ABSTRACT

The purpose of this descriptive phenomenological study was to explore the lived experience and meaning of resilience of individuals in the setting of chronic illness who reside in low-resource communities of the Mississippi Delta, USA. Descriptive phenomenology and Polk’s resilience theory were utilized that focused on the individual’s lifeworld and the meaning of resilience. The descriptive phenomenological psychological by reduction method (DPPRM) was used for the analysis and further linked to specific aspects of resilience and Polk’s resilience theory operationalized patterns. Findings revealed six themes of the lived experience of the participants that make up the eidetic structure and are linked to multidimensional aspects of resilience to create meaning. Fostering increased resilient pattern development has the potential to improve health outcomes, well-being, and quality of life across the spectrum

Introduction

Strong links can be made between chronic illness, low-resource communities, and poor health outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, Citation2019, April 19; Noonan et al., Citation2016). Chronic illness is linked to repeated stress that threatens the health, wellbeing, and future welfare of the individual affected (Braveman & Gottlieb, Citation2014; CDC, Citation2019, April 19, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Kim et al. (Citation2019) identifies that geographical areas of high chronic illness occurrence, specifically cardiovascular disease among African American residents, have been understudied. One such area is the Mississippi Delta within the USA that has been identified that its residents rank the lowest in overall health indicators and highest rates of chronic illness (Mississippi State Department of Health, Citation2016). Specifically, within the Mississippi Delta River Region (MDRR) Tallahatchie County, low-resource communities are highly correlated with poor health outcomes (Gennuso et al., Citation2016; Noonan et al., Citation2016). One important area of research includes the phenomenon of resilience in the setting of chronic illness and health outcomes.

Cal et al. (Citation2015) conducted a systematic review and assert that resilient individuals demonstrate inverse relations between resilience scores and depression, anxiety, incapacitation, and somatization. Because resilience is so strongly linked to a better illness trajectory preventing poor health outcomes, building resilience in individuals who live in low-resource communities can help to overcome crisis and work to strengthen endurance and positive adaption during chronic illness (Kim et al, Citation2018; Robinson et al, Citation2019; Sturmberg et al., Citation2019). Historical perspectives on resilience research and theoretical ideas have focused on building blocks of resilience that include self-efficacy, coping, ego resiliency, self-determination, and hope (Scoloveno, Citation2016). Concept analysis identifies that defining attributes of resilience include a combination of biological, internal personality, and external factors that all intertwine together (Garcia Dia et al., Citation2013; Niitsu et al., Citation2017; Scoloveno, Citation2016).

Bolton et al. (Citation2016) conducted a meta synthesis that found protective resilient factors of external connection are found in the majority of studies drawn from longitudinal, psychometric, and cross-sectional literature. Psychometric protective factors reveal positive perceptions of self, spiritual and religiosity influences, acceptance of self and life, independence, internal locus of control, personal competence, structured style and sense of mastery, and a planned future or orientation as protective in earlier life stages (Bolton et al., Citation2016).

Phenomenological studies have been done in various populations resulting in the identification of poor resilient traits as well as many protective factors (Hassani et al., Citation2017; Kristjansdottir et al., Citation2018; Qiao et al., Citation2019; Rezaei et al., Citation2018; Van Wormer et al., Citation2011). Risk factors for poor resilience include lower capacities to cope with the stress and challenges that often accompany chronic illness due to social and economic status, affective losses, and emotional burdens (Cal et al., Citation2015; Gennuso et al., Citation2016; Kim et al, Citation2019; Noonan et al., Citation2016). Decreased self-esteem and emotional self-regulation, poor family dynamics, and difficult social relationships increase risk factors for poor health, physical disease, and premature mortality (CDC, Citation2020; Cal et al., Citation2015; Kim et al, Citation2019; Niitsu et al., Citation2017; Scoloveno, Citation2016). Additional factors include stress responses, limits or non-adherence to medical treatments or therapies, affective losses, and emotional burdens leading to poor resilience, higher psychopathology rates, and physical deterioration (Cal et al., Citation2015; Jackson et al., Citation2018; Niitsu et al., Citation2017). In order to understand the individual’s perception and response to the chronic illness that leads to poor health outcomes, detailed research is warranted (Kim et al., Citation2019).

In the midst of chronic illness and poverty, little is known about specific individual risk factors for developing poor resilient states that lead to poor health outcomes and protective resilient factors in the Mississippi Delta River Region (MDRR) Tallahatchie County population. Because the concept of resilience changes based on the context of the situation, this research aims to create a new basis of knowledge in which to identify resilient protective factors associated with building and maintaining resilience, and to identify individuals with maladaptive coping techniques who are at highest risk for poor resilience (Bolton et al., Citation2016; Cal et al., Citation2015; Garcia Dia et al., Citation2013). Lastly, discovering the intricacies of the lived experience as it pertains to resilience is especially important for vulnerable residents to elucidate its meaning and application within the community.

Methods

Design: descriptive phenomenology and Polk’s resilience nursing theory

There were two main parts to this study. The first part was based on descriptive phenomenology because it served as the basis of the life world experience of the individual. Husserl (Citation2012) claims that the individual’s lifeworld is central to understanding lived experiences, and forms the ontological and epistemological foundations for those understandings. Intentionality of consciousness of the individual is directed to a meaningful experience of their life world. According to Husserl (Citation2012), intentionality of consciousness means to understand something as something or being conscious of something (Christensen et al., Citation2017), that mental phenomenon is directed towards outward objects (Giorgi, Citation2009), and that temporal experiences include dual intentionality of the self in the past, present, and/or future (Husserl,Citation1962). The complexity of the phenomenon being studied in combination with factors that affect the health of the population created a need for research that looked at the individual’s lifeworld.

