ABSTRACT

The literature on disaster management highlights that communities that mobilise and integrate a range of local capacities, resources and knowledges tend to fare best. This demonstrates the critical, yet underappreciated, role these attributes play in disaster management. This paper contributes to scholarship by examining the conditions, values and practices for building effective cross-sector ties. Importantly, it highlights the need for decentralised, cross-sector supports for building community recovery (increasingly known as ‘polycentric’ disaster governance). It reports on the results of a local community engagement program after country-wide bushfires in Australia (2019–20). Participatory action planning is used in two regional communities and ethnographic methods are employed to glean the experience and learnings from local recovery workers (n = 5). Findings support calls for embracing and linking diverse capacities post-disaster to boost social capital and invest in local knowledges. Focus is given to bonding, bridging and linking capital, the importance of capacity ‘redundancy’, and the role of trust, serendipity, and ‘culture brokers’ in identifying, mobilising and integrating diverse capacities and resources to support community-centered disaster recovery. Findings are used to fine-tune understandings of cross-sector ties that enable communities to move beyond a passive stance.

Policy highlights

While emergency managers and authorities are specially trained in disaster management, effective recovery outcomes can be achieved through building cross-sector collaborations.

Local communities ought to be seen as best positioned to make decisions about, and work toward, outcomes that have local benefit, especially by relying on local capacities and capitals.

In addition to working with communities to achieve outcomes, emergency managers and authorities ought to play a role in incentivising, funding, training and rewarding communities.

Government-funded but locally implemented programs, such as the one reported on here, demonstrate how incentivising, funding, training and rewarding can be used to these ends.

Introduction

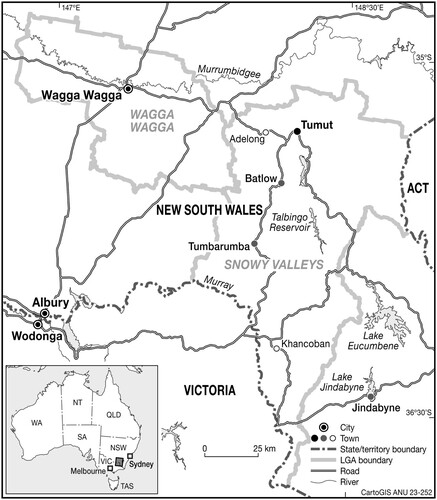

As the projection and incidence of disasters increase globally, authorities, emergency managers and communities are more engaged than ever in disaster management. Developments in this space over the past five decades have tracked broader paradigmatic changes reshaping the delivery of public services (Levin et al., Citation2022). This trajectory includes the shift from the welfare state to neo-liberalised state services and, more recently, to polycentric approaches (Hermansson, Citation2016). A form of decentralised adaptive governance (Koivisto & Nohrstedt, Citation2017), a polycentric approach combines diverse, often marginalised actors to eschew highly concentrated and hierarchical processes (Bahadur & Tanner, Citation2014; Ostrom, Citation2014). Such approaches stress dispersed, multilayered actors collaborating to build equitable local recovery, with scholarship now increasingly directed towards how this is achieved (Tselios & Tompkins, Citation2017). In this article, we contribute to this scholarship by describing a polycentric engagement program in Australia that aimed to place community at the centre of bushfire recovery. We highlight the importance of locally driven responses by diverse groups, their social capital resources, and the mobilisation of their knowledges and capacities to counterbalance top-down approaches (Sanderson, Citation2019c). Noting the role of local networks and capitals for achieving positive outcomes, we ask: what are the conditions that build effective cross-sector collaborations in disaster recovery? Our empirical focus is southwest New South Wales (NSW), Australia, a regional area with little history of large-scale climate-induced disaster, such as the 2019–2020 Australian bushfires.

What set these fires apart was their extent compared to prior disasters and the public criticism of relief efforts (see Lockie, Citation2020).Footnote1 24 million hectares burned between July 2019 and March 2020, leading to suggestion that greater collaboration by authorities, emergency managers and communities was needed (Pyne, Citation2021). Ostrom (Citation2014) argues that polycentrism is advantageous as it promotes experimentalism among actors who seldom work together and builds strong commitments for addressing vulnerability. A significant focus in the polycentric disaster management literature is the ability for countries with weak or under-resourced state structures to manage natural hazards (Jana & Singh, Citation2022). With climatic change associated with the Anthropocene growing, the governance challenges these threats pose are now experienced beyond low-income countries (Levin et al., Citation2022). Such developments have led to questions about management strategies across a broader geography and calls for polycentric assemblages of state and non-state actors in low- to high-income countries (Fjäder, Citation2021; Sanderson, Citation2017, Citation2020). This includes Australia, an affluent liberal democracy currently contending with the effects of climate related disasters. Studies have shown how communities that effectively mobilise and integrate diverse knowledges and capacities tend to fare best (Gaillard, Citation2015). Indeed, cross-sector collaborations prioritising the local have a track record of enabling effective and inclusive management (Fraser et al., Citation2021). Our research furthers understandings of how recovery can be decentralised at the local level in countries such as Australia through polycentrism.

Methodologically, we employed participatory action planning with two case study communities involved in the Resilient Towns Initiative (RTI) to design and build local recovery, and also used ethnographic methods among local recovery workers (n = 5) to track and understand the polycentric networks and conditions that best support locally led recovery. RTI was a 21-month project undertaken by researchers, local and state government authorities, and representatives of two not-for-profits (NFPs) working to support bushfire recovery in southwestern NSW. Throughout this article, the role of social capital in disaster management is examined, now a significant focus of research (Aldrich, Citation2019; Sadri et al., Citation2018), to demonstrate useful pathways to identify the conditions under which effective cross-sector ties are created and maintained. After outlining our case study, we provide an overview of a set of disaster management workshop activities devised at the community level and embraced by cross-sector actors to improve community safety and connectivity, spurred on by strong social capital. This includes interpersonal networks (bonding ties), external networks (bridging ties) and people in positions of power (linking ties) that act as the basis through which polycentric governance can develop (for a review, see Meyer, Citation2018). We extend the utility of these ties in polycentric disaster management by examining the work of ‘culture brokers’ operating across networks, sector and institutional divides (i.e. operating across different working cultures) to create strong and mutually understandable connections. A description of these workshop activities leads us to reflect on the importance of trust and serendipity in building cross-sector ties.

