Abstract

This publication presents the research results concerning determination of the level of landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries. The research focused upon 20 structures located within the area of Poland, Great Britain and Austria. The research used procedures of landscape attractiveness assessment which features three research methods: survey method with the use of the semantic differential, the method of point bonitation and the landscape entropy method. Throughout the analysis conducted, the level of landscape attractiveness of the quarries was determined according to four classification groups: very attractive quarry landscape (I), attractive quarry landscape (II), little attractive quarry landscape (III) and unattractive quarry landscape (IV).

Introduction

The necessity of acquisition of resources indispensable for production of materials used in many branches of industry has become the main factor determining the landscaping [Citation1–3]. The landscape forms occurring as the result of rock mining have caused interference in the environment, creating new values that could constitute a vital element of tourist interest. Obviously, as quite specific landscape forms, quarries might be perceived by individuals as more or less attractive.

If we suppose they may be perceived attractive in many respects, then their location in the vicinity of key tourist routes may raise the region tourist attractiveness. They may be a sort of a side attraction, used successfully to liven up local tourism. For among the newly created modern tourist forms, geo-tourism and industrial tourism have now developed. People interested in such a kind of sightseeing will look for new stimuli, new challenges as well as new points of interest [Citation4,5] and hence new attractions aim to meet all these requirements. Cultural structures like monuments and museums are not enough in such cases. New tourism refers to the evolution of new form of attractions, which is the 3×E rule (entertainment, excitement, education) that is displacing the traditional 3×S formula (sun, sea, sand) [Citation6].

Another crucial element here is the tourist attractions built up on their cultural heritage. Heritage is such an element of legacy that may be evaluated to assess its value. The UN Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage [Citation7] recognises the cultural heritage as monuments of architecture, sculpture, painting, objects, archaeological structures, cave dwellings and highly valuable elements. Using cultural heritage as an attraction is practised more frequently and continually. This is a background for geoparks and geo-tourism popularisation, which are forms of cognitive tourism also called global tourism [Citation4,8–10].

Geo-tourism is related to exploring and means recognising geological attractions and active participation in discovering interesting forms, rocks, minerals and landscape features [Citation4]. Moreover, naturalists claim that a morphologically differentiated landscape is the most precious for tourism and recreation [Citation11]. Thus, in the areas of abandoned quarries with unique forms and geological constructions discovered during material exploitation, as well as located in natural protected areas, there is a combination of natural, geological and industrial values alongside those of industrial tourism (post-industrial).

At the same time, there has been a lack of research supporting such reasoning. It is important to emphasise that the quarry, as a specific form of landscape, can be received by individuals as more or less attractive. It is therefore necessary to study the attractiveness of such areas after their exploitation [Citation1,12–14]. Any such study should account for elements like landscape features and the state of quarry preservation with its contrast, road accessibility and development progress, as well as social preferences and social acceptance of such structures. The aim of this article is thus to show the attractiveness of the landscape of abandoned quarries and to demonstrate public interest for these structures in terms of their attractiveness.

Methodology and research area

To conduct the research concerning the landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries, a procedure appropriate to quarry attractiveness assessment was used [Citation12]. This procedure includes three research methods, subject to proper modifications:

| • | Use of a survey method based on semantic differential as the type of measuring scale used for the assessment of connotations, which allows quantitative assessment to be conducted in accordance with the meaning of the defined concepts for various groups [Citation15,16]. | ||||

| • | Evaluation of the number of signals coming from the landscape through the assessment of landscape entropy conducted according to field research, whose results allow the units to be grouped according to the number of existing stimuli in the area. | ||||

| • | Use of the method of point bonitation which separates the physical environment and anthropogenic elements as carriers of possible values from the quarry landscape area with the objective of determining their attractiveness. | ||||

In the survey method, the questionnaire was aimed at the following: determining the connotations of the word quarry; determining the distance covered by the surveyed to get to the abandoned quarry area; frequency of use; and diagnosing the values through the attractiveness evaluation based on the choice of negative or positive features of the analysed structures.

