ABSTRACT

Despite widespread recognition that social learning can potentially contribute toward enhancing community resilience to climate-induced disaster shocks, studies on this process remain few and far between. This study investigates the role of local institutions (formal, informal, and quasi-formal) in creating learning arenas and translating social learning into collective action in flash flood-prone Sunamganj communities in Bangladesh. We follow a Case Study approach using qualitative research methods. Primary data were collected through 24 key informant interviews, 10 semi-structured interviews, six focus-group discussions, and two participant observations events. Our results reveal that the diversity and flexibility of local-level institutions creates multiple learning platforms in which social interaction, problem formulation, nurturing diverse perspectives, and generating innovative knowledge for collective action can take place. Within these formal and informal learning arenas, communities’ desire and willingness to be self-reliant and to reduce their dependency on external funding and assistance is clearly evident. Social learning thus paves the way for institutional collaboration, partnership, and multi-stakeholder engagement, which facilitates social learning-based collective action. Nurturing institutional diversity and flexibility at the local level is therefore recommended for transforming social learning into active problem-solving measures and to enhance community resilience to disaster shocks.

1. Introduction

Given the increasing intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, it is imperative for local communities to build resilience to climate-induced disaster-shocks (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Citation2012). Resilience is often defined as the capacity of communities to absorb shocks and stresses and to persist under continual disturbances (Berkes & Ross, Citation2013; Folke et al., Citation2010). This ability is largely shaped by the capacity of local institutions to learn from shocks and stresses and self-organise. Learning in the context of resilience thus implies social and institutional learning (Berkes, Citation2007).

The various framings of social learning in interdisciplinary scholarship (e.g. social-ecological system resilience, community and disaster resilience, and natural resources management) often results in confusion. Scholars draw theoretical aspects of social learning from different disciplines, such as psychology, adult education, and business management. In terms of theoretical import, the meaning of social learning hence varies widely (Armitage et al., Citation2008; Rodela, Citation2011; Tran et al., Citation2018). In this regard, Armitage et al. (Citation2008) have highlighted the ‘paradox of learning’, documenting five key areas of confusion regarding social learning: i) definitions of learning; ii) learning goals and expectations; iii) learning mechanisms; iv) identity of the person or organisation engaged in learning; and v) the risks and ethical ambiguities faced by different actors. In expanding the explanations, Rodela (Citation2011, Citation2013) documents that social learning literature involves individual-, network-, and system-centric approaches, and often tries to examine learning at the collective or social level from a change observed at the individual level.

The meaning and application of social learning also differs among diverse streams of scholarship. For instance, in the context of climatic variability, social learning is seen as a prerequisite for moving up the adaptation ladder (Collins & Ison, Citation2009; Tàbara et al., Citation2010). In the disaster risk reduction and resilience literature, social learning is considered a necessary condition for adaptation or adaptive resilience (Berkes, Citation2009; Cutter et al., Citation2008; Lei et al., Citation2014). Common themes found in the literature are that: i) social learning be considered a collective means of framing and reframing lessons learned; ii) participation in the process involved different stakeholders; iii) the process could be externally driven or spontaneous; iv) social interactions and sharing are important means of learning; and v) it is characteristically a process and/or an outcome (Baird et al., Citation2014; Benson et al., Citation2016; Collins & Ison, Citation2009; Ensor & Harvey, Citation2015; Johannessen & Hahn, Citation2013).

Drawing insights from a pluralistic epistemological framework for interdisciplinary work by Miller et al. (Citation2008), as well as from interdisciplinary scholarship on social learning, our main purpose is to identify what has been learned and to understand how social learning functions as a purveyor of new perspectives and knowledge for community resilience. Examination of building resilience to disaster shocks at the individual and institutional levels necessitate the adoption of multidimensional lenses. For our study, instead of corresponding to a particular theoretical view, we examine social learning as a process of building resilience to climate-triggered extreme events (e.g. flash floods) from multidimensional standpoints (e.g. social learning, institutions, and collective action). For the purpose of the present study, concurring with Reed et al. (Citation2010), we define social learning as a process involving demonstrated changes in understanding that goes beyond the boundaries of an individual person to become situated within wider social units or communities of practice through social interactions among various social actors and networks.

We consider social learning as an iterative process as well as an outcome (Reed et al., Citation2010), and focus on two-pronged outcomes: i) social learning itself, and ii) collective attributes (e.g. social networks, partnerships, and mutual agreements). For an iterative process to take place and social learning to emerge, it is necessary to have arenas or spaces where diverse social actors can deliberately engage in dialogue, debate, and network creation in order to achieve collective goals (Lumosi, Pahl-Wostl, & Scholz, 2019; Strauss, Citation1978). Thus, such arenas facilitate the process of framing and reframing issues and problems, nurturing diverse perspectives, resolving conflicts, and generating collective assumptions and consensus (Lumosi et al., Citation2019; Steyaert et al., Citation2007). As Berkes (Citation2009) posits, a change in knowledge or understanding takes place when ideas and experiences are shared by individuals through social interactions in an iterative way.

A perspective in education research concerning arenas for social interaction is also cited in climate change and disaster research literature, e.g. regarding interactions between climate experts and the general public (Cook & Overpeck, Citation2019; Cornes & Cook, Citation2018). The main goal of this approach is to foster awareness and a resultant change in understanding and behaviour for disaster risk reduction. While top-down information sharing and social interaction could result in changes in understanding, individual perceptual cues may result in fatalistic attitudes, disbelief, distrust, and negligence in taking action. It is considered less likely that such changes in understanding would subsequently lead to the adoption of proactive measures (Cook & Overpeck, Citation2019; Cornes & Cook, Citation2018). Departing from this notion, the conceptual framework of social learning that we are using underscores that, at the local level, the collective sharing of experiences, feedback, and interactions with each other, occurring iteratively through learning arenas, will nourish collective decision making, collaboration, and social learning-led collective action to revive and advance communities’ capacity to cope with uncertainty (Berkes, Citation2009).

However, some scholars have raised concerns regarding such a normative framing of social learning (Choudhury et al., Citation2021; Reed et al., Citation2010). For example, these arenas may not be a level playing ground due to differential power relationships and institutional structures (Rist et al., Citation2007). Such power-imbued learning arenas may shape the sharing of experiences (Purdon, Citation2003). We contend that a variety of local institutions are likely to offer different opportunities for local community members to share their experiences and learning.

