ABSTRACT

Detailed planning for housing development is the responsibility of the respective municipalities in Sweden. Further, an ambition to develop sustainable building solutions based on wood is combined with each municipality’s building requirements, which increases complexity in the public process. Public actions leading to increased construction of wooden multi-family houses are important for all actors in this process, which is managed by municipalities through the Public Procurement Act or the land allocation process, depending on their development plan and strategy.

The aim is to shed light on how the land allocation process is currently performed, to improve efficiency and provide transparency and structure between developers and municipalities. The study uses the public procurement process as a conceptual model to structure the various activities in the land allocation process based on the similarities between the two processes. Thereafter, it is applied to the tender-based land allocation process to provide a transparent process for municipalities to follow.

The results display discrepancies in perception of the land allocation process and the level of competence displayed by municipalities when managing this process. This hinders the development of wooden multi-family houses in Sweden.

Introduction

An investigation conducted by Boverket [National Board of Housing, Building and Planning] estimated that approximately 240 of 290 Swedish municipalities show a shortage of housing units, with a forecasted demand of approximately 600 000 housing units between 2015 and 2025 (Boverket Citation2015; Boverket Citation2018). This building goal can possibly be realised by optimising the potential of using different building materials for multi-family houses, a market currently dominated by concrete and steel solutions, and where wooden multi-family houses have a minor market share of approximately 13% (Andersson and Larsson Citation2014; TMF Citation2018). The limited use of wood in construction could be seen as contradicting the EU 2020 strategy that highlights increased use of wood as an instrument to obtain green, sustainable building solutions (EU Citation2011. COM 2020; EU Citation2012. COM 433).

Lindgren and Emmitt (Citation2017) found that a shift towards buildings that use wood-frames is not based on design and technological features alone, but rather on political decisions and public actions, such as development strategies, legislation and taxation (Björheden Citation2006; Tudor et al. Citation2007). Further, the National Agency for Public Procurement states that public procurement activities within municipalities are enabled to enforce specific requirements in each procurement situation, but not from whom they procure products or services (Upphandlingsmyndigheten [National Agency for Public Procurement] Citation2017). This definition provides an important distinction for municipalities’ actions related to building plans, including developing and implementing sustainability solutions based on the government’s sustainability strategies (Gustafsson and Whilborg Citation2016). Municipalities can circumvent these limitations in their general planning process by requiring specific solutions, using the land allocation process, i.e. requiring wood in the detailed development plans, thus increasing drivers for developing wood-based building solutions (Lundqvist and von Borgstede Citation2008; Hrelja et al. Citation2015).

Municipalities have to consider different legislations when implementing development strategies for wood in new building projects. Of these, the Planning and Building Act (SFS Citation2010:Citation900), the Swedish Environmental Code (SFS Citation1998:Citation808), the Public Procurement Act (SFS Citation2016:Citation1145), and Boverkets Building Regulations (BFS Citation2011:Citation6) are perceived as the primary legislation. Additional requirements for new building developments are included in the Swedish Local Government Act (SFS Citation1991:Citation900) and the Act of Contracts (SFS Citation1915:Citation218). However, the Act on Guidelines for Municipality Land Allocations (SFS Citation2014:Citation899) provides municipalities with increased flexibility in their building development activities. Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting (SKL) [Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions] has reviewed how the land allocation process is used in combination with SFS Citation2010:Citation900 and other legislation (SKL Citation2014). In this respect, municipalities claim civil law permits them to pose specific requirements in this process, e.g. requiring wood-based building solutions (Lundqvist and von Borgstede Citation2008). In this context, municipalities own land suitable for housing projects (Boverket Citation2013), which can be sold to developers by imposing specific requirements to finalise the sale (SFS Citation2014:Citation899; Caesar Citation2016), a process similar to the method used in procurement activities, (Weele Citation2010; Sanderson et al. Citation2015). Further, Caesar (Citation2016) found that the land allocation activity could in its current form result in barriers for small or financially weak developers, excluding them as a result of an insufficient structure in the land allocation process combined with subjective decision-making by municipalities (Caesar Citation2016). This could be avoided by adopting a process similar to a procurement model, which provides structure and transparency for all involved parties (Weele Citation2010; Sanderson et al. Citation2015).

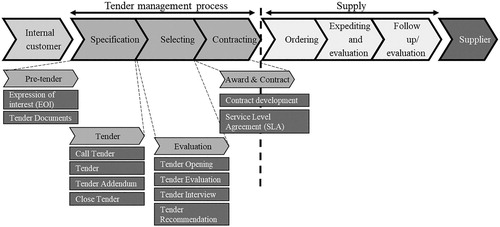

Figure 1. Procurement process (Weele Citation2010).

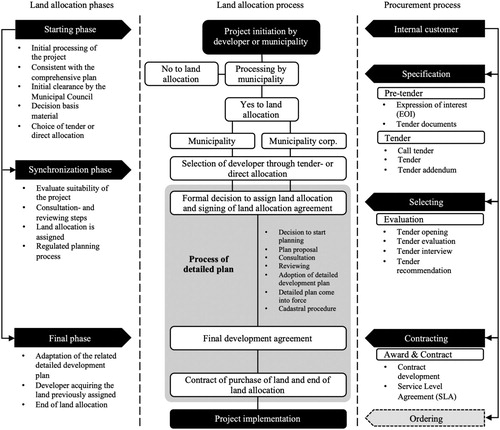

Although land allocation processes play a dominant role in housing supply, Caesar (Citation2016) concluded that research about land allocation hardly exists. However, Caesar’s (Citation2016) research related to land allocation is established on a model by Kalbro (Citation2000), which identifies a method to classify the building development process by Swedish municipalities based on developers’ involvement in municipalities’ plan preparation. Caesar (Citation2016) developed a model to synchronise the steps between the land allocation- and planning processes to provide an understanding of the involved activities up to project implementation. The model was divided into three phases: starting phase, synchronisation phase and final phase, incorporating both internal and external activities, e.g. decision of project scope, selection of developer, development agreement, and final contract to procure the land by the developer. It is performed by municipalities using a certain degree of structure, including project evaluation, which is described in the land allocation phase (Caesar Citation2016) of , and linking this to the land allocation process in the centre of . This is, from the developers’ point of view, the initial step in a process similar to the activities in a procurement situation, a process Weele (Citation2010) described as providing a structure for evaluating activities, ensuring transparency and monitoring project fulfilment (). The procurement process (Weele Citation2010) is combined in to display similarities with activities in the land allocation process and the defined land allocation phases (Caesar Citation2016). The procurement process displays required activities to develop and finalise a proficient process, including internal decisions, documentation and evaluation requirements, providing a different method to control how these activities are performed and provide transparency and efficiency in the land allocation process.