One important aspect of the method is its ability to select the human factor in the attractiveness evaluation and human feelings applicable to this area [Citation1]. The semantic differential is a type of a measuring scale used to assess connotations. This process was presented by Osgood (op. cit.) by means of a simplified model composed of three stages: (I) – a stimulus which enters human consciousness and is recognised as a sign indicating a certain feeling on the part of an individual; (II) – positive or negative word expression and comparing it to the current event; (III) – staying in or leaving a specific place, depending on positive or negative stress. The distinguishing feature of this method is a scale whose outermost points are presented in the form of two antonyms: bad–good, inexpensive–expensive, useless–useful, etc. [Citation6,15,17].

Between those extreme characteristics, there are a few intermediate categories marked implicitly with natural numbers. The use of contrary definitions creates a point scale of marks. The form of analysis used subsequently involves drawing the graphic profile. It is made by connecting with a line the numbers achieved by the structure analysed on each evaluation scale [Citation6,18].

According to the entropy, the landscape should be perceived as a multi-sensory unit. The multi-sensory landscape is an existing structural and territorial reality perceived with senses, while it provides a set of signals through channels, making them the stimuli for receptors [Citation19,20]. The existence of signals is conditioned by landscape’s structure and functioning [Citation21]. The potential sources of signals coming from a quarry landscape are then received through the senses of sight, hearing, smell and touch. The most information received by human is by sight (80–90%) while the other senses receive 10–20% of information.

Therefore, the received signals may be divided into two groups: the ones perceived with the sight (I) and those perceived with the other senses (II). Assuming that a source may send 19 different (positive or negative) messages, thereafter marked as 1, 2……19 for the reasons of simplicity. It was assumed that messages are divided into two groups: I: 1–9 and II: 10–19. The occurrence of signals from group I is equally probable as in the case of group II.

Messages 1–9 are equally probable while messages from II group form three equally probable subgroups: IIA (10–13), IIB (14–17), IIC (18,19). The probability of the occurrence of messages in groups IIA, IIB and IIC is assumed to be equal. The signals sent by a landscape are hereafter referred to as notices. If the sent signal is received by sight then 1 of 9 notices will take place, while when the signal form the second group appears, only 1 of 10 notices will take place [Citation1]. This division is shown in Figure .

The probability of presence of the signals is conditioned by the component characteristics of the landscape, which are accepted signal sources. Therefore, if a landscape has the capacity to transmit n-number of signals – in this case 19 – with the probability of occurrence p

i

, and i = 1,2…n, then the weighted average number of information coming from the landscape (the information entropy of information source) may be counted using the formula [Citation19]:

Drawing conclusions from this entropy research, three types of landscape can be isolated (Table ). Due to this categorisation, we can deduce whether given the extent of the stimuli of a potential landscape, it may appear attractive for tourists and encourage them to come back to one place rather than the other. The closer to 0 the entropy rate, the less emotions it will elicit and one can assume that it is less attractive.

Table 1. The entropy rate [after 1].

This method of point bonitation adopts the scale showing the relation between the adopted natural or landscape variable and the number of points [Citation22]. Generally, points are assigned to imaginary fields. What is more, this method assumes that the following criteria form the basis for classification and evaluation of physio-geographical phenomena [Citation12]. These are:

| • | vertical differentiation of the area – indicator influencing values of a particular area, determining a flexible value and utility in relation to different activities. On the basis of height differences calculated from the centre of a quarry, particular heights are then assigned to pre-determined factor values:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If there are considerable height differences occurring in a quarry (different height at every wall), then we offer the calculation a point value from the following formula:

where: W p – indicator of vertical differentiation of the quarry; P n – percentage of quarry slope area of certain n height; T n – point predictor of vertical differentiation of the area of n type.

| • | percentage of natural succession – it was assumed that the quarries with strong natural succession would obtain a small number of points, since the vegetation covers interesting morphological forms developed as the result of mineral mining:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | state of quarry preservation – well-preserved quarries of low natural succession and with interesting geological exposures will be components of significant tourist interest: good – 2 points, average – 1 point, bad – 0 point. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | boundary contrasts for a particular type of land cover – quarries with strong natural succession demonstrate little contrast in relation to adjacent areas (forests, fields, pasturelands and meadows) and the tourist will find a more contrasting area more attractive (Table ) [Citation12]. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | number of adjacent area types – depending on several area types adjacent to the quarry, the points are as follows: 3 and more – 3 points, 2 – 2 points, 1 – 1 point, lack of differences between the quarry and adjacent area – 0 points. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If one quarry borders with many types of adjacent areas, the points were awarded according to the formula:

where: W k – indicator of boundary contrasts; L n – percentage of the area bordering with n-type area; K n – point-indicator of contrasts for the border with n-type area.