We posit that different types of local-level institutions play critical roles in creating learning arenas (Ensor & Harvey, Citation2015; Lebel et al., Citation2010). Concurring with Young (Citation2002), we define institutions as systems of rules, decision-making procedures, and programmes that shape social practices, assign roles to the participants in these practices, and direct interactions among the actors with assigned roles. These rules and roles can be formal, informal, or quasi-formal (Gupta et al., Citation2010; Uddin et al., Citation2020a). In this study, we investigate the role played by these three forms of local institutions in creating participatory and interactive arenas for facilitating social learning and collective action.

Social learning and its collective attributes are not sufficient for building resilience. Learning needs to be translated into action to build resilience. Community resilience largely depends on the ability to act collectively. Communities’ ability to act or respond collectively in the face of disaster is known as community capacity, collective efficacy (Mancini et al., Citation2005, pp. 574–575), or collective agency (Dale, Citation2013). Collective attributes, such as social networks, trust, and mutual agreement may facilitate social learning-based collective action. Social learning yields these collective attributes and results in collective action primarily through extensive engagement of multiple stakeholders in social interactions and reflections. Based on common understanding and consensus to advance communal situations, groups of individuals consult amongst themselves about collective problems and undertake collective strategies (Keen et al., Citation2005). The concept of collective action broadly implies collective management strategies taken voluntarily by a group of individuals to reach a shared goal (Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2004). These actions can take place in the form of mobilisation of resources (e.g. physical, financial, and human), collective decisions, and setting rules and procedures for collective management and accomplishing shared goals (Assuah & Sinclair, Citation2019; Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2004).

Concuring with this conceputalization, our study considers collective action addressing flash flood hazards as concerted actions undertaken by local-level institutions (formal and informal) through engaging multiple actors [e.g. communtiy members, village leaders, members of the Union Parishad (UP – the lowest level of administartive unit)] in a collective decision-making process to pursue a common goal. Examples of such common goals are reducing vulnerability to environmental change, fostering the community's collective capital to withstand unprcedencted climatic shocks, and mobilising social capital for coping with crises. Notably, there remains a significant gap in our understanding of how local-level institutions translate social learning into collective action for building resilience. By focusing the role of local formal, informal, and quasi-formal institutions, the present study addresses this gap through an empirical investigation.

Socially embedded local-level institutions are key mediators of collective action and they foster collective capital. Local institutions have the potential to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change by leveraging existing social networks for mobilising resources (Agrawal, Citation2010), creating partnerships, generating and incorporating new perspectives, and creating opportunities for self-organisation (Berkes, Citation2007), and undertaking collective action. Institutions can carry out these actions collaboratively at the local level (i.e. horizontal and vertical linkages) (Berkes, Citation2009; Choudhury et al., Citation2019). To this end, various forms of collective capital, such as resource mobilisation, multistakeholder engagement, and institutional networks are of paramount importance. In rural Bangladesh, quasi-formal and formal institutions (e.g. UPs, Union Disaster Management Committees, Upazila Disaster Management Committees, and local NGOs), and informal institutions (e.g. faith-based committees, social networks, school committees) play indispensable roles in maximising collective capital and taking action collaboratively at the local level. Several recent studies have confirmed that they utilise social learning processes as a pathway to enhance community resilience (Choudhury et al., Citation2021; Uddin et al., Citation2020a; Uddin et al., Citation2020b).

The purpose of this study is to examine the role of social learning and local-level institutions in enhancing resilience to flash floods in the wetland communities of Bangladesh, most of which are located in the northeastern region of the country. The specific objectives are to: i) investigate the issues of social learning in diverse learning platforms by institutions at the local level; ii) analyse the processes and attributes of social learning; and iii) examine the role of local institutions in translating social learning and channelling collective attributes toward collective action for strengthening community resilience to flash floods.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study area and research design

The study was carried out in the northeastern region of Bangladesh, in a floodplain Union of Sunamganj District. The District is located in the Meghna River basin and surrounded by the Himalayan mountains in Assam and Meghalaya states of India. The District is one of the wettest areas in Sylhet Division, with mean yearly precipitation of 5357.56 mm (SD=784.68 mm) between 1997 and 2016 [Flood Forecasting and Warning Centre (FFWC), Citation2017]. In recent years, changes in rainfall patterns in the mountainous areas and rapid melting of Himalayan glaciers has increased both the frequency and intensity of climatic shocks in northeastern Bangladesh (FFWC, Citation2017). Communities living in the low-lying areas are highly exposed to multifarious environmental perturbations, such as flash floods, monsoon floods, heavy precipitation events, and droughts (Choudhury & Haque, Citation2016; Rahman et al., Citation2018). Because of climatic variability and frequent heavy precipitation, flash floods –rapid onset, nature-triggered extreme events – are initiated in the upstream regions of Meghalaya and hit the downstream communities in Bangladesh without much opportunity for providing flood forecasting information (Collier, Citation2007). Flash floods thus constitute a major environmental risk that can cause catastrophic losses of crops, destruction of houses and other properties, and that increase livelihood insecurity (Choudhury & Haque, Citation2016; Rahman & Salehin, Citation2013).

Wetland communities of the northwestern region of Bangladesh experienced six flash floods between 2000 and 2017 (Ahmed et al., Citation2017). Triggered by heavy precipitation within a short duration, the flash floods submerged the foothill communities for six months (June to November) (Azad, Citation2020; Choudhury & Haque, Citation2016). In 2017, the District of Sunamganj experienced three consecutive abnormal flash floods caused by high rainfall in late March, July, and August (FFWC, Citation2017). These floods affected 172,612 households and damaged 102,617 hectares of crops in the District (Kamal et al., Citation2018), leading to long-term livelihood insecurity in the foothill communities (Azad, Citation2020). However, dealing and coping with flood-impacts for long periods has spurred a sense of living together through generating a range of adaptive capacities – primarily by sharing their first-hand experiences with flash floods (Choudhury, Citation2015; Khan, Citation2011). Learning emerging from social interactions and first-hand experiences enables local, chiefly informal institutions to mobilise the foothill communities to assemble their collective capital (e.g. local natural resources, social network human capital, and external resources) (Azad, Citation2020). Such mobilisation assist them to heal and recover quickly from various types of shocks – socioeconomic and environmental disasters.