Theoretically, our research is informed by interorganisational relations theory (e.g., Schruijer, Citation2020), observing the properties and patterns of diverse relationships through the process of working together (Ebers, Citation2015). This is helpful for understanding how community-oriented ‘collaborations’, premised on bottom-up recovery and built on trust, differ from top-down government ‘partnerships’. Such a distinction challenges the dichotomy between ‘community’ and ‘professional’ knowledges and capacities and, we argue, is instructive for understanding how polycentric assemblages promote ‘nodal’ governance of natural hazards. Findings demonstrate the importance of embracing and linking diverse capacities and the need for policymakers and authorities to view communities as capable and knowledgeable. Findings are used to fine-tune understandings of cross-sector ties that enable communities to move beyond a passive stance to engage in the ‘rowing’ and the ‘steering’ (Osborne & Graeber, Citation1992) of disaster management. In this way, the paper contributes to understandings of two issues identified in the disaster management literature over recent decades: first, tensions over which knowledges and resources are mobilised (Berchtold et al., Citation2020; Sanderson, Citation2017) and, second, what the best practices are for integrating these knowledges and capacities to ensure the widest benefit (see Wisner et al., Citation2014). We conclude with three practitioner recommendations for building effective cross-sector, polycentric collaborations, and four policy recommendations for improving recovery generally.

Background

Predicaments in recovery after the 2019–2020 bushfires

RTI was a university-led, locally implemented initiative (2021–23) that originated from cross-sector collaboration between researchers, two NFPs, and government personnel involved in bushfire recovery in the Snowy Valleys local government area (). Almost half the 9000 square kilometre area was burnt as part of the 2019–20 Australian bushfires. These fires impacted 5.3 million hectares of NSW, or more than 6% of the state (DPS, Citation2020), and formed part of a bushfire system covering much of the country. In response, the Australian government provided AUD$280 million (US$188 million) in disaster payments nationally, deployed mobile service centres to 90 locations, and mobilised 362 Emergency Reserve staff (Services Australia, Citation2020). In NSW, the state government mobilised the Bushfire Customer Care program to provide direct local support to fire-affected regions and granted over AUD$600 million (US$392 million) in relief and recovery projects (2020–2024) aimed at local economic and bushfire recovery (NSW Government 2024), which included RTI. Community-oriented disaster management, whereby communities work in concert with government, emergency managers and NFPs, is recognised as the gold standard (Fernandez & Ahmed, Citation2019). However, rarely is this standard achieved in practice, hence the implementation of RTI, due to inequities in how responsibilities of disaster management are conceived when authorities and emergency managers take the lead (Syamsidik et al., Citation2021). In Snowy Valleys, local and state government and NFPs were the main recovery actors. Government-led and NFP-supported assistance illustrates a common approach to disaster management in Australia, with government ‘steering’ and NFPs ‘rowing’. This is reflected internationally (Vallance, Citation2015), particularly in high-income countries, with spontaneous mobilisations of citizens a critique against top-down approaches (e.g. the Cajun Navy after disasters in the USA).

RTI supported several Snowy Valleys communities to design and implement recovery, including in the two townships explored here, anonymised as Town One and Two. Town One (population <300) comprised landholders engaged in winemaking, cattle grazing, and orcharding. Given its population size and rurality, sustained attention on this area was unprecedented, meaning RTI was warmly welcome to support a community used to living off the land. Town Two (population <1500) is known historically for gold mining (ca. 1850s) and participation in forestry and orcharding. Since the closure of local industry, reliance on state welfare has increased, leading to a mindset that government and business would protect the town’s economic security and that emergency services would manage hazards. The expansion of forestry plantations prior to the fires, led to increased local employment opportunities but was seen as exacerbating bushfire severity. The period after was shaped by the town’s hasty evacuation experience, highlighting to residents a lack of coordinated disaster management. Understandably, this affected the uptake of recovery programs. Given these experiences, we noted in the literature the relevance of trust and serendipity (defined below) for building cross-sector ties (Awotona, Citation2016; Browne, Citation2015; Eadie & Su, Citation2018; Fjäder, Citation2021; Hamdi, Citation2010; Ostrom & Walker, Citation2003). These qualities are often taken for granted in research on disaster management but, we argue, are useful for embracing and responding to the ambiguities of post-disaster recovery (Hamdi, Citation2013, p. 135).

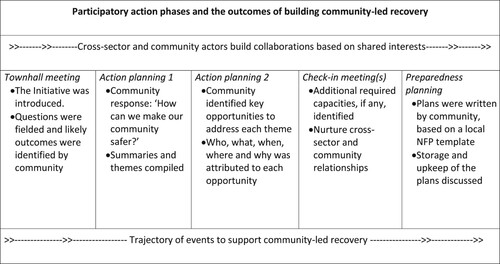

The focus of community recovery activities

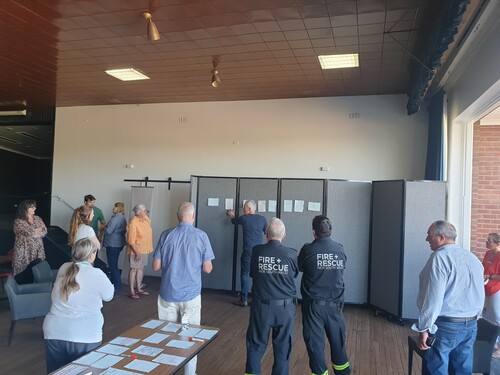

The activities supported by RTI included a series of public workshops where residents were encouraged to curate recovery processes and integrate diverse knowledges, skills and participation into localised recovery outcomes (). The theme unifying these events was the deliberately simple question, ‘How can we make our communities safer?’ This focus enabled participants to move beyond discussing the specifics of their bushfire response and the immediate recovery period, and instead to dwell on their collective ambitions for longer-term recovery and strength in moving forward to realise their aspirations for a better tomorrow. The event series was co-designed by RTI and self-selecting residents (n = 10–12 in each town) who expressed interest at a first Town Hall meeting. Participation was supplemented by engaging with typically under-represented cohorts (n = 5–10 people in each town) and inviting them to subsequent events to ensure their voices were heard. The number of participants at each event fluctuated. However, an inclusive ethos was embraced that stressed inclusion. Project newsletters were shared on social media to widely publicise project developments. Workshops comprised the implementation of a series of recovery workshop activities. The research component of the project, explored below, dealt with the conditions for building and maintaining cross-sector collaborations in the context of community-centred polycentric disaster management.

Research methods and materials

We used participatory action planning and ethnography that was conducted at each stage of workshop activities. Ethics approval was obtained (UNSW HREC, HC210846). Opt-out consent was practiced (n = 0). Mental health practitioners were present at events. Participatory action planning, via the World Café method (e.g. Wates, Citation2014), was used during workshop activities 1 to 3 to tease out what was important to participants when designing recovery. Participatory action methodologies such as this position communities as fully fledged contributors (Lenette, Citation2022), foregrounding their experience, knowledge and ambitions to guide recovery. Moving around the room to hear individual or group-devised ideas for recovery often generated new thinking among attendees. Such a methodology is premised on the principle of experimentalism and asserts that people are inherently resourceful and innovative and should lead planning efforts in concert with internal and external actors, thereby creating opportunities for discovery (Hamdi & Goethert, Citation1997; Sanderson, Citation2019b).