Figure 2. Comparison of the land allocation process (Caesar Citation2016) and the procurement process (Weele Citation2010).

The model Caesar (Citation2016) presented shares similar activities until the contracting stage of the model by Weele (Citation2010) (), where the relationship between the two models is primarily from a structural, rather than a conceptual point of view. These main differences are based on one model having a sales focus (Caesar Citation2016) whereas the other has a procurement focus (Weele Citation2010), which requires for different methods to be used fulfilling the main deliverables of the presented models. The procurement model provides a more stringent process, offering greater control and structure compared to land allocation phases that do not necessarily impose the same requirements and structure due to the legislation (SFS Citation2014:Citation899). Furthermore, the method used in the procurement model is based on a greater degree of accountability due to the nature of the process, which requires an organisation to monitor the degree of contract fulfilment compared to the agreed levels in the procurement process. This is not similar in the land allocation process that has limited accountability, and structure the land allocation phases () without developing a stringent method, which directly influences the project outcome based on the general scope and the finished products (Caesar Citation2016). Hence, a more stringent method, similar to that of a procurement model to control project deliverables could be beneficial, (Koskele Citation2003), and would provide further control beyond the scope displayed in the land allocation phases, . Further, the increased control provided by a defined structure offers a greater likelihood of delivering the project and focus in fulfilling specific areas, such as cost control, building quality and environmental impact. These benefits are not only contributed to the structure of the model but are equally dependent on external factors posed by, e.g. industry or by legislative conditions that can influence the strategic outcome of organisational activities related to the tender based land allocation, or procurement process (Weele Citation2010).

Using the model for procurement in a tender-based land allocation context is centred on similarities between the two processes, exemplified in , combined with the limited structural requirements defined in the land allocation activity (Caesar Citation2016). Hence, this study is intended to provide an increased understanding of the tender based land allocation process from which improvements can be made, not to change the activity described in SFS Citation2014:Citation899 into a procurement activity, i.e. use the process steps defined by Caesar (Citation2016) and identify how these steps could be performed based on the procurement model in . The aim is to investigate how the tender based land allocation process is currently performed by Swedish municipalities by using the procurement process as a structural model. Thereby, improving project efficiency, providing transparency and structure to generate possibilities for developers to successfully respond in the tender-based land allocation process.

Delimitations

This study applies the procurement process as a model to review performance of the tender-based land allocation activity, which is based on direct similarities and intentions displayed by municipalities performing this activity.

Conceptual framework

Local and regional governance is becoming more important in the planning of housing developments, including consideration of formal legislation and housing market requirements that can restrict the balance between housing supply and demand (Kang and Groetelaers Citation2018). Also, different approaches to governance use different relational concepts between actors, which need to be redefined in the strategic governance setting, e.g. specific interests, tasks and concerns (Poulsen Citation2009).

Strategic governance and planning are seen as a control model to handle the cooperation and coordination of actions between actors based on their ability to manage a specific project, i.e. getting public and private actors to work together for a mutual interest (Fredriksson Citation2015). The strategic planning process in public governance is seen as formalising direction and guidelines. It is a continuous process and an activity that identifies both public and private stakeholders that make governance possible (Healey Citation2009; Albrechts Citation2010; Fredriksson Citation2015; Hillier Citation2011). Furthermore, the organisation’s capability and structure affect the long-term success of public projects (Lamptey and Elle Citation2000). The increased influence of procurement in public organisations requires a general understanding of the methodology to manage the procurement function (Addo-Duah et al. Citation2014). Hence, irrespective of implementing or complying with public procurement legislation, effective procurement activities largely depend on a well-trained and skilled workforce, combined with a professional and structured process (McCue and Gianakis Citation2001; Prier et al. Citation2010; Appiah Citation2011; McKevitt et al. Citation2012; Addo-Duah et al. Citation2014).

The procurement function in public organisations has developed beyond its original scope and today incorporates more than an internal focus (Tassabehji and Moorhouse Citation2008). It requires skills related to, e.g. economic growth, environmental sustainability and market focus (Van Valkenburg and Nagelkerke Citation2006; McCrudden Citation2007; Arrowsmith Citation2010; Atkinson and Sapat Citation2012). Careful design and evaluation of the relevant aspects of procurement are crucial for its success. This is why in recent years the public sector developed a gradual shift towards a structured method to assess the procurement process (Dimitri Citation2013), similar to the structural requirements discussed by Corey (Citation1978) and Sanderson et al. (Citation2015), dividing the procurement process into four phases, similar to the procurement process in (Weele Citation2010). Only the first two phases apply to the structure discussed in the tender management process, i.e. pre-contract/selecting and contract ().

Table 1. Phases and steps in the procurement process (Corey Citation1978; Sanderson et al. Citation2015).

Also, similar process phases were identified in the studies by Novack and Simco (Citation1991) and Lawal (Citation2012), yet, these models have a slight variation on how the different process steps look and the detail to which they describe the process. However, these models all have a similar aggregated perspective of what the process steps look like and what is required to be included in these steps, described by Weele (Citation2010) in and the combined model in .

The tender management process () is a process of competitive bidding that is based on a project scope defined by the client and where the contractor is normally required to present a detailed design solution combined with a project timeline (Song et al. Citation2009). The tender management process includes activities up until the point of contract, which is followed by contract execution and monitoring that includes various milestones for the contractor, e.g. ordering, delivery and project evaluation (Corey Citation1978; Novack and Simco Citation1991; Weele Citation2010; Lawal Citation2012; Sanderson et al. Citation2015). This is particularly important for tender-based land allocation projects or a traditional procurement situation based on the Public Procurement Act (SFS Citation2016:Citation1145) where contractors’ evaluation requirements are stipulated. Hence, good decision-making influences the outcome of the general project, which is based on the availability of accurate information to support decisions (Ncube and Dean Citation2002), and contractor selection is one of the client’s main decisions (Eddie and Heng Citation2004). This structure also represents the frame of reference for developing a detailed tender management schedule used in the tender management process, starting with the expected completion date and incorporating material provided by the client and handover date for the final project (Caron et al. Citation1998).

However, it is important to note that the tender management process is structured into a client side and a contractor side, with different focus and requirements to consider (Weele Citation2010). The initial stages of the tender management process are based on internal activities to accumulate information that improves the quality of project requirements and evaluation sent to contractors. The tender management process is developed based on the client’s perceived requirements and is defined in the specifications/pre-contract phase (Corey Citation1978; Weele Citation2010; Sanderson et al. Citation2015) or starting phase (Caesar Citation2016). Since the decision-making process for submitted projects is complex, it is imperative for the client to present project requirements in a way that makes it possible to create a comparative evaluation that combines the results of all the contractors’ submitted proposals (Ncube and Dean Citation2002). Also, procurement in construction projects is a multi-dimensional process that requires a great degree of involvement and control by all involved parties (Ruparathna and Hewage Citation2015).