| • | presence of surface waters – the tourist will be more attracted to areas with surface water thanks to a wider range of possibilities making the place more attractive regarding tourism:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | road and tourist routes accessibility – the better the accessibility to the quarry the more points are given: good – 2 points, average – 1 point, very aggravated – 0 points. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 2. Indicator of boundary contrasts for particular types of land cover [after 1 and 12].

Additionally, this method proposes awarding 1 point if the quarry has a form of nature conservation established since this can have a considerable influence on tourists’ willingness to visit the quarry and frequency of the visits. What is more, the research study should take a negative anthropological factor into account which can have a considerable influence on the perception and evaluation of a quarry. In each of the structures analysed which one notices the presence of disfiguring anthropogenic structures which should be given a negative point (−1 point). A parallel situation should take place in the case of structures located at busy streets or operating processing plants.

Finally, the procedure of evaluation of the landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries (AKK) consists of the summary assessment of individual criteria, according to the formula:where: AKK – quarry landscape attractiveness; W

p

– vertical differentiation indicator; W

sn

– natural succession influence indicator; W

sz

– quarry preservation state indicator; W

k

– boundary contrasts indicator; W

g

– indicator of the number of adjacent area types; W

w

– surface water presence indicator; W

d

– road, route accessibility indicator; W

a

– the respondents’ evaluation indicator; W

e

– entropy evaluation indicator; W

o

– indicator of areas subjected to legal protection; W

n

– indicator of human unfavourable activity influence.

The final result of the application of this procedure is the four classification groups of the landscape attractiveness of inactive quarries (Table ).

Table 3. Landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries – classification groups [after 12].

The quarries of the I group should present very attractive landscape. Their characteristic features are: good condition, meaningful vertical differentiation, not advanced level of natural succession, significal visual contrast with surrounding areas, very good road accessibility and the occurrence of surface waters, which is another element increasing the attractiveness and augmenting chances for the quarry utilisation. They should also present a high level of entropy.

The typical features of unattractive quarries (group IV) are very little vertical differences in morphology, high level of natural succession and very poor conditions. They are not contrastive with the surrounding areas, which makes them almost invisible, and remain inaccessible by local roads. Hence, the marks given them by the respondents and the entropy marks are very low. The quarries from this group are not vividly differentiated and are not perceived as interesting and potentially useful.

The attractive quarry landscapes (group II) usually have a lesser vertical differentiation, while the pace of natural succession is a little faster, entailing that some precious and interesting geological profiles are covered. Furthermore, not all the quarries of that group have surface waters in their area. Road accessibility is good, while the marks of both the respondents and entropy are also at a high level. In addition, they are legally protected.

The quarries of a little attractive landscape (group III) have elements which decrease their final evaluation. They have undifferentiated morphology and access to them is hindered due to the pace of natural succession. Moreover, most of them do not possess surface waters and are not contrastive to surrounding areas. The marks of the respondents are much lower, while the entropy indicator also points to a much lower probability of occurring various stimuli. However, the areas have great potential if the right efforts are undertaken; for example, those aiming at decreasing the pace of natural succession or improving road accessibility [Citation1,12].