The second part of the study linked the individuals lifeworld to the phenomenon of resilience to create meaning. This part of the study explores building blocks of resilience and conceptual meanings of resilience: defining attributes, antecedents, and consequences, protective factors of resilience and low resilience risk factors. Polk’s Resilience Theory is based in part from Margaret Newman’s Theory of Health as Expanding Consciousness, and Martha Rogers’ Science of Unitary Human Beings theories and seminal psychological works of resilience that served as the link to nursing. Polk’s middle range nursing theory further supported the understanding of the meaning of resilience as a phenomenon in specific patterns that include areas of dispositional, relational, philosophical, and situational (Polk, Citation1997). Kim et al. (Citation2018) identified that Polk’s Resilience Theory is ideal to explain the complexity of resilience in the setting of chronic disease. Polk’s operational definitions categorize and explore findings on a deeper phenomenological level, and serve to consolidate the intricate details reported by individuals about their lived experience of chronic illness. describes the operational definitions outlined by Polk used in this study.

Table I. Polk’s resilient operational definitions.

depicts the patterns of resilience operationalized by Polk (Citation2000)

Sampling

Purposive sampling augmented with snowball sampling was used to recruit study participants who met inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: men and women between the ages of 18 and 80 with a chronic illness diagnosis; those of African American descent; and those who live in the Mississippi Delta River Region (MDRR) Tallahatchie County within low-resource communities. Participants had to understand and speak English in order to describe their experience.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Endicott College Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the protection of human subjects (approval no. 1709805-2). Ethical protection included procedures to maintain the study participant’s anonymity and confidentiality through informed consent, and to ensure data protection, safety, and security. At the time of the interview, the researcher reviewed the purpose of the study, the informed consent document, and obtained verbal consent prior to proceeding with the interview.

Data collection

Research was conducted by a doctoral student at Endicott College as the primary researcher who conducted data collection using a semi-structured interview with open-ended questions over Zoom technology for each participant for 45–60 minutes to provide rich insight into the participant’s lifeworld (Stenfors et al., Citation2020). Recruitment steps included (a) sending the purpose of the study, consent information, and the interview instructions to the field director at the Partners in Development, INC clinic. After identifying study participants that met the inclusion criteria and verbal consent was given, the field director scheduled a virtual Partners in Development, Inc., clinic interview between the researcher and the study participant. All virtual visits took place through Zoom technology with the Endicott College Zoom account. The field director escorted the participant into a private room for the interview. Only computers owned by Partners in Development, Inc., were used for Zoom audio/video interviews. The privacy measure of using a waiting room was set. The primary researcher’s password-protected iPhone was used to record phone interviews in addition to Zoom for virtual Partners in Development, INC clinic interviews, the field director was instructed to complete the following measures to protect privacy: shut the door to the room; disable cookies on the computer; and close all browsers. The interview proceeded. Once the virtual interview was complete, the field director ensured the Zoom meeting had terminated and the study participant logged out of the computer. Questions focused on viewpoints and experiences related to chronic illness, perceived support systems, coping strategies, and reflection of the past, present, and future. Prompts were used to illicit information. The interviews were transcribed verbatim by the primary researcher or a bonded and insured transcriptionist using a standardized transcription protocol in order to transform the raw data into a description of the psychological structure of the experience (Tokwe & Naidoo, Citation2020).

Data analysis

For this study purpose, the Descriptive phenomenological psychological by reduction method (DPPRM) outlined by Giorgi et al. (Citation2017) was chosen that seeks to understand the subjects experience through a method of elucidation aimed towards explicating the meaning from the whole structure, developing a fuller meaning, and applying it in a general manner and structure towards usefulness (Giorgi et al., Citation2017). The DPPRM steps include reading transcripts in order to grasp a basic sense of the whole situated description. Next, an attitude of scientific phenomenological reduction is essential to reach what Husserl (Citation2012) refers to attaining epoche. Epoche refers to a process of bracketing of past knowledge, theoretical or empirical works to reach the true essence of the phenomenon (Giorgi, Citation2009). Parts of the transcription are identified to reveal psychological meaning units that highlight psychological lived meanings and intentionality (Giorgi, Citation2009; Husserl, Citation2012), and serve as the basis of a psychological structure of the experience to make interconnections of patterns within the experience to create a moments structure (Husserl, Citation1962). Once the moments structure is created, it is further delineated by reductions that included “eidetic” in which objects were reduced to its essence, and an “eidetic structure” in which the invariant meaning of a phenomenon leads to its essence (Giorgi, Citation2009). After the eidetic structure and essence was formulated, specific areas of resilience were identified and finally linked to Polk’s operationalized patterns of resilience (Citation2000) to develop meaning (Giorgi et al., Citation2017; Polk,Citation1997; Polk, Citation2000; Sundler et al., Citation2019).

Evaluation and trustworthiness

Lincoln and Guba’s (Citation1985) framework of quality criteria of trustworthiness of inquiries served to guide this study's reliability and validity through continual analysis and devotion to reviewing the interview questions for clarity with an aim to obtain detailed, thick, and robust responses (Amankwaa, Citation2016). A process of reflection of transcripts with personal notes and thoughts to a committee for review and analysis during the interview process, and throughout the analysis of the raw data to delineate it into psychological meaning units occurred. Guidance was sought in order to transform the study participant’s expressions into expressions that highlight psychological lived meanings and intentionality to render implicit factors explicit as outlined by Giorgi et al. (Citation2017). Reflexivity was used to extend the confidence of the study results by identifying the researchers' own view of conceptual lens, explicit and implicit assumptions, preconceptions and values, and how these affected the research decisions during all phases of the study (Korstjens & Moser, Citation2018). Additionally, transferability was demonstrated by describing the context in which behaviour and experiences took place in order to create meaning (Korstjens & Moser, Citation2018).

Results

Participants

A purposeful sample of 8 was used to explore the lived experience and meaning of resilience in the setting of chronic illness. The age of the participants ranged from 33 to 64 years of age. Most of the participants were female. Only one male was included in the study sample. The demographic data describing the participants is depicted in .

Table II. Participant demographics.

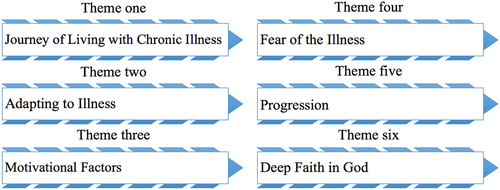

Analysis of the recordings and transcribed narratives provided by the eight study participants revealed the phenomenological eidetic structure of the lived experience in the setting of chronic illness and low-resourced communities in the following structural themes: 1) The journey of living with chronic illness; 2) Adapting to illness; 3) Motivational factors; 4) Fear of the illness; 5) Progression; and, 6) Deep faith in God. Themes are depicted in .