The structure for fulfilling the defined requirements of the tender management process is achieved through good practice, encouraging the client to implement judicious contractor selection techniques (Latham Citation1994). For that purpose, Fong and Choi (Citation2000) identified eight evaluation criteria for the tender management process: tender price, financial capability, past performance, experience, resources, current workload, past relationship, and safety performance. Developing suitable methods to evaluate proposals becomes increasingly important to manage the project’s risk (Jaselskis and Russell Citation1992). According to Wong et al. (Citation2000), evaluation methods for construction projects changed from focussing on low-cost principles to multi-criteria selections based on value rather than cost. Also, the client will strive towards identifying suitable contractors that contribute to a better construction solution and minimising the potential for risk derived from the evaluation phase of the tender management process (Cheaitou et al. Citation2018).

Research process

The research process was initiated by participating in two tender-based land allocation projects conducted from October 2016 through March 2017, which provided an opportunity to identify the scope using land allocation for new public building developments. The appointed steering committee collected and communicated documentation containing specific requirements during different process steps, i.e. Request for Information (RFI) and Request for Quotation (RFQ), which was followed by joint evaluation by the steering committee to select the winning bid. Hence, the tender-based land allocation process followed a similar process as displayed in and the tender management part of the procurement process ().

Research design

The primary objective was to investigate how the land allocation process is conducted, increasing transparency and efficiency between developers and municipalities, which would enable increased use of wood building solutions. The research process is perceived as primarily exploratory with descriptive components (Ellram Citation1996; Yin Citation2014). Further, using different levels of interviews is a good choice for collecting empirical data (Yin Citation2014) and provided a study suitable for both a qualitative and quantitative research approach and a mixed methodology, offering greater depth and range than a single method could deliver (Wallerstein et al. Citation2011; Mertens Citation2012). Thus, the choice of conducting a study combining qualitative and quantitative deliverables was motivated by the land allocation process of Swedish municipalities not being reviewed earlier in a tender management context, which improves understanding of the land allocation process. This research approach provides a structured view of the complexity faced by the respondents in a cross-sectional study which identifies the most important factors influencing the land allocation process (Yoshikawa et al. Citation2013). This provided an opportunity to capture the scope within the land allocation activity and identify transferable understandings by the respondents using interviews (Lucero et al. Citation2016). The interview template was based on 32 questions, where 22 questions had an additional quantitative option for increased analysis possibilities.

Data collection

Data collection began by identifying the framework for the study and key stakeholders involved in the building process associated with the land allocation process, focussing on wooden multi-family houses in Sweden. The objective was to collect information regarding tender management activities within the land allocation process, which is based on the perception of the main stakeholders, i.e. municipalities and developers (McKendall and Wagner Citation1997). The municipalities in this study represent different population sizes. Twenty percent (3 municipalities, 3 respondents) were smaller than 30 000, 55% (9 municipalities, 12 respondents) were between 30 000–100 000, and 25% (4 municipalities, 5 respondents) represented large urban areas, i.e. Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmo. Equally, the selected developers represented a mix. Approximately 40% (8 companies, 8 respondents) of the companies had a yearly turnover of less than 100 MSEK, 40% (8 companies, 8 respondents) had a yearly turnover of 100–500 MSEK, and 20% (4 companies, 4 respondents) had a yearly turnover larger than 500 MSEK, providing a good cross-section of challenges faced by the developers, irrespective of company size.

Participating in the initial stages of the land allocation activity gave necessary information regarding the general structure and process requirements, which enabled the design of a pre-interview template. Initially, six pre-interviews were performed with key decision makers within the municipality (1 planning manager and 2 project managers) and the developers’ organisations (1 project manager, 1 CEO and 1 sales director). The pre-interviews served to validate the structure and questions for the main interview guide. After that, 40 interviews were conducted during April and May 2017 with 20 developers from 20 companies within the wood building industry (6 CEOs, 5 business development managers, 5 sales directors and 4 project managers) and 20 employees from 16 municipalities (11 land and exploration managers and 9 planning/project managers). The selection of respondents aimed to incorporate different perspectives on the land allocation process regarding wooden multi-family building projects. The interviews took an average of 60 min over the phone or in person, and the interview template was designed around the land allocation process, the municipality’s building policy, the strategic role of land allocation, requirements of the land allocation process, and the managing organisation. The questions were verified as significant during the pre-interview sessions and were associated with activities until contract agreement, i.e. internal customer specification and selecting ().

Data analysis

The interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed using systematic text condensation (STC), which includes a review of the transcripts that are condensed into shorter value statements (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009). STC provides a loosely held subjective process that offers feasibility combined with an appropriate level of methodological structure that uses descriptive and explorative methods to analyse qualitative data derived from interviews (Malterud Citation2012). The statements were categorised based on the assessment made by the researcher to identify and sort meaning units, which provides a structure of condensation, and finally synthesising the meaningful units (Malterud Citation2012). The quantitative questions used a five-point Likert scale, in which 1 indicates no importance or no focus and 5 indicates high importance or high focus (Likert Citation1932) provided by respondents during the interviews. Questions that could not be answered by the five-point scale used percentages to indicate how the industry perceives these questions. Statistical results were created and are presented in and , displaying the mean, max, min and standard deviation (SD) for each question. This provides an opportunity to classify respondents’ perceptions and increase understanding of how they answered in relation to the total group (Boone and Boone Citation2012). The answers have been separated into three intervals linked to the perceived level of importance for the respondents, with 1.00 – 2.33 = low importance/ability, 2.34 – 3.66 = average importance/ability, and 3.67 – 5.00 = high importance/ability.

Table 2. Statistical review of the developers’ responses to questions 1–11.

Table 3. Statistical review of municipalities’ responses to questions 1–11.

Credibility

This study adopted a dynamic research process to enhance credibility, where interviews were recorded, transcribed and summarised for comments by the research group or with key respondents within the industry (Halldórsson and Aastrup Citation2003). Also, the respondents became an integrated part of the research process by providing opportunities to adjust the conclusion based on an increased understanding of the research topic as the process evolved, which contributed to credibility and reflected how well the researcher captured the respondents’ perception (Halldórsson and Aastrup Citation2003; Bailey Citation2007). Validity was addressed through pre-interviews with respondents with different backgrounds and roles in the land allocation process to validate the research scope and question guide. Further, adopting a systematic analysis procedure and continuous discussions between the involved researchers improved the accuracy derived from the study (Whitten et al. Citation2004).