The research area

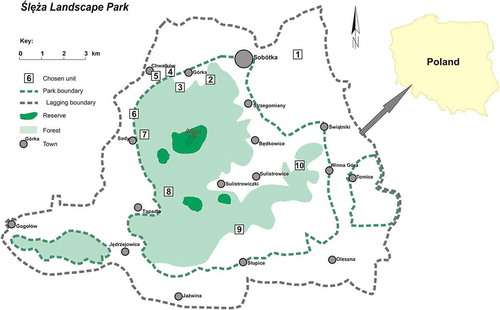

Research on the landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries was conducted in 20 structures located in the areas of 3 countries: Poland, Great Britain and Austria. For specific research, there were selected 10 Polish units (quarries) located in the region of the Ślęża Landscape Park and its buffer zone, where minerals like granite, gneiss, gabbro or serpentinite were exploited (Figure ). The area of the Ślęża Landscape Park was chosen due to the large diversity of its values. This is the area where numerous abandoned quarries are located and where the beginnings of stone exploitation date back to the bronze age. Moreover, these quarries are characterised by the richness of morphological forms, natural succession and interesting history. All these aspects, together with other values of the studied area are good examples demonstrating the landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries.

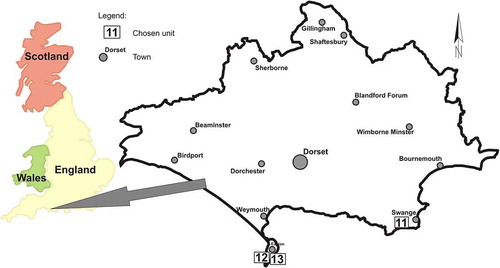

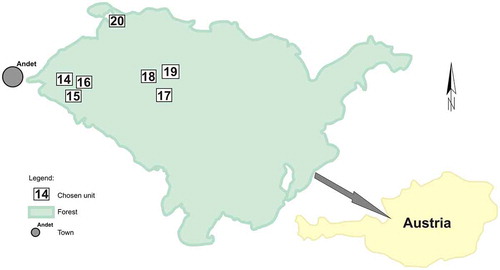

To analyse the issue more deeply, comparative studies were conducted in 10 more quarries located in Great Britain on the Jurassic Coast in Dorset county (3 limestone quarries) and 7 limestone quarries located west of Adnet in Austria (Figures ). In terms of their history and geology, the selected quarries are adequate examples in relation to those from Poland. Moreover, they are all protected by various forms of landscape protection.

The structures subjected to the research are all located in the Ślęża Region. Eight of the selected quarries are located in the Ślęża Landscape Park, and two within the borders of its buffer zone (Figures and ). The units have a different stage of preservation, from open access to partial or poor reception, with or without surface water, with advanced or poor natural plant succession, with steep or mild rock walls and with or without access to the local roads. It should be noted that the Ślęża Region is an area frequently visited by tourists, but abandoned the quarries we analysed there are not yet prepared for tourism.

As comparative units for checking the procedure of the landscape attractiveness evaluation of the abandoned quarries, 10 quarries were selected from Great Britain in the county of Dorset, located in the south of the country (No. 7–8) and Austrian units located in the Adnet region (No. 9–10). These quarries characterise different average condition, almost vertical walls which are eagerly used for climbing, accessible local roads, visibly marked terraces, different stage of natural plant succession with the occurrence of both groundwater and surface water (Figures ).

The areas were selected because, just like the Ślęża Region, they are famous for their rich history of rock minerals excavation with similar methods and are subjected to many forms of landscape protection. Meanwhile, in Great Britain and Austria they are precious for tourism and are local attractions. These structures are included in the existing hiking trails. The tourists visiting these sites can learn from the standing panels about the history of mining, local geology, species of fauna and flora living there and (what is not of less importance) about the impact and importance of the quarry on local life.

Research results

The sample for the survey were tourists and inhabitants of the neighbouring towns visiting the selected quarries. The sample group of 1000 people asked for the survey were tourists and inhabitants of neighbouring towns who visited these quarries. The choice of the group members was fully accidental and the survey was anonymous. The questionnaire thus pursued the following aims: to define the connotations of the word quarry; determine the distance covered by the surveyed to get to the abandoned quarry area and the frequency of use; diagnose the values through the attractiveness evaluation based on the choice of negative or positive features of the analysed quarries.

At the end of the questionnaire there was a blank for filling in with sex, age, social status, that let gather the information about the respondents (Figure ). The surveys were conducted in the years 2010–2012.