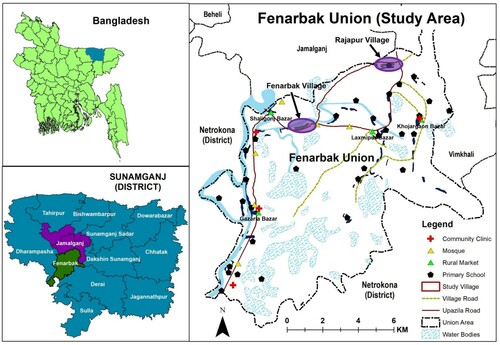

To examine the role of social learning and local-level institutions in enhancing community resilience, we applied a Case Study strategy of inquiry (Yin, Citation2014), using the framework of qualitative research, in the Fenarbak Union of Sunamganj District (). The Case Study approach (Creswell, Citation2014; Neuman, Citation2014) allowed us to investigate the salient processes of social learning and how social learning reshapes mechanisms for collective action towards flash flood risk reduction. The Case Study approach also helped with documenting in-depth insights into social learning within local-level institutions and its role in fostering community resilience.

The study area of Sunamganj District was selected primarily based on: i) its extreme physical exposure to flash floods in the Himalayan foothills and plains, ii) the unique characteristics of the haor (wetland) social-ecological systems of this District, and iii) recent experience of frequent flash flood disasters enabling the respondents to rely on their social memory and recollection of social learning. Two communities in the District's Fenarbak Union were selected for the study: Rajapur and Fenarbak. The main goal of selecting local-level institutions was to appraise how local-level institutions collaborate to foster community resilience through the social learning process. At the community level, various informal institutions – such as the Village Development Committees (VDC) and faith-based institutions – often organise learning arenas in which groups of community members can interact and share their experiences in order to obtain a collective consensus (Wenger, Citation1998).

Additionally, based on their social learning, several formal and quasi-formal institutions perform flood risk management activities collaboratively. To gain deeper insights into social learning at the formal and quasi-formal institutional level, we selected the Fenarbak UP, the Union Disaster Management Committee (UDMC), the Project Implementation Committees (PIC), and two local NGOs for an in-depth study. It is notable that the UDMC, in cooperation with the UP, facilitates disaster management activities at the local level. There are 36 members in the UDMC, including a chairperson, members of the UP, representatives from communities and local voluntary organisations, local NGO officials, and officials from relevant government institutions [Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief (MoDMR), Citation2019]. In order to take collective measures, these institutions establish social learning platforms in the form of meetings and public hearings in which key actors engage in social interaction. Thus, key actors preserve critical knowledge and the dynamics of collective measures taken for flood risk management.

2.2. Data collection and data analysis

Guided by qualitative research, both primary and secondary data were collected between July and December 2019. The primary data gathering process involved focus group discussions (FGDs), semi-structured interviews, key informant interviews (KIIs), and participant observation. A total of 40 face-to-face, in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted to elicit key insights into the roles of social learning and local-level institutions in fostering community resilience. Six FGDs were conducted with the two communities (three from each community) – one with farmers, one with fishermen, two with women, and two with mixed occupational groups, including farmers, fishermen, parents, private tutors, and elders. Each FGD meeting involved 8–12 participants and lasted between 60 and 75 min. FGD meetings typically focused on how social learning processes took place within the context of flash floods and how they fostered collective resilience-building action. Ten semi-structured interviews were also conducted with farmers (6) and fishermen (4), who were also members of the PIC, to gather data relating to key social learnings of the participants and to record their major concerns resulting from social learning for collective action.

Twenty-four KIIs were conducted with representatives from formal, quasi-formal, and informal institutions. The key informants represented various local stakeholders (). Data provided by the KIIs assisted us in unearthing the dynamics of social learning and key concerns identified through social learning processes for collective measures. During the field investigation, potential participants were recruited using both purposive and snowball sampling procedures (Creswell, Citation2014). Primary data were supplemented by participant observation. Two participatory learning platforms (i.e. a meeting of the UP and a meeting of the UDMC) were observed to understand how participants interact and nurture their ideas in order to identify key issues and problems and reframe their shared understandings and take decisions in terms of collective flood-related problems.

Table 1. Techniques of data collection and distribution of interviews.

All data were recorded using an audio recorder and transcribed for data analysis. The transcribed data were analysed using a data reduction method that assisted in identifying specific issues, simplifying themes, and transforming these themes into codes that were observed in the transcribed data (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). Utilising research objectives and guided questions, primary themes and sub-themes were also generated from the transcribed data through running texts. Key primary and sub-themes included were: i) social learning spaces and the key attributes of learning processes amongst formal, quasi-formal, and informal institutions; ii) key social learning from learning spaces and its roles in identifying key areas of intervention for collective action; iii) collective attributes of social learning that foster adopting collective action; and iv) dimensions of social learning and local-level institution-facilitated collaborative measures and their potential implications in building community resilience. To substantiate the dynamics of social learning, secondary documents, such as meeting minutes of the UDMC, the UP, and Ward meetings, were also procured.

3. Results

3.1. Social learning and informal institutions

In the wetland communities, we identified two informal social learning arenas – courtyard meetings and faith-based group meetings. Participants in such learning arenas tend to vary in terms of concerned issues and problems. For example, empirical results from an in-depth analysis of the KIIs revealed that courtyard meetings were mostly facilitated by the village leaders and concerned stakeholders (e.g. farmers and fishers), whereas religious leaders took the lead in faith-based learning arenas. However, one common concern in both informal learning arenas was the need to safeguard and protect collective assets (e.g. roads, mosques, and temples). One key lesson that emerged from these informal institutional learning arenas is the community's need to be self-reliant and reduce its dependency on external funding and assistance (). These learning arenas and social learning emerged spontaneously, reflecting the needs and aspirations of the wetland communities. Preexisting social networks activated learning platforms that engaged key stakeholders (e.g. village leaders and community members) and fostered developing shared goals for collective flood management via mobilising the necessary resources (i.e. funds and human capital).

Table 2. Informal institutional arena and social learning process.