Ethnography (observations and interviews) was used to track the journey from idea generation to development, and the role played by different cross-sector actors involved in RTI (e.g. government, academic or NFP). Ethnography involves understanding a community by participating in its members’ lives: observing, interviewing, and documenting people’s experiences, perspectives, and networks (Campbell & Lassiter, Citation2015). Authors attended workshop activities, were introduced to attendees (n = 6–40 per event) and observed each activity in the series. Observations comprised of making space for attendees to participate uninterrupted in events, followed by open-ended, unintrusive questions to each table group (including: ‘What are you discussing’ and ‘What ideas have you come up with?’). Shorthand notes were made in situ about who was in attendance, the range of ideas that were generated, the general tenor of discussions, and the relationship dynamic between attendees. Notes were later extended and expanded upon through individual author reflections, and then collated by author 1.

Key informant interviews were conducted by the first and second authors at two stages (the beginning and end of the project) with the RTI team members (n = 5, P1–P5). Informed consent was obtained from each interviewee. Open-ended interview questions included: ‘What is needed to build community-centred recovery in this region', ‘What role can cross-sector actors play', ‘What would success look like', and ‘What barriers currently exist'. Stage 1 interviews were conducted in cafes or offices. Stage 2 interviews were conducted online via MS Teams. Each interview ranged from 1 to 1.5 h, was voice recorded and later transcribed. Stage 1 interviews were conducted to obtain interviewees’ baseline thinking, Stage 2 interviews comprise the corpus of data used in this paper. Participatory action planning and ethnography enabled the authors to nurture new and existing connections in each township, to understand the characteristics of each locality, to explore how these related to recovery experiences, and the role of cross-sector actors in this (Browne, Citation2015).

Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six phases of thematic analyses were followed. After data compilation and familiarisation, initial codes relevant to the research questions were compiled by author 1. Themes were developed based on what we identified in the data pertaining to community-centred recovery ambitions, polycentric governance, and cross-sector supports (i.e. the importance of trust, partnerships, collaborations and serendipity). These were elaborated on through authors 1–3 meeting regularly during data analysis to discuss themes in detail. A codebook was developed by author 1 and then data coding and analysis was conducted using NVivo (v12.0.0.71, Lumivero).

Results

The importance of locally owned and informed approaches

At the first two activities, participants (n = 20–40 per event) sat in small self-selecting groups. Tables were encouraged to write down ideas to the focus question on community safety, with an emphasis on quantity over quality. Ideas were then voted on, with the ones receiving the most votes shortlisted (). Ideas ranged from curbing crime and littering to addressing traffic concerns, youth disengagement, revitalising town infrastructure, and identifying ways to increase residents’ involvement in emergency management. The use of cards meant that everyone – from the loudest to the quietest – had equal means to present their ideas. Shortlisted ideas were discussed at subsequent events, with the ones receiving sustained attention then pursued at events 3–5. At event 3, participants identified the who, what, when, where, and why for each idea, making them into collective projects. At event 5, participants weaved these projects into community preparedness plans that set out how these projects assisted in managing community risk and safety in the region.

Across the projects, a ‘cluster’ approach was taken to building effective cross-sector collaborations to provide coordinated and targeted support (see Sanderson, Citation2017 for a review). Each actor (the ‘who’) was understood as having something to contribute. There was a focus on linking the networks and resources of RTI members and townspeople to develop local relations and resources. As one interviewee (P3, Recovery Worker, NFP sector) reflected:

It’s about never being in the same position again. How do we not go through that ever again? RTI was a chance for our town to be better prepared by coming together to exchange ideas, build projects and learn from each other through doing. It’s about working out how we either find resources or let people know how to develop them. It ended up evolving to give so much more. Yeah, learning from everybody in RTI and in town has been phenomenal.

Community sentiment in both towns stressed that to understand their disaster journey and recovery aspirations, one needed to be from these towns. Indeed, residents lamented the lack of local knowledge held by state-based professional service providers during the fires pertaining to local routes through the town and sources of water for fighting fires, which resulted in operational delays. This lack of trust in the ability of professional services to adequately assist communities in their environs, and their failure to sufficiently engage local people to fill this knowledge lacuna, constituted a significant socio-cultural context that shaped local people’s assessments of the response phase.Footnote2

Trust in external support, and satisfaction with their endeavours, has been shown to play an important role in communities feeling supported and resourced (Eadie & Su, Citation2018). Trust is the glue that binds together social networks and provides coherence to societal processes and services, including in disaster management (Broch-Due & Ystanes, Citation2016). However, the way disasters are managed can chip away at trust. Internationally, for example, local government in the Philippines reported feeling bypassed by NGOs working directly with the community following Typhoon Haiyan (Sanderson & Delica Willison, Citation2014). Further, after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, local government complained about feeling ‘like strangers in their own city’ (Sanderson, Citation2019a, pp. 1–2). These and other examples demonstrate the need for multi-sector and community-centred collaborations (US National Research Council, Citation2011). Following the 2019–20 fires, Snowy Valley residents’ satisfaction with authorities was among the lowest in NSW (Jetty, Citation2021).Footnote3 In towns where industrial decline has occurred (Town Two) and formal emergency responses lack community input (Town One), leading to operational delays and miscommunications, it is easy to see why satisfaction wanes after disaster.

Building trust is important. These communities have had lots of services come in and out. People said during the RTI events that what they liked was that we didn't come in, do our thing, and leave. We've come back regularly per the schedule of events and, as people from the region ourselves, we're going to be here. We didn't just talk about the disaster. We talked about needs and so on, and gave them some little wins around those needs quickly through action planning activities and the development of recovery ambitions. (P2, Recovery Worker, NFP sector)

Polycentric arrangements not only help to develop trust, as explored in the next section, they challenge the application of top-down metrics used to ‘measure’ a community’s capacity and readiness to manage disasters. Notably, Ostrom and others have examined how long-term, mutually beneficial decisions can jointly be made by communities without externally imposed, top-down or centralised authorities, lending credibility to decentralised management (Ostrom & Walker, Citation2003).

Reciprocity of ideas based in trust and cooperation were also highlighted by interviewees. RTI’s series of engagement activities allowed residents to consider the importance of local planning and the adaptive, experimental nature of polycentricity. Placing communities at the table with government, emergency managers, NFPs and technical experts enabled communities to contribute to how safety is managed, especially through drawing on their experiences of living and working in their community.