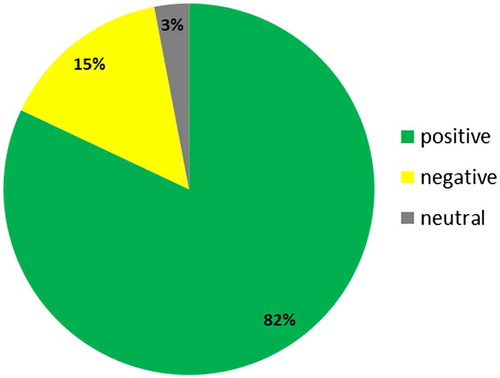

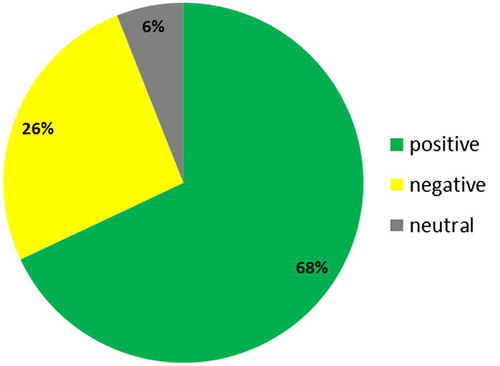

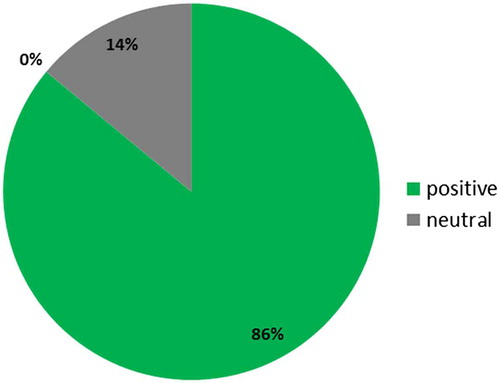

Among the respondents surveyed, 82% of them in Poland have positive associations with the word ‘quarry’, in England 68%, and in Austria, 86% (Figures ). Negative association expressed only 3% of respondents from Poland and 6% from England. These findings were of great importance because the negative or positive association causes the desire or lack thereof to visit such a place. Confirmation of this is also the answer of respondents to the question about the distance of their travel to the quarry.

In Poland, 40% of the interviewees overcomes distance from 11 to 50 km, while in England 26% and in Austria 30%. Distances greater than 50 km declare 62% of respondents from Austria, 2% from England and 26% from Poland. Respecting the frequency of use of inactive quarries, 22% of Poles declared using them once or twice a year, while in England this number is 56% and in Austria 42%. However, twice a week and more often, old quarries are used by 44% of the interviewees in Austria, 10% in England and 22% in Poland.

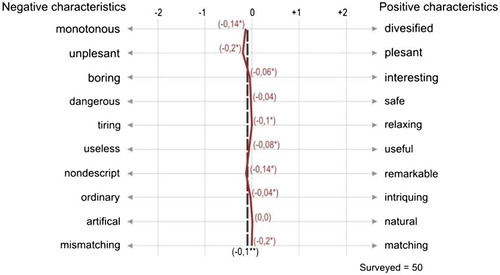

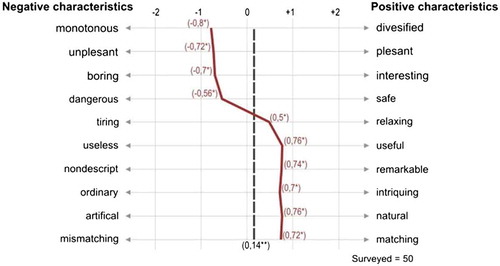

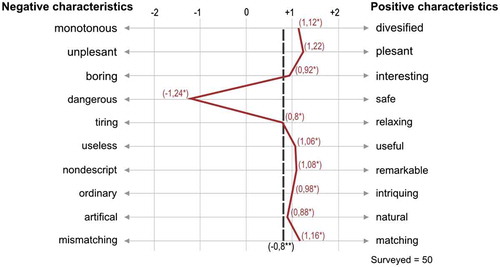

With regard to the survey answers, polarised graphic profiles were created for evaluative characteristics of every analysed structure, as well as an average mark for all analysed quarries from every single region. Examples of graphic profiles are shown in Figures .