Empirical evidence from the study area revealed that community members sought to reduce their external dependency and enhance their self-reliance by repairing and protecting their collective assets to reduce risk to their livelihoods from flash floods. For instance, VDCs, village leaders, and community members took collective action to repair gopats (large cattle paths used for communication and transportation of crops), recognising that the inability to act collectively can lead to community-wide hardship and an over-reliance on local elites that can significantly delay the recovery process. Such learning-driven initiatives were evident after the 2017 flash floods. Following this learning, they mobilised funds to carry out necessary activities.

In relation to livelihood risks, other areas of collective concern were: i) disseminating information on flash flooding as quickly as possible, and ii) resolving waterlogging problems. It was widely reported by most of the participants that protecting embankments from the sudden onset of flash floods requires speedy dissemination of flood information. This in turn can help with the rapid mobilisation of community members to take collective action and reduce dependence on local government institutions such as the local office of the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB).

In-depth interviews with farmers also corroborated that social networks among community people (especially farmers) helped in the resolution of waterlogging problems. Such problems are caused by water body leaseholders, whose interests conflict with those of the farmers. Farmers wish to drain the excess water for irrigation, whereas leaseholders wish to retain the water for fish production. The results of an in-depth analysis of KIIs confirmed that to resolve this conflict, a learning platform was created to facilitate the negotiation process between farmers and haor leaseholders. As part of the negotiation process, farmers had to pay BDT 170 (US $2.05) per hal (a local measure of land; ninety decimals is equivalent to one hal) to leaseholders to drain water from their haor. However, some farmers pointed out that drying out the haor leads to water shortages and irrigation problems during the dry season and can increase the cost of crop production, as one respondent explained:

We were unable to plant crops in a timely manner due to prolonged waterlogging created by the leaseholders. For addressing the waterlogging problem, we had to negotiate and settle for drying out a waterbody as he placed a barricade to restrict our access and keep the water for fishing. Though we suffer from water crisis after drying out water bodies, we are bound to do to get rid of logged water so that we could cultivate our crops.

In-depth discussion with parents and private tutors revealed that sudden flash floods were undermining their children's education. Therefore, a group-based social learning process involving parents, teachers, and boatmen attempted to reduce drop-out rates by establishing regular ferry services to and from school.

3.2. Formal and quasi-formal institutional spaces and social learning processes

Empirical analysis of the qualitative data demonstrated that several learning platforms, such as public hearings, Ward Council (a sub-unit of the UP, usually consisting of two or three villages) meetings, monthly and emergency meetings, quarterly meetings, and co-committee meetings, were functioning at the formal and quasi-formal institutional levels. Such diverse learning arenas emerged in order to address the many challenges faced by local people and institutions in reducing their vulnerability to flash floods. Several aspects thus varied in terms of learning arenas, which included key actors, issues of reflective discussions, learning, and the community major concerns (). Like informal learning spaces, an example of key social learning that emerged in the formal institutional learning arenas was the community's desire to be self-reliant and reduce their dependency on external funding and assistance.

Table 3. Formal and quasi-formal institutional arenas and social learning process.

We identified three formal institutional learning arenas: UP and UDMC meetings, Ward Council meetings, and quarterly feedback meetings organised by NGOs. Of these, the latter two provided relatively more space for vulnerable community people to share their experiences and concerns. For example, in-depth conversations with key informants revealed that multi-stakeholder learning occurred at the Ward level that was generated explicitly through a shared understanding to establish a coordinated effort to protect community properties and manage relief items. Consequently, these learning platforms paved the way to procure the necessary resources from local governments.

At the local Union level, albeit limited, national rules and regulations did facilitate learning arenas. For example, following the guidelines outlined in the Standing Order on Disasters (SOD) (2019) and the Disaster Management Act (2012), the UDMC administered disaster management activities within the jurisdiction of the UP. The SOD clearly outlines the responsibilities of the UDMC in accordance with various phases of disaster management. For example, the rules and guidelines for relief distribution in the post-disaster phase highlight: i) assessing damage and needs of communities and distributing relief items on the basis of this and the state of emergency; ii) immediately collecting allocated cash from the Upazila (sub-district) relief fund and distributing it to provide emotional support and healing to families who had lost members; and iii) monitoring and ensuring transparency for the equitable distribution of relief items and humanitarian assistance (MoDMR, Citation2012, Citation2019). These formal institutional instructions function as guiding principles for participatory discussion in learning areas. Key stakeholders of the UDMC partake in participatory social learning processes that often promulgate new perspectives, ideas, and actions for flood risk management in response to the community's needs and demands.

It was evident from the data that the most common concern expressed at the formal institutional level was with reducing communities’ vulnerability to flash floods through preparedness and managing the adverse effects of flash floods through efficient and timely relief operations. The key lessons that emerged from these discussions included: i) anticipatory preparedness was required to arrange relief before the onset of flash floods; ii) relief packages needed to be culturally appropriate; iii) there was a need to enhance the financial and technical capacities of local institutions, and iv) coordination and partnership between institutions and community members was required in order to carry out effective response, evacuation, and recovery operations.

Collective consensus reached through the participatory learning process included: i) ensuring equity and justice in relief operations; ii) engaging multiple stakeholders (e.g. primary schools, religious leaders, local businessmen, and community volunteers) in preparedness, evacuation, and recovery operations; iii) prioritising the list of vulnerable groups to resolve conflicts and avoid overlap; and iv) maintaining international standards for relief items and being sensitive to cultural concerns, such as dietary restrictions. These learning outcomes were mostly endogenous, emerging from group interactions and first-hand experience with flash floods and preexisting knowledge of relief management activities. In these cases, instead of following the top-down, formalised procedures, an inherent bottom-up learning approach appeared as key to building awareness and implementing collective action. Clarifying this, one key informant, a manager of a local NGO office, stated:

We purchased parboiled rice from Satkhira. But local people did not like to eat parboiled rice. They preferred to eat atop chal [white rice]. They could not cook parboiled rice. Many villagers needed relief items distributed in 2017. Later, we decided not to purchase parboiled rice.