Figure 1. Eidetic structure of the lived experience and meaning of resilience in the setting of chronic illness and low-resourced communities.

depicts the eidetic structure of the lived experience and the meaning of resilience in the setting of chronic illness and low-resourced communities

Eidetic structure themes

As directed by Giorgi’s (Citation2017) DPPRM method, the eidetic structure is described in the areas of theme, subtheme, and transformed meaning that correlate to the study participant narrative examples and served as the basis for forming part 1 of the eidetic structure to explore the lived experience. depicts partial examples of the total thematic analysis from the original dissertation.

Table III. Theme, subtheme, transformed meaning, and participant narratives.

depicts the theme, subtheme, transformed meaning, and participant narratives.

The essence of the lived experience and meaning of resilience in the setting of chronic illness and low-resource communities

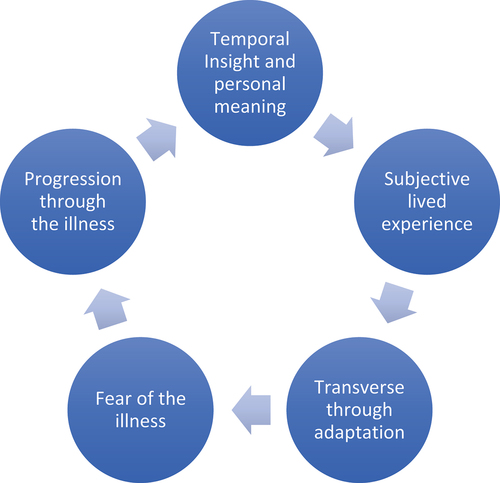

According to Giorgi (Citation2009) eidetic reduction is a process in which an object is reduced to its essence to explain the lived experience from a psychological phenomenological perspective. The six themes of the eidetic structure support that through the subjective lived experience of chronic illness, individual’s transverse through the process of adaptation, which is derived from a combination of factors. The outcome seeks to reach temporal insight towards personal meaning and understanding based on subjective chronic illness experiences described as journeys that were unique to them. shows the essence of the experience.

Figure 2. Essence of the lived experience and meaning of resilience in the setting of chronic illness and low-resourced communities.

depicts the essence of the lived experience and meaning of resilience in the setting of chronic illness and low-resourced communities

Part 2: eidetic structure related to the phenomenon of resilience

Building blocks of resilience

An important aspect of this study was to create a link between the eidetic structure and the phenomenon of resilience to create meaning. Significant components of resilience including self-efficacy, coping, ego resiliency, self-determination, and hope are discussed below.

Self-efficacy

Definitions

Self-efficacy is the ability to perform a specific task in a particular situation in a confident manner. This is derived from perceptions and expectations of the individual to determine behaviours and actions towards coping mechanisms that are directed at a desired outcome or attainment of an outcome by setting goals. Bandura (Citation1977) believes resilience arises out of beliefs in one’s own self-efficacy, which is the ability to deal with change by using social problem solving skills and is the foundation for coping.

This study identified that building foundations of knowledge used early in diagnosis elucidated the meaning of illness. The significance of this knowledge laid the groundwork for abating fear of diagnosis. External partnerships with health care providers, strong family and community structural support systems, and spiritualism were critical components in achieving self-efficacy virtues. Ongoing realistic appraisal of stress associated with chronic illness required repeating this same process throughout the illness towards resolution. Perceptions and developing senses and beliefs of self-advocacy, self-assurance, and responsibility in one’s capability to manage chronic illness were portrayed. Positive perceptions of the self gave the participant the ability to possess a thankful attitude rather than one of self-pity. Finally, study participant self reflection of the past clarified temporal present and future chronic illness meaning to the participant moving forward and not backward. As such, individuals were able to achieve self-efficacy, endurance, and perseverance despite facing difficulty with chronic illness.

Coping

Definitions

Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress and Coping Theory (Citation1984) asserts that coping is described as the effort made by an individual to manage excessive internal or external stressors by using cognitive and behavioural methods. Research studies detail that coping appraisal functions as a protective factor, which allows the individual to mitigate the effects of psychological and social risk factors that can include adverse environmental conditions such as poverty (Garmezy, Citation1993; Rutter, Citation1990).

This study found personalized coping strategies were utilized by the participants throughout the process of adaptation and energy transformation. Techniques were mostly derived from experiencing and learning about chronic illness. External support enhanced personal coping mechanisms. Incentives for coping strategies were often based on duty, respon-sibility, and obligations that the participant had to others. Reflection on coping mechanisms was important in offering others with a similar diagnosis advice based on their personal experience.

Ego-resiliency

Definition

The capacity to adapt to constantly changing circumstances that is associated with flexibility, energy, assertiveness, humour, transcendent attachment, and the ability to affect regulation that serve as the foundation of coping appraisal (Block & Kremen, Citation1996). The brain’s ability to change in response to different experiences (Southwick & Charney, Citation2012)

Study findings revealed ego resiliency was based on a process that pertained to specific situational appraisal which was followed by an action to preserve or change a perceived threat to one’s health and welfare. Specific thoughts and actions were aimed at initiating and maintaining medical treatment, sensing what can harm, working towards a desired goal, and altering personal circumstances according to changing situations as they arose. Often, while the participant was task-oriented in solving problems and achieving a desired outcome or goal, they often times relied on external help to achieve self-efficacy. Thus, findings in this study reveal that ego resiliency served as a conduit in achieving self-efficacy that often required external help.

Self-determination

Definition

The ability to make decisions under one’s own guidance, use of autonomy, motivation, and competence based on enacting one’s own will successfully, and from relatedness and interactions with others. A concept of self-worth, which includes the ability to not get overwhelmed by hopelessness through embracing the attribute of perseverance (Deci & Ryan, Citation2012).

This study found that motivations for self-determination were derived from remembering good days and not dwelling on negative thoughts. Often the participant would confront the illness despite living with their personal struggles. Incentives towards self-determination came from accountability, and by a purpose and mission to ensure the future welfare and integrity of loved ones and community members that were valued by the participant. Outcomes of self-determination included individuals’ perceptions of having a purpose, meaning of existence, and motivation in life.

