Abstract

Objective

Well-being after spinal cord injury is affected by a range of factors, many of which are within the influence of rehabilitation services. Although improving well-being is a key aim of rehabilitation, the literature does not provide a clear path to service providers who seek to improve well-being. This study aimed to inform service design by identifying the experience and perspective of people with SCI about interventions targeting their well-being.

Method

The scoping review of qualitative literature used thematic analysis to identify and categorize themes related to service activities, valued aspects, limitations and perceived outcomes.

Results

Thirty-eight studies were selected, related to a range of service types. Most studies did not adopt a well-being conceptual framework to design and evaluate the services. People with SCI particularly valued being treated with dignity, positive expectations, increased autonomy and peer support. Improvements to well-being were reported, including many years post-SCI. However, people with SCI reported limited opportunities to engage in such services.

Conclusions

Rehabilitation services can improve well-being across the lifetime of people with SCI, but gaps in service provision are reported. The review identified valued aspects of services that may inform service design, including staff approach and positive expectations, having own skills and worth valued, peer support and interaction, autonomy in valued occupations, and long-term opportunities for gains.

Introduction

Maximizing well-being is a key focus of disability and rehabilitation services (Bertisch et al., Citation2015; Hammell, Citation2006; Pain et al., Citation1998; Whiteneck & Hall, Citation1992), at least in theory. According to the World Health Organization, the purpose of rehabilitation is to enable people “of all ages to maintain or return to their daily life activities, fulfil meaningful life roles and maximize their well-being” (World Health Organization, Citation2019) para. 1. Spinal cord injury (SCI) can negatively impact well-being (especially in the short to medium term), and is commonly thought to make life no longer worth living (an ableist assumption shared with many other disabilities) (Albrecht & Devlieger, Citation1999; Brickman et al., Citation1978; Peña-Guzmán & Reynolds, Citation2019). However, the impact of SCI on well-being is not straightforward. SCI can reduce well-being in a number of ways (Boakye et al., Citation2012; Dijkers, Citation1997; Murray et al., Citation2007), but many people with the injury experience post-traumatic growth (Bonanno et al., Citation2012; Byra, Citation2016; Griffiths & Kennedy, Citation2012; Kennedy et al., Citation2013; Pollard & Kennedy, Citation2007) and report that their lives are meaningful and satisfying (Albrecht & Devlieger, Citation1999; Bach & Tilton, Citation1994; Bonanno et al., Citation2012; Migliorini & Tonge, Citation2009).

The complex phenomenon of well-being appears to be influenced by a range of factors after SCI. Qualitative research has identified determinants that people with SCI perceive affecting their well-being (Bergmark et al., Citation2008; Clifton et al., Citation2018; Duggan et al., Citation2016; Geard et al., Citation2018; Hammell, Citation2007; Simpson et al., Citation2020). They report that their well-being is enhanced by the ability to engage in occupations, enjoy meaningful relationships, employ their strengths and values and take control of their daily life. These elements facilitate self-worth and self-continuity. They also report that body problems, a sense of loss and environmental barriers negatively impact their well-being. Making changes to these determinants of well-being is within the scope of rehabilitation and disability services (Simpson et al., Citation2020), and improving well-being should be a focus of service design and evaluation for people with SCI.

Well-being is defined poorly (if at all) in disability and rehabilitation research (Dijkers, Citation2005; Hill et al., Citation2010; Post, Citation2014; Simpson et al., Citation2020). A range of terms are used somewhat interchangeably with well-being in this body of literature (Svensson & Hallberg, Citation2011), including quality of life (Hill et al., Citation2010; Post, Citation2014; Tate et al., Citation2002), subjective well-being (Fuhrer, Citation2000), flourishing (Clifton et al., Citation2018), wellness (Carroll et al., Citation2020; Hall et al., Citation2021) and life satisfaction (Dunnum, Citation1990). Finding a clear and useful definition for these terms is also difficult. Broad definitions, such as ‘a life worth living’ (Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2006; Janning, Citation2013; Migliorini et al., Citation2013; Seligman, Citation2011), capture the multidimensional nature of well-being, but these definitions may be too vague to be a guide for service design and evaluation. Narrower conceptions such as ‘health-related quality of life’ may miss aspects of well-being that are unrelated to, or unaffected by, a health condition, particularly for people with long-term disability like SCI. The complexity of conceptualizing well-being is exacerbated by the debate about whether the good life consists of subjective well-being (positive emotions, life satisfaction) or psychological well-being (meaning, character,growth) (Henderson & Knight, Citation2012; Kashdan et al., Citation2008; Keyes et al., Citation2002; Ryan & Deci, Citation2001). Rehabilitation service design and evaluation may be best guided by frameworks that list a range of well-being elements. Post (Post, Citation2014) has evaluated broad conceptual frameworks that may be used in disability service design and research. The elements of well-being proposed by positive psychology (positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment) (Seligman, Citation2011) are also a useful contribution to our understanding of well-being. However, these frameworks have not yet been widely adopted in rehabilitation and disability research (Shogren, Citation2013).

The lack of clarity about well-being is reflected in the tools used to measure this phenomenon for people with disability. There has been a positive trend towards including an outcome measure of well-being or quality of life in rehabilitation intervention studies, usually as a secondary measure. But questions have been raised about the suitability of commonly used measures of well-being, which are often designed by researchers without disability, for the general population (Amundsen, Citation2005; Dale, Citation1995; Dijkers, Citation1999; Hammell, Citation2004; Mackenzie & Scully, Citation2007; Slevin et al., Citation1988) rather than for people with SCI. Such measures have been criticized for overlooking well-being elements that may be important to people with long-term impairments and for over-emphasizing activities such as walking that may not be important for the well-being of people with SCI (Leplege & Hunt, Citation1997; Michel et al., Citation2016; Tate et al., Citation2002; Whitehurst et al., Citation2014). Thus, quantitative studies that adopt such well-being measures may not adequately reflect the priorities and experience of people with SCI. Furthermore, quantitative intervention studies do not provide an in-depth understanding of how or why well-being was enhanced.

Because well-being is a broad phenomenon influenced by a range of factors, it is possible that most services for people with SCI can influence well-being in some way. However, a more explicit focus on well-being may maximize the impact of these services, particularly when accompanied by efforts to measure their effectiveness (Hammell, Citation2006, Citation2017; Pizzi & Richards, Citation2017; Simpson et al., Citation2020). Intentionally designing services to address well-being requires an in-depth understanding of this phenomenon. However, there is a lack of clarity about how to define, address and measure the well-being of people with SCI. Consequently, SCI service providers who seek further understanding in the literature face a confusing maze. An in-depth understanding about well-being of people with SCI should be informed by the voices of people living with this condition. Several qualitative studies have sought the perspective of people with SCI about rehabilitation services related to their well-being. Understanding how people with SCI experience these services, including valued aspects, limitations and perceived outcomes, may help inform service design and evaluation. This paper sought to examine the perspective of people with SCI on services that addressed their well-being and to map and synthesize the qualitative literature on the topic.