They’ve heard what we’re selling before. They want to know what we’re doing differently. It’s not just us getting up there and saying, “We’re really sorry this has happened and now we’ll try and help you.” I’m saying, “Look, it’s happened, we can’t do anything about it, but what we can do [through RTI is] to try and make it better.” You know, “What can we do together practically that is going to help you?” That’s really where I’m coming from. (P5, RTI Project Manager)

Practical undertakings instead of offering solutions were in this way held up as being important. To this end, Vallance (Citation2015) makes a distinction between residents participating in activities (i.e. the ‘substance’ of recovery) and their participation in decision-making (i.e. the ‘process’ of recovery governance). The distinction is useful for understanding the relationship between ‘“token” forms of participation and a similarly “token” recovery’ (Vallance, Citation2015, p. 1287). It stresses the need to understand what success looks like to make equitable the roles and responsibilities of recovery actors.

Serendipitous cooperation over recovery metrics

The region in which Town One is located is characterised in resilience frameworks as possessing low capacity for disaster management, while Town Two is deemed to have moderate capacity.Footnote4 Scores were based on assessments of each town’s coping capacity (the resources and skills available to the community and other organisations) and adaptive capacity (the processes that enable adjustment via education and adaptation). The development of our community engagement series confirmed that top-down measures typically pay little attention to the socio-cultural components of a community’s recovery (see, e.g., Browne, Citation2015). Universalist ideas about successful recovery are instead heralded as key indicators of recovery, often premised on ‘the psychological characteristics of individuals, the composition of their social networks, the local institutions and resources available to communities, [and] the will and work of political leaders’ (Browne, Citation2015: xi). When local factors are referenced in recovery indicators under signs such as social character, community capital, social and community engagement or capacity for self-organising, scant attention is actually paid to how local factors and conditions contribute to disaster management (i.e. through sustained community engagement, research, and support). This demonstrates the utility of ethnographic methods in identifying the ways in which local knowledge and capacity contributes to response and recovery.

A significant finding of prior research is the importance of serendipity in recovery initiatives at local levels. The intentional use of serendipity is drawn from action planning’s menu of approaches (Hamdi & Goethert, Citation1997), which along with fostering local ownership, emphasises starting points, not end states (drawing on the work of Robert Chambers), and impartial (not complete) knowledge. Participant 1 reflected on this when discussing the need to pair multiple sets of knowledges when working with communities and broad stakeholders when designing and supporting disaster recovery:

The approach among government has always been: have a problem, solve problem, move on. So, to actually get my head around a serendipitous approach—it was really difficult for me because I've been so process driven in my career and, you know, focussed on how an outcome is measured. (P1, Recovery Worker, Government sector)

RTI’s intention was to deliberately bring together sets of knowledges that were usually kept distinct or not mobilised around disaster issues, noting that the 21-month project would eventually end and that a motivated, close-knit network of residents would continue locally led initiatives. A key focus of the initiative was recognising the value of serendipity and the innovation it encouraged and generated.

Now, I think the best kind of engagement is when you don't have an outcome expectation. As a team, RTI spoke about this many times, especially around the phrasing of how communities can be safer. We're workshopping what's important to them. It's not what's important to us [as government personnel]. It's what's important to them. How they see their communities. (P1)

Serendipity was fostered by bringing people together, both in established networks and across networks, and then by creating opportunities to share experiences and ideas, with a focus on including people who were not normally part of decision-making forums (e.g. youth, people engaged in childcare, people living in isolated locations, and so on). Openness and trust-building were used to both encourage and explore ways to change local participation in idea development and decision-making about disaster recovery by people with a deep understanding of local conditions, local ambitions, and local knowledges. While common themes focused on the importance of the ‘local’, different sub-themes emerged for each town. For residents of Town One, community connectedness, access to information, practical skills-building, maintaining critical infrastructure, and promoting safe spaces for refuge (e.g. the townhall) were identified as important. In Town Two, a community preparedness plan, access to information, a seat at the table to work with emergency services and government organisations, and additional supports for youth and volunteers, were highlighted.

From partners to collaborators

Our methodology reflected a democratic approach that sought to engage communities to steer and develop the agenda for local recovery, rather than to build ‘partnerships’ with the intention of enrolling communities in assisting professionals to realise external goals. To be sure, there are many benefits to partnership approaches whereby professionals partner with local communities, including combining knowledge, resources and operating styles and sharing risks to achieve more together than alone; enlarging budgets and operating means through coordinated efforts to increase access to additional financial and practical resources; and enhancing recovery innovations through becoming accustomed to one another’s working methods (Mayo, Citation1997; Sanderson, Citation2019a; Trevillion, Citation2020). A key limitation of this approach, however, is that it enables professionals to effectively ‘deliver’ support and sweep over the complexities inherent in establishing and maintaining working relationships (Fjäder, Citation2021; Warner & Sullivan, Citation2017). Additionally, partnerships run the risk of perpetuating hierarchical and concentrated governance paradigms, thereby rendering communities as passive participants (Awotona, Citation2016). A collaborative approach, on the other hand, does not simply mean professionals deliver support with the assistance of communities, but rather that recovery is a collaborative endeavour through it being a community-driven activity that enrolled professionals.

On collaboration and recovery, Ravetz (Citation2017) makes a distinction between knowledge about something (i.e. resilience frameworks) and knowledge via experience (i.e. resilience-building). The former is likened to top-down approaches through an indexical understanding of recovery (i.e. indicators of vulnerability and resilience) and the latter to bottom-up recovery through the intimate knowledge of being part of a community. Reflecting on this distinction, Participant 4 stated:

Building resilience isn’t a one-time thing. It is an ongoing thing, it’s a collective mindset. In my role, I spoke to a family from another town yesterday. They had their own disaster lived experience, which was different to what we had here. But they didn’t understand what we were trying to achieve through RTI. I ended up saying: it’s just about being informed and aware of possibilities or circumstances that may affect the community. Not that they need to be ready for anything, but that the community is aware that things can happen, often without notice. That part of being resilient is knowing that those things happen, and we may not have all the answers up front, but at least we can have good ideas, which are being built through the workshops. (P4, Recovery Worker, Government sector)

Action planning positioned locals-as-experts and adopted the preparedness planning materials produced by a local NFP to build local plans. In Town Two, sections of the plan included: staying informed, getting connected, being organised and packing belongings. Critical to this activity was identifying local capacities for contending with disasters, who would contribute, when, and how. In Town One, a phone-tree was identified as being important for understanding who was in the community, their specialised skills and knowledges, their capacities and resources, and any needs people might have during a future disaster. Understanding community responses to adversity, including their needs, capacities, and ambitions, requires an awareness of local history, politics, and cultural values – as these provide useful clues for building working relationships (Lindberg Falk, Citation2015). The question about boosting community safety proved useful for understanding the specifics of each town, their preferred engagement style, and which actors they were willing to become engaged with.

