the heterogeneity in the available data and reporting methods for influenza disease burden among countries.

Influenza is generally a vaccine-preventable disease, and all countries surveyed here have official recommendations for free vaccination for older adults.

All countries surveyed have a defined framework for the monitoring and reporting of influenza activity and extreme outcomes.

Despite this, in most of the countries the vaccine coverage rate (VCR) in older adults remains below the 75% threshold suggested by the World Health Organisation/Council of the European Union, with much lower rates reported in countries in Eastern and Central Europe than in those in Western Europe.

Additionally, even countries with VCR above the WHO target (Portugal and UK) reported high hospitalization rates in older adults.

Declaration of interests

George Kassianos is a National Immunisation Lead, Royal College of General Practitioners, President British Global & Travel Health Association, Chair Pan-European Influenza Group RAISE, and Board Member, European Scientific Working Group on Influenza (ESWI) and received fees for conferences and scientific advice from Merck/MSD, Sanofi Pasteur, Seqirus, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, GSK, Valneva, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen and Novavax. Rok Civljak received fees from Sanofi, Pfizer, and Swixx Biopharma for lectures, conferences and/or scientific advice. Filipe Froes received conference fees and scientific advice from Sanofi, Pfizer, MSD, AstraZeneca and GSK. Gerrit Adrianus van Essen reports speaker fees from MSD, Sanofi, GSK; Chair of the Dutch Influenza Foundation, sponsored by GSK, Sanofi, Viatris and Seqirus. Raul Ortiz de Lejarazu received fees for conferences and academic scientific advice from Abbot, AstraZeneca, GSK, Moderna, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and Seqirus/CSL, not directly related to the content of this article. Zuzana Kristufkova received fees from Merck/MSD, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer and Viatris for conferences and scientific advisory. Inga Ivaskeviciene received fees for conferences and scientific advice from Merck/MSD, Sanofi, Pfizer, Astra Zeneca and Ewopharma. Jörg Schelling received fees for conferences and scientific advice from Merck/MSD, Sanofi Pasteur, Seqirus, Pfizer, MSD, AstraZeneca, GSK, Janssen, Novaxax, Bavarian Nordic, BioNTech, Viatris and Moderna. Miloš Marković received fees from MSD, Sanofi, Pfizer, GSK, Amicus and Medison Pharma for lectures, conferences and/or scientific advice. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (105.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cristina Angelin-Duclos and Anvar Rassouli for support with data collection, coordination and scientific input. Scientific writing assistance was provided by Steven Goodrick of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare Ltd, UK (funded by Sanofi), and editorial support by Isabel Gregoire from Sanofi.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2024.2340470

Additional information

Funding

References

- CDC. Cold versus flu. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/symptoms/coldflu.htm#:~:text=The%20symptoms%20of%20flu%20can,a%20runny%20or%20stuffy%20nose

- CDC. Flu symptoms & complications. 2022 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/symptoms/symptoms.htm?web=1&wdLOR=c1FDA10F8-0345-44F8-AADE-3C8CADB6F885

- Macias AE, McElhaney JE, Chaves SS, et al. The disease burden of influenza beyond respiratory illness. Vaccine. 2021;39 Suppl 1:A6–A14.

- Morris DE, Cleary DW, Clarke SC. Secondary bacterial infections associated with influenza pandemics. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1041. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01041

- Gu Y, Zuo X, Zhang S, et al. The mechanism behind influenza virus cytokine storm. Viruses. 2021;13(7). doi: 10.3390/v13071362

- Low D. Reducing antibiotic use in influenza: challenges and rewards. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(4):298–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01910.x

- WHO. Influenza (seasonal): fact sheet. 2023 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets

- Sanz-Muñoz I, Tamames-Gómez S, Castrodeza-Sanz J, et al. Social distancing, lockdown and the wide use of mask; a magic solution or a double-edged sword for respiratory viruses epidemiology? Vaccines. 2021;9(6). doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060595

- WHO. Joint statement - influenza season epidemic kicks off early in Europe as concerns over RSV rise and COVID-19 is still a threat. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/01-12-2022-joint-statement—influenza-season-epidemic-kicks-off-early-in-europe-as-concerns-over-rsv-rise-and-covid-19-is-still-a-threat

- Tanne JH. US faces triple epidemic of flu, RSV, and covid. BMJ. 2022;379:o2681. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o2681

- CDC. CDC tracks ongoing flu activity in the southern hemisphere. [cited 2023 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2022-2023/ongoing-flu-southern-hemisphere.htm

- Fluview interactive. National, regional, and state level outpatient illness and viral surveillance. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/fluview/fluportaldashboard.html

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO. Flu news europe: 2022-2023 season overview. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://flunewseurope.org/SeasonOverview

- Paget J, Danielle Iuliano A, Taylor RJ, et al. Estimates of mortality associated with seasonal influenza for the European Union from the GLaMOR project. Vaccine. 2022;40(9):1361–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.080

- Wilhelm M. Influenza in older patients: a call to action and recent updates for vaccinations. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(2 Suppl):S15–S24.

