ABSTRACT

Introduction

This systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies provides an overview of barriers and facilitators that breast cancer patients experience in weight management interventions.

Methods

We included qualitative studies describing barriers and facilitators for weight management interventions as experienced by adult breast cancer patients after the completion of initial treatment . The data was extracted and using thematic analysis.

Results

After analysis, eleven themes were determined. Six of those themes could be linked to the Attitude, Social Influence and self Efficacy (ASE)-model. Physical and mental benefits, anticipated regret and a lack of motivation were linked to attitude. Integrating a weight management programme in daily life, stigma and fears were linked to self-efficacy. With regard to the social influence determinant, encouragement and discouragement by family members were developed as a theme. Four additional themes were conducted related to weight management behaviour; external barriers, economic barriers, cultural barriers and physical barriers. In addition, integrating weight management in cancer care was described as a separate theme.

Conclusions

Several disease specific issues, including feeling stigmatized after cancer treatment and treatment-related side effects and peer-support should be given specific attention to maximize adherence of weight management programmes.

Introduction

Unintended weight gain is one of the three most experienced long-term health problems among people treated for early-stage breast cancer and was first reported by J.K. Dixon et al. in 1978 (Dixon et al., Citation1978). Especially in those undergoing chemotherapy, bodyweight can increase significantly during treatment (van den Berg et al., Citation2017). A descriptive, correlational study found a significant increase of more than 2.5 kg in 63.5% of women one year after the start of treatment with chemotherapy, which negatively affected their quality of life (McInnes & Knobf, Citation2001). Even after two years, 68% of the women maintained a significant weight gain.

While the exact cause of unintended weight gain after breast cancer treatment remains unclear, current evidence suggests that treatment with chemotherapy results in more weight gain compared to localized treatment (surgery with or without radiation) alone (Demark-Wahnefried et al., Citation2001). Moreover, weight gain was more often seen in patients treated with more extensive protocols and multi-agent therapies (Vance et al., Citation2011). While an association with the use of tamoxifen alone has not been shown, corticosteroids like dexamethasone and prednisone, which are often prescribed during breast cancer treatment to treat nausea and inflammation, can increase appetite and can therefore contribute to structural weight gain (Faber-Langendoen, Citation1996; Goodwin et al., Citation1988).

Besides treatment-related side-effects, a younger age and treatment-induced premature menopause have been associated with excessive weight gain (Makari-Judson et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, it is plausible that behavioural change, like reduced physical activity, also contributes to unwanted weight gain. It is well documented that breast cancer survivors have reduced physical activity levels, compared to pretreatment, and compared to the general population (Broderick et al., Citation2014; Ee et al., Citation2020; Irwin et al., Citation2003).

Weight gain after initial treatment can eventually lead to overweight or obesity. Overweight and obese breast cancer survivors are at increased risk of cancer recurrence and have higher all-cause mortality (Anbari et al., Citation2019). Obesity also has a negative impact on breast cancer survivors’ quality of life (QoL), and it increases the risk of longer-term morbidities such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (Anbari et al., Citation2019). Prevention of weight gain, both during treatment and in the survivorship phase, should therefore be given due consideration.

To date, there have been a limited number of weight management intervention studies, with short follow-up and small sample-sizes. Although the optimal weight loss intervention for breast cancer patients has not yet been determined, some studies on comprehensive multimodal weight loss interventions have shown promising effects on body weight, BMI, waist circumference and overall quality of life (Playdon et al., Citation2013; Shaikh et al., Citation2020).

For a weight management intervention to be successfully implemented, the barriers and facilitators for uptake of the intervention (components) should be clarified and adequately addressed in the intervention design.

Previous quantitative research has identified common barriers for healthy behaviour of breast cancer patients and survivors. This includes a high level of distress, fatigue, lack of motivation, psychosocial problems after breast cancer treatment, and a lack of service provision around weight gain prevention and weight management (Broderick et al., Citation2014; Ee et al., Citation2020; Howard-Anderson et al., Citation2012; Ventura et al., Citation2013).

Qualitative research enhances this knowledge, by providing in depth insights in patients’ personal motives, their views about essential components of weight management interventions, and the barriers and facilitators they experience (Evans, Citation2002). Qualitative meta-synthesis can indicate the level of overall saturation of these topics, and provide a structured summary of the available evidence, and thereby improve the interpretation of qualitative research findings (Goodman, Citation2008).

Therefore, the aim of this study is to provide a thematic overview of high-quality qualitative research investigating the barriers and facilitators that people with breast cancer experience for participating in and adhering to interventions regarding weight management. The results can be used in the further development and implementation of patient-oriented weight management interventions that are likely to be acceptable in clinical practice.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted between July 2021 and April 2022. The protocol for the review was registered in PROSPERO under the ID number: CRD42021233420 on 22 April 2021: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO. The PRISMA 2009 checklist was used as a guideline for reporting (Page et al., Citation2021).

Database search

Four databases (Medline, Embase, Psychinfo, and Cinahl) were systematically searched for relevant qualitative papers, considering barriers and facilitators for weight management among breast cancer survivors. The search was conducted by an experienced medical information specialist. A forward and backward citation search was made, to avoid missing relevant papers. The complete search strategy is included in supplementary Appendix 1.

Study selection

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they comprised qualitative research, such as focus group studies, semi-structured interviews, or mixed-methods studies. Eligible studies explored barriers and facilitators for exercise, diet and/or weight management programmes, in samples of adults (>18 yr), who had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were not currently undergoing “active” treatment (defined as surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy). Studies among cancer survivors undergoing hormonal therapy were also eligible.