Aims

The larger aim of this paper is to give service providers insight into how to improve the delivery of their services by identifying the experience and perspective of people with SCI about interventions targeting their well-being. The specific aims were to i) examine the extent and nature of qualitative research related to well-being programs for people with SCI; ii) describe how well-being is conceptualized in these studies, and whether/how intentional design for well-being was used; iii) describe specific activities, timing and context of rehabilitation services related to well-being; and iv) explore how people with SCI perceive and experience these services. In collating this information from rich qualitative studies, the larger aim of this paper is to give service providers insight into how to improve the delivery of their services and maximize their participants’ well-being.

Method

We used a scoping review methodology, which is well-suited to exploring the scope of research activity (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Rumrill et al., Citation2010), particularly for an emerging body of research about a poorly defined construct, which this appeared to be. We used the five stages proposed by Arksey & O’Malley (Citation2005): 1) identifying the research question; 2) locating relevant studies; 3) selecting appropriate studies; 4) charting the data and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results.

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

The overall question guiding this scoping review was as follows: “What is known from the existing qualitative literature about well-being services for people with SCI?” Our specific focus on SCI was guided by the assumption that well-being issues would be unique and specific to this population, due to the (usually) sudden onset of significant impairment. We acknowledged the complexities in defining well-being and included studies that referred to well-being (or a related concept such as quality of life) regardless of definition. Because well-being is multidimensional, we were also interested in studies that addressed a specific element of well-being or a specific outcome that is known to promote well-being. ‘Rehabilitation service’ is a similarly hard concept to define. We were guided by the World Health Organization’s definition of rehabilitation as a “set of interventions needed when a person is experiencing or is likely to experience limitations in everyday functioning” aiming to enable “individuals of all ages to maintain or return to their daily life activities, fulfil meaningful life roles and maximize their well-being” (World Health Organization, Citation2019). Rehabilitation services were defined as any activities, services or programs that appeared to promote these rehabilitation aims.

Stage 2: Locating relevant studies

We conducted a database search of Medline, ADMED, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PsychARTICLES, PsychINFO, Embase and CINAHL. Search terms related to spinal cord injury were spinal cord injuries, spinal cord injur*, paraplegi*, tetraplegi*, and quadriplegi*. Search terms related to well-being were quality of life, personal satisfaction, wellbeing, well being, well-being, happiness, good life, wellness and flourish*. ‘Qualitative’ and ‘interview’ were also used as search terms to narrow the search to qualitative or mixed-methods studies, as our research question sought an in-depth perspective of people with SCI. Reference lists of included studies were hand searched to identify studies missed by the database search. Identifying these search terms was an iterative process, and we redefined search terms as early searches identified additional terms that were relevant.

Stage 3: Selecting appropriate studies

Studies needed to include people with SCI of any cause or level, and of any age, but could also include people with conditions other than SCI. Included studies needed to relate to well-being, with well-being (of any definition) being the aim of the service or research or linked to the reported outcomes. As we wanted to explore how rehabilitation can affect well-being, we included studies that reported mostly negative impacts on well-being. We included studies in which participants discussed a rehabilitation service (as defined above), including services provided outside of an inpatient rehabilitation setting or conducted by non-professionals. One area of contention was whether adapted sport should be considered a rehabilitation service: we included studies that involved entry-level adapted sports, but not elite sports. Included studies needed to have employed a qualitative methodology. Qualitative methods needed to provide an in-depth understanding of the perspective of people with SCI, so we excluded studies that only used closed-ended questionnaires or surveys. Mixed-methods studies were included if the qualitative component facilitated this in-depth understanding. We also included reviews of qualitative studies. We included studies published between 1995 and May 2021, assuming that research published more than 25 years ago would reflect a different service delivery context and that results of such studies would only be minimally useful to our research aims. We only included studies published in English, for pragmatic reasons.

The authors needed to include participant quotations as an ‘audit trail’ to support their findings and to ensure the voices of people with SCI were represented. This was the only indicator of methodological quality that was used as a basis for inclusion. Quality of included studies was further appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist (Skills, C.A. and Programme, Citation2018). This checklist was used to evaluate and report the methodological quality of the included studies, but was not used to determine inclusion or exclusion. We only appraised the qualitative component of mixed-methods studies and only appraised primary research using this checklist.

Study titles, abstracts and then full-text versions were screened for relevance, and we gradually excluded studies that were not relevant or did not meet the inclusion criteria. The titles of 829 original publications were screened, with 229 studies excluded at this stage. The abstracts of 600 studies were read, where the title suggested relevance or did not provide enough information. After 490 studies were excluded based on their abstract, 110 studies were read in full. Of these, 72 studies were excluded, including 8 studies that otherwise met the inclusion criteria but did not meet the quality criterion of including participant quotes. Other reasons for exclusion included study participants not receiving a common intervention or the study having an inadequate or unclear focus on well-being. A flow chart of study selection is shown in .

Stage 4 and 5: Charting the data, and collating and summarizing the results

We developed charting forms related to each research aim and extracted the following data: study location, methods and sample; conceptions of well-being; program type, timing, duration and context; specific program activities; and valued aspects, limitations and perceived outcomes of programs. Next, we used reflexive thematic analysis to identify themes, using the methods described by Braun & Clarke (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, Citation2012, Citation2014). We coded findings that appeared to relate to a similar category, using an iterative coding strategy. For example, we grouped findings about the characteristics of program staff and separately grouped findings about the involvement of peers with SCI. These categorized findings functioned as ‘topic summaries’ which were then analysed inductively and interpreted to identify patterns of shared meaning in the perspectives of the study participants (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). The first author (BS) conducted the analysis, with team discussions used for reflexivity and to provide additional perspectives to guide coding, interpretation and theme development.

Results

Research aim i): examine the extent and nature of qualitative research related to well-being programs for people with SCI

Study characteristics are described in . Of the 38 included studies, 28 used a solely qualitative methodology, one was a systematic review of qualitative studies, seven reported both qualitative and quantitative results of a mixed-methods study, and two reported only the qualitative results of a broader mixed-methods study. The quantitative component of mixed-methods studies mostly involved a single cohort pre-post design (n = 5), and only one mixed-methods study involved a randomized controlled trial.