Polycentric governance is therefore about creating conditions for enabling disaster recovery to be less hampered by existing hegemonic systems (Holley & Shearing, Citation2017). This was the driving force behind RTI’s workshop events. For this reason, part of understanding the reality of disasters for community members is understanding the social and cultural context of disaster threats. Disasters occur within complex, inhabited worlds with unique historical and environmental contexts. Indeed, disasters often appear to be complex one-off events, but are actually made up of a multiplicity of people, events, histories, and processes that affect the ways they are responded to and recovered from (Tierney & Oliver-Smith, Citation2012, p. 124). Critical, then, to collaborations is engaging broad stakeholders, including community leaders, townspeople, recovery and support organisations, and excluded groups.

Culture brokers: creating polycentric linkages in disaster governance

Throughout early phases of RTI, the arrangements for identifying, mobilising, and integrating skills, resources and capacities highlighted the need for additional capacities. In Town Two, which had been hastily evacuated due to bushfire and where operational delays contributed to the disaster’s severity, it was hoped that local knowledges and capacities could be built-up where they did not presently exist to respond to future threats. The role of the ‘culture broker’ in polycentric disaster management is important, seen as a person in the community who can help to further enfranchise local residents by identifying added supports that do not presently exist in the community. This is a person capable of ‘bridg[ing] cultural divides and smooth[ing] communication between groups’ (Browne, Citation2015, p. 23). Indeed, they are what Burris et al. (Citation2005) have termed ‘super nodes’ within a network that connect disparate pathways, not dissimilar to Granovetter’s (Citation1973, Citation1983) work on ‘bridges’ in the social capital thesis. Reflecting on culture brokers post-Hurricane Katrina, Browne (Citation2015, p. 23) states:

Culture brokers use their ears and their voices. They listen and then communicate their insights, back and forth, back and forth, helping both parties to make sense … . Invisible cultural divides reside everywhere, quietly separating people by region, class, race, language, power, gender, ethnicity, education. But because cultural values and practices rarely get a hearing in disaster scholarship, the value that culture brokers could bring … has been left unexplored.

This value was highlighted by RTI’s multi-sector team members. The ability to position themselves between top-down (technocratic, state and market approaches) and bottom-up (local, community-oriented approaches) systems provided multi-sector collaborations with contextual information for understanding how local hazards and poor planning adversely affect local communities. Within the communities of Towns One and Two, these worlds were adjoined through the work of Participant 5, the RTI project manager, a retired community member who had lived in the region for decades and worked across the private and public sectors. For this participant, resilience is built through providing additional capacities, which residents lacked prior to bushfires, but which could enfranchise them to build strong communities and to implement the needs and aspirations raised during action planning:

I want to run training courses. I’m working at the moment to set up as many different types of training courses that we can run in these small towns. If we got to the stage where we could run a course, say, in [Town Two] and train another 10 people in First Aid, it strengthens not only employability, but the town. Suddenly another 10 people have got First Aid qualifications. (P5)

Courses were identified in both towns as being critical to their recovery, and complementary to the other community projects spawned of action planning events. The presence of external emergency responders during the bushfires demonstrated that, in rural areas, emergency services and first responders may not know an area well. Residents’ capacitation in pre-hospital care, which they can administer prior to emergency services arriving, is critical to ensuring the health and wellbeing of the community going forward. This brings connection to community, capacity, and community aspirations into relation. As Shaw (Citation2014, pp. 4–5) notes on community-led disaster risk reduction, residents are often first responders, with capacitation ‘addressing the root cause of their vulnerability [and] recognising their fundamental right to participate in decisions that impact on their lives’ (Shaw, Citation2014, pp. 4–5).

In Town One, in addition to pre-hospital care, capacity building was focussed on farm management during disaster (i.e. using generators, chainsaws, and ultra-high frequency radios). In Town Two, the focus extended to building economic capacity through upskilling for increased employment in the face of slow industrial decline and increased seasonal agricultural work (e.g. first aid, responsible service of alcohol and responsible gambling service training). Participant 5 organised training sessions democratically, allowing the demand for particular courses to guide what kind of training was offered.Footnote5 The ability to use skills to manage farming and community assets and to protect lives and livelihoods was an important aspect of building stronger communities outside of a disaster and to ensure towns can effectively mobilise and integrate a diverse range of resources and knowledges into response and recovery initiatives. The culture broker is particularly important for this work, as they provide multi-sector collaborators with contextual information for understanding the way local hazards and poor area planning adversely affect local communities when calamity strikes.

The importance of social capital

Capacity is important during disasters because supply-chains break down and additional divides can add up, preventing self-determination. New faces emerge, but locals could perform these roles if more overlap existed, as through training. The professions, from police, lawyers, teachers, accountants, the emergency services and doctors all undergo regular training. However, the very people who are affected by disasters are expected to adapt and respond quickly. Skills need not always be specific to disasters, but to the overall strength and protection of communities. Social capital is vital here because training occurs in the context of broader networks and allows people to come together to service and nurture bonds. As an embodied resource, social capital is an aspect of one’s identity and associational membership, critical to people-centred resilience and collaboration. Within the context of recovery,

social capital refers to the extent to which an individual involves [themselves] in different informal networks as well as formal civic organizations. This conceptualization of social capital includes many ways in which the members of a community interact, such as participating in recreational activities, talking to neighbours, and joining political parties and environmental organizations. In this sense, social capital reflects the overall pattern of a community’s associational life and civic health, the strength of ties between neighbours and friends, and degree of trust and norms of reciprocity among residents. (Sadri et al., Citation2018, p. 1380)

Discussions with community members about what it meant to live in the region focussed on a range of characteristics, including the close bonds between townspeople that are serviced through everyday working and social interactions as well as over the life course. As people grow-up, move to town, participate in community life, grow their own families and social networks, remain a contributing community member, or else leave intermittently or return after some time, strong and enduring bonds are developed that equate to feelings of belonging and connectedness. This dynamic has led to good intergenerational and intra-regional working arrangements between young and old (e.g. through organising whole of town events and festivals). While a strong local ‘culture’ exists that undergirds feelings of belonging and connectedness, a discernible lack of culture and competence around community disaster management persists. Perhaps most evidently, this was seen in Town Two through the evacuation protocol displayed on the main noticeboard in town being almost 15 years out-of-date.