We excluded non-English studies. Furthermore, articles were also excluded when they did not describe original research (e.g., study protocols, synopses, or systematic reviews) or when full texts were not available (e.g., in case of congress abstracts).

To gain a broad perspective on barriers and facilitators for weight management programmes, we included studies describing outcome expectations of weight management programmes under development, as well as studies evaluating existing programmes (perceived barriers and facilitators).

Two researchers (ST and SVD) independently screened and labelled all retrieved records based on title and abstract using Rayyan QCRI software (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Of the remaining papers, full-text articles were retrieved for critical appraisal.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data on study design (data collection methods), sample characteristics (sample size, age, sex, cancer stage, and time since diagnosis) and participant selection details were extracted and described separately for each study (). All text labelled as “results”, or “findings” were extracted electronically and entered in a qualitative data analysis computer programme (NVivo 10). Results included author narrative, as well as participant quotes. Data extraction forms were checked by the two reviewers separately to ensure accuracy.

Table I. Study characteristics.

Quality appraisal was performed independently by two reviewers (ST and SVD) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (Zeng et al., Citation2015). The CASP is a widely used 10-item checklist, which systematically evaluates the internal validity, the external validity and the study results of each paper. Scoring of the items was done using reviewer guidelines adopted from Butler et al (Butler et al., Citation2016). Each reviewer assigned an overall quality rating of “high”, “medium”, or “low” to all papers. In case of disagreement, discussion was held until consensus was reached. Only high-quality studies were included in this systematic review.

Theoretical framework and data synthesis

Analysing of the data was performed by a mixed-methods design. First, all extracted data was analysed using thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). In the first stage, all fragments considering barriers, facilitators, preferences, experiences, essential components or requirements for a health intervention were extracted and coded line by line. In the second stage, two researchers generated and checked a preliminary code list. The moment that the most recent published articles didn’t contain anymore new codes, saturation was reached. Similar codes were collapsed, after which the codes were grouped into themes. In the third stage, themes were, if possible, linked to one of the core concepts of a theoretical framework. Multiple theoretical frameworks for behavioural change were considered and discussed by the researchers until consensus was reached. We used the social psychology model on behavioural intention (ASE-model), developed by de Vries et al. (see supplementary Appendix 2) (de Vries et al., Citation1995). In the ASE-model, it is assumed that behavioural intention and subsequent behaviour can be explained largely by three cognitive components; Attitudes, Subjective norm and self-Efficacy (ASE). A person’s attitude is formed by the cognitive and emotional consequences a person expects from this behaviour and the value attached to those consequences. Consequences include instrumental aspects (such as physical benefits) as well as emotional aspects (such as enjoyment or dislike). Subjective norm is the resultant of perceived social norms (i.e., due to experienced support or peer pressure), and the extent to which someone is inclined to conform to such norms. Self-efficacy refers to a person’s belief of his capability to perform and maintain the desired behaviour. In addition to the three main components of the ASE model, a person’s behaviour could also be influenced by environmental factors, such as the physical, cultural, or the economic environment (Congdon, Citation2019). These factors were therefore also considered as part of the theoretical framework. Remaining themes that did not fit the ASE-model were grouped into additional themes. Initial and final themes were discussed within the larger research group for triangulation.

Ethics approval

As this study does not involve human participants, ethical approval does not apply.

Results

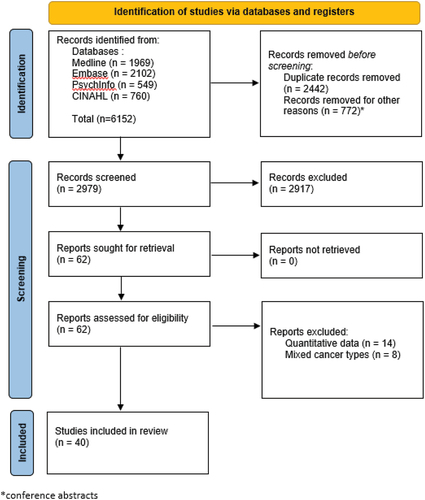

A total of 6152 records were retrieved. After the removal of 2442 duplicates, 2979 titles and abstracts, and 62 full texts were screened for eligibility. Of the full texts, 40 studies were included after the initial search. A flow diagram of inclusion and exclusion of the retrieved publications is depicted in .

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only.

Focus groups were used in nine studies, semi-structured interviews were used in 27 studies, and mixed-methods in four studies. Overall, one third of the studies was conducted in the USA, one third in Canada and one third in other countries. In 28 studies, an existing intervention was evaluated. The other 12 studies dealt with general views on nutritional and exercise programmes. Of all studies, 6 studies considered physical exercise and or nutrition (programmes) explicitly in the context of weight management, the remainder addressed physical activity or nutrition in a broader sense. For ease of reading, and since physical activity and nutrition are both essential elements in weight management, all interventions are further referred to as “weight management”, unless findings were specific for exercise or nutrition.

Disagreement in labelling occurred in less than 3% of the labels and was resolved through discussion in all cases.

summarizes the included study characteristics and outcomes.

Quality of the evidence

Although the relationship between de researcher and the participants of the study was not adequately considered in 85% of the articles, still all articles were considered high quality.

Results of the data synthesis

After analysis, eleven themes were determined. Six of those themes could be linked to determinants in the ASE-model. Physical and mental benefits, anticipated regret and a lack of motivation were linked to attitude. Integrating a weight management programme in daily life, stigma and fears were linked to self-efficacy. The theme encouragement and discouragement by family members was linked to the subjective norm determinant. Besides the themes related to determinants of the ASE-model, four additional themes were developed related to weight management behaviour; external barriers, economic barriers, cultural barriers and physical barriers. In addition, integrating weight management in cancer care was described as a separate theme. Participant quotes are depicted in to illustrate the developed themes.