Table I. Study characteristics

Four of the studies recruited people with other conditions, in addition to people with SCI. These other conditions appeared as all cause long-term physical disability. Eight studies exclusively recruited people with tetraplegia; the other studies had a mix of people with paraplegia and tetraplegia (n = 20), or did not report level of injury (n = 9). Mean time post-injury in the studies was less than one year (n = 1), 1–2 years (n = 3), 3–5 years (n = 5), 6–10 years (n = 7), 11–15 years (n = 5), more than 16 years (n = 3) or was not stated (n = 13). All the studies involved adults, and no paediatric studies were found. Three of the studies included interviews with family members and health professionals in addition to people with SCI. The majority of studies were conducted in USA (n = 14) and Canada (n = 9), with other studies conducted in Australia (n = 5), Ireland (n = 3), Sweden (n = 2), UK (n = 2), Italy (n = 1) and Switzerland (n = 1).

Quality appraisal findings are reported in the supplementary material. The most common methodological issues were methods (e.g., interview guide) not being made explicit, no discussion of data saturation, and a lack of reflection of how researcher biases may have influenced design, recruitment and analysis. Most studies did not report ethical, methodological or recruitment issues, which may have been because such issues did not arise.

Research aim ii): describe how well-being is conceptualized in these studies, and whether/how intentional design for well-being was used

The term ‘well-being’ was used in 16 of the included studies, but the most commonly used term was quality of life (n = 21). Other terms used that appeared to relate to well-being included life satisfaction (n = 5), social well-being (n = 5), physical well-being (n = 4), psychological well-being (n = 4), subjective well-being (n = 3), mental well-being (n = 2), emotional well-being (n = 2), flourishing (n = 2), health-related quality of life (n = 1), psychosocial well-being (n = 1) and overall well-being (n = 1). However, in the majority (n = 31) of studies, these terms were not defined. Some authors used multiple terms (e.g., ‘well-being’ and ‘quality of life’) and these mostly appeared to be used interchangeably.

Of the studies that defined well-being (or quality of life), four listed a broad range of well-being elements, relating to physical functioning, psychological/emotional resources and state, social functioning, independence and participation, and environmental accessibility (Ekelman et al., Citation2017; Hitzig et al., Citation2013; Maddick, Citation2011; Williams et al., Citation2014). One study defined quality of life as the gap between desired and actual achievements (Semerjian et al., Citation2005). Another defined quality of life using the World Health Organization’s broad definition of health (Cotner et al., Citation2018).

Some studies focused on a specific phenomenon they linked to well-being, including the following: occupations and meaningful activities (Ekelman et al., Citation2017; Folan et al., Citation2015; Luchauer & Shurtleff, Citation2015; Verdonck et al., Citation2018; Ward et al., Citation2007), physical activity (Ekelman et al., Citation2017; Taylor & McGruder, Citation1996), adaptive sports (Lape et al., Citation2018), leisure activities (Houlihan et al., Citation2003; Labbé et al., Citation2019; Taylor & McGruder, Citation1996), peer mentoring (Beauchamp et al., Citation2016; Chemtob et al., Citation2018), goal-setting ability and self-efficacy (Block et al., Citation2010; Folan et al., Citation2015; Wangdell et al., Citation2013), employment (Cotner et al., Citation2018; Ramakrishnan et al., Citation2016), computer/IT access (Folan et al., Citation2015; Mattar et al., Citation2015), coping (Brillhart & Johnson, Citation1997; Hutchinson et al., Citation2003; Zinman et al., Citation2014), choice and control (Labbé et al., Citation2019), autonomy (Nygren-Bonnier et al., Citation2018), social support (O’Dell et al., Citation2019; Veith et al., Citation2006), social participation (Tamplin et al., Citation2014), music (Tamplin et al., Citation2014), and use of environmental control systems (Verdonck et al., Citation2014, Citation2011).

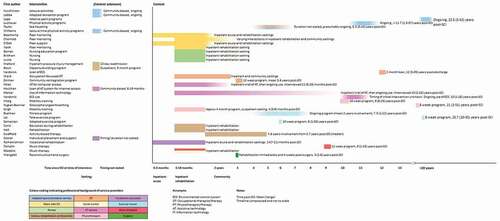

Research aim iii): describe specific activities, timing and context of rehabilitation services related to well-being

Activities

Service activities are described in , and the timing and context of services are shown in . A broad range of service types were studied, carried out by a range of disciplines. We categorized the services based on who delivered them: adaptive recreation and sport providers (n = 6), peers with SCI (n = 4), nurses (n = 4), occupational therapists (n = 4), an occupational therapist and social worker (n = 1), assistive technology services (n = 4), physiotherapists (n = 4), exercise trainers (n = 3), vocational consultants (n = 2), various rehabilitation professionals (n = 2), a music therapist (n = 1), a music therapist and social worker (n = 1), and a surgeon (n = 1). Most services were delivered by a single profession, although presumably some of these services were part of a broader multidisciplinary program. Two studies described a multidisciplinary service.

Table II. Service activities

Services were often only described in general or vague terms, although mixed-methods studies tended to include a more detailed description of specific intervention activities. Whilst a range of disciplines delivered the services, we have identified and categorized activities that were common to the services, including the following: structured education programs (e.g., workshops), facilitating engagement in occupations and activities (e.g., skills training, adapting activities, escorted outings, and group activities), facilitating access to assistive technology (e.g., exposure, prescription, loan, training, and modifications), psychological and emotional support (e.g., coaching, training, goal setting, goal pursuit, and support groups), formal and incidental peer support and mentoring, addressing body function (e.g., mobility training, breathing training, and electrical stimulation), liaison (e.g., integrating program into general rehabilitation, and referral to other organizations), nursing care and surgery.

Research aim iv): explore how people with SCI perceive and experience these services

Valued aspects, limitations and perceived outcomes of the services are described in .

Table III. Valued aspects, limitations and perceived outcomes

Valued aspects included positive expectations of service providers, which raised the expectations of people with SCI about what was possible: “She just kind of conveyed this feeling to me … that I was going to be able to do just whatever” (Ward et al., Citation2007) p.153. The personal characteristics of service providers were also important in facilitating a positive, supportive environment, and valued staff attributes included respect, recognizing dignity and equality, warmth and friendship. “she was so reassuring and she was so caring and so pleasant, and there to tell me, okay, I—I’m not alone” (Ramakrishnan et al., Citation2016) p.188. Peers with SCI were another source of positive expectations and hope: “ … opens your mind up to all the things you can do and the way that you can get around it” (Beauchamp et al., Citation2016) p.1980. Peer support (whether formal or incidental) was also valued for the connection, belonging and understanding brought about by interaction with people in a similar situation: “It’s a great way to have a bit of camaraderie and a feeling of group, a sense of being in a group or a community” (Tamplin et al., Citation2014) p.241. People with SCI valued long-term opportunities for continued gains and improvement (in a range of areas), even if these gains were seemingly small. They also wanted opportunities to challenge themselves and take risks, although the right level of challenge was important: experiencing too many difficulties was confronting and discouraging. Services that facilitated participation and autonomy in meaningful occupations were highly valued, including in both pre-injury and new occupations: “ … makes you feel good because it does feel the same as before [the accident]” (Tamplin et al., Citation2014) p.240. Learning new skills helped improve autonomy, and people with SCI wanted practical and applicable information that enhanced this learning. They also valued having their own problem-solving skills recognized and enhanced: an important way to gain autonomy in the long term. Their own efforts, character and determination were also crucial: “ … what helped me the most was my own will to be independent” (Bernet et al., Citation2019) p.6. Connections with others were important, and services were valued when they facilitated interaction with peers and provided opportunities to engage with significant others: “ … gives me an opportunity to do something together that we both like” (Hutchinson et al., Citation2003) p.152. People with SCI noted that the contribution of supportive family and friends in facilitating participation in valued activities and the support of others (e.g., transport to clinics) was often crucial for being able to participate in services.