The research survey proved that in the Ślęża Region, the lowest mark was achieved by the quarries covered with dense vegetation and without high excavation walls. Furthermore, their accessibility for tourists has also been hampered. They are evaluated as monotonous, unpleasant, boring, useless and discordant. Different marks were received by the quarries whose excavation walls are high and which are scarcely influenced by natural succession and easily accessible by tourists – they are assessed as differentiated, interesting, intriguing, distinctive, concordant and natural.

The quarries in Dorset county were, in turn, marked high by the respondents. Firstly, they were evaluated as differentiated, pleasant, intriguing natural and concordant. One of the quarries got poor marks and was perceived as dangerous due to its location by the shoreline of steep cliffs. They have also evaluated limestone quarries positively in the Adnet Region in Austria, which received high marks, especially for differentiation and concordance with the neighbourhood. Furthermore, they were assessed as pleasant, relaxing and natural. Only two quarries got poorer marks (No. 16 and 19). The first quarry here had only an average state of preservation and meaningful influence of natural succession masking interesting forms. Due to its bad condition and lack of characteristic features, the other one was perceived as monotonous and unpleasant.

Basing on the respondents’ evaluation, six-point groups were created. The 70% studied units were then assigned to the partition between 0.60 points and 1.29 points, getting high scores, and another 30% to the partitions: −0.60 points to −0.09 points, and −0.10 points to 0.59 points. None of the units was qualified to the lowest point group with solely negative features (Table ).

Table 4. The number of units resulting from the respondents’ average evaluation.

The survey based on the evaluation of the entropy of information sources enabled us to categorise the quarries into three groups, which was related to the intensity of emitted stimuli. The biggest number of the quarries (12) was in the second group – moderately stimulating landscapes (Table ). Another seven were qualified to strongly stimulating landscapes. The results show that the quarries are areas emitting many stimuli and thus affecting all the senses.

Table 5. The number of units resulting from the entropy divisions.

In each of the quarry elements studied, they operated in the sense of both sight and smell, but hearing and touch were noted. In the first group, quarries were classified according to characteristics such as a varied morphology, a large variety of colours, the occurrence of geological outcrops, interesting effects of a play of light and shadow, the changing look and feel throughout the day and night, the variability due to the change of seasons, the occurrence of surface water and plants. By the presence of water and vegetation, it results in additional effects like the sound of running water, a touch of plants and the habitation of various animals.

The point of using the point bonitation method in the procedure of evaluation of the landscape attractiveness is to isolate from the area of the quarry landscape the elements of physical and anthropogenic environment as carriers of possible values and so evaluate their attractiveness. The evaluation criteria accepted for the method has been described in the research methodology section. It is worth noting that additional points were also assigned for the protection of the forms existing in the area. The afore-mentioned protection may meaningfully affect the will and frequency of tourist visits to the quarries, while treating them as another attraction worth seeing. Therefore, every quarry was subject to a form of protection was assigned an additional point.

The research also took into consideration the negative anthropogenic impact which may affect the perception and evaluation of the quarry considerably. Consequently, in terms of the structures analysed, each received −1 point where disfiguring architectural elements were marked, like the remains of fencing or household rubbish. The same evaluation was implemented for the structures located by busy roads or by operating processing plants.

Detailed results of the conducted survey research, entropy measurement and criteria measurement with point bonitation are presented in Table . Based on the analysis, the quarry landscapes were assigned to four classification groups (Table ). The point scale was determined according to the research on the abandoned quarries presented above in this article.

Table 6. Detailed results of the evaluation of the landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries.

Table 7. Classification groups for the evaluation of the landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries.

In terms of group I, 15% of all audited quarries have been qualified. All of them are have all attributes required for this category of landscape attractiveness. Furthermore, the survey results also point to a meaningful interest in these areas where they are perceiving them as interesting, differentiated and forming natural landscape elements. Their characteristic feature is the highest entropy indicator, which classifies them as strongly stimulating structures. Moreover, they are located in areas protected in one or multiple ways. These nine quarries belong to the group II of the landscape attractiveness, which represent 45% of the total.