Table II. Quotes and fragments illustrating the themes.

Attitude

Physical and mental benefits

Besides weight control (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Leddy, Citation1997; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009), physical benefits like improving general health, promoting recovery, increasing energy, improving sleep, and improving survival contributed to a positive attitude towards weight management interventions (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Mackenzie, Citation2015; Owusu et al., Citation2018; Rogers et al., Citation2004). These advantages were mostly experienced by participants who attended a weight management programme. Improved strength was mentioned in five papers (Balneaves et al., Citation2014; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020; Pullen et al., Citation2019; Wurz et al., Citation2015), more energy or feeling better overall was mentioned in as much as ten papers (Balneaves et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; Ingram et al., Citation2010; Jones et al., Citation2020; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020; Piacentine et al., Citation2018; Power et al., Citation2020; Pullen et al., Citation2019; Wurz et al., Citation2015). In four papers, participants described how the programme helped them manage their treatment-related side-effects (Balneaves et al., Citation2020; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2020; Wurz et al., Citation2015).

In three papers, it was stated that people derived enjoyment from exercise (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Jones et al., Citation2020; Nock et al., Citation2015), and in six papers, people described exercise or weight management as something positive they could do for themselves (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Kokts-Porietis et al., Citation2019; Wurz et al., Citation2015; Yufe et al., Citation2019). Participants indicated that they expected benefit to psychological outcomes, like a better self-image and managing stress (Pila et al., Citation2018; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009). This outcome expectation was met in many of the studies evaluating existing programmes for weight management, which found that participants felt mentally better and uplifted (Balneaves et al., Citation2020; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Ingram et al., Citation2010; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020; Nock et al., Citation2015; Owusu et al., Citation2018; Piacentine et al., Citation2018; Shaw et al., Citation2021; Wurz et al., Citation2015). In multiple papers, it was indicated that healthy lifestyle contributed positively to the transition from being a cancer patient to being a health-conscious individual (Balneaves et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Kokts-Porietis et al., Citation2019; Vassbakk-Brovold et al., Citation2018; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009; Wurz et al., Citation2015).

Anticipated regret

Anticipated regret or moral obligation was indicated to be a motivator for a lifestyle programme. Moral obligation refers to the responsibility a person feels to, for instance, follow a lifestyle intervention because of personal beliefs and values. People commented that exercising was their own responsibility (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Fazzino et al., Citation2016; Leddy, Citation1997). Anticipated regret was mentioned in the sense that participants indicated that not following the programme gave them a bad conscience (Husebø et al., Citation2015; Short et al., Citation2013).

Lack of motivation

A negative affective attitude, on the other hand, in the sense of “not liking exercise”, or “not liking the gym” was mentioned in three different papers (Hefferon et al., Citation2013; Jones et al., Citation2020; Short et al., Citation2013). Some people experienced a lack of motivation for exercising in general or did not feel that exercising was a priority (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Rogers et al., Citation2004; Short et al., Citation2013; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009). Even after evaluation of existing interventions, many people were not motivated, got bored with keeping up with the exercises, or missed the pleasure of good food (Fazzino et al., Citation2016; Hefferon et al., Citation2013; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Kokts-Porietis et al., Citation2019; Milosevic et al., Citation2020; Piacentine et al., Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2017; Vassbakk-Brovold et al., Citation2018; Yufe et al., Citation2021). One person indicated that he was afraid that too much exercise could increase the risk of recurrence (Kim et al., Citation2020).

Self-efficacy

Integrating the programme in daily life

Participants often struggled with combining a training programme or diet with work and/or household responsibilities. Conflicting priorities like going back to work, care giving tasks or social obligations were cited in 14 papers (Balneaves et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Brunet et al., Citation2013; Hefferon et al., Citation2013; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Ingram et al., Citation2010; Mackenzie, Citation2015; Milosevic et al., Citation2020; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020; Piacentine et al., Citation2018; Sander et al., Citation2012; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009; Wurz et al., Citation2015; Yufe et al., Citation2019). A lack of time and scheduling conflicts were often referred to as barriers for incorporating lifestyle changes in their daily life (Jones et al., Citation2020; Leddy, Citation1997; Loh et al., Citation2011; Milosevic et al., Citation2020; Rogers et al., Citation2004; Short et al., Citation2013; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009; Wurz et al., Citation2015).

Stigma and fears

Also, on a psychological level, people experienced limitations that lowered their level of self-efficacy.

Participants described the impact of physical side-effects like hair-loss or a changed body after mastectomy on their self-esteem, and how this made them feel stigmatized and kept them from exercising in public (Brunet et al., Citation2013; de Kruif et al., Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2020; Nielsen et al., Citation2020; Power et al., Citation2020; Sander et al., Citation2012; Smith et al., Citation2017; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009; Yufe et al., Citation2021). Impaired concentration attributed to chemotherapy treatment was also mentioned (Balneaves et al., Citation2014). Participants were worried that exercise would exacerbate lymphoedema, or they associated exercise with physical pain (Rogers et al., Citation2004). Fear of exposure to infection was also mentioned in multiple papers (Loh et al., Citation2011; Nielsen et al., Citation2020; Rogers et al., Citation2004).