There appeared to be an important balance between setting positive expectations and facilitating achievement early after injury, whilst not overwhelming the person during the acute stages post-SCI. People with SCI expressed varying perspectives about preferred timing of services, and flexibility in delivery appears important (although not always provided). Discharge home was a challenging milestone, and people with SCI valued services in preparation for, and soon after, discharge. Community-based services provided soon after discharge provided structure, routine, and an opportunity to maintain or continue gains made in an inpatient setting “I am feeling like I am accomplishing something throughout the day” (Ekelman et al., Citation2017) p.34. There did not appear to be a time that was too late to provide services, and gains were valued even many years post-SCI. However, opportunities to engage in services at this stage were rare. The physical environment of services was important to people with SCI. Opportunities to be in (or at least see) nature and the outdoors were highly valued: “you get excited about nature, clouds and the currents … ” (Taylor & McGruder, Citation1996) p.42. An unpleasant, inflexible, impersonal hospital environment had a negative impact on well-being in one study.

Overall, people with SCI reported few limitations of the services themselves, but a common theme was a lack of opportunity to participate in well-being-related services. Some of the services were provided only during the study period, and people with SCI often reported that they wished the services were longer or more available outside of a research context. Many people with SCI reported a lack of opportunity for accessible activities that promote well-being, particularly in a community setting or many years after injury. When suitable services were available, travel costs and logistics to access the services were often challenging or prohibitive. People with SCI were often made aware of community-based services by peers or through their own research, and there was a perceived lack of awareness of such opportunities amongst health professionals: “But it seems there really isn’t an awareness when you have to explain what you want and what you’re going to do and they just look at you like ‘really, you’re going to do what?’” (Taylor & McGruder, Citation1996) p43. Although a number of studies described services provided during inpatient rehabilitation, some people with SCI reported a lack of priority for such activities during their own early rehabilitation journey. Low expectations of health professionals and inflexible service delivery were limitations of inpatient rehabilitation reported by some study participants.

People with SCI reported a range of service outcomes, which related to both psychological and subjective well-being. Participants reported improved confidence and self-esteem, coping strategies, motivation, sense of identity, and normality. Improved mood, positive emotions, and sense of gratitude were also reported. “I feel much more alive. Enlivened and engaged with what I’m doing”(Tamplin et al., Citation2014) p.241. “It just helped to show us that there’s still a hell of a lot that we can be thankful for” (Zinman et al., Citation2014) p.9. A commonly reported outcome was increased hope, which participants felt was especially important to their well-being: “I think that was the hope that actually even helped me to get better” (Ramakrishnan et al., Citation2016) p.188. People with SCI reported improved independence and autonomy in performing occupations, which brought about greater control choice, privacy, and flexibility in their day-to-day lives. Greater autonomy enabled people with SCI to contribute to others and perform valued roles and reduced their sense of burden on others, frustration and ‘hassle’: “the more independent I will be and the more I can do for others … that’s gonna make me feel so much better with myself” (Semerjian et al., Citation2005) p.101. The subjective experience of performing occupations (of any kind) involved a sense of fun, enjoyment, flow, engagement, meaning, purpose, freedom, escape, diversion and relaxation: “You create some endorphins, and you’ve got your circulation working better … it’s really had an effect on my whole outlook.” (Lape et al., Citation2018) p.509. Increased autonomy in one occupation often had a flow-on effect, with participants often setting new goals, trying new activities, and having greater motivation to participate in other rehabilitation activities: “It gave me the motivation to stay with the rest of the therapy” (Hutchinson et al., Citation2003) p.152. People with SCI also reported improvements in relationships and a sense of belonging, as services enabled them to participate more in the community, provided new social contacts, and facilitated a sense of belonging. Perceived outcomes of a sub-set of the included studies are explored in more detail in a separate publication (Simpson et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

A contribution of this scoping review is the synthesis of qualitative research from a variety of disciplines, which readers may not have encountered otherwise. People with SCI reported well-being outcomes from a range of service types, reflecting the multidimensional nature of well-being and the fact that its determinants are relevant to a range of disciplines. Well-being may be addressed from different perspectives, and it is important for service providers to recognize their own potential to influence well-being, as well as the contribution of other team members. Improving well-being can and should be a common aim, which may require rehabilitation professionals to broaden their focus beyond the discipline ‘silos’ that may still exist in rehabilitation.

We argued earlier that a more explicit focus on well-being may maximize the impact of services on the lives of people with SCI, echoing calls from prominent rehabilitation researchers (Hammell, Citation2006, Citation2017; Pizzi & Richards, Citation2017). One of our aims was to explore how well-being was conceptualized in the included studies, and whether the services were intentionally designed to address well-being. Most authors did not define well-being (or related term). In several studies, improved well-being appeared to be a finding rather than an aim of the service. Four studies included a broad definition of well-being that appeared to be a helpful framework for service design and evaluation. However, we were not able to determine whether or how well-being frameworks were used to design the services because information about service design was rarely provided, possibly due to word restrictions. The question remains, does intentionally designing services to address well-being elements produce greater impacts on well-being? Or is well-being so broad that services can impact it without intentionally aiming to do so? Further research is needed to shed light on these questions, which our review seems to have highlighted. Such research may include evaluation of programs that deliberately aim to address well-being by targeting its determinants. A review of the quantitative literature would also be helpful, particularly in shedding light on the question of whether a more explicit focus on well-being produces greater well-being outcomes.