Meanwhile, the quarry landscapes with little attraction (group III) have elements which decrease their final evaluation. Here, 25% of the studied quarries were placed in this attractiveness group. Due to the significant progress of natural succession which camouflages the shape of the quarry, it is neglect of these places and the lack of local roads and trials what makes them difficult to locate which explains why they have received a low score and were classified as unattractive (group IV). These are characteristics of 15% of the analysed structures.

The attractiveness studies in the Ślęża Region proved that two units are the attractive quarry landscapes (II group) and another two were evaluated as very attractive quarry landscapes (I group). Three units were evaluated as quarry landscapes (III group) with little attraction due to the major influence of natural succession that covers the evidence of the quarries and for general negligence of the area. The unattractive, negatively evaluated quarries (3 units) received low marks due to major natural succession influence, lack of accessibility and difficulties with their localisation. In our opinion, minor works like setting routes, marking the place, introducing some information in guides would raise the final mark dramatically.

The quarries selected for the study from Great Britain and Austria are very popular among tourists as they have major landscape attractiveness. As many as seven units were marked as the attractive quarries (I group), while one was judged very attractive (II group). None of the quarries was evaluated as having an unattractive landscape. However, two units were qualified as the little attractive.

For years, the quarries in Great Britain have been used successfully as climbing destinations, walking areas or didactic places. Local authorities that noticed their potential, use them successfully and encourage people to visit the quarries during events, concerts, art exhibitions and other cultural possibilities to be organised there. In the meantime, tourists may admire the material extracted from the quarries – in Austria, it was limestone of unique colours and structure. Moreover, the signboards inform the visitors about the history of extraction, the geological structure, the existing species of fauna and flora, as well as the influence and meaning of the quarries on local life.

The results of this research study and the application of the procedure for the assessment of landscape attractiveness of inactive quarries have confirmed our hypothesis. In fact, 70% of the studied sites have been qualified as belonging to groups I and II of landscape attractiveness. This finding entails that the quarries preferred are those providing the observer with significant information and emotions due to the diversity of their features.

It should be also noted that the quarries from Great Britain and Austria are already being used successfully as interesting tourist attractions. Quarries in Poland may be attractive, but they are not currently being used for tourism. Hence, activating these areas in accordance with the public interest seems appropriate. In such areas development prospects must be sought, while their values should be used for the development of hiking, biking, horseback riding, climbing or diving.

Summary

Taking up the issue of the landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries, we set out to obtain information across as broad an area as possible as to whether the landscape attractiveness of quarries exists and how it may increase the attractiveness of the region. The units analysed were located in the Ślęża Landscape Park in its integral part. They are evidence of rich mining history in the area and its historic heritage.

Hence, unique wildlife, unusual geological phenomena, historic and cultural values determine the bright future of the area as a tourist resort. Studies show that inactive quarry shows landscape attractiveness because from the analysis of the surveys conducted, it can be concluded that just a small percentage of people see such sites in a negative way. Most people declared that they use quarries relatively often i.e. once or twice a week and sometimes more frequently. The respondents called the quarries diverse, interesting, enjoyable, harmonious and intriguing. It is interesting that they also recognised quarries to be a natural, not anthropogenic. Hence, they did not see the quarries as a disharmonious element in nature, but as enriching its structure.

In economic terms, the attractive quarry landscapes may be used as additional elements or side attractions to appeal to more tourists. Furthermore, the areas may be used for universal social education as a particular feature or made into a didactic place that may be incorporated into programmes of recreational and educational trips, science and ecology classes. Implementing this idea requires the promotion of quarry landscape, elaborating a guide and proper marking of the places in the area. Similar to Austria, a route network along the former quarries may come into existence with the history of extraction, technology and tools, etc. In Adnet, this idea is clearly recognised and popular among tourists.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by Statute Research Studies [order S50099 and 0401/0124/16].

References

- E. Baczyńska , M.W. Lorenc , and U. Kaźmierczak , The landscape attractiveness of the abandoned quarries , Geoheritage, preprint (2017), submitted for publication. Available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12371-017-0231-6. DOI: 10.1007/s12371-017-0231-6.

- U. Kaźmierczak , P. Strzałkowski , and M. Baszczyńska , Natural, geotouristic and recreation attractiveness in post-mining areas , in XXVII International Mineral Processing Congress, J. Yianatos , ed., Santiago, 2014, pp. 10–20.