- CDC. About flu. CDC website. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 17]. Available from: cdc.gov/flu/about/index.html

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza vaccination and antiviral use in EU/EEA member states. 2018 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/seasonal-influenza-antiviral-use-2018.pdf

- Blank PR, van Essen GA, Ortiz de Lejarazu R, et al. Impact of European vaccination policies on seasonal influenza vaccination coverage rates: an update seven years later. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(11):2706–2714. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1489948

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other seasonal respiratory viruses in the UK Winter 2020 to 2021. 2021 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchivesgov.uk/ukgwa/20220401215804/https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

- National Centre for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.ncipd.org/index.php?lang=bg

- Ministry of Health Bulgaria. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.mh.government.bg/en/

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Influenza in Croatia in the 2022/23 seasons (week 19, 2023). 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/sluzba-epidemiologija-zarazne-bolesti/gripa-u-hrvatskoj-u-sezoni-2022-2023-19-tjedan-2023/

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia. Three-year program for 2022–2024 on immunization, seroprophylaxis and chemoprophylaxis for special population groups and individuals at increased risk of: tuberculosis, hepatitis a and B, rabies, yellow fever, cholera, typhoid fever, tetanus, measles, severe lower respiratory system diseases caused by respiratory syncytial virus, tick-borne meningoencephalitis, chickenpox, rotavirus gastroenteritis, malaria, streptococcal disease (including invasive pneumococcal disease), Haemophilus influenzae-invasive disease, invasive meningococcal disease, HPV infection, COVID-19 and monkeypox disease. 2021 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://zdravlje.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/2021Objave/Trogodi%C5%A1nji%20program_imunizacija%202022.-2024.%20Program%20II.pdf

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia. Statute on implementation of immunoprophylaxis, seroprophylaxis and chemoprophylaxis against infectious diseases and on persons who must submit to this obligation. Official gazette, No. 103/2013, 144/2020, and 133/2022. 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2013_08_103_2322.html

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia. Implementation program of mandatory vaccination in the Republic of Croatia in 2023 against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, measles, mumps, rubella, tuberculosis, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type B disease and pneumococcal disease. 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Provedbeni-program-obveznog-cijepljenja-u-2023.pdf

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia. Implementation program on immunoprophylaxis, seroprophylaxis and chemoprophylaxis for special groups of the population and individuals at increased risk of: tuberculosis, hepatitis A and B, rabies, yellow fever, cholera, typhoid, tetanus, measles, severe lower respiratory system diseases caused by respiratory syncytial virus, tick-borne meningoencephalitis, chicken pox, rotavirus gastroenteritis, malaria, streptococcal disease (including invasive pneumococcal disease), Haemophilus influenzae-invasive disease, invasive meningococcal disease, HPV infection, COVID-19 and monkeypox disease in 2023. 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Provedbeni-program-imunizacije-2-u-2023.pdf

- Státní zdravotní ústav. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://szu.cz/tema/a-z-infekce/ch/chripka/ockovani-proti-chripce-sezona-2022-2023-the-flu-vaccination-2022-2023-season/

- Parlament České republiky. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.psp.cz/sqw/sbirka.sqw?cz=473&r=2021%20or%20https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2021-473

- Terviseamet. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.terviseamet.ee/et/nakkushaigused/tervishoiutootajale/nakkushaigustesse-haigestumine/gripp-ja-gripilaadsetesse

- Meditsiini-Uudised. Gripi vastu lasi end vaktsineerida umbes iga kümnes inimene. MU. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.mu.ee/uudised/2023/05/29/gripi-vastu-lasi-end-vaktsineerida-umbes-iga-kumnes-inimene

- Sante Publique. Flu epidemiological bulletin, week 18. Preliminary report. 2022-2023 season. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-et-infections-respiratoires/grippe/documents/bulletin-national/bulletin-epidemiologique-grippe-semaine-18.-bilan-preliminaire.-saison-2022-2023

- Sante Publique. Health monitoring of mortality. Weekly update of June 20, 2023. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/surveillance-syndromique-sursaud-R/documents/bulletin-national/2023/surveillance-sanitaire-de-la-mortalite.-point-hebdomadaire-du-20-juin-2023

- Sante Publique. Flu. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://vaccination-info-service.fr/Les-maladies-et-leurs-vaccins/Grippe

- l’Assurance Maladie. Vaccination campaign against seasonal influenza 2022-2023. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.ameli.fr/medecin/sante-prevention/vaccination-grippe-saisonniere

- l’Assurance Maladie. Conventional rates for general practitioners in metropolitan France. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. https://www.ameli.fr/medecin/exercice-liberal/facturation-remuneration/consultations-actes/tarifs/tarifs-generalistes/tarifs-metropole

- l’Assurance Maladie. Vaccination by the nurse. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.ameli.fr/infirmier/exercice-liberal/service-patient/vaccination-par-infirmier