Social influence

Encouragement and discouragement by family members and peers

Subjective norm played an important role in participant’s lifestyle habits. Support from family or close ones from a non-cancer environment was a strong motivator (Balneaves et al., Citation2014; Brunet et al., Citation2013; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Loh et al., Citation2011; Mackenzie, Citation2015; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020), as was the support of fellow cancer patients (Balneaves et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; de Kruif et al., Citation2021; Fazzino et al., Citation2016; Jones et al., Citation2020; Lloyd et al., Citation2020; Loh et al., Citation2011; Mackenzie, Citation2015; Milosevic et al., Citation2020; Nielsen et al., Citation2020; Nock et al., Citation2015; Piacentine et al., Citation2018; Pullen et al., Citation2019; Rogers et al., Citation2004; Shaw et al., Citation2021; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009; Wurz et al., Citation2015). The need for an exercise buddy was mentioned in three papers (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Owusu et al., Citation2018; Piacentine et al., Citation2018).

In a few studies, participants mentioned being discouraged to exercise by their family due to the fear of being infected (Loh et al., Citation2011; Nielsen et al., Citation2020). Also, family members sometimes encouraged patients to rest (Sander et al., Citation2012), they misinterpreted weight loss as an indication of progression of cancer (Balneaves et al., Citation2014), or feared that high intensity of exercise might induce cancer recurrence (Kim et al., Citation2020).

External barriers

Travel distance, poor access to or inadequacy of physical exercise facilities, restricted gym hours, or the absence of suitable equipment was found to be an external barrier for attending or maintaining exercise sessions in the context of weight management (Balneaves et al., Citation2014; Brunet et al., Citation2013; Hefferon et al., Citation2013; Piacentine et al., Citation2018; Short et al., Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2017). Moreover, in some existing programmes, exercises were deemed too difficult, or not properly explained (Balneaves et al., Citation2020; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Kim et al., Citation2020; Piacentine et al., Citation2018). Sometimes, filling out questionnaires or writing up daily food intake was experienced as too time consuming (Fazzino et al., Citation2016; Vassbakk-Brovold et al., Citation2018). Weather conditions was mentioned as a barrier for exercising outdoors in 11 papers (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Fazzino et al., Citation2016; Hefferon et al., Citation2013; Ingram et al., Citation2010; Jones et al., Citation2020; Kokts-Porietis et al., Citation2019; Loh et al., Citation2011; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020; Owusu et al., Citation2018; Rogers et al., Citation2004; Smith et al., Citation2017).

Economical and cultural barriers

In six studies, participants indicated that costs were a barrier for participating or maintaining a healthy lifestyle or participating in a a weight management programme (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Hefferon et al., Citation2013; Rogers et al., Citation2004; Short et al., Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2017; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009). In two papers, cultural barriers, in the sense of prioritizing a weight management programme over traditional female-caring roles was a problem (Loh et al., Citation2011; Smith et al., Citation2017). For instance, this was found in a study conducted in Malaysia, where participants were women with strong ties of extended family culture (Loh et al., Citation2011).

Physical barriers

Participants experienced many physical impairments due to treatment-related side-effects, or comorbidities that kept them from exercising or from maintaining a weight management programme. Extreme fatigue, a lack of energy and complaints such as nausea or dizziness constituted a serious challenge, as recorded in 20 papers (Balneaves et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Brunet et al., Citation2013; Fazzino et al., Citation2016; Hirschey et al., Citation2017; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Ingram et al., Citation2010; Jones et al., Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2020; Loh et al., Citation2011; Mackenzie, Citation2015; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020; Nock et al., Citation2015; Power et al., Citation2020; Pullen et al., Citation2019; Rogers et al., Citation2004; Short et al., Citation2013; Vassbakk-Brovold et al., Citation2018; Wurz et al., Citation2015; Yufe et al., Citation2021). Lymphoedema was indicated as a barrier for exercise in ten papers (Hefferon et al., Citation2013; Kim et al., Citation2020; Milosevic et al., Citation2020; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020; Owusu et al., Citation2018; Pullen et al., Citation2019; Sander et al., Citation2012; Short et al., Citation2013; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009; Wurz et al., Citation2015). Sometimes, unplanned hospital admissions or medical complications disrupted the programme (Husebø et al., Citation2015; Ingram et al., Citation2010). Moreover, women indicated that wearing breast prostheses or a wig were a barrier to attend classes (Husebø et al., Citation2015; Kim et al., Citation2020; Nock et al., Citation2015; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009). In two papers, participants indicated that the weight gain itself was a barrier for exercise (Hefferon et al., Citation2013; Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020).

Integrating weight management in cancer care

In three papers, it was stated by the participants that a weight management intervention should be part of standard breast cancer care and offered early in the cancer treatment trajectory (Balneaves et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Piacentine et al., Citation2018). A preference for home-based exercises, outside the hospital setting was also mentioned (Brunet et al., Citation2013; Husebø et al., Citation2015; Milosevic et al., Citation2020), although participants also indicated the need for support of knowledgeable professionals with extensive experience in guiding breast cancer patients (Balneaves et al., Citation2014; Lloyd et al., Citation2020; Nielsen et al., Citation2020; Nock et al., Citation2015; Rogers et al., Citation2004; Whitehead & Lavelle, Citation2009). Personalized and one-on-one supervision was frequently mentioned as important (Brunet & St-Aubin, Citation2016; Jones et al., Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2020; Pullen et al., Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2019). In one study, the need for specific information about safety and health benefits of exercise and weight maintenance during chemotherapy was discussed (Nielsen et al., Citation2020). A motivating and encouraging instructor was considered desirable (Brunet & St-Aubin, Citation2016; Bulmer et al., Citation2012; Husebø et al., Citation2015) and participants valued regular check-ups to monitor their performance (Ingram et al., Citation2010; Kokts-Porietis et al., Citation2019; Lloyd et al., Citation2020; Nielsen et al., Citation2020). With regard to supportive materials, menu planning and healthy recipes were considered convenient (Balneaves et al., Citation2014; Nock et al., Citation2015), as were easy-to-use individualized apps (Monteiro-Guerra et al., Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2015). Finally, Yoga as a part of a lifestyle programme was considered of additional value by participants in three papers (Milosevic et al., Citation2020; Rogers et al., Citation2004; Van Puymbroeck et al., Citation2013).