This scoping review has synthesized important insights from people with SCI about valued aspects of services. These insights may inform service design and evaluation. A key finding was the importance of the characteristics and approach of service providers, including respect for the autonomy and dignity of people with SCI. Services that facilitated autonomy and control were valued, and these influenced well-being in a number of ways. People valued having their own skills and strengths recognized and encouraged, such as problem-solving skills. These skills are important for self-care and self-management after SCI, and an important way people with SCI can manage the impact of their condition on well-being (Conti, Clari et al., Citation2020). Psychological strengths and resources are an important well-being determinant (Clifton et al., Citation2018; Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004; Simpson et al., Citation2020). Interestingly, we did not find any qualitative studies from the psychology literature. Such studies may provide valuable insights about how psychological strengths can be identified, recognized and nurtured to promote well-being. Recognition of the importance of the skills and behaviours of people with SCI is congruent with the literature about self-care and self-management

Another key theme was the importance of positive expectations. Service providers who promoted high expectations and facilitated hope influenced well-being by countering the low expectations that people may have initially held about the possibility of a good life. Hope was also important to people with SCI, and increased hope was a valued outcome of some services. Hope and positive expectations did not appear to relate to a potential cure for SCI (although some participants discussed physical activity as a way of taking advantage of a future cure). People found hope in a good life in the absence of a cure, and despite the presence of significant impairment. This finding is consistent with the social model of disability that environmental factors are a vital influence on well-being (Barnes, Citation2019; Hammell, Citation2007; Oliver & Sapey, Citation1999). However, well-being can also be influenced by body functions, and people with SCI reported important well-being outcomes when body problems such as pain and fatigue were addressed. They also reported many persistent environmental barriers that limited their ability to participate in well-being promoting activities and services. Spinal cord injury challenges simplistic distinctions between the medical and social models of disability, revealing how well-being is embodied. It is always a product of the complex interplay between bodily function and the social environments (Mackenzie & Scully, Citation2007; Siebers, Citation2008).

The importance of interaction with peers with SCI was another key theme, and this related to the theme of positive expectations. Being exposed to the life of a person with a similar injury raised expectations about what was possible. Peer interaction was also an important source of social contact, belonging and understanding. Several of the studies involved formal peer support services, and these services appear to strongly influence well-being, particularly soon after SCI when a person may be unsure about what life may hold. However, peer contact was also provided incidentally by many of the services and facilitating informal peer interaction may be an important way service providers can influence well-being. Although beyond the scope of this paper, this peer emphasis suggests spinal cord injury services should give more thought to the importance of coproduction in the design and delivery of programs (Alakeson et al., Citation2013; Ryan, Citation2012).

There appear to be limited opportunities for people with SCI to participate in services to improve well-being, particularly in the community or many years post-SCI. Rehabilitation services often end within several years of injury, with longer term follow-up often focusing on managing problems like pressure injury and replacing old equipment rather than improving well-being. Interestingly, the majority of studies in this review involved community-based services, with several provided to people more than 20 years post-SCI. These studies contributed valuable insights from people many years post-injury. However, it appeared that many of these services were provided for the purposes of research, rather than being available generally or in the long term. Several participants reported a lack of services available to them or that they wanted services to be available beyond the study period. Ideally, services for people with SCI would promote sustainable change and autonomy, so that they are not required long term. Presumably, most people with SCI would prefer to become independent of specialized services if possible, although ongoing physical problems such as pain, and the effects of ageing with SCI, may necessitate some long-term specialized input. But people with SCI did value services provided to them many years post-injury and reported well-being outcomes from such services. Some of these services involved learning a new skill, e.g., a breathing technique, and trialling new assistive technology. If similar services are not provided outside of a research context, people with SCI might be missing out on exposure to new techniques and technology, especially when they are no longer involved with a formal rehabilitation service. Several of the community-based services were ongoing, involving adapted sport/exercise and recreation. It was clear that many people with SCI required long-term and specialized services to engage in these activities, presumably due to their needs (e.g., access requirements) not being met by mainstream services. However, gaps in such services were also reported, with participants reporting lack of services in their area or limited program resources.

These gaps may reflect the significant funding and insurance limitations that constrain the provision of services to people with SCI. SCI service providers may need to be creative and resourceful in order to offer well-being services outside of a traditional rehabilitation context. Research on the feasibility and outcomes of such services may also expand our understanding of how well-being can be improved across the lifespan of people with SCI.

Limitations

The studies in this review predominantly included the voices of people with SCI from USA and Canada, and findings may most strongly reflect the intervention context in North America. We did not include studies published in languages other than English, so may be missing the perspective of people from non-English speaking countries, whose experiences of SCI, services and well-being may differ from those in this review. Some studies included people with a range of conditions, and we were not able to distinguish which findings specifically related to participants with SCI. However, services are not always limited to people with SCI, and further research on whether and how services can impact well-being of people with a range of conditions would be worthwhile. Our key finding about peer support would also be interesting to explore in the context of these broader services, where the concept of ‘peer’ may extend to people with different diagnoses and conditions.

Methodological issues in the included studies may have impacted our findings. Some studies did not report many negative experiences or outcomes, and the absence of interview guides meant that we were not always able to determine whether this information was sought. The background and position of researchers is a potential source of bias, and for many studies we were unable to determine if and how biases were identified and managed. There did not appear to be much (if any) contribution of people with lived experience of disability as co-researchers (Mellifont et al., Citation2019). The absence of this perspective may have been a source of bias in design and analysis.

Our own backgrounds and perspectives have influenced design and analysis. SC is an academic with spinal cord injury, who has researched factors that affect the flourishing of people with disabilities. MV and BS have an occupational therapy background, which contributed expertise about (and a bias towards) occupation-related findings. MV’s research is characterized by large-scale collaborations that cross disciplines and sectors and that privilege the voices of those typically marginalized within research. The distinguishing feature of this research is our intentional application of inclusive models and participatory methodologies to bring people who do not normally work together to solve complex problems through cross-sector collaboration and co-production.

Conclusion

This scoping review has identified qualitative studies from a broad range of disciplines, who seek to address well-being from a variety of perspectives. A strong conceptual framework of well-being is mostly lacking in this body of literature, despite calls for a more explicit focus on well-being in rehabilitation services. Despite this, people with SCI reported a range of well-being outcomes. Valued aspects of services included a positive and empowering approach of service providers, the opportunity to participate in and gain autonomy in valued occupations, and peer support and interaction. However, many people with SCI reported a lack of such services available to them, particularly after inpatient rehabilitation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.2 KB)Acknowledgments

This research is supported by a Research Training Program scholarship, at the University of Sydney.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bronwyn Simpson

Bronwyn Simpson is a PhD student and Associate Lecturer in the Discipline of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney. Associate Professor Michelle Villeneuve leads research on disability-inclusive community development at the Centre for Disability Research and Policy at The University of Sydney. Professor Shane Clifton is Honorary Associate, Centre For Disability Research And Policy, Faculty of Medicine, the University of Sydney. He lives with a spinal cord injury.