Results and analysis

The first section of the results and analysis presents information regarding the municipalities’ and developers’ strategies regarding use of wood as a building material, and general information about their roles in the land allocation processes. The second section focuses on how activities within the tender-based land allocation process are performed by applying the structure of a procurement model, which is based on similarities between the processes (), i.e. activities during the internal customer, specification, selecting and contracting phases ( and ). The information provides an understanding of how the municipalities and developers perceive the situation regarding developments of wood building solutions using the land allocation process (SFS Citation2014:Citation899).

Section 1

General information

Close to half of the municipalities have an ambition to increase the number of buildings using a wood-based solution. However, only 33% of these municipalities have an official strategy regarding the development of wood buildings, a situation discussed by Appiah (Citation2011) and Addo-Duah et al. (Citation2014) as contributing to project sub-optimisation due to unclear strategic direction. Furthermore, 73% of the municipalities have no goals to increase the number of wood buildings, and as a municipality respondent remarked, “Not having any clear direction or strategy towards wood buildings is the main factor for not increasing this within the municipality today”. Also, a developer mentioned, “If the municipalities clearly state their intentions towards wood buildings, they are seen as a significant catalyst towards sustainability and wood building development”. However, most of the municipalities use official environmental policies rather than developing something specific that targets wood buildings. This is also evident considering their perception that political decisions and plans are seen as drivers for wood-based building solutions, which are not in focus for most municipalities. However, the study by Appiah (Citation2011) finds that a professional and transparent public process should be employed, irrespective of legislative conditions, to enable sufficient development in public projects. This is also mentioned in the studies by Arrowsmith (Citation2010) and McCrudden (Citation2007) discussing the impact of public processes as enablers of change based on defined strategies and planning methods, which, e.g. provide opportunities for developing environmental and sustainable building solutions.

An important distinction regarding the tender-based land allocation process is that despite developers procuring land from the municipalities, the perception of 76% of the developers is that they had the role as a seller of a building solution to the municipalities and rated it as having a high impact on the process (, question 9). This was expressed by a developer as, “It feels more like a sales process for possibly being given an opportunity to acquire land for development, which is based on how the activity is structured by the municipalities”. Another developer expressed it as, “Considering the tender-based land allocation process a strange activity with unclear roles between the parties, where you have to perform a detailed sales activity to reach an opportunity to procure land”, which is contradicted by municipalities included in this study that consider themselves sellers of land based on certain buyer requirements imposed on developers.

However, this process could imply a switch of roles, since the developers also see themselves as sellers during this process. This is a situation that can contribute to misunderstanding how the tender-based land allocation process is intended to work, according to the model discussed by Caesar (Citation2016). This process displays activities similar to a procurement situation, which would limit municipalities’ possibility to pose specific requirements to use wood building solutions (SFS Citation2016:Citation1145). Despite this situation, municipalities are not conducting an effective process, according to the model discussed by Addo-Duah et al. (Citation2014), since the necessary understanding of the methodology for managing structured work in a situation similar to a procurement model is lacking. A developer expressed this as, “The municipalities have very limited knowledge and understanding of managing this process, which is contributing to uncertainty and an ambiguous process”.

Also, the developers have a general view that their possibility to influence rules and regulations is limited, yet they feel this possibility would be important for developing wood buildings in Sweden. This is also reflected by one of their perceived drivers for market development being governmental and political factors, also defined by Ruparathna and Hewage (Citation2015) as important factors enabling procurement of construction projects. A developer expressed this, saying, “Increased transparency regarding the governmental actions, and drivers would benefit the development of sustainable construction using wood buildings, yet they are not taking necessary initiatives or understanding the market requirements to support this development”.

Section 2

Starting (internal customer) phase

The municipality’s executive board normally makes decisions regarding building development that are executed by the operational divisions within the municipality. This process is applicable to discussions by Koskele (Citation2003) and Weele (Citation2010) in , as an internal customer in a procurement context or as the starting phase discussed by Caesar (Citation2016) in land allocation. According to several municipality respondents, planning decisions are normally based on the programme for housing development or the general building plan developed by the municipalities and government. In some cases, official national statistics are utilised in combination with political decisions, reflected in , question 1. However, a municipality respondent considers this process to be affected by, “The politicians pushing hard in the decision-making process about what kind of developments that shall be implemented, which after that is interpreted by the civil servants based on plans, budget and coordination effect with the municipality”. Only in rare situations is the actual requirement from the population captured, i.e. suitable cost levels, quality, size, or material choice, which can limit the development of strategies as discussed by Atkinson and Sapat (Citation2012).

The land allocation process is perceived as an important tool for the municipality to develop its building development programmes. Hence, 58% of the building development programmes use this process, and , question 2 confirms the importance placed on this activity. Despite these general tools, most development is often based on guesswork, which by a municipality respondent explained as, “Being based on qualified guesswork with an intention to use official key figures related to population changes within the municipality”. This contradicts the communicated importance of the planning process and having accurate information available, discussed by McKevitt et al. (Citation2012), Prier et al. (Citation2010) and Caesar (Citation2016). The identified public drivers reflect this, where development is based on political and governmental decisions rather than market drivers. However, the land allocation process has displayed issues regarding a process lacking in transparency and prone to subjective judgements from the municipalities, also mentioned by Caesar (Citation2016). According to the study by Caron et al. (Citation1998), this is an activity that would benefit from the end-user’s requirements being considered during the initial stage of the process, rather than only focussing on requirements specified in the initial stage provided by, e.g. the municipality’s executive board or planning department. The importance municipalities place on this is captured in question 4. It clearly communicates the limited importance of the end-user’s requirements, and as a municipality respondent commented, “We have the opportunity to improve the process by understanding what we have done in the past and understanding what the market requires, yet we have limited capabilities to capture and utilise this kind of information today”.

Specification phase

The developers do not consider that municipalities have the knowledge to manage the process; municipalities provide insufficient information, which results in unclear requirements, as reflected by scoring the municipalities’ ability to manage this as low (, questions 2 and 3). This is discussed by a developer as, “The municipalities don’t have the necessary knowledge that you would expect from a counterpart in this type of process”. As another developer put it, “The process varies from different municipalities, and I feel they would greatly benefit if they internally clarified what is expected from this process and how they can achieve their intended targets”.