Hope

Definition

The attribute of hope is operationalized by beliefs that desired outcomes could and would occur, and can serve as a conduit to envision and strive towards those beliefs for a better future. Hope is associated with strategies and confronting stress, but also a sense of empowerment towards future goals (Scoloveno, Citation2016).

Significant findings of this study reveal that participants expressed hope when thinking about their future. One participant described watching others and being thankful that her illness was not worse. This perspective gave her the incentive to help herself, inducing hope for the future that her hypertension may go away and that she would be relieved of associated worries and restrictions. Reflection into the past and remembering good days gave participants the ability to look past current strife, and rather towards more hopeful and brighter futures for themselves. These forward-looking visions included improved physical functionality and spending quality time with loved ones, family, and friends. One participant was hopeful of maintaining independence and improving themselves through further education. These aspects helped form the participant’s identity and purpose in life.

Eidetic structure related to conceptual meanings of resilience: defining attributes, antecedents, and consequences

Aspects relating to defining attributes, antecedents, and consequences that were derived from the eidetic structure included how the study participant portrayed each section of resilience in order to clarify the meaning.

Defining attributes

Definitions

Self-esteem, self-reliance, social responsiveness, and self-worth (Deci & Ryan, Citation2012; Scoloveno, Citation2016). Active coping with adversity and challenge (Garcia Dia et al., Citation2013; Niitsu et al., Citation2017; Scoloveno, Citation2016). Expressing feelings and using skills (Garcia Dia et al., Citation2013).

Study findings revealed defining attributes of resilience included the following: acceptance of self and chronic illness were significant in contemplating, formulation, and institution of personal coping strategies, as was the development of self-determination despite facing difficulty. The ability to learn and formulate plans surrounding the chronic illness allowed individuals to discern symptoms that could indicate a problem, as well as triggers, and other harmful factors to avoid. Finally, developing awareness of personal coping mechanisms to counteract emotional and physical distress was an additional factor. Reliance on external help assisted in developing self-efficacy.

Antecedents

Definitions

Adversity that is psychologically or physically traumatic (Garcia Dia et al., Citation2013; Niitsu et al., Citation2017; Scoloveno, Citation2016), external social support, optimism and hope, and a positive outlook on situations (Scoloveno, Citation2016).

This study found that experiencing an emotional or physical health crisis or stress led to feelings of being overwhelmed, fearful, apprehensive, unable to move forward, or doubtful about the success of medical treatment that acted as a prelude to resilience. In comparison, reflection and elucidation of the illness was a precursor to optimism and hope that focused on future health goals.

Consequences

Definitions

The ability to cognitively appraise a situation to mediate stress and problem solve (Scoloveno, Citation2016). Using personal control and effective coping (Garcia Dia et al., Citation2013; Niitsu et al., Citation2017; Scoloveno, Citation2016). Portraying growth (Garcia Dia et al., Citation2013; Scoloveno, Citation2016). Embracing spirituality and a sense of control (Niitsu et al., Citation2017). Positively able to adapt to stressors with mild or no psychopathological symptoms (Niitsu et al., Citation2017).

Consequences of resilience found in this study include the ability to adjust, adapt, and maintain medical compliance in response to chronic illness treatment striving towards improving health. Personal growth, understanding of the illness, avoidance of detrimental factors, and complication prevention were other factors. Initiating and maintaining effective coping mechanisms in conjunction with health care providers, and the development of the meaning of perceptions of future health goals were based on temporal reflection of the past that impacted goals towards the achievement of self-efficacy, endurance, and perseverance. Through faith, participants reported assurance of God’s sustainability, as well as a sense of purpose and meaning in life.

Eidetic structure linkage to the traits of protective factors of resilience and poor resilient risk factors

Themes found in the eidetic structure that related to positive traits of protective factors of resilience included a sense of purpose, self-efficacy, having a proactive attitude towards maintaining and advocating to improve health, actively seeking out knowledge, initiating and maintaining medical compliance, self-identity, close family and community bonds, spiritual bonds, hopeful future goals, independence, and a strong work ethic. depicts study participants’ personal beliefs and strategies that demonstrate the traits associated with protective resilience factors.

Table IV. Participants’ traits associated with protective resilience factors.

depicts participants’ traits associated with protective resilience factors

Traits associated with poor resilient risk factors

Significant themes found in the eidetic structure that related to poor resilient risk factors were depression, anxiety, constant worry and fear about chronic illness, inability to cope, uncertainty associated with chronic illness, repeated stress, non-compliance with medical treatment, and withdrawal and isolation of oneself from others. depicts personal beliefs and actions with potential outcomes that relate to the traits associated with poor resilient risk factors.

Table V. Reported participant’ beliefs associated with poor resilient risk factors with potential outcomes.

depicts the reported participant’ beliefs associated with poor resilient risk factors with potential outcomes

Eidetic structure linkage to Polk’s resilience theory

Themes found in the eidetic structure that relate to Polk’s Resilience Theory in the areas of dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical patterns reveal specific aspects portrayed by the study participants. depicts aspects of reported participant resilience associated with these patterns.

Table VI. Reported participant’ resilience behaviors, attitudes, and actions associated with Polk’s resilience theory patterns.

Discussion

The eidetic structure demonstrated resilience patterns identified within Polk’s Resilience Theory and revealed that each study participant had their own unique journey that was based on the patterns of dispositional, relational, philosophical, and situational resilience (Polk, Citation1997, Citation2000).