Discussion

With this systematic review and qualitative meta synthesis, we aimed to summarize the findings from the available qualitative literature, to inform the development and implementation of weight management interventions for people with breast cancer.

We found that barriers and facilitators for weight management interventions fit largely within the ASE model. That is: reported barriers are generally related to attitude, subjective norms and self-efficacy. Additionally, external barriers including economic, cultural, and physical barriers were identified. Some of these were cancer specific, such as fear of worsening symptoms or experiencing stigma. We also elicited views and preferences related to how to best integrate weight management into cancer care. Here, the importance of early attention to weight management and personalized support from knowledgeable professionals stood out.

Implications for developing weight management interventions

The meta-synthesis has several implications for the development and implementation of weight management programmes for people with breast cancer. First, for effecting behavioural change, ensuring social support is essential. This could be achieved by engaging patients’ own support system or through patient support groups. In particular, attention should be given to sources of subjective norms that actively discourage physical activity behaviour. Successful results have indeed been shown in intervention studies where partners and family were involved in lifestyle programmes as well (Dorfman et al., Citation2022; George et al., Citation2020).

Second, physical side-effects from cancer or its treatment, such as extreme fatigue, loss of energy and (fear of) lymphoedema have consistently shown to be barriers for attending a weight management programme and need to be addressed. Our findings show that this is not only because of the symptom burden, but also because of possible negative outcome expectations with regard to the symptoms. It is therefore essential that healthcare professionals appoint these complaints and explain that a healthy lifestyle and exercise is not only safe, but also likely to reduce such side-effects (Juvet et al., Citation2017).

Timing and setting of a weight management intervention are essential to consider. In the studies included in this review, most patients would prefer to start during treatment or early in the trajectory. This is supported by intervention studies, which have shown promising results of the effect of exercise during, or right after treatment on side-effects and health related quality of life (Dieli-Conwright et al., Citation2018; Mishra et al., Citation2012). Patients generally preferred to be professionally monitored in a nearby facility. This suggests that although weight management programmes should be initiated in the hospital, they should preferably be offered—at least in part—in primary care or community settings.

For future weight management programmes, all of the above-mentioned factors should be included in a combined intervention, of which the feasibility and effectiveness have to be tested in a randomized controlled trial.

Strengths and limitations

Notable strengths of this systematic review include the extensive systematic search supported by an experienced clinical librarian and the systematic quality appraisal.

To gain a broad perspective on the subject, this review included studies describing possible outcome expectations of a weight management programme or interventions that could be part of weight management, as well as studies evaluating existing programmes. The distinction between these categories was sometimes ambiguous. However, this difficulty has been addressed by getting two different authors agree on the thematic analysis and by using an explicit framework to organize the findings. A limitation of this is study is that non-English studies were excluded and consequently, most of the included studies were from the US or Canada which could lead to overemphasis on culturally dependent findings. However, corresponding themes were found in studies from European countries, Australia and New Zealand, which makes it plausible that most outcomes are universal.

Examining healthcare professionals’ perspectives was beyond the scope of our study, but could also provide new insights on possible barriers and facilitators in weight management with breast cancer patients. This would be useful to investigate in future research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, breast cancer patient views and experiences about weight management programmes fit largely within the more generic behavioural framework of the ASE model. Within the concepts of the ASE model, several disease specific issues were identified including feeling stigmatized after cancer treatment and physical. Side effects like extreme fatigue and lymphoedema, and the motivating effect of social support from fellow survivors should be given specific attention.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank Erica Wilthagen, clinical librarian at the Antoni van Leeuwenhoek-The Netherlands Cancer institute for assisting in the literature search.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sheena Tjon A Joe

Sheena Tjon A Joe Clinical research that benefits the patient is the main focus in my work. Nutrition and lifestyle can make a great impact on the oncological patients journey and improve quality of life in all stages of disease. My goal is to implement nutrition and lifestyle in standard care and to provide patients with accurate information about these subjects.

Sara Verschure-Dorsman

Sara Verschure-Dorsman As a nutritionist and researcher, my main goal is to perform patient-centred clinical research to improve clinical care in oncology. The aim of my research is to survey the most important barriers and facilitators for weight management, in order to provide woman with breast cancer with better support and better overall quality of life.

Erica A. Wilthagen

E.A. Wilthagen, works as a medical information specialist for the Scientific Information Service at the Netherlands Cancer Institute. She also chairs the professional association of biomedical information specialists (BMI), and is involved in various BMI committees.

Martijn Stuiver

Martijn Stuiver The main goals of my research are to understand how functional impairments caused by cancer(-treatment) impact peoples’ functioning in daily life, and consequently their quality of life; how these impairments can be measured; and how they can be prevented or mitigated by targeted and timely offered rehabilitation interventions, exercise in particular. In addition, I aim to support implementation of successful interventions into usual care, through research into the perspectives of patients and health care professionals, and via innovative care implementation projects.