Another example of a joint undertaking was co-committee meetings, which involved parents, staff of local NGOs, members of the School Managing Committee, teachers, and boatmen. Our field data revealed that the primary concern here was the declining educational performance of the secondary-school children in the community. This issue was also a matter of discussion in the informal learning arenas discussed above. However, the modus operandi were different. In the case of informal learning spaces, parents sought to solve the problem on their own, while the quasi-formal co-committee preferred to spread the responsibility and burden among multiple stakeholders and institutions. For example, a co-committee decided to rent seven engine-driven boats, at BDT 1000 (US $12.42) per boat, for the secondary school children. A local NGO provided BDT 700 (US $8.69) and parents paid the rest of the rental cost. The committee also monitored the overall process to ensure the safety and security of the children during flooding.

3.3. Role of local institutions in adopting social learning, collective action, and their potential implications for disaster resilience

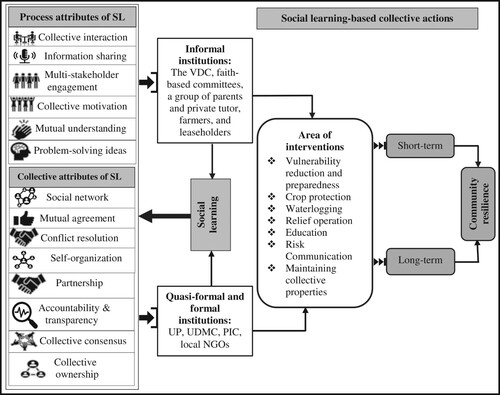

Based on our findings, as depicted in and , we trace out a set of collective process attributes that fostered social learning in the studied community. Through the process attributes (e.g. collective interaction and information sharing), social learning helped resolve conflicts, enhance partnerships, and reach collective consensus and mutual agreement. Such collective attributes of social learning helped local institutions identify a set of interventions for reducing risk and building resilience ().

Figure 2. A schematic diagram on the connections among social learning, local institutions, and collective action

There are some clear differences between the interventions carried out by these various institutions. First, the short- and long-term actions of some institutions (both formal and informal) are limited to specific areas, while others took action in multiple areas. This implies that certain institutions emerged to address specific issues. For example, empirical results of key informant and semi-structed interviews unearthed that the co-committee only took action on education-related issues, while the VDC took both short- and long-term actions to address issues involving vulnerability, improving communication systems, and protecting collective properties ().

Table 4. Social learning-based collective action in terms of local institutions.

Second, some interventions were found to be limited to formal institutions. For example, interviews with the members of the UDMC revealed that short- and long-term actions for risk communication and relief operation are carried out only by the UP, the UDMC, and NGOs. However, such actions were often carried out in collaboration with other formal and informal institutions. The key lesson drawn from such collaboration was recognising the benefits derived from sharing risk and responsibility among people and institutions. For instance, formal local institutions (i.e. the UDMC) maintain a social learning-based network to gather and disseminate flood-related information. To this end, the UDMC enacted several short-term measures in collaboration with other informal institutions, including using community resources (e.g. mosque megaphones) and social platforms (e.g. Facebook), and establishing a 24/7 control room and mobile response team in accordance with the national SOD. Utilising social networks, the UDMC also procured relief items from local traders for quick response to the flash floods in 2017.

Third, social learning facilitated self-organisation capacity and engaged multiple stakeholders in collective measures. For example, participants revealed that long-term strategies for the reduction of vulnerability (e.g. repairing roads and constructing bamboo bridges) were jointly implemented by the UP and the VDC; in particular, the UP provided the necessary resources while the VDC mobilised community members to engage in collaborative work. The construction of crop protection embankments was also an example of collective understanding and action. While the BWDB was responsible for financial and technical assistance, the engagement of multiple stakeholders – the UP, the PIC, officials of the BWDB, and farmers – in the collaborative work played a significant role in ensuring quality, accountability, and transparency. These collaborative efforts were essential to augmenting crop harvesting capacity and reducing transaction costs.

However, some pitfalls were also evident in the collaboration process. While risk-reduction measures enacted prior to the catastrophic 2017 floods resulted in significantly reduced property damage and loss of life, poor collaboration by the local political leaders hindered the relief distribution process and the implementation of flood management projects. Poor coordination was also observed between formal and quasi-formal institutions. Collaboration with non-government institutions, such as NGOs, volunteers, and local trader associations was only facilitated when a particular need emerged during the flash flood crisis.

4. Discussion

We set out to investigate the role of social learning and local-level institutions in enhancing resilience to flash floods in the wetland communities of northeastern Bangladesh. We draw three broad conclusions based on our findings: i) the diversity and flexibility of local-level institutions helps harness social learning from disaster shocks for building resilience; ii) institutional collaboration can facilitate social learning-based collective action; and iii) communities’ desire and willingness to be self-reliant led to the emergence of collective action for strengthening community resilience.

Catastrophic nature-triggered disasters create diverse opportunities for learning and change (Birkmann et al., Citation2008; Choudhury & Haque, Citation2018; Davidsson, Citation2020). Such opportunities can be captured when there is a diversity of institutions operating at the local level. While the strengths of diverse institutions are well established in community resilience and disaster resilience scholarship (Berkes, Citation2007; Folke et al., Citation2003), recent studies have revealed that diversity in institutions contributes to social learning as well (Johannessen & Hahn, Citation2013; O’Donnell et al., Citation2018). Notably, the connection among institutional diversity, social learning, and resilience is not yet well articulated in disaster and community resilience scholarship. Our findings help fill this gap by demonstrating with empirical evidence that the 2017 flash floods created numerous opportunities for social learning – different local institutions (formal, informal, and quasi-formal) created multiple local learning arenas for sharing the experiences and concerns of community members. Our findings further underscore that problems and issues discussed in each type of institution were varied.

Informal learning spaces are different compared to formal institutional learning arenas, such as UP and UDMC meetings. Flood-triggered learning spaces at the informal institutional level were more self-organised, whereas quasi-formal and formal institutional learning platforms followed structured and relatively inflexible institutional procedures. Whilst formal learning spaces had been operating following well-established institutionalised rules and regulations, reaching collective consensus to frame and design collective action was a key stepping stone in the decision-making process.