Theme 1: journey of living with chronic illness, lived experience, and personal struggles

Thematic analysis provided evidence of dispositional patterns from Polk’s Resilience Theory, revealing that a participant’s first step towards recognition was based on their ability to assess that a health abnormality existed. This realization was critical to plan and implement the action of obtaining medical care to treat the problem. Once the participant learned of their diagnosis, they contemplated, and accepted it to cognitively formulate personal coping strategies towards medical treatment and compliance. This type of process revealed the energy transformations experienced in attaining resilience, and was often the case among participants despite facing perceived difficulties (Polk, Citation1997, Citation2000). The virtues of self-efficacy, self-confidence, and autonomy based on physical and ego-psychosocial attributes were demonstrated in the process of interpreting learned chronic disease information, and in the formulation of the actions taken towards initiating and maintaining medical treatment. Each of these virtues is an example of stress and coping appraisal, contemplating health situations, and formulating an action towards a resolution revealed by scholars (Bandura, Citation1977; Block & Kremen, Citation1996; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; Polk, Citation2000). Additional aspects discovered within this theme included positive perceptions of self that impacted a participant’s ability to create personal coping strategies aimed at decreasing or avoiding stress and detrimental health effects, and increasing perseverance and endurance revealed in phenomenology literature (Hassani et al., Citation2017; Kristjansdottir et al., Citation2018; Qiao et al., Citation2019; Rezaei et al., Citation2018; Van Wormer et al., Citation2011). Relational patterns revealed that valued partnerships with medical providers for the diagnosis, treatment, and maintenance of the illness were instrumental as outlined by Polk (Citation2000). Situational patterns coincided very closely with dispositional patterns and often followed the processes of appraisal of a specific situation, problem solving, and formulating an action towards achieving a goal through adaptation and energy transformation (Polk, Citation1997, Citation2000).

Theme 2: adapting to illness: experiencing loss related to illness, thankful its not worse, self-reliance, and reliance on others

Dispositional patterns from Polk’s Resilience Theory were revealed in this theme and subthemes. The first subtheme experiencing loss related to the illness included a sense of loss secondary to the chronic illness. A sense of loss may increase risk factors that are related to decreased self-identity, self-empowerment, and vulnerability. Outcomes may include loss of function, independence, dignity, and finally lower self-efficacy. Consequently, these factors can lead to poor resilience, higher psychopathology rates, and physical deterioration mentioned in literature (Cal et al., Citation2015; CDC, Citation2020; Hassani et al., Citation2017; Kim et al, Citation2019; Niitsu et al., Citation2017; Polk, Citation1997, Citation2000; Scoloveno, Citation2016). Likewise, a sense of loss can decrease patterns of relational, situational, and philosophical resilience as the participant may develop lower self-worth and growth, decreased coping abilities, and may even isolate themselves from others also revealed in literature (Bolton et al., Citation2016; Deci & Ryan, Citation2012; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; Polk, Citation1997, Citation2000).

The thankful it not worse subtheme demonstrated that the participant was able to observe others with more advanced chronic illness similar to their own and be thankful that their own circumstance was not as severe. The participant realized that if she could help herself with lifestyle and medical treatment for hypertension, she may avoid complications in the future. This constituted a dispositional pattern of realistic appraisal of the participants' own health status, and a trajectory towards relational and situational resilience. Consequently, the process of using chronic illness as a conduit towards self-advocacy, and medical treatment in specific situations by partnering with health care providers towards an improved outcome similar to Bolton et al. (Citation2016) meta synthesis findings. The self-reliance subtheme revealed dispositional patterns that included self-determination towards confronting the illness despite living with the personal struggles associated with it (Deci & Ryan, Citation2012; Polk, Citation2000). Perceptions that focused on remembering good days gave participants hope to look forward to the future and instilled purpose. This factor was found to be significant in the areas of dispositional and philosophical resilience (Polk, Citation2000). Self-assurance and responsibility were often linked to relational and situational patterns, and occurred when the individual partnered with healthcare workers, and other support networks to build a knowledge base about the chronic illness. Consequently, this instilled a feeling of power over one’s destiny and hope for the future (Scoloveno, Citation2016). The reliance on others subtheme revealed that relational and situational pattern development was a critical factor in building resilience. This finding was mainly based on external support given to the individual during times of crisis. External support was a significant finding in the areas of emotion, instrumental, and informational, which was experienced by the study participants to help formulate coping abilities and strategies similar to the Bolton et al. (Citation2016) meta synthesis.

Theme 3: motivational factors: self -preservation, support network: to self and others, spirituality

Motivational factors were found to be significant in this study in the process of adaptation to chronic illness. The subtheme self-preservation revealed that despite the participant feeling overwhelmed, anxious, fearful, and out of control from the associated stress related to chronic illness and life circumstances, she was able to rise above it. After contemplation, personal coping strategies were formulated to offset the stress and were evident in dispositional and situational pattern development (Polk, Citation2000). These coping strategies were aimed at decreasing or avoiding stress and detrimental health effects, and increased perseverance and endurance similar to phenomenological research findings (Hassani et al., Citation2017; Kristjansdottir et al., Citation2018; Qiao et al., Citation2019; Rezaei et al., Citation2018; Van Wormer et al., Citation2011).

In support network: to self and others, a sense of duty and responsibility to others who were valued by the participant was the focus and revealed dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical pattern development (Polk, Citation2000). Participants felt important and needed when they helped themselves and others. This created meaning and purpose in their own lives, which in turn encouraged the participants to invest into their own health and wellbeing for the benefit of others. Spirituality served as a foundational strength to the participants, and revealed dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical patterns of development (Polk, Citation2000). Foundations of personal and community support strengthened coping mechanisms for the individual. In turn, the participant was able to reciprocate advice and found purpose, discernment, and meaning in her life.

Theme 4: fear of the illness: worry and anxiety, overcoming the fear

Fear of the illness included the subtheme of worry and anxiety and was mostly related to the uncertainty that surrounded the chronic illness. Uncertainty induced feelings of being overwhelmed, apprehensive, unable to move forward, and doubtful of medical treatment success that increased the risk of developing poor resilience. Emotional dysregulation increased risk for psychopathology, physical deterioration, and overall poor health status. Ultimately, these risk factors could lead to decreased resilience in the areas of relational and philosophical pattern development due to decreased coping appraisal and mechanisms, or social isolation and lack of personal growth (Polk Citation2000). However, these factors also served as a prelude to resilience in dispositional and situational pattern development because the participant needed to formulate coping strategies as a response to the uncertainty (Polk Citation2000).