- Ministere de la Sante et de la Prevention. Questions/Answers - Seasonal flu. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/maladies/maladies-infectieuses/les-maladies-de-l-hiver/article/questions-reponses-grippe-saisonniere

- Sante Publique. Flu vaccination coverage data by age group. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/determinants-de-sante/vaccination/articles/donnees-de-couverture-vaccinale-grippe-par-groupe-d-age

- Sante Publique. Study of flu vaccination coverage of residents and salaried professionals of medico-social establishments, 2023. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/etudes-et-enquetes/etude-de-couverture-vaccinale-contre-la-grippe-des-residents-et-professionnels-salaries-des-etablissements-medico-sociaux-2023

- Groupe d'Expertise et d'Information sur la Grippe. Vaccination: vaccine coverage. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: http://www.grippe-geig.com/couverture-vaccinale.html

- Robert J, Detournay B, Levant MC, et al. Flu vaccine coverage for recommended populations in France. Med Mal Infectieuses. 2020;50(8):670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2019.12.004

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft Influenza. Wochenberichte der AGI. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://influenza.rki.de/Wochenberichte.aspx

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft Influenza. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://influenza.rki.de/Arbeitsgemeinschaft.aspx

- Robert Koch Institut. Hochdosis-Impfstoff (Stand: 16.9.2022). 203. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.rki.de/SharedDocs/FAQ/Impfen/Influenza/Hochdosis-Impfstoffe/FAQ-Liste.html

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss. Schutzimpfungs-Richtlinie. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.g-ba.de/richtlinien/60/

- Kassenärzliche Vereinigumg Bayerns. Informationen rund ums Impfen. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.kvb.de/mitglieder/verordnungen/impfungen/

- National Public Health Organization. COVID-19 Guidelines. 2021 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://eody.gov.gr/

- Ministry of Health Israel. Surveillance Report on morbidity due to respiratory viruses, weeks 14/2022 to 14/2022 (3/10/21-9/4/22). 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/en/departments/publications/?OfficeId=104cb0f4-d65a-4692-b590-94af928c19c0&limit=10&publicationType=9698793e-48f5-4941-8555-b67ca738db63&topic=430fb082-839f-43f3-a58f-3d4d59905e57&subTopic=f164f857-d211-41f1-9bf5-da7b5d1785ab&skip=0

- Ministry of Health Israel. Vaccines in adulthood. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.il/Subjects/Geriatrics/HealthPromotionAndPreventiveMedicine/Tests_drugs_and_vaccines/Pages/Vaccines_In_Elderly.aspx#:~:text=%D7%97%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%95%D7%9F%20%D7%9B%D7%A0%D7%92%D7%93%20%D7%A9%D7%A4%D7%A2%D7%AA%20%D7%9E%D7%95%D7%9E%D7%9C%D7%A5%20%D7%9C%D7%9B%D7%9C%D7%9C,%D7%9C%D7%90%D7%A0%D7%A9%D7%99%D7%9D%20%D7%A9%D7%9E%D7%98%D7%A4%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%9D%20%D7%91%D7%A7%D7%A9%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%99%D7%9D%20%D7%90%D7%95%20%D7%91%D7%97%D7%95%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%9D

- Ministry of Health Israel. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/flu-15042023/he/files_weekly-flu-corona_flu_he_flu_15042023.pdf.

- Slimību profilakses un kontroles centrs. Pārskati par akūtu augšējo elpceļu infekciju, gripas un COVID-19 izplatību. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.spkc.gov.lv/lv/parskati-par-akutu-augsejo-elpcelu-infekciju-gripas-un-covid-19-izplatibu?utm_source=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

- Slimību profilakses un kontroles centrs. Imunizācijas valsts padome. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.vm.gov.lv/lv/imunizacijas-valsts-padome

- Slimību profilakses un kontroles centrs. Vakcinācija pret gripu un Covid-19. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.spkc.gov.lv/lv/vakcinacija-pret-gripu-un-covid-19

- National Public Health Center under the Ministry of Health. MorbIdity data. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://nvsc.lrv.lt/lt//uzkreciamuju-ligu-valdymas/uzkreciamosios-ligos/gripas-1/sergamumo-duomenys

- National Public Health Centre under the Ministry of Health. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://nvsc.lrv.lt/en/

- Ministry of Health Protection of the Republic of Lithuania. The flu. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://sam.lrv.lt/lt/veiklos-sritys/visuomenes-sveikatos-prieziura/uzkreciamuju-ligu-valdymas/gripas

- National Public Health Center under the Ministry of Health. Flu vaccine. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://nvsc.lrv.lt/lt/uzkreciamuju-ligu-valdymas/uzkreciamosios-ligos/gripas-1/gripo-vakcina

- Ministry of Health of The Republic of Lithuania. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://sam.lrv.lt/en/