References

- Alakeson, V., Bunnin, A., & Miller, C. (2013). Coproduction of health and wellbeing outcomes: The new paradigm for effective health and social care. OPM, Editor.

- Albrecht, G. L., & Devlieger, P. J. (1999). The disability paradox: High quality of life against all odds. Social Science and Medicine, 48(8), 977–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00411-0

- Amundsen, R. (2005). Disability, ideology, and quality of life: A bias in biomedical ethics. In D. Wasserman, R. Wachbroit, & J. Bickenbach (Eds.), Quality of life and human difference: Genetic testing, health care, and disability (pp. 101–124). Cambridge University Press.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bach, J. R., & Tilton, M. (1994). Life satisfaction and well-being measures in ventilator assisted individuals with traumatic tetraplegia. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 75(6), 626–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9993(94)90183-X

- Barnes, C. (2019). Understanding the social model of disability: Past, present and future. In N. Watson & S. Vehmas (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies (pp. 14–31). Routledge.

- Beauchamp, M. R., Scarlett, L. J., Ruissen, G. R., Connelly, C. E., McBride, C. B., Casemore, S., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2016). Peer mentoring of adults with spinal cord injury: A transformational leadership perspective. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(19), 1884–1892. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1107773

- Bergmark, B. A., Winograd, C. H., & Koopman, C. (2008). Residence and quality of life determinants for adults with tetraplegia of traumatic spinal cord injury etiology. Spinal Cord, 46(10), 684–689. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.15

- Bernet, M., Sommerhalder, K., Mischke, C., Hahn, S., & Wyss, A. (2019). “Theory does not get you from bed to wheelchair”: A qualitative study on patients’ views of an education program in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Nursing Journal, 44(5), 247–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/rnj.0000000000000175

- Bertisch, H., Kalpakjian, C. Z., Kisala, P. A., & Tulsky, D. S. (2015). Measuring positive affect and well-being after spinal cord injury: Development and psychometric characteristics of the SCI-QOL Positive Affect and Well-being bank and short form. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 38(3), 356–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772315Y.0000000024

- Block, P., Skeels, S. E., Keys, C. B., & Rimmer, J. H. (2005). Shake-It-Up: Health promotion and capacity building for people with spinal cord injuries and related neurological disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(4), 185–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280400019583

- Block, P., Vanner, E. A., Keys, C. B., Rimmer, J. H., & Skeels, S. E. (2010). Project Shake-It-Up: Using health promotion, capacity building and a disability studies framework to increase self efficacy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(9), 741–754. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638280903295466

- Boakye, M., Leigh, B. C., & Skelly, A. C. (2012). Quality of life in persons with spinal cord injury: Comparisons with other populations. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine, 17(1 Suppl), 29–37.

- Bonanno, G., Kennedy, P., Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Lude, P., & Elfström, M. L. (2012). Trajectories of resilience, depression, and anxiety following spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 57(3), 236–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029256

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 9(1), 26152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (pp. 57–71). AP Books.

- Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(8), 917. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.8.917

- Brillhart, B., & Johnson, K. (1997). Motivation and the coping process of adults with disabilities: A qualitative study. Rehabilitation Nursing, 22(5), 249–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.1997.tb02111.x

- Byra, S. (2016). Posttraumatic growth in people with traumatic long-term spinal cord injury: Predictive role of basic hope and coping. Spinal Cord, 54(6), 478–482. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.177

- Carroll,N.W., Hall, A. G., Feldman, S., Thirumalai, M., Wade, J. T., and Rimmer, J. H., 2020). Enhancing transitions from rehabilitation patient to wellness participant for people with disabilities: An opportunity for hospital community benefit. Frontiers in Public Health 105,8doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00105.

- Chemtob, K., Caron, J. G., Fortier, M. S., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., Zelaya, W., & Sweet, S. N. (2018). Exploring the peer mentorship experiences of adults with spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 63(4), 542–552. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000228

- Clifton, S., Llewellyn, G., & Shakespeare, T. (2018). Quadriplegia, virtue theory, and flourishing: A qualitative study drawing on self-narratives. Disability and Society, 33(1), 20–38 doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1379951.

- Conti, A., Clari, M., Kangasniemi, M., Martin, B., Borraccino, A., & Campagna, S. (2020). What self-care behaviours are essential for people with spinal cord injury? A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Disability & Rehabilitation June 30 , 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1783703

- Conti, A., Dimonte, V., Rizzi, A., Clari, M., Mozzone, S., Garrino, L., Campagna, S., & Borraccino, A. (2020). Barriers and facilitators of education provided during rehabilitation of people with spinal cord injuries: A qualitative description. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0240600. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240600

- Cotner, B., Ottomanelli, L., O’Connor, D. R., Njoh, E. N., Barnett, S. D., & Miech, E. J. (2018). Quality of life outcomes for veterans with spinal cord injury receiving Individual Placement and Support (IPS). Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 24(4), 325–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/sci17-00046

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, I. S. (2006). A life worth living: Contributions to positive psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Dale, A. E. (1995). A research study exploring the patient’s view of quality of life using the case study method. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 22(6), 1128–1134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1995.tb03114.x

- Dijkers, M. (1997). Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A meta analysis of the effects of disablement components. Spinal Cord, 35(12), 829–840. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3100571

- Dijkers, M. (1999). Measuring quality of life: Methodological issues. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 78(3), 286–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-199905000-00022

- Dijkers, M. (2005). Quality of life of individuals with spinal cord injury: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and research findings. The Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 42(3 Supp 1), 87–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2004.08.0100

- Duggan, C., Wilson, C., DiPonio, L., Trumpower, B., & Meade, M. A. (2016). Resilience and happiness after spinal cord injury: A qualitative study. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 22(2), 99–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/sci2202-99

- Dunnum, L. (1990). Life satisfaction and spinal cord injury: The patient perspective. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 22(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01376517-199002000-00010

- Ekelman, B., Allison, D. L., Duvnjak, D., DiMarino, D. R., Jodzio, J., and Iannarelli, P. V. (2017). A wellness program for men with spinal cord injury: Participation and meaning. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 37(1), 30–39doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449216672170.

- Folan, A., Barclay, L., Cooper, C., & Robinson, M. (2015). Exploring the experience of clients with tetraplegia utilizing assistive technology for computer access. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 10(1), 46–52doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2013.836686.