Study findings revealed that overcoming the fear required the process of living with the chronic illness, and finding out what it meant for the participant’s life to dissipate the fear and uncertainty that the participants felt when first diagnosed. The process of experiencing the illness and understanding the meaning led to new realization and elucidation, that the chronic illness was not as serious as originally thought (Giorgi et al., Citation2017). The ability to see the illness in a new light gave the participants the opportunity to gain control by learning and developing coping appraisal and mechanisms, being flexible, regulating actions, and accepting the illness that is revealed by scholars (Bandura, Citation1977; Block & Kremen, Citation1996; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; Polk, Citation2000). Consequently, dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical pattern development was evident in the process of acceptance, learning, and formulating coping mechanisms in conjunction with healthcare provider’s assistance (Polk, Citation2000). Lastly, the participants came to the realization that they could live a fairly healthy and normal life if they maintained medical treatment compliance and found meaning in their life (Polk, Citation2000).

Theme 5: progression: looking into the past, encouragement to others: living by example

Looking into the past gave temporal insight into the participants present and future life that elaborated personal meaning. This process developed a sense of regret, and a desire towards changing present circumstances to improve health and wellbeing for the future. Development of dispositional and situational patterns was revealed in the belief of one’s abilities to manage their life situations to include realistic goal orientation and achievement, and adaptability for the future (Polk, Citation2000). Lastly, philosophical patterns revealed that reflection on the lifeworld created a sense of purpose and meaning of one’s life towards greater self-knowledge and future life goals (Giorgi et al., Citation2017; Polk, Citation2000).

Study findings of encouragement to others: living by example revealed that participants each had future goals and hope for their health, as well as advice to others with similar diagnosis to their own. The ability to see their chronic illness to gain control towards future health and goal attainment was a defining attribute of dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical resilience (Polk, Citation2000). Specific personal advice offered was based on coping styles, accountability, prioritizing self-care and time with family and loved ones, and learning about chronic illness by paying attention to symptoms and learning triggers. Learning was reported to be very significant in helping individuals to feel empowered to enhance self-efficacy traits similar to studies conducted by Bolton et al. (Citation2016), Kristjansdottir et al. (Citation2018), and Qiao et al. (Citation2019). Further advice included the use of spirituality as a coping mechanism, maintaining a positive attitude, taking responsibility for oneself, and maintaining identity and independence.

Theme 6: deep faith in god, peace and comfort from god, asking god for guidance and strength

Philosophical patterns from Polk’s Resilience Theory identified that faith and spirituality are among the most important foundations in terms of being valued and utilized by the participants (Polk, Citation2000). Within the sub-theme drawing peace and comfort from God, spiritual transcendence occurred as participant’s perception of God was a foundational rock that was ever omniscient and unwavering. God was viewed as possessing an unlimited source of strength from which to draw wisdom, blessings, and peace in fostering endurance and fortitude. This, in turn, served as a conduit to build dispositional, relational, and situational patterns of development (Polk, Citation2000). Further, participants reported finding a purpose to life, as well as the meaning of their existence within the universe. Lastly, participants continued to perceive God as a firm foundation in their life, feeling as though they could face anything with God’s love, support, and strength. Asking for guidance and strength revealed the meaning of thoughtful prayer in daily life. Prayer was perceived to give wisdom, insight, and discernment that also enhanced dispositional, relational, and situational patterns of development. Similar to drawing peace and comfort from God, prayer also induced spiritual transcendence and a feeling of closeness to God that strengthened resilient patterns of development.

Theoretical implications

Polk (Citation2000) provides a framework to organize and explore patterns of resilience. This research further confirms the philosophical framework completely and depicts the convergence of the patterns to give a holistic view of a person’s resilience. Some areas of the patterns were more common in this population, highlighting potential areas that could be used to develop nursing interventions. Common patterns included dimensions of the self; enhancement of a firm knowledge base; responsibility towards self-care; reflection and elucidation; partnerships with healthcare providers; realistic appraisal; and spiritual transcendence.

Implication for practice

Nursing practice implications are based on the foundation of Polk’s (Citation1997) original purpose for developing her middle range resilience theory to assist providers caring for populations to understand the process of resilience. As Polk (Citation1997) described: to identify the process individuals use to transform a situation, build on it, and grow from it to enable nurses to better understand how this occurs to assist their patients towards wellness progression. As previously discussed, scholars identified that chronic illness progression directly relates to poor health outcomes in low-resourced communities (CDC, Citation2020; Connell et al., Citation2019; Gennuso et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2019). This study builds on the premise that nurses and health care workers are at the forefront of patient care, and in an ideal position to formulate individualized and community-based initiatives and interventions to enhance dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical resilient pattern development. This public health priority is a mandatory mission of health care workers who serve vulnerable populations that reside in low-resourced communities. Outreach programs through humanitarian groups and local communities can be utilized in the development of programs to enhance resilience.

Pattern development

Dispositional

Study findings revealed that a firm knowledge base is a critical element in building dispositional pattern development. Knowledge enhanced participants’ abilities to nurture components of the self. Dimensions of the self including positive perceptions, self-efficacy, self-confidence, and autonomy, were based on physical and ego-psychosocial attributes that increased perseverance and endurance. Study results also revealed that the dispositional traits of self-assurance and responsibility were formed as outcomes of building a strong knowledge base that was found to be a precursor to empowerment. Consequently, development of dispositional and situational patterns were revealed in the belief of one’s abilities to manage their life situations that included realistic goal orientation, responsibility, achievement, and adaptability for the future (Polk, Citation2000). When planning and developing initiatives and interventions to foster pattern development, consider strengthening aspects of the self; enhance a firm knowledge base with the clarification of unknown chronic illness patient concerns to enrich self-advocacy; and promote realistic coping appraisal, self-assurance, and responsibility towards self-care.

Relational

Relational pattern development revealed that valued partnerships with medical providers for the diagnosis, treatment, and maintenance of the illness were instrumental as outlined by Polk (Citation2000). Strengthening partnerships with healthcare providers and external support could decrease risk factors for low resilience pattern development. Relational pattern development was also enhanced by external support by way of receiving and giving to others. This was an exceptionally important aspect of the participant’s identity and self-worth by feeling important and needed when they helped themselves and others. Self-worth created meaning and purpose in their own lives, which in turn encouraged participants to invest in their own health and wellbeing for the benefit of others. Personal and community support derived from spirituality also strengthened coping mechanisms for participants. In turn, participants were able to reciprocate advice while finding purpose and discernment. When planning and developing initiatives and interventions to foster pattern development, consider clarifying the meaning and enhancing self-value and worth that can lead to empowerment; assess perceptions of the value and meaning of external relations that impact self-care; foster meaningful external connections that the individual values in care; and identify and institute relational systems for those who lack external support.