- Vakcinos nuo sezoninio gripo sunaudojimas 2022/2023. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://nvsc.lrv.lt/uploads/nvsc/documents/files/2023%2006%2013%20vakcin%C5%B3%20nuo%20sezoninio%20gripo%20sunaudojimas.pdf

- Officailios statitikos portalas. Residents of Lithuania (2022 edition): population and composition. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug14]. Available from: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/lietuvos-gyventojai-2022/salies-gyventojai/gyventoju-skaicius-ir-sudetis

- NIVEL. Flu: Influenza Newsletters. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.nivel.nl/nl/resultaten-van-onderzoek/griep-centraal-weekcijfers-en-meer/griep-influenza-nieuwsbrieven

- Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. Annual report Surveillance of COVID-19, influenza and other respiratory infections in the Netherlands: winter 2021/2022. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/publicaties/annual-report-surveillance-of-covid-19-influenza-and-other-respiratory-infections-in-0

- Nederlands Huisarten Genootschap. Practical Guide Flu Vaccination. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.nhg.org/praktijkvoering/vaccinatieprogrammas/praktijkhandleiding-griepvaccinatie/

- NIVEL. Vaccination rate National Program Pneumococcal Vaccination Adults 2021: monitor in brief. 2021 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.nivel.nl/nl/publicatie/vaccinatiegraad-nationaal-programma-pneumokokkenvaccinatie-volwassenen-2021-monitor-het

- Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego. http://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/grypa/index.htm

- Wilcez M. Notes from Poland: Poland Launches free flu vaccine for all adults. [cited 2023 Sep 14]. Available from: https://notesfrompoland.com/2021/11/22/poland-launches-free-flu-vaccines-for-all-adults/#:~:text=Poland’s%20government%20has%20made%20influenza,the%20case%20–%20needing%20a%20prescription

- Narodowy Fundusz Zdrowia. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.nfz.gov.pl/aktualnosci/aktualnosci-centrali/szczepienia-przeciwko-grypie-sprawdz-gdzie-sie-zaszczepisz,8255.html

- Szczepienia. Jaki jest poziom zaszczepienia przeciw grypie w Polsce?. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. https://szczepienia.pzh.gov.pl/faq/jaki-jest-poziom-zaszczepienia-przeciw-grypie-w-polsce/

- Serviço Nacional de Saúde. Flu surveillance. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.insa.min-saude.pt/?s=vigil%C3%A2ncia+da+gripe

- Serviço Nacional de Saúde. Resultados da Pesquisa por: vigilância da gripe. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.insa.min-saude.pt//?s=vigil%C3%A2ncia+da+gripe

- Serviço Nacional de Saúde. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.dgs.pt/

- Sociedade Portuguesa de Pneumologia. VACCINÔMETRO® - final data for the 2022/2023 flu season reveal that 83.2% of Portuguese people aged 65 or over will have been vaccinated. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.sppneumologia.pt/noticias/vacinometro-dados-finais-da-epoca-gripal-de-2022-2023-revelam-que-832-dos-portugueses-com-65-ou-mais-anos-de-idade-terao-sido-vacinados

- Institute of Public Health Serbia. Professional and methodological guidelines for implementation of mandatory and recommended immunization of population for 2023. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.batut.org.rs/download/SMUredovneImunizacije2023.pdf

- Slovak Public Health Office. Flu. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.uvzsr.sk/web/uvz/chripka

- Carlos III Health Institute. Sentinel surveillance of acute respiratory infection -. Weekly reports. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Paginas/VIGILANCIA-CENTINELA-DE-INFECCION-RESPIRATORIA-AGUDA.aspx

- Sistema Nacional de Salud. Recomendaciones de vacunación frente a la gripe temporada 2022-2023. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/programasDeVacunacion/docs/Recomendaciones_vacunacion_gripe.pdf

- Public Health England. PHE influenza surveillance graphs. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/860300/PHE_Influenza_Surveillance_graphs_2019_2020_week_4.pdf

- GOV.UK. National flu and COVID-19 surveillance reports: 2022 to 2023 season. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-flu-and-covid-19-surveillance-reports-2022-to-2023-season?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=govuk-notifications-topic&utm_source=8d133ecf-62b9-480a-803b-bfd9f7f518ab&utm_content=daily.

- GOV.UK. National flu immunisation programme 2023 to 2024 letter. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-flu-immunisation-programme-plan/national-flu-immunisation-programme-2023-to-2024-letter

- GOV.UK. General medical services statement of financial entitlements directions. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/general-medical-services-statement-of-financial-entitlements-directions

- NHS England. Investment and Evolution: Update to the GP contract agreement 2020/21 – 2023/24. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/investment-and-evolution-update-to-the-gp-contract-agreement-20-21-23-24/

- GOV.UK. Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in GP patients: monthly data, 2022 to 2023. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/seasonal-influenza-vaccine-uptake-in-gp-patients-monthly-data-2022-to-2023?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=govuk-notifications-topic&utm_source=d85f594d-ffa6-48c8-a65c-22803e71ae83&utm_content=daily

- Perovic Mihanovic ML IK, Vickovic N, Huljev E, et al. Rational approach to pneumonia treatmet during influenza season. 13th Croatian Congress of Clinical Microbiology and the 10th Croatian Congress on Infectious Diseases Oct 20–23; Sibenik Croatia; 2022.