Additionally, the importance of professionalism to a successful process was discussed in the studies by McCue and Gianakis (Citation2001), McKevitt et al. (Citation2012) and Prier et al. (Citation2010). A developer mentioned that they “Consider the municipalities’ actions to generate unclear responses from the developers as a method to influence the decisions arbitrarily”. This is partially reinforced by the municipalities confirming that they only utilise a formalised process to a limited degree and instead favour an ad hoc structure. Hence, the municipalities do not consider it important to follow a pre-defined process (, question 3). This contradicts the discussion by Ncube and Dean (Citation2002) highlighting the importance of available information to provide a clear understanding of the requirements. The developers highlight the municipalities’ lack of structure as a problem and consider the municipalities to be subjective in their decisions and that their ad hoc structure contributes to communication issues regarding evaluation methods. This is reinforced by a developer stating, “It is difficult to get a clear understanding regarding their requirements, since these are subjective and very poorly communicated, which implies that the decisions are made randomly and are difficult to follow up”. Another developer perceives the process as having “Absolutely no clarity in how you will be evaluated, which may not matter because they do not seem to follow this anyway”. The issue described by the developers is discussed in similar terms by Arrowsmith (Citation2010), highlighting the importance of a defined structured for an efficiently managed process.

The unstructured approach to communicating project specifications is reflected by the limited focus in following up on previous projects, which several municipalities mentioned and is reflected in , question 4. The process is based on ad hoc initiatives, and results are not shared internally, resulting in possible sub-optimisation, which could be based on an untrained workforce and an unprofessional structure design, according to Appiah (Citation2011) and Addo-Duah et al. (Citation2014). This provides increased subjectivity when evaluating a developer’s solutions, which are directly based on limited information in the specification phase. A municipality respondent explained, “We would greatly benefit from a more stringent and standardised process to make sure our project objectives are being fulfilled and provide the developers with improved possibilities to successfully respond to our process”.

The developers also see this as an issue and score the municipalities’ ability to provide sufficient transparency during the evaluation as low (. question 4). The study by Jaselskis and Russell (Citation1992) recommend developing detailed specifications to manage project risks. Furthermore, the municipalities see value in developing a new process to incorporate inhabitants’ opinions when developing specification material, which would contribute to a more accurate specification process. However, this is not prioritised due to time constraints and general resource issues, which contrasts with the development trends of similar projects, according to Wong et al. (Citation2000). Moreover, the developers consider the municipalities’ decision to use the land allocation activity as their primary model as having a limited influence on the process itself (, question 1). Still, both municipalities and developers perceive the land allocation activity to be beneficial for building developments using wood solutions (, question 10 and , question 6). One developer commented, “Land allocation is an excellent process for the municipalities to control the building development in a specific direction, e.g. certain companies, design or material”. However, not having the ability to communicate expectations clearly, uncertainty regarding respective roles, and lack of transparency in the tender-based land allocation activity impacts the process negatively and is similar to concepts discussed by Dimitri (Citation2013), who mentioned careful design and evaluation as factors for a successfully managed process. Further, Caesar (Citation2016) also considers lack of transparency in the tender-based land allocation process a factor that would negatively influence the process.

Selecting phase

The municipalities’ insufficient structure in the specification process negatively influences the selection process, according to some developers in this study. The municipalities are relatively limited in their requirement profiles and normally leave it open for the developers to present their concepts and solutions regarding energy, environmental solution, availability etc. Doing so contradicts the positive impact of a defined evaluation structure supporting an overall process, as described by Fong and Choi (Citation2000). However, some municipalities express this as a deliberate strategy to use the land allocation process as a development tool for new enhanced building solutions, and where the municipalities’ focus is primarily on building design, all other issues are perceived to be dealt with by developers during the application for building permits. This perspective is confirmed by the limited importance placed on this area ( question 6). The process lacks in transparency, according to the developers, and is mainly based on the municipalities’ subjective evaluations. A developer mentions, “Feels like there is a lot of subjectivity and guessing from the municipalities’ side where expensive solutions, high quality and modern design have a better chance, contributing to a higher end-user cost”. According to Caesar (Citation2016), it can create a situation where small and financially weak developers are excluded from the process. Also, in certain circumstances, being awarded a contract is only based on the individual’s opinion at the time of evaluation, which one developer explained as, “The evaluation of land allocation projects is reflected through contradictory evaluations made for the same project at a different time by the same individuals within the municipalities”. This sentiment can be attributed to insufficient evaluation criteria for the projects and poor performance and knowledge by municipalities. Addo-Duah et al. (Citation2014) discussed it as contributing to limit the development potential of a project, i.e. wood-based building solutions.

It is distressing that an ad hoc and subjective process is applied, since Eddie and Heng (Citation2004) emphasise that contractor selection is the client’s main decision. A developer stated, “The municipalities need to follow a transparent evaluation method that increases confidence in their abilities using a stringent quality practice and standardised methods to provide similar evaluations irrespective of time or project”. Hence, the developers perceive that the municipalities’ current methods during their tender-based land allocation process restrict the development of wood-based building solutions due to their subjective selection process and knowledge, which can contribute to them choosing inferior solutions (, question 8). This structure contradicts the recommendations made by Fong and Choi (Citation2000), Dimitri (Citation2013) and Latham (Citation1994), highlighting the importance of a stringent evaluation process for all relevant aspects to fulfil defined project goals.

The evaluation process is something, according to municipalities, that must be improved and standardised to include quantifiable evaluation methods. Weele (Citation2010) and Dimitri (Citation2013), also emphasise the importance of stringent evaluation methods. Also, the developers perceive a need to change the tender-based land allocation process and reduce the uncertainty projected by municipalities (, question 10). Therefore, it could be beneficial to hold start-up meetings where developers are invited to ensure that the project material is understood. This was suggested by the developers as helpful for project fulfilment and shared by the municipalities that considered this adds value by minimising confusion. However, these meetings currently only take place to a limited extent in certain municipalities, which have indicated a limited focus on this topic (, question 8). This limited focus is in contrast with the importance that should be placed on these activities for a successfully implemented project, according to Ruparathna and Hewage (Citation2015). A municipality respondent stated, “This is not conducted today due to a great degree of subjectivity in the process, but I recognise that there would be a great value to develop this to further to enhance the quality derived from the projects”.

The municipalities are currently starting to pose specific requests favouring wood building solutions, including a greater environmental focus, where the tender-based land allocation process is seen as a useful tool to support this activity. Lindgren and Emmitt (Citation2017) mention that successful selection of a wood-based building solution is linked to an active political agenda to reduce environmental impact, which is furthered by an ability to pose specific requirements regarding the selection of building solutions. However, the statistical information gave a slightly contradictory result since the developers and municipalities scored this ability differently (, question 7 and , question 11). A municipality respondent said, “This is something that is useful and further provides an opportunity to push the development in a specific direction”, whereas a developer has an approach where “The municipalities can pose whatever requirements they want if these are the conditions for us to buy land and develop our solution”. Further, Van Valkenburg and Nagelkerke (Citation2006) and Atkinson and Sapat (Citation2012) discuss that a broader scope including, e.g. environmental impact assessments to create a comprehensive strategy are supported by the possibility to pose specific requests, as with the land allocation process, as beneficial for development.