References

- Anbari, A. B., Deroche, C. B., & Armer, J. M. (2019). Body mass index trends and quality of life from breast cancer diagnosis through seven years’ survivorship. World Journal of Clinical Oncology, 10(12), 382–22. https://doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v10.i12.382

- Balneaves, L. G., Truant, T. L. O., Van Patten, C., Kirkham, A. A., Waters, E., & Campbell, K. L. (2020). Patient and medical Oncologists’ perspectives on prescribed lifestyle intervention—experiences of women with breast cancer and providers. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(9), 9(9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092815

- Balneaves, L. G., Van Patten, C., Truant, T. L. O., Kelly, M. T., Neil, S. E., & Campbell, K. L. (2014). Breast cancer survivors’ perspectives on a weight loss and physical activity lifestyle intervention. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(8), 2057–2065. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2185-4

- Broderick, J. M., Hussey, J., Kennedy, M. J., & O’Donnell, D. M. (2014). Testing the ‘teachable moment’ premise: Does physical activity increase in the early survivorship phase? Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(4), 989–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2064-4

- Brunet, J., & St-Aubin, A. (2016). Fostering positive experiences of group-based exercise classes after breast cancer: What do women have to say? Disability & Rehabilitation, 38(15), 1500–1508. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1107633

- Brunet, J., Taran, S., Burke, S., & Sabiston, C. M. (2013). A qualitative exploration of barriers and motivators to physical activity participation in women treated for breast cancer. Disability & Rehabilitation, 35(24), 2038–2045. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.802378

- Bulmer, S. M., Howell, J., Ackerman, L., & Fedric, R. (2012). Women’s perceived benefits of exercise during and after breast cancer treatment. Women Health, 52(8), 771–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2012.725707

- Butler, A., Hall, H., & Copnell, B. (2016). A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in Nursing and health care. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing / Sigma Theta Tau International, Honor Society of Nursing, 13(3), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12134

- Congdon, P. (2019). Obesity and urban environments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030464

- de Kruif, A. J., Westerman, M. J., Winkels, R. M., Koster, M. S., van der Staaij, I. M., van den Berg, M. M. G. A., de Vries, J. H. M., de Boer, M. R., Kampman, E., & Visser, M. (2021). Exploring changes in dietary intake, physical activity and body weight during chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics: The Official Journal of the British Dietetic Association, 34(3), 550–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12843

- Demark-Wahnefried, W., Peterson, B. L., Winer, E. P., Marks, L., Aziz, N., Marcom, P. K., Blackwell, K., & Rimer, B. K. (2001). Changes in weight, body composition, and factors influencing energy balance among premenopausal breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 19(9), 2381–2389. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2381

- de Vries, H., Backbier, E., & Kok, G. (1995). The impact of social influences in the context of attitude, self-efficacy, intention and previous behaviour as predictors of smoking onset. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(3), 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb01593.x

- Dieli-Conwright, C. M., Courneya, K. S., Demark-Wahnefried, W., Sami, N., Lee, K., Sweeney, F. C., Stewart, C., Buchanan, T. A., Spicer, D., Tripathy, D., Bernstein, L., & Mortimer, J. E. (2018). Aerobic and resistance exercise improves physical fitness, bone health, and quality of life in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Research: BCR, 20(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-018-1051-6

- Dixon, J. K., Moritz, D. A., & Baker, F.L. (1978). Breast cancer and weight gain: An unexpected finding. Oncology Nursing Forum, 5(3), 5–7.

- Dorfman, C. S., Somers, T. J., Shelby, R. A., Winger, J. G., Patel, M. L., Kimmick, G., Craighead, L., & Keefe, F. J. (2022). Development, feasibility, and acceptability of a behavioral weight and symptom management intervention for breast cancer survivors and intimate partners. Journal of Cancer Rehabilitation, 5, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.48252/JCR57

- Ee, C., Cave, A. E., Naidoo, D., Bilinski, K., & Boyages, J. (2020). Weight management barriers and facilitators after breast cancer in Australian women: A national survey. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01002-9

- Evans, D. (2002). Database searches for qualitative research. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 90(3), 290–293.

- Faber-Langendoen, K. (1996). Weight gain in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 276(11), 855–856. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1996.03540110009004

- Fazzino, T. L., Sporn, N. J., & Befort, C. A. (2016). A qualitative evaluation of a group phone-based weight loss intervention for rural breast cancer survivors: Themes and mechanisms of success. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(7), 3165–3173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3149-7

- George, S. M., Noriega Esquives, B., Agosto, Y., Kobayashi, M., Leite, R., Vanegas, D., Perez, A. T., Calfa, C., Schlumbrecht, M., Slingerland, J., & Penedo, F. J. (2020). Development of a multigenerational digital lifestyle intervention for women cancer survivors and their families. Psycho-Oncology, 29(1), 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5236

- Goodman, S. (2008). The generalizability of discursive research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 5(4), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880802465890

- Goodwin, P. J., Panzarella, T., & Boyd, N. F. (1988). Weight gain in women with localized breast cancer — a descriptive study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 11(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01807559

- Hefferon, K., Murphy, H., McLeod, J., Mutrie, N., & Campbell, A. (2013). Understanding barriers to exercise implementation 5-year post-breast cancer diagnosis: A large-scale qualitative study. Health Education Research, 28(5), 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyt083

- Hirschey, R., Docherty, S. L., Pan, W., & Lipkus, I. (2017). Exploration of exercise outcome expectations among breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 40(2), E39–e46. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000362

- Howard-Anderson, J., Ganz, P. A., Bower, J. E., & Stanton, A. L. (2012). Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 104(5), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djr541

- Husebø, A. M., Karlsen, B., Allan, H., Søreide, J. A., & Bru, E. (2015). Factors perceived to influence exercise adherence in women with breast cancer participating in an exercise programme during adjuvant chemotherapy: A focus group study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(3–4), 500–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12633