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Croatian Health Statistics Yearbook 2020]. Zagreb: CIPH; 2021. 2021 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis-za-2020-tablicni-podaci/

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Croatian Health Statistics Yearbook 2022]. Zagreb: CIPH; 2023. 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/periodicne-publikacije/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis-za-2022-g-tablicni-podaci/

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Croatian Health Statistics Yearbook 2021]. Zagreb: CIPH; 2022. 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis-za-2021-tablicni-podaci/

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Croatian Health Statistics Yearbook 2019]. Zagreb: CIPH; 2020. 2020 [cited 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis-za-2019/

- Kovács G, Kaló Z, Jahnz-Rozyk K, et al. Medical and economic burden of influenza in the elderly population in central and eastern European countries. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10(2):428–440. doi: 10.4161/hv.26886

- Kynčl J. Chřipka v roce 2020. Med praxi. 2020;17(4):212–214. doi: 10.36290/med.2020.040

- Terviseamet. Nakkushaiguste esinemine ja immunoprofülaktika Eestis 2019. aastal. 2020. Available from: https://www.terviseamet.ee/sites/default/files/Nakkushaigused/Haigestumine/epid_ulevaade_2019.pdf

- OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Estonia: country health profile 2021, state of health in the EU. 2021. Available from: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-12/2021_chp_et_english.pdf

- Terviseamet. Nakkushaiguste esinemine ja immunoprofülaktika Eestis 2011. aasta. 2012 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://www.terviseamet.ee/sites/default/files/content-editor/Nakkushaigused/Statistika/Nakkushaigused_ja_immunoprofulaktika/nakkushaigused_ja_immunoprofulaktika_eestis_2011.pdf

- Terviseamet. Nakkushaiguste esinemine ja immunoprofülaktika Eestis 2012. aastal. 2013 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://www.terviseamet.ee/sites/default/files/content-editor/Nakkushaigused/Statistika/Nakkushaigused_ja_immunoprofulaktika/nakkushaigused_ja_immunoprofulaktika_eestis_2012.pdf

- Statistics Estonia. [cited 2023 Sep]. Available from: https://www.stat.ee/en/node

- Guerche-Séblain C E, Amour S, Bénet T, et al. Incidence of hospital-acquired influenza in adults: a prospective surveillance study from 2004 to 2017 in a French tertiary care hospital. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(8):1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.12.003

- Fartoukh M, Voiriot G, Guérin L, et al. Seasonal burden of severe influenza virus infection in the critically ill patients, using the assistance publique-hôpitaux de paris clinical data warehouse: a pilot study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00884-8

- Lemaitre M, Fouad F, Carrat F, et al. Estimating the burden of influenza-related and associated hospitalizations and deaths in France: an eight-season data study, 2010-2018. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2022;16(4):717–725. doi: 10.1111/irv.12962

- Paternoster M, Masse S, van der Werf S, et al. Estimation of influenza-attributable burden in primary care from season 2014/2015 to 2018/2019, France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(6):1263–1269. doi: 10.1007/s10096-021-04161-1

- Pivette M, Nicolay N, de Lauzun V, et al. Characteristics of hospitalizations with an influenza diagnosis, France, 2012-2013 to 2016-2017 influenza seasons. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020;14(3):340–348. doi: 10.1111/irv.12719

- Damm O, Krefft A, Ahlers J, et al. Prevalence of chronic conditions and influenza vaccination coverage rates in Germany: results of a health insurance claims data analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2023;17(1):e13054. doi: 10.1111/irv.13054

- Geerdes-Fenge HF, Klein S, Schuldt HM, et al. Complications of influenza in 272 adult and pediatric patients in a German university hospital during the seasonal epidemic 2017–2018. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2022;172(11–12):280–286. doi: 10.1007/s10354-021-00884-0

- Robert Koch Institut. Bericht zur epidemiologie der influenza in Deutschland saison 2018/19. 2019. Available from: https://influenza.rki.de/Saisonberichte/2018.pdf

- Robert Koch Institut. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Influenza. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://influenza.rki.de/Saisonbericht.aspx

- Rößler S, Ankert J, Baier M, et al. Influenza-associated in-hospital mortality during the 2017/2018 influenza season: a retrospective multicentre cohort study in central Germany. Infection. 2021;49(1):149–152. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01529-x

- Scholz S, Damm O, Schneider U, et al. Epidemiology and cost of seasonal influenza in Germany - a claims data analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1090. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7458-x

- von der Beck D, Seeger W, Herold S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of a cohort hospitalized for pandemic and seasonal influenza in Germany based on nationwide inpatient data. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180920