Climate change-triggered disasters impact communities in a manner that worsens multifarious problems, including social inequality, disease spread, and livelihood insecurity (Hutton & Haque, Citation2004; Wisner et al., Citation2004). It is asserted in the literature that ameliorating communities’ precarious situations often requires creative and collective problem-solving action that has community-wide implications for all community members (Adger, Citation2003; Pakmehr et al., Citation2020). We documented that a diversity of institutions facilitates addressing issues and problems from multiple sectors, such as livelihood, education, and health. For example, discussions conducted in informal learning arenas were by and large concerned with protecting collective properties and individual livelihoods, while issues related to managing disasters through relief, response, and evacuation were discussed chiefly in formal institutional arenas. Key knowledge, such as including new items like fireboxes and charger lights in relief packages and organising the delivery of supplies for pregnant mothers at shelter centres, played an essential role in mitigating flood-related vulnerability at the local community level. In this connection, Berkes (Citation2018) highlights that institutional diversity permits local level organisations to nurture multiple perspectives, values, and needs, which are important to enhancing knowledge, skills, and adaptive capacity (Koontz et al., Citation2015; Ostrom, Citation2005). Empirical results of our study affirmed that institutional diversity has created opportunities for nurturing diverse problem-solving ideas and knowledge at the local level.

Cross-level institutional collaboration is recognised as a critical component for generating community resilience (Berkes, Citation2017; Choudhury et al., Citation2019). In our study area, institutional collaboration facilitated social learning-based collective action for enhancing resilience. Our study documented that some informal and formal institutions were collaborating vertically and horizontally during the pre- and post-flood periods. In the wetland communities, a strong collaboration was instituted between formal institutions (e.g. the UP and UDMC) and informal institutions (e.g. faith-based institutions, volunteers, and community members) for disseminating flood-related information and taking collaborative measures to repair community-owned properties. A recent study on the dissemination of flood forecasting information and the evacuation during the 2017 Bangladesh flash floods reveals that collaborative actions executed by community-based organisations, volunteers, and local NGOs played key roles in lessening the vulnerability of flood-affected populations in northern Bangladesh (Sultana et al., Citation2020). These community-based organisations foster various collective capital at the local level, which are key to taking collective action in the face of uncertainty.

Collaborations among the UP, the UDMC, the PIC, the local office of the BWDB, and the Upazila office – which can be considered vertical collaboration – took place for ensuring financial and technical supports were received by the communities. For example, local level community-based organisations and institutions worked together to meet the human resource needs, to procure financial assistance, and to monitor the construction of crop protection embankments. However, a lack of needed collaboration was also evident among the BWDB, the Project Implementation Officer, volunteer groups, and NGOs. Factors that hampered collaboration included the lack of cash-flow supports, the political influence of key actors in decision-making processes, and a tendency to work as disparate sectors. Our findings further suggest that joint undertakings by informal and quasi-formal institutions were more flexible compared to formal learning arenas, which helped in identifying problems and finding possible solutions collectively. Flexibility in learning spaces, especially public hearings, Ward councils, and courtyard meetings generated more opportunities for vulnerable groups to share their experiences and concerns. Tran, James, and Pittock’s (2018) research on farmers in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta and Lumosi et al.'s (2019) study of several committees involved in Zambezi Basin management in Zambia documented similar findings.

We found that communities’ desire and willingness to be self-reliant led to the emergence of collective action for strengthening community resilience to disaster shocks. The role of collective agency and efficacy in collective action and self-organisation is widely expounded in the community and disaster resilience literature (Berkes & Ross, Citation2013; Brown & Westaway, Citation2011; Wilson, Citation2012 Our study underscores that such a shift toward ‘collective efficacy or agency’ was facilitated by the process of collective interaction, sharing, and multi-stakeholder participation. These attributes in turn have resulted in mutual agreement, partnership, and conflict resolution, and triggered a process of self-organisation. The collective attributes facilitated both formal and informal institutions in acting to achieve both short- and long-term goals toward strengthening community resilience. Similarly, several authors have argued that local-level institutions can mobilise and create these collective attributes through creating self-help groups (Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2004; Weingartner et al., Citation2017). Our empirical results from northeastern Bangladesh demonstrate that flash floods in the foothill communities have engendered such self-help groups (e.g. volunteers, faith-based groups, trader associations, and VDCs) for flash flood protection who had similar livelihood status, values, collective customs, and assumptions. These emergent groups performed pivotal roles in mobilising resources, disseminating flood-related knowledge, and implementing collective action by generating social networks and resources.

5. Conclusion

By examining the flash flood-prone wetland communities of northwestern Bangladesh, we found that local-level institutions create diverse arenas for social learning. Learning spaces emerged from collective concerns regarding reducing vulnerability and protecting collective properties. Our results reveal that while learning arenas generate context-specific social learning from flash flood experiences, the goal of such arenas as a whole is to foster social learning for building community resilience against flash floods. To this end, learning arenas within local-level formal and informal institutions create opportunities for social interaction, deliberation, problem solving, and the generation of collective knowledge and action.

Our empirical study of Sunamganj District communities reveals that persistent institutional diversity at the local level is key to engaging multiple stakeholders in social learning. It is evident that to create a resilient community, local institutions require fostering various collective attributes, including collective ownership, shared understanding, social networks, partnerships, and collaboration. Utilising these properties, local-level institutions strengthen their capacity to translate social learning into collective action. However, several key constraints hinder the social learning process and collective action, including poor collaboration among local institutions and community members.

Our results suggest several overall policy recommendations. First, institutional diversity is key to nurturing diverse knowledge and formulating decisions for collective action. Second, local-level institutions are a repository of knowledge and must thus be encouraged to more systematically apply knowledge of past flood experiences to disaster management and vulnerability-reduction initiatives. Institutional culture may also create constraints for social learning. Removing social barriers and strengthening local institutions are thus essential for fostering social learning, as greater flexibility results in more creative and effective problem-solving. Future studies, therefore, should investigate how persistent barriers constrain social learning and the process of its transformation into collective action.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adger, W. N. (2003). Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Economic Geography, 79(4), 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2003.tb00220.x

- Agrawal, A. (2010). Local institutions and adaptation to climate change. In R. Mearns & A. Norton (Eds.), The social dimensions of climate change: Equity and vulnerability in a warming world (pp. 173–197). The World Bank.