- Fuhrer, M. J. (2000). Subjectifying quality of life as a medical rehabilitation outcome. Disability and Rehabilitation, 22(11), 481–489. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/096382800413961

- Geard, A., Kirkevold, M., Løvstad, M., & Schanke, A.-K. (2018). Exploring narratives of resilience among seven males living with spinal cord injury: A qualitative study. BMC Psychology, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-017-0211-2

- Griffiths, H. C., & Kennedy, P. (2012). Continuing with life as normal: Positive psychological outcomes following spinal cord injury. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 18(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/sci1803-241

- Hall, A. G., Karabukayeva, A., Rainey, C., Kelly, R. J., Patterson, J., Wade, J., & Feldman, S. S. (2021). Perspectives on life following a traumatic spinal cord injury. Disability and Health Journal, 1–7doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101067.

- Hammell, K. W. (2004). Exploring quality of life following high spinal cord injury: A review and critique. Spinal Cord, 42(9), 491–502. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101636

- Hammell, K. W. (2006). Perspectives on disability and rehabilitation: Contesting assumptions, challenging practice. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Hammell, K. W. (2007). Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord, 45(2), 124–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101992

- Hammell, K. W. (2017). Opportunities for well-being: The right to occupational engagement. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84(4–5), 209–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417417734831

- Henderson, L. W., & Knight, T. (2012). Integrating the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives to more comprehensively understand wellbeing and pathways to wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 196–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2i3.3

- Hill, M. R., Noonan, V. K., Sakakibara, B. M., & Miller, W. C. (2010). Quality of life instruments and definitions in individuals with spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord, 48(6), 438–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.164

- Hitzig, S., Craven, B., Panjwani, A., Kapadia, N., Giangregorio, L., Richards, K., Masani, K., & Popovic, M. (2013). Randomized trial of functional electrical stimulation therapy for walking in incomplete spinal cord injury: Effects on quality of life and community participation. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 19(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/sci1904-245

- Houlihan, B. V., Drainoni, M.-L., Warner, G., Nesathurai, S., Wierbicky, J., & Williams, S. (2003). The impact of Internet access for people with spinal cord injuries: A descriptive analysis of a pilot study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(8), 422–431. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0963828031000071750

- Hutchinson, S. L., Loy, D. P., Kleiber, D. A., & Dattilo, J. (2003). Leisure as a coping resource: Variations in coping with traumatic injury and illness. Leisure Sciences, 25(2–3), 143–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400306566

- Janning, F. (2013). Who lives a life worth living? Philosophical Papers and Reviews, 4(1), 8–16 doi:https://doi.org/10.5897/PPR2013.0097.

- Johansson, K. M., Nygren-Bonnier, M., Klefbeck, B., & Schalling, E. (2011). Effects of glossopharyngeal breathing on voice in cervical spinal cord injuries. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 18(9), 501–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2011.18.9.501

- Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 219–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802303044

- Kennedy, P., Lude, P., Elfström, M., & Cox, A. (2013). Perceptions of gain following spinal cord injury: A qualitative analysis. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 19(3), 202–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/sci1903-202

- Keyes, C. L., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007–1022. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022–3514.82.6.1007

- Labbé, D., Miller, W. C., & Ng, R. (2019). Participating more, participating better: Health benefits of adaptive leisure for people with disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 12(2), 287–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.11.007

- Lai, B., Rimmer, J., Barstow, B., Jovanov, E., & Bickel, C. S. (2016). Teleexercise for persons with spinal cord injury: A mixed-methods feasibility case series. JMIR Rehabilitation And Assistive Technologies, 3(2), e8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/rehab.5524

- Lape, E. C., Katz, J. N., Losina, E., Kerman, H. M., Gedman, M. A., & Blauwet, C. A. (2018). Participant-reported benefits of involvement in an adaptive sports program: A qualitative study. PM and R, 10(5), 507–515. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.10.008

- Leplege, A., & Hunt, S. (1997). The problem of quality of life in medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(1), 47–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03550010061041

- Luchauer, B., & Shurtleff, T. (2015). Meaningful components of exercise and active recreation for spinal cord injuries. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 35(4), 232–238doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449215601069.

- Lucke, K. T. (1997). Knowledge acquisition and decision-making: Spinal cord injured individuals’ perceptions of caring during rehabilitation. SCI Nursing, 14(3), 87–95 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9355615/.

- Mackenzie, C., & Scully, J. L. (2007). Moral imagination, disability and embodiment. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 24(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5930.2007.00388.x

- Maddick, R. (2011). ‘Naming the unnameable and communicating the unknowable’: Reflections on a combined music therapy/social work program. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2011.03.002

- Manns, P. J., & Chad, K. E. (2001). Components of quality of life for persons with a quadriplegic and paraplegic spinal cord injury. Qualitative Health Research, 11(6), 795–811. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/104973201129119541

- Mattar, A. A. G., Hitzig, S. L., & McGillivray, C. F. (2015). A qualitative study on the use of personal information technology by persons with spinal cord injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(15), 1362–1371. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.963708

- Mellifont, D., Smith-Merry, J., Dickinson, H., Llewellyn, G., Clifton, S., Ragen, J., Raffaele, M., & Williamson, P. (2019). The ableism elephant in the academy: A study examining academia as informed by Australian scholars with lived experience. Disability & Society, 34(7–8), 1180–1199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1602510

- Michel, Y. A., Engel, L., Rand-Hendriksen, K., Augestad, L. A., & Whitehurst, D. G. (2016). “When I saw walking I just kind of took it as wheeling”: Interpretations of mobility-related items in generic, preference-based health state instruments in the context of spinal cord injury. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14(1 1–11). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0565-9

- Migliorini, C., Callaway, L., & New, P. (2013). Preliminary investigation into subjective well-being, mental health, resilience, and spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 36(6), 660–665. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000100

- Migliorini, C., & Tonge, B. (2009). Reflecting on subjective well-being and spinal cord injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 41(6), 445–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0358

- Murray, R., Asghari, A., Egorov, D. D., Rutkowski, S. B., Siddall, P. J., Soden, R. J., & Ruff, R. (2007). Impact of spinal cord injury on self-perceived pre- and postmorbid cognitive, emotional and physical functioning. Spinal Cord, 45(6), 429–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102022

- Noreau, L., & Shephard, R. (1995). Spinal cord injury, exercise and quality of life. Sports Medicine (Auckland), 20(4), 226–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199520040-00003

- Nygren-Bonnier, M., Wahman, K., Lindholm, P., Markström, A., Westgren, N., & Klefbeck, B. (2009). Glossopharyngeal pistoning for lung insufflation in patients with cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 47(5), 418–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.138

- Nygren-Bonnier, M., Werner, J., Biguet, G., & Johansson, S. (2018). ‘Instead of popping pills, perhaps you should add frog breathing’: Experiences of glossopharyngeal insufflation/breathing for people with cervical spinal cord injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(14), 1639–1645. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1304583

- O’Dell, L., Earle, S., Rixon, A., & Davies, A. (2019). Role of peer support for people with a spinal cord injury. Nursing Standard, 34(4), 69–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e10869

- Oliver, M., & Sapey, B. (1999). Social work with disabled people. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Pain, K., Dunn, M., Anderson, G., Darrah, J., & Kratochvil, M. (1998). Quality of life: What does it mean in rehabilitation? Journal of Rehabilitation, 64(2), 5–11 https://www.proquest.com/openview/df998c91d07dd3ce99704aac0cb2b237/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=37110.