- EODY. Annual epidemiological report. 2021 [cited 2023 Apr]. Available from: https://eody.gov.gr/epidimiologika-statistika-dedomena/etisies-epidimiologikes-ektheseis/#heading-4%20

- Glatman-Freedman A, Kaufman Z, Stein Y, et al. Influenza season hospitalization trends in Israel: a multi-year comparative analysis 2005/2006 through 2012/2013. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):710–716. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2824

- Israel Center for Disease Control. Summary report: the 2013/2014 influenza season. 2014 [cited 2023 Feb]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/en/departments/publications/reports/flu2013-2014

- Israel Center for Disease Control. Summary report: the 2014/2015 influenza season. 2015 [cited 2023 Feb]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/en/departments/publications/reports/flu2014-2015

- Israel Center for Disease Control. Summary report: the 2015/2016 influenza season reoprt. 2016 [cited 2023 Feb]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/en/departments/publications/reports/flu2015-2016.

- Israel Center for Disease Control. Summary Report: the 2016/2017 influenza season. 2017 [cited 2023 Feb]. Availble from: https://www.gov.il/en/departments/publications/reports/flu2016-2017

- Israel Center for Disease Control. Summary report: the 2017/2018 influenza season. 2018 [cited 2023 Feb]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/en/Departments/publications/reports/flu2017-2018.

- Israel Center for Disease Control. Summary report: the 2018/2019 influenza season. 2019 [cited 2023 Feb]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/he/departments/publications/reports/flu2018-2019.

- Israel Center for Disease Control. Summary report: the 2019/2020 influenza season. 2020 [cited 2023 Feb]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/he/departments/publications/reports/flu2019-2020

- Giacchetta I, Primieri C, Cavalieri R, et al. The burden of seasonal influenza in Italy: a systematic review of influenza-related complications, hospitalizations, and mortality. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2022;16(2):351–365. doi: 10.1111/irv.12925

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Rapporto epidemiologico settimanale. Season 2016–2017. 2017 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/influenza/FluNews16-17

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. FluNews. Rapporto epidemiologico settimanale. Season 2017–2018. 2018 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/influenza/FluNews17-18

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. FluNews. RappOrto epidemiologico settimanale. Season 2018–2019. 2019 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/influenza/FluNews18-19

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. FluNews. Rapporto epidemiologico settimanale. Season 2019–2020. 2020 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/influenza/FluNews19-20

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. FluNews. RapPorto epidemiologico settimanale. Season 2020–2021. 2021 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/influenza/flunews20-21

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. FluNews. Rapporto epidemiologico settimanale. Season 2021–2022. 2022 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/influenza/flunews21-22

- Rosano A, Bella A, Gesualdo F, et al. Investigating the impact of influenza on excess mortality in all ages in Italy during recent seasons (2013/14-2016/17 seasons). Int J Infect Dis. 2019;88:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.08.003

- Centre of Disease Prevention and Control. Latvia.

- Kuliese M, Mickiene A, Jancoriene L, et al. Age-specific seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness against different influenza subtypes in the hospitalized population in Lithuania during the 2015–2019 influenza seasons. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):455. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050455

- National Public Health Centre under the Ministry of Health. Data for the 2019-2020, 202-2021 and 2021/2022 influenza seasons. 2023 [cited 2023 May]. Available from: https://nvsc.lrv.lt/lt/uzkreciamuju-ligu-valdymas/uzkreciamosios-ligos/gripas-1/sergamumo-duomenys

- National Public Health Centre under the Ministry of Health. Epidemiological analysis of the 2021-2022 influenza season. 2023 [cited 2023 May].

- Rijksinstitut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. In: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid WeS, editor. Staat van infectieziekten in Nederland 2021. 2022. https://www.rivm.nl/publicaties/staat-van-infectieziekten-in-nederland-2022s.

- Hallmann-Szelińska E, Łuniewska K, Szymański K, et al. Virological and epidemiological situation in the influenza epidemic seasons 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 in Poland. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1251:107–113.

- Czarkowski MP, Hallmann-Szelińska E, Staszewska E, et al. Influenza in Poland in 2011-2012 and in 2011/2012 and 2012/2013 epidemic seasons. Przeglad epidemiologiczny. 2014;68(3):455–63, 559–65.

- Kondratiuk K, Czarkowski MP, Hallmann-Szelińska E, et al. Influenza in Poland in 2013 and 2013/2014 epidemic season. Przeglad epidemiologiczny. 2016;70(3):407–419.

- Szymański K, Łuniewska K, Hallmann-Szelińska E, et al. Respiratory virus infections in people over 14 years of age in Poland in the epidemic season of 2017/18. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1222:75–80.