- Ahmed, R. M., Rahaman, K. R., Kok, A., & Hassan, Q. K. (2017). Remote sensing-based quantification of the impact of flash flooding on the rice production: A case study over Northeastern Bangladesh. Sensors, 17(10), 2347. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17102347

- Armitage, D., Marschke, M., & Plummer, R. (2008). Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Global Environmental Change, 18(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.07.002

- Assuah, A., & Sinclair, A. J. (2019). Unraveling the relationship between collective action and social learning: Evidence from community forest management in Canada. Forests, 10(6), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10060494

- Azad, M. A. K. (2020). The role of social learning in enhancing community resilience and recovery from flash floods in Sunamganj, Bangladesh [Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba]. https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/xmlui/handle/1993/35247

- Baird, J., Plummer, R., Haug, C., & Huitema, D. (2014). Learning effects of interactive decision-making processes for climate change adaptation. Global Environmental Change, 27(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.019

- Benson, D., Lorenzoni, I., & Cook, H. (2016). Evaluating social learning in England flood risk management: An “individual-community interaction” perspective. Environmental Science and Policy, 55, 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.05.013

- Berkes, F. (2007). Understanding uncertainty and reducing vulnerability: Lessons from resilience thinking. Natural Hazards, 41(2), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-006-9036-7

- Berkes, F. (2009). Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(5), 1692–1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.001

- Berkes, F. (2017). Environmental governance for the anthropocene? Social-ecological systems, resilience, and collaborative learning. Sustainability, 9(7), 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071232

- Berkes, F. (2018). Sacred ecology (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Berkes, F., & Ross, H. (2013). Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Society and Natural Resources, 26(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2012.736605

- Birkmann, J., Buckle, P., Jaeger, J., Pelling, M., Setiadi, N., Garschagen, M., Fernando, N., & Kropp, J. (2008). Extreme events and disasters: A window of opportunity for change? Analysis of organizational, institutional and political changes, formal and informal responses after mega-disasters. Natural Hazards, 55(3), 637–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-008-9319-2

- Brown, K., & Westaway, E. (2011). Agency, capacity, and resilience to environmental change: Lessons from human development, well-being, and disasters. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 36(1), 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-052610-092905

- Choudhury, M. U. I. (2015). Wetland-community resilience to flash flood hazards (Bonna) in Sunamganj district, Bangladesh [Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba]. http://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/xmlui/handle/1993/30998

- Choudhury, M. U. I., & Haque, C. E. (2016). “We are more scared of the power elites than the floods”: Adaptive capacity and resilience of wetland community to flash flood disasters in Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 19, 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.08.004

- Choudhury, M. U. I., & Haque, C. E. (2018). Interpretations of resilience and change and the catalytic roles of media: A case of Canadian daily newspaper discourse on natural disasters. Environmental Management, 61(2), 236–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0980-7

- Choudhury, M. U. I., Haque, C. E., Nishat, A., & Byrne, S. (2021). Social learning for building community resilience to cyclones: Role of indigenous and local knowledge, power, and institutions in coastal Bangladesh. Ecology and Society, 26(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12107-260105

- Choudhury, M. U. I., Uddin, M. S., & Haque, C. E. (2019). “Nature brings us extreme events, some people cause us prolonged sufferings”: The role of good governance in building community resilience to natural disasters in Bangladesh. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(10), 1761–1781. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1513833

- Collier, C. G. (2007). Flash flood forecasting: What are the limits of predictability? Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 133(622), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.29

- Collins, K., & Ison, R. (2009). Jumping off Arnstein’s ladder: Social learning as a new policy paradigm for climate change adaptation. Environmental Policy and Governance, 19(6), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.523

- Cook, B. R., & Overpeck, J. T. (2019). Relationship-building between climate scientists and publics as an alternative to information transfer. WIRES Climate Change, 10(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.570

- Cornes, I. C., & Cook, B. R. (2018). Localising climate change: Heatwave responses in urban households. Disaster Prevention and Management, 27(2), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-11-2017-0276

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Cutter, S. L., Barnes, L., Berry, M., Burton, C., Evans, E., Tate, E., & Webb, J. (2008). A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Global Environmental Change, 18(4), 598–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013

- Dale, A. (2013). Agency: Individual “fit” and sustainable community development. Community Development Journal, 49(3), 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bst055

- Davidsson, Å. (2020). Disasters as an opportunity for improved environmental conditions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 48, 101590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101590

- Ensor, J., & Harvey, B. (2015). Social learning and climate change adaptation: Evidence for international development practice. WIRES Climate Change, 6(5), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.348

- Flood Forecasting and Warning Centre (FFWC). (2017). Annual flood report 2017. http://www.ffwc.gov.bd/images/annual17.pdf

- Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., & Rockström, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society, 15(4), 20. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.116.180406

- Folke, C., Colding, J., & Berkes, F. (2003). Synthesis: Building resilience and adaptive capacity in social–ecological systems. In F. Berkes, J. Colding, & C. Folke (Eds.), Navigating social-ecological systems (pp. 352–387). Cambridge University Press.

- Gupta, J., Termeer, C., Klostermann, J., Meijerink, S., van den Brink, M., Jong, P., Nooteboom, S., & Bergsma, E. (2010). The adaptive capacity wheel: A method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environmental Science and Policy, 13(6), 459–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2010.05.006

- Hutton, D., & Haque, C. E. (2004). Human vulnerability, dislocation and resettlement: Adaptation processes of river-bank erosion-induced displacees in Bangladesh. Disasters, 28(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2004.00242.x

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2012). Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. Cambridge University Press.

- Johannessen, Å, & Hahn, T. (2013). Social learning towards a more adaptive paradigm? Reducing flood risk in Kristianstad municipality, Sweden. Global Environmental Change, 23(1), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.009

- Kamal, A. S. M. M., Shamsudduha, M., Ahmed, B., Hassan, S. M. K., Islam, M. S., Kelman, I., & Fordham, M. (2018). Resilience to flash floods in wetland communities of northeastern Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, 478–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.06.011

- Keen, M., Brown, V. A., & Dyball, R. (2005). Social learning in environmental management: Towards a sustainable future. Routledge.