- Ingram, C., Wessel, J., & Courneya, K. S. (2010). Women’s perceptions of home-based exercise performed during adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing: The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 14(3), 238–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2010.01.027

- Irwin, M. L., Crumley, D., McTiernan, A., Bernstein, L., Baumgartner, R., Gilliland, F. D., Kriska, A., & Ballard-Barbash, R. (2003). Physical activity levels before and after a diagnosis of breast carcinoma: The health, eating, activity, and lifestyle (HEAL) study. Cancer, 97(7), 1746–1757. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11227

- Jones, L. M., Reinhoudt, L. L., Hilverda, F., Rutjes, C., & Hayes, S. C. (2020). Using the integrative model of behavioral prediction to understand female breast cancer survivors’ barriers and facilitators for adherence to a community-based group-exercise programme. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 36(5), 151071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151071

- Juvet, L. K., Thune, I., Elvsaas, I. K. Ø., Fors, E. A., Lundgren, S., Bertheussen, G., Leivseth, G., & Oldervoll, L. M. (2017). The effect of exercise on fatigue and physical functioning in breast cancer patients during and after treatment and at 6 months follow-up: A meta-analysis. The Breast, 33, 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.04.003

- Kim, S., Han, J., Lee, M. Y., & Jang, M. K. (2020). The experience of cancer-related fatigue, exercise and exercise adherence among women breast cancer survivors: Insights from focus group interviews. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(5–6), 758–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15114

- Kokts-Porietis, R. L., Stone, C. R., Friedenreich, C. M., Froese, A., McDonough, M., & McNeil, J. (2019). Breast cancer survivors’ perspectives on a home-based physical activity intervention utilizing wearable technology. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(8), 2885–2892. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4581-7

- Leddy, S. K. (1997). Incentives and barriers to exercise in women with a history of breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 24(5), 885–890.

- Lloyd, G. R., Hoffman, S. A., Welch, W. A., Blanch-Hartigan, D., Gavin, K. L., Cottrell, A., Cadmus-Bertram, L., Spring, B., Penedo, F., Courneya, K. S., & Phillips, S. M. (2020). Breast cancer survivors’ preferences for social support features in technology-supported physical activity interventions: Findings from a mixed methods evaluation. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(2), 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/iby112

- Loh, S. Y., Chew, S. L., & Lee, S. Y. (2011). Physical activity and women with breast cancer: Insights from expert patients. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP, 12(1), 87–94.

- Mackenzie, C. R. (2015). Breast cancer survivors’ experiences of partner support and physical activity participation. Psycho-Oncology, 24(9), 1197–1203. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3808

- Makari-Judson, G., Braun, B., Joseph Jerry, D., & Mertens, W.C.(2014). Weight gain following breast cancer diagnosis: Implication and proposed mechanisms. World Journal of Clinical Oncology, 5(3), 272–282. https://doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.272

- McInnes, J. A., & Knobf, M. T. (2001). Weight gain and quality of life in women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 28(4), 675–684.

- Milosevic, E., Brunet, J., & Campbell, K. L. (2020). Exploring tensions within young breast cancer survivors’ physical activity, nutrition and weight management beliefs and practices. Disability & Rehabilitation, 42(5), 685–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1506512

- Mishra, S. I., Scherer, R. W., Snyder, C., Geigle, P. M., Berlanstein, D. R., & Topaloglu, O. (2012). Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012(8), CD008465. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008465.pub2

- Monteiro-Guerra, F., Signorelli, G. R., Rivera-Romero, O., Dorronzoro-Zubiete, E., & Caulfield, B. (2020). Breast cancer survivors’ perspectives on motivational and personalization strategies in mobile app–based physical activity coaching interventions: Qualitative study. JMIR mHealth Uhealth, 8(9), e18867. https://doi.org/10.2196/18867

- Nielsen, A. M., Welch, W. A., Gavin, K. L., Cottrell, A. M., Solk, P., Torre, E. A., Blanch-Hartigan, D., & Phillips, S. M. (2020). Preferences for mHealth physical activity interventions during chemotherapy for breast cancer: A qualitative evaluation. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(4), 1919–1928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05002-w

- Nock, N. L., Owusu C, Flocke S, Krejci SA, Kullman EL, Austin K, Bennett B, Cerne S, Harmon C, Moore H, Vargo M. A (2015). A community-based exercise and support group programme improves quality of life in African-American breast cancer survivors: A quantitative and qualitative analysis. International Journal of Sports and Exercise Medicine, 1(4), 1(3. https://doi.org/10.23937/2469-5718/1510020

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Review, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Owusu, C., Antognoli, E., Nock, N., Hergenroeder, P., Austin, K., Bennet, E., Berger, N. A., Cerne, S., Foraker, K., Heine, K., Heyman, E., Moore, H., Petkac, J., Schluchter, M., Schmitz, K. H., Whitson, A., & Flocke, S. (2018). Perspective of older African-American and non-Hispanic white breast cancer survivors from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds towards physical activity: A qualitative study. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 9(3), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.12.003

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, Shamseer, L, Tetzlaff, JM, Akl, EA, Brennan, SE, Chou, R. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71).