- Peña-Guzmán, D. M., & Reynolds, J. M. (2019). The harm of ableism: Medical error and epistemic injustice. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 29(3), 205–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.2019.0023

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

- Pizzi, M. A., & Richards, L. G. (2017). Promoting health, well-being, and quality of life in occupational therapy: A commitment to a paradigm shift for the next 100 years. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(4), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.028456

- Pollard, C., & Kennedy, P. (2007). A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post-traumatic psychological growth following spinal cord injury: A 10-year review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12(3), 347–362. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/135910707X197046

- Post, M. W. (2014). Definitions of quality of life: What has happened and how to move on. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 20(3), 167–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/sci2003-167

- Ramakrishnan, K., Johnston, D., Garth, B., Murphy, G., Middleton, J., & Cameron, I. (2016). Early Access to Vocational Rehabilitation for Inpatients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Qualitative Study of Patients‘ Perceptions. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 22(3), 183–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/sci2203-183

- Rumrill, P. D., Fitzgerald, S. M., & Merchant, W. R. (2010). Using scoping literature reviews as a means of understanding and interpreting existing literature. Work, 35(3), 399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2010-0998

- Ryan, B. (2012). Co‐production: Option or obligation? Australian Journal of Public Administration, 71(3), 314–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467–8500.2012.00780.x

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Semerjian, T. Z., Montague, S., Dominguez, J., Davidian, A., & De Leon, R. (2005). Enhancement of quality of life and body satisfaction through the use of adapted exercise devices for individuals with spinal cord injuries. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 11(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/BXE2-MTKU-YL15-429A

- Shogren, K. A. (2013). Positive psychology and disability: A historical analysis. In M. Wehmeyer (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology and disability (Oxford University Press) (pp. 19–33).

- Siebers, T. (2008). Disability theory. University of Michigan Press.

- Simpson, B., Villeneuve, M., & Clifton, S. (2020). The experience and perspective of people with spinal cord injury about well-being interventions: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1864668

- Singh, H., Sam, J., Verrier, M. C., Flett, H. M., Craven, B. C., & Musselman, K. E. (2018). Life after personalized adaptive locomotor training: A qualitative follow-up study. Spinal Cord Series and Cases, 4(6), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0037-z

- Singh, H., Shah, M., Flett, H. M., Craven, B. C., Verrier, M. C., & Musselman, K. E. (2018). Perspectives of individuals with sub-acute spinal cord injury after personalized adapted locomotor training. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(7), 820–828. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1277395

- Skills, C.A. and Programme. (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf

- Slevin, M. L., Plant, H., Lynch, D., Drinkwater, J., & Gregory, W. M. (1988). Who should measure quality of life, the doctor or the patient? British Journal of Cancer, 57(1), 109–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1988.20

- Svensson, O., & Hallberg, L.-M. (2011). Hunting for health, well-being, and quality of life. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 6(2), 7137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v6i2.7137

- Swaffield, E., Cheung, L., Khalili, A., Lund, E., Boileau, M., Chechlacz, D., Musselman, K. E., & Gauthier, C. (2021). Perspectives of people living with a spinal cord injury on activity-based therapy. Disability & Rehabilitation, 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1878293

- Tamplin, J., Baker, F., Grocke, D., & Berlowitz, D. (2014). Thematic analysis of the experience of group music therapy for people with chronic quadriplegia. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 20(3), 236–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1310/sci2003-236

- Tate, D., Kalpakjian, C., & Forchheimer, M. (2002). Quality of life issues in individuals with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 83(12 Supp 2), S18–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2002.36835

- Taylor, L. P., & McGruder, J. E. (1996). The meaning of sea kayaking for persons with spinal cord injuries. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 50(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.50.1.39

- Veith, E. M., Sherman, J. E., Pellino, T. A., & Yasui, N. Y. (2006). Qualitative analysis of the peer-mentoring relationship among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 51(4), 289–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.51.4.289

- Verdonck, M., Chard, G., & Nolan, M. (2011). Electronic aids to daily living: Be able to do what you want. Disability & Rehabilitation Assistive Technology, 6(3), 268–281. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2010.525291

- Verdonck, M., Nolan, M., & Chard, G. (2018). Taking back a little of what you have lost: The meaning of using an Environmental Control System (ECS) for people with high cervical spinal cord injury. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 13(8), 785–790doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2017.1378392.

- Verdonck, M., Steggles, E., Nolan, M., & Chard, G. (2014). Experiences of using an Environmental Control System (ECS) for persons with high cervical spinal cord injury: The interplay between hassle and engagement. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 9(1), 70–78doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2013.823572.

- Wangdell, J., Carlsson, G., & Friden, J. (2013). Enhanced Independence: Experiences after regaining grip function in people with tetraplegia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(23), 1968–1974. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.768709

- Ward, K., Mitchell, J., & Price, P. (2007). Occupation-based practice and its relationship to social and occupational participation in adults with spinal cord injury. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 27(4), 149–156doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2F153944920702700405.

- Wellard, S., & Rushton, C. (2002). Influences of spatial practices on pressure ulcer management in the context of spinal cord injury. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 8(4), 221–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172X.2002.00367.x

- Whitehurst, D. G. T., Suryaprakash, N., Engel, L., Mittmann, N., Noonan, V. K., Dvorak, M. F., & Bryan, S. (2014). Perceptions of individuals living with spinal cord injury toward preference-based quality of life instruments: A qualitative exploration. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12(1), 50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-50

- Whiteneck, G., & Hall, K. M. (1992). Outcome evaluation and spinal cord injury. Neurorehabilitation, 2(4), 31–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-1992-2406

- Wilcock, A. A. (2006). An occupational perspective of health. SLACK Incorporated.

- Williams, T. L., Smith, B., & Papathomas, A. (2014). The barriers, benefits and facilitators of leisure time physical activity among people with spinal cord injury: A meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Health Psychology Review, 8(4), 404–425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.898406

- World Health Organization. (2006). Constitution of the World Health Organization- Basic Documents https://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Rehabilitation. Retrievedfrom https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation

- Zinman, A., Digout, N., Bain, P., Haycock, S., Hébert, D., & Hitzig, S. L. (2014). Evaluation of a community reintegration outpatient program service for community-dwelling persons with spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Research and Practice, Epub 2014 Dec 9, 989025. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/989025