- J. Górniak-Zimroz , U. Kaźmierczak , and J. Malewski , Ecological aspects of mineral extraction in the Bystrzyca river area , Bezpieczeństwo Pracy i Ochrona Środowiska w Górnictwie 6 (2005), pp. 39–41. (in Polish).

- P. Różycki , Geotourism and industrial tourism as the modern forms of tourism , Geoturystyka-GeoTourism 3–4(22–23) (2010), pp. 39–50.

- A. d’Hauteserre , Affect theory and the attractivity of destinations, Ann. Tourism Res. 55 (2015), pp. 77–89.10.1016/j.annals.2015.09.001

- Z. Kruczek , Tourist Attractions. Phenomenon, Typology, Research Methods , Publishing House Proksenia, Kraków, 2001. (in Polish).

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Adopted by the General Conference at its seventeenth session Paris, 16 November 1972.

- K. Tokarczyk-Dorociak , M.W. Lorenc , B. Jawecki , and K. Zych-Głuszyńska , Post-industrial landscape transformation and its application for geotourism, education and recreation – an example of the Wide Mt. near Strzegom, Lower Silesia/Poland, Z. Dtsch. Ges. Geowiss. 166(1) (2015), pp. 195–203.10.1127/zdgg/2015/0018

- D. Light , Heritage as informal education , in Heritage, Tourism and Society, D. T. Herbert , ed., Mansell, London, 1995, pp. 117–145.

- R.W. Saaty , Identification and definition of regions in Greek tourist planning , Reg. Sci. Assoc. 18 (1987), pp. 167–176.

- J. Chwastek , W. Janusz , and J. Mikołajczyk , Natural values of open-pit mining , Surf. Mining 39 (1998), pp. 49–60. (in Polish).

- E. Baczyńska , Procedure for evaluation of the attractiveness of the quarries’ landscape , in GEOTOUR: International conference on Geotourism, Mining Tourism, Sustainable Development and Environmental Protection, F. Ugolini , V. Marchi , S. Trampetti , D. Pearlmutter , and A. Raschi eds., Florence, 2016, pp. 215–222.

- N. Shoval and A. Raveh , Categorisation of tourist attractions and the modelling of tourist cities: based on the plot method of multivariate analysis , Tourism Manag. 25 (2003), pp. 741–750.

- A. Lew , A framework of tourist attraction researches , Ann. Tourism Res. 14 (1987), pp. 55–575.

- C. Osgood , G. Suci , and P. Tannenbaum , The Measurement of Meaning , University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1957.

- C.R. Kothari , Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques , 2nd ed., New Age International Publishers, Delhi, 2004.

- E. Babbie , The Practice of Social Research , 13th ed., Wadsworth, Belmont, 2010.

- D. Steinberg and L. Jakobovists , Semantics: An Interdisciplinary Reader in Philosophy, Linguistics and Psychology , Bambridge University Press, 1971.

- T. Bartkowski , Assessment of attractiveness for recreation of multisensoric landscape, valorisation of surface vs. valorisation of lines , in Functioning and Evaluation of a Landscape, T.J. Chmielewski , A. Richling , and K.H. Wojciechowski , eds., Towarzystwo Wolnej Wszechnicy Polskiej, Lublin, 1992, pp. 113–113. ( in Polish).

- S. Bernat , Relations between sound, music and landscape , in: Perspective on the Regional Development in the Light of Landscape Research, M. Strzyż , ed., The Problems of Landscape Ecology, Kielce, 2005, pp. 289–295. ( in Polish).

- A. Kowalczyk , Patch-corrio-matrix model application to natural environment evaluation for recreational needs , A. Cieszewska ed., The Problems of Landscape Ecology, Warszawa, 2004, pp. 1–9. ( in Polish).

- K. Kożuchowski , Natural Values in Tourism and Recreation , Publishing House Krupisz, Poznań, 2005. (in Polish).

![Figure 1. Division of notices [after 21].](/cms/asset/fda0ed89-9f29-4638-9da4-291a56472877/nsme_a_1386756_f0001_b.gif)