Contracting phase

Contracts are awarded, according to the municipalities, based on the fulfilment of predetermined specifications communicated to the developers during the tender-based land allocation process. However, considering the municipality respondents’ previous statement regarding an insufficient process with limited standardisation based on subjective evaluations, objectivity is a challenge. Currently, this is a process that is in contrast to the recommendations by Latham (Citation1994) advocating the importance of having defined evaluation requirements for the contract selection phase, which, according to Jaselskis and Russell (Citation1992), also contribute to managing risk in the tender management process (Cheaitou et al. Citation2018). This is shared by a developer’s perception of the process, i.e. “This is not based on any clear evaluation criteria, which provides difficulties understanding why certain projects are being awarded an opportunity and also makes improvements of rejected projects difficult”.

According to the developers, municipalities also suffer from limited knowledge of evaluating solutions based on wood, which contributes to difficulties in developing wood-based solutions. Hence, the developers score this ability as low for the municipalities (, question 5). However, some municipalities included in this study try to mitigate the problem by contracting specialists, as one municipality explained, “We contact universities and external consultants to bridge the knowledge gap, facilitating a fair project evaluation”. This would, according to the municipalities, generate a higher degree of understanding regarding possibilities throughout the building process, which is supported by Weele (Citation2010) and Ncube and Dean (Citation2002), who emphasised the importance of using an evaluation method that creates opportunities for equal evaluations.

Reflections and conclusion

The purpose of this study is to provide an understanding of how the tender-based land allocation process is performed, providing transparency and improved project efficiency for developers to successfully respond in this process.

The tender-based land allocation process is an activity where municipalities can sell land to be used for building developments. The initial stage of this activity, the starting phase (Caesar Citation2016) is similar to the internal customer stage (), mentioned by Weele (Citation2010), Sanderson et al. (Citation2015) and Caesar (Citation2016), since both activities define the pre-conditions of what is required to be fulfilled by the project. The land allocation process is used during public building development and increases control, since municipalities are officially selling land to developers. Doing so avoids limitations defined in the Public Procurement Act (SFS Citation2016:Citation1145), i.e. restrictions in posing specific requirements regarding, e.g. material choice and design, which Caesar (Citation2016) stated was a positive effect when using the land allocation process that has no such limitations. For many new public housing developments, the decision-making process uses official statistics and planning tools, including demographic information and design strategies. However, the population’s requirements are not captured to the same extent, e.g. building standards and costs. Capturing this additional information would support the specification phase by understanding the population’s expectations.

The specification phase is considered a key activity that directly correlates to the project’s success, which is based on the defined requirements and information quality provided (Dimitri Citation2013). Hence, the work conducted at this stage reflects how well municipalities manage the project and to what extent it is communicated to developers. Currently, the municipalities’ specification phase lacks in structure and information quality, which is discussed by Lawal (Citation2012) as necessary for a successful process. The inferior quality in the specification phase could be derived from municipalities that see themselves as seller in the land allocation process, which is not an opinion shared by the developers in this study that consider themselves as sellers of building solutions. Therefore, the tender-based land allocation process should apply a structural model based on the procurement process for increased process transparency and structure, which would consider developers’ perception of the relationship with municipalities, i.e. that they have to comply with various demands made by municipalities to acquire land with the municipality’s intent to control the result, an activity defined by Weele (Citation2010), Corey (Citation1978), Sanderson et al. (Citation2015), and Lawal (Citation2012). Furthermore, unclear evaluation requirements pose problems for developers regarding how and to what they are to respond. Using the procurement process as a conceptual model to capture information in a standardised way allows developers to respond based on actual requirements rather than on their subjective interpretation of a specific situation, which is discussed by Arrowsmith (Citation2010) as negatively influencing the project outcome.

Insufficient structure also influences the selection phase, which results from the initial ad hoc specification phase where explicit project deliverables are absent (Caesar Citation2016). This makes it difficult for developers to comprehend project expectations, which is discussed in the study by Ncube and Dean (Citation2002) that highlights the importance of accurate information in the decision-making process. Further, this lack of structure is reinforced during the municipalities’ selection process, which favours design and quality levels beyond the initial project scope, based on the individual’s subjective perception of the proposed solution. If municipalities developed a process and communicated their project expectations, e.g. cost components, design elements, environmental factors at the beginning, it would support the overall process, similar to the models discussed by Sanderson et al. (Citation2015) and Corey (Citation1978). These components could be the basis for an evaluation structure with an equal comparison between the various proposals based on qualitative and quantitative elements, such as cost/m2 and fulfilment of design elements, providing an objective process for selecting the best solution (Eddie and Heng Citation2004).

The possibility of having a criteria-based method during the contracting phase would support the decision-making process and leverage the knowledge gap displayed by municipalities in this process. Hence, a method should be developed to evaluate the level of completion compared to the initially proposed solution (), which would be supported by the ability to capture information from previous projects. Furthermore, if municipalities have an ambition to develop wood-based building solutions, their knowledge of wood as a building material should be reflected to facilitate project delivery by all involved parties, as discussed by Addo-Duah et al. (Citation2014) and McKevitt et al. (Citation2012), who mentioned the importance of having appropriate knowledge about both the process and subject area for successful project fulfilment.

The study concludes that the municipalities, to a certain extent, follow a procurement-like process ( and ), i.e. they perform some of the activities but with limited structure, content and execution. The main problem is the municipalities’ inability to communicate their requirements and lack of sufficient knowledge to manage the process, as discussed by Weele (Citation2010), Corey (Citation1978) and Sanderson et al. (Citation2015). Further, the municipalities’ evaluations are based on individuals’ subjective opinions, which does not specifically support the development of wooden multi-family houses (Caesar Citation2016). Municipalities with a defined wood building strategy have made a strategic choice to include wood buildings as a requirement in their land allocation activity, which is a driver for increased use of wood in new building developments and an important factor for success according to Lundqvist and von Borgstede (Citation2008) and Hrelja et al. (Citation2015). However, this will not contribute to reducing uncertainty for developers, since municipalities continue to use subjective evaluation methods. Therefore, development towards qualitative and quantitative national standards, based on building specific requirements, will be required to improve the process and facilitate the development of sustainable building solutions.

Further studies should focus on understanding what suitable methods and tools are required to facilitate a criteria-based evaluation model similar to activities in a procurement process. This could include quantifiable evaluation measurements and an environmental life cycle focus. Furthermore, attention should be given to developing a material-independent evaluation solution, placing building specification in focus.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Addo-Duah, P., Westcott, T., Mason, J., Booth, C. A. and Mahamadu, A. (2014) Developing capability of public sector procurement in Ghana: An assessment of the road subsector client. Proceedings of Construction Research Congress, 19–21 May 2014, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, American Society of Civil Engineers.