Situational

Situational pattern development coincided very closely with dispositional traits and often functioned together. Energy transformations required processes of situational appraisal that incorporated contemplation and problem-solving abilities to achieve a goal through adaptation (Polk, Citation1997, Citation2000). Firm knowledge bases helped form coping abilities and strategies in varied and changing illness situations. The process of elucidation helped participants see illness in a new light towards acceptance and adaptation, as well as enhancement of situational pattern development. A significant finding in this study revealed that identifying chronic illness symptoms and learning triggers to avoid detriments to health impacted both situational pattern development and quality of life. Elucidation processes towards gaining control and acceptance of situational circumstances are critically important for nurses to understand when planning and formulating chronic illness strategies such as education and interventions to counter-act poor resilient risk factors and detrimental pattern development. By focusing on realistic appraisal of chronic illness situations, nurses could focus the person away from despair, rumination, and the detriments of higher psychopathology rates as well as physical deterioration discussed in the literature (Cal et al., Citation2015; CDC, 2020; Kim et al, Citation2019; Jackson et al., Citation2018; Niitsu et al., Citation2017). When planning and developing initiatives and interventions to foster pattern development, consider promoting realistic coping appraisal and mechanisms; providing firm knowledge bases and insight; encouraging elucidation and insight into new realizations of meaning of illness on the life world towards gaining control and acceptance of circumstances. Clarify medical health information and enhance education regarding diagnosis and treatment; maintain reassurance; foster positive alteration of coping styles; prioritize self-care strategies; and cultivate identification of chronic illness symptoms that include learning triggers to avoid health detriments.

Philosophical

Philosophical pattern identification revealed that faith and spirituality are the most important foundations valued by participants towards impacting resilience (Polk, Citation2000). Faith served as a monumental strength to participants, functioning as a conduit to dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical patterns of development (Polk, Citation2000). Patterns were enhanced by spiritual transcendence, endurance, fortitude, and perseverance. Reflection on past and present circumstances also helped participants compensate for their current personal difficulties and struggles. This study identified that having the ability to see illness in a new light perpetuated the individual to seek new opportunities for learning to refine their coping appraisal and mechanisms towards empowerment. The elucidation process is critically important for nurses to understand when planning and formulating strategies, and interventions to counteract the detrimental effects of chronic illness and life circumstance stress towards present and future health goals. When planning and developing initiatives and interventions to foster pattern development, consider assessing the meaning of spirituality to the individual that incorporates identity and self-worth; encourage free discussions of faith and traditions that are important to the individual; and inspire reflection of the chronic illness course to induce insight and elucidation towards present and future health goals.

Future studies

This study offers foundational evidence to encourage a focus on dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical pattern development from a life world perspective towards improving health outcomes for low-resource communities. Logical next steps would be to implement pattern enhancements and assess if they counteract the poor resilient risk factors within the life world perspective. Future studies should be conducted in person to build trust within the community, as well as to gain a better understanding of their culture, social determinants of health, and environment.

Conclusions

The findings of this descriptive phenomenological study reveal that the lived experience of resilience while living with chronic disease and low-resource communities is a unique existential phenomenon for the study participants. The eidetic structure and essence revealed six themes and subthemes that interconnected with the complex and multidimensional meanings of resilience. This method transformed implicit factors to explicit meanings within the participants’ lifeworld. The outcome seeks to reach temporal insight towards personal meaning and understanding.

Linking the eidetic structure to the building blocks and conceptual meanings of resilience, traits of protective factors of resilience, and poor resilient risk factors revealed strengths and weaknesses within the lifeworld of the participant. Further, eidetic structure linkage to Polk’s Resilience Theory in dispositional, relational, situational, and philosophical areas uncovered complex and multi-dimensional meanings, as well as pattern development of resilience. Fostering increased pattern development has the potential to improve health outcomes, well-being, and quality of life across the spectrum.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are discussed below. The sample focused only on African-Americans in a small town within Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, which impacts the generalizability of the study. The sample size included 11 total participants; however, the researcher only gained relevant information applicable to this study’s research question from 8 participants. Some participants did not feel comfortable opening up to the researcher. One man was included in the sample size, indicating that more gender diversity is needed to gain male perspectives on the research topic. Reasons for the small sample size include the following: the limited availability of willing participants due to lack of access to the internet; some potential participants did not feel comfortable leaving their homes during the COVID-19 pandemic to travel to the local clinic to use the computer, and the research was performed by a white female doctoral student who was interviewing participants of African descent. The researcher was located in the Northeastern region of the USA and had no prior experience working or residing in the Mississippi Delta geographical region. Limited data was obtained regarding specific aspects of the impact of socioeconomic status on the participants lived experience and the phenomenon of resilience. The interviews were conducted via Zoom technology due to the national pandemic. Perhaps, in-person interviews would have allowed the researcher to gain more trust and obtain more data.

Implications

Results of the study provided important implications related to enhancing resilience pattern development for individuals suffering from chronic illness that reside in low-resourced communities. It also served to clarify the meaning of resilience in the study participants for further research and practice.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest. This study was not funded.

Acknowledgments

The researcher would like to thank the study participants for sharing their personal experiences and taking part in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tara Leigh Moore

Tara Leigh Moore is a cardiology nurse practitioner and bedside nurse certified through the American Nurse Credentialing Center.

References

- Amankwaa, L. (2016). Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 23(3), 121–17. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29694754/

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

- Block, J., & Kremen, A. M. (1996). IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 70(2), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.349

- Bolton, K. W., Praetorius, R. T., & Smith- Osborne, A. (2016). Resilience protective factors in an older adult population: A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. Social Work Research, 40(3), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svw008

- Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl 2), 19–31. (Washington,D.C.:1974). https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S206.