- Łuniewska K, Szymański K, Kondratiuk K, et al. Subtypes of Influenza virus infection and outcomes in individuals older than 65 years of age in Poland in the 2016/2017 to 2019/2020 epidemic seasons. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e929243. doi: 10.12659/MSM.929243

- Szymański K, Hallmann E, Łuniewska K, et al. Spread of Influenza Viruses in Poland and neighboring countries in seasonal terms. Pathogens. 2021;10(3). doi: 10.3390/pathogens10030316

- Froes F, Carmo M, Lopes H, et al. Excess hospitalizations and mortality associated with seasonal influenza in Portugal, 2008–2018. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):726. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07713-8

- Pană A, Pistol A, Streinu-Cercel A, et al. Burden of influenza in Romania. A retrospective analysis of 2014/15 - 2018/19 seasons in Romania. Germs. 2020;10(4):201–209. doi: 10.18683/germs.2020.1206

- Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet (London, England). 2018;391(10127):1285–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2

- Igtokovidova P, Szalay T, Kri§tafkova Z, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination on seasonal mortality. Zdravotnicke listy. 2023;11(4):6. accepted for publication 20 November.

- Domínguez A, Soldevila N, Toledo D, et al. The effectiveness of influenza vaccination in preventing hospitalisations of elderly individuals in two influenza seasons: a multicentre case-control study, Spain, 2013/14 and 2014/15. Euro Surveillance Bulletin Europeen Sur Les Maladies Transmis European Communic Dis Bulletin. 2017;22(34). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.34.30602

- Oliva J, Delgado-Sanz C, Larrauri A. Estimating the burden of seasonal influenza in Spain from surveillance of mild and severe influenza disease, 2010-2016. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018;12(1):161–170. doi: 10.1111/irv.12499

- Pumarola T, Díez-Domingo J, Martinón-Torres F, et al. Excess hospitalizations and mortality associated with seasonal influenza in Spain, 2008–2018. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08015-3

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses, including novel respiratory viruses, in the United Kingdom: Winter 2012/13. 2013 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk//ukgwa//20220401215804/https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses in the United Kingdom. Winter 2013/14. 2014. [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.govuk/ukgwa/20220401215804/https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses in the United Kingdom: winter 2014 to 2015. 2015 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://webarchivenationalarchives.gov.uk//ukgwa/20220401215804/https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses in the United Kingdom: Winter 2015 to 2016. 2016 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/uk.gwa/20220401215804/https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses in the UK: Winter 2016 to 2017. 2017 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20220401215804//https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics//annual-flu-reports.

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses in the UK: Winter 2017 to 2018. 2018 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://web.archive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20220401215804/https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses in the UK Winter 2018 to 2019. 2019 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa//20220401215804/https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

- Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses in the UK Winter 2019 to 2020. 2020 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20220401215804//https://www.gov.uk/government//statistics/annual-flu-reports.

- Pokutnaya D, Loiacono MM, Booth H, et al. The impact of clinical risk conditions on influenza and pneumonia diagnoses in England: a nationally representative retrospective cohort study, 2010–2019. Epidemiol Infect. 2022;150:e107. doi: 10.1017/S0950268822000838

- Adlhoch C, Gomes Dias J, Bonmarin I, et al. Determinants of Fatal Outcome in Patients Admitted to Intensive Care Units With Influenza, European Union 2009-2017. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(11):ofz462. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz462

- Ganczak M, Gil K, Korzeń M, et al. Coverage and influencing determinants of influenza vaccination in elderly patients in a country with a poor vaccination implementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(6):665. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060665

- Gorska-Ciebiada M, Saryusz-Wolska M, Ciebiada M, et al. Pneumococcal and seasonal influenza vaccination among elderly patients with diabetes. Postepy Higieny I Medycyny Doswiadczalnej (Online). 2015;69:1182–1189. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1176772

- Samel-Kowalik P, Jankowski M, Lisiecka-Biełanowicz M, et al. Factors associated with attitudes towards seasonal influenza vaccination in Poland: a nationwide cross-sectional survey in 2020. Vaccines. 2021;9(11). doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111336

- Rose AMC, Kissling E, Gherasim A, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H3N2) and B among laboratory-confirmed, hospitalised older adults, Europe, 2017-18: a season of B lineage mismatched to the trivalent vaccine. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020;14(3):302–310. doi: 10.1111/irv.12714

- CDC. Flu & People 65 Years and Older. 2022 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/65over.htm?web=1&wdLOR=c3AD2A459-1BE9-4FC5-9F91-7093B8E53846

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Factsheet about seasonal influenza. 2022 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/facts/factsheet

- National Foundation for Infectious Diseses. Care for Older Adults?. Care About Flu!. 2023 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.nfid.org/infectious-diseases/flu-and-older-adults/

- Gavazzi G, Krause KH. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(11):659–666. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00437-1

- Gozalo PL, Pop-Vicas A, Feng Z, et al. Effect of influenza on functional decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(7):1260–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04048.x

- Mallia P, Johnston SL. Influenza infection and COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2(1):55–64. doi: 10.2147/copd.2007.2.1.55

- CDC. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the immunization practices advisory committee (ACIP). MMWR Recommend Rep Morb Mortality Weekly Rep Recommend Rep. 1990;39(Rr–7):1–15.