- Khan, S. M. M. H. (2011). Participatory wetland resource governance in Bangladesh: An analysis of community-based experiments in Kakaluki Haor (Doctoral dissertation, University of Manitoba). https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/xmlui/handle/1993/4952

- Koontz, T. M., Gupta, D., Mudliar, P., & Ranjan, P. (2015). Adaptive institutions in social-ecological systems governance: A synthesis framework. Environmental Science and Policy, 53, 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.01.003

- Lebel, L., Grothmann, T., & Siebenhüner, B. (2010). The role of social learning in adaptiveness: Insights from water management. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 10(4), 333–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9142-6

- Lei, Y., Yue, Y., Zhou, H., & Yin, W. (2014). Rethinking the relationships of vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation from a disaster risk perspective. Natural Hazards, 70(19), 609–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0831-7

- Lumosi, C. K., Pahl-Wostl, C., & Scholz, G. (2019). Can ‘learning spaces’ shape transboundary management processes? Evaluating emergent social learning processes in the Zambezi basin. Environmental Science and Policy, 97, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.04.005

- Mancini, J. A., Bowen, G. L., & Martin, J. A. (2005). Community social organization: A conceptual linchpin in examining families in the context of communities. Family Relations, 54(5), 570–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00342.x

- Meinzen-Dick, R., DiGregorio, M., & McCarthy, N. (2004). Methods for studying collective action in rural development. Agricultural Systems, 82(3), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2004.07.006

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Miller, T. R., Baird, T. D., Littlefield, C. M., Kofinas, G., Chapin, F. S., III., & Redman, C. L. (2008). Epistemological pluralism: Reorganizing interdisciplinary research. Ecology and Society, 13(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02671-130246

- Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief (MoDRM). (2012). The disaster management act 2012. Dhaka: Ministry of Disaster management and Relief, Dhaka. https://modmr.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/modmr.portal.gov.bd/law/e2aebb6e_1b34_41f0_9b6f_36fda6db8fdb/Diaster-Management-Act-2012.pdf

- Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief (MoDRM). (2019). Standing order on disasters 2019. Dhaka: Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief, Dhaka. https://modmr.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/modmr.portal.gov.bd/policies/7a9f5844_76c0_46f6_9d8a_5e176d2510b9/SOD%202019%20_English_FINAL.pdf, accessed on 5 November 2020

- Neuman, W. L. (2014). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Pearson Education Limited.

- O’Donnell, E. C., Lamond, J. E., & Thorne, C. R. (2018). Learning and action alliance framework to facilitate stakeholder collaboration and social learning in urban flood risk management. Environmental Science and Policy, 80, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.10.013

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press.

- Pakmehr, S., Yazdanpanah, M., & Baradaran, M. (2020). How collective efficacy makes a difference in responses to water shortage due to climate change in southwest Iran. Land Use Policy, 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104798

- Purdon, M. (2003). The nature of ecosystem management: Postmodernism and plurality in the sustainable management of the boreal forest. Environmental Science and Policy, 6(4), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1462-9011(03)00064-9

- Rahman, H. M. T., Robinson, B. E., Ford, J. D., & Hickey, G. M. (2018). How do capital asset interactions affect livelihood sensitivity to climatic stresses? Insights from the Northeastern floodplains of Bangladesh. Ecological Economics, 150, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.006

- Rahman, R., & Salehin, M. (2013). Flood risks and reduction approaches in Bangladesh. In R. Shaw, F. Mallick, & A. Islam (Eds.), Disaster risk reduction approaches in Bangladesh (pp. 65–90). Tokyo: Springer Japan.

- Reed, M. S., Evely, A. C., Cundill, G., Fazey, I., Glass, J., Laing, A., Newig, J., Parrish, B., Prell, C., Raymond, C., & Stringer, L. C. (2010). What is social learning? Ecology and Society, 15(4), https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03564-1504r01

- Rist, S., Chidambaranathan, M., Escobar, C., Wiesmann, U., & Zimmermann, A. (2007). Moving from sustainable management to sustainable governance of natural resources: The role of social learning processes in rural India, Bolivia and Mali. Journal of Rural Studies, 23(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2006.02.006

- Rodela, R. (2011). Social learning and natural resource management: The emergence of three research perspectives. Ecology and Society, 16(4), 30. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04554-160430

- Rodela, R. (2013). The social learning discourse: Trends, themes and interdisciplinary influences in current research. Environmental Science and Policy, 25, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.09.002

- Steyaert, P., Barzman, M., Billaud, J. P., Brives, H., Hubert, B., Ollivier, G., & Roche, B. (2007). The role of knowledge and research in facilitating social learning among stakeholders in natural resources management in the French atlantic coastal wetlands. Environmental Science and Policy, 10(6), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2007.01.012

- Strauss, A. (1978). A social world perspective. Creating Sociological Awareness, 1, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203794487-18

- Sultana, P., Thompson, P. M., & Wesselink, A. (2020). Coping and resilience in riverine Bangladesh. Environmental Hazards, 19(1), 70–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2019.1665981

- Tàbara, J. D., Dai, X., Jia, G., McEvoy, D., Neufeldt, H., Serra, A., Werners, S., & West, J. J. (2010). The climate learning ladder. A pragmatic procedure to support climate adaptation. Environmental Policy and Governance, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.530

- Tran, T. A., James, H., & Pittock, J. (2018). Social learning through rural communities of practice: Empirical evidence from farming households in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 16, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.11.002

- Uddin, M. S., Haque, C. E., & Khan, M. N. (2020b). Good governance and local level policy implementation for disaster-risk-reduction: Actual, perceptual and contested perspectives in coastal communities in Bangladesh. Disaster Prevention and Management, 30(2), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-03-2020-0069

- Uddin, M. S., Haque, C. E., Walker, D., & Choudhury, M. U. I. (2020a). Community resilience to cyclone and storm surge disasters: Evidence from coastal communities of Bangladesh. Journal of Environmental Management, 264, 110457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110457

- Weingartner, L., Pichon, F., & Simonet, C. (2017). How self-help groups strengthen resilience: A study of Tearfund’s approach protracted crises in Ethiopia. Overseas Development Institute. https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/11625.pdf

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Earning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wilson, G. A. (2012). Community resilience and environmental transitions. Earthscan.

- Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2004). At risk: Natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters. Routledge.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. SAGE.

- Young, O. R. (2002). The institutional dimensions of environmental change: Fit, interplay, and scale. The MIT Press.