Polycentric disaster governance arrangements stress that community-led recovery planning is based on collaborative, de-centred governance arrangements. This allows community to drive initiatives using varied governance arrangements (Ostrom and Cox Citation2010). Within the social capital thesis, bonding (strong primary ties) and bridging (strong secondary ties) capital are regarded as important. The former is about how communities turn to existing social resources to withstand calamity. The latter is about how people bridge the ties and resources required to ensure their safety and continued survival. These are based on the everyday accrual and maintenance of community ties and connectedness, with the literature demonstrating that the communities with stronger ties before a disaster faring better afterwards (Aldrich, Citation2019). Yet what is often left out is the third type of social capital – linking capital – which stresses the ability for a community to self-organise and self-determine by virtue of their social capital resources and ties (weaker ties that are capitalised on in times of need). Granovetter (Citation1973, p. 1361) argues that strong ties are built by a ‘combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterise the tie.’ However, weaker ties are vital to nurturing an individual’s and community’s social capital, as weak ties are ‘the channels through which ideas, influences, or information’ from distant sources take on resonance as they are encountered, which stresses the importance of being exposed to new ideas and networks (Granovetter, Citation1973, p. 1361). Weak ties, thereby, play an important role in effecting social cohesion and social change and developing capacity.

Coordinating nodal assemblages in polycentric disaster recovery

Emerging learnings presented here have been instructive on two counts. The first is for identifying and enfranchising local capacities to address the question ‘How can we make our communities safer?’ The second concerns what this means for how effective collaborations are built and maintained to support community-led recovery, particularly for mobilising and integrating diverse capacities and knowledges. In this final section, we discuss the role of coordination in polycentric governance. For enhancing feelings of community, trust, safety, and enfranchisement, training courses built an important quality into polycentric governance of disasters – namely, redundancy. Having additional ‘slack’ in the system means more people with a diverse range of skills overlap to complement one another. This would have been assistive in Town Two prior to the fires when additional emergency service personnel, who weren’t familiar with the area, its topography and demographic profile, were brought in to help. Redundancy therefore shows how capacitation is important and how it regularly works as a means of keeping people’s capacities up to date. What’s more, it builds agility into community response and recovery, which is something that was found to be missing in the Snowy Valleys, evidenced through suggestion by residents at workshop activities that it can be easier not to be prepared as it is not always apparent what to prepare for when anticipating disaster onset.

Responding to a cultural shift in scholarly debate, and the difficulties encountered in the coordination of diverse resources (Shaw, Citation2014; van Niekerk et al., Citation2018), the conditions, values, and practices behind polycentric governance have been explored through RTI’s methodology that are beneficial for creating effective cross-sector collaborations post-disaster. The cycle of disaster management elucidates what is involved in responding to the conditions of vulnerability posed by natural hazards to people and places. However, it is important to pay attention to the ‘culture cycle’ that allows for social reproduction in a community and how this may be devoid of a discrete ‘culture’ of disaster management. The culture cycle are the meaningful values and practices that give consistency to a community (social ties, trust, local knowledge and connection to place) and, in the context of recovery, reinvigorate community life and recovery efforts. The way a people use, interpret, and reproduce knowledges, resources, materials, and places of shared importance, including as part of disaster governance and community recovery, is therefore important to understand, particularly when towns do not have an established culture of disaster management, meaning response and community recovery following adversity do not have practical or localised precedents (Browne, Citation2015).

Strong community ties are an essential ingredient to support the resilience of a community, with community-centred governance arrangements outside of disaster being beneficial for collective response and recovery when adversity strikes (Shaw, Citation2014, p. 5). Indeed, research has shown that ‘communities having strong social ties are likely to better face adverse impacts together’ (Sadri et al., Citation2018, p. 1380) as strong leadership, trust, reciprocity, and social cohesion factor into preparedness, response and recovery initiatives, and their outcomes. Within the social capital thesis, bonding and bridging capital are held up as being important. These are based on the everyday accrual and maintenance of community ties and connectedness, with the literature showing that communities with stronger ties before a disaster fare better afterwards (Cruwys et al., Citation2024). What is often left out is the third type of social capital, linking capital, which enhances the ability for community to self-organise and self-determine by virtue of introducing new skills, capacities, and resources. Importantly, building effective cross-sector collaborations that support community-led recovery does not necessarily mean that such recovery needs to be community ‘heavy’. Indeed, given the current reliance in Australia and other advanced welfare societies on command-and-control authorities and their professional skills and abilities in the disaster management cycle, the shift from top-down models towards community dominant recovery models would appear to be a way off, if at all possible. The arrangements put forward by RTI to support communities to develop recovery strategies highlight the additive approach taken through initiatives that widen local recovery networks to include community and cross-sector recovery actors, including emergency services, through culture brokers.

It follows that effective cross-sector collaboration is one that places community needs and ambitions at the centre of recovery work, particularly through the important translation work effected by culture brokers. Amid the reshaping of the delivery of public services across within disaster management cycle, trial and error and serendipitous arrangements that promote, where possible, community needs and aspirations are critical to ensuring people are knowledgeable about and prepared for disasters. This flexible, community-centred approach can further help to build trust, leading to situations where professionals seek to ask residents what should be done to complement local work. Coordination is broadly based on communication (the sharing of knowledge among actors), alignment (the process of tailoring and adjusting), and collaboration (through prioritisation of shared ambitions) (Sanderson, Citation2019c, p. 59). In top-down conceptions of recovery, social resources are seen as protective factors against the full force of disasters, and important in building recovery partnerships. Methodologically, however, there are two approaches used to understand the strength and utility of local capacities within their larger socio-political contexts, this includes the well-known approach of inquiring into social capital and a growing turn towards understanding the cultural aspects of a community and the effect this can have on understanding the ways systems and vulnerabilities affect one another. Indeed, a view to boosting the recovery phase through community-centred governance necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the social elements that shape a system (Sadri et al., Citation2018, p. 1379). Such an approach is characteristic of a bottom-up model for community-centred recovery, whereby the identification, mobilisation, and integration of local capacities needed to respond to and recover from disasters collectively draws upon polycentric governance initiatives.

Recommendations

Having established the arrangements used by cross-sector collaborators in the Resilient Towns Initiative for polycentric disaster management, we put forward three normative recommendations:

Practitioners are encouraged to continuously improve on, and seek to understand in full socio-cultural and demographic specificity, the communities they work with

The principle of ‘following what works’ ought to be paired with the aspirations of a community when supporting disaster recovery

Appreciating that no one person or group of people possess the skills, knowledge, and capacities to drive recovery, rather recovery networks should be enlarged.

For policymakers, a further four considerations ought to be adopted:

See collaborations as networks rather than hierarchies.