- CDC. Study Shows Hospitalization Rates and risk of death from seasonal flu increase with age among people 65 Years and Older. 2019 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2018-2019/hopitalization-rates-older.html

- CDC. Key Facts About Influenza (Flu). 2022 [cited 2023 Mar]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/keyfacts.htm?web=1&wdLOR=cF29B01A6-9D3A-435B-B8ED-52092A9DED95

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Immunization and Infectious Diseases. 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 11]. Available from: https://wayback.archive-it.org/5774/20220414033335/https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives

- Cassini A, Colzani E, Pini A, et al. Impact of infectious diseases on population health using incidence-based disability-adjusted life years (DALYs): results from the Burden of Communicable Diseases in Europe study, European Union and European Economic Area countries, 2009 to 2013. Euro Surveillance Bulletin Europeen Sur Les Maladies transmis European Communic Dis bulletin. 2018;23(16). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.16.17-00454

- Warren-Gash C, Blackburn R, Whitaker H, et al. Laboratory-confirmed respiratory infections as triggers for acute myocardial infarction and stroke: a self-controlled case series analysis of national linked datasets from Scotland. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(3):1701794. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01794-2017

- Andrew MK, MacDonald S, Godin J, et al. Persistent functional decline following hospitalization with influenza or acute respiratory illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):696–703. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16950

- Samson SI, Konty K, Lee WN, et al. Quantifying the impact of influenza among persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a new approach to determine medical and physical activity impact. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021;15(1):44–52. doi: 10.1177/1932296819883340

- Kubale J, Kuan G, Gresh L, et al. Individual-level association of influenza infection with subsequent pneumonia: a case-control and prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e4288–e95. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1053

- Chen JR, Liu YM, Tseng YC, et al. Better influenza vaccines: an industry perspective. J Biomed Sci. 2020;27(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12929-020-0626-6

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza vaccines. 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/prevention-and-control/seasonal-influenza-vaccines

- WHO. Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire. 2012;87(47):461–476.

- Froes F, Morais A, Hespanhol V, et al. The Vacinómetro® initiative: an eleven-year monitorization of influenza vaccination coverage rates among risk groups in Portugal. Pulmonology. 2022;28(6):427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2022.03.005

- Díez-Domingo J, Redondo Margüello E, Ortiz de Lejarazu Leonardo R, et al. A tool for early estimation of influenza vaccination coverage in Spanish general population and healthcare workers in the 2018-19 season: the Gripómetro. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):825. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13193-x

- Steel Fisher GK, Findling MG, Caporello HL, et al. Divergent attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccine vs influenza vaccine. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2349881. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.49881

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

- Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, et al. Barriers of Influenza vaccination intention and behavior – a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005 – 2016. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0170550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170550

- Lazarus JV, Wyka K, White TM, et al. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3801. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31441-x

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature med. 2021;27(2):225–228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9

- Nguyen KH, Chen Y, Huang J, et al. Who has not been vaccinated, fully vaccinated, or boosted for COVID-19?. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50(10):1185–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2022.05.024

- Royal Society for Public Health. Moving the needle: promoting vaccination uptake across the life course. 2019 [cited 2023 May]. Availbale from: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/policy/vaccinations/moving-the-needle-promoting-vaccination-uptake-across-the-life-course.html

- Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Weiss NS, et al. Influenza vaccination and risk of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent elderly people: a population-based, nested case-control study. Lancet (London, England). 2008;372(9636):398–405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61160-5

- Ortqvist A, Granath F, Askling J, et al. Influenza vaccination and mortality: prospective cohort study of the elderly in a large geographical area. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(3):414–422. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00135306

- Simonsen L, Viboud C, Taylor RJ. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(26):2729–2730. author reply 30-1.

- Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Viboud C, et al. Mortality benefits of influenza vaccination in elderly people: an ongoing controversy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(10):658–666. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70236-0

- Simonsen L, Reichert TA, Viboud C, et al. Impact of influenza vaccination on seasonal mortality in the US elderly population. Arch Internal Med. 2005;165(3):265–272.

- Jackson LA, Nelson JC, Benson P, et al. Functional status is a confounder of the association of influenza vaccine and risk of all cause mortality in seniors. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(2):345–352. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi275

- Jackson LA, Jackson ML, Nelson JC, et al. Evidence of bias in estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness in seniors. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(2):337–344. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi274

- Jackson LA. Benefits of examining influenza vaccine associations outside of influenza season. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(5):439–440. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-805ED

- Fireman B, Lee J, Lewis N, et al. Influenza vaccination and mortality: differentiating vaccine effects from bias. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(5):650–656. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp173

- NHS England. Autumn/Winter (AW) 2023-24 Flu and COVID-19 Seasonal Campaign. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 29]. Availble from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/autumn-winter-aw-2023-24-flu-and-covid-19-seasonal-campaign/#:~:text=To%20maximise%20and%20extend%20protection,cohorts%20from%20the%207%20October