- Cal, F. S., Ribero de Sa, L., Glustak, M. E., Santiago, M. B., & Walla, P. (2015). Resilience in chronic diseases: A systematic review. Cogent Psychology, 2(1), 1–9. 1024928. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2015.1024928

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Chronic disease in America. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, April 27). National center for health statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/heart_disease_mortality/heart_disease.htm

- Christensen, M., Welch, A., & Barr, J. (2017). Husserlian descriptive phenomenology: A review of intentionality, reduction and the natural attitude. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 7(8), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v7n8p113

- Connell, C. L., Wang, S. C., Crook, L., & Yadrick, K. (2019). Barriers to healthcare seeking and provision among African American adults in the rural Mississippi Delta Region: Community and provider perspectives. Journal of Community Health, 44(4), 636–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00620-1

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 416–436). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249215.n21

- Garcia Dia, M., DiNapoli, J. M., Garcia-Ona, L., Jakubowski, R., & O’Flaherty, D. (2013). Concept analysis: Resilience. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(6), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2013.07.003

- Garmezy, N. (1993). Children in poverty: Resilience despite risk. Psychiatry, 56(1), 127–136. doi:10.1080/00332747.1993.11024627

- Gennuso, K. P., Jovaag, A., Catlin, B. B., Rodock, M., & Park, H. (2016). Assessment of factors contributing to health outcomes in the eight states of the Mississippi Delta Region. Prevention in Chronic Disease, 13. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.150440

- Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach. Duquesne University Press.

- Giorgi, A., Giorgi, B., & Morley, J. (2017). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In C. Willig & W. Stainton Rogers (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology (2nd ed, pp. 176–192). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526405555.n11

- Hassani, P., Izadi-Avanji, F. S., Rakhshan, M., & Majd, H. A. (2017). A phenomenological study on resilience of the elderly suffering from chronic disease: A qualitative study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S121336

- Husserl, E. (1962). Phenomenological psychology (J. Scanlon, Trans.). Routledge.

- Husserl, E. (2012). Ideas: General introduction to pure phenomenology. Routledge.

- Jackson, L., Jackson, Z., & Jackson, F. (2018). Intergenerational resilience in response to the stress and trauma of enslavement and chronic exposure to institutionalized racism. Journal of Clinical Epigenetics, 4(3:15), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.21767/2472-1158.1000100

- Kim, J. H., Lewis, T. T., Topel, M. L., Mubasher, M., Li, C., Vaccarino, V., Mujahid, M. S., Sims, M., Quyyumi, A. A., Taylor, H. A., & Baltrus, P. T. (2019). Identification of resilient and at risk neighborhoods for cardiovascular disease among black residents: The Morehouse –Emory Cardiovascular (MECA) center for health equity study. Preventing Chronic Disease Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(E57), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.180505

- Kim, G. M., Lim, J. Y., Kim, E. J., & Park, S. (2018). Resilience of patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(4), 797–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12620

- Korstjens, I., & Moser, A. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. The European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

- Kristjansdottir, O. B., Stenberg, U., Mirkovic, J., Krogseth, T., Ljosa, T. M., Stange, K. C., & Ruland, C. M. (2018). Personal strengths reported by people with chronic illness: A qualitative study. Health Expectations, 21(4), 787–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12674

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry (1st Ed. ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

- Mississippi State Department of Health. (2016). Office of rural health and primary care: Mississippi primary care needs assessment March. 2016. https://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/resources/7357.pdf.

- Niitsu, K., Houfek, J. F., Barron, C. R., Stoltenberg, K. A., Kupzyk, K. A., & Rice, M. J. (2017). A concept analysis of resilience integrating genetics. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(11), 896–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1350225

- Noonan, A. S., Velasco-Mondragon, H. E., & Wagner, F. A. (2016). Improving the health of African Americans in the USA: An overdue opportunity for social justice. Public Health Reviews, 37(12), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4

- Polk, L. V. (1997). Toward a middle-range theory of resilience. Advances in Nursing Science, 19(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-199703000-00002

- Polk, L. V. (2000). Development and validation of the Polk resilience patterns scale (Publication No. 996559) [ Doctoral dissertation, Catholic University of America]. ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis Global.

- Qiao, S., Ingram, L., Morgan, D., Xiaoming, L., & Weissman, S. B. (2019). Resilience resources among African American women living with HIV in southern United States. AIDS, 33(1), S35–S44. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002179

- Rezaei, M., Sadat Izadi-Avanji, F., Safa, A., & Fernanda Cal, S. (2018). The impact of resilience on the perception of chronic diseases from older adults’ perspective. Client Centered Nursing Care, 4(4), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.32598/jccnc.4.4.231

- Robinson, M., Hanna, E., Raine, G., & Robertson, S. (2019). Extending the comfort zone: Building resilience in older people with long term conditions. Southern Gerontology Society, 38(6), 825–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464817724042

- Rutter, M. (1990). Psychosocial relience and protective mechanisms. In J. Rolf, A. Masten, D. Cicchetti, K. Nuechterlein, & S. Weintraub (Eds.), Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology: Social competence in children, 3. (pp. 49–74). University Press.

- Scoloveno, R. (2016). A concept analysis of the phenomenon of resilience. Journal of Nursing and Care, 5(353), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-1168.1000353

- Southwick, S.M., & Charney, D.S. (2012). The science of resilience: Implications for the prevention and treatment of depression. 338(1), 79–82. 10.1126/science.1222942

- Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to … assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17(6), 596–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13242

- Sturmberg, J. P., Picard, M., Aron, D. C., Bennett, J. M., Bircher, J., deHaven, M. J., Gijzel, S., Heng, H. H., Marcum, J. A., Martin, C. M., Miles, A., Peterson, C. L., Rohleder, N., Walker, C., Olde Rikkert, M., & Melis, R. (2019). Health and disease-emergent states resulting from adaptive social and biological network interactions. Frontiers in Medicine, 6, 59. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2019.00059

- Sundler, A. J., Lindberg, E., Nilsson, C., & Palmer, L. (2019). Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nursing Open, 6(1), 733–739. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.275

- Tokwe, L., & Naidoo, J. R. (2020). Lived experience of human immunodeficiency virus and hypertension in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2472

- Van Wormer, K., Sudduth, C., & Jackson, D. W., 111. (2011). What can we learn of resilience from older African American women: Interviews with women who worked as maids in the deep south. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 21(4), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2011.561167