1.1 This requires policymakers moving away from ‘partnerships’ with communities and towards initiatives that leverage the existing networks that make up a community, which are already tracked (e.g. Natural Hazard Research Australia, Citationn.d.), through seldom invested in.

Develop budgets and funding arrangements for polycentric, community-led recovery projects.

2.1 An example includes The Resilient Towns Initiative, explored here, funded through the State Government’s $600 million in relief and recovery projects for local economic and bushfire recovery.

Develop budgets and funding for local training and capacitation.

3.1 Survey community needs in regional and remote areas and expand existing skills and training budgets to include community needs, in this way building redundancy into the capacity building

Award collaborative networks and communities who excel in building local capacity and training.

4.1 An example includes the International City/County Management Association’s Local Government Excellence Awards (Community Sustainability). In the state of NSW, this includes the annual NSW Training Awards.

To build a cultural change in how top-down and bottom-up recovery approaches are understood and practiced in terms of cross-sector public service delivery, the multiplicity of recovery actors and their knowledges, skills, resources and capacities that have been raised here ought to be seen as an asset of disaster management, rather than being seen as cumbersome or a drain on processes and resources.

Conclusion

Opportunities for polycentric disaster management have been explored as part of an investigation into the conditions for building effective cross-sector collaborations in disaster recovery. Participatory action planning and ethnographic methods provided an in-depth case study in a region with little history of climate change related mass disasters, highlighting: the importance of embracing and linking diverse capacities and capitals, the need for collaboration over ‘partnerships’, and the importance of culture brokers in mediating and innovating local. Our approach has tracked the development of a polycentric approach given the disaster management literature identifies two issues that impede building effective collaborations, but which we argue can be overcome through a collaborative approach. The first is competition over what knowledges and resources are mobilised: top-down or bottom-up, and the second, how best to integrate these knowledges within disaster recovery initiatives. The importance of an area’s social capital was raised as critical to understanding recovery experiences and supporting the opportunities and the challenges that people face post-disaster. Culture brokers are important, as they operate between community and other sectors, and activate strong and weak ties to effectively build and support community-led recovery processes. They provide multi-sector collaborations with contextual information for understanding the way local hazards and poor area planning adversely affect local communities when calamity strikes. Key to this, we have argued, is building ‘redundancy’ into polycentric governance arrangements. Further research in this area could fruitfully bring together the community perspectives of polycentric disaster management and culture brokers, assess multiple and cascading disasters, and examine the conditions for building polycentric governance longitudinally at multiple time points.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful to the communities in the Snowy Valleys who took part in the Resilient Towns Initiative and who participated in this research. Map provided by CartoGIS Services, Scholarly Information Services, The Australian National University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Criticism included the Federal government’s general reticence concerning its response to the bushfires, a lack of policy ambition at the state and Federal levels and, in some fire-affected areas, poor coordination between different levels of government.

2 It is important to note that bushfire emergency response typically comprises both professional and volunteer services, with the latter drawn from the community and local district. During mass emergencies, such as the 2019–2020 fires, the deployment of external personnel into different parts of the country was very common.

3 Declining from a score of 3.9 out of 5.0 in 2018 to 3.3 in 2021 (Jetty, Citation2021, p. 19). The following factors contributed to low levels of trust and confidence: leadership, ambition, value for money on rate payments, critical infrastructure, community decision-making, and feeling informed about actions taken by authorities.

4 Town One scored 0.43 and Town Two scored 0.50 on Natural Hazard’s Research Australia’s (n.d.) ‘Disaster Resilience Index’; Coping capacity comprising of ‘social character’ (115 indicators), ‘economic capital’ (15 indicators), ‘emergency services’ (13 indicators), ‘planning and the built environment’ (10 indicators), ‘community capital’ (11 indicators), ‘informed access’ (3 indicators); Adaptive capacity comprising of ‘social and community engagement’ (6 indicators) and ‘governance and leadership’ (4 indicators).

5 400 residents from Towns One and Two and surrounds participated in five course offerings, aged 16–79.

References

- Aldrich, D. P. (2019). Black wave: How networks and governance shaped Japan’s 3/11 disasters. University of Chicago Press.

- Awotona, A. (2016). Planning for community-based disaster resilience worldwide: Learning from case studies in six continents. Taylor and Francis.

- Bahadur, A., & Tanner, T. (2014). Transformational resilience thinking: Putting people, power and politics at the heart of urban climate resilience. Environment and Urbanization, 26(1), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247814522154

- Berchtold, C., Vollmer, M., Sendrowski, P., Neisser, F., Müller, L., & Grigoleit, S. (2020). Barriers and facilitators in interorganizational disaster response: Identifying examples across Europe. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 11(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-020-00249-y

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Broch-Due, V., & Ystanes, M. (2016). Trusting and its tribulations: Interdisciplinary engagements with intimacy, sociality and trust. Berghahn Books.

- Browne, K. E. (2015). Standing in the need: Culture, comfort, and coming home after Katrina. University of Texas Press.

- Burris, S., Drahos, P., & Shearing, C. (2005). Nodal governance. Australian Journal of Legal Philosophy, 30, 30–58.

- Campbell, E., & Lassiter, L. E. (2015). Doing ethnography today: Theories, methods, exercises. Wiley.

- Cruwys, T., Macleod, E., Heffernan, T., Walker, I., Stanley, S. K., Kurz, T., Greenwood, L. M., Evans, O., & Calear, A. L. (2024). Social group connections support mental health following wildfire. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 59, 957–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02519-8.

- DPS. (2020). 2019–20 Australian bushfires—Frequently asked questions: A quick guide. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/7234762/upload_binary/7234762.pdf

- Eadie, P., & Su, Y. (2018). Post-disaster social capital: Trust, equity, Bayanihan and Typhoon Yolanda. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 27(3), 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-02-2018-0060

- Ebers, M. (2015). Interorganizational relationships and networks. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (2nd ed., pp. 621–625). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5.

- Fernandez, G., & Ahmed, I. (2019). “Build back better” approach to disaster recovery: Research trends since 2006. Progress in Disaster Science, 1, 100003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100003

- Fjäder, C. (2021). Developing partnerships for building resilience. In S. Eslamian & F. Eslamian (Eds.), Handbook of disaster risk reduction for resilience: New frameworks for building resilience to disasters (pp. 261–278). Springer.

- Fraser, T., Aldrich, D. P., & Small, A. (2021). Seawalls or social recovery? The role of policy networks and design in disaster recovery. Global Environmental Change, 70, 102342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102342

- Gaillard, J. C. (2015). People’s response to disasters in the Philippines: Vulnerability, capacities, and resilience. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469

- Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233. https://doi.org/10.2307/202051

- Hamdi, N. (2010). The placemaker’s guide to building community. Earthscan.