- Albrechts, L. (2010) More of the same is not enough! How could strategic spatial planning be instrumental in dealing with the challenges ahead? Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 37(6), 1115–1127. doi: 10.1068/b36068

- Andersson, R. and Larsson, R. (2014) Så används stommaterial i flerbostadshus (This is how different framework materials are used in apartment buildings). Samhällsbyggaren (The Society Builder), (3), 32–35.

- Appiah, R. E. (2011) Building relevant skills for public procurement. E-Procurement Bulletin, 2(1), 1–6.

- Arrowsmith, S. (2010) Horizontal policies in public procurement: A taxonomy. Journal of Public Procurement, 10(2), 149–186. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-10-02-2010-B001

- Atkinson, C. L. and Sapat, A. K. (2012) After Katrina: Comparisons of post-disaster public procurement approaches and outcomes in the New Orleans area. Journal of Public Procurement, 12(3), 356–385. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-12-03-2012-B003

- Bailey, C. A. (2007) A Guide to Qualitative Field Research (2nd ed.). (London: Sage Publication ltd).

- Björheden, R. (2006) Drivers behind the development of forest energy in Sweden. Biomass and Bioenergy, 30, 289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2005.07.005

- Boone, H. N. and Boone, D. A. (2012) Analyzing Likert data. Journal of Extension, 50(2). [online]. Accessed 1 July 2019, available at: https://www.joe.org/joe/2012april/tt2.php

- Boverket [Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning] (2013) Bostadsmarknaden 2013–2014 (Housing market 2013–2014).

- Boverket (2015) Behov av bostadsbyggande – Teori och metod samt en analys av behovet av bostäder till 2025 (Requirement for residential construction – Theory and method as well as an analysis of the requirement for homes to 2025). [online]. Accessed 5 June 2016, available at: http://www.boverket.se/globalassets/publikationer/dokument/2015/behov-av-bostadsbyggande.pdf

- Boverket (2018) Vision för Sverige 2025. [Vision for Sweden 2025]. [online]. Accessed 5 November 2018, available at: https://www.boverket.se/sv/samhallsplanering/sa-planeras-sverige/sverige-2025/vision-for-sverige-2025/

- Caesar, C. (2016) Municipal land allocations: Integrating planning and selection of developers while transferring public land for housing in Sweden. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31(2), 257–275. doi: 10.1007/s10901-015-9457-2

- Caron, F., Marchet, G. and Perego, A. (1998) Project logistics: Integrating the procurement and construction process. International Journal of Project Management, 16(5), 311–319. doi: 10.1016/S0263-7863(97)00029-X

- Cheaitou, A., Larbi, A. and Al Housani, B. (2018) Decision making framework for tender evaluation and contractor selection in public organizations with risk considerations. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. doi: 10.1016/j.seps.2018.02.007

- Corey, R. (1978) Procurement Management: Strategy, Organisation and Decision-Making (Boston, MA: CBI Publishing Co).

- Dimitri, N. (2013) Best value for money in procurement. Journal of Public Procurement, 13(2), 149–175. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-13-02-2013-B001

- Eddie W. L. Cheng and Heng Li. (2004). Contractor selection using the analytic network process. Construction Management and Economics, 22(10), 1021–1032.

- Ellram, L. M. (1996) The use of case study method in logistics research. Journal of Business Logistics, 17(2), 93–138.

- EU (2011) COM 2020. Strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. [online]. Accessed 13 October 2016, available at: http://www.europeanpaymentscouncil.eu/index.cfm/knowledge-bank/other-sepa-information/european-commission-communication-europe-2020-a-strategy-for-smart-sustainable-and-inclusive-growth-march-2010-/

- EU (2012) COM 433. Strategy for the sustainable competitiveness of the construction sector and its enterprises. [online]. Accessed 15 October 2016, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/construction/competitiveness/index_en.htm

- Fong, S. P. and Choi, S. K. (2000) Final contractor selection using the analytical hierarchy process. Construction Management and Economics, 18, 547–557. doi: 10.1080/014461900407356

- Fredriksson, C. (2015) En processmodell för strategisk samhällsplanering: Forum – Arena – Court. Forskningsprogrammet Stadsregioner och utvecklingskraft (STOUT) [A process for strategic social planning: Forum – Arena – Court. Research program for urban areas and development force]. Rapport 2015:1. Stockholm: Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Institutionen för Samhällsplanering och miljö.

- Gustafsson, S. and Whilborg, E. (2016) Reflecting on collaborative networking and the roles of municipalities in local sustainable development. International Journal of Sustainability Policy and Practice, 12(2), 13–23. doi: 10.18848/2325-1166/CGP/v12i02/13-23

- Halldórsson, A. and Aastrup, J. (2003) Quality criteria for qualitative inquiries in logistics. European Journal of Operational Research, 144(2), 321–332. doi: 10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00397-1

- Healey, P. (2009) In search of the “strategic” in spatial strategy making. Planning Theory & Practice, 10(4), 439–457. doi: 10.1080/14649350903417191

- Hillier, J. (2011) Strategic navigation across multiple planes: Towards a Deleuzean-inspired methodology for strategic spatial planning. Town Planning Review, 82(5), 503–527. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2011.30

- Hrelja, R., Hjerpe, M. and Storbjörk, S. (2015) Creating Transformative Force? The role of spatial planning in climate change transitions towards sustainable transportation. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 17(5), 1–19. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2014.1003535

- Jaselskis, E. J. and Russell, J. S. (1992) Risk analysis approach to selection of contractor evaluation method. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 118(4), 814–821. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(1992)118:4(814)

- Kalbro, T. (2000) Property development and land-use planning processes in Sweden. In K. Böhme, B. Lange, and M. Hansen (eds.), Property Development and Land-Use Planning Around the Baltic Sea (Stockholm: Nordregio), pp. 95–110.

- Kang, V. and Groetelaers, D. A. (2018) Regional governance and public accountability in planning for new housing: A new approach in South Holland, the Netherlands. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(6), 1027–1045.

- Koskele, L. (2003) Is structural change the primary solution to the problems of construction? Building Research & Information, 31(2), 85–96. doi: 10.1080/09613210301999

- Kvale, S. and Brinkmann, S. (2009) InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing (London, Great Britain: SAGE Publication Ltd).

- Lamptey, J. L. and Elle, L. (2000) Evaluation Ghana Joint evaluation of the road sub-sector programme 1996–2000, [online]. Accessed 25 February 2018, available from: www2.jica.go.jp/ja/evaluation/pdf/2000_GH-P12_4_f.pdf

- Latham, M. (1994) Constructing the Team. Final Report of the Joint Government/Industry Review of Procurement and Contractual Arrangements in the United Kingdom Construction Industry (London: Stationery Office Books, HMSO).