- Piacentine, L. B., Robinson, K. M., Waltke, L. J., Tjoe, J. A., & Ng, A. V. (2018). Promoting Team-based exercise among African American breast cancer survivors. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 40(12), 1885–1902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945918795313

- Pila, E., Sabiston, C. M., Taylor, V. H., & Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. (2018). “The weight is even Worse than the cancer”: Exploring weight preoccupation in women treated for breast cancer. Qualitative Health Research, 28(8), 1354–1365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318770403

- Playdon, M., Thomas, G., Sanft, T., Harrigan, M., Ligibel, J., & Irwin, M. (2013). Weight loss intervention for breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Current Breast Cancer Reports, 5(3), 222–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-013-0113-0

- Power, J. M., Tate, D. F., & Valle, C. G. (2020). Experiences of African American breast cancer survivors using digital scales and activity trackers in a weight gain prevention intervention: Qualitative study. JMIR mHealth Uhealth, 8(6), e16059. https://doi.org/10.2196/16059

- Pullen, T., Bottorff, J. L., Sabiston, C. M., Campbell, K. L., Eves, N. D., Ellard, S. L., Gotay, C., Fitzpatrick, K., Sharp, P., & Caperchione, C. M. (2019). Utilizing RE-AIM to examine the translational potential of project MOVE, a novel intervention for increasing physical activity levels in breast cancer survivors. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 9(4), 646–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/iby081

- Rogers, L. Q., Matevey, C., Hopkins-Price, P., Shah, P., Dunnington, G., & Courneya, K. S. (2004). Exploring social cognitive theory constructs for promoting exercise among breast cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 27(6), 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002820-200411000-00006

- Sander, A. P., Wilson, J., Izzo, N., Mountford, S. A., & Hayes, K. W. (2012). Factors that affect decisions about physical activity and exercise in survivors of breast cancer: A qualitative study. Physical Therapy, 92(4), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20110115

- Shaikh, H., Radhurst, P, Ma, LX, Tan, SY, Egger, SJ, Vardy, JL. (2020). Body weight management in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 12(12), Cd012110. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012110.pub2

- Shaw, S., Atkinson, K., & Jones, L. M. (2021). Cancer survivors’ experiences of an exercise programme during treatment and while employed: A qualitative pilot study. Health Promotion Journal of Australia: Official Journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals, 32 Suppl 2(S2), 378–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.447

- Short, C. E., James, E. L., & Plotnikoff, R. C. (2013). How social cognitive theory can help oncology-based health professionals promote physical activity among breast cancer survivors. European Journal of Oncology Nursing: The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 17(4), 482–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2012.10.009

- Smith, S. A., Claridy, M. D., Smith Whitehead, M., Sheats, J. Q., Yoo, W., Alema-Mensah, E. A., Ansa, B. E. O., & Coughlin, S. S. (2015). Lifestyle modification experiences of African American breast cancer survivors: A needs assessment. JMIR Cancer, 1(2), e9. https://doi.org/10.2196/cancer.4892

- Smith, S. A., Whitehead, M., Sheats, J., Chubb, B., Alema-Mensah, E., & Ansa, B. (2017). Community engagement to address socio-ecological barriers to physical activity among African American breast cancer survivors. Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association, 6(3), 393–397. https://doi.org/10.21633/jgpha.6.312

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Vance, V., Mourtzakis, M., McCargar, L., & Hanning, R. (2011). Weight gain in breast cancer survivors: Prevalence, pattern and health consequences. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 12(4), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00805.x

- van den Berg, M. M., Winkels, R. M., de Kruif, J. T. C. M., van Laarhoven, H. W. M., Visser, M., de Vries, J. H. M., de Vries, Y. C., & Kampman, E. (2017). Weight change during chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. BMC Cancer, 17(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3242-4

- Van Puymbroeck, M., Burk, B. N., Shinew, K. J., Kuhlenschmidt, M. C., & Schmid, A. A. (2013). Perceived health benefits from yoga among breast cancer survivors. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 27(5), 308–315. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.110316-QUAL-119

- Vassbakk-Brovold, K. J, Antonsen, A., Berntsen, S., Kersten, C., & Fegran, L. (2018). Experiences of patients with breast cancer of participating in a lifestyle intervention study while receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Nursing, 41(3), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000476

- Ventura, E. E., Ganz, P. A., Bower, J. E., Abascal, L., Petersen, L., Stanton, A. L., & Crespi, C. M. (2013). Barriers to physical activity and healthy eating in young breast cancer survivors: Modifiable risk factors and associations with body mass index. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 142(2), 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2749-x

- Whitehead, S., & Lavelle, K. (2009). Older breast cancer survivors’ views and preferences for physical activity. Qualitative Health Research, 19(7), 894–906. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309337523

- Wu, H. S., Gal, R., van Sleeuwen, N. C., Brombacher, A. C., IJsselsteijn, W. A., May, A. M., & Monninkhof, E. M. (2019). Breast cancer survivors’ experiences with an activity tracker integrated into a supervised exercise programme: Qualitative study. JMIR mHealth Uhealth, 7(2), e10820. https://doi.org/10.2196/10820

- Wurz, A., St-Aubin, A., & Brunet, J. (2015). Breast cancer survivors’ barriers and motives for participating in a group-based physical activity programme offered in the community. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 23(8), 2407–2416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2596-2

- Yufe, S. J., Fergus, K. D., & Male, D. A. (2019). Lifestyle change experiences among breast cancer survivors participating in a pilot intervention: A narrative thematic analysis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing: The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 41, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.06.001

- Yufe, S. J., Fergus, K. D., & Male, D. A. (2021). Storying my lifestyle change: How breast cancer survivors experience and reflect on their participation in a pilot healthy lifestyle intervention. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 16(1), 1864903. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2020.1864903

- Zeng, X., Zhang, Y., Kwong, J. S. W., Zhang, C., Li, S., Sun, F., Niu, Y., & Du, L. (2015). The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: A systematic review. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 8(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12141

Appendix 1:

Search strategy

Medline (ovid)

Embase.com

PsycINFO

Appendix 2:

ASE-Model, as defined by de Vries et al. [24]