- Hamdi, N. (2013). Small change: About the art of practice and the limits of planning in cities. Earthscan.

- Hamdi, N., & Goethert, R. (1997). Action planning for cities: A guide to community practice: Guide for community practice. Wiley.

- Hermansson, H. M. L. (2016). Disaster management collaboration in Turkey: Assessing progress and challenges of hybrid network governance. Public Administration, 94(2), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12203

- Holley, C., & Shearing, C. (2017). Nodal governance. In B. S. Turner (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell encyclopedia of social theory (pp. 1–2). Wiley.

- Jana, N. C., & Singh, R. (2022). Introduction. In N. C. Jana & R. Singh (Eds.), Climate, environment and disaster in developing countries (pp. vii–xviii). Springer.

- Jetty. (2021). Community Satisfaction Survey 2021, Snowy Valleys Council. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/v/1/reports-amp-strategies/svc-community-satisfaction-survey-2021-research-results-jetty-research.pdf

- Koivisto, J. E., & Nohrstedt, D. (2017). A policymaking perspective on disaster risk reduction in Mozambique. Environmental Hazards, 16(3), 210–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2016.1218820

- Lenette, C. (2022). Participatory action research: Ethics and decolonization. Oxford University Press.

- Levin, S. A., Anderies, J. M., Adger, N., Barrett, S., Bennett, E. M., Cardenas, J. C., Carpenter, S. R., Crépin, A. S., Ehrlich, P., Fischer, J., Folke, C., Kautsky, N., Kling, C., Nyborg, K., Polasky, S., Scheffer, M., Segerson, K., Shogren, J., van den Bergh, J., Wilen, J. (2022). Governance in the face of extreme events: Lessons from evolutionary processes for structuring interventions, and the need to go beyond. Ecosystems, 25(3), 697–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-021-00680-2

- Lindberg Falk, M. (2015). Post-Tsunami recovery in Thailand: Socio-cultural responses. Routledge.

- Lockie, S. (2020). Sociological responses to the bushfire and climate crises. Environmental Sociology, 6(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2020.1726640

- Mayo, M. (1997). Partnerships for regeneration and community development: Some opportunities, challenges and constraints. Critical Social Policy, 17(52), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101839701705201

- Meyer, M. A. (2018). Social capital in disaster research. In H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, & J. E. Trainor (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research (pp. 263–286). Spinger Link. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_14

- Natural Hazard Research Australia. (n.d.). Disaster resilience maps. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://adri.bnhcrc.com.au/#!/maps

- Osborne, D., & Graeber, T. (1992). Reinventing government. Penguin Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2014). A polycentric approach for coping with climate change. Annals of Economics and Finance, 15(1), 97–134.

- Ostrom, E., & Cox, M. (2010). Moving beyond panaceas: A multi-tiered diagnostic approach for social-ecological analysis. Environmental Conservation, 37(4), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000834

- Ostrom, E., & Walker, J. (Eds.). (2003). Trust and reciprocity: Interdisciplinary lessons from experimental research. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Pyne, S. J. (2021). The Pyrocene: How we created an age of fire, and what happens next. University of California Press.

- Ravetz, A. (2017). On reverie, collaboration, and recovery. Collaborative Anthropologies, 10(1–2), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1353/cla.2017.0002

- Sadri, A. M., Ukkusuri, S. v., Lee, S., Clawson, R., Aldrich, D., Nelson, M. S., Seipel, J., & Kelly, D. (2018). The role of social capital, personal networks, and emergency responders in post-disaster recovery and resilience: A study of rural communities in Indiana. Natural Hazards, 90(3), 1377–1406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-3103-0

- Sanderson, D. (2017). Collaboration and cross-sector coordination for humanitarian assistance in a disaster recovery setting. In Susan L. Cutter (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of natural hazard science. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.178

- Sanderson, D. (2019a). Coordination in urban humanitarian response. Progress in Disaster Science, 1, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100004

- Sanderson, D. (2019b). The importance of prioritizing people and place in urban post-disaster recovery. In K. Bishop & N. Marshall (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of people and place in the 21st-century city (pp. 252–262). Routledge.

- Sanderson, D. (2019c). Urban humanitarian response (12; good practice review). Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute.

- Sanderson, D. (2020). Identifying resilience in recovery – complexity, collaboration and communication. In D. Sanderson & L. Bruce (Eds.), Urbanisation at risk in the pacific and Asia: Disasters, climate change and resilience in the built environment (pp. 206–219). Routledge.

- Sanderson, D., & Delica Willison, Z. (2014). Philippines Typhoon Haiyan: Response review. Retrieved July 29, 2022, from https://www.alnap.org/system/files/content/resource/files/main/dec-hc-haiyan-review-report-2014.pdf

- Schruijer, S. (2020). The dynamics of interorganizational collaborative relationships: Introduction. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030053

- Services Australia. (2020). Annual report 2019–20. ALNAP. Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/annual-report-2019-20v2.pdf

- Shaw, R. (2014). Disaster risk reduction and community approaches. In R. Shaw (Ed.), Community practices for disaster risk reduction in Japan (pp. 3–20). Springer.

- Syamsidik, Oktari, R. S., Nugroho, A., Fahmi, M., Suppasri, A., Munadi, K., & Amra, R. (2021). Fifteen years of the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami in aceh-Indonesia: Mitigation, preparedness and challenges for a long-term disaster recovery process. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 54, 102052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102052

- Tierney, K., & Oliver-Smith, A. (2012). Social dimensions of disaster recovery. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 30(2), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072701203000210

- Trevillion, S. (2020). Networking and community partnership (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Tselios, V., & Tompkins, E. (2017). Local government, political decentralisation and resilience to natural hazard-associated disasters. Environmental Hazards, 16(3), 228–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2016.1277967

- US National Research Council. (2011). Building community disaster resilience through private–public collaboration. National Academies Press.

- Vallance, S. (2015). Disaster recovery as participation: Lessons from the Shaky Isles. Natural Hazards, 75(2), 1287–1301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1361-7

- van Niekerk, D., Nemakonde, L. D., Kruger, L., & Forbes-Genade, K. (2018). Community-based disaster risk management. In H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, & J. E. Trainor (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research (2nd ed., pp. 411–429). Springer.

- Warner, M., & Sullivan, R. (2017). Putting partnerships to work: Strategic alliances for development between government, the private sector and civil society. Routledge.

- Wates, N. (2014). The community planning handbook: How people can shape their cities, towns and villages in any part of the world (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2014). At risk: Natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters (2nd ed.). Routledge.