- Lawal, S. (2012) Procurement process design: A case study of Blissfulminds Nigeria Limited, Häme Univiersity of Applied Sciences.

- Lindgren, J. and Emmitt, S. (2017) Diffusion of a systemic innovation a longitudinal case study of a Swedish multi-storey timber housebuilding system. Construction Innovation, 17(1), 25–44. doi: 10.1108/CI-11-2015-0061

- Likert, R. (1932) A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140, 1–55.

- Lucero, J., Wallerstein, N., Duran, B., Alegria, M., Greene-Moton, E., Israel, B., Kastelic, S., Magarati, M., Oetzel, J., Pearson, C., Schulz, A., Villegas, M. and White Hat, E. R. (2016) Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12(1), 55–74.

- Lundqvist, L. and von Borgstede, C. (2008) Whose responsibility? Swedish local decision makers and the scale of climate change abatement. Urban Affairs Review, 43(3), 299–324. doi: 10.1177/1078087407304689

- Malterud, K. (2012) Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(8), 795–805. doi: 10.1177/1403494812465030

- McCrudden, C. (2007) Buying Social Justice: Equality, Government Procurement and Legal Change (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press).

- McCue, C. and Gianakis, G. (2001) Public purchasing: Who’s minding the store? Journal of Public Procurement, 1(1), 71–95. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-01-01-2001-B002

- McKendall, M. A. and Wagner, J. A. (1997) Motives, opportunity, choice and corporate illegality. Organizational Science, 8(5), 1–24.

- McKevitt, D., Davis, P., Woldring, R., Smith, K., Flynn, A. and McEvoy, E. (2012) An exploration of management competencies in public sector procurement. Journal of Public Procurement, 12(3), 333–355. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-12-03-2012-B002

- Mertens, D. M. (2012) Transformative mixed methods: Addressing inequities. American Behavioral Scientist, 56, 802–813. doi: 10.1177/0002764211433797

- Ncube, C. and Dean, J. C. (2002) The limitations of current decision-making techniques in the procurement of COTS software components. In International Conference on COTS-Based Software Systems. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Novack, A. R. and Simco, W. S. (1991) The industrial procurement process: A supply chain perspective. Journal of Business Logistics, 12(1), 145–167.

- Poulsen, B. (2009) Competing traditions of governance and dilemmas of administrative accountability: The case of Denmark. Public Administration, 87(1), 117–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00727.x

- Prier, E., McCue, C. and Behara, R. (2010) The value of certification in public procurement: The birth of a profession. Journal of Public Procurement, 10(4), 512–540. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-10-04-2010-B002

- Ruparathna, R. and Hewage, K. (2015) Sustainable procurement in the Canadian construction industry: Current practices, drivers and opportunities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 109, 305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.007

- Sanderson, J., Lonsdale, C., Mannion, R. and Matharu, T. (2015) Towards a framework for enhancing procurement and supply chain management practice in the NHS: Lessons for managers and clinicians from a synthesis of the theoretical and empirical literature. Health Services and Delivery Research, 3(18), 1–134. doi: 10.3310/hsdr03180

- SKL (2014) Nya regler om exploateringsavtal, markanvisningar och kommunala särkrav på byggandet. Cirkulärnr. 14:36. [online]. Accessed 21 December 2017, available at: http://brs.skl.se/cirkular/cirkdoc.jsp?searchpage=brsbibl_cirk.htm&op1=&type=&db=CIRK&from=1&toc_length=20&currdoc=1&search1_cnr=14:36

- Song, L., Mohamed, Y. and AbouRizk, S. (2009) Early contractor involvement in design and its impact on construction schedule performance. Journal of Management in Engineering, 25(1), 12–20. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0742-597X(2009)25:1(12)

- Swedish legislation and regulation:

- •SFS 1915:218, Lag om avtal och andra rättshandlingar på förmögenhetsrättens område, [The Act of Contracts], Stockholm.

- •SFS 1991:900, Kommunallagen, [The Swedish Local Government Act], Stockholm.

- •SFS 1998:808, Miljöbalken, [The Swedish Environmental Code], Stockholm.

- •SFS 2010:900, Plan- och bygglagen, [The Planning and Building Act], Stockholm.

- •SFS 2014:899, Lag om riktlinjer för kommunala markanvisningar, [Act on Guidelines for Municipality Land Allocations], Stockholm.

- •SFS 2016:1145, Lagen om offentlig upphandling, [The Public Procurement Act], Stockholm.

- •BFS 2011:6, Boverkets byggregler, [Boverket’s Building Regulations], Stockholm.

- Tassabehji, R. and Moorhouse, A. (2008) The changing role of procurement: Developing professional effectiveness. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 14(1), 55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pursup.2008.01.005

- TMF (2018) Andel nybyggda lägenheter med stomme av trä 2017 [Number of newly built apartments using a wood frame 2017]. [online]. Accessed 23 January 2019, available at: https://www.tmf.se/siteassets/statistik/branschstatistik/trahus/flerbostadshus/tmf-andel-tra-sammanstallning-2018.pdf

- Tudor, T., Adam, E. and Bates, M. (2007) Drivers and limitations for the successful development and functioning of EIPs (eco-industrial parks): A literature review. Ecological Economics, 61, 199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.10.010

- Upphandlingsmyndigheten (The national agency for public procurement) (2017) Hållbarhet, [online]. Accessed 26 September 2017, available at: http://www.upphandlingsmyndigheten.se/hallbarhet/

- Van Valkenburg, M. and Nagelkerke, M. C. J. (2006) Interweaving planning procedures for environmental impact assessment for high level infrastructure with public procurement procedures. Journal of Public Procurement, 6(3), 250–273. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-06-03-2006-B003

- Wallerstein, N. B., Yen, I. H. and Syme, S. L. (2011) Integrating social epidemiology and community engaged interventions to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 822–830. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140988

- Weele, A. J. (2010) Purchasing and Supply Chain Management: Analysis, Strategy, Planning and Practice (5th ed.). (Andover: Cengage Learning). ISBN 978-1-4080-1896-5.

- Whitten, J. L., Bentley, L. D. and Dittman, K. C. (2004) Fundamentals of System Analysis and Design Methods (6th ed.). (Boston, USA: McGraw-Hill Irwin).

- Wong, H. C., Holt, G. and Cooper, P. A. (2000). Lowest price or value? Investigation of UK construction clients’ tender selection process. Construction Management and Economics, 18(7), 767–774. doi: 10.1080/014461900433050

- Yin, R. K. (2014) Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Los Angeles: Sage Publications).

- Yoshikawa, H., Weisner, T. S., Kalil, A. and Way, N. (2013) Mixing qualitative and quantitative research in developmental science: Uses and methodological choices. Qualitative Psychology, 1, 3–18. doi: 10.1037/2326-3598.1.S.3